3

Attitudes to animals

This chapter focuses on how animals are perceived by the Australian public. In generalising about ‘public opinion’, I recognise that it is a fraught term in the social sciences: each element of the phrase (both ‘public’ and ‘opinion’) is contested, and the connection between popular opinion and governmental action is similarly complex. ‘Public opinion’ can be used as a popular shorthand to describe every member of a given society, or in more specific and technical ways that focus on realpolitik: majorities, sizable minority groups, or small but influential groups (Wilson 2013, 276). As Splichal argues (2012, 25–32), this highly contested concept has shifted from a comparatively simple notion of public opinion as a single and expressible ‘average’ position on matters of clearly delineated public interest, to a fragmented, ambiguous notion encompassing majority and minority opinions and multiple publics and counter-publics (Fraser 1990). Often – particularly on complex or abstruse policy issues – the public has no opinion, but generates one only when prompted by pollsters or researchers, constrained by the limits and prejudices of their knowledge and the survey instruments of the interrogator (Bourdieu 1979). For our purposes, public opinion comprises a range of elements: respondents’ level of knowledge about an issue; how the issue is understood (that is, how respondents perceive the key elements of an issue, its causal drivers and the relationships between its actors); personal preferences about the issue; the status of the issue as either public or private (is it an issue the public expects governments to address?); and the issue’s ‘salience’, or importance to the public relative to other issues. Acknowledging these limitations, in this chapter I employ the best evidence available to describe where the majority of Australians stand on the issue of animal wellbeing. I ask: How do they act? Do they care about animal protection? What do they think about particular issues and debates? Do they want government action, or are they happy with the status quo?

For policy research, establishing public opinion is useful for a number of reasons. Understanding the relationship between public opinion and policy can tell us about the democratic responsiveness of the policy domain. Where opinion and policy are closely indexed, the policy domain is likely to be populist and to be structurally open to popular opinion and/or participation. Where opinion and policy are misaligned, the cause is commonly powerful entrenched interests resistant to popular participation (Kingdon 1995), or disorganised social interests unconnected to policy-makers (such disorganised interests are known as ‘latent interests’ or ‘potential groups’; Truman 1951, 168). Where politics matters to sufficiently large and motivated groups in the community, but entrenched interests are powerful, elites are likely to engage in purely symbolic or rhetorical responses to public concerns (Cohen 1997, 26). If public opinion is aligned with particular organised interests, this may convey information about those interests’ political resources, both tangible (such as their ability to fundraise, mobilise and recruit) and intangible (such as their perceived political legitimacy) (Giugni 2004, 124–5). Finally, where policy requires public participation (for example, where policy regulates the public, or conveys exhortations to voluntary behaviour), the alignment of popular opinion with the objectives and design of the policy can be critical to the policy’s success (Ammon 2001, 145).

As we will see, it would be a mistake to approach the population of Australia as a homogeneous group. On the question of animals and their treatment, ‘average’ attitudes and aggregate behaviours overstate the degree to which public opinion is stable. While some aspects of popular opinion can be clearly identified, other public attitudes remain pre-conscious and unarticulated. Understanding popular dispositions towards animals and their welfare nevertheless provides a context for understanding political action and policy-making. Looking at both the behaviour and the attitudes of Australians, in this chapter I will consider what is at stake in debates about animal use, and to what extent current public policy reflects popular opinion.

