5

Plain packaging – why now? And why Australia?

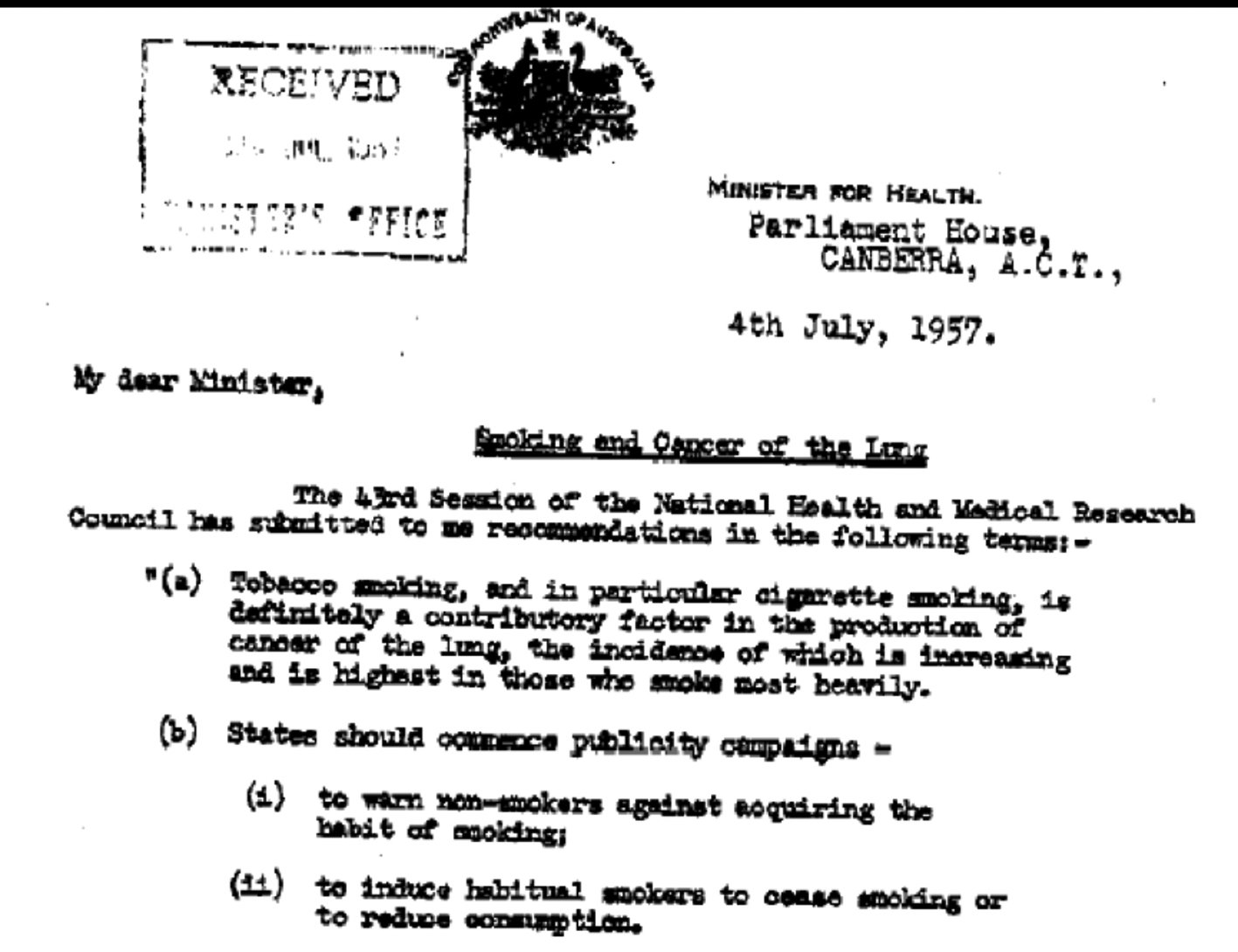

Any history of tobacco control in Australia, and indeed in nearly all nations, would report with incredulity the lack of urgency in the pace with which governments went about trying to reduce smoking. In Australia, in 1957 the NHMRC noted the research being published from 1950 in the USA and Britain on the association between lung cancer and smoking, and recommended to the minister for health that publicity campaigns should be considered to warn the public about the risks (see Figure 5.1).

It took another 16 years before Australians saw the first health warnings peeping in small font from the bottom of cigarette packs. And it was not until 1982 – 25 years later – that any significant (multimedia) statewide anti-smoking campaigns commenced in Australia at a level going beyond simple posters and pamphlets.

Smoking was first banned in cinemas, in public halls and on buses and trains from the mid-1970s. The Australian Capital Territory began to stop indoor smoking in pubs and bars under health ministers Wayne Berry (1994) and Michael Moore (1998), but other states and territories delayed until 2005 and later.1

Advocacy for banning smoking in cars carrying children commenced in Australia in 1995. It took until December 2007 – another 12 years – before Tasmania became the first state to introduce legislation on smoking in cars in Australia. (239)

Direct forms of tobacco advertising ended on Australian radio and television in September 1976, but it was another 16 years until all remaining forms under the control of Australian governments ended with the 1992 Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act.2

Figure 5.1 Extract of letter from NHMRC to minister for health, 4 July 1957

Those working in tobacco control in Australia were therefore used to long gaps, perhaps of decades, between early advocacy for a proposal and its eventual complete political adoption. All major advances in tobacco control policy have been subject to heavy attack and sustained lobbying by the tobacco industry. As outlined in Chapter 1, there had been advocacy for plain packaging since the late 1980s, with the evidence base steadily growing. It is always interesting to consider what makes proposals once considered radical, like tobacco advertising bans and smokefree public places, morph into sensible ideas whose times have now come.

