2

Prevention on a new government’s agenda

It is commonly said that conservative governments have ideological antibodies to preventive health policy, particularly when it comes to anything regulatory. The conventional wisdom is that they are comfortable with funding education and information campaigns, but almost congenitally leery of anything regulatory. However, this characterisation is difficult to sustain when it comes to tobacco control.

From the early 1980s on, various state governments from both sides of politics had run sporadic mass reach campaigns commencing in New South Wales (62) and Western Australia (63) and implemented state and territory-level legislative measures.

But the conservative Coalition government under prime minister John Howard (1996–2007) changed that, introducing at least three very important, sustained initiatives that were anything but signs of a tobacco-friendly party.

As health minister Michael Wooldridge (1996–2001) ensured unprecedented levels of funding for Australia’s first national tobacco control campaign, which commenced in June 1997. Australian government funding was in excess of $7m over two years, with another $2m being spent by state governments. Funding for the national campaign was maintained and increased throughout the Howard era and continued during the Labor government years. Funding for tobacco control programs in Australia increased from 26 cents per adult in 1996 to 55 cents per adult in 1998 and continued at 49 cents per adult from 2001.1

Table 2.1: Recent health ministers and prime ministers, Australia

| Health minister | Prime minister | Party | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tony Abbott | John Howard | Coalition | Oct’03 – Dec‘07 |

| Nicola Roxon | Kevin Rudd | Labor | Dec’07 – Jun’10 |

| Julia Gillard | Jun’10 – Dec’11 | ||

| Tanya Plibersek | Julia Gillard | Dec’11 – Jul’13 | |

| Kevin Rudd | Jul’13 – Sept’13 | ||

| Peter Dutton | Tony Abbott | Coalition | Sept’13 on |

In 1999, after several years of extensive lobbying by health groups using magnificent, detailed reports prepared by Michelle Scollo for the Cancer Council Australia, the Coalition government switched from levying excise and customs duty on cigarettes on a weight basis to a per stick basis. Over the ensuing years, this had a dramatic effect on increasing the retail price of tobacco, while also increasing government revenue. With price being the single most important determinant of consumption, this decision could never be construed as the act of a government or party which was soft on tobacco contro.

Also during this time, the Coalition government followed Canada to be one of the first nations to require graphic health warnings on all tobacco packs (announced in 2003, with regulations adopted in July 2004 and fully implemented from March 2006). This was in the face of strident tobacco industry opposition, and so again an action incompatible with the idea of a government soft on tobacco control. Tony Abbott, later prime minister, was health minister in the Coalition government at that time.

The newly elected Labor government brimmed with enthusiasm about health policy reform. While in Opposition, Kevin Rudd had made a point of emphasising that prevention would be promoted as a major platform of health policy reform (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PwON8dc9zw4).

Rudd’s health minister was lawyer Nicola Roxon, who held a Labor seat in Melbourne’s socially disadvantaged inner west. Roxon had been in parliament since 1998 and Rudd had appointed her as shadow health minister in December 2006. She rapidly developed a reputation within health and medical circles as a highly intelligent, population-focused, big picture politician. ABC-TV’s Australian Story, broadcast a 30 minute portrait of Roxon, including her reflections on her decision to support plain packaging (see http://www.abc.net.au/austory/specials/kickingthehabit/default.htm) and The Age (64) and the Australian Financial Review (65) newspapers ran lengthy portraits.

Her chief of staff from mid-2008 was Dr Angela Pratt, who had done her doctoral research on political debates surrounding Indigenous rights since the 1970s, before spending several years as a researcher specialising in health policy in the Canberra Parliamentary Library. The two formed a formidable team, complemented by staffers Chris Picton (later to be Nicola Roxon’s chief of staff when she became Attorney General), Chris Altis and, later, Angela Koutoulas. These staff were frequently in contact with key individuals in the public health and research communities seeking advice and information, and at different times urging that we might ramp up public discussion of particular aspects of the plain packs proposal.

Angela Pratt recalled the last year of Labor being in Opposition:

It was the year before an election so we wanted to carve out an agenda in health that distinguished us from the Government. . . . I see that year of Opposition as laying the groundwork for all of the things in this area that came after. In particular in that year of Opposition, the Labor Party released a policy paper which was all about putting prevention at the centre of the health debate. In that paper we proposed establishing the Prevention Taskforce as well as doing a few other things to put preventive health on the political agenda and very much on Labor’s health agenda. We also thought of it as a Labor agenda in that the people who are most predominantly affected by preventable illness, including preventable illness caused by tobacco smoke, are people in lower socioeconomic groups. So it was in a sense a new take on an old-fashioned Labor issue, in that it was trying to look after the people who are most disadvantaged by the problem. We saw that as an area that the previous government had neglected.

