CHAPTER 5

EXCAVATION AT CHINAMAN’S POINT

An understanding of the lifestyle, technology, artefact types and site layout at a colonial Chinese fish-curing establishment would not have been possible without archaeological excavation. Chapter 5 explains the excavation component of this project, including the rationale for site selection, a site description, the excavation methodology and an account of each excavated area and discussion of the results.

The excavation assisted to evaluate the contribution of Chinese groups to the establishment and continued development of Victoria’s commercial fishing industry. Information from the excavation forms the basis – in later chapters – for an examination and understanding of Chinese fish curers in colonial Victoria. A detailed discussion and interpretation of the artefacts recovered from the site is the focus of chapter 6.

SITE SELECTION

The abandoned site at Chinaman’s Point, Port Albert, was identified through local oral histories, historical documentation and surface artefact scatters. It was subsequently recorded with Heritage Victoria as Heritage Inventory No. H8220-0011. The site contains the only conclusive evidence of Chinese fish-curing activity found during extensive field research in Victoria. There is currently no known material evidence of Chinese fish-curing activities elsewhere in Australia. Further investigation – i.e. excavation – was conducted to gain an understanding – through artefacts and ground features – of the working and living conditions for Chinese fish curers in colonial Australia.

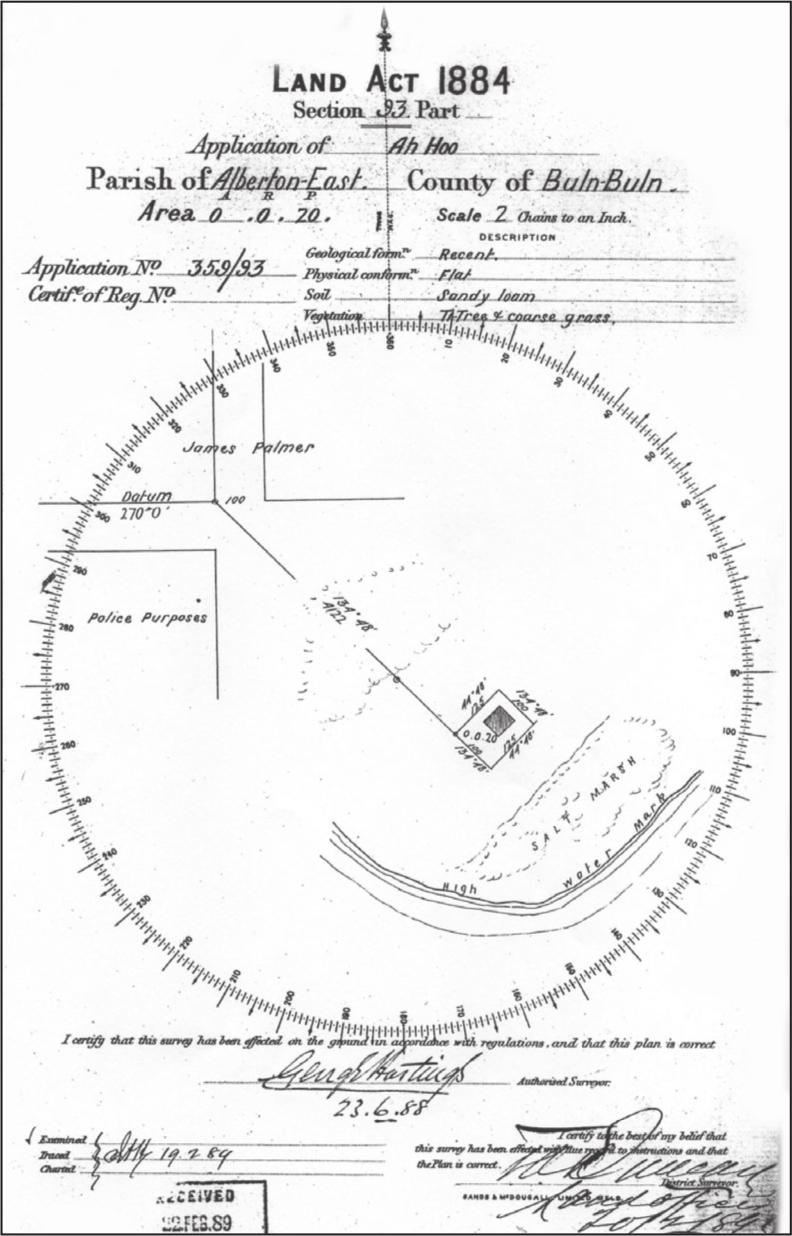

Figure 5.1 Survey map included in Ah Hoo’s 1888 land title documents for Chinaman’s Point (PROV, VPRS 5357/P0000, unit 5899).

A land titles document from 1888 indicates that Ah Hoo leased a one-acre site at Chinaman’s Point as a fisherman’s residence (PROV, VPRS 5357/P0000, unit 5899). The document includes a survey map with a compass bearing and datum marker indicating the position of the dwelling (figure 5.1). While the original ground datum – a timber post located 830 m north west of the site – was identified, tall eucalyptus trees and 73dense scrubby tea-trees hampered attempts to get an exact electronic measurement along the compass bearing from datum to house site. A measurement was taken by compass and tape measure, but due to the dense vegetation, salt marsh and mangroves, it was not possible to obtain an accurate location for the dwelling. There was also an absence of any visible house remains at the site. Nevertheless, the land title document provides a useful guide to the general location of the residential area, the former shoreline position and the physical ground environment during the occupation period – each of which assisted in the planning of fieldwork at the site.

Site description

South Gippsland’s geology is comprised of a bedding of Mesozoic tectonic belt – mainly consisting of cretaceous sediments – which extends across southern Victoria and out onto the continental shelf (Singleton 1973: 129, 133). In the late Pleistocene period (500 000 – 100 000 years ago), a siliciclastic barrier system (sand dunes) was deposited along the Gippsland coast and formed a series of estuarine lakes.

Fluvial sediments became trapped by the lakes to form coastal swamp deposits. During the late Quaternary period (approximately 50 000 years ago) more sand was deposited along this coast line, creating a layer of swamp between two sandy layers under the present day south-Gippsland lakes and beaches (Birch 2003: 355–56).

