III

Symbolism in the Higher Rites

1. Levels of Awareness

The Aborigines put no important restraints on what a European may see or do when they allow him to attend the celebration of their religious rites. Perhaps they may ask him to keep his knowledge of the more secret matters from the unauthorised, especially from the women and children, but beyond that there are no impediments. Nevertheless, he is likely to feel for a long time unable to pass beyond the anterooms of meaning, because the rites are made up of an infinitude of symbolisms, most of them obscure, for which the Aborigines make no attempt to account and, if asked to, usually cannot. The usages are time-honoured and evidently well-loved, but their significance arouses no curiosity among the celebrants.

In the circumstances the ‘cake of custom’ of which much was once heard in anthropology might seem to be a reality. But the facts would be misrepresented by any suggestion of mindless automatism, or blind or instinctual following out of a deadened tradition. Nor is there any need to postulate a collective unconscious. One is dealing with a dutiful submission to authority on solemn occasions, and with a rapt absorption in things that have emotional appeal and give æsthetic pleasure.

The young men who are being inducted into the rites are not warned against asking questions. There is no suggestion that they will be put under penalty if they do. A questioning or critical approach would be out of character with the occasion. Those whom I have examined on the matter simply say: ‘We looked, we stayed quiet, we did not ask.’ But there is more to it than that. The older men use many artifices to induce respect and fear. At various junctures the young men are admonished 150to comport themselves modestly and deferentially, and commanded to look carefully at what happens so that, when they too are men of authority and understanding, they will know what to do, and to require their sons to do, to ‘follow-up’. A guardian is always close at hand to see that they conform to instructions. The form and matter of the rites are thus taught, and doubtless are remembered, in a somewhat rote fashion. The unquestioning attitude in this way is passed between overlapping generations.

What happens on such high occasions is also apprehended in a deeper fashion, and the interior life is shaped in a positive way. All the things seen and done have the authority of ancient, sacred ways (maŋe mundak, lit. ‘hand-fashion,’ ‘olden time’). They are also true things (muṙṙin ḍaitpiṙ, lit. ‘words,’ ‘lips’). More, they are good things of the utmost gravity (nandji bata bata, nandji ŋala ŋala, lit. ‘things,’ ‘excellent,’ ‘very heavy’ or ‘very big’). These phrases are commonly used, and every circumstance of context—beauty, drama, excitement, mystery—reinforces them. As well, both young and old, neophytes and instructors, have a lively dread of sanctions of irreverence. It would scarcely be possible to weigh the contributions made by these influences to the attitude of uninquiring acceptance exemplified by the old and emulated by the young. But clearly we are not dealing with a lifeless adhesion to a deadened routine.

It is not particularly difficult to bring the Aborigines to see that many elements of the rites lack explanation. Their response varies from a naїve and somewhat startled surprise to a thoughtful reflection. A means of making them attend to the matter is to build on an example which they themselves see as symbolical. For example, the fact that the bullroarer; in their own words, ‘takes the place of’ The Old Woman, or, as we might say, ‘stands for’ her and ‘points beyond itself’ to her. One may then ask if this is the case with other elements. The inquiry does not lead very far but it helps to adduce some significant details. One comes to two main conclusions. There is a conscious awareness that many elements of the rites designate things of nature. As a case in point, the rhythmic cries that punctuate dances, chants and songs are meant 151to simulate the calls of birds, the sounds of surf, tides and streams, and the winds. The fact is not at all obvious at first, for the cries do not necessarily refer to anything being celebrated in the rites, or stressed in the accompanying mythology. One is left with the impression that the ritual fashions are compound of old and new elements. The second conclusion is unavoidable: there are several levels of awareness of ritual symbolism. A few usages are recognised clearly as being symbolical; a few more, on the whole of minor importance, are demonstrable as such; but the vast majority are practised without clear recognition of their symbolical character. Direct questioning of the Aborigines does little to clarify the matter, and if understanding is to pass this threshold then it must be by other means.

Many anthropologists, confronted by this situation, might feel that they must transpose the study to phenomena of the Aboriginal unconscious. But the symbolisms are constituents of collective acts of mutuality, with a logical structure, a detectable range of meanings, and an æsthetic appeal as well as a premial place in the social development of individuals. These relations may appropriately be studied by the methods of anthropology. The fact that they are perpetuated apparently without the kinds of conscious awareness or rational consideration that might represent them to the Aborigines as things requiring explanation is not in itself a sufficient reason for thinking them beyond the province of anthropological study.

In this article I propose to examine some of them as conventional signs with practical, logical and expressive functions in the symbolical systems of ritual.

2. The Geometric Idiom of Ceremony

The religious rites involve anything from scores to hundreds of men at a place and time. They are all complex sequences of ritual forms in unguided coordination. There is no master of ceremony as such, only a concerting of familiar tasks. One is better able to understand what 152happens by beginning with the morphic aspect, the visual shape of what may be seen.

The celebrants of Murinbata rites arrange themselves in spatial patterns. These have a geometric idiom—arcs, circles or ovals, points and straight and curved lines. Each rite exhibits a somewhat different combination of the same elements. The compositions give an austere beauty to the inactive phases and an excited vitalism to the active phases. In both they are impressive essays in dynamic symmetry and asymmetry.

A knowledge of the patterns is part of the experience of every man; not, as far as I could determine, as the result of special instruction, but because everyone who passes through the rites becomes familiar with them. Certainly, at the celebrations, everyone appears to fall with an easy confidence into place, stance and posture, and to follow out the sequences of what has to be done to a set formulary.

The formulary is well understood. There is no difficulty in obtaining from informants, by the use of tokens or counters, clear rehearsals or reconstructions. The method of study is rewarding in that it reveals aspects of the rites that are all too easy to miss in direct observation. Some Aborigines, without being solicited, will produce graphic sketches of the positions and movements to which the celebrants must conform. The sketches may resemble the patterns incised on bullroarers, a fact deeply significant in itself.

The spatial plans of the rites should not be allowed to pass as commonplaces of a just-so kind. Each of the shapes has to serve as an arrangement of persons forming a conceptual class, each person and class having parts to play that require a sequence of sentiments, purposes and meanings to be expressed by action or inaction. The combination of shapes has to accord with the logic, the economy, and the æsthetic canons of the ceremony. There is in each combination an undoubted structure—in the terms used in earlier articles, a structure of operations—with a kind of praxis by which the symbolisms indicate, represent and communicate the connected meanings which they express in a sequence, as do the ordered words of a sentence.153

My use of the word ‘shape’ may invite remark. I could not discover any linguistic concepts of the patterns or combinations used in different rites, but there are terms for each of the geometric elements that make them up. However, the word ŋinipun is often used of the total patterns, and it can here conveniently be given the meaning of ‘shape’1. To use it comes very close to the Aboriginal convention.

In an earlier article (‘II. Sacramentalism, Rite and Myth’) I put forward the hypothesis that familiar things of the social order provide shapes or ŋinipun by which religious mystery can be formulated in an understandable way. The same intellectual process seems to be revealed in the spatial configurations of ceremony: familiar things of the physical environment provide shapes or ŋinipun for the arrangement of ritual conduct.

