4

Tobacco industry arguments, strategies and tactics

In this chapter, we will review the main arguments, strategies and tactics used by the tobacco industry, its acolytes and messengers to attack plain packaging. At the end of the chapter, we will also describe some of the initiatives taken by advocates of plain packaging to counteract industry propaganda. We will start with the most prominent and common arguments and then move through to those used less often. Most of these were also used in the blogosphere by citizens and anonymous trolls, some of whom may well have been tobacco industry staff. (164)

It won’t work, so don’t do it!

Let us start with the most bizarre argument of all those used to oppose plain packs. This was the ‘poacher turned gamekeeper’ spectacle of those in the tobacco industry telling the Australian and later the Irish, British and New Zealand governments that they knew that plain packs would do nothing to decrease tobacco sales in children or adults, and that therefore the government should abandon the policy.

This was always going to be a highly fraught strategy for the industry. It is axiomatic that the tobacco industry wants as many people to smoke as much as possible. That is what all its employees understand as their collective key performance indicator as they arrive at work each day and what shareholders expect from their company. Their targets include those who smoke now, those who used to smoke and who might be tempted back into it (165), and those who have not yet started but who might be persuaded to start. This last group is overwhelmingly young people, including those under 18 years of age who are legally unable to buy tobacco products, but who of course often do.

It is equally axiomatic that the future of the tobacco industry depends on new generations starting to use its products. So for all the public statements from the industry that children should not smoke, and its denials that it ever tries to attract children via its marketing and promotions, its own internal documents contain many examples going back many decades about exactly the opposite. (91, 93) The tobacco industry is intensely interested in maximising the probabilities that young people will experiment with cigarettes, become dependent on nicotine and become daily, hopefully heavy smokers for many years.

Over the years, tobacco retailers have stood side-by-side with the manufacturers in opposing any measure proposed by governments or public health advocates that threatened to reduce their sales. Tobacco retailers similarly do not open up their shops each day hoping that sales will fall. Like any retailer for any product, they routinely offer price discounts knowing that this will increase sales. And like purveyors of any and all consumer goods, they appreciate that elegant, striking, eye-catching, desirable market-researched packaging helps promote the attractions of their products more than dull packaging incorporating hideous graphic warnings. On the eve of the release of the Chantler report on plain packaging, commissioned by the British government, Simon Clark from the tobacco industry-funded FOREST and ‘Hands off our packs’ campaign obligingly put the power of branded tobacco packaging this way: ‘It’s like showing them a picture of a Lamborghini and a beaten-up Ford Escort and saying “Which one do you prefer?”’ (166)

Plain packaging poses two massive threats to the tobacco industry. First, it pulls the heart out of branding, the very core of tobacco marketing. As we saw in Chapter 3, branding invests tobacco products with rich signification and personal badging that is bound up in consumers being attracted to smoking and selecting brands, displaying them many times a day and remaining loyal to those brands. Plain packaging eviscerates the ability of tobacco companies to present packaging intended to make these products more desirable – and making smoking less appealing is a major goal of tobacco control.

Second, both tobacco manufacturers and retailers earn more from sales of some brands than others. Plain packaging poses a major threat to the profitability of premium, more profitable brands. Appearing identical to all other brands, apart from the permitted brand and variation names on the packs, many smokers reason: ‘Why pay a lot more for a premium brand that looks exactly the same as a budget brand?’. These expensive brands are likely to taste little different to less expensive brands anyway (95). Plain packaging threatens to gut a major component of profitability of the tobacco industry as it dawns on smokers that they were paying more for a fancy packet that now looks identical to all others, except for the brand name.

In itself, this second effect is not of any primary interest to tobacco control because expensive cigarettes are no less deadly than cheaper cigarettes. It is just collateral damage to the tobacco industry caused by the policy objective of making all tobacco products less appealing. This is entirely the industry’s problem, but one that is irrelevant to the prevention of diseases caused by smoking, and therefore to the public health goals of plain packaging.

On this, the Chantler report (76) makes this critical observation.

The intent of standardised packaging is indeed to remove appealing brand differentiation. Standardised packaging is aimed at encouraging smokers to see all cigarettes as equally harmful and unappealing, rather than to identify with particular brands and associate them with positive qualities such as glamour, slimness or sophistication.

So when we hear anyone from the tobacco industry intoning earnestly that they believe that plain packaging ‘won’t work’, and explaining that it would be sensible for government to abandon it, it is always sensible to decode such statements through a commercial reality checker. What possible motivation would anyone profiting from selling tobacco have to urge governments to not pursue strategies that supposedly would not impact on sales? The idea that anyone in the tobacco industry might seriously think that their advice on best practice in tobacco control would be given even a nanosecond’s credibility is more than comical. But let’s be generous for a moment and reflect that on hearing such advice, some people might think that those in the tobacco industry actually might know pretty well what might impact on smokers. ‘They research smokers. Retailers talk to them every day. They might actually know.’

Yes, they certainly do know. It is instructive to watch delivery trucks dropping off tobacco supplies to retailers. These supplies have often been electronically ordered by retailers and the drivers electronically record every carton delivered. In this way, the tobacco manufacturers have instant access to data on every brand sold to every retailer in every suburb on every day. They can then map this data against any variable they choose: season, month, day of the week, macro-economic indicators, suburban demographic indicators, proximity of shops to schools or factories, the introduction of new brands and variants, of changes in pack design, price changes, tax rises, presence or absence of anti-smoking campaigns, and the introduction of new laws or regulations on smoking. They also know how long such changes to demand last.

Armed with such information, their statements about a policy not going to ‘work’ or having no serious impact, take on a different perspective. If a policy like plain packaging was not going to negatively impact on sales, why would they waste any breath, let alone many millions of dollars, in opposing it? As Hamlet’s mother Gertrude might have put it: ‘The [tobacco industry] doth protest too much, methinks.’ The industry’s frequent, insistent attempts to convince us that plain packaging is a silly idea ironically helps convince us that the exact opposite must be true.

It’s never been done before

Equally bizarrely, the industry thought it was onto a winning argument by repeatedly emphasising that no nation had ever introduced plain packaging. They doubtless reasoned that this argument rested on several subtexts that would convey to the public that such a proposal was therefore reckless, adventurous, foolhardy and naïve. This argument implied that it was obvious that no other nation had introduced plain packs because all other nations – unlike the cavalier Australian government – had thought it through properly. If something has never been done before, it’s always because it’s been considered and rejected for good reason.

And because no country had ever introduced such legislation, another taunt therefore became available: there was of course no evidence to be found anywhere that plain packaging would achieve what it was meant to achieve. This evidence-free zone in turn allowed the industry to hitch a ride on the evidence-based policy mantra that has swept through governments over the last 15 or so years. How could the government possibly promote a policy for which there was no evidence? They were onto a winner, surely?

But in all the excitement, the industry had painted itself into the corner of championing opposition to innovation. It sought to make a virtue out of Australia only ever marching behind other countries. In a political science satire Microcosmographia Academica written in 1908, FM Cornford advised aspiring politicians that ‘every public action which is not customary either is wrong, or if it is right it is a dangerous precedent. It follows that nothing should ever be done for the first time.’ (167) This was the tobacco industry’s mentality in a nutshell.

In public health and medicine, as in every facet of life, there are many examples of things having being done for the first time. Important examples from public health history include vaccination, countless new drugs, the introduction of seat belts in cars (which was first legislated in Victoria, Australia in 1970) and a huge range of product innovations. The British Medical Journal once published a tongue-in-cheek systematic review that pointed out that there were no randomised controlled trials that parachutes would save the lives of someone jumping from a plane before (or after) the first time someone jumped using a parachute. (168)

In tobacco control, there have also been many ‘firsts’ – policies adopted in one country before any other jurisdiction had done so. These included the first introduction of advertising bans; smokefree workplaces, restaurants and bars; strong public education (mass media) campaigns; health-based tax increases; the first pack warnings; and the first graphic pack warnings. Each of these vanguard innovations has now been adopted in many nations as tobacco control proliferates globally through the stimulus of the WHO’s FCTC (75) and the strong support of international and national medical and health groups.

