5

Artefact Analysis

The assemblage recovered from the site is a substantial and fascinating example of middle-class material culture from 19th-century Melbourne. The analysis focuses first on the artefacts recovered from the tip, and then artefacts from the three homestead contexts that contained accidentally lost artefacts that may relate to the Martin family. Depositional processes are presented along with a detailed quantification and description of the assemblage by functional category.

FORMATION OF THE TIP

Artefact dates for the tip support the hypothesis of the excavation director, Leah McKenzie (2005 pers. comm.), that the tip was associated with the Martin family, and almost certainly used solely by them. Appendix 2 shows artefact start and end dates grouped into the three phases of occupation for the site: pre-Martin (1843 and earlier), Martin (1843 to 1874), and post-Martin (1875 and later). Start and end dates were allocated to artefacts based on the maker’s mark, material or manufacture process. The dates vary from a broad date range of manufacture to a tight period indicated by a maker’s mark. Artefacts were allocated to the Martin phase if the date range for the artefact overlapped with the 1843 to 1874 time period. It is acknowledged that time lag would have greatly affected the presence of artefacts on the site. Artefacts that pre-date the arrival of the Martins at Viewbank in 1843 may in fact have been objects brought to the site by the family. Similarly, those tenants who rented the premises after the Martins’ departure may have left at the site artefacts that have manufacture dates that fall within the Martin phase of occupation. The only certainty is that artefacts that have a start date post-1874 could not have belonged to the Martin family. Of the dateable artefacts, the significant majority (99.6 percent) recovered from the tip have date ranges that overlap with the Martins’ occupation of the site. Only two fragments from one object pre-dated 1843. This was an overglaze transfer-printed vessel, possibly a child’s mug. Three fragments representing two artefacts date to after the Martin family left Viewbank. A machine-made, crown seal bottle finish dating after 1920 was found in C-III-1 near the surface of the tip and two fragments of an internal thread jar dating from 1880 to 1920 were found in C-I-1.6 and C-III-2, which were deeper contexts. It is possible that these made their way into the tip during the later use of the site; for example, they may have been deposited by bottle hunters or other visitors to the site. The discovery of a 12 gauge shotgun shell suggests that shooting was taking place in the area in the 20th century.

The deposits in the tip were fairly homogeneous, with conjoining ceramics noted through all levels. Given the uniformity of the deposit it is possible that the tip represents a rapid deposition of household refuse as part of a major cleaning or site abandonment event (McCarthy and Ward 2000:113). It is possible, however, that the mixed deposits were the result of digging by bottle collectors. In addition, large numbers of complete vessels can be expected in ‘clean-out’ deposits (Crook and Murray 2004:51). About half of the ceramic tableware and teaware vessels found in the tip were part of matching sets, and although none were complete many were near complete. Parts of the Viewbank tip remain unexcavated; therefore, it is difficult to know if missing parts of near complete vessels remain. Also, the lack of complete items may be the result of the collecting practices of bottle hunters active in the area. The evidence for a ‘clean-out’ event at site abandonment is inconclusive; instead the tip may have been at least in part the result of a gradual accumulation of rubbish over a period of time.

The artefacts from the tip date from throughout the period that the Martins occupied the site, which may support the latter theory. Food scraps and disposable containers are likely to be the result of week-to-week refuse disposal (Crook and Murray 2004:51). The presence of a large number of condiment bottles, beverage bottles and food related faunal material in the Viewbank tip supports this pattern of disposal. The dates of both ceramic and glass bottles indicate that the goods were purchased over the entire period that the Martins lived at the site. This provides further evidence that the tip was used over time, however the effect of time lag on this is difficult to determine. It is likely that the Viewbank tip was used for week-to-week rubbish while the Martin family occupied the site and was also used in a site abandonment disposal event.

It is important to stress that the artefacts recovered from the tip do not represent the entirety of what the Martin family owned and used. Rather, the artefacts represent things that were broken, no longer needed or out of fashion, and subsequently discarded (Schiffer 1987:47–50). Generally, expensive goods 24that retain their value would not be discarded (Spencer-Wood 1987:14). Best sets, silverware, or valuable jewellery are unlikely to make it into the archaeological record: such items would have been kept or sold secondhand. Cutlery, metal tools and other degradable items, though discarded, may have degraded beyond the point of identification. Further, the tip was not completely excavated, and souveniring is known to have removed a number of artefacts from the site. Yet the artefacts do constitute a sample of what the Martin family used and discarded, with the assemblage representing at least some of the consumer choices of the family. Though what is absent from the assemblage can only be speculated upon, what is present can be analysed. In interpreting the assemblage, links are made between the artefacts, the reasons they were originally purchased and the ways they were used.

THE TIP ASSEMBLAGE

The assemblage recovered from the tip totalled 20,266 artefact fragments weighing 163.1 kg. For further information on artefact materials and forms see Hayes (2008). Activity and function groupings are summarised in Appendix 3 with ‘Eating and Drinking’ being the largest group. Note that all percentages given from here on are based on MNI counts.

Domestic

Artefacts in the ‘Domestic’ category are those related to life in and around the homestead. The majority of the ‘Domestic’ items were ‘Furnishings’ and ‘Ornamentation’, with a small number for ‘Maintaining the Household’ (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1: Summary of ‘Domestic’ artefacts.

| Function | Form | Qty | Weight | MNI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furnishings | cog | 1 | 2.0 | 1 |

| knob | 2 | 46.5 | 2 | |

| lamp | 2 | 46.1 | 2 | |

| lamp chimney | 175 | 370.8 | 7 | |

| lock | 5 | 137.1 | 1 | |

| Total | 185 | 602.5 | 13 | |

| Maintaining the Household | bottle | 50 | 775.7 | 1 |

| candle snuffer | 2 | 53.6 | 1 | |

| Total | 52 | 829.3 | 2 | |

| Ornamentation | figurine | 11 | 102.1 | 1 |

| flower pot | 23 | 184.4 | 4 | |

| hinge | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | |

| tassel | 4 | 1.4 | 1 | |

| unidentified | 2 | 14.4 | 1 | |

| vase | 16 | 197.1 | 2 | |

| Total | 57 | 500.0 | 10 | |

| Total | 294 | 1,931.8 | 25 |

Furnishings

A minimum number of 13 artefacts were allocated to the ‘Furnishings’ category, the majority of which were associated with kerosene lighting. Seven of the artefacts were colourless glass lamp chimneys. In addition, two copper alloy lamp pieces were recovered. The first was a copper alloy deflector from a vertical wick, kerosene lamp (TS 1107). It had an impressed maker’s mark: ‘REGISTERED/TRADEMARK/ DIETZ/ PA…’. Robert Edwin Dietz and his brother Michael patented the first flat wick burner for use with kerosene in 1859 (Kirkman 2007). The second was the central piece from what appears to be the burner of a lamp which was decorated with moulded scrolls, although the type of lamp it was from was difficult to determine (TS 730).

Other ‘Furnishing’ items included two small furniture drawer or cupboard knobs, a padlock and a cog. One was whiteware (TS 963), 31 mm in diameter, with impressed lettering: ‘N. / O’ on the reverse and the other was copper alloy (TS 955), 19 mm in diameter, with two etched bands on the obverse. An iron alloy padlock (TS 1121) may have been used to secure a chest or gate in or around the homestead. A small copper alloy cog with iron alloy pins (TS 1027) was recovered, was identical to one found in the homestead contexts and was probably a component from a clock.

Maintaining the Household

The two artefacts belonged to the ‘Maintaining the Household’ category were a poison bottle and candlesnuffer. The poison bottle (TS 35) was cobalt blue with a vertical rib pattern and had incomplete embossed lettering on the body which probably read ‘NOT TO BE TAKEN’. A copper alloy candlesnuffer (TS 1110) was also found (Figure 5.1). Candlesnuffers in the form of scissors, which trim the candlewick (or lamp wick) and collect the ashes in a box on the top blade, were common in the 18th and early 19th centuries (Woodhead et al. 1984:11).

Figure 5.1: Candlesnuffer and wick trimmer (TS 1110).

Ornamentation

A minimum number of ten artefacts from the tip were attributed to the ‘Ornamentation’ category and included flower pots, vases, a figurine, a tassel, decorative glass and a hinge. Four unglazed terracotta flowerpots were recovered from the tip. 25The pots may have been used for indoor or outdoor decoration, or possibly for growing herbs. Victorian potteries produced flowerpots, among other things, from the 1850s onwards (Ford 1995:176–293) and a variety of potted plants are identifiable in photographs of Australian interiors in the 19th century (Lawson 2004:90).

Other items would have served decorative purposes within the house. Two vases were recovered: one (TS 792) was white granite with moulded panels on the body and a scalloped rim, and the other (TS 502) was colourless glass, ovoid in section with honeycomb facets on the body and a starburst on the base. A female figurine or bust (TS 960) made from unglazed porcelain with a roughened surface to imitate marble was also a decorative item. The face had a slight smile and long hair.

Four items were components associated with decorative items. A textile and copper alloy tassel (TS 664) may have decorated a key to a wardrobe or box. The circular body of the tassel was fabric, while the threads hanging from the body were wrapped with copper alloy wire. Two purple glass disks (TS 292) with bevelled edges were recovered: one was oval and the other was a shaped rectangle. There was iron residue on the back, particularly around edges, which may indicate that the glass was mounted on a metal object such as a lamp or decorative box. Finally, a small hinge with a decorative scalloped edge (TS 1089) was possibly from a jewellery box.

Eating and Drinking

Artefacts in the ‘Eating and Drinking’ category were used in the preparation, serving and consuming of food and comprised a wide variety of forms (Table 5.2). ‘Serving and Consuming Food’ and ‘Storing Food and Drink’ were dominant in this group.

Preparing Food

A minimum of 14 artefacts from the tip were associated with ‘Preparing Food’. Six of these were bowls: one (TS 835) was made from whiteware with moulded flutes on the interior and would have been used for moulding jelly or desserts, while the remainder were large utilitarian mixing bowls. Five of the mixing bowls were made from yellowware, and one from coarse earthenware. Most commonly used for utilitarian vessels, yellowware was made in Britain, America and Australia and is usually dated to post-1830 (Brooks 2005a:34). Two of the yellowware bowls had no decoration present, one (TS 906) had moulded floral decoration on the exterior and a white glazed interior, and another (TS 909) had industrial slip annular decoration in white and blue on the exterior. Annular decorated wares were in production from c1790 to the end of the 19th century (Sussman 1997). The coarse earthenware bowl (TS 869) was decorated with moulded bands at the rim.

