PART ONE

The young academic

2

Alexander Mackie was born on 25 May 1876 in the heart of Edinburgh. His family lived at 9 Dean Terrace, overlooking the Leith River. The residence was in the Georgian New Town, which had been built in the eighteenth century as part of the city’s urban improvement. Alexander’s father, William, was a ‘master grocer’ in Leith Road, a position that signified his status in Edinburgh’s commercial life.8

The son of a Presbyterian minister, William Mackie had grown up in a manse and attended the local parish school in the ‘dark stone’ town of Huntly, not far from Aberdeen in North-East Scotland. Forty years later, he retained his copy and workbooks from when he was a fourteen-year-old schoolboy. With practical knowledge drawn from his schooling, William had gone into commerce.9 His two sisters remained in Huntly, living in a cottage with two attic bedrooms, a fuel stove and no bathroom plumbing.10

Two years after Alexander’s birth, his mother, Margaret (nee Davidson), died giving birth to his sister, Maggie. According to his daughter, Margaret, Alexander’s mother’s family blamed his father for his mother’s death because, despite warnings, she had become pregnant for a second time. His father became depressed

4and almost a recluse. A devoted housekeeper, Elizabeth Murray, raised both children. Neither Alexander nor Maggie ever met their mother’s family.11

His mother’s early death and his father’s partial withdrawal from the household may have helped to shape young Alexander’s identity. As an adult, he would write to his father with a mixture of intimacy and formality, opening with ‘My dear Papa’ and closing with the endearment ‘yours affectionately’, but ending his letters with the formal signature ‘A. Mackie’. In his mid-teens, Alexander was already developing a sense of personal style. Maggie wrote to her father in 1892, when she was on holiday with her brother: ‘Alexander will be a great masher with his pot hat & stick up collar you will look quite little beside him.’12

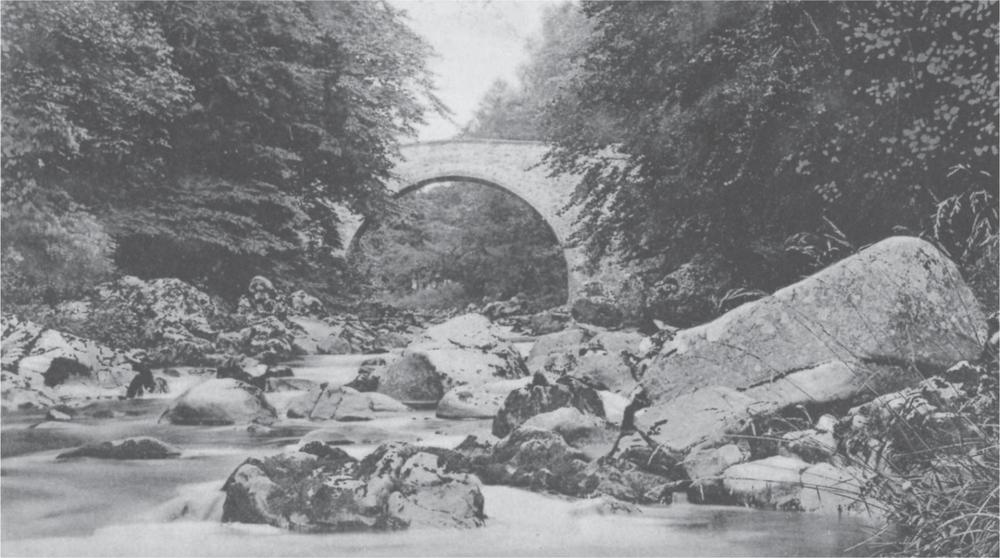

Alexander and Maggie spent holidays with their aunts in Huntly, where in ‘spring the scent of gorse from the laird’s estates drifted over the workers’ cottages’.13 The Mackie family had connections with a local wool mill, but Aunt Maggie and Aunt Jim (Jemina) lived a frugal life, committed to the traditional values of the local kirk. Alexander spent his days in Huntly cycling through the beechwood, fishing for trout in the local Bogie and Deveron rivers and going for long walks in the custom of his father. During a visit in 1899, he travelled to Aberdeen. He was impressed by the large number of churches in the city; they seemed ‘very conspicuous’ and clean with the ‘new appearance of the granite’. Equally outstanding was the library of King’s College at the University of Aberdeen.14

The city of Edinburgh

Despite his family’s history in North-East Scotland, Alexander’s principal upbringing was in Edinburgh – an urban setting experiencing social and educational change. The city is associated with the foundation of the Scottish nation and its monarchy. Edinburgh is a hybrid name drawn from an Anglian and Celtic past;

5‘edin’ implied ‘hill slope’, with Celtic antecedents, and ‘burgh’ was Anglo-Saxon for fort.

The royal burgh of Edinburgh was created in 1130. The union of the English and Scottish crowns in 1603, followed by parliamentary union in 1707, helped to place Edinburgh within a wider British culture. By the early nineteenth century, Edinburgh was a centre of literary culture and political and social reviews that influenced the British Empire, Europe and North America. Authors sought publishers in Edinburgh, which was increasingly recognised as a ‘city of the intellect’. While Glasgow’s wealth was mainly built on manufacturing and shipbuilding, Edinburgh was associated with ‘learned professions’ such as law and medicine. Of particular significance was the large, well-educated middle-class population in the city.15

Education differentiated Scotland from England, even after 1707. Scottish universities emphasised the role of professors as the primary authority in teaching; their approach was similar in many ways to German universities. At Oxford

6and Cambridge, tutors in residential colleges taught a curriculum based on the classics and mathematics. Most of the students were drawn from elite English public schools, where they had been educated in the formation of character. In contrast, Scottish schools and universities emphasised merit and intellect. Unlike pupils in the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, most students in Scotland did not reside at the universities. They attended classes during the day, listening to teachers and professors delivering lectures.

The University of Edinburgh was an important part of Scotland’s national educational profile. In 1582, King James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) had granted a royal charter to the Edinburgh town council sanctioning what was originally known as Tounis College. Edinburgh now had a university to match the three other Scottish universities established at St Andrews, Aberdeen and Glasgow in the medieval period.16 While these other universities were in decline, Edinburgh’s new institution prospered. Initially, students followed a four-year course in arts, focusing on the classics and philosophy. Many then proceeded to study divinity as a step to entering the Church. Most of the original teachers were ‘regents’, teaching all subjects in the curriculum. But increasingly, specialised professors were appointed to oversee the curriculum in arts, divinity, law and medicine.17

What had been a ‘prosperous Arts College, with a small but respected Divinity school attached to it, became in the middle of the eighteenth century one of the leading universities in Europe’.18 Edinburgh’s international reputation came principally from its medical school. A chair of medicine was established in 1685. By the 1720s, candidates for medical degrees were being examined in written tests, ensuring that appropriate standards were maintained. This approach would later be emulated throughout the university.19 Students now enrolled not just from Edinburgh and the Scottish ‘borderlands’ but also from England, Europe and even the Americas.

7Edinburgh was not only the leading European university in the field of medicine; its alumni also became pre-eminent in the Church and in fields such as law, teaching, science and literature. Given the size of the university, the achievements of its graduates compared favourably with Oxford and Cambridge.20

Democratic intellect and middle-class meritocracy

North-East Scotland, the ancestral home of the Mackies, was supposedly the birthplace of the ideal of the ‘democratic intellect’ in Scottish education. The Presbyterian Church in Scotland advocated education for all Scottish people. This helped to create the idea that the future of the nation lay in schools and universities – including those in remote rural parishes – identifying and supporting intellectual talent. In the North-East, these educational principles were embodied in parish schools and in a faith in the knowledge of university-educated schoolmasters. These traditions lasted into the nineteenth century. The North-East continued to have the highest proportion of its population attending university, compared with the rest of Scotland.21

Arising out of the Reformation, Scotland had developed a system of ‘public’ schools that embraced both parishes and local towns. By the late eighteenth century this ‘national’ system included about 900 parish schools and eighty to ninety burgh grammar schools, all maintained and supported by the Church of Scotland, in partnership with town councils and landowners.22 The spread of schools gave rise to the view that Scotland, unlike England, provided opportunities to almost all men – and even some women.

