6

Acquisition of Goods

Consumer practice is the behavioural pattern by which people acquire goods, both for necessity and luxury. It is influenced by a range of factors including affordability, accessibility and desirability. This chapter is informed by a number of previous archaeological studies that have focused on trade networks, consumption and shopping in Australia. Notable among these are Crook’s (2000, 2011) studies of shopping in working-class Sydney and quality in consumer decision-making, Staniforth’s (2003) use of evidence from shipwrecks to explore trade and social networks, Davies’ work on trade networks in working-class Melbourne (Davies 2006b) and on accessing goods in remote areas (Davies 2006a:95–107), and Allison and Cremin’s (2006) work on trade catalogue use in rural New South Wales.

The section on ‘Markets’ examines the origins of artefacts from the Viewbank assemblage in order to explore the trade networks linking Viewbank homestead to Melbourne, Australia and the world, networks which can embody the social and economic structure of the community and also changes to that structure. The following section on ‘Shopping’ investigates the processes of acquisition and shopping as a genteel performance. It also discusses the influence of availability and price on the choice of goods. The purchase of correct goods, in the correct taste, was central to the cultural capital of gentility, and therefore to determining class position in the new colony. The examination of consumer practice in this chapter forms the basis of the discussion on lifestyle and class to follow.

MARKETS

Artefact assemblages allow us to examine the economic and social networks in which people were engaged by analysing the origin of goods they purchased (Adams 1991). This engagement was facilitated by industrialised mass production and new technologies for transporting goods, which allowed for far-reaching, global trade networks in the 19th century.

Discussion of the origin of artefacts from the Martins’ residence in this section is limited to those objects with makers’ marks, or where possible other features, that positively identify their place of manufacture. Although this may not reveal all the sources of goods in the assemblage, it does indicate the general patterns of access to trade networks. Of the artefacts recovered from the tip, 5.9 percent could be associated with a country of manufacture (Table 6.1). For information regarding the origin of artefacts from the homestead contexts, see Hayes (2007:93–94).

England: The Dominant Market

The predominance of English-made goods in the tip is unsurprising because of their importance in the Australian consumer market in the 19th century. The extensive scale of production in Britain allowed these goods to dominate the market. Most notable among the positively identified English goods at Viewbank were the ceramic tableware and teaware vessels. It has been widely noted that the vast majority of ceramics found on 19th-century archaeological sites in Australia were imported from England (see Casey 1999:23; Brooks 2005a).

All of the tableware and teaware recovered from the tip with makers’ marks identifying their origin were made by Staffordshire potteries. In addition, one of the chamberpots was made by a Staffordshire pottery. It is highly likely that the majority of the unmarked ceramics were also made in Staffordshire, as by the mid-19th century two-thirds of Britain’s potteries were located in the region (Snyder 1997:5). The United States was the largest consumer of Staffordshire products between the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 and the beginning of the American civil war in 1861 (Copeland 1998:17). However, exports were also sent to South America, Canada, Australia and other countries of the British Empire (Majewski and O’Brien 1987:103; Rodriguez and Brooks 2012).

It is likely that restricted availability of goods in the Australian market influenced what was purchased by the Martin family. One example is the presence in the Viewbank assemblage of ceramics made by Staffordshire potteries, specifically for export to the United States. Many Staffordshire potteries catered exclusively for the large American market (Graham c.1979:2) with vessels which often included American national symbols and mottos, and decorations which appealed to American taste. When the American Civil War commenced in 1861 this market became restricted and the potteries quickly needed to find new markets for their wares. Newspapers documented how exports to the United States decreased, while in the subsequent years exports to Australia and New Zealand, among other countries, increased (Brooks 2005a:58–59). 50

Table 6.1: Identified country of manufacture by maker’s mark.

| Place of Manufacture | Form | Material | MNI | % |

| England | bottle | glass | 18 | |

| England | coin | metal | ||

| England - Dewsbury | stopper | glass | 1 | |

| England - Liverpool | bottle | glass | 1 | |

| England - London | bottle | glass | 2 | |

| England - London | button | metal | 1 | |

| England - London | cartridge | metal | 4 | |

| England - London | jar | ceramic | 1 | |

| England - London | stopper | glass | 1 | |

| England - London | toothbrush | organic | 3 | |

| England - Manchester | bottle | glass | 1 | |

| England - Nottingham | bottle | ceramic | ||

| England - Staffordshire | chamberpot | ceramic | 1 | |

| England - Staffordshire | plate | ceramic | 23 | |

| England - Staffordshire | platter | ceramic | 5 | |

| England - Staffordshire | saucer | ceramic | 2 | |

| England - Staffordshire | ui flat | ceramic | 1 | |

| England - Staffordshire | ui hollow | ceramic | 2 | |

| England - Staffordshire | unidentified | ceramic | 2 | |

| England - Worcester | bottle | glass | 1 | |

| England - Worcester | stopper | glass | 1 | |

| England - York | bottle | glass | ||

| England - Yorkshire | stopper | glass | 1 | |

| England | 72 | 94.7 | ||

| France - Bordeaux | bottle | glass | 1 | |

| France | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| Ireland - Belfast | bottle | glass | ||

