IV

The Design-Plan of a Riteless Myth

1. The Myth of the Rainbow Serpent

It has long been recognised that Aboriginal mythology in many parts of Australia gives great prominence to a being for whom Radcliffe-Brown suggested the title The Rainbow Serpent. Certain elements of belief about that being are so widely distributed that Radcliffe-Brown thought they might ‘very possibly be practically universal’ and form a conception ‘characteristic of Australia as a whole and not of any one part or stratum of it.’1 The elements he thought ‘more essential’ are: (1) a conception of the rainbow as a huge serpent which (2) perennially inhabits deep, permanent waters, (3) is associated with rain and rain-making, and (4) is connected also with the iridescence of quartz crystals and mother of pearl. He was inclined to represent The Rainbow Serpent as a sort of guardian-spirit. Its invariable association with water suggested to him that the Aborigines conceive of it as The Spirit of Water.

A myth in which the four elements occur is told widely among tribes on the north-west coast of the Northern Territory. I recorded the Murinbata version in detail but could recover only fragments of the versions known to the Marithiel, Nangiomeri and Wagaman. The account and analysis that follow deal primarily with the Murinbata version, but I include the other tribal outlines as well because of the possible significance of their variations.

Among the Murinbata, The Rainbow Serpent has at least four names, or perhaps it would be more correct to say, one proper name but may be identified in three other ways. The proper name is Kunmanggur, of which no English equivalent can be suggested. Curiously, the name is

184borne by at least one living female although, in the myth, it is the name of a male being, albeit a male sometimes said to have breasts like a woman. In the narration of the myth Kunmanggur is used interchangeably with Kanamgek which, with one qualification, may be admitted also as a name. The qualification is that Kanamgek is recognisable as a compound verb-form, made up of an auxiliary and a root. The auxiliary is kanam, the 3rd pers. sing. pres. of a verb (often used as a suffix, but here as a prefix) meaning a repeated, habitual or continuous state of being. The root is the element gek, evidently an archaism, and of uncertain meaning, which is just possibly distantly cognate with a current verb meaning ‘to spit water.’2 The third name or word, Dimgek, is a similar compound verb-form, with the same root, but another auxiliary (dim), meaning a present instance or state of being. When a rainbow is mentioned in a conversational context, without mythological or religious reference, the word dimgek is then used, and may be regarded as the common word for rainbow. But because it is very occasionally substituted for Kanamgek, it should perhaps be considered a name also.3 The fourth usage is Kulaitj, used here as a sort of name, but in other contexts as an ordinal adjective meaning simply the older or eldest. In the narration of the myth, and in discussions about it, the changes are rung on all four words. Kunmanggur and Kanamgek are about equally common; the two others are used occasionally. It would be near the general spirit of the usages to say that Kunmanggur, the main proper name, carries the sense of The Oldest One, He Who Perennially Is-Acts, Is-Acts Now.

185It seems remarkable that the myth, which is the longest, the most detailed, and—to a European mind—the most dramatic of the many known to the Murinbata, should have no demonstrable connection with any rite now or recently practised. There could have been some such connection in times gone by, but the Aborigines make no such assertion and, when questioned on the matter, have nothing helpful to say. There is a second unusual aspect: the Kunmanggur of the myth is identified with the being visually portrayed in rock-paintings at Purmi and Kirindjingin, just outside Murinbata territory. The sites of the paintings are mentioned in the myth, and the tradition identifying the two beings is strong; but tradition is not evidence; and there is no way of knowing if the myth and paintings were coeval or not. The paintings no longer have any function in Murinbata life and what their functions may have been in the past is very obscure. As far as I could determine, only one other myth is associated with rock-paintings and it, like that of Kunmanggur, has no ritual connections; but a great many myths are told that have no associations of either kind. In the circumstances an a priori assumption that all myths have their genesis in rites—an assumption that Robertson Smith made—is unpersuasive, and the hermeneutic approach in which one looks to the ritual life for the first hints about the nature of truths being stated in myths meets a serious check.

On the other hand, the paintings associated by tradition with Kunmanggur are works of high imagination; it would not be too much to say, of artistic passion. And the myth itself is one of great power. To anyone familiar with Aboriginal life, and especially with its religion, a supposition that two such powerful expressions of Aboriginal insight could have developed without ritual associations has an improbable ring. The somewhat draconic argument of Radcliffe-Brown—that a conjectural history could but confound the problem—is an argument against unsupported history, not against speculation. If his caution is 186given due weight, one may try justifiably to do the two things attempted here: to look within presently dissociated myths for the structural forms that would enable them to be compared with myths still demonstrably connected with rites, and to elicit from myths of both classes their kerygmatic elements—the statements of abiding truths about life—for comparison.

The manner of telling the myth of Kunmanggur amply supports Strehlow’s observation that an Aboriginal language is ‘an instrument of great strength and beauty, which can rise to great heights of feeling.’4 True, many, if not most, of the northern myths are, as he said of those of central Australia, ‘rarely elaborate in form’ but ‘simple and brief accounts of the lives of totemic ancestors of a given group in a tribe.’ But that of Kunmanggur is one of three—the others deal with The Old Woman (already narrated) and Kupki, The Snake Woman—which in every way warrant the use of the most sensitive art of translation. All three suggest that an oral literature of expressive beauty may not necessarily be rooted in ritual ground. Many Aboriginal myths seem pointless and inconsequential to a European mind, but these three make an immediate appeal by reason of the incident, texture, structure and climax of their stories. They demonstrate perhaps as well as anything could that although the weight of the past is very heavy on the present of Aboriginal life, and although there is a ready—and, at any moment, uncritical—adherence to ‘received opinions and traditions,’ the Aborigines do not live an ‘unexamined life’ in the Socratic sense. Each myth has something to say—something significant, said beautifully and tragically—about the first and last formula of things, the ultimate conditions of human being, the instituted ways in which all things exist, and the continuity between the primal instituting and the experiential here-and-now.

The four elements which seemed to Radcliffe-Brown ‘more essential’ are actually of secondary importance in the northern myth. Their main usefulness is taxonomic. The Rainbow Serpent does appear to be a kind of guardian spirit, and to say that he is The Spirit of Water is not

187inapt. But the quiddity of the myth transcends such characterisation. What it narrates is a religious world-drama: a drama because it tells of events that follow in sequence to a unison which is a consummation by catastrophe; a religious drama because ultimate things of human being and existence are the concern throughout; and a world drama because the import is cosmogonical. The drama has a surface stratum and a deeper stratum. On the surface one hears of acts of incest by a brother; of deceit and parricide by a son; of the gift by a father of perennial water, the means of eternal life; of the attempted deprival by The Oldest One of fire, that which divides men from animals; and of the restoration to all by one man of fire, that which makes men human. I shall put upon these elements a construction consistent with the argument of earlier papers in this series: that they are symbolisations, or sorts of statement about one set of things under the guise of another. The task of analysis is to elicit from a myth that is in no way connected with any rite the masked propositions of life concealed on the deeper stratum.

2. The Problem of Myth-Variation

An important—perhaps decisive—point should be made here. There is no univocal version of the Kunmanggur myth; nor, indeed, in my opinion, of any Aboriginal myth. One is not dealing with dogmata or creeds, so there is no question of an authoritative or doctrinal form. Narrators may, and do, start or finish at somewhat different points; omit or include details; vary the emphases; describe events differently and attribute them to different causes and persons. Certainly, there is a sort of standard nub or core, a story with a plot, that all observe broadly. But, in my opinion, there is no accepted or enforced consensus, as in a formulated creed. I began my studies with a presupposition, drawn I know not whence, that for intellectual reasons there must be a consensus, a consistency of all versions in all parts. With short and evidently unimportant myths, a high consistency between versions could be obtained. But I failed to do so with the long and elaborate myths. These tax the 188Aboriginal memory by reason of their complexity, but the complexity is not the cause of the variation, which seems due rather to the fact that the formula of the nub or core-story allows a wide field in which free imagination can play. The moving shapes of actual life appear to be drawn on to exemplify the formula, and the elements of the core appear also to be open to commutation. Variations of such kinds may be noted in versions of the myth given by individual persons among the Murinbata and also among the tribes of the same cultural region. I did not perceive for a long time the possibility that the variations might be as significant as the postulated consensus; that there might be one or more meaningful structures of variation. Experience eventually convinced me that the variations do indeed have inspirations and a logic of their own. When one is disabused of the misleading notion of a dogmatic version, variable only because of the frailty of human memory or from similar causes, one is compelled to consider the possibility that what keeps a myth ‘alive’ is not only the intrinsic interest or relevance of its story and symbolism: the dramatic potential is also involved. Every myth deals with persons, events and situations that, being less than fully described, are variably open to development by men of force, intellect or insight.55 Under such development, motive can be attributed, character

189suggested, and events and situations elucidated—or commutated—in a formative way without any actual breach of a tradition. By the same token, elisions can occur. So that unless one is able to compare versions of a myth given by the same individuals, or at least people of the same intimate group, at sufficient intervals, one cannot say with surety much about the status of a version recorded on a particular occasion.

In the above circumstances, I am unable to regard the myths of the northern region as conforming to what Strehlow has said6 of those of central Australia. He contended that ‘it is almost certain that native myths had ceased to be invented many centuries ago’; that ‘the present-day natives are on the whole merely the painstaking, uninspired preservers of a great and interesting inheritance’; that ‘they live almost entirely on the traditions of their forefathers’; and that they are ‘in many ways, not so much a primitive as a decadent people.’ My own experiences suggest the opposite of each statement. Mythopoeic thought is probably a continuous function of Aboriginal mentality, especially of the more gifted and imaginative minds, which are not few. The notion of a time when myths were, or ceased to be, invented is probably a schematic figment: one could as legitimately postulate the ‘invention’ of the family, the forms of social organisation, or any institution. Such a vocabulary of thought is wrongly applied to organic growths. In the north, there is every evidence of painstaking adherence to traditions; but the traditions themselves are a continuous inspiration; and adherence is not necessarily dispassion, disinterest, or dullness. The presence of a religious cult, in all probability as one of a succession, does not suggest men who simply live on the spiritual capital of olden times. Doubtless, there was a time when these Aborigines struggled up to the plateau of social and religious attainment on which Europeans found them. Much evidence points, not to decadence, but to a lively and developing life on the plateau. Against, then, Strehlow’s view that in central Australia there is an ‘attitude of utter apathy and … general mental stagnation … as far as literary efforts of any kind are concerned’ I can but record my own experience of having heard brilliant improvisation, and my belief

190that this is part of the process by which mythopoeic thought nurtures and is nurtured.