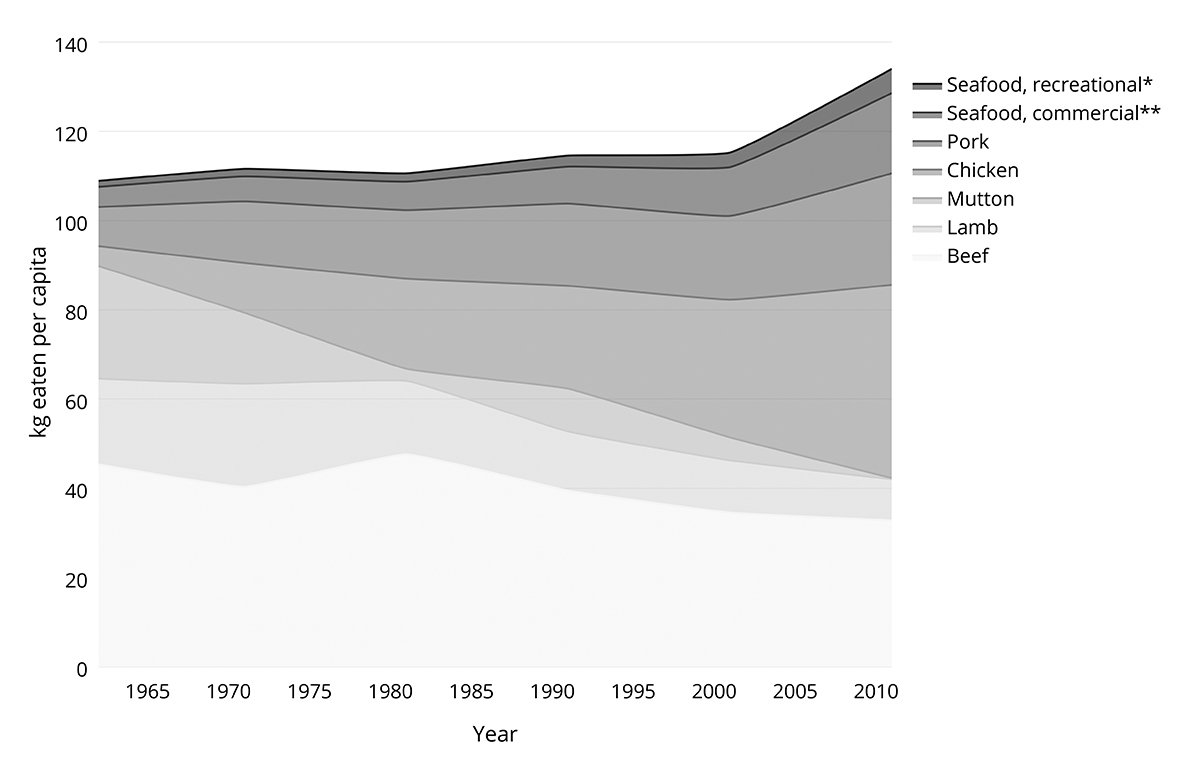

Figure 3.1. Australian annual per capita meat consumption, 1962–2010. Redrawn from base material provided by Wong et al. (2013). *Based on estimates made in NSW in 2000–2001 (Lyle and Henry 2002), an additional 30 percent by weight can be added for recreational fishing catch. **Estimated from ABS (2000).

How we love animals

On our plates

Australians like to eat animals; we are one of the largest consumers of meat in the world per capita, consuming almost twice the average of consumers in the United Kingdom (Franklin 2006, 223). This has cultural, historical and geographical origins. Since colonisation, meat has been a major feature of the Australian diet (Crook 2008, 7). (For some observers in the 19th and early 20th century, this level of consumption was tied to the coarseness of Australian culture, reflecting a tendency to see meat consumption as something spiritually pure individuals should avoid.) While recent decades have seen a shift away from particular types of meats (in particular, away from red meat and towards chicken), our appetite for meat has continued to grow (see Figure 3.1): during the past 50 years, the quantity of meat consumed per person has steadily increased. Our population of 23 million now consumes over half a billion animals per year (see Table 3.1). This equates to 22 animals per person, per year.

| Beef | Lamb | Mutton | Chicken | Pork | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2012–2013 | 2013 | 2013 | 2010 | 2011–2012 |

| Number | 2,574,000 | 9,614,600 | 384,5841 | 498,660,466 | 6,171,483 |

| Recalculated from | MLA 2013a | ABS 2014; MLA 2013b |

ACMF 2011 | Australian Pork 2012 | |

Table 3.1. Annual number of animals consumed by Australians

In addition to animals consumed as meat, Australia houses 16.5 million chickens as ‘layer hens’ to produce most of the 4.7 billion eggs consumed annually (Australian Egg Corporation Limited 2014).2 For every female layer produced, a male chick is discarded, either by gassing with carbon monoxide or by manual crushing. Based largely in Victoria, 1.7 million cows produce 9.2 billion litres of milk in Australia annually (Dairy Australia 2015), 40 percent of which is destined for export. To produce this ongoing stock of lactating animals, 900,000 calves are produced each year; these are either destroyed soon after birth or reared for their meat and skin (Turner n.d., 192–3).

