6

What’s wrong with the way we teach playwriting?

Well I did the NIDA playwright’s course years ago – people used to give me a little bit of money to write a play and I wrote, and I worked in a TIE [Theatre in Education] community theatre company, and I would create plays professionally. But I still think I am a better marker than I am a teacher of scriptwriting, though I am quite happy with other aspects of my teaching, I do not think that I am a very good scriptwriting teacher in year twelve.

Mr B, St Martha’s

While writing for performance is a core aspect of drama education and drama in education, many teachers approach teaching playwriting with trepidation and ambivalence. Additionally, much of teacher training and high school coursework is focused on devising performance, playwriting is unfortunately an activity on the periphery. I wish to explore the factors that may be contributing to teacher apprehension and to challenge this peripheral status. For many teachers in my study, teaching playwriting was an activity for which they felt unprepared and, as a consequence, many found the experience unsatisfying and frustrating, and considered their efforts to be less than effective. My research sought to understand what it was about the teaching of playwriting that caused such a response from highly successful and experienced teachers.

In an attempt to understand the experience for both teachers and students, I studied the playwriting process in a number of NSW secondary schools. I explored the playwriting experience for students and teachers in order to better understand the teaching and learning that was occurring in the classroom. One of the emerging themes was an aversion to accessing or employing playwriting texts or theory to inform the teachers’ pedagogy, as they considered them to be formulaic and restrictive. To begin my research, I examined the resources available to teachers.

The background literature

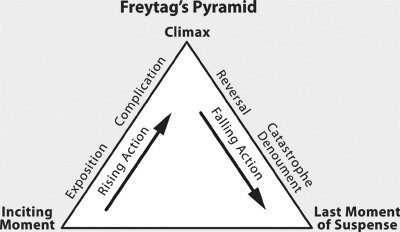

An initial survey of the literature on playwriting suggests that Aristotle’s Poetics (1996) and its focus on plot and a linear narrative still appeared to dominate the pedagogical approach. As McKean (2007) reports, ‘most of the [playwriting] literature organises discussions on finding the shape or form of composition around a linear structure of beginning, middle and end’. Many of the playwriting ‘how to’ books (Catron 2002; Egri 1960; Jensen 1997; Selden 1946; Smiley 2005) either write based on this assumption or structure their approach based on Aristotle’s headings. Yet this predominance is not without its opponents. Castagno (1993) comments that ‘the litany of playwriting texts unhappily persists in the Aristotelian mold’. Waters (2012, 2) reminds us of the need to be wary of Aristotle’s potentially negative influence, suggesting ‘this poster-boy of formal perfection has too often served as a cudgel to beat into shape all sorts of equally good but formally eccentric works’. Norden (2007) was concerned that strict adherence to an ‘Aristotelian’ model could produce a ‘cookie cutter’ mentality and an over reliance on Freytag’s ‘pyramid’ (Freytag 1900), bringing ‘the practice of playwriting perilously close to the acceptance of standard story formats’ (2007, 646). Reflecting this response, and seeing little relevance to their own practice, many playwrights are abandoning Aristotle and what they consider a prescriptive approach to the writing of plays. As Fornes recounts when considering the Aristotelian form: ‘I looked at it and started laughing because I thought: How ridiculous, that’s not the way life happens. And why should one try to follow a formula that has nothing to do with life? (cited in Herrington & Brian, 2006, 4).

Figure 6.1 Freytag’s Pyramid as a model for standard story format. (adapted from Freytag 1900, 114–140)

But is this initial perception correct? Do the Aristotelian playwriting books represent the extent of resources available to the teacher and playwright? The short answer is ‘no’.

A review of the broader literature on playwriting reveals that there is actually a spectrum of theoretical approaches available to the ‘emerging’ playwright and the teacher developing teaching and learning strategies to support the student in the process of writing a play. Roughly speaking, the end points of the spectrum can be described as ‘closed’ and ‘open’.

The closed approach values plot resolution, centres on a single protagonist, struggling against both a fatal flaw and an opponent/antagonist. The approach can be said to reflect a worldview that assumes that ‘certainty’ is possible and that we are agents operating with free will. Plays of this ilk normally include resolved dilemmas, consistent characters, and ‘witty and logically built up dialogue’ (Esslin 1965). In many ways it assumes a tidiness of existence and presents a linear ‘cause and effect’ journey of character.

