4

The Archaeology of Viewbank Homestead

The archaeological remains of Viewbank homestead have remained relatively undisturbed. Extensive archaeological evidence uncovered at the site by Heritage Victoria provides a rare and important opportunity to study middle-class material culture from this period of Melbourne’s history. This chapter provides an overview of the excavations including methods, excavated areas, outcomes and artefacts. It then goes on to discuss the post-excavation artefact work, and in particular the artefact processing and cataloguing methods used for the author’s PhD research (Hayes 2008). This includes the categorisation of artefacts and analytical tools applied to the assemblage, along with limitations restricting the study.

THE EXCAVATION OF VIEWBANK HOMESTEAD

The first excavation at Viewbank homestead was undertaken in April 1980 for the Archaeological and Anthropological Society of Victoria and focused on part of the tip. There is a very brief, one page excavation report that indicates that a trench of 3 m by 1 m and 50 cm deep was dug into the tip area. The tip was interpreted as dating to sometime in the second half of the 19th century. A large number of bottles and ceramics were uncovered (Willacy 1981), but have since been lost. The report also detailed that the homestead site had been vandalised and the tip had been turned over by bottle hunters prior to the work. Further work on the site was conducted by archaeologist Fiona Weaver (1991) who undertook a survey of archaeological sites along the Plenty River for the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works in 1990. This included the Viewbank homestead and gardens. Viewbank was recorded as being of high significance. Weaver (1991) also notes that: ‘Substantial sub-surface remains are present, and considerable erosion is occurring to the foundations and terraces from the activity of stock’.

Heritage Victoria later carried out three seasons of archaeological excavations under the direction of Dr Leah McKenzie, and this excavation is the basis of the current research. The first of these was of three weeks duration in April 1996 and uncovered three corners of the homestead and a cellar (McKenzie 1996:10, 1997:7). Staircases leading to the main entrance of the homestead were also exposed. In September 1996, resistivity, magnetometer and ground-penetrating radar surveys were carried out (Heinson et al. 1996). The second excavation season took place in April 1997 for two weeks, and focused on the tip area in order to uncover the material culture of the inhabitants of Viewbank. A small amount of work was also done at the homestead to establish stratigraphy. The third season was conducted in January and February 1999, and continued the work on the homestead and the tip, as well as investigating potential outbuildings associated with the homestead.

Unfortunately some of the trench books have been lost in the years since excavation was completed. Trench records are missing for two trenches in the homestead area, and for the front stairs area. For the 1996 season there were reports written by the trench supervisors, but these were not compiled for the 1997 and 1999 seasons. McKenzie (1996) presented the findings of the 1996 season at an Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology conference later that year, and has written a draft report on the 1996 and 1997 seasons (McKenzie 1997). Heritage Victoria prepared trench plans for the homestead excavation in Area A and the University of Melbourne prepared a site plan.

Dig Methods

Excavation was conducted by manual digging with hand-picks, shovels, trowels and brushes. All material excavated from the tip was sieved using nested sieves of 4 mm and 2 mm mesh. Volunteers from universities and historical societies conducted the excavations under the direction of archaeologically qualified trench supervisors.

Excavation in the homestead area was done mostly in large 10 m by 10 m trenches with finer spatial control maintained by wall footings and room spaces. The remaining trenches, dug to explore outbuildings and the tip, were smaller. For the first two seasons excavation followed the locus/level system with baulks left between trenches to highlight stratigraphy, a method originally developed by Wheeler and expanded by Kenyon (Hester et al. 1997:74, 89). A locus number was given to horizontal areas of the deposit and a level number to the vertical location. Level numbers are the same for that depth across loci. Use of this system varied between the trench supervisors. In the final 1999 season, the context system was used. Deposits and building features were recorded as features with sequential numbers. For all seasons of excavation 18there were some cases where the information in the trench books lacked sufficient description for confident interpretation.