Within two months of taking government, Rudd convened the Australia 2020 Summit, which saw 1000 Australian leaders in 10 policy areas converge on Canberra in April to engage in a two day ‘future vision’ exercise for the country. Prevention is a word that featured often in the Summit’s report across a number of fields. It was a theme in health policy that would continue throughout the life of the two terms Labor was in power.

In 2008, with 50 or so others from the health sector around Australia, I was invited to a briefing in Canberra by Roxon. Just as Rudd had emphasised in his public speeches, her presentation started with, and dwelt on prevention, not in its usual role as a Cinderella-like policy confection to be sprinkled on the ‘real’ meat and potatoes of health policy like hospital crises and expensive drug subsidies, destined to turn into a neglected pumpkin after any midnight of fiscal restraint, but as a primary consideration. Here was a rare government health minister sending direct and forceful signals that chronic disease prevention was to be taken seriously. To most in the room, Roxon seemed to ‘get it’, to understand the enormous potential for a population-focused approach to public health to achieve major and lasting reductions in mortality and social costs, and wide-scale improvements in health and quality of life. There was palpable excitement in the room that prevention might at last be elevated in health policy reform.

The National Preventative Health Taskforce

In April 2009, the new government lost no time in getting prevention further on to the policy agenda by announcing the establishment of a National Preventative Health Taskforce to develop a framework and recommendations for national action on prevention, focusing in the first instance on three leading areas – obesity, tobacco and alcohol. While a few were mildly irritated by it being called ‘preventative’ instead of the more felicitous ‘preventive’, the establishment of a peak national committee focused entirely on prevention was seen as the opening of a massive door of opportunity.

Mike Daube, who after the now-retired Nigel Gray and David Hill (both former directors of the Cancer Council Victoria) has a longer track record in tobacco control than anyone in Australia, was appointed to the Taskforce as both deputy chair, and as chair of its tobacco committee. The Taskforce was chaired by the widely respected Professor Rob Moodie. The members of the committee advising the taskforce on tobacco control were Viki Briggs (an Indigenous specialist in tobacco control), Dr Christine Connors (a public health doctor from the Northern Territory), Mike Daube, Dr Shaun Larkin (managing director of the health insurance company HCF), Kate Purcell (a highly experienced tobacco control specialist from NSW), Dr Lyn Roberts (CEO of the National Heart Foundation), Denise Sullivan (another highly experienced public health specialist from Western Australia), Professor Melanie Wakefield (arguably the world’s leading researcher on mass reach campaign evaluation in tobacco control) and me. Michelle Scollo, former director of Quit Victoria and to many, the most encyclopaedic and astute person in Australian tobacco control, was appointed as the official writer for the committee.

Daube said that the invitations to sit on the taskforce came directly from the minister’s office:

Absolutely from the minister’s office. I’m sure with some advice from the department and I think particularly having people like Rob [Moodie, the chair], myself and Lyn Roberts on there sent out a very strong signal about what this was to be about – this wasn’t just to be about ‘popular’ prevention. This was to be about coming up with significant recommendations that would make a difference.

My view was that this was a chance of a lifetime, the one chance you get in a lifetime. You’ve got a terrific minister. You’ve got a powerful commission taskforce. You have the best committee you could find. So let’s go for it.

So that’s the message I tried to send out to the committee and the superb secretariat. It was our chance to produce the best report that you could do.

On the first day the tobacco committee met, Daube emphasised to us that his brief had been to convene a committee who should be in no doubt that the government wanted recommendations that would really make a difference. Roxon backed this in an interview, saying:

The only real riding instructions that I can recall having to reiterate quite often was to not give us one all-or-nothing recommendation, but to give us a cascading range of options, but not to be scared about what was included in those options.

We all agreed that we should prepare a report and give recommendations that reflected world’s best practice in tobacco control. In one meeting after a lengthy discussion about where Australia was at the time and where it might go, we took turns to propose sometimes bold, but always evidence-based recommendations. One of these was a substantial increased tobacco tax: two lots of 25%. A 25% increase was introduced within 24 hours of its announcement in April 2010. A 2013 Treasury paper shows that this increase reduced apparent consumption of dutied tobacco products by 11%, nearly twice the 6% that had been predicted. (66) In 2013, a further four annual 12.5% increases were announced and later adopted by the incoming Coalition government. Tobacco taxes were to rise 75% over seven years, on top of the routine rises reflecting changes in the consumer price index. Labor had introduced this, and the Coalition supported it.