I have no direct testimony by the Aborigines to cite as evidence that they wittingly imitate environmental things in their ritual use of geometric shapes, but the indirect evidence of intellectual and æsthetic influence is not unimpressive. (a) They are acute observers of their natural scene and little in it escapes notice, particularly the presence of shapely visual form or pattern. Anything that is symmetrically patterned attracts notice, and the same is true of marked asymmetry. (b) The word diṙmu is applied to a wide range of phenomena: to (i) bodily decorations in dances and mimes, (ii) ancient cave-paintings, and (iii) the spiral, concentric and radial whorls of shells, the segmentation of honeycomb, the divisions of spider-webs, the crystals of rock-minerals, the colour-markings of birds, the skin-patterns of reptiles. (c) The usages of the word diṙmu make clear that it denotes visual form or pattern, and that it implies (i) the consequences of intent or purpose and (ii) the handiwork of beings, or the outcome of events, significant for man. The conception of non-intentional form or pattern seems foreign to the mentality. (d) The elements of diṙmu are geometric shapes and it is to the totality of outward form or appearance resulting from a complex of such elements that the word ŋinipun is applied.

154

Things that to Europeans are ‘natural’ forms are to the Aborigines signs that something happened long ago, something mysterious, and heavily consequential for the human life that is continuous with the form-making events of The Dream Time. The past is the authority and the organon of the ontology. The ‘penetrating, possession-taking faculty’ of Aboriginal imagination sees in each shapely excellence of form a consequence which the mythology and totemism then make into a Gestalt. My hypothesis is that the geometric forms enter the general system of symbolism as conventional signs. Their significance, which is always one of a completed and final action, is a kind of command for an exemplifying action by living men as the appropriate response. The exemplifying is consonant, on the plane of gesture, with the ‘following up’ of The Dreaming on the plane of conscious intent. In our sense ‘natural’ signs that become conventional signs, the given forms are in the Aboriginal world a sort of authority gathered up into general symbolism for logical and expressive elaboration. As signs, they designate and indicate mysterious first things of the long ago, the mythical past; as symbols—that is, when elaborated by language, gesture and music within a system of conduct which is also a system of conceptualism—they express and communicate first things as last, permanent and continuous things.

An anthropologist encounters them as time-honoured elements of systems which are already formed even though, as I have suggested earlier, appearing at the same time to be developmental. In the circumstances, no hypothesis could be brought to ‘proof’; one can but raise probabilities. The logic of present conduct utilising the geometric forms, and their rich expressive elaboration, are both evident in the actualities of rites, of which Punj is the outstanding example.

The principals at Punj cluster for the opening phase in a compact circle. Everyone faces towards the centre. The formation is one in which physical association is intimate. The men sit flank to flank, with knees often crossing, and with arms often flung around the shoulders of neighbours. The kinship and other social categories intermingle without any evident discrimination, except that clansmen often sit close 155together and, likewise, pairs of men who later are to act boisterously towards each other under the licence of Tjirmumuk. While at song, the celebrants vie rather than compete. Some follow the melodic outline while others, without prearrangement, introduce a simple harmony. The men’s faces take on a glow of animation and tender intent. At the last exclamatory cry—Karwadi, yoi!—everyone shouts as with one voice. An observer feels that he is in the presence of true congregation, a full sociality at a peak of intimacy, altruism and unison.

The onset of Tjirmumuk brings a sudden scission. The close circle explodes. The harmony of association disrupts. The men scatter into a new spatial pattern. The solemnity is replaced by ribaldry, the altruism by outward hostility, the solidarity by opposition, and the unison of common purpose by a jostle of similar purposes. But the spatial form is, in a sense, continuous with the old. The celebrants are still a kind of unity. They now act under another principle, from other sentiments, and with a different object. But the changes have the nature of transpositions. An observer has the sense of a negative affirmation of what was affirmed positively in the first phase. It is as though the statement ‘everything that is Karwadi is sacred’ now had the form ‘nothing that is not Karwadi is sacred.’

The circle as a spatial form is suited by nature to the first phases of the rite. It permits an intimacy of face-to-face relations that no other formation can. It is as well appropriate to the logical datum of the rite: that there should be a unison of men in sentiment and object.

The physical gestures of touching, fondling and embracing between the celebrants express the sentiments after a sign-fashion that is universal to men everywhere. The Aboriginal conventions differ only in the classes of persons to whom the signs are made, and in their symbolical conceptualisation.

The conversational exchanges that go on during the intervals between songs exemplify the unison in the symbolism of language. They exhibit the qualities of good humour and tenderness that conventionally characterise relations between intimates, especially between brothers and between fathers and sons.156

The meaning of the songs may be—and usually is—unknown since they, with the dances, come from tribes across the southern boundary of the Murinbata. But the manner of their singing—as with one voice, a harmony being added—reiterates what may be seen on the spatial and gestural planes of symbolism.

Thus, the circle reduces to a minimum the social as well as the physical separation between those who make it up: for a time it makes inappropriate, indeed obliterates, all other social categories; it concentrates a unified totality around a centre. In these ways it makes possible a unison towards a dominating object. Four systems of symbolism—those of spatial configuration, gesture, language and music—are in congruence in this, the phase of congregation. On the facts, the form has a high practical, logical and expressive efficacy.

It was noted earlier that the credal formulation of Punj does not deal very explicitly with this phase, or with the second—Tjirmumuk—beyond the bare (and, as we shall see, partial) interpretation that the latter is ‘good fun.’ If the Aborigines consciously appreciate any aspect of the geometric idiom, then it is probably the æsthetic aspect, for its appeal to them from that point of view has some suggestive illustrations. The circular motif has a high incidence in the graphic art. A study of the visual sign-system used in that context shows the circle with a range of meanings. It may be intended to show a camp, a waterhole, a secret centre (such as Punj), a sacred totemic site, a yam, a woman’s breast or womb, or the moon. The range defines a category, and the ultimate denotation of the sign is presumably the ground or principle of the category. But its nature or definition cannot be elicited by direct inquiry. One can only try to deduce it by observing and comparing the sequences through which the form passes in a sufficient set of contexts, each set occurring within a separable and identifiable process which is an entity in space and time. One such set of sequences may be seen in Punj.

The rupture of the circle by Tjirmumuk evidently is not—cannot be, if we accept what the celebrants say—intended as a denial of Punj in the respects in which that ceremony deals with things that are ancient, sacred, 157true, and of the highest good and gravity. For the Aboriginal testimony is that Tjirmumuk ‘belongs to Karwadi.’ There is no discontinuity of place or persons. It is a matter of one phase of an entity turning into another, within the bounds of a continuous process. The same men who a moment ago were at one are now, in the same place, at odds. But in every other respect it is as though things had been turned upside down. To the reversals already noted we may add that where before there was song, there is now a babble of noise, sometimes simulating the noise of animals. In addition to being ‘good fun,’ the actions in Tjirmumuk are said by some Aborigines to be ‘like the wild dogs.’ One unusually thoughtful man, trying to meet my repeated requests for an analogy—as I asked him, something that the custom ‘took the place of’—pointed to a covey of birds we could see and hear squabbling over a scarce food, and said: ‘Like that.’

