8

Repatriation and innovation in and out of the field: the impact of legacy recordings on endangered dance-song traditions and ethnomusicological research

Repatriation and innovation in and out of the field

In 1974 anthropologist Hilton Deakin reported an early example of innovation in the media and modes by which songs were transmitted from person to person in the Kimberley. He described the arrival of a trade package containing a cassette tape of Balga song recordings in the northern Kimberley community of Kalumburu (Deakin 1978). While it is not now known what repertory or repertories of Balga (a genre of dance-song indigenous to Kimberley also known as Junba) this cassette carried, it is clear that the repertory/ies arrived in Kalumburu according to principles of Wurnan – the customary Law and ethos of sharing that underpins the distribution of resources and knowledges throughout the Kimberley. Cultural heritage stakeholders – such as the Wurnan bosses and songmen and women of Kalumburu at the time – established a path for their communities to use new song technologies to learn and teach songs, a pathway that researchers have only in relatively recent times followed. Over the last decade, ethnomusicologists have increasingly become preoccupied with the repatriation of records of songs and dances to communities of origin for a range of reasons that have been summarised elsewhere (see Treloyn and Emberly 2013; Treloyn, Charles and Nulgit 2013). In Australia, the return and dissemination of audio and video recordings from archival and personal collections to cultural heritage communities has emerged as a primary, and almost ubiquitous, fieldwork method.

Elsewhere, we have provided data that tentatively points towards increases in the quantity and diversity of unique Junba dance-songs and repertories that are performed at unelicited1 public festivals in the Mowanjum Aboriginal Community in the western Kimberley (see Treloyn, Charles and Nulgit 2013). We suggest that this stimulation of the tradition corresponds to community-led engagement with repatriation and dissemination of legacy records of Junba. In this paper, we provide additional data on the past and present state of the Junba tradition in order to provide further context for and to advance our previous findings. We consider the contexts and ways in which cultural heritage stakeholders across generations use archival and new materials to have an impact upon endangered song traditions, and also consider ways in which the returning materials and community-led dissemination of these materials may continue to influence and innovate fieldwork and research.

Junba legacies

Junba (also known as Balga, Jorrogorl and Jadmi) is one of Australia’s richest and oldest performance traditions. Indigenous to almost all of the 30 language groups of the Kimberley region, Junba has been a primary mode of intercultural, interfamily and interpersonal communication since the genre was created by Wanjina ancestors in the Lalarn or Lalai (‘Dreaming’, Ungarinyin and Worrorra languages respectively). Junba is a public dance-song genre that is performed during public gatherings, in which linguistically and culturally distinct groups come together, with clearly defined roles for insiders and visiting groups. Junba dance-songs and repertories are conceived in dreams by men and women, when an anguma, agula or juwarri spirit visits a living family member and takes her/him on a journey over the landscape and through history, showing and demonstrating dance-songs and important events. Repertories document and enact the land- and Law-forming actions of Wanjina spirits and other ancestral beings, such as the moiety-heroes Wodoi and Jungun, the travels and activities of various other spirits, and historical and living people. The subjects of repertories and songs are diverse, ranging from songs that celebrate connections between living dancers, deceased family, and ancestral spirits, to Wanjina spirits (see Figure 8.1), to everyday activities such as fishing trips, to historical events such as slavery associated with Captain Cook (see Redmond 2008), Cyclone Tracy in 1974, and the appearance of Spitfire aeroplanes in the sky during World War Two. Today, the practice of Junba on Country and at public cultural events has great significance for the communities that own and maintain these songs and dance traditions, affecting social and emotional wellbeing, and articulating identity in relation to place, family and history (see Treloyn and Martin 2014).

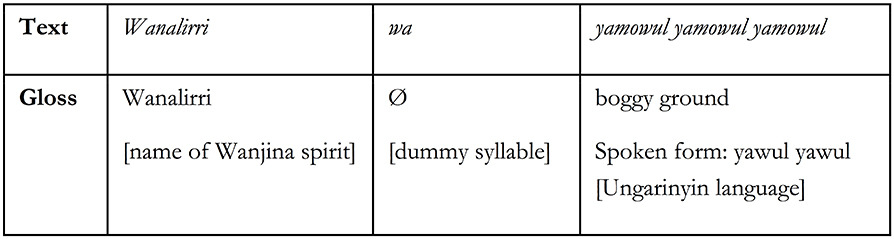

This chapter is concerned with the Junba repertories and practices of communities of people who identify as Ngarinyin (Wilinggin), Wunambal and Worrorra residing in the Mowanjum Community and other communities along the Gibb River Road, which runs through the Kimberley from west to northeast. Members of the three groups join together in maintaining Law ceremonies, and hold, perform and share Junba repertories according to Wurnan. Each Junba repertory comprises approximately 20 to 40 distinct songs. Each song has a unique text that is performed isorhythmically and repeated cyclically, breaking and recommencing at structural melodic points (see Treloyn 2003). The text of a typical Junba song, mixing Ungarinyin and Worrorra languages, is set out in Figure 8.1. The translation and morphological analysis is provided by linguist Thomas Saunders.

