7

Repatriating childhood: issues in the ethical return of Venda children’s musical materials from the archival collection of John Blacking

Repatriating childhood

In ethnomusicological research, children are often conceptualised as the next generation of culture bearers who must be entrusted with valuable cultural materials to be sustained into the future. This conception, whether from cultural insiders, invested outsiders, or those in-between, often positions childhood as a place for re-embedding so-called ‘endangered musical traditions’. Understanding children as the next generation of culture bearers informs the ways we approach the research process surrounding the documentation, archiving, and repatriation of musical cultures.

Although archival practices and collections may sometimes seem somewhat irrelevant when presented to children, it is important to consider issues that impact children in terms of repatriation of musical materials. Through collaborative research with children and young people, we can examine best archival practices and the ethics and values of the repatriation of collections that may hold meaning for children and young people. This paper will explore some of the issues that surround exhibiting and repatriating materials from John Blacking’s historic research with children and young people in Venda communities from 1956 to 1958. Significant shifts in methodological approaches to research with children have framed how the repatriation of Blacking’s work highlights issues particular to working with children and young people.

Figure 7.1 Young boys using video cameras to film each other making music videos, Tshakhuma village, Limpopo, South Africa, 2012.

Research with children and young people

There have been few comprehensive ethnomusicological studies of children’s musical cultures and perhaps even fewer discussions of the vested and active interest children have in the sustainment and perpetuation of their musical traditions (see Emberly 2004, 2009, 2013; Minks 2002; Wiggins and Campbell 2013 for some examples). Moreover, a movement to engage children in the research process raises issues of intellectual property, informed consent, accessibility and ownership. In addition, given the 1989 UNCRC (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child) definition of a child as anyone under the age of 18, most Institutional Human Ethics Review boards mandate that any research with children is considered high risk – making it challenging for researchers to obtain ethical clearance for research that engages children directly in the research process. Therefore, conducting ethnomusicological research with children and young people requires a delicate balance that considers the unique ethical issues of working with children and the need for further research with children rather than research on and about children and young people.

At present, researchers who work with children are faced with complex ethical issues to consider, including: questions of consent from children; children’s ability to understand the long-term ramifications of documenting music including video and audio recordings; issues of children being documented at significant (and perhaps vulnerable) events in their lives where music is central such as during initiation ceremonies; issues surrounding children driving the research decisions and conducting research with other children in terms of snowballing consent, particularly when the researcher is not present; and issues of positionality and cultural understandings of the adult–child dichotomy. These ethical considerations challenge researchers to consider children’s participation in the research process and how to shift away from tokenistic representations of children to informed, child-directed and child-initiated research participation, while balancing issues of consent, access and dissemination (see, for example, Alderson and Morrow 2011; Greig 2013).

With most children eager to engage in technology in terms of video recording, photography, music editing and audio recording, it has rarely been problematic to engage children in the physical practice of collecting and, to some extent, analysing materials. In South Africa in particular, over the course of my own research with Venda communities in the last ten years, children have become engaged in my research and in the process of ‘doing’ the research themselves. When children are asked to document and analyse the role of music in their own lives, they become an integral part of the research process – as filmmakers, collaborators, and investigators. As such, it is important to understand how documenting, archiving, and in this instance repatriating, sits within this movement of engaging children and young people in the research process. This raises significant questions in terms of ethics, methodologies and long-term goals that will be discussed through a case study of the John Blacking archival materials.

John Blacking and Venda materials

From 1956 to 1958, anthropologist John Blacking conducted ethnographic research with Venda communities in Limpopo, South Africa. His archival collection and publications from this research period are comprised of audio and video recordings, photographs, song transcriptions and analysis, and detailed field notes (see, for example, Blacking 1964, 1967, 1973, 1980, 1988). Blacking focused on Venda children’s songs and on girls’ initiation ceremonies in particular, including the great Domba – a year-long ceremony that is the final stage for young women before marriage (Blacking 1969, 1980). After teaching for several years at the University of the Witwatersrand, Blacking left South Africa in 1969 and took a post at Queen’s University, Belfast, where he stayed until his death in 1990.

