7

Daily Life at Viewbank Homestead

Gentility was expressed through various aspects of daily life. This chapter examines the lives and lifestyles of people at Viewbank via the material culture and historical records, with a view to discussing in chapter 8 how gentility was used in class negotiation. This chapter first examines how the homestead and surrounds functioned spatially in relation to the daily happenings at Viewbank. This is followed by a discussion of work and leisure for both the Martins and their servants, perhaps the most significant aspect of daily life at Viewbank. Dining and social events were the most comprehensive aspect of daily life revealed by the material culture, and are examined here in detail along with religion, childhood, genteel appearance and health.

SPACE

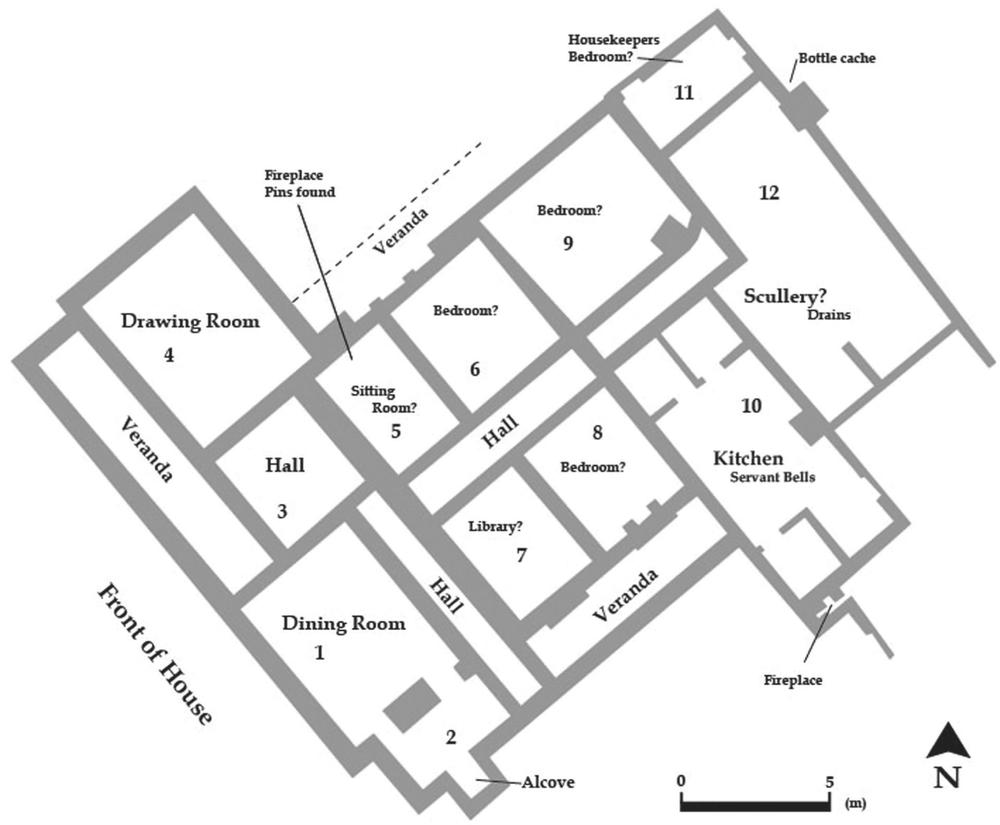

After the two phases of extensions, the completed Viewbank homestead had 12 rooms (Figure 7.1). Historian Judith Flanders (2003:lii) observed that houses of the lower middle class usually had four to six rooms, while those of the upper middle class had around 12. The house was surrounded by extensive terraced gardens with plantings of European trees and was entered via a set of stairs flanked by Italian cypresses. Its position, size and grandeur communicated status. Inside, space was structured to facilitate the negotiation of daily activities both along public versus private and gender lines. Space was also organised to separate the activities of servants from those of the Martins and visitors to the house.

Figure 7.1: Plan of Viewbank homestead showing room uses (Source: adapted from plan prepared by Heritage Victoria).

60The gender divide that dictated much of 19th-century life also determined the spatial arrangement of family living spaces. For the man of the house, home was a private arena where he could express his control and command. For women, the home comprised all aspects of their lives: service, reproduction and nurturing (Hourani 1990:74). Consciously or unconsciously, the spatial arrangement of a house influences its occupants, formulating and reinforcing gender relationships (Hourani 1990:70). Traditionally, in the 19th century public areas of the house were at the front, and if seen as masculine they communicated dominance over the private or feminine areas to the rear of the house. Elements of this are suggested by the spatial layout of the archaeological remains of the homestead at Viewbank.

A hall for receiving, a drawing room for entertaining, and a dining room for eating were the public rooms displayed to outsiders (Flanders 2003:xxv; Young 2003:175). These rooms communicated the success and status of the occupants, and the greatest expense was used to fit and furnish these rooms (Flanders 2003:xxviii). The floor plan revealed by excavation at Viewbank can be interpreted using historical information on typical layouts and architectural features to suggest the use of each room and layout of the homestead (Figure 7.1).

The many-roomed Viewbank homestead suggests there were rooms for specific functions. At the front of the homestead, room 1 appears to have been the dining room and room 4 the drawing room. Room 3, between these rooms, would have been the transitional zone of the hall. Room 2, separated by two doorways to the southeast of room 1, may have functioned as access for the servants to serve food. Other houses of the era also had a drawing room and dining room flanking a large hall (Broadbent 1995:54; Carlin 2000:94). These three public rooms served the specific functions of entertaining, eating and receiving (Young 2003:175).

Excavations have revealed that rooms 1 and 4 had marble fireplaces, wallpaper and large decorative cornices contributing to a formal atmosphere. The fragments of marble recovered from room 1 were black, some with plaster rendering still attached, while the fragments in room 4 were pale grey, black veined marble. This provides further evidence that room 1 was the dining room and room 4 the drawing room. John Claudius Loudon in his 1843 advice manual for furnishings recommended ‘… that a white marble chimney piece was the most elegant for a drawing room, whereas coloured stone or marble was preferable for the dining room and library’ (Loudon 2000). This pattern is observable in Australian historic houses from the 19th century where dark coloured decoration was associated with men and pale colours with women (Mitchell 2009:117). These conventions were based on rules of taste that dictated feminine furnishings for the drawing room and masculine for the dining room (Flanders 2003:215; Toy and Griffin c.1990:1). This was influenced by the post-meal tradition of men remaining in the dining room for port and cigars, while the women retired to the drawing room for tea and conversation (Lawson and Carlin 2004:96). Wallpaper fragments were also excavated from the drawing room and the hall.

This front section of the homestead was quite separate from the private sleeping and service areas behind. This demarcation between the public areas and the private rooms for the family members was important, as was separation of both of these areas from the rooms for servants (Flanders 2003:xxv).

Often the segregation of men and women continued in the private areas of the house, with a private sitting room for the women and a library or office for the man of the house. The sitting room was a 19th-century addition to houses and was used for the express purpose of leisure (Bushman 1993:256). The sitting room was explicitly feminine and was busy with sewing, needlework, painting, sketching, flower arranging and music. At Viewbank, a concentration of 17 pins was recovered from the front room of the original Williamson house in the front of a fireplace (room 5, Figure 7.1). Fourteen of the pins were complete and only three broken. This indicates that sewing activities being carried out in this room. This may, therefore, have been the Martin’s sitting room. It is possible, however, that the pins were dropped by James Williamson’s mother or sister prior to the Martin’s arrival.

One of the rooms at Viewbank may have functioned as Dr Martin’s private library or study. A man of business would require such a room even if he had an office elsewhere. As with the sitting room, the library or study was gender defined (Young 2003:185). Women were excluded from this space, where the man of the house would set about scholarly or business activities. Traditionally the library had a strongly masculine character with furnishings that were darker in colour creating a masculine aesthetic (Lane and Serle 1990:134).

If room 5 was a sitting room and room 7 a library, it is likely that the remaining three rooms (6, 8 and 9) in the centre of the homestead were bedrooms (Figure 7.1). Fragments of wallpaper were excavated from room 9 and the hallway adjacent to it, which may suggest that this was a bedroom and not a service room. As the largest of the three rooms, this may have been Dr and Mrs Martin’s bedroom. It is likely that the Martin children shared the remaining two rooms.

A controlled physical environment was established for servants and was perhaps an attempt to contend with the constant invasions into the private and personal space of the employers (Russell 1994:169, 172). Housework conducted by servants was largely done at the rear of the house beyond the sight of 61visitors (Bushman 1993:262), and the kitchen, scullery and servants’ bedrooms were divided from the rest of the house (Flanders 2003:xxv). Servants’ low status was clearly communicated through their relegation to cramped, badly ventilated, out-of-sight areas of the house (Hourani 1990:74).

