PART TWO

Principal and professor

42

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Empire was brought closer together not only through formal conferences and meetings but also by the continued improvement of sea travel. The Moldavia reached Sydney Heads on Thursday 22 November 1906, after a six-week voyage. While at sea, Alexander had written sixteen letters to his father, William. After arriving, he composed a long correspondence to William detailing his favourable first impressions of his new home.

I think that Australia will prove a pleasant place to live and Sydney in particular. The harbour scenery reminded me of the West Coast of Scotland. The Shore rises steeply, and is fringed with rocky cliffs. The main channel of the harbour runs off into a great number of creeks and the various suburbs of Sydney stand on the tongues between the creeks. I am afraid it is impossible to describe the town as it is so scattered and irregular but I am sending you a large plan which will help you to fix the places I mention.133

Over the next decade, Alexander sent letters to his father on almost a weekly basis. His correspondence to William in Edinburgh sought not only to provide details of his new environment but also to give insights into his prospects and career in Australia.

44New South Wales had many connections to Scotland, beginning in the early years of colonial settlement. Scottish migration – mainly of free settlers – to the colony had begun by the 1820s. In the 1830s, the Presbyterian minister John Dunmore Lang founded the Australian College, which was designed for all Protestants, not just Presbyterians. Its curriculum was ‘broad and liberal’, following the Scottish tradition drawn from the Reformation. Among the ‘professors’ Lang brought from Scotland was Dr Henry Carmichael, who soon left the Australian College to found a normal school in the Hunter Valley to provide non-sectarian teacher training.134

By the early twentieth century, Scottish influences were represented in the New South Wales education system in a number of ways. Some Presbyterian secondary schools had emerged; however, the English public school tradition’s focus on sport and the formation of character had come to prevail over Scottish ideas of intellect and merit in many of these schools. The best example of this trend was The Scots College in Sydney. Founded in 1893, the college adhered to principles that owed less to the ideal of the ‘democratic intellect’ and more to Thomas Arnold’s moral and intellectual principles – now interpreted as a form of ‘muscular Christianity’ – which celebrated sport.135

Scottish influences were more clearly seen at the University of Sydney. There was a significant Scottish presence at the university from its foundation in 1850. Scotland was the birthplace of more than one-fifth of the small number of academics at the university between 1850 and 1890. Many of these academics had been educated at the University of Edinburgh – almost as many had degrees from Edinburgh as from Oxford.136 In the next half-century, Scots continued to constitute at least one-fifth of the academics at Sydney, and degrees from Edinburgh, Glasgow, St Andrews and Aberdeen were prominent.

The role of Scots in the public school system that emerged in the late nineteenth century was equally significant. From the 1860s, the Presbyterian community in New South Wales abandoned its own government supported elementary schools to patronise state public schools. Increasing numbers of school

45teachers and inspectors of public schools were Scots by birth or origin. These Scots promoted ideals of opportunity and merit based on academic achievement.137 This was what Mackie found when he arrived to take up his new post: a climate similar to the educational environment he had emerged from.

Peter Board, the son of a Scottish migrant and director of education in New South Wales, and another Scot, Mackardy, the acting principal of the new Sydney Teachers’ College, met Mackie at the wharf. Mackie soon dismissed Mackardy, describing him as ‘a little elderly man of about 50 with a fierce moustache like a sea lion’s’.138 Board was another matter. In his departmental report for 1906, Board had already endorsed Mackie’s appointment, stating that Mackie ‘brings with him a very extensive knowledge of educational methods and of systems of training, as well as a varied experience of teaching in both primary and secondary schools. There is a good reason to believe that under his management the Training College will take a high place among institutions of that character.’139 The relationship between Board and Mackie blossomed once they met.

Peter Board’s career provides a clear example of the influence of the Scottish diaspora in New South Wales. His family and professional background made his appointment as director of education particularly significant for Mackie. Board’s father had migrated from Scotland in 1842 to farm. He became a teacher after the birth of his son Peter in 1858. Peter’s mother’s brother, the Reverend Archibald Cameron, was a Scots graduate appointed to the Manning River parish and a follower of John Dunmore Lang. Educated at his father’s schools, Peter Board was serious and studious. He had an early association with the University of Sydney; he attended the Fort Street ‘model school’ and completed the university’s junior exam. In 1873, at age fifteen, he became a pupil teacher. Twelve years later, as a trained and experienced teacher, he became one of the first of a small group of evening students to enrol at the University of Sydney. Board graduated with a BA in 1889 and an MA in 1891, gaining second class honours in mathematics. As part of a fragment of Scottish culture in the Antipodes, he became an example of the modern ‘dominie’ transposed to New South Wales.

46After twenty years as an inspector of schools in rural and metropolitan areas, in January 1905 the new state government under Premier Joseph Carruthers appointed Board to the position of under-secretary of the Department of Public Instruction and to the newly created post of director of education. Most see Board as a harbinger of reform in New South Wales, albeit with predilections towards academic curricula for elite students and more vocational subjects for the majority of pupils.140 Overall, he became a major agent of change in public education in New South Wales.

After his luggage was taken to the Hotel Australia in Pitt Street, Mackie spent the afternoon with Board at the director’s offices. In a letter to his father, Mackie described Board as ‘a very nice fellow, somewhere over forty and I think that we shall pull very well together’. Mackie also met various others and concluded that, while he could not remember names, ‘they were all very cordial and in fact there is much less reserve among people here than at home’.141

Contexts for change

Mackie had arrived in Australia at a moment of heightened hopes in education. The federation of the Australian colonies in 1901 had created paths for educational reform, not so much through the new Commonwealth government as through the states. Under the Commonwealth Constitution, the states held residual powers in important areas such as education, which encompassed public schools and universities. Following the 1890s depression, there was a new emphasis on students, rather than the formal curriculum, in education politics, accompanied by active policy making. A form of educational renaissance emerged, accepting parts of the ‘New Education’, which was already having an impact in Britain, Europe and North America.

In the early twentieth century, foundations were laid for a public education system, which would remain the focus of government action for at least the next half-century. There was more emphasis on the practical aspects of what became known as ‘primary schools’, and various types of secondary schools emerged,

47including academic high schools for the elite and vocational and continuing education institutions for the rest of the pupils. There were also efforts to include universities in this public education system. Among the Australian states, New South Wales became the leader in new forms of nation building, extending its school system and increasing opportunities. Developments were often based on the principles of merit and academic credentials that had shaped education in Edinburgh in the late nineteenth century. Building the nation through education was conceived as part of Australia’s contribution to the Empire.142

These changes had major implications for the education and professional training of teachers. From the early nineteenth century, the Australian colonies had mirrored the trajectory of teacher education in England and Scotland. This led to the adoption of a number of experiments in New South Wales, including a brief trial of the monitorial system. By the 1850s, the English-based pupil teacher system had been introduced in the Antipodes, just as a similar system was emerging in Scotland. For half a century, males and females, often aged only twelve, were recruited from within public schools, learning to teach through four-year apprenticeships. Some were awarded scholarships to attend the model school at Fort Street for a few months.143 In contrast to the approach in Britain from the 1840s, there were no efforts in Australia to develop teachers’ colleges associated with the churches. Rather, the colonies regulated and provided trained teachers for their own schools.

