CHAPTER 4

THE CHINESE IN VICTORIA’S FISHING INDUSTRY

A central argument of this investigation is that Chinese fish curers facilitated the development of Victoria’s colonial fishing industry. This chapter examines documentary information concerning Australia’s colonial Chinese fish curers to build a case for that argument (material remains are discussed in chapter 6). A range of hitherto unexplored questions concerning the activities of Chinese fish curers in colonial Australia are answered. For example, how extensive were their operations? During what period and where did they operate? Is there evidence for individual ownership of fish-curing establishments? Did Chinese people themselves fish? What were their fish-curing methods? Did their methods differ from non-Chinese fishermen? What were the market outlets? What quantities of fish were cured? Were good profits made?

Extensive desktop and field research in Victoria has recovered a good quantity of documentary information, mostly in the form of government literature, newspaper reports, diaries and oral histories. Many written histories and some scholarly works briefly mention the Chinese fish curers in Australia, including Cooper (1931), Hibbins (1984), Fitzgerald (1996), Williams (1999), Bennett (2002) and Hill (2004). Such literature often contains un-referenced information or is narrowly based on a few well-known newspaper articles or on the 1880 royal commission into the New South Wales fisheries. For this reason, this chapter predominantly uses primary sources, including an 1858 New South Wales Legislative Council report on Chinese immigration, 1861, 1879 and 1891 parliamentary debates on matters concerning the fishing industry, 1866 statistical returns from Tasmania’s House of Assembly, an 1871 and an 1883 government-funded report on the fisheries of New South Wales, 1880 and 1919 royal commissions into fishing industry activities, an 1892 royal commission on Alleged Chinese Gambling and Immorality, an 1892 Legislative Assembly progress report upon the fishing industry of Victoria and 52 separate Australian colonial newspaper reports. Further historical material yet to be discovered may in future shed new light on Chinese fishing activities in Australia. In order to provide an accurate description of Australia’s Chinese fish-curing industry, quotations from primary sources have been used as much as possible. Where necessary, the reliability or speculative nature of references will be assessed.

The most substantial academic comment on the Chinese fish curers in Australia is in Michael Lorimer’s 1984 masters thesis on the technology used in and practices of the New South Wales fishing industry from 1850 to 1930. However, Lorimer’s dissertation contains only one page of general information on the Chinese fish curers in colonial New South Wales and uses the 1880 royal commission and one newspaper article – the Australian Town and Country Journal (1870, July 9) – as a reference base.

The 1880 royal commission is the most informative and reliable source of information on the Chinese fish curers in Australia. Even so, royal commissions, parliamentary debate or official government reports must be considered in the context of the thinking of the period and possible individual prejudices of the authors.

New South Wales, Victorian and South Australian parliamentary debate also provide good evidence. Occasional references to the location and period of occupation of Chinese fishing sites can be found in government land tax and rate book records; although names – other than ‘Chinaman’ – are often unrecorded. Occupations, however, are frequently documented. General writings from the colonial period contain some useful information, but are often very subjective.

Chinese fish-curing establishments must have been a curious irregularity to the non-Chinese population. Perhaps for this reason, newspaper reports proved an abundant source of information about the role of Chinese people in Australia’s early fishing industry.

The Geelong Advertiser (1865, January 16) observes that the fishermen of Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay are “made up of Italians, Dutchmen, Frenchmen, Chinese, Maori and others”. The term “and other” would likely include British, German, Swedes, American, Greek and Australian Aboriginal people, all of who were involved in Australia’s colonial fishing industry. As these ‘other’ fishermen were mostly of European background, to distinguish Chinese fishermen from non-Chinese fishermen the term ‘European fishermen’ will be used, except in reference to Aboriginal fishermen. 47

LOCATION

New South Wales

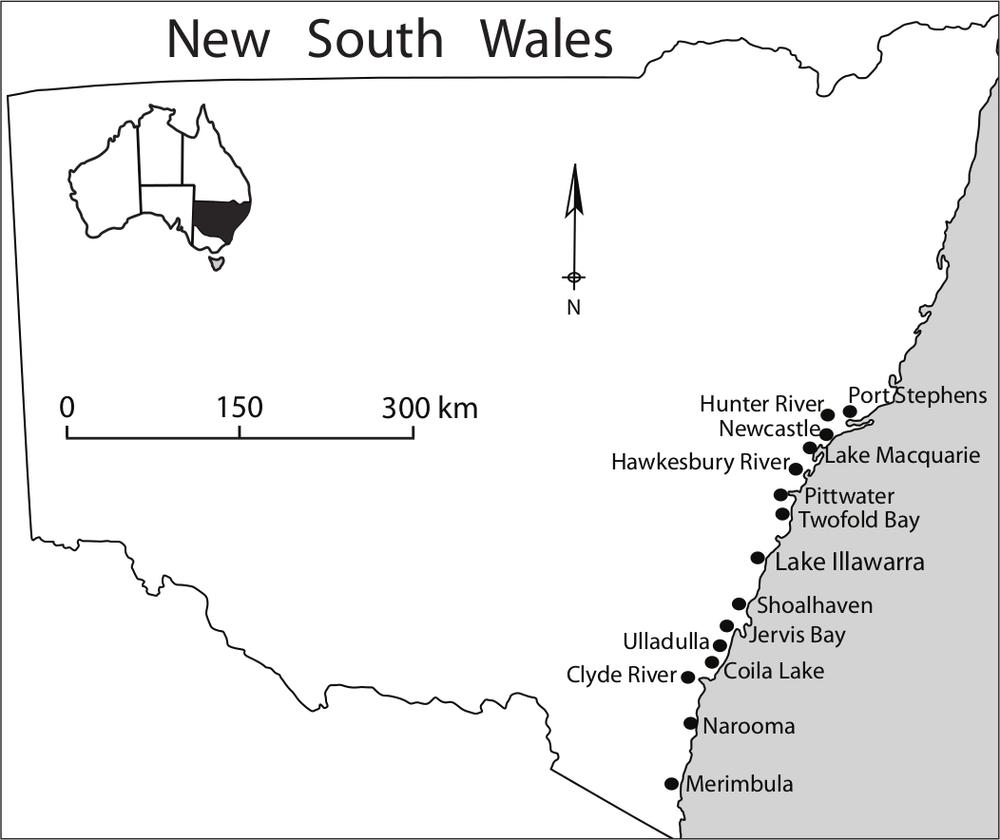

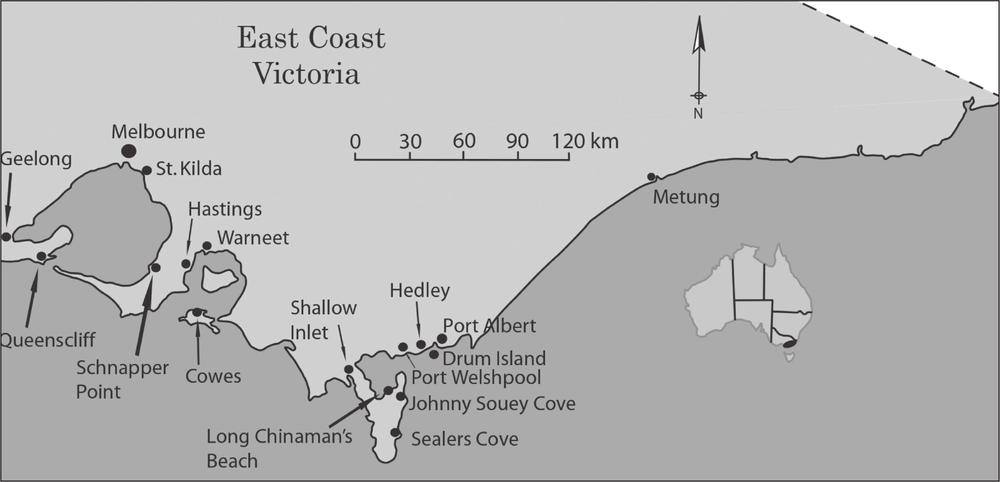

Documentary evidence from New South Wales, Victoria, the Northern Territory, South Australia and Tasmania indicates that Chinese fish curers were active in many Australian and nearby regions. Lorimer (1984: 93) suggests that when European fishermen from Sydney began to seek fishing grounds further from the metropolitan area, they often found large, already well-established Chinese fishing settlements. Parliamentary debate on Australia’s fishing industry mentions that, from the early 1860s, many coastal regions of New South Wales such as Port Stephens, Newcastle, Lake Macquarie, Lake Illawarra, Hunter River, Twofold Bay, Jervis Bay, Merimbula and Coila Lake had Chinese fish-curing establishments (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 1: 670–78) (figure 4.1). Scrutiny of the local histories and newspapers for these areas would undoubtedly reveal further hints of the Chinese fish curers’ presence. More direct evidence comes from a Chinese merchant, Chin Ateak (sometimes written Chen Ah Teak). When questioned by the royal commission of 1880, Chin Ateak states that approximately 20 years previously, he “had stations” himself and also received Chinese cured fish from other stations at each of the regions mentioned above (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1224). In addition to this, the Sydney Morning Herald (1861, April 6) noted that on the shores of Sydney’s Pittwater region there was “a small colony of Chinamen, who live in tents and are engaged in curing fish”.

Figure 4.1 Known Chinese fish-curing establishments in New South Wales. Based on newspaper reports and the 1892 royal commission into the fisheries of New South Wales.

These references suggest that Chinese people operated an extensive fishing industry in New South Wales during the colonial period. In 1871, Alexander Oliver, a former fisheries inspector, was engaged by the government to enquire into the industrial progress of the New South Wales fisheries. Oliver (1871: 789) reports that the fishing grounds between Sydney and Newcastle “once supported more than 200 Chinese curers” and gives their decline as a “consequence of the falling off of the Victorian demand for cured fish”. Later in this chapter, the approximate tonnage of fish handled annually by the Chinese fish curers in New South Wales is compared to that of European fishing activities, with very unexpected results.

Northern Territory

In 1873, goldmining activities in the Northern Territory were gaining momentum and supplies came mostly from Darwin – then known as Palmerston. Kirkman (1984) and Jones (1990) have undertaken well-referenced research on Chinese activities in this region. By 1874, Chinese people were mining extensively in the Northern Territory and, not surprisingly, a Chinese fishing and fish-curing industry was established at Palmerston (Jones 1990: 24). On 1 June 1878, The Northern Territory Times commented,

There are some people that are beginning to like John Chinaman – they get fish, prawns and fine vegetables, &c, which they could not procure awhile ago at any price.

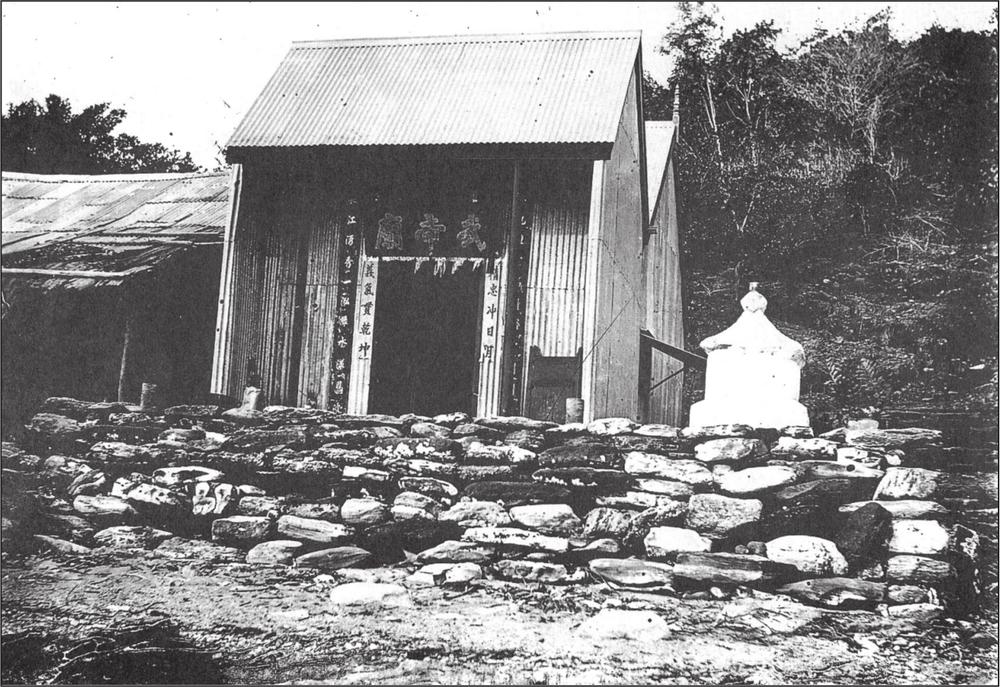

48The only known picture of a Chinese fishermen’s temple in Australia (known as Moo Tai Mue Chinese Temple), comes from Fisherman’s Beach at Palmerston, dated simply “before 1900” (figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 The Moo Tai Mue Chinese fishermen’s temple. The picture was taken in Darwin before 1900. Spillett Collection, Northern Territory Library.