Figure 8.1 Wanalirri song from the Wanalirri Junba composed by Wati Ngerdu, circa 1960. Text transcription by Sally Treloyn with Pansy Nulgit. Analysis by Thomas Saunders.

Living memories of elder Ngarinyin, Wunambal and Worrorra residing in the town of Derby and the Community of Mowanjum in the western Kimberley, and further to the northeast in Imintji, Kupungarri and Dodnun Communities between 2000–02 and 2010–12 indicate a rich and prolific history of at least 35 Ngarinyin, Wunambal and Worrorra Junba composers through the 20th century, responsible for the composition of over 50 repertories of song. Of the 1500–2000 songs that would have made up these repertories at their peaks, over 500 unique songs have been recalled, performed and documented since 1997. Of these, fewer than 20 songs are regularly performed with dance today, attributed to the following composers:

- Sam Woolagoodya, whose Baler Shell corroboree is continued by his son Donny Woolagoodya;

- Wati Ngerdu, whose Wanalirri Junba repertory (see Figure 8.1) is performed at almost all major Ngarinyin cultural events; and

- Scotty Martin, whose Jadmi-type Junba repertory has recently been revived after a hiatus of several years following the passing of two of its prominent dancers.

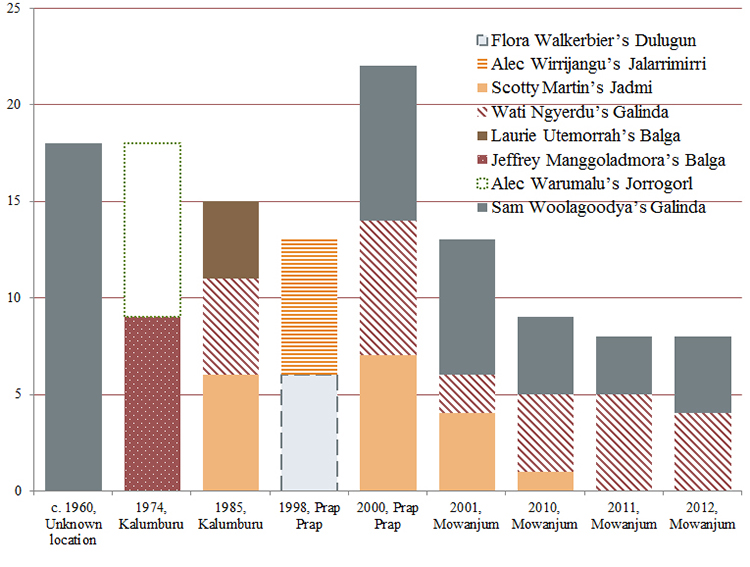

While many factors guide which of the songs and distinct repertories come to be performed at a public event, it is evident from available recordings of unelicited public performances recorded between circa 1960 and 2012 that the number of repertories and songs performed at these events has decreased substantially. Figure 8.2 presents data from nine recordings of unelicited danced performances made by:

- An unknown recordist in Mowanjum or Bangarun circa 1960 (tape held by elder Mabel King (dec.) in 2001);

- Lesley Reilly (recorded in Kalumburu 1974);

- Ray Keogh (recorded in Kalumburu 1985);

- Linda Barwick (recorded in Prap Prap 1998); and

- Sally Treloyn (recorded in Prap Prap 2000, and Mowanjum in 2001, 2010, 2011, 2012).

Figure 8.2 Number of unique songs by repertory performed at selected, unelicited, danced public events.