The growth of the public school system led to a search for new methods of teacher training. In New South Wales, English-born William Wilkins, who trained as a pupil teacher under James Kay-Shuttleworth (the United Kingdom administrator of schools from 1839), became the head of the Fort Street model school and then the chief administrator of public schools. In the 1870s, Wilkins travelled overseas to study teachers’ colleges. The Parkes government of the 1880s was strongly committed to public schools. With the enactment of the 1880 Act – and its principles of ‘compulsory, free and secular’ – the government accepted the need

48to extend training for men at Fort Street and to establish a residential training college for women at Hurlstone Park.144

For much of the nineteenth century, Australia’s universities played little role in the formal training of teachers. The public examinations of the University of Sydney and University of Melbourne, introduced in the 1860s, were open to both school students and teachers, allowing them to undertake further studies in the humanities and sciences. The University of Sydney thereby encouraged an academic meritocracy through matriculation. It also influenced the curricula of boys’ and girls’ secondary schools in New South Wales, including some public schools, such as Fort Street, which produced not only future teachers but also many of the colony’s academic elite.145 However, the public school system and the provision of teacher training had no direct relationship to the university. In part, this was because the colonial public schools were for the ‘people’, while the university was designed for the academic elite.

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Australia’s universities had begun to assume a more prominent role in the professionalisation of teaching. In 1876, the newly established University of Adelaide allowed students to attend classes without matriculating. Many of these early students were female teachers seeking to upgrade their qualifications. Thus Adelaide became the first Australian university to admit women and initiated a new relationship between Australian universities and school teachers.146

The admission of women to the University of Sydney from 1881 was indirectly associated with curriculum reforms, including the introduction of new academic disciplines and the creation of a Faculty of Science. By the late 1880s, there were also moves to include the university in the education and professional training of teachers. The University of Sydney entered into negotiations with the colonial government over a proposal – initiated within the professoriate – to allow some students from the teachers’ training colleges to undertake studies at the university.147 The initial negotiations broke down. But in the 1890s, Joseph Carruthers,

49then minister for public instruction and a graduate of the University of Sydney, proposed that not only should training college students be allowed to attend the university, steps should also be taken to locate a teachers’ training college within the university grounds.148

The growing recognition of teachers and education within Australian universities was related to both local needs and new perceptions of the Empire.149 Australia’s attachment to the Empire in the late nineteenth century was associated with the colonies’ culture and identity as well as matters of defence and trade.150 Education in the dominions of settlement, and in domains of conquest such as India, had long been part of the mission of the Empire.151 Throughout the Empire, common patterns of education had emerged with the creation of state school systems and the foundation of state-sponsored universities. By the early twentieth century, the sharing of knowledge among the universities of the Empire was accomplished through networks of research and teaching. Relationships with other academics in the Empire were cultivated through correspondence, direct contact and more formal conferences.152 This network of research and sharing of knowledge paralleled general international movements, such as the New Education in Europe and America, which focused on child-centred curricula. But ideas of and connections to the Empire remained preeminent in Australian teacher education until well into the twentieth century.153

Ideas formed in Scotland were part of the New Education movement. The most significant Scots-born academic at the University of Sydney in the area of education was Professor Francis Anderson, who was a prominent supporter of Alexander Mackie. When Mackie arrived in Sydney, Anderson’s influence within the university and in the general community was at its height. He had become an icon of educational change, attracting attention through his ideas, style and general approach.154 One of Anderson’s students recalled:

50

He was old-fashioned in dress and manner, combining a straw (boater) hat with a huge open, starched collar. He walked up and down as he lectured, in a very long gown, and frequently drew his curious, triangular head down into that vast collar, so that, as he paced his philosophy platform, he looked like a tortoise training for a race with the hare. … “Andy” had a rather sepulchral voice, which became shrill and electric when he raised it to stress a point or make a humorous sally. He was one of the few university teachers who knew students by their name and talked to them in the tram.155

Anderson sought to engage with both students and the wider community. With his background in philosophic idealism, he sponsored the foundation of new academic disciplines in the social sciences at the University of Sydney – including anthropology and education – all of which were located in the expanded Faculty of Arts.156 By the eve of World War One, he was influencing a generation of undergraduates, including the young Herbert Evatt, who became a High Court judge and then the leader of the federal Australian Labor Party.157 Knighted after his retirement, Anderson’s achievements were later engraved in stone; a commemorative fountain was constructed at the University of Sydney, opposite the Anderson Stuart building.

From the late nineteenth century, Anderson was involved in a number of educational organisations and causes. Through the Kindergarten Union, he met Maybanke Susannah Selfe, whose father had been involved in technical education. They married and formed a partnership for educational reform.158 Following Federation, Francis Anderson extended his influence into the politics of public school reform. He began a major campaign for change, including overhauling teacher training.

On 26 June 1901, at the annual conference of public school teachers, Anderson delivered a clarion call to the community and government. He criticised the whole system of public education; his critique of its leadership, the pupil teacher

51system and the training colleges was particularly severe. His student (later Professor) Elkin wrote: ‘Those of us who attended his lectures in the days of his prime, can well imagine his incisive tones cleaving the air in the manner of the prophet Amos.’159 The press indicated that the effect of Anderson in full flight had been electric: ‘Women were standing on chairs waving their handkerchiefs and parasols, men were stamping and shouting and shaking hands with perfect strangers.’160 Anderson published his speech in full – with certain additions – in a pamphlet entitled The public school system of New South Wales. In the pamphlet, he drew attention to the failings of the pupil teacher system and the associated training colleges – ‘the greatest defect in our system, the blackest spot upon our “glorious luminary”, the fault which most urgently stands in need of correction’.161

Anderson continued his campaign for reform from within the University of Sydney, playing an important role in engaging the university in contemplation of the nature of the public school system. For the first time, a University of Sydney professor had begun a major debate over the future of public schools. Anderson published articles in the university magazine, Hermes, on the role of universities in national education. He pointed out that teachers in public schools had ‘for many years been practically excluded from any direct participation in university instruction’, and noted that the study of education in the university ‘remains without its professor’ and that no place had been found in the university for the ‘professional training of teachers’.162 There seems no doubt that these views drew upon Anderson’s understanding of the emerging role of universities in teacher education and training in Scotland.

In November 1901, Joseph Carruthers, then leader of the opposition, called a meeting at the Sydney Town Hall. His aim was to pressure the premier to establish a royal commission or a committee of experts to enquire into the state of the public school system. While Anderson was the chief speaker, Carruthers took the opportunity to push for a deputation to meet with Premier John See and John Perry, the

52minister for public instruction.163 In early December, See and Perry conferred with a deputation including Carruthers and Anderson. Once again, Anderson argued that the need for proper teacher training was a critical issue. Another member of the deputation was the chief statistician for New South Wales, G.H. Knibbs, who handed the premier a document outlining arguments in favour of a royal commission. Knibbs was a statistician and surveyor, an author of numerous publications, and a lecturer in geodesy, astronomy and hydraulics at the University of Sydney from 1890 – a further indication that school reform was being taken up at the university.164 By January 1902, Perry had informed a meeting of Department of Public Instruction officials that he would appoint two officers to ‘inquire into education abroad’ to see whether the system in New South Wales was meeting the needs of the times.165

In early 1902, the New South Wales government appointed two commissioners to undertake surveys and enquiries in Britain, Europe and North America. The first was Knibbs; the second was John Turner, a former pupil teacher who became a headmaster and was then promoted to the Fort Street model school. These appointments struck a balance between a declared educational reformer and someone within the leadership ranks of the public school system. Over the next five years, the commissioners drew upon international examples to guide reform in New South Wales. Among their early recommendations were proposals to improve teacher training and appoint a director of education.166