The relegation of service areas to the back of the house, while reflecting the lower status of servants, can also be seen to indicate the comparatively lower status of the women of the house than the men (Hourani 1990:74; Yentsch 1991:207). Historical evidence suggests that middle-class wives and daughters were involved in domestic duties within the home (Hourani 1990:74). Mrs Martin would have been responsible for household management and would have spent time in the service areas of the house supervising and organising the domestic servants. Daughters would assist with domestic duties and would sometimes take over the household management duties of their mother. Wives and daughters would sometimes work together in the house alongside the servants (Russell 1994:154).

The presence of servants meant that middle-class women had to negotiate class boundaries in the home and uphold important social distinctions within the house. The threat of the influence of the lowly morals of the working class, especially on children, was a serious concern and servants were expected to maintain standards of decorum. As such, Mrs Martin’s ability to take firm control was vital (Davidoff and Hall 2002:395) and the housekeeper would have helped with negotiating daily interactions with the other servants.

The service area at Viewbank was situated at the back of the homestead. The second extension to the homestead added three rooms for this purpose (rooms 10, 11 and 12, Figure 7.1). Room 10 appears to have been the kitchen, with small rooms at either end for the scullery and pantry. The large number of servant bells recovered in this room indicates that it was the room where the servants spent most of their time; therefore, it is most likely to have been the kitchen. Room 12 at the back of the homestead had a system of drains in place, and therefore may have functioned as a scullery. Water pipes usually ran into the scullery where water was used for kitchen and laundry duties. Piped cold water was in use in grand houses in England by the 17th century, but only made its way into middle-class homes in the 19th century depending on water supply (Flanders 2003:91). While water supply was available in many Melbourne suburbs in the 1860s it was not connected in Heidelberg until 1889. However, the area had an abundance of creeks and rivers with most big properties having a water frontage. Water could be pumped from the river and stored for use, as was the case at nearby Banyule Homestead in the 1850s, however, there is no record of how Viewbank was supplied with water (Garden 1972:105, 165).

This second extension at the back of the homestead was clearly inferior in construction to that at the front. The floor in these service rooms was concrete, in contrast to the floorboards used in the remainder of the homestead. Concrete, in use from the earliest years of the Port Phillip district, was becoming more refined in the second half of the 19th century and was readily accepted as fireproof flooring (Lewis 1988:3–5). Hardwearing surfaces such as concrete were usually confined to corridors and service areas in the 19th century (Webster 2004:37). If they had any floor covering these were usually equally hardwearing.

The large hall at the front of the Viewbank homestead which conveyed status to visitors became much narrower at the rear of the homestead. This separated the ceremonial and utilitarian areas of the house (Ames 1978:28), and also reflected and defined the status of the servants. Also, it was possible to enter each room from the hall which allowed the servants to carry out their duties without disturbing the family (Ames 1978:28). When tasks such as cleaning, making beds and bringing in firewood were required in the public and private spaces of the house, negotiation was essential to establish the times this would take place (Russell 1993:30; Griffin 2004:50). When guests were present, the occasional, appropriate appearances of servants functioned as a necessary display of wealth and gentility. Servants were expected to answer the front door to visitors, and at other times were summoned from the rear of the house by servant bells. The servant bells at Viewbank were located in the kitchen (room 10) with bell pulls throughout the house (see discussion in chapter 5). Each of the bells was designed to make a different chime so that the servants knew where in the house they were required.

It is not clear, however, where the servants slept at Viewbank. In smaller houses domestic servants sometimes slept in the kitchen, while in larger houses they slept in rooms at the rear or upper levels of the house (Flanders 2003:1). Room 11 at the rear of the Viewbank homestead may have been the housekeeper’s bedroom as it was a small room with wallpaper (Figure 7.1). There may have been other bedrooms at the rear of the homestead in an area not uncovered by excavations, or in an adjacent building. Servants were often housed in a separate building in grand homes of this era (Dyster 1989:102–103), and outbuildings were mentioned when the Viewbank property was leased in 1875 (PROV, VPRS 460/P, Unit 1102, 1 June 1875). It is possible that at least the male servants were housed in an adjacent building.

The spatial arrangement of the homestead at Viewbank structured and facilitated the daily undertakings of both the Martin family and their servants. It follows the norms of society at the time and reflects the values of the day in terms of the roles of women and men in the domestic 62environment. The activities of the servants and their daily interactions with the Martins were carefully planned and managed through the spatial layout of the homestead and the use of servant bells. Their status and position was clearly communicated through space.

WORK

For the middle class in the 19th century, not to work came to be considered poor behaviour (Young 2003:17). Middle-class men had to work to support their families; unhindered leisure was not possible. It was therefore convenient for middle-class people to view work as noble and a signifier of good character. It was nevertheless important to separate work from home, and this can be seen to distinguish the middle class from the working class. Working-class homes of early Australia were often the site of work and income generation. Women took in laundry and sewing at home to earn money. Bakeries and butchers were also run from home, and women often ran hotels and lodging houses (Karskens 1999:53–56). This was not the case for the middle class. Some work, however, if it was not dirty, noisy or requiring a large work force, could be carried out at home (Davidoff and Hall 2002:366).

Although there is little archaeological or historical evidence for exactly where Dr Martin worked, it is possible that he had an office in the city and also did some work at home. The three pens and ink bottle in the Viewbank tip may have been used by Dr Martin for his work. It is likely that, on some occasions at least, he wrote business correspondence at home. Dr Martin may have also practised medicine from Viewbank at some point. It was not unusual for doctors to see patients in a segregated room of the house, and it is possible that Dr Martin did this at Viewbank. The Sands and McDougall’s Melbourne and Suburban Directories from 1868 to 1871 list Dr Martin under ‘Physicians, Surgeons and Medical Practitioners’ at Viewbank. However, there is no archaeological evidence to support this; no surgical equipment was found in the tip and medicine bottles were only in numbers adequate to supply the family.

The middle class valued work, yet it was still not appropriate for middle-class women to work for income (Young 2003:18). As a result, various activities became valued as work for women: managing the house, raising children and philanthropic volunteer work. Only the very upper levels of the middle class could afford enough servants to make domestic work unnecessary for the women of the family (Flanders 2003:xxx). It is likely that Mrs Martin’s work involved managing the domestic servants employed at Viewbank and raising her children. The Martin daughters may have also undertaken some domestic work.

A Workplace for Servants

To the Martin family, Viewbank was home, but to the servants it was a workplace. Servants in larger households were employed in a range of tasks and were differentiated by their titles (Higman 2002:129). Job titles for female servants included housekeeper (who was in charge of all other female servants), general maid, housemaid, cook, laundress, lady’s maid, seamstress, nursemaid, governess and dairymaid. Male servant titles included butler, manservant, coachman, groom, and gardener. Most essential to employ was a general maid, then housemaid, cook, general manservant or coachman, and another maid for sewing or attending the women (Young 2003:55).

At Viewbank, the housekeeper Jane Warren would have been in charge of a number of indoor servants. In addition, a groom and coachman were probably also employed and the extensive gardens likely required the employment of at least one gardener. As discussed in chapter 3, a total of between 6 and 18 servants were employed.

Domestic service was the largest employer of women in Australia. Even after commerce and industry became an attractive alternative from the 1860s, in Melbourne almost half of working women were servants (Anderson 1992:231; Evans and Saunders 1992:182). However, the ‘servant problem’ was a common topic among Australia’s middle class (Anderson 1992:231; Russell 1994:167). Servants were scarce, and those in the cities were generally recent arrivals who were highly mobile and had a frustrating propensity to marry (Anderson 1992). Melbourne’s middle-class women frequently complained of expensive, unreliable and obstinate servants (Russell 1994:181–186). However, hard unpleasant work, long hours, and high expectations by employers were the plight of the servants. There was also the strain of being isolated from family and friends, and under the constant supervision of an employer who would meddle in their moral and spiritual life (Anderson 1992:235).

Some of the artefacts recovered from Viewbank may, in fact, have belonged to or have been used by the servants. The majority of artefacts, however, were recovered from the tip which would have been used by both the Martins and their servants. Therefore, the association of artefacts from the tip with the servants is difficult and somewhat speculative. The various tools and the whetstone recovered from the tip may have been used by the servants as part of their daily chores. In addition, the female servants may have used some of the sewing equipment in their work. Most housemaids were expected to do an hour and a half of needlework in the afternoon (Flanders 2003:101), and in some households a seamstress was employed.

Of the large number of matching sets of table and teaware recovered from Viewbank, some would have been used by the servants. The Martins may have 63purchased one or more matching sets of ceramics for their servants such as the complementary Willow and gilt banded vessels. In addition, quality ceramics may have been handed on to servants if damaged or no longer wanted (Connah 2007:259). It is difficult to determine from the archaeological record, however, which method of acquisition was used (Brooks 2007:195), and is further complicated at Viewbank by the fact that the majority of the ceramics were recovered from the tip.

