7

The drama of co-intentional dialogue: reflections on the confluent praxis of Dorothy Heathcote and Paulo Freire

The drama of co-intentional dialogue

Dorothy Heathcote (1926–2011) and Paulo Freire (1921–1997) were generational contemporaries. The learning and teaching propositions that they developed and championed were truly revolutionary, for both called into question the efficacy of transmission pedagogy as the prevailing orthodox for teaching practice. Even when inquiry methods began to gain favour in Australian tertiary faculties of education during the 1970s, the epistemological propositions put forward by Dorothy Heathcote and Paulo Freire retained their unique resonances as counterpoint perspectives which resolutely placed the student’s ‘thought-language-context’ (Freire 1998a, 141) at the centre of every educational project. In taking this approach both emphasised very concrete, practical means by which teachers could – and should – reframe the learning encounter in order to privilege democratic values and directly share the ‘power to tell’ (Heathcote 1984f, 164) with the learner-participants by actively working to resolve what Paulo Freire called the ‘teacher-student contradiction’ (1994b, 53–56).

In making their pioneering innovations during the 1950s and 1960s both Heathcote and Freire used their academic appointments within universities and other institutions as a base from which to test their ideas and share their insights with local educators. Their approaches represented serious challenges to the comfortable assumptions of transmission pedagogy, and gained national, and then international attention as each conducted workshops and seminars, and began to publish papers that put forth compelling propositions for problem-based approaches to learning and teaching. These efforts had a snowball effect that eventually brought their ideas to a vast international audience. Both Freire and Heathcote made their first visits to Australia during the mid-1970s. Their international audience of educators grew to include professionals drawn from many other disciplines, and in time, the growing appreciation of the potency and originality of their epistemological propositions began to attract commentary that sought to explain why, and explore how, these propositions represented such a radical departure from not only transmission pedagogy, but inquiry methods as well. The discussion offered here reflects upon the state of our art by presenting aspects of that debate to a new generation of Australian educators who did not have direct access – as students – to either of these individuals, but who nevertheless have an to opportunity to encounter them in a direct way through their video recordings and written texts, as well as through the testimony of those who seized the opportunity to undertake a period of study with them.

Assessing the current state of any social movement offers a Janus-like moment in which we can pause to look both backward and forward in time. In doing so it becomes possible to notice that different generations undertake different types of tasks. Often these are most clearly perceived in the rear vision mirror of history, but sometimes these tasks are well understood by those who collaborate to accomplish group-defined goals. The generational task of those Australian drama educators who have recently retired or are now moving toward the conclusion of their working lives was to create the different state-based drama curricula and establish state and national organisations to serve as vehicles for political advocacy and as a means for enhancing communication amongst and between Australian teachers and like-minded colleagues overseas.

Yet further tasks remain. One of these is to develop a more comprehensive account of the epistemological schemes that animated the desire to engage in this particular form of ‘cultural action’ (Freire 1972a, 76–77) by identifying and reassessing the philosophical influences that informed and motivated the development of the drama in education movement in Australia. This is a task for contemporary theorist/practitioners. How did influences drawn from educational philosophy and educational psychology resonate with a growing awareness of the works of Peter Slade, Brian Way, Richard Courtney, Gavin Bolton or Dorothy Heathcote? The analysis offered here explores how Dorothy Heathcote’s approach to drama in education parallels and exemplifies the central epistemological ideas articulated by Paulo Freire. Drawing attention to their syncretic propositions is intended to initiate discussion about the relation between larger international discourses and the works of drama in education practitioners, whose insights influenced the development of drama curricula and theatre in education practice in Australia.

Much has been written about how drama-based learning and teaching might be transacted. Likewise, much has been published concerning what should be taught in terms of syllabus selection. Finding satisfactory answers to these questions were – and are – essential to establishing and sustaining the vigour of well-designed drama curricula and progressing the ongoing debate about curriculum development among the membership of our state and national organisations.