Table 5.1: Major milestones in the introduction of plain packaging in Australia

| Year | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 9 April: Nicola Roxon announces establishment of the National Preventative Health Taskforce |

| 10 October: Release for consultation of the draft report of the National Preventative Health Task Force recommending plain packaging (240) | |

| 17–22 November: Parties to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control adopt guidelines on advertising and package labelling that recommend the use of plain packaging (241) | |

| October 2008 to February 2009: Public submissions and consultation sessions by the National Preventative Health Taskforce (242) | |

| 2009 | 30 June: National Preventative Health Task Force provides final report to government (243) |

| 1 September: Minister releases final report of the National Preventative Health Task Force, which includes recommendation on plain packaging | |

| 2010 | 29 April: Kevin Rudd and Nicola Roxon announce plain packaging will be introduced (244) and an immediate 25% increase in tobacco tax |

| 24 June: Prime minister Kevin Rudd deposed by deputy prime minister Julia Gillard | |

| 4 August: Public launch of tobacco industry astroturf group, Alliance of Australian Retailers | |

| 21 August: Federal election. Gillard government returned to power, but relies on support from three crossbench members in House of Representatives to pass legislation | |

| 12 September: Coles and Woolworths withdraw from Alliance of Australian Retailers | |

| 2011 | 1 March: Release of Deloitte report on illicit trade |

| 7 April: Australia notifies the WTO of its intention to implement plain packaging (245) | |

| 17 May: BATA launches major advertising campaign against plain packaging | |

| 31 May 31: Nicola Roxon honoured by WHO; Coalition decides it will not oppose plain packaging legislation | |

| June: 260 submissions received by government on bill (246) | |

| 7 June: First discussion at WTO of Australia’s move (247) | |

| 21 November: Final passage of amended bill through House of Representatives (248) | |

| 21 November: Philip Morris Asia Limited, Hong Kong, owner of Australian affiliate, Philip Morris Limited, announces that it has begun legal proceedings (249) against the Australian government by serving a notice of arbitration under Australia’s bilateral investment treaty with Hong Kong | |

| 2012 | 17 April: High Court case commences |

| 15 August: High Court decision | |

| 1 October: Henceforth illegal to manufacture or import fully branded packs | |

| 1 December: Plain packaging fully implemented – henceforth illegal to sell any non-complaint packs |

Table 5.2: Milestones in passage of Plain Packaging Bill through Australian Parliament, 2011

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| 6 July3 | Bill introduced into House of Representatives, read and second reading moved (250) |

| 7 July | House of Representatives refers bill to Standing Committee on Health and Ageing (251) |

| 22 July | Submissions close for House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing – Inquiry into Tobacco Plain Packaging Bill 2011: 63 submissions received (252) |

| 4 August | Hearings of the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing (253) |

| 18 August | Senate refers bill to Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee which calls for submissions by 2 September (254) |

| 22 August | House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Aged Care tables the report on its inquiry into plain packaging (255) |

| 24 August | Second reading debate, third reading agreed to passage of legislation through House of Representatives (250) |

| 25 August | Bill introduced and read a first time in Senate, then second reading moved (250) |

| 2 September |

Submissions received by Senate’s Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee (256) |

| 13 September |

Hearings of the Senate’s Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee (257) |

| 11 October |

Second reading debate in Senate commences (250) |

| 2 November |

Nicola Roxon, announces that the implementation of plain packaging will be delayed until 1 December 2012 as a result of delays in the Senate review of the bill (258) which followed industry lobbying |

| 9–10 November |

Second reading debate continues and second reading agreed to. Third reading agreed to (with amendments) (250) |

| 21 November |

Final passage of amended bill through House of Representatives. Vote on Tobacco Plain Packaging Bill and Trademarks Amendment Bill as amended by the Senate. (250) Official Hansard No 18, Monday 21st November, Forty-third Parliament, First session – Fourth period 2011:12913. (248) |

| 28 November |

Signing into law by Governor General of Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (72) |

I asked Nicola Roxon a question asked of me many times: ‘What made the government you belonged to take such an important step?’ She emphasised several factors, including the evidence base, the reputation and coherence of the tobacco control community, and expertise in the public service, legal profession and in the public health sphere.

The evidence base

Roxon repeatedly highlighted the critical role that evidence played in the government’s decision to adopt plain packaging. The public health effort to reduce smoking in Australia from as far back as the 1970s has been an evidence-based enterprise. Australian researchers have been major contributors to the international research literature in all areas of tobacco control.