Figure 8.2 indicates some attrition of the number of songs in common usage for such events, from 13 to 22 in the period circa 1960–2001, to eight or nine in the period 2010–12. It also indicates a reduction in the variety of repertories that are being performed, with some eight composers represented in the period between 1960 and 2001, and only three in the period 2010–12 (although this is partly due to the single location of data in later years). While Junba remains strong, this indicates some degree of endangerment.2

Communities and leading elder songmen and women, including Scotty Martin, his son Matthew Martin and Pansy Nulgit, along with emerging elders such as one of the co-authors of this paper, Rona Googninda Charles, have sought to address this endangerment through their engagement with researchers such as Treloyn and the Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre. Underpinning the urgency and importance of this task is the role that Junba practices play, as noted, in maintaining and achieving the wellbeing of Country, spirits and living ancestors: the wellbeing of individuals and communities is tied to the wellbeing of song traditions (see Treloyn and Martin 2014). In this chapter, we will discuss the core activities of a project centred on fostering community-led discovery and repatriation of recordings from legacy collections, hand in hand with traditional teaching and learning on Country. We present the perspectives of cultural heritage stakeholders on these activities, and on associated research methods, through transcribed dialogues and conversations. First, we briefly outline legacies of research on Junba.

Legacies of Junba research, 1938–2002

Junba has been the focus of several research projects, dating back to the ethnographic expedition of the German Kulturmorphologisches Institut to the northwest Kimberley in 1938–39.3 While no recordings from the expedition are currently known to the authors, the leader, Andreas Lommel, transcribed lyrics and prepared glosses of some 43 Junba song texts with their Worrorra composer, Alan Balbangu, along with descriptive accounts of song conception experiences and dances. These were later published in the text Die unambal (Lommel 1952, trans. to English 1997), and further discussed by Lommel with Ngarinyin lawman David Mowaljarlai (Lommel and Mowaljarlai 1994) and then in 2001–02 by Treloyn with Ngarinyin elders who recalled Lommel’s 1938–39 visit (Treloyn 2006a). From the 1960s through the 1980s substantial collections of Junba were recorded in Derby, Mowanjum, Kalumburu, Kununurra and Wyndham by numerous people, including Alice Moyle, Peter Lucich, Wayne Masters, Ian Crawford, Lesley Reilly, Ray Keogh and Ambrose Cummins.

While Alice Moyle undertook a number of transcriptions of Junba songs, elicited song texts with performers and described the instrumentation and aspects of performance practice (1974, 1978, 1981), work to investigate the entire sample of Junba that Moyle recorded is only now being undertaken. Although substantial recordings of Junba were made in the 1960s–1980s, it was not until the mid to late 1990s that ethnomusicologists returned to Junba. Between 1997 and 1999, Allan Marett and Linda Barwick collaborated with anthropologist Anthony Redmond, the Ngarinyin Aboriginal Corporation based in Derby, community leaders and singers to record several repertories of Junba: the Jalarrimirri Junba composed by Alec Wirrijangu, the Dulugun Junba composed by Flora Walkerbier (dreamt by Bruce Nelji), Wati Ngerdu’s Wanalirri Junba, and Scotty Martin’s Jadmi and Jorrogorl Junba repertories. These recordings subsequently formed the starting point for Treloyn’s doctoral study of Junba. In 2000–2002, Treloyn worked with a group of elder men and women identifying as Ngarinyin, Worrorra and/or Wunambal to record and transcribe known Junba songs and research their histories and cultural significance (see Treloyn and Charles 2014). Treloyn (2006a) focused on analysis and ethnography of the Junba performance practice and composition, centred on the Jadmi-type Junba repertory composed by Scotty Martin.

Throughout Treloyn’s postgraduate fieldwork between 2000 and 2002, it was evident that elders of the community valued the legacy recordings produced by earlier research. As well as seeking to document their own knowledge of Junba, two elders brought to her cassette tapes copied from recordings made in the 1960s to discuss and, in one case, repair. The repaired tape included a substantial collection of songs composed by Laurie Utemorrah and Paddy Lalbanda, known as the Bayerra repertory. The renewed interest in the songs, promoted by dissemination of copies on cassette and CD, led elder Ngarinyin siblings Mabel King (dec.) and Jimmy Maline (dec.) to ‘wake up’ the Junba (i.e., to stage the Junba after a hiatus of some years). This tape, and several cassette copies of recordings made by Barwick and Marett, became like a soundtrack for fieldwork, almost constantly playing on the cassette player in Treloyn’s Toyota at the request of elder ladies with whom she travelled. This became a way for Treloyn to learn the songs and singing, at the encouragement of leaders such as Pansy Nulgit, and also stimulated sessions of documentation. In the course of Treloyn’s fieldwork, the texts and histories of the repertories contained in Barwick and Marett’s collection, as well as Ray Keogh’s collection, with the addition of the aforementioned tapes held by the elders, were documented by groups of elders led by Jack Dann (dec.), Paddy Neowarra, Scotty Martin, and Pansy Nulgit. After Treloyn’s return to Sydney, requests for access to additional copies of cassettes and CDs continued. Additionally, Scotty Martin – an important proponent of the continuation of the Junba tradition through his composition of two repertories, and his leading of Worrorra and Wunambal repertories at annual Mowanjum Festivals and other cultural events – requested that Treloyn return to the Kimberley to undertake activities to support increased youth engagement with Junba.

