6

Legal challenges, massive costs

The legislation has already faced one legal challenge (the one in the High Court of Australia) and is set to face two more:

- World Trade Organization (WTO) disputes

- the challenge under Australia–Hong Kong Bilateral Investment Treaty.

The High Court of Australia

When the passage of the government’s bill on plain packaging became assured with the support of the Opposition, the Greens and key independents, an ever-desperate tobacco industry began to concentrate on threatening the legal apocalypse that they promised would descend on Australia first through the High Court and if necessary, through international trade bodies like the WTO. Indeed, within hours of the April 2010 political announcement of plain packaging, two tobacco companies (BAT and Imperial) declared they would challenge the decision in court using seizure of intellectual property arguments, and seek billions in compensation. (eg: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wEXH7mqEEWE) and Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 BATA advertisement about the ‘billions’ government might have to pay in compensation.

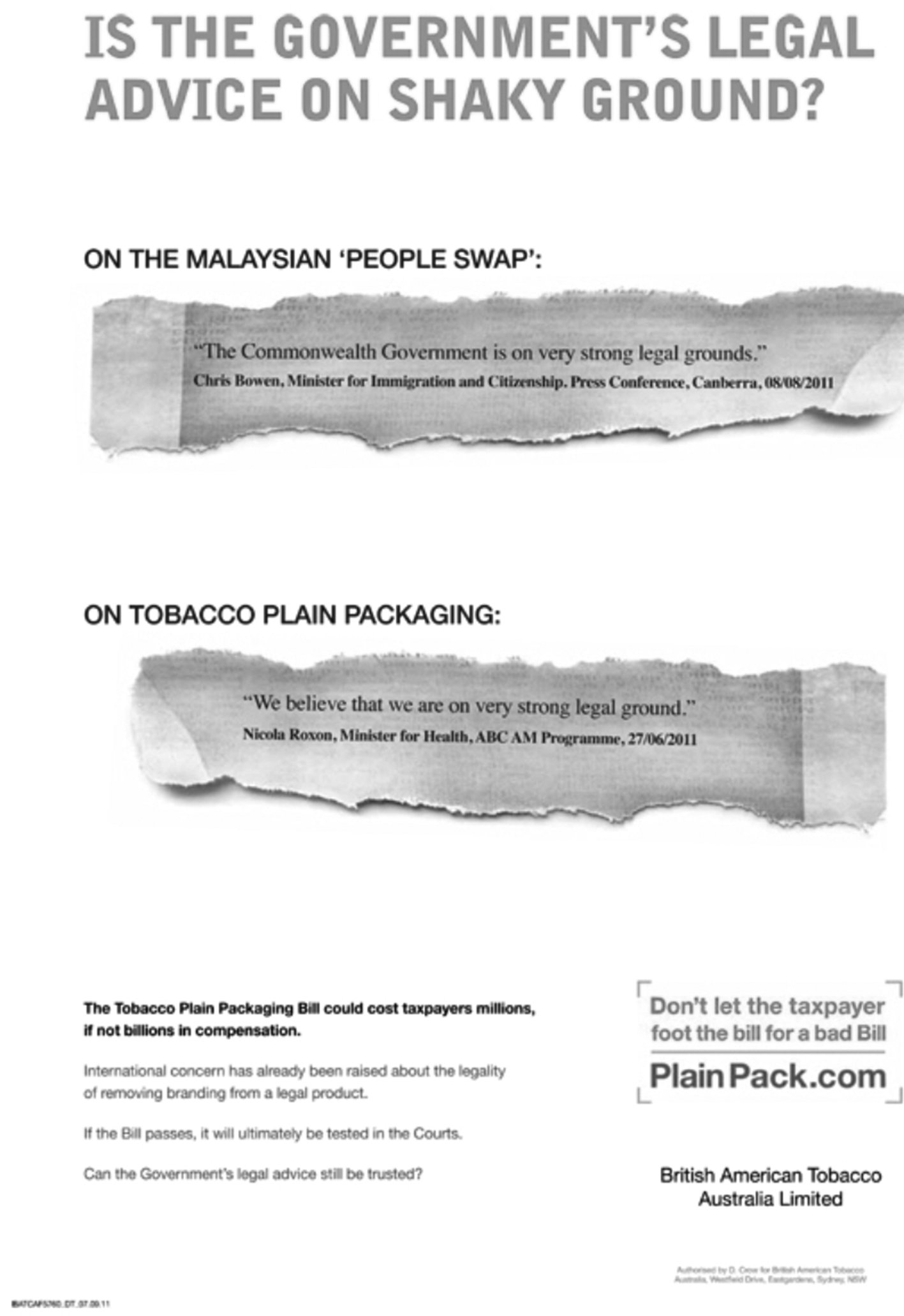

BATA ran several ads promoting the idea that plain packaging would see the government, and therefore ultimately the taxpayer, having to incur stratospheric legal bills and pay out compensation to tobacco companies. Figure 6.2 shows an advertisement arguing that the government has had poor legal advice before, and plain packaging was likely to be another example.

These arguments were a house of cards, starting with the central problem that plain packaging would not extinguish the industry’s valued brand identities. All packages would still carry brand and variant names, allowing smokers to clearly exercise their freedom to select between the much-vaunted but often non-existent differences in brands. In the highly unlikely event of a ruling by the High Court in favour of the industry, any calculation of compensation would need to take account that branding differences had only been diminished, not extinguished. The companies would have needed to demonstrate with precision that sales losses arose from losing colours, logos and different pack shapes, but not brand names and variants.

Few of those megaphoning this legal Armageddon appeared to have even read the draft bill itself. Section 11 of the bill made it clear that plain packaging would not proceed if it were to be determined (by a court) that its operation would result in an acquisition of property other than ‘on just terms’. So in the unlikely event that the High Court determined there was an acquisition of property (more on this below), Section 11 created a fallback provision under which ‘the trade mark may be used on the packaging of tobacco products, or on a tobacco product’ in accordance with requirements to be prescribed in subsequent regulations.

