5

Learning English as an additional language (EAL) through the pedagogy of educational drama

Learning English as an additional language

When you have to use your imagination [in drama], you can think up better ideas . . . so when you think, you must be learning English. (10-year-old EAL student)

The comment from this student is representative of what many EAL students from low socio-economic status backgrounds (SES) believe about the usefulness of drama for English learning and comes from data collected for the Fair Go Project (FGP). This article illustrates findings from the FGP and demonstrates why educational drama pedagogy as an art form is well placed for enhancing academic English, and at the same time, engenders EAL students from low SES backgrounds with a sense of engagement in the learning process and school in general. The term ‘educational drama’ is used to encapsulate the centrality of enactment within this pedagogical approach. As well, participants both lead and control the process with, when required, teacher/facilitator guidance. From here on however, the term ‘drama’ is used.

The Fair Go Project

The first phase (2001–2004) of the Fair Go Project (FGP) was a partnership between the NSW ‘Priority Schools Funding Program’ and the University of Western Sydney’s ‘Pedagogy in Practice Research Group’. Since then other projects have been conducted (Munns et al. 2013). The program is based on the premise that student engagement is a critical condition for improved academic outcomes. Thus the FGP team (initially comprised of 10 university lecturers) set out to develop a pedagogical framework for student engagement. The FGP defines engagement in learning as something more than ‘compliance’ or ‘on task’ behaviour and so examines what pedagogical approaches might engage students. This view stems from an enduring long-term belief that educational achievement is a realistic aspiration for students from socio-economic and educationally disadvantaged backgrounds.

This initial project tested the FGP’s model of engagement using each of the university researcher’s respective skills and expertise. Each university researcher co-researched with full-time classroom teacher/s. My expertise is centred in developing and implementing drama teaching and learning sequences to improve EAL students’ English.

Why drama for learning English as an additional language?

To be competent in conversational English takes about one to three years. To learn academic English (the language specific to a particular subject/content area) takes approximately seven to 10 years (Cummins 2008; Hakuta et al. 2000). Attaining academic English proficiency requires practice in a range of registers and language functions and is best achieved in authentic and believable situations (Cummins 2000; Gibbons 2009). Nevertheless, creating such situations is difficult because often the best situations to practise so many language forms may not be part of a school’s regular program. This is why drama is well placed for language learning in the classroom. In drama, ‘here and now’ albeit fictional contexts are created to parallel reality. Through the process of enactment, students practise language across a range of situations (field) and through the status or relationship between the participants/actors (tenor) – hence the way the message is transmitted (mode) can be many and varied (Hertzberg 2012; Kao & O’Neill 1998; Liu 2002; Stinson 2008; Wagner 1998).

The drama pedagogy explained in this article emanates from dramatic play used by young children. Dramatic play enables the very young to create ‘here and now’ fictional contexts to enact stories. Through enactment they learn and practise a range of vocabulary and language structures in addition to the daily language of ‘real life’ home routine (Bruner 1986). Children play, for example, doctors and nurses/going on a picnic/performing at a circus/cooking a pizza and so forth, to use language relevant to the situation. Furthermore, when adults join in the play they extend the talk by having conversations which usually involve open-ended questions and/or elaborated comments to further extend the scenario taking place (Arthur et al. 2012; Dockett & Fleer 2003; Hertzberg 2012). In so doing, adults importantly model new vocabulary and language structures to both enhance the drama and provide new language learning opportunities (Bruner 1993; Halliday 1985). But talking to practise vocabulary and grammar is not the only important reason.

Interacting with others is essential for abstract thinking and problem solving. In Vygotsky & Kozulin (1986), Vygotsky (1986) referred to this interactive talk with others as ‘outer speech’ maintaining that it allows us to think in different and imaginative ways as we negotiate with people. This in turn helps clarify concepts with ourselves, which Vygotsky termed ‘inner talk’ or ‘verbal thought’ to explain this abstract self-clarifying and/or problem-solving talk. As for young children, when older students are engaged in the process of enactment they are in authentic and hence believable (albeit fictional) situations to practise English for different purposes. Barrs et al. (2012) explain this using the term ‘oral rehearsal’ and elsewhere I have coined the term ‘role to speak’ (Hertzberg 2004a, 2012).