| Northern Ireland | ||||

| Ireland - Dublin | bottle cap | metal | 1 | |

| Ireland | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| Scotland - Portobello | bottle | glass | 1 | |

| Scotland | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| America | lamp | metal | 1 | |

| America | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| Total | 76 | 100.0 |

The presence of vessels clearly intended for the United States market in the Viewbank assemblage provides evidence that British exports originally intended for the United States were being sent to Australia when they could no longer be sold in the United States (Brooks 2005a:59). One such vessel was a moulded whiteware jug which bore as part of a printed maker’s mark the national motto of the United States used from 1782 to 1956, E Pluribus Unum (from many, one).

Further evidence is the relatively large amount of white granite ware identified at Viewbank. Moulded white granite vessels were made by Staffordshire potteries in response to changes in American taste that favoured simply decorated ceramics, and to compete with popular French porcelain (Ewins 1997:46–47). In the United States the popularity of plain white or moulded white granite and ironstone from the 1850s was well established (see Majewski and O’Brien 1987:120–124; Miller 1991:6). At Viewbank, 11.9 percent of the ceramic tableware and 10.1 percent of the teaware was white granite. There were two matching sets of white granite. One was in the ‘Berlin Swirl’ pattern and had two vessels with the maker’s mark of Mayer & Elliot, a Staffordshire pottery, and were impressed with the date 1860 (Godden 1964:422). Another two were marked with Liddle, Elliot & Son who changed to 51that name from Mayer & Elliot in 1862 (Godden 1964:235). The second set was ‘Girard Shape’ made by John Ridgway Bates & Co. between 1856 and 1858 in Staffordshire (Godden 1964:535). These dates coincide closely with the beginning of the American Civil War.

The reason for the purchase of white granite wares by the Martin family is difficult to discern. There is, to date, little evidence from other Australian sites to shed light on this. White granite has not been identified at many sites in Australia, probably to some extent because of the difficulty of distinguishing white granite from other wares, particularly when in a fragmentary condition (Brooks 2005a:25, 34–35). Brooks (2002:56) has identified white granite at sites from inner Melbourne and country Victoria. No white granite was identified, however, in the Casselden Place ceramic assemblage (Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004a:21–22), possibly because of the different social group or the later time period.

The Martins may have purchased white granite sets because of fashion or desirability. Miller (1980, 1991) has demonstrated that in the United States white granite was relatively more expensive than other wares, such as whiteware. As such, it would have been affordable for Australia’s middle class, but less accessible for working-class people. This may explain its absence on working-class sites in Australia. DiZerega Wall (1992:79) also suggests that white granite vessels in Gothic shapes became fashionable among the American middle class because of their association with the sanctity of churches, and contrast to capitalist markets. It is possible that the Australian middle class purchased white granite ware for this reason. However, it has been noted in the archaeological record that there was a trend in Britain and its colonies in the 19th century for colourful ceramics, particularly those with transfer prints (Lawrence 2003:25–26). On the whole, the Martin family were following this trend with colourful ceramics comprising the significant majority of the Viewbank assemblage.

A number of specialised items were identified as being manufactured in London: ammunition, toothbrushes, perfume bottles, a button, a cherry toothpaste jar and a food storage jar stopper. A small number of glass food storage bottles and stoppers, medicine bottles, a beer/wine bottle and an ink bottle were manufactured in other English towns (Table 6.1). Eighteen glass oil/vinegar bottles also bore an English registration mark. These registration marks were issued by the London Patent Office, usually to English manufacturers, but it must be noted that it was possible for foreign manufacturers to gain an English registration mark (Godden 1964:526). It is difficult to determine whether these bottles were shipped to Australia with the product inside or empty for filling by local producers. The perfume bottles were most likely shipped with their contents as the maker’s mark was that of a London perfumer John Gosnell & Co.

The importance of the social and economic ties between England and Melbourne is certainly visible in the Viewbank assemblage. The relatively small population of Port Phillip, and Australia generally, relied on the strong trading system of the Empire of which they were a part. In the early to mid-19th century, local manufactures struggled to compete with British mass production. The Viewbank tip assemblage shows that household items such as tableware, condiment bottles, and also medicine bottles and personal items were being imported from England to Australia and purchased by the Martins. There is also evidence for the exploitation of the Australian market by English manufacturers for selling goods that could no longer be sold in other markets, namely the United States.