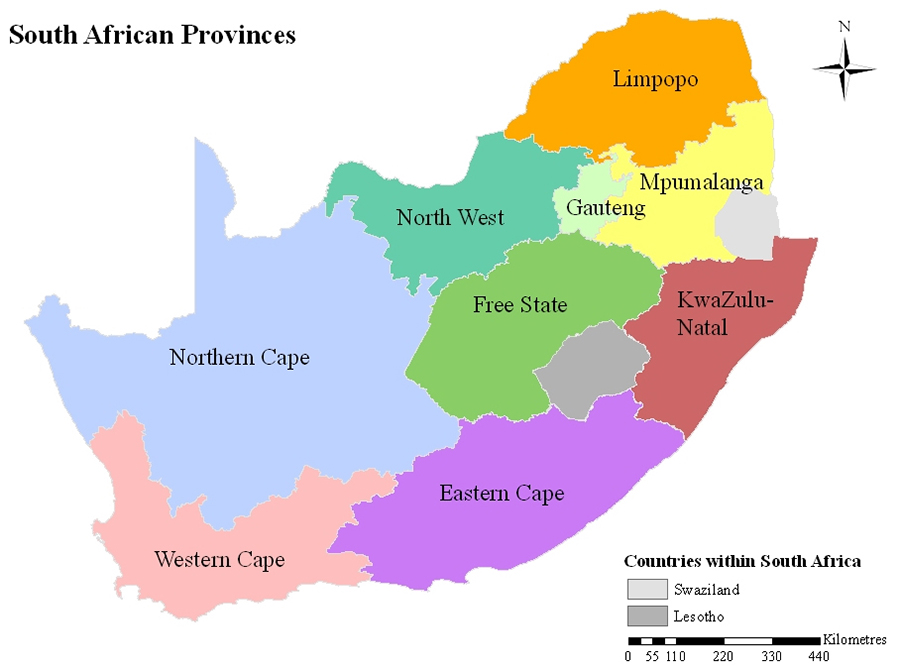

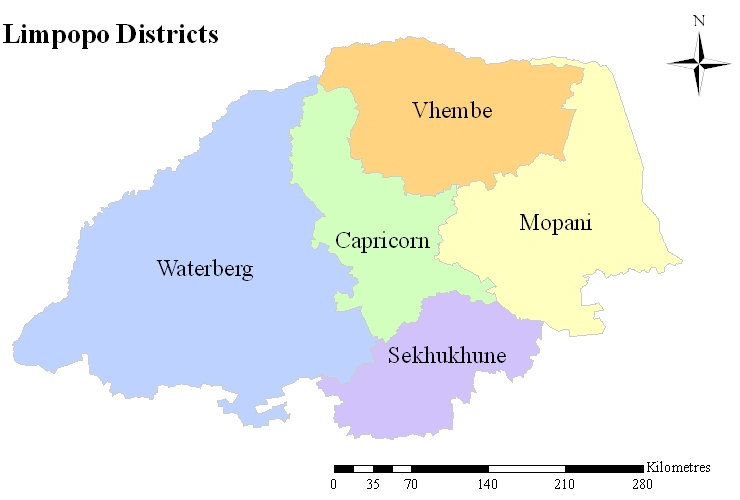

Figure 7.2 Map of South African provinces.

Figure 7.3 Map of Limpopo districts. Blacking conducted his research with Venda communities in what is now Limpopo province and the Vhembe district.

After Blacking’s death his widow, Zureena Desai, donated selected materials from his home office to the Callaway Centre at the University of Western Australia (UWA). The materials remained untouched until a limited selection of materials was digitised in 2003. In 2007 the remaining 16 boxes were officially unpacked, processed and shelved in the Callaway Centre (see also Post, this volume). The collection is comprised of print, sound and image with a mix of ethnographic materials from across the African continent and beyond, including limited recordings from personal and work travel. This collection raises issues surrounding archival recordings as outlined by Lobley and Jirotka (2011) who note that ‘archival sounds have often travelled far from the areas where they originate, retaining no ongoing connection with their source community’. This is the case with the materials in the Callaway Centre, which have travelled far from Limpopo and have held no connection with their source community. This provokes the question, ‘What purpose do archives serve?’ (Seeger and Chaudhuri 2004; Lobley and Jirotka 2011).

What purpose does the Blacking Collection held at the Callaway Centre serve and how might we consider issues of connection to source community that might further enrich the collection and contribute to its ongoing relevance? Questions posed by Nannyonga and Weintraub (2012, 224) in their Music of Uganda Repatriation Project are extremely relevant in this context, for example: ‘Where is knowledge located? Where can music of the past be experienced? Whose interests are served by repatriation?’ These questions are central to examining issues surrounding childhood and the repatriation of the Blacking Collection. Although it is apparent that there is no single answer to these questions, there are a number of possibilities to consider in relation to this rich collection. These considerations will be discussed below with regard to collaboration with Venda communities and connection between historical representations of children in the Blacking Collection and contemporary cultures of Venda childhood.

In addition to the Blacking Collection housed at the Callaway Centre Archives, a second collection of Blacking’s materials, comprised of the contents of his work office, is housed at Queen’s University, Belfast. Although there has been limited discussion between the two institutions who house the collections, there has been no significant analysis of the contents of both collections, although crossover and duplication between the two is apparent as well as incongruities. What is relevant for this discussion is that neither collection is available for general access and there has been little or no access to materials by the communities of origin. Although a review of Blacking’s film Domba notes that the film was reviewed in Thohoyandou in 2000 (Farigon 2002), beyond this undocumented viewing there has been no significant access to Blacking’s original materials by Venda communities.