For the above reasons therefore, and not surprisingly, drama is a suggested task in all the worldwide EAL curriculum and supporting documents I have cited. Just one example for instance is the Western Australian EAL/D progress map, which informs some of the Australian Curriculum’s teacher resource material (www.acara.edu.au). Either role play or other drama forms are suggested 29 times whereas completing a cloze task (for reading comprehension) is mentioned seven times. A similar statistic is true for all other documents cited. This is not to dismiss the extremely important benefits of the cloze strategy for language learning. Indeed, from anecdotal experience I suspect many teachers plan cloze tasks for students more frequently than drama tasks. The reasons for this may be varied but interrelated. Many specialist EAL teachers and mainstream teachers of EAL/D students have minimal or no drama training. For many untrained but ‘willing to give it a go’ teachers, initial attempts may not be successful and so understandably drama is relegated to the ‘too hard basket’, for as one of my co-researchers stated:

I know that drama is a great way to get kids speaking and I do use puppetry quite a bit for that reason, but I find role-plays a real problem because [it] always ends up . . . [a bit of mess].

However, this teacher began to use drama regularly after the results from this research indicated that drama both improved English learning and engaged students.

The Fair Go Project’s pedagogical framework for student engagement

The project was influenced and informed by the research of both ‘authentic’ pedagogy (Newmann & Associates 1996) and ‘productive pedagogies’, (QSRLS 2001) as well as Bernstein’s (1996) important research about how the type of curriculum planning can convey messages to students that influence their attitude to learning. The notion of engagement became the central focus of the FGP, based on the premise that student engagement is a critical condition for improved academic outcomes. In most of the research schools (all in south-western Sydney) there were a high percentage of EAL learners (in some schools as high as 98 percent) and these learners were from a diversity of backgrounds and experiences, including Indigenous students and students from refugee family backgrounds (FGPT 2006).

There is always the risk of stereotyping, but data from teacher interviews confirmed that many low SES students found engaging with school, and by implication learning, problematic (FGPT 2006; Munns 2007; Munns et al. 2013). Many teachers had high academic expectations for their students, but many students resisted the challenge because they did not sense that academic achievement was their prerogative – it was seen as the domain for advantaged groups, but not part of their reality. At times a vicious circle ensued with students resisting more challenging work but willing to participate in low challenging procedural tasks, and so a sense of compliance set in. With few exceptions, classrooms were peaceful places, but for many were students learning below their full potential. This is why the FGP centralises student engagement as the driving force to enhance both learning and social outcomes, so that students will ‘buy into’ the educational experience and hence have a long-term belief that educational achievement is a realistic aspiration for them.

The FGP’s definition of engagement

The FGP uses the term ‘in task’ as opposed to ‘on task’ when determining engagement, because the word ‘in’ suggests more of a commitment—that one is inside the metaphorical space. Conversely, the word ‘on’ suggests being on the borderline and/or surface level of the metaphorical space. Thus the FGP maintains that students completing low level, low challenging tasks are not really committed to learning and are not ‘in task’; rather they are being compliant. Further, the FGP identifies two forms of engagement: small ‘e’ engagement and big ‘E’ engagement. Small ‘e’ engagement is when students are involved in open-ended substantive learning tasks (in task). Because the FGP views engagement as a feeling or an emotion that is internalised, the FGP asserts that when students experience appropriate pedagogy over extended and sustained periods of time (usually longer than a year), big ‘E’ engagement might be achieved because students have developed a personal commitment and trust in themselves. That is, the students might have a long-term belief that ‘school is for me’ and so the FGP team uses the term ‘future in the present’ based on the notion that the future (school is for me) is within the present (in task ‘e’ngagement), as illustrated in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Links between ‘e’ and ‘E’ – ‘the future in the present’

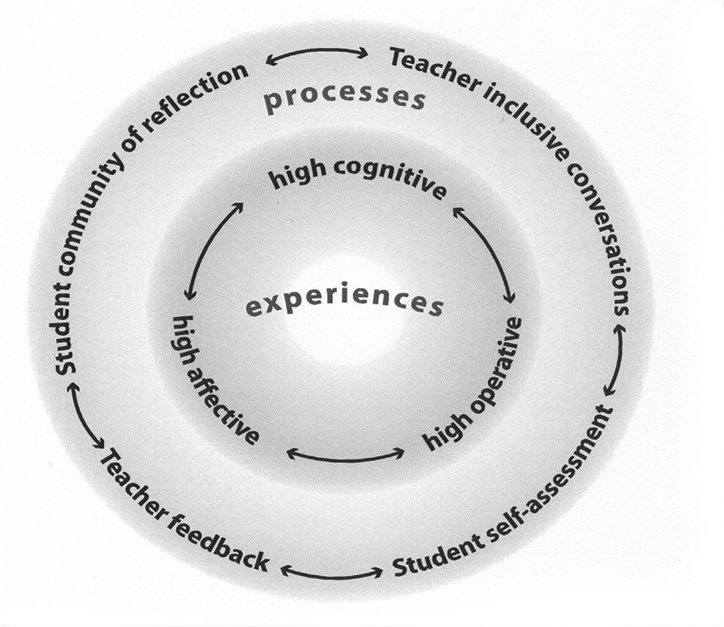

The FGP contends that pedagogical processes that achieve small ‘e’ engagement are ‘high cognitive’ (a task that requires deep thinking and by implication problem solving), ‘high affective’ (a task that promotes committed feelings while doing) and ‘high operative’ (actively involved in the doing). In classes where this process is occurring there appears to be an inextricable link between all three (Hertzberg et al. 2006; Munns et al. 2012; Munns et al. 2013), as seen in Figure 5.2.