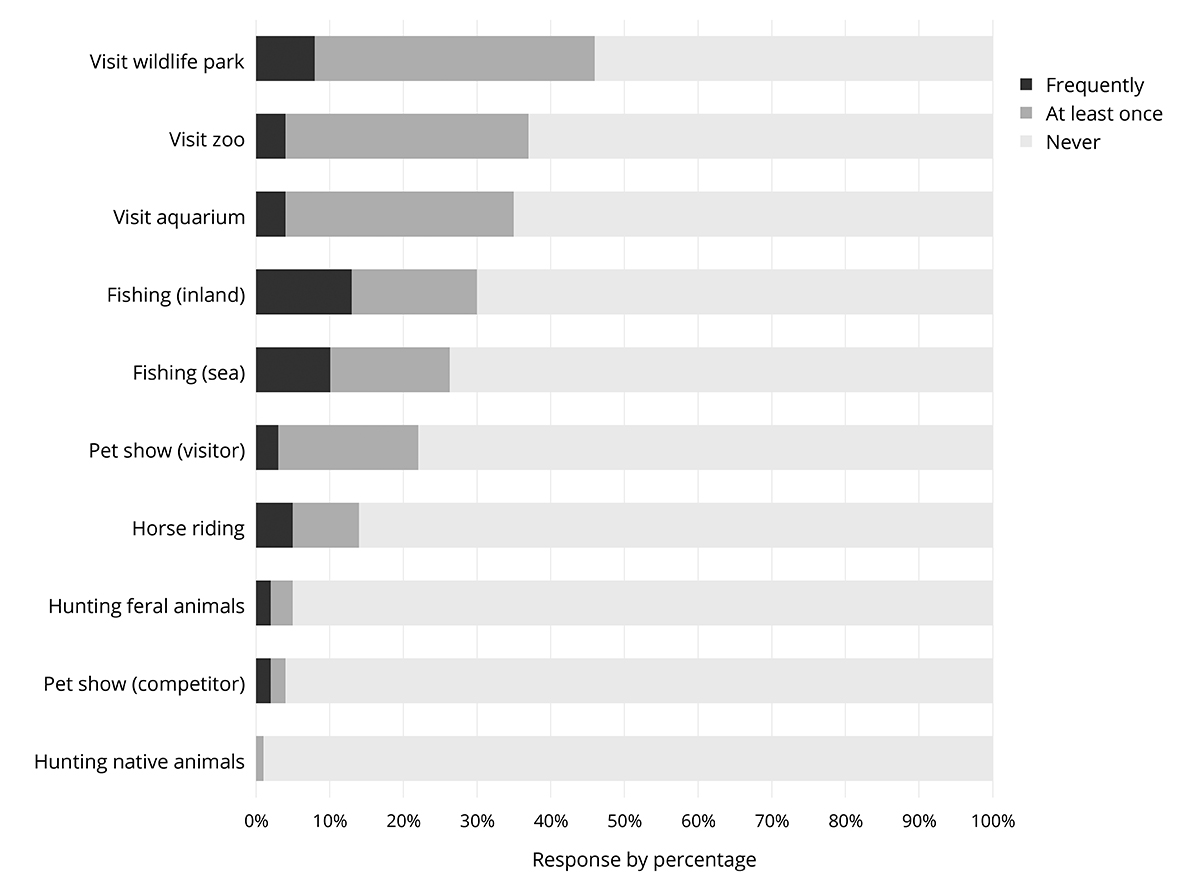

Figure 3.2. Popularity of recreational activities employing animals, as measured by frequency of participation. Compiled from Franklin (2007; n = 2,000).

On the track, on display, in the lab

In addition to the half billion animals we eat every year, animals are also ‘consumed’ by humans in a range of other ways, including for entertainment. In 2012–2013, 12,684 horses worked in the racing industry in Australia.3 Horse racing and breeding directly produce well over 4,500 ‘waste’ animals per year, most of which go to slaughter.4 Dog racing in Australia employs about 13,000 ‘named’ dogs (greyhounds are named at the start of their racing careers, usually when they are about a year old), while wasting 8,100 dogs per year.5 Approximately 83,000 ‘working dogs’ are used in agriculture and entertainment (Duckworth 2009). Australia is home to 95 zoos and aquaria, the largest of which hold thousands of animals for display and breeding purposes, only a small proportion of which are produced for the purpose of rejuvenating wild stocks. These staged exhibits are popular with the public, but are minor components of the overall recreational mix of Australians (see Figure 3.3). Rodeos report 22,000 animal ‘usages’ a year,6 recording approximately six injuries and four untimely animal deaths annually (Australian Professional Rodeo Association n.d.). Australia is home to eight circuses that employ a wide range of animals (commonly horses, dogs and exotic animals), while international animal circuses such as the Great Moscow Circus tour regularly and are still popular.

When it comes to directly killing animals for food or pleasure, Finch et al. (2014) estimate that there are between 190,000 and 332,500 active recreational land hunters in Australia. As we can see in Figure 3.2, however, fishing is significantly more popular than land hunting as a recreation.