Blacking and the Callaway Centre, UWA

Since 2009, a team of researchers at UWA has been exploring issues surrounding international collaboration, ethnomusicological archiving practices and frameworks for repatriating selections of the Blacking materials, particularly with regard to the Venda materials (Treloyn and Emberly 2013). One of the outcomes of this collaboration was the curation of a Blacking exhibition – Music, Dance, Landscape, Image – which was exhibited at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery at UWA in 2013 and included images, sound and video from the Blacking Collection from across the African continent, coupled with Venda instruments and objects from my own research. The next step of this process is an exhibition in Venda communities in Limpopo, where an expanded exhibition will focus solely on Venda materials and will be on display at the University of Venda from July 2014. The exhibition at the University of Venda will be on display in the University Art Gallery which is located in Thohoyandou, a large town in the Vhembe district1 and an area that connects several of the primary areas where Blacking worked. Through collaboration with the University of Venda Library, Thohoyandou was chosen as a location that was relevant to communities and a place that has central community access. In this way the university functions as a connection between archival materials and community, much in the vein of Du Bois’s famous quote:

The function of the university is not simply to teach bread-winning, or to furnish teachers for the public schools or to be a centre of polite society; it is, above all, to be the organ of that fine adjustment between real life and the growing knowledge of life. (Du Bois 1903, 61)

An additional reason for basing the exhibition at the University of Venda is the late Professor Victor Ralushai (professor emeritus at the University of Venda School of Human and Social Sciences and former vice-chancellor), who was Blacking’s primary research assistant and colleague. Ralushai received his PhD in social anthropology from Queen’s University, Belfast, under the direction of Blacking, and his ongoing work with Blacking is evidenced throughout the collection. Blacking also referenced his work with Ralushai throughout his publications, in particular Ralushai’s work for Blacking’s book Venda Children’s Songs. Therefore, the University of Venda is both a location that is historically relevant and accessible to Venda communities, and an institution that supports the connection between community and materials.2

Representations of Venda childhoods

Although limited materials from the Blacking Collection at UWA will be on display in Venda communities (primarily photos, coupled with some sound and video), the curation process is complicated given the subject focus of Blacking’s work – children – and a dramatic shift in the ways in which researchers approach research with children and young people today. It is widely recognised at present that research with children and young people must acknowledge children’s rights, including the right to participate in research and the right to an informed approach that includes archiving documented materials (see, for example, Christensen 2004; Lundy and McEvoy 2011). These rights also include the right to ‘have a say about things that concern them’ (Thomson 2008, 1), which, in the case of repatriating materials surrounding children and childhood, could mean both the rights of those children and young people documented in the materials and the rights of access of children and young people in contemporary Venda communities. As Christensen argues:

The recognition of children’s social agency and active participation in research has significantly changed children’s position within human and social sciences and led to a weakening of taken-for-granted assumptions found in more conventional approaches to child research. In order to hear the voices of children in the representation of their own lives it is important to employ research practices such as reflexivity and dialogue. These enable researchers to enter into children’s cultures of communication. (Christensen 2004, 165)

Theoretical and methodological changes in research impact the way we view Blacking’s materials, but they also impact the ways in which we conceive of and unfold repatriation processes. While this exhibition is a first step in sharing materials from the Blacking Collection with communities of origin, we recognise that access is limited. The University of Venda is a gated institution (as are all institutions in South Africa), meaning that in order to view the collection a person must have a reason to enter the campus and pass through security. As Seeger (2005) points out, the history of the institution may continue to limit access for communities. In addition, the university campus is not typically a place for children and young people, which further limits the benefits of materials focused on children and youth. However, hosting materials from the collection at the University of Venda offers benefits that outweigh issues of limited access, including a safe and secure point of access for community members, as well as access for a large number of young scholars.

The issue of community access to materials is complex and, as Lobley outlines, even materials held at the International Library of African Music in Grahamstown, South Africa, have ‘failed to reach local communities’ (Lobley 2012, 182) for many reasons including lack of information about the existence of collections, limited accessibility, and issues of ownership. Access is further complicated by a division of knowledge and access due to the legacy of apartheid. Seeger poses the questions: ‘What are the roles of archives in countries that have suffered the kinds of conflict and division created by Apartheid in South Africa? What does it mean for people who could not even enter the door of archives under previous regimes to be able to walk in, read the documents and listen to the voices of both their oppressors and their own people?’ (Seeger 2004, 95). Although the Blacking materials have not been deposited in an archive accessible to most people, the materials and the legacy of those materials evoke similar questions raised by Lobley and Seeger. Further complicating access to materials is the role of outsiders – in this case, an ethnomusicologist working as a cultural broker ‘between the archive and the relevant heritage community’ (Landau and Farigon 2012, 136). In addition to connecting and collaborating with adults, this brokering is unique when working with children and young people as it adds another layer between adults and children. The materials in the Blacking Collection represent Venda childhood in a specific time and place, in the lives of specific people and in specific Venda communities. As such, repatriating childhood is a means both to share records of historical childhoods and to present materials for children and young people today interested in the sustainment of Venda musical arts.

