7

Evaluating the impact of plain packaging

For different reasons, the Australian government, other governments around the world, and the Australian and international tobacco control communities, are intensely interested to know what impact plain packaging might have on the goals of the legislation, as are the tobacco industry and its supporters (see p53).

The Department of Health commissioned a team led by Professor Melanie Wakefield to conduct a suite of research projects evaluating the impact of the legislation on these goals. Wakefield is an international giant in tobacco control research. In 2012 she was voted by a panel of her international peers to receive the American Cancer Society’s Luther L Terry Award for research in tobacco control. This is the field’s peak global award for research excellence. Other winners have included the late Sir Richard Doll and Sir Richard Peto, both from Oxford University and authors of some of the most seminal ‘big epidemiology’ on smoking and health ever published. She has also served as a senior editor on a National Cancer Institute report on mass communication in tobacco control (355), and is an elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of Social Sciences.

The contract for research awarded to Wakefield’s team is a confidential document. Other than the parties to the contract, the research questions and the ways that these are being approached are unknown to others. This confidentiality has no doubt been put in place because the tobacco industry has an intense interest in doing what it can to show the world that what Australia has done has ‘not worked’ and that other governments should therefore not go down the same track. If the industry knew full details of the nature, timing and study populations involved, there are almost certain to be actions that the companies could take to try to disrupt, confound and artificially influence the outcomes of some of these studies.

‘Has it worked?’

The seemingly most obvious and basic question that is most frequently asked about what Australia has done with plain packaging is ‘has it worked?’ In the 20 months since the new packs began appearing in shops, we and our colleagues have both been asked this many question many times by Australian and international journalists, colleagues working in other fields, friends and students from all around the world doing assignments.

As will be discussed at length in this chapter, this apparently very obvious question invariably rests on a number of assumptions by the questioner about the objectives of plain packaging. These assumptions are about the timing, magnitude and causal attribution of changes in smoking (to uptake, cessation and total cigarettes smoked). What might seem like a very simple question rapidly emerges as being very complex as the often naïve assumptions beneath it are interrogated.

This complexity was fully appreciated by those responsible for drafting the plain packaging legislation and is reflected in the objectives contained in the legislation (see p53). The goal of Australia’s comprehensive approach to tobacco control is to reduce tobacco use, exposure to tobacco smoke and diseases caused by it. When public health advocates and researchers think about a policy like plain packaging ‘working’, they do not think about a cartoon-like caricature of a smoker robotically responding in immediate Pavlovian hot-wired simplicity to a single policy. They think about how one ingredient like a price rise, a new health warning or campaign works over time in conjunction with all the others. Everyone working in tobacco control knows that the various elements of tobacco control policy and programs do not work in isolation from each other but in concert, with relationships that, to be best understood, need to be researched longitudinally over many years.

Proximal and distal factors influencing smoking

The decisions individuals make to not take up smoking or to stop smoking are sometimes made suddenly and sometimes unpredictably in response to specific stimuli named by those involved. These stimuli can include the onset of symptoms like coughing up blood or a coronary incident. Other common precipitating reasons for quitting include pregnancy, highly memorable and personally relevant pre-operative ‘doctor’s orders’, a plea to quit from a loved one like a spouse or child, a sharp tax or price rise, perhaps taking the cost of a pack through a psychological barrier like $20 a pack, or the impact of a powerful new piece of information via an anti-smoking campaign. These sorts of immediate, sometimes quick-acting influences are called proximal factors, and have often been reported in research literature on smoking.

But the far more common natural history of someone not ever taking up smoking or finally deciding to quit reflects the confluence of many years of influences, both specific and general. Children and adolescents might grow up in nuclear and extended family environments where they never or rarely see a family member smoking. They may also have few friends who smoke. They may be exposed in classroom settings as well as via mass media to anti-smoking information. They may often see smokers huddling outside of buildings and think that being a smoker doesn’t look much fun. If they are aged 22 or under in Australia today, they would have grown up never having seen tobacco advertising or a tobacco-sponsored sporting event, because these were all finally banned in 1992. They may have read that a pack a day smoker could spend more than $7000 a year on cigarettes, and count their blessings that they do not have to accommodate such an outlay. The chances are that they would be exposed to all or many of these influences.

Similarly, smokers who quit most commonly nominate a general ‘concern about health’ as the outstanding reason why they quit. This concern may have been nascent for many years, but became steadily amplified by emotions like regret, personal resentment at being addicted, concern about the expense of smoking and about not enjoying being a smoker in a society where smoking is exiled from every indoor public space, and from many private spaces like homes and cars. One day, often after a history of several failed attempts, many such smokers finally decide to quit. Every year, many thousands succeed in permanently stopping. Any attribution of this decision to just one of the preceding factors, or an account of why they quit which was blind to the complexity of the distal, life-course factors that have acted to finally get a smoker to a point where they decide to quit, would explain little.

Plain packaging might well function as a ‘slow burn’, distal negative factor against smoking, than as a precipitating proximal factor akin to those described above. Plain packaging removes a major positive influence on smoking: the ability of smokers to handle and display a richly semiotic connotative badge designed to reinforce a chosen sense of self or to be an accoutrement of personal style.

Accordingly, in setting the objectives of plain packaging, those who drafted the Australian legislation would have almost certainly reflected on the likely role that the removal of this final form of tobacco promotion would have in the overall mix of factors that together act negatively on smoking.

For this reason, the Australian government appropriately did not forecast any precise effect of plain packaging, but instead emphasised the longer-term focus (especially in relation to preventing uptake of smoking by children) and, through its National Tobacco Control Plan (356), its commitment to a comprehensive, long-term approach to reducing tobacco use.