In other words, the bill had been drafted with a get out of jail free card under which plain packaging would not proceed if the High Court ruled that it involved an unjust acquisition. As a result, there could have been no compensable damage or loss incurred by any tobacco company mounting a legal challenge before implementation of the Act, even if such a challenge was successful.

Moreover, Monash University’s Mark Davison explained:

As for the constitutional argument that the legislation acquires property on other than just terms, Professor Craven, a noted constitutional expert, has since observed on Radio National’s Background Briefing that the tobacco industry’s prospects of success are about the same as a three-legged horse has of winning the Melbourne Cup. The reason for his view is simply explained. The extinction of rights or the reduction of rights is not relevant. The government or a third party must acquire property as a consequence of the legislation. The government did not want to use the tobacco trademarks. Nor does it want third parties to do so. It does not desire to or intend to acquire any property. The proposition that prohibitions on the use of property do not constitute an acquisition of property was confirmed by the High Court as recently as 2009. In that case, the High Court held that the government was entitled to extinguish property rights in licences of farmers to take bore water. (287)

Immediately the tobacco companies began threatening legal action, Australian legal experts in constitutional and intellectual property law began publicly ridiculing their prospects of success. Professor George Williams (University of New South Wales) said: ‘The Commonwealth is able to regulate the use of IP [intellectual property] and that is quite different to it acquiring that property.’ Professor Greg Craven (Australian Catholic University) said: ‘I’m sure it would fascinate the High Court all the way to deciding “No”’ and Professor Mark Davison (Monash University) described the industry’s argument as:

. . . so weak, it’s non-existent. There is no right to use a trademark given by the World Trade Organization agreement. There is a right to prevent others using your trademark but that does not translate into a right to use your own trademark. (330)