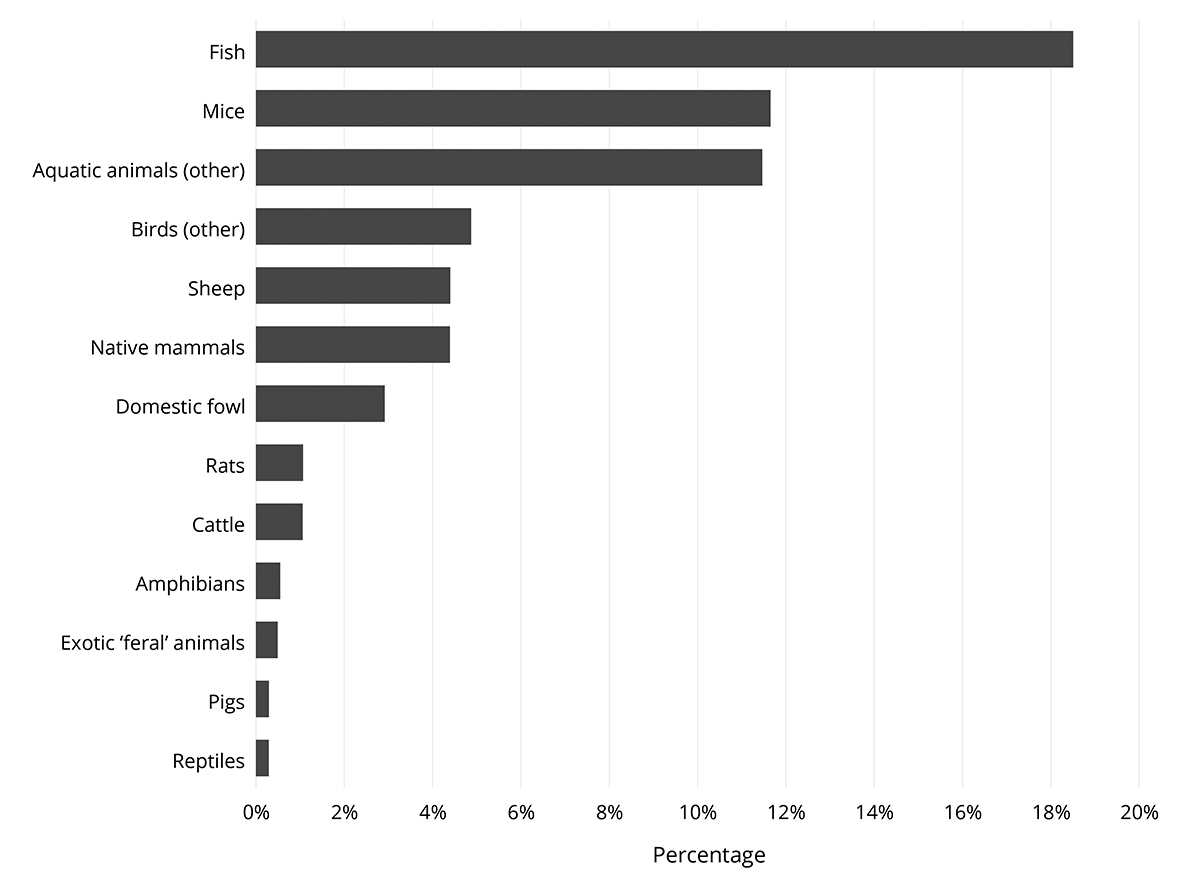

The number of animals used in research and teaching is difficult to estimate, with published figures ranging from 2.4 million per annum (Meng 2009, 50) to 6.5 million (Humane Research Australia 2014). Knight (2013, 12) notes that Australia is one of the top five users of animals in research globally. Part of the difficulty in estimation comes from differences in definition: lower estimates tend to exclude animals consumed to provide tissue, stock maintained as reservoirs of generic material, animals used in observation, and surplus animals that are euthanised (Taylor et al. 2008). In the historical context of anti-vivisectionist politics, this stems from a delineation between different types of animal research based on the extent of suffering involved, and/or the invasiveness of the experimentation. Thus the higher figure is likely more accurate if we are interested in the total numbers of animals used, but should be reduced by approximately half if we are interested only in use that ended in an animal’s premature death. A breakdown of animal use is provided in Figure 3.3, with sea animals and rodents the animals most widely employed for research, thanks in part to their rapid breeding cycles, the ease of handling them and the low cost of maintaining them.

Figure 3.3. Animals used in research and teaching in Australia, by type. Redrawn from Humane Research Australia (2014).

In our homes

Of the animals we commonly come into contact with, we pat the ones we don’t eat. In 2013, Australians owned 25.2 million companion animals. While fish are the most numerous, dogs and cats are the most commonly found in Australian households, as illustrated in Table 3.2. There are more pets in Australia than people.

| % of households |

Total companion animals (millions) | Rate per 100 persons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dogs | 39 | 4.2 | 18.2 |

| Cats | 29 | 3.3 | 14.3 |

| Fish | 15 | 10.7 | 46.3 |

| Birds | 13 | 4.8 | 20.8 |

| Other | 7 | 2.2 | 9.5 |

| Total | 63 | 25.2 | 108.9 |

Table 3.2. Australian companion animal ownership, by type. Recalculated from Animal Health Alliance (2013).