Regardless of these complications it can be inferred that the servants most likely had one or possibly more sets, and that these would be the cheapest and simplest sets in the assemblage. The cheaper ‘Rhine’ set and complementary ‘Willow’ vessels are likely to have been used by the servants. In her study of hierarchy at Government House in Sydney, Casey (2005:109) suggests that one type of service was used by the servants for almost all meals.

The four clay pipes are more likely to have been used by the servants than the Martin family. In the 19th century, clay pipes became associated with the poor: labourers, Irish people and convicts; the middle and upper classes preferring briar pipes, cigarettes, cigars and snuff (Walker 1984:4; Gojak and Stuart 1999:40; McCarthy 2001:150). Walker (1984:6), when discussing smoking in Australia, suggests that while some smoking could be done while at work, for the most part it was considered a leisure activity.

Farming Activities

Viewbank was more than just a home and showplace for gentility. Some farming activities were also carried out at the homestead, and probably employed servants and farm hands. Small Australian farms in the 19th century usually had a house cow for milk and butter, and a kitchen garden (Vines 1993:4). It is interesting that Viewbank, as the residence of a wealthy pastoralist, appears to have functioned as a small farm.

Records suggest that in Victoria it was not only rural homesteads like McCrae homestead on the Mornington Peninsula that had dairies and conducted farming activities, but also properties that were of commutable distance to the city. Como House in South Yarra conducted subsistence farming including the growing of fruit and vegetables, along with dairying. Also, Hubert De Castella (1861:104), who established a grand homestead on the Yarra not far from Viewbank, recorded that ‘to take full advantage of it required setting up a good dairy, bringing on thin horses which were bought cheaply in town, training bullock teams, dairy cows and so on’. He recorded that he had up to 120 cows and that dairy production supplemented his income (De Castella 1861:115). He also later turned to winemaking.

Heidelberg’s fertile soil and proximity to Melbourne made it a prominent supplier of agricultural produce to Melbourne. Serious and regular floods destroyed crops in Heidelberg and competition from better-serviced producers to the south of Melbourne led to a decline in Heidelberg’s agricultural success. In the 1850s and 1860s, market gardening and agricultural activities in the area decreased, and many in the area turned to pastoral activities including dairying and grazing (Garden 1972:72–73, 105, 110).

The assemblage indicates that dairying was conducted at Viewbank. A minimum of six milkpans, used for separating cream from milk, were recovered from the Viewbank tip. While this number of milkpans does not suggest large scale commercial dairying, it probably indicates that dairying was undertaken for more than home use. In his book on English dairy farmers, Fussell (1966:2) suggests that it was not unusual for a wealthy gentleman or farmer to have a small herd of cattle for milking. At Viewbank, a barn, stackyard for hay, and cattle were listed as part of the property when it was leased in 1875 (PROV, VPRS 460/P, Unit 1102, 1 June 1875). Women were usually responsible for producing dairy products (Casey 1999:3), and it is possible that dairymaids were employed at Viewbank.

In Melbourne as early as 1838, dairying and produce farming were being encouraged in Fitzroy, Collingwood and Richmond (Godbold 1989:3). Although a small number of specialised dairy farms emerged early on, dairying was predominantly left to small farmers to supply their local district (Vines 1993:8) and this may have been the role of dairying at Viewbank. As land near Melbourne became scarce, farms on the city fringe supplied dairy produce to the city (Vines 1993:7). Dairying emerged as the dominant industry in Heidelberg from the 1860s to the 1880s. The Martins’ involvement in this local industry is further evidenced by Willy becoming the co-founder of the Heidelberg Cheese Factory Company in 1871 (Garden 1972:121). The Viewbank property went on to become a large scale dairy when Harold Bartram purchased it in the early 20th century.

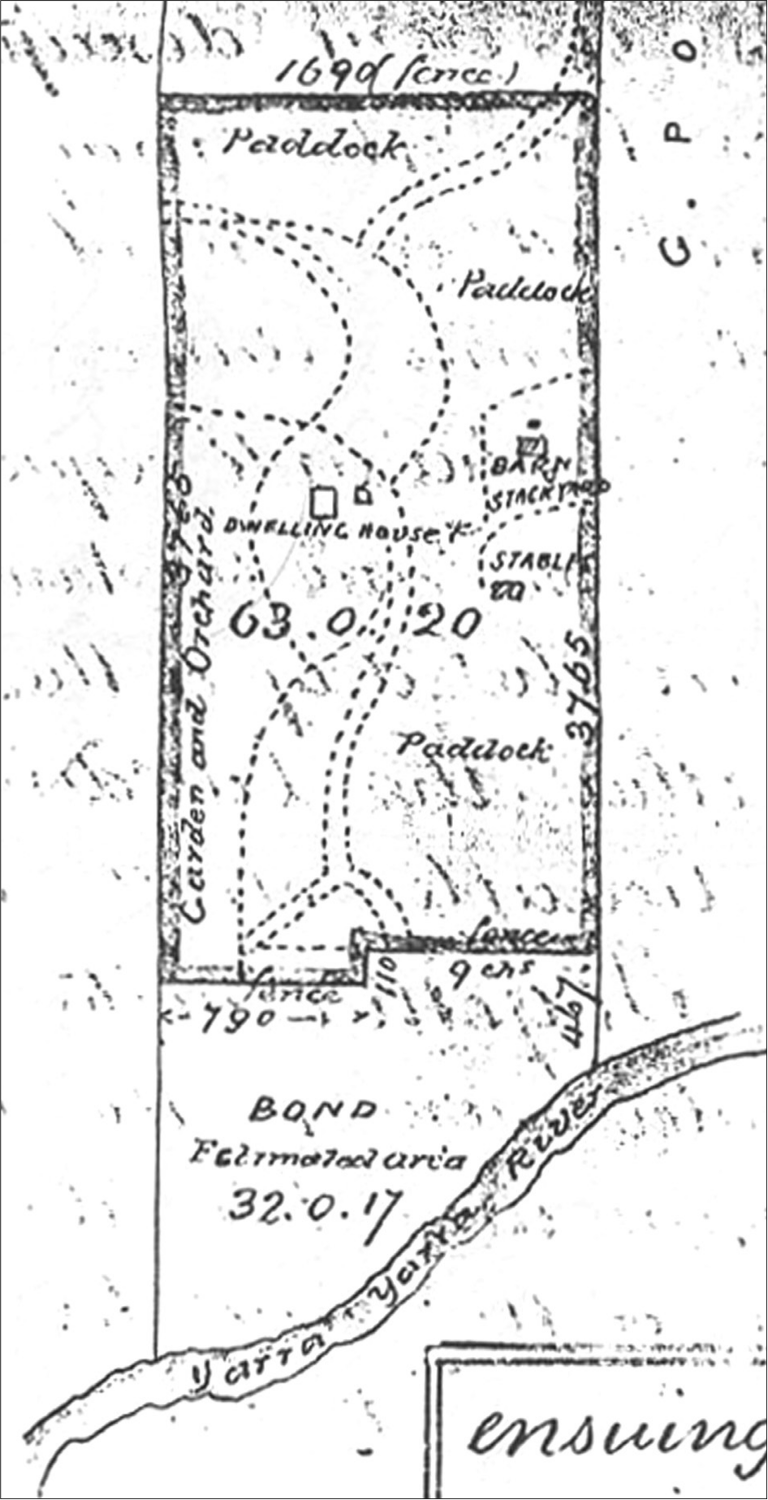

In addition to dairying, a plan on a lease document dating to when Mrs Martin moved from Viewbank in 1875 details that there was a ‘garden and orchard’ established at Viewbank along with paddocks (Figure 7.2) and there is mention elsewhere of an orange grove beside the river (Garden 1972:44). Orchards and market gardens were needed to provide the daily needs of the early colony (Vines 1993:4). Small mixed farms often incorporated an orchard to supply fruit and jam for the household, or for additional income. Orchards were frequently combined with dairying in higher rainfall areas to the north and east of Melbourne (Vines 1993:12). In his history of Heidelberg, Donald Garden (1972:109) records that during floods in the 1860s Dr Martin lost crops at Viewbank, which supports the view that some crop farming was also undertaken. 64

Figure 7.2: Detail of the plan of Viewbank from the 1875 lease showing the dwelling house, barn, stackyard and stables (Source: PROV, VPRS 460/P, Unit 1102, 1 June 1875).

Viewbank was as much a place of work as a home. Domestic work was conducted by both servants and the Martin women, and Dr Martin may have also carried out some incidental business or medical work. Further, Viewbank operated to some extent as a working property. It appears that both farming, food gardening and dairying activities were taking place and that these activities may have been for income as well as for home consumption. In the context of the growing settlement in Port Phillip this was not unusual. The large size of the estates at Heidelberg, and the fact that many of the occupants had extensive country pastoral runs, made farming activities a natural choice (Garden 1972:50). In the Australian context, this presented no challenge to gentility.