Although many scholars have discussed frameworks and issues surrounding repatriation and the complexities of these processes (see, for example, Lancefield’s discussion of the ‘changing conceptions of archives’ social roles, responsibilities, and opportunities’ (Lancefield 1998, 47)), there has been limited discussion focused on materials collected from children and young people. Although many of the issues that arise in this case study can be applied to repatriation of materials in general, discussion around consent and dissemination with regards to the Blacking Collection is particularly relevant due to the focus on children and young people.

As one of the most significant and comprehensive ethnomusicological collections of children’s music, Blacking’s recordings and scholarly writings tell us more than what we see on the screen and what we read on the page; they represent the quintessential way in which anthropologists and ethnomusicologists have treated the musical culture of childhood – not just in South Africa, but in an international context (Emberly 2004; Minks 2002). Visually and intellectually, Blacking’s recordings and writings offer insight into the dynamic and power-based relationship between researchers and children. The researcher, posed in a dominant position with a camera pointed at children, highlights the methodologies that adults have relied on in studying childhood.

When examining and contextualising the Blacking materials, it is important to centralise one of the questions that frame shifting research methodologies in the growing field of childhood studies: ‘What is an adult?’ (Christensen 2004, 166). That is, what kind of adult is the researcher within the community? When we explore this question with regard to Blacking, we must acknowledge his position within the community at the time. Understanding his role underscores his positionality, which may have affected the collection of materials, and thus their meaning for children and young people today. Therefore, does his position impact the meaning of his materials for those represented in the collection? Furthermore, understanding Blacking’s role and his methodologies for collecting research data from child participants leads to greater understanding of the materials produced and their usability for current communities. It is clear from Blacking’s materials, his fieldnotes, and through recent discussions with community members that there was some disconnect between adult and child, between researcher and participant. For example, community members who were present at the time have noted that some of the dances recorded and documented were ‘practice’ dances, that is, because they were recorded during the daytime they are not actual representations of the ‘real’ dance that Blacking was aiming to record.

As our documentation methods shift, so does the relationship between researcher and participant. Working with children and young people requires additional ethical and methodological considerations. University human-subject review boards require additional documentation for conducting research with children, which, as mentioned previously, is always considered high risk regardless of research subject or methodologies. As Claudia Mitchell outlines in her chapter aptly titled ‘On a pedagogy of ethics in visual research: who’s in the picture?’:

The legal and moral components, protection and awareness of the vulnerability of children and young people, and new issues in dissemination as a result of social networking sites has made this area of ethics one that often seems like a minefield. And although ‘doing least harm’ and ‘doing most good’ must surely remain as the cornerstones of our work as researchers, these clearly are interpretive areas in and of themselves. (Mitchell 2011, 15)

Furthermore, while some researchers have attempted to conduct research with children by assuming the ‘least adult role’3 (see, for example, Holmes 1998; Mayall 2000), it is an approach that fails to recognise or to problematise the social and cultural categories of adult and child (Christensen 2004, 166). While adults conducting research with children cannot participate as full insiders, methodological approaches may seek to lessen the divide between adult and child. However, these approaches have been viewed as problematic given the immense power differential between adult and child.

The context of Blacking’s historical work, coupled with our current collaborations, creates tension around issues of engagement and children’s positionality in the research process. If the children and young people in Blacking’s collection failed to have agency, voice and rights to informed participation, how does that impact the process of sharing materials from the collection? In addition, how can we move forward with collaborations that engage children and young people in the process and that do not repeat historical processes of disenfranchising children and young people? These questions underscore our current exhibition process and will continue to shape the approach of repatriating or sharing materials collected from children and young people.

While this discussion is not intended to criticise Blacking’s methodologies, which have roots in the colonial history of our discipline, it does highlight the vast shift in approaches to ethnomusicological research with a focus on children and young people. Differences between approaches in Blacking’s time and the present offer insight into the changes in research with children and young people and potentials for creating lasting legacies of children’s musical cultures with long-term community impact. While this is the ultimate goal for connecting communities to archival materials, the pitfalls that accompany this process are not overlooked. Researchers are urgently pushing for changes in approaches to working with children and young people;4 however, the processes themselves are complex in university settings given the tendencies of human ethics review boards to fall on the side of child protection over child engagement. For this reason ‘children themselves continue to find their voices silenced, suppressed, or ignored ... and even if they are consulted, their ideas may be dismissed’ (James 2007, 261).

Repatriating Venda childhood

The children and young people recorded by Blacking have had no access to the materials collected – none of Blacking’s books, films, or written materials have been made widely available in the primary communities in which he worked. In personal discussions with community members there has been repeated reference to the lack of access to any materials from Blacking’s historic work, although some people are aware of its existence. Because limited photographic and recorded materials exist from this time period, there is vested interest in the personal representations of childhood that are located in the collection (i.e., people may have no photos of living or deceased relatives who were recorded as children at the time). As such, sharing and collaborating around access to these materials provides access for those individuals represented and to the wider community, while facilitating historical documentation in communities of origin.