In May 2010, Tim Wilson of the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) participated in a seminar on plain packaging at Melbourne University. Wilson’s videoed contribution can be seen here (http://vimeo.com/12106765), where ‘as a staunch constitutionalist’ he summarised his take on the various laws and international treaties said to be possibly relevant to a case against plain packaging. The next speaker, Professor Mark Davison, critiqued Wilson’s presentation in a demolition job that went near to being academic bloodsport for many of those present. (266)

Of Wilson’s constitutional argument that plain packaging would be an acquisition of property by the Australian government, Davison had this to say:

I thought for example, you might have . . . I don’t know . . . picked up a textbook. Look[ed] at a case. See, there is no acquisition of property being proposed here. The mere extinguishment or deprivation of rights in relation to property does not involve acquisition. The government does not want the pretty pictures [the branding colours and logos]. It wants them not used. [pointing to his slide] There are six cases. Six. And there are a lot more, that say precisely that . . . (see http://vimeo.com/12108576)

No tobacco company ever compensated for pack health warnings

Governments all over the world have been ‘seizing’ parts of the intellectual property of tobacco companies since 1966 when the United States became the first nation to require packs to carry a health warning. Over the next 45 years, these warnings have become slowly more detailed and explicit, embracing language like ‘addiction’, ‘cause’ and ‘kill’ that saw protracted national and global lobbying against every new step that was taken. After Canada became the first nation in 2000 to introduce graphic, pictorial warnings in full colour, 63 nations followed suit over the next 12 years, with Uruguay leading the way with 80% front and back, until Australia’s new requirements saw it temporarily become the new leader with 75% of the front and 90% of the rear given over to health warnings. Thailand took the lead in June 2014 when it required 85% of the front of the pack to be a graphic heath warning.

But in all these years, no tobacco company has ever received a cent in compensation from any government for these sometimes massive appropriations. There were no financial barriers to any tobacco transnational taking legal action against governments for this heinous alleged theft of a part of their intellectual property. Such actions would have posed negligible financial barriers to any tobacco transnational. The big stick of legal action and compensation the industry keeps warning governments that they hold behind their backs is the threat of legal action and massive compensation for trademark violation. But as we shall see, in the case of Australia – at least within the domestic legal system – this was a big case of crying wolf.

The $3 billion compensation factoid

There’s nothing quite like the threat of a massive legal penalty to get headlines and frighten the political horses about proposed legislation. A big number is required for such threats and the number that was selected for plain packaging that the government was said to be facing was $3 billion . . . per year! So where did this satisfyingly very large number come from? It began circulating in May 2010 and was repeated many times in the months ahead by frothing radio shock-jocks, and by some who should have known better.

Step forward Tim Wilson, the then ‘director of intellectual property’ at the tobacco industry-funded IPA. Wilson is a prominent ideological spear-carrier for deregulation and a sworn enemy of the odious nanny state. In 2014 he was appointed by the new Abbott-led conservative government as a Commissioner for Human Rights, with a focus on ‘free speech’. In late April 2010, just a month after the government had announced its intentions with plain packs, while not holding a law degree, Wilson was all over the Australian news media promoting the likelihood that the Australian government would be hit with a compensation bill of up to $3 billion a year for having ‘confiscated’ the tobacco companies’ intellectual property in the form of their packaging. (331)

So where did Wilson get his $3 billion number from? What were his ‘rough calculations’ (332) as he described them in The Australian newspaper? Wilson sent a submission to the Senate Community Affairs Committee enquiry into the Family First-proposed Plain Tobacco Packaging (Removing Branding from Cigarette Packs) Bill 2009 which had been triggered by a bill proposed by the one-term Families First Party Senator, Steve Fielding. The submission was based on an IPA report also authored by Wilson. Here, (333) in all its embarrassing glory, we can examine Wilson’s prowess with the numbers and the birth of one of the most ludicrous factoids in many years. His report’s subtitle, presumably added with no trace of irony, was Australian governments legislating, without understanding, intellectual property.

