7

Preventing chronic disease to close the gap in life expectancy for Indigenous Australians

Prevention of disease is a major aim of the Australian health system. Chronic diseases are responsible for approximately 80% of the burden of disease and injury in Australia, account for around 70% of total health expenditure, form part of 50% of GP consultations, and are associated with more than 500 000 person/years of lost full-time employment each year [1]. A small number of modifiable risk factors are responsible for the major share of the burden of preventable chronic disease. This chapter focuses on chronic kidney disease as an example of a preventable chronic disease that impacts heavily on the indigenous community, causing major morbidity and mortality. Key modifiable risk factors for chronic kidney disease include tobacco smoking, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, obesity and high blood pressure. Amongst Indigenous Australians, poor access to necessary preventative care, combined with the broader social determinants of health, acting across the life-course, contribute to the excess burden of chronic disease, including diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Improvements in maternal and early childhood health and development, educational attainment outcomes and access to safe and secure housing are critical ‘building blocks’ in national efforts to reduce the burden of chronic disease and to close the gap between the health status of Indigenous and non-indigenous Australians.

Burden of disease

The most recent estimates of the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous men and women are 12 and ten years respectively [2]. However, the true life expectancy of Indigenous Australians remains a matter of dispute. Research has shown a lower life expectancy in states or territories with more complete reporting of Indigenous deaths [3]. Amongst people aged 35 to 74 years, 80% of the mortality gap is attributable to chronic diseases. The inextricably related chronic diseases of blood vessels and metabolism – heart disease, diabetes, stroke and kidney disease – constitute half of this gap [2].

121There are almost 20 000 Australians with severe or end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), who require ongoing dialysis or have received a kidney transplant. The incidence rate of ESKD among Indigenous Australians contrasts dramatically with that for non-Indigenous Australians. There is a steep gradient in the burden of kidney disease from urban areas, where rates are three to five times the national average, to rural areas where rates are ten to 15 times higher, to remote areas where rates are up to 30 times the national average [4, 5]. Between 2007 and 2008, there were almost 115 000 hospitalisations for regular dialysis for Indigenous Australians. This constitutes more than 40% of all hospital admissions for Indigenous Australians and dialysis hospitalisations occur at a rate 11 times that of non-Indigenous Australians [6]. While the burden of earlier stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) amongst Indigenous Australians is less well documented, it is known to occur commonly. People with earlier stages of CKD are at high risk of death due to heart disease and at high risk of progression to ESKD.

Based on data from the AusDiab study, which surveyed the health of a large and representative sample of the adult population, about one in nine Australians aged 25 years and over have early CKD [7]. However, comprehensive population-based data for the national burden of CKD among Indigenous Australians are not available. Between 2004 and 2006 in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, CKD was recorded as the underlying cause of death in nearly 4% of all Indigenous deaths, a rate seven to 11 times higher than for non-Indigenous males and females respectively [8]. CKD was an associated cause in a further 12% of deaths [8]. Surveys in individual remote Aboriginal communities have documented high rates of early stages of CKD and its cardinal markers – reduced kidney function measured with a simple blood test and protein leakage into the urine from damaged kidneys. An audit of the screening and management of chronic disease in Aboriginal primary care, undertaken through the Kanyini Vascular Collaboration, has confirmed that more than 40% of regular adult attendees at Aboriginal primary care services who receive recommended screening tests have reduced kidney function or proteinuria [9]. This health service, rather than population-based data, underscores the burden of CKD which needs to be addressed.

Risk factors

Risk factors for CKD can be categorised as fixed and modifiable. Fixed-risk factors include a family history, genetic predisposition and increasing age [8]. Modifiable risk factors include low birthweight, socioeconomic disadvantage, diabetes, high-blood pressure, overweight and obesity, tobacco smoking, physical inactivity and poor nutrition [8, 10, 11]. Amongst Indigenous Australians, factors that arise early in the lifecourse, including poor maternal health and low birthweight and the burden of childhood infection and chronic inflammation, have been associated with increased risk of developing CKD [12, 13]. The associations between markers of socioeconomic disadvantage, including leaving school early, unemployment, low household income and house crowding, and ESKD rates, are particularly strong for Indigenous Australians [14].122