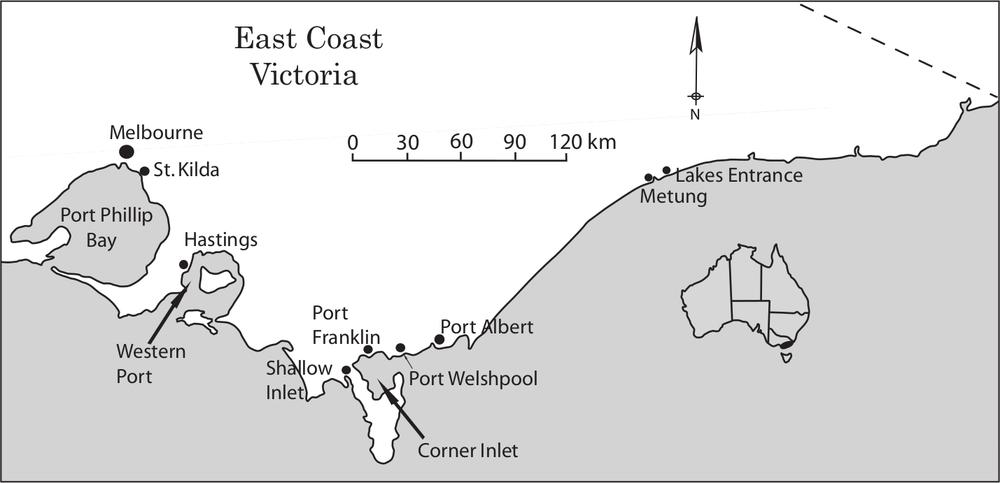

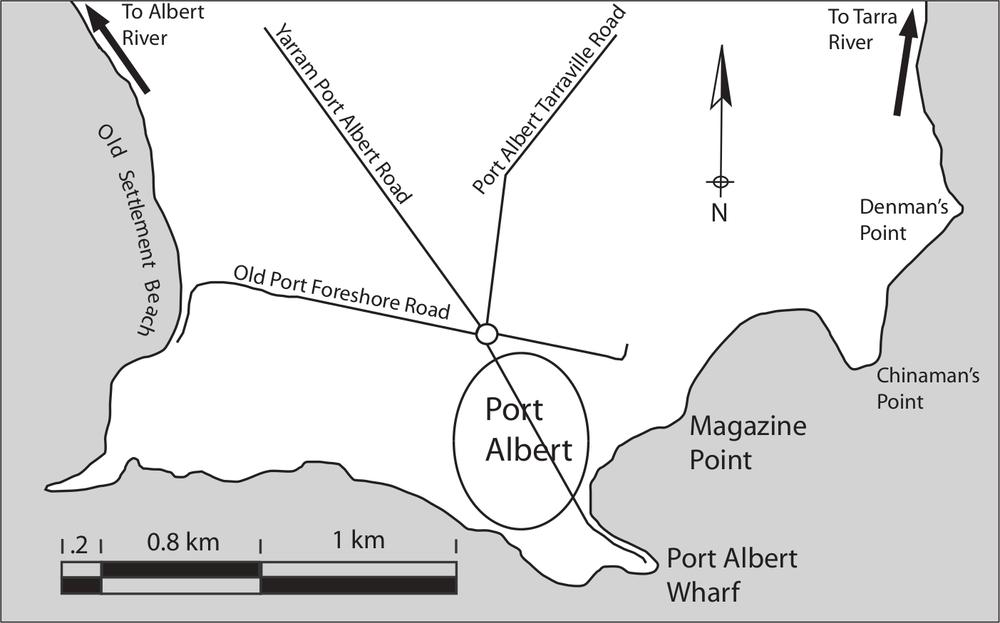

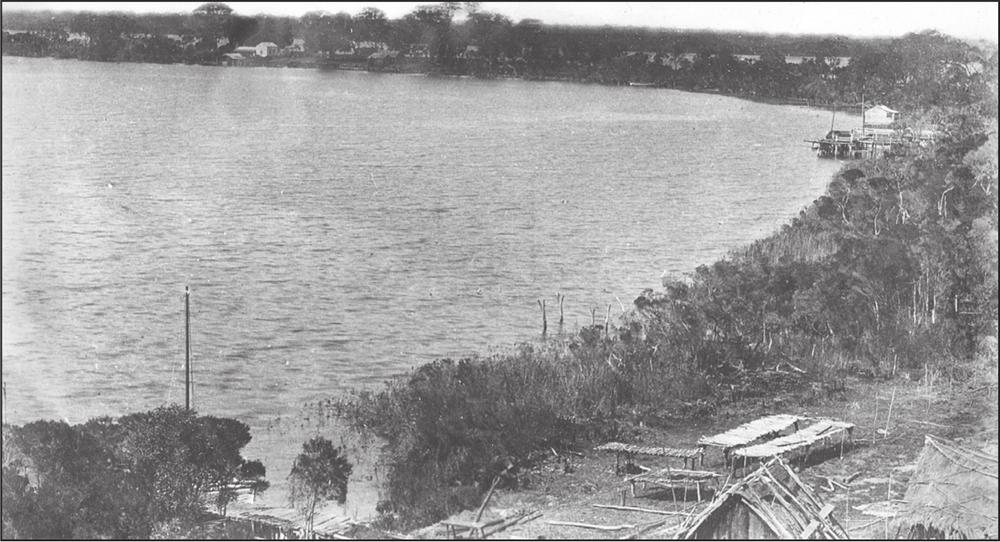

Chinaman’s Point near Port Albert in south Gippsland (figure 5.2) was previously known as Long Point. Some time during the mid 20th century, well after the Chinese had abandoned the site, its name changed to reflect the former Chinese presence. The site is located at the end of Chinaman’s Point, 1.6 km north-east of Port Albert, in the shire of Wellington, parish of Alberton East, county of Buln Buln and within the boundaries of Nooramunga Marine and Coastal Park – AMG co-ordinates: VICMAP Port Albert 8220-4-2, Zone 55, grid reference: 47465 571991 (figure 5.3).

Figure 5.2 Map of the east coast of Victoria showing the location of Port Albert. Chinaman’s Point is 1.6 km north-east of Port Albert.74

Figure 5.3 Map of the Port Albert region showing the location of Chinaman’s Point.

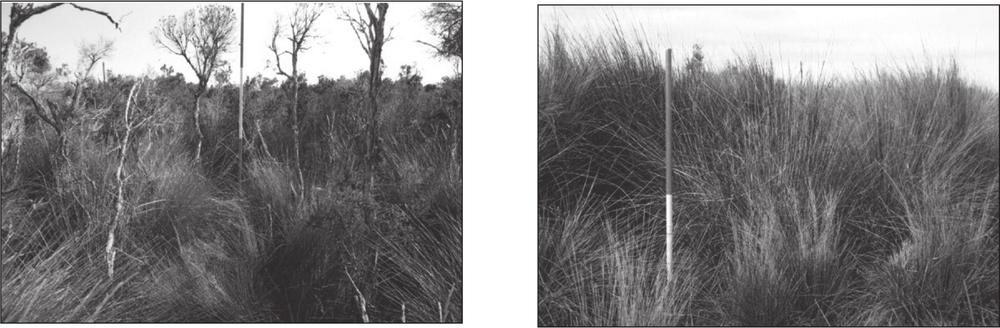

The land narrowing to Chinaman’s Point is made of alluvial sediments washed down from the Eastern Highlands to form an extensive flood plain, with sections of tidal swampy salt marsh, directly inland from the coastal sand-dune and lake systems. The soils consist of fine sands, silts and clays, covered with dense pockets of scrubby swamp paper bark (tea-tree) (Melaleuca ericifolia), swampy mangrove shrub and low-level coastal blue tussock grass (Poa poiformis) (Birch 2003: 557; Walsh and Entwisle 1994: 433). The final 70 m of Chinaman’s Point – the site area – has a slightly higher elevation and therefore is not swampland or tidally inundated. This elevated ground has a thick cover of tussock grass with some pockets of tea-tree (figure 5.4). In this heavily vegetated state, ground visibility at the site is zero.

Figure 5.4 Vegetation cover on the Chainman’s Point site area.