The use of the term ‘pet’ is a contested one, however, with the alternative term ‘companion animal’ increasingly commonly used.7 This distinction has political implications: it delineates between a view of animals as possessions, and one that focuses on their relational status with humans. The difference between possession and companion, however, tends to depend on the type of animal. While only one-quarter of birds are purchased as companions, around 70 percent of dogs and cats are acquired primarily for this purpose (Animal Health Alliance 2013). Thus, this categorisation homogenises a more complex pattern of human–animal relationships in which humans show a greater ethical concern for some animals than for others. According to Franklin (2007), cats and dogs occupy a special position in many Australian homes as companions or ‘family members’ (approximately 85 percent of households use the latter description). Reflecting the level of care many people feel for these animals, the pet industry in Australia is now an $8 billion sector. The Australian pet-food industry – that is, the slaughter of animals to feed companion animals – is valued at $3 billion per annum (Animal Health Alliance 2013). Pet food displays strong price inelasticity (that is, demand tends to remain static regardless of price changes) in the same way that demand for baby food is resistant to economic downturns.

How we see animals

From the preceding section, it is clear that animals in Australia occupy a paradoxical position: they are treated as intimates, or as commodities. Many of our social norms about the treatment of animals depend on how different species are valued and perceived. I will now examine popular attitudes to the treatment of animals in Australia: just what is the public view of animals and their interests?

| General community | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Male | Female | |

| AAS Score | 67.6 | 63.8 | 69.5 |

| s.d. | 9.3 | 8.7 | 9.1 |

| n | 550 | 186 | 364 |

Table 3.3. Animal Attitude Scale, population average. Signal and Taylor (2006).

Do we care?

At the same time as they use and enjoy animals and their body parts, Australians have a low tolerance for what they perceive as animal mistreatment. This means that Australians’ attitudes towards animals are complex and at times paradoxical. Table 3.3 provides an overview of the Australian population’s attitudes towards the wellbeing of animals. This table employs a modified version of the Animal Attitude Scale (AAS) initially developed by Herzog et al. (1991) and adapted for Australia by Signal and Taylor (2006). The AAS is a 100-point continuous measure8 pertaining to specific and general human–animal interactions, which is used to assess respondents’ attitudes to the use and treatment of animals by humans. The higher the AAS score, the greater the individual’s reported support for animal welfare. In Table 3.3 we can see that popular concern for animal welfare is modest in Australia, sitting two-thirds along the range between least and most concern. While gender is commonly cited as a factor in empathy towards animals (and is reviewed later), the variation within genders is greater than the difference between them on the AAS.9

Unpacking this overall indicator with some more recent data illuminates consistencies and inconsistencies in the collective attitudinal schema. First, Australians largely see animals as having the capacity for thought and emotion, as illustrated in Table 3.4. This appears to coincide with the sense that animals need protection from mistreatment by humans (Table 3.5). Referring back to the range of ethical positions mapped in Appendix B, it would appear that one-third of Australians subscribe to either a liberationist, strong animal rights or abolitionist perspective (Singer, Regan or Francione); two-thirds support either the status quo (as defended by Michael Leahy) or a weak animal rights position (as articulated by Mary Ann Warren and discussed below); and a small minority (about 4 percent) subscribe to the strongly anthropocentric views articulated by Descartes, Ryder and Kant.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36.6% | 42.5% | 17.0% | 2.8% | 1.2% |

Table 3.4. Response to the statement: ‘Animals are capable of thinking and feeling emotions’; n = 1,041. Humane Research Council (2014), 14.

| Statement | Agree |

|---|---|

| Animals deserve the same rights as people to be free from harm and exploitation | 30% |

| Animals deserve some protection from harm and exploitation, but it is still appropriate to use them for the benefit of humans | 61% |

| Animals don’t need much protection from harm and exploitation since they are just animals | 4% |

| Don’t know | 5% |

Table 3.5. Attitudes to animal treatment; n = 1,000. Essential Media Communications (2012).

For whom or what do we care?

It is interesting to see the stated willingness of nearly one-third of the public to attribute considerable rights to animals, given the behavioural statistics presented in previous chapters. This suggests either that a sizeable minority of Australians routinely engage in behaviours to which they morally object, or that they lack a coherent understanding of the language of ethics and its relationship to their own behaviour. This question can be resolved, to some degree, with the slightly older data presented in Table 3.6.

This also partially resolves the question of whether Australians subscribe to Leahy’s notion that the ethical treatment of animals should be informed by consensus practice (the wisdom of the crowd in setting ethical norms), or to Warren’s view that animals, as lesser beings who are subject to our care, should receive a level of treatment based on an independently determined definition of their ethical rights. The level of moral protection that the majority of Australians believe we should accord to animals mirrors everyday animal use. Thus, while significant numbers of Australians state that they support human-equivalent rights for animals, they make exceptions by excluding both the processing of animals into meat and pet ownership. This reveals an internal cognitive inconsistency between our stated higher-level values and practical lived experience. It also displays a high level of anthropocentricism: human interests are prioritised over those of animals.