The most important group researching tobacco packaging in Australia has been Professor Melanie Wakefield and her team at the Cancer Council Victoria. The Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer at Cancer Council Victoria was established in 1986 as a scientific research centre specialising in the understanding and monitoring of behaviours that contribute to cancer, and in the evaluation of programs and policies aiming to change such behaviours. It is funded largely through competitive research grants which depend on the high levels of academic rigour and strong track records of publication in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. As noted in the government’s response to the recommendations of the National Preventative Health Taskforce, the results of studies by Wakefield et al of the effects of reducing design features on smokers’ perceptions of attractiveness and social desirability of smoking provided important evidence of the potential impact of plain packaging. Wakefield also advised the government on research it conducted to guide the design of standardised packaging and size and placement of health warnings.

An associate of the centre, Dr Michelle Scollo also deserves particular mention. Her meticulous and encyclopaedic data banks on nearly every aspect of tobacco control in Australia that form the backbone of the massive online resource, Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues (http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/), and her peerless grasp of issues concerning tax and apparent consumption, brought invaluable expertise to the development and evaluation of plain packaging.

Reputation and coherence of Australian tobacco control community

As well as the research evidence on the appeal of tobacco packaging, another crucial factor in the government’s decision to proceed was the national and international reputation of Australian tobacco control in all its achievements over the previous decades. Roxon said:

It was an attractive next step after all the Australia had done successfully over decades. It would be fair to say that there wasn’t any groundswell from the public service at that time [about plain packs]. The taskforce pulling together the evidence and presenting options helped move that significantly – and they [the public servants] were very enthusiastic converts once we, as government ministers, said we were interested in it. My interest was definitely sparked by the cohesive arguments the whole public health community in Australia put to us. Without their track record, the strong impression made when groups put those ideas to us would have been much weaker.’

The tobacco control research and policy advocacy communities in Australia have long been a relatively small, tightly knit, personally close and extremely communicative network. Most of the leading individuals in these communities today have been working in it for well over 10 years, with several approaching or exceeding 30 years. (259) Their strategic research contributions and advocacy have often been followed by sweeping policy change successes, such as ending all forms of tobacco advertising and promotion and the roll-out of smokefree areas. Unlike some other areas of public health where policy goals are more complex and nuanced, tobacco control’s goals have long been clear and consistent.

Roxon was very aware of this coherence, talking about:

. . . well respected people, coordinated. So not 10 different people all asking for 20 different things. That [cohesiveness] happens much more rarely than you would imagine in politics. I think the value of the cut-through of a message like that, and how easy it then is for governments to pick it up, shouldn’t be underestimated.

She also emphasised the attraction of plain packaging as being a strategy that would not be expensive for government to implement, with all packaging costs being borne by the companies. ‘What were the options for interventions that could have an impact and not necessarily be expensive?’ she asked. ‘Plain packaging ticked that box.’

Besides the researchers who were publishing the evidence for the policy, there were several other groups of highly skilled and experienced individuals working in different areas to whom Roxon would have been referring as ‘well respected’ people.

Legal white knights

Lawyers have played important roles in several stanzas of Australian tobacco control over the last 35 years. They have assisted in drafting laws and regulations, advising governments on potential legal risks and, especially in the case of Peter Gordon from Victoria, have run cases for individuals who were seeking redress for harms. But plain packaging acted like a clarion call to a phalanx of academic legal experts who produced a small tsunami of legal scholarship on the many domestic and international issues arising from the legislation. These included Greg Craven, Mark Davison, Tom Faunce, Jonathan Liberman, Benn McGrady, Andrew Mitchell, Mathew Rimmer, Don Rothwell and Tania Voon. Most of these lawyers contributed to a large volume of both scholarly and journalistic writing, and several were often heard in radio commentary. An edited book of legal papers was published. (36) Several of them worked closely with the government at different stages of the saga.

It is also critical to acknowledge the vital role of the Australian government’s lawyers who provided legal oversight at all stages of the legislation and its regulations, and of the successful defence of the bill in the High Court (see Chapter 6). Their work is continuing in international forums.

Commonwealth public servants

Everyone with even the slightest engagement in the passage of the bill through to law appreciated the extent and sheer quality of the expertise available in the health department and in the solicitor general’s office in Canberra. These were beyond consummate public servants who rose magnificently to meet the extraordinary range of challenges that were their responsibilities in the passage of the bill. They provided detailed input to the development of the regulations preparing the government’s defence for the High Court case, they weathered the carpet-bombing freedom of information requests from the industry (see pp107), and they collated and summarised public submissions. They also handled numerous public enquiries and much correspondence, and provided close collaboration with other government agencies on a range of issues pertinent to the legislation, and on the conduct and handling of targeted and public consultation on the legislation and the regulations.

Angela Pratt from Roxon’s office was effusive about the role played by staff in the Department of Health and Ageing:

The health department, Jane [Halton], Simon Cotterell, there are a couple of different deputy secretaries that oversaw it at different stages of the process, were all magnificent. Really seriously magnificent. The detailed work involved in the legislative drafting was really difficult, complex work. If we had had a lesser team of people on that job, the kind of risk for problems in the legislation would have been very high. But the health department team were absolutely magnificent.

Very fittingly, the department was awarded the American Cancer Society’s Luther L Terry Award for outstanding leadership by a government ministry at the 2012 World Conference on Tobacco or Health, held in Singapore.