In his executive summary, Wilson provided ‘an indicative calculated range’ of between $378m and $3027m per year that a High Court order under Section 51 (xxxi) of the Australian Constitution could award the tobacco industry over plain packs. From whence did Wilson pluck these estimates? Table 2 in his report shows two lines of numbers showing the total value of tobacco sales in Australia in 2006: one for the value including excise tax and one for the sales value ex-tax. Excise tax is paid by tobacco companies to the government, but is then repaid to tobacco companies by smokers when they purchase tobacco. This means that it is smokers, not the tobacco companies, who actually pay the tax. The sales value ex-tax represents the returns to manufacturers and retailers combined.

By taking the trouble to differentiate the two like this, Wilson must have known that no court would order the return of the tobacco tax component of retail sales to the companies, for the elementary reason that they never would have been entitled to that component of the retail price: it is the ex-tax value only that fuels the industry’s pipedream of massive compensation should any government be silly enough to take the plain packs route. Wilson then calculated the tax-included and the ex-tax values on two assumptions: a 10% and a 30% fall in sales each year that might follow the introduction of plain packs. He calculated these two figures at $378m and $1.135b. So where does the $3b factoid come from? Are you ready for this? The tax-included sales value of a 30% fall is $3.027b – the biggest number on the page.

Even setting aside inclusion of tax in this $3 billion figure, how reasonable were Wilson’s assumptions that plain packs would cause a fall of a minimum 10% through to 30% each year? Between 1999 and 2003 the average annual fall in total dutied cigarettes was just 2.6%. The most sales have ever fallen in one year was just shy of 10% in 1999 after the combined impact of a change in the way cigarettes were taxed (from weight to per stick) and a big budget boost to the national quit campaign by the then Liberal health minister Michael Wooldridge.

Wilson’s $3 billion number was thus based on a projected decline which was the stuff of fantasy land. Worse, it appeared to be a wilful selection of the tax-included biggest number he could sight in his own specious table. To the delight of the industry, it quickly became a virulent factoid. Google ‘$3 billion’ and ‘plain packs’ and you will see what we mean.

ABC television’s Media Watch program was tipped off about Wilson’s antics and ran a segment about his claims in May 2010. (334) Media Watch is said to be a program that many people like to watch but no one wants to appear on. The segment highlighted the policy of the IPA, Wilson’s employer, of never disclosing its funders. This is a paradoxical position to take for an organisation obsessed with freedom of speech. A tape of Wilson saying on radio that: ‘any funding [they might have from the tobacco industry] has no impact on the policy positions we take whatsoever,’ was included in the Media Watch segment, with the host noting that Wilson undoubtedly ‘sincerely’ held his views, regardless of whether the IPA was funded by Big Tobacco or not. However, another IPA employee Alan Moran, told a Productivity Commission enquiry in 2001 that ‘. . . the IPA doesn’t represent anyone in particular . . . we don’t represent the firms. . . there are occasions when we may take positions which are somewhat different from those of the funders. Obviously that doesn’t happen too often, otherwise they’d stop funding us.’ (335)

Undeterred by any suggestion that the tobacco industry may have had any influence over the IPA’s views on plain packaging or on Wilson’s economic flatulence, The Australian’s Christian Kerr (who has also written for the IPA) kept the flame alive as late as mid-September 2010 for Wilson’s ‘rough’ calculation, describing it as an ‘independent estimate’ (336).

In September 2011, when the plain packaging bill entered the Senate’s Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee, David Crow of BATA affirmed the ‘billions’ ballpark figure.

Senator Cash: In relation to your submission at 7.2, you actually state whilst the amount of any compensation would ultimately be a question of the courts, commentators have put a compensation figure for the TPP [Trans-Pacific Partnership] bill and the proposed increase in graphic health warnings could be in the vicinity of $3 billion. Is that a fair estimate? Is that an estimate that you have had a look at? Is that just a figure that has been plucked out of the air?