Table 5.2: Summary of ‘Eating and Drinking’ artefacts.

| Function | Form | Qty | Weight | MNI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparing Food | bowl | 83 | 1,090.4 | 6 |

| hourglass | 4 | 0.6 | 1 | |

| milkpan | 438 | 17,493.4 | 6 | |

| unidentified | 1 | 6.0 | 1 | |

| Total | 526 | 18,590.4 | 14 | |

| Serving and Consuming Food | bowl | 154 | 1,355.5 | 19 |

| corkscrew | 15 | 20.5 | 1 | |

| covered bowl | 4 | 26.0 | 1 | |

| cutlery | 1 | 19.3 | 1 | |

| dessert glass | 1 | 82.2 | 1 | |

| dish | 35 | 299.6 | 7 | |

| drainer | 18 | 104.8 | 3 | |

| egg cup | 7 | 28.8 | 2 | |

| fork | 1 | 15.6 | 1 | |

| jug | 5 | 178.2 | 3 | |

| knife | 1 | 29.4 | 1 | |

| ladle | 4 | 89.7 | 1 | |

| plate | 1,178 | 14,092.4 | 71 | |

| platter | 300 | 8,539.1 | 14 | |

| serving dish | 145 | 2,393.6 | 12 | |

| spoon | 5 | 18.5 | 2 | |

| stemware | 148 | 1,789.1 | 25 | |

| tablespoon | 2 | 48.6 | 1 | |

| tumbler | 305 | 3,386.5 | 13 | |

| tureen | 145 | 2,499.9 | 7 | |

| ui flat | 77 | 586.5 | 17 | |

| ui hollow | 34 | 239.0 | 12 | |

| unidentified | 265 | 640.3 | 8 | |

| Total | 2,850 | 36,483.1 | 223 | |

| Serving and Consuming Tea | jug | 43 | 98.9 | 2 |

| mug | 119 | 562.8 | 5 | |

| saucer | 574 | 3,419.2 | 41 | |

| serving dish | 4 | 8.6 | 1 | |

| teacup | 654 | 3,776.5 | 66 | |

| teapot | 3 | 66.7 | 1 | |

| ui flat | 121 | 214.9 | 4 | |

| ui hollow | 4 | 8.1 | 2 | |

| unidentified | 17 | 52.3 | 8 | |

| Total | 1,539 | 8,208.0 | 130 | |

| Serving and Consuming | covered bowl | 8 | 80.5 | 3 |

| jug | 4 | 58.8 | 1 | |

| mug | 20 | 214.8 | 2 | |

| ui flat | 857 | 4,901.4 | 43 | |

| ui hollow | 332 | 1,358.6 | 54 | |

| unidentified | 1,058 | 2,182.6 | 20 | |

| Total | 2,279 | 8,796.7 | 123 | |

| Storing Food and Drink | bottle | 7,824 | 63,438.3 | 178 |

| bottle cap | 7 | 7.5 | 3 | |

| covered bowl | 2 | 8.3 | 1 | |

| crock pot | 57 | 2,407.2 | 4 | |

| jar | 235 | 2,388.3 | 23 | |

| stopper | 15 | 507.5 | 13 | |

| ui hollow | 21 | 726.3 | 4 | |

| unidentified | 2 | 42.9 | 1 | |

| wire | 68 | 22.1 | 10 | |

| Total | 8,231 | 69,548.4 | 237 | |

| Total | 15,425 | 141,626.6 | 727 |

26In addition to the bowls, six milkpans were recovered from the tip, each with a flattened section of the rim for pouring and a flat base with no footring. A milkpan is a large vessel (more than 10 inches in diameter) shaped like an inverted, truncated cone. They were commonly used for cooling milk, cooking or as a washbasin (Beaudry et al. 2000:28). Five of the milkpans were made from redware with yellow slip-glazed interiors (TS 622 and TS 898). Brooks (2005a:42) suggests that in Australia slip-glazed coarseware vessels were probably locally made as they were becoming less popular in Britain. Vessels such as these were locally manufactured from the early days of the colony in New South Wales (Casey 1999:5), and in Victoria from the 1850s (Ford 1995:176–293). The final milkpan (TS 933) was made from undecorated whiteware and had a wide flat rim.

Two other artefacts were related to preparing food: a fine glass fragment (TS 269) which appears to be the central join of the two halves of an hourglass, possibly an egg timer, and a small copper alloy valve with a tap (TS 842) which was possibly part of a gas stove and had the lettering ‘GALAN’ on the tap. Gas stoves were invented early in the 19th century, but were not popular until the 1880s (Flanders 2003:70). Gas supply was not introduced to the Heidelberg area until 1889 (Garden 1972:168).

Serving and Consuming Food

A minimum number of 223 objects comprising 20 different forms related to ‘Serving and Consuming Food’. Four ceramic ware types were identified in the tableware assemblage from the tip (Table 5.3). A significant majority was whiteware, which is not surprising as it was the dominant ware used after 1820 for almost all table and teawares (des Fontaines 1990:4; Brooks 1999:34). The next largest group was white granite. In British and Australian contexts white granite can be dated from approximately 1845 to 1890 (Brooks 2005a:73). Porcelain was also represented, the majority of which was English hard-paste porcelain produced from 1768 (Fisher 1966:229), but Chinese porcelain was also present. There was also a small amount of bone china, which was produced from 1794 (Miller 1991:11; Brooks 2005a:72). Plates and unidentified flat vessels were made from all four ware types. Smaller items, including an eggcup, were made from porcelain, while the white granite comprised larger vessels including platters and serving dishes. All of the tableware forms identified were represented in whiteware.

Table 5.3: Ceramic tableware forms by ware type.

| Ware | Form | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone china | plate | 8 | |

| platter | 1 | ||

| ui flat | 2 | ||

| Total | 11 | 7.0 | |

| Porcelain | bowl | 3 | |

| egg cup | 1 | ||

| plate | 6 | ||

| spoon | 1 | ||

| ui flat | 3 | ||

| Total | 14 | 8.9 | |

| White granite | plate | 9 | |

| platter | 5 | ||

| serving dish | 2 | ||

| ui flat | 3 | ||

| Total | 19 | 12.1 | |

| Whiteware | bowl | 13 | |

| dish | 1 | ||

| drainer | 3 | ||

| egg cup | 1 | ||

| ladle | 1 | ||

| plate | 48 | ||

| platter | 8 | ||

| serving dish | 10 | ||

| spoon | 1 | ||

| tureen | 7 | ||

| ui flat | 9 | ||

| ui hollow | 7 | ||

| unidentified | 4 | ||

| Total | 113 | 72.0 | |

| Total | 157 | 100.0 |

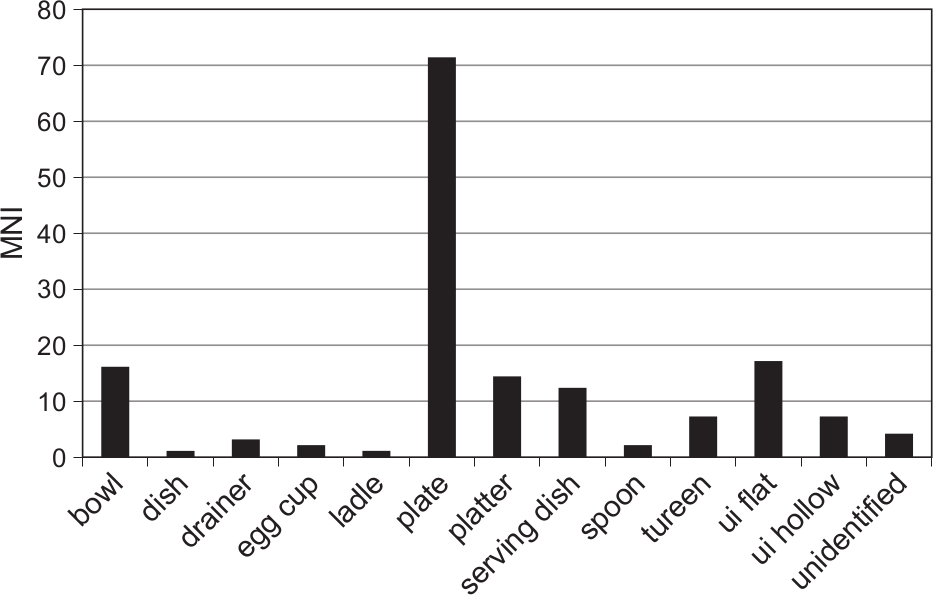

Figure 5.2: Ceramic tableware forms.

A wide range of artefact forms were identified within the ceramic tableware assemblage (Figure 5.2). Plates were the dominant form comprising 45.2 percent of the dining tableware in the tip assemblage. Staffordshire potteries used standard plate sizes: table plate (10-inch), supper plate (9-inch), twiffler (8-inch) and muffin (3 to 7-inch) (Miller 2000:96). Manufacturers did not strictly follow the sizes and often circumvented price fixing for vessel forms by producing plates between these sizes (Ewins 1997:131; Miller 2000:96). In this analysis, plates have been categorised in the closest inch measurement even if the size varied slightly from 27this diameter. Many of the plates, 33.8 percent, had insufficient rim fragments to determine the size. The 10-inch or table plate was the most common, closely followed by the 9-inch supper plate and 8-inch twiffler. A smaller number of soup plates and 7-inch muffin plates were represented. The larger plates would have been used for dining while the smaller plates may have been used as side or dessert plates or possibly as part of a tea service.

The next most prevalent vessel form was the bowl, while platters, serving dishes and tureens followed. Six of the tureens were soup tureens; however one (TS 754) was a smaller sauce tureen. A number of specific-use forms were also identified. These included drainers, spoons, eggcups, a dish and a ladle. Drainers had holes in the base and usually sat inside another vessel to serve boiled fish or meat, allowing the juices to drain (Coysh and Henrywood 1989:115). One of the spoons was a Chinese spoon (TS 584), while the other (TS 697) was the handle of a spoon or ladle probably for serving sauce or condiments. For the tip, 17.8 percent of the tableware was unidentified, unidentified flat and unidentified hollow, but could be related to serving and consuming food. This was based on the appearance of the vessel, or the object being part of a matching set of tableware.

Table 5.4: Decorative techniques on ceramic tableware.

| Decorative Technique | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|

| Flow (transfer-printed black) | 2 | |

| Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 20 | |

| Total Flow | 22 | 14.0 |

| Gilded | 15 | |

| Total Gilded | 15 | 9.6 |

| Coloured glazed | 1 | |

| Total Glazed | 1 | 0.6 |

| Moulded | 24 | |

| Moulded (relief) | 1 | |

| Total Moulded | 25 | 15.9 |

| Flow (Transfer-printed blue)/enamelled | 2 | |

| Gilded/enamelled | 5 | |

| Moulded/enamelled/gilded | 1 | |

| Moulded/gilded | 11 | |

| Moulded/transfer-printed (blue) | 8 | |

| Relief/decal Transfer-printed (black)/enamelled | 16 | |

| Total Multiple techniques | 43 | 27.4 |

| Transfer-printed (blue) | 19 | |

| Transfer-printed (green) | 2 | |

| Transfer-printed (grey) | 5 | |

| Transfer-printed (purple) | 1 | |

| Total Transfer-printed | 27 | 17.2 |

| None present | 16 | |

| Total None present | 16 | 10.2 |

| Undecorated | 7 | |

| Total Undecorated | 7 | 4.5 |

| Unidentified | 1 | |

| Total Unidentified | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 157 | 100.0 |

A large number of decorative techniques and combinations of techniques were present within the tableware assemblage (Table 5.4). Only a small number of the vessels were undecorated; that is, they were complete enough to determine that there was no decoration. A slightly larger number were fragments with no decoration present and may have been decorated or undecorated.