Perhaps most significantly, like all research at the time, written consent was not obtained for participation in Blacking’s research. Concerns about the repatriation process include obtaining community consent, because individual consent for a collection of this size and age is impossible, given that most of the participants are now elderly, unidentifiable or deceased. However, recognising that materials on display may need to be adjusted due to changing concerns about consent is vital. Some of the materials contain sensitive recordings, photos and/or video and, before public display of these materials, a review by appropriate members of communities must consider the impact of dissemination. Repatriation of materials from the Blacking Collection may address some of these issues by providing access to the relevant materials for discussion and perhaps dissemination, dependent upon community decisions regarding materials.

If researchers have re-evaluated how to approach the study of childhood and youth, then the outcomes of this examination must be applied and considered in relation to repatriation and archival questions that concern materials collected from and by children and young people. One question for the Blacking materials is how to find creative ways to identify children and their families in recordings and photographs. One of the primary goals that has been identified by community members is access to historical photographs of individual people, given the general lack of photos from this period. For the larger prints on exhibition, decisions for display are based primarily on aesthetic choices to complement the theme of Blacking’s collection of music, dance and community. In addition to the exhibition materials, large volumes of photos from the Blacking Collection will be shared throughout Venda communities as a means of generating further access to the collection. The volumes include over 1000 laminated images, primarily of children and young people, which people can write on directly (with erasable markers) in an attempt to gather information about photos in order to connect with the children (and perhaps their extended families) represented in the photographs.

These broad themes provide access points to the collection and will hopefully spark further interest in collaborating to provide access to all relevant materials for communities of origin. Because the focus of Blacking’s work is children and youth, collaborating with Venda young people is central to considerations of repatriation given the current state of Venda music today, in which many genres of musical traditions are still strong.

Conclusion

What researchers working with children today ask is: can there actually be an anthropology of childhood? (Hardman 1973; Hirschfeld 2002) How do the limitations, methodologies and distinctive features of childhood distinguish themselves from adulthood and what impact does this have on the research process and in turn on the documentation and archival processes? (Lancy 2008; Mead and Wolfenstein 1955; Montgomery 2009) As scholars such as Vallier and Sekula note, ‘archives are far from neutral’, and protocols for documenting and creating metadata for research with children are less developed (Mitchell 2011, 118). Some questions that researchers might ask include: how can we anticipate what children will feel in the future with regard to documented representations of their lives, and how can we create non-static archival processes that might adapt mechanisms for coding, sharing and retrieving materials that underscore the complex process of documentation? (Mitchell 2011, 118‒9) One question that is central to work in rural Venda communities is: what is the community desire to engage in this type of work given the limited access to technology, which is likely to be the source of both historical and current materials? (Mitchell 2011, 132). How might we explore potentials of community-based archives that work across collections, from Blacking’s to present-day collections created by Venda young people, to build relevant access that meets the desires of different communities of people?