Lack of water during the Northern Territory’s dry season slowed Chinese mining operations. At these times, the Palmerston Government often provided Chinese miners with relief work, which paid a small wage and food rations (Jones 1990: 23). Part of the weekly rations included 3 ¾ lb of salt fish. It is highly likely that this product was Chinese cured fish, revealing a situation possibly unique to Australia where the government purchased produce from Chinese fish curers.

South Australia

Chinese fish curers were active in South Australia from at least 28 May 1864, as evidenced in a column in The Argus:

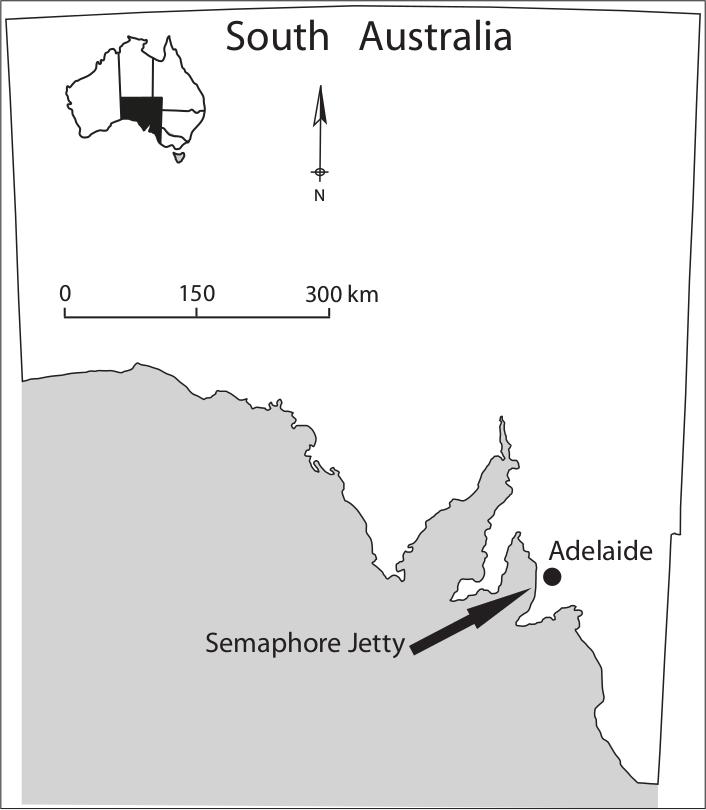

Fish Curing – Somewhat a novel exportation from South Australia to Victoria has taken place during the past few weeks … By the Coorong, from Melbourne, there arrived some two months back four Chinamen, who brought a boat and a remarkably long seine, with which they located close to the Semaphore Jetty … very many tons [of fish] have already been forwarded to the neighbouring colony, to be used as food by the Mongols on the various diggings … In addition, however, to this branch, that of schnapper curing is carried on by the same men, who received fresh accession to their forces by three more arriving by last week’s steamers.

This may be an example of a Chinese merchant using a ready supply of labour to test – and then if results were favourable, to exploit – a resource area. At the very least, the article from The Argus is good evidence that Chinese fish curers readily located themselves wherever there were fish and they did not – as did Europeans at the time – consider distance from market a constraint (figure 4.3). 49

Figure 4.3 The only known Chinese fish-curing establishment in South Australia.

Tasmania

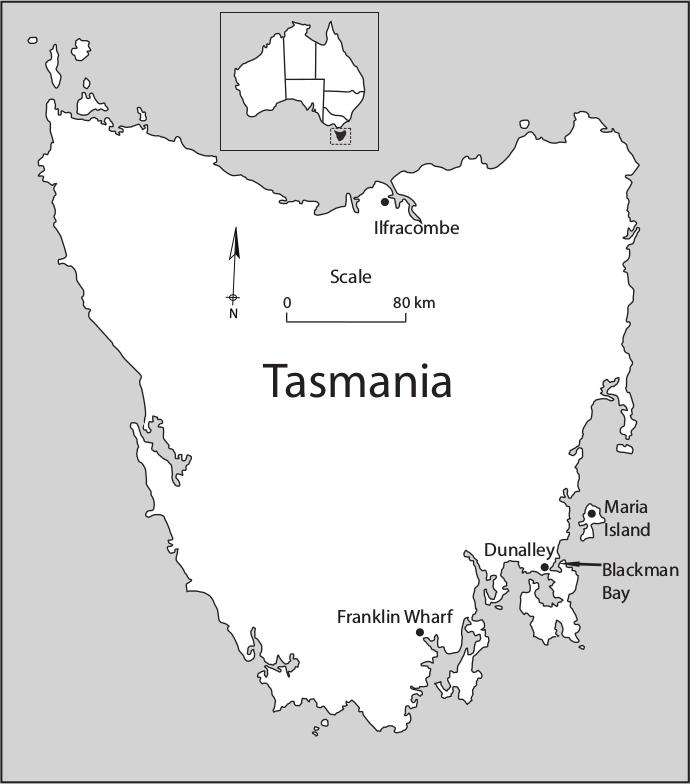

The main period of Chinese immigration to Tasmania was from 1875 to 1890 (Vivian 1985: 1), when Chinese people were attracted by gold and tin resources. Before this time, however, the Chinese had other interests in Tasmania. On 30 November, 1860, the Hobart Town Advertiser reported that near the Franklin Wharf “several” Chinese had “commenced curing cray fish for the Melbourne Market. These fish they either catch, or purchase from any one willing to catch them”. Parliament of Tasmania statistical returns (Votes and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Legislative Council 1886, vol. 13) show that in 1866, ₤460 of cured fish were exported from Tasmania to Victoria and ₤190 to New South Wales – revealing that the Chinese curers were making considerable sums from their industry. During this period European fishermen in Victoria averaged an annual wage of ₤250 (Gippsland Times 1879, May 21).

In June 1872, The Examiner wrote:

Ah You a Chinese fisherman, arrived from Melbourne with his party last week and he proceeded to Ilfracombe with the intention of establishing a fishing station and fish-curing depot in that locality.

Historical studies conducted by Harrison (2006: 1) on Maria Island revealed that Ah Sin Yung, Sing and Chan worked as abalone gathers and curers, sending the cured product to Victoria. Finally, the Tasmanian census of 1881 shows one Chinese fisherman and two fish curers working near Dunalley at the mouth of Blackman Bay (figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Known Chinese fish-curing establishments in Tasmania.50

Victoria

As this project focuses on Victoria’s Chinese fish curers, a comprehensive discussion of site locations is warranted. The earliest located evidence for Chinese involvement in Australia’s fishing industry – besides the trepang industry – comes from Victoria on 8 November 1856, when the Bendigo Advertiser reported that “It may not be generally known that several Chinese have established at St Kilda a fishery and fish-curing establishment”. Three months later on, 5 January 1857, the Bendigo Advertiser states,

The enterprise of the Chinese has of late displayed itself at St Kilda, Geelong and Schnapper Point in the establishment of curing-houses for the various fish found in the Bay.

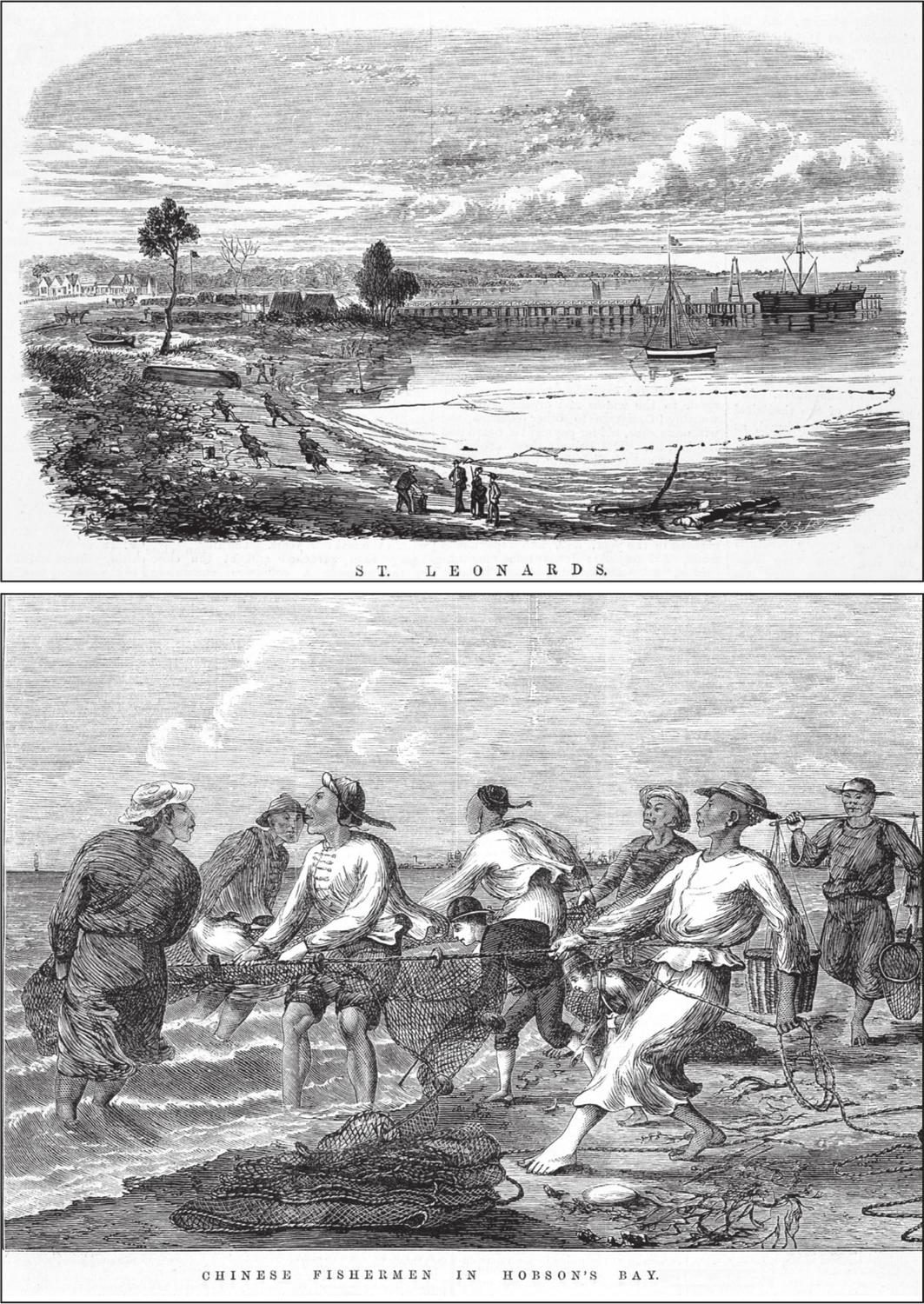

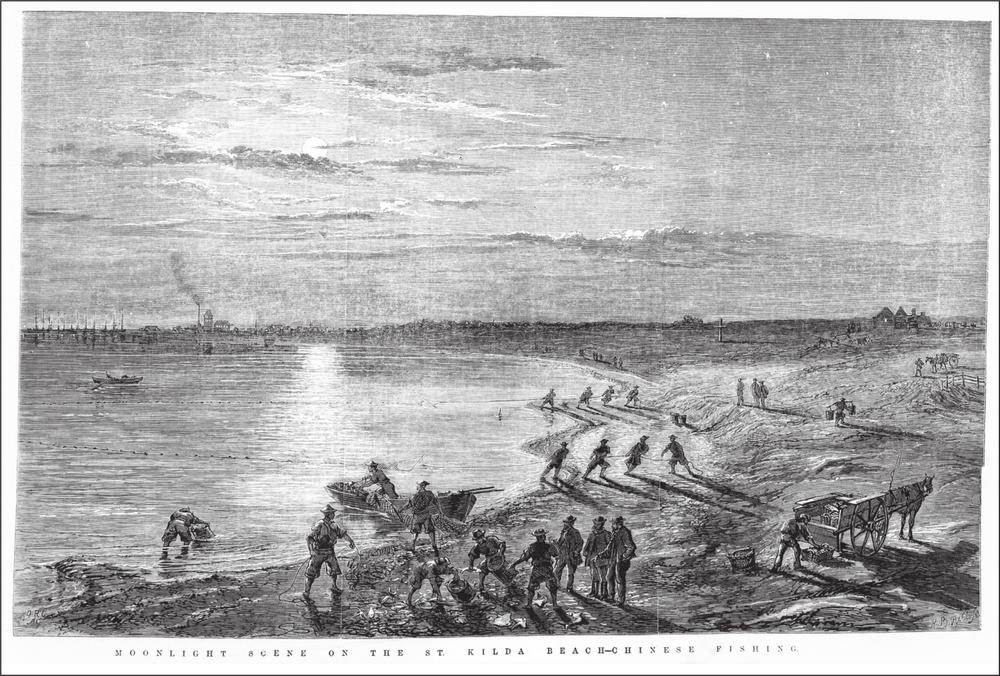

From early 1857, newspaper articles on Chinese fish-curing activities in Port Phillip Bay appear periodically (see for example the Geelong Advertiser 1857, January 12; 1862, November 1865, January 16; Illustrated Australian News 1866, September 20). Engravings of Chinese people hauling fishing nets onto the beach at St Leonards (Geelong) and between Sandridge and St Kilda appeared in the Illustrated Australian News (1870, January 24; 1873, December 4) (figure 4.5). The 1873 report stated the