When the scission occurs, one may note that it is the social categories which, ignored in the first phase, are now stressed; negatively stressed, for it is the conflict, not the unity, among them that is expressed. The licence of Tjirmumuk is shown essentially between three pairs of classes of men: between (i) the symmetrical classes of classificatory (‘distant’) wives’ brothers (naŋgun), and the asymmetrical classes of (ii) classificatory mothers’ brothers and sisters’ sons (kaka-muluk), and (iii) classificatory fathers and sons (ŋaguluk-wakal).2

Evidently we see again the process of familiar things of social life being drawn on to give shape to less expressible entities and relationships in another realm.

158Tension and potential conflict are constitutively part of every Aboriginal social relation, even within the patrilineal clan. In that mystical and perennial corporation, expediency as well as religious and moral sanctions are ranged strongly against division. But common—or at least not uncommon—experience is that siblings of the same womb do fight; that children defy and even strike their fathers; and that fathers reject their children. The fact that conflict is constitutively part of living is in logical accord with the fact that the principles of living are conjugate.3 No single principle or combination of principles, of social organisation or conduct extends over all the desired objects of living, even for clan-members who, at least in dogma, are a combination, not a competitive association. That is, if they possess, they own or, share, under a tradition that clearly specifies rights in rem, in personam and in animum so that, again at least in dogma, no conflict should arise. But large fields for the expression of vitality, egotism and selfishness are still left open. These, together with the conjugacy of principles, make clanunison in part an ideal and in part a fiction. Beyond the clan they issue in an endless clash of interests. The three pairs of classes of actual or potential affines are those between which hostility is overlaid, or could be overlaid, by transacted or transactable interests in women.

The first phase of Punj uses a geometric imagery to express the relations of men in combination, at congregation, in unison, and—by the symbolism of many external signs—at one. The second phase destroys the geometric imagery to express the relations of men in association as distinct from combination; men at competition, divided, and—again by the symbolism of counterpart signs—at odds. In the first phase there is something like an element of bravura, a going beyond the mean of social life, which in mundane reality can have such unison only in aspiration. In the second phase, there is something like an element of caricature, a diminution of the mean, which is never one of animal anarchy.

159As the rite proceeds the spatial forms have a somewhat different fashion. A linear motif is now added to them. The youths, being secluded at a concealed point some distance away, are brought in file to ŋudanu. Here they find their seniors crouched within the circular excavation, whether it be ‘nest’ or ‘wallow,’ at the mime of the blowfly. The excavation accentuates the crowding together of the celebrants and, visually at least, intensifies the form very much as in the graphic art a set of concentric circles is used to intensify the significance or meaning of its referent. If the celebration is a large one, with many present, the singers form an arcuate line to one side of the circle. The usual position of the youths is between the arc and the circle.4 At the dances and mimes which follow, the arc and the circle are retained, but the decorated men adopt one of two fundamental linear patterns. They emerge from hiding and, as a body, approach the circle either (i) in a sinuously-curving line, or (ii) as a body less two men, who suddenly appear from concealment at another point, joining the main body by a zig-zag path, pausing in their mime at each change of direction, to make the characteristic quiver of body and shoulders which the Murinbata say is a simulation of birds ruffling their feathers.5 Both styles issue in a dance before the assembled men enter the excavation.

The form of Tjirmumuk having been described sufficiently, we may look briefly at two other occasions when the circular-linear patterns are exhibited.

160At night, when everyone in the camp (which has a circular form) is asleep, or is pretending to be, the young men are led to it in file, to sleep there unspoken to and unseen. The stealthy entry is the opposite of the sign-convention of Tjirmumuk at its camp-phase: the vociferous leap over the heads of everyone. The first tacitly restores a unity, the second dramatically typifies the tensions that are re-entering it.

When the time comes for the initiated youths to be presented to their mothers, the camp assumes the form known as mununuk which, as I have said, connotes ‘waiting, with gifts prepared.’ The close kin of the youths sit in an arc of a circle so that the concave side faces towards the two lines of men, one for each moiety, who stand with legs opened to make passages for the youths as they crawl towards and then away from their mothers.

I have found no way of fixing specific social meanings on the spatial forms. They recur so frequently, however, in the Aboriginal spatial and graphic symbolism that they seem a kind of ‘furniture of the mind’6 (Fig. 4).

I lean to the view that the circle is a naturally-based conventional sign with probably the ultimate meanings of unity or continuity, the line the same type of sign with, probably, the ultimate meanings of action or change, and that the spatial, gestural, æsthetic, linguistic and religious symbolisms raise on them other meanings appropriate to each system.

3. The Problem of Tjirmumuk

The upside-downness of Tjirmumuk may incline many to deny it any intrinsic connection with the sacral aspects of Punj, and to suppose that in Durkheim’s terms it must be regarded as a profane activity.7

161The custom is practised in two places, within the secrecy of ŋudanu, and at the open camp to which the celebrants return. At the first place it goes on, not pro fanum, but actually on the sacred ground of Punj. In the terms of Durkheim’s dual categories there is no ‘break of continuity’ (p. 39). The custom is preceded and followed by sacral actions, so that the continuity is immediate. Nothing overt, or readily accessible to direct inquiry, suggests any ‘sort of logical chasm’ (p. 40) to break the continuity, or any ‘absolute heterogeneity’ (p. 38) between the successive activities such that the one set ‘radically excludes’ (p. 38) the other. When there is such a close and visible succession one cannot say with intellectual comfort that the activities ‘belong to two worlds between which there is nothing in common’ (p. 39), or that they ‘cannot even approach each other and keep their own nature at the same time’ (p. 40). The more closely the category of ‘the profane’ is studied the less suitable it appears.8

Before considering the category of ‘the sacred’ we may rule out certain other possibilities suggested by Durkheim’s study. To all appearances, Tjirmumuk is not a magical rite ‘performing the contrary of the religious ceremony’ (p. 43). Some elements of Punj are magical, but none in the custom of licence. Nor does it suggest itself as ‘a mechanical consequence of the state of super-excitation’ (p. 38) following as ‘a swift revulsion’ (p. 40). On the contrary, there is much evidence of consciously symbolic intent and of consciously patterned conduct. A merely biopsychological explanation could not satisfy.

162And it does not appear the more intelligible if treated as an instance of ‘ritual promiscuity’ (p. 216). The notion of a set formulary, i.e. a ritual, of promiscuity actually doubles the explanatory problem. The three possibilities are to be rejected.

