1

Early advocacy for plain packs

The idea that governments might require all tobacco products to be sold in so-called plain, standardised or generic packs, devoid of any element or feature that might contribute to their attractiveness or allure to smokers or future smokers, can be traced back to Canada in the mid-1980s. Dr Gerry Karr appears to be the first person to have formally proposed the idea in a motion presented at a Canadian Medical Association annual general meeting in June 1986, (20) and David Sweanor, a Canadian tobacco control activist, was recommending it to politicians in 1988. (21) Over the next decade, the proposal received some attention from researchers and advocates in Australia (David Hill and Ron Borland and colleagues) (22), New Zealand (Park Beede, Rob Lawson, Mike Shepherd and Michael Carr-Gregg, (23–26) and a considerable amount of attention in Canada (27, 28).

Carr-Gregg, who headed up a coalition of tobacco control groups in New Zealand, told us he had been told about plain packaging by David Sweanor. The coalition soon promoted the idea to a parliamentary committee sitting and Carr-Gregg says: ‘I remember the expression on the industry’s face when we outlined this at a select committee – they looked apoplectic! One of them rushed out of the room (presumably to phone head office of BAT [British American Tobacco]). I don’t think they saw that coming!’

The vanguard New Zealand government’s Toxic Substances Board 1989 report (29) endorsed a proposal by Murray Laugesen, representing the Coalition Against Tobacco Advertising and Promotion, that cigarettes be sold only in white packs with black text and no colours or logos. This recommendation was not taken up by the government, but the momentum had begun.

In 1990 the conference resolutions at the Seventh World Conference on Tobacco or Health in Perth included one submitted by Canadian advocate Gar Mahood stating:

Generic packaging: given the importance of package designs in promoting tobacco products, this Conference endorses the concept of mandatory generic packaging of all tobacco products, and urges all countries to include generic packaging in their tobacco control legislation. (30)

A similar resolution was passed at the 1994 world conference in Buenos Aires.

A BATCO fax from 1994 summed up these early beginnings, concluding prophetically with ‘the rest is history’ (Figure 1.1).

Early Australian interest

In 1992, the Australian Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy (MCDS) comprising health, police and justice ministers from all eight states and territories, considered a report commissioned by the MCDS Tobacco Taskforce, chaired by Mike Daube. (22) This report recommended that ‘regulations be extended to cover the colours, design and wording of the entire exterior of the pack’. The MCDS report proposed large new warnings and asked for a report on plain packaging. While new, stronger warnings were mandated on all packs from January 1995, the idea of plain packaging did not progress. At that stage the ministers were only prepared to move in a staged process to larger, stronger warnings.

A memo from WD & HO Wills (the BAT company then trading in Australia) noted:

Mike Daube’s influence as chairman of the Tobacco Taskforce reviewing pack labelling in 1991 was a crucial first step in a wider agenda, which, of course, culminated in the CBRC [Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer] Report in 1992. (32)

Daube returned to the plain packaging agenda 17 years later, when he chaired the National Preventative Health Taskforce Tobacco Committee (see pp 18).

In 1993, Cancer Council Australia’s national cancer prevention policy included a recommendation for plain packs. This recommendation was maintained in all six subsequent updates of the policy.

In December 1994, Western Australia’s health minister, Peter Foss, called for the introduction of plain packaging (33) and the Australian Medical Association lobbied for it in 1995. (34)

In September 1997, the Australian government responded to a Senate committee’s recommendation that plain packaging be considered. While not committing in any way to the policy, its careful wording did not close the door on the possibility:

In response to the mounting interest in generic packaging, the Commonwealth obtained advice from the attorney general’s department on the legal and constitutional barriers to generic packaging. This advice indicates that the Commonwealth does possess powers under the constitution to introduce such packaging but that any attempt to use these powers to introduce further tobacco control legislation needs to be considered in the context of the increasingly critical attention being focused on the necessity, appropriateness, justification and basis for regulation by such bodies as the Office of Regulatory Review, the High Court and Senate standing committees. In addition, further regulation needs to be considered in the context of Australia’s international obligations regarding free trade under the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT), and our obligations under international covenants such as the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, and the agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). (35)