Ireland, Scotland, Continental Europe and the United States: Supplementary Goods

A small number of items had makers’ marks identifying their place of origin as Ireland, Scotland, Continental Europe or the United States, implying trade links with these places. Two items were manufactured in parts of the British Isles other than England. A lead bottle cap was manufactured in Dublin, Ireland, and a beer/wine bottle was made by Cooper & Wood, Portobello, Scotland (Boow c.1991:177). Although not to the same extent as London, the manufacturing and shipping centres of Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dublin were also shipping goods directly to Australia (Nix 2005:25).

From Continental Europe there was a cognac bottle imported from Bordeaux, France. Further, four porcelain dolls were probably made in Germany, which was the main producer of porcelain doll parts until World War I. France and England also supplied doll parts, but to a much lesser extent because mass production in Germany allowed for the production of cheaper dolls (Pritchett and Pastron 1983:326). In addition to these doll parts there were two swirl marbles which were manufactured in Germany from 1846 (Ellis 2001:174). These goods may have been shipped to English or other British ports and then exported to Australia, rather than shipped directly from Europe (Nix 2005:38).

One artefact recovered from the tip was positively identified as being manufactured in the United States. This was a copper alloy deflector from a vertical wick kerosene lamp. Robert Edwin Dietz and his brother Michael patented the first flat wick burner for use with kerosene in 1859 (Kirkman 2007). This indicates that some goods were being traded from the United States to Australia after 1859. 52

Asia: Exotic Goods

Although not marked with makers’ marks there were a number of artefacts identified as originating from China in the Viewbank tip. From the 18th century, British merchants in India were trading between ports in the Eastern seas in what was known as the ‘country trade’ (Staniforth and Nash 1998:7–8; Staniforth 2003:72–73). This brought Chinese export porcelain to Australia soon after European settlement in 1788. American whaling vessels also transported Chinese export porcelain to Australia until 1812 when the English/American War interrupted trade (Staniforth and Nash 1998:9). Networks expanded further after the first Opium War (1839–1842) when the British forcibly opened trade with China allowing the development of an independent trade network between Australia and China. Increasing numbers of Chinese immigrants led to the emergence of networks of Chinese trade that ultimately extended throughout Victoria (Bowen 2012:39, 123). These businesses were established to provide for Chinese communities, but inevitably served European consumers as well (McCarthy 1988:145–146). This market was utilised to some extent by the Martin family.

A ‘Celadon’ spoon, two Chinese ginger jars and two jar lids were part of the Viewbank tip assemblage. Such items were made in China for a Chinese market, both domestic and overseas (Muir 2003:42). From the 1850s it became increasingly common to find Chinese jars in European households (Lydon 1999:57). The contents of ginger jars, and the jars themselves, were popular among Europeans in Australia. It is possible that these Chinese objects were purchased in Melbourne for their unusual or exotic qualities or simply for their contents. Ginger jars were also often given as gifts by Chinese people to their European friends or associates (Lydon 1999:57–58). Three further items – two bowls and a jar with brightly coloured polychrome overglaze decoration – were Chinese export porcelain made for sale to Europeans (Hellman and Yang 1997:174). These objects were fragmentary and it is difficult to discern the decorative patterns, although two of the vessels include human figures.

Australia: Rare Commodities

No artefacts from the tip were marked as being manufactured in Australia. The difficulty of local producers competing with British mass production in the early to mid-19th century meant that only goods that could be produced more cheaply in the colony or were protected by tariffs were viable. These tended to be large utilitarian items that were expensive to import. The lack of goods in the assemblage marked as being Australian-made does not necessarily mean that the Martin family were not purchasing Australian-produced goods. It is known from a list of debts upon Dr Martin’s death that the Martin family purchased perishable goods locally: dairy, meat, bread, grain, fruit and vegetables (VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 17, File 12-586, 11 February 1875). The only archaeological evidence of this is in the form of bones that remain from cuts of meat. Howell-Meurs’ (2000:42) analysis of the faunal assemblage from the Viewbank tip indicates that much of the meat was purchased from a butcher, as indicated by the relative absence of cranial and peripheral limb elements. While the butcher was preferred, the presence of some cranial and peripheral limb bones suggests that at least some complete carcasses were processed at Viewbank.