Durkheim’s notion (after Robertson Smith) of ‘the sacred’ as ambiguous and bipolar was based on a postulate that the religious life ‘gravitate(s) about two contrary poles between which there is the same opposition as between the pure and the impure, the saint and the sacrilegious, the divine and the diabolic.’ In short, that there are propitiously sacred and unpropitiously sacred things and, between them, an incompatibility ‘as all-exclusive as that between the sacred and the profane.’ We have already noted the elements of duality in Punj, and might well use Durkheim’s terms, ambiguity and bipolarity. But a cardinal fact should here be underlined: Tjirmumuk is as great a contrast with the ordinary life of everyday as it is with the imaginative life of Punj in its other manifestations. The contrasts are three-sided, not two-sided. Durkheim’s dual categories do not between them ‘embrace all that exists.’ The Tjirmumuk and the Karwadi aspects of Punj both imply, refer to, and use a symbolic imagery drawn from a third realm, one that is neither sacred nor profane but merely mundane.163

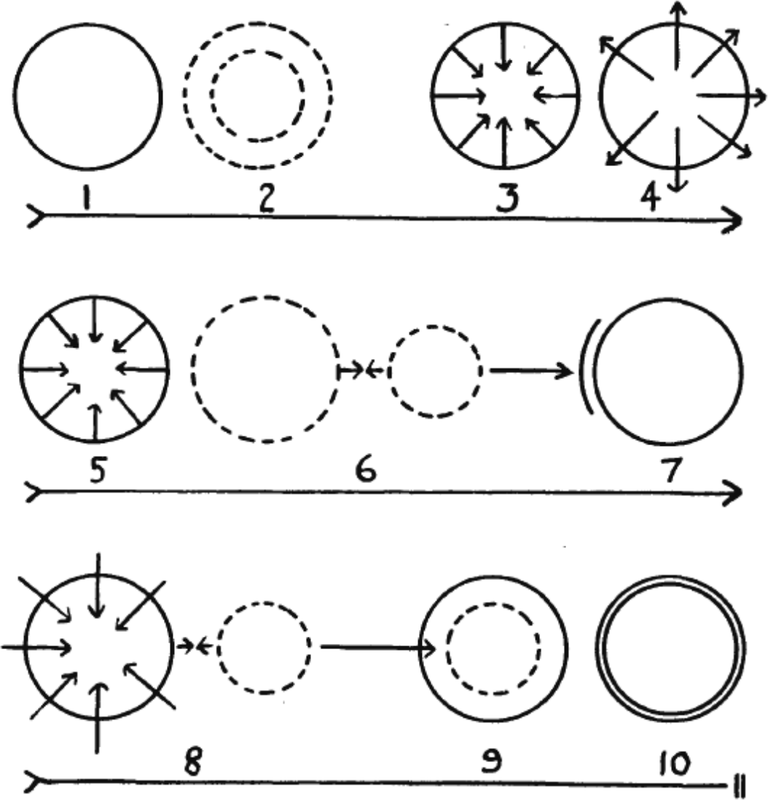

Figure 4. Sequence of Spatial Forms

Figure 4 is in part a schematic and in part an actual representation of the sequence of spatial forms in Punj. (1) The initial situation: the undivided camp. (2) The diminution of the camp: mature men withdraw and the youths are segregated. (3) The song-circle assembles at Nudanu. (4) The scission by Tjirmumuk. (5) The song-circle reaggregates. (6) The ritual preparations are made in secret while the youths are segregated at Mambana. (7) The youths return to witness the rites. (8) The mature men at Tjirmumuk irrupt into the diminished circle, while the youths are isolated. (9) The youths enter the camp secretly. (10) The post-initiation camp with the youths, now men of understanding, in a new locus and status.

The ‘circles’ are schematic in (2), (6) and (in respect of the youths) in (8), but are observable realities in the other cases.

164The celebrants return to the mundane world when they practise Tjirmumuk at the open camp, leaping over the heads of those who are waiting. The very men who, under the terms of the custom, exploded the close circle of Punj, now irrupt into the close circle of the camp. The geometric idiom is thus inverted. In both places they act in ways that seem as far removed as possible from the mundane conventions. The very condition of either demonstration is that there should be, on the one hand, a mean of common life and, on the other, a high order of aspiration and imagination, against which to make the demonstrations. The custom does not profane—by desecrating, violating, degrading, vulgarising, or secularising—either the mean or the higher order. At ŋudanu it breaks up a solidary circle by using a symbolism of animal life to express the hostility underlying mundane relationships. At the open camp it uses the same symbolism, but with inverted geometric forms, to bring the hostility within the circle.

One can scarcely resist the conclusion that there is some kind of praxis and a development of correlated meanings underlying the arrangement of the signs. They are not unconscious; but one must not therefore be understood to say that they are conscious. That dichotomy is not necessarily relevant to the processes of symbolism.

4. Symbolising: Processes and Types

The materials under study are by nature intricate, and the anthropological analysis of symbolism is still in its very early stages. There is advantage in using as simple a conception of symbolism as possible. In what follows I prefer to speak, as far as practicable, of ‘symbolising’ rather than of symbolism in general or of particular symbols. The reasons for that choice may be stated summarily.

One has to dismember the wholeness of a rite to study it at all, but to study and analyse all the component elements of such a rite as Punj is beyond the capability of any single observer. For one must add to the spatial forms just discussed gestures and manual acts in definite 165sequences, mimes, dances, songs, melodies, bodily decorations, and many specific uses of language. What is selected for emphasis is selected in the light of its supposed significance, that is, because of a thesis.

The thesis of these papers has already been stated: that in the rite of Punj the Murinbata express outwardly a complex sense of their dependence on a ground and source beyond themselves. That sense, in my construction, is one of perennial good-with-suffering, of order-with-tragedy. It is a mystery which the Murinbata themselves say they do not understand. But in the words they use, and more especially in the myth of The Old Woman, they are expressing or symbolising an understanding. They do so by putting into words a certain conception of what the rite refers to or ‘means.’ But the rite contains many expressions over a wider range than language and not inherently dependent on it. Language, in this case as myth, is but one of several means or vehicles of symbolising. The spatial forms, the gestures and manual acts, the mimes and dances, the songs and melodies, the decorations and other components, are all symbolising means. Each type of means has—or one may assume it has—an appropriate technique and syntactical system, and for each type of means there is, so to speak, a ‘language.’ One may reasonably assume also that the rite exhibits a measure of congruence, if perhaps not integration, between the many ‘languages,’ though one may doubt if anyone will ever find it practicable to demonstrate the assumptions. In the circumstances, a discussion of symbolism-in-general must usually be too vague and of particular symbols usually too precise for the material as it presents itself in Aboriginal Australia. I thus prefer to discuss the particular processes of symbolising which are more observable and recordable.

The symbolising of all types appears to me to be based somewhat arbitrarily—as I suggested in the discussion of spatial forms—on things interpreted as signs and arranged into patterns. The arrangement into patterns exemplifies the process of symbolising. One encounters the already formed systems of symbolism. Now, I have chosen to discuss the spatial arrangements first because it appears to be through them that, to adopt Erwin Schrödinger’s phrase, the Aborigines most clearly ‘suck 166in the orderliness’ of sign-patterns given in the spatial environment.9 Arbitrary and conventional meanings are put upon the signs, which—being thus interpreted—are then elaborated by the principles governing that class or order of symbolism. The systems of symbolism are thus made up of anterior signs arbitrarily interpreted, transformed, and hallowed by tradition.