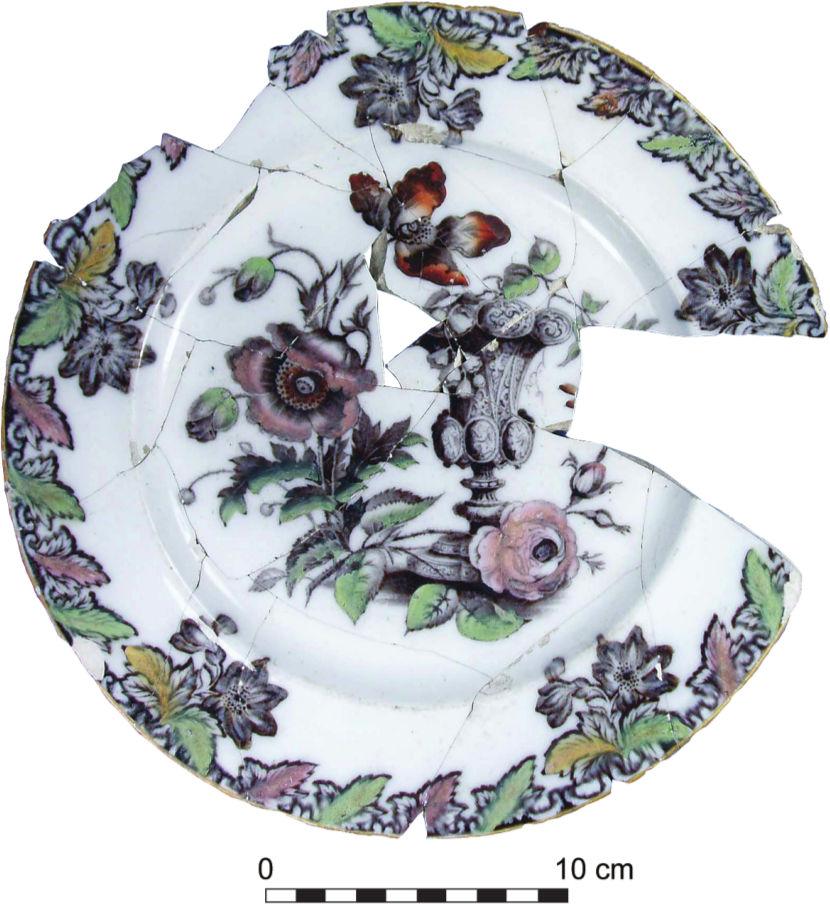

Vessels decorated with a combination of multiple techniques were the most common decorative type. Notable among these were 16 vessels decorated with the ‘Summer Flowers’ pattern made by Samuel Alcock & Co., who operated in Staffordshire from 1830 to 1859 (Godden 1964:28). This was a flown black transfer-printed pattern with polychrome enamelled and gilded detail (Figure 5.3).

A further 11 vessels were both moulded and gilded, and had either banded or floral decoration. Moulded body and blue transfer-printed decoration were combined on eight vessels. These included three vessels decorated with a scalloped rim and the ‘Asiatic Pheasants’ pattern (TS 729, 746 and 753). ‘Asiatic Pheasants’ was one of the most commonly produced floral decorations in the 19th century (Samford 2000:69, 73). There was also a matching set of three Chinese pattern blue transfer-print plates with scalloped rims (TS 346 and 547). One of the plates had a back mark revealing that it was made by Masons, a Staffordshire pottery operating between 1820 and 1854 (Godden 1964:416–418; Coysh and Henrywood 1989:239–241). Two vessels had moulded rims combined with transfer prints in unique patterns.

Figure 5.3: ‘Summer Flowers’ plate (TS 421).

28Other multiple decoration combinations included five vessels with a combination of gilt and enamel including two Chinese export porcelain bowls, two vessels with a flown transfer print and enamel detail, and a moulded, gilt and enamelled plate.

Following multiple techniques, transfer prints were the most common technique of decoration on the tableware. Of the transfer-printed ceramics recovered from the tip, 70.4 percent were blue transfers, 18.5 percent were grey, 7.4 percent were green, and one vessel was purple. While blue transfer prints date from around 1780, other colours were introduced around 1828 (Brooks 2005a:43). For the transfer-printed tableware, 28.6 percent had unidentified patterns (Table 5.5). The largest identified group was ‘Willow’ pattern, representing 25 percent of the ceramic tableware. This reflects the popularity of the Chinese inspired ‘Willow’ pattern, which was introduced by Josiah Spode around 1790 and subsequently produced by many different potters to this day (Samford 2000:63). The next most popular pattern at Viewbank was the ‘Rhine’ romantic scene. Other romantic scenes were also represented which depict landscapes usually with mountains, trees, waterfalls, castles, a body of water and small human figures. Romantic scenes were generated by the Romantic Movement in Europe and reflected the view that humans were subordinate to the forces of nature (Samford 2000:68–69). Samford (2000:69) suggests that they peaked in popularity in the United States between 1831 and 1851. Various floral decorations were present on three vessels which varied from each other. Floral decorations were popular throughout the 19th century (Samford 2000:73). One plate (TS 639) was decorated with a classical scene, including flowers and an urn with draped figures. The design also included a vignette on the rim with cartouches enclosing flowers. Classical designs inspired by archaeological excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum were particularly popular from 1827 to 1847 (Samford 2000:67–68).

Table 5.5: Transfer-printed decoration types on ceramic tableware.

| Decoration | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Scene | 1 | 3.6 |

| Floral | 3 | 10.7 |

| Rhine | 6 | 21.4 |

| Romantic Scene | 3 | 10.7 |

| Willow | 7 | 25.0 |

| Unidentified transfer print | 8 | 28.6 |

| Total | 28 | 100.0 |

A minimum number of 24 vessels with moulded decoration alone were recovered from the tip. Of these, 75 percent were white granite, a ware type characterised by its moulded decoration. ‘Berlin Swirl’ and ‘Girard Shape’, which are common white granite decorative styles, represent 29.2 percent each of the moulded vessels. Five ‘Girard Shape’ plates were made by John Ridgway Bates & Co. between 1856 and 1858 in Staffordshire (Godden 1964:535). Two of the ‘Berlin Swirl’ vessels were made by Mayer & Elliot, a Staffordshire pottery, and were impressed with the date 1860 (Godden 1964:422). Another two were made by Liddle, Elliot & Son who began operations under that name in 1862 (Godden 1964:235). White granite vessels with moulded bands on the rim, fluted face, or floral decoration were also represented. The moulded whiteware vessels had floral, banded, or fluted decoration.

Figure 5.4: ‘Bagdad’ pattern plate (TS 798).

Of the flown transfer-printed tableware recovered from the tip, 90 percent was blue and 10 percent black. A matching set of ‘Queen’s’ pattern vessels represented 40 percent of the flown tableware and was made by Pinder, Bourne & Hope, of Staffordshire between 1851 to 1862 (Godden 1964:495). Further, six different floral patterns were identified representing 30 percent of the flown tableware. Three plates decorated with a flown floral and geometric pattern named ‘Bagdad’ [sic], also made by Pinder, Bourne & Hope were recovered (Figure 5.4). Also, two plates were decorated with a pattern of bluebells and leaves named ‘Clematis’, but the maker for this pattern could not be identified.

Other decorative techniques were represented in smaller numbers. Of the 15 gilded tableware vessels, all were banded. These vessels were plates, a drainer and unidentified forms in bone china and porcelain. A Chinese porcelain spoon (TS 584) recovered from the tip was decorated with a green ‘Celadon’ glaze. ‘Celadon’ is often found on overseas Chinese archaeological sites (Hellman and Yang 1997:156). This type of spoon was a fairly cheap Kitchen Ch’ing item, made for the Chinese market, both domestic and overseas (Muir 2003:43). Its presence at a middle-class site with no Chinese 29occupation is unusual: it may have been an exotic curiosity. Undecorated vessels represented 4.5 percent of the tableware assemblage. These included plates, a bowl and a serving dish. This is a fairly low percentage, indicating a preference for decorated vessels. However, it must be considered that vessel fragments with no decoration present may have in fact been undecorated.

Table 5.6: Makers’ marks on ceramic tableware.

| Manufacturer | Makers’ Mark | Place of Manufacture | MNI | Start Date | End Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G.M. & C.J. Mason/Charles James Mason | ‘MASONS’ above a crown/ ‘PATENT IR[ONSTONE/CHINA]’. | England - Staffordshire | 1 | 1820 | 1854 |

| John Ridgway Bates & Co. | Garter mark with crown and lettering ‘J. RIDGWAY BATES & CO. CAULDON PLACE/ GIRARD SHAPE’. | England - Staffordshire | 5 | 1856 | 1858 |

| Liddle, Elliot & Son | ‘BERLIN IRONSTONE/ Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense/ LIDDLE ELLIOT & SON’ with the Royal Arms. Part of a diamond registration mark on one fragment and impressed ‘NS’. | England - Staffordshire | 2 | 1862 | 1871 |

| Mayer & Elliot | ‘BERLIN IRONSTONE/ Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense/ MAYER & ELLIOT’ with the Royal Arms and diamond registration mark. Impressed: ‘10/60’ indicating manufacture date. | England - Staffordshire | 2 | 1860 | 1860 |

| Pinder, Bourne & Hope | ‘QUEENS PATTERN [also BAGDAD PATTERN]/ P.B. & H.’ in a circle with a wreath and crown. | England - Staffordshire | 6 | 1851 | 1862 |

| Samuel Alcock & Co. | ‘SUMMER FLOWERS/ S A & Co’ inside a wreath of flowers. | England - Staffordshire | 11 | 1830 | 1859 |

| Thomas, Isaac & James Emberton | ‘RHINE’ inside a cartouche with ‘T.I. & J.E.’ below. | England - Staffordshire | 1 | 1869 | 1882 |

| Unknown | None Present | 129 | |||

| Total | 157 |

Only 17.8 percent of the tableware had a maker’s mark (Table 5.6). All of the identified manufacturers were Staffordshire potteries with date ranges from 1828 to 1882.

There were at least 11 matching sets (Table 5.7) and three complementary sets (Table 5.8) of tableware in the Viewbank assemblage. That is, 38.6 percent of the vessels were part of a matching set, with a further 23.4 percent part of a complementary set. For the purposes of this study matching sets were determined where two or more vessels of an identical pattern were identified. The largest set was ‘Summer Flowers’ with 16 vessels, followed by the ‘Queen’s’ pattern set with ten vessels. The ‘Berlin Swirl’ and ‘Girard Shape’ white granite sets were also sizeable. A further 37 vessels may have been used as complementary vessels, giving the appearance of being sets without actually matching, including a large number of gilt banded vessels, ‘Willow’ vessels and undecorated vessels. Also, two banded white granite serving vessels were possibly used as complementary vessels to the white granite sets.

Sixty glass tableware items were recovered from the tip incorporating seven vessel forms (Table 5.9), predominantly drinking glasses. There were a minimum of 25 stemmed glasses with bowl shapes including round funnel, bucket and ovoid. At least nine of the glasses had a knop on the stem, including baluster, annular and bladed shapes. It was difficult to determine whether different decorative techniques were used on the base, stem and bowl, and how many of the glasses had some decoration present because the stemware was in highly fragmentary condition. Cut glass decoration was present on the bowls of most of the stemware. The patterns on the Viewbank stemware included cut panels, facets or flutes and alternating facets and flutes on the bodies and stems which were common decorations for 19th-century glassware (Jones 2000:174).

A minimum of 13 tumblers were recovered, far fewer than the stemmed glasses. As with the stemware, the majority of tumblers from the tip had cut decoration in panels, flutes, or alternating flutes, panels or mitres. Panels were the most common decorative motif on tumblers in the 19th century (Jones 2000:225) and were also the most common in the Viewbank tip assemblage. A minimum of two tumblers had similar decoration, but were moulded, not cut. From the 1790s, contact-moulded and pressed imitations of cut glass were a common and cheaper alternative (Jones 2000:174). Five of the tumbler bases featured a star or sunburst.