The open approach on the other hand is informed by the experience of 20th-century avant-garde theatre makers and reflects on an epistemological world view that I describe as ‘embracing uncertainty without despair, and untidiness without chaos’and plays often choose not to resolve thematic ideas or demands of plot, and/or may adopt a cyclical structure that rejects a reliance on ‘cause and effect’. They often include ‘figure conceptions’ rather than psychologically rounded characters. They do not assume the existence of an ‘ultimate’ meaning grounded in resolution and finality (Edgar 2009; Stephenson & Langridge 1997; Waxberg 1998).

The image of the spectrum is relevant, as it removes the idea of ‘camps’ of ‘isms’: realism, absurdism etc. It presents the conventions and techniques as a kind of theatrical smorgasbord. As a spectrum, each individual playwright may choose their own mix of open and closed aspects depending on the central idea and vision of the particular play they are writing. Despite Fornes’ comment, this theatrical Machiavellianism doesn’t privilege one approach over another – the worth of the approach is its ability to effectively communicate the playwrights’ ideas and worldview – the ends must ‘justify’ the means.

This idea is clearly conveyed by Martin Esslin in his introduction to Absurd drama (1965). His explanation of the emergence of Absurdist theatre supports the view that forms, structures and conventions are tools; options not restrictions. Absurdist theatre, he argues, was born from the need to find a way to express each playwright’s unique, revolutionary and ‘personal view of the world’ (14). Rather than creating new techniques, the undeniably transformative effect of these plays came from a ‘new combination of a number of ancient, even archaic traditions’ that were ‘unusual and shocking merely because of the unusual nature of the combination and . . . emphasis’ (14). This view positions the playwright as being in control of the conventions and that knowledge of ‘the rules’ and of what came before, is an essential ingredient in this seismic shift in our definition of theatre. This view is echoed by Castagno and the New Language Playwrights, another group of writers re-inventing the form, who create text that ‘appears strikingly new [but] in ways reformulates solid theatrical practices of the past’ (Castagno, 2001).

Far from limiting creativity, the experience of the Theatre of the Absurd suggests that knowledge of styles, techniques and conventions are necessary for creating new approaches to form. Furthermore, this knowledge feeds the playwrights’ theatrical semiotic ‘vocabulary’, enabling them to not only convey their existing ideas but opening them up to thoughts and ideas previously unfamiliar to them (Nicholson 1998). In this way, knowledge feeds creativity; developing a deep knowledge of the ‘spectrum’ could not only generate new forms, but also generate new ideas. As Waters (2012, 5) argues ‘writing is always an intertextual act: the plays of our predecessors generate ones we’ve yet to dream up’. This would suggest that an effective pedagogical approach to playwriting should be informed by this spectrum. With knowledge of the literature available to the teachers in planning their pedagogy, I sought to research the impact of theory on classroom practice.

The study

This study sought to answer the question ‘what are the teaching and learning experiences of students and teachers preparing a script for external assessment for the NSW Higher School Certificate Drama examination?’2 It focused on and explored the teaching of the short play form – plays that are 15–25 pages in length and that occupy approximately 15 minutes stage time. For this research I used a comparative case study approach studying five school sites and examined the Year 12 students writing a play for their individual project. As these particular drama classes had one student writing a play, the study focused on teacher–student pairs, therefore studying the experience of five teachers and five Year 12 student playwrights. For the purpose of anonymity, the participants are referred to using pseudonyms and the schools are indicated by fictitious acronyms.

The data was qualitative, collected using self-reporting instruments, such as semi-structured interviews and written reflections, and observations of process and product. The teachers and students were interviewed twice, once during and once after the process, with the second round picking up themes from the first. A playwriting mentoring session and play-reading workshop, where possible, were also observed for each school. The plays in draft and final form, as well as the students’ reflective logbooks, were then collected as data for the study.

Emerging findings – the noble savage

Initially, the focus of the research was to investigate the impact of theoretical ideas in the teaching and learning activities on the students’ plays. However, the emerging findings suggested participants, teachers and students, did not explicitly engage with the theory at all. While this lack of theoretical input was acknowledged by the teachers and students, it was often explained as a virtue not an omission. It reflects what I call the assumption of the ‘noble savage’ of playwriting and a distrust of ‘teaching’ or intervention. The image of the noble savage is particularly illuminating for understanding the teachers’ belief that ‘less is more’ in playwriting pedagogy.