The telling of a myth, then, is apt to vary with persons, occasions, and times. Many circumstances and, doubtless, many motives may have such effects. An informant’s forgetfulness, lack of interest, mentality, prejudice and notion of what a questioner wishes to hear, or should be told, may affect the version recorded. It will surprise no experienced anthropologist to be reminded that jealousy, shame, a desire to shine, and an unfathomable malice not infrequently may affect Aboriginal informants in this as in other matters. Even the best informants on occasions may become a joyous danger for another reason—the mind, voice and imagination of such a person can make deeply exciting a myth left dull by another’s. Whose version is one to accept? In many such cases I have no doubt that personal inspiration, leading to improvisation, takes place. Listeners rarely interrupt others’ narrations to protest or disagree although, later, and—because of the convention of good manners—in private, may say that the telling was wrong. But their own corrections may meet with the same criticism from others. The anthropologist is thus under a practical necessity to decide on a version, and under a moral and intellectual duty to decide what is representative. But his decision is also one of art.

In the following account of Kunmanggur I have tried to indicate, as best seems possible, the main elements of agreement and variation. The Murinbata record is perhaps best prefaced by the few details I was able to obtain from adjacent tribes.

3. Three Fragmentary Accounts

During the course of field work in 1932–35 I was able to obtain the broad outline of the Marithiel, Wagaman and Nangiomeri versions of the myth. The fragments are worthy of record for the contrasts they afford with the Murinbata myth.191

The Marithiel at that time were deeply disturbed, had abandoned their tribal home in the paper-bark forests, were crowding in upon the Daly River, and were at violent enmity with the river tribes amongst whom I was working. I depended on a single informant, a young man who had a poor grasp of his own culture. He told me all he knew.

Lerwin, The Rainbow Serpent, had no wife. Amanggal, The Little Flying Fox,7 had two wives. Lerwin stole one of the women while Amanggal was looking for food. When he discovered the loss, Amanggal pursued Lerwin to a far country and slew him with a stone-tipped spear. Lerwin cried out in pain, jumped into deep water, and was transformed into a serpent. Amanggal flew into the sky.

My informant could not say what were the relations between the principals, but I was able to gather a few further pieces of information: a lively dread of Lerwin; a belief that, in the serpent-form, he inhabits deep waters, whether salt or fresh; that his tail is hooked (‘like an anchor’); that he drowns people by thrusting the hook through a leg behind the heel-tendon, and also that he uses the hook to smash canoes and boats or to draw them under water; that newly initiated boys should not immerse themselves wholly in water lest they be seized and drowned by him; and that there is a close association between Lerwin and the iridescence of pearl-shell.

The information about the Wagaman version was about as sketchy. Only a handful of elderly men of the tribe were then on the Daly River, and they wanted as little to do with Europeans as possible. The main name of The Serpent was given to me as Djagwut, but the Wagaman appeared to distinguish two rainbows, one described as being ‘high,’

192one ‘low.’ I could not be sure if they were making a distinction between the main colour-bands of rainbows, and the spurious bows, or between primary and secondary rainbows. The ‘high’ (i.e. secondary) rainbow was described as the spit of Djagwut and the ‘low’ (i.e. primary) rainbow as the spit of Tjinimin. Djagwut was recognised as the source and protector of human life, and as the giver of spirit-children. He was supposed to persist in deep springs, rivers and billabongs, and to be especially dangerous to menstruating women, being able to smell them from afar. The Wagaman assigned Djagwut to the Tjimitj subsection and Tjinimin to the Djangala sub-section, the two thus being in an affinal (wife’s brother) relation.8 All I could recapture of the myth was that Tjinimin had two wives; that Djagwut stole both of them; that Tjinimin pursued and slew him with a stone-tipped spear while asleep, the spear striking him in the back. Djagwut cried out in pain, jumped into deep water, and was transformed into a serpent. Tjinimin flew into the sky.

The Nangiomeri version, though fragmentary, was a little more specific in some details. The Rainbow Serpent, Angamunggi, was described to me in terms of the familiar All-Father imagery: as the primæval father of men, the giver of life, the maker of spirit-children, and the guardian and protector of men. The decimation of the tribe at that time by disease, and the declining number of children then being born, were said to be due to the fact that Angamunggi had ‘gone away’ and no longer ‘looked after’ his people. The Nangiomeri seemed to think of Angamunggi as a dualistic person. They suggested that he had a womb, that a son had died within it and that the ‘low’ or ‘small’ rainbow (Amebe) was also his son. He was assigned to the Tjanama sub-section, and Adirminmin (again described as The Little Flying Fox) was assigned to the Djangala sub-section, that is, to the correlative affinal sub-section of Tjanama. The myth as it was told to me ran thus:

193Adirminmin went about trying to find good stone for a spear. He went to many places. Finally he went to a spring at Kimul (on the Fitzmaurice River). There he went hunting for kangaroo. He was a Djangala man and took with him two Nangari women who had been given to him by Angamunggi. The two women went away and hid. Carrying a kangaroo, he caught up with them. They were on a high cliff and made a rope to lift him up. The rope broke and he fell down a long way, breaking his bones. The women went to bathe in the salt-water part of the river, and then ran away, with sexual intent, to Angamunggi. Adirminmin mended his broken bones, bathed in the salt-water, and set out to recapture the women. The tide kept on sweeping him back as he tried to cross the river. He went to try to find good stone for a spear. He tried several kinds of stone, but they were not sharp enough. Finally he found a sharp stone called katamalga, and put it on a spear-shaft. Then he chased and found the women. He said: ‘Ah! Here you two are! I have to pick up my spear.’ He sang the song that begins Kawandi, kawandi; then he danced by himself; and, after that, went to sleep. Wakening, he found Angamunggi, and threw the spear so that it pierced The Rainbow Serpent’s backbone.

4. The Murinbata Myth

I shall now set out, at length, the myth as it is told among the Murinbata. In the form given, it is known only to older people who were adult at the time when the Mission of the Sacred Heart was established (1935).

It is divided somewhat arbitrarily, for ease of reference, into numbered sections, each section being a roughly distinguishable phase. Major variations made by informants are put in square brackets, and my own truncations in doubled square brackets.

(1) Kunmanggur had two daughters, Pilitman, The Green Parrot Women (ornithological identification uncertain). [They were the sisters of Tjinimin, The Bat.] They were with Kunmanggur at Kimul. They said: ‘Father, we want to go that way,’ pointing towards the sea; 194‘we want to find food.’ Kunmanggur sent them from Kimul towards the island known as Nganangur. He said: ‘Take this bottle-tree (bamnudut, baobab) and put it on that island.9 You will find a good place there.’

(2) The two girls went off, carrying digging-sticks. They went to the place known as Mindjini-Mindjini, and there began to gather many pieces of paperbark. Then they went on, to camp at Were-Kurumbunuru, near Maiyilindi. The next day they passed a big hill, and crossed over the big river near Wakal-Tjinang. They gathered paperbark at Paiyer, and divided the sheets of paperbark into two big heaps, one for each of them. Then they went on to Nganangur to look about for fish and crabs.

(3) [Tjinimin lusted after the girls.] One had pubic hair, the other none. They were very pretty. Tjinimin [did not care that they were his sisters or were of the Kartjin moiety, his own; he wanted them, and] meant to follow them. He said to Kunmanggur: ‘Father I want to go that way,’ pointing in the direction in which The Green Parrot Women had gone; ‘I want to see The Flying Fox people.’ He was deceiving his father. Tjinimin wore his forehead-band (daral). [His penis was still very sore and painful.10 He followed the girls, but lost their track after

195Mindjini-Mindjini, where he veered to the west. He took another road passing through Dangaiyer. He killed a rock-wallaby and roasted it quickly because he thought the girls might be close. He put the wallaby on his shoulder to carry it but it burned his neck, so he dipped his burden in water. Then, still carrying the roasted wallaby, he came on the girls’ track. On an open place, he saw the paperbark they had left. The girls were not there.

(4) When he saw the paperbark Tjinimin said: ‘Ah, this is theirs; they left it here.’ He knew they would come back. He took the wallaby to a jungle and hung it in a tree. [Then he made a spear. He went to where the girls had made camp and saw some of their menstrual blood. At the sight, he had an erection.] He took white paint, softened it in his mouth, and painted himself like an initiated man, and put on a pubic-covering. Then he moved the paperbark to another position, smoothing out all the marks where it had lain. He piled the sheets one by one on top of himself so that he was hidden underneath. He crossed his arms on his chest and, breathing through a small hole, waited, listening and sleeping alternately.

(5) After a long time the girls came. They had many mullet with them. They put down the fish and made a fire.11 They did not see Tjinimin. Then they noticed the changed position of the paperbark. ‘Oh, sister,’ said one, ‘look! a big wind must have done this.’ They began to sort out the sheets. ‘Whose is this?’ ‘It is mine; put it here.’ ‘Whose is this?’ ‘It is mine; put it there.’ At last, only one big sheet was left.

(6) As the last sheet was taken away, Tjinimin leaped out, laughing with glee and malice. The girls were startled. ‘Oh, my brother is here,’

196said one. ‘Why have you come?’ Tjinimin said: ‘My father12 sent me to find you two.’ ‘Perhaps you are pretending? My father did not tell me that.’ ‘No, my father said to bring you back.’ But Tjinimin was deceiving them. [He showed them his erect penis, and spilled semen on the ground. The girls were very frightened. ‘What is that you have lost?’ said one. Tjinimin replied: ‘It is nothing.’] He kept on laughing.