Public health experts and advocates

In addition to the lawyers mentioned above, Professor Mike Daube (Curtin University and chair of the Australian Council on Smoking and Health in Western Australia), Anne Jones and Stafford Sanders from ASH (Action on Smoking and Health), Cancer Council Australia and Victoria staff Professor Ian Olver, Paul Grogan and Fiona Sharkie and ourselves were the most frequent voices being interviewed, calling radio stations and writing opinion pieces and blogs over the four-year period since the April 2010 decision to proceed was announced.

Mike Daube played a pivotal quarterback role in plain packaging from the time of his chairing the National Preventative Health Task Force’s tobacco committee. Vastly experienced in both senior levels of government (he spent time as director general of health in Western Australia) and in advocacy dating from his time as inaugural director of ASH UK in the 1970s, Mike was in on every important conference call. He and I would speak often several times a day, whether to share information, review an incident or plan a line of attack. Most important of all, Mike was the main go-to person for the minister’s office.

Angela Pratt:

It was absolutely helpful to the government and the fact that all of you guys were incredibly well organised. You know, Mike Daube would ring me and say we’ve got a new opinion poll; when would be a good time to release it? I’d sort of say, well, don’t do it on Tuesday because something else is happening on Tuesday and it will get lost. But if you could do it on Thursday week that would actually be great because on Friday we’re planning to do X, Y or Z. So there was this very strong sense that we were working very closely together in support of a mutual goal.

I knew that if I talked to Mike the message would get out. It was just this great sense of there being a very well organised group of NGOs and academics in support. No single thing is decisive, but it all kind of builds into a campaign.

Mike travelled from Perth to Australia’s east coast so much that we all joked that he must have had not a platinum frequent flyer card, but a black diamond one. We referred to him as ‘Midnight Mike’ for his indefatigable willingness to give live interviews seemingly around the clock nationally and internationally. He is a consummate media performer whose instincts on how to best respond to the latest tactic from the industry are remarkable.

Non-government agencies

Australia’s network of health and medical NGOs all sang from the same song sheet on plain packaging. The Cancer Council Australia and the Heart Foundation both employed in-house lobbyists (Paul Grogan and Rohan Greenland) who both gave high priority to supporting the bill throughout its course. Both of these organisations had for years jointly funded ASH, and tobacco control for them was core business.

ASH in turn provided a large amount of media commentary on the issue and orchestrated a coalition of smaller NGOs to contact MPs at strategically important times to show their support. Stafford Sanders, who worked at ASH for 10 years, told me: ‘What most MPs would have experienced was a flood of letters and calls from small NGOs, parent groups, local health professionals and other influential local figures supporting plain packs.’

The Australian Medical Association is widely regarded as having a more natural affinity with politically conservative parties. They were at loggerheads with Roxon and the Labor government on a range of proposed reforms (including nurse practitioner and midwife reforms, Medicare Locals, hospital funding and various Medicare rebate changes) but, to their great credit, were resolute supporters of plain packaging. They issued many press releases, were often heard providing commentary, and were known to have urged the Opposition to support the bill.

Other health organisations, in particular the Public Health Association of Australia and its CEO Michael Moore, also made substantial contributions as part of the lobbying team.

News media

With a few exceptions (particularly News Corp newspapers), Australia’s news media reported the saga of plain packaging in overwhelmingly positive ways. I had no hostile interviews across the entire period, but recall a good many openly negative, and often scathing, comments about the tobacco industry’s response from journalists, producers and camera and sound operators before, during and after interviews. Tobacco control has almost attained the status of a no-brainer issue for most in the news media. Like immunisation, it has long evolved into a story that does not need ‘two sides’ in its telling. (260)

Angela Pratt shared this view:

I think by and large the media were supportive, and I think that just goes to show how discredited the industry has become, that basically anything the industry said, they kind of scoffed at. Ridiculed is too strong a word, though in some cases they did because some of the things that the industry said were ridiculous. I don’t remember it being something that we felt like the media were part of the enemy, whereas other issues we absolutely felt like we were in the trenches against the media.

Columnists

A large number of opinion pieces on plain packaging were published in Australian-based newspapers and online news outlet and blogs.

Table 5.3: Opinion page and blog authors on plain packaging, 2008–14

| Supportive | Opposed |

|---|---|

|

David Campbell (261) Mike Carlton (226) Simon Chapman (262–279) Simon Chapman and Becky Freeman (280, 281) Mike Daube (282, 283) Mark Davison (284–287) Matthew Day (288) Simon Evans (289) Thomas Faunce (290) Becky Freeman (291) Mia Friedman (292) Ross Gittins (169, 293) Steven Greenland (294) Nathan Grills (295) Paul Grogan (296) Paul Harrison (297) David Hill (298) Jessica Irvine (299) Stephen Leeder (300) Ross MacKenzie (301) Colin McLeod (302) Rob Moodie (303) Ben O’Shea (304) Reema Rattan (305) Matthew Rimmer (306–309) Don Rothwell (310) Craig Seitam (234) Kyla Tienhaara (311) Julian Vieceli (312) Tania Voon (313) |

Leo Bajzert (advertising worker) (314) Chris Berg (IPA) (315) Julie Novak (IPA) (316) Tim Wilson (IPA) (317) |

These were overwhelmingly positive to plain packaging, and often scathing of the tobacco industry and congratulatory of the government. Table 5.3 lists authors of all those that we have been able to locate, written by both professional journalists and guest authors.