The foundations of Scottish education lay in the parish system, including both kirk and school. The ‘dominie’ or local school teacher, who was often educated in philosophy, held almost equal status to the minister of the church; both sought to educate their young flock in Christianity and provide knowledge of the world. Bright students, usually male – sometimes ‘lads o’ pairts’ from the rural peasantry – would be encouraged to go to the local burgh or grammar school,

8or straight to university, to extend their knowledge in areas such as philosophy. They could then make their way in the world, often as teachers or ministers of God’s word.23

An example of the progress of a talented Scottish student from the parishes to the metropolis was seen in the life of the nineteenth-century philosopher Thomas Carlyle. Coming from a devout family of farmers, he was sent from the local parish school to the nearby grammar school with the expectation that he would eventually enter the ministry. In 1809, at age thirteen, he walked to Edinburgh to become the classic impoverished student – living in lodges, sending his laundry home, eating oatmeal in the morning and trying to make sense of lectures delivered by his professors. Eventually, he abandoned his planned career in the Church to enter the literary and intellectual world, establishing his reputation as a man of letters.24

The ideal of the democratic intellect persisted throughout the nineteenth century. In 1834, Aberdeen Magazine published the following ‘Remarks on parochial education in Scotland’:

It is a system of which Scotland has just reason to be proud … Of silver and gold she has but ever possessed a trifling share; nor has nature bestowed on her the warmth of unclouded sun and rich products of luxuriant soil … yet her moral atmosphere has been generally serene and unclouded. While the benefits of knowledge in other countries have been, comparatively speaking, locked up from all those whose fortunes have not raised them above the lower or even middling ranks of life, the son of the most humble peasant in our native land has in his power to approach the fountain of learning and to drink unmolested from its pure and invigorating and enriching stream.25

It has been argued that even in North-East Scotland the democratic intellect was a cultural ‘myth’ that emerged as a literary tradition, rather than a reality of

9life for most children, who continued to leave school early to work on the land.26 Throughout the nineteenth century, the rural parish became less foundational in Scottish education. The population of Edinburgh grew fourfold, giving rise to a new urban middle class.27 In place of rural parishes sending poor boys to universities, urban centres became a focus, leading to institutional adaptation and a new relationship between schools and universities.

By the early nineteenth century, private secondary schools had emerged, often offering modern curricula, in contrast to the classical curriculum of the burgh schools. Edinburgh High School, founded in medieval Edinburgh, was still seen in 1825, on its 500th anniversary, as ‘open to boys of all ranks and circumstances’, proving the ‘use of a school in a free state’ for ‘talent, perseverance and industry’.28 With this claim, Edinburgh High School restated the values of a public school open to talented students from all social classes. In contrast, Edinburgh Academy, founded in 1824, offered a wider curriculum, while still including the classics, and promised higher academic standards leading on to university. Private shareholders owned the academy, which had higher fees than the high school. The academy was situated in the New Town, where many of the professional classes had relocated.29

Increasingly, secondary schools in Scotland were catering for the urban middle class, providing a way into the professions. As in England, even philanthropic bequests were reconstituted to serve such ends.30 A significant example in Edinburgh was the Merchant Company, which was created through royal charter in 1681 to protect its trading rights in the city. Over the next century and a half, the company administered trusts and bequests, many of which established ‘hospital schools’ for the poor and schools for girls. By the mid-nineteenth century, at least four of these impressive institutions could be seen from the banks of the River Leith. But many in the Merchant Company regarded these philanthropic institutions, which had relatively few residents, as no longer fit

10for purpose. Instead, the company decided to reform and transform them into institutions for the children of the middle class.31

In 1868, the Merchant Company designed a scheme to remove all the charity children and convert the four standing buildings into ‘great day schools’, admitting students by ‘merit in open examination’, and to establish bursaries and open scholarship.32 Many opposed this proposal on the grounds that it would deprive poor children of opportunities.33 Despite such reservations, legislation was passed by the British parliament. By 1871–72, four schools had been established – two for females and two for males – with names reflecting the original beneficiary or bequest: the Edinburgh Ladies College, George Watson’s Ladies College, George Watson’s College for Boys and Daniel Stewart’s College for Boys. Overall, 4,000 students enrolled in these institutions, reflecting the general demand in Edinburgh for schools that provided education based on the principle of establishing merit through examination.34 Some complained that these new schools were undercutting Edinburgh High School and Edinburgh Academy by setting their fees too low.

The 1880s marked a significant phase in the development of secondary schools in Scotland. Following the 1873 Act that established state funded elementary schools, the new government Department of Education turned its attention to creating credentials for attending and completing different levels of schooling. Among other changes, regulations established a ‘certificate of merit’ for students leaving elementary school and a ‘leaving certificate’ for those completing secondary school.35 The Merchant Company schools soon supplanted the older private schools and provided easier access to the University of Edinburgh. By 1880, more than thirty per cent of students entering the University of Edinburgh had attended one of the Merchant Company schools; within a decade this figure would be almost forty-five per cent.36

11Alexander Mackie’s father had attended the local parish school in Leith, but there were different expectations for his son. As newcomers to Edinburgh, the Mackies took advantage of the new social context and adapted to the urban environment in ways similar to other migrants from outside the city. In 1916, looking back on the new arrivals of the nineteenth century, the Edinburgh lawyer J.H.A. Macdonald – elevated to the bench as Lord Kingsburgh – reflected that ‘there was no city anywhere in which parents of the middle class can more easily obtain good school education at a very moderate outlay … Very many persons possessed of a fixed but not high income migrate to Edinburgh, because of teaching facilities which the schools of the city provide’. To Lord Kingsburgh, such persons ‘are the best citizens a town can have. They give stability to a community.’37

The Merchant Company schools would probably have appealed to William Mackie as a ‘master grocer’. Access to higher education was also an important consideration for Edinburgh’s middle-class families. In 1884, at the age of eight, Alexander entered Daniel Stewart’s College. Occupying a site on the western outskirts of Edinburgh, it was some distance from the centre of population but close to the Mackie home. Daniel Stewart’s was one of the four new or transformed secondary schools that could be viewed from the banks of the Leith – buildings described by a recent historian of Edinburgh as ‘sober or swaggering’.38 Alexander could easily walk the cobblestones alongside the Leith from his home to his new school.

Daniel Stewart’s for Boys was established in 1848. Initially, it had a technical bias to attract the working class, but it was soon charging fees comparable to its brother school, George Watson’s39 – George Watson’s offered a more academic curriculum for students bound for university. Along with other schools in the emerging private sector, Daniel Stewart’s had a ‘preparatory’ department that provided entrance to the full secondary school. From the 1870s, the school’s physical facilities were improved and much was made of the qualifications of the staff. Increasingly, the school focused on competitive exams designed to prepare students to enter university and, ultimately, to proceed to the professions.40 There was also attention

12to physical education and sport, including cricket. This reflected the emergence of English public school influences in Edinburgh through schools such as Glenalmond, which was founded by Episcopalians in 1847, and Fettes, which was also funded through the Merchant Company and opened in 1870.41

Daniel Stewart’s was ‘meritocratic’ in aim and purpose. In his first year, Alexander won a certificate of merit for proficiency in reading and writing. As he progressed through the school over the next six years, he was awarded certificates for attainments in subjects across the curriculum, including English, Latin, history, French, arithmetic, geometry and algebra, and Greek.42 Daniel Stewart’s was moving towards organising the school into age-based departments – primary for boys under twelve, intermediate for those over twelve who passed the ‘qualifying’ exam and were preparing to complete the state Intermediate Certificate at age sixteen, and post-intermediate for those preparing for university.43

Alexander left Daniel Stewart’s in 1890. In 1951, he told a gathering at Sydney Teachers’ College that by age sixteen the ‘selection of a job was becoming important. Medicine, law, business were considered by my father but rejected. At the time I had no definite interest.’44 Meeting a school friend in the street, Alexander learned that friend was intending to take the state pupil teacher examination. Alexander decided to join him. According to Alexander’s daughter, Margaret, ‘one of them, they never knew which, was top in this test, the other second’.45 Alexander and his friend had, in effect, embarked on a journey towards teaching careers in a new climate of professionalisation.

Teaching as a profession

Historian Harold Perkin has suggested that nineteenth-century Britain was shaped by contrasting ideals: the ‘entrepreneurial’, associated with men of business such

13as Alexander’s father, and the ‘professional’, attached to ideas of merit that were increasingly associated with credentials gained through university education – the path on which Alexander was embarking.46 Scotland had long celebrated the talents and expertise of professionals. Robert Louis Stevenson, born in Edinburgh in 1850, came from an extended line of lighthouse engineers. His passion lay with literary pursuits, leading his father to comment that literature was ‘no profession’ but that his son ‘might be called to the Bar if [he] chose’.47 Stevenson studied law and considered an academic career, even while his fictions of adventure and travel were becoming known throughout the world.