(7) He next told them to get the wallaby. The girls said: ‘No, you go for it; we are tired from coming through the mangroves.’ Tjinimin did so. He then invited the girls to eat of it. They refused, saying: ‘No, leave it until later; we will eat the fish before it is rotten.’ He said: ‘I will keep it for you. You will eat it bye-and-bye.’ They ate the fish, offering some to Tjinimin.

(8) As darkness came, he went for a walk, telling the girls to stay where they were. The sun was going down. [He took off his pubic covering. Hornets came and stung his penis so that it swelled enormously.] With the darkness, he returned to prepare a camp. He told the girls he would copulate with them. They said: ‘We cannot do that; we are your own sisters; you are our own brother.’ Tjinimin replied: ‘It does not matter; it is enough that I came alone; no one is here; no one can see; we must copulate.’ He threatened them that if they did not he might do something like Yerindi13 to them. The girls were very frightened. They said to each other: ‘Sister, who will go to him?’ The younger said: ‘I have no pubic hair. You go.’ So the older sister went to him. Tjinimin made fire. The

197three slept thus: the younger Pilitman between two first, Tjinimin and the older Pilitman between the second and third fires.

He copulated with the older girl, so that she cried out in pain: ‘Oh! Oh! brother! Oh! sister, come to me.’ The younger Pilitman was asleep; she did not hear. He did it to the older Pilitman again and again, leaving her half-dead. Her sister brought her water, and she slept as though dead. Tjinimin then copulated with the younger girl. She too cried out in pain: ‘Oh! Oh! brother!’ She called out to her sister in vain.

(9) The next day the girls went to get water at the creek known as Merngoiyi. It was dry. They went back and said to Tjinimin: ‘Come, we will all go to-day.’ Tjinimin said: ‘No, let us stay here another day.’ The sisters said: ‘No, we had better go; we can sleep on the other side of the creek. We will carry the paper-bark; you can carry the kangaroo.’ But they told Tjinimin to wait while they went ahead to make a crossing. On their way through the jungle they danced, and the magic of the dance brought hornets to wait on Tjinimin’s path. When he came, they stung him everywhere, all over his body, so that he cried out in agony. But the girls called out: ‘Come quickly, the tide is coming.’ They stopped its motion by song-magic. ‘Hurry,’ they called out. Tjinimin was finding the kangaroo very heavy, and asked them to help him. ‘No, no,’ they called, ‘hurry. There is no water yet. The tide is shallow.’ When they were on the other side of the creek they ran away. But the tide caught Tjinimin. It swept him away. The kangaroo, and his spear, womerah, pubic covering and firestick were all lost.

(10) Tjinimin, still alive, put his feet on dry ground at Panyida, where there are rocks. He tried to make fire but, being without a firestick, failed. Taking [finding?] a new spear and womerah, he killed a kangaroo, and made a pubic-covering from its hair. Then he saw the smoke of a fire a long way away. He suspected that it had been made by the Pilitman women.

(11) He camped twice before he came close to it, and saw them sitting on a high hilltop. He called out to them: ‘Which way do I climb up?’ The women pointed to a steep cliff, saying: ‘You must go there.’ Tjinimin tried to climb the cliff by many different ways, but failed each 198time. ‘You must make a rope and throw it down to me,’ he cried out. The women made a rope and let it down the cliff. They said to Tjinimin: ‘You hold the rope and we will pull you up.’ They pulled him up, up, up, almost to the top. Then they cut the rope. Tjinimin fell on to the rocks far below. He broke the bones of his legs, arms, shoulders and head.

(12) [But he was clever, and full of tricks; the breath did not leave his body. He mended his own bones. Then he stretched himself, trying his limbs and muscles. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘I had a good sleep. Those two women did not wake me up.’] Now he went another way.

(13) Tjinimin broke a piece of white stone (malawat) and with it tried to cut his nose. The stone was too blunt. He tried another; it too was blunt; he threw it away. He went to Tagundjiya, and tried the stone there. It was no good. At another place, Toinying, he found a long stone. It was good; it cut sharply through his nose. He lay down and, by magic, restored his nose. ‘Oh, it is good.’

(14) Now he returned to Kimul, where Kunmanggur was. Kunmanggur said: ‘My son, Kadu Punj, is returning.’ Tjinimin stayed for one day. Then he said to his father: ‘I am going that way.’ ‘Where?’ Tjinimin pointed to the north. ‘I am going for a bamboo’ (spear-shaft?, drone-pipe?).

[He found his naŋgun, Kiniming, The Black Hawk, at Pulupulu. Tjinimin was troubled by his bones. Kiniming asked him what was the matter. Tjinimin blamed the two women: ‘No one looked after me; I fell down on the stones.’ Kiniming gave him a bamboo (spear-shaft?) and asked if he had a spear-point. Tjinimin said: ‘Yes, I have a spear; it belongs to my father; I will put this stone-point on it.’ No one found out that it was his own spear.]

[Tjinimin went to a far place to search for a bamboo spear-shaft. He tried a malawat stone; it broke in half. He said: ‘I will leave here (to find) a good stone.’ Again he went a long way. At the place called Kuradagunda he made another spear but the shaft broke. He tried another; it broke. Then Tjinimin fitted a malawat stone to a spear, straightened the bamboo shaft, and bound it with waxed string. Taking the spear he went on and on, to Kimul, to that place where all came out.]199

(14) He visited all the people. He said to them: ‘Hear! We shall all dance at the open place at Kimul. Kanamgek, The Old One, The Leader-Friend, is there.’

He gathered all the people, and they went towards Kimul. He said to Maminmanga, The Diver-Bird: ‘I cannot leave you here; you are the singing-man; you must come with me.’ Maminmanga brought a big bamboo for Kunmanggur. Tjinimin called to come Kularkur The Brolga, the skilful dancer; Mundoigoi The Turkey; Tjimeri The Jabiru; The Ducks Laidpar and Ngulpi; and the Black Kalawipi (unidentifiable) for the women’s dance (mamburki). They all went, and came out at Kimul.

(15) Tjinimin made fire all the way along the tops of hills. Kunmanggur, seeing the the smoke, said: ‘Oh, Tjinimin returns.’ All the tribes went with him. They were a great many, stretching over a great distance. Tjinimin went first to Kunmanggur, who asked him: ‘What news?’ (murin). Tjinimin replied: ‘Many, many people are coming to dance. We shall have a big waŋga.’

(16) Maminmanga gave the drone-pipe to Kunmanggur and said: ‘I will sing.’ Kunmanggur began to play kidnork, kidnork, kidnork!, and Maminmanga to sing:

(17) Tjinimin danced. All danced. Tjinimin came close. All were dancing. The two Pilitman girls came and sat close to their father. Kunmanggur said to his son: ‘Which way have you come?’ Tjinimin replied: ‘I have come from Mungiri.’ ‘You have brought something?’ ‘Nothing.’ He had brought only his fire-stick and womerah. He had

200hidden his spear. The two girls were there now, with their father. [They had told Kunmanggur what Tjinimin had done.]

(18) There were many people, and much noise. Tjinimin danced so as to make the women desire him. He and Kularkur were the leaders. With many tricks and artifices, they danced close to the singing-man. Then Tjinimin spoke swiftly in the Wagaman language: ‘I am going to kill your father, I am going to kill your father.’ People did not understand, and said: ‘What is it you say?’ Tjinimin answered: ‘I told Walumuma to get me water.’ Walumuma went to get water for him, carrying it in her hands. Tjinimin spilled the water without drinking.

Again Maminmanga began to sing, Kanamgek to blow his pipe, and Tjinimin to dance. As he danced he called out swiftly: ‘I am going to kill your father.’ Again he spoke in the Wagaman language and not understanding, people asked: ‘What is it you say?’ Tjinimin replied: ‘I said, ‘bring me good water to drink.’ ‘Walumuma brought him water in a water-carrier. Again Tjinimin spilled it, and again Kunmanggur blew his pipe, Maminmanga sang, and Tjinimin danced. As he danced he drew the hidden spear towards him by his toes. Again he spoke swiftly in Wagaman; again they asked him what he had said; again he said that he wanted water to drink. To himself, he said, without words: ‘Not long now. From this place I will throw the spear.’ He went on calling for water and when they brought it he would spill it.

(19) Now all were tiring. They said: ‘How many more times shall we dance?’ They counted three times more. Kunmanggur blew his pipe, Maminmanga sang, Tjinimin danced. ‘Soon I will spear your father.’ ‘What is that you say?’ ‘Bring me good water quickly for I am hot from dancing.’ Walumuma ran and filled a water-carrier. ‘How many more dances?’ ‘Two more!’ Kunmanggur blew; Maminmanga sang … and then he stopped. Tjinimin ran in darkness close to the spear and privily moved it nearer. He said to himself: ‘Not long now, and I will throw it.’ All said to him: ‘What is that you say? Is the water there?’ Tjinimin replied: ‘Dance once more!’

(20) Now, the other people danced, but Tjinimin ran to the spear, grasped it and came close. While they danced that time, and 201Kunmanggur blew his pipe, Tjinimin came close and did that thing. Prrp! (the sound of the womerah). Trrr! (the sound of the spear). (It hit) there in the back!

(21) ‘Yeeeeee!’ cried Kunmanggur. He threw the drone-pipe in the water there. Pub! (the sound of falling). The Old One, The Friend-Leader, is finished.

(22) Walet, The Flying Foxes, transformed on the instant, flew away into the air, crying ‘Eeeee!’. All the birds flew away. The children of Kunmanggur cried out in grief.

[Tjinimin ran from that place, and, standing afar off, looked back, wondering what they would do. But no one revenged themselves upon him.] They all cried out in grief, and went another way (flying, spreading out).

(23) The Old One rolled about (in agony). He plunged into the water at Maiyiwa. Bu! (the sound of plunging into water). He cried out to his son, Nindji, The Black Flying Fox: ‘Pull out the spear.’ Nindji did as his father bid. ‘Throw it.’ Nindji threw it afar. That spear is now at Toinying.

(24) He stayed at Maiyiwa for one moon. They made fire and put hot stones to his wound but to no avail; it did not heal; and water came out through the fire. ‘I cannot recover; better I should go away from here.’ So from there he went to the rock shelter at Purmi, where the great baobab is that comes from him. But he was still sick and, taking with him all his sons, The Flying Foxes, he went on.