LEISURE

Leisure for the middle class was not always about relaxation and pleasure, but also self-improvement and health. Some of the leisure activities at Viewbank homestead are suggested by the artefacts, particularly activities for shared family evenings. Such artefacts included dominoes, die and gaming counters. Domino sets come with varying numbers of tiles and it appears that the five dominoes from Viewbank are from one set. Dominoes and dice are both used to play a variety of games, with dice also sometimes used for gambling. A copper alloy fish figurine (Figure 5.16) may have been a gaming counter. Bone fish shaped counters were used for games from around 1840 or even earlier (Bell 2000:14).

These shared evenings were part of the refined lifestyle of the middle class and reflected ideals of domesticity. Other activities, not revealed by the assemblage, such as reading and music playing probably took place at Viewbank. Reading aloud was an important skill and was a pastime centred in education (Russell 1994:157). This was also true for playing music. In many cases reading and music were an accompaniment to the needlework of the women. Images of drawing room scenes from the era often show men reading in relaxed poses, while women sit with their needlework.

For women, it was important to keep the ‘hands busy’. The primary evidence for this from the Viewbank assemblage is in the form of needlework equipment. While painting, sketching, flower arranging and music were probably also important leisure activities for the Martin women, they are less likely to be detected in the archaeological record. Such activities were a tribute to talent and leisure, but were in fact rather arduous forms of leisure (Russell 1994:97).

Sewing is often seen as a necessary source of income for working-class women in the 19th century, while in contrast it is viewed as a leisure activity for middle-class women (Lydon 1993b; Karskens 2001:80). Embroidery and decorative needlework in particular were a symbol of feminine, leisured lifestyle: an index of gentility (Lydon 1993b:129–130). However, through the 19th century increasingly more working-class women were doing needle crafts for leisure, and there is some evidence for this at Casselden Place in inner Melbourne (Porter and Ferrier 2006:387–388).

It is likely that both leisure and necessity motivated the needlework at Viewbank. The numerous pins are most likely to have been used for sewing, but could have been used for a range of needlework. It is also possible that they were used to fasten clothes (men’s or women’s), or fasten documents (Beaudry 2006:8). The pins and thimbles found at Viewbank may have been used by the housemaids who were expected to do some sewing each day, or a seamstress. The four thimbles were 65simple and undecorated indicating that they were utilitarian items. Utilitarian needlework, overseen by the woman of the house, would have included sewing, mending, and remaking garments, sheets and linens (Beaudry 2006:5). The Martin women would have done fancy needlework in the presence of guests, and when making calls on the women of other households to demonstrate their abilities in the feminine arts (Beaudry 2006:5, 106). At other times, in private, practical needlework like mending or knitting socks would be done (Mitchell 2009:230). Only less well-off women would make dresses and other large items of clothing: the well-off would do only mending (Flanders 2003:223, 265).

In the 19th century, almost all daughters, regardless of class, were taught to sew by their mothers (Beaudry 2006:105). The presence of a child-sized thimble in the Viewbank tip suggests that this was the case. Social expectations demanded it, and not doing so could bring disapproval (Parker 1984:9).

Embroidery was one of the most popular forms of fancy work and came to represent femininity as well as a genteel and leisured lifestyle from the 18th century (Beaudry 2006:4). As Parker (1984:11) explains:

embroidery was supposed to signify femininity – docility, obedience, love of home, and a life without work – it showed the embroiderer to be a deserving, worthy wife and mother. Thus the art played a crucial part in maintaining the class position of the household, displaying the value of a man’s wife and the condition of his economic circumstances.

Parker (1984:14) also draws attention to the fact that women were not passive participants in this, but drew satisfaction from embroidery.

The three lace bobbins recovered from the tip indicate that the luxury item, lace, was being made by hand at Viewbank. Although machine-made lace was available in the second half of the 19th century (Sykes 1988:3–4), it appears from archaeological evidence that hand-made lace was still popular. Beaudry (2006:151–152), in her research on needlework and sewing, suggests that while some lace was made by genteel ladies as a delicate art, lace-making was also an important cottage industry in Britain and its colonies well into the 19th century. It is difficult to determine whether the Martin women made lace as genteel leisure, or a servant was employed in this task.

The bone netting needle found in the Viewbank tip indicates that delicate items, such as doilies, were being made by netting, a similar technique to tatting. This was another form of fancy needlework for leisure. Also, decorating button moulds with fabric was a distinguished pastime for Victorian ladies (Iacono 1999:53), and had a practical outcome. Interestingly, fabric covered buttons were the most common button decoration in the Viewbank assemblage.

The only possible evidence for the leisure activities of the men from the Viewbank assemblage was in the form of hunting and shooting. These activities were considered cultivated and useful pastimes for men, much like drawing and needlework were for women (Young 2003:17). Three .50 calibre cartridges dating from 1846 and one shotgun cartridge dating from 1850 were recovered from the tip. These may be the result of hunting activity, but it is unlikely that they would have been discarded in the tip. Rather, they were probably discarded during hunting or shooting.

Of the range of possible leisure activities at Viewbank, sewing is the most visible in the archaeological record. The record also suggests that games and hunting were leisure pastimes at Viewbank, and a range of other activities not suggested by the archaeology, such as music and art, would also have formed an important part of daily life for families such as the Martins.

GENTEEL DINING

Food and tea service provided an opportunity for the display of both wealth and the subtle range of behaviours associated with gentility (Fitts 1999; Young 2003:182). In the words of Mrs Beeton (1861:905) in her book on household management: ‘The rank which a people occupy in the grand scale may be measured by their way of taking their meals.’ Each type of meal and each course within it required the table to be set in a genteel manner using the appropriate tableware. A well set table for genteel dining was orderly, aesthetic and fashionable and was one of the most significant platforms for displays of gentility.

A beautifully set table was part of the dining experience. Historical records tell us that Mrs Martin had inherited a Spanish mahogany dining table (Niall 2004:30). This may have been covered with a baize table cover for heat protection and a white damask cloth for the meal to be served on (Lawson and Carlin 2004:96). Each course of a meal had to be facilitated by the appropriate tableware. The breakfast table was also set in a prescribed way, and although services were smaller they also had purpose-specific vessels.

Perhaps the most important aspect of genteel dining was the use of matching sets to present an orderly meal (Wall 1994:147–158; Fitts 1999; Young 2003:182). Of the ceramic tableware vessels recovered from the tip, 38.6 percent were part of a matching set and at least 11 individual sets of tableware were represented. Nine of the sets included both consuming and serving vessels, while the white granite ‘Berlin Swirl’ set was the only matching set with table and teaware vessels. A further 23.4 percent of the tableware vessels were possibly part of three complementary sets. These 66vessels were in common decorations which were similar but not identical. Such vessels were likely purchased on an ad hoc basis and may or may not have subsequently been used together as a set (Lawrence et al. 2009:75). There were also matching sets in the teaware, with 31.7 percent of the teaware being part of at least nine matching sets. An additional 41.3 percent of the teaware vessels were possibly used in five complementary sets.

Having the appropriate set for each type of meal was an important part of genteel dining. A middle-class family would have sets for everyday use, separate sets for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and best sets (Fitts 1999:52; Young 2003:182). Wealthy households would also have cheaper ceramics for use by servants (Spencer-Wood 1987:16). The use of different sets distinguished the level of importance of each meal, for example to contrast a Sunday dinner from a weekday dinner (Wall 1994:146). While it is impossible to determine the exact type of meal that a set was used for from the archaeological record, it is possible to speculate on the use of each set in the assemblage in order to facilitate interpretation. To do so, it is useful to draw on historical accounts of what meals entailed.

In British culture, there were three major types of dinners: weeknight dinners, Sunday dinners and dinner parties (Mitchell 2009:126). On weeknights, adult members of the family generally dined alone in the dining room, children in the nursery, and servants in the kitchen. Children and servants generally received simple meat and potato meals (Flanders 2003:225), with the adult family members meals being more substantial and varied. The quantity and variety of matching sets recovered from Viewbank suggest that the Martins were indeed using different sets for different meals and possibly supplying servants with a separate set or sets.

A set such as the blue transfer print ‘Queen’s’ pattern or the Mason’s Chinese pattern may have been used for the formal weekday dinners of the adult members of the family held in the dining room. Sunday dinners were comparatively more elaborate affairs, and dinner parties more so again with the needs of all guests being accommodated by the service of numerous dishes (Flanders 2003:236). The larger and relatively more expensively decorated ‘Summer Flowers’ set was likely one of the Martins’ best sets and may have been used for Sunday dinners or when receiving guests. It is possible that other expensive sets were taken by Mrs Martin when she left Viewbank or given to the Martin children and are not present in the archaeological record.