The objectives in the legislation included ‘discouraging’ people from taking up smoking, ‘encouraging’ cessation, ‘discouraging’ relapse, reducing the appeal of tobacco and the ability of packaging to mislead, and increasing the effectiveness of health warnings. Each of these objectives embody what the Chantler report (76) calls ‘intermediate’ effects that lie in three broad areas: reductions in the appeal of smoking, increases in the salience of pack health warnings and increases in perceptions of harm from smoking.

Studies monitoring the possible role of plain packaging in achieving these intermediate goals could for example consider changes in:

- negative attitudes about smoking

- negative views about the desirability of smoking

- knowledge about harms of smoking

- intentions to not smoke

- increased effectiveness of health warnings.

For its part, the tobacco industry decided that acknowledging the subtleties and complexities in all this would not be in its interests. Instead, it opted to commission studies and frame data and expectations as if plain packaging was a classic proximal variable. The test of the effectiveness of the policy was put succinctly by one of the industry’s leading acolytes, the English libertarian Chris Snowdon, who wrote that nothing less than ‘a sharp decline in smoking prevalence, particularly underage smoking prevalence’ (357) was the test of whether plain packs worked. He did not define the magnitude of ‘sharp’, but the average annual fall in adult smoking prevalence over the past 30 years in Australia has been just 0.5%. (358)

Critics of plain packaging played the game of demanding ‘hard’ evidence that would unambiguously show the precise impact of the legislation, uncluttered by any other variable. The logical consequence of this line of ‘hard’ argument was that nothing less than a randomised controlled trial of the introduction of plain packaging which showed that it reduced smoking prevalence in children would be satisfactory.

The Chantler report was brutally dismissive of such a demand:

I do not consider it to be possible or ethical to undertake such a trial. To do so would require studies to be carried out within a suitably large and isolated population free of known confounding factors that influence smoking and prevalence. Such studies would expose a randomised group of children to nicotine exposure and possible addiction. Australia does not constitute that trial because a number of things have happened together, including tax rises. Disentangling and evaluating these will take years, not months.

I have been asked whether the evidence shows that it is likely that there would be a public health impact. This is clearly not an issue which is capable of scientific proof in the manner one might apply, for example, to the efficacy of a new drug. There have been no double blind randomised controlled trials of standardised packaging and none could conceivably be undertaken. The most direct experiment to test the efficacy of standardised packaging might be to compare the uptake of smoking in non-smoking children with cigarettes in branded packaging and to see which group smoked more. But given the highly addictive and harmful nature of smoking, such an experiment could, rightly, never receive ethical approval. In any case such an experiment would need to be conducted over a long period and within a large population in which other variables were held constant. Indeed in Australia it will be difficult in due course to separate the effect of plain packaging from other factors such as changes in pack sizes introduced by the manufacturers, and price and tax increases.

Chantler concluded that the best evidence that could be in fact be obtained would be in the form of the ‘intermediate outcomes’.

Having reviewed the findings of the Stirling Review and subsequent Research Update, and the detailed critiques made of them, I believe the evidence base for the proposed ‘intermediate’ outcomes is methodologically sound and, allowing for the fact that overall effect size cannot be calculated from it, is compelling about the likely direction of that effect. Taken together the studies and reviews based on them put forward evidence with a high degree of consistency across more than 50 studies of differing designs, undertaken in a range of countries. (76)

Industry claims about impact

Various tobacco industry statements and reports about the impact of the legislation began appearing from as little as five months after implementation and continue as we go to press. Almost uniformly, the spin put on these reports by the tobacco claimed that plain packaging had already been shown to be a failure.

Devastating to sales or zero impact?

In forecasting the impact of plain packs, the tobacco industry and its supporters seemed to be intent on imitating the mythical creature from Hugh Lofting’s Dr Dolittle series, the pushmi-pullyu. This was the two-headed beast with two minds of its own. The beast would try to move in opposite directions at the same time. For example, the Alliance of Australian Retailers ran an industry-funded multimedia campaign asserting that plain packs ‘would not work’ (see pp97) – meaning they wouldn’t reduce sales.

This was a refrain megaphoned at every opportunity. But it created a small problem for another central plank of the industry’s case, where the other end of the pushmi-pullyu, the BAT-funded IPA, was warning that plain packaging would work like nothing in the entire history of tobacco control: it would reduce sales by up to an unprecedented 30% in the first year and by further 30% tranches in every year after that (see pp145). A back-of-an-envelope calculation shows that starting at annual consumption of 24,032 million cigarettes and cigarette equivalents1 in 2010–11, and reducing this by 30% every year, by 2020, consumption would have fallen to just 969.4 million sticks – just 4% of the starting point. The IPA confidently predicted that the High Court would order the government to compensate the companies concerned for all of this massive loss.

But after being humiliated in the High Court, the industry quickly moved the pushmi-pullyu beast out of sight into a back paddock and put all its efforts into three main arguments: (1) the packs were not causing any reduction in sales; but (2) they were driving smokers down-market to buy cheaper brands with lower profit margins for manufacturers and retailers, and (3) the illicit market was booming, all because of plain packaging.

Imperial Tobacco: market down by 2% to 3%

In April 2013, just five months after plain packaging implementation, Imperial Tobacco’s global CEO, Alison Cooper, appeared on a video for the company’s shareholders. (359) Cooper said: ‘I should also mention Australia – we’ve had the first six months of the plain pack environment in Australia. We’ve seen the market decline roughly 2% to 3%, so maybe not as bad as we might have anticipated.’ [our emphasis].