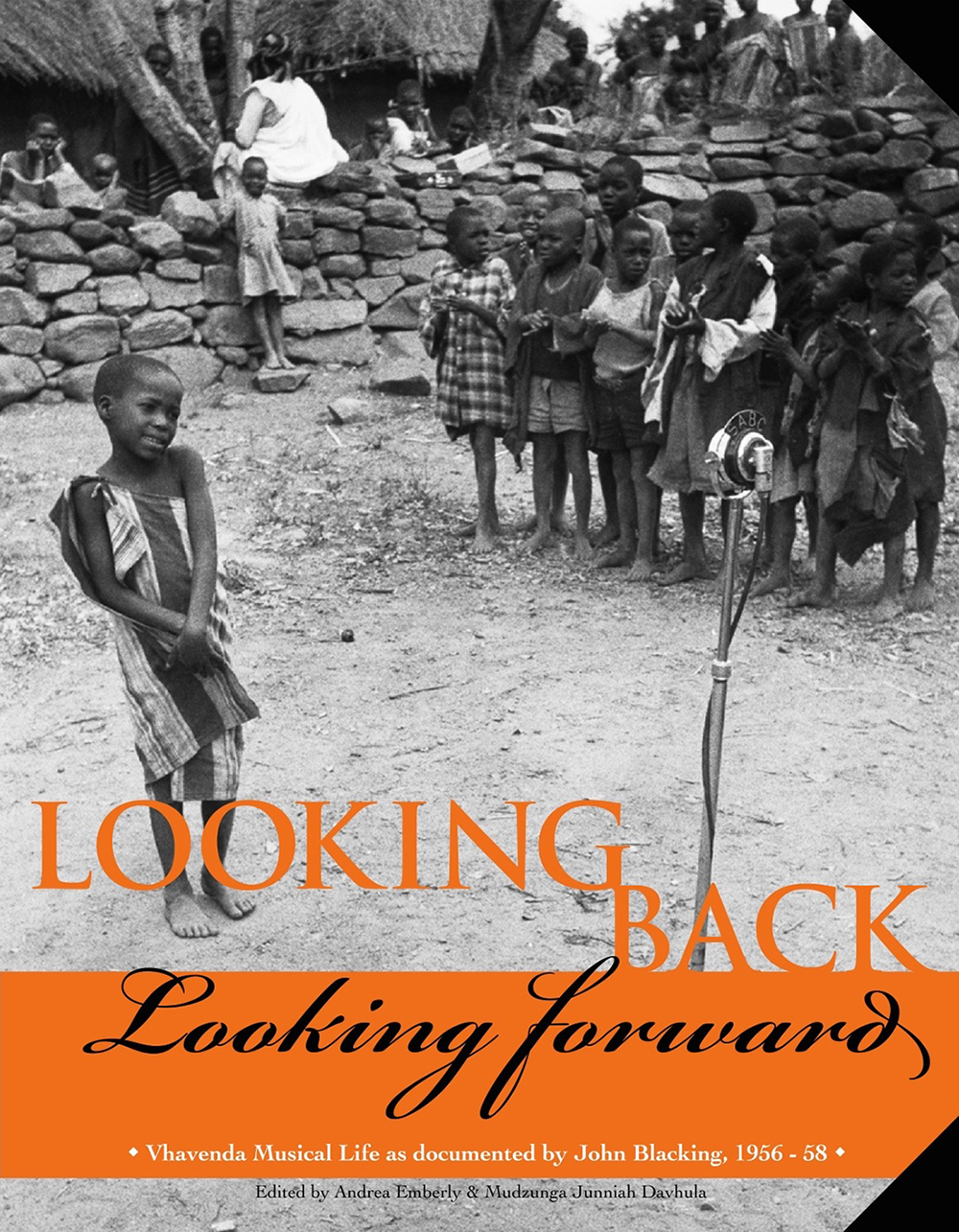

Figure 7.4 Blacking exhibition catalogue, 2014.

Figure 7.5 Example of a photograph from the Blacking Collection at the Callaway Centre, UWA. A young girl and a baby in a Venda community, names and place unknown. Photo by John Blacking.

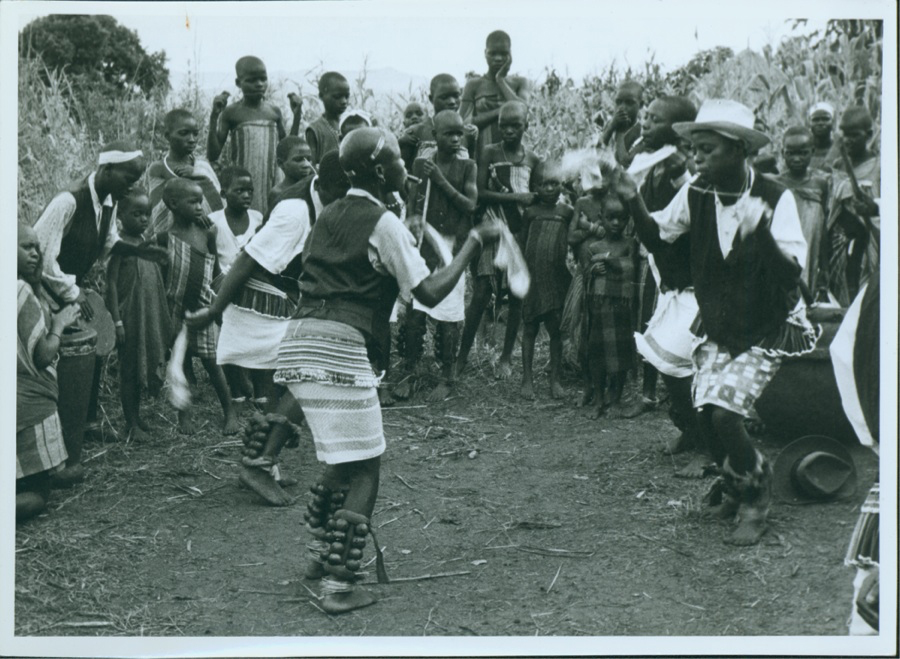

Figure 7.6 Venda girls dancing tshigombela. Photo by John Blacking from the Blacking Collection, Callaway Centre, UWA.

Figure 7.7 Venda girls dancing tshigombela, Arts and Culture Championship Competition, Maunavhathu Military Base, Limpopo, South Africa, 2009.

There is a growing movement among activists and academics to encourage children to ‘become active partners and participants in research conducted about them and among them’ (Montgomery 2009, 47). By recognising that the culture of childhood can be examined from a unique viewpoint that engages children in the research process, the methodological and theoretical foci of research can benefit children, their local communities, researchers, the international academic community at large and beyond. Engaging in research poses several important questions such as: what is our relationship as ethnomusicologists with community collaborators in terms of audiovisual representation, and can media be used for purposes such as social intervention? What are the collaborative and reflexive processes that can be used in the production of ethnographic knowledge? What are the ethics of research and documentation in terms of access, ownership and responsibility? In regards to children, these questions become even more significant as children stand to benefit both in terms of immediate skill building and through future engagement with a collection that documents their musical lives and upbringings.