This means that not all animals will be treated equally, even if they share characteristics that in ethical metrics would make them equivalent moral patients, such as cognitive ability, a capacity to suffer, or in-species sociability. (O’Sullivan 2011, 28–31). As we saw in Chapter 1, there is a historical tendency towards idiosyncratic interest in animal protection. This may have its origins in the general human tendency to create hierarchies and to put things and organisms into a moral order. From a sociological perspective, Arluke and Sanders (1996, 18) attribute this to the long tradition of hierarchical ordering discussed at the start of Chapter 2, and propose that people have traditionally delineated between ‘good’ animals (those used as pets or tools) and ‘bad’ (those seen as vermin, freaks or demons). From a policy perspective, early state intervention concerning animals often reflected class distinctions: some social groups were seen as more likely to engage in the mistreatment of animals than others, and in targeting these groups there was a recognisable transposition of human and animal characteristics (Baker 1993, 89). Hence the relative success of early movements focusing on stock and transport animals, compared to attempts by anti-vivisectionists to regulate professional men. There is also a gendered aspect to this success and failure. Middle- and upper-class women were very active in the early social movement; they were able to influence public policy regulating working-class men, but unable to regulate the conduct of the professional and capital-owning classes. While these women were politically more influential social actors than disenfranchised males, they remained subordinate to their male class peers.

This anthropocentrism, and the tradition of drawing ethical distinctions between companion animals, ‘useful’ animals, and pests, continues today. Taylor and Signal’s (2009a) survey, using a 50-point scale, illustrates this (see Table 3.7). Importantly, concern does not appear to increase gradually in line with perceived utility; rather, there is a rapid drop in concern as we move from animals that live in close proximity to most Australians to those that do not, whatever their perceived utility. This is illustrated in Table 3.8, in which 60 percent of the public support human-like legal protections for farm animals, but a third of the public remains unsure.

| Animal classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Companion | Commercial / utility | Pest | |

| PPP Scale | 44.6 | 32.0 | 30.5 |

| s.d. | 4.3 | 7.0 | 7.4 |

Table 3.7. Pet-profit-pest (PPP) scale (n = 210)

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24.3% | 36.1% | 28.3% | 9.7% | 1.6% |

Table 3.8. Response to the statement: ‘Farm animals deserve the same legal protections as companion animals’; n = 1,041. Humane Research Australia (2014), 14.

These findings are consistent with interviews I conducted with Australians engaged in animal protection, and in animal-related industries. Lyn White of the advocacy group Animals Australia highlighted the function of comparatively simple ethical heuristics in shaping behaviour and guiding legislation:

The first and most important aspect [of] advocacy is recognising the power of conditioned thinking and that many of our choices we have actually inherited from past generations. Animals have been put into categories of ‘friends’ or ‘food’ and their legal protections divvied up accordingly. (Interview: 24 September 2014)

Activists working to protect specific types of animals were aware that public perceptions of ‘their’ animal’s worthiness were a significant factor in mobilising support; they identified a vague ranking of different animals’ value in the popular consciousness. For Helen Marston of Humane Research Australia, this came into focus most clearly when the interests of animals were directly compared with those of humans (interview: 23 September 2013). This is expressed in the classic ‘Your child or your dog?’ ethical conundrum: if your house were on fire, this hypothetical poses, would you save your dog or your child?