As we will see in Chapter 6, the High Court of Australia roundly rejected tobacco companies’ constitutional arguments in 2012 and much legal scholarship has challenged expressed concerns about Australia’s international treaty obligations. (36) However tobacco industry commentary in other countries, and a subsequent withdrawal from an early attempt to introduce such legislation by the Canadian government, may have influenced Australian political thinking at the time. Responding to the Australian Medical Association’s calls for plain packaging, a spokesperson for the then Labor health minister Carmen Lawrence is reported to have said plain packs ‘would breach constitutional requirement for free trade. We would have to buy the tobacco companies’ trademarks, and that would cost us hundreds of millions of dollars.’ (34)

Canadian campaign

In the mid-1990s, Canada went further than any nation and considered introducing plain packaging legislation, with Health Canada commissioning a thumping 427 page expert review. (27) The then Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien had announced in February 1994 a significant rollback of tobacco taxes, after increased tobacco smuggling into Canada occurred via Native American reservations on the US-Canada border. (37) To counter concerns about the impact this would have on the health of Canadians, he promised several compensatory measures, including consideration of plain packaging of cigarettes. Within weeks of this announcement, the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Health launched public hearings into the possible impact and effects of plain packaging.

The tobacco industry responded by launching a coordinated campaign that focused on framing plain packaging as an intellectual property issue; countering health agency research with industry-sponsored expertise (an edited book was produced by the long-time tobacco industry consultant, the late John Luik; (38)) and creating a public debate designed to weaken public support. The tobacco companies Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds worked with former US trade representative Carla Hills and former deputy trade representative Julius Katz to tell the Canadian government that plain packaging would be an ‘unlawful expropriation’ of their trademark rights and that ‘the compensation claims of affected foreign trademark holders would be staggering, amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars.’ (39)

The tobacco industry decided to fight plain packaging on trade grounds. Arguments focused on intellectual property agreements governed by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the investment protection contained in the North American Free Trade Agreement. Despite being told repeatedly by WIPO that its analysis was flawed, (40) the industry persisted in telling the government and the media that plain packaging would be contrary to intellectual property protections. Following the industry’s misrepresentation of international trade law, a newly appointed Canadian health minister dropped plain packaging. By 1995, plain packaging was no longer on the policy radar in Canada due to the success of the tobacco industry's campaign, coupled with a Canadian Supreme Court ruling against provisions of the Tobacco Products Control Act on advertising and promotion.