Breakfast and lunch were less formal affairs but still required their own tablewares. In the Victorian era, breakfast was served early and usually included one hot meat dish and toast with tea (Flanders 2003:225). The ‘Bagdad’ [sic] and ‘Clematis’ sets of plates may have been for breakfasts. Men would have lunch at the club or at work, while women and children would have a light cooked lunch at home often utilising leftovers (Flanders 2003:225; Mitchell 2009:126). The less expensive sets such as the ‘Asiatic Pheasants’ and ‘Rhine’ sets may have been used to serve lunches.

As noted above, some sets may have been for use by the servants while other sets may have been multi-purpose. Casey (2005:104) found evidence that simply decorated banded, moulded or plain vessels in tea and tableware forms were multipurpose sets not designated to lunch or dinner.

The number of tea sets also suggests their use for different purposes: when guests called, between meals and by servants. The sprigged and geometric transfer-printed sets may have been used for taking tea between meals. The gilt banded and tea leaf teawares had variations and were recorded as complementary sets, but may in fact represent a series of larger sets in these popular patterns. As with the tableware, the cheaper sets such as the ‘Marble’ pattern and any complementary sets were likely used by the servants.

The relative absence of tea service vessels such as teapots and creamers in the assemblage is likely because of the use of a silver tea service which would not be found in the archaeological record. As silver has an intrinsic value in spite of changing fashions it is likely that any silverware would have been retained by Mrs Martin or handed down to one of her children.

The Viewbank assemblage shows that genteel dining and tea service were part of everyday life, not just when receiving guests. Breakfasts, lunches and servants meals in the Martin household all bore the hallmark of gentility, but with a less elaborate air than when guests were in attendance.

The Viewbank dining and tea service assemblage is consistent with the use of a variety of different matching sets for different meals and occasions, but within sets genteel dining also required a wide range of vessel forms, many with specific uses (Shackel 1993:30–42; Fitts 1999:54). Different sized plates along with specialised serving vessels such as soup tureens and sauce boats can be associated with more elaborate table etiquette (Yentsch 1991:221). A standard dinner service could include 80 to 140 vessels with a range of plate sizes, sauce tureens, soup tureens, platters, serving dishes, butter dishes, pitchers and gravy boats (Fitts 1999:182; Young 2003). A large variety of forms were recovered from the Viewbank tip.

Of the 11 matching tableware sets, eight had more than one vessel form, and of the three possible complementary sets all had multiple vessel forms. The 10-inch or table plate was the most common in the Viewbank assemblage, closely followed by the 9-inch supper plate and 8-inch twiffler. A smaller number of soup plates and 7-inch muffin plates were represented. The larger plates would have 67been used for main courses while the smaller plates may have been used as side or dessert plates, or possibly breakfast or afternoon tea service. Single-function vessels included soup tureens, sauce tureens, ladles, drainers, serving dishes, platters and egg cups. Six vessel forms were identified in the tea service assemblage: teacup, saucer, mug, teapot, jug and serving dish. Overall, this represents a wide variety of vessel forms, many of which were purpose specific.

Good taste and therefore fashion were important aspects of gentility, and there is evidence in the Viewbank dining and tea service assemblages that the Martins were keeping up with fashions. Archaeological evidence suggests that Australians preferred colourful table settings, particularly transfer-prints, in accordance with British and British colonial tastes (Lawrence 2003:25, 26; Brooks 2010), and this is reflected in the Viewbank assemblage. Of the dining assemblage, 58 per cent of the vessels with identifiable decorations were colourful including transfer-prints and flow transfer in blue, black, green, grey, purple and with additional colourful enamelled or gilt decoration. A further 26 per cent of the assemblage had gilt decoration and 23 per cent were plain, moulded and white granite vessels. A similar pattern was represented in the tea service vessels with 53 per cent having colourful decorations including transfer-prints, hand-painted vessels, flow transfers and multiple decorations. There was a higher percentage of gilt decorated vessels at 38 per cent, and a slightly lower number of plain and moulded vessels at 18 per cent. With regard to fashionable patterns, the ‘Summer Flowers’ set and other vessels with enamelled decoration were the height of Victorian fashion: busy and dark toned. A number of popular patterns such as Chinese scenes, classical scenes, ‘Rhine’, ‘Asiatic Pheasants’ and ‘Willow’ were also represented. Further, plain or simply decorated white granite was a relatively more expensive and highly fashionable ceramic type in the United States from the 1850s (Majewski and O’Brien 1987:120–124; Miller 1991:6; Ewins 1997:46–47). Its popularity was largely the result of its association with the sanctity of churches, and contrast to capitalist markets (Wall 1992:72). However, it is not clear whether this association carried across to Australia. Many Staffordshire potteries made ceramics specifically for the United States market, and when the American Civil War commenced in 1861, had to find alternative markets for these wares (Brooks 2005:58–59). The white granite vessels in the Viewbank assemblage date tightly to the start of the Civil War. It is unclear whether white granite was marketed as the latest fashion in Australia or sold off cheaply after the United States market contracted. Without a comprehensive study for Australian preferences similar to those done by Samford (2000) or Majewski and Schiffer (2001) for the United States market, it is difficult to determine the changing fashion in patterns over time in Australia (Brooks 2005a:34).

Evidence of keeping up with fashion is, however, present in the dates of the ceramic tableware recovered from Viewbank, which indicate that they were updated regularly. Two sets may have been brought to Australia by the family or purchased in their early years in Victoria: the ‘Summer Flowers’ set which was manufactured between 1830 and 1859 and the Chinese transfer-printed Masons plates which were made in Staffordshire between 1820 and 1854. These two, slightly older sets, may have been discarded when the Martins left Viewbank rather than passed on to the Martin children. These were updated with ‘Bagdad’ pattern plates made between 1851 and 1862 and white granite vessels purchased in the early 1860s. A debt to John Stanway for crockery in 1874 indicates that they were still purchasing ceramics in their last years at Viewbank (PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 17, File 12-586, 11 February 1875). Perhaps one of their final purchases while at Viewbank was a ‘Rhine’ plate which dated to after 1869. Only one maker was identified on the ceramic teawares, Liddle, Elliot and Son who manufactured ceramics between 1862 and 1871, so patterns of purchasing could not be determined in the same way as for the tableware. However, the decorative techniques and purchasing patterns for the ceramic tableware indicate the Martins’ interest in keeping up with fashion.

Matching sets of cutlery were also a part of genteel dining (Young 2003:181). Two of the cutlery items recovered from Viewbank were in the popular ‘Fiddle’ design and may have been a set. The Martins would have almost certainly had one or two silver cutlery sets. Again, cutlery items could be purpose-specific, but the small cutlery assemblage reveals little of this except for the handle of what might have been a mustard spoon.

A number of glass vessels also complemented the ceramics at the table. Six glass serving dishes and three glass bowls were found, and were probably used to serve condiments and side dishes. These were all press-moulded or cut glass and were highly decorated. Three glass jugs may also have been for serving sauces. A stemmed colourless dessert glass was a purpose-specific dessert vessel.

Drinking glasses were also an important part of a well set table. At Viewbank, a minimum of 13 tumblers were recovered from the tip, far fewer than the 25 stemmed glasses. This is unusual: as Jones (2000:224–225) argues, tumblers are usually the most common glass tableware form recovered from archaeological sites. It is difficult to determine whether tumblers as opposed to stemmed glasses have different status connotations. Stemmed drinking glasses were used for wine, champagne, claret and cordial while tumblers were used for ale, whiskey, soda water, lemonade and iced tea (Jones 2000:224–225). Wine was considered more genteel 68than beer or hard liquor which may explain the predominance of stemmed glasses. Alternatively, it may be the result of stemmed glasses being preferred for drinking at the table, and tumblers away from the table (Yamin 1998:83). While the pattern may simply be the result of the higher breakage rate of fragile stemware, it is likely that it represents a preference for stemmed drinking glasses.

The drinking glasses recovered from the Viewbank tip were of a high quality. Almost all of the 25 stemmed drinking glasses were cut glass. Cut glass vessels, whether in simple or elaborate patterns, were a prestigious item (Jones 2000:174). Jones (2000:224) suggests that by 1840 the variety of stemware styles began to increase, and this is reflected in the Viewbank assemblage. Patterns included cut panels, facets or flutes, and alternating facets and flutes on the bodies and stems. These were common decorations for 19th-century glassware (Jones 2000:174). As with the stemware, the majority of the 13 tumblers from the tip had cut decoration in panels, flutes, or alternating flutes, panels or mitres. Panels were the most common decorative motif on tumblers in the 19th century (Jones 2000:225) and this is reflected at Viewbank. A minimum of two tumblers have similar decorations, but were pressed imitations of cut glass. Five of the tumbler bases feature a star or sunburst. The Martins’ preference for the more expensive cut glass drinking glasses is indicative of their ability to afford these items in large numbers.