The noble savage is a ‘mythic personification of natural goodness’ (Ellingson 2001, 1), before the corrupting influence of civilisation, and represents a rich metaphor for this reluctance to engage in playwriting pedagogy. The concept posits that humanity is happier and morally superior in a ‘state of nature’, free from the sophistications of modern citizenship. Despite the fact this concept has a controversial place in anthropological discourse (see Ellingson 2001), Jackson (2001) argues that Rousseau (among others) contemplated the noble savage as a ‘thought experiment’ to suggest that ever since the ‘Golden Age’, humanity has been deteriorating. Rousseau’s noble savage was a utopian symbol, a revolutionary ideal to combat absolutist rule and encourage republicanism (Greer 1993, 90). In the context of playwriting pedagogy, there are many interesting parallels. Fear of oppressive reliance on formula or the tainting of individuality by exposure to teaching reflects this belief that naive talent is ‘noble’ and should be kept free from the corrupting influence of theory. Waters (2012) calls this the ‘myth of the natural playwright’, one who ‘doesn’t need to read or think much about what they do because their plays ooze out of them effortlessly, like sweat from a pore’ (6). This view reflects some teachers’ understanding of creativity and the belief that creative tasks require minimal intervention to protect the students’ natural voice. It refers to the teachers’ views on what is possible or perhaps permissible education for a creative task.

On the issue of what constitutes appropriate pedagogy for a creative task, the literature and research reveal widespread tensions and ambivalence toward the value of teaching the craft. Playwrights and teachers alike express the view that teaching is counter-productive and diminishes the potential and uniqueness of the emerging playwright. Norden (2007) refers to playwrights’ reluctance for writing to be ‘taught’ at all, quoting one writer who warned that ‘creative writing courses damage a distinctive talent’ (646). Herrington and Brian’s (2006) question: ‘Is there a danger that the very act of instruction can, in fact, stifle the creative promise?’(viii) suggests the view that teaching corrupts rather than edifies. Despite their employment in key tertiary education faculties, a number of American playwrights express reluctance to instruct students in the craft: Tony Kushner expresses a vehement disdain for academic teaching, arguing that ‘no one needs to spend four years learning how to write a play. What you need to learn you learn by doing, and talent and application and luck take care of the rest of it’ (Herrington & Brian 2006, 137). While he encourages extensive reading of plays and theory (144), the focus for learning the craft should be to ‘write plays that are meant to be produced, rather than [writing] plays that satisfy assignments’ (138). Maria Irena Fornes explains that one goes to workshops to write, not to talk or learn (15), and Rivera argues that, as a teacher, you can’t improve or generate talent (Herrington and Brian 2006, viii). Mac Wellman suggests ‘there are no rules’ (Herrington & Brian 2006, 98) supporting Hwang’s position that you are either a playwright or you are not (viii). In practical terms teaching and learning, in the playwriting context, has been strongly influenced by the associated beliefs that the student, left to their own devices, will produce something ‘authentic’ and ‘true’, and that intervention will dilute their natural voice. And it is believed that the playwriting ability is a gift, something you are born with, that makes interventionist teaching seem redundant or damaging.

The teacher and the Muse

The fear that teaching limits, rather than develops a playwright, ignores the benefits of knowledge to creativity. It appears to have been influenced by a conception of creativity based upon a belief in the Muse, that the best teaching is to get out of the way to provide the opportunity for creativity to be released. As McIntyre (2012) suggests, despite creativity scholarship providing evidence that this popular view is perhaps not valid, respect for both the noble savage and the Muse still prevail.