Intervention across the life-course

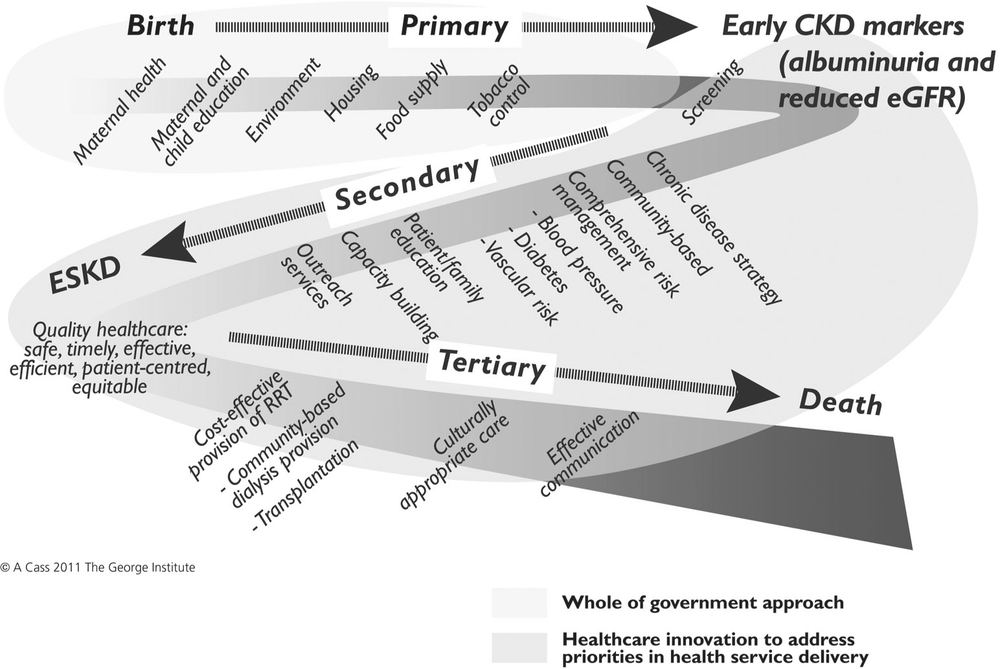

Reducing the burden of CKD will require targeted interventions across the lifecourse, from before birth through childhood to adulthood (Figure 1). Whole of government interventions are required to address social disadvantage, and priority areas around housing, food supply and tobacco control can be directly related to CKD. Within the health sector, targeted screening, early intervention and evidence-based management to prevent the progression of kidney disease are required [15]. Although this chapter will focus on prevention, equitable access to necessary kidney disease treatment services must also be provided. Key service delivery issues that must be addressed by health providers and systems in order to better respond to the health, social and cultural needs of Indigenous Australians with kidney disease include:

- Poor access to home- and community-based dialysis forcing the majority of patients from remote areas to relocate permanently to urban areas for treatment

- Low kidney transplant rates

- Making health services easier for Indigenous patients to navigate: key factors here include proximity to health services, availability of transport, minimal out-of-pocket costs for attendance and treatments, after-hours access, outreach services and mobile clinics, welcoming physical spaces and Indigenous staff as a critical point of contact

- Inadequate provision of trained interpreters in Aboriginal languages

- Pervasive miscommunication between Indigenous kidney patients and their healthcare providers (Figure 1) [16, 17, 18, 19].

Primary prevention of kidney disease

Primary prevention initiatives are required from the antenatal period with the aim of preventing the development of CKD. High-quality evidence from controlled trials conducted within the Indigenous population, on the effectiveness of interventions to prevent the development of CKD is not currently available. Nevertheless, evidence indicates that the following initiatives would have a positive health impact generally and would affect intermediate outcomes known to be associated with the development of CKD:

- Increased access to antenatal services to improve fetal and maternal health, and reduce the rates of low birthweight

- Screening and intensive management of diabetes in pregnancy [20] and encouragement of breastfeeding [21] to help prevent the development of obesity and early onset of type 2 diabetes

- Prevention of obesity in early childhood, particularly due to ‘catch up growth’ in those with low birthweight, as these people are at greatest risk of developing diabetes [22] and CKD [23]

- Early childhood development initiatives to improve educational achievement and lifeskills123

- Training community members to improve housing infrastructure and to maintain improvements [24]

- Installing swimming pools in remote communities to reduce the prevalence of skin, middle ear and respiratory tract infections [25]

- Community-based scabies control programs

- Food supply initiatives to improve access to affordable healthy food [26]

- Culturally appropriate healthy nutrition, physical activity and quit smoking programs and legislative initiatives to regulate tobacco advertising.