By providing children with tools to represent their own musical lives, the goal, in fields such as childhood studies, is to present a more holistic view of children’s musical worlds and to move away from the historical ‘othering’ of children and their musical communities. As such, access to the Blacking materials provides historical representations of endangered musical cultures; provides representations of children’s lives in time and place; provides access to physical documents that are representative of the lives of individuals (who may or may not still be alive, whose families might recognise them, and who may have ideas about public access); provides the opportunity to explore how repatriating materials focused on childhood might have unique impact within Venda communities in terms of education and ‘knowledge production’ (Vallier 2010, 39); and can provide, as Lancefield suggests, ‘help for people to extend their sonic knowledge back to the time of their great-grandparents or before’ (Lancefield 1998, 59) or, in the case of the Venda, back to their own histories and those of their parents and grandparents.

At present, many Venda children’s songs, such as those documented by Blacking, are in danger of being lost due to shifts in educational frameworks and shifts in children’s responsibilities within communities. However, many genres have remained strong since Blacking’s time and thus a dichotomy is represented in the Blacking Collection: both the sustainability of musical traditions and a ‘quieting’5 of them (Emberly and Davidson 2011; Emberly and Davhula in prep). Therefore, the Blacking Collection has additional positive value for children and young people, who are at the centre of community action to revive and sustain children’s musical traditions. Additionally, contemporary research on Venda children’s musical cultures may provide, similarly to Nannyonga and Weintraub’s work on sound repatriation in Uganda, ‘cultural critique about the work of ethnographic representation’ (Nannyonga and Weintraub 2012, 221). And in the case of the Blacking Collection, this critique may centre on the ethnographic representations of children and childhood, thus supporting the notion that repatriation extends far beyond the ‘mere return of objects to communities’ (Nannyonga and Weintraub 2012, 225). Involving children and young people in the processes of repatriation and collaboration aims to, as Vallier states, ‘cradle collections to make them more meaningful, relevant, and resilient’ (Vallier 2010, 39).

Figure 7.8 A young girl recording dancers in Tshakhuma, Limpopo, South Africa, 2012.

Postscript

The exhibition discussed in this article was opened at the University of Venda on July 15, 2014. The exhibition was titled Looking Back, Looking Forward: Vhavenda Musical Life as Documented by John Blacking 1956–1958 and a catalogue was published by the International Library of African Music (ILAM). The exhibition was opened by the king of Venda with support from local chiefs, the chancellor of the University of Venda, and hundreds of local community members, including several women who were participants in John Blacking’s original research. In addition, Professor Ralushai’s widow and family members welcomed the collection, as did two of Blacking’s children. Further discussions of this exhibition, outcomes, and the ongoing collaboration are forthcoming.

Works cited

Alderson, Priscillia and Virginia Morrow (2011). The Ethics of Research with Children and Young People. London: SAGE.

Blacking, John (1964). Black Background: The Childhood of a South African Girl. New York: Abelard-Schuman.

Blacking, John (1967). Venda Children’s Songs. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Blacking, John (1969). ‘Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls’ initiation schools. Part 1: Vhusha.’ African Studies 28(1): 3–36. doi: 10.1080/00020186908707300.

Blacking, John (1969). ‘Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls’ initiation schools. Part 2: Milayo.’ African Studies 28(2): 69–118. doi: 10.1080/00020186908707306.

Blacking, John (1969). ‘Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls’ initiation schools. Part 3: Domba.’ African Studies 28(3): 149–99. doi: 10.1080/00020186908707309.

Blacking, John (1969). ‘Songs, dances, mimes and symbolism of Venda girls’ initiation schools. Part 4: The great Domba song.’ African Studies 28(4): 215–66. doi: 10.1080/00020186908707313.

Blacking, John (1973). How Musical Is Man? Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Blacking, John (1988). ‘Dance and music in Venda children’s cognitive development.’ In Acquiring Culture: Cross Cultural Studies in Child Development, edited by Gustav Jahoda and Iaon M. Lewis, 91–112. London: Croom Helm.

Blacking, John, John Baily and Andrée Grau (1980). Domba, 1956–1958: A Personal Record of Venda Initiation Rites, Songs and Dances. Bloomington: Society for Ethnomusicology, 2001, VHS tape and study guide.

Christensen, Pia Haudrup (2004). ‘Children’s participation in ethnographic research: Issues of power and representation.’ Children and Society 18: 165–76.

Du Bois, W.E. Burghardt (1903). The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co.

Emberly, Andrea (2004). ‘Exploring children’s Musical culture in ethnomusicology.’ Paper presented at the UNESCO Regional Meeting on Arts Education in the European Countries, Canada and the United States of America. Finland.

Emberly, Andrea (2009). ‘Mandela went to China … and India too: Musical cultures of childhood in South Africa.’ PhD thesis, University of Washington, Seattle.

Emberly, Andrea (2013). ‘Venda children’s musical cultures in Limpopo, South Africa.’ In The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Musical Cultures, edited by Trevor Wiggins and Patricia Campbell, 77–95. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emberly, Andrea and Jane Davidson (2011). ‘From the kraal to the classroom: Shifting musical arts practices from the community to the school with special reference to learning tshigombela in Limpopo, South Africa.’ International Journal of Music Education 29(3): 265–81.