The outer circle of this same figure (Figure 5.2) describes what the FGP refers to as ‘insider’ classroom processes. These processes are inextricably linked to and support the learning experiences, because students view themselves as an important part of a reflective learning community driven by teacher inclusive conversations, student self-assessment, and teacher feedback. Within this reflective learning community teachers send messages that both validate and respect the role of the student in the pedagogical process. Therefore, and in tandem with the engagement framework in Figure 5.2 above, Table 5.1 below illustrates the five messages identified by the FGP as ‘engaging messages’ for low SES students. The FGP contends that when students receive positive messages about their knowledge, their ability, their role in classroom control, their place and their voice they have a feeling of empowerment and are able to enact the term ‘discourses of power’.

This FGP model of engagement was used in the research described below.

Research context

The project was a partnership between the NSW Department of Education’s ‘Priority Schools Funding Program’ (PSFP) and the University of Western Sydney’s ‘Pedagogical in Practice Research Group’. Over a three-year period ten research projects were conducted in nine PSFP south-west Sydney primary schools, selected because of the low SES of the student community. Each university academic formed a collaborative research partnership with a teacher/s, co-planned and co-taught. With all students in mind, and including EAL learners, my research questions were:

- Is educational drama a pedagogy that might provide engaging messages for low SES students?

- Is educational drama a pedagogy that might enhance language and literacy outcomes and if so what factors might make this so?

In line with socio-cultural linguistic approaches (e.g. Cummins 2000; Gibbons 2009), the lesson sequences to research these questions placed an emphasis on using drama to promote oracy prior to and during reading and writing tasks.

This article refers to two sites and the teachers did not have drama training. The research was primarily undertaken in Site A, a mainstream 5/6 class (10, 11 and 12-year-olds) at a primary school in the Liverpool area. The co-researchers were the mainstream class teacher Kerrie Foord and EAL teacher Melissa Magna. I co-taught for 1½ hours each fortnight over one school year. The students were from cultural and linguistically diverse low SES backgrounds and 62 percent of students needed EAL assistance. As most had been learning English for at least five years their conversational English was good, but their academic English required attention. Further, it could be argued that most students needed extra English support irrespective of language background. Site B was a primary school in a housing estate near Campbelltown and my co-researcher Susan Barrett taught Year 5 (10 and 11-years-old). I co-researched with Susan for two hours per fortnight over ten weeks. The cohort was similarly culturally and linguistically diverse but with a higher proportion of Indigenous students.

We used ethnographic methodology, with a combination of case study and action research. Data were collected through observation and discussion between the university-based researcher and the classroom teacher-based researcher, and from student written work samples, video, photos, field notes, semi-structured interviews and focus groups with students and staff.

Analysing data

Student and teacher interviews, researchers’ field notes, student work samples and photos were analysed and then coded based on emergent themes identified in the Fair Go Project model of student engagement. Specifically data were coded according to whether they demonstrated that the task was high cognitive and/or high affective and/or high operative for a specific student and/or small group of students and/or whole class. These same data were also analysed and coded for evidence that the drama pedagogy provided students with engaging messages as defined in the FGP’s ‘Discourses of power and engaging messages for low SES students’ (knowledge, ability, control, place and voice). To analyse how and why this drama pedagogy assisted English learning, data were analysed according to the socio-cultural linguistic principles of English language learning.1

Reporting findings

Space precludes reporting all findings so just two drama teaching and learning sequences are analysed from Site A. When discussing engagement more generally, findings from both Site A and B are reported. Priority is given to both student work samples and opinions from interview data, following the premise that for many students from low SES backgrounds to be capable of long-term engagement, they first need to feel confident that school can be ‘for them’. Their voices need to be heard and analysed. The findings illustrate that this drama pedagogy engaged many previously disengaged students. This is exemplified by the comment of one of the most disaffected students I have ever taught. In interview he told me ‘he loved drama’. Playing devil’s advocate I suggested he might like drama because it wasted time from what he might regard as ‘real work’, but he vehemently stated that:

It’s (drama) NOT wasting time because wasting time means like you’re out of it, like you’re not doing anything (and) you’re just sitting there bored, but if you are in it, it’s like it’s fun and then you’re learning. (Site B)

To demonstrate improved learning outcomes and improved commitment to learning, two snapshots from Site A follow to highlight how incorporating drama within an English program adds a level of deep understanding. First, each learning sequence is summarised, with a discussion for each in terms of the FGP model of engagement and the socio-cultural linguistic principles of English learning. Second, both sequences are discussed more generally in terms of the engaging messages received (discourses of power).