In the playwriting teaching and learning I observed, there was very little teaching that explicitly covered the theoretical spectrum and, in fact, there was very little generic teaching at all. Most chose to, as one teacher indicated, ‘get them writing so we have something to talk about’ (Mr P from St Anne’s). The teachers’ views on their role suggest – at least at this point in the student’s process – they believe in the noble savage approach. The teachers consider strategies that teach dialogue or character development would ‘quash the student’s original voice and stifle creativity’ (Ms S from GLC). They all define themselves as facilitators and not instructors of playwriting, and see their role as predominantly ‘editing and proofreading.’ A number of teachers explained that the worth of this approach was its ability to nurture student creativity. One teacher, for example, proposes that in ‘these projects, it’s a kind of creative impulse that has to be just shaped and refined. I think that is my job: the shaping and refining in that editing process’ (Ms S from GLC).3 This process generally takes the form of ‘negative instruction’,4 where aspects of the play that didn’t work are identified and ear-marked for improvement in the next draft.

In explaining the purpose of input, all but one of the teachers indicated they had no resources, only their ‘understanding and experience of theatre’ (Ms J from St Alexander’s) which resides ‘in their head’ (Mr P from St Anne’s), and that they ‘garner the little bits that might be useful out of my encyclopedia of stuff [in my head]’ (Ms S from GLC). The main approach is to direct students to read plays and produce drafts that the teacher would then annotate. This approach is specifically adopted because it is thought to be the best way to nurture the student’s talent and to work ‘organically’ with their creative ideas. What was interesting about this approach was the absence of evidence that the students had read any plays during their preparation. Some had read none, and of those who had read plays only one went beyond the one or two examples given to them by the teacher.

Another significant theme that emerged was concerned student engagement with the process and with their play. A number of the students began with great enthusiasm, a desire to take risks and create challenging theatre. Many students clearly expressed their engagement with a process that was so creative it was ‘unschool’ (Phillipa from St Anne’s) and a ‘rejuvenating distraction’ from their other HSC work (Sam from St Alexander’s); expressing enthusiasm for a task that gave them complete freedom and autonomy (Sarah from GLC). However, and perhaps surprisingly considering the rationale of their teachers’ approach, the students became, to varying degrees, disengaged with the teacher and/or the project. At worst, some students became anxious, paralysed and/or blasé over the course of the process, with this disengagement leading to feelings of diminished ownership. Unfortunately, as engagement and ownership decreased, students became exam-results focused and were more likely to ask the teacher to ‘now tell me what to do to get the best mark’. Similarly, near the end of the process, the teachers were finding themselves providing more precise and prescriptive feedback to find solutions to the problems they had identified.

This tension, between the identified problems and the student paralysis, and between the impending deadline and the unfinished product, had a significant impact on the teacher–student dynamic. It raises the question of what teaching means in this context. It also questions the effectiveness of the noble savage assumptions in enabling the student to reach their potential. The research sought to examine the relationship, if any, between the noble savage approach and the students’ inconsistent engagement. My research suggested that these themes may be connected and that there may even be a correlation between the ‘negative instruction’ (Selden 1946) approach and the observed decrease in engagement. As the rationale behind this approach is to respect the students’ creativity, current thinking on creativity might shed some light on the experiences of these students and teachers. In particular, the systems’ approach to creativity argues that there is a relationship between creativity, engagement, skill acquisition and knowledge.

Csikszentmihalyi and the flow channel

Csikszentmihalyi’s systems theory of creativity, his concept of flow, and the conditions associated with its occurrence (Csikszentmihalyi 2008) provide evidence for the value of teaching and skill acquisition in creative tasks. As well as linking motivation and talent, and describing moments of extraordinary focus, ‘flow’ can also help us understand more common experiences of productive engagement.

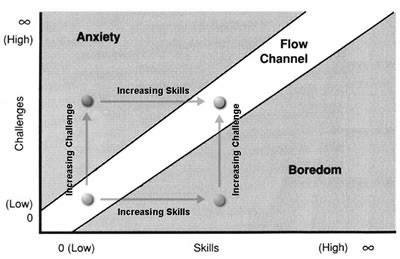

Csikszentmihalyi explains that when the challenge of a particular task is met with a commensurate skill level the individual remains in the ‘flow channel’ (see Figure 6.3), a state of heightened awareness that is characterised by, among other things, a focus on a clear goal, a sense of control and a diminishing awareness of time passing. This experience is so enjoyable that the task becomes ‘autotelic, that it is worth doing for its own sake (Csikszentmihalyi et al. 1993, 15) and encourages repetition (Csikszentmihalyi 1993, 39). Thus flow may be seen as the ultimate example of intrinsic motivation (Csikszentmihalyi 2008).