If there were an Aboriginal word for ‘nature’ then one might say that the spatial configurations are developments of signs drawn ‘from nature.’ But to do so would be meaningless, for there is no such word or conception. There is only The Dreaming, that which comprehends all and is adequate to all and, like The Deep of Babylonian mythology, ‘of old time reckoned a thing of vast importance in the constitution of the world’10

The mimes, melodies and songs are as important expressively—and, therefore, to the communication, sharing and teaching of meaning—as the spatial and gestural forms, or the manual acts which I have called ‘operations.’ In the light of this argument a primary task of study is to try to discover congruences between two or more formed systems of symbolism. Hence my earlier attempts to show, on the one hand, the homomorphism between Punj and the better-understood institution of sacrifice and, on the other, between the operational structures of the rite and the myth of Punj. I shall now examine the likeness between the operational structure of the rite and the sequences of spatial forms. There too a certain measure of congruence is exhibited.

167

5. A Repeated Theme and Congruent Symbolising

We saw, without drawing on the mythopoeic thought of the Murinbata, that the observable acts at Punj exemplify a kind of drama on the theme of withdrawal, destruction, transformation and return. The associated myth then showed itself to be, not the pathological ‘disease of language’ of which Max Müller spoke, but a credal formulation of the same drama. The structural patterns of both sequences of acts were found to be generally conformable.

The acts or operations at Punj were abstracted from the larger whole of the rite and necessarily included the spatial forms through which they were done. The forms, further abstracted, show that they too exemplify the drama.

The processes of the rite begin, not at ŋudanu, but at the open camp. Yet an examination starting with the assembly of the celebrants at the secret place reveals something like the familiar sequences going on in a somewhat involuted way within a narrower compass and at the same time within a wider compass. There seem to be three interconnected manifestations. (a) The first unison of men at song (the close circle) is destroyed (by the scattering) and then transformed (by the licence of Tjirmumuk) before reaggregation (the restoration of the song-circle). (b) The new assembly is again dispersed (by the detachment of the youths under a guardian, their isolation at a hidden place, the secret decoration of the dancers, and often the concealment of the mime-dancers) before being drawn together again in a new unity with a radically different structure. A ground-circle is now flanked by an arc and is either filled by masked or decorated men (i.e. in new personalities) or is being penetrated from outside by men performing the contrasted movements which have been described. That formation then dissolves into a somewhat formless unity distinct from the initial assembly. (c) The full unity of the whole camp (a circle) is broken by the withdrawal of all mature and young men. Each night, while still 168reduced, it is transformed into a different character by the custom of Tjirmumuk and by the symbolical denial that the youths really visit it or sleep there. It is fully reconstituted again—and then with a developed character—only. after the termination of the rite, when the initiates assume their new status.

Act, myth and spatial forms belong to distinct orders. We are thus not ‘discovering’ the same phenomenon under different names. What we find by analysis is a set of congruences between components of a whole which are expressed according to the technique and system appropriate to each mode of symbolising. A familiar distinction may now be made.

The spatial forms are, in the terms suggested by Mrs. Langer,11 presentational symbolisms. They have somewhat indeterminate meanings imposed on them and, as signs, somewhat indeterminate referents. They have about them something of the character and quality of images or pictures that may be either still or moving. But they are symbolisms because they are vehicles for the conception and expression of the meanings of things, events, or conditions. The process of rite which makes use of them is thus a symbolising process, one of spatial arrangement.

On the other hand, the acts or operations of both the rite and the myth are discursive symbolisms. They express mental conceptions which are fairly definite or indefinite. There is clearly a range from high indefiniteness to definiteness. An example of indefiniteness is that part of the rite at which the young men are taken to the spot where The Old Woman is to become manifest. The old men in this way make a gestural and manual sign towards The Mother by taking or compelling the young men to that place. It is like offering them. But the sign does not ‘mean’ an ‘offering.’ The Aborigines describe what they do but have no clear intellectual conception about it. It is not, therefore, a formed symbolism. On the other hand, there is a clear conception of the blood smeared on the initiates, since it is represented as the blood of The

169Mother and thus symbolises her. One is scarcely more, if at all, than a presentational symbolism; the other is a clear discursive symbolism.

It will be plain in these papers that I depart from the views of some other anthropologists who have discussed religious symbolism. My friend and colleague, the late Professor S. F. Nadel, argued that ‘uncomprehended symbols’ are not really symbols at all since they indicate nothing to the actors. Thus, they have no interest for the anthropologist.12In the sense that ‘uncomprehended’ means ‘unaccompanied by intellectual conceptions’ I am not in disagreement. But one can rarely be sure of the uncomprehension or unaccompaniment. One cannot justifiably infer either from implicitness or wordlessness. A methodical search for congruences between ritual facts of different orders may show that an implicit and apparently uncomprehended symbolism of one order is formulated explicitly in another order. On the other hand, Professor Monica Wilson appears to argue13 that, in order to avoid ‘symbolic guessing,’ the anthropologist should limit himself to a people’s own translations and interpretations of their symbolism. This advice, if followed in Aboriginal studies, would prevent anthropology from going very far beyond just-so descriptions. But in every field of anthropological study, a going beyond the facts of observation—a ‘guessing’ about them—is intrinsic to the act of study, and not even theoretically separable from it.

Ritual symbolisms extend over all the orders of facts that are separable as components of human conduct. The symbolisms of the other orders are not inherently dependent on the symbolisms of language, though they may receive their clearest expression in language. We may see that this is so by referring to the most fundamental categories of the Murinbata language, which are themselves symbolical, though somewhat indefinitely so.

170

6. The Build of the Dreaming

The Murinbata language designates nine or more classes of entities (Table 4). Each class is known by a name that may be used alone or as a prefix to the name of any member of the class. In common speech, the prefixes are sometimes omitted although grammatical speech requires them to be used.14

The classes are not noun-classes in the ordinary sense used of Aboriginal languages. As far as I have been able to determine, there are no grammatical consequences or correlations. It seems best to regard them as existence-classes, i.e. as existential or ontological conceptions, which divide all significant entities in the world into classes which are mutually exclusive.

Table 4. Existence-Classes

| Name of Class. | Content of Class. |

|---|---|

| 1. kadu | Human beings, male and female. |

| Human spirits other than 6 (i), but probably including ngarit ngarit (spirit-children), ngjapan (souls), and possibly including mir (freed souls?).* | |

| Subclass: | |

| (i) kadu-Punj: youths undergoing initiation. | |

| 2. da | Camps and resting-places. |

| Localities. | |

| Subclass: | |

| (i) da-Punj: places known to be, or to have been ngudanu and mambana. | |

| (ii) ngoiguminggi: totemic sites. | |

| 3. nandji | Most natural substances and objects, e.g. stone, minerals, wax, wood. |

| The inedible parts of animals (bones, hair), and plants (leaves, bark). | |

| Artifacts, e.g. utensils, implements, ornaments, ritual objects. | |

| Certain natural phenomena, e.g. fire, mist, clouds, winds, the heavenly bodies. | |

| Urine and human milk. | |

| Dances. | |

| Subclass: | |

| (i) nandji-Merkat: any members of Classes (3) and (4) with an exchange-value in intertribal trade. | |

| (ii) nandji-Punj: any members of Classes (3) and (4) of high ritual significance. | |

| 4. tjo | Offensive weapons, e.g. spears, fighting clubs, boomerangs. |

| Thunder and lightning. | |

| 5. mi | Vegetable foodstuffs |

| Fæces. | |

| Subclass: | |

| (i) mi-Punj: any vegetable food forbidden to initiates. | |

| 6. ku | The flesh, fat and blood of animals (birds, beasts and fish) and of men. |

| Honey. | |

| Subclass: | |

| (i) kukarait: human ghosts. | |

| (ii) ku-Punj: any flesh food forbidden to initiates. | |

| 7. murin | Speech and language |

| Words, † songs, ‡ stories and myths, gossip and news. | |

| 8. kura | Fresh or drinkable water. |

| Rain. | |

| Subclass: | |

| (i) kura-mutjingga: springs and spring-water. | |

| (ii) kura-Punj: ritually dangerous waters. | |

| 9. lalinggin | Salt-water. |

| The sea. |

* There are several classes of spirits which the Aborigines do not classify either as kadu or ku. The distinctions are to be dealt with in a later article.