[The myth then lists a large number of places—of which I recorded thirty—which the dying Kunmanggur visited. At each place he rested, hoping for a soft-lying place, that his wound would heal; but at each place he met disappointment, and felt death coming nearer. At many, but not all, places his wives and sons dug a hole in the ground, made a fire to heat stones, and tried fruitlessly to staunch his bleeding wounds, and at each such place water came up through the flames. At many places Kunmanggur performed many feats of wonder; as at Kulindang, where he left one of his three testicles; or at Kiringjingin, where he left his signs, in the shape of a body and footprints, on the wall of a vast cave; or at Dirinbilin, where his blood still seeps out through the rocks 202and water. At other places he left personal possessions: his stone-axe and fishing net at Kiringjingin, and his forehead-band at Kandiwuli in a pool of glass-like water. At last he turned towards the sea, eventually reaching a place which the myth leaves uncertain, but somewhere near Blunder Bay on the lower Victoria River.]

(25) Now Kunmanggur said to Pilirin, The Kestrel: ‘Hear! I am hungry for flesh-food. You hunt flesh for me!’ So Pilirin took his spear and went. He speared a kangaroo, roasting it at Palkanmi. But Kunmanggur was now wearied and angry from his sickness. Slowly he gathered all the fire from that place and stood it on his head as though it were a head-dress (mutura). [The people said to him: ‘Why do you do that?’ He replied to them: ‘Stay silent; I shall take this fire forever for myself.’] He entered the water close to Doitpir. Slowly the water rose upon him to here … to here … to here … The people cried out to Kadpur The Butcher Bird: ‘He intends to take that fire into the water there!’ Kadpur cried out to Pilirin: ‘Kai-i-i-i, kai-i-i-i, kai-i-i-i!’ Pilirin heard the hail all the vast distance from Palkanmi. ‘Someone is calling out from there. What is (the unknown) trouble? I think it is (about) The Old One. I think they have lost The Old One, The Leader-Friend.’ He ran all the way to that place, ran without pause, and stopped only when he had come close.

(26) Kunmanggur was now far out. The water rose on him to here … to here … to here … it was up to his chest. He went to the place known as Lalalarda, where he pushed out his legs to make the creek. Kadpur cried out to Pilirin: ‘The Old One has taken all the fire into the water. Hasten after him!’ Kadpur ran (flew) swiftly to where only the fiery head-dress could now be seen. He ran (flew) to where the water was beginning to cover Kunmanggur’s head. Pit! (the sound of snatching). He snatched the fire out of the water. But Kunmanggur’s fire was out! Finished!

(27) Pilirin ran (flew) close to the people. He made fire with firesticks—this was the first time men had used fire-sticks (i.e. the firedrill). He set fire to the grass on all sides. To this day all that country looks fire-scorched. That is from what Pilirin did.203

(28) Kunmanggur thrashed around in the water and made it turbulent with foam. He thrust out his legs! Now a creek is there. That place is Tjuliyel. He thrust out his legs! Now at Purulunjnu and Turubilin little creeks are there. He rolled about! Now came that big creek men call Doitpir. Where he splashed about at Mendiputj men now swim across straightway to Kudunnyinggal.

That place at Doitpir, where he went into the water, is da lurutj kalegale ya kalegale (‘place’ + ‘mighty, strong’ + ‘mother, mother’ + intensive particle + ‘mother, mother’)!

5. Palimpsest and Overscript

Our concern is not with the myth as a tale or fable as such, or even as a literary form. Rather is it with the respect in which the myth is a kind of essay in self-understanding. A difficulty from this point of view is its historical standing.

The fact that many myths may be remembered and told at a given time, or over a period, is not evidence that they all have the same standing. The matter is clearly one that requires caution and an absence of priorism. The dissociation of the myth of Kunmanggur from any extant or recent rite—a demonstrable fact—could suggest its obsolescence. Were that the case then its lack of appeal to the living Aborigines becomes the more readily understandable. The symbolic images through which its truths, whatever they be, timeless or timely, are expressed, themselves being dated, would of course be more than ordinarily obscure. Several lines of inquiry inclined me to conclude that this was so.

In a prolonged study of the myth, I found that it impinged rather more widely and deeply on the mystical beliefs of the Murinbata than any other, but the evidence was diffuse and refractory. I could assign the myth no precise place in the life of sentiment or action. One thing only set it apart from other myths not associated with rites: the well-remembered connection with rock-paintings at Purmi and Kirindjingin. 204But the Aborigines who went with me to see the paintings looked on them with no show of emotion. The story of the myth seemed to have an intrinsic interest for the Aborigines but, as far as I could judge from their statements and conduct, perhaps no greater interest than others. However, its narration did not lead to expressions of sorrow and pity, as with the myth of The Old Woman. Many experiments led me to conclude that there was no prospect of settling with certainty a number of matters which, from rational considerations, seemed important: the occasions of telling, the preferences for variant statements, shared notions of significance and import, the classes most familiar with the myth, and the like. On numberless occasions I turned inquiry towards such questions, hoping for the sudden illuminations that so often come if one patiently uses indirect means of inquiry. I left the region not a little puzzled by the standing and function of the myth.

A second, and more puzzling, difficulty emerged. The picture of Kunmanggur built up by the things that narrators of the myth actually said, was perhaps rather flat, but at least it had a certain unity. It was the picture of a beneficent culture-hero, a great man of superhuman size and powers: the ancestor who ‘made us all’ and still ‘looks after people’; the father’s father of the Kartjin moiety and the mother’s father of the Tiwunggu moiety. That unity was greatly weakened when, in hope to add to the depth, I sought to draw on the large amount of contextual information that resulted from protracted inquiry. Kunmanggur then came to seem a momentary convention of a figure about whose sex, unity and beneficence many doubts clustered. It was as though things written on a palimpsest were emerging to cast into doubt, if not to contradict, what had appeared to be an overlying fair copy. The following summary brings out the dubieties.

(a) There was a hint in some statements that The Oldest One may not have been Kunmanggur but someone else—a woman—or, if it were Kunmanggur, then ‘he’ may have been bi-sexual. A pristine female, often called Kulaitj Mutjingga (literally, The Oldest Woman), was associated with sea-mist. The darkest band of the rainbow was sometimes referred to as Kulaitj, or Kirindilyin, and was then identified with the wife of 205Kunmanggur and the mother of Kanamgek. Even those who asserted the maleness of Kunmanggur said that he had large breasts, like a woman’s. I found it impossible to reconcile the differences.

(b) There was a fairly persistent suggestion that Kunmanggur and Kanamgek were not identical. One informant (on whom I found I could not rely) insisted there were two brothers Kunmanggur. I also heard of Kanamgek as the son of Kunmanggur, and of their having died in different places. It was a matter of common agreement that Kunmanggur was married, but opinion varied about the number and names of his wives. The name Kirindilyin was used less commonly than that of Ngamur.15 There was a consensus that there were two wives, one of whom was Ngamur. The name of the other was suggested many times as Walumuma, The Blue-tongued Lizard. But it was about as common to have Walumuma suggested as Kunmanggur’s daughter and Tjinimin’s sister. I made many efforts to reconcile the statements, both by wide inquisition and by using sketches of the rainbow drawn by the Aborigines themselves. Little success attended the attempts.

All manifestations of the rainbow were represented primarily as signs left or made by Kunmanggur. I could not induce informants to go much beyond saying that any manifestation of a rainbow is ‘his spit,’ ‘his tongue,’ or ‘water spat through his drone-pipe’ (maluk). The last statement was usually accompanied by an explanation that the water contains flying-foxes and spirit-children (ŋaritŋarit).

The spectrum of colours in a rainbow is divided by the Murinbata into three bands (violet-blue, green-yellow, orange-red). The darkest band was variably identified as Kunmanggur, Kirindilyin, Ngamur, or Kulaitj. Or the top band might be identified as Kunmanggur, the middle as his drone pipe, and the lowest as Kanamgek. It was commonly suggested that Ngamur was older (kulaitj) than Kunmanggur, and may have been married—to someone nameless—before marrying him. She was represented as a black snake in the sea, the sea (laliŋgin) being The Child of River (ŋipilin) and sea-noises being the crying of the child for its mother. I attempted to follow through all the hints but found that to

206do so was soon to become lost in deeps beyond an inchoate deep. In the end, I had to conclude that the difficulties were irreconcilable. They may arise from the fact that the rainbow, the chief sign, being visibly and variably differentiated in numbers, is a stimulus to imagination. The differentiations may invite imaginative speculation and, on the evidence, appear to receive it.

(c) Kunmanggur was always represented as having been in life a huge person, likened to a baobab tree in size, and of great strength and superhuman powers. It was implied that he was mild and beneficent. After the transformation, he ‘came back’ as a prodigious serpent, with sharp protuberances on his spine and a long tail that curves scorpion-like over his back. The tail ends in a hook (kandinin). Evidently, there was a change of temper too. In the transmogrified form he was reputed to be fierce (mulak). It was said that, using his hooked tail, he lies in wait for people in deep waters, with some ill-disposition towards them, and may ‘sting’ or ‘bite’ or ‘pull’ them unless restrained by Ngamur. The two sit back-to-back, especially at river-crossings. Ngamur, seeing the approach of travellers, and wishing to help them, changes her position (hence causing the swirl of whirlpools) so as to face and guard those who use the crossings. Both Kunmanggur and Ngamur were said to ‘bite’ evil-doers, especially warlocks.16