Of the 240 glass bottles recovered from the Viewbank tip, none were marked as Australian-made, or having Australian-made contents. However, by the time the Martins arrived in Port Phillip, there were already numerous small vineyards in Melbourne, Geelong and in the Martins’ local area of the Yarra Valley (Beeston 1994:38). While labour shortages during the gold rushes meant that the wine industry faltered, as the rush declined many turned to winemaking in the 1860s (Beeston 1994:47–48; Dunstan 1994:34). In addition to vineyards, by the mid-1840s there were six breweries operating in Melbourne, but the quality remained poor. In the early 1860s there were 20 breweries in Melbourne, and by 1874 there were 31 (Deutsher 1999:87). During the 1860s there were also 80 breweries operating in 34 country towns in Victoria (Deutsher 1999:88). In addition, there were 20 manufacturers of ginger beer, cordial and aerated water operating in Melbourne by 1863 (Davies 2006b:348).

It is important to consider that Australian manufacturers of beverages were using and refilling imported bottles prior to the commencement of the production of glass bottles in Australia. Many of these would have been unmarked bottles, but sometimes companies would also reuse marked imported bottles. In the 19th century, the second-hand bottle trade was a well established business with beverage manufacturers purchasing bottles from second-hand bottle dealers (Busch 1991). In Australia, there is archaeological evidence of this from a cordial factory in Parramatta which filled beer/wine bottles with its product (Carney 1998). This means that Australian-manufactured beverages are generally imperceptible in the archaeological record.

It became increasingly difficult for beverage manufacturers to obtain sufficient numbers of bottles and the demand grew for locally produced bottles. The Victorian Flint Glass Works was advertising for glassblowers in 1847, but was not a successful endeavour (Graham 1981:15–16). Demand from wine merchants for cheaply produced, locally made bottles led to the commencement of production of a small supply in Sydney from the 1860s (Graham 1981:17). However, inter-colonial tariffs prevented 53much trade between the colonies. It was not until 1872 that the first major glass manufacturer in Melbourne, the Melbourne Glass Bottle Works Company, opened, with other companies following (Vader 1975:14). As such, during the period the Martins lived at Viewbank there was a very limited supply of locally made glass bottles.

Stoneware bottles were produced in Sydney from early in the 19th century and in the 1850s the production of stoneware bottles began in Melbourne (Ford 1995:176–293). However, only one of the stoneware bottles from the Viewbank tip may have been for a beverage, either aerated water or ginger beer, but was unmarked.

No other artefacts recovered from the Viewbank tip had Australian makers’ marks. However, a number of ceramic vessels from the Viewbank tip may have been made in Australia. Potteries had been established in New South Wales and Tasmania from the start of the 19th century (Casey 1999: 7) and in Victoria from the 1850s (Ford 1995: 176–293). From the mid-19th century onwards, Australian potters were predominantly producing utilitarian wares to avoid being in direct competition with British imports of tableware and teaware (Casey 1999:23). These potteries produced stoneware storage containers, flowerpots, cooking vessels, dairying vessels, basins, ewers, chamberpots and, frequently also, ‘Rockingham’ glazed teapots, and Majolica glazed kitchen and decorative wares (Birmingham and Fahy 1987:8; Ford 1995:176–293). However, very few Australian-made ceramics were marked before the later 19th century, making them difficult to positively identify in the archaeological record (Birmingham and Fahy 1987:7). In the Viewbank assemblage, a number of ceramics may have been made in Australia. These included stoneware storage containers, redware flowerpots, and two ‘Rockingham’ glazed vessels (probably teapots). However, ‘Rockingham’ glazed vessels were also produced in Britain (Brooks 2005a:41). The slip-glazed redware milkpans recovered from the Viewbank tip were probably Australian-made as they were becoming less popular in Britain by this time (Brooks 2005a:42). It seems that the Martin family were purchasing at least some Australian-made goods, although they were unmarked.

SHOPPING

Imported goods find their way to consumers through national, regional and local networks (Adams 1991:397). The study of shopping can provide additional insight into consumer practice and the interpretation of goods recovered from archaeological sites (Crook 2000). The method of shopping implies different social dynamics; for example, a middle-class standard of wealth was required to shop in fashionable inner-city shops, while the working class was generally restricted to open-air market shopping where goods were more affordable (Crook 2000:17). This section explores how and where the Martin family were purchasing goods.

First of all, it is possible that the Martin family brought some household goods with them from England and that these represent part of the assemblage. An overglazed, black transfer-printed and enamelled vessel dates from 1750 to 1830 (Brooks 2005a:35, 43), which is prior to the Martins’ arrival in Australia. The Martins probably brought this, and a number of other items, to Australia from England.