Coming from a tobacco company with access to its own sales data, and almost certainly high-level intelligence on that of its competitors, this was an important declaration about expected and actual changes to sales in the first months of the implementation. To get perspective on this statement, we need to look at changes in consumption in Australia in the years before plain packs were introduced. In April 2010, on the same day that the government announced plain packaging would be introduced, it announced an immediate and unprecedented 25% increase in tobacco tax. A Treasury paper reported that while a fall in consumption of 6% had been predicted, the impact was nearly double that at 11%. (66) In the years between 2003 and 2009, the annual change in the number of cigarette equivalents dutied ranged from an increase of 2.3% to a fall of 2.5%. The average change was a decline of 1.1% per annum prior to the April 2010 tax increase. So a half year fall of 2–3% would appear to be at least double the rate of the average annual fall.

The Imperial CEO’s carefully chosen rough ‘2–3%’ fall, rather than precise estimate, might suggest that the fall was more toward the 3% end. If the fall had been more toward 2%, this would have been clearly worth stressing given the company’s strenuous efforts to attack plain packs.

Another early example of the ‘it’s failing’ performance came from Jeff Rogut, chief executive of the Australasian Association of Convenience Stores. Rogut spelled out the unfolding disaster to an English audience at a Philip Morris sponsored meeting in London in April 2012. He’d spoken to ‘a number of retailers’ to get ‘some open and honest feedback on what’s happened in the last five months’. Using this robust methodology, he told the audience that smokers were trading down:

People are saying ‘why should I pay $17 when I can pay $12 or $13? Nobody’s going to judge me in terms of what brand I’m smoking – I might as well smoke the cheaper brand.

He explained that by paying cheaper prices ‘actual unit sales are up. People are buying more cigarettes more frequently.’ But then a few sentences later he asked: ‘Has it done anything to smoking rates or the tobacco sales? Nothing at all. Our sales have been steady. After five months there has been no noticeable reduction in people smoking or buying cigarettes. ’ (360) [our emphasis]

So here we can presumably just take our pick: ‘actual unit sales are up’ or ‘there has been no noticeable reduction in people smoking or buying cigarettes. . . nothing at all’. All with the benefit of the authoritative Mr Rogut having supplied no data on national smoking prevalence beyond his recollections of speaking to ‘a number’ of retailers and reporting this at a Philip Morris organised meeting in London.

London Economics report

In November 2013 a press release on ‘one of the first comprehensive surveys of smoking prevalence since the introduction of plain packaging in Australia one year ago’ was issued by a private UK consultancy, London Economics, sponsored by Philip Morris. It stated:

Over the time frame of the analysis, the data does not demonstrate that there has been a change in smoking prevalence following the introduction of plain packaging despite an increase in the noticeability of the new health warnings.

The message was that the legislation was not working.

Within hours, Cancer Council Victoria produced a critique of the report, that would have seen any undergraduate researcher who had authored the nonsense it contained humiliated by the basic methodological flaw in the study and its serious lack of statistical power, to make the claims its authors made for it. The demolition is so complete, we publish it in full.

This Philip Morris-funded survey has been conducted on the mistaken assumption that adult smoking prevalence ought to have markedly declined immediately following the introduction of plain packaging and refreshed larger graphic health warnings in Australia. No tobacco control intervention in history has ever achieved that. Unsurprisingly, this was therefore not the expectation of government or the public health community.

Rather, the more proximal aims of the plain packaging legislation were to reduce appeal of packaging, especially for young people; increase the salience of health warnings; and reduce the ability of packaging to mislead consumers about the harmful effects of tobacco use. The legislation was introduced as one of a number of tobacco control strategies, including tobacco tax increases and mass media campaigns, to contribute to reducing overall smoking prevalence.

The most important methodological difference between this attempt to assess smoking prevalence and the approach used in the three-yearly government-funded survey called the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS), is that the Philip Morris study failed to use a probability-based sampling approach. It is a basic tenet of population survey research that the most representative samples are those where every population member has an equal probability of being included in the survey.

Because the Philip Morris survey used an online panel to obtain responses from Australians and it used those responses to estimate prevalence, only Australians who are members of online market research panels could be included. While panel members comprise people of a wide range of demographic characteristics, these people opt-in to become members of an ongoing online panel for the purpose of taking part in many different surveys or studies and they earn rewards each time they participate. In this way, they are going to be different from a representative cross-section of the Australian population. The Philip Morris survey would likely have mixed together several online panels to achieve these numbers. The survey used quota-sampling (that is, it required its sample to have a particular mix of age, gender and regional characteristics), presumably to try to compensate for its non-probability-based sampling approach. However, quota-based sampling cannot ensure the survey is representative of the wider Australians population who are not members of online survey panels.

By comparison, the NDSHS uses a household sampling approach, where all residential Australian private households are eligible for inclusion in the sample. The non-representative nature of internet panels in Australia is the most likely reason that the London Economics Philip Morris report estimates daily smoking prevalence (around 20% in each survey attempt) to be much higher than the far more representative NDSHS, when it recorded 17.4% daily smoking among 18+ year olds back in 2010.

The three attributes the report authors highlight to suggest it is a high quality survey (under ‘quality assurance’) are in fact ordinary, basic elements of survey practice. However, this section is silent on the survey response rate achieved, which is another critical survey attribute – that is, out of all people approached to do the survey, what proportion responded. Since the survey did not use a probability-based sampling frame, it is unlikely to be a reliable reflection of Australian smoking prevalence (and its overestimated smoking prevalence figures show that in each of the surveys), but since it did not report survey response rates, readers cannot know if it is even a true reflection of Australian online panel members.