Senior Sydney Morning Herald journalist Ross Gittins was one who lampooned this argument:

Plain packaging of cigarettes . . . has never been adopted anywhere in the world. Great argument: it has not been done before, therefore you shouldn’t do it. This is the poor little stupid Australia argument. We should always merely follow the lead of other countries because we’re not smart enough to dream up anything good ourselves. Its logic is foolproof: if it has never been done before there’s no evidence it works, and if we never try it there never will be. But if the idea’s so unlikely to work, why are the global giants fighting so hard to stop it being tried? (169)

There’s no evidence it will work

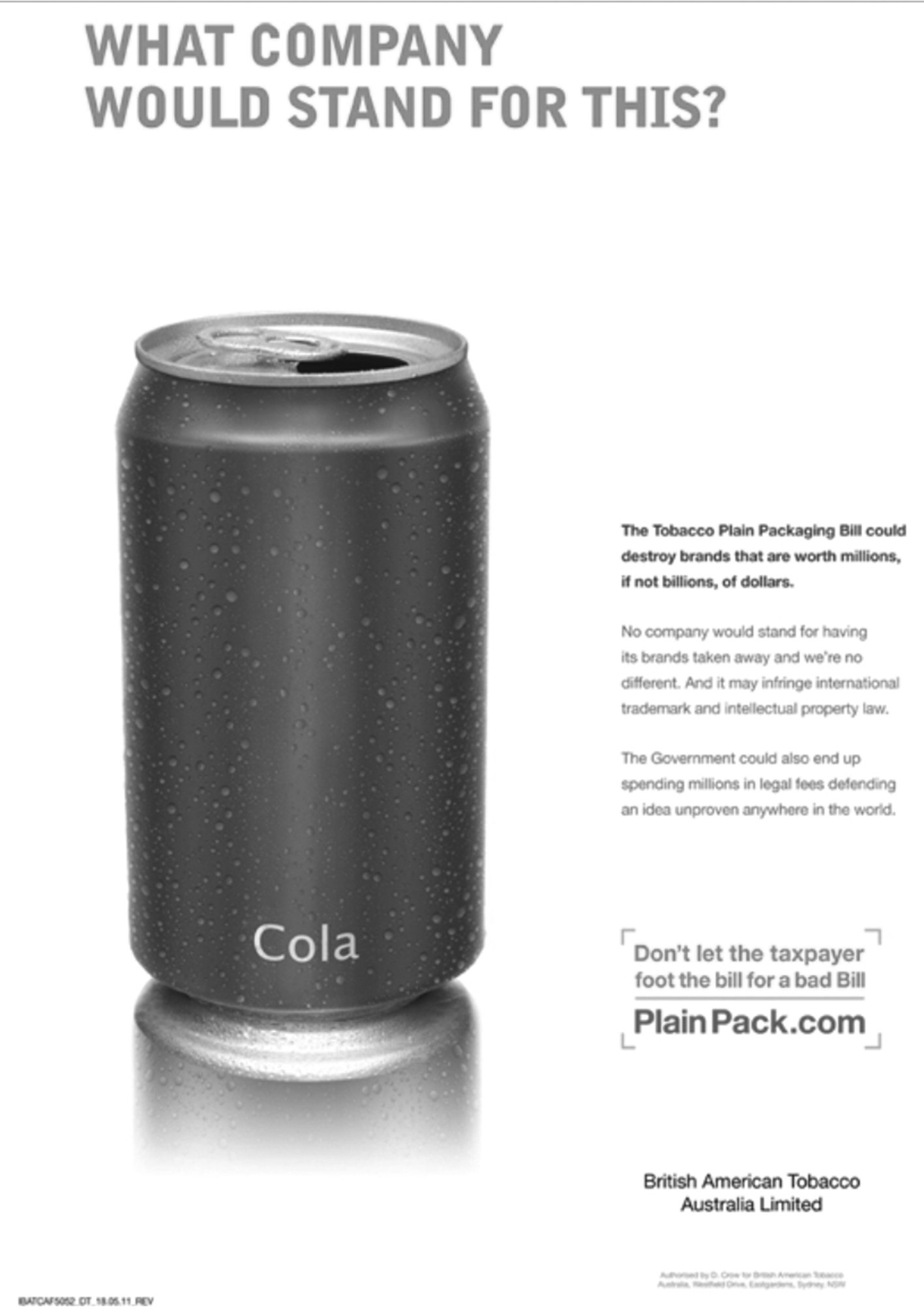

The fraternal twin of the ‘it’s never been done before’ argument is the even hairier-chested ‘there’s no evidence’. BATA ran advertising showing an empty filing cabinet to emphasise this point (Figure 4.1)

In fact, there was a good deal of published evidence. This was gathered together under the one cover in a review by Quit Victoria and the Cancer Council Victoria in August 2011 (170). Angela Pratt emphasised the importance of the assembling of this research:

the amassing of the evidence base. I mean, the number of times that was in all of our talking points. That was incredibly, incredibly important because it enabled Nicola to make the case publicly that this was something that had an evidence base.

As we saw in Chapter 3, before Australia introduced plain packaging, there was considerable experimental evidence that consistently demonstrated that young smokers and potential smokers rate fully branded packaging as being far more appealing across many dimensions of appeal compared with plain packaging. In these studies, subjects are typically presented with fully branded and mocked-up plain packaging and asked to rate them on a variety of attributes and characteristics.

Five reviews summarising this extensive body of evidence showing how packaging influences consumer attitudes, beliefs and behaviour are the Tobacco labelling and packaging toolkit (Canada, 2009) (171), Plain packaging of tobacco products: a review of the evidence (Australia, 2011) (170), Plain tobacco packaging: a systematic review (UK, 2012) (172), the Chantler review (England, 2014) (76) and Hammond’s review for the Irish government (2014) (163). The main conclusions of this body of research are that:

- packaging is an important element of advertising and promotion, and its value has increased as traditional forms of advertising and promotion have become restricted

- packaging promotes brand appeal – it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate this from the promotion of tobacco use or to exclude children and young adults from its effect

- the inclusion of brand names and other design embellishments are strongly associated with the level of appeal and perceived traits associated with branding such as sophistication

- plain packaging is less appealing for young people who may be thinking of trying smoking

- on-pack brand imagery distracts from the prominence of health warnings and reduces their impact

- package colours and imagery contribute to consumer misperceptions that certain brands are safer than others

- plain packs reduce the appeal of cigarettes by lessening both the attractiveness of the product and the social desirability of the users of the product

- innovative packaging shape, size, and opening create strong associations with level of appeal and perceived traits associated with branding

- tobacco in plain packs is perceived to be less satisfying, of lower quality, and potentially more harmful.

Exploiting public misunderstanding of ‘plain’ packs

In the years since plain packaging was announced by the Australian government, we have often had to pause in our explanations of the concept when people interrupt and say, ‘so, do you mean they are just . . . all plain? All white? Is there no health warning, for example?’ Opponents of plain packaging sought to exploit this understandable lack of public understanding of the words ‘plain packaging’ and tried to give the impression that plain packs would be plain white boxes with no markings at all. For example, BATA ran the advertisement in Figure 4.2 in Australian newspapers. It proposed that if plain packaging were to apply to cans of cola drinks, then the cans would be all the one colour and only have the word ‘cola’ on the front, thereby not allowing purchasers to know if they had been sold the particular brand of cola drink they wanted. In Britain, plain packaging has been often depicted in the press as in Figure 4.3 following.

Depicting plain packaging in these ways is highly misleading for two reasons. First, unlike the BATA advertisement which shows a drink can with the word ‘Cola’, Australian tobacco plain packaging carries the brand and variant names of each different brand. Packs do not just say ‘cigarettes’ as the BATA advertisement implies, and as BATA knew full well would not be the case. Second, as Figure 2.1 shows, Australian plain packs do not look anything like the BATA comparisons with hypothetical ‘plain’ cola cans: they have massive coloured health warnings on them.

In March 2014, Linda McAvan, Britain’s member of the European parliament for Yorkshire and The Humber, told the 6th European Conference on Tobacco or Health in Istanbul that tobacco industry lobbyists had been distributing plain white boxes like those in Figure 4.3 to members and staff of the European parliament. The mendacity of this exercise shows the tobacco industry today is little different to its decades of dishonest conduct we have witnessed repeatedly since the 1950s.

‘Plain packaging’ was the term initially used and that is now well understood in Australia.Plain packaging does not mean packaging without graphic health warnings. Other countries may wish to avoid potential confusion and could consider using terms such as ‘generic’ or ‘standardised’ packaging, which is the term used in the April 2014 Chantler review for the British government. (76)

It will be easier to make fake copies

This exploitation of the lack of understanding of ‘plain’ also played for the tobacco industry in proposing that plain packaging would create a paradise for counterfeiters. What could make life easier for counterfeiters than to reduce the challenges of counterfeiting sometimes complex packages by just requiring plain white boxes?

BAT’s website featured a video sent to many MPs in the UK and Australia. The high production video dramatised the line that retail display bans (now adopted by a growing number of nations), plain packs, tax increases and banning additives would all contribute to increased crime, terrorism and prostitution. The video had everything from a cheesy script, to a swarthy eastern European drug dealer stereotype, an innocent and clueless European Union bureaucrat and a shifty English bad guy (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lpFx7pLy2L0).

The entire premise of the message was that these control measures would be manna from heaven for organised crime: ‘Plain packs – easy for us to copy . . . no logos to match . . . easier to counterfeit . . . lots more profit,’ said a fingernail-removing Budapest crime boss from the back of a limo.