party of Chinese fishermen pursuing their occupation on the beach … are not very communicative. They live cheaply; carry on their fishing, as well as all their other industrial pursuits.

Extensive field research around the shores of Port Phillip Bay has revealed no surviving material evidence of Chinese fish-curing activities.

Figure 4.5 Two wood engravings of Chinese fishermen hauling in seine nets, Victoria. The scene at St Leonards (Geelong) (top) appeared in the Illustrated Australian News 1870, January 24. The scene between Sandridge and St Kilda (bottom) appeared in the Illustrated Australian News 1873, December 4. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

51Surprisingly, no historical or material evidence has been located for Chinese people fishing on Victoria’s west coast, although it is likely the Chinese were actively fishing and curing fish in this region. Stan Evans (2003) undertook a history of this region’s fishing industry – with a focus on Port Fairy – in which no evidence of Chinese fishing activity was noted. In contrast, good quantities of historical evidence demonstrate the presence of Chinese fish curers along Victoria’s east coast.

Working predominantly from the oral histories of fishermen at Phillip Island, John Jansson (2004) documents that William Richardson, a Phillip Island fisherman in the 1870s, “bought his first boat from a Chinese fisherman who had a house on the foreshore land west of Cowes” (see location Figure 4.10). This information was corroborated during interviews for this study with third-generation Phillip Island fishermen Ted Walton, Les Findlay and Jim Osterlund. However, subsequent field research in the area was hampered by recent housing developments and no material evidence of Chinese fishing activities was located.

Wells (2001), quoting from the personal notes of Peggy Banks, an early resident in Victoria’s Warneet region, notes that

Chinaman Island to the south of Warneet is separated from the mainland by only a narrow channel … many years ago some Chinese fishermen lived and fished there … they dried them and sent them to China.

Although field research on Chinaman Island revealed colonial period material remains, there was nothing to suggest a Chinese occupation. The island’s name and oral history strongly suggest Chinese influence, although further evidence is required to confirm the presence of Chinese fish curers at this location.

Further east from Warneet, The Gippslander (1865, November 10) reported:

A party of Chinese last week started a fish-curing establishment on the beach at Hastings and on Wednesday last no less than two and a half tons of fish were taken there to be cured.

The place names Chinaman’s Creek, Johnny Souey Cove and Long Chinamen’s Beach suggest Chinese fishing people were also active around the shores of Wilson’s Promontory. In a written history of this area, Peterson (1978: 10) states that Long Chinaman’s Beach was named “in memory of six Chinese men who drowned in that Bay”, but unfortunately does not reference the information source (figure 4.6). More reliable written evidence of Chinese people fishing at Wilson’s Promontory comes from the Gippsland Guardian (1865, April 7) which states that on 12 April, the SS Ant “called at Sealer’s Cove and landed there a boat and a party of Chinamen”.

Figure 4.6 This presumably depicts Chinese fishermen at Long Chinaman’s Beach, Wilson’s Promontory. Image from Peterson 1978: 10.

On 19 January 1866, the Gippsland Guardian cited a case where the Collector of Customs was called out to investigate a complaint that Chinese men based at Shallow Inlet were fishing with “nets of a finer mesh than was allowed by law”. “A boat was dispatched to seize the illegal nets”, but on investigation, no unlawful fishing equipment was found and the complaint was put down to jealousy at the success of the Chinese fishermen.

Writing on the beginnings of Port Welshpool, Collett (1994) states that

Port Welshpool dwindled, until by 1871 it had only three houses and one tent, with 19 inhabitants, including four Chinese men who lived by the beach and the small jetty built in 1862, catching fish.

It is unfortunate that in this generally well-referenced book, Collett fails to cite where this information came from. Another reference for Chinese fish curers at Port Welshpool comes from the Gippsland Standard (1894, May 5), which reports, “there was a party of Queenscliff Chinamen fish curers came to Port Albert and Welshpool”. When interviewed in 2003 for this project, many of the old residents of Port Welshpool indicated 52that there had been Chinese fish curers living in the area. However, perhaps due to land development, field research revealed no material remains of Chinese activities at Port Welshpool.

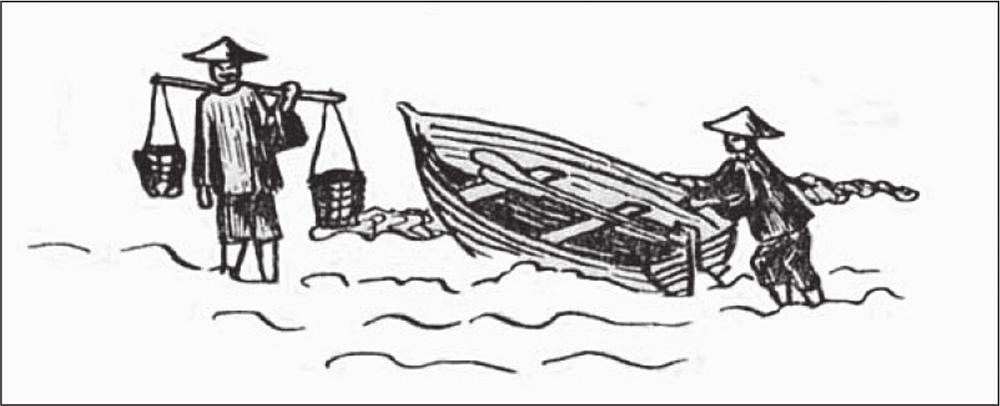

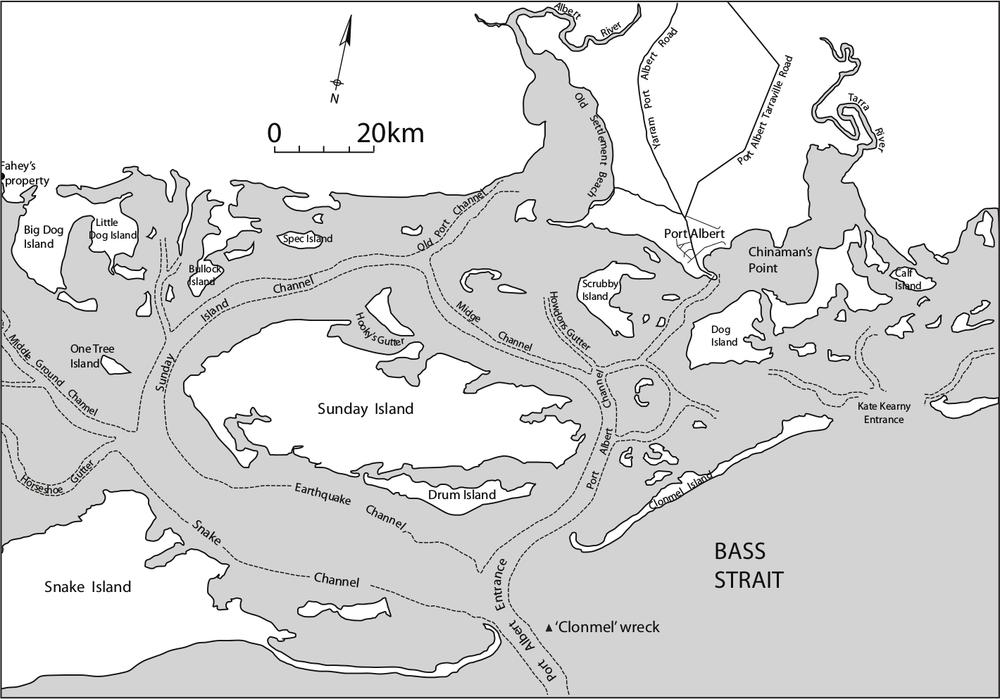

Efforts made in this project to locate physical remains of Chinese fishing activities have been hampered by scanty, misleading or lost written records. In view of this, collating oral evidence with field reconnaissance is often the best method of locating sites. Around the Port Albert waterways this was done with some success. Norie Rossiter and Jock Greenaway, both long term residents of the south Gippsland district of Hedley, gave oral evidence in 2003 of a Chinese fish-curing camp at Fahey’s Point slightly west of Nine Mile Creek (figure 4.7). Subsequent field research revealed a small quantity of colonial period material remains. No distinctly Chinese artefacts were located, however there was an assortment of timber post remains and three purposely dug ground trenches – approximately 600 mm wide, 600 millimetre deep and 7 m long – running at right angles to the shore line (figure 4.8). Local residents could not put a purpose to the trench system. However, over a year later in 2004, Jimmy Robinson – a third-generation south Gippsland fisherman – relayed that his father had told him Chinese fish curers sometimes salted fish in purposely dug trenches, such as those described above. A historically identified Chinese fish-curing site in Tasmania’s Dunalley region contains a trench system very similar to that described above (Ben Morphett 2006 pers. comm.). Very dense coastal tussock grasses at Fahey’s Point possibly hide the Chinese artefacts required to conclusively link this site with Chinese fish-curing activities. Archaeological excavation may also confirm Chinese occupation of the site.

Figure 4.7 Map of South Gippsland waterways showing Fahey’s Point (top left of map, labelled ‘Fahey’s property’).

Figure 4.8 Plan drawing of site at Fahey’s Point.

53Albert Clark, a third-generation Port Albert fisherman interviewed for this project in 2003, gave oral evidence of a Chinese fishing camp slightly west of Port Albert on Drum Island (figure 4.7 for location of Drum Island). Subsequent field research on the island revealed – through scatters of Chinese-type ceramics – definite evidence of Chinese occupation, although no evidence of fishing or fish-curing activities was apparent. Chinese people living so close to the Port Albert fish-curing establishment that is the subject of this research were almost certainly fishermen supplying fish to the curers and possibly also sending fresh fish to Melbourne markets.

A report in the Gippsland Guardian (1867, July 1) mentions a “familiarly known Chinaman” who “left his mates on Sunday Island and proceeded in a small boat to the Port [Port Albert]”. Sunday Island is only metres away from Drum Island and the two islands may even have been joined in 1867. Days later his boat was found anchored but empty in the mouth of Kate Kearney Channel and it was assumed the Chinaman had fallen overboard and drowned. Police made enquiries and it was discovered, “in about four feet of water at low tide … the Chinaman had found his way to some of his own countrymen who reside on the island”. This report indicates first, that there were Chinese people living on Sunday Island. As Sunday Island had no freshwater supply it is unlikely they were market gardeners and so quite likely were fishermen. Secondly, the phrase “some of his countrymen” implies a group of – or at least more than two – Chinese people were living on one of the several islands near Kate Kearney Channel, which is the eastern sea entrance to Port Albert (figure 4.7 for location of Kate Kearney Channel). Both Lennon (1973: 197) and Peterson (1978: 9) suggest that Chinese people had fishing camps on many of the islands between Wilson’s Promontory and Port Albert, but it is not known where they obtained this information.