A consideration of why the dimension of the issue has produced landmark studies (Little 1983; Schaffner 1986; Carroll 1980, 1986b, 1988) that offered quantifiable research conclusions, that demonstrated that language use within the ‘drama framework’ (Carroll 1980, 20; Heathcote 1984f, 168) produces new types of learning when compared to more traditional classroom interactions. Here neither the teachers nor the students alter their normative social roles in order to reflect upon learning content by thinking and speaking from the worldview of assumed fictional roles. The focus of this inquiry lies in drawing attention to the ways in which Dorothy Heathcote’s process-driven approach to learning and teaching – through the use of ‘teacher in role’ and ‘mantle of the expert’ drama – exemplifies Paulo Freire’s conceptualisation of the conscientisation process (conscientização).

An epistemological proposition

We are really asking an epistemological question when we inquire into the ways in which conventional approaches to teacher–student communication are altered when in-role communication is used to contemplate, examine, and decode dramatic ‘role conventions’ (Heathcote 1984f, 166–67). The use of full role, attitudinal role and secondary role conventions calls upon students to interrogate different types of information about learning content from a point of view that is quite different from those which they typically experience in either transmission-oriented or inquiry-based classrooms. That is, we are asking, what is ‘the nature of the relationship between the knower (the inquirer) and the known (or knowable)’? (Guba 1990, 18). The Greek linguistic roots for ‘epistemology’ reveal nuanced shades of meaning that remain embedded within the modern word, and these are worth (re)considering:

episteme knowledge, understanding, from epistanai, to stand upon, understand: epi– upon + histanai, to stand, place. (Morris 1970, 441)

It is in this foundation-like place to stand upon – in order to gain understanding – that we should consider the epistemological assumptions which guide a dialogical, problem-based approach to nurturing educational environments, in which the growth of a ‘critical being’ (Barnett 1997, 103) becomes possible as we labour to design sturdy yet responsive structures for learning through the use of in-role communication with our students.

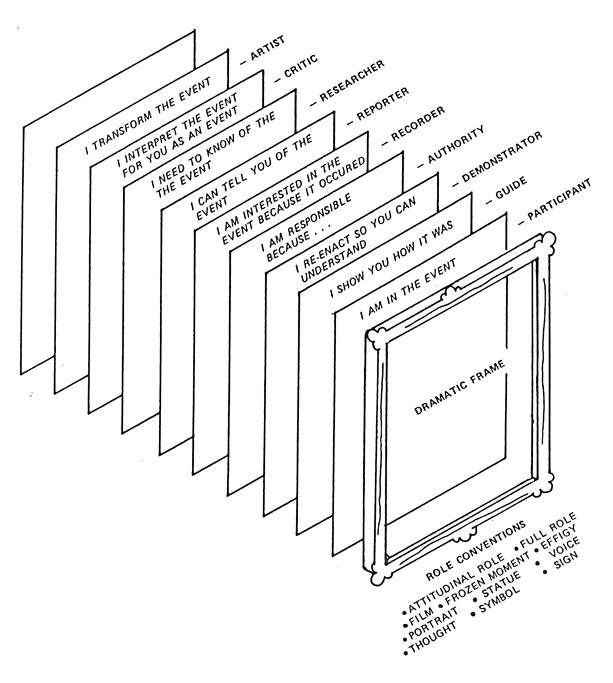

These possibilities are succinctly presented in John Carroll’s important illustration (Figure 7.1), which depicts how different role positions work to establish varied points of view, providing both ‘distance’ and ‘protection’ in relation to how a dramatically framed event can focus the attention of the learner-participants upon new types of inductive learning.

Figure 7.1 Role distance (Carroll 1986a, 6; 1986b, 125)

This orientation around inductive learning arises precisely because ‘role-shifted discourse’ enables the participants ‘to take control of the [drama-based] interaction through their language initiatives’ (Carroll 1988, 20). It is in this sense that ‘role-shifted discourse’ presents new epistemic opportunities and questions about the relationship between ‘the knower’ and ‘the known’, which can be ‘framed’ and ‘reframed’ (Goffman 1974; Heathcote 1984f) according to the choices negotiated and adopted by the teacher in dialogue with the learner-participants.

Our place to stand – our vantage point from which to work with students so they might gain an understanding of using performative, role-based communication, for engaging with any curricular content – cannot be located solely within the normative processual practices of either transmission or inquiry-based pedagogies. For both transmission and inquiry orientations tend to place the control of the pace of the learning, and especially the motivating locus of authority, with the teacher.