Learning sequence 1. Sculpting a prominent issue/theme in a narrative to enhance interpretative comprehension and acquire new vocabulary

The aim was to analyse critically the theme of bullying in a picture book (Geoghegan & Moseng 1993) in preparation for reading it with the students’ younger buddy class. While the written text is simple (although challenging for some students), the theme of emotional abuse on the basis of difference was age appropriate as was the concept of anthropomorphism.

Lesson sequence

- The anticipated outcomes from the departmental syllabus document and definitions of fable and anthropomorphism were displayed and explained.

- Teacher read the book to students.

- An excerpt of written text was displayed. It is about one pig (Paprika) being ridiculed by five other pigs for being different – having a straight tail.

- Students wrote a response to the following question: How do you think Paprika felt and why?

- Working in pairs, one student sculpted the other as Paprika to show his/her interpretation of this scene.

- Class viewed and discussed the different interpretations and then brainstormed appropriate vocabulary to describe these sculptures (Paprika).

- Students returned to their previous written response to add additional information

Discussion and implications in terms of English language learning

Opportunity for a more in-depth and elaborate written response

Students were asked to write their response before doing the drama activity, because we wanted to find out if they had more to write after the sculpting exercise. Most did. Josie’s example follows:

(Before sculpting she wrote)

Paprika must have felt like being the other person instead of the bullied one. She also must of felt alone.

(After sculpting she added)

She felt depressed and the other person is feeling guilty. She felt discriminated. When I did the activity I felt that I was Paprika and felt alone.

Josie’s sample demonstrates the use of more descriptive vocabulary to express further ideas gleaned from this four-minute drama activity. Note also the affective response about feeling like Paprika. This response was not unique in the written samples and in interview students responded similarly. This result corresponds with Barrs et al. (2012), who state that in role:

[students] are able to access other ways of talking . . . Putting oneself in somebody else’s shoes . . . can enable someone to get closer to that person’s thinking and way of using language . . . [and] in the process they broaden their own linguistic range. (18)

In the EAL literature, the importance of interrupting the teacher initiates – student responds – teacher evaluates (IRE) cycle is important because it often limits both the amount and type of talking students produce, especially in a whole class situation (Cummins 2000; Gibbons 2009). Furthermore, the research of Mercer (2000) demonstrated that ‘exploratory talk’ as opposed to simple descriptive responses improves a student’s ability to reason and problem solve.

As identified in teachers’ field notes all students were involved actively in sustained ‘exploratory talk’ when discussing the concept to prepare their sculpture. The excerpt from one pair’s talk demonstrates this:

Put your head down and sit kind of squashed up so you look really lonely and close your eyes to show that you want to ignore them, but look really sad too because they are trying to discriminate against you and make you feel bad.

All students interviewed thought their ‘oral rehearsals’ (Barrs et al. 2012) gave them a ‘role to speak’ (Hertzberg 2004a & 2012), and subsequently helped them write their ideas. Ahmed’s statement is representative:

Like if you write it, you don’t talk to anyone and you just think it out in your head . . . you don’t get to give your opinions [like you do in drama] and then you can use them [in your writing].

The above example of ‘exploratory talk’ reveals an oral comprehension exercise at an interpretative level.

Learning Sequence 2. Using questioning in role to enhance inferential comprehension

Issues around migration feature in the picture book Marianthe’s story (Aliki 1998). With no country names disclosed, the story universalises themes such as displacement, language and custom barriers. Much of the story is only told in the visual text.

- To connect students to just one major theme before reading the book, students were asked to prepare individual still images to convey how they might feel going to a new school unable to speak English.

- Students brainstormed for vocabulary to convey this feeling and used these words later in a voice collage.

- Teacher read the book.

- Students reread the book in pairs (there were enough copies for one book per pair).

- The drama strategies of sculpting, voice collage, still image, role walk and parallel improvisation were then used to interpret the narrative’s major and varied themes (refer to Hertzberg 2004b).

- The drama strategy of Questioning in Role (Q in R) was used. The father is a central character, however the father’s migration from a war-torn country to a prosperous safe country is not detailed. All we know is that he left before his wife and children to earn money and find suitable accommodation. He wrote a letter about this but the story does not reveal its contents. The father (teacher in role) was questioned to find out his location, circumstances and feelings. Using this information, students in pairs wrote the father’s letter to his family.