While Barwick and Marett returned copies of their research to the communities of origin as did Redmond and Treloyn, and elders held earlier selected copies of recordings made during 2000–02, longer-term, local access to the results of research remained inadequate. Moreover, it seemed that to support intergenerational engagement around Junba, research needed to move beyond the traditional model of recording, documenting, analysis and archiving, to include communities in these discovery, collection and preservation processes. Following consultations through 2008–09 a project – which became known locally as the Junba Project – was developed, supported initially by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) and later by the ARC, in partnership with the Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre (located in the Mowanjum Community close to Derby) and the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre (KALACC).4

The Junba Project

The primary aim of the Junba Project was to determine effective methods for repatriating, recording and documenting recordings of song and dance to support intergenerational knowledge transmission and production around Junba. The project was based on assumptions about the positive impact that recordings and other products of ethnomusicological research can have on endangered traditions and cultural heritage communities. There were numerous anecdotal accounts of the role that recordings could play in supporting creative innovation and the memory and recovery of songs (see, for example, Marett and Barwick 2003). Deakin’s observation of an audiocassette in a Wurnan package (Deakin 1978) suggested that new technologies may be readily incorporated alongside more traditional modes of teaching and learning Junba over the vast distances of the Wurnan system. And, as noted, Treloyn had observed and played a role in elders’ efforts to wake up a repertory, initially stimulated by the repair of a cassette tape in 2001. In doing so, however, Treloyn was also mindful of the potential harm that the recordings might have done due to the reifying and distorting potential of recording media (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 2006) on creative, fluid forms (Knopoff 2004, 181), as well as on the diverse knowledges that circulate around particular songs (Wild 1992, 13) (see Treloyn and Emberly 2013). As the project proceeded, we were interested to note how community leadership and use of repatriation and dissemination as strategies to sustain the Junba tradition mitigated against this potential adverse effect of repatriated recordings.

The primary materials that were repatriated to the community were selections of collections recorded by Treloyn between 2000 and 2002, by Barwick and Marett between 1997 and 1999, by Ray Keogh in 1985, and by Lesley Reilly in 1974. A core group of stakeholders also attended the AIATSIS Access Unit in November 2012 with Treloyn and Marett to discover, review and order copies of subsequent recordings and photographs by Alice Moyle, Peter Lucich and Ian Crawford, among others. These were received in 2014. Recordings and documentation repatriated or produced by the community and researchers in the course of the project were subsequently used by multiple generations to produce knowledge about Junba and contribute to intergenerational engagement with the tradition. We present here excerpts of dialogues and stories of repatriation, dissemination and use by cultural heritage stakeholders. The dialogues and stories are from two generations of stakeholders: Matthew Dembal Martin, a senior manambarra (lawman) and leader of Junba singing and dancing, and Rona Googninda Charles, co-author of this chapter and an emerging leader for Ngarinyin peoples and researcher of Junba. These stakeholders describe and critically assess the research process, consider benefits, and make recommendations for future research. We do not intend for these accounts to be exhaustive, but rather to set out a range of uses and reflections on the experience and use of repatriation, dissemination of recordings, as well as documentation activities, within the diverse community.

Recordings as a conduit to ancestors and place

In our presentation to the Research, Records and Responsibility (RRR) conference, Charles emphasised the personal significance of recovering records of her family in the collections. In doing so she also stressed the importance of there being a new repository – or ‘home’ – for digital records of these collections in a local archive located within her community (in this case the Wurnan Storylines community archive developed by Katie Breckon at the Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre):

We went to the archive, Canberra. And I was so amazed. I found lot of the old stuff: a lot of photographs of Junba, and also my old people that I grew up with and I knew. We were able to go and get copies and bring him back because our Art Centre [Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre] is establishing an archive. [Because of this] we [are] getting all the archive material from Canberra and maybe Western Australia to put them in our own system in the community. (Rona Googninda Charles, 2 December 2013, Research, Records and Responsibility, University of Melbourne)5