The key relationship is that to achieve flow and creativity we require an optimal match between skill and challenge. This is a dynamic process, that pushes people to higher levels of performance (Csikszentmihalyi 2008). As he explains further;Flow leads to complexity because, to keep enjoying an activity, a person needs to find ever new challenges in order to avoid boredom and to perfect new skills in order to avoid anxiety. The balance of challenges and skills is never static. (Csikszentmihalyi et al. 1993, 15)

This concept is particularly valuable for our understanding of self-directed learning for all students, not only those working on a play. For a student to engage – and then maintain that engagement – in a creative and challenging task, the skill level must continue to match the increasing challenge. This idea is reiterated by Starko who argues that ‘if insufficient skill development precedes a challenging, potentially creative activity, it is likely to be met with frustration and resistance’ (Starko 2005, 374). These last two concepts are key as they describe the experience of many of the students in my study who began with enthusiasm but lost focus, and became frustrated and resistant. They also exhibited paralysis and anxiety, responses found outside the flow channel. Perhaps an explanation is that the students ‘fly up’ out of the channel when the task presents a greater challenge than their skills can handle.

Students begin with an idea an initial kernel of creativity, that needs craft or aesthetic control to actualise. They need to know how to make their idea theatrical: how to manipulate the elements of drama to make it engaging, and how to create metaphor using theatre semiotics, with its signs and common language, to communicate to the audience. As Anderson suggests, our job as drama educators is to ‘make the mysterious knowable, but more than knowable: it is to create a structured understanding of . . . aesthetics and to allow students to use that aesthetic to create their own work’ (2012, 53). So how do we do that? What is the role of the teacher in enabling students? To answer that question, let’s consider the focus of our efforts – the student.

The student playwright

In the interviews with teachers and students it is made clear that there are three distinct and interrelated aspects or components of the ‘playwriting student’, and that these work together to enable the student to write their play. Using these component parts I will explore what teachers can meaningfully and effectively do in this process of facilitation. In short, teaching should occur within the role of support to ensure that the student realises their true potential and that their creativity is nurtured with knowledge and empowered by skill.5

The first component is what I call the student’s global understanding of theatre, developed from their experience of the performed and written script, and their knowledge and skills developed in the drama classroom. This is their ability to read and understand theatre and drama, and their ability to express that understanding. This is the most easily identified aspect, and is referred to by a number of the teachers in the study as being the foundation of any playwright. Specifically, from the teachers’ perspective, this global view is established through watching theatre being performed. A number of teachers mentioned the students’ exposure to theatre as key to their understanding of how to write a play (Mr P from St Anne’s and Ms S from GLC). In terms of the student participants in my research, on the whole the students had quite well-developed appreciating skills. Most were able to discuss the plays they had seen or read with, at times, sophisticated theatre literacy and insight.

The next two components are closely interlinked and it is here that opportunities for skill and knowledge development are yet to be fully realised. The second aspect I have termed their ‘creativity’, that is the idea or concept put forth. Developing the vision of the play, the ideas to be explored, the world the students want to create and the impetus for writing is a process, and one that can be actively taught. The third aspect is their playwriting skills or understanding of the language of plays or theatre semiotics. The ability to think metaphorically, and to develop an idea and transform it into motifs or symbols, is a skill that enables the students to turn their idea or vision from a concept to a performable text. It involves the students knowing how to control the elements of drama in the temporal reality of the stage: dialogue, setting, suspense, subtext, conflict, complications, relationships.

An understanding of the relationship between these three components is important in recognising the teachers’ role in the creative process. Amabile (1996) describes three necessary aspects for circumstances to be conducive to creativity – task motivation, the domain of relevant skills and creativity-relevant processes. The focus now turns to what strategies teachers can use to improve both domain of specific skills and creativity processes.

As Csikszentmihalyi (2008) suggests, it is the students’ increasing skill that will allow them to attain flow, achieve autotelic motivation, and enable them to meet the challenge of the task. In this section I argue that a student’s playwriting skill can be explicitly taught and developed through understanding of the semiotics of the stage. In turn, there is evidence to suggest that this increased skill will also feed their creativity and open them to new forms of expression.