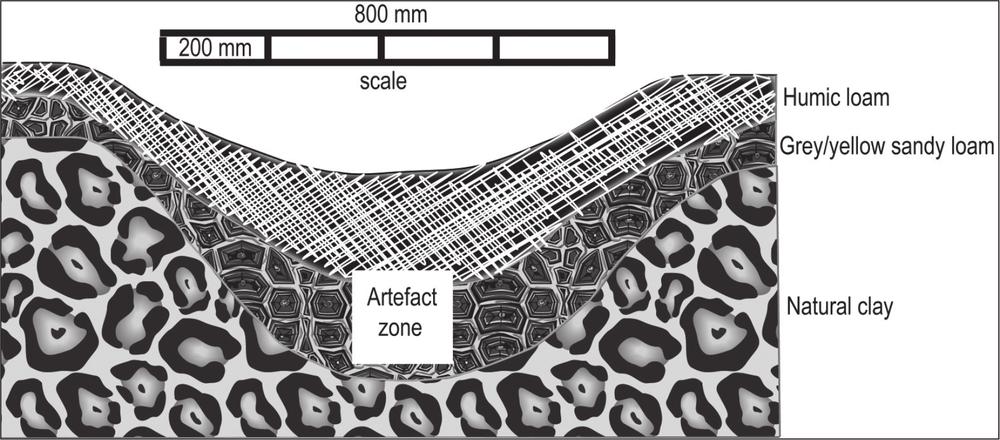

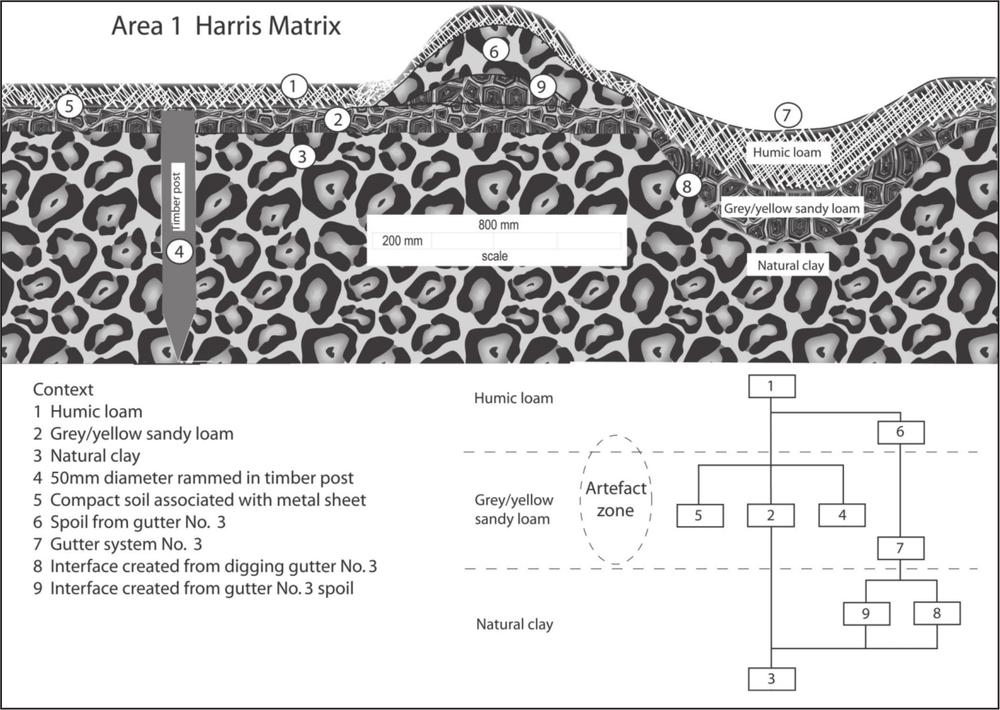

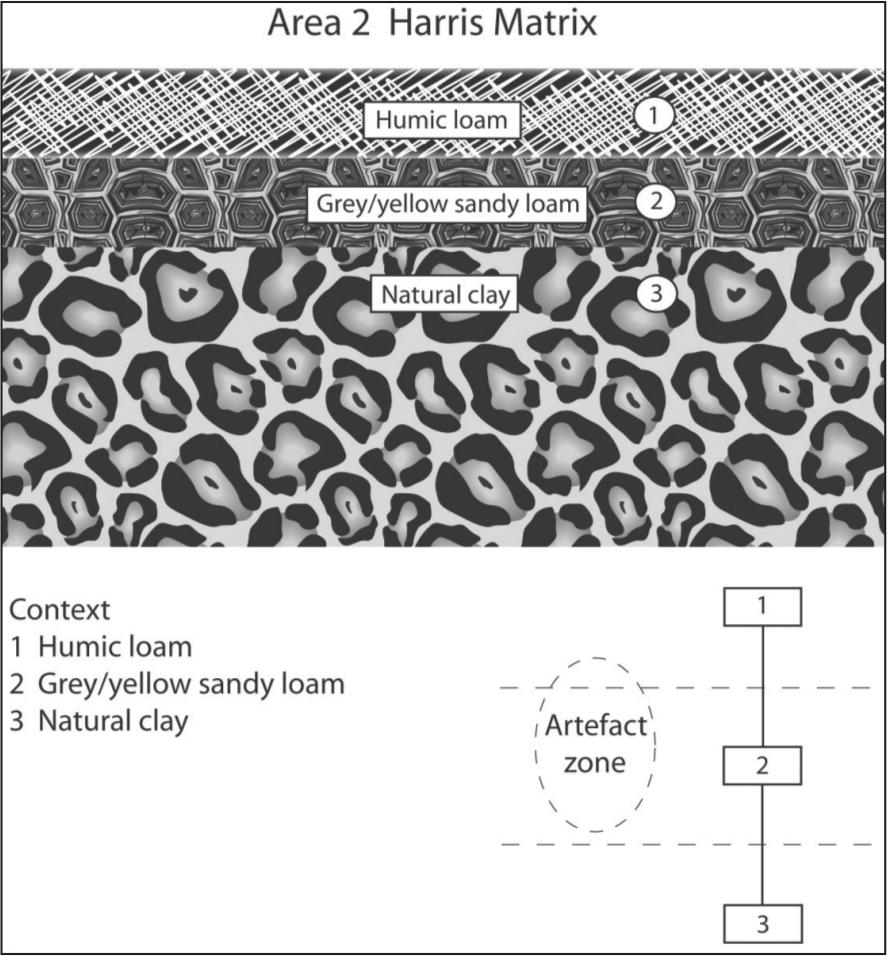

Test pits dug across the site showed the soil strata to be a fairly uniform three-unit stratigraphy. Surface layers consisted of approximately 40 to 80 mm – unit one – of brown (Munsell 10yr 3/2) humic loam. Below this was approximately 40 to 80 mm – unit two – of grey/yellow (Munsell 10yr, 7/8) sandy loam, with some clay content and leaching from the upper layer. This middle layer merged into tan-coloured (Munsell 10yr 6/1) clay – unit three – mottled with sandy dots, which continued to the bottom of the deepest test pit – 800 mm below surface level. Ground pH levels remain relatively neutral at 6 to 7.5, which, combined with moist soil conditions enabled good preservation of organic materials such as bone, leather and wood.

Where high tide meets the bank, the site is exposed to continuous wave action, resulting in a drop of approximately one metre between dry land and the sandy tidal zone that becomes exposed at low tide. Chinaman’s Point is therefore a rapidly eroding headland only millimetres above high tide mark (figure 5.5). If sea levels rise just 50 cm over the next 100 years, wave wash and tidal movements will destroy archaeological evidence of past inshore coastal fishing activities world wide. 75

Figure 5.5 The rapidly eroding condition of Chinaman’s Point (looking north).

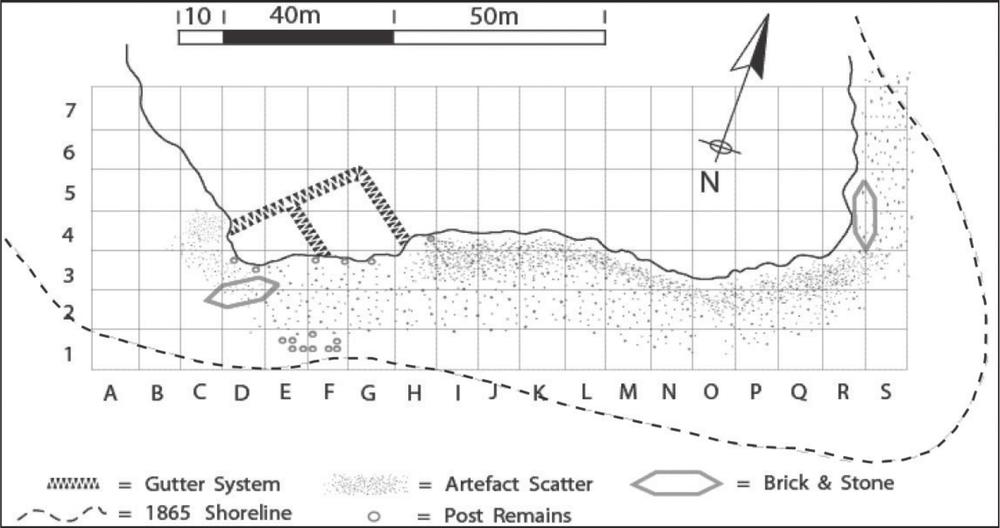

By comparing aerial photographs taken in 1941 to ones taken in 2002 and using the lands title document from 1888, it is estimated that from 1865 to the present, some 100 m of Chinamen’s Point has been washed away through erosion (figure 5.6). With this, literally thousands of artefacts have become dislodged from their in-situ positions and strewn across the site frontage by tidal movements. These artefacts include brick, imported stone, bone and hundreds of broken ceramic, glass and metal artefacts. Many of these confirm an association with Chinese people, including medicine vials, broken sections of opium smoking equipment, blue-green (celadon) ceramics, brown-green glaze Chinese earthenware and Chinese teapot ceramics. Ground holes – accompanied by broken artefacts – are prolific on the site surface, providing evidence of bottle-collector and artefact-scavenging activities. Artefact scavengers and their collections represent a potential resource that, to some degree, has been exploited for this project.