Drama teachers know that working in-role from within the ‘drama framework’ specifically empowers them to temporarily set aside the normative expectations that students project upon them concerning the notion that they – as teachers – would (naturally) know the answers to the questions that the students might put to them, or that they would (naturally) know the answers to all the questions which they might put to the students (see Heathcote 1984b, 85–87). Interacting with students from within the ‘drama framework’ enables teachers to select roles that position themselves with a low status and limited authority, or roles that might plausibly exhibit a distinct lack of information or knowledge concerning the questions which confront the students as they attempt to solve those issues from the point of view of their assumed roles.

The act of assuming a fictional role re-frames the participants’ normative expectations concerning their relationship with the subject content under investigation, as well as with one another and their teacher within the learning and teaching encounter. The ‘drama framework’ reorders the status and authority of their actual social roles as teachers and students (Heathcote 1984f, 161–65) by requiring the learner-participants to solve the problems and questions which attend those issues in ways that are consistent with, and relevant to, the ‘dramatic pretext’ (O’Neill 1995, 20) of their in-role interactions with one another. For these fictional challenges exist to authenticate a situated, depictive context that can enable the learner-participants to generate – and test – the new knowledge that they are called upon to inductively reason in consequence of the ways in which ‘mantle of the expert’ drama (Heathcote 1984a, 205–7) supports and facilitates their use of both in-role and out-of-role dialogue to resolve the ‘dramatic tension’ (Heathcote 1984e, 130–31) and dilemmas that have been introduced and developed by their interactions with one another. And, significantly, their ‘role-shifted discourse’ concretely demonstrates that the ‘drama framework’ can be a very effective means of resolving many of the negative effects that accrue from what Paulo Freire characterises as the ‘teacher–student contradiction’ (1994b, 53–56).

Drama practitioners – as teachers who use different types of dramatic activity such as exercise, dramatic playing and theatre (Bolton 1979, 2), as well as different styles of process drama (O’Neill & Lambert 1982; O’Neill 1995; Bolton & Heathcote 1999; Neelands & Goode 2000) to teach any curriculum content – will recognise and understand why Paulo Freire avers that:

Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world . . . this movement from the word to the world is always present; even the spoken word flows from our reading of the world. In a way, however, we can go further and say that reading the word is not preceded merely by reading the world, but by a certain form of writing it or rewriting it, that is, of transforming it by means of conscious, practical work. For me, this dynamic movement is central to the literacy process . . . Words should be laden with the meaning of the people’s existential experience, and not of the teacher’s experience . . . (Freire & Macedo 1987, 35)

My proposition is that Freire’s perspectives concerning the ways in which cultural literacies are developed by ‘reading the world’ and ‘naming the world’ (Freire 1994b, 69) are highly relevant to the ways in which drama teachers can reflect upon their lesson planning. This is never more apparent than when we choose to employ Heathcote’s ‘role conventions’ (1984f, 166–67) as embodied forms of selective ‘signing’ to reframe the social context for learning and teaching as an ‘intersubjective’ (Freire 1998a, 136) opportunity for ‘role-shifted discourse’ within our classrooms.

We would do well to recognise that the ‘role conventions’ that Dorothy Heathcote enumerated in Signs and portents (1984f, 160–69) represent what Paulo Freire’s called ‘compound codifications’ (1994b, 104; 1972a, 32). His advice is to employ ‘compound codifications’ that will function as the central value/means for guiding and sustaining a deepening the dialogue on the part of learner-participants in wanting to solve realistic problems that enable them to use their knowledge for those situated purposes. As Freire observed, ‘it is to the reality which mediates men, and to the perception of that reality held by educators and people, that we must go to find the program content of education’ (1994b, 77). So let us now dig a little deeper into Paulo Freire’s thinking about the nature of what a ‘conscientising praxis’ means within the context of the learning encounter. In particular, by examining how the characteristics that define the phases of his conscientização process are present within Dorothy Heathcote’s approach to drama in education, and how both offer guidance for drama teachers who wish to utilise ‘problem-posing’ questions (Freire 1994b, 60–64) as the principal value/means for facilitating dialogue with students in order to critically interrogate curriculum content while developing their individual analytical and improvisational skills, and their group work skills.