Even before becoming director, Peter Board had been caught up in the education reform movement in New South Wales. In 1903, he went abroad on leave, taking the opportunity to compile a report on primary education, which soon became even more influential than Knibbs and Turner’s more voluminous report.167 By 1904, Board was playing a major role in a conference convened by the minister for public instruction, which included the commissioners and representatives of the University of Sydney and of the community. The conference

53carried resolutions that called for the abolition of the pupil teacher system, the establishment of a chair of pedagogy in connection with the university and the provision of a normal school with a practice school attached.168

The debate over the future of teacher training went well beyond what Wilkins had sought when he went abroad just two decades earlier and what some university professors had urged in the 1880s. Once appointed director of education, Board placed emphasis on reforming teacher training with the aims of phasing out the pupil teacher system and providing full-time pre-service preparation. In 1905, steps were taken to replace the pupil teacher system with a new form of ‘previous training’ of teachers. Board announced the establishment of a college within the grounds of the University of Sydney, offering a two-year course of training with provision for students of ‘special ability’ to graduate from the university after a third year of study. In the meantime, the school buildings at Blackfriars, near the university, would become a ‘temporary training college’. By March 1905, the training of male students had been transferred from Fort Street to Blackfriars; they were joined later in the year by female students from Hurlstone.169

There is little doubt that both Anderson and Board had significant connections with the selection committee that recommended appointing Mackie. The use of a selection committee in the United Kingdom was based upon the longstanding practice for professorial appointments at the University of Sydney. Following this practice to select the principal of the teachers’ college implied that candidates would need to have an academic standing equivalent to a professorial appointee. Francis Anderson probably played a significant role in advising the government – and Board in particular – on the composition of the committee. Anderson and Professor John Adams, the chair of the selection committee, were old friends from their days at university in Glasgow. It is likely that Anderson also suggested John Struthers, the head of the Scottish Department of Education, as a member of the selection panel. Finally, Anderson may have advised Adams to convey to Mackie the possibility that a chair in education might accompany the position of principal of Sydney Teachers’ College.170

54The Australian Journal of Education reflected on the significance of Mackie’s appointment: ‘That gentleman comes to us with the centuries of practical interest in and knowledge of education which Scotch parentage implied, and with several years of experience in Wales, one of the most lively quarters in matters educational to be found in the British Empire.’171 It was beginning to seem that new opportunities – and not the Antipodean reptiles of his aunt’s imagination – were awaiting Mackie in the Empire.

Introducing the new college principal

Before Mackie’s arrival, Anderson and Board had been the main proponents of changes in teacher education. The new principal soon became the subject of major attention from the press and teachers. In the days and weeks after his arrival, Mackie’s introduction to schools, teachers and pupils in New South Wales proceeded apace. In the few weeks before Christmas 1906, Mackie established personal contacts and addressed public meetings. Much can be gleaned from the almost daily letters he sent to his father in Edinburgh.

The day after his arrival, Mackie visited the training college at Blackfriars, where 200 students were enrolled. He returned to the city to lunch with Broughton Barnabas O’Conor, the recently appointed minister for public instruction. A graduate of the University of Sydney, O’Conor was the youngest member in the New South Wales government, aged thirty-six.172 Mackie also met representatives of the Public Service Board, which oversaw the civil service. In the evening, he visited Peter Board’s home to meet members of the Presbyterian community.173

The weekend after Mackie arrived, he and Board travelled by train to Windsor, on the rural fringes of Sydney. A nature study exhibition was being held there, involving thirty to forty schools, with both children and parents examining the

55work sent in from participating schools. Mackie agreed to give a talk, writing to his father ‘So my first public appearance was made at Windsor’.174

Having arrived at the end of the school year, with Christmas approaching, Mackie had to face a number of audiences – particularly from the teaching profession – who were eager to hear his views. The Public School Teachers’ Association invited him to speak at a dinner held in Pitt Street, Sydney, on 27 November. A little overwhelmed and unused to the fuss, Mackie wrote to his father before the event that he was not looking forward to his ‘execution’. He expected it to be the biggest audience he had ever addressed, with over 200 men and women present.175 He had various supporters in the audience, including Peter Board and Professor Anderson. Also present was another Scot, Horatio Scott Carslaw, professor of mathematics at the University of Sydney since 1903. Born in Scotland and educated at the University of Glasgow and University of Cambridge, Carslaw was committed to research and to improving the standards of mathematics in schools. He would play a major part in the debate over reforms to secondary education that Board would implement in the following years.176

The local Evening News provided an extensive report of the dinner under the headline ‘A teacher of teachers’. According to the report, the host of the dinner, P.J. Nelligan, the head of the Public School Teachers’ Association, welcomed Mackie, suggesting that the ‘desire for improvement and reform’ came from the ‘ranks’ of teachers in New South Wales. As director of education, Board proposed a toast to the new principal, stating that Mackie had come to Sydney after an ‘education revolution’ had taken place in New South Wales. There was a ‘certain irony’, Board said, in the fact that Mackie had begun his career as a pupil teacher, a system that was coming to an end in the state. The Evening News report mentioned that Mackie had ‘come from that University which had produced some of the finest scholars in the old land – Edinburgh’. Board stated that ‘the position [Mackie] had come to Sydney to fill was just as important’ as his academic posts in Edinburgh and Wales, ‘for no training college in England, Scotland or Wales would have a greater number of teachers than the splendid college that within eighteen months

56would be ready for Professor Mackie’. Board’s reference to a future professorial title for Mackie was almost confirmed when Professor Anderson, who was also on the stage at the meeting, stated that while the Department of Public Instruction and the University of Sydney were once on ‘different sides of the fence’, that fence had been pulled down and the ‘two sources of learning were now commingled’.177

The press report of this meeting indicated that the college principal was proposing a new era in teacher education in Australia. In his address, Mackie reflected first on the honour he was being accorded. He also discussed his own education and learning and gave indications of possible future directions for teacher education under his supervision as principal. ‘Though he could never forget the 30 years he had spent in Scotland’, Mackie ‘hoped soon to be able to look upon Australia as his second homeland’. According to the Evening News, Mackie described the present as a time of ‘upheaval’, the like of which had not been seen since ‘Socrates pointed out the fallacies of the Sophists’. Mackie believed that there was hope for ‘educational progress’, provided that the educational administration worked with the ‘social and economic structure of the State’. He argued that the pupil teacher system had ‘outlived its usefulness’, not only in the ‘older countries of the world’ but also in Australia. The press report noted that Mackie presented ‘two main points in the training of the teacher’: ‘first, he should receive a thorough general culture in academics and in the techniques of his art’ and ‘secondly, that he should carry the academic training so far as to obtain a degree in arts or sciences’. There should be no differences between primary and secondary teachers, Mackie suggested, and ‘no obstacle placed in the way of obtaining a University education for young teachers’. As such, he held out the prospect of a teaching profession founded on university credentials, rather than the traditional model involving different qualifications for primary and secondary teachers.178

57In the three weeks before his first Christmas in Australia, Mackie spent time with Board and at the Blackfriars college, while continuing to extend his professional and social contacts. In particular, he came to know more of the university and its colleges, telling his father that of the three male colleges ‘as you might expect the Presbyterian (St Andrews) is more vigorous and flourishing than either the RC (St John’s) or Episcopalian (St. Paul’s)’.179 Mackie soon developed a rapport with Harper, the principal of St Andrews, and Prescott, the longstanding head of the Methodist Newington College. He also met Professor Wilson in anatomy, a friend of James Seth.180