The Port Albert Chinese fish-curing establishment – the focus of chapters 5, 6 and 7 – originally came to my attention through oral evidence and was located through subsequent field research. Associated historical literature and material evidence for this site will be discussed in detail in the following chapter.

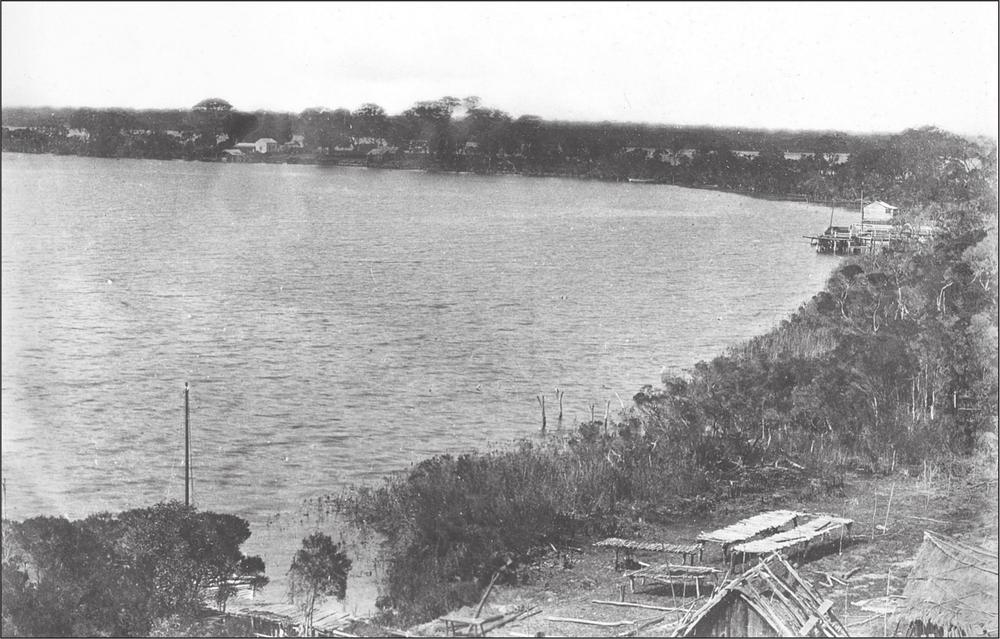

One of the very few examples of pictorial evidence for a Chinese fish-curing camp in Victoria – or Australia more broadly – is an 1886 photograph of an establishment at Metung, formerly Rosherville (figure 4.9). A reporter for the Gippsland Mercury (1879, May 20) visited the camp, stating “and here we saw a Chinese fishing camp … the men were civil and obliging enough and showed us a lot of fish”. The Bairnsdale Advertiser (1955, September 5) ran a series of articles written by an early resident of Metung, Rowland Bell. Bell writes that one of the Metung fishermen “was a Chinaman named Ah Sing”. In October 1928, Bell wrote an article for the local Metung paper Every Week in which he notes the Chinese camp was “the fishing camp of Ah Sing and Co.” and goes on to mention there were “six Chinese” working and living there.

Figure 4.9 This NJ Caire photograph c. 1886 of Shaving Point, Metung, probably unintentionally captured part of the Chinese fish-curing establishment, identifiable predominantly through the low fish-drying racks visible in the right portion of the picture, but also through newspaper reports and oral histories. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

54When interviewed by Ellis & Lee (2002: 32), Jack Allen, a third-generation Metung fisherman, stated:

there were quite a few Chinese around Metung [approximately 1860 to 1900]. I’ve heard my grandfather talking about them too. He said they’d sing as they hauled their nets in. There’d be four or five of them on the end of the nets, singing away in Chinese.

Again in Ellis and Lee (2002: 46), Bill Farquhar a former fishermen of the Gippsland lakes, said,

Old Joe Bull, he’d tell me about how the Chinese used to carry these great big heavy baskets of fish … in Bancroft Bay and the little creek up in the corner of it, we found all these fish scales many feet deep. Where the Chinese had sat … and scaled them.

Another third-generation Metung resident, Peter Bury, interviewed in 2003 for this project, also claimed to have seen these fish scales and gave what he believed to be their exact location. However, extensive auger test pitting in this region revealed no evidence of fish scales or Chinese fishing activities. This may be due to the constantly shifting bodies of sand moving the location of the evidence or possibly because oral history is not always precise.

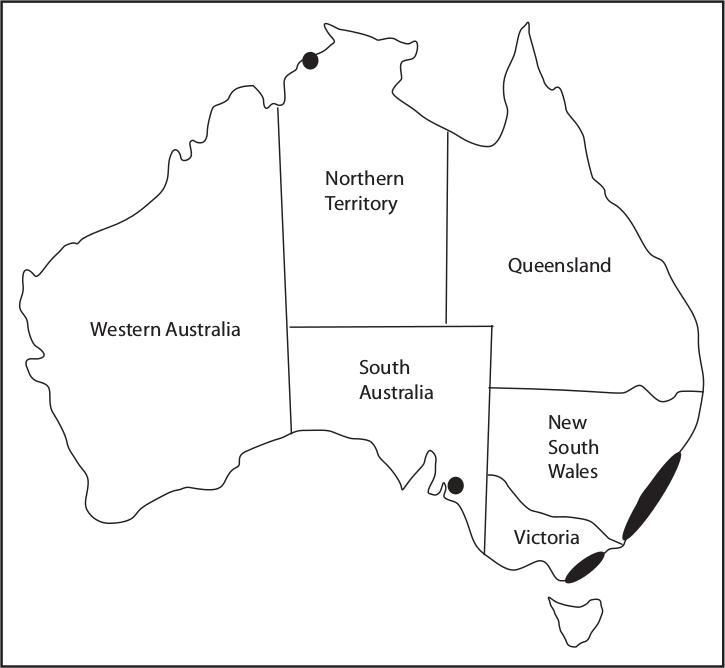

There is unambiguous evidence of 11 Chinese fish-curing establishments in Victoria and suggestions of a further five (figure 4.10). Solid historical evidence for Chinese fish-curing activity in New South Wales, Northern Territory, South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria (figure 4.11), leaves no doubt that Chinese people were heavily involved in Australia’s colonial fishing industry. As further historical evidence is recovered, the locations of other Chinese fish-curing establishments in Australia are likely to be identified. Wheelwright (1861: 248) wrote of Victoria: “on every [European] fishing station along the coast Chinamen are camped, who buy the fish from the boat and salt them on the spot”.

Figure 4.10 Location of known and inferred Chinese fish-curing establishments in Victoria. Based on newspaper reports, local histories, field reconnaissance and the 1892 select committee upon the fishing industry of Victoria.55

Figure 4.11 Darkened areas indicate known regions of Chinese fish-curing activity in Australia.

INTERNAL STRUCTURE

The labour structures i.e. owner/employer and headman/labourer relationships of Chinese fish-curing establishments in Australia may never be entirely understood. Nevertheless, by working through the available literature, some basic knowledge can be ascertained.

When The Argus (1864, May 28) reported on Chinese fish-curing activities at Semaphore in South Australia, it was noted that

There appears to be one amongst them who directs the whole operation and whenever any inquires are made he, in rather indifferent English, is remarkably willing to afford information.

This suggests – at least at this establishment – that the common Chinese practice of a headman overseeing operations was observed among fish curers. As this particular headman spoke a little English, he may have been an aspiring merchant already on the lower rungs of this class.

In the Australian Town and Country Journal of 9 July 1870, a reporter describes the Chinese fish-curing camp at Lake Macquarie – established in approximately 1863:

I arrived at the house of Mr. Ah Tie (the principal boss of the whole concern) … From the lips of Ah Tie I learnt that altogether there are about 17 Chinamen engaged in the work of catching and curing fish on the lake. Of this number nine are under the leadership of Mr Ah Tie, while the remaining eight acknowledge as their chief a highly intelligent-looking individual rejoicing in the name of Hop Lung. The respective parties of Messrs. Ah Tie and Hop Lung live about half-a-mile apart.

Separate camps probably represent different Chinese kinship association groups or possibly members of the same kinship group owned or financed by different Chinese merchants. Again, the apparent ability of the headman to speak English suggests that Ah Tie may have been a (lower-class) merchant.

The living arrangements at the Lake Macquarie camp appear unusually attractive:

They [the camps] have each two or three very comfortable slab cottages, well lined and shingled and perfectly weather tight, which is more than can be said of all the European dwelling-houses on the lake.

This suggests that the headmen of these camps may have had some wealth themselves or a generous merchant financer. Further evidence of a possible higher authority is the mention of Ah Tie’s “account-book, into which every consignment of fish was duly and carefully entered”. Account books are common business items but – particularly given the care with which Ah Tie maintained his accounts, it is conceivable that Ah Tie had a superior to whom he reported business quotas, dividends or commissions. Should any such written records survive, they would provide an invaluable insight into Chinese fish-curing activities in colonial Australia.

The Sydney Morning Herald (1861, April 6) reports that Sydney’s Pittwater region had a “colony of Chinamen, who live in tents and are engaged in curing fish”. Anderson (1920: 174) expands on this – presumedly through oral history – by indicating that the fish-curing camp “belonged to a Chinese firm … The 56manager Ah Chuey was a Chinese gentleman, much respected by residents”. This suggests the camp was part of a larger business and Ah Chuey was almost certainly a kinship or district associate of the business owner. Although Ah Chuey’s exact employment details are unknown, it is likely he was placed as headman at the fish-curing establishment by his employer. This would have given him an income and an opportunity to become a merchant himself. In 1861, the Chinese labourers at the camp were quite likely to have been under credit–ticket obligation to Ah Chuey’s employer.

Evidence of fish-curing establishments being owned by Chinese merchants and of labourers working under an obligation to their employer can be found in the 1880 royal commission. T Curtis, a fisherman, was asked, “You were fishing a long time at Port Stephens and there were Chinamen there that took your catch?” Mr Curtis replied “Just so”. Mr Curtis was then asked, “Were those fish despatched to the diggings, or to Chinese merchants in Sydney for despatch there?” Mr Curtis answered, “Both ways; one Chinaman that I was fishing for belonged to a Melbourne merchant” (Votes and proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1880, vol. 3). This suggests that the Chinese fish curer was working under some form of ownership or obligation, quite likely the credit–ticket system. The fact that he was working at Port Stephens but “belonged” to a merchant in Melbourne demonstrates that distance was not a major obstacle to Chinese fish-curing activities in colonial Australia. It may also show that credit–ticket labourers could be farmed out to merchants in other parts of Australia – as described by Omohundro (1977: 116), for Chinese labour organisation in the Philippines (previously discussed in chapter 3).

In the royal commission (1880: 1224–26), the Chinese merchant Chin Ateak provides further evidence of merchant ownership of fish-curing establishments. The questioning begins:

[Q] What is your name? [A] Chin Ateak. [Q] You are a merchant? [A] Yes. [Q] We want to ascertain something of the fish trade; you have had something to do with it, have you not? [A] Yes. [Q] For a long time? [A] Yes. [Q] Will you mention when it was you carried on the trade and where? [A] Port Stephens, Lake Macquarie, Jervis Bay and Merimbula – Twofold Bay, before we put a station there to catch fish. [Q] At all those places you had stations to procure fish? [A] Yes.

The wording “before we put a station there” suggests Chin Ateak was working with other people, but his relationship to these people is unclear. Regardless, it is unlikely that Chin Ateak worked at all these establishments himself and must have had others administering and labouring for him.

The questions continue:

[Q] That is some years ago? [A] Yes, nearly 20 years ago. [Q] And when did you give them up? [A] I gave them up, oh, long ago – nearly eight years ago [approximately 1872]. [Q] But you had some Chinese fishers? [A] I had at some places Chinese fishermen and at some places the Europeans.

Chin Ateak’s answers suggest that he owned these camps.