Having been closely involved with plain packaging in the months before the committee’s formation through our review of industry documents and tobacco trade literature, (67) when it came to my turn in the committee, I recommended plain packaging, which was unanimously supported.

Three National Preventative Health Taskforce committees each produced an initial paper in December 2008. (68) The tobacco discussion paper included consideration of a wide range of policy initiatives, including plain packaging. Following its release there was an extensive period, until April 2009, for consultation and public submissions. Some 400 submissions were received. (69)

It was noteworthy that notwithstanding a very broad range of issues and options considered in the discussion paper, 43 of the 142 pages of responses from the major tobacco companies active in Australia (BAT, Philip Morris, Imperial Tobacco) were devoted to opposing plain packaging.

Mike Daube’s instincts saw this as extremely telling:

Nearly a third of their responses were on plain packaging. So we thought wow, we’re onto something here. We thought it was going to be good. We didn’t realise it could be that important and I don’t think they could have been more helpful in showing us where the main game was for them.

Early media interest

In April, ABC TV’s program Lateline ran a lengthy item on the possibility that Australia would pick up the plain packaging baton dropped by Canada in the mid-1990s. I had recommended to Lateline’s reporter Peter Lloyd that Canadian researcher Cynthia Callard would be the ideal person to interview.

Callard emphasised that the earlier decisions byCanada and Australia to not pursue plain packing had nothing to do with the strength of the legal case made against the move, but said everything about the success of the tobacco industry’s bluff at the time. (70) She said:

Well, they did that because the whole legal and trade world is a bit behind a black curtain. It is not like the scientific world, where things are published and data are shared. They could come in and tell governments that they had a good case, that they had legal opinions that told them they had a good case, that their trademarks could be protected.

Now we knew that this was unlikely to be the case because the key issue is that you can own a trademark, but it doesn’t give you the right to use it. The only thing that ownership gives you is the right to stop other people from using it, and what we now know as a result of . . . documents that were released as a result of US court actions, is that the tobacco companies had gone to their own lawyers, they had gone to the international agencies like WIPO that govern trademarks, they had surveyed all of the trade agreements they could find and they came to an internal conclusion that they had no case.

But instead of telling governments, well, we were wrong, they paid people to publish books that provided contrary evidence and they just played a good game of chicken.

Sadly, governments blinked and they caved. The Canadian government first and then the Australian government. What we hope now is that with this stronger evidence of exactly the nature of the industry bluffing, that the trade departments will be more supportive of the health ministries to bring in plain packaging.

The taskforce’s final report, delivered to the health minister on 30 June and released in September 2009, contained a recommendation on plain packaging as part of a comprehensive approach: ‘Mandate plain packaging of cigarettes and increase the required size of graphic health warnings to take up at least 90% of the front and 100% of the back of the pack.’ (68)

The report elaborated:

Plain packaging would prohibit brand imagery, colours, corporate logos and trademarks, permitting manufacturers only to print the brand name in a mandated size, font and place, in addition to required health warnings and other legally mandated product information such as toxic constituents, tax paid seals or package contents. A standard cardboard texture would be mandatory, and the size and shape of the package and cellophane wrapper would also be prescribed. (67) A detailed analysis of current marketing practices suggests that plain packaging would also need to encompass pack interiors and the cigarette itself, given the potential for manufacturers to use colours, bandings and markings, and different length and gauges to make cigarettes more ‘interesting’ and appealing. Any use of perfuming, incorporation of audio chips or affixing of ‘onserts’ would also need to be banned.

The legislative announcement

Nearly eight months passed until 29 April 2010, when prime minister Kevin Rudd and health minister Nicola Roxon made the historic announcement that Australia would mandate plain packaging from July 2012, (71) along with a 25% tax increase and a range of further initiatives on tobacco.

Over those eight months, some committee members had written opinion page articles and otherwise commented on the importance of plain packaging, but none of us had received any feedback or indication from the government or the bureaucracy as to which recommendations might be selected for adoption. The proposed legislation was first announced at a press conference held by the two, although late night television broke the news the night before.

Several of us had been called by Roxon’s office about 6pm that night, because a television station had got wind of the imminent announcement. For those closely involved, that phone call was one of those occasions like always remembering where you were when a big news incident occurs. I picked up the phone at home and Angela Pratt, Roxon’s chief of staff said deadpan: ‘I thought you might like to know that we’ll be announcing in the morning that we’ll be introducing plain packaging.’