† I have no evidence of a secret language used by initiates only, although among the Marithiel, a people following a different regional culture to the north-east of the Murinbata, initiates were required to use a special set of words for all food species.

‡ There is no Murinbata word for ‘song’ as such, though there is for the act of singing. I have not heard the secret songs referred to as murin-Punj, but their secrecy, and the condign sanctions of betrayal, are common matters of talk among the initiated.

It is possible (though I think unlikely) that there may be more than nine classes. Some may be unnamed, or it may simply be that I failed to discover them. But those mentioned are readily ascertainable and, with a few minor qualifications, are quite clear in their uses and meanings. The class tjo could perhaps be regarded as a subclass of nandji, and laliŋgin as a subclass of kura; on both matters the Aboriginal testimony 173is a little uncertain. But, with those exceptions, each class is exclusive of every other.

Any attempt to understand the Aboriginal philosophy of life and religion must take the classes into primary account. They are of so fundamental a nature that to try to go ‘beneath’ or ‘behind’ them by direct inquiry usually only bewilders the Aborigines.15 The most fruitful interpretation to be put on them is thus a matter of difficulty. I have come to no final conclusions, but some general truths seem probable.

(1) They apparently embody the character and significance of things that constitute and co-exist perennially in the world, and are thus symbolical. Each class is a distinct and incomparable set of existences, with a type of individuality which the Aborigines generalise. Inference is the only means of discovering the principles of generalisation.

(2) On the evidence of the mythology, the classes as such are not part of the conception of ‘the totemistic dispensation’ to which reference was made. As far as the Aboriginal outlook can be gauged in this way, they seem understandable as conditions of the dispensation. That is, they already were when particular ancestors put these nandji and these tjo in the ŋoigumiŋgi of some clans or dreaming-places and not of others; or found these ku and mi to be good and not those; or by their exploits named, or shaped the physical properties, of places or da where some ancestors went into the ground and the waters, and others flew

174into the sky. Much of the kind suggests the inference that the classes as such are logically anterior, denoting conditions which the dispensation observed. Thus, they do not of themselves bring relation and moral order into the world of multitudinous existences in co-existence: that was done by the ancestors through totemism; what the classes do is to serve as a ground of that dispensation. They are in this sense primary data of life and thought underlying the prolegomena—the discourse on The Dreaming—to the main Aboriginal system of belief.

(3) The list includes all the exterior or sensible objects of life which the Aborigines strive to attain or avoid. Within each class things are valued, negatively as well as positively. The language of the systems of valuation is very simple—a few adjectives expressing crude linear scales—but the systems themselves are multiple. The value-contexts are technical, magical, religious and social, all having negative and positive dimensions. Thus, it is a matter of common experience to see natural objects flung aside with indifference and a disdainful remark ‘nandji-wiya!’ (lit. ‘thing,’ ‘bad’ =unusable, in this context); or food dismissed as ‘mi-wiya’ (‘inedible,’ ‘bad-tasting’); or waterholes pointed out as ‘kura-wiya’ (‘dangerous’); or to become aware of the hush that falls on a camp at night when an untoward sound in the darkness suggests the presence of kukarait. But Murinbata usage suggests that the classes are not simply groupings of entities. They are also, at least in part, groupings of functions in that the entities have a determinate place in the scheme of life, and of powers, in that the entities have efficacies of one kind or another. At the same time they are generic concepts of a kind.

(4) Some of the things, considered as entities, have diŕmu and many have ŋinipun, but these aspects are not developed significantly to make groupings within or between the classes. The idea of ŋinipun is best developed, and then primarily in relation to the eight sub-sections of the class of kadu. These are thought to be bi-sexual groups, each having its own bodily conformation generalised (in English) as a ‘skin.’ The idea is used, but only in a vague and general way, outside that class. The principle of sex is used to a very limited extent outside the kadu class. For example, the red ochres (which are nandji) have sex-names (nogan, 175‘male,’ miŕŋi, ‘female’) according to their brightness, the female ochres being the brighter. The same terms are used for the sex of animals (ku). But the classes are not further differentiated, except by secondary classifications: by utility, physical properties (weight, size, colour), age, value-in-exchange, magical efficacy whether benign or malign, and ritual importance.

(5) The factual reference of each class is proximate rather than primary. Certainly, each of them names and groups objects; but not as mere objects. Every class is a sort of dualism, sometimes a multiple dualism, that states some principle or principles of the thing’s being-there, so that the primary reference is really to pattern ‘within’ or ‘behind’ the factual reference. The pattern is relational, and one capable—judging by the lists—of holding contraries together in unity; but to extract the contraries which are related whether as functions or powers, does not seem practicable.

Class (1) bridges the visible and the invisible; (2) unifies the Here-and-Now with The Dream Time; (3) deals jointly with the corporeal and the incorporeal, the disgusting and the pleasurable, the benign and the harmful, the tangible and the intangible; (4) brackets the human and the cosmic; (5) and (6) make classes—a unity of some kind—out of the stuff of sustenance and the vileness of its process in the one case, and out of that which is most corruptible and that which is most sweet in the other case. Perhaps (7), (8) and (9) suggest more clearly functions or powers perennially consequential for man. The effects resemble paradoxes understandable only through the pattern, the relation of the terms, and not through an isolation of the terms themselves, whatever they may be.

(6) The contexts of use suggest that, if we are to understand the classes at all, it is as having a threefold reference. (a) They categorise the kinds of stuff that make up the external objects of living. (b) The stuff took on pattern or constitutive form of perennial stability at the events of The Dream Time. (c) Each of the patterns has its own import for men. My earlier observations that both the rite and the myth of Punj are ‘dense with import,’ are thus reinforced; for the very language through 176which the more mundane things of life are dealt with is itself dense with symbolical import, although it may be somewhat indeterminate.

(7) There are whole realms of Aboriginal experience and life that lie outside the stuff, pattern and import of the classes, or any combination of them. For they do not embrace the inward or ideal or eternal objects of life, and they assume the actions of men towards or away from those objects.

The analysis has shown that the primary object of Punj is to make youth understand a mystery. But for the myth—and the other commentary offered by the Aborigines—we should not have been able to draw any such conclusion from the rite itself. The aperçu given expression in the myth leaps beyond the import of anything that makes up the rite. The myth is not the only one to suggest that alternatives existed in The Dream Time but, as I have already stated, it seems to be the only truly sorrowful myth.