From the information available, it can be ascertained that, at least in some cases, Australian Chinese fish-curing establishments were most likely owned by Chinese merchants who staffed their operations with a headman and a team of working-class labourers. In one instance only – the 1880 royal commission – does the evidence suggest an indebted labourer worked at a Chinese fish-curing establishment. Until further evidence comes to light, this remains the principal evidence for merchant use of indebted labour in the fish-curing industry.

Chin Ateak’s exit from fish-curing activities in the early 1870s is consistent with an increase in Chinese market gardening at this time. After the 1870s, Chinese gardeners had an advantage over fish curers, as garden produce could be sold to European customers, whereas Chinese cured fish had no European demand. For example, the 1880 royal commission states the Chinese fish curers at Nelson Bay “catch their own fish here and preserve it after their own detestable fashion” (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1135). When the same royal commission interviewed the fisherman G Newton, he was asked, “Do you know whether their preserved fish are purchased or liked by Europeans?” He answered, “I do not think so; they are not fit for Europeans … anybody who saw the Chinamen cure the fish would not, I am sure, eat them” (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1200). In 1871, a government official, Alexander Oliver, reported on the condition of the New South Wales fisheries, stating:

The mode of curing adopted by the Chinese, however relished by their countrymen in Victoria, is sufficiently revolting to European tastes to exclude the article from general consumption … the flesh in the dried state is always more or less cheesy (1871: 785)

57With a declining Chinese population in Australia and no European market, Chinese fish-curing establishments became less viable. Oliver’s (1871: 789) comments in this regard are illuminating:

Those [fishing grounds] near Lake Macquarie only a few years ago gave occupation to several gangs of Chinese curers and would do so now, but that this industry … is in a very depressed state in consequence of the falling off of the Victorian demand for cured fish.

In questions answered by Chin Ateak during the 1891–92 Royal Commission on Alleged Chinese Gambling and Immorality – almost a decade after the royal commission into the fishing industry – the change in preferred Chinese economic activities can be clearly seen (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1891–92, vol. 8). The questioning starts:

[Q] What business are you in? [A] I keep a lot of gardeners. [Q] How many Chinamen have you in your employ? [A] I used to have half a dozen in some places, a dozen in others and smaller numbers elsewhere; about fifty altogether. [Q] How much do you pay them? [A] I give each man ₤40 a year, except the head man, who gets ₤50. [Q] And they feed themselves? No? [A] I pay for their food too. It costs about 10s a week per man.

Chin Ateak’s move from fish curing into market gardening reflects the general decline in fish-curing activities after 1870 and the ability of Chinese merchants to adapt to the economic circumstances at hand.

Chinese fish curing did persist in Australia – although on a smaller scale – well after the 1870s, as will be shown at the Port Albert site and as is evident in an 1891–92 royal commission into the fisheries of New South Wales. In this report WM Boyd, the Assistant Inspector of Fisheries for Lake Macquarie states, “There is only one camp of these men [Chinamen], five in number, with one boat, who send their fish to Sydney and Newcastle” (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1891–92, vol. 7: 294). As far as can be established, this was the last group of Chinese fish curers operating in New South Wales, a stark contrast to earlier periods when the fishing grounds just between Sydney and Newcastle “once supported more than 200 Chinese curers” (Oliver 1871: 789). How many individual fish-curing establishments this represents is difficult to determine. Nevertheless, some indication of the number of Chinese people required to work a Chinese fish-curing establishment can be ascertained.

When a reporter for the Illustrated Australian News visited the Chinese fish-curing establishment at St Kilda Beach on 4 December 1873, he noted “The fishermen number about 16”. At Lake Macquarie in 1870, Ah Tie had nine Chinese workers at his curing camp and Hop Lung had eight (Australian Town and Country Journal 1870, July 9). At Mount Eliza in Victoria, the Bendigo Advertiser of 7 March 1857 reported “four Chinese established themselves in the neighbourhood as fish salters and curers”. At Schnapper Point in Victoria in 1857 there were “forty men (all Europeans or Americans) engaged in catching schnapper and selling them to the two Chinamen who reside there” (Bendigo Advertiser 1857, January 5). The curing site at Semaphore Jetty in South Australia had seven Chinese people working there (The Argus 1864, May 28). From this information, it appears that at establishments where Chinese people fished and cured fish, up to 16 Chinese workers could be employed, but for operations that only cured fish, two to four Chinese people were sufficient.

Some evidence exists to suggest that after the 1870s, fish-curing establishments tended to be owned by individuals or groups rather than by merchants who controlled headmen and labourers. This is also the case for Chinese market gardens, as argued in chapter 3.

In Wilton’s (2004: 27) discussion on Chinese market gardens in Victoria, she suggests that after the 1870s,

Often, a market garden was set up as a cooperative venture between a number of men. This meant that as one partner returned to China or moved on to seek other work, someone could be brought in to replace him.

Using oral evidence, Williams (1999: 42) suggests that during the late 1800s, Sydney’s Chinese market gardeners were also pursuing cooperative venturers:

Most of these gardens were leased by groups of 5 to 10. Such arrangements suited people who would go to China for a year or two. When they did so their share was passed on to another gardener and taken up again on return.

The 1880 royal commission into fisheries reports that in New South Wales, “A considerable gang of Chinamen is always located at Nelson Bay and as soon as one lot returns to its native country another takes its place” (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1135). While the evidence is not conclusive, it seems likely that, as merchants abandoned their interests in cured fish, some fish-curing operations may have been taken over by individuals or groups and run along the same lines as Chinese market gardens in Australia. 58

CHINESE FISHING AND FISH CURING

Most written histories assume that Chinese fish curers in colonial Australia did not fish themselves, but instead purchased fish from European fishermen (see for example Hibbins 1984: 46; Fitzgerald 1996: 69; Bennett 2002: 9). As was noted in chapter 3, this was largely not the case. The other common misconception is that Chinese fish curers smoked their fish (see for example Halstead 1977: 32; Synan 1989: 161; Collett 1994: 50). Primary documentation confirms that Chinese people did fish commercially in colonial Australia and indicates that salting and pickling were the main methods used to cure fish. Material evidence for this will be examined in chapter 6.

For comparative purposes, Ward’s (1954: 202–03) account of fishing methods in China in the 1950s is instructive. Ward indicates the most common form of fishing in China, that she witnessed, was netting from boats, principally purse-seining where fish are encircled by a net and long-lining, however,

almost all fishermen from time to time will engage in hand-lining and trapping … They do their fishing in pairs and usually by night … bright kerosene lights are used to attract the fish.

Diamond (1969: 13) notes that Chinese fishermen in Taiwan most often use a beach seine. A boat is used to encircle fish with a net some 900 ft long and the boat then rows back to shore where the net is hand-hauled by long ropes onto the beach.

When the reporter for the Australian Town and Country Journal (1870, 9 July) visited Ah Tie and Hop Lung at Lake Macquarie, he noted:

Attached to the fisheries are four long-boats of about 18 feet keel and any number of nets, the construction of which is rather peculiar, inasmuch as they can be used separately in shallow water, or unitedly in deep water, interlinked together so as to form one immense net.

The Argus (1864, May 28) reports the Chinese fish curers at Semaphore, South Australia had “brought a boat and a remarkably long seine”.

The Illustrated Australian News (1873, December 4), in an article on Chinese fishermen at St Kilda, reports:

Net fishing is what they are engaged in at the moment – a style of fishing in which our Mongolian immigrants appear to be most at home. The nets vary in length from forty to eighty fathoms [264 to 480 ft] having inch mesh … The fishing is chiefly carried on at night, or early morning.

This article also contains a wood engraving of Chinese fishermen hauling a net onto the beach at St Kilda (figure 4.12).

Colonial-period literature often blames Chinese fishermen for destroying fishing grounds by using toosmall net mesh, which “destroy large quantities of the spawn and young … and a hundred times more fish than they caught” – and nets that are too long (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 1: 678). This criticism can be seen to varying degrees through the 1880 royal commission. For example, Richard Seymour, Sydney’s Inspector of Nuisances and the auctioneer in charge of the Eastern Fish Market was asked by the royal commission (1880, vol. 3: 1151) if the Chinese fishermen in New South Wales were harmful to the industry. Seymour answers:

[A] Well, the fishermen during the winter months generally grumble about the Chinamen, because they pick up a class of fish they have no right to. [Q] How do they fish? [A] With nets. [Q] Have you heard that they fish with six nets together? [A] I have heard so.

The same committee asked Hugh Logan, a New South Wales fisherman, if

[Q] The young fish are put back in the water [by Europeans]? [A] Yes, – although the Chinamen are doing more to injure the fishery trade than any people on earth; they are catching all the small fish, sweeping them up with the close [seine] nets. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1265)

A fisherman, William Boyd, answered in a similar fashion:

[Q] I suppose it is chiefly net-fishing in Lake Macquarie? [A] Yes, principally … The way those Chinamen slaughter them with their nets, when they get fishing, is something frightful. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1256)59

Figure 4.12 B Robert’s engraving Chinese fishing by moonlight c. 1873. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Boyd goes on to give the most detailed description so far located regarding the manner in which Chinese fishermen used fishing nets in colonial Australia. He also suggests that European fishing methods were equally as damaging to fish stocks as those used by the Chinese. The question was asked:

[Q] But did they [the Chinese] use the small mesh? [A] The smallest mesh was a 2-inch mesh, not as small as Europeans use. [Q] What sort of net did they [the Chinese] use? [A] About 300 fathoms long [1800 ft] and 30 feet deep in the bunt. [Q] And they passed that round the fish in the deep water? [A] Yes … They would shoot down between 30 and 40 feet of water and then the net would sink down until they came to shallow water. [Q] Did they sink the net in deep water and haul it into shallow water? [A] Naturally it would sink itself. It was not corked the same as our nets. [Q] And they used to pull it ashore? [A] Yes; ten men hauled it, five on each side. They would shoot out of two boats … and then they would haul into the land, on the beach. [Q] Do you think that lessened the numbers of the fish very much? [A] Oh, bless you yes. You can only catch small schnapper now; but our fishermen cause more destruction to the lake than the Chainmen did, with those small meshes; they have ruined the lake. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1257)

In these instances, Chinese fishermen appear to have used a similar method to net fish as was used in China. The description of Chinese fishermen sinking a net fully before dragging it to shore differs from European methods only in that during Australia’s colonial period, European fisherman used net floats to keep a portion of their nets on the water’s surface. Other fishing methods used by Chinese fishermen in Australia, as reported in the various government documents and newspaper reports, appear similar to European methods of the times. Both Chinese and European fishing techniques appear to have been detrimental to fish populations.

60The Illustrated Australian News (1873, December 4) reports on the species of fish that the Chinese in Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay were catching: “The fish caught by them [Chinese fishermen] are mostly flounders, garfish, flathead, salmon trout, silver fish and mullet”. The Australian Town and Country Journal reporter (1870, July 9) at Lake Macquarie states that

[The] principal kinds of fish cured by the Chinamen are schnapper, bream, whiting, flat-head and mullet; but Messer. Ah Tie and Hop Ling are not at all particular and it is very rarely that they catch a fish they cannot make use of in one form or another.

The evidence shows that Chinese curers were procuring a portion of the fish they cured by fishing, themselves, with nets.

Firth (1946: 13, 14), Inglis (1975: 71) and Omohundro (1977: 115) have noted that in regions other than China overseas Chinese people often employed locals as basic labourers. In colonial Australia, Chinese fish curers supplemented their own catches by purchasing fish that Europeans had caught with nets and by line and hook. Oliver (1871: 788) notes that in New South Wales,

there are and will continue to be found, prolific fishing grounds without number, many already known to the schnapper and net fishermen, who, at various times and often in most unexpected places, have plied their trade for the supply of Chinese curers.