14Born in 1850, a generation before Alexander Mackie, Stevenson’s sympathies lay with the ‘old’ University of Edinburgh, where ‘all classes rub shoulders on the greasy benches. The raffish young gentleman in gloves must measure his scholarship with the plain clownish laddie from the parish school.’48 For Stevenson, the ‘old university’ had disappeared by the late nineteenth century: ‘the most lamentable change is the absence of a certain lean, ugly, idle, unpopular student whose presence was for me the gist and heart of the whole matter.’49 Progressively, universities in Scotland were focusing more on preparing students for the professions. This was the world Alexander Mackie came to know.

The middle-class ideal of professionalisation had specific effects on teachers and teaching in Scotland. The parish ‘dominie’ had long held a position of influence, particularly in rural areas. Through their connection with the Presbyterian Church, they had some official status. But they also had independence and the security of tenure. Some parish schoolmasters attended university, though few completed formal degrees.50 Just as urbanisation and industrialisation helped to transform schooling in Scotland, the traditional idea of the teacher was also reshaped in the nineteenth century. Teaching was increasingly viewed as a profession based on extended education.

The professionalisation of teaching took place over almost a century. Initially, Scotland undertook local and school-based experiments to find new ways to teach large numbers of children. The clergyman Andrew Bell was partially responsible for introducing the ‘monitorial system’ in 1812, whereby older children acted as monitors, helping to teach younger pupils. The idea was introduced at Edinburgh High School by its rector, leading to a class of 250 students instructed by monitors.51 The monitorial system led to ‘model schools’ or ‘normal schools’, which were designed to offer examples of how to teach, often experimenting with new methods of teaching. By 1826, a sessional or ‘normal’ school had been established in

15Edinburgh under the auspices of the Presbyterian Church. This school brought together teachers from across Scotland for further education and training.52

The constitutional union of England and Scotland in the eighteenth century imposed uniformity. Gradually, the London-based administration used the power of the purse to enforce a new system of teacher training. From 1833, throughout the United Kingdom, state grants were provided to Church elementary schools. By 1846, a system of ‘pupil teachers’ was instituted, whereby young men and women were apprenticed to teachers. These pupil teachers studied under and assisted supervising teachers in their classrooms. Some were then awarded scholarships to attend teachers’ colleges to extend their general education and their knowledge of teaching. There was an increasing emphasis on recruiting pupil teachers directly from the new elementary schools from the age of thirteen, under five-year apprenticeships.

This new system emerged just as the ‘great disruption’ of 1843 split the Presbyterian Church. A large section of the Church, led by Thomas Chalmers, professor of theology at the University of Edinburgh, objected to the power exercised by local gentry in lay patronage of the ‘presentation’ of ministers. About 470 ministers and one-third of the laity left the Presbyterian Church to found a new Free Church. Part of this new church’s mission was to build churches, schools and colleges. The disruption helped to double the number of teacher training colleges. Moray House in Edinburgh, a Free Church college closely associated with the University of Edinburgh, was founded in 1848.53

The new system of apprenticeships followed by training at teachers’ colleges raised issues about professional standing and status. In 1848, the Educational Institute of Scotland was formed in Edinburgh, representing the professional interests of burgh and parish school teachers. The institute’s aims were to defend the traditional system of Scottish education based on parish dominies and to advance teaching as a profession.54 Among the institute’s supporters was Simon Laurie, then secretary of the Church of Scotland Education Committee. He proposed that prospective teachers should first attend secondary burgh schools,

16rather than ‘normal schools’ (which soon became teachers’ training colleges). ‘“Why,” he asked, “set down Normal Schools in low localities and assemble together an innumerable number of ill-trained unmannerly children and educate our future teachers on the same forms as these children?”’ It was far better, he suggested, for prospective teachers to mix with the middle class in secondary schools, where they would acquire ‘the manners and habits of gentlemen’.55

An administrator and author, in the mid- to late nineteenth century Laurie was Scotland’s best known ‘educationalist’; he was recognised throughout Britain and the Empire, and even in America. Born in Edinburgh in 1829, Laurie was the son of the chaplain to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and the grandson (on his mother’s side) of a Presbyterian minister. He attended Edinburgh High School and then Edinburgh University, graduating in 1849. After five years as a private tutor, he became the secretary to the Education Committee of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, a post he held for half a century. From this position of authority he helped to shape educational activities in Scotland. Laurie reported to the Argyll Commission on schools in the 1860s and was then an adviser to the Merchant Company, advocating the reorganisation of the hospital schools, including Daniel Stewart’s. He also became an examiner and visitor for the substantial Dick Bequest, set up to supplement the salaries of teachers in North-East Scotland and help them to attend university.56

With his background at Edinburgh High School and the University of Edinburgh, Laurie was committed to ensuring future teachers continued to be exposed to a liberal education that included philosophy and the humanities. In 1868, he applied unsuccessfully for the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Edinburgh.57 In 1876 (the year of Alexander Mackie’s birth), he was appointed Bell professor of education at Edinburgh. A similar appointment was also made at St Andrews, making Scottish universities the first in the British Isles to found chairs of education. Formally, Laurie’s chair was established in the conjoint fields of the theory, history and art of education. In his inaugural professorial address, Laurie sought to define the place of education in the university. He paid particular

17attention to the success of training colleges over the previous thirty years, but went on to describe universities as the sites for education; ‘a specialist Training College does not answer the same purposes as a University. The broader culture, the freer air, the higher aims of the latter give to it an educational influence which specialist colleges can never exercise.’58

Laurie saw two overlapping scenarios for the future of teacher education. First, he proposed that universities should become the ‘trainers of all aspirants to the teaching profession who are fitted by their previous education to enter on a University curriculum’, holding out the possibility of a Faculty of Education similar to departments devoted to professions such as engineering.59 Second, he suggested that education should be accepted as a subject discipline within universities – a step that had been partially achieved by the establishment of the chair he held. However, he still faced claims that teacher education was too focused on practice rather than theory.60 These twin scenarios would remain influential in future programs of teacher education, not only in Scotland but throughout Britain and the Empire. And they would have a specific impact on Alexander Mackie’s professional education.

Laurie’s attempts to find a place for the study of education in universities faced a number of difficulties. Although St Andrews appointed a Bell professor of education in 1876 – John Meiklejohn – the university did little to support this chair. The Universities of Aberdeen and Glasgow did not make any such appointments until the early twentieth century. At the University of Edinburgh, Laurie found little support for any program of educational studies until 1880, when the university introduced a ‘Literate of Arts’ that included education as an optional course. In 1886, Laurie persuaded the University of Edinburgh to establish a postgraduate diploma, the ‘Schoolmaster’s Diploma’, taken at a general level by those with a pass degree or as a diploma by honours graduates seeking careers in secondary school teaching.61

18The introduction of education into the curriculum of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Edinburgh was part of an ongoing review of Scottish universities in the nineteenth century, focusing on the arts curriculum and the tradition of a general degree with philosophy at its core. A series of royal commissions were established in 1826, 1858 and 1876. Some saw these commissions as an effort to ‘Anglicise’ Scottish education by introducing more specialist studies in areas such as classics to replace the general university curriculum. There were also fears that Scotland’s democratic tradition in education would be undermined by proposals to raise university entry standards and thereby exclude poor boys from parish schools. At the same time, there were limited moves to introduce ‘honours’ schools for further specialisation – these schools challenged the general curriculum, which focused on philosophy.62

Recent research suggests that this was not so much a process of Anglicising Scottish universities as part of a transformation of universities and higher education that spread throughout the British Empire during the nineteenth century. While the specialties of classics and mathematics maintained their status at Oxford and Cambridge, elsewhere middle-class meritocracy, professionalisation and local community interests helped to shape the university curricula. Scottish universities, which were increasingly grounded in principles of merit and professional training, influenced the curriculum of the University of London and many of the civic universities in England, as well as many of the degree-granting institutions established in the Empire from the mid-nineteenth century.63 Thus, Scottish examples as much as English influences helped to shape universities in metropolitan centres throughout the Empire. This was the beginning of a form of transnationalism that would soon influence the development of education as an academic discipline.