Thirteen glass vessels related to serving food were recovered, six of which were small serving dishes. Four of these (TS 161, 186, 299, and 383) were green and press-moulded with different 30detailed patterns on the exteriors. A yellow dish (TS 327) was also press-moulded with a diamond pattern. The sixth vessel was a colourless, cut glass dish (TS 524) with a scalloped rim, panelled body and a sunburst on the base. There were also three colourless, press-moulded, bowls (TS 534, 543 and 310), a small colourless glass jug (TS 491) with moulded diamonds on the body, two undecorated, colourless glass jug handles, a covered bowl (TS 523) with ovoid facets on the body, and a stemmed colourless dessert glass (TS 541) with a bladed knop. Further, there were eight unidentified glass vessels attributed to the ‘Serving and Consuming Food’ category most of which were body fragments that are likely to be from one of the artefacts discussed above.

Table 5.7: Matching sets of ceramic tableware.

| Set Name | Type of Set | Type of Decoration | Form | MNI | Type Series Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagdad | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 9-inch plate | 3 | 798 |

| Clematis | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 8-inch plate | 2 | 783 |

| Floral | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 8-inch plate | 2 | 769 |

| Queen’s | Serving and Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | side plate | 1 | 761 |

| plate | 3 | 756 | |||

| platter | 2 | 766 | |||

| ladle | 1 | 750 | |||

| serving dish | 1 | 751 | |||

| tureen | 1 | 754 | |||

| ui hollow | 1 | 758 | |||

| Berlin Swirl | Serving and Consuming | Moulded (white granite) | 10-inch plate | 2 | 935 |

| platter | 2 | 1135 | |||

| platter | 2 | 672 | |||

| ui flat | 1 | 1136 | |||

| Girard Shape | Serving and Consuming | Moulded (white granite) | plate | 5 | 985 |

| serving dish | 1 | 1006 | |||

| soup plate | 1 | 992 | |||

| Banded | Serving | Moulded (white granite) | serving dish | 1 | 656 |

| platter | 1 | 1001 | |||

| Asiatic Pheasants | Serving and Consuming | Moulded/transfer-printed (blue) | 10-inch plate | 1 | 753 |

| platter | 1 | 746 | |||

| bowl | 1 | 729 | |||

| Masons Chinese | Consuming | Moulded/transfer-printed (blue) | 10-inch plate | 2 | 346 |

| 9-inch plate | 1 | 547 | |||

| Summer Flowers | Serving and Consuming | Transfer-printed (black)/enamelled | 10-inch plate | 4 | 421 |

| 9-inch plate | 1 | 369 | |||

| 7-inch plate | 3 | 422 | |||

| soup plate | 2 | 424 | |||

| plate | 1 | 293 | |||

| tureen | 2 | 631 | |||

| meat warmer | 1 | 632 | |||

| ui hollow | 1 | 473 | |||

| ui hollow | 1 | 630 | |||

| Rhine | Serving and Consuming | Transfer-printed (grey) | 10-inch plate | 1 | 718 |

| 8-inch plate | 1 | 721 | |||

| soup plate | 1 | 725 | |||

| platter | 1 | 724 | |||

| ui hollow | 1 | 727 | |||

| unidentified | 1 | 735 | |||

| Total | 61 | 31 |

Table 5.8: Complementary tableware vessels.

| Set Name | Type of Set | Type of Decoration | Form | MNI | Type Series Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banded | Serving and Consuming | Gilded (whiteware) | drainer | 1 | 612 |

| plate | 1 | 839 | |||

| unidentified | 1 | 592 | |||

| Gilded (bone china) | 9-inch plate | 2 | 879 | ||

| plate | 2 | 580 | |||

| ui flat | 2 | 888 | |||

| Gilded (porcelain) | 10-inch plate | 1 | 878 | ||

| 9-inch plate | 1 | 117 | |||

| 8-inch plate | 2 | 891 | |||

| ui flat | 2 | 129 | |||

| Moulded/gilded (whiteware) | plate | 2 | 886 and 948 | ||

| 10-inch plate | 3 | 825 | |||

| 9-inch plate | 1 | 840 | |||

| tureen (soup) | 1 | 841 | |||

| Moulded/gilded (bone china) | plate | 1 | 579 | ||

| Willow | Serving and Consuming | Transfer-printed (blue) | 9-inch plate | 3 | 722 |

| 8-inch plate | 1 | 720 | |||

| platter | 1 | 714 | |||

| serving dish | 1 | 715 | |||

| ui flat | 1 | 726 | |||

| Undecorated | Serving and Consuming | (whiteware) (two variations) | plate | 2 | 973 |

| (whiteware) | 9-inch plate | 1 | 931 | ||

| (whiteware) | bowl | 1 | 916 | ||

| (whiteware) | serving dish | 2 | 927 | ||

| (bone china) | 8-inch plate | 1 | 591 | ||

| Total | 37 |

Table 5.9: Glass tableware forms by glass colour.

| Colour | Form | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colourless | bowl | 3 | |

| covered bowl | 1 | ||

| dessert glass | 1 | ||

| dish | 1 | ||

| jug | 3 | ||

| stemware | 25 | ||

| tumbler | 13 | ||

| ui hollow | 5 | ||

| unidentified | 3 | ||

| Total | 55 | 91.7 | |

| Green | dish | 4 | |

| Total | 4 | 6.7 | |

| Yellow | dish | 1 | |

| Total | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Total | 60 | 100.0 |

Five cutlery items were recovered from the tip. A four-tang fork (TS 776) was copper alloy and appears to have been electroplated with silver, a technique introduced and patented by George Richards and Henry Elkington in 1840 (Chadwick 1958:633). A large tablespoon in the ‘Fiddle’ design (TS 669) was recovered and was copper alloy with silver plating. Impressed lettering on the reverse handle reads ‘BP’ with further illegible lettering. ‘BP’ stands for British Plate, a form of nickel silver (Woodhead 1991:33). The handle of a piece of nickel alloy cutlery (TS 1080) in the ‘Fiddle’ design had impressed lettering on the reverse of the handle, but this was illegible. Nickel silver was introduced in 1824, but became more popular after the introduction of electroplating (Chadwick 1958:608). A carbon steel knife with a scale tang (TS 1118) would have had a bone, horn or wood handle. The scale tang was generally used for kitchen cutlery (Moore 1995:28). The invention of the Bessemer converter in 1856 led to the mass production of carbon steel cutlery. For those who could afford it, blades were close-plated with silver to prevent the carbon steel from affecting the taste of food (Moore 1995:29). Type 1069, although recorded as unidentified, was probably the rectangular bone handle of a knife. In addition, a small flat non-ferrous metal handle (TS 1075) with moulded decoration may have been a mustard or condiment spoon. 32

The final item in the ‘Serving and Consuming Food’ category was a corkscrew with a cylindrical wooden handle (TS 778). The handle was decorated with lathe-turned bands and had a screw-in cap at one end. This handle is typical of the Thomason corkscrew. This corkscrew was invented by Sir Edward Thomason, and patented in England in 1802. Thomason corkscrews often bore the British Royal Arms (Borrett 2007).

Serving and Consuming Tea

One hundred and thirty artefacts were related to ‘Serving and Consuming Tea’ and were exclusively ceramic teawares (Table 5.10). The majority of the ceramic teawares were teacups, representing 50.8 percent of the total. Saucers followed, representing 31.5 percent. Vessels identified as saucers were those that were flat to shallow, hollow and lacking a marly. The presence of a cup well was not considered to be necessary for diagnosis as a saucer. It is noted that saucers may have been used for a variety of functions (Brooks 2005a:51), but they were included with the teawares as this was considered to be their most likely function. A small number of mugs, a jug, a teapot and a serving dish were also identified.

Table 5.10: Ceramic teaware forms by ware type.

| Ware | Form | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone china | mug | 1 | |

| saucer | 14 | ||

| teacup | 41 | ||

| unidentified | 7 | ||

| Total | 63 | 48.5 | |

| Porcelain | saucer | 4 | |

| teacup | 5 | ||

| jug | 1 | ||

| ui flat | 3 | ||

| ui hollow | 2 | ||

| Total | 15 | 11.5 | |

| Redware | teapot | 1 | |

| Total | 1 | 0.8 | |

| White granite | saucer | 4 | |

| teacup | 9 | ||

| Total | 13 | 10.0 | |

| Whiteware | saucer | 19 | |

| teacup | 11 | ||

| mug | 4 | ||

| jug | 1 | ||

| serving dish | 1 | ||

| ui flat | 1 | ||

| unidentified | 1 | ||

| Total | 38 | 29.2 | |

| Total | 130 | 100.0 |

Table 5.11: Decorative techniques on ceramic teaware.

| Decorative Technique | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|

| Enamelled | 4 | |

| Total Enamelled | 4 | 3.1 |

| Flow (transfer-printed black) | 1 | |

| Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 8 | |

| Flow (transfer-printed purple) | 5 | |

| Total Flow | 14 | 10.8 |

| Gilded | 30 | |

| Total Gilded | 30 | 23.1 |

| Glazed | 1 | |

| Total Glazed | 1 | 0.8 |

| Hand-painted | 5 | |

| Total Hand-painted | 5 | 3.8 |

| Moulded | 17 | |

| Moulded (relief) | 5 | |

| Total Moulded | 22 | 16.9 |

| Flow (transfer-printed blue)/enameled | 3 | |

| Gilded/enameled | 6 | |

| Moulded/gilded | 16 | |

| Total Multiple techniques | 25 | 19.2 |

| Sponged | 1 | |

| Total Sponged | 1 | 0.8 |

| Transfer-printed (blue) | 4 | |

| Transfer-printed (purple) | 10 | |

| Total Transfer-printed | 14 | 10.8 |

| None present | 10 | |

| Total None present | 10 | 7.7 |

| Undecorated | 4 | |

| Total Undecorated | 4 | 3.1 |

| Total | 130 | 100.0 |

Nine decorative techniques were identified for the ceramic teawares (Table 5.11). The predominant decorative technique was gilding: 56.7 percent of the gilded teawares were banded, 40 percent were decorated with the popular ‘Tea leaf’ design, and one vessel had a floral decoration. Vessels with moulded decoration were the next most dominant group in the teawares. The majority (40.9 percent) of the moulded teawares were white granite ‘Berlin Swirl’ teacups and saucers. There were also five bone china teacups with panelled bodies, a panelled porcelain saucer, a fluted bone china saucer, and bone china teacups and saucers with ‘Sprigged’ (applied blue) grape motifs which date to post-1820 (Brooks 2005a:43).

Multiple decorative techniques were used on 19.8 percent of the teawares and most of these had moulded bodies with gilt bands. Three saucers (TS 173 and TS 575) had panelled bodies and a gilt ‘Tea leaf’ in the centre. A cup (TS 620) and matching saucers (TS 641) with a flown floral transfer print in blue with enamelled detail were recovered, along with a moulded and enamelled banded hollow vessel and a gilded and enamelled banded teacup.33

Fourteen teaware vessels from the tip had flown transfer prints. Of these, 11 teacups and saucers were decorated with a ‘Marble’ pattern in blue, purple or black. The ‘Marble’ pattern is a design which imitates the surface of marble. The remaining two vessels were saucers decorated with a floral pattern identified as ‘Florentine’ by the maker’s mark. This appears to be a sheet pattern where the pattern covers the whole vessel without a different rim decoration. According to Samford (2000:73), sheet patterns were most commonly produced between 1826 and 1842.