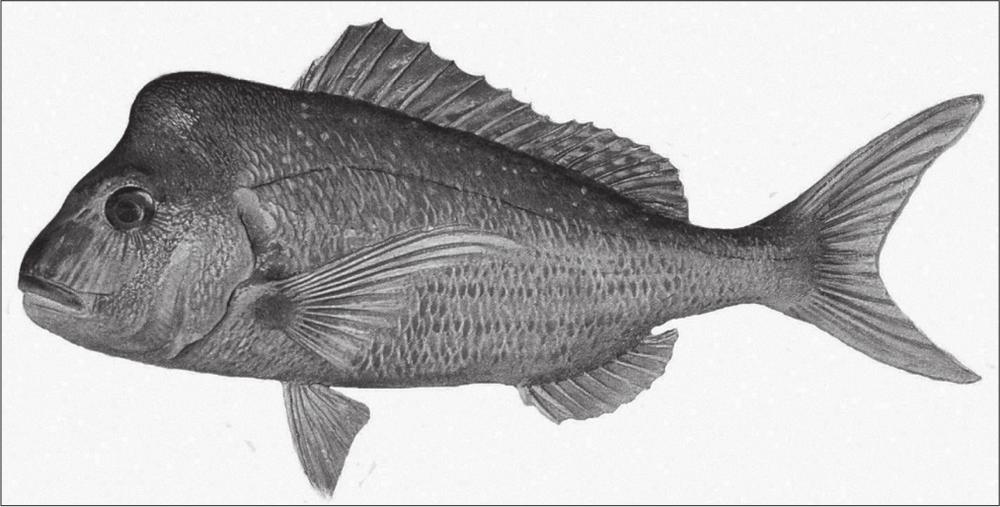

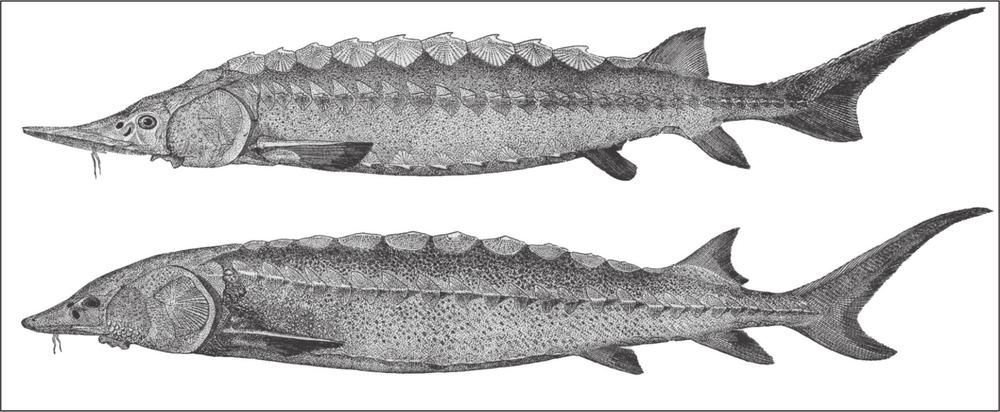

Schnapper (figure 4.13) is caught predominantly by line and hook and, as will be shown, was highly desired by Chinese people in colonial Australia. As far as can be ascertained, the Chinese fish curers did not engage in line fishing for schnapper themselves. Rather, they purchased schnapper from European fishermen, perhaps because the resource-intensive nature of line-and-hook fishing made it more economical to use local fishermen for this task.

Figure 4.13 The Australian schnapper (Chrysophrys guttulatus). Image from Roughley 1953: 76.

When fisherman Thomas Curtis was interviewed for the 1880 royal commission he was asked:

[Q] Can you give us an idea of what line fish you could have got in the early times, or even now for the Chinamen? [A] I did very well with the Chinamen there. Some days 18 or 20-five dozen of schnapper and other days from three or four or five dozen. It always paid. [Q] The Chinamen only took a limited quantity? [A] As many as we could catch. [Q] If ten boats could have fished there the Chinamen would have all the fish that were caught? [A] Yes. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1181)

Fisherman Michael Salomon was then interviewed:

[Q] Did you ever fish for the Chinese? [A] Yes. [Q] You were largely engaged at one time schnapper-fishing? [A] For the Chinamen – Yes. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1186)

George Newton gives a similar story:

[Q] Have you ever been engaged in the services of Chinamen? [A] Yes. [Q] What fish did you catch for the Chinamen? [A] Schnapper principally. [Q] How many fishermen were engaged in that occupation? [A] I have known as many as about 20 boats to be engaged by the Chinese [in Broken Bay, NSW]. [Q] Would they take all the fish that you brought to them? [A] Yes. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1200)

The same pattern of European hook-and-line fishermen selling to Chinese curers was apparent in South Australia, as reported in The Argus (1864, May 28):

In addition, however, to this branch, that of schnappers-curing is carried on by the same men [Chinese men] … In order to procure a better supply, all fish that comes to their net, as well 61as any other kinds purchasable at ₤6 per ton. This offer enlisted some Europeans, who have driven a fair trade in consequence, bringing to the Semaphore Jetty beautiful samples of the finer description of schnapper.

In Victoria, the Bendigo Advertiser (1857, January 5) reports that

The enterprise of the Chinese has of late displayed itself at St Kilda, Geelong and Schnapper Point in the establishment of curing-houses for the various fish found in the Bay … At Schnapper Point this singular people appear to be conducting this branch of industry on a large scale. Not less than a dozen boats with crews from 20 to forty men (all Europeans and Americans) being engaged in catching schnapper and selling them to the two Chinamen who reside there.

Chinese fish curers were procuring – through a purchasing arrangement – a significant number of schnapper from European fishermen. The quantities of finance generated by European fishermen and Chinese fish curers will be discussed in the ‘Economics’ section of this chapter.

Chinese fish-curing methods

Other fish were just as important to the Chinese curers as schnapper. The desirability of different sorts of fish depended to a large degree on how well they cured. Chinese methods of curing also varied according to fish type.

In the 1880 royal commission the Chinese merchant Chin Ateak gives an insight into the types of fish Chinese curers preferred for curing and their methods of curing:

[Q] Was it any particular kind of fish? [A] Yes, some schnapper and net fish. [Q] All mixed together? [A] Not all mixed. [Q] You separated them? [A] Yes. [Q] And those were salted and dried I suppose? [A] Salted and dried; some dried and some they call pickled fish, put in a cask or barrel. [Q] What are considered the best fish for salting? [A] Schnapper … you can salt schnapper at any time; you can use them – they keep longer – not spoil much. [Q] Pickled? [A] No, another kind of fish make pickle. Only make tailor and like the mullet. [Q] For the use of your countrymen I suppose? [A] My countrymen – Yes … only smoked fish Europeans use.

Considering that large quantities of schnapper must have been caught and cured, it is surprising to discover that Chinese people considered schnapper a low-grade eating fish. When asked if he ever sent cured schnapper to China, Chin Ateak responded, “No, in the China market cheaper – only cheap fish”. Schnapper appears to have been sought after by Chinese curers in Australia because – as Chin Ateak says “It is very easy salting the schnapper … they keep longer – not spoil much” (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1224–26).

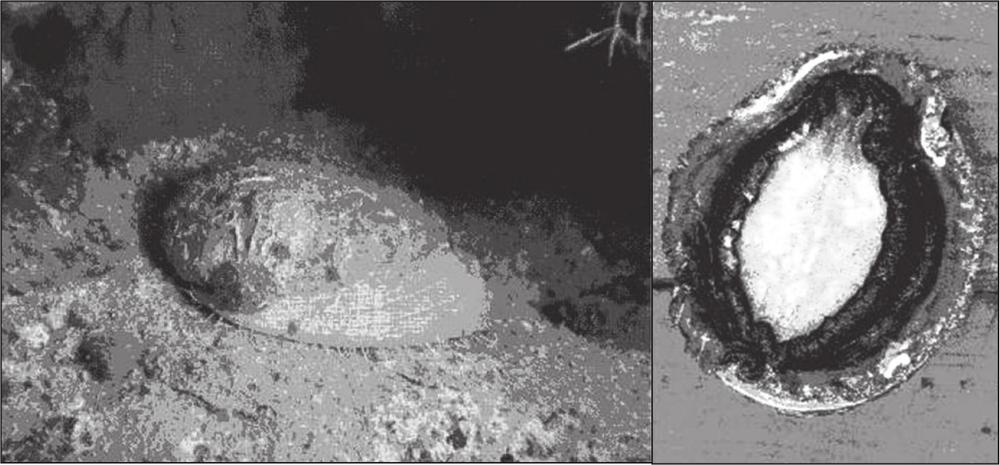

The Chinese curers also processed a wide variety of other fish and shellfish. Chin Ateak suggests that Chinese people considered squid (Sepioteuthis australis) (figure 4.14) to be the most valuable and best eating fish along with the “mutton-fish, with a big shell” – the Australian abalone (Haliotis naevosa) (figure 4.15). Speaking of the squid, Chin Ateak says, “At Melbourne plenty of that; schooner send plenty up … that we call the best fish – the squid”. When asked about the abalone, “What do you make of the inside?” Chin Ateak responds, “All the same – make soup … the very best”.

Figure 4.14 Common Australian squid (Sepioteuthis australis) Image from Vaughan 1987: 196.62

Figure 4.15 Australian abalone (Haliotis naevosa). Images from Vaughan 1987: 188.

The Chinese curers also targeted prawns and lobsters, as Chin Ateak indicates:

[Q] Do you know what are called prawns here? [A] Yes. [Q] Do you ever purchase them for the trade? [A] Plenty, from the Hunter River and Newcastle and some are got up from Lake Macquarie … we get them and mix them up with salt and make pickle, like a paste – like anchovy. [Q] And do you make use of the cray-fish – the lobster? [A] The lobster, yes … we dry them … send them to the country. [Q] Do you get a good price for them? [A] Just like the fish.

Chin Ateak describes how Chinese people in Australia ate the cured fish:

[A] Only cook it with rice – on top of rice. [Q] Do they boil it? [A] Not boil it, only steam it, rice at the bottom and fish at the top; the steam comes up and cooks the fish and makes the rice to be done and the fish to be done too.

Chin Ateak’s participation in the 1880 royal commission provides valuable details of Chinese fish-curing operations in colonial Australia. The accounts of European fisherman who fished for the Chinese curers and eyewitness descriptions from newspaper reporters are also good sources of information. For example, in the 1892 select committee on the fishing industry of Victoria, William Fitz answers questions on the Chinese fish curers at Port Albert. When asked, “How do they cure their fish?” he answers: “Salt them and dry them in the sun” (Votes and Proceedings of the Victorian Legislative Council 1892: 111). A writer reminiscing about his youth in Port Albert gives a more detailed description:

We boys delighted to walk to Long Point, to see the Chinamen fishing and curing fish. They had long tables on trestles, on which the fish, gutted and split open, were laid to dry in the sun. The fish were closely packed in bags and sent by steamer to Melbourne. (Gippsland Standard 1944, July 7)

Oliver (1871: 785) also notes the use of bags for packing cured fish: “Fish have hitherto been salted chiefly by Chinamen for exportation to Victoria … they are shipped in a dry state in bags”. The Bendigo Advertiser (1857, January 5) reports that at Schnapper Point in Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Chinese fish curers “split the fish in the usual fashion and after being cured, are spread out to dry upon the long kangaroo grass”.

Two separate curing procedures were described at the fish-curing establishment in South Australia, for

herrings, garfish, mullet, whiting, ruffs, flounder, salmon, cuttlefish, squid, silverfish … [T]hey were indiscriminately cast into casks of brine and when a couple of days were past, they were removed and spread in the sun to partially dry … After this they were stowed in casks fit for exportation. (The Argus 1864, May 28)

Schnapper appears to have been processed differently:

[The] internal arrangement of the fish is partially removed, leaving the liver and roe attached, being cleverly split from the back. They are then thrown into a brine-cask and left for a few days, after which they are taken to the beach, cleanly scrubbed with small brooms and dried on the rushes. (The Argus 1864, May 28)

A similar method is described by fisherman George Newton, when asked by the New South Wales royal commission (1880: 1200), “Can you give us any idea of their mode of curing – what they did with the fish?”, he answers, 63

They split them and salt them and shove them into a cask … at other times they would cut a little of the belly, take the inside out – just what they could reach – put a lot of salt in and stuff the fish into a cask.

The Australian Town and Country Journal (1870, July 9) gives a very good description of Chinese fish-curing methods, “The smaller varieties – such as perch, tailor, garnet, soles, herrings, &c, – are mostly converted into a kind of semi-liquid preserve”. All other types of fish are:

taken in baskets to the splitting-table: and after being there opened, headed and the back bone removed, they are passed on to another part of the establishment for salting … and should only remain a certain number of hours or days – according to the kind of fish being salted – in pickle. After salting, the fish is placed in a large trough, filled with water, cleansing away superfluous salt, until at length it is laid on slabs or sheets of bark, to be dried by the sun. The labour spent on this part of the process is very considerable, each fish having to be shifted and turned an immense number of times before it is finally ready for packing for exportation.