The assemblage recovered from the tip suggests that goods were being purchased over the entire period that the Martins occupied Viewbank. The ‘Summer Flowers’ set and Masons plates had date ranges ending in the 1850s, a Copeland chamberpot dated from 1847 to 1867, and a set of plates with ‘Bagdad’ pattern dated from 1851 to 1862. The white granite vessels had start dates in the late 1850s and 1860s. Finally, a ‘Rhine’ plate dated from 1869 to 1882. This gives the impression that rather than purchasing ceramics all at one time upon their arrival at Viewbank, the Martins were buying goods throughout their period of occupation. Further, glass bottles with tight dates included a seal dated prior to 1850, while others dated from prior to the Martins’ arrival at Viewbank to the 1870s. Other artefacts dated well into the period that the Martins lived at Viewbank. Doll parts dated from 1850 to 1880, and 1860 to 1900, and a lamp was purchased after 1859. As such, it appears that the tip included goods purchased throughout the time that the Martins occupied the site.

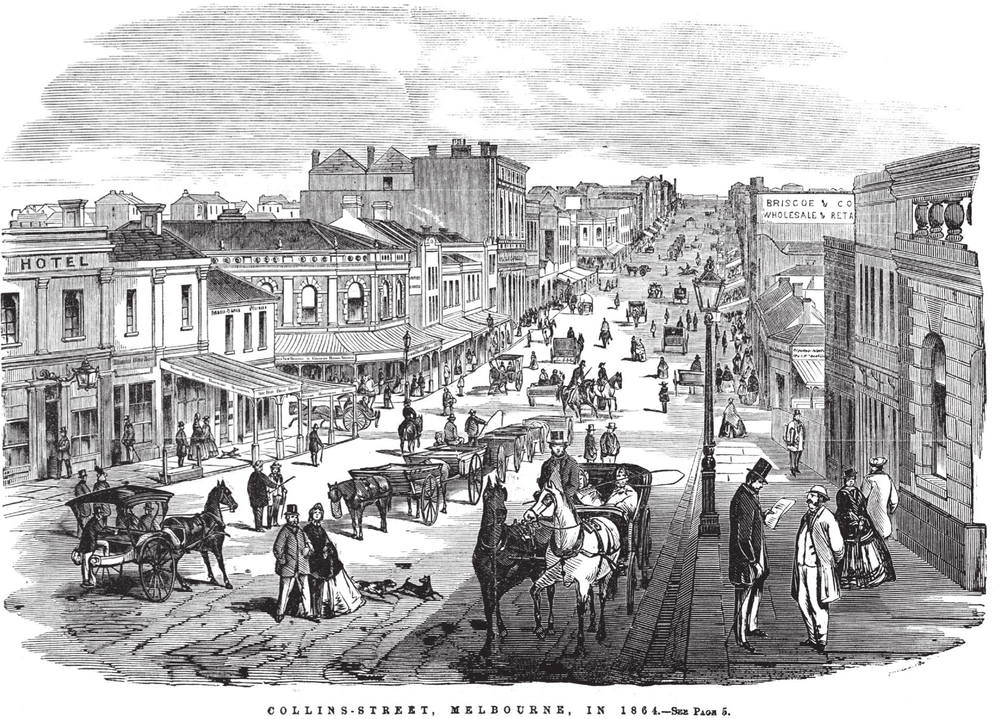

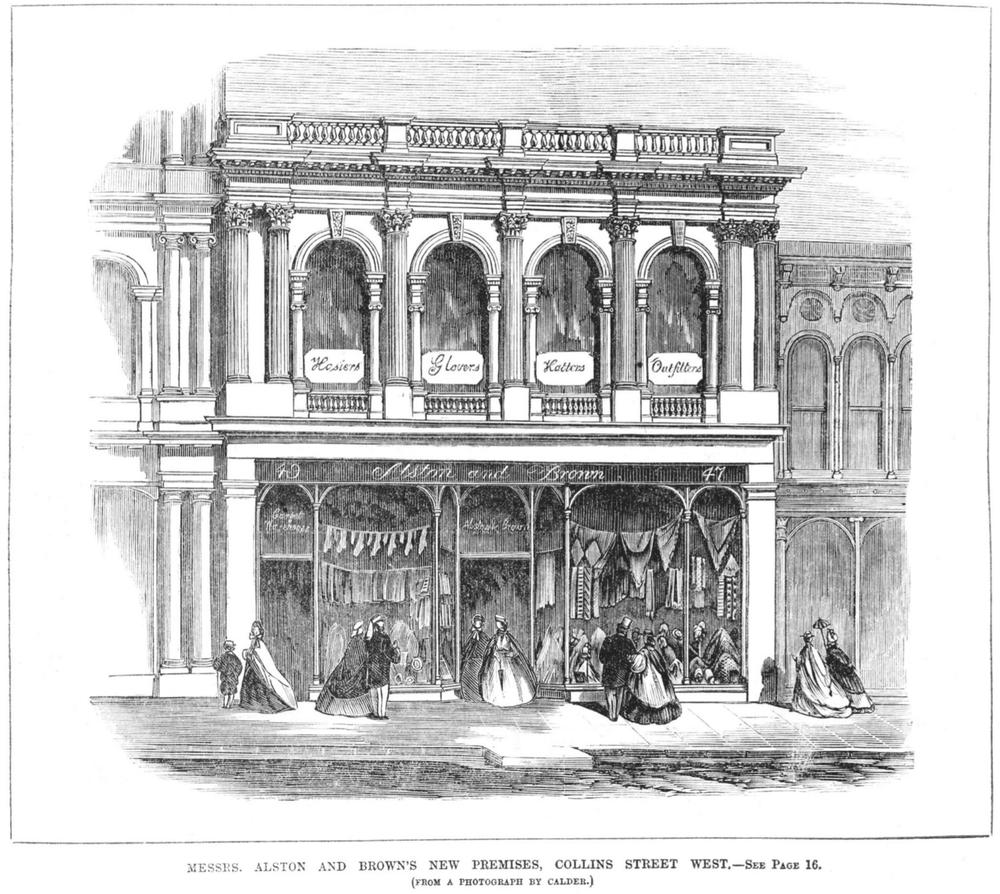

Some of the ways in which the family purchased goods in Victoria in the 1870s is indicated in a statement of duty after Dr Martin’s death, which lists his unsecured debts to a number of traders (PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 17, File 12-586, 11 February 1875) (Table 6.2). Living an easy distance from inner-city Melbourne, the family would have been able to enjoy access to the full variety of goods available in the colony, which is supported by this list of debts. Fifteen of the traders to whom Dr Martin owed money were located in the inner city, ten of them located on, or adjacent, to Collins Street (Figure 6.1). This was the prime shopping street of the city in the 19th century where, by mid-century, traders carried a wide range of imported goods in fashionable shops, including household wares, furniture, clothes and jewellery (Priestley 1984:23–26). Generally the ‘streets’ were considered a moral and physical hazard, but Collins Street was elegant and refined: a respectable place for ladies (Russell 1993:29, 1994:65). According to Clara Aspinall (cited from Russell 1994:65), ‘Here all things are conducted calmly, quietly, harmoniously’. Being seen on Collins Street, and spending appropriate amounts of money on fashionable goods, was an important part of genteel public performance for women: an activity in which the Martins clearly engaged. Dr Martin would have purchased items while in the city for work, while the