The increasingly professional orientation and purpose of Scotland’s universities aided the introduction of education as a foundational discipline for the teaching profession. In the Act of 1889, the new Universities Commission included education as a full qualifying subject for the Master of Arts (MA) degree

19at all four Scottish universities. This paved the way for professorial and lecturer appointments. It now seemed that Scotland’s universities would play a prominent role in training teachers.

Scotland’s university system provided an example for universities elsewhere in Britain. In teacher training, Scotland was moving away from the pupil teacher system introduced from England to embrace a model based on college and university education. Most teacher training in England was still based on the pupil teacher system, in association with training colleges, which were usually residential institutions controlled by the churches. From 1890, state grants were provided for the education and training of teachers in day training colleges, which would soon be absorbed into universities as Departments of Education. But it was not until the eve of World War One that the academic discipline of education became a significant part of universities in England and Wales.64

Laurie retired from his chair in 1903. He had not achieved everything he had expected when he was appointed professor almost thirty years before. But through his work for the government and the Church, and then in the university, he had become one of the most influential educators in Britain. His participation in government enquiries was matched by an extensive list of publications, principally on the history of education, although he also wrote about the philosophy of education. Laurie’s most important book was his 1881 study of the Renaissance scholar Comenius, which bolstered his reputation across the Atlantic, including at the teachers’ college attached to Columbia University in New York.65 Laurie laid the basis for the academic study of education leading to publication (even if not based on research), providing an example for future academics focusing on education as a discipline involving theory and practice.

Simon Laurie was Alexander Mackie’s first significant mentor and supervisor at the University of Edinburgh. Later, Laurie was a referee for Mackie’s applications for academic positions, including the role of principal of Sydney Teachers’ College. When Mackie was appointed to the principalship in Sydney, he remained in

20contact with Laurie.66 A follower of the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher David Hume, Laurie believed in ‘common sense’ based on reason and the need to dispute all matters. This was Mackie’s first encounter with academic philosophy.

Becoming a teacher

Alexander Mackie was part of the changing world of teacher education in late nineteenth-century Scotland. Once a predominantly male profession, teaching in Scotland became more feminised in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Males comprised sixty-five per cent of Scottish teachers in 1851 but only thirty per cent in 1911.67 Much of this shift was due to the 1873 Act that created state funded schools under school boards. The demand for teachers in urban elementary schools brought forth a teaching force with varied backgrounds and qualifications. The male dominie of the rural parish was increasingly supplanted by the mainly female urban elementary school teacher. The increasing demand for teachers was met through a complex system of certification that led to low pay for women. Many males now sought opportunities in commerce or the civil service. But there were still inducements for young men who entered teaching, such as scholarships and remuneration during training and the prospect of a career in teaching, particularly in secondary schools.68

The changing hierarchy in teacher education opened up new opportunities for middle-class males such as Alexander Mackie. Alexander entered the world of teaching at a significant moment in the history of Scottish education. His training began with a role as a pupil teacher. In 1893, his father signed an agreement with the Edinburgh School Board allowing Alexander to become a pupil teacher for three years. Alexander received a payment of £17.10s.00d for his first year and up to five hours instruction each week to prepare to qualify to enter a training college. He was allotted to a teacher at the elementary school in the village of Canonmills, which lay in a low hollow north of Edinburgh’s New Town,

21near the Mackie family residence.69 As Alexander told his daughter years later, as a sixteen-year-old pupil teacher in a gallery classroom of ninety students, he doubted that the children learned much. The experience led him to oppose both gallery classrooms and pupil teaching.70

After Canonmills, Alexander went on to Moray House teachers’ college, where the rector praised his teaching; not only did Alexander have a command of the theory of education, he received the mark of ‘excellent’ for his ‘practical work’ – the ‘highest in our power to give’.71 Alexander soon became part of a new bursary scheme instituted in 1895, known as ‘Queen’s Studentships’, which allowed candidates to receive professional training and undertake academic studies at university (similar to scholarships already existing in England). These new studentships were intended principally for secondary school teachers and were particularly attractive to males, many of whom were undertaking concurrent studies at Moray House and the University of Edinburgh.72

Prospective teachers now occupied a prominent place in the university, as did women, who had been allowed to undertake degrees since 1892. In contrast to the 1860s, when students as young as fourteen could come to university, students were now required to complete a university entrance exam, which was normally undertaken after a prolonged period at secondary school. And there were opportunities for honours degrees in fields of specialisation.73

Late nineteenth-century reforms to teacher training had created the prospect of a more diverse teaching force that built upon but went beyond the old ideal of the dominie in the rural parish school. Some still had the background of a ‘lad o’ pairts’ who had been given an opportunity to become a teacher. Among those who qualified as teachers around the same time as Alexander Mackie was William Campbell. Born in 1867, Campbell was a poor boy from the Highlands

22who had succeeded, through his own merits and determination, in becoming a pupil teacher, before attending Moray House on a scholarship. A teacher by 1893, Campbell later married and became committed to family, school and local community.74 Support for the democratic intellect among students from rural parishes was thus retained – although they had to conform to new regulations and examinations in preparing to teach.

In the four years between 1896 and 1900, Alexander Mackie completed a series of qualifications and studies. While still a pupil teacher, he undertook certificates in drawing and electricity. He continued to study fields of science under the British Department of Science and Art between 1898 and 1899, while undertaking courses at Moray House. Alexander commenced his studies at the University of Edinburgh in 1896, when he passed the preliminary exam for graduation in arts

23and science, completing courses in Greek, Latin, mathematics and English. He began the ordinary degree for the MA in 1897, but soon transferred to honours. From 1898 to 1900, he undertook honours courses, studying the history of education with Laurie and working with general philosophers.75

The academic world

In Britain, by the end of the nineteenth century, there was an emerging view of academics not just as teachers but as ‘intellectuals’ focused on ideas for social and political change.76 At Oxford and Cambridge, the transformation of college tutors from clergymen in holy orders to secular ‘dons’ was associated with a new world of academic enquiry, critical scholarship and publication based on research. As one of the leading proponents of change, the Oxford scholar Mark Pattinson saw the ‘academic vocation’ as a ‘calling to the lifelong task of mental cultivation for its own sake’.77 Harold Perkin has suggested that this was not so much a new vocation as the emergence of academics as the key profession preparing and educating students for entry into other professions. Increasingly, education and training for the various professions became integrated into universities, which imparted both skills and values. More generally, there were new values in university life; teaching and research held promises of services to the community and hopes of action for social change.78

Much of this reconceptualisation of academia was due to Scottish examples. In Scotland, the eighteenth-century Enlightenment helped to foster a new view of academics as creators of novel disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. For instance, economics was pioneered by Adam Smith and his colleagues. Academics and graduates from Edinburgh helped to found University College London, with professors appointed in medicine, law, political economy, logic, philosophy, modern languages, science and engineering. Edinburgh’s medical school

24was emulated throughout Britain and the Empire – an indication that academic study was a prelude to professional practice.79

Transnational models of reform also emerged. Visions of the modern university often focused on German examples. What became known as the ‘Humboldtian model’ of reform was part of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment in Germany and took clearer shape in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat of Prussia in 1807. The aristocrat Wilhelm von Humboldt played a decisive role in the foundation of the University of Berlin in 1810. Humboldt and the philosopher Fichte saw university reform as a way of rousing the German nation. They looked to a new spirit of neo-humanism and character formation – bildung – to ‘inoculat[e] the Germans with the Greek spirit’. According to R.D. Anderson, Humboldt suggested a new image of universities that promoted ‘the unity of teaching and research’. Teachers had to be researchers; the search for truth and understanding, rather than professional training, was the primary purpose of universities. In the area of philosophy, ‘the university teacher is no longer a teacher, the student no longer a learner, but the latter carries out research himself, and the professor directs and supports his researches’.80 Following the unification of Germany under Prussia in 1870, research was more clearly defined as state-supported science, encompassing both the investigation of phenomena and the application of results. The physical and social sciences were embraced.

For most of the nineteenth century, German thinking and values held sway in the field of philosophy throughout much of Europe. The four Scottish universities had long histories of association with European philosophy. The Scottish Enlightenment had encouraged toleration and ‘liberty’ in philosophical debate and discussion in universities and in the Presbyterian Church. Scottish universities developed longstanding relationships with Germany through the discipline of philosophy and the work of moral philosophers such as Kant, Fichte and Hegel. This association with German thought was first seen in traditional disciplines, but also had a major effect on the emerging discipline of education.81

25The German Enlightenment placed emphasis on education as a form of self-realisation. Born in 1776, the German philosopher Johann Friedrich Herbart published his Science of education in 1806. Herbart proclaimed that ‘the one and whole work’ of education was ‘Morality’, which was found in individual ‘will’ generated from desires.82 Desires were regarded as conditions of ideas. This view had implications for teaching. The teacher was required to stimulate and incite interest so that pupils were open to new ideas. To do this, Herbart proposed five stages for developing a lesson in a class: preparation, presentation, association, generalisation and application.83 The Herbartian method was regarded as one of the major contributions of German philosophy and applied science to the understanding of teaching methods.