Cartoonists and satirists

Australian cartoonists, satirists and current affairs panel programs feasted on plain packaging, rarely with anything but biting support. This site features 18 such cartoons, nearly all of which rained down vicious blows on Big Tobacco’s arguments: http://atodblog.com/2012/11/20/editorial-cartoonists-did-their-duty-in-australias-tobacco-war/

‘Everyone hates them’

For many years, tobacco companies in Australia have suffered from public perceptions that they are not to be trusted, that they are corporate pied pipers with intense interests in children, rapacious corporate leviathans who put profit before all else, and are indifferent to the suffering that their products cause (260). Two surveys of Australians’ attitudes to the tobacco industry put it very plainly (318, 319). One of these found that:

80% of respondents and 74% of smokers thought tobacco companies mostly did not or never told the truth about smoking and health, children and smoking and addictiveness of tobacco. With regard to perceived standards of honesty and ethics, tobacco company executives were rated the lowest of all professional groups, with 74% of respondents judging them to have low or very low standards. (319)

Philip Morris’ own commissioned market research from 1993 had told them the same thing:

Philip Morris is almost universally known among the public and opinion leaders . . . The company’s overall favourability ratings average in the low 30s on a 100-point scale places it in the company of two other tobacco companies – W.D. & H.O. Wills and Rothmans – well below the normal mid-50s to mid-60s typically found for most companies. These ratings for the company are very similar to those found among comparable audiences in the United States. (320)

Eighteen years later, things had, if anything, sunk even lower for Big Tobacco. In 2011, the Reputation Institute published results of a global survey of 85,000 respondents (including an Australian sample of 5,611) conducted by the Reputation Institute and AMR Australia in January and February 2011. It rated all major industries in 25 categories for reputation. The top categories were consumer products (73.8), electrical and electronics (73.2) and computers (70.3). By far the worst performing category was tobacco, which scored only 50.1, well behind the next lowest category (utilities with 59).

A Google search with the string ‘just like the tobacco industry’ returns many thousands of examples of how the tobacco industry has become an index case or benchmark in everyday talk for all manner of malfeasance in corporate conduct. It has set the bottom feeder standard on trust, ethics and grubby conduct. No other industry is subject to widespread policies of academic institutions refusing to allow their staff or students to accept tobacco industry research grants or scholarships. Our own university (Sydney) has long refused to allow tobacco companies onto the campus to run job opportunity stalls at its annual student employment fair. It is the only industry thus refused.

Politicians are highly sensitive about who they are seen to be associating with. Political scandals involving associations with sex workers, criminals and corrupt land developers are common around the world, but in an increasing number of countries, being seen to be cosy with tobacco companies has become a hallmark of political poor judgement. As the CEO of the American Cancer Society, John Seffrin, has put it: ‘Politicians don’t like to stand next to a pariah in the next photo opportunity.’

Roxon was similarly emphatic that the industry’s appalling reputation as corporate pariahs (260) was important to the decision to run with plain packaging:

When the taskforce report came, marshalling all the evidence for various measures including plain packaging, this was when I really started to give it serious thought. I can remember one of my advisors, my personal staff, not the bureaucrats, saying to me well, this is just a ‘no-brainer’. Meaning, it might be new and bold, but it hit a political sweet spot too – you have good evidence, you have doctors and researchers on side, you’re trying to protect kids and the only one lining up against you is the tobacco industry. With a sceptical media and pretty well informed public, fighting such a discredited industry was not as dangerous as people thought.

Angela Pratt told us:

Basically my view about it at the time and since has been it was a good old-fashioned political fight between good and evil. When you’re fighting with the AMA [Australian Medical Association] about something, it’s never that clear cut. It’s not really ever that great to be in a big fight with the doctors. Even if it’s worthy and justified and they’re being bastards, as a political strategy it’s never really that great. I would almost say that the prospect of a fight with Big Tobacco was something that people relished the thought of, rather than shied away from it. That’s not the reason that we did it, but a fight with the tobacco industry was not something that scared people off.

Pratt said that Rudd shared this view:

I think it’s probably fair to say that he didn’t mind the idea of a big fight with the tobacco industry. You know, in politics it’s not bad to have a fight. I mean, we didn’t do it because we wanted a fight. We did it because we thought it was important and would make a difference. But the prospect of the fight with the tobacco industry wasn’t something that put people off, particularly.

Like millions of Australians, Rudd had lived through several decades where tobacco control was rarely absent from the news media (321, 322) for more than a week. In this time there had been years-long advocacy campaigns to get rid of all tobacco advertising and sporting and cultural sponsorship, to upgrade pack warnings, to introduce smokefree indoor air on public transport, and in workplaces, restaurants and bars. (323) There had been the train wreck of revelations about the tobacco industry’s duplicity on health and addiction and designs on children when millions of their internal documents were made public in the late 1990s. There had been large-scale public awareness campaigns on the risks of smoking. And through all this, we saw virtually continual declines in smoking, growing antipathy toward the tobacco industry and support for governments to do more to reduce smoking, particularly among young people.