Mr Crow: No, we are currently doing work on trying to do the evaluations of this, getting ready for any potential challenge.

Senator Cash: Are we talking millions, hundreds of millions or billions?

Mr Crow: It would be in the billions.

Senator Cash: It is in the billions?

Mr Crow: I think when they reviewed it in 1995 . . .

Senator Brandis: In the billions, did you say?

Mr Crow: In the billions, yes. Our business is worth approximately probably $7 billion or $8 billion. The brands would be worth roughly probably half of that.

In June 2013, the matter of whether the IPA received funding from the tobacco industry was settled when BAT’s Simon Millson confirmed in a letter to ASH (London) that it was a corporate member of the IPA. (337)

The judgement

The tobacco industry’s challenge in the High Court of Australia commenced in Australia in April 2012 and judgement was handed down in August, with the reasons for judgement published in October of the same year. (338) The case against the Commonwealth of Australia was brought by five tobacco companies (British American Tobacco Australasia Ltd, Imperial Tobacco Australia Ltd, JT International SA, Nelle Tabak Nederland BV and Philip Morris Ltd). Of the full bench of seven judges hearing the case, six rejected the pleadings brought by the plaintiffs. The McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer provides a good summary of the case made by the applicants, the reasons for the judgement and many links to scholarly commentaries and media coverage of the case. (339) A paper by Jonathan Liberman, the centre’s director, also provides an excellent review. (340) A slightly edited version of the McCabe Centre summary follows.

In challenging plain packaging, the tobacco industry made two principal arguments:

. . . that the restrictions on its property and related rights (including trademarks, copyright, goodwill, design, patents, packaging rights and licensing rights) effected by the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act and Regulations constitute an acquisition of its property (for which just terms had not been provided); and

that the Act and Regulations give the Commonwealth the use of, or control over, tobacco packaging, in a manner that effects an acquisition of the tobacco industry’s property (for which just terms have not been provided).

In her judgement, Justice Crennan observed that what the tobacco industry ‘most strenuously objected to was the taking or extinguishment of the advertising or promotional functions of their registered trademarks or product get-up’.

The essence of the 6:1 majority’s reasons for dismissing the tobacco industry’s challenge is set out in the summary provided by the court:

On 15 August 2012 the High Court made orders in two matters concerning the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (‘the Act’). Today the High Court delivered its reasons in those matters. A majority of the High Court held that the Act was valid as it did not acquire property. It therefore did not engage s 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution, which requires any acquisition of property effected by a Commonwealth law to be on just terms.

The Act imposes restrictions on the colour, shape and finish of retail packaging for tobacco products and restricts the use of trademarks on such packaging. The plaintiffs brought proceedings in the High Court challenging the validity of the Act, arguing that the Commonwealth acquired their intellectual property rights and goodwill otherwise than on just terms.

A majority of the Court held that to engage s 51 (xxxi) an acquisition must involve the accrual to some person of a proprietary benefit or interest. Although the Act regulated the plaintiffs’ intellectual property rights and imposed controls on the packaging and presentation of tobacco products, it did not confer a proprietary benefit or interest on the Commonwealth or any other person. As a result, neither the Commonwealth nor any other person acquired any property and s 51 (xxxi) was not engaged.

All six members of the majority affirmed that under the Australian Constitution, for there to be an ‘acquisition of property’ requiring just terms compensation, the Commonwealth or another must obtain a benefit or interest of a ‘proprietary nature’. As Justices Hayne and Bell put it, this is a ‘bedrock principle’ which must not be eroded: ‘There must be an acquisition of property’ (emphasis in the original). The tobacco industry’s arguments ‘[ran] aground’ on this bedrock.