Semiotics and creativity

As the dramatic text makes use of ‘verbal . . . visual and acoustic codes’ (Pfister, 1988) a strong ‘dramatic literacy’ or ability to ‘speak’ the language of the stage is necessary to equip the students with the skills to write. This literacy, like language, is more than appreciating theatre – the realm of the global understanding – but involves being able to ‘code’ their own ideas to be read and understood by others. Learning to understand and manipulate ‘imaginative shorthand’ (Smiley 2005, 160), the signs and symbols that constitute stage language, will give the students a greater vocabulary and aesthetic control. To achieve this, teachers may need to extend their teaching and learning activities in their playwriting classroom to more closely resemble their normal drama classroom. They need to go beyond suggestions of plays to read, to the explicit deconstruction of plays and genres – to see ‘how’ meaning is made in a variety of contexts and world views, and explore experimentation with these forms before a student emotionally commits to an idea. While this is a slight change in focus it could result in significant improvements in the students’ independence in the process. To provide the students with tools for theatrical thinking and expressing, the playwriting teacher will need to teach the meanings of these codes, signs, and symbols as part of, not after, the idea-generation phase.

I am arguing that there is evidence to suggest that knowledge improves creativity in much the same way as vocabulary increases thought. In language, the greater number of words you have in your bank, the more diverse and sophisticated your thinking can be, to quote Wittgenstein, ‘the limits of my language means the limits of my world’ (Wittgenstein 1922). As Nicholson (1998) argues, greater knowledge of the theatrical codes will give the students an ‘expanded cultural field’ and thus opportunity for thought previously ‘inconceivable’. As students gain new modes of expression, Nicholson argues, ‘this will not only extend their creativity, it will enhance their conceptual development’ (1998, 79). Rather than corrupting the students’ voice, as the noble savage concept supposes, knowledge of a wide variety of styles, techniques and conventions (as tools to be employed, not rules to be obeyed) should be enabling.

A writer needs to understand the ‘old’ to reinterpret it to make something new. As Gombrich (1966) argues, each ‘work is related by imitation or contradiction to what has come before’ (3). Kushner concurs: ‘by all means . . . invent something new, but know where you are coming from, who built the stage you walk out onto’ (Herrington & Brian 2006, 146). As does Waters: ‘No one since Aeschylus wrote a play without seeing or reading another one’ (2012, 5). This emphasis on continuity reinforces our need to reject the belief in the mystical Muse and recognise that creativity requires structure and methodology; that ‘the intangible creative state requires order so that the artist may then put form to his vision’ (Hardy 1993, 67).

Role of the teacher

How then should a teacher approach this refocusing of the teacher–student dynamic? To enable the ‘refocus’ the teacher may need to rethink their role. The majority of the teaching input in the classrooms I studied took the form of ‘negative instruction’ (Selden 1946) where the students submit drafts and the teacher critiques their work ‘finding faults to be rectified’. This problematisation approach, while necessary at times, must be handled skilfully, as it has the potential to create an unproductive dynamic. Starko (2005) describes two types of feedback: controlling, which positions the teacher as arbiter of good and bad, and informational, which encourages autonomy, gives information on what is successful and provides gauges for self-assessment. Problematisation is therefore most effective in the context of greater input – which challenges the noble savage approach to pedagogy. If the student perceives the teacher as the ‘critic’, the students then see the teacher as the one who can tell them what is wrong with their play and how to fix it. Furthermore, if the majority of feedback takes the form of annotated drafts, rather than discussion after workshop performances, then the primacy of the teacher is reinforced. My suggestion is that we need to rethink the relationship, and rather see our role as a dramaturg, one who can build the potential, identify possibilities, and not merely one that highlights flaws. The play should then not be problematised but analysed. As Smiley (2005) elaborates, analysis means separating the whole into parts and studying those parts and their relationships, whereas criticism frequently amounts to adverse commentary regarding faults and shortcomings.

The practice of playwriting instruction would be improved if problems and strengths were identified in a moved reading so the student had an opportunity to see what was and wasn’t working, and can receive feedback from the audience and the teacher. This situation allows the teacher to be an expert advisor, but not the sole arbiter of the play’s success or failure. The distinction here is an important one and is explained best by thinking about where the teacher is positioned. Where does the teacher ‘sit’ in the theatre when they engage with the play, in the audience as a critic or backstage with the writer?