Just before Christmas, Mackie addressed two important groups. First, he spoke to the Kindergarten Union, with Anderson present. He suggested that kindergartens had helped to free state elementary schools in Britain from ‘the mechanical precision, deadly monotony and rigidity which had so long characterised them’ – words very similar to the criticisms Anderson had directed against New South Wales public schools in his famous speech in 1901. According to a report in the Sydney Morning Herald, Mackie claimed ‘kindergarten was not a separate form of instruction, but an attitude of the mind towards infant teaching determined by certain well-defined principles of education’.181 As Mackie told his father, over 500 people were present, ‘mostly women of course’; ‘I was rather glad to get it over,’ he added, ‘for this was an appearance before a body outside the sphere of the education department’s influence and it may be useful to keep in touch with them’.182

A few days later, Mackie spoke to the annual public teachers’ conference. He wrote to his father:

My address at the Teachers’ Conference came off this morning. At the last moment I decided to talk and not to read the address I had prepared. The strains and exertions were greater but I think it was more successful. People listened very carefully and I think that I improved the occasion and rubbed in some truths I

58was anxious to impose at the beginning of my work here. The important people were satisfied and I was on the whole fairly well pleased with myself.183

A typed copy of the address Mackie had prepared survives in the University of Sydney Archives. It was entitled ‘The training of the teacher’. The substance of this prepared address is given here. It indicated the range of Mackie’s proposals for change. He drew upon his recent experience at Bangor, where he had trained kindergarten, primary and secondary teachers. Emphasising the importance of a ‘professionally trained body of teachers’ for a functioning education system, he outlined what he saw as the ‘leading principles’ for the future operation of Sydney Teachers’ College. The foundation of teacher training would involve ‘more ample professional training’, with more students undertaking university degrees. He expected that the increasing number of matriculants from state secondary schools would mean that more teacher trainees would be qualified to undertake university degrees. This would mean that, in the case of the university students in particular, it would be necessary to make such arrangements as would secure the right balance between university and the practical work of the college.184

In his written address, Mackie also argued that the course of study for teacher education should be ‘wide and liberal, cultural rather than journalistic’. He suggested that many of those entering the college would be more qualified in the humanities and in elementary science, and that undertaking courses in these subjects at the college would be ‘more profitable than language drill or much mathematics’. In specific courses, including history, Mackie proposed incorporating lectures and ‘laboratory work’ so that students could learn ‘the new methods of teaching the school subjects’. In elementary science and nature study, he advocated ‘direct experience and experimental work’.185

In the final part of his prepared address, Mackie noted the need for theoretical and practical work in the study of education. He suggested that theoretical work should include study of ‘the meaning and aims of education as a factor

59in social welfare’ – this contention reflected the influence of his colleague Darroch at Edinburgh. Mackie believed theories of education should involve ethics, psychology and logic, as well as the new field of child study, which would be developed by observing children in schools. He added that ‘some knowledge of the history of educational progress and of the great theorists is most valuable in order to secure breadth of view and permit a due understanding of many current tendencies in educational doctrine and practice’.186

Mackie ended his address to the public teachers’ conference by emphasising the need for teaching students to discuss the practical problems of pedagogy. He stated that the proposed training he outlined would not produce ‘the experienced teacher’, but rather ‘some facility in class management’. It would furnish a teaching student with the required tools and ‘open his mind to the possibilities of his profession’. In the written version of his address, Mackie concluded:

The science of education is slowly assuming definite outlines but cannot be assured unless there is a body of opinion capable of exercising intelligent judgment upon educational writings. If that were the case, the general level of educational discussion and writing would be much higher than it is at present. Improved theory would inevitably react upon practice, making it better and more intelligent … This truth is apt to be overlooked by the teacher engaged in the details of school work.187

The continuing use of the male pronoun in Mackie’s address was a reflection of his own education. Otherwise, this address illuminated many of his ideas in the emerging world of the New Education. His vision of a teaching profession with close associations to both training colleges and universities was clearly related to the situation in Scotland in the mid- to late nineteenth century. It also reflected developments in Europe and America, including at institutions such as the Teachers’ College, Columbia. Mackie’s references to new methods of preparing teachers that ensured they became child-centred took up some of the ideas

60of ‘progressives’ such as Darroch and Dewey. Overall, his address concentrated on the significance of such ideas for New South Wales.

Mackie managed to find time in his busy schedule to discover the natural environment of Sydney and its surrounding bushland and beaches. On a Sunday in early December, he visited the Andersons at their ‘country house at Pittwater’, crossing the harbour by ferry to Manly and then travelling for an hour and a half to reach the Anderson residence, which he described to his father as ‘beautifully situated on high ground at the head of a sea loch, an arm of the Hawkesbury’. Continuing to use parallels to well-known sites around Glasgow and Edinburgh, he told his father ‘if you think of the view from the head of the Loch Katrine [near Glasgow] you will know the sort of place’. The memories of his homeland were reinforced by ‘Scotland Island’ in Pittwater and ‘Glasgow Park’ on the shoreline.188

When he and Anderson went for a walk in the bushland in the afternoon, Mackie thought he could have been wandering around ‘Corstorphine Hill’ in Edinburgh, except for the ‘unfamiliar appearance of the trees’. Mackie wrote to his father that when they reached the top of a ridge with a view of the coastline and the ‘coastal belt of the flat wooden land’, Francis Anderson even suggested that the view was ‘very similar to the French Riviera and one promontory might very well have been taken for Monte Carlo’. Their comments provide an interesting reflection of two Scots-born academics seeking not just memories of their homeland but also the prospect of a more cosmopolitan Australia.189

Mackie continued to visit the Anderson house over the following years, apparently feeling at home in the villa ‘at the head of the finest west highland loch you know’. There was even a ‘housekeeper from Aberdeen’, who he described to his father as ‘kind but with a manner like Aberdeen granite and a marked Aberdeen accent’.190

Installing the college principal

In February 1907, the minister for public instruction, B.B. O’Conor, opened the new year at Sydney Teachers’ College. He spoke of a new vision for the college,

61suggesting that the ‘mingling of the teachers with the men and women of the university should have a great influence in the public life of the State’. He recognised the ‘manifest interest’ the university had shown in the teaching profession; ‘he felt more and more every day that the University was coming right down into the lives of the people’, a Sydney Morning Herald report stated. O’Conor noted that the college was available to primary and secondary teachers as well as students from all schools.191

Already the new college principal was being recognised as an effective, if quiet, leader. Though he was small in stature, Mackie’s voice had what A.R. Chisholm described as ‘a compelling quality that sufficed to solve all problems of discipline’. He did not raise it much; as a rule, Mackie spoke and moved softly, attracting attention in verse and song:

And the girls all call him Mackie, Mackie;

He treads as soft as a lackey.192

A crucial test for Mackie was ending the pupil teacher system. Throughout Australia, the nineteenth-century system of pupil teachers was being replaced by college-based professional training associated with the universities. In 1900, the Victorian government had reopened Melbourne Teachers’ Training College, which had been closed during the 1890s depression. In 1902, John Smyth, who Mackie knew from Edinburgh, had been appointed principal. In 1907, Smyth and a group of students visited Sydney to establish a sporting carnival that would bring the two colleges together. Over the following years, this led to intercollegiate competitions with interstate visits and fostered forms of college and student identity.193 Both Mackie and Smyth remained committed to their respective colleges and students, with the aim of creating a corporate life.