Agents of their own learning

‘The starting point for organising the program content of education’ says Paulo Freire, ‘must be the present, existential, concrete situation, reflecting the aspirations of the people’; and one which uses ‘the thought-language with which men and women refer to reality, the levels at which they perceive that reality, and their view of the world, in which their generative themes are found’ (1994b, 77–8). His comments about ‘the starting point’ for learning and teaching emphasise his uncompromising adherence to the epistemological value(s) of student-centred education, for his ‘problem-posing’ approach to dialogue empowers the participants to engage a group-defined ‘educational project’ (1994b, 36) that takes their ‘thought-language’ about their ‘situationality’ as the starting point. ‘Reflection upon situationality’ he says, ‘is reflection about the very condition of existence: critical thinking by means of which people discover each other to be “in a situation” ’ (1994b, 90).

The key to understanding the conceptual links between Paulo Freire’s conscientização process (1973b, 23; 1998a, 49–52; 1996, 127–34) and Dorothy Heathcote’s approach to drama in education lies in their procedural orientation toward privileging ‘co-intentional’ ‘problem-posing’ dialogue within the classroom (Freire 1994b, 51, 53). Both emphasise the need to investigate the ‘thought-language-context’ (Freire 1998a, 141) of the learner-participants and then honour their input by ‘putting the students’ point of view to work’ (Heathcote 1984d, 44). Both Heathcote and Freire insisted, and consistently demonstrated, how the learning encounter needs to be constructed around the ‘thematic universe’ (Freire 1994b, 90) of the learners who simultaneously engage with the teacher to enlarge and transform their understanding of the drama-based project of the moment, or the socio-historic dimension of the curriculum content under consideration.

Freire’s epistemological proposition relates to what he called the ‘gnosiological cycle’ of learning, meaning for him ‘the cycle of the act of knowing, the relation between knowing existing knowledge and producing new knowledge’ (Paulo Freire in Shor & Freire 1987, 151). Returning to this topic in his posthumously published book, Pedagogy of freedom: ethics, democracy, and civic courage (1998b), he reminded his readers once again that ‘co-intentional’ education:

requires the existence of ‘subjects,’ who while teaching, learn. And who in learning also teach. The reciprocal learning between teachers and students is what gives educational practice its gnostic character. (Freire 1998b, 67)

The connection between these Freirean epistemic propositions and Dorothy Heathcote’s approach to drama in education – in terms of the ways in which she proposes the use of ‘teacher in role’ and ‘mantle of the expert’ – is that both represent a ‘permanent movement of searching [that] creates a capacity for learning not only in order to adapt to the world but especially to intervene, to re-create, and to transform it’ (Freire 1998b, 66). Considered from this point of view the primary role of teachers revolves around our adroit employment of ‘problem-posing’ dialogue to enlarge the students’ collective capacity to inductively generate new knowledge – irrespective of whether or not that new knowledge represents either discrete or blended expressions of affective, psychomotor or cognitive reasoning (Bloom 1956–64; Anderson & Sosniak 1994).

I turn now to a discussion of the conscientização process in which Paulo Freire’s own voice is foregrounded in order to give a more direct appreciation of how he explained his approach to learning and teaching, and to enable readers to mere clearly perceive the theoretical/ conceptual connections of the conscientisation process with Dorothy Heathcote’s approach to drama in education.

The conscientisation process (conscientização)

The conscientização process is founded in ‘educational projects’ (Freire 1994b, 36) that begin with an investigation of the themes that shape people’s perceptions about the ‘thought-language-context’ of their own life situation (Freire 1998a, 141). The purpose of the conscientização process is to reveal the presence of ‘knowing Subject[s]’ (Freire 1973b, 24) to one another in ways that enable them to perceive their relationships with one another in new, more critical ways, so that – within the drama frame at least – they can act to transform limiting aspects of the situated social context that their assumed roles inhabit (1994b, 80). This requires communication that is formed around modalities of ‘intersubjective dialogue’ (1994b, 116–17; 1998a, 136) that are all too frequently absent from communication between teachers and students in transmission-based classrooms with its emphasis upon procedural information and discussion of objective facts relating to the material world (Carroll 1986b, 206; 1988, 16, 20).