Elsewhere elder Matthew Martin has reflected on the presence of ancestors in recordings held in the AIATSIS archive. He stresses the importance of bringing copies of these recordings that provide a conduit to these ancestors back to the hereditary Country to which they belong:

[I]t was good [to] see those old, old things from old people, and the song. [We] pick the song from old, old people. They [the old people] are still there [in the recordings]: like the old people are gone but their spirit is still there. What you call that place? They still there, they still remain. Can’t forget them ... [We need to] bring the whole lot back ... bring them back to Country. (Matthew Dembal Martin, 16 January 2014, Mowanjum Community)6

Martin’s explanation of the need to bring records of ancestors’ songs and voices back to Country corresponds to the need to repatriate the physical remains of ancestors’ bodies back to Country. Historian Martin Thomas explains the subject status of human remains for elders from Arnhem Land who journeyed to the Smithsonian Institute to accompany the remains of deceased family back to Country: ‘[f]or Gumbula … death has not altered their subject status. And as was the case when they were living and breathing, they can still expect to connect with, and reside within, their ancestral country’ (Thomas 2014, 134). Like bones, recordings are not the objective relics of past research, but rather are subjective remains of ancestors with which living people have active responsibilities and relationships.

Recordings and teaching/learning

For Martin, the need to bring back recordings relates to his own responsibilities as a teacher of Junba to pass on Junba knowledge to the generations that follow him. The following dialogue between Treloyn and Martin illustrates the role played in teaching and learning by the recordings, and by the ancestors to whom the recordings provide a conduit:

Treloyn: So, [is there] anything you want to say about why it’s important to bring those old recordings back from Canberra, and how you have been using those old recordings for yourself, to teach kids?

Martin: Yeah, well the main thing is learning [teaching] kids – our next generation coming up – before they [the songs and dances] die away, you know ...

Treloyn: How do you teach the kids to dance with the old recordings?

Martin: Well, that’s the recording, you go by the words: the meaning, you know. The meaning of the songs and what it’s about: Country or ... the spirit, [or] birds. Just follow that ... Follow the spirit. [The] spirit [will] always be there.

Treloyn: And what does it mean ... if you have an old recording with old, old people singing in it and you can hear their voices?

Martin: It’s sort of bringing in to it, you know. Old old songs, old old people what been passed away, like you bringing the spirit back to you. So you, you can carry on ... [as] the teacher for them, for the next generation.

Treloyn: It’s like the spirits are helping you do the teaching.

Martin: Yeah, it’s like the old spirit comes back. You can’t see it but you can feel it ... Singing ... Dancing it brings memories back to, from the old time ... When young people dance, it brings back the memories of old people. They [the old people that have passed] are teaching them. Its just like they’re, they’re happy to dance and you see the young kids running around. They are willing to dance. The spirit comes back to them ... [unclear] spirit to their spirit you know ... It sort of draws them in. (Matthew Dembal Martin, 16 January 2014, Mowanjum Community)

Charles has similarly used recordings to support her own endeavours to teach and learn Junba (see Treloyn and Charles 2014).

Recordings as a conduit to wellbeing

Given that reference to and memories of deceased family members may induce feelings of sorrow for Indigenous peoples in the Kimberley, as elsewhere in Australia (to the extent that there is avoidance and often a prohibition on saying the name of the deceased), it is logical that we consider what impact playing and listening to recordings of the voices of ancestors in legacy recordings has on living, listening family members. In the following dialogue, Martin explains that while listening may bring feelings of sadness, the experience of receiving songs from the spirits of ancestors, via recordings, and then carrying these songs on into the future, brings good liyan or ‘gut feeling’ (Redmond 2001a), that encompasses personal wellbeing as well as that of the speaker’s community and broader world (Dodson, cited in Yu 2013).

Treloyn: When you hear an old old recording of old people, how does that make you feel?

Martin: Ah, it makes you a bit sad. But you know you [are] getting those old songs back, so ... you can have it here from the old people singing to your time [that is, singing from the past into the present] ... [You] feel sad for listening to their voice; the old people’s voice sort of makes you feel off. But when you start singing it [the song that they teach you] you feel the power coming into you. [It is] just like the old spirit [of your ancestor] comes into you. So you start singing, and you don’t miss a word. You pick songs up. You listen to it a couple of times maybe, and you pick it up ... You feel it in your body. Sad, next one you feel happy now. [You] start [to] sing that old old songs ... The spirit comes out and you [are] the boss man now. Just like the spirit been leave it up to you now. That anguma [spirit of deceased person], you know, anguma ...