As (now Chief) Justice French expressed it:

On no view can it be said that the Commonwealth as a polity or by any authority or instrumentality, has acquired any benefit of a proprietary character by reason of the operation of the TPP Act on the plaintiffs’ property rights.

The achievement of the Commonwealth’s legislative objects would not be such a benefit. As Justice Kiefel wrote, if the Act’s central statutory object were to be effective, the tobacco companies’ business ‘may be harmed, but the Commonwealth does not thereby acquire something in the nature of property itself’.

In addressing the tobacco industry’s argument about use of, or control over, packaging, Justices Hayne and Bell observed that the requirements of the Act:

. . . are no different in kind from any legislation that requires labels that warn against the use or misuse of a product, or tell the reader who to call or what to do if there has been a dangerous use of a product. Legislation that requires warning labels to be placed on products, even warning labels as extensive as those required by the TPP Act, effects no acquisition of property.

Justice Crennan noted that: ‘Legislative provisions requiring manufacturers or retailers to place on product packaging warnings to consumers of the dangers of incorrectly using or positively misusing a product are commonplace’. Similarly, Justice Kiefel wrote that: ‘Many kinds of products have been subjected to regulation in order to prevent or reduce the likelihood of harm’, including medicines, poisonous substances and foods.

Justice Crennan underlined the significance of the tobacco industry’s ability to continue to use brand names on tobacco packaging, ‘so as to distinguish their tobacco products, thereby continuing to generate custom and goodwill’. She noted that the ‘visual, verbal, aural and allusive distinctiveness, and any inherent or acquired distinctiveness, of a brand name can continue to affect retail consumers despite the physical restrictions on the appearance of brand names imposed’ by the Act; ‘an exclusive right to generate a volume of sales of goods by reference to a distinctive brand name is a valuable right’.

The High Court’s judgement reverberated around the world, confirming the analyses of many legal scholars and commentators who had anticipated the judgement almost to the letter. Those few who had confidently predicted that the court would order the Australian government to compensate the companies to the tune of ‘billions’ were oddly silent.

The IPA’s Tim Wilson was one who kept quiet. What had he learned from all this? In February 2014, a reporter included the following exchange in a magazine portrait of Wilson (341):

But would Wilson concede he was wrong on plain packaging?

‘No.’

‘Have you ever been wrong on anything?’ I ask.

‘I’m sure there have been things,’ he says. ‘But I can’t think of them right now.

World Trade Organization disputes

While plain packaging has been upheld domestically in Australia’s highest court, challenges in international law are ongoing at the time of writing.

In the World Trade Organization, five governments – Ukraine, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Cuba and Indonesia – have initiated complaints against the Australian government’s plain packaging law.

In May 2014 the WTO composed the three person panel who will examine the dispute of the five complainants together. (342) The panel will next set a timetable for hearing the dispute. Typically, the WTO’s dispute settlement system aims for panel reports to be provided to all parties approximately six months from the panel’s appointment, and then to all WTO members three weeks later. However, due to the large number of complainants and the complexity and breadth of the issues argued, it is likely this panel will take much longer. If either party appeals, the matter will be considered by the WTO’s appellate body, which is expected to provide its report within a few months.

With the exception of Indonesia, none of these nations have any significant trade of any sort with Australia, let alone in tobacco products. (343, 344) For all Big Tobacco’s outraged global tub-thumping about plain packs and its success in whistling up sternly worded submissions from a variety of US-based trade associations, it is telling that with the exception of the geopolitically very important neighbouring country of Indonesia, these other puppets are the heaviest hitters it could influence to run its case with the WTO. Big Tobacco’s best team are nearly all global minnows.

It has been reported that Philip Morris is providing support to the Dominican Republic, and that British American Tobacco is doing the same for Ukraine and Honduras. (345)

The WTO complaints are based on three WTO agreements: the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), In essence they claim that what Australia has done is unnecessarily burdensome to trade, that the new law is somehow discriminatory, that it is more trade restrictive than necessary, and that it unjustifiably infringes upon trademark rights.