The truth, however, is that copying branded packs has never been a serious barrier to tobacco counterfeiters. On the streets of many low and middle-income nations, fake leading brands are openly sold through street vendors because of chaotic law enforcement and corruption. I once edited a research paper from Tehran showing that 21% of cigarettes are smuggled there. (173)

But that is not remotely the situation in Australia, nor in most OECD nations. Forecasts of massive black markets assume that smokers will be able to access these products with the ease that they today are able to buy cigarettes from every second shop.

As anyone who has travelled to nations where counterfeited consumer goods like watches, perfumes, clothing, books, DVDs, CDs, luggage and luxury pens are openly on sale, it is obvious that copying a cigarette pack is child’s play. It has long been the case that counterfeiters have been able to easily make extremely good, near-to-perfect copies of fully branded tobacco packs. Australia’s plain packaging would be no more or less easy for professional counterfeiters to copy than the fully branded packaging it replaced. It is a major misunderstanding to assume that challenges in copying packaging present a substantial barrier to professional counterfeiters. The tobacco companies know this, so for them it is nothing but the wilful attempt to promote a lie.

Former Scotland Yard chief inspector Will O’Reilly, now a regular ‘spokesman’ for Philip Morris, (174) emphasised another angle here, saying: ‘If . . . we cut criminals’ costs by giving them just one pack design to copy rather than 101, then it’s criminals that win.’ (175) This catchy sound bite rests on the falsehood that counterfeiters see their task as making faithful copies of every brand and brand variant that is available for sale in a licit market. Sometimes there are hundreds of legal brands and variants on sale, however counterfeiters have no interest in going to the trouble of copying brands with tiny market share. Few smokers want these brands when they are sold openly, so why would they suddenly want them, when popular brands are also cheaper when sold illicitly? In Australia a small number of brands are responsible for a large majority of market share.

Nonetheless, as shown in Figures 4.2 and 4.3, the tobacco industry decided that it should exploit the public misunderstanding that plain packaging meant all plain white boxes which any small business with rudimentary packaging equipment could make in a suburban factory. For many months it relentlessly promoted the idea that plain packaging would see the market flooded with such all white packs.

In 2011 the Australian prime time television news magazine program A Current Affair sent a reporter to Hong Kong where he interviewed a person said to be a tobacco smuggler. The reporter showed the smuggler a branded pack of a leading Australian brand, Winfield Blue, and asked: ‘How close to that can you get?’ In an instant the smuggler replied: ‘100 per cent’. Winfield Blue has a basic, minimalist pack design with just three colours: blue, white with black text. By contrast, Australia’s plain packs have 14 different fully coloured rotated graphic warnings. They too, would be readily reproducible by anyone with the right equipment. But if anything, they would present far more of challenge to counterfeit than fully branded packs like Winfield.

The British government’s 2014 Chantler report contained a bombshell admission from a BATA staffer who had spoken with the Chantler review team in March. Chantler summarised:

There is no evidence of increased counterfeiting following the introduction of plain packaging in Australia and this is now accepted by tobacco manufacturers locally. [as] Mark Connell of BAT told the review team.

[Mr Connell:] One of the things that we did say . . . is that there would be an increase in counterfeit of the standardised packaging. In other words, the legislation was virtually a blueprint that was given to counterfeiters . . . That hasn’t happened, well, it may have happened in small quantities . . . Our biggest brand which was counterfeited all the time, very professionally I have to say, at least contained a health warning and a graphic health warning [unlike these illicit white brands now prevalent].

Review team: Have you actually seen a reduction in counterfeit?

Mr Connell: Absolutely. Absolutely. [our emphasis]

Illicit trade in Australia has nothing to do with plain packs. Such levels that exist are unquestionably a reflection of the high price of tobacco products in Australia, and a small section of the market’s willingness to buy far cheaper illegal substitutes. As Connell says, there has ‘absolutely, absolutely’ been a reduction in such fake copies since the introduction of plain packs. Connell’s now public emphatic statement should effectively put an end to tobacco industry claims that plain packaging encourages counterfeiters – but it won’t. The industry will just keep on repeating the lie.

Illicit trade: pick a big number

This ‘boon to illicit trade’ argument was quite easily the most prominent of those run by the tobacco industry and its supporters in Australia. The same can be said about industry opposition in Britain, Ireland and New Zealand. For many months, the Twitter accounts of BAT’s offices in London, Australian and New Zealand have tweeted on little else than the illicit trade, including claims that plain packaging would increase it.

Since 2005, there have been 10 tobacco industry-commissioned reports on illicit trade in Australia prepared by three consultancy firms – PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) in 2005, (176) 2007 (177) and 2010 (178); Deloitte between 2011 and early 2013 (179–183) and KPMG in 2013 (184) and 2014. (185) The PWC and Deloitte reports used interview data collected by a market research company for the tobacco industry in five Australian cities to then calculate estimates of the size of illicit tobacco consumption throughout the country.

The 2011 report from Deloitte contained a stop-in-your-tracks caveat:

We have not audited or otherwise verified the accuracy or completeness of the information, and, to that extent, the information contained in this report may not be accurate or reliable. (179)

David Crow, CEO of BATA, gave evidence to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing’s hearings into the Tobacco Plain Packaging Bill 2011. Crow pushed the illicit trade argument and referred to the tobacco industry-commissioned Deloitte report, (179) saying:

It is robust research. It is based on thousands of interviews of consumers done in a very thorough way by Roy Morgan Research, who work with Deloitte. The aim was to estimate – and you will never get a real answer?–?the size. That size has been consistent over the past 18 months. The last report found that about 15.6% of the industry is illicit. We say one in five; one in 5½ cigarettes smoked in this country is illicit. (186)

There were a couple of rather large problems with what Crow told the parliamentary committee. He presumably had read the Deloitte report, which states on page 20 that: ‘This initial sample comprised of 9206 identified people. However after allowing for natural sample attrition, 949 respondents completed the survey.’

So 949 smokers in five capital cities, not ‘thousands’, answered questions about whether they believed they had used illegal tobacco (loose chop chop, counterfeit or contraband/duty not paid).

Then there was the problem with Crow’s arithmetical (or was it his rhetorical) ability. 15.6% is not one in five (that’s what 20% would be) or one in 5½ cigarettes. It is one in 6.41, which is less than one in six. So what’s the difference between ‘one in five’ and ‘less than one in six’? Not much you might think? But when you’re talking about the number of cigarettes that would be involved, this means a difference of 741.69 tonnes of tobacco, using the Deloitte data. Depending on what assumptions are made about the average weight of a cigarette (0.75–1g), this translates to between 750 million and 900 million cigarettes and roll-your-own cigarette equivalents.

Crow would have been aware that in the week before he gave evidence, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) published its then latest estimate of how many smokers regularly used illicit tobacco in Australia. Surveying 26,648 people across Australia, of whom 15.1% were daily smokers (and with 17% smoking at all?—?4530 smokers), the AIHW found just 1.5% of Australian smokers regularly smoked unbranded tobacco in 2010 – see Table 3.11 p39. (187) Crow did not refer to this substantially lower estimate.

The tobacco industry-sponsored reports rapidly became objects of ridicule as the manifold problems with them became apparent. The Cancer Council Victoria produced detailed critiques of the reports. (188, 189)

One commenced with:

The Deloitte report on illicit trade released 3 May 2012 once again beggars belief first because (like the previous years’ reports) it features an implausibly large estimate of the size of the illicit market – does anyone seriously believe that one in every eight cigarettes they see people smoking in Australia are fake or come out of plastic bags? (188)

Ultimately, the idea that one in eight cigarettes being smoked (or as high as one in five, if you listened to BATA’s chief executive) were obtained from illicit tobacco suppliers requires that there be an extremely widespread network of illicit tobacco retailers. These suppliers risk massive fines for tax evasion and so cannot trade openly. If one in eight ordinary Australians, predominantly from low socioeconomic backgrounds (190) and therefore often with minimal levels of education, could so easily find such a network of illegal suppliers, why could the Australian Federal Police, with all its resources, not find the same suppliers? While police corruption is not unknown in Australia, Transparency International ranks Australia ‘very clean’ in its 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index, (191) so the idea that police throughout the country may have been corrupt and turning a blind eye, was also not credible.

In April 2014 the three Australian tobacco companies released a report produced by KPMG LLP Strategy Group, London entitled Illicit tobacco in Australia: 2013 full year report. (185) This was an update of the half year report produced in October 2013. (184)

Again, Quit Victoria and the Cancer Council Victoria rapidly published a lengthy critical review of this report. (189) A key component of the KPMG report was a study of discarded packs found in streets. Quit Victoria’s critique concluded that discarded packs were highly unlikely to be representative of total consumption of tobacco in Australia and that KPMG’s ‘estimate of the size of the illicit tobacco market is likely to be substantially higher than is warranted.’