Mackie and Smyth were equally determined to establish new practices in teacher training. Given their experiences at Edinburgh, both had a strong attachment to the study of education and professional practice within a college

62and university partnership. But their strategies and opportunities led to different outcomes. At Melbourne, a university-based Diploma of Education was well established by 1905 and Smyth devoted much attention to teaching students in this program. But he gained little support from within the university. Significantly, because of government policy, Smyth was unable to create a college-based profession. Victoria maintained a system of single-teacher rural schools; this led to the continuation of the pupil teacher system, which the creation of the Melbourne Teachers’ Training College had been intended to end.194

In contrast to Smyth’s experience, Mackie received strong support from those in government administration and in parts of the university for at least the first decade and a half of his time in Sydney. Under Board’s oversight as director of education, Mackie’s appointment as principal of the college provided the opportunity to enact a program ending the pupil teacher system and introducing college training as the future of teacher education.

This reform proceeded in stages. Following a competitive examination, former pupil teachers could undertake a one-year course at Sydney Teachers’ College. Until 1910, these ex-pupil teachers, most of whom already held teaching positions in schools, formed the great majority of the college’s intake. Scholarships were introduced to assist those who were forgoing salary to upgrade their qualifications. There was also financial assistance available for some students who were not already in the public school system to enter the college, as it sought to meet the demands of the expanding student populations in public and other schools. As a further recruitment strategy, a probationary student scheme was introduced in 1906, offering allowances for students as young as fifteen who stayed in school with the intention of entering the college. This scheme remained in place for almost a decade, until the introduction of the new Intermediate Certificate in 1911 and the Leaving Certificate in 1916 consolidated formal secondary school credentials as the foundation for teaching careers.195

Sydney Teachers’ College was founded with the aim of producing teachers for primary schools – these schools were a compulsory component of universal education. Initially, the college offered one-year and two-year courses, providing

63different certification. Both courses included theoretical studies and practical experience in classrooms in local demonstration schools, including Blackfriars. Given his academic attainments in Edinburgh, Mackie was initially disappointed in the general education of entrants to the college. He believed the limitations of their prior education imposed a double burden on college students as they sought to improve their academic work while undertaking classroom practice. It was not until the introduction of the state-created Intermediate and Leaving Certificates in secondary schools that the standard of the college’s recruits began to improve.196

There were early advancements in staffing at Sydney Teachers’ College. By 1911, some of the staff had qualifications equivalent to academics within the university. One of the early appointments was L.H. Allen, a classical scholar who had attained his doctorate in Germany. A poet and a student of Virgil, he taught at the University of Sydney and the college until 1918, when he became professor of classics at the Royal Military College at Duntroon. In 1909, Percival Richard Cole arrived at the college. Cole had completed a doctorate at Columbia University in New York and would teach educational psychology and the history of education. He co-authored a number of books on teaching with Mackie. Henry Tasman Lovell lectured at the college in the theory of education and in German and French.197 He held a doctorate and soon became professor of psychology at the University of Tasmania.

The college also provided opportunities for young scholars and teachers. James Fawthrop Bruce was a former pupil teacher who had spent eight years teaching before undertaking four years of study at the college. He graduated from the University of Sydney with first class honours in English, philosophy and history. Beginning as an assistant lecturer in education, he became a lecturer in history at the university and an assistant to Professor George Arnold Wood. In 1928, he became a professor of history in Punjab.198

There were few women on staff at the college. Mackie sought to assist the career of Martha Margaret Simpson, who was the mistress of infants at Blackfriars.

64She was appointed to the college staff in 1910, after she had developed kindergarten teaching methods in about twenty schools in Sydney. She had difficulty getting recognition and pay for her duties as a lecturer as distinct from her role as infants mistress. As in other cases, such as the role of warden of students, the few women lecturers at the college found that they were discriminated against by the rules and regulations enforced by the bureaucracy.199

Through such early appointments, Mackie attempted to assert that the college was an essential part of the university. As early as 1908, Mackie told a departmental enquiry into salaries at the college that ‘the only comparison is with the University. The Training College is, in spirit, if not in fact, a Department

65of the University’.200 In later years, Mackie pointed out that Peter Board, as director of education, had encouraged this development, providing for the best possible appointments but leaving staff alone.201 This was a reflection of what had occurred in Scotland and England, resulting in the creation of departments of education within many universities. Both Board and Mackie hoped to emulate those trends.

Australia’s first professor of education

Almost a decade after Federation, governments in the individual Australian states were taking an increasing interest in shaping the modern public university. The Labor government founded the University of Queensland in 1909 as part of a program of state-sponsored economic development. By 1913, the University of Western Australia had become a ‘university for the people’, supported by private philanthropy and state grants.202 Around Australia, there were moves towards establishing chairs in fields related to professional occupations.

The reformation of teacher training and qualifications was part of a wider agenda encouraging professional education in universities. In New South Wales, the Liberal governments under Joseph Carruthers (1904–07) and Charles Wade (1908–10) negotiated with the University of Sydney over proposals for rural developments and over the issue of teacher education. These governments took up ideas from the 1880s, when Carruthers had been minister for public instruction. In 1889, William Wallace, professor of agriculture at the University of Edinburgh, had visited Sydney and urged the university to introduce agricultural education based on scientific principles and to create a chair in this area, mirroring the chair that had been established at Edinburgh a century earlier. Taking up this idea, Carruthers had recommended in 1889 that the university implement a comprehensive plan for agricultural education, building upon the proposed introduction of such studies in schools. This plan involved the creation of a chair

66of agriculture.203 Despite a favourable reception at the university, the 1890s depression put paid to the proposal. By 1907–08, these ideas had been revived in the university and the government, with an associated proposal to introduce courses and a chair in veterinary science. The university negotiated with the government for funding. By 1909, Robert Watt, a graduate of the University of Glasgow who had worked in South Africa, was appointed as the foundation professor of agriculture and James Stewart, who had studied at the Royal Veterinary College in Edinburgh and had experience as chief inspector of stock in New South Wales, was appointed professor of veterinary science.204 Once again, this strengthened the influence of Scottish ideas and practices within the University of Sydney.

This pattern of negotiations between the government and the university was repeated in the area of education. The government introduced proposals that, in part, dated back to Carruthers’ tenure as minister for public instruction in the 1880s. In March 1907, Peter Board approached the University of Sydney Senate with a request that the university provide a site on its grounds for a non-residential training college for 400 students. Board and Mackie then met with the chancellor and vice-chancellor, and Professors Anderson and T.W. Edgeworth David, both of whom were known supporters of Mackie. At this conference, Board indicated that his department intended for the majority of college students to be matriculants to the University of Sydney; he believed that those who did not matriculate would profit from attending at least two university courses. Within several years, he expected that ‘practically all the students would be of University rank, the larger number of them being matriculants’.205 The Senate agreed to grant a site of about three and a half acres between the Women’s College and University Oval, on two conditions: that the proposal was endorsed by legislation in the New South Wales parliament and that within five years all college students would be required to attend at least two courses of lectures during each year of their training. Plans for the college building had to be submitted to the university Senate for approval.206 Almost all of the proposals for the college were

67conceived in terms of the partnership between university and teachers’ college that Mackie had known at Edinburgh. However, the actual location of the college within the university remained uncertain for another half-decade.