Figure 5.6 Plan of the Chinaman’s Point site, including ten-by-ten metre grid system, site features and the estimated 1865 shoreline.

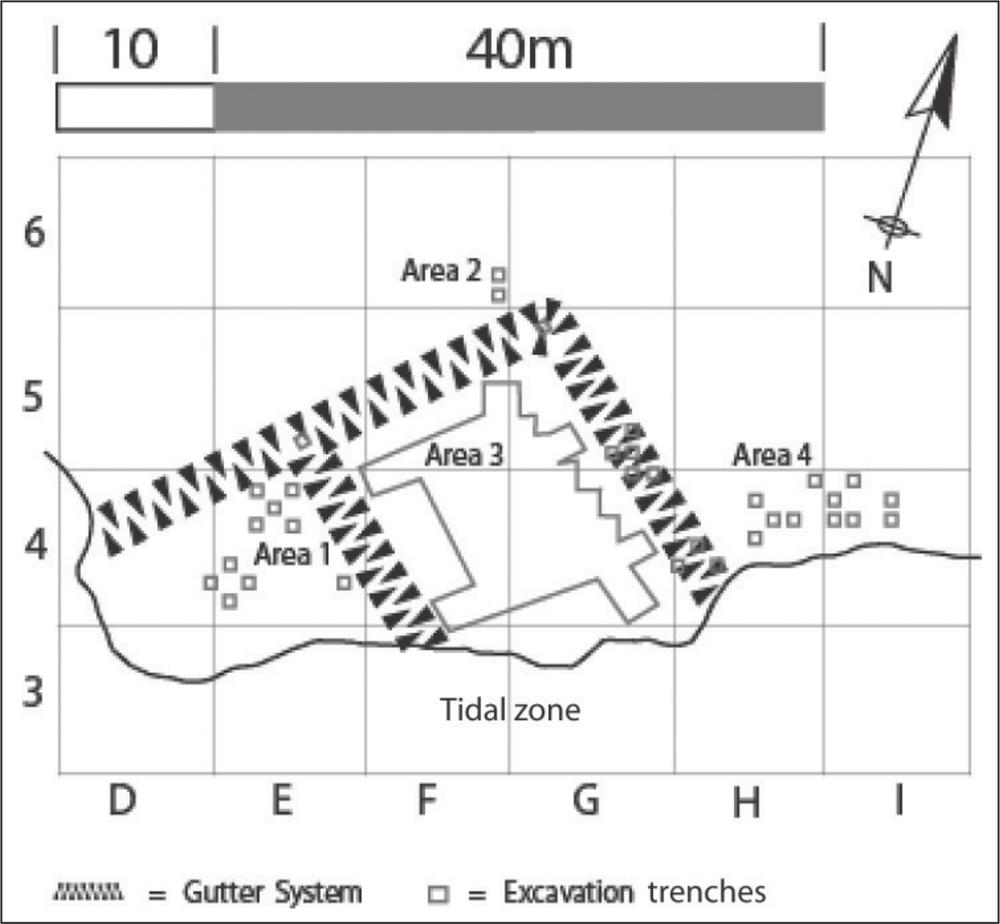

Three purposely dug, inter-joining gutters approximately 800 mm wide by 600 mm deep, encompassing 68 lineal metres of gutter and forming two segregated areas were identified, recorded and in part excavated (figure 5.7). These trenches – discussed later in this chapter – most likely represent a drainage system designed to keep the surrounding swamp away from the working and domestic areas of the site. 76

Figure 5.7 Map detailing the gutter system, excavated trenches in the gutter system and site excavation areas 1, 2, 3 and 4.

As domestic and industrial-type artefacts appear in the same localised area, it is believed the site represents both domestic and working spaces.

METHODOLOGY

Archaeological excavation of the site began on 2 February 2004 and was completed on 28 February 2004. The excavation team consisted of volunteer students from the Archaeology Program at La Trobe University. The strategy was to identify areas of potential interest, clear surface vegetation, conduct surface collections, map the site and excavate – in order to recover artefacts and identify site features, then backfill all excavated soils and replant vegetation.

The site was occupied for an estimated period of 40 years, from the 1860s to early 1900, as discussed in chapter 7. This relatively short period suggests the stratification of cultural layers would be shallow. Lindsay Smith (1998: 65, 170) established that the average depth of cultural deposits at 6 separate excavations at historical Chinese mining sites in New South Wales was 150 mm. Peter Davies (Davies 2001a: 50) also found an average depth of 150 mm for historical material uncovered during excavations at the Henry’s Mill site in Victoria. Similarly, Zvonka Stanin found cultural deposits petered out at a depth of 150 mm during her excavations of a Chinese site at Mt Alexandria, Victoria (Stanin 2004b: 34). My personal experience suggests that historical cultural material in Australia is generally not found lower than 200 mm – very occasionally at 300 mm – from the surface layer. Accordingly, it was anticipated that the cultural material would most likely be located within the top 150 mm of soil at Chinaman’s Point. Given this, the technique of horizontal trowel excavation by squares on a grid layout was considered the most appropriate form of sub-surface investigation.

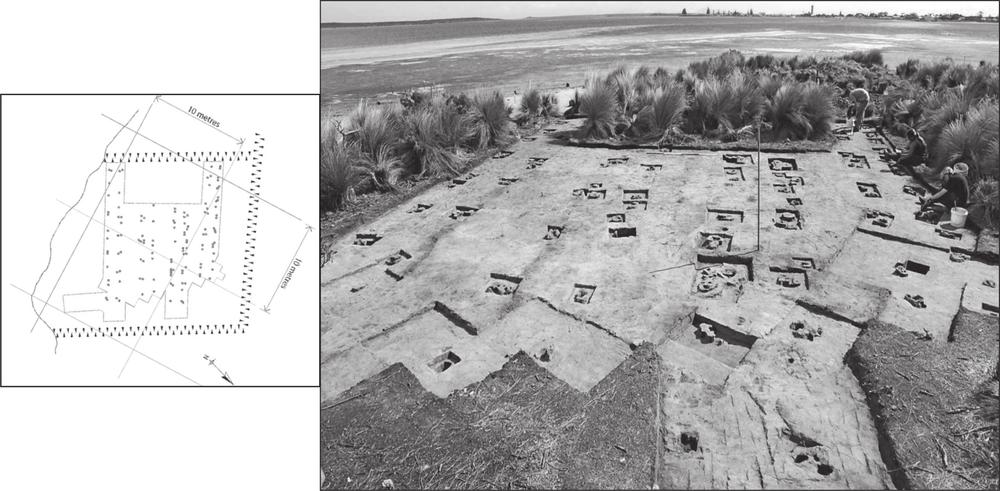

The site is 170 m long by 70 m wide. After carefully mapping the surface area using an electronic total station, string line and timber pegs, a ten-by-ten metre grid was set out over the entire site, including the artefact-littered tidal zone. The grid was labelled with an X and a Y axis: X representing one to seven and Y representing A to S (figure 5.6). In order to establish a reference datum, two stainless steel plates were engraved with ‘CMP 2004’ and set in concrete foundations on the exact intersections 5E and 5G of the site grid. This will allow any future archaeological investigators to lock exactly into the original grid system.

Test pits 200 by 200 mm were dug using a spade on dry land areas only at each intersection of the ten-by-ten metre site grid and the excavated soil was sieved for cultural material through 3 mm mesh. From this process, six areas of archaeological interest were identified: excavation areas 1, 2, 3 and 4, the gutter system and the site’s tidal zone (figure 5.7).

Ground cover on the areas to be excavated was cut low with a brush-cutter, removed carefully by mattock and deposited at the site margin. As excavated areas were to be re-vegetated (an excavation permit condition 77from Parks Victoria), plants were stored with as little soil as possible attached to the root system, under hessian sheets and watered daily. A number of one-by-one metre excavation squares were set out and excavations by steel trowel continued downwards in 50 mm spits until culturally sterile layers were reached. All excavated material was dry-sieved through 5 mm sieve squares and deposited on a tarpaulin at the site margin. A portion of the excavated soil from each excavation trench was sieved through a 3 mm sieve. This confirmed that no smaller artefacts were present and that an adequate representation of cultural material was recovered through the larger 5 mm sieves.