Discussion and implications in terms of English learning

Opportunity for a more in-depth and elaborate written response

One of the most compelling qualities of picture books is that they leave ‘spaces to play’, a term first coined by Williams (1991). The illustration of Uncle Theo reading the father’s letter without supporting written text leaves such a ‘space’ and Q in R enabled students to infer about the father’s probable experiences. Students found Q in R before writing helpful, for as one student stated, ‘I’ll be able to use this during the [national] writing test’. When asked to explain she elaborated:

Well if I pretend that I’m doing drama [Q in R] then I’ll use my imagination and come up with some good ideas, because they [writers of the test] give you a picture [and you have to use this to write a story] and I never know what to write about.

Many questions to begin the Q in R were mundane and/or closed, but students soon realised (without prompting from teachers) that open-ended analytical questions were needed to enable a substantive story to unfold. One teacher took notes as the story progressed and this summary was then printed and distributed to each pair to use as the ‘back bone’ for their letter. The letter below (corrected only for spelling, punctuation and grammar) was not the best example. It was selected for this article because it was written by two students performing well below age and grade expectations. Their commitment to school and learning was negative. Yet their teachers said it was their best work to date. Their letter is in accord with Booth and Neelands’ research (1998) about using drama to improve writing. They contend that:

The experience of taking on a character in drama also provided many students with enhanced empathy and understanding for a broad range of people . . . [allowing] them to write sensitively and genuinely from a variety of different points of view . . . Finding out about a character by asking questions and listening to and watching the responses the character makes . . . will flesh out literally, the student’s own ideas. (pp20–22)

For many in this cohort, migration is part of their schematic knowledge and the EAL literature (e.g. Cummins et al. 2006) highlights the importance of connecting with students’ schematic knowledge as a means of extending learning. This was one reason for selecting this book. In addition, the data indicate that Q in R helped students use their ‘text analyst practices’ (Freebody 2004) to read critically inferred meanings with an extra dimension of sensitivity and awareness. Both these aspects may have contributed to these boys exceeding expectations. As one said:

My Dad’s a refugee and he always tells me how lucky I am and how great Australia is and like I sort of understand, but now I reckon I understand deeper because I had to really think about it [the issues] to do the drama.

3/16 Stacey St

Liverpool NSW 2170

Australia

16th August 2003

My dear wife and children,

Thank you sooooooooooooooooooo much for the letters. Mari your writing is really good. Do you like going to school?

I really miss you all, but I’m Okay. I have moved to a new flat in Liverpool which is good because it is closer to the factory that I work at. I have made friends with the people next door. They have twins, but they are girls and not boys. They are cute and remind me of the boys. The mother’s name is Rima and she cooks nice food and I play cards with her husband.

Well I have to go now because I am tired.

I can’t wait until I have enough money so you can come here.

Lots of love

Dad

xxxxxxxxxxxxxx000000000000000000000000xxxxxxxxxx

PS Mari the kids are nice here and will be kind to you at school.

Bolton (1992) explains that drama provides a pivotal learning opportunity because of the link between the fictional world and reality. He terms this ‘metaxis’ (seeing two worlds at the same time). For this student, an in-depth examination of this narrative provided such an opportunity as he re-examined his own life and circumstances. Not only was his writing superior to previous attempts, he was affectively ‘e’ngaged.

Discussion and implications in terms of ‘e’ngagement

Teacher’s field notes consistently noted that during drama most students appeared to be ‘in task’ as opposed to compliantly ‘on task’, or not compliantly ‘off task’ (as was often the case with the authors of the letter just examined). Making a comment about the cohort generally, Melissa wrote:

Students are on task and excited about doing the activities requested . . . even the shy students are giving it a go. There is no apprehension or avoidance behaviour on their part.

That most students were ‘in’ task during both the above sequences is now analysed in terms of the FGP’s model of student engagement. Data from student interviews and work samples indicate that the sequences were high cognitive, high operative and high affective as detailed in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Data as matched with FGP’s engagement framework – small ‘e’ engagement

|

High cognitive (students are thinking hard in challenging intellectual experiences) Students were required to ‘put themselves in someone else’s shoes’ and have sustained exploratory talk with their partner about the issues in order to interpret the theme. This is confirmed by a student who stated that: when I talk about it [bullying] during drama I can think of heaps better ways of saying and I have more to say. Another student said that he had: to think more and I knew more about Bill. I had more ideas but my friend helps me write it because I can’t write good. |

|

High operative and high affective (students are actively involved in open-ended tasks which stimulate them with a sense of enjoyment) It was difficult to differentiate between ‘doing’ and ‘feeling’ in order to code them as discrete results. This association might well indicate that being actively involved gives more commitment to one’s beliefs/feelings as demonstrated in the following comment: ‘It’s fun to do it and not just do the writing . . . because you’re doing it!’ (Site A) The word ‘feel’ was used time and again in interviews. Students commonly made comments such as: because you’re actually being the person you have to work it out and see how it feels. Such statements might suggest that the fictional context enables students through enactment to connect with different viewpoints, or as one student put it: ‘Like isn’t that the whole idea for doing drama because even though you’re not really doing it because it’s pretend you can feel what other people are feeling and learn more.’ (Site A) |

However, a lesson’s content cannot be seen in isolation to the messages that such open-ended activities provide in terms of student empowerment in the learning process. They work in tandem (Munns et al. 2012; Munns et al. 2013).