Wine was readily available from the very early years of the Port Phillip district, and the Yarra Valley, the location of Viewbank, was a popular wine growing region (Beeston 1994:49). The presence of a corkscrew in the assemblage supports the drinking of wine at Viewbank. The 11 wine bottles and many of the 106 beer/wine bottles also support this, although there is no way of confirming whether the family purchased alcohol in these bottles. One bottle each of gin, cognac and whiskey indicate that at least some spirits were being consumed. Also, two decorative, colourless glass stoppers were from decanters which probably held alcohol.

The historical records present something of a contradiction on Dr Martin’s attitude to alcohol. Dr Martin was one of about 100 people who signed a petition in an attempt to prevent Henry Baker, publican of the Old England Hotel in Heidelberg, from obtaining a licence in 1849. The petitioners were concerned that the hotel would promote drunkenness, immorality, disruption to the Sabbath and neighbourhood (PROV, VPRS box LD3). However, when his daughter Charlotte married, Dr Martin provided ‘Barrels of Ale … for all comers’ (HHS 1862). The archaeological evidence suggests that the Martins partook of alcohol as part of their genteel dining.

A variety of matching sets with a range of vessel forms in good taste were necessary to meet the specific genteel requirements of each meal. It would appear that breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea and dinner were each catered for with the appropriate tableware, flatware and glassware at Viewbank. The appropriate use and display of table settings, in line with appropriate social protocol, was as important as its acquisition (Burley 2000:404).

SOCIAL EVENTS

Social events were an important part of genteel performance and included calls, dinner parties, balls, parties and weddings. In the archaeological record, a large quantity of quality tableware in an assemblage indicates that the tools required for entertaining were available (Yamin 1998:82). The array of ceramic tableware and number of matching sets indicate that dinner parties would have been well within the means of the Martin family. Also, the 25 stemmed glasses in a variety of shapes and the 13 tumblers in the Viewbank assemblage are suggestive of a large enough collection of drinking glasses to host parties.

The layout of the Viewbank homestead is also suggestive of the way the Martins entertained at home. The dining room was regarded as a public space and the location for dinner parties. This room was formal and dominated by a large dining table. Further, the presence of a drawing room, such as the one at Viewbank, was an English adaptation specifically designed for social interaction (Davidoff and Hall 2002:377). This was where the family would entertain guests and gather to play games, read or have prayers.

The historical record shows that the Martins did, on occasion, throw large and lavish parties at Viewbank (Niall 2004:33). A 1933 article on Dr Martin states: ‘Dr Martin entertained freely, and is well remembered by a few old residents for his famous Christmas parties’ (Heidelberg Relief Organisation 1933). Hosting a party often involved rearranging the house so that more rooms could be used for the entertainment of guests (Russell 1994:74; Young 2003:74–75). Decorations and flowers would adorn the whole house, while music and food completed the event. A letter from Edward Graham to James Graham in 1855 states:

We had merry times about New Year. A magnificent ball at Dr Martin’s being the long-promised house heating. Dr Youl, the son-in-law to be, being a most efficient master of ceremonies. Then we had a ball at the McCraes’, evening parties here, at the Davidsons’, here and at the Butlers’, and Randall’s farewell bachelor party at the Port Phillip, Capel’s farewell and lastly Randall’s wedding (Graham 1998:46).

69This was a busy schedule. Regular parties formed a central part of Melbourne society.

Paying calls, a female domain, was essential to the establishment and maintenance of networks in society. Imported from Britain, the system and etiquette of calls were rigid and important for the ‘established middle class’ including the Martins (Russell 1994:50). Calls were made out of courtesy to new acquaintances or as a thank you for hospitality. They were also made as congratulations, upon a birth or marriage, or condolence at the death of a family member. Tea would be served, and calls would last from 15 to 30 minutes (Mitchell 2009:151). The best matching sets of teaware, possibly the flow and enamelled floral set or the ‘Florentine’ set, would have been used at Viewbank when receiving calls, and probably a silver tea service. Women would often take embroidery or fancy work with them when calling on the women of other households (Beaudry 2006:106).

The correct timing and circumstance of calls was an important part of etiquette and failing in this was met with disapproval. Upon the marriage of Annie Martin, Edward Graham wrote to James Graham ‘The Martins have been very odd about it. Mrs Cobham never was asked to the wedding and has received no cards. Neither have I, although except as your brother they might have been sent.’ It appears that the Martin women were neglecting their social roles. The strain of constant calls could be exhausting, visiting a number of families in an afternoon two or three times a week (Russell 1994:51). This would have been particularly frantic after a celebration, but clearly disapproval was easily acquired.

Another important part of paying calls was the leaving of cards. Cards were left to issue invitations, respond to invitations, or to send condolences or congratulations. It was important that cards be left in person, and this was the responsibility of the women of the household. Therefore, this functioned as another expression of the availability of leisure time and a display of status (Ames 1978:43). The hall was the location for this ritual, and as such the size of the hall and the quality of the furnishings within conveyed status to all visitors (Ames 1978:27). At Viewbank, the hall was ample enough to accommodate the full range of hall furnishings including a hall stand, card receiver, chairs and a settee.

Weddings were another important social event and were celebrated with lavish ceremonies and parties. The elaborate celebrations for Charlotte Martin’s wedding to John Fenton overtook the whole of Heidelberg:

An arch decorated with flowers and evergreens was erected at the entrance to the Church ground: the Church itself being densely crowded to witness the ceremony which was performed in an impressive manner by the Rev. J. Lyner …

The fair Bride attracted universal attention, even in the midst of a bevy of Bridesmaids. A salvo of artillery from the Racecourse announced the tying of the Nuptual [sic] Knot and, on leaving the Church, children dressed in white scattered flowers before the happy pair (HHS 1862).

When Willy Martin married Minnie Graham in 1874, James Graham wrote of the lavish event to former Governor Charles La Trobe:

We had a great gathering of old friends. Of the number invited exactly 100 accepted and we sat down 97 to breakfast. The Church was beautifully decorated … All our friends vied with each other in sending us really cartloads of choice flowers and branches and actually trees loaded with oranges and blossoms for our decorations. The day was lovely and in a word everything passed off as well as we could possibly wish (GP 19 May 1874).

These events and social occasions were an essential part of genteel performance and the functioning of the middle class in Melbourne.

RELIGION

There was a strong association between the middle classes and a Christian way of life. Religious observance was necessary and included church attendance, family worship, observance of the Sabbath and interest in religious literature (Davidoff and Hall 2002:76). The absence of religious artefacts in the Viewbank assemblage does not indicate a lack of faith of the Martin family, who historical records show were practicing Anglicans.

Historical records show that Dr Martin was trustee of St. John’s Church of England in Heidelberg, which he helped to establish. Work commenced on building the church in 1849 and it opened in 1851 (Garden 1972:68). The vicar complained that Dr Martin interfered with parish matters although rarely attended church (Garden 1972:97–98). Conflict arose because Dr Martin expected influence for his patronage, which displeased the vicar (Niall 2004:33). It seems his role in the church had more to do with standing in society than devout belief. Religion gave aspirational men a sense of self-respect and an air of decency (Young 2003:81). With his Scottish background it is surprising that Dr Martin was Anglican, and this suggests the power of the Church of England as an establishment church.

To a large extent, mothers were responsible for the spiritual guidance of their children. Religion was tightly connected to morality and respectability and these were important lessons for children. Suggestive of Mrs Martin’s interest in the religion of her children is that she gave her daughter Lucy a 70Bible upon her marriage (Niall 2002:33). Of course it is difficult to determine what this reflects in terms of devout belief versus a customary gift.

It is not surprising that symbolic religious objects were not found in the Viewbank assemblage. It was not appropriate for middle-class Anglicans to display crucifixes or other religious paraphernalia. Catholics were much more likely to display religious items and jewellery and these are often found on archaeological sites (Mezey 2005:91; Davies in press).

Religious belief could be subtly communicated through household items. Middle-class women became responsible for creating the home as a moral sanctuary suitable for raising their children with the values of gentility and Christian morality (Fitts 1999:39). There is some evidence in the Viewbank assemblage that Mrs Martin did this, in the form of fashionable tableware, matching toilet sets and flowerpots. However, it is difficult to define this as Christian belief as opposed to genteel values.

In the United States, historical archaeologists have associated Gothic style with the middle class and Christian belief. Fitts (1999:47) argues that Gothic style in architecture, furniture, perfume bottles, pickle bottles and tableware became fashionable in the United States reflecting Gothic churches (ideal places for Christian nurture). Di Zerega Wall (1992:79) suggests that white granite vessels in Gothic shapes were popular because of their association with the sanctity of churches and contrast to capitalist markets. However, there is little evidence that this association was taken up in Australia. Both pickle bottles in Gothic shapes and ‘Girard’ white granite vessels are present in the Viewbank assemblage. However, as discussed in chapter 6, this is likely to be the result of the availability in Australia of goods intended for the American market.