Daube, as chair, had been briefed a few days earlier.

I was going into a lecture and the mobile rang and I looked at it and thought do I take this call? Oh, who knows? So I took it and there was a voice on the other end saying ‘Nicola Roxon here.’ So I thought well, maybe it was good idea to take the call and she says ‘Mike, you can’t tell anyone but we’re going with the tax and we’re going with plain packaging’. It was so hard to keep the widest grin you’ve ever seen off my face when I walked in to do that lecture.

From that moment, some of us working in population-focused tobacco control in Australia did little else for the next four years. We concentrated our efforts to ensure the announced bill would be passed, then defended it from industry-motivated attempts to discredit its impact.

I asked Pratt about how the plain packaging proposal was received by Rudd. She said:

He was very supportive. I clearly remember being in the meeting when the idea was first put to him when we were discussing how to respond to all of the tobacco recommendations from the prevention taskforce – taxation, packaging, social marketing and other things. The idea was put to him and he said, ‘yes, let’s go for it. I like it, let’s go for it.’ It’s a simple idea at its heart with a compelling logic which the PM [prime minister] got right away.

Rohan Greenland, lobbyist at the Heart Foundation, recalls that his then CEO, Lyn Roberts, and the CEO of the Cancer Council Australia, Ian Olver, had met with Rudd well before the announcement. Plain packaging was not discussed, but the two presented Rudd with data on the widespread support for tobacco control in the community, and assured him that any policy advances on tobacco would be very well received. They sensed he was very receptive.

So what is plain packaging and what aspects of packaging are addressed in the Australian law?