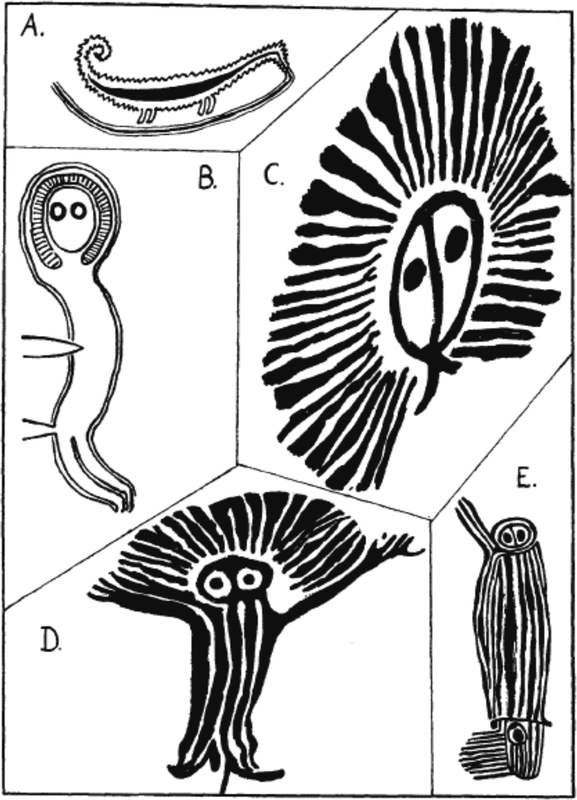

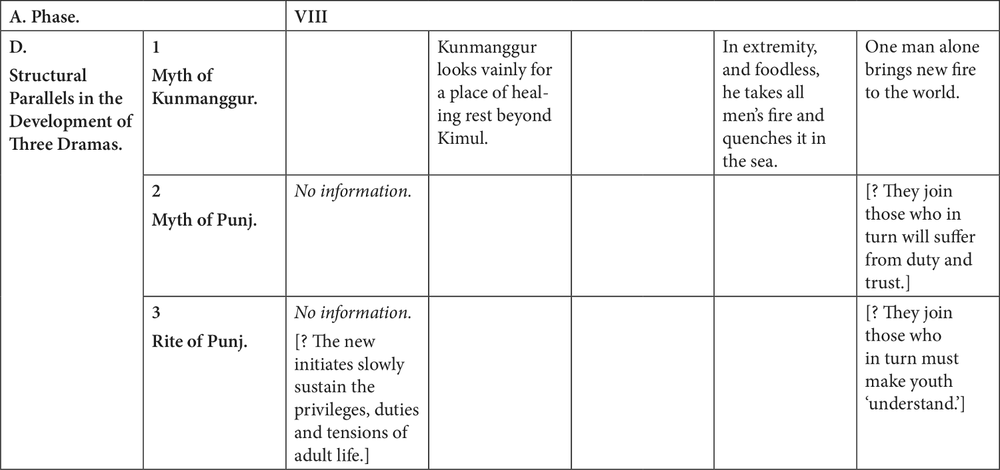

(d) Kunmanggur was represented visually in five different fashions: (i) as a scorpion-like creature in which there is no human suggestion (Pl. I, A); (ii) in a somewhat stylised human form, with a spear piercing his side and arms conventionalised so as to merge with a fish-net forming a kind of aureola around his head (Pl. I, B); (iii) as a head only drawn in a sparse but brilliant geometric style, a circle with radial lines (Pl. I, C);

207(iv) as a complete figure (D) drawn somewhat in the style of (C); and (v) as a complete figure drawn in an elongate geometric style (Pl. I, E).

(e) There were mutually contradictory views about Kunmanggur’s ætiology. He was spoken of as (i) kadu baŋambitj, a ‘self-finding’ person (i.e. self-creating and self-subsistent), an important division that runs through all the beings of the Murinbata theophany; (ii) as kadu mundak, ‘man-before’ or ‘man-ancient,’ a true man though possessing powers that men no longer have; (iii) as kulaitj, the first and oldest man; and (iv) as possibly having parents.

(f) I concluded from discussions that his relations with, and position vis-à-vis, certain other mythological beings, was surrounded by irresoluble doubt. He was said to be ‘bigger’ (i.e. in power and authority) than Mutjungga, The Old Woman, the central figure of the cult of Punj. But no one would say confidently that he is ‘bigger’ than Kukpi, The Snake Woman, the great song-maker and giver of spring-waters. Nor would anyone affirm his relationship and position in respect of Nogamain, another self-subsistent spirit reputed to be the sender of honey and beautiful children, and the only being to whom the Murinbata address something like an invocation. At the same time it is often said: ‘Kanamgek manyiwata da mundak’ (lit. ‘Kanamgek,’ ‘made us all,’ ‘anciently’). He was also commonly reputed to be the mystical source of spirit-children, flowers, rain, fish, flying-foxes, and the general increase of nature, as well as the maker of deep pools of fresh water found along his sacred path.

In this situation I came to think of the myth, however told, as itself being an attempt to systematise a throng of visionary shapes set up by mythopoeic thought over an unknown period, so that in any version at any time only some of the many possibilities are used. How many may have been used or neglected by different narrators at different times, and whether the core-story has remained constant, it seemed impossible to say.208

Figure 5. Five Visions of the Rainbow Serpent

If the myth is an attempt to systematise tenuously-connected visions, what is the principle or method of the system? My thesis is that 209myths of the kind are best understandable as allegory and, ultimately, as a sort of poesy. The criteria of selection from the stock of possibilities must have been, in the broadest sense, artistic, not intellectualistic. The discovery by an external observer that the myths are full of ambiguity, paradox, antinomy and other such obscurities is the product of an intellectual—and therefore misguided—criticism of the artistic-poetic process. If there is a principle then it is one of artistic appositeness, not one of conceptual rationality.

The evidence of method is the fact of arrangement into a story. But the problem of study then puts a conventional anthropology under strain. The task may be stated as follows: to study the use of archaic and current language, in a religious situation, to tell a drama in story-form in a manner consistent artistically with allegory and poesy. A ‘scientific’ approach is, plainly, as inappropriate as a ‘science’ of poetry. The necessary methods—analytic abstraction, an empirical concern, and an indicative language—are simply left transcended. To say so is not to put mythology ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ study, or to question the possibility or usefulness of studying the historical setting of myths, their particular uses of language, their reflections of social structure, their functions in social life, and the like. But such studies take as given the human experiences about which the myths make allegorical statements. The light that results does not fall on the stratum of the experiences. To reach the experiences one has to penetrate below the stratum on which expressed mythopoeic thought deals with them. The experiences are on one stratum; the perceptions of them, and the judgments about them, which are given symbolical expression—whether in speech, gesture, stance, dance, mime or song—are on another. The symbolical expressions are not the quiddity of the experiences.

Thus myths, like poetry, are doubtless efforts at self-understanding, but they may not be studied as works of understanding which have been thought up and perfected by conscious means under the control of intellectual canons. Where there is a demonstrable connection, or an organic relation, between a myth and a rite, so that one can speak of the myth of a rite, and where the rite can be analysed to the shapely 210constituents which (in the case of Punj) are identifiable as ‘operations,’ then one has a design-plan, exhibited by things one can see, to use to test the design-plan of the myth. There is no such aid at hand with the myth of Kunmanggur. One has to take a leap in the dark.

For here is a myth standing alone as though it were a monument to something forgotten but vaguely familiar, and rife with suggestive silences. Tjinimin’s crime against his sisters is simply postulated, and left at that. But were the sisters truly innocents? They knew the rule on incest but did not comprehend his sexuality! Did Tjinimin, awakening as from a sleep, forget what he had done and suffered? From what motive did he go on to heal, mutilate and again heal himself? And then seek his father’s death? Why did not Kunmanggur rebuke him? And did Kunmanggur condone his own death? Was it for this reason that Tjinimin was allowed to go unmolested? The questions, let alone the answers, are not formulated. The myth scarcely ventures beyond externals. But the silences are heavy, and a sense of obscure paradox obtrudes, especially in the climax-events. At last, Tjinimin alienates himself wholly from kin and kith, flees into the night, and looks back wonderingly—we are not told sorrowfully—at a world on that instant being transformed by the founding-mystery of things … Kunmanggur, tenderly used by those who stay, puts all the world’s fire upon his head and seeks to take it away, according to one version to try to keep it for himself forever and, according to another, with a promise to bring it back … It can scarcely be doubted that propositional and moral truths are being stated, but what are they? The kerygma of the myth lies obscurely within the paradoxes. One has the sense that antinomies have been stated that would lose their import if their parts could be separated. The son’s animus towards the father, and the father’s intent towards the son, are left dark. Kunmanggur’s intent towards the world he is about to quit is left quite fathomless. There is a hint of suicide for, although mortally hurt, he walked purposefully into the sea. Yet his death was not a death for, transmogrified into The Rainbow Serpent, he ‘comes back’ to make his mark on the sky as a sign that he ‘looks after’ people. The place of his last earthly struggle is commemorated by a symbol of femaleness! Not 211even the firm outlines of unconditioned evil or positive goodwill can be made out. It is as though paradox and antinomy were the marrow in the story’s bones. And, among the Aborigines who are alive, Tjinimin is not execrated and Kunmanggur not mourned: all one can detect is a certain amusement about the memory of one and a certain warmth about the memory of the other.

In earlier papers it was suggested that the rite of Punj Was wrapped around a kind of affective and cognitive prevision of continuing tragedy in human affairs, the myth of The Old Woman being its allegory, almost, one might say, its intellectual aftervision. The two visions were shown to have congruent plan-structures. The ‘leap in the dark’ one must take towards the myth of Kunmanggur may be put as an hypothesis: the same congruence of structure extends also to it.212

6. Analysis of a Riteless Myth

The design-plan of the whole drama is perhaps best shown by a contraction and restatement of the sequence of incidents, which fall into eight natural phases. Certain structural patterns then become visible.