There is no way of knowing what the Martins’ religious activities were in terms of daily prayers and bible reading, or whether their servants were expected to attend church. However, what can be gathered from the historical and archaeological record is that while the Martins gave the outward appearance to those around them that they were Anglican, there is little suggestion that they were devout in their belief. For them religion may have been more about society and appearances (Young 2003:81).

CHILDHOOD

In the 19th century, childhood was seen as a precious phase of life and children were treated as individuals who were innocent and unspoiled (Davidoff and Hall 2002:343). There is some suggestion that child-centredness was even more pronounced in middle-class families in Australia than in Britain (Maynard 1994:109). In the archaeological record, child-centredness can be reflected in children having individual possessions and designated space. In the Viewbank assemblage one clear example of this was Willy’s mug, gilded with his first name Robert (Figure 5.5).

With regard to space, it was seen as ideal that children be given their own rooms where possible (Praetzellis and Praetzellis 1992:92). In reality, the large families of the 19th century made it difficult to give each child a separate room. In this case boys and girls were separated, and ideally also older children from younger children (Flanders 2003:xxv). In addition, it was common in England to have a nursery for the use of children (Davidoff and Hall 2002:375), however this was not common in Australia (Kociumbas 1997:94, 114). Hourani’s (1990:76) study of Australian middle-class homes of four to 15 rooms indicates that, generally, children’s bedrooms were much smaller than the master bedroom and that there was no nursery. It is likely that the Martin children shared two or three rooms at Viewbank.

Another group of possessions for children, and part of changing attitudes to childhood in the 19th century, were ‘moralising china’ vessels. These were tableware and teaware items specifically for children, which had educational or moral phrases and decorations (Karskens 1999:141). At Viewbank, a mug with gilt lettering reading ‘A Pres… for// A good …’ was found and was almost identical to the mug marked ‘Robert’. Mugs with the phrase ‘A present for a good girl [boy]’ were for rewarding and encouraging good behaviour (Karskens 1999:141). The popularity of these items has been noted on many working-class Australian sites from the 19th century (Karskens 2001:76; Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004a:104).

It also appears that certain expenditure was made on children’s toys at Viewbank. Most of the toys dated closely to the Martin period of occupation suggesting that the toys were of the latest fashions. Also, the dolls and the matching set of dolls teaware would have been relatively expensive to purchase (Ellis 2001:48). The Martin children may well have had more expensive toys than these, as toys of significant value and expense would not have been discarded.

Toys and games became increasingly popular from the 1830s and also indicated attitudes to childhood as a separate phase of life marked by innocence and play (Karskens 2001:179). Some of the toys found at Viewbank were purely for fun, such as two marbles. Marbles were purchased in large lots and were easily lost. In her archaeological study of children’s play, Wilkie (2000:102) suggests that children were more likely to make the effort to retrieve large or ornate marbles. Other toys for fun found at Viewbank were four cap gun cartridges, and a crayon.

In many cases toys were about more than play: when purchased by adults, they represent attempts to enforce and encourage certain behaviour (Wilkie 2000:101). Toys were used to teach manners, 71domestic duties and consumerism. For instance, toy tea sets were used to teach table manners (Fitts 1999:54), and also the correct purchasing of the tools required for genteel dining. At Viewbank, a press-moulded doll’s tea set comprising a teacup, two saucers, teapot and sugar bowl were found. Toy tea items have also been recovered from working-class urban sites from the 19th century (e.g. Karskens 1999:179; Godden Mackay Logan et al. 2004b:298–299). For girls, toys were also used for learning about domestic duties like sewing and laundering (Praetzellis and Praetzellis 1992:92).

Most 19th-century dolls depicted adults, and their aim was to enforce female identity (Wilkie 2000:102). Adult dolls could also be used to educate regarding fashion and etiquette. Some of the jointed dolls at Viewbank had heeled boots and there is some suggestion that heeled boots date to after the 1860s (Pritchett and Pastron 1983: 332). This would suggest that the dolls were purchased for the Martin girls in their teenage years, the youngest daughters being 14 and 16 in 1860.

There is some archaeological evidence that the Martin children were educated at home in the form of 12 slate pencil fragments recovered from the tip. These represent a minimum of two pencils, but probably more. Slate pencils and writing slates were cheap and durable writing implements often used for educating children (Iacono 1999:78; Ellis 2001; Davies 2005:64) and again this is suggestive of investment in children (Yamin 2002:118). It is possible that the Martin family employed a governess to teach the children. Compulsory schooling was not introduced in Victoria until 1872 (Ellis 2001:17–18), but it is also possible that the Martin children were sent to the school in Heidelberg. Education was clearly important to the Martins, at least for their son. The historical records show that Willy was sent to Cambridge for his higher education (De Serville 1991:318). Both play and education were a vital part of raising children along genteel guidelines.

GENTEEL APPEARANCE

Fashion and correct taste in clothes were important mechanisms in defining status and class in the new colony of Melbourne (Russell 1994:80). There is significantly more evidence of this for the women of Viewbank than the men, and this reflects the higher importance of fashion and appearance for women at this time.

Masculine Appearance

Personal appearance was a vitally important part of successfully developing connections in the genteel world of the 19th century. To play the part, a man had to look the part and men communicated their status through their clothing. Dress for middle-class men in Australia was as important, and essentially the same, as in Europe. However, a greater variety was noted by contemporary testimonies (Maynard 1994:82–83). A photograph of Dr Martin (Figure 3.1) shows that he wore a high stand collar and tied stock which left much of his crisp white shirt showing. Unfortunately the date that this was taken is unknown.

At Viewbank, artefacts possibly relating to masculine appearance included buttons, clothing fastenings and part of a boot. It is difficult to determine which of the buttons in Viewbank assemblage were from men’s clothes and which were from women’s as decorative buttons were used on the clothes of both sexes. The military buttons recovered from Viewbank with anchors and Prince of Wales feathers were most likely from military uniforms or men’s clothing. Military buttons were advertised in Sears and Roebuck catalogues and used on civilian clothing (Israel 1968:320). Some of the small buttons (8–15 mm) may have been used for men’s underclothing, shirts and waistcoats (Birmingham 1992:105). Other closures in the assemblage may have been cuff links or men’s clothing fastenings. A stacked heel from what appears to be a man’s boot may have belonged to one of the Martin men.

Feminine Appearance

When appearing in public it was vitally important for women to present and define themselves as ladies (Russell 1994:79). A number of personal items in the Viewbank assemblage suggest this: six items of jewellery, beads, possibly some of the buttons, hook and eye fastenings, possible suspender belt and undergarment fastenings, three perfume bottles, and a brisé fan. It is impossible to determine whether these items belonged to Mrs Martin or her daughters. They do, however, indicate that some, or all, of the women of the house placed particular importance on their appearance.

Many of the buttons in the Viewbank assemblage were likely to be from the clothing of Mrs Martin and her daughters. Nine fabric covered buttons were found in the Viewbank tip and one in the homestead contexts. Around the 1860s, it became popular to match the fabric on the button to that of the garment, particularly for women’s dresses (Albert and Kent 1971:47–48). Three fancy buttons with a flower in the centre were also likely to be from women’s clothes. The majority of the Viewbank buttons were small, possibly because undergarments and shirts had more buttons than outer garments, which frequently used hook and eyes.

Women’s close fitting outer garments and bodices commonly used hook and eye fastenings (Kiplinger 2004:7–8), which were identified in the Viewbank assemblage. Women’s clothing, particularly corsets, restricted mobility. Bending or picking things up was not possible while in a corset. This made it clear that others were employed to do most of the required work; as such the middle-class woman became, to some extent, an object signifying her 72husband’s wealth (Green 1983:130). Furthermore, the complexity of women’s clothes meant that it was necessary to have a maid or relative to help fasten them (Fletcher 1984:77–78). In spite of concerns about the physical damage caused by corsets and high-heeled shoes they continued to be popular throughout the 19th century (Green 1983:120–128).

A number of changes in women’s fashion took place over the 30 years that the Martin family lived at Viewbank. Keeping up with changes in fashion was vitally important to displaying the correct appearance and status. Clothes for special occasions were either imported from Europe, or made locally, but still closely followed the Paris and London fashions (Maynard 1994:85).