Only 14 of the teaware vessels from the tip were transfer-printed alone. Of particular note was a matching set of purple vessels with a geometric ribbon pattern (TS 775, 741, 733, 743 and 793). Also, a matching teacup (TS 732) and saucer (TS 742) were decorated with a purple fern pattern, and a mug (TS 519) was decorated with a blue romantic scene, while the remainder had unidentified patterns.

A number of the teaware vessels were handpainted. Three saucers and two teacups had handpainted, banded decoration in red, blue or green. Hand-painted, stand-alone banded vessels have been dated to post-1860 (Majewski and O’Brien 1987:161). Two vessels (TS 540 and 244) were decorated with a red band on the rim and a red and green spot and leaf design on the body. Another, possibly matching, teacup (TS 572) and saucer (TS 257) set was decorated with a lustre enamel floral pattern. Lustre is a reflective metallic decoration which dates from approximately 1790 to 1850 (Brooks 2005a:40, 72). Also, a teacup handle (TS 188) appears to be decorated with spatter blue, but it was only a small fragment. A refined redware teapot lid (TS 905) with a ‘Rockingham’ type glaze was also found. Finally, four teaware vessels from the tip were undecorated, while a further ten vessels from the tip had no decoration present.

Only three vessels, or 2.5 percent of the teaware from the tip, had makers’ marks. Two saucers (TS 987) were made between 1862 and 1871 by the Staffordshire pottery Liddle Elliot and Son and matches marks on the tableware. In addition, a saucer decorated with ‘Marble’ pattern (TS 790) was impressed with ‘BB’ on the base. This was probably the Minton mark meaning ‘Best Body’ used on mid-19th-century earthenwares (Godden 1964:441). Another two saucers (TS 661 and 999) had illegible impressed marks on their bases.

Table 5.12: Matching sets of ceramic teaware in order of set size.

| Set Name | Type of Set | Type of Decoration | Form | MNI | Type Series Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin Swirl | Consuming | Moulded | saucer | 3 | 987 and 970 |

| teacup | 6 | 969 | |||

| Marble | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | saucer | 2 | 790 |

| teacup | 1 | 822 | |||

| Marble | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed purple) | saucer | 3 | 654 |

| teacup | 2 | 658 | |||

| Banded | Serving and Consuming | Gilded/Enamelled (blue) | teacup | 1 | 141 |

| jug | 1 | 215 | |||

| ui flat | 3 | 190 | |||

| ui hollow | 1 | 233 | |||

| Geometric | Serving and Consuming | Transfer-printed (purple) | saucer | 1 | 775 |

| jug | 1 | 741 | |||

| serving dish | 1 | 733 | |||

| unidentified | 1 | 793 | |||

| ui flat | 1 | 743 | |||

| Sprigged | Consuming | Moulded (relief) | saucer | 2 | 570 |

| teacup | 2 | 569 | |||

| Unidentified Floral | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue)/enamelled | saucer | 2 | 641 |

| teacup | 1 | 620 | |||

| Unidentified Transfer Print | Consuming | Transfer-printed (purple) | saucer | 2 | 712 |

| teacup | 1 | 711 | |||

| Florentine | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | saucer | 2 | 820 |

| Total | 40 |

Of the teaware, 31.7 percent of the vessels were part of a matching set (Table 5.12), with a further 41.3 percent being part of a complementary set (Table 5.13). There were at least nine matching sets of teaware, comprising 40 vessels, recovered 34from the tip. Matching sets were determined where two or more vessels of an identical pattern were identified. A cup and saucer were considered to be one vessel for this purpose, so either two cups or two saucers needed to be identified as matching. In most cases the sets were represented by small numbers. The largest set in the teaware assemblage was of white granite, ‘Berlin Swirl’. This was also the only set to have tableware and teaware vessels. Only two of the teaware sets included vessels for serving tea in addition to those for consuming tea. A further 52 vessels may have formed part of complementary sets, giving the appearance of a set without actually matching. The ‘Marble’ pattern vessels listed as complementary vessels may have been used with the two matching sets of ‘Marble’ vessels. Similarly, the panelled, ‘Sprigged’ teacup may have been used with the ‘Sprigged’ set.

Table 5.13: Complementary teaware vessels.

| Set Name | Type of Set | Type of Decoration | Form | MNI | Type Series Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banded | Consuming | Gilded (bone china) (three variations) | teacup | 14 | 221 |

| Gilded (porcelain) | saucer | 1 | 896 | ||

| Gilded (porcelain) | teacup | 2 | 271 and 566 | ||

| Gilded/Moulded (bone china) (three variations) | saucer | 5 | 245 and 599 | ||

| Gilded/Moulded (bone china) (two variations) | teacup | 6 | 583 | ||

| Gilded/Moulded (porcelain) | saucer | 1 | 578 | ||

| Tea leaf | Consuming | Gilded (bone china) | saucer | 1 | 575 |

| Gilded (bone china) (three variations) | teacup | 6 | 560 | ||

| Gilded (bone china) | unidentified | 6 | 586 | ||

| Gilded/Moulded (panelled) | saucer | 2 | 173 | ||

| Undecorated | Consuming | (white granite) | saucer | 1 | 999 |

| (white granite) | teacup | 3 | 1002 | ||

| Marble | Consuming | Flow (transfer-printed blue) | saucer | 1 | 661 |

| teacup | 1 | 659 | |||

| Flow (transfer-printed black) | saucer | 1 | 784 | ||

| Sprigged | Consuming | Moulded (relief)/Panelled | teacup | 1 | 234 |

| Total | 52 |

Serving and Consuming

A minimum number of 123 vessels were related to ‘Serving and Consuming’, but either the fragmentary nature or the form made it difficult to relate them to either food or tea service. All of the ‘Serving and Consuming’ artefacts were ceramic vessels. Whiteware was the most common ceramic ware type in the ‘Serving and Consuming’ category (Table 5.14). The vast majority of vessels (95.1 percent) in the ‘Serving and Consuming’ category were unidentified hollow, unidentified flat and unidentified. The identified vessel forms included two children’s mugs that may have been used for tea or other beverages, three covered bowls that may have been for sugar or condiments, and a jug that may have been for serving milk with tea, or for gravy or sauces.

Table 5.14: ‘Serving and Consuming’ vessel forms by ware type.

| Ware | Form | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone china | mug | 2 | |

| ui flat | 3 | ||

| ui hollow | 8 | ||

| unidentified | 1 | ||

| Total | 14 | 11.4 | |

| Buff-bodied earthenware | ui hollow | 2 | |

| Total | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Porcelain | ui flat | 4 | |

| ui hollow | 5 | ||

| unidentified | 1 | ||

| Total | 10 | 8.1 | |

| White granite | jug | 1 | |

| ui flat | 6 | ||

| ui hollow | 5 | ||

| unidentified | 5 | ||

| Total | 17 | 13.8 | |

| Whiteware | covered bowl | 3 | |

| ui flat | 30 | ||

| ui hollow | 34 | ||

| unidentified | 13 | ||

| Total | 80 | 65.0 | |

| Total | 123 | 100.0 |

‘Moralising china’ is a term used by archaeologists for tableware, specifically for children, which have educational or moral phrases and decoration (Karskens 1999:141). Two such children’s mugs 35with moulded and gilded bands were found in the Viewbank tip. Gilt lettering on the body of one (TS 577) read: ‘A Pres… for// A good…’. Mugs with the phrase ‘A present for a good girl [boy]’ were for rewarding good behaviour (Karskens 1999:141). The other (TS 588) had ‘Robert’ in gilt lettering and probably belonged to Dr and Mrs Martin’s son, Robert (usually known as Willy) (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5: Robert’s mug (TS 588).

Table 5.15: Decorative techniques on ‘Serving and Consuming’ ceramics.

| Decorative Technique | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|

| Enamelled | 5 | |

| Total Enamelled | 5 | 4.1 |

| Flow (transfer-printed black) | 4 | |

| Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 9 | |

| Total Flow | 13 | 10.6 |

| Gilded | 6 | |

| Total Gilded | 6 | 4.9 |

| Glazed | 1 | |

| Total Glazed | 1 | 0.8 |

| Hand-painted | 2 | |

| Total Hand-painted | 2 | 1.6 |

| Moulded | 5 | |

| Moulded (relief) | 1 | |

| Total Moulded | 6 | 4.9 |

| Gilded/enamelled | 1 | |

| Moulded/Flow (transfer-printed blue) | 1 | |

| Moulded/gilded | 5 | |

| Moulded/glazed | 1 | |

| Moulded/transfer-printed | 1 | |

| Transfer-printed (green)/enamelled | 1 | |

| Total Multiple techniques | 10 | 8.1 |

| Transfer-printed (black) | 2 | |

| Transfer-printed (blue) | 13 | |

| Transfer-printed (green) | 3 | |

| Transfer-printed (grey) | 1 | |

| Transfer-printed (purple) | 6 | |

| Total Transfer-printed | 25 | 20.3 |

| None present | 55 | |

| Total None present | 55 | 44.7 |

| Total | 123 | 100.0 |

Table 5.16: Makers’ marks on ‘Serving and Consuming’ ceramics.

| Manufacturer | Maker’s Mark | Place of Manufacture | MNI | Start Date | End Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liddle, Elliot & Son | ‘BERLIN IRONSTONE/ Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense/ LIDDLE ELLIOT & SON’ with the Royal Arms. | England - Staffordshire | 2 | 1862 | 1871 |

| Pinder, Bourne & Co. | ‘HONI SOIT QUI MAL Y PENSE/ DIEU ET MON DROIT/ STONE CHINA/ PINDER BOURNE & CO/ BURSLEM’ with the Royal Arms. | England - Staffordshire | 1 | 1862 | 1882 |

| Pinder, Bourne & Hope or Pinder, Bourne & Co. | ‘STO…/ PINDER…/ BUR…’ and part of a diamond registration mark. | England - Staffordshire | 1 | 1851 | 1882 |

| Unidentified | ‘MADE IN ENGLAND’ | 1 | 1805 | present | |

| Unidentified | ‘IRON…’ | 1 | 1845 | 1890 | |

| None present | None present | 121 | |||

| Total | 127 |

A high number of vessels in the ‘Serving and Consuming’ category had no decoration present (Table 5.15). This was in part because many of the vessels in this category were fragmentary body parts which are less likely to have decoration present. Of the ‘Serving and Consuming’ ceramics, 20.3 percent were transfer-printed in blue, purple, green, black or grey. Unidentified prints and floral prints were the most frequent, with geometric designs one fragment with ‘Rhine’ pattern also found. The next largest decorative group comprised 36multiple decorative techniques most of which were moulded with a second decorative technique, most often banded. One hollow vessel (TS 911), probably a teapot, was decorated with a moulded pattern and a ‘Rockingham’ type glaze. ‘Rockingham’ glazed vessels were made both in Britain and Australia (Brooks 2005a:41). About half of the flown vessels had floral decoration, while the rest were unidentified. Also, five gilded banded vessels were recovered and one with a gilded geometric pattern. Another five vessels had moulded decoration: two were ‘Berlin Swirl’ and one was floral. A blue ‘Sprigged’ vessel was included in this category. Three vessels had enamelled floral decoration and two had enamelled banded decoration. There was also a hand-painted floral covered bowl and a hand-painted banded vessel. Finally, a buff-bodied earthenware vessel, possibly a teapot, was decorated with ‘Rockingham’ type glaze alone.