The relatively large numbers used in the survey and the use of questions consistent with those used in the NDSHS, cannot make up for the failure to use a probability-based sampling frame from which to select a sample in the first place, and the lack of information on survey response rate.

As noted at the outset, the aim of the legislation that introduced plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings was to weaken the appeal of smoking and strengthen knowledge of health effects: it did not involve any immediate call to action. Its effect is likely to be a longer-term one, enhancing the effects of campaigns and tax increases in discouraging youth smoking uptake and prompting quit attempts and thereby contributing to the decline in the prevalence of smoking over the longer term. But even if the aim had been to prompt an immediate drop in prevalence, the Philip Morris study was not sufficiently powered to find one.

While survey samples of around the 5000 mark are adequate to detect large changes in attitudes and behaviour, this number is nowhere near large enough to detect the very small changes in prevalence in any country that might be expected year to year. The NDSHS with a sample of 24,000 Australians is large enough to pick up declines in prevalence of smoking of 1% to 2%, the sorts of drops that might be feasible over a three-year period. To pick up a 0.5% decline in prevalence (a decline of the sort of magnitude that might be expected over a 12-month period) would require a sample size of over 90,000 respondents. The follow-up surveys of just over 5000 respondents used in the London Economics reports would be able to detect any decline in prevalence over a one-year period only if that decline were larger than 2% points – a drop in relative terms that would be unprecedented in tobacco control history.

Table 7.1: Sample sizes required to detect various declines in prevalence

| At a starting daily prevalence of . . . | . . . to detect, at alpha = 0.05 and power of 0.80, (two-sided test) a decline of . . . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0% | 1.5% | 1.0% | 0.5% | |

| 20% | 6,039 | 10,844 | 24,641 | 99,519 |

| 17.5% | 5,406 | 9,728 | 22,149 | 89,630 |

Source: http://www.stat.ubc.ca/~rollin/stats/ssize/b2.html

Governments are understandably eager for information about the impact of plain packaging. Well-designed studies on changes in attitudes and beliefs will be highly instructive. But given the likely mode of effect of this policy, it is likely to be many years before an impact on the decline in prevalence can be accurately assessed.

Never say die

On the day after the Chantler report (76) was released, BATA issued a press release (361) declaring:

Since plain packaging was introduced, industry volumes had actually grown for the first time in over a decade while the decline in the number of people smoking had dropped by over half.

From 2008 to 2012 smoking incidence, or the number of people smoking, was declining at an average rate of -3.3% a year. Since plain packaging was introduced, that decline rate slowed to -1.4%,’ Mr McIntyre said. ‘Over the five years in the lead-up to the introduction of plain packaging, total tobacco industry volumes were declining at an average rate of -4.1%.

Subsequently, since plain packs were introduced on 1 December 2012, industry volumes have actually grown for the first time in a long time to +0.3%. ‘Further, the number of cigarettes smoked on a daily basis declined at a rate of -1.9% in the five years leading up to plain packaging, while it slowed to -1.4% after green packs hit shelves.

The long-term decline of people giving up smoking at a fairly consistent rate and also smoking less has changed for the worse.

So here was BATA, a company normally breathless with excitement in being able to report growth in market volume to its investors, reporting the trifecta of a bounce-back in growth (the first ‘in a long time’) a slowing in the decline in the number of cigarettes being smoked each day, and an apparent halt in smoking cessation and attributing this growth to the introduction of plain packs. Recipients of this press release were supposed to understand that BATA was really unhappy about all this renewed growth and that they would have preferred the pre-plain packs days when each of these basic indicators were heading south for the company.

BATA’s press release was issued in spite of the Chantler report saying of their data on the alleged 0.3% growth in market volume:

This data is [sic] likely to be affected by transitional impacts. For example, retailers returned a significant quantity of tobacco stock in branded packaging during the first half of 2013 which was subsequently destroyed rather than smoked. Stockpiling in anticipation of pre-announced tax increases will also have affected the data.

Data on volumes at the final point of sale, which is less affected by these transitional impacts, shows consumption has fallen since the introduction of plain packaging. Cigarette sales in grocery stores fell by around 0.9% in 2013 according to the Retail World trade magazine. It is noteworthy that the population over 15 years of age increased by 1.5% in 2013.

Chantler’s comments about old non-compliant stock being dumped or sent back to the manufacturers were supported by remarks made by Jeff Rogut in comments made to the same Philip Morris organised meeting in London in 2013 mentioned earlier. He told the meeting:

There was an enormous amount of work for retailers to clear out the old stock. Some stock was taken back and some retailers chose to dump the stock. So the small retailers were really acting as the implementers of government policy.

Implementers of government policy? Well, yes. That would be in the same way that dairy companies are ‘implementers’ of government policy on pasteurisation, and petrol companies on lead-free petrol policy. What a burdensome thing it is to be a retailer! Plain packaging was the fourth time since 1973 that Australian retailers had been required to change all tobacco stock over to packs with newly legislated health warnings. Any retailer who was unaware that it would be illegal to sell the old branded packs after 1 December 2012 would have had to have been in a deep coma. They had 12 months’ high profile notice about the impending changeover. Rogut failed to note whether the supplying manufacturers were still off-loading their old stock to retailers too close to the date after which it would be illegal to sell it. And if retailers were silly enough to overstock the soon-to-be illegal fully branded packs, those in the meeting were presumably supposed to all agree that this was yet another catastrophe to be heaped on the towering plain packaging debacle.