In terms of flow, identifying problems within the text without providing the input that would allow students to solve these problems, does not provide the students with the opportunity to develop the skills needed to meet the increasingly complex challenge of playwriting. ‘Problematisation’ then works to focus students on what they can’t do or haven’t done. In my research, a number of students ‘flew out’ of the flow channel as the challenge outstripped their skill, and thus disengaged from ownership of the task. As the deadline approached, the students began to rely more heavily on teacher input implicitly and explicitly requesting specific suggestions for improvment. Given the problematisation dynamic that had been established, many of the teachers found themselves having to be more direct in the offering of solutions to the problems they had themselves identified (Ms S, Mr P and Ms J). This situation is not satisfying for the teacher or the student, and may go some way to explaining the trepidation felt by teachers.

While some problematisation is often unavoidable, an approach which in more time is spent working with the student to develop a theatrical idea before the first draft and to equip them with the semiotic language of the stage as they develop their vision, could minimise the paralysis and provide the student with the skills to experiment with form and the theatrical devices to improve their piece. A response to these issues is one of refocusing. The role of the teacher could be more effective with a focus on dramaturgy not criticism, and on teaching students the craft of playwriting through semiotics and genre study. Subsequently, we need to rethink the wisdom of the noble savage model of creative mentoring, as this idea paradoxically limits the student’s ability to reach their potential.

Implications for policy and further research

The benefits of playwriting go beyond the confines of the drama classroom. There is emerging evidence that playwriting programs are uniquely placed to provide authentic and engaging opportunities for the development of literacy skills (Chizhik 2009; Gardiner & Anderson 2012) and that students, particularly marginalised students, experience increased feelings of efficacy (Feffer 2009) and inclusion (Fisher 2008). However, as the evidence emerges of the need to embrace the art form and capitalise on the pastoral and theatrical benefits it promotes, it is clear that many drama teachers are avoiding teaching the craft because of its perceived difficulty.

This chapter has provided evidence that a renewed focus on teaching and learning, and a new concept of creativity, could address the factors that have contributed to disengagement in students and feelings of inadequacy in teachers. This approach, which goes beyond the noble savage paradigm, could lead to a more enjoyable and rewarding experience for both, where teacher and student achieve greater proficiency. This also draws attention to the need for more professional learning in playwriting teaching, for both pre-service and experienced teachers. It is vital to ensure a sustained culture of performance writing in schools, and for the future of Australian performance writing. But it is more important to provide an engaging and realistic writing experience for students to have their voices heard, and to encourage diversity and democracy of these voices, both in content and form. While more research is needed, the emerging findings from my study suggest that playwriting is uniquely placed to provide that avenue. However, as the original provocation of this chapter suggested, more research is needed to determine the best playwriting approach for each stage of learning – from preschool to pre-service teachers.

Conclusion

As we are simultaneously teaching the rules and encouraging innovation, drama teachers need to adopt a pedagogical approach that takes account of the spectrum of theoretical approaches for two main reasons. Firstly, it will extend the students’ understanding of what a play can be and broaden their semiotic vocabulary, which has the potential to encourage creativity and innovation in their writing. Secondly, it will broaden the teachers’ view of what a play is, and should equip teachers with the skills to identify innovation and encourage individual voice, rather than restrict the student’s voice by applying generic categories.

Developments in playwriting and creativity theory suggest that the imagination needs structure (Hardy 1993), and that the more students know about the semiotics of playwriting the more creative they will be (Nicholson 1998). The current approach, that minimises teaching activities and focuses on problematisation, has the potential to stifle rather than unleash the unique voice of the student playwright. It is also clear that playwriting pedagogy has much to learn from creativity theory, especially the flow experience, which could have a significant positive impact on the way we teach playwriting in the classroom. The refocusing of the student–teacher dynamic, from critic to dramaturg, could see a much more rewarding experience for both teacher and student, resulting in more autonomy in the student and a more satisfying teaching experience for the teacher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and thank Michael Anderson and Kelly Freebody, my doctoral supervisors, for their guidance and assistance in the preparation of this chapter.

Works cited

Amabile TM (1996). Creativity in context. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Anderson M (2012). Masterclass in drama education: transforming teaching and learning. London: Continuum.

Aristotle (1996). Poetics. M Heath, Trans. London: Penguin Classics.