Makers’ marks were present on 6 percent of the ‘Serving and Consuming’ ceramics in the tip (Table 5.16). As with the tableware and teaware, all of the identified makers’ marks were from Staffordshire potteries. Three items had the British diamond registration mark. The marks indicate date ranges from 1845 to 1882. One partial maker’s mark (TS 940) read ‘MADE IN ENGLAND’. This term was usually found on 20th century English marks (Godden 1964:407).

Storing Food and Drink

The ‘Storing Food and Drink’ category includes bottles, jars and other vessels related to the storing of food and beverages. A minimum number of 237 artefacts were classified in this category, of which 177 were glass storage bottles. Alcohol bottles types have been included under ‘Storing Food and Drink’ as it cannot be assumed that the bottles always held alcohol or that alcohol was always used recreationally. There is much evidence to suggest that bottles were reused for other liquids; they may have been refilled domestically, returned by consumers to manufacturers for refilling, or redistributed by second hand bottle traders (Busch 1991:113–116; Carney 1998). For these reasons it was appropriate to group the bottles together under storage.

Table 5.17: Storage bottle types.

| Sub-form | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|

| Aerated water | 5 | 2.8 |

| Beer | 2 | 1.1 |

| Beer/wine | 106 | 59.9 |

| Case gin | 1 | 0.6 |

| Cognac | 1 | 0.6 |

| Condiment | 5 | 2.8 |

| Oil/vinegar | 25 | 14.1 |

| Whiskey | 1 | 0.6 |

| Wine | 11 | 6.2 |

| Unidentified | 20 | 11.3 |

| Total | 177 | 100.0 |

Alcohol bottle forms (either originally used for alcohol or commonly associated with alcohol) comprised 68.9 percent of the glass storage bottles (Table 5.17). The majority were dark green cylindrical bottles usually associated with beer and wine, but frequently used for other liquids. All of these cylindrical bottles were made by traditional processing methods, which here refers to both blown and moulded, non-machine, manufacture. Only one machine-made bottle was recovered from the tip: a brown beer bottle with a crown seal. A turn and paste moulded brown beer bottle (TS 17) was also recovered. Twelve wine bottles were all dark green and processed by traditional techniques. String rim, ring seal, and champagne finishes were represented. A small number of spirits bottles were also recovered. A whiskey bottle (TS 111) was light green glass, traditionally manufactured with embossed lettering on the base ‘SCOTCH/ WOTHE…POONS WHISKEY’. A company called Wotherspoon’s of Glasgow produced jam, but it is not clear if this same company produced whiskey. Other spirits bottles included the square base of a dark green case bottle probably for gin (TS 460, and a glass seal from the shoulder of a dark green cognac bottle (TS 440). The seal read ‘NEC PLURIBUS…/ COGNAC/ E FORESTIER & H SAB…/ BORDEAUX’ with a logo of a sun with a face. No details could be found for this manufacturer.

Also present in the tip in significant numbers were oil/vinegar bottles. Twenty-three were light green glass with fluted decoration on the circular body (TS 106). Another oil/vinegar bottle (TS 138) had a decorative rib pattern, joining in arches on the body. A curved alternating rib and flute pattern decorated the lower body of another (TS 160). A partial maker’s mark on the base indicated that the bottle was made in Liverpool. A minimum number of five condiment bottles were also recovered from the tip. Four of the bottles were light green glass pickle bottles with wide mouths. One (TS 130) had moulded ‘two-tiered pickle’ decoration (Roycroft and Roycroft 1979:13). A bottle with a club sauce finish (TS 150) was also recovered. Possibly part of the same item was the base of a Lea & Perrins sauce bottle (TS 204).

A small number of aerated water bottles were also recovered. All five were light green glass with blob top finishes (TS 201) and one had a wire closure in place. Twenty bottles were storage bottles of unknown use. They included light green, colourless, brown, green and dark green glass and were all made by traditional techniques.

Of the storage bottles from the tip, 22.6 percent had makers’ marks present (Table 5.18). Eighteen oil/vinegar bottles had an English diamond registration mark. These registration marks were 37issued by the London Patent Office, usually to English manufacturers, but it must be noted that it was possible for foreign manufacturers to gain an English registration mark (Godden 1964:526). A further 13 bottles had manufacturers’ marks on them, three of which could be positively identified and dated. The first was a bottle manufactured by A C B Co. for Lea & Perrins who produced their sauce in Worcester from 1838 (Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004a:246). Another was manufactured by Cooper & Wood, a company which operated out of Portobello in Scotland from 1859 to 1928 (Boow c.1991:177). The Woolfall Co. which operated in Manchester from 1836 to 1861 was identified as the manufacturer of one bottle (Woolfall 2006). The remaining ten manufacturers’ marks could not be positively associated with a company. In addition, nine bottles had illegible or incomplete marks, one of which revealed the place of manufacture of the bottle as Liverpool, England.

Table 5.18: Summary of makers’ marks on glass storage bottles.

| Manufacturer | Retailer | Place of Manufacture | MNI | Start Date | End Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A C B Co. | Lea & Perrins | England - Worcester | 1 | 1838 | |

| A.B. & Co. | 1 | ||||

| C W… Co | 2 | ||||

| Cooper & Wood | Scotland - Portobello | 1 | 1859 | 1928 | |

| E Forestier & H Sab… | France - Bordeaux | 1 | |||

| E.G.B.W. Co. | 1 | ||||

| S P & P | 4 | ||||

| Woolfall Man Co. | England - Manchester | 1 | 1836 | 1861 | |

| Wotherspoons | 1 | ||||

| Diamond registration mark | 1 | 1842 | 1883 | ||

| Diamond registration mark | 5 | 1842 | 1868 | ||

| Diamond registration mark | 7 | 1869 | 1883 | ||

| Diamond registration mark - registered 1855 | 5 | 1855 | 1868 | ||

| Unidentified | England - Liverpool | 1 | |||

| Unidentified | 8 | ||||

| None present | 137 | ||||

| Total | 177 |

A number of bottle closures were also recovered from the tip. These included ten light green glass bottle stoppers of the type used for condiment or sauce bottles: four (TS 260) had circular finials and shanks and were undecorated, three more were similar in shape to these, but were decorated with moulded bands on the finial, two (TS 252) were embossed with ‘LEA & PERRINS’, and another (TS 236) was embossed with ‘KILNER BROS DEWSBURY’. The glass works company, Kilner Brothers, operated in various locations in England during the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century (Aussie Bottle Digger 2007). Their factory in Dewsbury opened in the early 1870s. Two decanter stoppers were also recovered: one (TS 510) had a flower motif on the top and a panelled body while the other (TS 513) was a hollow ball stopper with a star top and fluted body. A number of metal bottle closures were also identified. Three of these were lead bottle caps: one (TS 958) was impressed with ‘E &…/ TRADE/ EJB[D?]/ DUBLIN’, another (TS 702) had an embossed ‘Z’ on the top, and a third (TS 27) was plain. Also, 68 fragments of copper alloy wire (TS 1072) represent an approximate minimum number of ten were identified as being wire bottle closures from champagne or other bottles.

A glass jar and two glass jar stoppers were found in the tip. The jar was a colourless glass storage jar (TS 394), with a flared finish and moulded band below the rim. The two glass jar stoppers were light green glass. One (TS 210) was embossed on the top with ‘SYKES MACVAY & Co ALBION GLASSWORK [CAS]TLEFORD’ and was manufactured in England after 1863 (Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004a:243). The second was embossed with ‘AIRE & CALDER BOTTLE CO. CASTLEFORD LONDON’ on the top. Aire & Calder operated between 1836 and 1913 (Boow c.1991:175).

Further, 33 ceramic storage vessels were recovered from the tip, the majority of which (66.7 percent) were food and condiment jars. Eleven of these (TS 929) were straight-sided whiteware jam jars. Another (TS 872) was a polychrome underglaze transfer-printed mustard jar with a Venetian scene which dates to post-1840 (Brooks 2005a:43) (Figure 5.6). In addition, there were three ‘Bristol’ glazed buff-bodied stoneware jars and a large ‘Bristol’ glazed bottle with a flared rim (TS 80) which was probably a ginger beer or beverage bottle. This decorative technique was introduced by William Powell of Bristol in around 1835 (Brooks 2005a:28). Two clear glazed redware jar lids were also found 38in the tip, as well as a small buff-bodied stoneware jar lid with brown glaze. Four buff-bodied stoneware crock pots were also recovered. Crock pots are large open vessels with a shaped rim for holding a lid. One crock pot lid (TS 70) had a brown glazed exterior, another lid (TS 976) was salt glazed, the body of another (TS 774) had moulded bands as well as salt glaze, and the fourth (TS 755), which had both body and lid fragments, had dark brown glazed bands. Salt glaze, commonly used on stoneware storage vessels, was created by adding salt to the kiln while firing and results in a textured orange peel finish (Brooks 2005a:33). A brown glazed, buff stoneware covered bowl or jar (TS 1142), and five unidentified vessels were also recovered.

Figure 5.6: Mustard jar (TS 872).

Interestingly, four Chinese food jars were found in the tip. One was a large coarse earthenware Chinese ginger jar (TS 617) with white slip glaze on the lid and body and was a cheap imitation of a porcelain ginger jar (Muir 2006 pers. comm.). A rim fragment from a similar jar (TS 991) was also recovered, as were two Chinese pickled vegetable or tofu jar lids (TS 1145). The jar lids were both rough stoneware, shaped like a saucer, commonly used for sealing wide mouthed jars containing pickled vegetables or tofu (Wegars 2007; Bowen 2012:104–105).

Personal

Within the ‘Personal’ category there were 740 artefact fragments representing a minimum number of 188 objects (Table 5.19). These include items for adornment and personal wellbeing. The ‘Clothing’ category was dominant in this group.

Table 5.19: Summary of ‘Personal’ artefacts.

| Function | Form | Qty | Weight | MNI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessory | bead | 14 | 11.39 | 14 |

| brooch | 4 | 8.60 | 2 | |

| earring | 1 | 0.30 | 1 | |

| fan | 3 | 1.20 | 1 | |

| jewellery | 4 | 1.00 | 3 | |

| lens | 2 | 4.20 | 2 | |

| necklace | 1 | 1.00 | 1 | |

| Total | 29 | 27.69 | 24 | |

| Clothing | buckle | 1 | 2.40 | 1 |

| button | 67 | 62.60 | 64 | |

| fastening | 19 | 19.70 | 10 | |

| hook and eye | 56 | 6.06 | 19 | |

| safety pin | 7 | 4.20 | 4 | |

| shoe | 120 | 105.00 | 4 | |

| textile | 2 | 10.54 | 1 | |

| Total | 272 | 210.50 | 103 | |

| Grooming and Hygiene | bottle | 69 | 1,593.70 | 7 |

| brush | 5 | 38.20 | 3 | |

| chamberpot | 96 | 1,082.80 | 4 | |

| comb | 5 | 0.20 | 1 | |

| ewer | 137 | 1,221.60 | 3 | |

| jar | 8 | 78.40 | 4 | |

| toothbrush | 47 | 120.00 | 16 | |

| Total | 367 | 4,134.90 | 38 | |

| Health Care | bottle | 68 | 423.40 | 19 |

| stopper | 4 | 52.80 | 4 | |

| Total | 72 | 476.20 | 23 | |

| Total | 740 | 4,849.29 | 188 |

Accessory

Personal accessories were items worn by a person for adornment or convenience. Twenty-nine fragments representing 24 artefacts belong to the ‘Accessory’ category. Six of these were jewellery items including two brooches. One brooch (TS 997) was gold-plated copper alloy with a scroll design and an oval in the centre, which almost certainly held a gem, while the other (TS 1056) had a copper back and scalloped edge and may have been a cameo brooch. Part of a gold earring (TS 855), 10 mm in diameter, with a hinged post for a pierced ear and a fine gold chain necklace (TS 1057) were also found. Other unidentified jewellery items were also recovered including an item (TS 1031) which may have been a brooch and some small fragments in gold alloy and gold-plated copper alloy. The fact that all of the jewellery items were incomplete may indicate that they were discarded because they were broken.