Excavated Areas

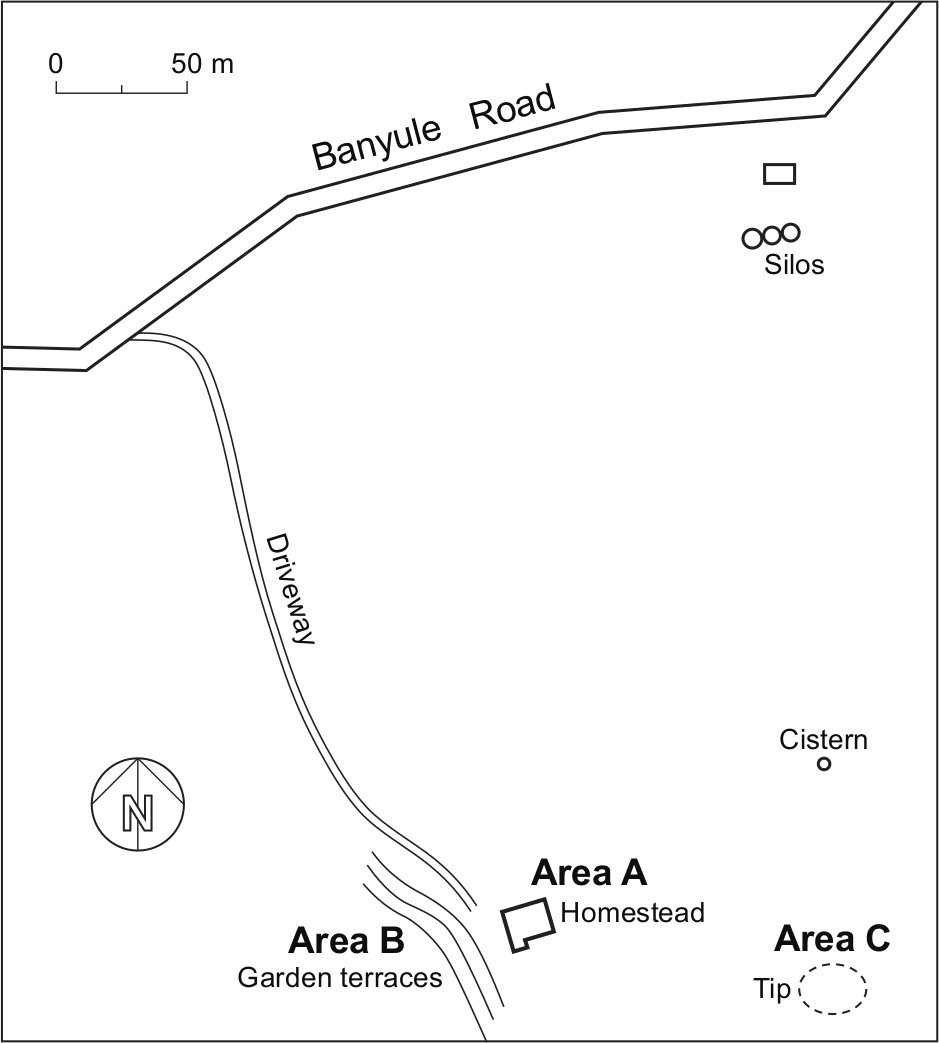

There were four areas of excavation: the homestead (Area A), external stairs leading to the homestead (Area B), the tip (Area C), and exploratory trenches for outbuildings in various locations (Area D) (Figure 4.1).