Nicola Roxon

No analysis of why Australia acted on plain packs could fail to place Nicola Roxon at centre stage. Across 35 years I have encountered many federal and state ministers responsible for aspects of health, and worked with several closely. Barry Hodge (Western Australia 1983–86), John Cornwall (South Australia 1982–88), David White (Victoria 1985–89), Michael Wooldridge (Federal 1996–2001), Frank Sartor (New South Wales 2003–07 and 2009–11) and Verity Firth (New South Wales 2007–08) were all ministers who implemented major tobacco control reforms while in power. Each of these people painted their reforms on a state or national canvas, as did Roxon. But Roxon’s contribution to tobacco control history looms as one of the most important initiatives with global ramifications ever taken. If, as expected, dominoes fall around the world over the next decade, her contribution will have been monumental.

Roxon was a spectacularly good media performer. Those of us who had several decades of experience in advocating and debating for policy reform in the news media have had many hundreds, if not thousands of opportunities to rehearse particular framings, sound bites and lines of arguments. On a big news day in tobacco control, it is not uncommon to do 10 or more interviews for different media outlets, all about the same issue. You quickly get a sense of how journalists see an issue, and about which questions they see as central to a debate. You often get these questions early and develop a sense about how you have handled a question: which parts if an interview were strongest and which needed work. Subsequent interviews then allow you to push forward responses that you have used earlier to good effect. In this way, interviews throughout the day tend to get more polished. It’s a common experience to feel as thought you have nailed an interview with a turn of phrase, an analogy, a killer fact or statistic.

Nicola Roxon gave many interviews on plain packs over 2010–12. Seasoned advocates for tobacco control were in awe of her abilities to calmly and firmly explain the policy, to defend every aspect of it from attack and to go to the heart of the case for strong tobacco control. For example, on releasing the report that recommended plain packs, Roxon put the importance of firm action on tobacco by simply saying: ‘We are killing people by not acting’. (65) This stunningly direct, simple, clear-sighted and courageous statement of moral principle was one of several powerful sound bites she was to use in the months ahead. Another was her compelling observation that she had ‘never met a smoker who hoped their children would grow up to become a smoker.’ There was just no comeback on that point.

Angela Pratt told me that working with Roxon was an experience she never expected to better.

Nicola was an outstanding minister. She was outstanding in everything that she did. She was always across her brief. Whenever she did an interview, she was extremely well prepared. She knew the ins and outs of the arguments, and she wouldn’t agree to do the interview until she knew that she could be. I guess with this issue, she had an amplified sense of the importance of getting it right because she knew that every word uttered on television could be something that the industry would use in their legal case against us if she said slightly the wrong thing.

She really believed in plain packs. She’s a formidable person. She’s incredibly smart. She’s incredibly articulate. She has an incredible ability to go right to the point of an issue. She was very clear from the beginning about the strategy for defending this, that it needed to be placed in the context of a long history of tobacco control policy so that we could argue that it was the next logical step.

She was very clear about the limits of what you could say about the evidence base: while there was no proof that it would work – there never is when you do something for the first time – but there was evidence that it most likely would work. She was very clear about the fact that we didn’t expect that it would have a major impact on long-term smokers. Rather, it was all about preventing young people from starting up smoking. So it was for all those reasons that she was a formidable advocate for the policy, and why it was such a delight to work for her during that period.

The Coalition, the Greens and the crossbenchers

After the August 2011 election, the Labor Party was returned to power in a hung parliament requiring the support of at least three of the five crossbench members of the House of Representatives to pass its legislation, such as the plain packaging bill. In the Senate, it was assured of safe passage because the Greens Party was rock solid in its support for the bill, and in voting with the government, guaranteed that it would pass. Cross-party support was important, not only for the safe passage of the legislation, but to ensure continuity of support in the event of a change of government. It was also considered important to show the world that plain packaging was unanimously supported in Australia, historically a two-party nation, particularly at a time of minority government.

Health groups such as the Cancer Council and the Heart Foundation enjoy excellent relations with all political parties, and it soon became apparent that the three needed crossbench votes were assured with the support of the sole Greens representative, Adam Bandt, and two NSW independents Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott. Tasmanian independent Andrew Wilkie was also emphatically supportive of the legislation. None of these three, who had often voted in a bloc on other legislative issues, needed any convincing. Maverick Queensland independent MP Bob Katter described the policy as ‘rampant wowserism’ (324) and would have never voted for it.

But the tobacco control community knew how important it was to make sure that the bill gained the support of the Opposition. This would better ensure its preservation and consolidation down the track, should they come to power.

As explained earlier (pp97), the conservative Liberal/National Coalition Opposition was by no means pro-smoking. It had introduced and sustained important platforms of tobacco control when previously in government. But in Opposition, the task of trying to find fault with most government activity is standard. The Abbott-led Opposition took this duty very seriously and developed a reputation for being extremely negative about almost everything the Labor government supported. Many expected that the Opposition would not be any different when it came to plain packaging.