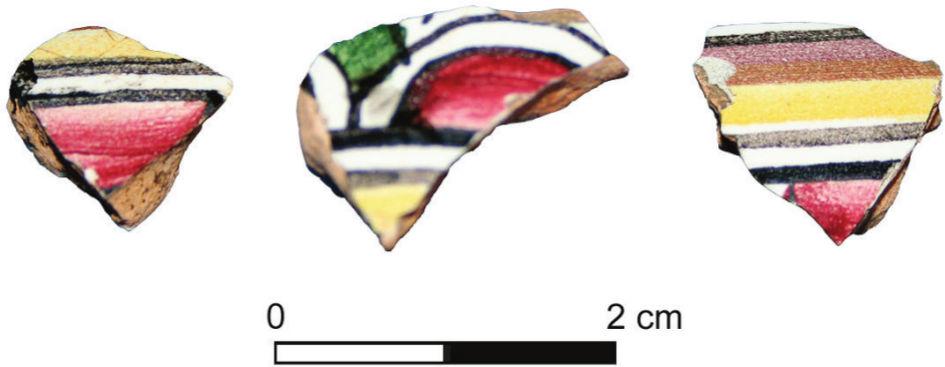

In addition to these jewellery items, a total of 14 beads of eight different types were found throughout the tip. The majority of the beads (78.6 percent) were glass, in black (7), colourless (2), blue (1) and aqua (1). The two colourless beads were the only beads which were decorated. One was gilded (TS 844) while the other had etched lines (TS 1048). There were also two 39ceramic beads, one of which (TS 148) was made by the Prosser technique dating to post-1840 (Sprague 2002:111) and was decorated with bands. There was also one undecorated wooden bead (TS 1008). Beads varied in function, but were most commonly from necklaces, jewellery parts, rosaries, decorations on garments or lace-making bobbin spangles (Iacono 1999:42). It has been suggested that beads under 6 mm were commonly used on garments, while beads over 6 mm would be from necklace or jewellery parts (Karklins 1985:115). Twelve of the beads were between 6 and 12.6 mm and were therefore more likely to be from jewellery. The remaining two beads were tubular with diameters under 6 mm.

Two lenses (TS 183) were found in the tip: one was ovoid and convex for sight-correction, while the other was circular and did not appear to be sightcorrecting. They represent two pairs of glasses, although no frame fragments were identified. They may have been from spectacles, monocles or lorgnettes. Spectacles were quite common in the 19th century, and fashionable men and women preferred folding lorgnettes. These were spectacles that folded into a short or long handle. Steel, gold and tortoiseshell frames were common. Circular and ovoid lenses were used in both spectacles and lorgnettes (Davidson and MacGregor 2002:21–24).

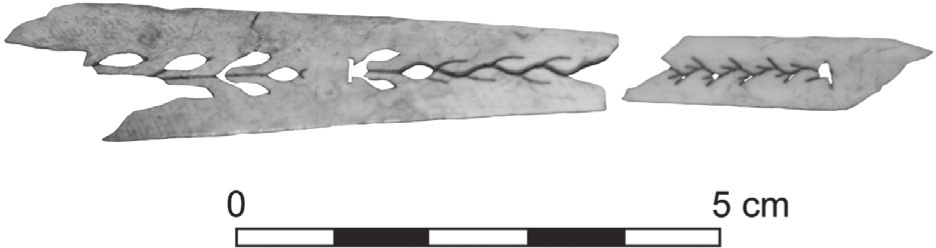

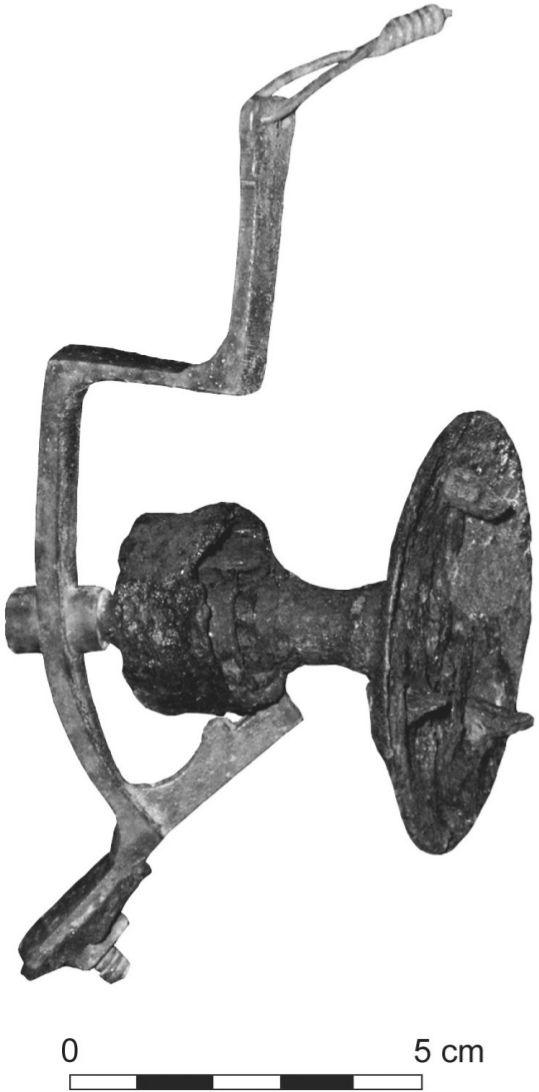

Fragments of a stick from a hand-held folding fan (TS 1143) were also found. The stick was bone and decorated with a carved floral motif (Figure 5.7). The fan was probably a brisé fan made entirely from sticks linked together at the top with a ribbon and held together at the base by a rivet. Folding fans were popular throughout the 19th century (Cheltenham Museum 2006). Type 1148 was recorded as unidentified, but may also have been part of a folding fan.

Figure 5.7: Fan fragments (TS 1143).

Clothing

A total of 272 artefact fragments representing 103 artefacts belonged to the ‘Clothing’ category. The majority of these were fastenings, 64 of which were buttons. The majority of the buttons were either metal or composite, but there were also shell, bone, ceramic and glass buttons. Many of the buttons, 51.6 percent, had some form of decoration (Table 5.20). The most common decoration type was a fabric covering. Fabric-covered buttons were factory manufactured from the early 19th century and by the 1850s inexpensive cloth covered buttons had overtaken metal buttons in popularity. Around the 1860s, it became popular to match the fabric on the button to that of the garment, and tailors and dressmakers purchased button moulds for this purpose (Albert and Kent 1971:46–48).

Table 5.20: Decoration on buttons.

| Decorative Technique | Decoration | MNI | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applied | Floral | 3 | |

| Prince of Wales feather | 1 | ||

| Total | 4 | 6.3 | |

| Cut | Facets | 5 | |

| Total | 5 | 7.8 | |

| Embossed | Anchor | 2 | |

| Bands | 1 | ||

| Rouletting | 4 | ||

| Stippling | 1 | ||

| Total | 8 | 12.5 | |

| Embossed/Japanned | Rouletting | 2 | |

| Unidentified | 1 | ||

| Total | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Fabric covered | Fabric | 9 | |

| Total | 9 | 14.1 | |

| Japanned | Black | 1 | |

| Total | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Lathe-turned | Bands | 1 | |

| Total | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Moulded | Circles | 1 | |

| Floral | 1 | ||

| Total | 2 | 3.1 | |

| None present | None present | 5 | |

| Total | 5 | 7.8 | |

| Undecorated | Undecorated | 26 | |

| Total | 26 | 40.6 | |

| Total | 64 | 100.0 |

Many of the metal buttons were embossed with rouletting, stippling or bands. An embossed anchor decorated the obverse of two buttons (TS 230 and TS 1018), and another featured an applied Prince of Wales feather (TS 1023). Embossing was combined with japan decoration on three buttons and another was japanned alone. Japan decoration is a highly glossy black enamel finish popular from 1838 to 1900 (Cameron 1985:23–24). Three matching copper and iron alloy buttons (TS 1009) had an applied glass ‘gem’ in the centre surrounded by a copper alloy flower. These were decorative, fancy buttons 14 mm in diameter and may have been decorative buttons from women’s clothing.

Five of the glass buttons (including those with metal attachments) were black and there was one each in white, yellow and dark blue. Four of the black buttons (TS 975) matched. Black buttons often adorned mourning dress and were also particularly popular in the period following Prince Albert’s death in 1861 when Queen Victoria was 40in mourning (Lindbergh 1999:54). The dark blue button (TS 1024) had moulded circle indentations on the obverse and the yellow button (TS 296) had a moulded floral design. One shell button (TS 1040) was decorated with two lathe turned bands around the rim.

Figure 5.8: Button attachment types. From top left: one, two, three and four-hole sew-through, birdcage, hoopshank, pin-shank and post.

Eight different attachment types were identified on the Viewbank buttons (Figure 5.8). The most common was the four-hole sew-through type, but one, two and three-hole sew-through, as well as post sew-through types were also identified. The three bone buttons with one hole may have had a metal pin inserted through the body and twisted at the back to form a loop for sewing on to clothing (Albert and Kent 1971:25). Also common was the hoop-shank attachment, and one metal button (TS 1023) was pin-shanked. There were also three split pins, which may have belonged to other pin-shanked buttons. Four matching tiny buttons (TS 1017) had a birdcage attachment with four holes. Sew-through types were more utilitarian and cheaper than the shanked types which could be removed before washing to preserve them (Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004b:320).

Four of the four-hole sew-through copper alloy buttons had embossed lettering; however this was illegible on two of the examples. One (TS 1029) read ‘MOSES LEVY & CO. *LONDON*’, but no information could be found for this maker. Another (TS 1019) read ‘… double ring …’ which was probably an advertisement for the quality of the button.

It is possible to use size to suggest the use of a button. Small buttons (8–15 mm) were mostly commonly used for underclothing, shirts and waistcoats, while medium buttons (16–21 mm) were used to fasten coats, jackets, pyjamas and trousers (Birmingham 1992:105). Tiny buttons (less than 8 mm) in common forms were commonly used for children’s clothes, while tiny fancy buttons were more likely to be from women’s garments (Lindbergh 1999:53–54; Sprague 2002:124). Of the Viewbank buttons, 64.1 percent were small, 20.3 percent medium, 10.9 percent tiny and 4.7 percent over 21 mm.