Treloyn: When you [are] happy for singing a song that you have picked up and that spirit’s come and handed it over, do you feel that feeling of liyan?

Martin: ... That liyan make you feel happiness come to you more. [When you] start singing the song after the old people come to you, [it] make you feel proud. Proud. Make you carry on [from] the old people. (Matthew Dembal Martin, 16 January 2014, Mowanjum Community)

Liyan is dependent on relationships between individuals, their families and their Country (Dodson, cited in Yu 2013). Insofar as recordings are used as a conduit to past family and place, and Junba singing and dancing serve to reinforce connections to place (see Redmond 2001b), the importance of repatriation of recordings for stakeholders such as Martin is perhaps predicated on the contribution that recordings can make to a person’s and a community’s wellbeing.

The extent to which recordings may serve as a therapeutic tool is yet to be the subject of research. However, Charles recounts a compelling story of the beneficial effects of playing Junba recordings, arranged into an iTunes playlist prepared in the course of the Junba Project, to an elderly singer who had been recently admitted to residential aged care in the town of Derby, several hundred kilometres from her Community and immediate family.

Charles: There’s an old lady that was one of our main singers and she’s also a composer. She was put in an old nursing home and ... she had [been told she had] dementia. I went there one day, and I took her sister along. She [the old singer] was in bed. It was ten o’clock [in the morning] and one of the staff was saying to us, ‘Oh, we can’t get [her] out of bed, she refuse[s] to get out of the bed. She’s so depressed and we don’t know what to do with her. She’s just going to lay there.’ I took the laptop with me and I went in there and I sat down. She was just staying there covered up with the blanket. I put on the music; I put on one of the Junba songs for her. She was laying down listening, and I could see her lips moving. She got out of bed, sat down and started singing! I thought to myself, if she had dementia [as her carers had said], she wouldn’t remember any of these songs, but she was singing! And she started singing! And I put on the next one and she sang it. I got her to get up, to have a shower [and] make her bed up. And she ... came alive. The music made her come alive, you know ... (Rona Googninda Charles, 2 December 2013, Research, Records and Responsibility, University of Melbourne)

Noting that this elderly singer’s experience is not unique, Charles suggests that recordings of Junba might be used on a regular basis as a tool to improve the lives of the broader community of elderly people who move from their Communities throughout the Kimberley into towns for care.

Thinking about some of our old people at the nursing home in the town, when we [their families] live in the Communities, we thought, ‘We’ll take CDs there for them, and put them on while they are there, [and they can be] listening to the CDs all day, [or at] morning tea or lunch break. We found that it was very useful for us to take these CDs for the old people[’s] home [i.e., the residential aged care facility]. It amazes me because they [the staff] say they [the old people] can’t remember anything, but when you put on the Junba they start singing. (Rona Googninda Charles, 2 December 2013, Research, Records and Responsibility, University of Melbourne)

Waking up dance-songs and strengthening the tradition

Over the three years of the Junba Project, members of the cultural heritage community have had greater access to legacy records of Junba, including audio recordings, video and photographs. The Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre archive, managed by Katie Breckon, has been instrumental in this. Martin has used audio and video recordings, now held in the archive, to recall songs to assist in his own role as song-leader. He has also used video of his own performances as a dancer in the 1990s and early 2000s to teach young emerging dancers. Charles continues this practice and has instructed her sons on dances from Scotty Martin’s Jadmi-type Junba repertory, recorded by Barwick and Marett in 1997 at Bijili in the Northern Kimberley.