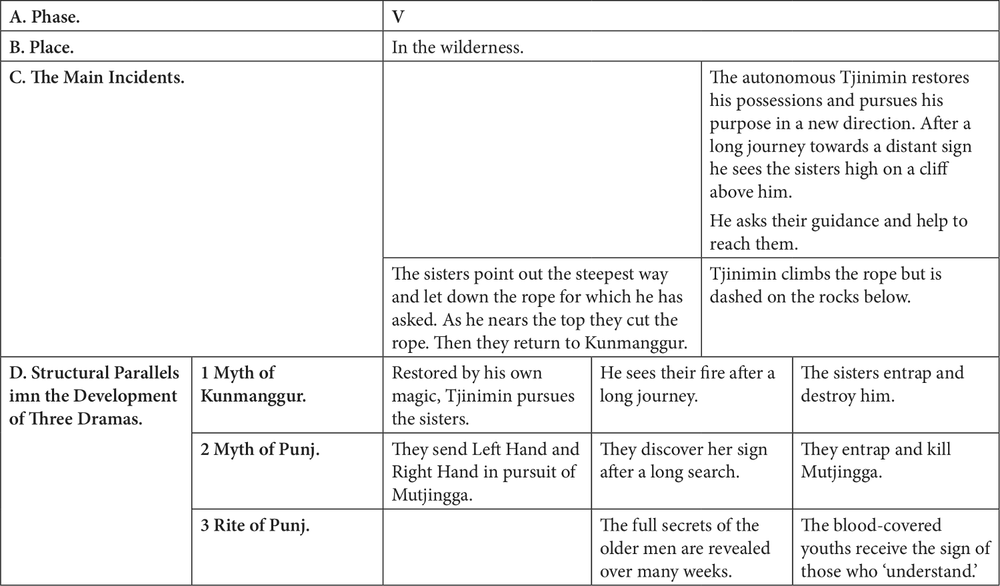

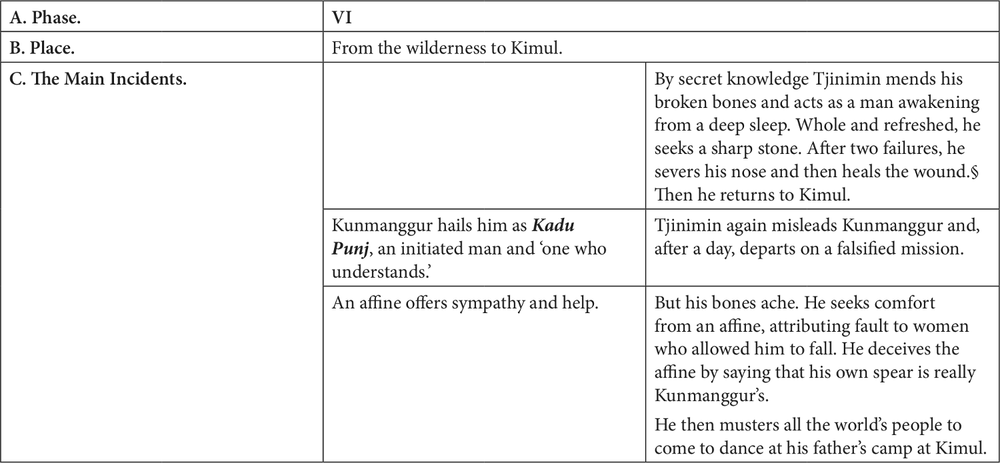

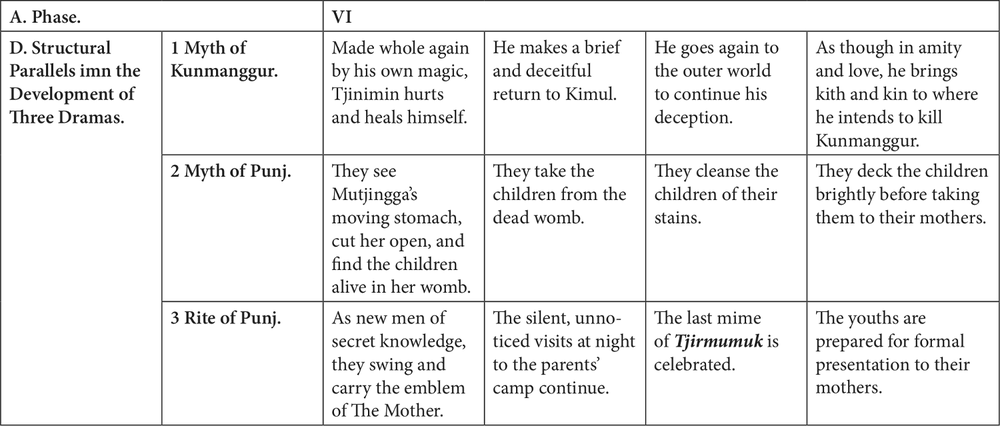

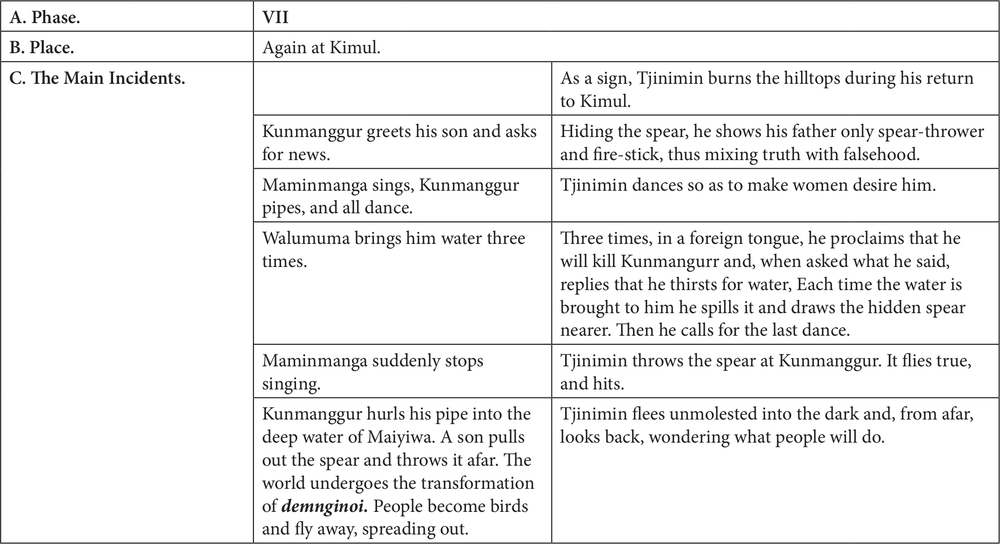

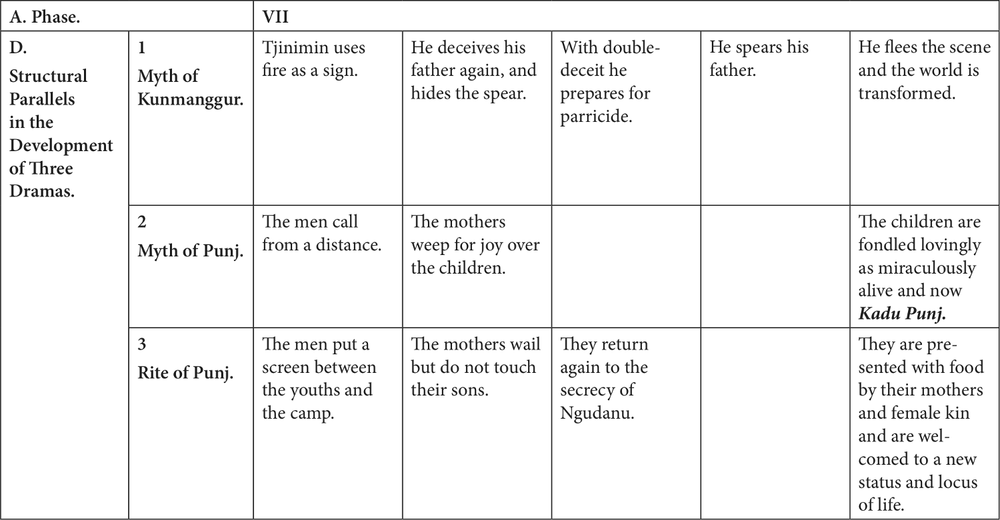

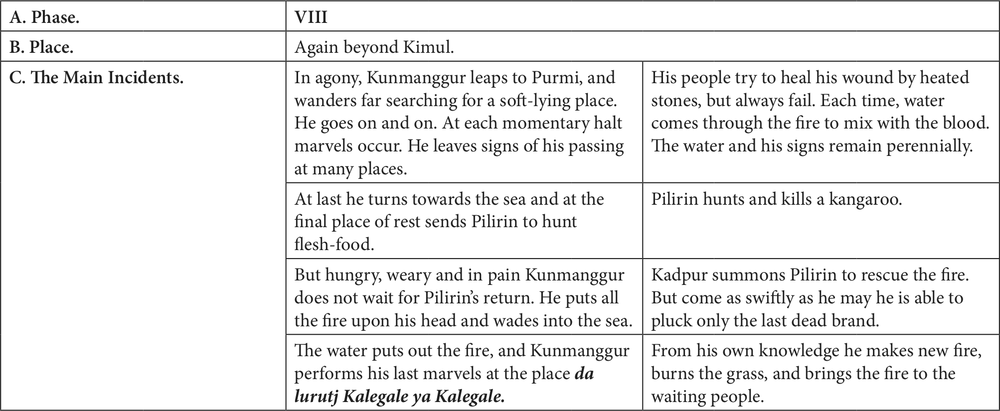

Table 5. Structural Plans Of Three Dramas

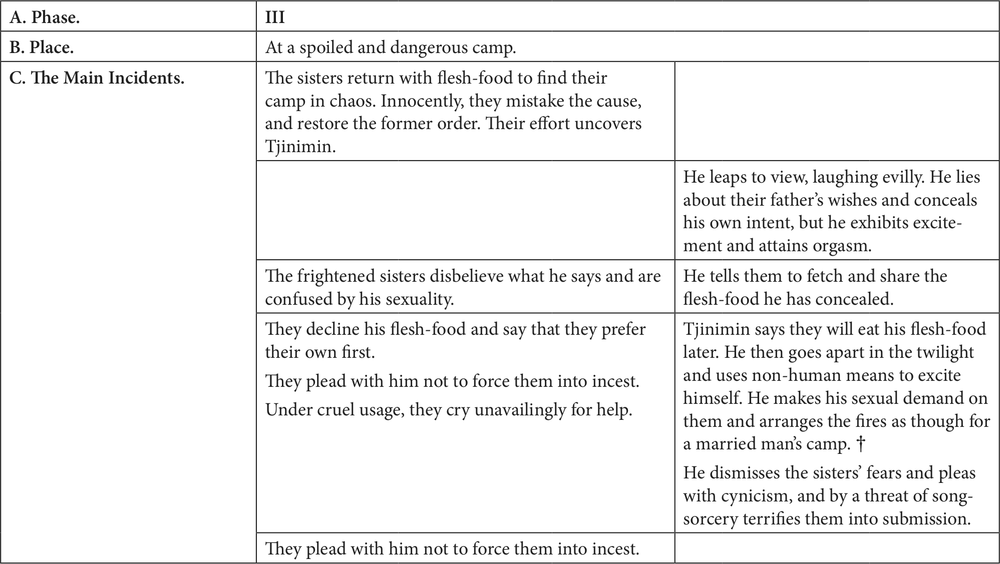

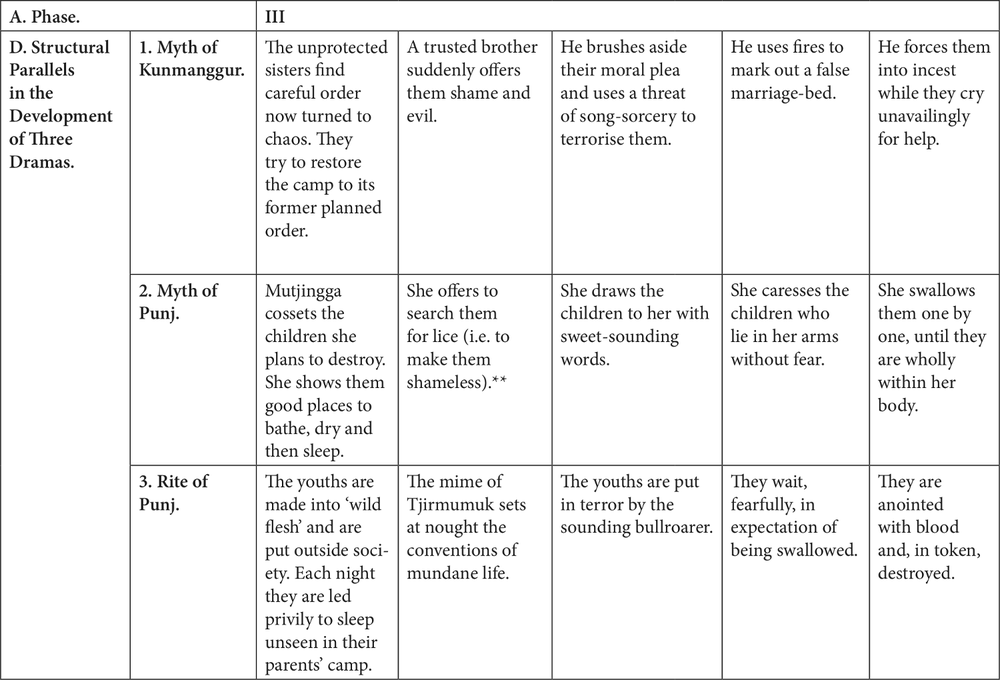

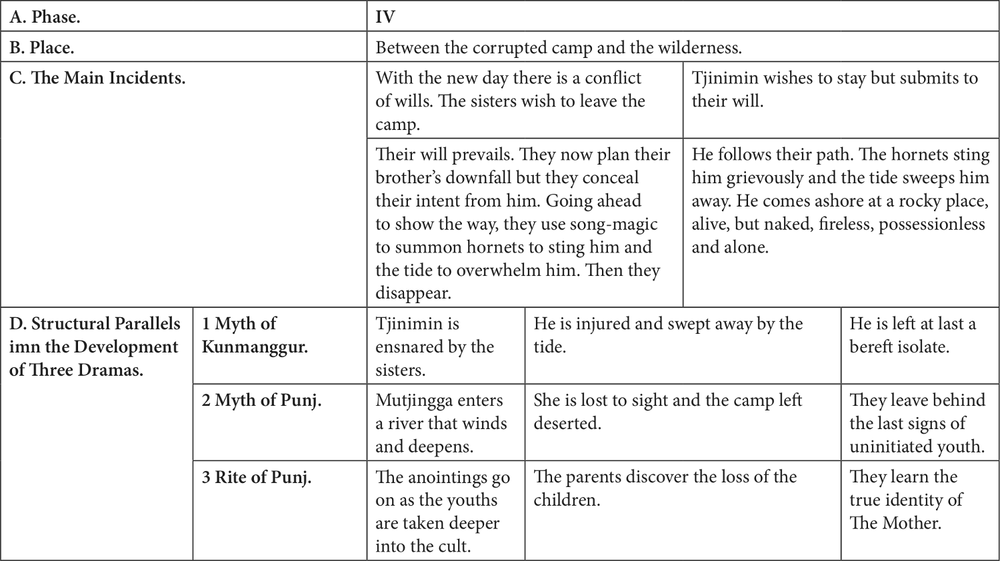

| A. Phase. | I | ||

| B. Place. | Kunmanggur’s home - camp at Kimul. | ||

| C. The Main Incidents. | The Pilitman sisters hunger. They ask and receive Kunmanggur’s permission to go far from home to find food. He gives them an added task—to plant trees* on the island of Nganangur. | Tjinimin lusts secretly after his sisters. He asks and receives Kunmanggur’s permission to go far from home to visit kinsmen.† He does not mention any place. Kunmanggur leaves him free of his purpose. | |

| D. Structural Parallels in the Development of Three Dramas. | 1. Myth of Kunmanggur. | Children lack things of life; they seek to go away from camp; father imposes a task on daughters but leaves son free; daughters acquiesce, and son conceals evil private motive. | |

| 2. Myth of Punj. | Parents lack food; they decide publicly to hunt; they entrust their children to Mutjingga’s care; the children acquiesce voicelessly; Mutjingga makes a secret act of ill will. | ||

| 3. Rite of Punj. | Growing youths lack understanding; older men decide secretly to initiate them, and entrust them to initiators who keep the intent secret; the youths acquiesce in duties of silence and submission.213 | ||

| A. Phase. | II | ||

| B. Place. | Beyond Kimul. | ||

| C. The Main Incidents. | The sisters leave in trust, amity and duty. They go unescorted by familiar places to a known and distant destination. They hunt and work together and make a camp co-operatively. They then go on to hunt flesh-food but leave the untended camp ritually dangerous with their blood. | Tjinimin follows the sisters with evil intent. He hunts and works alone. He finds their path, loses it, finds it once more, and then discovers their camp. He conceals his flesh-food. The blood excites him sexually.‡ He destroys their work and, sleeping and waking, hides in wait. | |

| D. Structural Parallels in the Development of Three Dramas. | 1. Myth of Kunmanggur. | The children go away from camp, the sisters to familiar places on agreed tasks, the brother to an unknown destination on a falsified task. The evil purpose shows itself away from the eyes of the trusting father, who stays behind. | |

| 2. Myth of Punj. | The children are left in a safe, known place with a guardian who, intent on evil, acts with duplicity as soon as the trusting parents leave camp to follow out their declared and necessary task. | ||

| 3. Rite of Punj. | Growing youths lack understanding; older men decide secretly to initiate them, and entrust them to initiators who keep the intent secret; the youths acquiesce in duties of silence and submission.214 | ||

215

215

217

217

218

218

219

219

220

220

221

221

222

222

223

223

* Baobab trees are said to be ‘Kunmanggur’s children.’

† Classificatory affines.

‡ A double enormity by Tjinimin, to have been excited by female blood and by his sister’s blood.