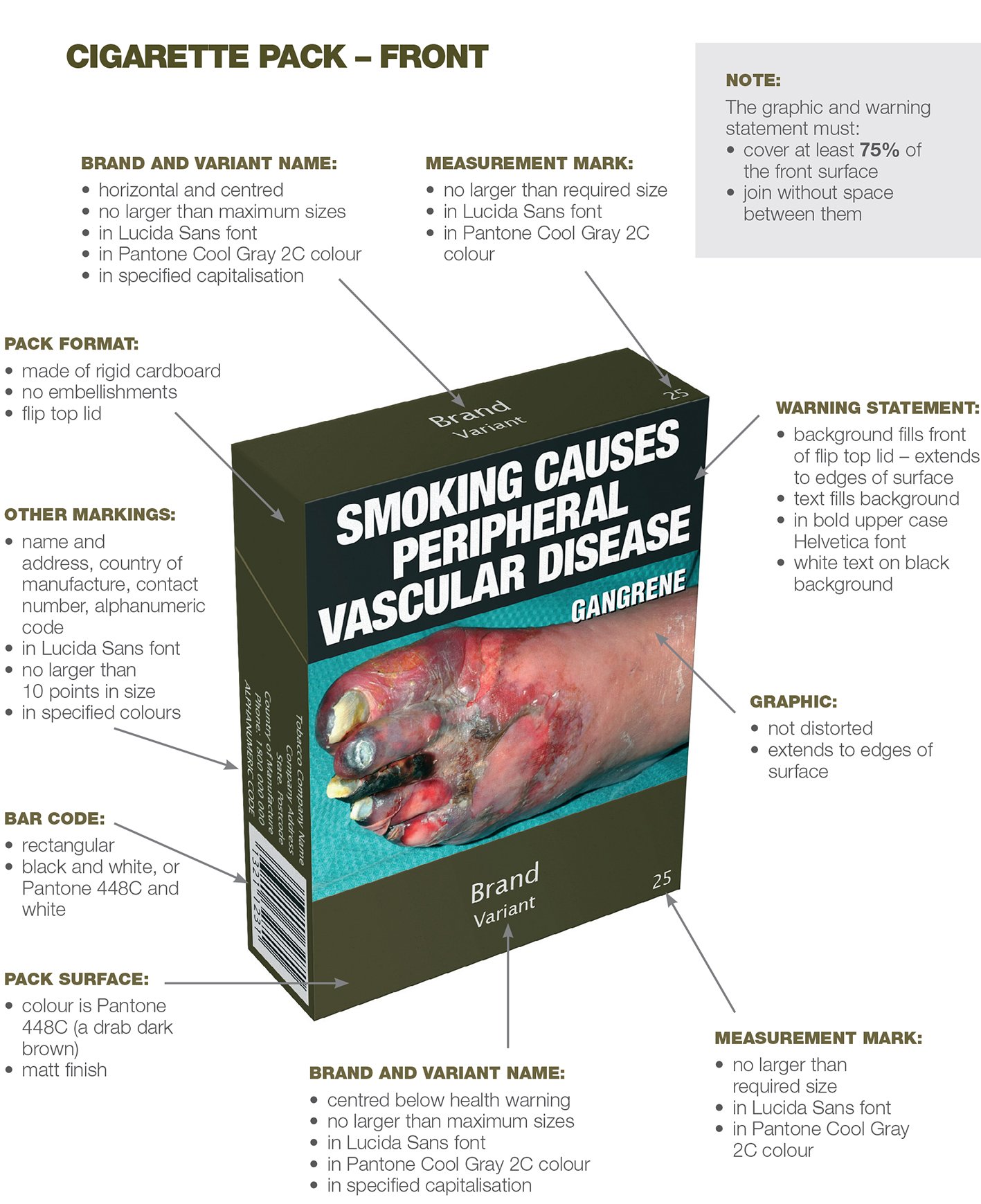

‘Plain’ packaging (sometimes called ‘generic’ or ‘standardised’ packaging) is the term given to Australia’s pioneering national legislation (72) which requires all tobacco products (cigarettes, roll-your-own tobacco, pipe tobacco and cigars) to be sold in prescribed packaging. All packaging for every brand is identical, except for the brand and variant names and the name of each brand’s manufacturer, which still enable each brand to be clearly identified. Here are the essential features of plain cigarette packaging.

- The brand name must appear on the front of the box in a standard size and font.

- The name of any brand variant must also appear immediately below the brand name, also in a standard font.

- All remaining surfaces must be in the colour ‘drab dark brown’.

- 75% of the front of the pack must show one of 14 prescribed graphic (pictorial) health warnings. (73) These 14 warnings are required to be rotated according to a particular pattern across the years, so that each 24 months after the 1 December implementation date, each of the 14 different warnings will have been evenly distributed across all tobacco stock. The same graphic warning must also appear on the back of the pack in smaller size, along with the relevant accompanying textual warning. The size of the combined graphic and text warning on the back of the pack is 90% of the surface area.

- On the top of the pack (both back and front), the matching textual warning must appear.

- The number of cigarettes in the pack must be shown in the bottom right-hand front corner.

- The Quitline phone number must appear on the back of the pack.

- All writing in all the above matters must conform to standard, specified fonts which is the same for all brands.

- The left hand side of the box must show another textual warning.

- The box shape, wrap, and colour of all cigarettes must conform to prescribed standards, the same for all brands.

Figure 2.1 Australia's plain cigarette pack specifications. Source: http://tiny.cc/3xeqox

Figure 2.2 Australia's plain cigarette pack specifications. Source: http://tiny.cc/3xeqox

Australia’s plain packs are therefore far from being just ‘plain’ boxes. They are fully coloured because the boxes must all carry a large graphic health warning, front and rear. In moving to require the health warnings to cover 75% of the front of the pack and 90% of the rear, Australian warnings had set the standard then for the largest in the world, ahead of Uruguay (80% front and back) and Canada (75% front and back).

The goals of plain packaging

The Australian government implemented plain packaging as part of its long-standing policy commitment to end all forms of tobacco advertising and promotion within its control. The path toward ending tobacco advertising had commenced in September 1976 when the then Fraser-led Liberal government enacted legislation, first proposed by the previous Whitlam Labor government, and banned directadvertising on cigarettes on television and radio. Over the next 16 years, successive Labor and Coalition governments both federally and at state level had incrementally enacted further extensions of tobacco advertising bans in different media (cinema, outdoor, point-of-sale), culminating in the Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act of 1992 (74) which ended all tobacco sponsorship in sport and in cultural settings. The WHO’s FCTC, ratified by Australia in December 2003, locked Australia into a list of nations today numbering 178 (75) which are legally obligated to ban all forms of tobacco advertising and promotion.

This background is central to an appreciation of why the Australian government enacted plain packaging legislation: packaging is indisputably a form of product promotion (see Chapter 3). Indeed, the 2014 Chantler Report (76) noted that ‘Japan Tobacco International responded to the decision to introduce tobacco plain packaging in Australia by attempting to sue the Australian government for taking possession of its mobile ‘billboard’.

Plain packaging was also designed to maximise the impact of the graphic health warnings on future and current smokers and to reduce the ability of the pack to mislead consumers.