Many students and scholars travelled to the University of Jena, which became known as the German centre for educational research. Founded in the sixteenth century, Jena was closely associated with the major figures of the German Enlightenment, including Goethe, who had taken a strong interest in the university, Schiller, who was given a chair in history, and Fichte and Hegel, who had taught there. By the late nineteenth century, it was a globally acclaimed centre for applied scientific research in the field of education, attracting scholars and postgraduate students from America, Britain and Europe.84

Some British students came to Germany to extend their knowledge and develop a foundation for careers in the Empire. Born in Scotland, John Smyth had begun his teaching career in Londonderry, Ireland, before migrating to New Zealand in 1881 to take up a teaching position in Invercargill. By 1891, he held a Bachelor of Arts (BA) from the University of Otago; he graduated with an MA the following year. In 1895, he left New Zealand to study at the University of Heidelberg. Upon returning to New Zealand, he became a lecturer in mental science at Otago University. In 1898, he travelled to Edinburgh to complete a PhD in philosophy and formal studies in education and economics. From 1899 to 1900, he studied at Jena and Leipzig. He then returned to New Zealand to become inspector of schools at Wanganui. During a visit to Melbourne, Smyth

26impressed Frank Tate, the future director of education in Victoria, with his views on technical education. In 1902, Smyth was offered the position of principal of Melbourne Teachers’ College and a lectureship at the University of Melbourne.85

The emerging discipline of education was also shaped by wider intellectual developments. Influenced by German philosophy, the intellectual movement known as philosophic idealism became prominent in British universities from the 1850s. Particularly significant in this movement were the Oxford don T.H. Green and other young, Oxford-educated liberals of moral conscience.86 These idealists sought an ‘organic whole’, where communities of like-minded moral individuals came together for collective action. Such idealism went beyond individualism to embrace the view of the ethical state as central to restoring the sense of belonging to a community.87 Philosophic idealism was not only shaped by transnational influences; it was an international movement giving a moral purpose to academic life.

Support for the role of the state in the provision of education was central to moral and political action among idealists. They aimed to extend opportunities and positive freedoms to all citizens. Before his early death in 1882, T.H. Green worked to develop elementary and secondary education to help create a national school system.88 As in other areas of social life, Green preferred the voluntary principle in organising schools. But he accepted that only state action in education could lead to equality and justice and support principles of citizenship. Almost emulating the old Scottish ideal of democratic intellect, Green advocated a state system of education that would provide a ‘ladder of learning’ that students from humble homes could climb to attend university.89

A decade after Green’s death, Oxford philosophers attempted to develop a theory of education that applied to the state by studying the classical scholar Plato. In 1897, the Oxford scholar R.L. Nettleship published The theory of education in the Republic of Plato, which provided an accessible account of Plato, stimulating

27further research and publications. Commitment to Platonic ideals became more common, though this did not so much advance the idea of education and democracy as strengthen Plato’s assertion that government must focus on training elite ‘guardians’ to protect society and its aristocratic and intellectual values.90

Philosophic idealism spread from Oxford. By the late nineteenth century, idealism was becoming pre-eminent in Scottish academic circles. One of T.H. Green’s close associates was Scots-born Edward Caird, a Christian idealist who became professor of philosophy at the University of Glasgow in 1866, before returning to Oxford as master of Balliol College in 1893.91 In 1879, a number of Caird’s students formed The Witenagemote, a discussion group similar to The Old Morality of the 1850s, of which Green and Caird were members at Oxford. Within the next few decades, at least twelve members of The Witenagemote were appointed to chairs in Britain and the Empire. Among the group’s members were Mungo MacCallum and Francis Anderson, both at the University of Sydney, and Andrew Pringle-Pattison, who became the main supervisor of Mackie’s studies in philosophy at the University of Edinburgh.92

Andrew Pringle-Pattison (who changed his family name from Seth) and his brother James Seth were important figures in Scottish idealism from the 1870s. Sons of a bank clerk, they had excelled at school – Andrew at Edinburgh High School and James at George Watson’s. They both went on to study philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. Andrew then studied in Germany, co-operating on academic studies with the future Scottish liberal idealist politician R.B. Haldane. After positions at St Andrews and Cardiff, he returned to Edinburgh as professor of logic and metaphysics in 1891. In his early years, he was a Hegelian. But he came to reject the absolute idealism of Hegel, returning to Kant’s views, which located self-consciousness in the individual. By the 1890s, he was one of the best known Scottish philosophers in Britain and the United States, presenting a case for ‘rational theism’ and proposing ‘personal idealism’ founded on

28Christianity. Recent scholarship suggests that he was one of the most significant idealists in Scotland in the late nineteenth century.93

After early studies in philosophy, James Seth undertook a divinity degree and also spent a period in Germany. In 1886, he went to Dalhousie College in Nova Scotia, Canada, to teach ethics. He moved to Brown University in 1892 and then to Cornell in 1896. In 1898, he returned to Edinburgh to take up the chair of moral philosophy.94 Andrew Pringle-Pattison’s and James Seth’s careers demonstrate the transnational and transatlantic movements of Scottish academics in the late nineteenth century. The fact that both Pringle-Pattison and Seth returned to Edinburgh reinforces the university’s international standing in the field of philosophy.

Studying at Edinburgh University

After studying the theory of education with Professor Simon Laurie, Alexander Mackie spent the latter part of his undergraduate degree under the supervision of Pringle-Pattison and Seth. The brothers encouraged him to pursue further studies in philosophy; Pringle-Pattison even suggested that Alexander consider studying in Germany. He also recommended books to Alexander, including Essentials of logic, which the prominent British neo-idealist Bernard Bosanquet had published in 1895.95 Pringle-Pattison engaged Alexander as a tutor in his class on logic and metaphysics, and advised Alexander on his prospects of gaining a university fellowship or scholarship.96

Alexander’s own views were revealed in an honours essay on Plato – who was regarded as the father of idealism in the ancient world. Significantly, Alexander took a different position from Oxford scholars such as R.L. Nettleship. Alexander made no reference to ‘guardians’ protecting moral and social values. Instead, he argued that there was unity between the individual and the state in ancient Greece.

29In modern society, he believed Christianity emphasised the ‘supreme value of the individual’ – a view that was consistent with the Christian idealism of Green, Caird and Pringle-Pattison. What was needed, Alexander proposed, was a new approach that would emphasise balance and harmony, in the spirit of Plato’s philosophy; this would be realised by improving the classroom environment and including school concerts and opportunities for appreciating art, while remembering that the social environment was just as important as the physical. Above all, Alexander argued in his essay, it was essential to remember that education was not the ability to pass ‘codes’ of attainment. Rather, its aim was ‘the formation of a national type of mind’ – ‘it is a mind not subjects that has to be taught’.97 Alexander’s interpretation of Plato accepted Pringle-Pattison’s views, while displaying a commitment to Laurie’s emphasis on liberalism and the individual student.