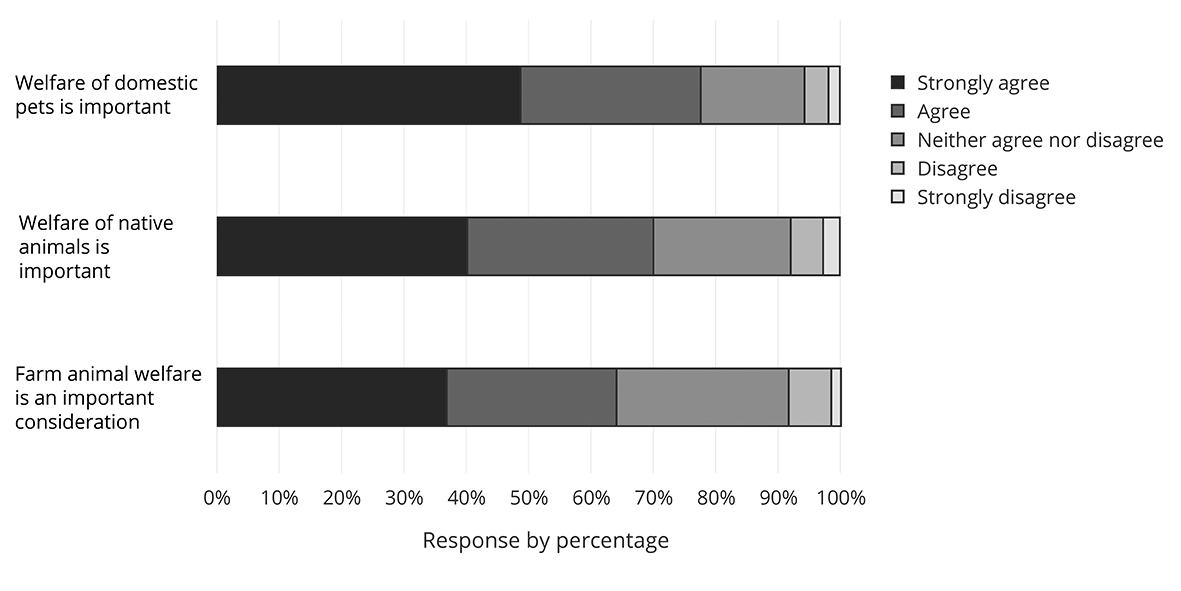

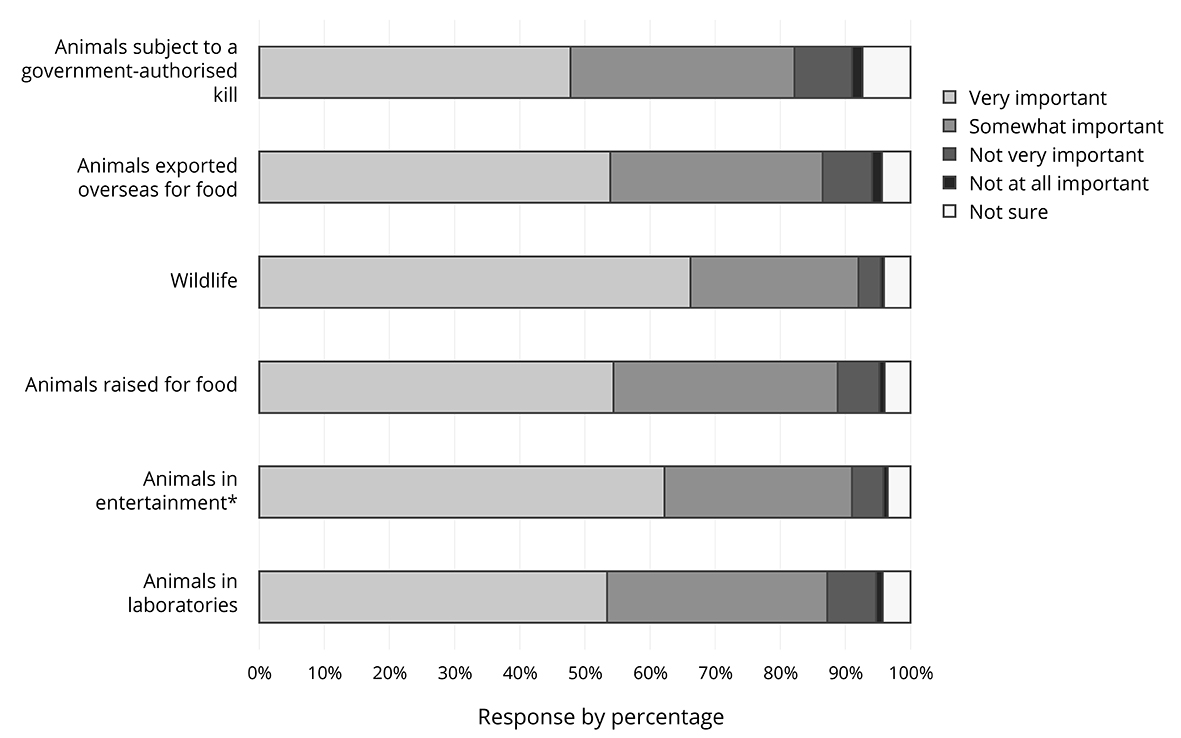

Figure 3.4. Victorians’ perceptions of the importance of animal welfare, by type; n = 1,061. Redrawn from Coleman et al. (2005). Categories have been compressed, extracted and redrawn from the original table.

In the minds of Australians, then, there is a hierarchy of concern for animals. This is evidenced in successive research (Figure 3.4) showing comparative concern for different animal types, and for animals in different contexts. Companion animals, wildlife and entertainment animals are generally most valued, followed by animals used in industrial settings such as farms and laboratories. Those designated as ‘pests’ sit at the bottom of the ethical ladder.

Figure 3.5 Importance of animal wellbeing, by type. *Includes zoos, aquariums, rodeos and racing.

This presents us with the interesting possibility that the way we define, categorise, rank and value animals reflects our sense of our ethical selves. A similar relative ethical scale has been used to define what constitutes a good person. Ian Randles of the Pastoralists and Graziers Association of Western Australia has argued that the more central a given type of animal is to a person’s life, the more likely it is that the person will judge themselves as either good or bad based on how they treat that animal (interview: 30 September 2013). As we will see later in this chapter, the inverse also appears to be true.