Impact of plain packaging on children

Most analysts of the likely impact of plain packaging believe that its main impact will be on children over the next generations – the primary intent of the legislation as outlined from the outset by Nicola Roxon. Just as no Australian child aged born since 1992 has ever seen a local tobacco advertisement or tobacco-sponsored sporting event, no child growing up after December 2012 will ever see carcinogenic tobacco products packaged in carefully market researched attractive boxes. Smoking rates among youth today are the lowest ever recorded. Plain packs are expected to preserve and continue that downward momentum, starving the industry of new generations of new smokers as older smokers quit and die early.

Australia has been very successful in reducing smoking by children and young people aged under 18 years. Data from 2011 show that only 3.6% of 12–17 year olds are ‘committed smokers’ (ie. smoked on three or more days in past week), the lowest on record. (362) Moreover, total underage tobacco consumption by secondary school students was only just over 100 million cigarettes in 2011 (based on average reported weekly consumption of 17.16 cigarettes per week for the 44,683 children 12–15 years and 22.66 cigarettes per week for the 57,328 students aged 16 and 17 who were estimated to be smoking at least weekly). (362) This represents less than 0.5% of the total 22 billion cigarettes (manufactured cigarettes or equivalent roll-your-own cigarettes or cigars) that were subject to excise and customs duty in the same year. (363)

This context is critical for any discussion about what plain packaging might do to total demand for cigarettes among children, the main target of the policy, both now and into the future. Even if plain packaging was to cause an immediate fall in tobacco use of 5% (which would catapult the policy into the vanguard of proximally impactful strategies), the problems in being able to detect this effect using available or any conceivable data set are insurmountable.

It would not be possible to use customs and excise clearance data on apparent tobacco consumption to make claims about what proportion of any changes were attributable to changes in consumption by young smokers because those survey-based data are of course not matched in any way to customs and excise data on who is consuming the cigarettes released into the market by local manufacturers or importers. Instead estimates of the amount being consumed by different population segments are estimated by applying survey data extrapolations to total apparent consumption (customs and excise) data.

If we hypothesised that plain packs might cause what would be a remarkable and possibly unprecedented additional 5% (relative) decline in the proportion of under 18 year olds being committed smokers (smoking on three or more times per week) in a year after the introduction of plain packaging, we would need to conduct a before and after study capable of detecting a 5% shift from the current 3.6% down to 3.42%.

To detect with a significance level of 5% and a power of 80%, we would need to survey 164,087 children (364) in each of two separate surveys, before and after the introduction of plain packaging to detect such a difference. Such an undertaking is completely out of the ballpark of any study of smoking prevalence ever conducted in Australia. The national Australian Secondary Schools Alcohol and Drugs study of children’s drug use (including smoking) samples just under 25,000 children nationally. (362)

University of Zurich report

In March 2014, the industry made yet another attempt to convince the world that plain packs had been a flop. This time, they focused on the impact on children via a Philip Morris-commissioned report from two researchers at the University of Zurich. (365). This report used 13 years of data on 14–17 year olds self-reported smoking included in monthly door-to-door cross-sectional surveys.

It is interesting to note here that Philip Morris has purchased data on youth smoking despite frequent public statements about its disinterest in the youth market. The report’s authors concluded that there was no evidence of any impact on youth smoking prevalence for the 12 months from December 2012.

However, despite enthusing that their data were ‘reliable cigarette market data’, they also noted about the youth data that:

Since the monthly sample sizes are rather small, ranging mostly between 200 and 350, and since the minors included in the sample change from month to month, it is expected that the monthly observed prevalence is rather unstable over time. This is indeed the case.

Again, Cancer Council Victoria quickly threw withering sunlight on this tobacco industry-commissioned report’s many problems (366), commencing by noting:

The report is seriously flawed conceptually. It is based on the straw man principle that plain packaging could be expected to immediately lead to a detectable reduction in adolescent smoking prevalence. No other tobacco control intervention has achieved that and neither is this the expectation of governments or credible researchers.

Many other problems were identified in the report.

The survey of adolescents was completed at home, when many parents would be present. This could lead to under-reporting of smoking.

and

The small monthly sample size prohibits any credible analysis of change over a short period of time. The authors describe the sample as being between 200 to 350 adolescents per month, (although they neglect to point out the sample size in the last several years has been reduced to closer to 200 per month). The authors’ entire analysis is based on the fact that they have been able to fit a trend line to the measure of smoking over the 13-year period examined. This is not a test of plain packaging but a simple description of how much on average smoking prevalence has declined over the 13-year period. It would be truly concerning if any ongoing survey in Australia could not yield this basic descriptive parameter, since there has been such a large gradual decline smoking over this 13 year period due to the aforementioned ongoing tobacco control policies and program efforts. (366)

The day of reckoning

17 July 2014 is unlikely to be a date that the global tobacco industry will ever forget. At 1am Canberra time an embargo was lifted on a set of numbers that drove a stake deep into the heart of Big Tobacco’s continuing best efforts to deny that plain tobacco packaging had made any impact on Australians’ smoking.