The litter survey largely comprised packs either dropped by smokers or blown out of street rubbish bins but did not include domestic rubbish. Quit Victoria noted:

The survey is therefore not a representative sample of all packs used in Australia and is likely to over-represent packs used by people who work or otherwise spend a lot of time outdoors, and packs used by people who litter. A review conducted by the International Agency for Research on Cancer has suggested that people who use illicit tobacco may also be more inclined to litter. . . .

It is highly likely that the empty pack survey over-represents the packs used by tourists and other overseas visitors and students, all of whom are more likely than the average Australian smoker to be eating out and socialising at outdoor venues, and much more likely to be in possession of packs purchased overseas.

Areas frequented by high numbers of overseas students would also be places where there would be a high volume of discarded packs. Many overseas students live close to the institutions in which they study, in budget-style accommodation . . . Students also tend to eat out a lot in cheap eating places close by, including many serving cuisine from their countries of origin—for instance those in Swanston and Lonsdale Streets in Melbourne. It is interesting that each of the cities surveyed in the report – all of the capital cities plus Geelong, Newcastle, Wollongong, Cairns, Townsville, the Gold Coast, the Sunshine Coast and Toowoomba – is home to at least one university with high numbers of students from overseas.

Sir Cyril Chantler in his report (76) concluded about the KPMG report:

I note that Australian government departments, both Health and Customs, appear to be strongly of the view that KPMG’s methodology is flawed. These departments point to official Customs data, which shows no significant effect on illicit tobacco following the introduction of plain packaging, backed by analysis undertaken by the Cancer Council Victoria (based on data from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey) that suggests that illicit tobacco in Australia is only 10–20% of the level proposed by KPMG. In a situation where estimates differ by such magnitudes, I do not have confidence in KPMG’s assessment of the size of – or changes in – the illicit market in Australia.

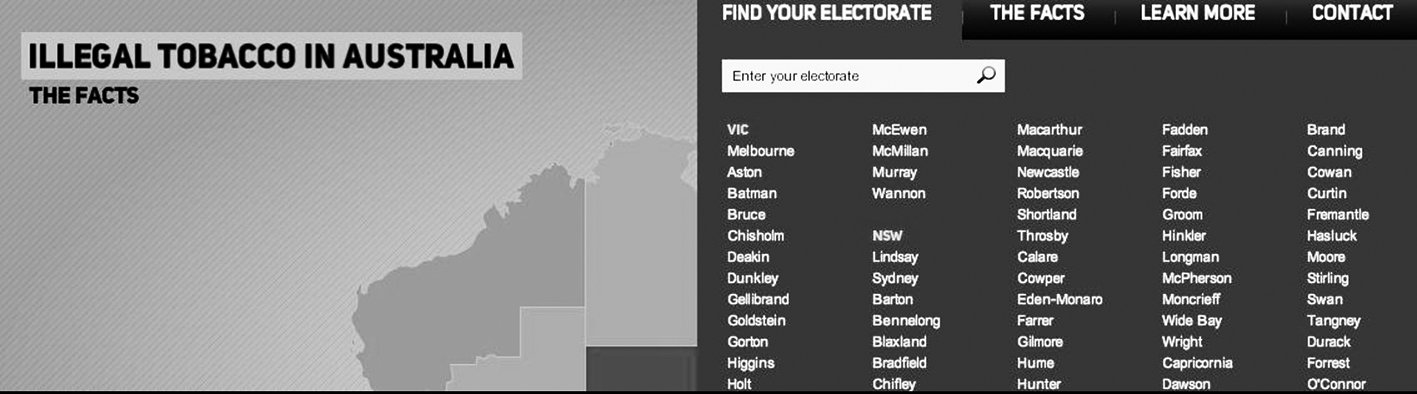

The most bizarre claim about illicit sales was an online national interactive map promoted by BATA (interestingly since removed from http://www.illegaltobacco.com.au/) which allowed searching for the amount of illicit tobacco being sold in any Australian electorate. Browsers could look up the usage estimates in an outer suburban area of a large city like Sydney or Melbourne, as well as look up how much was being sold in the remotest central desert electorate (see a screenshot taken at the time in Figure 4.4). The amount per capita was exactly the same, regardless of location. Illicit sales rates per head of population were claimed to be the same throughout the country. The designers of the website had simply taken the highly questionable estimates of use obtained from the five-city (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth or Adelaide) survey of just 949 smokers and applied them across the country. Apparently, illicit tobacco is as easy to buy in the remote South Australian outback town of Oodnadatta as it is in the outer western suburbs of Sydney or Melbourne and in the most affluent suburbs of cities around the country.

Paul Grogan from the Cancer Council Australia picked up a lot of cynicism about the reports from politicians he often spoke with:

Nobody I spoke to ever took them all that seriously. I’m happy to say most people saw them for what they were worth. Most people in government are pretty aware of reports that are produced to meet the goals of the commissioning agency. People get a report done by [a commercial agency] and it’s got this disclaimer and everyone knows it’s nonsense. It’s good for a headline. It gets stuff stirred up in the media, but I never met anyone who was seriously worried about whatever it was . . . one in in five . . . cigarettes being illicit.

Price falls will drive up consumption

Tobacco companies make most profit from their so-called ‘premium’ expensive brands. I once received a BATA staff training video dating from 2001 from an anonymous sender which included the following exchange:

Senior executive 1: Another example is our guys in marketing and trade marketing, they need to sell five packs of [a budget brand] to get the same profit they would get from one pack of [a premium brand].

Senior executive 2: I mean, five packs of [the budget brand] for every pack of [the premium brand], I mean it’s just a clear statement of fact of what our intentions are. If we don’t sell [premium brand A] and [premium brand B] and [premium brand C], the amount of sheer volume we have to do of [budget brand] to make up for that is just ridiculous. I mean, the factory couldn’t produce it.

Tobacco companies promote and price expensive brands as being of ‘superior’ quality to less expensive brands. However, the industry has known for decades that many smokers cannot tell the difference between similar brands (95) if they are not aware beforehand of which brand they are about to smoke.

Smokers who buy more expensive premium brands to display their supposedly more expensive taste in cigarettes have had this ability severely curtailed by plain packaging. Unless someone looks closely at another’s pack to see what brand is being smoked, all brands – budget and premium – look exactly the same other than for the brand and variant names. This may well cause smokers to ‘trade down’ to cheaper brands, reasoning that they are getting no added value for paying more for a brand that looks the same as all others. This scenario is known in the trade by the dreadful expression ‘commoditisation’. If this scenario became widespread, it would be a major threat to company profitability, forcing price to be a far greater factor in competition between companies. Here, there is some plausibility to the argument that plain packs might cause a downward price war, which could make tobacco more affordable to young people and those on low incomes, which is why the tobacco industry has emphasised this issue.

However, the 2014 Chantler report (76) found that post plain packaging, with the exception of some budget brands, the price of Australian brands has been rising above those caused by tax rises because of the industry increasing its prices. Chantler went on to say:

This objection also assumes that plain packaging is introduced in isolation, without any relationship with broader government tobacco control policies. While tobacco companies may indeed seek to reduce price as a short-term countermeasure, this is a possible problem that is easily counteracted. When the Australian government announced its intention to introduce plain packs, it also introduced an immediate 25% increase in tobacco tax. In 2013, it announced a further four successive rises, each of 12.5%. Concerns or threats of price wars causing unintended greater affordability of tobacco can thus easily be countered by tax increases, which force prices up. Governments can monitor tobacco prices and if necessary increase tax to counteract such developments.

Importantly, with the exception of some ultra low-cost cigarettes, prices for leading brands in Australia have increased above tax rises. Rather than leading to complete commoditisation, it appears that the price differentials between premium and low-cost brands have widened, as the Australian pricing model moves closer to that of other high tax jurisdictions like the UK, with four distinct price segments. Some new ultra low-cost brands have been developed, but this is likely to reflect tax changes more than plain packaging. [our emphasis]

Therefore there is no evidence to date of a commoditisation of the market leading to immediate and widespread price reductions in Australia. It is too soon to make definitive conclusions, but the fact that leading brands are increasing prices above tax suggests that predictions of widespread price reductions are exaggerated, at least in the short run.