Discussion and implications in terms of ‘Discourses of power and engaging messages for low SES students’

When analysing student interview data and coding it to the ‘Discourses of power and engaging messages for low SES students’ framework, the importance for frequently using drama for English learning becomes even more compelling as demonstrated in Table 5.3. Data are used from both Site A and B.

Table 5.3 Data as matched with the FGP’s ‘Discourses of power and engaging messages for low SES students’

|

Knowledge (‘We can see the connection and the meaning’ – reflectively constructed access to contextualised and powerful knowledge) Providing intellectually demanding work that students deem relevant is one of the most challenging aspects when working with disengaged low SES students. As discussed previously, for many students entering a fictional world can provide a schematic connection and this seems to create a depth of enthusiasm for learning for as one student stated: If you’re acting you can be a little more passionate about it. Acting gives you more of a picture of what you’re actually doing instead of just writing it. When you write it, it doesn’t stay for long, but if you act it, it’s a memory. (Site A) |

|

Ability (‘I am capable’ – feelings of being able to achieve and a spiral of high expectations and aspirations) The comments below are representative of many students. They indicate feelings of being able to achieve, and the FGP maintains that if this attitude remains consistent over time students might well continue to have high expectations and aspirations. I like it [drama] because I can think big ideas and plus I’m allowed to share them with my friends and I like how we work in groups and have to think for ourselves and I think Miss likes it because we are all good and we work heaps more and then she is happy. (Site B) I love drama because I love acting and telling my story that way. (Site B) |

|

Control (‘We do this together’ – sharing of classroom time and space: interdependence, mutuality and power with) I really like doing reading this way. At first I was nervous because the teacher wants me have my own opinions. (Site A) This comment indicates the sharing of classroom time and space. However, having opinions and sharing with others when not confident about one’s ability involves risk taking. This may be why many low SES students feel safer working on low level procedural tasks as opposed to open-ended problem solving tasks. But enactment can provide a safe haven, for as one student said: I like drama, ’cause you can say things that are you, but nobody has to know because you are acting someone else. (Site A) Risk taking was, according to some students, aided by working in friendship groups. [I like working with friends] because you like them and they like you and then it’s easier . . . you don’t worry about them laughing and all that, so you say more (Site A). |

|

Place (‘It’s great to be a kid from . . .’ – valued as individual and learner and feelings of belonging and ownership over learning Possibly this message is the most problematic and difficult to achieve and yet perhaps crucial, especially for those showing considerable oppositional behaviour. Many students see education as a middle-class prerogative and not available to them. Being valued as a learner and having feelings of belonging and ownership over learning can ‘turn these kids around’ as evidenced from one such student. [Drama is] better, funner, teaching more than doing unjumble the sentence. I just do one of them [unjumble the sentence] and then sit there pretending to do more but I don’t. It’s [drama] teaching more and having fun. (Site B) |

|

Voice (‘We share’ – environment of discussion and reflection about learning with students) In the ‘drama circle’ reflective dialogue which followed many activities, one student said that he thought the way the lessons were sequenced (scaffolded although he did not use this term) was important: because the teacher gives you the bones of it and we have to act the muscles. (Site A) Whilst the teacher initiated the task, the children must take ownership and by implication take the risk to provide the substance. Further, the drama circle provided an environment of discussion and reflection about learning where students and teachers played reciprocal roles, as exemplified by the student who said: Well I didn’t like it [drama circle], because you [teacher] didn’t make [many] comments so I never knew if I was right or wrong, but now I do [like it] because I’ve got used to it and I just say what I think and it’s fun when other people join in. (Site B) |

Limitations

First, as a small-scale piece of qualitative research, there is insufficient longitudinal data. Notwithstanding this, the study does contribute to the body of research that examines the benefits of this drama pedagogy for language and literacy development.