The Coalition had a good number of members – including Abbott himself – who were almost genetically opposed to ‘unnecessary’ regulation of business and human behaviour. After the government had announced its intentions on plain packaging, several equivocated and publicly expressed reservations or declined to comment. Shadow health minister Peter Dutton said in June 2009: ‘In my books, in the current debate, providing a ban to packaging and to branding on packaging is a bridge too far.’ Pushed in May 2010 by prime minister Julia Gillard to say yes or no to plain packaging, Abbott eventually said: ‘If it shuts you up for a second, yes Julia.’ (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pjR9JbThk1I) In May 2011, on the day BATA launched its campaign with a press conference, Abbott said: ‘My anxiety with this is that it might end up being counterproductive in practice.’

Fragments of intelligence from Opposition members and occasionally tobacco industry staff were gathered about the likelihood of support for the legislation. These painted a mixed picture. For example, a tobacco control colleague had been on holiday in Fiji resort in 2010 and got talking to some Australian businessmen. They turned out to be staff from an Australian tobacco company and some retailers who were being rewarded for achieving high tobacco sales levels. Without disclosing her interest, the colleague asked whether they were worried about the impact of plain packs. They brushed it aside and said that their management had assured them that Tony Abbott would drop the policy on gaining power.

But this may have been mere company bravado, because a leaked fax from Philip Morris’s head of corporate affairs to a PR agency in May 2010 (see pp15) noted: ‘Please note that contrary to the proposal, the Coalition’s “resolve” is not “strong”. It is at best neutral.’ This resolve referred to the industry’s hopes that the Opposition would oppose the legislation.

However, there were at least four Coalition members (Liberals Dr Mal Washer, Ken Wyatt and Alex Somlyay, and West Australian National Tony Crook) who expressed support for the policy. (324) Rumours spread that some of these may have been willing to cross the floor and vote with the government if a division had been necessary. Of these, Mal Washer was the most forthcoming about his intentions. A highly respected Perth general practitioner, Washer was a popular and trusted figure across all sides of politics, often acting as a doctor to politicians while in Canberra for parliamentary sittings. He was not someone easily ignored.

When interviewed by The Age on 22 May 2011, just nine days before his party would decide that it would not oppose the bill, Washer was asked about industry claims about increases in smuggled products. His words were blunt:

All this talk of chop chop [loose, illegal tobacco] and crime gangs sounds like bullshit to me. The tobacco industry is jumping up and down because they’re worried about their businesses. I support these reforms unequivocally and whatever my party decides to do, I don’t give a shit. (325)

On 26 May 2011, the Cancer Council held its annual Australia’s Biggest Morning Tea fundraiser event in parliament house. Opposition leader Tony Abbott attended and told those present: ‘We all should do what we can to fight cancer.’ (326). Lung cancer is Australia’s leading cause of cancer death, with 8410 victims in 2012, more than double the cancer causing the next most deaths (colorectal with 3950), prostate (3294) and breast (2940).

The next day Michelle Grattan, perhaps the most senior member of the Canberra press gallery who had attended the event, wrote an opinion piece about the Opposition’s lack of leadership on plain packs. She wrote:

There are issues that should be elevated above politics, and trying to find ways to reduce the killer habit of smoking is one of them. So it is particularly disappointing that Tony Abbott, a former health minister, is dithering on the Opposition’s attitude to government legislation for the plain packaging of cigarettes. The case for this measure is overwhelming . . .

Abbott has to contend with serious divisions within his ranks on the packaging issue . . . But Abbott will have to deal with the differences within the Opposition eventually, and he might as well do it sooner rather than later. The packaging legislation appears set to get through the House of Representative even if the Coalition opposes it – thanks to the crossbench and the Liberal dissidents’ will to cross the floor. Politically it would look bad for Abbott to appear doubly impotent; unable to stop the legislation and unable to keep his own troops in line.

2011 World No Tobacco Day

On 31 May 2011 (World No Tobacco Day), Mike Daube and I, together with the Public Health Association of Australia, arranged a special event in Canberra to thank Nicola Roxon and the Labor government for what it was doing in tobacco control, particularly with plain packaging. This was the biggest policy advance any of us had ever experienced, and we wanted to bring together all who had played big roles in both the years leading up to it, and in all the defence of the bill described in this book.

We had earlier nominated Roxon to the World Health Organization to receive a WHO World No Tobacco Day medal. We had also arranged for her to receive the Nigel Gray Award, named in honour of the long-time head of the Cancer Council Victoria (1968–1995), widely regarded as a global ‘godfather’ of tobacco control.

She was presented with both awards that day at parliament house, where the WHO’s regional director for the Western Pacific, Dr Shin Young-soo, flew down from Manila to make the presentation. Nigel Gray was there to present the award under his name. (She was later also awarded the Public Health Association’s Sidney Sax Medal).