Castagno P (1993). Informing the new dramaturgy: critical theory to creative process. Theatre Topics, 3(1): pp29–42.

Castagno P (2001). New playwriting strategies: a language based approach to playwriting. New York: Routledge.

Catron LE (2002). The elements of playwriting. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Chizhik A W (2009). Literacy for playwriting or playwriting for literacy. Education and Urban Society, 41(3): pp387–409

Csikszentmihalyi M (1993). Activity and happiness: toward a science of occupation. Occupational Science: Australia, 1(1): pp38–42.

Csikszentmihalyi M (2008). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Csikszentmihalyi M, Rathunde K & Whalen S (1993). Talented teenagers: the roots of success and failure. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Edgar D (2009). How plays work. London: Nick Hearn Books.

Egri L (1960). The art of dramatic writing. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Ellingson T (2001). The myth of the noble savage. Berkley: University of California Press.

Esslin M (1965). Introduction. In M Esslin Absurd drama (pp7–23). London: Penguin Books.

Feffer LB (2009). Devising ensemble plays: at risk students becoming living, performing authors. English Journal, 98(3): pp46–52.

Fisher MT (2008). Catching butterflies. English Education, 40(2): pp94–100

Freytag G (1900). Technique of the drama: an exposition of dramatic composition and art. EJ MacEwan, Trans. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company.

Gardiner P & Anderson M (2012). Can you read that again? Playwriting, literacy and reading the spoken word. English in Australia, 47(2): pp80–89.

Gombrich EH (1966). The story of art. London: Phaidon.

Greer S (1993). The noble savage. Winds of Change, 8(2): pp89–92.

Hardy J (1993). Development of playwriting theory: demonstrated in two original scripts. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University.

Herrington J & Brian C (Eds) (2006). Playwrights teach playwriting: revealing essays by contemporary playwrights. Hanover, NH: Smith and Kraus.

Jackson M (2001). Ter Ellingson. The myth of the noble savage. Utopian Studies, 12(2): pp292

Jensen J (1997). Playwriting quick and dirty. The Writer, 110(9): pp10–13.

McIntyre P (2012). Creativity and cultural production. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

McKean B (2007). Composition in theatre: writing and devising performance. In L Bresler (Ed.) International handbook of research in arts education. Dordrecht: Springer: pp503–15

Nicholson H (1998). Writing plays: taking note of genre. In D Hornbrook (Ed.), On the subject of drama. New York: Routledge: pp73–91

Norden B (2007). How to write a play: or, can creative writing be taught? Third Text, 21(5): 643–48.

Pfister,M (1988). The theory and analysis of drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Selden S (1946). An introduction to playwriting. New York: F S Crofts and Co., Inc.

Smiley S (2005). Playwriting: the structure of action. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Starko AJ (2005). Creativity in the classroom: schools of curious delight. 3rd edn. Mahwah, NY; London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stephenson H & Langridge N (Eds) (1997). Rage and reason: women playwrights on playwriting. London: Methuen Drama.

Waters S (2012). The secret life of plays. London: Nick Hern Books.

Waxberg CS (1998). The actor’s script: script analysis for performers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Wittgenstein L (1922). Tractatus logico-philosophicus. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

2 The HSC course is studied over four terms and represents the final year of study in NSW schools. The course has three components: the written paper (40 percent), the group performance (30 percent) and the individual project (30 percent). For the individual project, students can choose from a range of areas, such as critical analysis, design, performance, scriptwriting and video drama, and the project is marked as a process internally in the school’s assessment program and externally by HSC examiners.

3 It must be noted that many teachers expressed their assumption that if students have chosen playwriting for the HSC they should already know how to do it. A number of the teachers had playwriting units in the Stage 5 program to give them the skills to write a play. While there is merit in that approach, many in the small cohort involved in the study had chosen playwriting because they were not ‘performers’. They were not keen playwrights and while they may have completed the earlier classwork, it became evident that they were not in possession of these skills.

4 This concept, coined by Samuel Selden in his Introduction to playwriting in 1946, has influenced playwriting pedagogy ever since.

5 These component parts somewhat mirror the three sections of the marking guidelines for the scriptwriting individual project devised by the Board of Studies and applied to the plays submitted by the student. I would like to think that that is not coincidental.