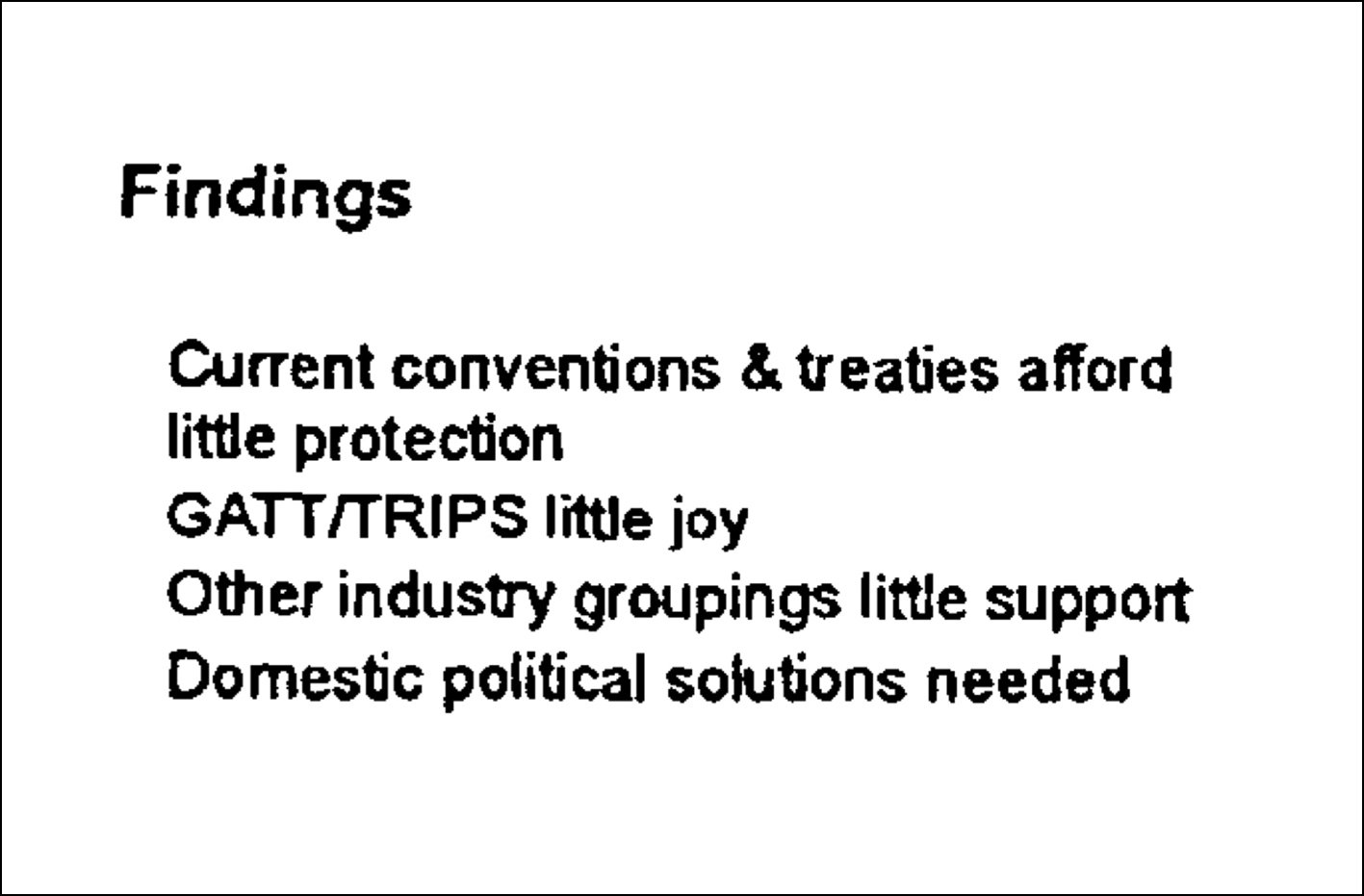

However, as two slides from an internal industry presentation show (Figure 1.2), from at least 1994 the tobacco industry was well aware that international trade treaties and conventions provided it with ‘little protection’, ‘little support’ and ‘little joy’ in defeating plain packaging. Its success in framing plain packaging as being incompatible with these treaties and conventions was a triumph of public relations spin over sophisticated legal understanding of what those treaties would have allowed. The spin had succeeded.

Figure 1.2 Tobacco industry knowledge of legal impediments in opposing plain packaging, 1990s. Source: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hpp34a99

Canadians Rob Cunningham and Ken Kyle published a summary of the case for plain packaging in 1995. (41) Physicians for a Smoke-free Canada have written a detailed account of why Canada did not adopt plain packaging in the 1990s, some 20 years ago. (39) Their report reviews internal tobacco industry documents from the period that have since come as a result of settlements of legal actions in the United States, and traces the tobacco industry campaign to ensure that plain packaging reforms would not succeed.