‘It is not our role’ as educators, Freire says:

to speak to the people about our own view of the world nor attempt to impose that view on them, but rather to dialogue with the people about their view and ours. We must realise that their view of the world, manifested variously in their action, reflects their situation in the world. (1994b, 77)

The role of the dialogical educator is, therefore, to investigate the ‘thematic universe’ of the students and then to ‘re-present it not as a lecture, but as a problem’ (1994b, 90). ‘The program content of the problem-posing method’ he says:

is constituted and organised by the students’ view of the world, where their own generative themes are found. The content thus constantly expands and renews itself. (Freire, 1994b, 9)

Or, as Heathcote consistently emphasised over many years, ‘[p]eople have to employ what they already know, about the [fictional] life they are trying to live . . . drama puts life experience to use’ (1984a, 204). Within the ‘drama framework’ people are encouraged and empowered to externalise their own reflections by assuming fictional roles that use symbolic languages to construct embodied codifications which depict their ‘reading [of] the world’. These readings emerge through shared ‘intersubjective’ dialogues that enable the learner-participants within the drama to define and construct ‘compound codifications’ that put their own ‘life experiences to use’ through their depictive actions within the context of a drama (as an enacted episode or exercise-based improvisation). Assisting students to codify the ‘thought-language-context’ of their reflections upon the social reality of their assumed roles enables the learner-participants to reflexively consider their role-based experiences as ‘an object to be thought about’ (Shor & Freire 1987, 40). This activity provides the safety of ‘a no penalty area, using people in groups, in immediate contextual time’ (Heathcote 1984e, 130) in order to consider diverse issues and ethical problems in terms of the viewpoint of the student’s assumed role:

If it is in speaking their word that people, by naming the world, transform it, [then] dialogue imposes itself as the way by which they achieve significance as human beings. Dialogue is thus an existential necessity. And since dialogue is the encounter in which the united reflection and action of the dialoguers are addressed to the world which is to be transformed and humanised, this dialogue cannot be reduced to the act of one person’s ‘depositing’ ideas in another, nor can it become a simple exchange of ideas to be ‘consumed’ by the discussants. (Freire 1994b, 69–70)

This is an important concept in terms of Freire’s epistemological propositions concerning the conscientização process. We teachers work to enhance the learner-participants’ claim on critical and creative agency to define the expressive character of their engagement of drama processes through the different types of ‘co-intentional’ actions/interactions we utilise in order to assist them to identify the ‘significant themes on the basis of which the program content of [their] education can be built’ (Freire 1994b, 74–74). Both Heathcote and Freire emphasise the necessity of investigating the ‘thought-language’ that students use to describe their perceptions of the world because through their very activity in this naming, we begin to humanise the world, so that the collaborative, dialogical activity in the work of this ‘naming’ transforms our perception in favour of seeing ourselves as the subject of the learning and not merely the object of some type of externally defined curriculum outcome. We must not, says Freire, surrender to others the right to name our ‘significant themes’ nor should we cede all decision-making agency by permitting others to define the entirety of the program content of our learning for us.

Critics of such an approach might begin to worry about the program . . . I say to them that I am not against a curriculum or a program, but only against the authoritarian and elitist ways of organising the studies. I am defending the critical participation of the students in their education. (Shor & Freire 1987, 107)

For Paulo Freire, men and women are ‘beings of praxis’ who reveal different modalities of consciousness in their relationship with the social and natural world (1994b, 106; 1998a, 111). ‘Knowing’ he says, ‘is the task of Subjects, not of objects. It is as a Subject, and only as such, that a man or woman can really know’ (1998a, 101). Educators who embrace these epistemological perspectives and ontological values must determine to resolve the ‘teacher–student contradiction’ as a necessary first step in order to alter the power dynamics within the social encounters that occur between themselves and the participants within any learning and teaching interaction that is conducted as an improvisation activity, an episode of process drama, or as a theatre-making enterprise. A ‘problem-posing’ approach to dialogical learning and teaching can be carried out in any educational context, and critical thinking, when expressed as ‘intersubjective dialogue’, will tend to be multidisciplinary.