Figure 1. A life-course approach to CKD prevention and management (Refer to the text for specific approaches as they relate to Indigenous Australians).

Primary care-based screening and early intervention to prevent disease progression

Screening tests for CKD in primary care should include:

- A urine test for protein – specifically indicated is a first morning urine specimen tested for albumin. Albumin is an abundant protein in the blood. If detected in the urine, it indicates kidney damage. (If a first morning urine specimine cannot be obtained, a urine specimen obtained when a patient is attending primary care is acceptable.)

- A blood test to measure serum creatinine – a breakdown product of muscle, usually produced in the body at a constant rate and filtered out of the body through the 124kidneys. Where kidney function is reduced, the filtration rate falls and blood levels rise. The blood test result is used to estimate kidney function – commonly termed as estimated glomerular filtration rate or eGFR.

The Kanyini Vascular Collaboration (KVC), established in 2006, brings together Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, health providers and policy-makers in a research program aiming to improve the health outcomes of Indigenous Australians with heart disease, diabetes and kidney disease (www.kvc.org.au). The KVC Audit Study showed that approximately 40% of those people attending Aboriginal primary-care services, who are indicated for CKD screening, have the results of these tests entered into their medical record [9]. Primary care-based screening to facilitate early detection and evidence-based management of CKD has been shown to be cost-effective in the general population [27]. Evidence supports targeted screening of people at high risk of CKD – including Indigenous Australians aged 35 years and over; people with diabetes, high blood pressure or heart disease; smokers; people with a family history of CKD; and people who are overweight or obese. A comprehensive CKD screening program, if implemented as part of a coordinated chronic disease strategy, should have benefits both in terms of prevention of heart attacks, stroke and cardiac deaths as well as prevention of ESKD [27].

Modelled analyses utilising best Australian evidence regarding the population burden of diabetes and high-blood pressure, current practice patterns and randomised controlled trial-based evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions, have demonstrated that primary care–based screening for CKD and its major risk factors, followed by evidence-based management of high blood pressure, diabetes and proteinuria, is likely to be highly cost-effective [27]. The KVC Audit Study has revealed evidence–practice gaps in the management of blood pressure and cholesterol in Aboriginal primary care, similar to gaps in mainstream primary care, which, if closed, would improve heart and kidney health outcomes for Indigenous Australians [9].

Substantial evidence underlines that lowering blood pressure is effective in reducing heart attacks, stroke and cardiac death [28] and favours the use of treatment regimens which include a particular class of drugs, ACE inhibitors, in slowing the progression of CKD [29]. Such evidence is most compelling for patients with kidney disease due to diabetes [30]. Diabetes is the leading cause of ESKD in many countries and is the primary cause or an associated condition for the vast majority of Indigenous Australians commencing dialysis for ESKD. As described in other sections of this book that address diabetes organ complications, large trials in people with diabetes have provided strong evidence that intensive control of blood glucose delays the onset or progression of diabetic kidney disease, particularly in its early stages [31]. Despite a lack of controlled trials indicating benefit within the Australian Indigenous population, chronic disease management programs in remote Aboriginal communities, which compared program results with disease rates for the population prior to the program, indicate the heart and kidney benefits from intensive management regimens [32].125

The need for monitoring

Recent research has confirmed the lack of reliable, population-representative data for Indigenous Australians regarding the burden of CKD and related chronic conditions, risk factors for the development and progression of chronic disease, and utilisation of relevant preventative and treatment services. As concluded in the AIHW report on prevention of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and CKD [33]:

There is clearly a need for ongoing monitoring in the area of prevention. However, better data are needed, in particular those based on measurement rather than self-reported data, as well as systematic data on population-level initiatives.