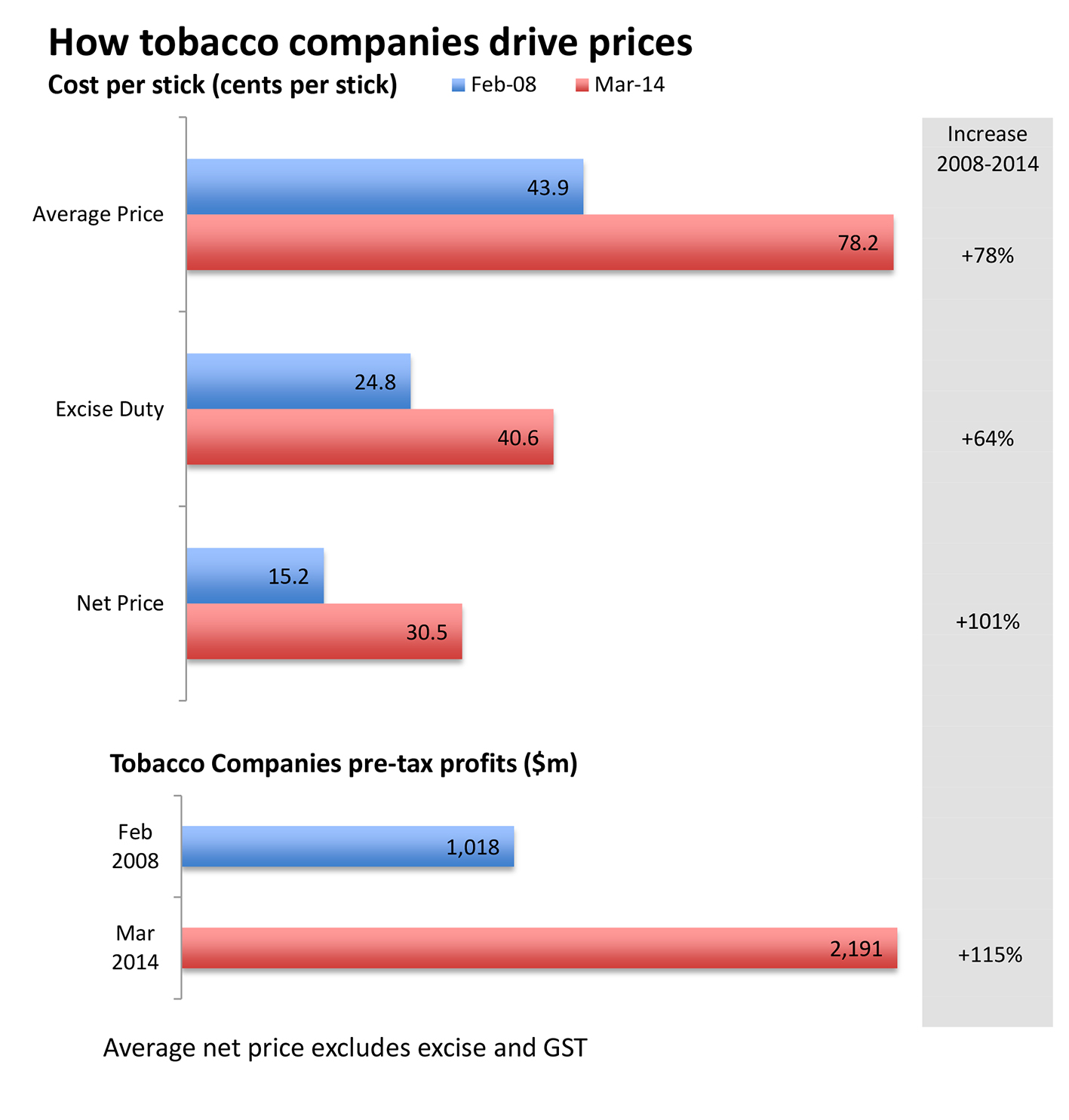

From August 2011 to February 2013, while excise duty rose 24¢ for a pack of 25, the tobacco companies’ portion of the cigarette price (which excludes excise and GST), jumped $1.75 to $7.10. While excise had risen 2.8% over the period, the average net price had risen 27%. Philip Morris’ budget brand Choice 25s rose $1.80 in this period, with only 41¢ of this being from excise and GST. (See Figure 4.5)

Figure 4.5 Contributions of tobacco tax to net sales price, Australia

An Imperial Tobacco Australia spokesman dismissed this by arguing that the data were recommended retail prices, not after-discount retail prices. But Chenoweth noted that:

tobacco industry sources say the level of the manufacturing rebates has remained relatively constant, which allows comparisons between time periods that show the sharp rises. Wholesale prices show similar gains, with Winfields up 13.2% from August 2012 to February 2013.

Chenoweth also wrote:

The overall market moved to low-price and deep discount brands, which grew 5.6% to comprise 37.3% of the market in 2013. It’s the higher prices for top and middle brands, where rusted-on customers stayed loyal to the brands, that have allowed tobacco companies to discount cheaper brands, yet increase profits.

In July 2014, the AIHW released its report on smoking in Australia in 2013. It stated that current use of ‘unbranded’ tobacco (ie: ‘chop chop’) had fallen from 6.1% in 2007, to 4.9% in 2010, to 3.6% in 2013. (194)

With retail display bans, plain packaging not needed

In April 2011, the trade magazine Retail World ran an item titled ‘Retailers facing duplication of tobacco laws’. It stated:

The Australian Retailers Association (ARA) is concerned about the duplication of regulatory burden and compliance costs associated with national plain packaging legislation. ARA Executive Director Russell Zimmerman said in a statement: ‘Retailers have invested in new store fit-outs to ensure they are compliant with state tobacco display bans but they are now left wondering what exactly they are hiding behind cupboard doors if federal legislation will dictate standard packaging.’

Note here that the tobacco manufacturers pay for the new storage facilities, not the retailers. It continued:

National Association of Retail Grocers of Australia Pty Ltd (NARGA) stated that tobacco products are already sold from closed displays at one point of sale in a shop and are not generally visible to customers. ‘The closed displays make the proposed plain packaging pointless,’ NARGA said in a statement.

This argument was one that also featured in the TV ads run by the Alliance of Australian Retailers (AAR). Yet again, it was quite bizarre. Those using it appeared to acknowledge that keeping branded packs out of sight in shops might be appropriate in reducing tobacco’s appeal (‘out of sight, out of mind’) and in further denormalising tobacco to be a non-ordinary consumer good. But of course as soon as tobacco products are sold and brought out from hidden display, they immediately become portable tobacco advertisements, being displayed every time a smoker takes them out to smoke, or places them on public display on a café table etc.

Plain packaging turns the cigarette pack from a glossy fashion accessory into an ugly product purposefully designed to be off-putting for both children and adults. Moreover, there is evidence suggesting that Australian smokers have reduced the ‘display’ of their cigarette packs after the introduction of plain packaging. In an observational study of smoking and pack display conducted before and after the introduction of plain packs, researchers found a 15% decline in pack display and a 23% decline in observed smoking in bars, cafes and restaurants with outdoor dining areas. Increases were observed in the proportions of smokers not displaying their packs face up, and covering them with wallets or other material, and a small increase in the (very small) proportion of smokers who had placed in their cigarettes in other containers. (195)

Plain packaging as an example of ‘nanny state’ legislation

In February 1985, The Age reported that at least three Australians had been disembowelled in the past two years after sitting on swimming pool skimmer box covers shaped like children’s seats that have since been banned. Before the advent of mandatory shatterproof safety glass for showers, many people suffered major lacerations and occasionally died after bathroom accidents. Before 2008, it was legal for fast-buck retailers to sell children’s nightwear that could easily catch fire: many children were hideously burnt and scarred for life. Random breath testing was first introduced in 1976, to the chagrin of the Australian Hotels Association. In New South Wales it was followed by ‘an immediate 90% decline in road deaths, which soon stabilised at a rate approximately 22% lower than the average for the previous six years’.

These are just four of many examples of changes to laws, regulations, mandatory product standards and public awareness campaigns that were introduced following lobbying from health advocates. (196) With these, as with nearly every campaign to clip the wings of those with the primitive ethics of a cash register, there was protracted resistance. Bans and brakes on personal and commercial freedoms are routinely ridiculed as the interventionist screechings from that reviled harridan, the nanny state.

Similar attacks once rained down on Edwin Chadwick, the architect of the first Public Health Act in England in 1848. He proposed the first regulatory measures to control overcrowding, drinking water quality, sewage disposal and building standards. After he was sacked for his trouble, The Times gloated:

We prefer to take our chance with cholera and the rest than be bullied into health. There is nothing a man hates so much as being cleansed against his will, or having his floors swept, his walls whitewashed, his pet dung heaps cleared away.

Yet on the 150th anniversary of the Public Health Act, a British Medical Journal poll saw his invention of civic hygiene, and all of its regulations, voted as the most significant advance in public health of all time.