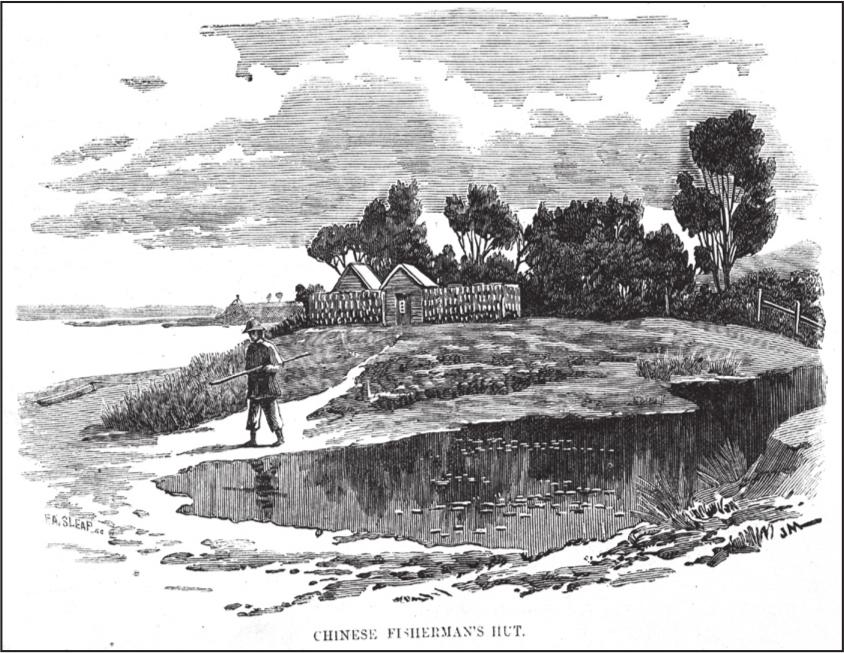

The evidence above provides an understanding of the types of fish Chinese fish curers preferred, how they procured them and cured them and how they were eaten. A good indication has also been obtained as to which fish Chinese people considered the best for eating. From the curing methods described, it appears the Chinese fish curers in Australia produced two types of product: pickle-cured fish, which was packed into casks; and salted fish that was sun-dried and packed into bags. While slight variations in fish-curing methods were noted at different fish-curing establishments (figure 4.16), the end product was always either pickled or salted sundried fish.

Figure 4.16 An 1886 wood engraving by D Syme, titled Chinese fisherman’s hut: holiday tour round Port Phillip shows fish hanging to dry in the open air. This is a variation to the horizontal drying racks represented elsewhere in Victoria such as at Chinaman’s Point and Metung. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Economics

European fishing operations in colonial Australia generally involved two or three men making a basic living. In the later colonial era, with the advent of sea trawling, bigger boats and refrigerated, faster transport of fish to market, some European fishermen generated considerable wealth. An examination of how much fish the European fishermen and Chinese fish curers were processing annually and how they fared economically, produces some very surprising results.

Firth (1946: 220) indicates that for Chinese fish curers in Malaya, “the largest element in the ‘profit’ of the fish-curer is normally a return for the labour expended”. It is difficult to estimate the costs that were involved in maintaining a colonial-period Chinese fish-curing establishment, largely because the cost of the various inputs – from labour usage to quantities of salt required – cannot accurately be ascertained. It is possible, however, to establish the amount and price of fresh fish sold annually through European markets and to compare these with the quantities and price of fish that Chinese people were curing.

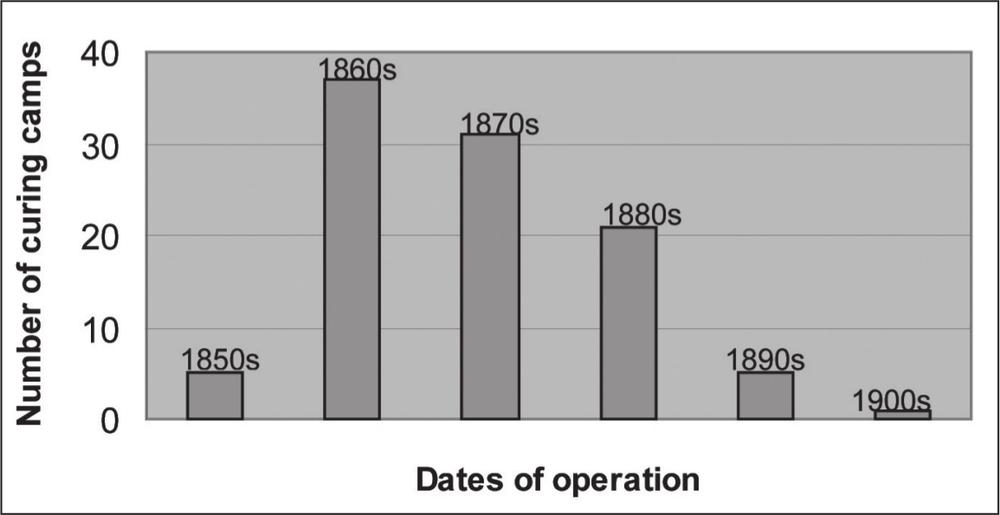

Historical data from the period of peak Chinese activity in colonial Australia – the late 1850s to early 1870s (Cronin 1982: 140) – is instructive, as this is when Chinese cured fish would have been in highest demand.

Statistics from Sydney’s fish market in 1870 show that just one and a half tons of fresh fish was sold per week, totalling 78 tons for that year for a population of 200 000 (Oliver 1871: 782–84). From contemporary 64market records and his own field research, Oliver estimates the annual value of this fish including all inputs from ocean to marketplace was about ₤6000 wholesale and ₤10 000 retail. This averaged ₤77 per ton, a huge mark up from the ₤2 to ₤7 per ton – after costs – that fishermen received for their catch (Gippsland Times 1879, May 21). As a comparison with later years, the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1891–92, Papers Laid Upon the Table: 279) recorded that in 1890 the total value of fish sold at Sydney’s fish markets was ₤38 694 – no tonnage is recorded – which suggests that consumption of fresh fish in colonial Australia increased over time.

Statistical data for fish sales in colonial Victoria is scarce. From the information available, Victoria – with a population of 500 000 in 1862 – appears to have had a healthier appetite for fish than New South Wales, most likely due to Victoria’s larger population. In 1866, the minutes from the Fish Market Committee show that on average, 11 tons of fish was sold through Melbourne’s fish market each week; no sale prices are listed (Minutes of the Victorian Market Committee. Victorian Public Records Office (PROV), Series 4030, Unit 2 & 3: 102–58). Averaged annually, 132 tons of fish passed through the Melbourne fish market in 1866. Assuming that fish sale prices, transport and agent fees were similar between the two colonies, approximately ₤10 153 of wholesale and ₤16 923 of retail fresh fish was sold annually in Melbourne during the mid 1860s. As a comparison with later years, a royal commission into Victorian fisheries (1919) records that in 1918, ₤129 529 of fish was sold through the Victorian fish market (Votes and Proceedings of the Victorian Legislative Council 1919: 7).

Ten separate historical documents have been located that indicate Chinese fish curers would purchase from European fishermen as much fish as they could get (see for example Votes and Proceedings of the South Australian Legislative Council 1861: 857; Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879-80, vol. 3; Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 1: 1181, 1200; Geelong Advertiser 1857, January 12; The Argus 1864, May 28). As there do not appear to be any official records of the quantity of fish that Chinese people caught themselves (they did not sell through European markets) or purchased from European fishermen, it is not possible to determine exactly how much fish Chinese people cured. However, Chinese cured fish was often transported between the Australian colonies by sea and records of ship cargoes, listed in the shipping intelligence columns of colonial newspapers, provide an indication of the quantities of fish cured by the Chinese (a topic discussed in more detail below).

The amount that Chinese curers paid European fishermen for fresh fish can be broadly ascertained through historical literature. For example, fisherman George Newton indicates that during the late 1850s to early 1860s, Chinese curers in New South Wales gave ₤14 6s per ton for schnapper, but by the late 1870 they were only giving ₤5 3s (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1200). Fisherman Michael Solomon commented that in the early days – the 1860s – the New South Wales Chinese curers paid ₤14 a ton for net fish (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879– 80, vol. 3: 1186). By the 1880s, however, the Chinese fish-curing industry was in decline and prices paid to European fishermen had fallen substantially. An article in the Gippsland Standard (1884, March) reports “Large hauls of fish at Port Albert. Five tons sold to Chinamen on eastern beach at ₤6 per ton”. The Gippsland Standard (1944, July 7) – reminiscing back to approximately the 1890s – suggests the Chinese fish curers at Port Albert were paying ₤4 per ton for net fish at this time.

Some analysis of terminology and weights is useful. It has been shown that Chinese salted sun-dried fish was packed in hessian bags, sometimes called packages or written ‘pkgs’ and pickled fish was stored in timber casks (see for example Oliver 1871: 785; The Argus 1864, May 28; (Votes and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Legislative Council 1886, vol. 13: 36). Only one document has been located that indicates the weight of a bag of cured fish. This comes from the Bendigo Advertiser (1861, November 14), which reports an incident where two Chinese men stole a bag of cured fish from a Chinese store in Bendigo: “While Ah Chin came in and purchased 6d worth of opium the other [Ah Way] picked up a bag of fish 150 lb weight, which was by the side of the counter”. It can only be assumed that bags of fish – like other bagged products such as salted beef or pork, tea, coffee, tobacco, fruit, flour and sugar (Pears Cyclopaedia 1905: 353; Barker 1882: 138–41) – were sold as a standard weight. There are 2240 pounds in a ton; so 15 bags of cured fish make one ton.

It must also be noted that salt sun-drying fish removes moisture content, leaving the fish from 30 to 60% lighter in weight than when fresh – depending on fish type (Cutting 1955: 183; Davis 1973: 10–11; Ashbrook 1955: 246). Calculations for this project average the weight of cured fish to 45% lighter than fresh fish.

The Hobart Town Advertiser (1860, November 22), recorded that on 15 November 1860, the ship Wonga Wonga transported the following quantities of Chinese cured fish from Sydney to Melbourne: “6 packages fish J. Chan; 42 packages fish, Lee See; 10 packages fish, Ah Cheong; 30 packages fish, Sam Ting; 44 packages fish, Chin Ateak”. If one package of fish weighed 150 lb, in this shipment, five Chinese people forwarded 9 tons of cured fish from Sydney to Melbourne.

65The Wonga Wonga features in the shipping intelligence columns as the main ship used for transporting Chinese cured fish cargoes from Sydney to Melbourne. The Wonga Wonga was a 681-ton coastal steamer. Sister ship to the City of Sydney, which also carried considerable quantities of Chinese cured fish, both vessels were owned by the Steam Navigation Company, a private organisation that comprised a number of directors and shareholders (Nicholson 1998: 474; www.pbenyon.plus.com/Gazette/Shipping_Steam/Wonga_Wonga_Maiden_Trip.html). It is conceivable that Chinese merchants had interests in the Steam Navigation Company, but no evidence of this has been located.

Shipping intelligence columns in colonial newspapers reveal that bulk quantities of Chinese cured fish were regularly transported between Australian colonies. To examine each colonial newspaper (between approximately 1854 to 1900) for ship destination and cargo types is beyond the scope of this project. However, even a brief review of two months (May and June) in 1861, a peak period of Chinese activity in colonial Australia, of the Shipping Gazette in The Sydney Mail (this newspaper had a reasonably regular shipping intelligence column) shows that Chin Ateak transported from Sydney to Melbourne 314 packages of dried fish and 41 casks of pickled fish, Foo Chong 28 packages of dried fish, Sal See 50 packages of dried fish, Sing Waa 41 packages of dried fish, Jon Fun 16 packages of dried fish, Hong Chow Ling 37 packages of dried fish, and Waa Lee 67 packages of dried fish and 36 casks of pickled fish. In total, for this two month period, 553 packages – 37 tons of dried fish or 53.5 tons of fresh fish equivalent – and 77 casks of Chinese cured fish went from Sydney to Melbourne. Taking into account only the packages of dried fish – as the weight of cured fish in casks is unknown – this 37 tons of cured fish is 1.5 times the amount of fresh fish going through the European fish markets in Sydney and Melbourne combined over any two months in the same period. Add these 37 tons – which is only the amount going from Sydney to Melbourne over eight weeks – to the unknown, but undoubtedly large quantities of fish that was cured (i.e. which did not get shipped between colonies and therefore cannot be traced) and consumed by Chinese people in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and at overseas locations and the significance of the Chinese contribution to Australia’s colonial fishing industry becomes apparent.