Related to this agreement between the university and Board’s department were the issues of a proposed chair in education and of the teaching of education as a subject within the university curriculum. In October 1908, the minister for public instruction asked the university to recognise a college course on the theory of education, which Mackie suggested could count towards a BA at the university. The Professorial Board advised against this on the grounds that the course was only offered to college students; no provision was made to teach the course within the university so that it could be listed as a degree course; and the course would be given by a lecturer whose appointment was not controlled by the university Senate. But, on a positive note, the board proposed a solution: the subject of education could be taught by the university as part of the BA degree and offered to both arts and college students.207

Over the next eighteen months, Mackie was gradually integrated into the university. In the wake of the Professorial Board’s report, Peter Board proposed that a chair of education be established by promoting Mackie to professor and assigning him to teach university courses in education. But matters of academic autonomy intervened. At a university Senate meeting, Professor Mungo MacCallum argued that the university should not give the title of professor to someone over whom it could not exercise full control. Instead, he argued that Mackie should become a lecturer at the university – a proposal Board accepted. The Senate also agreed on the grounds that a chair appointment would have to await the allocation of government funds. In 1910, Mackie was appointed as a lecturer in education. But, in effect, his friend Professor Francis Anderson had bypassed this decision by seeking leave during 1909 and having Mackie appointed acting professor of philosophy, with responsibility for teaching courses in the field of education.208

In March 1910, Peter Board again recommended to the university Senate that Mackie be made a professor. The Public Service Board had proposed that Mackie’s position as principal should be made permanent, with a salary of £800.

68Board suggested that the University of Sydney contribute an additional £100 and make provision for a pension that accorded with those granted to other professors. The Senate concurred and agreed to make the appointment, dating from 1 March 1910.209

Mackie had already written to his father in anticipation of this decision. Describing the financial terms of the appointment, he pointed out that the university’s contributions would provide a pension of £400 per year, so that ‘After 20 years I can retire and claim the pension if I wish; at 60 years of age the University can if it desires retire me without any reason being given’.210 It was a prophecy that would come back to haunt him.

Mackie’s appointment as a professor at the University of Sydney was a major step for him personally and for the recognition of education as an academic discipline. He was the first to hold the title of professor of education in an Australian university. In April 1910, when his appointment to the chair was confirmed, Mackie wrote to his father about the progress he had achieved in his career, but also about his uncertain future and growing disillusionment with the central state system of education in New South Wales:

You will agree I am sure that it has been a long climb – 18 years I think counting from May 1896 when I first went to Canonmills as a pupil teacher. Whether or not it was worth the climb is perhaps a more difficult question to answer. I don’t know if the climbing is finished or not, or if I like the lowlands, I have got to pull up the ladder and begin afresh. For it is somewhat uncertain where I want to climb now. Certainly I do not want to be Undersecretary or Director for he is much more hampered by politicians than I. I can say what I think about the state educational system from the chair but he can’t speak out his mind. Perhaps I might set about writing a book but that you would say would give my enemies a chance they are better without.211

69Mackie’s appointment as professor of education allowed him to manage a close affiliation between the university and the teachers’ college. Three developments between 1910 and 1912 helped to clarify this relationship: the creation of a Diploma of Education for university graduates; the proposed construction of the college within university grounds; and the provision for college students who had matriculated to undertake a degree at the university without paying fees. These developments were closely related.

The Diploma of Education was instituted in 1911 as a one-year postgraduate qualification that was open to graduates in arts and science. Its curriculum emphasised principles in the theory and practice of education, including the history of education, class management and school practice. The diploma was a formal credential; it was taught by Mackie and the senior academics at Sydney Teachers’ College.212

In July 1910, Board and Mackie met with the chancellor, Sir Henry Normand MacLaurin, to again take up the question of the actual site for the proposed college. Born in Scotland, a graduate in medicine from Edinburgh University and the son of a schoolmaster, MacLaurin was also a member of the Legislative Council, CSR (the Colonial Sugar Refining company) and Sydney Grammar. Mackie told his father that with these contacts the chancellor had been able to persuade the state government to provide funds to complete the Fisher Library (which now stood on the eastern side of the University of Sydney Quadrangle). To Mackie, ‘the best plan’ was to build the college within the university grounds; but he wrote to William that ‘Board had always been suspicious of it as he thinks it will mean loss of control by the Department’. After ‘animated discussion’ between Board and the chancellor, the meeting failed to resolve the issue.213

By May 1911, the university Senate was discussing a bill for the construction of the college and for the attendance of college students at university lectures without fees – both matriculated students and those whose attendance at lectures was approved by the minister for public instruction.214 The confirmed site for the college was not in the Quadrangle, as the vice-chancellor had proposed

70and Mackie had preferred, but near University Oval, as envisaged in the original discussions between the university and Peter Board in 1908. The building and land was vested in the minister for public instruction, indicating that Sydney Teachers’ College was a government college, rather than a college of the university. Construction began in 1914. The building was completed by 1920 but not officially opened until 1925.215

The teachers’ college building was part of a new relationship between the government and the university. With the passage of the University (Amendment) Act 1912 (NSW), the location of the college was confirmed in the context of reforms that embraced the University of Sydney as part of the New South Wales public education system. Students at the teachers’ college were a major part of this process. The 1912 Act confirmed the University of Sydney as the public university it had been since 1850 and made it the pinnacle of a public education system involving schools and students. This legislation was introduced by the Labor government that had been elected in 1910, but it arose principally from ideas and proposals that Peter Board brought back from his trip to America in 1909. The Act provided more public endowment to the university and established the state-devised Leaving Certificate examination as the primary basis for matriculation to university. Furthermore, the reforms included 100 free places, known as ‘exhibitions’, to be offered to new university students each year, increasing to 200 by 1915.216

Of specific significance for the future of teacher training, students at Sydney Teachers’ College were offered free tuition if they matriculated to the university. The proposal had its origins in Carruthers’ 1889 scheme. It had been revived in 1902, following the end of the 1890s depression, but its effect was limited to a few students who qualified. Free university tuition for all matriculating college students was then confirmed as part of the arrangements for the construction of Sydney Teachers’ College. Free university education was also included in the state scholarship scheme for intending teachers. When the college opened in 1906, state scholarships had only provided fee relief and a small stipend. By 1912, the scholarship scheme was consolidated into a form of bonded service.

71Student teachers now had the prospect of a university degree, professional training at the college and a career in school teaching.217 With most students at the teachers’ college completing secondary school and matriculating to university, the way was open for a much closer relationship between the university and the college, as Anderson and Mackie had long intended.

This relationship became much clearer after 1912, with the expansion of secondary schools in New South Wales. By 1917, at least one-third of all entrants to the college had attained the Leaving Certificate and half of the students in the college’s two-year ordinary course had matriculated to the university. Mackie now claimed that within the college ‘the change from a mainly academic course to a mainly professional course is complete’.218 The university provided a foundation

72in academic subjects, while the college moulded students as professionals, instructing them in methods of teaching as well as the psychology, philosophy and history of education.

Region and gender became significant issues in the composition of the emerging teaching profession. Country high schools, in particular, became a source of future teachers, while female trainees made up more than half of the entrants to the college. Such trends had been apparent almost from the opening of the college, but they became more pronounced during World War One, beginning in 1914.219 The establishment of Teachers’ College Scholarships opened up new professional opportunities for women. In the two decades after 1920, approximately two-thirds of college entrants were female. Most entrants came from the metropolitan and country high schools that Peter Board had created, but about twelve per cent were from Catholic schools.220

Academic teaching subjects were effectively transplanted into the university, where teacher trainees who had matriculated could pursue a degree. In 1917, 146 females and fifty-five males from the college were studying at the University of Sydney. Of these, forty-four women and twenty-eight men were on the ‘honours list’, having gained a credit, distinction or honours in a specific subject. The number of college students within the university had grown so great that regulations had been prescribed. College students who had matriculated could pursue a degree in arts, science, economics or agriculture. Those who passed their first year with credit or distinction could continue their course at the university. Others would be required to discontinue their university studies and devote a year to professional work at the college – these pupils were soon known as ‘returned university’ students. A similar provision applied at the end of the second year, allowing students who achieved distinction to continue at university and requiring others to return to college. Those who completed a third year at the university would be required to undertake professional training for the Diploma of Education.