Those opposed to state intervention in markets subscribe to often unarticulated social Darwinist values that imply that those with the misfortune to be killed, injured or made chronically ill by their participation in untrammelled marketplaces had it coming to them. The unregulated marketplace and community is a kind of noble jungle where the fittest survive thanks to their better education and judgement in their consumer choices, their better ability to pay for superior, less dodgy products, to keep up repairs on their cars and homes, and to get employment in work that is not dangerous or toxic. Children living in poorer housing near busy roads in the leaded petrol era had only their parents to blame for their lead-lowered IQs – they didn’t have to live there! When a toddler drowned in a backyard pool before mandatory pool-fencing laws, it was the fault of the feckless parents for not being more vigilant, and nothing to with failure of government to mandate the cost of a fence as part of the cost of a pool. When kids ingested lead or other heavy metals from dodgy toys when these were legal, their parents should have just done their homework and not bought them.

So in the best traditions of nanny state invective, Imperial Tobacco ran a brief multimedia campaign in June 2011 seeking to conflate plain packaging and the government’s greed for tobacco tax as the twin horsemen of a nanny state apocalypse. The centrepiece of the campaign was a severe, stout ‘nanny’, dressed like an archetypal state official-cum-Gestapo officer. In the TV ads (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G-31ew2k95w) she bellowed and belittled an unseen but voiced young male smoker. Life-size cardboard figures of the nanny appeared in tobacconists.

Imperial’s public statements accompanying the campaign were vacuous bluster about unspecified sinister ‘unintended consequences’ and ‘dangerous precedents’. Without blinking, Imperial advised us that all Australians should be concerned about being on a ‘path to a nanny state’. This pantomime-like campaign ran only briefly on television, suggesting that it was not effective.

Chaos in shops

Tobacco retailers joined the chorus of manufacturers protesting against retail display bans because the manufacturers had been giving retailers financial incentives to display particular brands in positions which maximised customer attention. (‘Plain packaging would have a negative impact on retailers, who currently benefit from manufacturer payments for shelf displays and visibility.’) (192). Some retailing representatives stood ready to support the tobacco companies in their attacks on plain packs.

Since December 2012, all Australian packs have been clearly marked with the brand name and any registered variant name (eg: ‘smooth’). Each brand is delivered to retailers in brand-specific bulk supply boxes. Retail staff then transfer the new stock into the retail dispensers typically located behind them, behind the shop counters. Here, they are placed in brand-specific columns, with either the bottom or the top face of the lowest pack in the column showing to the shop assistant. Both the top and bottom panel of all packs show the brand name and variant. This is exactly the way that fully branded packs were stored, prior to plain packaging. The shop assistant then selects a pack of the requested brand from these columns, when serving a customer.

The tobacco industry and its supporters decided that they could make a big play about the utter chaos that all this was going to cause anyone selling tobacco products. In February 2011, it got the astroturf group it had created, the Alliance of Australian Retailers, (see p95) to run this message to the public, armed with a report from Deloitte, the global consultancy firm.

Astonishingly, Deloitte’s research (197) was based on discussions with just six retailers around Australia (‘Deloitte conducted consultations with two retail operators in each of the following categories: service stations/convenience stores, tobacconists and newsagents.’). These six told Deloitte’s wide-eyed investigators about all the ways in which they imagined plain packs would increase transaction times with customers and Deloitte summarised this in Table 4.1 below.

Table 4.1: Estimated increase in transaction times and associated costs (Deloitte report)

| Operator | Estimated number of daily transactions | Indicative additional time (hours) | Indicative extra annual costs ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service station / convenience store | 200–400 | 455–1,692 | 9,000–34,000 |

| Tobacconist | 100–200 | 323–1,218 | 6,500–24,000 |

| Newsagent | 50–200 | 216–834 | 4,500–17,000 |

Source: Data extracted from Deloitte, Alliance of Australian Retailers, Potential impact on retailers from the introduction of plain tobacco packaging https://www.australianretailers.com.au/downloads/pdf/deloitte/2011_01_31_AAR_Plain_Packaging2.pdf

The range in transactions reflects the different sizes of the six outlets researched. Aside from the unbelievably inept approach to sampling in this report, there would appear to be something very seriously wrong with this table. Consider tobacconists, who serve only tobacco products and so might be expected to be most familiar with tobacco transactions. Table 4.1 shows a range of 100 to 200 daily customer transactions, taking between 323–1218 additional hours (ie. between 193.8 minutes for the shops with 100 customers per day, to 365.4 minutes for those with 200 customers a day!) Later in the report, another table states a further additional 10–45 minutes per day would be needed for ‘stock management’ of the new plain packaging.

Somewhere out of this chaotic report the AAR extracted the sound bite of each transaction taking an additional ‘up to 45 seconds’, as it put in a submission to the government. (198) All based on the guessing of six retailers in a report published 17 months before plain packaging was actually introduced. As you read this, pause from your reading and say to yourself ‘a packet of Marlboro Red, please’ as if you were standing at the counter of a petrol station or convenience store. Then look at your watch and time out 45 seconds. Ask yourself if you can ever recall any interaction with a store employee needing to reach any item within a step or two from the cash register which has taken 45 seconds to find. And then remember that the claim was being made that 45 seconds was the length of the increase in time being claimed, not the actual time. Perhaps they were saying it would take well over a minute for a shop keeper to find an item that they would be asked for many, many times every day.

The really interesting question was what was a company with Deloitte’s reputation doing putting its name to nonsense like this? The Deloitte report was prefaced with an interesting caveat: ‘No one else, apart from the AAR, is entitled to rely on this report for any purpose. We do not accept or assume any responsibility to anyone other than the AAR in respect of our work or this report.’ Fine: there was no reason to rely on the report for any purpose, unless you were the AAR.

In June, the AAR released another Deloitte report (199) with lots of shocking numbers and findings in it about an Armageddon that was going to descend on Australia’s corner stores because of a policy that we’ll recall wasn’t going to work. Here was ‘research’ to prove it. So let’s take a look at how this research was conducted.

First, Deloitte told us that: ‘Roy Morgan Research was engaged by the AAR to conduct a consumer survey to verify the risk of channel shift following the introduction of plain packaging.’ Channel shift is retail jargon for your customers switching to buying their tobacco from bigger outlets like supermarkets, which of course have been attracting small business customers for decades because of their cheaper prices on everything.

Note importantly, that the survey was not designed to examine whether there was a risk in channel shift arising from plain tobacco packaging, but to ‘verify’ it. It was a foregone conclusion, apparently. Great science!

We read that those surveyed ‘were presented with an overview of the proposed regulation and asked whether they thought their shopping experience at a small retailer would be affected.’ So they were presented with an overview that would assist in ‘verifying’ the risk of channel shift. Hard to imagine any chance of push polling effect operating there!

Catastrophically for corner stores, independent petrol stations and newsagents, more than one in three smokers (34%) and 18% of non-smoking consumers told the polling company after hearing the overview that they were ‘either somewhat likely or very likely to change where they shopped as a result of plain packaging.’ So why would they do this? Smokers thought they would be ‘more likely to be given the wrong tobacco product’. So presumably they think that small shopkeepers are a cut below the staff in supermarkets and specialist tobacconists, and won’t be able to read the name on the pack or the column on the pack shelving behind the counter. Why else would there be more mistakes in handing over the brand requested in small businesses than in larger outlets? They would be packaged the same wherever they are sold.

Another reason given was that small store staff ‘would have a harder time finding what I want and so ‘queues would be longer’. Again, how could this be different in small stores compared with large stores, given that the packs will be the same in all outlets? Particularly when we discover below that small shopkeepers think supermarkets will stock far more brands, which presumably might make the search more difficult in the larger outlets.

The report also presents results from focus groups with small retailers who believed that channel shift may occur because of:

- the increase in time required to complete a tobacco-related transaction would lead to customers becoming increasingly frustrated due to delays and longer queuing time

- the knowledge that a larger retailer, e.g. a major supermarket with a broader range of products, would always have what they require.

Let’s repeat that. Small shopkeepers think that the introduction of plain packs will cause them to cut back on the range of products they offer, but that supermarkets won’t do this? How could that be?

These unacceptable delays would have seriously consequences for small businesses, Deloitte argued, saying:

The increase in time required to complete a tobacco-related transaction would lead to customers becoming increasingly frustrated due to the delays and longer queuing time. As a result, many small retailers believed such customers would leave their store without making a purchase and would opt to visit a larger retailer with more staff.

However, reading deeper into the report produces not a little amusement. At the end of Table 3 (see top of page 24) (199) we read reasons why customers shop at small retailers. ‘Convenience’ and ‘location’ rank highest. And what is the least important reason that tobacco customers choose to shop at small retailers? That’s right. It was ‘quick service’, at just 2%. Plain packaging might only improve matters!