Martin women would have spent afternoons promenading and browsing the shops. This exclusive and fashionable area provided a pleasurable shopping experience. The city shops frequented by the Martin family in the 1870s included drapers (Figure 6.2), chemists, wine merchants, grocers, ironmongers, a coal merchant, shoeing smith, saddler, bootmaker and an importer of china and glass ware (Table 6.2). Dr Martin owed considerable sums of money to a number of these traders.54

Table 6.2: Listing of unsecured debts to traders in a statement of duty regarding Dr Martin’s will (PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 17, File 12-586, 11 February 1875), including details on traders from Sands and McDougall’s Melbourne Directories (1874).

| Trader Name | Type | Location | Amount owing | Reference | Notes | ||

| ₤ | s | d | |||||

| Graham Bros. & Co. | Merchants | 91 Little Collins St, Melbourne | 728 | 14 | 5 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 471 | James Graham is listed as ‘Graham, Hon. James’ |

| Alston & Brown | Drapers (Silk Mercers, Drapers, Outfitters, Carpet Warehousemen & c.) | 47 Collins St West, Melbourne | 219 | 4 | 8 | Sands and McDougall 1874: ii | |

| Shields & Co. | Cornfactors (Flourfactors and Grain Crushers) | corner Elizabeth and a Beckett Sts, Melbourne | 104 | 7 | 4 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 661 | |

| Wm. Godfrey | Wine (and Spirit) Merchant | 97 Collins St West, Melbourne | 70 | 5 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 470 | |

| John Sharpe | Timber Merchant | 44 | 19 | 1 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 659 | There is a John Sharp listed as a timber merchant at 151 Collins Street West. There is also a John Sharpe listed in Heidelberg, but no trade is given | |

| A. (Archibald) Davidson | Grocer (and Wine) Merchant | 112 Collins St East, Melbourne | 44 | 9 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 422 | |

| C. (Charles) W. Watts | Butcher | Heidelberg | 10 | 12 | 11 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 713 | |

| Oldfield & Lindley | Timber Merchants (and Steam Sawmills) | Elgin, Station and Nicholson Sts, Carlton, and Nicholson and Argyle Sts, Fitzroy | 5 | 6 | 11 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 607 | |

| George Studley | Baker | Heidelberg | 1 | 3 | 11 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 683 | This is the only Baker by this name |

| Briscoe & Co. | Ironmonger (and Iron Merchants) | 11 Collins St East, Melbourne | 5 | 10 | 6 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 375 | |