Second, in many books and articles where students’ perceptions about drama are discussed, there are at times qualifications of modality with words such as ‘most students . . .’ or ‘for many students . . .’. This word choice acknowledges that not all students like drama and hence may not be ‘e’ngaged. This might apply to this cohort. However, no negative data was collected from either site even though in interview I probed with questions such as ‘well I’m pleased you enjoyed the drama (name of student) but maybe there are other ways that you would prefer to learn’ or ‘it’s good that you thought it was fun, but maybe you were not learning anything?’ Possibly an interviewer detached from the teaching may have got some negativity due to anonymity. This is an important consideration for future research. Data from teacher interviews and field notes indicated that teachers saw significant improvements in English for many individual students, as well as improved attitudes to school from the cohort as a whole. However, some students may have felt duty-bound to say what they thought the teacher wanted to hear and not mention aspects they did not like and/or did not find useful for learning. We suspect the rebellious students did express their true opinions as there was no hesitation to make negative statements about other areas of their school experience; nevertheless this an issue for future consideration with well-behaved compliant students.

Conclusion

That drama assists EAL students is well known by EAL theorists and policymakers, which is why almost all EAL curriculum and supporting documents worldwide program for the regular use of drama. Drama provides students with ‘a role to speak’ in authentic situations and this ‘oral rehearsal’ aids students’ ‘inner thinking/speech’ which in turn assists both their reading and writing. But that drama can engage disengaged students with learning may not be as well known. This research demonstrated that for these low SES students, the regular inclusion of drama may over time contribute to an enduring long-term belief that education is an achievable aspiration for them and not just for students from advantaged backgrounds.

However, EAL teachers with minimal training in drama do not know why the features unique to drama make it so effective for language learning. As drama educators we must make clear to our non-specialist colleagues the power of drama and I suggest the following three interrelated reasons for a good beginning.

The first is the power of enactment. When the content to be examined is both age appropriate and academically challenging, role-taking for many students enables risk-taking because the enactment process protects them from either making a mistake as their ‘real self’ or revealing their ‘real self’ opinions. For many students this safety net within enactment often leads to profound and committed feelings about the issues and frequently promotes sustained, considered and in-depth analytical conversations. Furthermore, enactment enables students to interpret or infer information in both factual and fictional texts from different points of view. Assessing how another person’s perspective positions oneself is a central tenet of critical literacy.

Second, the pedagogical approach to studying subject content in drama is significant. While the teacher often (but not always) determines the subject area and supporting resources, the ideas and materials for the drama are always negotiated and developed with students. This provides students with a commitment to their ideas and ownership over their learning as evidenced, for instance, when studying Marianthe’s story.

Third, the concept of metaxis (being able to see the world of fiction and the world of reality at the same time), enables students to make authentic and purposeful connections. The ideas/themes/issues are contextualised within the fictional setting but importantly they are then transferrable to the real world. This helps many students better understand and empathise with big ideas and concepts in other areas. To make this connection the significance of the reflection process during the drama is central. The substantive conversations with and between students about their drama not only aid in making immediate connections but many times extend the process leading to enhanced examination of the content and thus further English learning opportunities.

Nevertheless, despite drama’s benefits, there remains another perceived stumbling block to using drama. Many teachers feel pressured by time constraints. Incorporating drama into English programs does make the program longer. However, as demonstrated previously, students believed the extra time taken to incorporate drama before and during reading and writing was helpful. The time factor was raised with Melissa when we discussed whether her program aims could have been achieved more quickly or efficiently without drama.

No. No way. I don’t think so. Yes, it’s much longer than giving a very expository lesson and saying ‘OK, we’ve read this passage and now I want you to go away and write your opinion about Jack and why you think he finds it difficult to talk to his Mum’. Or ‘OK, now let’s look at how the author has used direct and indirect speech’ and then have a teacher-directed question time. But drama – OK, it did take longer – but all the kids are involved and I really think they are learning more and more deeply, and that’s for me what quality teaching is about. It’s not how long or short the lesson is that matters – it’s whether they are learning anything substantial. This comes back to the point I made about risk-taking earlier [in this interview]. I said many kids here don’t like to take risks. They don’t want to do anything wrong. They are so scared of getting it wrong. They would rather just do tick-and-flick stencils, but drama takes them outside that box, out of that comfort zone, and they have to really think about the content, which leads to deeper understanding.

Works cited

Aliki (1998). Marianthe’s story: painted words, spoken memories. New York: Greenwillow Books.

Arthur L, Beecher B, Death E, Dockett S & Farmer S (2012). Programming and planning in early childhood settings. 5th edn. Melbourne: Cengage.

Barrs M, Barton B & Booth D (2012). This book is not about drama . . . it’s about new ways to inspire students. Markham, ON: Pembroke Publishers.

Bernstein B (1996). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research, critique. London: Taylor & Francis.

Bolton G (1992). New perspectives on classroom drama. London: Simon & Schuster Education.

Booth D & Neelands J (Eds) 1998. Writing in role: classroom projects connecting writing and drama. Hamilton, ON: Caliburn Enterprises.