Australia’s plain packaging Act describes the objectives of the legislation as:

(1) (a) to improve public health by:

(i) discouraging people from taking up smoking, or using tobacco products; and

(ii) encouraging people to give up smoking, and to stop using tobacco products; and

(iii) discouraging people who have given up smoking, or who have stopped using tobacco products, from relapsing; and

(iv) reducing people’s exposure to smoke from tobacco products; and

(b) to give effect to certain obligations that Australia has as a party to the Convention on Tobacco Control.

(2) It is the intention of the Parliament to contribute to achieving the objects in subsection (1) by regulating the retail packaging and appearance of tobacco products in order to:

(a) reduce the appeal of tobacco products to consumers; and

(b) increase the effectiveness of health warnings on the retail packaging of tobacco products; and

(c) reduce the ability of the retail packaging of tobacco products to mislead consumers about the harmful effects of smoking or using tobacco products.

As we will discuss in Chapter 7, the precise wording of these objectives is of utmost importance to questions on evaluation of the impact of the policy.

Prevention as the primary goal

In announcing the government’s intention to introduce plain packaging, Nicola Roxon emphasised from the outset that the leading goal of the legislation was one of prevention of uptake among young people. She said:

And of course we’re targeting people who have not yet started, and that’s the key to this plain packaging announcement – to make sure we make it less attractive for people to experiment with tobacco in the first place. (77)

Paul Grogan from the Cancer Council Australia saw this emphasis as critical to the success in getting multi-party support during the many months ahead of the passing of the legislation:

In years of government relations work, I’ve never met a parliamentarian or advisor of any political persuasion who opposed the idea of protecting young people from tobacco addiction. The fact that the rationale and much of the evidence for plain packaging was about preventing take-up and benefiting children and young adults made it easier to promote to parliamentarians from a range of backgrounds.

The final ‘look’ of plain packaging

The way Australia’s plain packs appear was not the whim of some influential bureaucrat or committee. No one simply declared: ‘let’s have them look this way!’ Instead, almost every facet of their appearance was subject to extensive market research testing. The Department of Health and Ageing established an expert advisory group of Australian and international tobacco control researchers and stakeholders to advise on plain packaging design. They oversaw comprehensive consumer research which would inform the way that plain packaging would actually look. (78)

Six studies were conducted to optimise the plain packaging design and the impact of revised graphic health warnings, which would change at the same time the packs were introduced. The studies are detailed in Table 2.2 below. The results of this work, together with an existing body of experimental evidence on the effects of plain packaging on consumer purchase preferences, led to the final plain packaging design. The full results of the consumer research can be found in a highly detailed report on the health department website (79): http://tiny.cc/2vfqox. Key findings and recommendations of the market research combined with the experimental research include: (78, 79)

Plain packaging colour: A dark olive brown colour emerged as the best candidate for plain packaging. Consumers found cigarette packages in this colour to be less appealing, to contain cigarettes that were perceived to be more harmful to health, of lower quality, and to make it harder to quit smoking. Additionally, this colour was not at all similar to any existing cigarette brand and failed to generate any positive associations for consumers. While a dark brown coloured pack also tested well on these elements, it elicited unintended positive associations such as reminding consumers of chocolate and creating feelings of luxury and warmth.

The official name of the colour chosen for surfaces of the pack not occupied by health warnings is Pantone 448G. Initially people, including Roxon, referred to it as ‘olive green’. The Australian Olive Association was not happy, with its chief executive saying Roxon:

. . . referred to it as ‘disgusting’ olive green, so it hasn’t been very favourable. To associate any food with cigarettes is a thoughtless thing to do, especially one that’s had a very good reputation as being a healthy product. You could have called it ‘drab green’ or ‘khaki green’ or, better still, not used green at all. (80)

It was a fair cop: the colour can much more accurately be described as ‘dark drab brown.’

Pack size and shape

Innovative packaging shape, size and opening can create strong associations which contribute to appeal and brand personality. Cigarette packs are therefore required to be a standard rectangular shape with a standard flip-top opening. The size is also limited, ranging from a minimum based on standard packs of 20 cigarettes to a maximum based on a standard pack of 50 cigarettes.

Font and font size for brand name

Testing revealed that a 14 point font size was the smallest size that maintained legibility of the brand name, when read at a distance of one metre. The Lucida Sans font type was found in testing to be easier to read than Arial. Ensuring brand name legibility addressed a key concern raised by retailers that plain packs would lead to retailer confusion and slowed or incorrect purchases by consumers.