| Whitney, Chambers & Co. | (Wholesale) Ironmongers | 7 Swanston St, and cnr. Collins and Swanston Sts, and 103 Flinders St East, Melbourne | 1 | 11 | 1 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 721 | |

| By Lee | Ironmonger | 1 | 4 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 541 | This could be Benjamin Lee, Ironmonger at 177 & 179 Bourke St. East, or Lee, E & Co. Ironmongers 71 Bourke St West | |

| W. (William) R. Hill | Chemist (and Druggist) | 63 Collins St East, Melbourne | 5 | 1 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 500 | |

| Charles Ogg | Chemist (and Druggist) | 117 Collins St East and Gardiners-ck Rd. | 2 | 6 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 606 | |

| W.H. Lamond | Coal (and Grain) Merchant | 65 Flinders St East, Melbourne | 6 | 10 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 536 | ||

| J. (John) Holmes | Saddler | 72 Bridge Rd | 7 | 2 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 503 | There is also a John Holmes, Nurseryman, in Heidelberg 55 |

| Vines & Carpenter | Shoeing Smiths (and Farriers) | 53 Little Collins St West, Melbourne | 4 | 2 | 6 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 704 | |

| T. (Thomas) Hodgson | Blacksmith | Heidelberg | 6 | 5 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 502 | This is the only T. Hodgson listed |

| E. Forster | Saddler & c. | 1 | 6 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 852 | Under saddlers there is an L. Forster at 31 Postoffice Place | ||

| William Lea | Saddler | 34 Swanston St, Melbourne | 2 | 13 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 540 | |

| E. (Edward) Ryan | Bootmaker | 96 Swanston St, Melbourne | 1 | 15 | 0 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 649 | |

| Dunn | Grocer | 3 | 15 | 11 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 438 | There are many listings under Dunn. This may be Frederick Dunn, Storekeeper at Heidelberg. Alternatively it may be T. Dunn, Grocer, in High St, Wr (?) or Terence Dunn, Grocer, in Sydney Rd, Coburg | |

| Crofts | Cheesemonger | 4 | 6 | 2 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 415 | This is possibly the Provision Merchant at 40 Swanston St, Melbourne | |

| Klingender & Charsley | Solicitors | Bank Place, Collins St West, Melbourne | 33 | 4 | 8 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 533 | |

| (John) Stanway | Crockery (Importer of China and Glass Ware) | 175 Bourke St East, Melbourne | 5 | 19 | 9 | Sands and McDougall 1874: 661 | |

In the second half of the 19th century, the rise of shopping arcades, and later, department stores, in inner-city areas stylishly accommodated middle-class shoppers (Kingston 1994:26). Arcades and department stores catered to the middle class and were out of the price range of working-class consumers (Crook 2000:19–20). Arcades incorporated a range of elegant shops protected from the elements, and the first in Melbourne was Queen’s arcade in 1853, with a number of others following. By the 1860s, window displays of tempting goods lured pedestrians from the sidewalks into the shops (Brown-May 1998:52). Around the world, in the second half of the 19th century, many general stores and draperies developed into department stores (Kingston 1994:27–28). While this process in Sydney has been well documented, little historical work has been done for Melbourne. The evolution of department stores is difficult to trace in historical records in the absence of extensive research in the area. A number of stores, such as draper and haberdasher Buckley and Nunn which was established in 1852, gradually expanded into department stores although exactly when this took place is unknown (Priestley 1984:135).

The Martins also purchased goods close to home. In Heidelberg, not far from Viewbank, there was a shopping village named Warringal which comprised a number of shops by 1848 providing the basic needs of daily life to residents in the area. Shops included a butcher, baker, miller, shoemaker, wheelwright and blacksmith, along with a brickmaker and a plasterer (Garden 1972:73). The statement of duty indicates that Dr Martin had debts with a butcher, baker and blacksmith in Heidelberg and possibly a timber merchant, nurseryman and storekeeper (Table 6.2). Heidelberg was also a market-gardening area, with fresh produce including fruit, vegetables and grain crops readily available for purchase by the Martin family (Garden 1972:71–72). The Martins purchased the necessities of daily life for Viewbank from Warringal in local markets and shops, although they were probably shopped for by a servant.56

Figure 6.1: Collins Street in 1864. Briscoe and Co. Ironmongers where the Martin family purchased goods can be seen on the right side of the street (Creator: Unknown; Source: State Library of Victoria).

Figure 6.2: Alston and Brown, one of the drapers in Collins Street frequented by the Martin family, 1864 (Creator: Frederick Grosse 1828–1894; Source: State Library of Victoria).