Dialogue that is conducted with the aim of enabling people to ‘name the world’ (Freire 1994b, 69, 83) works to affirm our shared historical and ‘ontological vocation’ to ‘become more fully human’ (1994b, 26, 55). Freire emphasised this point again and again throughout his life:

When I insist on dialogical education starting from the students’ comprehension of their daily life experiences, no matter if they are students of the university or kids in primary school or workers in a neighbourhood or peasants in the countryside, my insistence on starting from their description of their daily life experiences is based in the possibility of starting from concreteness, from common sense, to reach a rigorous understanding of reality. (Shor & Freire 1987, 106)

Freire and his confederates experimented with an educational innovation ‘which would be the instrument of the learner as well as of the educator’; one which ‘would identify learning content with the learning process’ (1998a, 48–49). The literacy program that Freire describes in the chapter entitled ‘Education as the practice of freedom’ in Education for critical consciousness (1998a), and in chapter three of Pedagogy of the oppressed (1994b), concerns the activity of teams of educators who enter local communities in order to discover the thematic concerns of the adult students who will participate in the literacy program. In doing so these educators begin to understand the ways in which these themes and issues are manifested in the ‘thought-language’ (1994b, 77–78) of people’s daily lives.

The theoretical/conceptual categories for describing the conscientização process are embedded within Freire’s discussion of the phases of conscientização process throughout several of his early books; in particular, Cultural action for freedom (1972a), Pedagogy of the oppressed (1972c), and Education for critical consciousness (1974). Table 7.1 was constructed using insights drawn from an explanatory analysis developed by Denis Collins (1977, 83) and uses Freire’s own writing to clarify and amplify my discussion of conscientisation as a process of investigation, thematisation, problematisation and cultural intervention. It constructs a portrait of what I call the action-progressions of the conscientização process in a way that illuminates Freire’s emphasis on the ‘problem-posing’ dimension of dialogical education in terms that are integral to both his own adult literacy projects and the conduct of ‘educational projects’ which reflect the process-based insights offered by Dorothy Heathcote’s approach to utilising ‘teacher in role’ and/or ‘mantle of the expert’ drama for learning and teaching.

The principle contribution that Table 7.1 makes to the work of illuminating Freirean epistemology lies in the way in which his concepts concerning the conscientização process are presented in a synoptic fashion that is both simple and direct in its expression. Rendered in this way it becomes possible to hold these guiding principles in mind while collaborating with others to co-intentionally construct new meanings, and define new drama-based applications from the conceptual expressions that Freire used to describe the learning and teaching dimensions of his approach to conscientisation.

Table 7.1 contributes to international discourses concerning Freire and his conceptualisation of the conscientização process because it provides a précis of his learning and teaching process, and underscores the ontological values upon which his central epistemological insights are constructed. Remarkably, this is somewhat unusual in the context of the literature devoted to analysing Paulo Freire’s educational insights, for instead of offering an interpretive commentary on what I believe Freire means, what is offered here is a succinct, closely cross-referenced profile of the language that Freire himself used to explain and define the phases of the conscientização process in terms of the way that it illuminates the role-based innovations in learning and teaching that Dorothy Heathcote pioneered.

What Heathcote understood is that the act of inhabiting a role – as a persona other than ourselves – has the effect of liberating an individual to explore the ‘as if’ realm (Heathcote 1984c, 104) of the ‘subjunctive mood’ (Turner 1982, 80, 82–83; 1990, 11–12). One consequence of working in-role is that participants are released from the pressure to ‘get the right answer’. This is what she meant by the ‘no penalty area’ (1984e, 128–30) of in-role communication in which the participants experience the ‘freedom to experiment without the burden of future repercussions’ (1984c, 104) for this enables them to explore the worldview of others in ways that facilitate the possibility that new insights might emerge through in-role dialogues about ethical questions concerning the ‘socio-historical context of relations’ that lift awareness out of the classroom and situates the participants in a new relationship with one another and with the objects that mediate the learning encounter; what Heathcote calls ‘the other’ (1984f, 162–63). This focus upon ‘the other’ – as Heathcote’s ‘role conventions’ or as Freire’s ‘compound codifications’ – empowers us to collaboratively work with one another in a learning and teaching context that is substantially different from the normative relations that typify interactions between teachers and students when we do not assume fictive roles. For it is this new role-based perspective, in which we operate within a redefined ‘no penalty area’, that enables everyone to ‘become capable of comparing, evaluating, intervening, deciding, taking new direction, and thereby constituting ourselves as ethical beings’ (Freire 1998b, 38). This is especially the case when ‘teacher in role’ is used to provoke and empower both students and teachers to temporarily sidestep the power relationship that operates so strongly in transmission and inquiry classrooms – wherein all participants maintain their actual (real life) social roles as the standpoint from which they speak with one another in classroom communication events.