By 1868, shipping intelligence columns show the volume of Chinese cured fish transported from Sydney to Melbourne had slowed to 48 packages during October and 68 packages in November, totalling 7.5 tons – 11 tons fresh equivalent. This amount – representing just a proportion of the total amount of fish cured by the Chinese in New South Wales – was similar to the quantity of fresh fish consumed by the whole population of Sydney over the same period.

Hop Lung and Ah Tie told the Australian Town and Country Journal (1870, July 9) that, when demand for cured fish was high during the 1860s, they would each send from Lake Macquarie to Sydney and Melbourne up to 70 tons of cured fish annually. This information is corroborated by the Hon. H Ayers, MP, who commented during the parliamentary debate on Chinese immigration (1861) that the Chinese living 120 miles north of Sydney (the Lake Macquarie region) “now exported [presumedly to Sydney and Melbourne] about 20 tons of fish per month” (Votes and Proceedings of the South Australian Legislative Council 1861: 57). This suggests that some 240 tons of cured fish – 348 tons fresh equivalent – was processed annually in this region alone.

Statistical returns for 1866 listed in Tasmania’s parliamentary papers, show 266 packages of crayfish were exported to Victoria and a further 49 packages went to New South Wales. Uncured crayfish flesh would perish on such a voyage and as there are no records of European people curing crayfish, they almost certainly represent a product from the Tasmanian Chinese fish-curing establishments. Assuming fish and crayfish lost similar weight percentages during the curing process, 315 bags equates to 21 tons of cured crayfish, revealing that Tasmania was also supplying significant quantities of Chinese cured product to Victoria and New South Wales.

A report in the Hobart Town Advertiser on 30 November 1860 states that Chinese people at Fingal in Tasmania cure crayfish and “send them into the Melbourne market where they realize about one hundred pounds per ton”. This price would have been achieved at the peak of the Chinese demand for cured fish during the 1860s. As with all commodities, prices for Chinese cured fish varied. When the royal commission of 1880 asked fisherman Thomas Curtis “Have you any idea of what price per ton they got for the dried and salted fish?” he replied, “About ₤70 a ton for them at one time” (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1186). Oliver (1871: 785) states that Chinese cured fish “in the piping times of gold-digging, frequently realized over ₤50 per ton”. European smoked fish sold for approximately ₤16 per ton during the same period, but on the goldfields prices could reach ₤40 per ton (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1140).

Europeans ventured into fish curing – usually smoked fish – on a small scale. From approximately 1855 to 1863 James Meek smoked fish commercially at Curdie’s Inlet near Warrnambool in Victoria (Duruz 1973: 43; Warrnambool Examiner 1863, November 8; 1864, February 9). For a short period during the 1870s Frank Koeing 66ran a fish-smoking establishment at Rosherville (Metung) in the Gippsland Lakes (Gippsland Mercury 1879, May 20). Due predominantly to the large labour input required, smoke curing fish was generally considered an unprofitable enterprise (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1140, 1204, 1267). John Massey’s comments during the royal commission (1880: 1211) suggest the general opinion of European fishermen on curing fish: “[Q] When you get a large haul, do you cure the balance of the fish? [A] We let them go; it would never pay to cure them”. Surprisingly, there appears to have been no effort to experiment with canned fish, despite a considerable market for canned fish products. The Statistical Register for New South Wales shows that from 1869 to 1897, ₤512 000 worth of canned sardines, ling and salmon was imported to Australia – approximately six times the value of fresh fish sold in New South Wales over the same period (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 1: 672).

In the 1880 royal commission, Chinese merchant Chin Ateak gives a broad indication of the quantities of cured fish he dealt with annually and the prices he received. When asked if he “found at one time there was a good trade to be done”. He answered:

Yes, a very good trade; there was a lot of people there and we sold two and three hundred tons a year … In New South Wales some hundred tons and two hundred tons at Melbourne. (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1879–80, vol. 3: 1224)

Chin Ateak’s annual sales amount to almost ten times the tonnage of fish sold through Sydney and Victoria’s European markets combined. When asked if he “sometimes got very high prices in this country”. He replied: “Yes … One time up to ₤100 a ton”. The mathematics is plain. In one year Chin Ateak could have made up to ₤300 000 from cured fish sales, much more than the fresh fish sales through Sydney and Victorian European markets and certainly a great deal more money that any European fishermen were making. Moreover, as seen through the shipping intelligence columns quoted above, there were other Chinese people dealing in cured fish, some of them shipping similar quantities to Chin Ateak.

The historical documents confirm that the Chinese fish curers in Australia were dealing in far greater quantities of fish than has ever before been acknowledged. As the various royal commission interviews with fishermen show, at one period – broadly from the late 1850s to early 1860s – a considerable number of fishermen in coastal Victoria and New South Wales fished for the Chinese curers. The Chinese fish curers were “conducting this branch of industry on a large scale” (Bendigo Advertiser 1857, January 5) and had “the whole of this trade in their own hands” (Votes and Proceedings of the South Australian Legislative Council 1861: 858). The Chinese contribution to Australia’s colonial fishing industry was very significant.

As the Australian Chinese population dwindled, so did the price of Chinese cured fish. By 1870, the fish curers on Lake Macquarie reported they were receiving approximately ₤20 a ton for their product (Town and Country Journal 1870), compared to between ₤70 and ₤100 ten years previously. Oliver (1871: 785) states, “at present, the export trade is very limited and the price paid … is not more than ₤16 to ₤18 per ton”. In the royal commission of 1880, Chin Ateak also notes the downturn in sale prices, noting that in Sydney and Melbourne, cured schnapper would fetch ₤28 per ton and cured mullet would sell for ₤12 a ton. Chin Ateak – in 1880 – would pay, if someone would supply him, ₤28 per ton for shark fins, ₤50 per ton for squid and ₤84 per ton for abalone “for as much as you bring to me”.

Reverend Young estimated in 1868 that Chinese market gardeners earned approximately ₤2 per week and a Chinese miner working for a Chinese company earned approximately ₤1 per week (cited in McLaren 1985: 39–40). During this period, European fisherman earned an average profit of ₤2 to ₤5 per week (Gippsland Times 1879, May 21). The hundreds of thousands of pounds sterling generated annually through Chinese cured fish was many times more than European profits from fish during the colonial period. The enormous market for Chinese cured fish is reflected in the observation in the Bendigo Advertiser (1857, January 13) that “The Chinese population employed on the diggings must be very fond of fish if they eat all that their brethren … send to them”.

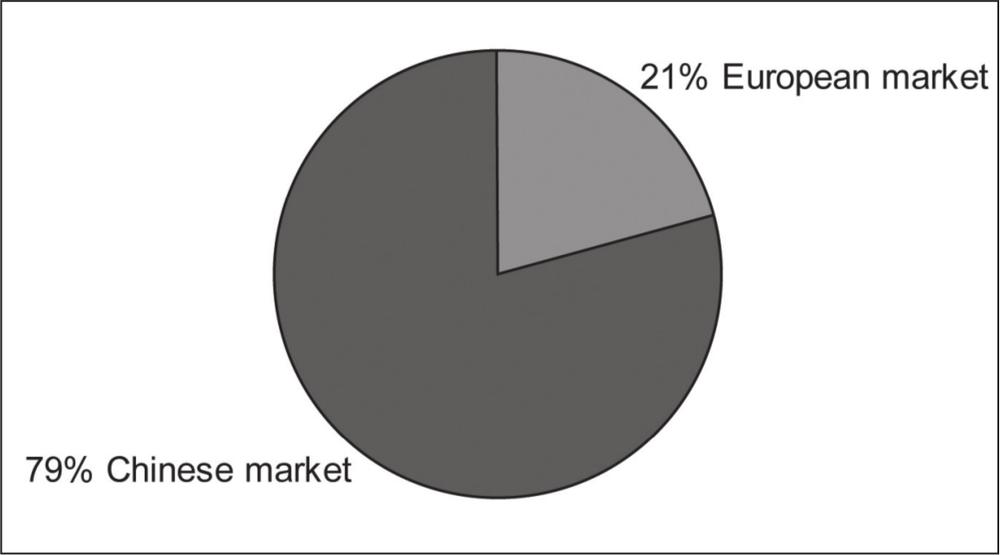

Market locations

The most obvious market for Chinese cured fish in Australia was the Chinese gold-diggers and associated infrastructure workers. Future discoveries of colonial-period Chinese documentation may provide an indication of exactly how much cured fish went to the goldfields. The next most likely market for Australian Chinese cured fish is China. Indeed, much of the Australian historical literature suggests a portion of Chinese cured fish was going to markets in China. Opportunistic markets would also have presented themselves, as shown in the section on the Northern Territory where cured fish was provided to government employees. The following section examines the market outlets for Chinese cured fish.

67Many references have already been cited to show that Chinese fish curers in Australia sent a great deal of fish to Melbourne, much of which was destined for Victoria’s goldfields. The Gippslander (1865, November 10) reported:

The Chinese purchase the fish from the fishermen, cure them and forward them to Melbourne to their depot, whence the whole of the up country markets are supplied.

The Bendigo Advertiser (1857, January 5) reports in similar terms:

We learn that this commodity [Chinese cured fish] is sent into the interior in large quantities, where it finds a ready sale among the Chinese population.

At Semaphore Jetty in South Australia, the Chinese curers forwarded their product to “the neighbouring colony, to be used as food by the Mongols on the various diggings” (The Argus 1864, May 28). Enormous amounts of cured fish were consumed in this fashion, first on the Victorian goldfields, then in New South Wales, Tasmania, the Northern Territory and elsewhere else in Australia where Chinese people worked and lived.

Another likely market outlet was the shipping industry, supplying rations for Chinese sailors and passengers travelling between China and Australia. When Chin Ateak was interviewed for the Chinese Immigration Bill 1858 he stated that ships coming from China usually carried between 400 and 500 Chinese men, but some carried as many as 1300 Chinese men (Votes and Proceedings of the New South Wales Legislative Council 1858, vol. 3: 18). The voyage between China and Australia took anywhere between 60 to 85 days, with crew and passengers receiving two meals a day, predominantly rice, salted fish and some salted vegetables (Wang 1978: 307). While arrangements for procuring Chinese ship provisions are not known, with large quantities of cured fish available in Australia, it is conceiveable that ship rations of salted fish were at least in part obtained from Chinese fish curers in Australia.

Firth (1946: 12) notes that Singapore was a heavy consumer of fish and a major distributing centre for fish. Sydney and Melbourne shipping arrival and departure notices support Firth’s statement. In 1855, the Glendaragh, the General Blanco and the Yarra Yarra – regular vessels on the Australia– China trade route – each took cargoes of fish from Melbourne to Singapore and Hong Kong (Syme 1987: 321; 333; 343). Further evidence of the export of Chinese cured fish from Australia to Asian destinations is in Chin Ateak’s testimony in the royal commission (1880: 1224). When asked “Did you ever send any [fish] to China?” he answered, “Yes, we sent some Mullet”. “[Q] Do you Chinamen salt them? [A] Make pickle fish”.

The Shipping Gazette in The Sydney Mail (1861, March 23) shows Chin Ateak exported on the Antagonist 12 casks of pickled fish to Hong Kong. On the same ship, he also exported 472 ½ ounces of gold. The Shipping Gazette (1861, 22 June) shows that Chin Ateak exported to Hong Kong – on the Cyclone – 603 tons of coal, 22 cases of copper, 1968.5 ounces of gold [worth approximately ₤7 874] and 47 bags of fish. The bagged fish indicates that Chinese fish curers did not only export pickled fish to China as Chin Ateak suggested in the royal commission of 1880.

The Shipping Gazettes confirm that, even though some cured fish was exported to China, Chinese people on the Australian goldfields, particularly in Victoria, consumed by far the majority of Chinese cured fish in Australia. Chinese fish curers would obtain and cure fish wherever a fresh source was available. Once cured, the product would be transported to wherever a suitable market outlet existed.