Bruner J (1986). Play, thought and language. Prospects: Quarterly Journal of Education, 16: 76–83.

Bruner J (1993). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cummins J (2000). Language, power and pedagogy. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins J (2008). BICS and CALP: empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. In B Street & N Hornberger (Eds). Encyclopaedia of language and education (pp71–83). 2nd edn. New York: Springer Science + Business Media.

Cummins J, Bismilla V, Chow P, Cohen S, Giampapa F, Leoni L et al. (2006). ELL students speak for themselves: identity, texts and literacy engagement in multilingual classrooms [Online]. Available: www.curriculum.org/secretariat/files/ELLidentityTexts.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2011].

Dockett S & Fleer M (2003). Play and pedagogy in early childhood: bending the rules. 2nd edn. Sydney: Harcourt Brace.

Fair Go Project Team (2006). School is for me: pathways to student engagement. Sydney: Priority Schools Programs, NSW Department of Education and Training.

Freebody P (2004). Hindsight and foresight: putting the four roles model of reading to work in the daily business of teaching. In A Healy & E Honan (Eds). Text next: new resources for literacy learning (pp3–17). Sydney: Primary English Teaching Association.

Gibbons P (2009). English learners’ academic literacy and thinking: learning in the challenge zone. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Geoghegan A & Moseng E (1993). Six perfectly different pigs. London: Hazar.

Hakuta K, Butler Y & Witt D (2000). How long does it take English learners to attain proficiency? The University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute Policy Report 2000–1 [Online]. Available: www.stanford.edu/~hakuta/www/research/publications.html 5_Acquiring–a–Second–Language–for–School_DLE4.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2011].

Halliday MAK (1985). Spoken and written language. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Heathcote D & Bolton G (1995). Drama for learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s mantle of the expert approach to education. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hertzberg M (2004a). Unpacking the drama process as intellectually rigorous – ‘The teacher gives you the bones of it and we have to act the muscles’. NJ (Drama Australia Journal), 28(2): 41–53.

Hertzberg M (2004b). Drama when English is an additional language. In R Ewing & J Simons with M. Hertzberg. Beyond the script. Take two: drama in the classroom (pp93–108). Sydney: Primary English Teaching Association.

Hertzberg M, Foord K & Manga M (2006). Dramatically ‘e’ngaged. In Fair Go Project Team, School is for me: pathways to student engagement. Sydney: Priority Schools Program, NSW Department of Education and Training.

Hertzberg M (2012). Teaching English language learners in mainstream classes. Sydney: Primary English Teaching Association.

Kao SM & O’Neill C (1998). Words into worlds: learning a second language through process drama. Stamford, CT: Ablex.

Liu J (2002). Process drama in second and foreign language classrooms. In G Brauer (Ed). Body and language: intercultural learning through drama (pp51–70). Westport: Greenwood.

Mercer N (2000). Words and minds: how we use language to think together. New York: Routledge.

Munns G (2007). A sense of wonder: pedagogies to engage students who live in poverty. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11(3): 301–15.

Munns G, Arthur L, Hertzberg M, Sawyer W & Zammit K (2012). A fair go for students in poverty: Australia. In T Wrigley, R Thomson & R Lingard (Eds). Changing schools: alternative ways to make a world of difference (pp167–80). London: Routledge.

Munns G, Sawyer W & Cole B (Eds) (2013). Exemplary teachers of students in poverty. London: Routledge.

Newmann F & Associates (1996). Authentic achievement: restructuring schools for intellectual quality. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

NSW Department of Education and Training: Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate (2003). Quality teaching in NSW public schools, a classroom practice guide. Sydney: NSW Department of Education and Training.

Queensland School Reform Longitudinal Study (QSRLS) (2001) submitted to Education Queensland by the School of Education, University of Queensland, State of Queensland (Department of Education), Brisbane.

Stinson M (2008). Drama, process drama, and TESOL. In M Anderson, J Hughes & J Manuel (Eds). Drama in English teaching: imagination, action and engagement (pp193–212). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wagner BJ (1998). Educational drama and language arts: what research shows. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Williams G (1991). Space to play: the use of analyses of narrative structure in classroom work with children’s literature. In M Saxby & G Winch (Eds). Give them wings (pp355–368). 2nd edn. South Melbourne: Macmillan.

Vygotsky L & Kozulin A (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Western Australia Department of Education. Curriculum resources. http://www.curriculum.wa.edu.au/internet/Years_K10/Curriculum_Resources

1 Data were also coded to examine if the drama/English plans fulfilled the requirements of the NSW Department of Education and Training’s ‘Quality Teaching Model’ (2003). This is not discussed in this article but readers are referred to Hertzberg 2004b.