The industry then promoted this ‘big enough’ number, hoping that no one would question it. It also had a small chorus line of dedicated supporters who were willing to repeat this nonsense. One was Alex Hawke, one of the federal Opposition’s rusted-on opponents of ‘excessive regulation’. In July 2011 he intoned in parliament:

I also rise tonight to put on record my opposition to proposals such as plain paper packaging legislation – ill thought out proposals put forward by government committees and the bureaucracy which will not achieve their ends and which will artificially burden small businesses around our country. I was visited by the Alliance of Australian Retailers on behalf of those small businesses which will be most impacted by this bad legislation – an ill-considered idea put forward by a government addicted to legislative response. An independent report by Deloitte, funded by the Australian Alliance of Retailers, identifies key areas in which small businesses will suffer from such a piece of legislation. One area is stock management – the legislation could double the time spent managing cigarette stocks. Increases in sales transaction times could cost independent retailers up to $30,000 a year. Other problem areas identified were product selection errors and increases in shrinkage. The list goes on. We must remember that these are products which are already required by law to be behind a counter.

We now have a situation in our country where we pay a government bureaucracy to determine – by government decree – that the ugliest colour in this country is olive green. What if you happen to like olive green? What if you happen to be a government-mandated freak? That is what the government has paid a bureaucratic committee to determine – that olive green is the ugliest colour in our country. That is what we are paying people in government to determine today. I want to record my sympathy for all of those small retailers and those people making a stand against this ridiculous form of nanny state legislative response to ordinary, everyday problems. (200)

The Australian Retailers Association ran a similar line:

Like retail display bans, plain packaging is likely to significantly increase the time taken to complete a transaction including the sale of tobacco products. Regulations that increase transaction times have been estimated to cost businesses up to half a billion dollars [$461 million], equivalent to 15,000 jobs. Increased transaction times also often lead to ‘retail rage’ at the checkouts which is a health and safety concern for retail employees, particularly young workers. (201)

Five months after the December 2012 implementation, this ‘store chaos’ theme continued unabated. Jeff Rogut, a store owner and chief executive of the Australasian Association of Convenience Stores, flew to London to speak at a Philip Morris sponsored meeting about plain packs in April 2013. In an article published in Asian Trader he wrote that staff:

. . . have to put the stock away, which has again caused enormous angst in terms of layouts in the stores. Remember they are behind closed doors already, they then have to open the doors and where do they put the packs? Previously you used to have the best sellers in the middle, easy to reach and easy to identify. Now we’ve had to think through – do we do it by brand, alphabetically, by company? How do we make it easier for our people to serve? And that decision has really not been made – every store is working through finding the most efficient way to get their staff to recognise the product.

Every time any new product or newly packaged existing product is sold in any store, staff obviously have to make decisions about where to store these products. Cigarettes in new packages are no different.

Rogut then painted a fascinating story of plain packs being responsible for the collapse of security in Australian shops:

Generally you have one person behind the counter and they have to physically turn their back to the customer to look for the product. In that time, a car could have filled up and driven off, somebody could have pulled out a knife, a gun or a baseball bat. It really is a security issue for our industry.

The problem with this ludicrous account is that those serving in Australian tobacco retailers have always had to ‘physically turn their back to the customer’ when selecting a pack of cigarettes from the storage shelves – plain-packaged or not.

And finally, Rogut painted a picture of utter chaos with not 55%, not 60%, but 59% of cigarette transactions resulting in the wrong brand being passed to the customer.

About 59% of the products being given to customers are actually incorrect because staff are confused. Fortunately when they scan it, it recognises it’s not a Windfield [sic] Blue but happens to be a Windfield [sic] Red – the feedback is that there has been a high incidence of that. Recording of the stock was easy before – you could see it was a Red, Blue or Green. Now they physically have to read it using a hand scanner to make sure that they have the right stock in store.

But this gripping apocalyptic vista was still not yet finished. Rogut continued about stores having to bring in additional staff to train shop assistants where to look for the different brands and ‘how to serve customers better.’ Imagine such a training session:

Trainer: Now, behind you – as they have always been – is your tobacco stock. Open the doors to reveal the storage columns. Now, try and find a pack of brand X.

Trainee: Well, here it is, where it’s always been . . . in the column for that brand.

So what does independent research show actually happened in shops after plain packaging was introduced? It shows that plain packaging had no lasting impact on serving times. A study examining cigarette retrieval times before and after the introduction of plain packaging has been published (202). In June and September 2012 (before plain packing was implemented), and in the first two weeks of December 2012 (the first two weeks after plain packaging became law in Australia), and again in February 2013, 303 stores were visited in four Australian cities by trained fieldworkers. They asked for a cigarette pack of a pre-determined brand, variant and pack size, unobtrusively recording the time from the end of the request to when the pack was scanned or placed on the counter.

The study found that the average

. . . December retrieval time (12.43s) did not differ from June (10.91s; p=0.410) or February (10.37s; p=0.382), but was slower than September (9.84s; p=0.024). In December, retrieval time declined as days after plain packaging implementation increased (ß=-0.21, p=0.011), returning to the baseline range by the second week of implementation. This pattern was not observed in baseline months or in February.

The study authors concluded that:

Retailers quickly gained experience with the new plain packaging legislation, evidenced by retrieval time having returned to the baseline range by the second week of implementation and remaining so several months later. The long retrieval times predicted by tobacco industry-funded retailer groups and the consequent costs they predicted would fall upon small retailers from plain packaging are unlikely to eventuate.

Here is a link to a video of a person buying cigarettes in a Sydney shop in early 2013. The time taken for the shop assistant to find the requested brand is negligible. The time taken to transact the credit card payment takes far longer. (203) http://tiny.cc/yttrox

Plain packaging will cause great financial hardship to small retailers

This was a highly misleading argument that sought to conflate the sales reduction threats posed by plain packaging with the competitive price disadvantage that small retail tobacco outlets experience when competing with large retail chains like supermarkets. Large retailers can offer cheaper prices for cigarettes (and all products) because of economies of scale that allow them to trade off smaller profit margins per pack against the much larger volume of trade they attract. Small retailers have long been aware that smokers can buy their supplies at cheaper prices from supermarkets or ‘cigarette barn’ chains. The threat of plain packaging to all retailers is of reduced sales caused by more smokers quitting and fewer new smokers starting. Any such effects will impact all retailers across the board – not just small retailers – because all packs, regardless of where they are sold, come in plain packaging. There is no plain packaging impact for small business and another one for larger tobacco retailers.

Further counters to these arguments follow:

- Efforts to engender sympathy for small retailers should not blind us to the reality that they are knowingly selling a lethal product. Nobody now selling cigarettes has taken up this role without being aware that they are lethal. Many small retailers also sell cigarettes to children. The interests of consumers and public health should override sympathy for those who may not make so much profit from sales of a product that kills one in two of its regular users.

- Changes to smoking patterns occur over time. Retailers can and do develop other sales lines. When smokers quit, they do not place all the money they would have spent on cigarettes in a box under the bed. Like people who have never smoked, they spend their money on other goods and services instead. These purchases benefit many small retailers.

- There is an obvious contradiction between the industry argument that plain packaging ‘won’t work’ and their frequent claims that it will harm retailers through loss of sales.

The slippery slope

No other consumer good kills half of its long-term users (13) when used as intended by the manufacturer. No government or recognised health authority in any nation has ever called for the plain packaging of any other consumer product. While governments and health authorities are rightly concerned to reduce harms from alcohol or junk food, tobacco is unique as a consumer product where the clear and intended aim of government policy is to end use.

Tobacco advertising began to be banned in Australia from September 1976, when the government implemented legislation to end direct advertising of cigarettes on radio and television. Over the next 16 years further legislation incrementally stopped tobacco advertising and promotion through other media, with state bans starting in 1987 in Victoria, culminating in 1992 with the national Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act. In 2014, 38 years after tobacco advertising began being banned, and 64 years after the lethal nature of cigarettes was incontrovertibly demonstrated, other categories of harmful products (eg. alcohol, energy dense foods) have not been subject to similar forms of legislative restrictions on their advertising. If there is a slope leading from tobacco advertising bans to those in other areas, then that slope appears to be decidedly non-slippery.

You’re on your own with this, Big Tobacco

The desperate tobacco industry sought to pull in likely allies from other industries into its slippery slope campaign. But this was likely to prove difficult: even the corporate world has now started to turn on its own rotten apple, with an editorial in Packaging World stating: ‘The tobacco industry should steer clear of complaining of being singled out, which, in large measure, stems from its products being like no other consumer packaged good.’ (118)

The slippery slope ‘what product will be next to fall to plain packing?’ argument was implied in a BATA advertisement, but this drew immediate criticism from a section of the alcohol industry. Stephen Strachan, chief executive of the Winemakers Federation of Australia said his industry rejected any suggestion of an equivalence between alcohol and tobacco implied in the ad. ‘Our industry does not like any association between tobacco and alcohol’ (204) he said. Tobacco was on its own in this one.

Illicit drugs aren’t sold in glossy packaging but many still use them

The obvious retort to this claim is to point out that, if illicit drugs were beautifully packaged, displayed in shops and advertised, even more people would be likely to use them than do now. Of the few nations and states that have decriminalised the personal possession of cannabis, only Colorado, USA, allows it to be sold openly in shops, as if it was another ordinary item of commerce. None allow it to be commercially packaged or advertised.