Australia argues that its laws are a sound, well-considered measure designed to achieve a legitimate objective – the protection of public health. It is vigorously defending the complaints.

Several legal scholars have published detailed examinations of the merits of Australia’s stance that its laws comply with WTO obligations. (346, 347) In support of Australia’s position, the McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer notes that the laws represent a sound exercise of Australia’s sovereign power to regulate, are non-discriminatory, are based on evidence, are well-drafted and have behind them the legal and political force of the WHO FCTC, its article 11 and article 13, other decisions of its Conference of the Parties, and other international instruments including the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. (348)

Many governments restrict trade for health and cultural reasons

In all this, it is also important to reflect that there are many examples of governments introducing strong restrictions, bans or penalties on the sale or promotion of different commercial products for cultural or health reasons. Many nations – including Australia (349) – severely restrict civilian access to firearms. Asbestos products are banned in several nations. Pharmaceutical products are subject to stringent formulation, dosage, access, packaging and sales controls, with direct-to-consumer advertising of prescribed products allowed in only two nations (the USA and New Zealand). Several Islamic nations totally prohibit the sale of alcohol. Food safety regulations have been accepted as the norm for many decades. Many nations impose strict quarantine regulations on the importation of exotic animals, insects and biological material. Every year, governments ban or restrict consumer goods deemed to be unsafe. Prohibitions on pornography are common in many nations, while not in others.

We have not seen, for example, firearms manufacturers seek to lobby nations to bring cases to the WTO or other global tribunals in an attempt to force such nations to relax their gun control laws. This is because of the principle of nations being able to have sovereignty over their own internal laws and regulations.

Restrictions and regulations on tobacco packaging need to be seen against this background and against the exceptionally deadly and addictive status of tobacco – a product which sees half of its long-term users die prematurely from using the product directly as intended by the manufacturers. In this, tobacco is unique among all consumer goods; one of the reasons why tobacco was also the subject of the world’s first global health treaty, now ratified by 178 nations – the WHO’s FCTC. (75)

What if Australia were to lose in WTO?

WTO rulings against a nation can result in the WTO sanctioning trade retaliation against the nation. So in the highly unlikely event that Australia were to receive an unfavourable decision in the WTO, the prospect of Australia being subject to trade retaliation from nations like Honduras and Ukraine with whom it has negligible trade would involve all the pain of being flogged with a damp lettuce leaf. Notwithstanding this, the Australian government would probably seek to ‘bring itself into compliance’ by bringing the legislation into compliance with any ruling given, in order to preserve its reputation as a country that follows international trade rules.

Challenge under Australia – Hong Kong Bilateral Investment Treaty

After losing the challenge in the Australian High Court in 2012 (along with five other companies), Philip Morris, through Philip Morris Asia (PMA), has brought proceedings against the Australian government under a bilateral trade agreement between Hong Kong and Australia signed in 1993. (285) The claim being made is that the Australian plain packaging law breaches the agreement between the government of Hong Kong and the government of Australia for the promotion and protection of investments. This bilateral investment treaty is known as the BIT, hence is known as the BIT claim. (350)

Unlike in the WTO system, this agreement contains a dispute settlement provision which permits investors, in this case a tobacco company, to bring their own claim against governments directly. PMA has made a number of arguments, including that plain packaging would expropriate its intellectual property, and that it has not been afforded fair and equitable treatment. PMA is seeking ‘billions of dollars’ in compensation for potential corporate losses arising from the new legislation. (351)

The timeline of facts/events in this instance are likely to be of critical relevance to the prospects of the case. On 29 April 2010, the Australian government announced its intention to introduce plain packaging. At that time Philip Morris tobacco products in Australia were manufactured by Philip Morris Australia. On 23 February 2011, Philip Morris Asia purchased Philip Morris Australia and on 27 June 2011 – a full 14 months after knowing the government intended to introduce plain packs – PMA served its notice of claim to the Australian government. (285)

Why is this sequence of events important? Imagine someone considering purchasing a property who had learned, 14 months earlier, that the property would be badly affected by a new freeway being built nearby. Then imagine them going ahead and purchasing the property. And then imagine them taking the government to court for compensation over damage to their investment. The PMA case would seem to have the same prospects, quite apart from all the arguments against the idea that a trade treaty should be able to override any government’s sovereignty in public health matters in perpetuity.