In addition to clothing, jewellery was a way of enhancing personal appearance and displaying wealth. On a daily basis a pendant or brooch would probably be the only jewellery worn, with more elaborate pieces saved for social occasions (Young 2003:169–171). While the archaeological record indicates the importance of personal appearance, it also suggests that the Martin women did not lose or discard expensive jewellery. The brooches recovered from Viewbank were copper-alloy-based brooches, which would have been inexpensive and mass-produced. Some, more valuable, gold items were also found: a fine gold chain which may have carried a locket or watch, part of a gold earring, and a small gold loop, probably a connecting piece from a necklace or bracelet. All of the jewellery items were broken suggesting that they were discarded for this reason and none had a precious stone still in place.

The Martin women would have had more valuable jewellery than that represented in the archaeological assemblage. The lack of them in the archaeological record is likely because of care taken with precious items, and the resetting of precious stones when an item of jewellery broke or went out of fashion. Also, as suggested by historical records, valuable items were passed down through the generations. For example, the de Guzman pearls, which Mrs Martin inherited from her mother, were passed down to Lucy Boyd and then to her daughter Lucy (Niall 2004:30).

Beads can have many uses including jewellery, rosaries, clothing decoration and lace-making bobbin spangles, making their actual use difficult to confirm. However, it is possible that the eight beads recovered from Viewbank represent items of jewellery. Notable among these are seven matching black beads. Rosary beads were often made of black glass and, although predominantly associated with the Catholic Church, were sometimes used by Anglicans. Black beads were also often used for mourning jewellery.

Of the two spectacle lenses recovered from Viewbank one was oval in shape and sight-correcting and the other circular and not sightcorrecting. Spectacles were often decorative, rather than functional, as they were seen as giving an air of dignity (Iacono 1999:72). Women often used long gold chains to hold spectacles, tucked in a pocket (Young 2003:171). There was a fine gold chain in the Viewbank assemblage, possibly used with one of the pairs of spectacles.

Fragments of a bone brisé folding fan carved with a floral design were found at Viewbank (Figure 5.7). Demure and genteel, folding fans were popular throughout the 19th century, especially at balls. In addition to their decorative purpose, fans were used to attract attention, flirt and communicate. As Beaujot (2012:63) states: ‘There is little doubt … that women used fans to their advantage as performative accessories that opened up social possibilities; the colour and design of fans that were expertly deployed could attract the interest of those around them.’

The use of scent as part of personal presentation was a luxury the Martin women could afford. Three perfume bottles were recovered from Viewbank, two of which were imported from London, made by John Gosnell & Co., a perfume and soap maker who advertised themselves as the perfumer of the royal family (Gosnell 2006).

The appropriate display of mourning was another important aspect of personal appearance. There were at least two periods of mourning at Viewbank during the Martins’ time there. One period was after Charlotte, her husband John Fenton and their two children were killed in the wreck of the steamship London in the Bay of Biscay on 11 January 1866 (HHS 1866, GP 20 March 1866). The other was after Dr Martin died in 1874. The large proportion of black buttons, along with the seven black beads, in the Viewbank assemblage may have been from mourning clothes and jewellery. The precise details of the period and depth of mourning for various relatives were important (Russell 1994:120). In addition to mourning attire for a family member, black buttons and beads were particularly popular after 1861 when Queen Victoria went into mourning for Prince Albert (Lindbergh 1999:54).

Presenting the correct appearance in all regards was a vital part of the display of gentility for the middle class in Melbourne. The nuances of fashion required great effort to ensure that one’s appearance remained genteel and not vulgar (Russell 1994).

HYGIENE AND MAINTAINING HEALTH

The immaculate body, and control of the body, were also genteel ideals (Bushman 1993:63). This included controlling physical appetites, checking emotions, hiding bodily functions and maintaining cleanliness with the goal of mental and spiritual purity (Young 2003:96). Hygiene became an important part of daily life, a fact reflected in the Viewbank assemblage. 73

Advisory literature in the 19th century recommended washing daily either in a bath, or a sponge bath for the face, neck, groin, hands and feet (Flanders 2003:288–289; Young 2003:97). A basin and ewer in the bedroom, accommodated on a custom-built washstand, allowed for washing in the privacy of the bedroom. Sponge baths, hip baths and shower baths became increasingly popular from the 1830s on, as interest in cleanliness and the health-giving properties of water grew (Young 2003:100–102), while bathrooms began to emerge in the later part of the 19th century (Flanders 2003:286).

Complete toilet sets of the period included: basin, ewer, soap dish, sponge bowl, toothbrush jar, and slop pail (Young 2003:98), and double toilet sets were available for shared bedrooms. Matched toiletry vessels indicate a desire for symmetry and continuity in private areas of the house as well as public (Praetzellis and Praetzellis 1992:91). At Viewbank, three ewers and a chamberpot, all with flown black marble decoration, were recovered from the tip. This suggests that the sets matched between bedrooms as well as within them. Casey’s (2005:108) investigation of inventories from Government House in Sydney has revealed that high status families would have matching sets for themselves and their guests while servants would have odd sets.

Excretion was carefully managed with chamberpots. Distaste for excretion was dealt with by hiding it in a chamberpot, sometimes with a lid, in a purpose built cupboard, drawer or chair (Young 2003:109). Four chamberpots, all decorated with flown transfer-printed patterns were recovered from the Viewbank tip. In addition to the black ‘Marble’ printed chamberpot, other chamberpots included one with a blue ‘Marble’ print, another with a floral and another with an unidentified print. A further two vessels may have been chamberpots, but were too fragmentary for this to be confirmed.

In addition to washing, oral hygiene was part of the discipline of daily life. Purpose-made toothbrushes were introduced in the late 18th century and became increasingly mass-produced and widespread throughout the 19th century (Young 2003:104). This daily discipline was clearly important in the Martin family: 16 toothbrushes were found in the tip. Also recovered was a cherry toothpaste jar, one of the most popular 19th-century toothpastes (Pynn 2007). The jar depicted Queen Victoria in profile and was probably made by John Gosnell & Co.

Grooming of hair and nails were also important. Hair was not washed frequently in the 19th century because of fear of catching cold. Instead, brushing the hair for long periods of time, a number of times a day and dressing it with perfumed oils was advocated (Young 2003:104–105). A vulcanite comb was found in the Viewbank tip as were two brush handles which may have been hairbrushes. Also, a Macassar oil bottle was found: a popular treatment for healthy hair for both men and women, but most commonly used by men. Further, a rectangular wooden brush found at Viewbank was either a cloth or hand brush. Cloth brushes were used to removed dust and hair from clothes, while hand brushes were used to clean the hands and fingernails.

A small number of ointment jars were also recovered from the Viewbank tip. These included an undecorated whiteware, shallow ointment jar and lid, along with a cobalt blue glass ointment jar lid. Their exact contents were not clear, but they may have contained ointments for the skin or cosmetics.

It is likely, given Dr Martin’s medical background, that both prescription and proprietary medicines were used at Viewbank. Nineteen glass bottles recovered from the Viewbank tip were identified as medicine bottles, based on their shape. None of these bottles bore a maker’s mark so it is difficult to determine whether the contents were prescription medicines, or proprietary medicines, or indeed medicine bottles at all. Bottles dispensed by chemists often used paper labels and bottles were taken back to the store for re-filling usually with the same, but sometimes a different, medicine (Knehans 2005:45). Four glass bottle stoppers with disc and flat oblong heads recovered from the tip were of a type commonly used for druggists’ bottles (Jones and Sullivan 1989:153–156). Two cobalt blue bottles probably held castor oil, used as a purgative or for colds and flu (Davies 2001a:71). A third cobalt blue poison bottle was embossed with ‘not to be taken’. Other medicines may have been used, but have left no trace in the archaeological record. Medicines were often sold in tins, boxes and packets which are less likely to survive in the ground (Graham 2005:52).

In the mid-19th century, doctors often treated patients in perilous ways with heavy doses of drugs, bleeding and purging (Davies 2001a:63). These treatments probably did more harm than good, but it is hard to know how much the families of the sick questioned these methods. In the second half of the century there was growing concern over who could call themselves doctors. Many practitioners in fact had little or no qualifications. In 1862, the Medical Practitioners Act was passed to enforce controls on who could practice and how (Knehans 2005:42).

As an alternative, Australians were keen users of self-dosed proprietary medicines, many of which were imported (Davies 2006b:352). Although the Martin family probably used prescription medicines and medical techniques when required, proprietary medicines were likely used to maintain health and wellbeing. It is very difficult to distinguish between prescription medicines, proprietary medicines and others from bottle shape alone. In the 19th century, there was much blurring between the boundaries of prescription and proprietary medicines. Although medical practitioners predominantly treated patients and prescribed medicines, while chemists 74prepared and dispensed them, there was overlap in these roles (Knehans 2005:41). Chemists would often diagnose customers and recommend the medicines they had prepared (Hagger 1979:167). Six chemists or druggists were already open in Melbourne in 1842, and by 1860 this number had grown to 88 (Knehans 2005:42). The Martin family had accounts with two chemists in Collins Street (PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 17, File 12-586, 11 February 1875).