Design of graphic health warnings (size and layout)

Larger front-of-pack graphic health warnings were more noticeable, easier to understand, prompted a stronger reaction to ‘stop and think’ and conveyed the seriousness of health risks. Additionally, larger warnings reduced the overall appeal and perception of the quality of the packaging. A graphic health warning covering 75% of the front of the pack elicited the highest noticeability, message comprehension and dissuasive effect on appeal.

Table 2.2: Summary of studies on pack appearance

| Study | Description | Objectives | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Consumer perceptions of branding appeal, attractiveness and smoking harm | To understand the impact of current brand and packaging design (brand, colour, finish, pack size) on appeal, attractiveness and perceived harm amongst current smokers | Eighteen face-to-face group clinics including a self-completion questionnaire and group discussion among (n=122) at least weekly smokers aged 18–64 years old |

| Study 2 | Consumer perceptions of plain pack colour | To identify a shortlist of potential plain packaging colours | Online survey among (n=409) at least weekly smokers aged 18–65 years old |

| Study 3 | Legibility of brand names on plain packs for retailers | To identify the optimal combination of design elements (font size, font colour) for legibility and ease of identification amongst potential retailers | Face-to-face interviews with (n=10) respondents aged 40 years old and older |

| Study 4 | Consumer perceptions of plain pack colour with brand elements | To shortlist plain packaging colours that minimised brand impact | Online survey among (n=455) at least weekly smokers aged 18–64 years old |

| Study 5 (Face-to-face) | Consumer appraisal of plain packs with new health warnings using prototype packs | To identify the optimal plain packaging designs in combination with the new front-of-pack graphic health warnings | Twenty face-to-face group clinics including a self-completion questionnaire and short group discussion among (n=193) at least weekly smokers aged 16–64 years old |

| Study 5 (Online) | Consumer appraisal of different graphic health warning sizes and layouts on pack | To identify the optimal plain packaging designs in combination with the new front-of-pack graphic health warnings | Online survey among (n=409) at least weekly smokers aged 18–64 years old |

| Study 6 (Online) | Consumer appraisal of different graphic health warning sizes and layouts on pack – Testing 75% GHW layout | To identify the optimal plain packaging designs in combination with the new front-of-pack graphic health warnings | Online survey among (n=205) at least weekly smokers aged 18–64 years old |