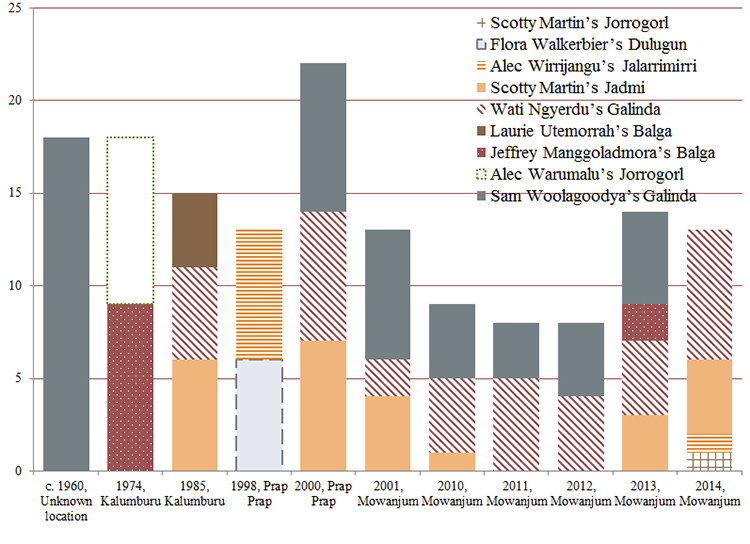

In Figure 8.2 we saw evidence of a decline in the number and diversity of repertories and songs being performed at public unelicited performance events between the 1960s and 2012. Figure 8.3 sets out the repertories and songs performed at the 2013 and 2014 Mowanjum Festivals, recorded by Treloyn and Maitland Ngerdu respectively. Whereas between 1985 and 2012 we saw a decrease in the number of repertories and songs performed, in 2013 and 2014 there was an increase back to the numbers of the 1980s and 1990s. Many factors may influence the rise and fall of particular repertories, including the format and time constraints of festival programs, funding availability, the entry and departure and re-entry of songs from repertories with the passing of songmen and dancers, as well as a decline in the number of performers. However, given the coincidence of the increase in unique songs and in the diversity of repertories at the 2013 and 2014 Festivals with the mid to final stages of the Junba Project, it appears that increased access and use of legacy materials in the community, and the revision of research design to include cultural heritage stakeholders across generations in the repatriation, recording, dissemination and documentation processes, may play a role in strengthening and sustaining endangered practices.

Figure 8.3 Number of unique songs by repertory performed at selected unelicited, danced public events to 2014.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have discussed community-led engagement activities around the discovery, return and use of records of Junba, and viewed data indicating the relative health of the Junba tradition from the 1960s to 2014. We have noted a coincidence between the maturation of the Junba Project and a revival in the number and diversity of songs and repertories performed at the annual Mowanjum Festival. The project falls within a history of intercultural research engagements around Junba dating back to at least 1938. Predominantly focused on collection, documentation and preservation, the large majority of these records are held in archives. However, there is a long history of recordings circulating in the Kimberley, incorporated into traditional systems of knowledge transmission embedded in and delineating the Wurnan. Through contextual details, data on the health of the Junba tradition, and dialogue with cultural heritage stakeholders, we have provided evidence of the benefits of multi-level community engagement in song research and repatriation, including the use of recordings as a conduit to ancestors and place, and thereby as a conduit to wellbeing. Through dialogues and stories told by multiple generations of singers, dancers, teachers and learners, we see how cultural heritage stakeholders can discover, use and create records of their songs to strengthen practices and research collaborations into the future.

Acknowledgements

Research presented in this paper was supported by AIATSIS (G2009/7458) and the ARC (LP0990650) with industry partners the Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre and the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre. The authors would like to thank the Ngarinyin, Worrorra and Wunambal cultural heritage communities whose traditions and knowledges inform this research, and particularly recognise Matthew Dembal Martin for his contribution to this paper.

Works cited

Deakin, Hilton (1978). ‘The Unan cycle: A study of social change in an Aboriginal community.’ PhD thesis, Monash University, Melbourne.

Grant, Catherine (2014). Music Endangerment: How Language Maintenance Can Help. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kirshenblatt‐Gimblett, Barbara (2006). ‘World heritage and cultural economics.’ In Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations, edited by Ivan Karp, Corinne A. Kratz, Lynn Szwaja and Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, 161–203. Durham: Duke University Press.

Knopoff, Steven (2004). ‘Intrusions and delusions: Considering the impact of recording technology on the subject matter of ethnomusicological research.’ In Music Research: New Directions for a New Century, edited by Michael Ewans, Rosalind Halton and John A. Phillips, 177–86. London: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Lommel, Andreas (1952). The Unambal: A Tribe in Northwestern Australia. Primary translation by Ian Campbell. Carnarvon: Takarakka Nowan Kas Publications, 1997.

Lommel, Andreas and David Mowaljarlai (1994). ‘Shamanism in northwest Australia.’ Oceania 64(4): 277–87.

Marett, Allan and Linda Barwick (2003). ‘Endangered songs and endangered languages.’ In Maintaining the Links: Language Identity and the Land. Seventh conference of the Foundation for Endangered Languages, edited by Joe Blythe and Robert McKenna Brown, 144–51. Bath: Foundation for Endangered Languages.

Moyle, Alice (1974). ‘North Australian music. A taxonomic approach to the study of Aboriginal song performances.’ PhD thesis, Monash University, Melbourne.