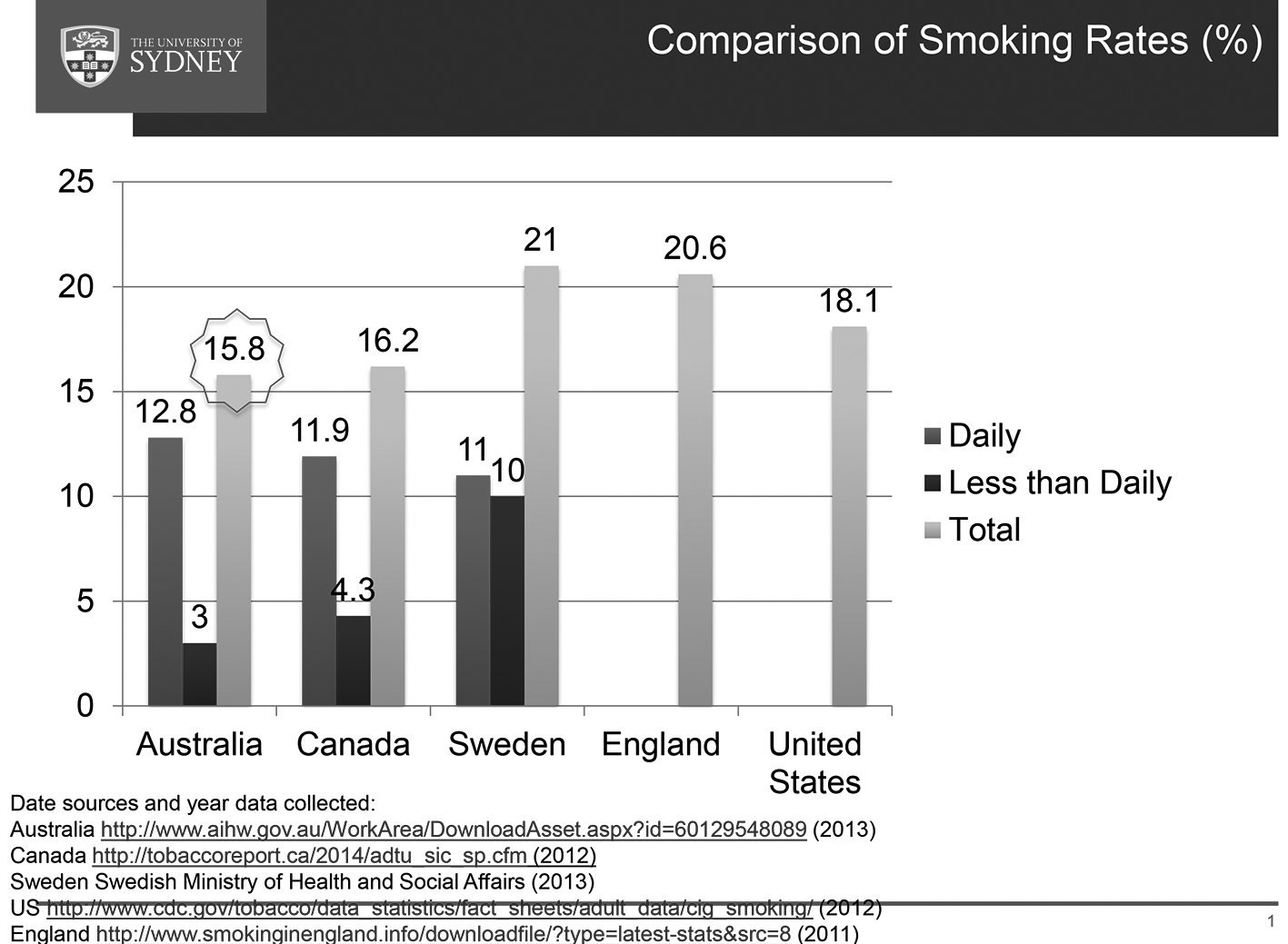

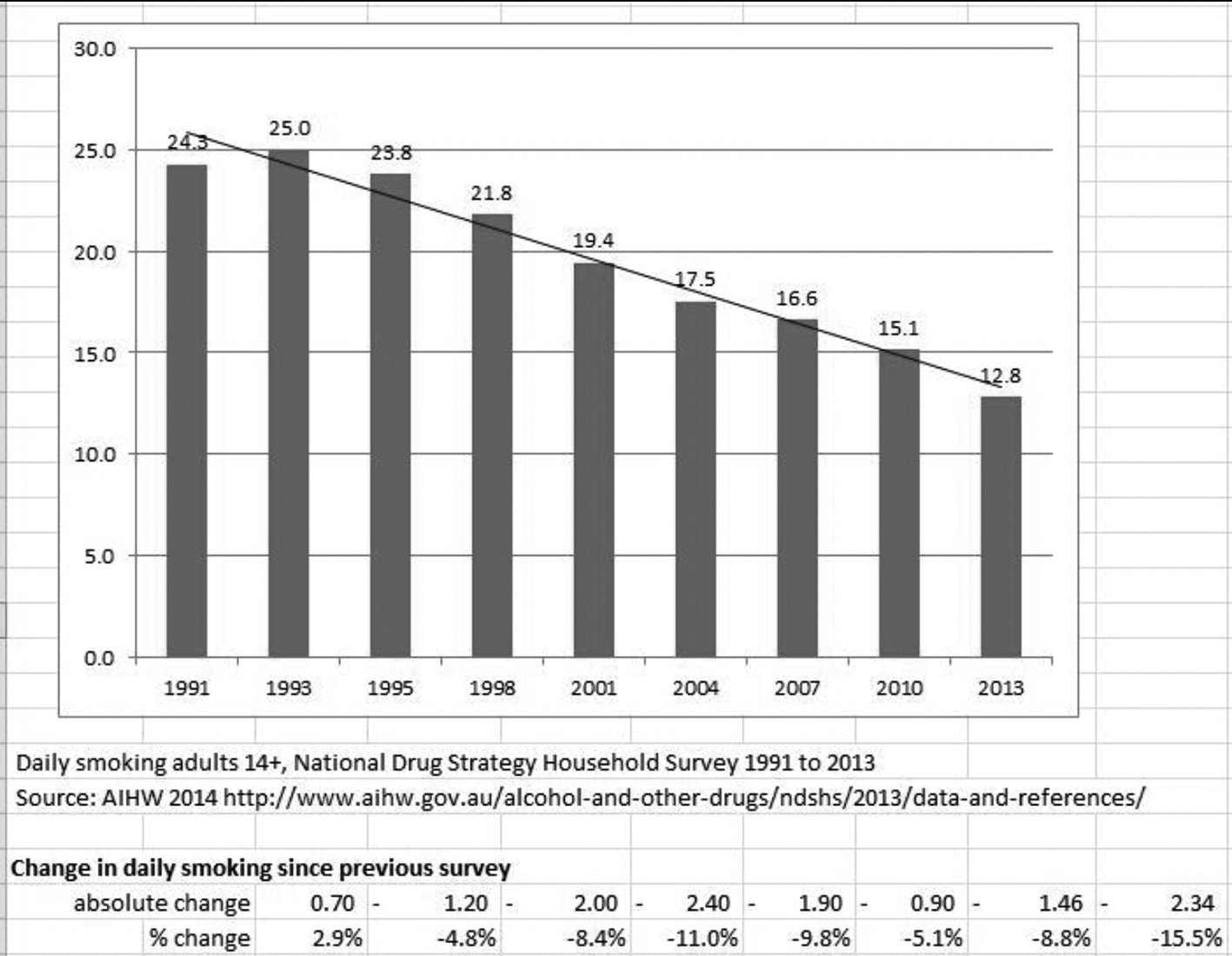

The AIHW released the results of its latest national survey of drug, alcohol and tobacco use, involving 23,855 people. (194) These surveys have been conducted every three years since 1991, when 24.3% of Australians aged 14 and over smoked on a daily basis. In November 2013, this figure had almost halved to 12.8%. With another 3% smoking less than daily, Australia’s 15.8% was now the lowest daily rate in the world, with Canada in second place with 16.2%. (367) Sweden is in world’s first place on daily smoking (11%) but with another 10% smoking less than daily, its 21% total smoking rate (368) places it well behind Australia, Canada, the USA and England (see Figure 7.1). Moreover, the percentage fall in Australia between 2010 and 2013 was a record 15.2%. The average percentage decline across the nine triennial surveys since 1991 had been 6.5%, with the previous biggest fall being 11%. (Figure 7.2)

Figure 7.1 Smoking prevalence in Australia, Canada, USA, England and Sweden, latest available data

Figure 7.2 Daily smoking, adults 14+, Australia 1991–2013

Interest naturally centred on whether the fall could be attributed to the introduction of plain packaging. Other than the routine twice-yearly consumer price index (CPI) tax increases in each of 2011, 2012 and 2013, bans on point of sales retail displays, a continuation of anti-smoking campaigning throughout the period in question, and measures like smokefree restaurants and pubs that have been in place for many years, the elephant-in-the-room explanatory variable was the implementation of plain packaging in December 2012. Together with almost continuous national news diet of debate about the policy throughout much of the three years in question, no other policy or program presented as a plausible candidate.

In the weeks before this data bombshell exploded, the Murdoch-owned newspaper The Australian had run a major campaign involving three front page stories and whole pages led by IPA-affiliated journalists and contributors (369). They drew on internal tobacco industry data that was never made available for public scrutiny. This mystery data purported to claim a 0.3% increase in consumption following the introduction of plain packs. The treasury quietly released tobacco customs and excise data showing a fall of 3.4% in 2013 relative to 2012 when tobacco plain packaging was introduced. There had been a larger fall between 2010–2011, but that was an exceptional year which saw an unprecedented 25% increase in tobacco tax introduced at the beginning of May 2010. (66) The Australian Bureau of Statistics also released data on expenditure on tobacco for the December 2012 ($3.508b) and the March 2013 ($3.405b) quarters, showing that the introduction of plain packaging was followed by a 2.9% fall in consumption.