Implications for drama practice

I confess to a certain reticence in presuming to offer conclusions for my drama colleagues about the ideas presented here. Certainly, these learning and teaching propositions have informed and animated my own teaching practice for over three decades, and I suppose I feel that the conclusions, such as they might be concerning the utility of these concepts, are embedded within your contemplation of the schema offered in Table 7.1.

Yet as I examine these propositions in the light of concepts articulated by the NSW Department of Education and Communities’ ‘Quality Teaching in Drama’ website (1999–2011) I find that Freire’s and Heathcote’s process advice and epistemic value statements to be entirely consistent with the perspectives presented concerning the ‘intellectual’, ‘learning environment’, and ‘significance’ statements1 which characterise the ‘dimensions of quality teaching’. When contrasted with the NSW Quality Teaching Model for developing units and assessment tasks, Paulo Freire’s and Dorothy Heathcote’s epistemological propositions provide very sturdy concepts with which to conduct a deeply theorised reflection on one’s classroom learning and teaching practices.

Drama teachers tend to be in the vanguard of progressive educational practice. Nevertheless, it should perhaps be said that the types of dialogical practice that both Dorothy Heathcote and Paulo Freire advocate not only takes more classroom time and requires us to closely monitor our approach to formulating problem-posing questions, but that this reorientation can present daunting challenges to both early-career teachers as well as to those who feel the accelerating pressure – from whatever source – to achieve high level examination results by their student cohorts. All teachers who are sincerely committed to achieving quality learning outcomes have high expectations and high hopes for the efficacy of their own teaching practice.

These propositions raise questions about how each of us might benefit from pausing to reassess our assumptions about our teaching practice; not only in terms of the NSW Quality Teaching Model but also in terms of how we value and apply concepts of ‘co-intentional’ dialogue and use ‘role-shifted discourse’ to resolve the ‘teacher-student contradiction’ in order to enlarge the student’s ‘power to tell’ through the diverse ways in which our drama-based interactions with them puts the ‘thought-language’ of their ‘life experience to use’. We take this approach because we are interested in expanding possibilities for inductive reasoning so that through their ‘naming’ of the world, they act to ‘transform’ it through depictive dramatic actions which engage them in reflexive dialogical reflections that have the capacity to generate new cognitive and affective understandings about what it means to be human.

Education is a site of cultural struggle; and the ways in which we join ourselves to the task of enlarging possibilities to dialogically express and co-intentionally embody our shared ‘ontological vocation’ of ‘becoming more fully human’ (Freire 1994b, 26, 73) will be defined by the ways in which we, as educators, act to enlarge the ‘pedagogical space’ (Freire 1998b, 64) in which both students and teachers are empowered to express ourselves as we use ‘role-shifted discourse’ to generate new understanding. The NSW Quality Teaching Model provides useful guidance for thinking about how we can act to create ‘pedagogical space’ that will facilitate strong learning outcomes for students through the engagement of drama-based practices that flow from either the new K–6 creative arts curriculum or the current Stages 4, 5, or 6 drama curricula in secondary school settings.

The discussion offered here proposes that the many different forms of ‘role-shifted discourse’ represent a dynamically creative form of ‘cultural action’ that is realised through the determination to democratise social relations by exploring the ways in which the conscientização process can expand opportunities for both students and teachers to develop a shared capacity for expressing creative agency as we engage one another in ‘problem-posing’, ‘co-intentional’ dialogue.