Moyle, Alice (1978). Aboriginal Sound Instruments. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Moyle, Alice (1981). Songs from the Kimberleys. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Redmond, Anthony (2001a). ‘Rulug Wayirri: Moving kin and country in the northern Kimberley.’ PhD thesis, University of Sydney.

Redmond, Anthony (2001b). ‘Places that move.’ In Emplaced Myth: Space, Narrative, and Knowledge in Aboriginal Australia and Papua New Guinea, edited by Alan Rumsey and James F. Weiner, 120–38. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Redmond, Anthony (2008). ‘Captain Cook meets General Macarthur in the northern Kimberley: Humour and ritual in an Indigenous Australian life-world.’ Anthropological Forum 18(3): 255–70.

Thomas, Martin (2014). ‘Turning subjects into objects and objects into subjects: Bones as a bridge between worlds.’ In Circulating Cultures: Exchanges of Australian Indigenous Music, Dance and Media, edited by Amanda Harris, 129–66. Canberra: ANU Press.

Treloyn, Sally (2003). ‘Scotty Martin’s jadmi junba: A song series from the Kimberley region of northwest Australia.’ Oceania 73: 208–20.

Treloyn, Sally (2006). ‘Songs that pull: Jadmi junba from the Kimberley region of northwest Australia.’ PhD thesis, University of Sydney.

Treloyn, Sally and Andrea Emberly (2013). ‘Sustaining traditions: Ethnomusicological collections, access and sustainability in Australia.’ Musicology Australia 35(2): 159–77.

Treloyn, Sally, Rona Googninda Charles and Sherika Nulgit (2013). ‘Repatriation of song materials to support intergenerational transmission of knowledge about language in the Kimberley region of northwest Australia.’ In Endangered Languages Beyond Boundaries: Proceedings of the 17th Foundation for Endangered Languages, edited by Mary Jane Norris, Erik Anonby, Marie-Odile Junker, Nicholas Oster and Donna Patrick, 18–24. Bath: Foundation for Endangered Languages.

Treloyn, Sally and Matthew Dembal Martin (2014). ‘Perspectives on dancing, singing and wellbeing from the Kimberley region of northwest Australia.’ Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement 21(1).

Treloyn, Sally amd Rona Googninda Charles (2014). ‘How do you feel about squeezing oranges?: Reflections and lessons on collaboration in ethnomusicological research in an Aboriginal Australian community.’ In Collaborative Ethnomusicology: New Approaches to Music Research Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians, edited by Katelyn Barney, 169–86. Melbourne: Lyrebird Press.

Wild, Steven (1992). ‘Issues in the collection, preservation and dissemination of traditional music: The case of Aboriginal Australia.’ In Music and Dance of Aboriginal Australia and the South Pacific: The Effects of Documentation on the Living Tradition, edited by Alice M. Moyle, 7–15. Sydney: Oceania Publications, University of Sydney.

Yu, Peter (2013). ‘Process from the other side: Liyan in the cultural and natural estate.’ Landscape Architecture Australia 139: 26–27. http://architectureau.com/articles/process-from-the-other-side-liyan-in-the-cultural-and-natural-estate.

1 Unelicited performances are here defined as those in which the selection and order of songs is determined by performers and members of the cultural heritage community, rather than by an outside researcher, as may occur in an elicited song documentation session. These performances are also typically danced.

2 Catherine Grant identifies 12 factors to assess the health of a musical tradition in a ‘Music Vitality and Endangerment Framework’ (MFEV) (Grant 2014, 163). While a detailed investigation of the Junba traditions within the Kimberley is yet to be done in relation to the MVEF, the suggested attrition of Junba since the 1980s may correspond to MVEF Factor 4, ‘change in the music and music practices’. Further research is needed, however, to take into account cultural factors and local perspectives on change and innovation within Junba.

3 It is possible that earlier recordings made by Yvnge Laurell in 1910 on Sunday Island in the southwest Kimberley contain some Junba; however, detailed listening with Ngarinyin, Worrorra and Wunambal Junba singers has yet to be done.

4 ‘Sustaining junba: Recording and documenting endangered songs and dances in the northern Kimberley’ (AIATSIS G2009/7458, researchers Sally Treloyn, Scotty Martin and Matthew Martin); ‘Strategies for preserving and sustaining endangered Aboriginal song and dance in the modern world’ (Australian Research Council, LP0990650, researchers Sally Treloyn and Allan Marett).

5 Audio recorded by Nick Thieberger, 2 December 2013, http://hdl.handle.net/2123/12254.

6 Audio recorded by Sally Treloyn, 16 January 2014.