The Australian Health Survey (AHS), which commenced in 2011 and aims to involve around 50 000 Australians, will include an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wave in 2012 [34]. This is a key step towards filling this data gap. Amongst its objectives, the AHS aims to estimate the prevalence of certain chronic conditions and selected biomedical and behavioural risk factors. Informed and consenting participants in the AHS, from a representative household-based sample of the population, will answer questions about their health; have their height, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure measured; and will be asked for separate consent to give blood and urine samples to measure markers of chronic disease including heart disease, diabetes and CKD. Such monitoring will form one necessary part of a coordinated prevention strategy aiming to reduce the burden of complex chronic disease amongst Indigenous Australians.

Conclusion

The National Indigenous Health Equality Summit, held in Canberra in March 2008, proposed a set of key targets to achieve the COAG commitment of closing the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectancy gap within a generation. With the major contribution of premature death due to chronic diseases, we must comprehensively address chronic disease prevention and management using appropriate, sustainable and cost-effective strategies. The summit promulgated a prevention target relevant to CKD: ‘Stabilize all-cause incidence of ESKD within five to ten years’ [35]. Although ESKD directly affects fewer than 1500 Indigenous Australians [36], the impact of this chronic disease on families and communities is profound. Key findings of the recent Department of Health and Ageing Central Australia Renal Study [17] regarding the social and cultural impacts of ESKD include:

- For Aboriginal patients [in remote regions], uptake of treatment for ESKD has generally necessitated permanently moving away from kin and community. Consequences have included loss of social and cultural connectedness, loss of autonomy and control, and loss of status and authority.

- Key family and cultural leaders having to move away has profoundly affected communities.

- Patients moving to town for treatment are generally accompanied by immediate family carers and dependents. Research has estimated that as many as five people may follow 126a person going for dialysis. This has implications for accommodation, social support services, employment and education.

These findings are relevant to the experiences of Indigenous Australians across remote Australia [37]. The devastating impact of ESKD was confirmed by many people interviewed for the Central Australia Renal Study. Their experiece underscores the imperative to prevent and optimise the management of CKD [17]:

When my husband went onto dialysis, he got really angry and depressed … It was really hard. We had to move into town. There was no support to help us cope. He lost everything … he felt useless. (Wife of a dialysis patient, October 2010)

I was born and bred on these lands. How on earth could I go all the way to the city, away from my family and country, knowing there was no possibility for them to come down and stay with me, no accommodation, no facilities … There’s no way I could think about being so far away … I’d just be in total despair all the time. (Senior community member, September 2010)

References

1. National Preventative Health Strategy (2010). Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. The report of the National Preventative Health Strategy: the roadmap for action. Canberra: National Preventative Health Strategy.

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2011). Contribution of chronic disease to the gap in adult mortality between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other Australians. Canberrra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2011). Comparing life expectancy of indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: conceptual, methodological and data issues. Canberra: AIHW.

4. Cass A, Cunningham J, Wang Z & Hoy W (2001). Regional variation in the incidence of end-stage renal disease in Indigenous Australians. Medical Journal of Australia, 175(1): 24–27.

5. Preston-Thomas A, Cass A & O’Rourke P (2007). Trends in the incidence of treated end-stage kidney disease among Indigenous Australians and access to treatment. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 31(5): 419–21.

6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2010). Chronic kidney disease hospitalisations in Australia 2000–01 to 2007–08. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

7. White SL, Polkinghorne KR, Atkins RC & Chadban SJ (2010). Comparison of the prevalence and mortality risk of CKD in Australia using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study GFR estimating equations: the AusDiab (Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle) Study. American Journal of Kidney Disease, 55(4): 660–70.

8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009). An overview of chronic kidney disease in Australia 2009. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.127

9. Peiris DP, Patel AA, Cass A, Howard MP, Tchan ML, Brady JP, et al. (2009). Cardiovascular disease risk management for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in primary healthcare settings: findings from the Kanyini Audit. Medical Journal of Australia, 191(6): 304–09.

10. Cass A, Cunningham J, Wang Z & Hoy W (2001). Social disadvantage and variation in the incidence of end-stage renal disease in Australian capital cities. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(4): 322–26.

11. White SL, Perkovic V, Cass A, Chang CL, Poulter NR, Spector T, et al. (2009). Is low birth weight an antecedent of CKD in later life? A systematic review of observational studies. American Journal of Kidney Disease, 54(2): 248–61.

12. Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Singh GR, Douglas-Denton R & Bertram JF (2006). Reduced nephron number and glomerulomegaly in Australian Aborigines: a group at high risk for renal disease and hypertension. Kidney International, 70(1): 104–10.