The repackaging turnaround time was too short

The industry argued that companies needed many months to set up the new printing processes to completely repackage all of their brands at once. However, the requirement to change all packaging to ‘plain’ poses exactly the same challenges to a nation’s tobacco industry as a requirement to introduce new pack warnings when all packs are required to be reprinted by a specified date. With almost every nation requiring health warnings, and as of November 2012, 63 nations required graphic warnings (205), there are many nations which have experience in setting deadlines for the tobacco industry to comply with legislation to change the printing for all packs.

In Australia, Imperial Tobacco issued a press release in November 2011 arguing that it would need 17 months after the plain packaging legislation was declared law to change its printing for all its brands. Asking colleagues in other nations, the typical time given to companies to change all packaging for new generations of pack warnings has been 6–12 months.

There is ample evidence from other consumer products that companies can move speedily to introduce new forms of packaging either following legislation or for commercial reasons. While the tobacco industry needs to be given a reasonable period to comply with repackaging of all its products, government officials should be very circumspect about any claims for lengthy transition periods, and share information with other nations about the times that were required for repackaging in the past for packaging changeovers.

Won’t plain packaging prevent the industry and governments from providing information about less harmful tobacco products?

The tobacco industry often cites freedom of speech protection, arguing that they have a right to inform consumers about their products, especially those that may be potentially less harmful (although the tobacco industry has a long history of misleading consumers about such claims (206)). This erroneously implies that cigarette advertisements contain important consumer information and that smokers base their decision to smoke by weighing up such information and making an informed choice.

The tobacco industry has used this argument for decades to try to retain the right to advertise. In fact, as discussed in Chapter 3 tobacco advertising is one of the least informative forms of all advertising. And aside from a number indicating the number of cigarettes in a pack, packs rarely if ever contain any ‘information’ beyond the brand name and number of cigarettes in the pack. The last time Australian tobacco companies tried to be ‘informative’ on their packs was when they used descriptors like ‘light’ and ‘mild’. In 2005, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) accepted court-enforceable undertakings from the three major Australian tobacco manufacturers, Philip Morris (Australia) Limited, British American Tobacco Limited and Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited, under which the companies agreed to stop using terms such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’ and to provide a total of $9 million for corrective advertising to be run by the ACCC.

Tobacco companies are the last bodies who should be involved in making decisions about health information. If the government wishes to provide such information, on the basis of expert advice rather than tobacco company lobbying, it has many different options.

Covering up the packs

With the exception of the first very small pack warning introduced on packs in 1973, with all three subsequent warnings, Australia saw a succession of knowing predictions from talk-back radio callers that smokers would be one giant step ahead of out-of-touch governments by simply transferring their cigarettes to elegant cases, or buying natty covers to hide their eyes from the warnings. But it never happened to a less than trivial and rapidly vanishing degree with any of the three generations of pack warnings, including the graphic warnings required from 2006. With plain packs, we didn’t have to wait long before it started again.

First out of the blocks was a cartoonist for Rupert Murdoch’s The Australian newspaper, Bill Leak, who was incensed about the nanny state implications of the imminent plain packs. He sought legal advice on whether he could produce covers with fake brand names like Honeymoon, Post-Coital Cigarettes, Tree Huggers, Vegetarian Cigarettes, Man Up: Smokes for Blokes, Ripped: Fitness Cigarettes and Fatales: Diet Cigarettes 99 per cent fat free (‘with a sexy sheila on the pack’). His legal advice was apparently that he would likely end up in court. Health Minister Nicola Roxon responded to this superbly, saying: ‘Everyone likes a laugh, but when so many people die from smoking, it doesn’t seem so funny anymore.’ (207) We never heard from Bill again.

But with the 1 December 2012 full implementation date, an opportunistic small businessman from Queensland was not to be denied his 15 minutes of fame, announcing that smokers could now buy stickers to cover the front and back of the new packs (see http://boxwrap.com.au/). Just $8.75 would buy enough for six packs, with choices ranging from a map of Australia to a rear view of a young woman with her legs apart.

A month after the launch, I noted that since launching his box wrap stickers in early December, he had been deluged with a whole 386 Facebook ‘likes’, and 1319 views of his YouTube promotion. A whole 24 people had followed him on Twitter, 21 of whom lived outside Australia. These were mainly pro-smoking groups who saw plain packs as a strike at the heart of their inalienable freedom to buy a product in beautiful packs, all market tested to their last square-centimetre, that will kill half its long-term users. English libertarian Chris Snowdon got characteristically very excited when he came across publicity for the wraps, blogging triumphantly: ‘You’d have to be simple not to have predicted this (Simon Chapman said it would never happen, natch). Plain packaging was always going to create commercial opportunities for those who make covers, stickers and cigarette cases.’ (208)

The threat of covers and wraps being taken up extensively never eventuated. In an observational study of people displaying cigarettes packs before and after the plain packaging legislation, use of ‘covers’ rose from only 1.5% to just 3.5%. In 1000 smokers, only 35 were observed to have gone to the bother of using covers. (195)

Like all the opportunists who lost their money with previous cover gimmicks for the older health warnings, our Queensland entrepreneur looked like an early candidate for a 2013 Darwin award for heroically failed business acumen (see http://www.darwinawards.com/). On 2 February 2014, his Twitter following had fallen to just four (https://twitter.com/boxwrap) and his Facebook page (http://www.facebook.com/boxwrap) had grown to just 687 likes – less than many 14 year olds have – with the last post made in July 2013.

Anyone who takes the trouble and expense of hiding their eyes from the pack warnings is engaging in obvious denial. Evidence shows that smokers who actively try to avoid exposure to pack warnings by covering them up, have higher subsequent rates of quit attempts than those who don’t. (209)

The news media were interested in this for about two days in early December 2012, and then the story died. Advocates prepared the following communication points in the improbable event that it might have spread.

- Every generation of new pack warnings over last 30 years has seen minor entrepreneurs trying to cash in like this. We are now seeing it with covers.

- A tiny minority of smokers buy them maybe once, but then can’t be bothered.

- Many suburban markets have forlorn vendors with tables covered with pack covers, but nobody is buying. They have lost their money.

When you think about it, the very act of going out of your way to cover up a warning shows that such people are actively avoiding being reminded of what smoking is doing: a bit like a child covering up their eyes for the scary scenes in movies – but unlike movies, the scare here is real and won’t going away by not looking at it.

We now turn to a consideration of the strategies and tactics used by the tobacco industry across the four years of their campaign.

Astroturfing: the Alliance of Australian Retailers

As discussed, the tobacco industry had long sought to avoid coverage in the Australian news media because of the endless potential embarrassment provided by its now very public internal documents, made public in the 1990s through whistleblowers (210) and the millions released under the Master Settlement Agreement. (211) It also knew it had very poor public credibility and was held in low public trust. So it invested further in the time-honoured strategy of ‘astroturfing’: the finding and/or founding and funding of seemingly independent third party organisations and spokespeople. It hoped that many would not understand that these groups were connected to the tobacco industry. Tobacco companies have used astroturfed organisations for many years globally, including in Australia.

Knowing the welcome mat laid out for it was like that offered to the Grim Reaper,1 the Australian tobacco industry was an early pioneer in the development of apparently independent lobby groups set up to attack everything from pack health warnings to attacks on sponsorship. For example, it helped establish the Confederation of Australian Sport in 1976 where ‘the salary and office expenses of the confederation’s president, Wayne Reid, are paid by the Australian tobacco manufacturers under a separate consultancy agreement with each of the three companies.’ (212)

Less than three weeks out from the federal election polling day of 21 August 2010, we learned of the existence theAlliance of Australian Retailers. No one had ever heard of it before it took to the media, opened a website (https://www.australianretailers.com.au/) and began running advertising in newspapers and on television. Initially, it was publicly fronted by Sheryle Moon, the executive director of the Association of Convenience Stores.

The board of the Association of Convenience Stores was chaired by the supermarket conglomerate Coles, owned by the Wesfarmers group. On learning that it had been misled about the funding for what was ostensibly an anti-Labor party campaign, Coles ordered the association to withdraw from the campaign. (213) Moon was no longer the public face of the alliance. Two days later, the other main supermarket chain, Woolworths, revoked its membership of the association over the campaign and demanded that its $15,000 in annual fees be returned. (214) Any tiny ray of respectable big retailer support the alliance might have hoped for was now gone. But as we’ll see below, it had major funding from the three tobacco companies and advertisements continued to be published and broadcast.

Those in tobacco control were incredulous when Moon made her debut. Angela Pratt from Nicola Roxon’s office told us: ‘When Sheryle Moon first appeared, we kind of thought, well, is this the best that they can do? Surely not?’