Several things are to be noted. The leap forward, the ‘going beyond,’ is as much in the realm of life-striving as it is in the affective and cognitive realms of experience. It takes the form of a story which seems new and unprecedented, but the symbolising of mystery is commensurate with all the other concurrent orders of symbolising. That is, the spoken drama of tragedy and suffering is commensurate with the acted drama. And this in turn is commensurate—simultaneous in time, congruent in structural form, and evidently common in meaning—with the spatial configurations through which that drama is acted out.

It is as though that inner paradigm of which I spoke earlier—the ŋinipun or shapely pattern of setting apart, destruction, transformation and return—being immanent in the whole ritual culture of the Murinbata, if not more widely still, were being given, in the myth, its full import through a brilliant aperçu, a new illumination. As though the immanent were being made outward, and being transcended while remaining itself. And this in spite of the fact that boundaries between distinct orders of symbolising are crossed.

(8) The problem of interpreting the classes is made much more difficult by a view that they first have to be made intelligible empirically 177and scientifically. It is hard—and, for my own part, I would say impossible—to equate or delimit or satisfy any of the classes by empirical fact as we grasp it. But if one does not begin with the assumption that there is only one mode of intelligibility then the difficulties diminish. The classes, like the myth and rite which they subserve, belong to the same order of reality as poetry, art and music. On this, let me repeat and endorse what Professor James has said.16 Myth, rite, poetry, art and music, ‘each according to its own technique, externalises and expresses a feeling, a mood, an inner quality of life, an emotional impulse and interpretation of reality’. Goethe, in his conversation with Heinrich Luden, states our first principle: ‘What the poet has created must be taken as he has created it; as he made his world, so it is.’

(9) The course of study must evidently proceed from symbolic import through repeated pattern to constituent stuff. But the significance of the entities—among them the most outstanding being such fundamental things as blood, fire, water, earth, winds, songs, holes, leaves, red ochre, fat, weapons, and spirit-children—in part depends on the human actions taken about them. In the myths, which are the main evidence on which to draw, the actions are assumed as often as stated. The act-structure of myths requires the study of an immense number of discrete activities towards and away from the entities: camping, hunting, tracking, dividing and quarrelling over the fruits of the chase, love-making, plotting, fighting, acts of deception, murder, sorcery and the like. The symbolism of the things is certainly wrapped up with the symbolism of the activities into which they enter, and the classes give us part only of the furniture of the Aboriginal mind.

178A full understanding of the religious symbolism is to be attained only by a thorough morphemic analysis of the whole language. That study is beyond my technical competence. But until the analysis is made we have not penetrated the true inwardness of the stuff of symbolism. All we have done is to attain a rough idea of its pattern and import. The ‘build’ of The Dreaming is the product of an intimate interrelationship between all three.

Perhaps we have shown, however, that the fact that many of the dominant symbolisms are not put clearly into words does not condition their valence. It conditions only the capacity to express clear conceptions in words and sentences so that for the most part they remain beyond the symbolism of language. But not beyond the symbolisms which are independent of spoken language. The Murinbata have no words for, say, ‘sine curve’ and ‘leftward-moving spiral,’ but the celebrants of the rite trace out such evolutions year after year. These and other forms are so clear, dominant, and persuasive in their minds that, as they trace them out, the Aborigines seem to be saying (as R. R. Marett once put it): ‘How, if not thus?’ They are drawing on a rich stock of conventional signs known and used skilfully without any necessity of verbal symbolism. An observer has to stifle his own mind not to see in them the expression of æsthetic insight and a rhythmic symmetry of design. It is impossible to dismiss them as ‘uncomprehended.’

7. The Dominant Symbolism

The telling of Murinbata myths often but by no means always ends with the exclamatory word Demŋinoi! A plural form is about as common as the singular: it then becomes Pirimŋinoi (sometimes pronounced as Peremŋinoi). Both are verbs in the third person and evidently in the past tense. The usage suggests a reflexive verb, but this remains uncertain. No other forms—if there ever were any—survive.17

179English-speaking Aborigines phrase the meaning of demŋinoi as ‘changing the body’ or ‘turning’ from man (kadu) to animal (ku). It appears to have certain connotations, at least further suggestions, among them ‘spreading out,’ ‘flying away,’ and ‘going into the water.’ There are distinct words for such activities, but they are seldom used in the myths, demŋinoi evidently being able to suggest them. The central meaning of that word seems to be ‘metamorphosis,’ one that is instant, a voluntary exercise of choice, and at the same time a necessity of overwhelming circumstance. It is clearly a metempirical conception.

One man, trying to clarify the meaning for me, referred to the Murinbata belief that a hunted animal, in order to save its life, may change itself instantly into something else. He said: ‘ku-ḍaitpiṙ bamgadu ku-ŋinipun diniḍa … ḍamul manaka panyatka nyinida nandji-buṙuṙ wada demŋinoi.’ Literally, ‘animal or flesh+true—I saw—animal or flesh+shape or body (i.e. having the body or outward form of an animal)—being there—spear—as soon as, at the same time as—I threw—that which is there—inanimate thing+antbed—now, instantly—changed mysteriously.’ In other words, ‘I saw a veritable animal; I threw a spear; instantly and mysteriously, it changed into an ant-bed.’ He put the story forward as an instance of personal experience.

The demŋinoi in this explanation could not be replaced, my informant said, by any other word and still have the same sense. For example, by dinim, which means approximately ‘became’ in the ordinary English sense and, in Murinbata, is used when a man becomes a wise man (wanaŋgal) as the result of a mystical experience. Or by baŋambitj, which means something like ‘made itself’ or ‘was responsible for its own existence,’ the word being used for self-subsistent spirits (kadu baŋambitj) which are distinguished from the spirits of dead human persons. Or by yiŋambata, which means the mystical process by which a totemic ancestor—at the instant of, and also by the act demŋinoi—made a spirit site or ŋoigumiŋgi.

The conception of a metamorphosis of animals into humans or humans into animals is of course at the very centre of Aboriginal symbolism throughout Australia. The facts that the myth of The Old 180Woman does not stress, or apparently even mention, the demŋinoi motif and that the transformation of youths during the rite of Punj is not consciously likened to that type of transformation, are therefore interesting and in need of explanation. At the same time there is undoubtedly a certain likeness—the kind of likeness that constitutes metaphor—between (a) the sequences of mythical events leading up to the ‘changing of body’ and ‘spreading out,’ etc., and (b) the sequences acted-out in the rite or narrated in the myth of Punj. Obviously, a more careful study is needed of the apparent reduction or elision of so dominant a motif, or its possible concealment in metaphor.