These regulations formalised the relationship between professional studies at the college and academic studies at the university. The provisions for continuing a university degree helped to create a future academic elite within the teaching

73profession. This was not so different from the approach that governed teacher training when Mackie was in Edinburgh; ideas of merit and an honours program prevailed. But the relationship between the university and the college was far from settled, as would become clear in future years.

A shining light in the Empire

The creation of Sydney Teachers’ College elicited interest well beyond New South Wales. When Alexander Mackie visited Britain during extended study leave in 1921, he delivered a paper on ‘The universities and the training of school teachers’. His focus was on the University of Sydney, but he also referred to Australian universities in general. Pointing out that public education was the responsibility of each Australian state, he noted in this paper that ‘Professional training for teaching in primary and in secondary schools is provided by the Universities and by the Education departments’, which control ‘Colleges for Teachers’. The universities exercised no ‘direct control’ over the colleges. However, in every state except Western Australia the teachers’ college was on or adjacent to university grounds; staff in the colleges often held positions in the universities.221

By the 1920s, Sydney Teachers’ College was by far the most significant teacher training institution in Australia. The college had over 1,200 students – more than were enrolled in the rest of the colleges in Australia combined. Melbourne Teachers’ College had less than 400 students.222 According to Mackie, particular circumstances had shaped teacher training in Sydney, providing a new engagement between the university and the college. Mackie was professor of education and head of the college; the college’s vice-principal was a lecturer in education at the university. Lecturers from the college were in charge of the university’s evening course in education and its postgraduate course in experimental education. Like other Australian universities, Sydney offered courses in the theory and history of education and a university diploma for graduates, which the Department of Education recognised as a qualification for public school teachers. Mackie believed

74that control of Sydney Teachers’ College should be transferred to the university Senate; in ‘The universities and the training of school teachers’, he noted ‘I am of opinion that the change would be beneficial to the University, to the College, and to the teaching profession in general’.223 In 1920, 389 of the students preparing to teach in New South Wales were undertaking university courses. So ‘the University exercise[d] a strong influence in forming the character of the abler among the future teachers’.224

The benefits of its close association with the university were reflected in the staffing of Sydney Teachers’ College. A number of lecturers appointed during the 1920s had graduated with honours from the University of Sydney. Of particular note were students of George Arnold Wood, the professor of history, including H.L. Harris, who later became director of youth welfare in New South Wales, and Harold Wyndham, the future director-general of education. Wyndham taught education at the college between 1925 and 1927, while researching his Master’s thesis on the Italian Renaissance. He left to undertake doctoral studies at Stanford. As Brian Fletcher has argued, in many ways, in the interwar years Sydney Teachers’ College had more active research scholars than most departments in the university’s Faculty of Arts.225

W.F. Connell has suggested that four main fields of education research emerged in Australia before World War One: child study, history of education, school achievement and mental testing. Dewey and Darroch were international supporters of child study. In New South Wales, the Department of Public Instruction had a strong interest in studying children, particularly in terms of physical development. In 1913, Thomas T. Roberts, a lecturer at Sydney Teachers’ College, initiated surveys and questionnaires to examine children’s development. The college’s vice-principal, Percy Cole, was an international scholar on the ancient and contemporary history of education. By the early 1920s, a number of scholars from the college, including Cameron, Phillips and Roberts, had initiated studies of school and pupil achievement. But the most significant developments arose in the field of mental testing, adapting the work of Binet in France. Research in this

75field at Sydney Teachers’ College began with Cameron in 1908; Sydney researchers followed examples from Melbourne Teachers’ College to carry out testing in the field and the laboratory.226

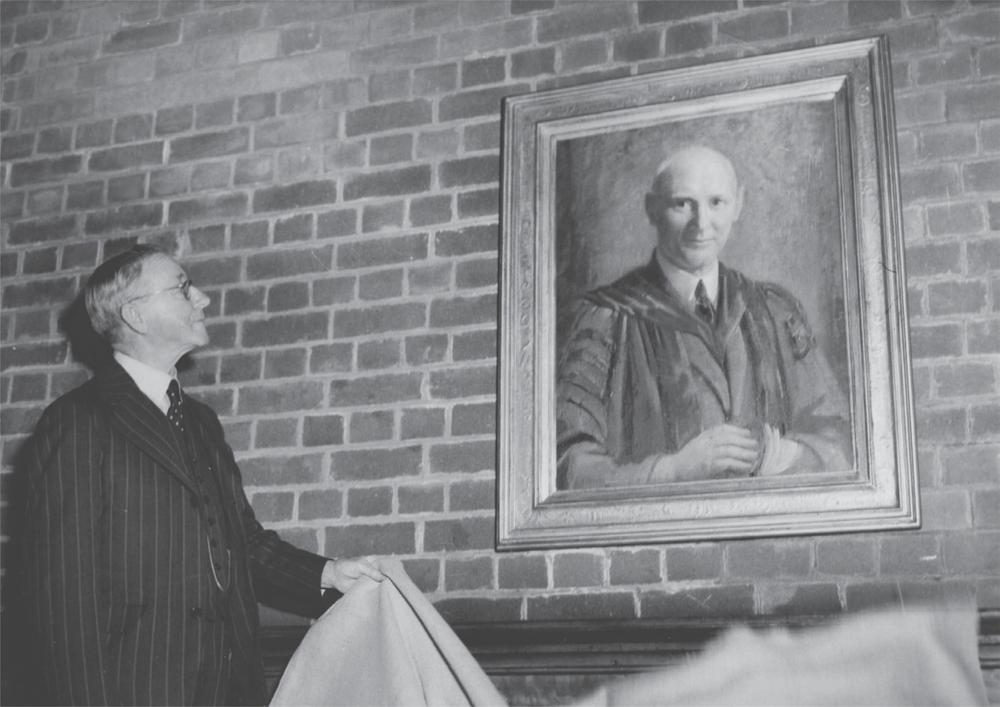

Formal praise for Mackie’s achievements at Sydney Teachers’ College was a little late in coming. In December 1926, a commissioned portrait of Mackie by the well-known wartime artist George Lambert was unveiled at a formal ceremony. A number of public figures associated with the development of the college were in attendance, including W.A. Holman, the former premier (1912–15) whose government agreed to move the college onto the university grounds, Mungo MacCallum, the vice-chancellor, and Peter Board, who had retired as director of education. Percy Cole pointed out Mackie’s achievements, including the college’s art collection, the ‘country camp’ for students and the advancement of the ‘cause of experimental education’ and the Montessori method in pre-schools. Holman said that teaching in New South Wales had been transformed from a ‘trade’ into a ‘profession’. MacCallum and Board spoke of how Mackie had framed the ‘characters’ of student teachers.227 In reply, Mackie reflected on how he had come to Australia, thanking Sir John Adams and Sir John Struthers for the ‘opportunity’ they had given him and recognising Francis Anderson’s and Peter Board’s support. He concluded:

He had often wished the college could become an organic part of the University. If such a dream could come true students would continue their studies to a stage more advanced than that reached by them at present. Nothing could do more to improve the status of the teaching profession than the presence in its ranks of a body of men and women of distinguished scholarship.228

Keeping the college alive and active

Despite Mackie’s hopes for the future of teacher education, economic and political priorities soon turned in other directions in the postwar world. Australia was still

76tied to the Empire, but through the mantra of ‘men, money and markets’ rather than the ideas and idealism of the prewar period, when educational change had seemed achievable. The Commonwealth and state governments saw the settlement of Australian ex-soldiers and British migrants on the land as providing a basis for economic productivity, borrowing from Britain to fund settlement schemes.229 Expenditure on social services grew, but much of this went to income support measures, such as widows’ pensions and child endowments, that were introduced in New South Wales by the Lang Labor government in the 1920s. State funding for education mainly concentrated on supporting the expanding school population, rather than the university and the teachers’ college.230 Allowing college students to proceed to a four-year degree, rather than qualifying with just two years of training, was increasingly seen as a costly luxury that was delaying the entry of new teachers into the profession.