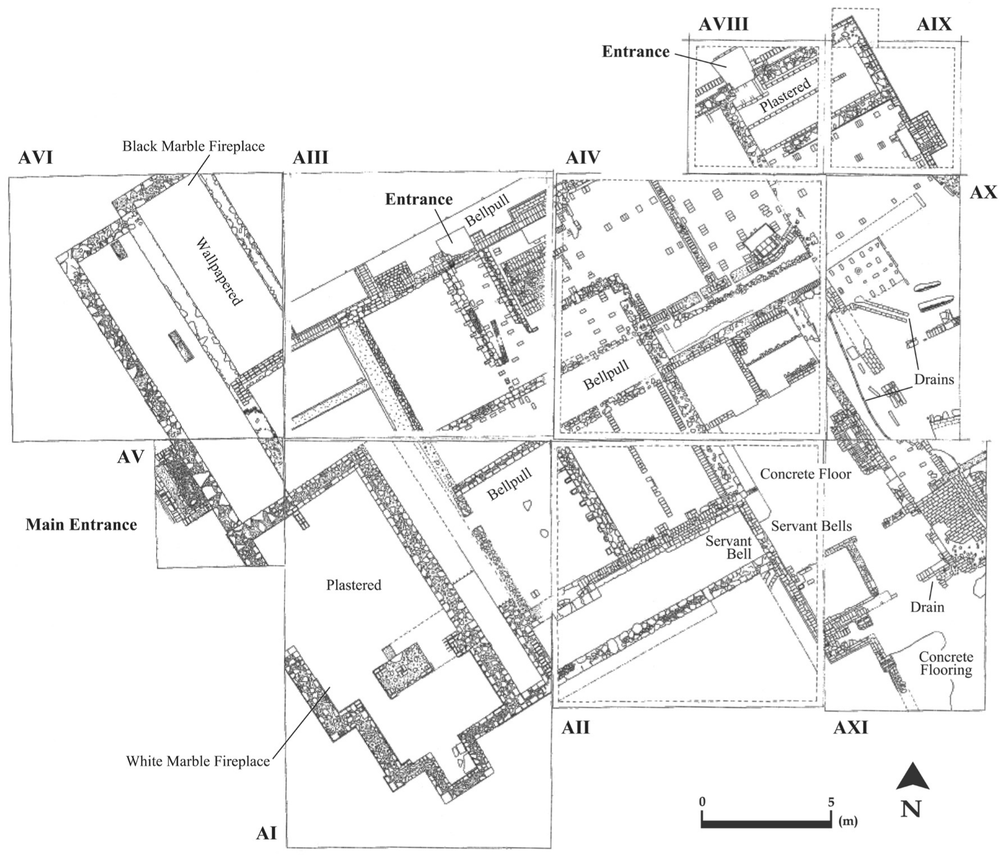

Area A comprised the Viewbank homestead building, which was set into a terrace at the top of the hill (Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.2). Heritage Victoria prepared trench plans for the homestead and as part of the author’s PhD research, contexts included in this analysis were mapped on the plans and stratigraphic matrices were prepared.

Figure 4.1: Plan of the Viewbank site showing excavated areas (Area D comprised of test trenches in various locations around the homestead) (Source: adapted from plan prepared for Heritage Victoria by the University of Melbourne).

Excavations confirmed that there were at least three periods of construction for the homestead (Heritage Victoria 2005). The initial house constructed for Williamson around 1839 was built with hand-made bricks and was single storey (see Figure 4.3, red section). The first extension built for the Martin family was probably built by architect John Gill in the second half of the 1840s and was of a notably better quality than the first house (see Figure 4.3, blue sections). Rooms in this part of the homestead were decorated with cornices and wallpaper (McKenzie 1996:10). It appears that in the 1850s or 1860s a second extension was undertaken at the rear of the homestead (see Figure 4.3, green section). Figure 4.4 provides a plan showing key details uncovered by the excavation.

Figure 4.2: Aerial view of the Heritage Victoria excavation of the homestead facing north (Source: Heritage Victoria).

Area B constituted Viewbank’s stately gardens (Figure 4.1), which included a series of terraces following the contours of the hill to the west of the homestead, steps leading to the homestead, and a flat terrace possibly used as an outbuilding or flower garden. The garden terraces were significant earthworks and can still be seen today by satellite (Figure 4.5). They indicate that significant effort had been made to lay out a stately garden. The steps leading up to the homestead were constructed from brick with stone cladding and were flanked by Italian cypresses (McKenzie 1997:9). The driveway, with its curved terracing marked by pines and oaks, is also part of Area B. Excavation of the steps was undertaken, but there is no record of this work in the trench books and therefore context information for this area is not known.

Area C was a tip located approximately 100 m behind the homestead to the east (Figure 4.1). The surface scatter of artefacts in tip area covered approximately 10 m by 10 m. Ground-penetrating radar work revealed that the tip had a maximum depth of 1.1 m (Heinson et al. 1996). Three 5 m by 2 m trenches were excavated running north/south through the tip and this constituted only part of the total tip. Cut marks into the clay were noted at the bottom of the trench. McKenzie (1997:12) suggests that the hole may have been dug for clay to make bricks for the homestead, and subsequently used for disposing of household rubbish. This pit would not have yielded sufficient clay to build the whole homestead, but possibly part of it. A total of 27,873 artefact fragments were recovered from the tip. The deposits in the tip were fairly homogeneous, and the tip appears to have been used over a short period of time in the 19th century, probably solely by the Martin family. This is discussed in more detail, using evidence from the assemblage, in Chapter 5.19

Figure 4.3: Homestead plan showing building phases (Source: adapted from plan prepared by Heritage Victoria).

Figure 4.4:20 Homestead plan showing excavation details (Source: adapted from trench plans prepared by Heritage Victoria).

Figure 4.5: Satellite image of the Viewbank site showing garden terraces (Source: Google Earth, accessed 3 August 2007).

ARTEFACTS

Heritage Victoria’s database recorded 3,754 catalogue numbers and approximately 53,800 artefact fragments for Viewbank homestead. During the excavation, artefacts were given catalogue numbers and were roughly grouped by material type. After the excavations, Heritage Victoria prepared a hand written catalogue of artefacts with the number which had been given to the artefact in the field, a brief description and the contextual location. Prior to the commencement of this current project the artefacts had been given new numbers and entered into Heritage Victoria’s artefact database for curatorial purposes.