Emberly, Andrea and Mudzunga Junniah Davhula (2015). ‘Learning to be musical in Limpopo: Venda children’s musical cultures.’ (unpublished manuscript).

Greig, Anne (2013). Doing Research with Children: A Practical Guide, 3rd edition. London: SAGE.

Hardman, Charlotte (1973). ‘Can there be an anthropology of children?’ Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 4(2): 85–99. Reprinted in 2002, Childhood 8(4): 501–17.

Hirschfeld, Lawrence A. (2002). ‘Why don’t anthropologists like children?’ American Anthropologist 104(2): 611–27.

Holmes, Robyn M. (1998). Fieldwork with Children. London: SAGE.

James, Allison (2007). ‘Giving voice to children’s voices: Practices and problems, pitfalls and potentials.’ American Anthropologist 109(2): 261–72.

Lancefield, Robert (1998). ‘Musical traces’ retraceable paths: The repatriation of recorded sound.’ Journal of Folklore Research 35: 47–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3814785.

Lancy, David F. (2008). The Anthropology of Childhood: Cherubs, Chattel, Changelings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Landau, Carolyn, and Janet Topp Fargion (2012). ‘We’re all archivists now: Towards a more equitable ethnomusicology.’ Ethnomusicology Forum 21(2): 125–40.

Lobley, Noel (2012). ‘Taking Xhosa music out of the fridge and into the townships.’ Ethnomusicology Forum 21(2): 181–95.

Lobley, Noel and Marina Jirotka (2011). ‘Innovations in sound archiving: Field recordings, audiences and digital inclusion.’ Paper presented at Digital Engagement Conference, Newcastle, UK, 15–17 November. http://tiny.cc/2011-lobleyjirotka.

Lundy, Laura and Lesley McEvoy (2011). ‘Children’s rights and research processes: Assisting children to (in)formed views.’ Childhood 19(1): 129–44.

Mayall, Berry (2000). ‘Conversations with children: Working with generational issues.’ In Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices, edited by Pia Monrad Christensen and Allison James. London: Falmer Press.

Mead, Margaret and Martha Wolfenstein, eds. (1955). Childhood in Contemporary Cultures. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, Claudia (2011). Doing Visual Research. London: SAGE.

Minks, Amanda (2002). ‘From children’s song to expressive practices: Old and new directions in the ethnomusicological study of children.’ Ethnomusicology 46(3): 379–408.

Montgomery, Heather and Mary Kellett (2009). Children and Young People’s Worlds: Developing Frameworks for Integrated Practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Nannyonga, Sylvia and Andrew Weintraub (2012). ‘The audible future: Reimagining the role of sound archives and sound repatriation in Uganda.’ Ethnomusicology 56(2): 206–33.

Seeger, Anthony (2004). ‘New technology requires new collaborations: Changing ourselves to better shape the future.’ Musicology Australia 27(1): 94–110.

Seeger, Anthony (2005). ‘Who got left out of the property grab again: Oral traditions, Indigenous rights, and valuable old knowledge.’ In CODE: Collaborative Ownership and the Digital Economy, edited by Rishab Aiyer Ghosh, 75–84. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Seeger, Anthony and Shubha Chaudhuri (2004). Archives for the Future: Global Perspectives on Audiovisual Archives in the 21st Century. India: Seagull Books.

Thomson, Pat (2008). Doing Visual Research with Children and Young People. London: Routledge.

Topp Fargion, Janet (2002). Review of Domba 1956–1958. A Personal Record of Venda Initiation Rites, Songs and Dances by John Blacking; John Baily and Andrée Grau. British Journal of Ethnomusicology 11(2): 149–50.

Treloyn, Sally and Andrea Emberly (2013). ‘Sustaining traditions, collections, access and sustainability in Australia.’ Musicology Australia 35(2): 1–19.

Vallier, John (2010). ‘Sound archiving close to home: Why community partnerships matter.’ Notes 67: 39–49.

Wiggins, Trevor and Patricia Campbell, eds. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Musical Cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1 Thohoyandou was the former capital of the Bantustan of Venda.

2 It is recognised that the University of Venda does have access limitations, which are discussed later in this chapter.

3 The ‘least adult role’ often means researchers attempt to enter the culture of childhood by attempting to disregard their adult role. Blacking himself notes that he often tried to learn music ‘like a child’ and would purposely sing songs incorrectly to children to see when and how they corrected him. At present it is a widely disregarded practice in the field of childhood studies because it is clear that, while we may try to act un-adult-like, there is no way to shed the role of adult in most contexts.

4 The movement to change the approaches to research with children and young people is being led by the field of children’s and childhood studies, which began primarily in the UK and is currently gaining ground in North America. This field uses ethnographic, qualitative and child-centered approaches to research with children, with a focus on research engagement with children and young people.

5 A term used in TshiVenda, where the loss of musical tradition is simply referred to as a quieting of certain songs.