57Some affluent Australians ordered household goods and personal items directly from London stores to avoid the physical environment of shopping and to get the most up-to-date items (Kingston 1994:25). Also, trade catalogues were used extensively by people who lived remotely from cities and towns (Pollon 1989:233–234; Allison and Cremin 2006). It is difficult to determine from artefacts whether the item was ordered by the consumer from a trade catalogue or purchased from an Australian shop. For example, a toothbrush from the Viewbank tip bears the name of a London chemist ‘GEO…LEWIS CHEMIST// PEARL CEMENTS/ …ENT/ LONDON’ and was possibly ordered directly from London, but may have been purchased from a local distributor who imported the item.

Archaeological indicators of where goods were purchased are largely limited to items such as buttons or combs that have shop names marked on them. No shop names were identified on artefacts in the Viewbank assemblage. Crook (2000:24) suggests another way of using artefacts to view purchasing behaviour, namely that at a general level, the mix of luxury and poor quality items in working-class assemblages might be the result of the influence of affordability and availability of second-hand goods in market bazaars. The converse of this would be to assume that cohesion in an assemblage, such as matching sets of tableware, and a consistent level of quality across an assemblage, would indicate shopping in centralised arcades, department stores and by mail. This certainly appears to be the case for the Martin family. In the Viewbank assemblage, 11 matching sets of tableware and three complementary sets (including similar but not identical vessels), were identified along with nine matching sets of teaware and three complementary sets. This indicates that they were able to purchase a large number of vessels at one time. It would also have been possible for them to make follow-up purchases of vessels in the same patterns at a later date. A large number of high quality drinking glasses were recovered: 13 tumblers and 25 stemmed glasses. Cut glass vessels, either in simple or elaborate patterns, were a prestigious item, superior to moulded vessels (Jones 2000:174). Almost all of the stemmed drinking glasses and tumblers at Viewbank were cut glass. Also, three ewers and a chamberpot, with flown black ‘Marble’ decoration, were recovered from the tip. Not only were there matching toilet sets, but these sets also matched between bedrooms.

The adaptation and recycling of objects can be seen as an indicator of the necessity to make do when the availability of goods is limited, either through financial access or availability in the marketplace. Objects may be adapted from their original form to serve another purpose or repeatedly reused until worn out. For example at the remote sawmilling community of Henry’s Mill in south-west Victoria, domestic recycling was identified in a variety of ways including glass bottles reshaped into storage jars, and kerosene tins adapted for various uses (Davies 2001b:161). No evidence of reuse or recycling such as this was identified in the Viewbank assemblage. This supports the notion that the Martin family had access to a wide range of goods and could afford to buy what they required for daily life.

CONSUMER PRACTICE

English goods dominated the Viewbank assemblage for two reasons: first, because of their availability in the colony, and second, because of a social preference for them, or a desire for them because of their familiarity. While it is important to note that English-manufactured goods do not necessarily indicate English values or beliefs (Symonds 2003:153), the Martin family may well have sought to maintain ties to England. Trading power and dominance were not the only factors; there was a demand for goods which enabled and expressed the values, behaviours and beliefs of gentility (Young 2003:7–8).

Items from Continental Europe may well have been specialised objects not commonly available from England, or in some way superior to English products, for example French cognac and German dolls. Similarly, goods from China added some exotic items to their possessions. While some Australian goods were available to the Martin family, there is little conclusive evidence in the archaeological record for their presence on the site. It is impossible to determine whether this was because Australian-made goods were unmarked at the time or because the Martin family had a preference for imported goods, although the former seems most likely. Overall the assemblage reflects general colonial trade networks and the strong social and economic ties the colony had with England in its first 50 years.

The Martin family purchased goods in two distinct areas: near home and in the city centre. Necessity and convenience dictated that food and items for daily life be purchased nearby in Heidelberg, and occasionally in Melbourne. There is also some evidence that a garden, orchard, and dairy operated at Viewbank and may have supplied the family (see discussion in the next chapter). Household and personal goods were largely sourced from faraway 58places, yet purchased for the most part in the genteel atmosphere of Collins Street. There is no evidence that the Martins were shopping in the suburbs between Heidelberg and the centre of Melbourne, or any other suburbs. This implies that the social networks of the Martins, and the activities of the family, centred on these places.

The Viewbank assemblage appears to indicate that the Martins could afford the goods they wanted, imported or otherwise, and purchased them in the shopping environment they chose. The sizeable debts that Dr Martin owed to various stores suggest that price was of little hindrance to the purchasing behaviour of the family and that he had the status and wealth necessary to maintain credit at a number of stores. They shopped in ways perceived as fitting for the middle class, and shopping formed a significant part of the family’s participation in ‘genteel society’. Not restricted by lack of money, and with access to the full range of goods available in the colony, the Martins’ consumer practice reflects their class position.