The timing of The Australian’s campaign coincided with a final consultation period in England preceding a final decision on a stated intention to introduce plain packs in that country.

17 July unleashed some of the most desperate straw-clutching from the industry and its blogosphere errand boys I have ever seen. Imperial Tobacco and Philip Morris opened the batting, claiming there was no change in the long-term downward trend. BAT issued a press release containing at least two lies. Like Imperial, they said the fall was ‘in line with historical trends’. (370) It wasn’t. It was the biggest percentage fall ever recorded since the surveys commenced. Next, they highlighted the impact of the 2010 tax rise. There had been a 25% tobacco tax increase in early May 2010, but the first five months impact of that rise coincided with the data collection period (29 April – 14 September 2010) for the previous AIHW survey, published in 2011.

Then they referred to the December 2013 12.5% tax rise as an influence. But data collection for the 2011–2013 AIHW report occurred between 31 July 2013 and 1 December 2013, the day an extra 12.5% tobacco tax was introduced. It could therefore have not influenced the data showing the fall.

They also explained that the 12.8% prevalence figure was a fudge because it was only daily smokers. It didn’t include ‘casual’ smokers, whom we were told would lift the true ‘incidence figure’ to 16.4%. (And note here that BAT apparently didn’t know the basic difference between incidence and prevalence.) But they couldn’t even get that right. The AIHW data showed 12.8% daily, 1.4% weekly, and 1.6% less than weekly, making 15.8%. Pathetically, here was BAT desperate to claim as their own those who admit to smoking a cigarette once in a blue moon. Note that the prevalence of those who smoked at any frequency (daily, weekly and less than weekly) fell by 12.2% between 2010 and 2013, another record fall, while the average three-yearly declines over the previous 20 years was just 6.8%.

Then they whined that because the data included the 12–17 year age group (where only 3.4% smoked daily), this would have artificially deflated the ‘true’ figure. This ignores that the 14 years and over figure had been standard in every year since the surveys commenced in 1991, and that between the 2010 and 2013 surveys, smoking fell in every age group above 18 years.