A small number of projects were conducted on the artefacts in the years following Heritage Victoria’s excavation. The faunal assemblage was analysed by Howell-Meurs (2000), and Furlong (2002) examined the chemical contents of five small, clear bottles containing powders. Courtney (1998) examined the clay pipes in the assemblage and mentioned them in her Masters thesis, but no formal analysis was undertaken. Ellis (2001) catalogued and analysed approximately 80 artefacts relating to children from across the site. However, the assemblage retains much potential beyond these studies and artefacts from the tip in particular warranted the research presented here.

Additional artefact processing work was conducted on the ceramic assemblage by archaeologist Alasdair Brooks and a team of volunteers. The aim of this work was to sort the ceramics by ware and decoration and also involved labelling each individual fragment with the original number given to the artefact in the field along with the Heritage Victoria catalogue number.

The most comprehensive cataloguing and analysis of the assemblage was conducted for the author’s PhD from 2005 to 2008, and this forms the basis of the present study. The Viewbank artefacts were stored at the Heritage Victoria laboratory in Melbourne at this time and all artefact work for the project was conducted there. For detailed information on methods see Hayes (2007, 2008). The remainder of this chapter discusses the artefact processing and cataloguing methods relevant to this study.

Artefact Processing

Due to the large size of the Viewbank assemblage, this study focuses on deposits that related specifically to the Martin family’s occupation of the site from 1843 to 1874. There is comparatively little known about the previous and subsequent occupants of Viewbank homestead, and the majority of artefacts recovered from the site are associated with this period. Deposits were selected for analysis according to the following criteria, determined by the excavation records: they were stratified, relatively undisturbed by 20th-century impacts, and had a high potential to be related to the Martin period of occupation. The most significant deposits of interest to the current study are those from within the tip, and all contexts excavated by Heritage Victoria from within the tip are included in the analysis. Only three contexts from the homestead trenches are included here as they were the only deposits in this area that contained artefacts that could be associated with the Martins’ occupation of the site. These were A-III-12, A-II-3 and A-II-3.2. A further 12 contexts from the homestead trenches where included in the initial PhD research (Hayes 2008:215–238), but are not included here as they added little to the overall interpretation of the site.

Extensive splitting, tagging, bagging and sorting of material in boxes was required at the commencement of this project. This was necessary because many of the artefacts were in bulk bags of mixed form and sometimes material. Bulk bags were sorted, and stratigraphic information was added to the labels using the original hard copy catalogue.

Artefact types related to the domestic occupation of the homestead were catalogued. Building materials and fittings were not catalogued, as the information in the Heritage Victoria database was sufficient to address the research questions for this artefact type. The faunal assemblage had already been analysed by Howell-Meurs (2000) and was not repeated for this project as reference to her work provided sufficient information.

Initially, artefacts were divided into broad fabric types: ceramic, glass, metal and organic. The ceramic artefacts were further divided by ware: bone china, coarse earthenware, porcelain, redware, 21stoneware, white ball clay, white granite and whiteware. Second, the ceramics were divided by decoration: transfer-printed, flown, gilded, painted, moulded, undecorated and other. The third stage in processing was to divide the ceramics by form.

Glass artefacts were sorted initially by form and then by glass colour. This was done as a second stage due to the difficulty in distinguishing variations in glass colour from the different parts of a single artefact. Colours included: aqua, black, blue, brown, cobalt blue, colourless, dark green, green, light green, purple, yellow and white. Metal artefacts were divided into aluminium, copper, gold, iron, lead, silver and composite. Organic artefacts were divided into bone, leather, textile and wood. Both were then divided by form.

Artefact Cataloguing

Cataloguing was conducted in a Microsoft® Access® database, custom designed for this project. Artefacts were catalogued in two phases: accession and type series. The advantage of this approach is that two separate (but related) catalogues were generated: one containing the formal attributes of the artefact and the other containing the interpretive aspects of each artefact type. This separation of identification and analysis allows for clarity on the inherent aspects of an artefact versus the interpretations the archaeologist has made of the artefact (Brooks 2005a:16–18). It also streamlines cataloguing as attributes common to a type only need to be recorded once (Crook et al. 2002:34).