The proceedings are governed by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law Rules of Arbitration 2010 (UNCITRAL Rules), (352) and are being overseen by a three-member arbitral tribunal. (353) The process of arbitration differs from that in the WTO in several respects. Despite the Australian government’s expressed commitment to transparency in investor-state arbitration and request for open hearings and published hearings, PMA has requested that the case be heard in secret and only limited documents published (with redactions), as it is entitled to do under the UNCITRAL rules. (354)

Mark Davison (285) was convinced that the case for compensation was worthless.

Article 6 of the BIT specifically refers to how compensation should be calculated. It states that the compensation shall amount to ‘the real value of the investment immediately before the deprivation or before the impending deprivation became public knowledge whichever is the earlier’.

The investment is defined in Article 1 of the BIT as the investment of the Hong Kong investors, that is, PMA. So what was the value of the ‘investment’ that PMA had before the impending ‘deprivation’ became public knowledge? It seems that it did not have any investment at all at the time that the impending ‘deprivation’ became public knowledge.

No doubt PMA will have some argument on the point but, as a general rule, the value of nothing is nothing.

It appears that PMA’s claim for ‘billions of Australian dollars’ has about as much life as the parrot in the famous Monty Python sketch. (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqz_4OgMi7M) It will be interesting to see whether PMA argues that its claim is just resting or, perhaps, just temporarily stunned by the Australian government taking it out of its cage and giving it a good hard whack with the facts.

In April 2014, Australia received a favourable order when the tribunal decided to divide the proceedings into two phases (the ‘bifurcation question’), in line with a request by Australia. As a result, the tribunal will now first examine the jurisdictional objections raised by Australia and will only then turn to the argument on the merits, if necessary.

Australia is arguing that the tribunal does not have jurisdiction to hear the case for three reasons, summarised in an email circulated by the US-based Tobacco Free Kids:

- The dispute falls outside of the scope of the Treaty because PMA did not have any relevant ‘investment’ in Australia at the time the introduction of plain packaging was announced on 29 April 2010. PMA only acquired its interest in Australia on 23 February 2011, 10 months after the government announced plain packaging.

- Further or in the alternative, PMA’s ‘investment’ needed to be ‘admitted’ by Australia subject to its foreign investment laws and policies. The burden of proof falls on PMA to prove that its investments were so admitted, a burden which it has not discharged.

- Further or in the alternative, PMA’s claim relies heavily on a series of treaties over which an arbitral tribunal could have no jurisdiction. The Treaty’s article 2 (2) umbrella clause does not extend to obligations owed by Australia to other states under multilateral agreements. Even if it were correct (which it is not) that article 2 (2) could somehow be understood as extending the tribunal’s jurisdiction to obligations Australia owes pursuant to other treaties, all of those treaties have their own dispute settlement mechanisms. It is not the function of the tribunal to establish a roving jurisdiction to make determinations that would potentially conflict with the determinations of the agreed dispute settlement bodies.

The court will deal with these jurisdictional arguments as a preliminary matter. If Australia prevails, the case brought by PMA will be dismissed. Bifurcation is beneficial to Australia because the case will be dealt with more expediently and the financial and other resources expended by the parties will be reduced if the case is decided in this first phase. The hearing of this first phase has been set down for three business days (and two additional days in reserve) from 16 February 2015 in Singapore.