The new millennium

The failure of New Zealand, Canada and Australia to progress in the 1990s may have temporarily taken the wind out of the sails of advocacy for plain packs. But the concept had taken firm root and was never far from the surface of future possibilities in global tobacco control circles. Two papers on the importance of packaging in the tobacco advertising and promotional mix (42, 43) were published early in the new millennium by Australian researcher Melanie Wakefield’s group, and a case study of tobacco packaging was published in the legal literature in 2004 by Melbourne lawyer Benn McGrady. It explored whether the TRIPS agreement ‘creates a positive right to use a trademark,’ concluding that it did not. (44)

In May 2003, the World Health Assembly, the parliament of the World Health Association, adopted the world’s first global health treaty, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). As of April 2014, 178 nations (as well the European Union) have ratified the treaty and have thereby become ‘Parties’ to it.

Recommendations on plain packaging were included in guidelines on packaging and labelling and on advertising and promotion that were adopted at the 3rd Conference of the Parties, held in Durban, South Africa, in November 2008. (45)

Clause 46 of the guidelines for implementation of article 11, Guidelines on packaging and labelling of tobacco products, states:

Plain packaging

Parties should consider adopting measures to restrict or prohibit the use of logos, colours, brand images or promotional information on packaging other than brand names and product names displayed in a standard colour and font style (plain packaging). This may increase the noticeability and effectiveness of health warnings and messages, prevent the package from detracting attention from them, and address industry package design techniques that may suggest that some products are less harmful than others. (46)

And article 13, Guidelines on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (47) states:

16. The effect of advertising or promotion on packaging can be eliminated by requiring plain packaging: black and white or two other contrasting colours, as prescribed by national authorities; nothing other than a brand name, a product name and/or manufacturer’s name, contact details and the quantity of product in the packaging, without any logos or other features apart from health warnings, tax stamps and other government-mandated information or markings; prescribed font style and size; and standardized shape, size and materials. There should be no advertising or promotion inside or attached to the package or on individual cigarettes or other tobacco products.

17. If plain packaging is not yet mandated, the restriction should cover as many as possible of the design features that make tobacco products more attractive to consumers such as animal or other figures, ‘fun’ phrases, coloured cigarette papers, attractive smells, novelty or seasonal packs.

Recommendation

Packaging and product design are important elements of advertising and promotion. Parties should consider adopting plain packaging requirements to eliminate the effects of advertising or promotion on packaging. Packaging, individual cigarettes or other tobacco products should carry no advertising or promotion, including design features that make products attractive.

In 2005, Cancer Research UK called for the implementation of plain packaging for tobacco products, allowing for only the brand name, the health warning and any other mandatory consumer information to appear on such packs. After studying tobacco company documents, Cancer Research UK concluded plain packaging was ‘the next step in breaking the links between the tobacco industry and its consumers’. (48)

In 2006, Canadian lawyer Eric Le Gresley presented on the legal considerations relevant to plain packaging to a global audience at the 13th World Conference on Tobacco or Health in Washington DC.

Timely review

In August 2007, we were part of a research team working on a three-year National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant examining various options for ‘the future of tobacco control’. (49) Being a very advanced nation in global tobacco control, Australia had fully implemented almost all of the planks of a comprehensive tobacco control policy platform. But smoking prevalence remained at just under one in five adults, and our project sought to focus on some of the less developed or more contentious issues where Australia (and indeed most nations) had not advanced very far. Our group published papers on issues as diverse as regulating the retail environment, (50) genetic testing for susceptibility to smoking, (51) harm reduction (52) and, later, smoker licensing. (53)

Plain packaging was one such issue, and along with Matthew Rimmer, a legal scholar in intellectual property from the Australian National University, we published an online review, (54) later peer-reviewed, (10) on the concept of plain packaging and the evidence and arguments for it.