It is to be remembered that we are dealing with a moment in the development or practise of a religious cultus. The Karwadi exemplifies a leap forward from older religious habitudes. By ‘cult’ one means precisely a going-beyond what was before. In such a cult a hitherto common value may be made sacred, or one that is already sacred made holy. Evidently it is the second step that has been taken in the rite and myth under study. In such a process a kind of chiaroscuro results: the blaze of the holy casts many shadows dimming much that before may have had the highest significance, even blotting it out, since there is nothing so dead as last year’s cult. In linguistic symbolism we are dealing with intellectual conceptions making use of familiar imageries. In the linguistic symbolism of cults of the second kind, we may suppose that we shall meet with conceptions that are enhanced in much the same measure as the religious value. The motive of the Karwadi cult has been suggested as a discovery, or an illumination, of something in the condition of human life that excites sorrow by its sad inevitability. The particular symbolism through which this is expressed in the myth of The Old Woman appears to be made up of enhanced tropes or embellished metaphors of a conception arranged and expressed differently, but still recognisably, in other myths. The myth of Old Crow tells how men learned to die. The myth of The Rainbow Serpent tells—among other things—how the very condition of humanness, the possession of fire, was at the expense of the death of the father’s father of one moiety of men and the mother’s father of the other. The myth of Karwadi tells, 181in terms of sorrowful mystery, how young life had to be saved from its guardian. There is no evidence on which to base a chronology of the three myths, but the second certainly antedates the third. The myth of The Rainbow Serpent stresses the demŋinoi motif; the myth of The Old Woman does not elide but transfigures it, by changing some elements, by rearranging others and embellishing the same general pattern. In one, the death of a dualistic father one generation removed is the condition of the survival of all humanness. In the other, the death of The Mother is the condition of the perpetuation of human life through its children. The latter is a metaphor of the former, but intensified: the locus of good-with-tragedy is unified in the image of a single instead of a dual personage, and one that is a generation nearer.18And the element of sadness within, and evident in the telling of, the myth of The Old Woman has no counterpart, to my knowledge, in the myth of The Rainbow Serpent. We seem thus to meet a consonant development of insight, linguistic expression, and emotion.

It might seem, however, that the congruence of pattern between the myth and the rite under study argues against rather than for the thesis of cultistic development. The relation may be stated more exactly. It is one of analogous elements arranged with similarity of form or pattern and having a commonness of import manifest in different types of symbolism. Having examined a rite associated with a myth, I propose in the next article to examine (a) a myth not associated with a rite and (b) a rite not associated with a myth. If a pattern can be found constant between all three, then its dominance seems well established, and we shall be better able to ask what evidence should be discoverable if in fact a development of symbolising has taken place around a continuous form. In (a) the structure of the myth of The Rainbow Serpent will be studied, and in (b) that of a funerary rite which once brought all the clans together to give a man’s soul its quittance. Taken together, they seem to me to establish that Aboriginal man, ‘the victim of transience in himself and in the forms among which he dwells, is yet endowed with

182the power to create forms which endure.’ And more, has the power to adapt the work of his imaginative mind to the unfolding of history.

1 See Oceania, Vol. XXX, No. 4, p. 270, for other meanings.

2 In the Murinbata system of kinship, affinity and marriage the class of wives’ fathers (kapi) is a subclass of the class of mothers’ brothers (kaka), such that any kaka who is not a uterine brother of a man’s own mother may become kapi. Since there is frequently an exchange of sisters in marriage, the wife of kapi is distinguished from the class of fathers’ sisters (pipi) by the (untranslatable) suffix nginar. A man’s own father’s sister’s cannot be pipi nginar in any circumstances. A brother of pipi nginar is distinguished from the class of fathers (yile) by being termed ngaguluk. This term was adopted from the Djamindjung and, being affected by Murinbata phonetics, is sometimes pronounced ngawuluk.

3 See ‘On Aboriginal Religion’ II. Oceania, Vol. XXX, No. 4, pp. 245–78; especially pp. 266 ff.

4 My earlier statement that they ‘are taken into the centre of the circle, told to kneel, and to imitate the action of the others’ is in error. They are taken to the centre of the arc, told to sit, and to ‘follow up,’ i.e. on future occasions, the actions of the mime.

5 I could discover no evidence that the Murinbata, like the Warramunga of north-central Australia, think of this gesture as setting free spirit-children or any kind of life-principle. Otherwise, they give only technical and æsthetic explanations of the custom. The Murinbata ideology associates ngarit-ngarit or spirit-children only with green leaves. The dancers tie to their shoulders, and carry in both hands, bundles of leaves which have been scorched crisp so that the quivering of the shoulders will give out a pleasing sound.

6 I adopt the phrase from W. H. R. Rivers, ‘The Symbolism of Rebirth,’ Folk Lore, Vol. XXXIII, No. 1. Rivers was discussing the problem of universal symbolism, a matter that does not enter into my examination.

7 All references are to the 1915 edition of The Elementary Forms of The Religious Life.

8 In an as yet unpublished article, I have questioned both the logical adequacy and the empirical warrant of the dual categories. Durkheim gave various meanings to ‘the profane’: among them, minor sacredness, non-sacredness, dangerous non-sacredness, anti-sacredness, and simple commonness. His system requires, among other additions, the recognition of a third category, that of the common or mundane. His analysis appears to rest implicitly on such a category. Consider, for example, his many references to ‘ordinary things,’ ‘things of common use,’ ‘the ordinary plane of life,’ etc., etc. But he gave the category no formal place in the ‘bipartite division of the whole universe, known and unknown, into two classes which embrace all that exists, but which radically exclude each other.’

9 Quoted by F. W. Dillistone in Christianity and Symbolism, London, 1955, p. 36.

10 F. E. Coggin, The First Story of Genesis as Literature, 1932. One might adapt to the Aboriginal use of the phrase ‘The Dreaming’ the author’s remark that ‘any name for the material which goes to the making of the world would have been deficient had the Deep not been included’, pp. 4–5.

11 Susanne K. Langer, Philosophy in a New Key, 1942. My use of ‘discursive’ symbolism is also drawn from this source.

12 S. F. Nadel, Nupe Religion, 1954, p. 108.

13 Monica Wilson, Rituals of Kinship Among the Nyakyusa, 1957, p. 6.

14 Aborigines often complain that their children speak ungrammatically, pronounce words incorrectly, and use slang.

15 I mentioned earlier the embarrassment of my informants at the disclosure that Europeans are (at least, were) given the same prefix (ku) as the class of beasts and honey. On the same occasion I was defeated—by, among other things, the merriment of my informants—in an attempt to get their explanation of the inclusion of food and fæces in the same class (mi). No, they said, it did not imply that anyone ever ate fæces; how could this conceivably be so? It was just a matter of murin, of language; perhaps fæces looked a little like mi; now that I had mentioned the matter, it did seem amusing; but it was not a thing of any importance. The more intelligent men developed a marked interest in my morphemic inquiries, and had some interesting things to say about how words might have been ‘built up’ in The Dream Time, but the discussions were never of any use in clarifying the existence-classes.

16 E. O. James, Myth and Ritual in the Ancient Near East, 1958, p. 309. Though developed mainly with reference to other cultures, Professor James’s thesis holds true of the Aboriginal material in all essentials. Myth and rite ‘give verbal and symbolic form and meaning to the emotional urge and rhythmic relations of life as a living reality, recounting and enacting events on which the very existence of mankind has been believed to depend, and proclaiming and making efficacious an aspect and an apprehension of truth and reality transcending historical occurrences and empirical reasoning and cosmological and eschatological speculations.

17 I heard one possible exception, the form pennginoi-nu, which could be the 1st pers. sing. fut. but there was some head-shaking about it.

18 The dualism is not wholly removed for the myth records her remarks to grandchildren.