Works cited

Anderson LW & Sosniak LA (Eds) (1994). Bloom’s taxonomy: a forty-year retrospective. Chicago: National Society for the Study of Education.

Barnett R (1997). Higher education: a critical business. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bloom BS (1956–64). Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals. Vol. 1–2. London: Longmans.

Bolton G (1979). Towards a theory of drama in education. London: Longman.

Bolton G & Heathcote D (1999). So you want to use role-play? A new approach in how to plan. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books.

Carroll J (1986a). Framing drama: some classroom strategies. NADIE Journal, 10(2): 5–7.

Carroll J (1986b). Taking the initiative: the role of drama in pupil/teacher talk. PhD Thesis. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: University of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.

Carroll J (1988). Terra incognita: mapping drama talk. NADIE Journal, 12(2): 13–22.

Carroll J (1980). The treatment of Dr Lister. Bathurst: Mitchell College of Advanced Education Press.

Collins D (1977). Paulo Freire: his life, works and thought. New York: Paulist Press.

Freire P (1973a). A few notions about the word ‘conscientisation’. Hard Cheese, 1(1): 23–38.

Freire P (1972a). Cultural action for freedom. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Freire P (1974). Education for critical consciousness. London: Sheed and Ward.

Freire P (1998a). Education for critical consciousness. New York: Continuum.

Freire P (1973b). Education, liberation and the church. Study Encounter, 9(1): 1–16.

Freire P (1996). Letters to Cristina: reflections on my life and work. New York: Routledge.

Freire P (1998b). Pedagogy of freedom: ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Freire P (1972c). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Freire P (1994b). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Rev. edn. New York: Continuum.

Freire P & Macedo D (1987). Literacy: reading the word & the world. South Hadley: Bergin & Garvey.

Goffman E (1974). Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Guba EG (Ed.) (1990). The paradigm dialog. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications.

Heathcote D (1984a). Dorothy Heathcote’s notes. In L Johnson & C O’Neill (Eds). Dorothy Heathcote: collected writing on education and drama (pp202–10). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Heathcote D (1984b). Drama as challenge. In L Johnson & C O’Neill (Eds). Dorothy Heathcote: collected writing on education and drama (pp80–89). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Heathcote D (1984c). From the particular to the universal. In L Johnson & C O’Neill (Eds). Dorothy Heathcote: collected writing on education and drama (pp103–10). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Heathcote D (1984d). Improvisation. In L Johnson & C O’Neill (Eds). Dorothy Heathcote: collected writing on education and drama (pp44–48). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Heathcote D (1984e). Material for significance. In L Johnson & C O’Neill (Eds). Dorothy Heathcote: collected writing on education and drama (pp126–37). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Heathcote D (1984f). Signs and portents. In L Johnson & C O’Neill (Eds). Dorothy Heathcote: collected writing on education and drama (pp160–69). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Little G (1983). Report of the primary language survey 1980 and 1981. Canberra: Canberra College of Advanced Education.

Morris R (Ed) (1970). American heritage dictionary of the English language. New York: Random House.

Neelands J & Goode T (2000). Structuring drama work: a handbook of available forms in theatre and drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

NSW Department of Education and Communities (1999–2011). Quality teaching in drama: drama curriculum K–12 [Online]. Available: http://www.curriculumsupport.education.nsw.gov.au/secondary/creativearts/qualityteaching/drama/index.htm [Accessed 13 June 2013].

O’Neill C (1995). Drama worlds: a framework for process drama. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

O’Neill C & Lambert A (1982). Drama structures: a practical handbook for teachers. London: Hutchinson.

Schaffner M (1986). A matter of balance. NADIE Journal, 11(1): 15–19.

Shor I & Freire P (1987). A pedagogy for liberation. South Hadley: Bergin & Garvey.

Turner V (1990). Are there universals of performance in myth, ritual, and drama? In R Schechner & W Appel (Eds). By means of performance (pp8–18). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner V (1982). From ritual to theatre: the human seriousness of play. New York: PAJ Publications.

1(www.curriculumsupport.education.nsw.gov.au/digital_rev/leading_my_faculty/lo/pedagogy/Pedagogy_pop2.htm)