Hook and eye fastenings (TS 687) made up 16.8 percent of the ‘Clothing’ related artefacts and included 58 copper alloy fragments representing 19 hook and eye sets. Hook and eye fastenings were popular throughout the 19th century and continue to be used today. They were most commonly used on women’s close fitting outer garments and were essential to the correct fit of bodices (Kiplinger 2004:7–8). They were not used on undergarments, which were fastened with tapes, ties or buttons (Cunnington and Cunnington 1951:18–19). Hook and eye fastenings could be purchased in large numbers relatively cheaply (Griggs 2001:81).

Three safety pins (TS 838) were recovered from the tip, each shaped from one piece of copper alloy wire. It is likely that the safety pins were used to fasten clothing or to assist with sewing. Safety pins with a cap head were first made in 1857 (Noel Hume 1969:255). It is unclear whether this open version was an earlier type or simply a more basic alternative. A fifth object (TS 1053) was in the same form as these safety pins, but had a curved copper alloy attachment. This attachment may have held a decorative element or functioned as some sort of attachment for a cloak or other item of clothing.

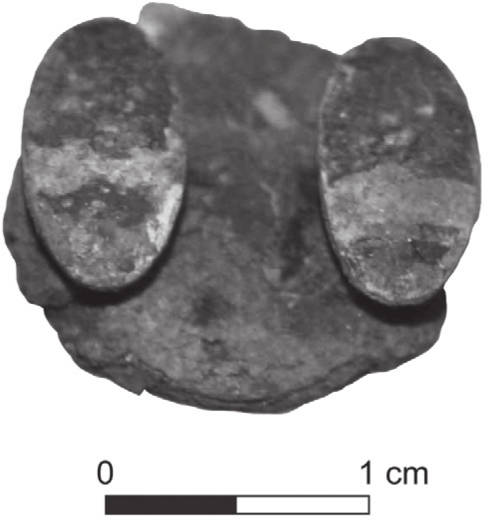

Figure 5.9: Double oval shank clothing fastening (TS 1007).

Further, ten fastenings associated with clothing, but of indeterminate form were recovered. Four of these were possibly men’s clothing fastenings, all of which featured a circular copper alloy disk with oval feet attached on one side. One (TS 113) fastener had one foot, while three had two feet (TS 1007) (Figure 5.9). These feet were fixed and were not hinged like with other men’s clothing fastenings 41(see Eckstein and Firkins 2000). Three fastenings (TS 801 and TS 849) were possibly components from suspenders. Suspenders, which attached to the bottom of the corset as a fastener for stockings, only took the place of elastic garters in 1878 (Cunnington and Cunnington 1951:180). Another fastening (TS 623) had two slots for fabric to thread through and hold in place, while a similar item (TS 1076) was an ovoid disk with a rectangular slot in the centre. The complete form of these two artefacts is unknown, but they were possibly fastenings for undergarments. Finally, there was a square black glass cuff link or possibly button (TS 1073) measuring 20 mm by 20 mm. It had a flat obverse with cut facets on the edges. The copper alloy attachment on the reverse had been heat affected and its form was unidentifiable. Cuff links were first noted in 1824 (Cunnington and Cunnington 1951:19).

One hundred and twenty fragments representing a minimum number of four shoes or boots were recovered. Limited analysis was possible due to the fragmentary nature of the shoes. Four different sized shoelace eyelets were identified as well as one shoe lace hook. Both circular and square shoe nails were present, all of which were copper alloy. Four tightly curved sole fragments were found and appear to be from shoes with pointed toes. Gently pointed toes became particularly fashionable for men’s shoes in the 1840s (Veres 2005:91). One stacked heel was recovered and was probably from a man’s boot (Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004b:330). A ‘D’ shaped iron alloy heel protector was also recovered.

Only two other artefacts were associated with clothing: a buckle and textile. The buckle was a small copper alloy slide type with two slots and no pins (TS 706) and was probably not from a belt, but rather fastened a cloth strap, possibly as part of underwear. The textile was recovered in small fragments (TS 673) and in a poor state of preservation so that the type of fabric and pattern were indiscernible.

Grooming and Hygiene

Objects related to ‘Grooming and Hygiene’ included those used to maintain everyday personal cleanliness and appearance. At the Viewbank site, there were 367 fragments representing a minimum of 38 objects attributed to this category, many of which were toothbrushes.

Sixteen toothbrushes were recovered from the tip, all made from bone. Ten of the unmarked toothbrushes had bristles attached by trepanning wire drawing, where the wires run through bores inside the brush head (Shackel 1993:46; Mattick 2010:12–13). A further three toothbrush heads had bristles attached by a process of wire drawing with cut grooves on the back of the brush head to accommodate the wires (Shackel 1993:45; Mattick 2010:11–12). Three of the toothbrush handles were carved with a maker’s mark. One handle (TS 1041) read ‘4 G GURLING & CO LONDO…’. Another (TS 1147) read ‘GEO…LEWIS CHEMIST// PEARL CEMENTS/ …ENT/ LONDON’ and had bristles attached by wire drawing with cut grooves (Figure 5.10). A third (TS 1067) read ‘…SFORD LONDON’. Although toothbrushes were locally available (Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004b:337), all the marked examples in the Viewbank assemblage were imported from England. The large number of toothbrushes, given the relatively few occupants of the site, may represent the importance placed on oral hygiene.

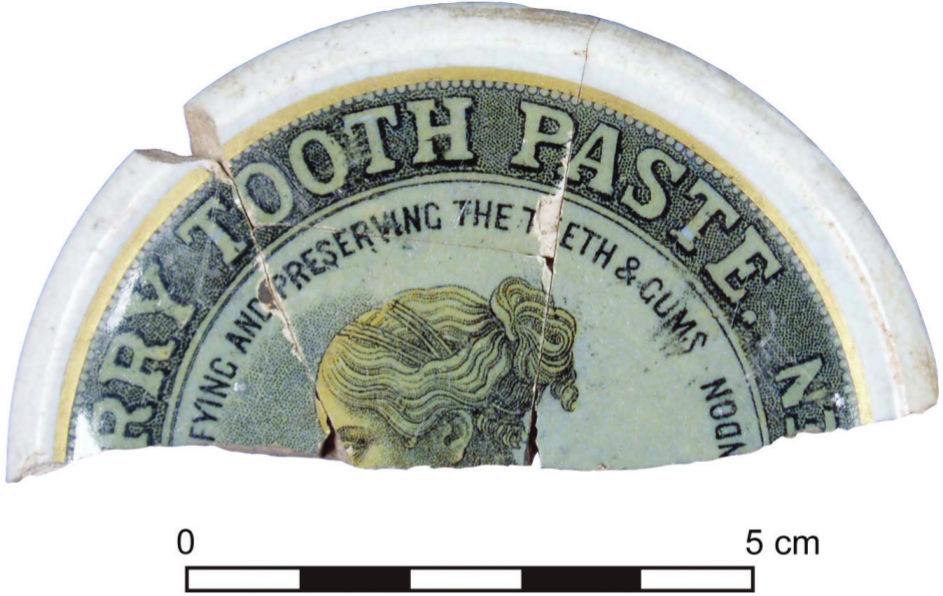

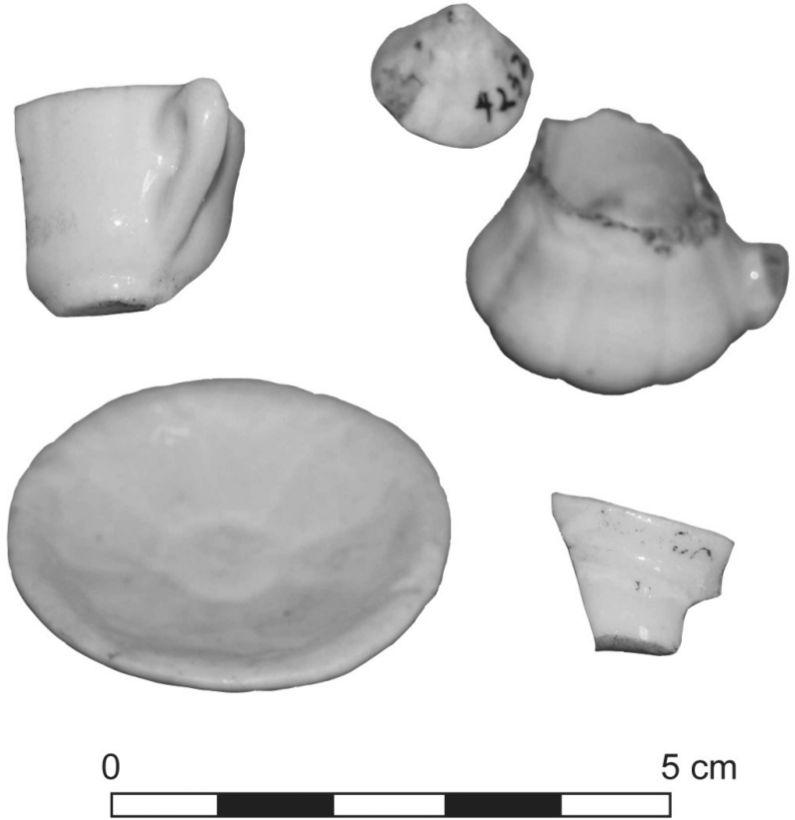

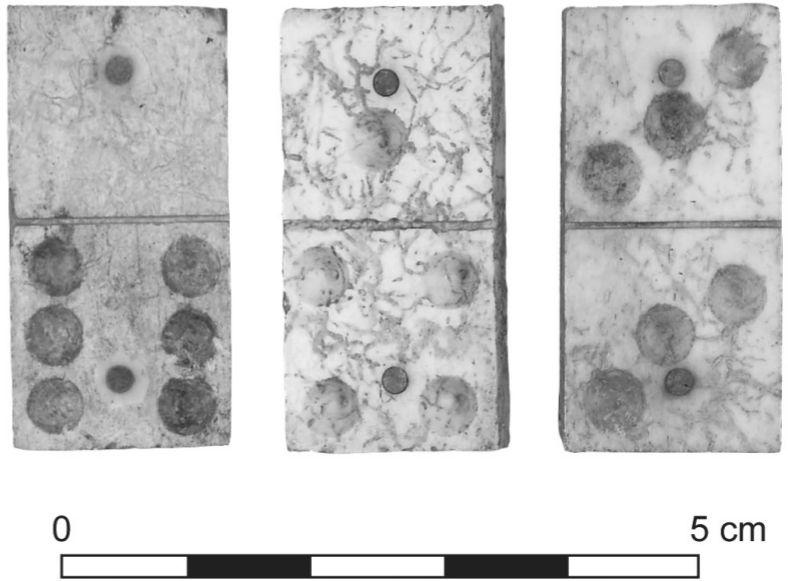

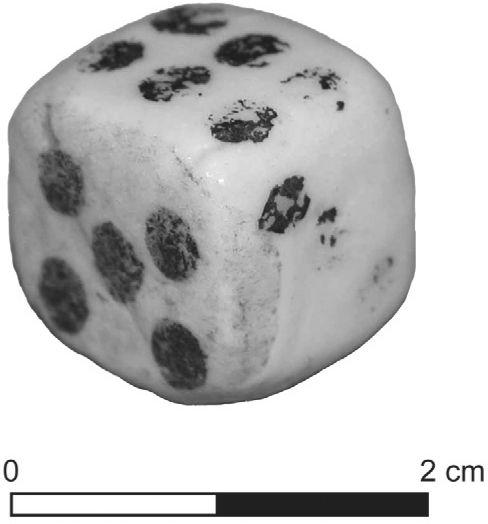

Figure 5.10: Toothbrush (TS 1147).