In a related essay, Alexander argued that ‘education is more spiritual than manual’. This shows notions of self-realisation through idealism. He contended that ‘we have to train a mind in a body’ and so the ‘definite formulation of an ideal of education is more important than the formulation of teaching’; unless the teacher is ‘striving after an ideal, his ideal for the children will be ineffective’. While the ancient Athenian ideal focused on gymnastics and music and the harmony of the soul, the Roman ideal was ‘practical’ and the Renaissance ideal was ‘cultural’, the modern ‘true ideal’ had to be ‘ethical’. Alexander believed that man’s true end is his realisation of a certain type of self: the ideal of ‘formation of high moral character’, with education of the intellect and the body producing a ‘self-governing being’ able to stand against the world.98

As a student of both philosophy and education, Alexander was deeply embedded in an individualised form of idealism during his years at the University of Edinburgh. His views on philosophic idealism were being shaped at a time when there was emerging interest in teaching methodologies. Much of this interest was focused on efforts to compare the intellectual discipline of education to the methodology of science. In 1878, Alexander Bain, professor of logic at the University of Aberdeen, published Education as a science – an ambitious effort

30involving the study of physiology, psychology, moral education, values and the methodologies of teaching different subjects.99

Alexander took the advice of his university supervisors and undertook basic studies in psychology, concentrating on the importance of attention in children. He wrote a paper for his supervisors on ‘The science method’ with reference to the psychology of attention. In this paper, he suggested that the study of psychology assisted teachers in a number of ways. First, it provided ‘rational insight’ into the rules of method. Second, it enabled judgement of traditional or empirical rules to accept or reject as they conformed to the ‘great generalisations of the science of mind’. Third, it gave the power to judge new methods. Overall, the teacher had to know the child’s mind and child psychology. The mind was a ‘self-developing activity’ and training the habit of attention was one of the most valuable effects of attention. The training of attention was also ‘a moral training’. For the teacher, this meant graduating lessons so that slightly greater effort was required in each lesson. The teacher should strive to arouse ‘expectant attention’. In keeping with Herbart’s ideas, Alexander emphasised that teachers must ensure a close connection between gaining students’ ‘attention’ and their ‘interest’ in a subject. Such interest is used by students to please their parents and teachers.100

Seven years after he began as a pupil teacher, Alexander graduated with an MA from the University of Edinburgh in 1900. As his chief supervisor during his final years at the university, Professor Pringle-Pattison later provided an assessment of Alexander’s attainments and standing in the field of philosophy:

Mr Mackie had a distinguished record as a student of Philosophy in this University. He attended the advanced classes in the subject during Session 1899–1900, and gained the Bruce of Grangehill and Falkland Prize, the highest honour to undergraduates. In April, 1900, he graduated with First Class Honours, his papers being both full and accurate, and altogether of a high standard. For two sessions he acted as one of my class-tutors, and

31in that capacity had to read and report upon a section of the class essays. He performed this work with ability and judgement.101

Aside from the honours Pringle-Pattison outlined, in his studies at Moray House and the University of Edinburgh Alexander gained a first class certificate in education, first class honours and the medal in both metaphysics and moral philosophy, and the medal and the Merchant Company Prize in political economy.102

Alexander maintained his interest in philosophy while gaining teaching experience. After graduating, he taught in schools for two years while continuing to work at the University of Edinburgh as a tutor for Pringle-Pattison. He spent a brief period at Berwick High School, where he was mainly involved in instructing students in English and mathematics in preparation for the Leaving Certificate examination. The Edinburgh School Board then appointed him to Broughton Public School in July 1900.103 Within a few years, his contacts and academic networks opened up the prospect of an academic career.

Becoming an academic

The slow expansion of Britain’s university system created opportunities in academia. Throughout the nineteenth century, a market had emerged for academics with the knowledge and skills to educate teachers. From the mid-nineteenth century, English ‘civic universities’, such as Manchester, Nottingham and Leeds, and the University of Wales had provided evening classes for teachers, accessing a new base for enrolments. By the 1890s, Oxford and Cambridge were providing forms of teacher training for male and female undergraduates who wanted to teach in secondary schools.104 Day training colleges also emerged. Attached to universities, they offered courses based on notions of liberal academic training. By 1900, day training colleges were providing almost one-quarter of the places available for the education and training of teachers. Day training colleges soon

32became akin to university departments, offering academic courses in education. The discipline of education was principally founded on the philosophy and history of education, but it increasingly embraced psychology as the basis for ‘scientific’ pedagogy.105

These developments integrated Scottish initiatives into the wider world of education studies and established a sub-profession for education academics. This created opportunities for a new generation of scholars in the emerging discipline of education, although traditional disciplines such as philosophy provided the foundation for new professorial appointments in day training departments.106 Many of the professors in education came from Oxford and Cambridge, which continued to dominate the staffing of the civic universities until well into the twentieth century.107 However, unlike many Oxbridge graduates, Edinburgh graduates in education, such as Alexander, had the advantage of experience in schools and training and studies at college and university.

By 1900, the number of academics in Britain remained small – less than 2,000, nearly half of whom were at Oxford and Cambridge.108 Progress in the academic world depended not only on ‘merit’ but on networks of influence within and across university systems. Established academics supported their postgraduate students as a way of extending their own influence.

In 1903, Alexander was appointed assistant lecturer in education at the University of Wales Bangor. He succeeded another Edinburgh graduate, Alexander Darroch, who had been appointed to the Bell chair of education at Edinburgh following Simon Laurie’s retirement. A former pupil teacher, Darroch was a decade older than Alexander Mackie but had followed a similar trajectory at the University of Edinburgh, completing an MA with honours in philosophy. Darroch was part of a new generation of Scottish scholars who moved away from the influences of German philosophy to embrace education as a discipline that provided an understanding of the social role of schools, much in the way of the

33American John Dewey. Alexander soon developed a close friendship with Darroch, who became one of his referees as well as an intellectual influence.109

His supervisors at Edinburgh, Pringle-Pattison and Seth, congratulated Alexander on being appointed to the position at Bangor over men from Oxford and Cambridge.110 Bangor was a college of the University of Wales, which had been founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university (similar to the University of London), where colleges were responsible for teaching while the central university was in charge of examinations. A chair of education had been established at Bangor in 1894, a year before England’s first education chair was created at Newcastle. The education of teachers in Wales was hindered by disputes between the established Church of England and the Welsh population due to the predominance of religious nonconformity. But there was increasing attachment to the colleges in Wales; these institutions sought to provide a foundation for emerging Welsh nationalism and support the aspirations of the Welsh people. Sir Henry Lewis, a Welsh businessman and a sponsor of the Bangor college, saw the advantages of a ‘normal’ college where future teachers would have the ‘inspiring influence of a University College before them every day’.111

His new appointment created opportunities for Alexander. He gave lectures on the theory and practice of education, conducted criticism lessons and supervised school practice. J.A. Green was the head of the education department and professor of education at Bangor from 1900 to 1906. After he was appointed professor of education at Sheffield in 1906, Green became the first editor of the Journal of Experimental Pedagogy.112 At Bangor, Green came to rely on Alexander, even appointing Alexander mentor of the male students while he was in Germany. Alexander’s status as a philosopher was reinforced following his election to the Hamilton Fellowship in Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh in 1903. He then became an assistant to James Gibson, professor of logic and philosophy at

34Bangor. Overall, Alexander’s years at Bangor provided him with new academic supporters in his work as a teacher of method and in the field of philosophy.113

On the basis of his experience at Bangor, in early 1905 Alexander applied for the position of master of method in the day training college at the University of Bristol. He used eleven referees from his time at Edinburgh and Bangor. All gave him strong support. H.R. Reichel, principal at Bangor and fellow of All Souls at Oxford, commented:

35

Mr Mackie came to us three years ago with a brilliant reputation, and his work ever since has more than justified his appointment. He is an excellent teacher, a firm disciplinarian, with considerable organizing capacity and plenty of tact and good sense. Personally he is a cultivated gentleman of high principles and broad sympathies and most pleasant in all personal intercourse.114

This reference was written on 26 January 1905, the day that later became ‘Australia Day’ – perhaps a portent of where Alexander’s academic future lay. He did not get the position at Bristol.

Networks of Empire

Middle-class Scots were major settlers across the Empire, in India, Canada, South Africa and Australasia. This was partly due to the general diaspora of Scottish university graduates. Graduates from Scottish universities in the late nineteenth century have been described as more cosmopolitan than their predecessors. Catriona Macdonald has suggested that, in the wake of curriculum reforms following the enactment of the 1889 Act, graduates ‘considered themselves part of a worldwide community of scholars and more apt to take action in pursuit of international understanding’.115 Scots had long sought opportunities abroad, serving in the army and civil administration, and the expansion of the Scottish universities in the nineteenth century saw many graduates heading overseas. In 1933, an analysis of 19,501 graduates from the University of Edinburgh found that more than half were living in Scotland, more than one-quarter in the rest of Britain and over one-sixth overseas, mainly in the Empire.116

In her seminal study, Empire of scholars, Tamson Pietsch has outlined the personal contacts and networks that shaped the ‘British academic world’ from the mid-nineteenth century. From the 1880s, universities in Britain and

36the dominions of settlement were linked through scholarships, exchanges and appointments. A culture of research in the humanities and sciences and an emerging culture of professionalism based on universities spread throughout the Empire.117 The careers of Scottish academics in the Empire show that developments in the sciences and humanities often ran parallel to efforts to advance professional education. The most prominent example of professional education founded on scientific research was in the discipline of medicine. Edinburgh’s medical school was closely associated with a number of universities and schools in the Empire. One of the most significant was the medical school at the University of Sydney. The University of Sydney, founded in 1850, originally centred on studies in classics, mathematics and science. But by the 1880s, it had a medical faculty, overwhelmingly staffed by graduates from Edinburgh.