Surface artefacts deposited on the tidal areas of the site had undergone considerable post-depositional movement through tidal action. With each new tide the sands shift, moving artefacts around, covering some with sand and uncovering others. The artefacts on the tidal perimeter of the site were scattered across a linear distance of approximately 200 m (figure 5.6). In these areas (i.e. the site’s tidal zone) a surface collection was conducted on a daily basis and all visible artefacts were collected and bulk-bagged according to their ten-by-ten metre location.

In area 3, some bulk excavation was conducted by removing several two metre long and 50 mm deep strips using mattocks and shovels and sieving 25% of the excavated material. From the four excavation areas and the gutter system, 180 m2 of ground area was excavated to varying depths of between 50 and 200 mm – one to four spits – totalling approximately 27 m3 of excavated soil.

Recording of the excavation was conducted horizontally within the grid system and stratigraphically by spit and individual ground layer (natural stratigraphy). Each archaeological feature was allocated a context succession number that ran chronologically during the excavation period. Excavated trenches and features were photographed, drawn to scale and then mapped using a total station.

On completion of the project, all excavated soil was spread back over the areas by shovel, bucket and rake. Vegetation was then replanted and the slashed plant material laid down as ground mulch. Excavated artefacts were bulk-bagged according to their fabric and recorded by grid square and stratigraphic layer.

EXCAVATION

Most cultural material was located within the first two soil units – one to three spits. This was also the case for materials located in the base of the gutter system, which besides already having a depth of between 600 mm to 800 mm from the ground surface level, still held artefacts within the first two soil units naturally deposited through aeolian forces (figure 5.8).

Figure 5.8 Cross-section of gutter system showing soil matrix and artefact zone.

Gutter system

The 1888 land titles document indicated the area immediately south of the site had been a salt marsh (PROV, VPRS 5357/P0000, unit 5899) (figure 5.1). Cross-sections dug by the excavation team through the gutter system revealed the original gutter base had fallen away from the swamp. This suggests the system was designed to continuously drain the swamp area (as was and still is the custom in many regions of China) (Knapp 1989: 7820, 68; Mote 1977: 197), effectively controlling this environment and preventing water from reaching the dry working areas of the site.

Ten one-by-one metre excavation squares were dug in the gutter system (figure 5.7), revealing a range of domestic artefacts including 256 bottle glass shards, 62 shards of Chinese ceramics, a glass button, three metal nails, two chicken bones, two fish bones, four cow bones and two sheep bones (table 5.1).

| Gutter system | Number of artefact fragments | Weight (grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Bottle glass | 256 | 2441 |

| Window glass | 0 | 0 |

| Ceramic | 62 | 214 |

| Bone | 10 | 79 |

| Brick | 8 | 185 |

| Leather | 3 | 17 |

| Nails | 3 | 8 |

| Spikes | 0 | 0 |

| Screws | 1 | 4 |

| Cask hoop | 85 | 361 |

| Nondescript metal | 217 | 368 |

| Total | 645 | 3677 |

Table 5.1 Main artefact categories by number and weight from gutter system.

Excavation area 1

Within 4E of area 1, on the western limits of the gutter system, the only rewards from 11 one-by-one metre excavated squares were six round timber post remains (approximately 50 mm in diameter), five glass shards, two pieces of animal bone and scatters of heavily corroded metal fragments (2747 pieces, weighing 5452 kg) (table 5.2). Squares were excavated to depths of between 50 and 200 mm. The timber posts – well preserved underground – were made of tea-tree and had been axed to a sharpened point. This indicates the posts had been hammered into the ground rather than placed in a purposely dug hole and backfilled. They would not have stood higher than approximately 1.5 m (given they were hammered in) and were probably stay posts for drying fishing nets or supporting other lightweight items. The type of wood used for the posts – tea-tree – indicates that the site occupants obtained building materials from the immediate environment. Tea-tree, which remains prolific in this region, is a hard-wood resistant to salt environments and for these reasons was commonly used by fishing people as a building material during Victoria’s colonial period (Gippsland Times 1879, May 21). The stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 1 can be seen in Figure 5.9.

| Area 1 | Number of artefact fragments | Weight (grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Bottle glass | 5 | 73 |

| Window glass | 0 | 0 |

| Ceramic | 0 | 0 |

| Bone | 2 | 1 |

| Nails | 0 | 0 |

| Spikes | 0 | 0 |

| Cask hoop | 644 | 3947 |

| Nondescript metal | 2747 | 5452 |

| Total | 3396 | 9473 |

Table 5.2 Main artefact categories by number and weight from excavation area 1.79

Figure 5.9 Schematic diagram showing stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 1 (not to scale).

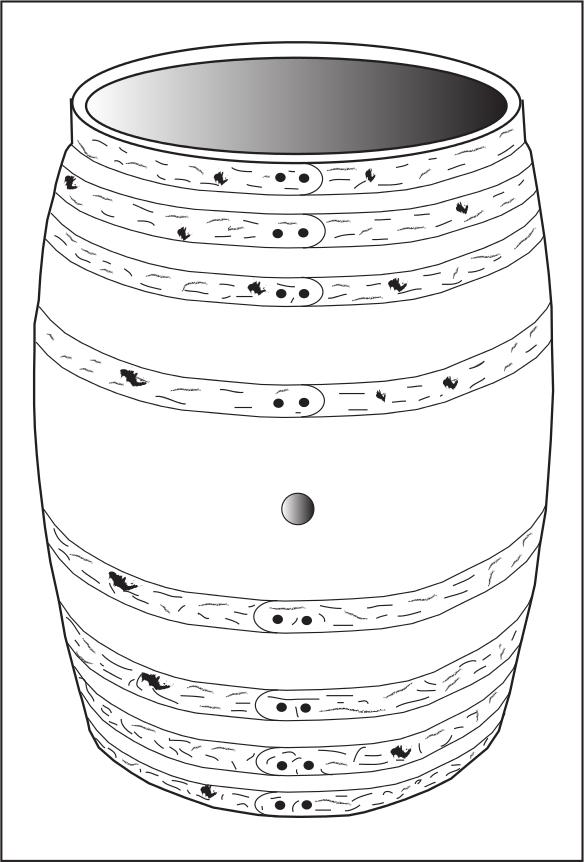

Many of the corroded metal fragments (644 pieces, weighing 3.947 kg) recovered from area 1 display a uniform width – 38 mm, 32 mm and 25 mm – and curvature. These match the 19th-century standard regulation widths for the top, middle and base hoops for wooden cask containers (Hughes 1926: 20). A cask is a generic term used to describe eight sizes of cylindrical wooden storage containers: the 745-litre leager, 500-litre butt, 372-litre puncheon, 245-litre hogshead, 164-litre barrel, 123-litre half, 82-litre kilderkin and the 41-litre firkin (Stevens 1894: 104). During the 19th century, casks were the most common container used to store and transport bulk items (figure 5.10). Casks with wooden hoops were constructed for holding dry or semi-liquid products and iron-hooped casks held liquids such as alcoholic beverages and vinegar (Staniforth 1987: 21). Timber casks likely represent a container for brining fish, as metal tubs would quickly rust and possibly taint fish flesh. Timber casks could be reused over long periods and may have been fitted with tight covers to reduce evaporation and dilution of the brine through rain water (Ashbrook 1955: 217). A number of metal rivets were found with the metal hoop-iron, consistent with the type of rivet used for storage casks. As limited domestic artefacts were recovered from area 1, this is thought to have been an industrial area, possibly for fish brining and drying nets.

Figure 5.10 A common 19th-century European iron-hooped 164-litre wooden barrel cask.80

Excavation area 2

Excavation of area 2, outside the north-eastern boundary of the gutter system, was uneventful. Exploratory test pitting revealed a small fragment of celadon porcelain and one shard of light blue bottle glass embedded in the top soil layer. Two one-by-one metre excavation squares, dug to a depth of 100 mm, revealed – just below surface level – four small celadon shards and one piece of nondescript corroded metal. The area was recorded and then abandoned. The stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 2 can be seen in Figure 5.11.

Figure 5.11 Stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 2 (not to scale).