In this climate of ‘economic restraint’, the University of Sydney and Sydney Teachers’ College were not drawn closer together. If anything, they drew further apart, in spite of Mackie’s efforts. By 1922, Mackie had lost his supporters Francis Anderson and Peter Board, who had both formally retired. Mackie failed to find many academics at the University of Sydney who would support him the way Francis Anderson had. Scots-born John Anderson, who succeeded Francis Anderson as Challis professor of philosophy, became Mackie’s friend. But as a Marxist-influenced materialist, he was opposed to the growth of pragmatism and the emergence of the ‘Deweyites’ in the discipline of education in Scotland.231 As one example of the continuing distance between the university and the college, the Professorial Board refused to recognise college courses in education, while accepting that Mackie and other college staff taught university courses at undergraduate level and as part of the Diploma of Education. This situation was not unique to Sydney. Overall, the distance between Australia’s universities and the newly established teachers’ colleges increased during the interwar years. Financial pressures and a decline in state grants hindered new developments.232

77Peter Board’s retirement was particularly significant for Mackie. The new director of education, S.H. Smith, was a former pupil teacher who did not share Board’s support for university graduates in the teaching profession. Smith insisted on the need for more teachers, rather than graduate teachers, and so refused to support the practice of teacher trainees attending the university. In 1924, he even changed arrangements for teaching students studying at the university. Only those undertaking an honours degree could proceed to graduate; others were required to ‘return’ to the college to qualify with a certificate. Smith also sought to exercise control over Sydney Teachers’ College as part of the New South Wales public education system. Smith and Mackie clashed on issues of authority and independence. As principal, Mackie sought to both protect and promote his staff, who were often frustrated by the rulings of the Public Service Board – their employing agency. In the 1920s, and even into the 1930s, Mackie constantly proposed that the only answer to these dilemmas was for the college to become more independent of the government, perhaps as a college of the university. It was an argument that he was unable to win.233

The growing influence of the bureaucracy and the increasing distance between colleges and universities was not exclusive to Australia. It was occurring in Scotland and throughout Britain. In 1905–06, Alexander Darroch, Mackie’s friend at Edinburgh, responded favourably to the idea that the four universities should associate with training colleges in ‘provincial’ schemes, leading to the possible integration of colleges into the universities, which were expected to play a leading role in teacher education. But the head of the Scottish Department of Education, Struthers – who had been on Mackie’s selection committee – made it clear that the bureaucracy must retain control over the training of elementary teachers, leaving the universities in a subsidiary role. The Scottish universities turned to promoting research, leaving undergraduate pre-service training to the colleges.234 At the Second Congress of the Empire in 1921, there was an emerging view that the university sector in Britain and the Empire could not absorb large numbers of trainee teachers who might prefer a life in a teachers’ college over being on the margins of a university. In 1925, a departmental report of the Board

78of Education for England and Wales reinforced the view that training colleges and university departments of education should operate in separate spheres, with limited scope for co-operation.235

At Sydney, Mackie continued to straddle the roles of college principal and university professor, even while he suffered financially. Under the terms of his appointment as professor of education, Mackie received an annual salary of £800 from the Department of Education, entitling him to state superannuation benefits. The university initially ‘topped up’ his salary with contributions towards a future pension. In early 1927, someone – no doubt S.H. Smith – informed the State Superannuation Board that, as a part ‘employee’ of the university, Mackie was not entitled to state superannuation benefits, and he was removed from the scheme. Legal opinion later indicated that Mackie had been denied justice in this matter, but by then he had accepted the decision. In November 1927, the director of education added further spite by suspending Mackie from his position as principal for a week. Smith informed Sir Mungo MacCallum, the vice-chancellor of the university, that Mackie had been appointed as both principal and professor, and the appointment required the concurrence of the university Senate and the Department of Public Instruction.236 The result was that the department and the university would continue to pay Mackie’s salary, but he would receive no state superannuation in the future – only pension payments from the university. And as principal, Mackie was expected to give due respect to the authority of the director of education. It was another strange twist in Mackie’s academic life.

Despite this financial setback, Mackie continued to impress upon the Department of Education and the Public Service Board that the college was a tertiary institution responsible for the professional training of teachers, comparable to the professional schools of medicine, law, engineering, dentistry and pharmacy at the university. In a series of memoranda written between the late 1920s and mid-1930s, Mackie argued that staff at the college required special qualifications and working conditions. Underlining the views he expressed when he arrived in 1906, he stressed that college staff should be of high standing both scholastically and professionally. He sought to employ ‘the ablest and best qualified’ of the

79younger teachers. The college had been modelled on the teachers’ colleges developed from the late nineteenth century in England, Scotland and America, all of which had connections with universities. College staff therefore required qualifications beyond those necessary to teach in schools. Mackie argued that college lecturers should be given permanent positions on staff and should be considered for future appointments as inspectors of schools.237

A critical issue was the opportunity for leave – an integral part of academic life. Throughout the Empire, study leave had become crucial for university academics to undertake research and develop networks in their discipline. From 1895, the University of Sydney formalised leave arrangements, allowing professors ‘periodic leave’ for the two terms preceding or succeeding the long summer vacation.238 Terms of employment for teachers in public schools and lecturers at the college were increasingly regulated by the Public Service Board, which oversaw the ‘humble and obedient servants’ of the state.239 Mackie argued that academic staff in the college should have access to leave on full salary. There was continuing disagreement between Mackie and the Department of Public Instruction over this issue once Smith became director of education. By the 1920s, staff were no longer permitted to take study leave, despite the fact that it had been partially funded by a reduction in the salaries of those on leave.240

Mackie took up the cause again in 1936, arguing that it was vital for staff to take leave so they could become acquainted with developments overseas, particularly because the college was ‘so isolated by distance’. This call for travel was associated with Mackie’s insistence on ‘personal freedom’ for college staff in terms of their movements. In particular, Mackie objected to the Public Service Board’s requirement that staff sign an attendance book. He had never insisted on the number of hours staff spent at the college, especially in view of the fact that there were no individual staff rooms. Overall, of their thirty hours of official duties each week, no more than one-third was to be devoted to class teaching; the remainder was dedicated to preparation for teaching, individual tutorials and

80supervision in schools. As Cohen has suggested, ‘The business of a College lecturer is to guide the studies and the practice of young people preparing to teach’. Significantly, Mackie always encouraged college lecturers ‘to make contributions to the study of their subject … the stimulus to original thought is most valuable and greatly increases the lecturer’s efficiency as a stimulating teacher’.241

While supporting his staff, Mackie became increasingly concerned about the erosion of the professional standards of students at the college. With the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the numbers of college students who were able to attend university declined as a result of financial cuts imposed by the Department of Education. In his address to students leaving the college in 1934, Mackie strongly criticised this policy. He pointed out that the college had been placed within university grounds so that college students could enjoy the life of undergraduates, but in 1934 only two students were enrolled in the Faculty of Arts. Such a policy, he claimed, was ‘bad for students, for the Education Service, and for the State’. It was also detrimental to teaching as a profession.242