** A shameless person is colloquially called kadu managga mimbi, ‘one without head-lice.’

224In Table 1 the development of the drama of Kunmanggur is shown in the eight phases (Col. A, I–VIII) which are made more or less distinct by the myth. Each phase is associated with a place or region (Col. B) and with a set of events (Col. C). Those events are divided into two groups in order to bring out more clearly the curious yet characteristic oppositeness that, almost throughout, marks the conduct of the principals. The entries in Col. C are a virtual summary of the myth. In Col. D, separated by double lines, a further contraction and construction of the myth is set alongside comparable reductions of the myth and rite of Punj, which were analysed in earlier papers. A few rearrangements and constructions were found necessary, but I hope to have avoided any serious interference with the material.

On the evidence of the table, there is not much room for doubt, while making allowance for possibly unconscious selections on my part, that there is a significant measure of congruence between the design-plans of the two myths and the rite. It is not by any means a complete congruence, and it is stronger at the beginning than at the end, but the common elements are too many, and the articulations too similar, to be dismissed lightly. The structures are homomorphic.

(a) The sequence of phases and places (Columns A, B) are strikingly like those found in the other myth and its rite. The transitions correspond quite closely.

Someone is sent or withdraws from a safe, habited place to a place of solitude. In the second place—the place of removal, or in the place deserted—wildness or terror, and a sort of corruption, become ascendant. Something—trust, young life, innocence—is destroyed there. Then, after a pause, there is a return to the first place. But it is now not the same as before; there has been a change; the old is not quite annulled and the new not altogether unfamiliar.

In terms of phases and places, without reference to incidents, the structure of the transitions from Kimul to Kimul-and-beyond (Col. D, 1) appears identical with that from the camp with The Mother to the camp from which she has gone (Col. D, 2) and from the camp of 225circumcised youths to the camp of men who ‘understand’ (Col. D, 3). A comparison of incidents strengthens that conclusion.

(b) All three design-plans begin with common situations of life: a felt need of food, materials, or mundane things of life; a desire to nurture or develop life; the demands made on life by, and by life on, young males. The metaphor of expression varies but the expressions appear equivalent, indeed interchangeable.

However phrased, the situations are depicted as tense, flawed by ambiguity or duplicity or duality, and issuing in acts of necessary trust to which duty is added. Tension, flaw, trust and duty develop together so as to make for a disaster. But the disaster is consummated by a good outcome. The outcome in its turn has something dual or duplex or ambiguous about it. In other words, the good is conditioned. Fire, that which serves and burns, stays with men only by The Father’s death; young life is conserved only by the death of The Mother; understanding is attained only by fear and disciplined suffering under authority. And fire, life and understanding all need renewal from time to time.

(c) Each drama develops by its own internal dynamism, without dependence on externals. The stories in each case are of what men do to men and to themselves, not of what gods or suprahuman agencies do to them. The unfolding is from within, by a dialectic within which people are caught by the nature of their own condition and character.