Excavation area 3

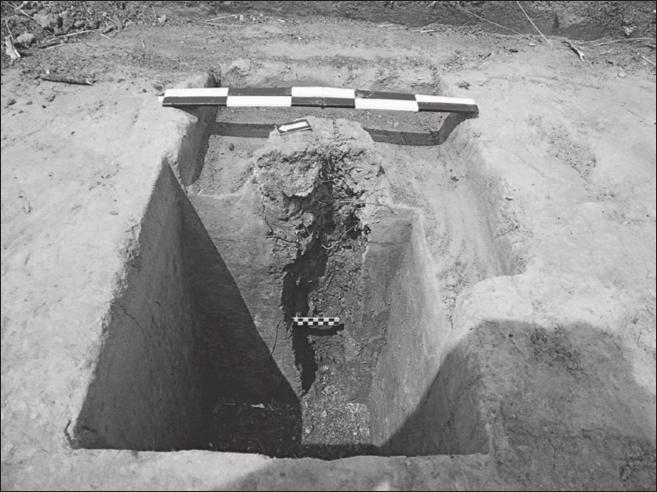

Excavations began in the eastern perimeter of the gutter system by opening a one-by-one metre exploratory square. Four consecutive squares revealed very little of interest, however in the fifth square the remains of a 80 mm round post were uncovered. Further excavated squares revealed more post remains until, by using both one-by-one metre squares and some bulk excavation, 146 m2 had been excavated, revealing the remains of 131 posts. Post circumferences ranged from 50 to 150 mm. In most cases, the posts appeared as vertical, circular tubes of dark humic matter encased in tan-coloured clay. Some posts had survived intact, providing evidence they were made of tea-tree and that the posts were cut by axe without a point, placed in a pre-dug hole and backfilled with clay from lower stratigraphic layers. Smaller 50 mm posts had been pointed by axe and rammed in beside larger posts, presumably to strengthen rotten or damaged supports. Cross-sections dug through the remains of three posts from different parts of area 3 reveal the posts were placed deep into the ground, the shallowest at 500 mm and the deepest at over one metre (figure 5.12).

Figure 5.12 Cross-section of excavated post remains. Note the rammed-hard backfilled clay at surface level and dark humic matter where post was positioned.

81It is evident that the posts were placed in four distinct rows, each approximately 1.5 m wide and 15 m long (figure 5.13). The solid timber foundations had been designed to support a great deal of weight, but are unlikely to represent house supports as no floor horizon was visible in the soil matrix, no hearth was evident and there was a very poor representation of domestic artefacts.

Figure 5.13 Plan diagram (left) and photograph (above) of excavated area 3. Looking west towards Port Albert, the layout of uncovered posts remains is clearly distinguishable.

An 1880s photograph of Shaving Point at Metung, Victoria, shows a very small portion of a Chinese fish-curing camp in which long, low-level fish-drying racks can be seen (figure 5.14). Several references cited in chapter 4 suggest Chinese fish curers used racks to dry their fish. For example, in 1861, a Sydney Morning Herald correspondent visited a Chinese fish-curing establishment at Sydney’s Palm Beach and reported the fish were dried in the open air on racks (Sydney Morning Herald 1861, April 6). Also, references to Chinese fish curers at Port Albert state that

A number of Chinese settled at Long Point [now Chinamen’s Point]. They bought fish at 7 pounds per ton, dried them on racks and sent them away by steamer. (Olson 1947: 118)

Figure 5.14 The previously shown NJ Caire photograph c. 1886 of Shaving Point, Metung, showing the low fish-drying racks visible in the right portion of the picture. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

The layout of the uncovered post remains, written accounts and the Metung photograph leave little doubt that area 3 represents the remains of a very sturdy fish-drying rack, built to take several tons of weight.

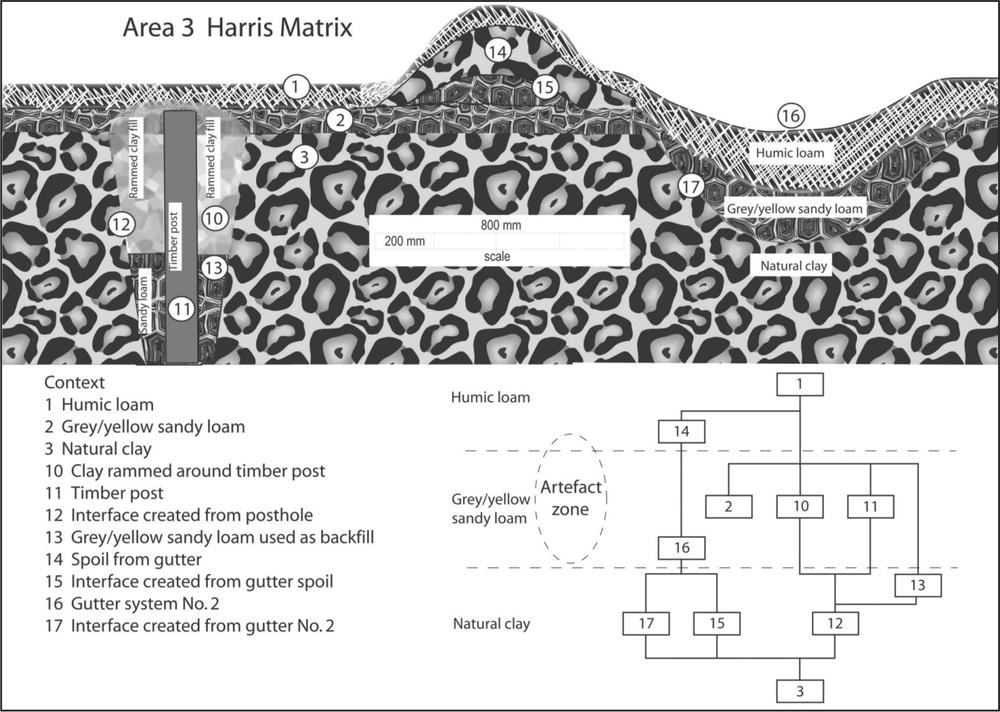

Other artefacts recovered from area 3 were 116 shards of glass, ten Chinese ceramic shards, five animal bone pieces, 1686 nondescript metal pieces (weighing 3.41 kg), nine metal nails and 144 pieces of metal cask hooping (table 5.3). The stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 3 can be seen in Figure 5.15. 82

| Area 3 | Number of artefact fragments | Weight (grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Bottle glass | 116 | 1388 |

| Window glass | 0 | 0 |

| Ceramic | 10 | 194 |

| Bone | 5 | 54 |

| Nails | 9 | 24 |

| Spikes | 0 | 0 |

| Cask hoop | 144 | 946 |

| Nondescript metal | 1686 | 3410 |

| Total | 1970 | 6016 |

Table 5.3 Main artefact categories by number and weight from excavation area 3.

Figure 5.15 Schematic diagram showing stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 3 (not to scale).