Education as a discipline and teaching as a profession developed via many networks. But none were more influential than the neo-idealists, particularly the students of Edward Caird. Francis Anderson was an assistant to Caird at Glasgow in the 1880s. A former pupil teacher, Anderson was determined to improve the status and standing of teachers. But he was also attracted to theology. At the age of twenty-eight, Anderson migrated to Australia to become an assistant to Charles Strong, who had broken away from the Presbyterian Church to found the Australian Church. Strong emphasised the ‘social gospel’ of Christianity, promoting a social liberalism that embraced humanity. He became very influential in Melbourne; the future prime minister Alfred Deakin saw Strong’s views as a way to unite spiritualism with social action.118 Anderson also imbibed such views. In 1888, he left Melbourne to become a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Sydney. In 1890, he was appointed to the new Challis chair of philosophy. Essentially, Anderson was a Christian ‘idealist’ – as were most philosophers educated in Scotland in the late nineteenth century. He constructed a wide ranging curriculum that embraced ancient and modern philosophy, and psychology and sociology, with attention to education, economics and even science.119

37John Adams was an undergraduate companion of Anderson’s at Glasgow University. Born in Glasgow in 1857, the son of a master blacksmith, Adams began his career as a pupil teacher before attending training college and becoming a school teacher. He then studied at the University of Glasgow, commencing an appointment at the Aberdeen Training College while completing his degree. He continued to move between university, college and schools, gaining experience and knowledge of the theory and practice of pedagogy.120 Adams drew upon this background in a seminal publication on ‘Herbartianism’ that illuminated the educational implications of Herbart’s philosophy. In 1898, the now Professor John Adams of Glasgow University published The Herbartian psychology applied to education. According to one authority, ‘the work burst like a new star into the educational firmament, and everything thereafter was different. Educational science, instead of being a dead language, became a modern living tongue’.121 The new book was more Adams than Herbart. In particular, Adams interpreted the Hebartian idea of interest as a way to motivate students: ‘the theory of interest does not propose to banish drudgery, but only to make drudgery tolerable by giving it meaning; so far from enervating the pupil, the principle of interest braces him up to endure all manner of drudgery and hard work.’122

In 1902, Adams was appointed professor of education and principal of the London Training College, which was attached to the University of London. This soon became the premier institution in the Empire for the study and development of the discipline of education.123 For two decades, from 1902, Adams extended his influence through American tours, while various educators came to London. Adams and his protégé, Percy Nunn, virtually founded the field of educational psychology in Britain. Initially, they turned to psychology to improve the understanding and practice of teachers. Others went further, embracing a new ‘science’ of education and child development based on testing and measurement. The main disciple of this approach was Cyril Burt, who was created the official psychologist of the London County Council in 1911. Burt’s focus on ‘intelligence’ in

38children helped to provide a new way of classifying students.124 Adams’ influence in the Empire and the United States would have a significant impact on Alexander Mackie’s career.

On 9 March 1906, Alexander Mackie submitted an application for the position of principal of the ‘Government Training College for Teachers, Sydney New South Wales’. He had excellent references from his teachers and colleagues at Edinburgh, including Professors Simon Laurie, Andrew Pringle-Pattison, James Seth and Andrew Darroch, all in education, and Professor Joseph Shield Nicholson in political economy. He also had references from Maurice Paterson, rector of Moray House, and H.R. Reichel, then vice-chancellor at Bristol.125 On this occasion, Alexander’s networks of support resonated with the selection committee, most of whom would have known his referees personally. The chair of the committee was Professor John Adams, and other members included John Struthers, head of the Scottish Department of Education, and Graham Wallas, a Fabian socialist, founder of the London School of Economics and chair of the London County Council Sub-Committee on the Training of Teachers.126 The selection committee was thus principally Scottish in origin and committed to modern and professional methods of education and teaching.

According to the Australian Journal of Education, the field for the position was restricted by the relatively low salary of £750 per annum.127 There were thirty-one applicants for the position, including many schoolmasters, at least two with academic experience in education: Charles Chapple, who was the principal of a training college in Argentina, and Frank Fletcher, who was professor of education at Hartley College at the University of Southampton.128 A Sydney press report in August 1906 suggested that there were no applicants from the United States and only six from Australia. The report of the selection committee stated: ‘We are of the opinion that Mr Mackie is the best all round man … who, we think, ought to be selected.’ The New South Wales government accepted this view.129

39Alexander left for Australia on 12 October 1906. In the days before his departure, he wrote to his father on a number of occasions. While in London, he visited Professor John Adams and John Struthers, and saw the agent-general for New South Wales.130 On his day of departure, he noted: ‘A beautiful morning. My train goes at 11.30 to Tilbury.’131 Mackie embarked aboard the Moldavia, a 9,500-ton passenger steam ship built in Glasgow in 1903 for the Peninsular and Orient line to travel between England and Australia via the Suez Canal. He was facing a voyage of 12,000 miles, but he had no concern for the reptiles that his aunt believed he would encounter in the Antipodes.132

Deveron Bridge, Huntly – the site of fishing for young Alexander Mackie. USA: M. Mackie Acc 2023.

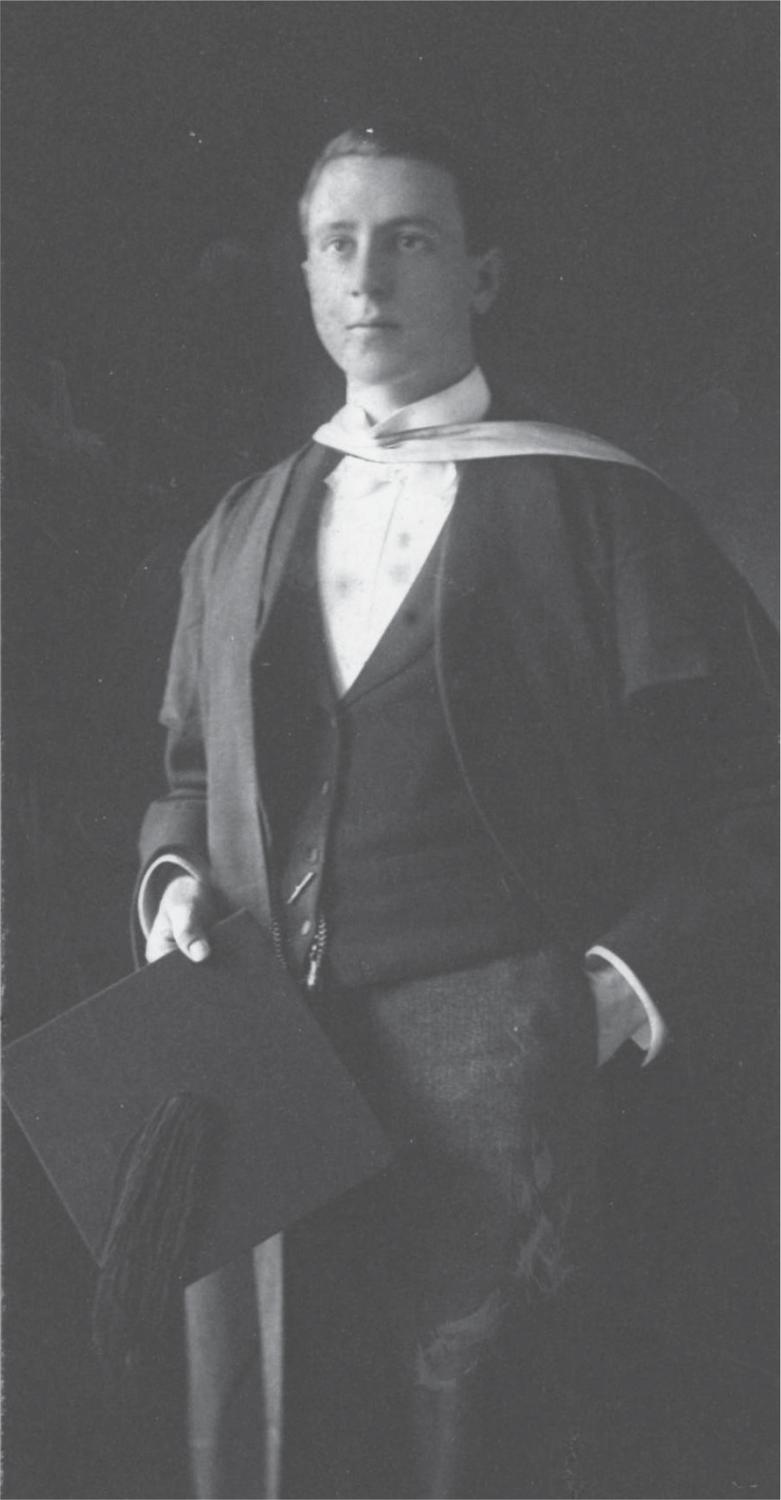

Alexander Mackie in 1894. USA: A. Mackie P169/37/18.