(d) In each case the principals fall into three groups. There are (i) those who suffer, (ii) those who inflict suffering, and (iii) those who so to speak stand and wait, suffering vicariously.

The sufferers live to see the downfall of the inflictors and, in turn, become inflictors. It is suggested, in a shadowy way, that persons in one category pass into the other categories in the course of time. Thus, the ill-used sisters bring hurt and desolation to Tjinimin, and then sit silently while he encompasses Kunmanggur’s death. Tjinimin, having been both sufferer and inflictor, stays alive—to watch the development of the marvels and grief he has brought to others? The suffering Kunmanggur tries to inflict loss on the guiltless, and then passes from ordinary life to keep watch over all. Mutjingga inflicts harm on the young, suffers death, 226and then becomes a real—and sorrowing?—presence at Ngudanu. The transitions are not stated with complete or explicit clarity, but the background suggestions are quite strong.

Thus, in four fundamentals—the sequences of transition, the development of common situations, the internal dynamism of the plots, and the relationships between principals—there are distinct resonances between the dramas. A consideration of incident suggests the virtual equivalence of each drama as a whole. In principle, and in most of the major details, the myth of Kunmanggur evidently could stand to the rite of Punj in approximately the same relation as the myth of Mutjingga.

The question arises: three dramas or one? But the same question, overturned, may be asked of the myth of Kunmanggur: one drama or several? It is noticeable that the story of IV is almost a reversal of the story of I–III, but with Tjinimin in the position of sufferer and the sisters dominant. Then V seems to tell, in short, bold strokes, very much the same story as I–III, but now arranged after the fashion of IV. In VI, it is as though the story of I–III were being told all over again in changed metaphors. The last phase, VIII, then develops the whole drama in a way for which a listener is rather unprepared until a familiar pattern emerges: here too is the story of a man, with a mortal defect of life, who acts ambiguously towards his nearest kin, though with an evident intent to hurt, and at the last quits their world. And, from being sufferer, Kunmanggur becomes—at least in intent—the inflictor of suffering until he passes from the world of living men. To become, then, the vicarious sufferer?

One is left with a strong impression that a single, unitary story runs through all three dramas, and that the core-plot would emerge clearly if one could but grasp the principle of commutation between the elements.

The myth of Kunmanggur extends to an eighth phase, but the myth of Mutjingga and the rite of Punj stop at the seventh. One is tempted to conjecture about possible equivalences, in the other myth and the rite, to the ‘again beyond Kimul’ phase of the drama of Kunmanggur. The entries made in Col. D, 2–3, VIII, with that intent, are conjectural and tentative. The ‘beyond’ in those cases can only be the futurity to which 227Kadu Punj return. But the entries suggest what seems the import of the religion: that much of human social life is a flow or movement between coordinate species of experience; that a life of conditional good is one in which people in their turn suffer, inflict suffering, and watch others suffer.

When the three dramas, one acted and two spoken, are set side by side, they suggest that whatever be the historical standing of the myth of Kunmanggur, and whatever its past associations, its kerygma is somehow the most profound. May one not suggest that Aboriginal society is one in which insights can be lost as well as found? Lost, perhaps, in the fervour of new cults? The possibility can hardly be admitted—perhaps even suggest itself—in a viewpoint that would insist on the static and stationary character of Aboriginal culture, society and thought. But there is at least some evidence to suggest that Murinbata religion has been one of dynamism. The strong evidence of a succession of cults in the past has been mentioned. The myth of Kunmanggur, with its poignant complexity, and the splendour of the associated paintings at Purmi and Kirindjingin, are evidential peaks of attainment unmatched by any others in the regional culture of the recent past. We are entitled to look on them as works of passion and imagination, not contrived for effect, but having effect nevertheless.

Perhaps the myth said in words what was speakable about a rite that, dealing—as all rites do—with the unspeakable, had to do so by gesture and movement. Perhaps the paintings, by visual imagery, dealt with what could not be spoken or acted out, but still called on a few minds for expression. If there ever were such a rite, then it may well have had to do with that dialectic of life with which Aboriginal religion is concerned. One may suggest that rite, myth and paintings, each in its own way, brought to equipoise of form the understanding of that time about the transiences that were unavoidable within its permanencies. They are essays in expression, each subject to the limitations of its own kind, but each seizing on the fundamental theme of change within stability.228

We have found no reason so far to differ from, and much reason to agree with, Sir James Frazer’s view that a ‘central mystery of primitive society’ is associated with initiatory rites. But we have tried to show that analysis can go beyond the idea of a ‘drama of death and resurrection.’ That is simply one symbolical expression which is given to the dialectical ritual form. Having found the form in a riteless myth, we shall try next to see if it exists within a mythless rite.

1 Journal Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. LVI.

2 The root is heard in other contexts that make this meaning doubtful. For example, (I) maiyen yibimgek = ‘the road,’ ‘is-there’ (lit. ‘lies-down-there’)+ gek; (2) ngipilin panggoi wurangek = ‘river,’ ‘long,’ ‘goes-one-way’+ gek. As far as I could determine, the root is used only of uniform action along a line or path or in a direction, and takes on a particular meaning from context. The rainbow is usually said to be the tongue or spit of Kunmanggur, but I have heard it described also as water blown from his drone-pipe. Some Aborigines add that the water contains flying-foxes and spirit-children. In the circumstances, one is perhaps wiser to give the root the most general meaning of ‘acts.’ I cannot say with any surety whether it is transitive or intransitive.

3 The use as a verb-form is, however, more common. When a rainbow appears the Murinbata may be heard to say ‘Kanamgek dimgek!’ The coupled words have the sense of ‘he who is-acts continuously, now manifest-acts,’ subject to the qualifications made in the foregoing footnote.

4 T. G. H. Strehlow, Aranda Traditions, 1947, p. xviii.

5 One man, of flamboyant personality and theatrical style, and with political gifts of no mean order, narrated the myth of The Rainbow Serpent for me in a particularly striking fashion. He left the personality of Kunmanggur flat and characterless, but developed the part of Tjinimin, the Bat, with gleeful zest. By vivid gestures, by words and poses that were sometimes obscene, and by evil laughter, he exhibited Tjinimin as having a satanic nature. Such an emphasis is decidedly uncommon. But it is implicit in the more conventional narrations. It thus waits to be evoked by a powerful imagination. The same informant gave circumstantial details of supposed conversations which, in the ordinary telling, are indicated by short phrases only. But the conversations were consistent with what the mythical persons might have said in such situations. It appeared to me a good illustration of processes by which free imagination and human insight, while still obeying the canons of situation, may greatly change the emphasis and tone of a myth, and may even change its content.

6 Op. cit., p. 6.

7 My notes show that my informant referred to Amanggal as the male, and to Agarinyin as the female, one of several varieties of flying-fox. The Marithiel word agarinyin is suspiciously like the Nangiomeri adirminmin and the Wagaman-Murinbata tjinimin, although the four languages are not closely related. Only the Murinbata specify tjinimin as a bat, but I am inclined to think that all the terms refer to that creature, and that my informants said ‘flying fox’ only because of their poor command of English.

8 I could not discover the relation between Djagwut and the ‘low’ rainbow, or between Djagwut and the women. Under the rules of marriage between the sub-sections, either Djagwut or Tjinimin, or both, could have been in the wrong.

9 Many Murinbata resent being told that horticulture and agriculture are unknown to them. They cite Kunmanggur’s instruction to his daughters that ‘making a garden’ is an old Aboriginal custom. They interpret the presence of any natural species in an unexpected place as an intended result of human action in past time. The baobab grows sporadically, sometimes singly, sometimes in clusters, in unpredictable places, and this fact is taken to be evidence of human intent. It is especially plentiful on Nganagur.

10 A sign of initiation. A subsidiary myth relates how Tjinimin had been subincised by Yuwirnga, one of the Flying Fox Brothers. The brothers, Walet and Yurwirnga, had started from Nganarangga to find a good country. They came to a place now known as Karawupman and there made a dreaming-place (ngoiguminggi). At that time Walet had a penis like a man. Yuwirnga took a sharp cutting-stone secretly and subincised Walet, so that he became ngi madaiyin. Later, he did the same to Tjinimin, and later still to all the people to the south (kadu tjiltji). All kadu tjiltji now call those from the north lamatingi, and say that they are not truly men. The Murinbata, who practise circumcision, apply the same term to the uncircumcised tribes to the north of the Daly River.

11 Some informants deny that the girls had fire, and say that the fish was to be eaten raw. It was Tjinimin who had fire ‘because he was man,’ implying that the girls were still birds. The variation suggests some doubt about Tjinimin’s moiety, for the mythology holds that in The Dream Time only Tiwunggu people had fire. The implicit suggestion is that he belonged to the Tiwunggu moiety.

12 One informant, narrating the myth, said at this point, ‘Your kaka (mother’s brother) sent me to find you two.’ Later, he reverted to the statement that Kunmanggur was the father of all three. When I questioned him, he was confused, saying that Tjinimin was a ‘little bit Tjalyeri,’ that is, belonged to the opposite moiety from Kunmanggur. The designation of Kunmanggur as father (yile) or mother’s brother (kaka) seems to vary with the locus of the clan from which informants come. Those from clans nearest the Nangiomeri and Wagaman tend to favour the Tiwunggu moiety as Kunmanggur’s.

13 Yerindi is song-sorcery, of which even sophisticated Aborigines of modern times remain in dread.

14 The Murinbata are unable to give a translation. In all probability the song is in the language of another tribe, or includes archaic Murinbata words. Kawandi is reminiscent of the Djamindjing wandiwandi (an evil, non-human spirit), but mutjingga (old woman) and purima (wife) are Murinbata words.

15 Ngamur is also the name of a particular black snake.

16 I recorded many instances of Aborigines drowned in rivers or in the open sea, all the deaths being attributed to Kunmanggur. The general surmise was that they had been punished by Kunmanggur, who ‘cannot bite for nothing.’ Snakes and crocodiles which attack humans are also supposed to do so as agents, occasionally of Kunmanggur, but of warlocks as well. I have no reason to suppose that the theory of retribution by Kunmanggur is due to the influence of European beliefs.