Excavation area 4

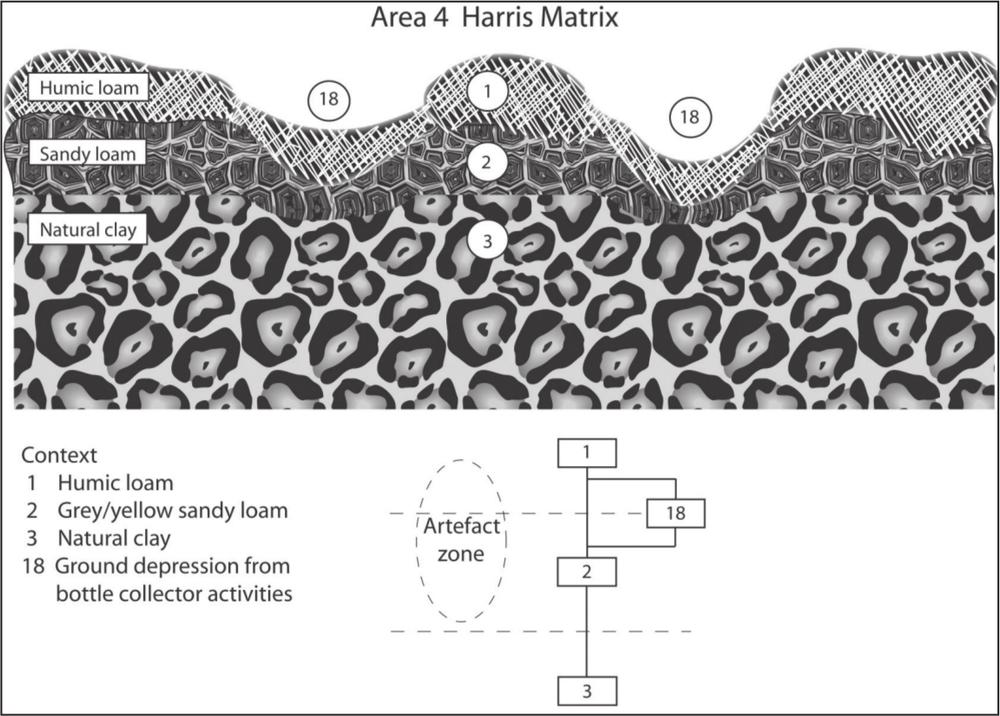

This section includes discussion of excavated artefacts and artefacts collected from the site’s tidal zone. Surface artefacts were densely scattered across the tidal zone immediately in front of excavation area 4 and many more artefacts were visible from the eroding shoreline in this area. A series of one-by-one metre excavation squares were opened 2 m in from the shoreline. Sub-surface layers in this area were particularly disturbed through bottle-collector and artefact-scavenging activities. Artefact types recovered from 11 excavation squares include 216 glass bottle shards, 23 glass window shards, 67 Chinese ceramic shards, nine bone pieces (sheep bone and teeth, butchered cow bone, chicken bone and fish bone), 762 metal pieces (weighing 821 kg), 39 metal nails, 14 metal spikes, 52 pieces of metal cask hooping, two sections of slate board, opium related utensils, cooking-pot pieces, lead net sinkers and numerous pieces of charcoal (table 5.4). These domestic artefacts, combined with the approximate house location obtained from the land title document, suggest that further excavation in this area may reveal the presence of one or more dwellings (although no such features were found during excavation). 83

| Area 4 | Number of artefact fragments | Weight (grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Bottle glass | 216 | 894 |

| Window glass | 23 | 86 |

| Ceramic | 67 | 864 |

| Bone | 9 | 28 |

| Nails | 39 | 48 |

| Spikes | 14 | 598 |

| Cask hoop | 52 | 311 |

| Nondescript metal | 762 | 821 |

| Total | 1162 | 3650 |

Table 5.4 Main artefact categories by number and weight from excavation area 4.

Artefacts found in the tidal zone appear to have originated from a central position in front of area 4 and been washed east by incoming tidal movements. Compared to the rest of the shoreline, the section adjacent to area 4 has experienced an increased rate of erosion. Surface finds in this area included a broken, homemade, handheld pick of a modern style, probably left by artefact collectors.

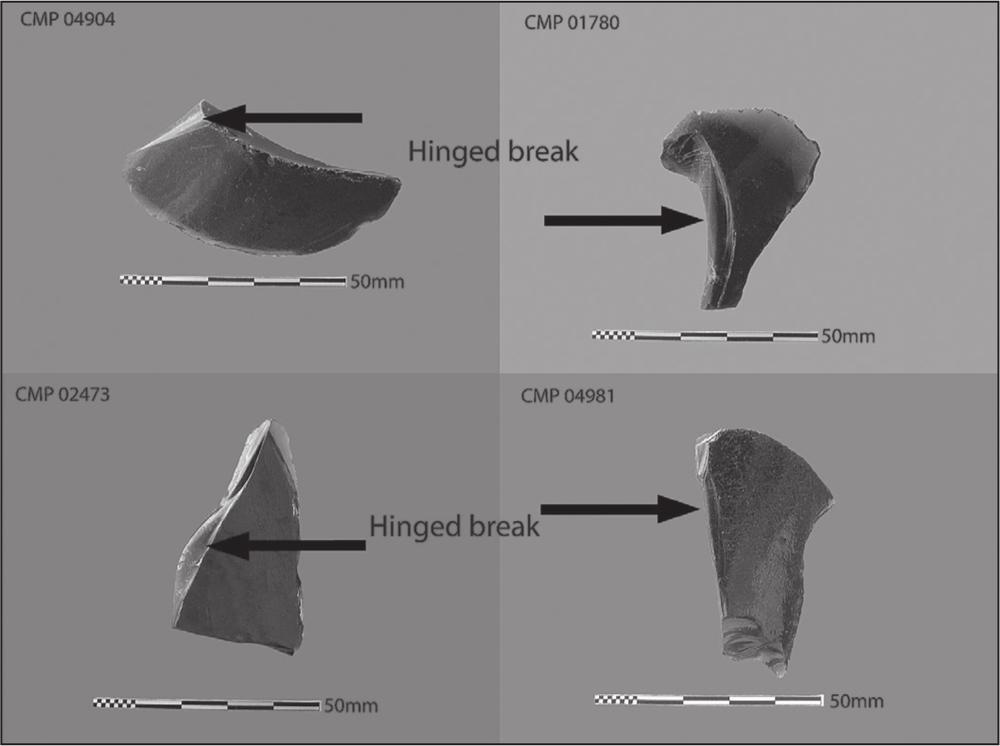

Breakage patterns in bottle glass found in the site’s tidal zone has been used in conjunction with other evidence to suggest that the tidal zone bordering area 4 may have been a rubbish dump for the site. Approximately 45% of glass bottle shards recovered from the tidal zone display a hinged breakage pattern (figure 5.16). Hinged breaks are indicative of heavy, slow, outwards pressure (Cotterell & Kamminga 1990: 146; Dibble & Pelcin 1995: 429), although can also occur as a flaking error during the manufacture of glass and stone tools. It is hypothesised that empty glass bottles were discarded on a rubbish dump and as rubbish accumulated the glass was subjected to the slow, heavy pressure that would cause these hinged breaks.

Figure 5.16 Bottle glass displaying hinged-breakage patterns.

In certain controlled experiments I conducted, a number of 19th-century square and cylindrical glass bottles obtained from a local market stall were subjected to long, slow, heavy pressure. Some bottles were placed in a vice at differing angles and slowly pressured – sometimes for days – until the glass broke. Other bottles had weight continuously loaded on top of them until they broke. Others were thrown against a wall, dropped on the ground or smashed with another object. While more scientifically controlled experiments would be useful to confirm the forces required to produce a hinged break in bottle glass, examination of the glass fragments confirmed Cotterell & Kamminga’s and Dibble & Pelcin, findings that hinged breaks occur in bottles that have been broken through slow heavy pressure.

84While Cotterell & Kamminga and Dibble & Pelcin experimented on flat plate glass in order to determine variability in flake morphology, experiments I conducted were on bottle glass in order to identify breakage patterns in discarded historical bottles. The long, slow, heavy pressure required to produce hinged breaks is consistent with the force applied to bottles in the middle or lower levels of rubbish dumps.

The hinged glass breakage pattern, the disturbed nature of area 4’s sub-surface layers, the increased bank erosion, the discarded pick and the density of surface artefacts led to the conclusion that this area was probably a rubbish dump positioned beside or behind the site’s residential area. This area has attracted the attention of bottle collectors and artefact scavengers who have dug at the bank and surface layers to retrieve material remains. The stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 4 can be seen in Figure 5.17.

Figure 5.17 Schematic diagram showing stratigraphy and Harris matrix for area 4 (not to scale).

Jetty remains

Through gently probing sub-surface layers within the tidal zone, a series of sub-surface post stumps were located, suggesting the remains of a jetty. Scientific analysis of the timber remains was not possible due to financial constraints. However, in this constantly wet environment the posts, including a series of milled hardwood stumps 150 by 35 mm (identified through timber hardnesss) and an assortment of tea-tree stumps from 40 to 80 mm diameter (identified visually through outer bark remains), were well preserved. The stumps lead out over the swamp area towards the deeper part of the channel. A jetty in this position would have allowed fishing boats to moor at the jetty and its occupants to walk over the swamp to the industrial site area.