Researchers are often asked to nominate papers they have produced which they believe have been influential in ‘real world’ settings. This was one such paper. Our review was cited by numerous other researchers who went on to conduct experiments that clearly demonstrated that removing the design elements of packaging sharply reduced product appeal and increased consumer attention to health warnings—see Chapter 2. Our review has been steadily cited by other researchers (Google Scholar shows 111 citations by October 2014, easily the most for any paper yet published on plain packaging) but by far the most important outcome was the timing of its publication and the role it played in shaping the wording of the background and recommendation on plain packaging in the reports of Australia’s National Preventative Health Taskforce (see pp 18).

In May 2008 Scotland’s Smoking Prevention Action Plan (55) committed its government to consider moving towards plain packaging of tobacco products, in conjunction with the British government and other devolved administrations.

The British government followed suit, releasing a Consultation on the future of tobacco control, (56) where it sought reactions from stakeholders and the public on measures that included plain packaging.

In June 2008, the Cancer Council of Western Australia included a question about plain packaging among 21 other tobacco control policy related questions as part of a post-campaign evaluation survey of 408 smokers and non-smokers in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. They asked: ‘To what extent are you in favour or against each of the following measures?’ The statement given was: ‘Selling tobacco products in plain packaging, with only the brand name and health warnings.’

Combining those who were in favour or strongly in favour, 87% of non-smokers, 67% of recent quitters and 45% of smokers were in favour. Among smokers, only 13% were against, with the remainder having no opinion.

In 2011, the Australian public continued to be supportive of the proposal, with 72% of the community supporting the idea in an April 2011 Victorian survey, notwithstanding heavy industry spending on advertising and public relations. (57)

Industry awareness of the approaching storm

From at least 2007, there were signs that the tobacco industry was well aware that the plain packaging issue was about to awaken from its short siesta. Morgan Stanley advised investors:

In our opinion, [after taxation] the other two regulatory environment changes that concern the industry the most are homogenous packaging and below-the-counter sales. Both would significantly restrict the industry’s ability to promote their products. (58)

In September 2008, Adam Spielman, a tobacco analyst at Citigroup, was interviewed by the trade magazine Tobacco Journal International. (59) Spielman was in no doubt as to how important it would be to the industry to stop plain packaging, saying:

If the proposal is carried out, it would reduce the brand equity of cigarettes massively. In my opinion, more than half the brand impact is in the design of the cigarette packet, as opposed to the name of the particular brand. As the industry’s profits depend on some consumers paying a premium of as much as GBP 1.50 (EUR 1.90) for certain brands, anything that weakens this will dramatically reduce profitability. In terms of market shares, you would expect an even more rapid trend of downtrading. Over time, I think the proposal would result in a very severe reduction in the industry’s profit.

Spielman noted with some prescience that plain packaging in the UK was ‘unlikely in the next year or two. On a five- or ten-year view, then I think it is certainly possible.’ He continued:

It is important to remember that every anti-tobacco proposal that has been consulted on by the UK government in the last 10 years has been implemented. In addition, the industry has little hope in appealing to natural justice – no politician has any incentive to support it.

Spielman returned to the issue in 2010, writing:

The most important issue is plain packaging, but there is no advance here. We have always said that, for investors, the no 1 regulatory issue is plain (or generic) packaging: we believe greying out all packs would lead to rapid downtrading. (60)

In a video review, Euromonitor’s tobacco analyst Don Hedley described plain packaging as the mother of all battles that would be faced by the tobacco industry. (61) Two tobacco industry trade magazines, Tobacco Journal International (April 2008) and Tobacco Reporter (November 2012) ran cover stories on plain packaging (see Figures 1.3 and 1.4). The Tobacco Journal International cover warned ‘plain packaging can kill your business’. Actually, this was the whole point, or as Homer Simpson might have put it: ‘D’oh!’ Effective tobacco control unavoidably means reduced sales of tobacco.

Figure 1.3 Cover of trade journal Tobacco Journal International, April 2008

Figure 1.4 Cover of trade journal Tobacco Reporter, November 2012