Phase 1: The Accession Catalogue

The accession catalogue recorded the formal attributes of the artefact: object number, box number, form, material 1 and 2, quantity, minimum number of individuals (MNI), contextual information, dimensions, weight, percent complete, portion, conjoins and type series number. A team of volunteers recorded the artefacts on hard copy accession sheets, which were subsequently entered into the database by the author. This had the advantage of allowing for the records to be double-checked and standardised. A field for the integrity (high, medium or low) of the contextual information was included. This was to deal with doubt as to the provenance of some of the artefacts.

Phase 2: The Type Series Catalogue

Artefacts were grouped into types according to material, form, manufacturing technique, decoration and maker’s mark, or as many of these attributes as could be identified. Types were not individual vessels or objects, but rather matching vessels or objects. Size was not considered in determining types unless this implied a different function. Due to the fragmentary nature of the collection some artefacts that were potentially related have been allocated to separate types, for example bottle finishes and bases. Details of each artefact type were recorded in the type series catalogue: type number, catalogue number of the most representative artefact, function, form, sub-form, material 1 and 2, description, dimensions, quantity, MNI, total weight, processing, decorative technique, decoration, manufacturer, retailer, place of manufacture and date.

Functional classification was included in the type series catalogue to facilitate analysis. Often artefact forms are comprised of a number of material types, therefore there is an advantage in considering an assemblage as a whole, organised by function (Miller et al. 1991). The functional categories are explicitly interpretive and treated with caution. It is acknowledged that the intended function of an object is not necessarily the actual function for which it was used, and that one object may have different functions over time (Brooks 2005a:18).

The function key words used here were adapted from those recommended in Heritage Victoria’s (2004:30–35) guidelines. The Heritage Victoria key words are based on the American Getty Research Institute’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus. The application of this system has been criticised because it is a museum-based system that does not consider accepted archaeological terminology (Brooks 2005b:11). However, the Viewbank assemblage is part of Heritage Victoria’s collection and this system has been applied to other assemblages stored at Heritage Victoria. Maintaining some similarity to the system used by Heritage Victoria has value for comparing assemblages. The key words were adapted with archaeological systems consulted including Parks Canada (1992), Sprague (1981), Davies and Buckley (1987) and South (1977). Function key words were grouped under six broad activity categories (see Appendix 1).

Fragment counts, weights and minimum number of individual counts were all calculated in the type series catalogue. It is common for historical archaeologists to use at least one, and usually a combination, of these methods; therefore including all three facilitates comparison with other assemblages. MNI counts were calculated to be used for quantification. The calculation of MNI counts has become standard practice in historical archaeology (Miller 1986; Sussman 2000:96; Crook et al. 2002:30; Brooks 2005a:21–22; Lawrence 2006:380; Hayes 2011a:21). MNI counts were calculated for each type in the type series based on diagnostic features such as bases and finishes for bottles, and rim circumferences for ceramics. Where only the body fragments of an artefact were present the MNI was listed as one, regardless of weight. Throughout analysis MNI counts were recalculated, using the database where necessary to accommodate the problem of overestimating numbers. For example, the highest number of bottle bases or finishes was used for the MNI for a particular colour of glass. 22

The dating of artefacts in the type series was not carried out in order to date the site as historical records give dates for construction and occupation. Instead, dating was used to understand site formation processes and determine whether artefacts and contexts were associated with the Martin family’s occupation of the site. For example, a bottle with a start date of 1920 cannot be associated with the 1843 to 1874 occupation by the Martin family. In addition, dates were important in considering the effects of time lag. Caution must be taken due to the effect of time lag, or the difference between the date of manufacture and the date of deposition. A plate manufactured in 1860 may not have been discarded until well after the Martins left the site in 1874. A variety of factors including historical events, site location, and differences in the period of time for which artefacts were used will significantly alter time lag (Adams 2003). Dates will also be used to consider consumption issues including purchasing patterns and fashion.

Start and end dates were entered in separate database fields and contained numbers only. This was to allow for searching the database for date ranges. Where makers’ marks were present, these were given priority for dating. In other cases manufacture and decorative technique were helpful. Australian references were used in priority to overseas references when dating. In particular, this research has relied on Brooks’ (2005a) An Archaeological Guide to British Ceramics in Australia 1788–1901 for ceramics, and James Boow’s (c.1991) Early Australian Commercial Glass for glass. Where references suggested dates during which an artefact was popular, this has been added to the reference field.

The Viewbank homestead excavation is among the most significant so far conducted in Victoria. With few excavations of middle-class homes, particularly in the urban or suburban context, it has great potential to contribute information on the material culture of the middle class. The methods developed for this project draw from previous archaeological work, but have been adapted to suit the aim of this study.