However, a tiny ray of hope remained. A tobacco-loving English blogger noticed that in the 12–17 year age group (the principal target of plain packaging legislation) the percentage of daily smokers actually rose from 2.5% to 3.4%. The jubilant blogger took the trouble to construct a bold graph that emphasised this massive uplift. But he failed to tell his readers that for five of 10 data cells which made up the figures, the standard error was more than 50% (‘too unreliable for general use’) and another two cells with lower standard errors ‘should be used with caution’).

Citi, the global market investment advisors, were in no doubt about the meaning of the data, saying it provided ‘the best data’ to support the British government’s imminent decision to legislate plain packs and that the data would ‘substantially undermine’ the tobacco industry’s argument that there was no good evidence that plain packaging would achieve its stated aims. (371)

This is not likely to be the last round of denials from Big Tobacco. But their hollow denials of impact have now become little more than laugh-a-minute spectator sport.

‘My cigarettes now taste lousy’

One night I had friends over to dinner and decanted a bottle of $15 Australian shiraz into an empty bottle of very expensive French Chateau Margaux that I’d been given as a gift. As I brought it to the table, I spoke about our friendship and how I wanted them to share this special wine. As people took their first careful sips, no one was rapturous, but all said the wine was truly wonderful and commented about its mouth feel, how easily it slid down the throat and how you could ‘taste the French soil’ in French wines. When I quickly revealed the hoax there was long conversation about many experiences with expectations priming experience.

Those studying placebo and nocebo effects in medicine are very familiar with this phenomenon, as is the marketing industry. A study of the influence of pricing on perceptions of the taste of wine shows that my dinner experience was not a one-off example. (372) Those studied reported that a bottle of wine selling at $90 was experienced as more satisfying than exactly the same bottle where the subjects were told the price was $10.

But brain scans showed this phenomenon was not just people saying the $90 wine tasted better, their brain activity showed they really experienced it. Adam Ferrier, a psychologist working in advertising described it this way:

The subjects’ medial orbitofrontal cortex, an area of the brain strongly associated with experiencing pleasure, lit up like a Christmas tree when the subjects tasted the $90 bottle. This is despite, and this is the really interesting bit, the areas of the brain responsible for experiencing taste (the insula cortex, the ventroposterior medial nucleus of the thalamus, or the parabrachial nucleus of the pons) did not light up any differently between the tastes tests of the $10 v $90 bottle. Therefore, even though the taste part of the brain recorded no difference between the bottles, the pleasure part of the brain did. (373)

From 1 October 2012 it was illegal for old ‘branded’ packs to be manufactured in Australia, and for such branded packs to be imported. From this date until 1 December 2012, tobacco retailers could sell both branded and plain packs. Compliant plain packs began appearing in shops from early September and immediately reports began coming in. Shortly afterwards, a colleague dropped by my office and said she’d been to her hairdresser on the weekend and the woman in her 20s who had cut her hair, knowing she worked in health, had told her that she had finally decided to quit: she couldn’t bear the thought of being seen with one of those ugly new packs.

Mike Daube similarly told us:

So I stopped off at the local supermarket to buy a few plain packs and a young woman – she would have been about 20 – who didn’t know me from a hole in the ground, behind the counter, opened the shelves behind her, gave me some packs, pointed to them and said: ‘That made me give up’. That was within days and I thought that’s nice – we do the research, but it’s actually nice to get that personal story.

Anecdotes like this may not be worth much in isolation, but when they move from a trickle to a stream, it’s often a sign of things that will be validated in formal population-wide surveys down the track.

Soon after plain packs came on the market, I took three calls in the space of a week where the callers asked if there had been some sort of tobacco formula change that had accompanied the switch to plain packs. ‘My usual brand tastes really different – far worse’ was the drift of the comments. Other colleagues were getting these calls too, and they were also going to the office of the new health minister, Tanya Plibersek. She told the New York Times:

Of course there was no reformulation of the product. It was just that people being confronted with the ugly packaging made the psychological leap to disgusting taste . . . the best short-term indication I have that it’s working is the flood of calls we had in the days after the introduction of plain packaging accusing the government of changing the taste of cigarettes. (374)

This phenomenon was entirely expected. People in marketing have long understood that packaging can prime expectations. In first days after implementation of the legislation, Adam Ferrier wrote:

This experience has been found to relate to packaging and its contribution to taste in numerous studies, across numerous categories. Packaging strongly influences the taste of something as the brain is looking for cues to help create its story of tastiness (or not).

When tasting a cigarette, all advertising contributes to the taste of that cigarette. People used to see ‘advertising’ as the stuff that belonged on TV. However, marketers today know that every little thing they do is a form of promotion for the brand. Packaging, shelf wobblers, websites, the cars the sales team drive, the sales team – they are all marketing, and they are all forms of advertising. And of all of them, packaging is arguably the most important contributor to the brand for three reasons; (a) it’s on 24-hours a day, (b) it’s experienced at point of purchase, (c) it was completely under the marketers control. This was especially true for cigarette manufacturers who had other advertising levers pulled from them years ago.

Cigarette packaging – with its bright colours and symbols of freedom and power – was a cue that this product tasted nice. It made the cigarette more enjoyable. Now these images have been replaced with images of disease and an unpleasant olive green (itself a colour associated with sour taste). There are few cues left that suggest the product will ‘taste’ nice. Consumers will begin to taste, you guessed it, smoke!

If this is the hallmark of a nanny state, then as the son of a smoker who died of cancer way too young I happily say ‘Goo goo ga ga. Keep looking after us.’ (373)