Eight copper nails (used in boat construction as they do not rust) and 29 lead fishing net sinkers were recovered from surface and sub-surface layers of the site. Copper nails, net sinkers and the jetty remains suggest the site occupants probably had their own boats, fished with nets and took delivery of catches from other boats.

RESULTS

The excavation of the site and examination of ground features and artefacts enabled an excellent understanding of the site’s purpose and usage. The evidence shows that, while pursuing a livelihood from fish, the Chinese fished, bought fish, cured fish, constructed substantial infrastructure and, as evidenced in the gutter system, considerably altered the natural environment. The extent to which the site occupants themselves fished and their methods, remains unclear, although the presence of fishing-net sinkers and marine nails reveal that at least some of their activities involved the use of nets and boats.

The size of the drying rack suggests fish were cured on an industrial scale and that curing was done in the open air, unless new evidence comes to light suggesting the racks were enclosed or roofed. As few nails or fastening equipment were recovered from the drying rack area, the fish curers may have used traditional building techniques of mortice joints and lashing timbers together (Dumarcay 1991: 61). No fish scales and very few fish bones were recovered from the drying-rack area, suggesting that fish were scaled before drying 85and, if displaced from the rack, were considered valuable enough to be picked up and not left to rot on the ground.

Knowledge of whether fish was boned during the curing process is important for the future identification of fish remains from mining and other colonial-period Chinese sites in Australia. The Australian Town and Country Journal (1870, July 9) is the only located reference that suggests fish bone was removed, stating that at the Lake Macquarie Chinese fish-curing site “The smaller varieties [of fish] – such as perch, tailor, garnet, soles, herrings, &c, – are mostly converted into a kind of semi-liquid preserve”. All other fish types are:

taken in baskets to the splitting-table: and after being there opened, headed and the back bone removed, they are passed on to another part of the establishment.

Five other references regarding this stage of the curing process suggest that Chinese fish curers split the fish down the backbone (as opposed to removing the backbone) (Bendigo Advertiser 1857, January 5; The Argus 1864, May 28; Oliver 1871: 758; Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 1: 1224; Gippsland Standard 1944, July 7). For example:

the internal arrangement of the fish is partially removed, leaving the liver and roe attached, being cleverly split from the back. They are then thrown into a brine-cask and left for a few days. (The Argus 1864, May 28)

Some curing sites may have deboned their fish and not others. Alternatively, particular fish types only may have been deboned. Salmon (Arripis trutta) fish bone has been excavated from one colonial-period Chinese site at Butcher’s Gully in Victoria (Stanin 2004a), which, due to the site’s location (approximately 150 km inland from Melbourne), almost certainly represents a cured fish. At this time, no determination can be given as to whether fish was routinely deboned during the curing process. The discovery or absence of fish bone from future archaeological excavations at colonial period Chinese sites will help to answer this question.

Some metal fragment remains indicate that timber casks were present on the site. It is possible that casks were used for fresh-water storage, or to brine fish, or both.

The recovery of large amounts of Chinese artefacts suggests the site occupants had contact with people who traded in Chinese goods. Shipping records for the 1860s – previously discussed in chapter 4 – reveal that ships carried cured fish from Port Albert to Singapore and Hong Kong (Syme 1987: 321). Accordingly, it is likely some supplies came from Singapore and Hong Kong to Port Albert. Shipping records also show that cured fish was frequently shipped from Port Albert to Melbourne (Lennon 1973: 196), then probably taken to the goldfields.

Ample evidence of residential occupation of the site was recovered. However, as no remains of the dwelling shown on the 1888 land titles document are evident on the surface, in sub-surface layers or on the eroded areas of the site, the structure may have been a temporary or prefabricated structure. The Chinese use of prefabricated timber dwellings produced in China is noted in American colonial-period literature such as Borthwick (1857: 75) and Bowles (1866: 248–54). Also, Frost (1853: 100) states:

The houses they [the Chinese miners in California] brought with them from China and which they set up where they were wanted, were infinitely superior and more substantial than those erected by the Yankees, being built chiefly of logs of wood, or scantling [planks of timber], from six to eight inches in thickness … the roofs were constructed on an equally simple and ingenious plan and were remarkable for durability.

Similarly, Soule (1855: 387) writes of the Chinese in San Francisco: “Their dwellings, some of which are brought in frames direct from China and erected by themselves, are commodious … and [they] live very comfortably”. Accompanying the land title document of 1888 is the original hand-drawn surveyor’s plan of the Chinaman’s Point site in which the house is described as made of ‘palings’ (PROV, VPRS 5357/P0000, unit 5899). In Syme’s (1987: 207, 232, 246) compilation of Victoria’s shipping arrivals and departures during 1854 and 1855, there are several entries of ‘houses’ and ‘wooden houses’ among the cargoes exported from Hong Kong and Singapore to Melbourne. Therefore it is conceivable that the dwelling at Chinaman’s Point was a prefabricated Chinese structure imported to Australia and – in this case – possibly dismantled when the site was abandoned (during the colonial period timber houses were commonly relocated or dismantled to be reused for building material). The failure to locate any surface remnants of a domestic hearth area or the house itself may be explained through the dense site vegetation cover, site scavenging activities or a combination of both.

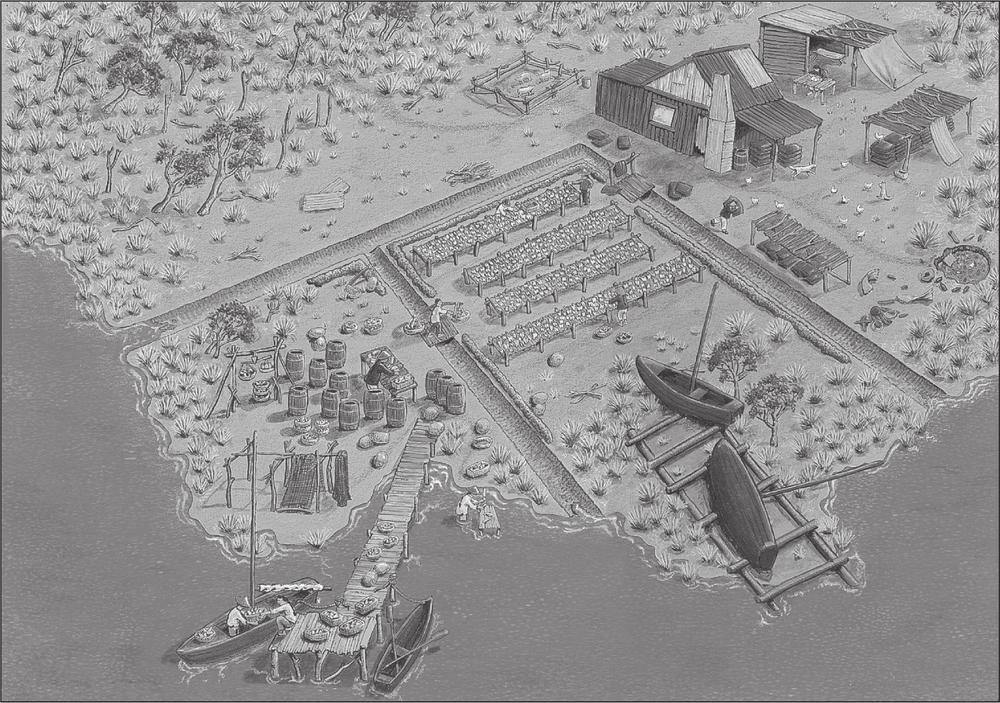

The artefact types, densities and positioning support the hypothes is that the tidal-zone artefacts originated from an eroded rubbish dump area, areas 1, 2 and 3 were industrial areas and area 4 was a domestic area (figure 5.18). Artefacts recovered from the surface collection are not considered to be in situ, but they do represent 86domestic and industrial components of the site. The jetty remains fit with the general documentary evidence to suggest that Chinese fish curers in colonial Australia had their own fishing boats and also took the catches of local European fishermen. As approximately only 3% of the site has been excavated, the land at Chinaman’s Point still holds considerable potential to reveal further information concerning Australia’s colonial Chinese fish curers and aspects of the industry they helped to create.

Figure 5.18 Site reconstruction based on archaeological and historical evidence. Painting by blaked beans design 2007.