Alexander Mackie as pupil teacher in the 1890s. USA: A. Mackie P169/37/23.

Alexander Mackie upon graduation from the University of Edinburgh in 1900. USA: A. Mackie P169/37/23.

Alexander Mackie on rock in Carnarvonshire, Wales. USA: A. Mackie P169/37/70.40

8 USA: Biographical file 862/868; Alexander Mackie.

9 USA: Alexander Mackie personal archives P169/1; School exercise books of William Mackie.

10 USA: 862/868; Alexander Mackie; USA: A. Mackie P169/40 Family history; Margaret Mackie, A Wahroonga childhood.

11 USA: Margaret Mackie personal archives Acc 2023, Box 1; Power 1998, 16.

12 USA: A. Mackie P169/2 Letters received by William Mackie; Maggie Mackie to William Mackie, 20 September 1892. In late nineteenth-century Scotland, a ‘masher’ was a ‘dandy’ dressed up to attract the opposite sex.

13 USA: M. Mackie Acc 2023, Box 1; Power 1998, 1–10.

14 USA: A. Mackie P169/2; Alexander Mackie to William Mackie, August 1899.

15 Fry 2009, 283–84.

16 Horn 1967, 1–4.

17 Horn 1967, 6–9.

18 Horn 1967, 40.

19 Horn 1967, 41–43.

20 Allan 2015, 114–32.

21 Anderson 1983, 9–10, 123–26, 299.

22 Myers 1983, 76.

23 Anderson 1983, 1–26, 358–61. See also Davie 1964.

24 Anderson 1983, 6.

25 Northcroft 2015, 176.

26 Northcroft 2015, 171–89.

27 Fry 2009, 283.

28 Anderson 1983, 20.

29 Anderson 1983, 21.

30 Anderson 1983, 162–202.

31 Harrison 1920, 33.

32 Harrison 1920, 28.

33 Anderson 1983, 174–79.

34 Anderson 1983, 44.

35 Anderson 1983, 206–8.

36 Anderson 1983, 306–7.

37 Fry 2009, 103.

38 Fry 2009, 298.

39 Anderson 1983, 180–81.

40 Harrison 1920, 40–48.

41 Anderson 1983, 20, 175–76.

42 USA: A. Mackie P169/5 Educational certificates and results of Alexander Mackie; Daniel Stewart’s College certificate of merit, 1884.

43 Harrison 1920, 47.

44 USA: A. Mackie P169/10 Drafts of talks by Alexander Mackie; Alexander Mackie’s speech on Ivan Turner’s inauguration as the new principal, 1951.

45 USA: 862/868; Alexander Mackie.

46 Perkin 1969b.

47 Simpson 1898, 188.

48 Stevenson n.d., 31.

49 Stevenson n.d., 40.

50 Bischof 2015, 208–15. See also Myers 1983, 76–77.

51 Cruickshank 1970, 28–29.

52 Cruickshank 1970, 40–41.

53 Cruickshank 1970, 51–53.

54 Myers 1983, 83–85.

55 Cruickshank 1970, 65.

56 Templeton 2010. See also Knox 1962.

57 Knox 1962, 139.

58 Laurie 1913 [1882], 10–11.

59 Laurie 1913 [1882], 11–17.

60 Laurie 1913 [1882], 20–33.

61 Bell 1983, 158.

62 Davie 1964; Walker 1994, 58–71.

63 Anderson and Wallace 2015, 265–85; Sherington and Horne 2010, 36–51. See also Walker 1994, 72–84.

64 Turner 1990, 19–38.

65 Knox 1962, 141–44.

66 USA: A. Mackie P169/3 Letters received by Alexander Mackie 1892–1955; S.T. Laurie to Alexander Mackie, 26 June and 29 July 1910.

67 Corr 1983, 137.

68 Corr 1983, 138–50.

69 USA: A. Mackie P169/5; Agreement between Edinburgh School Board and William Mackie, January 1893.

70 USA: 862/868; Alexander Mackie.

71 USA: A. Mackie P169/12 Applications by Alexander Mackie for positions; Applications and testimonials, Maurice Paterson, Rector, United Free Church Training College, Moray House, 9 March 1906.

72 Cruickshank 1970, 119–21.

73 Anderson 1983, 252–93.

74 Bischof 2015, 208.

75 USA: A. Mackie P169/5.

76 Collini 2006, 15–64.

77 Jones 2007, 9.

78 Perkin 1969a.

79 Perkin 1973, 74–75.

80 Anderson 2004, 55–56.

81 Allan 2015, 97–113.

82 Selleck 1968, 227–32.

83 Selleck 1968, 235–36.

84 Anderson 2004, 155–56.

85 Flesch 2017, 14–16. See also Spaull and Mandelson 1983, 81–117.

86 Gordon and White 1979, 10–12; Richter 1964.

87 Gordon and White 1979, 13–47.

88 Gordon and White 1979, 67–88.

89 Richter 1964, 354–55.

90 Gordon and White 1979, 177–78.

91 Gordon and White 1979, 12, 59.

92 Jones and Muirhead 1921, 90–91.

93 Addison and Poon n.d.; Boucher 2015.

94 Graham n.d.

95 USA: A. Mackie P169/3; A.S. Pringle-Pattison to Alexander Mackie, 28 July 1899. See also Collini 1976.

96 USA: A. Mackie P169/3; A.S. Pringle-Pattison to Alexander Mackie, 29 March, 30 November and 10 December 1901.

97 USA: A. Mackie P169/7 University essays and notebooks of Alexander Mackie; ‘Plato’s theory of education and its relation to modern educational practice’.

98 USA: A. Mackie P169/7; ‘Plato’s theory of education’.

99 Bain 1879.

100 USA: A. Mackie P169/7; ‘The science method in relation to educational method’.

101 USA: A. Mackie P169/12; Applications and testimonials, A.S. Pringle-Pattison, 8 March 1906.

102 USA: A. Mackie P169/12; Alexander Mackie to agent-general for New South Wales, 9 March 1906.

103 Baillie 1968, 85.

104 For Cambridge, see Hirsch and McBeth 2004.

105 Turner 1990, 19. See also Furlong 2013, 16–17.

106 Ogren 1953, 67.

107 Lowe 1989, 163–80.

108 Perkin 1973, 77.

109 See Darroch 1914; Darroch 1907.

110 USA: A. Mackie P169/3; A.S. Pringle-Pattison to Alexander Mackie, 21 December 1902; USA: A. Mackie P169/3; J. Seth to Alexander Mackie, 21 December 1902.

111 Thomas 1990, 9.

112 Gordon 1990, 165, 170.

113 See comments of Mackie, Green and Gibson in USA: A. Mackie P169/12; Applications and testimonials.

114 USA: A. Mackie P169/12; Applications and testimonials, H.R. Reichel, principal of University College of North Wales, 26 January 1905.

115 Macdonald 2015, 293.

116 Anderson and Wallace 2015, 281.

117 Pietsch 2013.

118 Brett 2017, 208–10.

119 O’Neil 1979.

120 Rusk 1961, 49–50.

121 Rusk 1961, 54.

122 Rusk 1961.

123 Aldrich 2002, 1–40.

124 Woolridge 1994, 11–12, 62–64.

125 USA: A. Mackie P169/12; Applications and testimonials.

126 For Wallas, see Aldrich and Gordon 1989, 252–53.

127 Boardman et al. 1995, 24.

128 Boardman et al. 1995.

129 Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 1906.

130 USA: A. Mackie P169/2; Alexander Mackie to William Mackie, 10 and 11 October 1906.

131 USA: A. Mackie P169/2; Alexander Mackie to William Mackie, 12 October 1906.

132 USA: 862/868; Alexander Mackie.