13. White AV, Hoy WE & McCredie DA (2001). Childhood post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis as a risk factor for chronic renal disease in later life. Medical Journal of Australia, 174(10): 492–96.

14. Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Wang Z & Hoy W (2002). End-stage renal disease in Indigenous Australians: a disease of disadvantage. Ethnicity and Disease, 12(3): 373–78.

15. Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Wang Z & Hoy W (2004). Exploring the pathways leading from disadvantage to end-stage renal disease for Indigenous Australians. Social Science & Medicine, 58(4): 767–85.

16. Cass A, Lowell A, Christie M, Snelling PL, Flack M, Marrnganyin B, et al. (2002). Sharing the true stories: improving communication between Aboriginal patients and healthcare workers. Medical Journal of Australia, 176(10): 466–70.

17. Department of Health and Ageing (2011). Central Australia renal study June 2011. Part 3: Technical Report. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing.

18. Yeates KE, Cass A, Sequist TD, McDonald SP, Jardine MJ, Trpeski L, et al. (2009). Indigenous people in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States are less likely to receive renal transplantation. Kidney International, 76(6): 659–64.

19. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2011). Chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

20. Dabelea D & Pettitt DJ (2001). Intrauterine diabetic environment confers risks for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity in the offspring, in addition to genetic susceptibility. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism, 14(8): 1085–91.

21. Pettitt DJ, Forman MR, Hanson RL, Knowler WC & Bennett PH (1997). Breastfeeding and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Pima Indians. The Lancet, 350(9072): 166–68.

22. Yajnik CS (2002). The lifecycle effects of nutrition and body size on adult adiposity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Obesity Review, 3(3): 217–24.

23. Hoy WE, Rees M, Kile E, Mathews JD & Wang Z (1999). A new dimension to the Barker hypothesis: low birthweight and susceptibility to renal disease. Kidney International, 56(3): 1072–77.128

24. Pholeros P, Rainow S & Torzillo PJ (1994). Housing for health: towards a healthier living environment for Aborigines. Sydney: HealthHabitat.

25. Silva DT, Lehmann D, Tennant MT, Jacoby P, Wright H & Stanley FJ (2008). Effect of swimming pools on antibiotic use and clinic attendance for infections in two Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 188(10): 594–98.

26. Rowley KG, Daniel M, Skinner K, Skinner M, White GA & O’Dea K (2000). Effectiveness of a community-directed ‘healthy lifestyle’ program in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 24(2): 136–44.

27. Howard K, White S, Salkeld G, McDonald S, Craig JC, Chadban S, et al. (2010). Cost-effectiveness of screening and optimal management for diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease: a modeled analysis. Value in Health, 13: 196–208.

28. Turnbull F (2003). Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. The Lancet, 362(9395): 1527–35.

29. Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, Giatras I, Toto R, Remuzzi G, et al. (2001). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Annals of Internal Medicine, 135(2): 73–87.

30. Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, Landa M, Maschio G, de Jong PE, et al. (2003). Progression of chronic kidney disease: the role of blood pressure control, proteinuria, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition: a patient-level meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(4): 244–52.

31. Jun M, Perkovic V & Cass A (2011). Intensive glycemic control and renal outcome. In Lai KN & Tang SCW (Eds). Diabetes and the kidney (pp196–208). Basel: Karger.

32. Hoy W, Baker PR, Kelly AM & Wang Z (2000). Reducing premature death and renal failure in Australian Aboriginals: a community-based cardiovascular and renal protective program. Medical Journal of Australia, 172(10): 473–78.

33. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009). Prevention of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease: targeting risk factors. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

34. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011). Australian Health Survey [Online]. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/australian+health+survey [Accessed: 21 September 2011]

35. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner and the Steering Committee for Indigenous Health Equality (2008). Close the Gap – National Indigenous health equality targets: outcomes from the National Indigenous Health Equalty Summit Canberra, 18–20 March 2008. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

36. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (2011). ANZDATA Registry 2010 report. Adelaide: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

37. Anderson K, Devitt J, Cunningham J, Preece C & Cass A (2008). ‘All they said was my kidneys were dead’: Indigenous Australian patients’ understanding of their chronic kidney disease. Medical Journal of Australia, 189(9): 499–503.