Mike and I had drawn up a list of those around Australia who had made outstanding contributions to tobacco control since the 1970s. About 50 were able to attend, including politicians from all sides, senior health department bureaucrats, long-time researchers, heads of leading NGOs, John Bevins (the advertising writer who had created the ‘Sponge’ ad (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UbwsET7_6kQ)) and many others, and Dr Arthur Chesterfield-Evans, a leading figure in the BUGA UP anti-tobacco billboard graffiti movement from the late 1970s and early 1980s. (327)

The award ceremony took place at 11am. Unbeknown to most of those attending, the Opposition was also meeting at the same time in the parliament building, and one of its agenda items was plain packaging. At noon, Rohan Greenland and Lyn Roberts from the Heart Foundation met with Andrew Robb as part of their ongoing engagement with the Coalition on the issue. Robb came straight from the party room and told the two that the Liberals had decided not to oppose the plain packs legislation, and that they were the first to know. Greenland told me: ‘He was very happy to break the news to us.’

Angela Pratt saw the timing of announcement as no mere serendipity:

We, in combination with you and all your colleagues, had sort of set out to create a real sense of building pressure on the Opposition in the lead-up to and on that day. So I remember all of those things coming together and culminating on that day successfully, because that was the day the Liberal Party announced that they wouldn’t oppose the legislation.

I asked Nicola Roxon and Angela Pratt to comment on the Opposition’s behaviour over the bill. Both took the stance that the Coalition were never comfortable with the issue, but were clearly able to read the very negative political realities of being seen to effectively side with Big Tobacco and having principled party members being seen to cross the floor of parliament.

Roxon said:

My personal view is they got embarrassed into it. Ultimately Opposition support came because the tobacco industry had no credit in Australia, because of their past behaviour. Once the Liberals could see that we were sticking to our guns – I think they were waiting to see if we buckled or changed direction – but because we weren’t, they saw that they were going to be very much on the wrong side of public opinion.

Pratt’s view was similar. She said:

[Mal Washer] was prepared to cross the floor, if necessary. So really I think Abbott and the political leadership of the Liberal Party made a judgement that the risk of disunity – with Washer crossing the floor – was worse than any political downside of their supporting the legislation. So they made a judgement that supporting the legislation was the lesser of two evils. It was a pragmatic political judgement to avoid an ugly show of disunity in the floor of the House of Representatives.

Angela Pratt’s view was that Washer’s position was made all the easier because of the antics of the tobacco industry:

What gave strength to Mal Washer’s hand was this sense that the tobacco industry’s campaign was actually just really quite abhorrent. It was over the top. They were being seen to be bullying the government. And it’s the tobacco industry!

So I have always had the view that it was the extremity of the industry’s campaign – the fact that they went so hard, so extreme, so over the top – that hurt them. I think it became clear to the Liberals that it was politically completely unpalatable for them to be on the same side as all of that.

I absolutely think that it was not Abbott’s or Dutton’s instinct to support it, but it became a political liability for them not to be supporting it. Because by not supporting, they were on the same team as the tobacco industry, which was a kind of pretty unpalatable prospect.

Pratt also acknowledged that:

Graphic health warnings were introduced under Abbott, so there is sort of shared sense of pride in Australia’s tobacco control history. It’s a shared sense because both parties have some ownership of different parts of it. I still think that the Liberals would have preferred not to support the plain packaging legislation. I have never seen any evidence of them having become enthusiastic supporters of the policy. So while broadly I would say tobacco control is a bipartisan issue, I’m not sure that I would say plain packaging is a bipartisan issue.

The Adelaide Advertiser’s headline the next day was: ‘Libs yield on smokes packaging’ (our emphasis). The article stated:

There were also fears that Mr Abbott’s ‘brand’ could be damaged, given the Government’s initiative had been unanimously supported by health groups and normally conservative lobbies, including the Australian Medical Association. (328)

On the evening of the day the awards were presented and the Coalition made its decision to not oppose the bill, the Public Health Association hosted a dinner in parliament house for Nicola Roxon, Nigel Gray and the 50 or so tobacco control stalwarts who had been there for the ceremony. Roxon’s very proud mother came along, as did Mal Washer and the Greens Senator Rachel Siewert.

I sing in a Sydney rock covers band. Our lead guitarist is Paul Grogan, the Cancer Council Australia’s lobbyist. We had put an impromptu version of a new take on the 1960s Shangri-Las’ hit Leader of the Pack on YouTube (see http://tiny.cc/8qurox), recorded after dinner one night at Paul’s house. Paul and I sang the song that night in tribute to Roxon. Everyone in the room roared the chorus lines.

On the morning that the High Court case began in Canberra (17 April 2012), Tony Abbott went out of his way to make his support even clearer. He said: ‘I think this is an important health measure. It’s important to get smoking rates down further. We didn’t oppose the legislation in the Parliament and I hope it withstands the High Court’s scrutiny.’ (329) It is noteworthy that after the 2013 election, the new Coalition government maintained strong bipartisan support for tobacco control, including plain packaging, regular excise increases and mass media campaigns.

1 See details of Australian smoke free environments legislation here http://tiny.cc/ydurox

3 It is common for politicians to acknowledge the presence in the public parliamentary gallery of people who are affected by new legislation or who have played a major role in its development. In speaking to the bill, Nicola Roxon noted ‘Can I particularly say that it gives me great pleasure that the parliament has been able to accommodate Mike Daube on his 63rd birthday. I hope that this is a good birthday present for him.’