Cigarettes, too

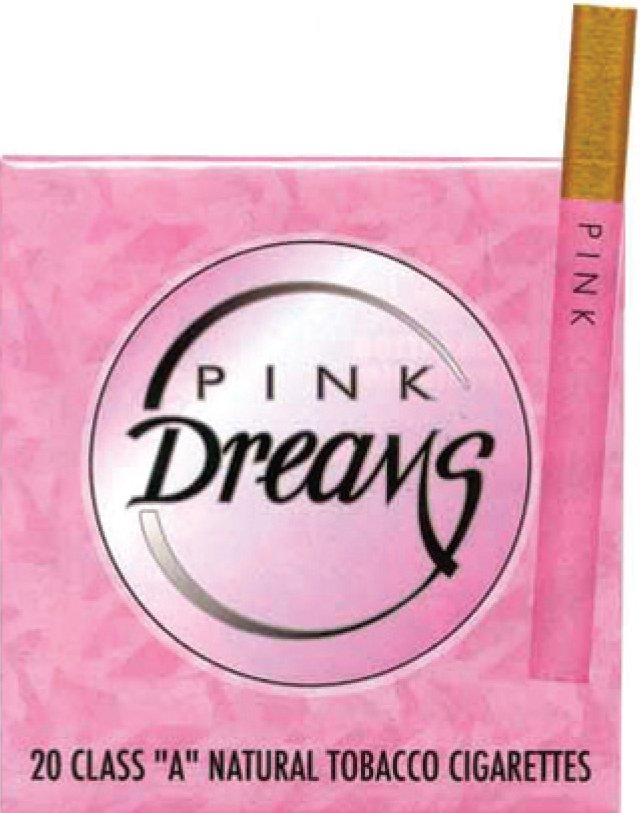

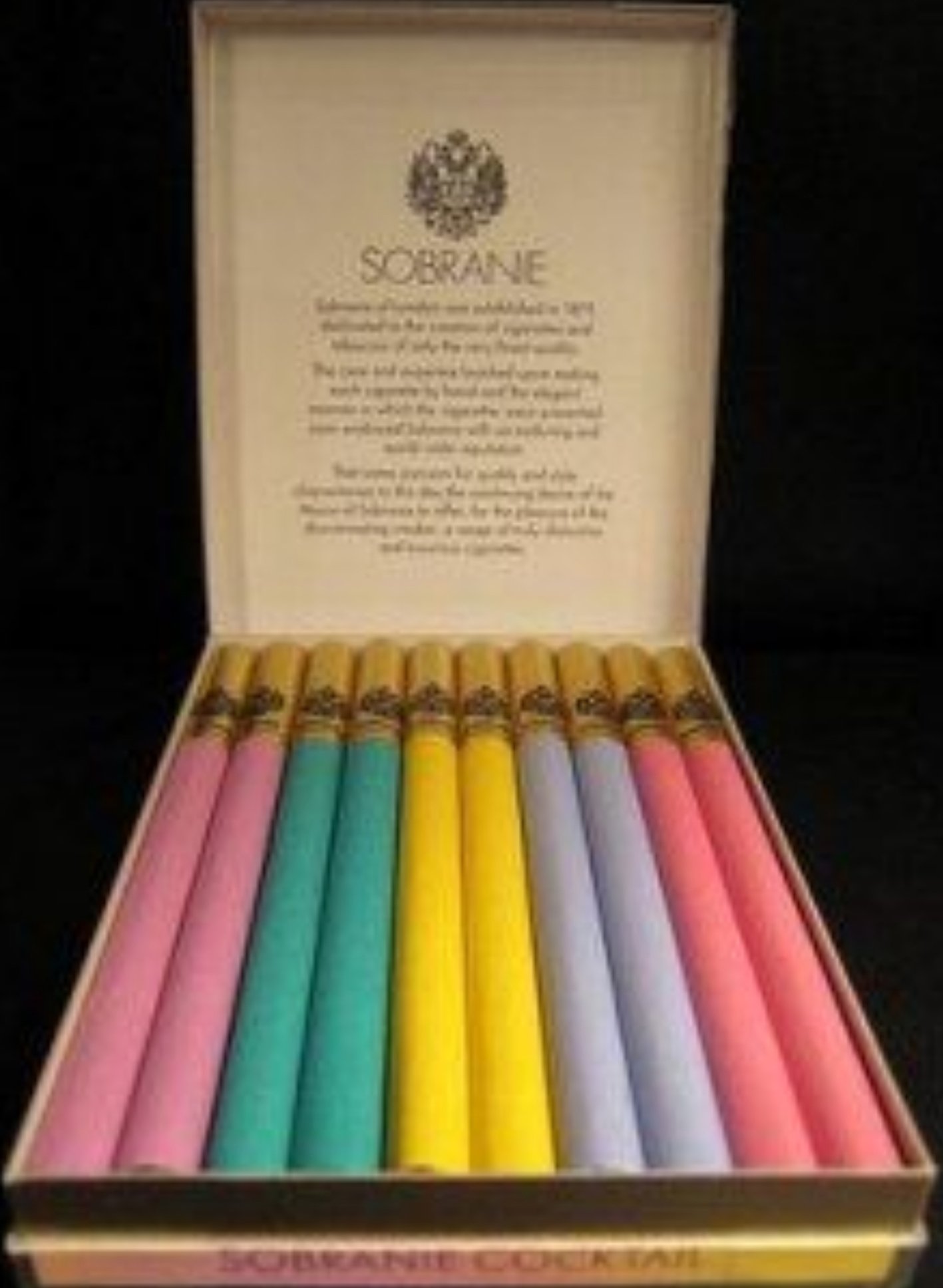

The inclusion of brand names and other design embellishments on the cigarettes themselves is associated with level of appeal and perceived brand personalities. It is less appreciated that Australia’s legislation also standardised the look of cigarettes, not just the packs in which they are sold. In the past, tobacco companies have introduced different colours and bandings on cigarette wrappers (the paper in a cigarette) to make them look more appealing and interesting (See Figures 2.3 and 2.4). Like packs, cigarettes are used in branding and marketing. Accordingly, the regulations accompanying Australia’s new law contain very important provisions which specify that the appearance of cigarettes is also governed by the Act (see Table 2.2). Cigarette stick appearance is limited to either plain white, or plain white with an ‘imitation cork’ filter tip. No branding, other colours or design features are permitted.

Figure 2.3 Pink Dream cigarettes. Source: http://tiny.cc/v0fqox

Figure 2.4 Sobranie cigarettes. Source:

http://cigarettezoom.com/cigarettes-manufacturers/