It would be premature to conclude that animal categorisation is clear-cut. As writers such as Malamud (2013, 35) have argued, boundaries are fuzzy and are not neatly aligned with the boundaries between species; animals’ use-value and relational position to people are just as influential. Ambiguities and borderline cases abound. Franklin (2006, 226–7), for example, talks about the emotional response of many Australians to the classification of feral horses as ‘pests’. Those I interviewed also observed this type of affective response. Dr Eliot Forbes of the Australian Racing Board remarked that:

There might be people who are quite happy to eat meat, for example, however, they would feel that a horse is not a livestock animal; it’s a companion animal, more akin to a dog or a cat, and so they ascribe the different set of values and expectations associated with that. Whereas other people may still continue to view horses as livestock . . . horses, in particular are interesting at the boundary between livestock and companion animals, and maybe how societies view that . . . [the] pendulum has swung more towards the companion side because we ascribed hero-type characteristics to horses such as Black Caviar, and we [in] the sport idolise our equine stars. (Interview: 9 April 2014)

This quote also demonstrates the important role of industry organisations in shaping the social meaning of animals. Black Caviar is not just a horse, but a cluster of symbolic meanings about excellence, competition, and the beauty of animal movement. Beyond her prize money, she is a brand, with her ‘own’ (really her owners’) branded products including horse-grooming products, DVDs, posters, artwork and medallions. She featured on the cover of Vogue Australia in 2012 and was the subject of a bestselling biography (Whateley 2012).

We are the 99 percent

In talking about animals, animal protection and the ethical attitudes of the public, we are thus confronted with a public that has complex, quasi-coherent and highly ambiguous opinions and understandings. One of the best ways to unpack this ambiguity is by exploring the question of ‘cruelty’. In legislative formulations of animal protection laws, as well as in popular parlance, cruelty is a word most commonly associated with the mistreatment of animals.10 While the word was once applied to humans and animals equally, mistreatment of humans now tends to be described using a range of other terms, such as ‘abuse’ and its various compounds (spousal abuse, child abuse, etc.). The meaning of ‘cruelty’ also appears to have been hollowed out, as indicated by survey data showing that 99 percent of Australians oppose cruelty to animals (the remaining 1 percent did not support cruelty, but were unable to answer the question).11 Thus, the word has become what semioticians call an empty or ‘floating’ signifier: a term without agreed meaning. Floating signifiers, can, however, have political and social significance.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | No opinion/ Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People who mistreat their animals should be punished in the same way as people who mistreat people | |||||

| 45% | 39% | 12% | 3% | 1% | |

Table 3.9. Attitudes towards animal cruelty offences; n = 2,000. Source: compiled from Franklin (2007).

Whatever animal cruelty is, the public both strongly oppose it and see it as a significant social transgression. In Table 3.9 we can see that 84 percent of the public say that they support equivalent punishments for animal and human mistreatment. This seems unlikely given the weight of other evidence to date, but Taylor and Signal’s (2009b) study of community attitudes towards the criminal justice system’s handling of animal cruelty cases showed that the public do have an appetite for increased punishments for animal cruelty (although it is hard to determine if this is based on an accurate awareness of what punishments are currently meted out).12

Looking at the inverse of cruelty, animal welfare, we can see that the public’s conception of what ethical behaviour might entail is neither homogeneous nor easy to define. When asked to rank a range of actions in terms of their relevance to animal welfare (see Table 3.10), most people ranked highly amorphous actions (in particular the not-very-helpful ‘not being cruel’) most highly. More specific actions taken by specific categories of actors (such as pet owners or farmers) were ranked significantly less highly, as were actions that might require a trade-off of some human interests. Animal welfare in this view is often construed as simply a matter of kind vs cruel treatment. There are alternative perspectives, however. For example, Hemsworth and Coleman (2001, 130) highlight the ability of animals to engage in ‘natural’ behaviour as an important and more meaningful measure of their welfare, particularly in highly unnatural contexts such as industrial settings.

| Preference | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventing animal cruelty | 29% | 24% | 13% | 3% |

| Humane treatment of animals | 21% | 19% | 17% | 2% |

| Conserving native species | 14% | 9% | 13% | 6% |

| Caring for our pets | 8% | 8% | 10% | 7% |

| Minimising the suffering of animals | 7% | 15% | 16% | 4% |

| Balancing the needs of animals and people | 7% | 7% | 7% | 15% |

| Protecting the rights of animals | 6% | 8% | 12% | 11% |

| Promoting good food quality | 5% | 3% | 3% | 39% |

| Farmers using best practice | 2% | 6% | 6% | 14% |

Table 3.10. ‘What animal welfare means to me’, ranked in order of preference; n = 1,000. Southwell et al. (2006).

This ambiguity presents problems for people engaged in mediating between industrial practices and popular opinion. A frequent observation by members of animal industry organisations is that there is a lack of public awareness of production practices, and of the reasons for those practices. When particular practices are publicly targeted by activists as examples of animal cruelty, this lack of public awareness can make discourse difficult (mulesing is a commonly cited example).13 Even within comparatively small industries, the definition of cruelty can be ambiguous. Russell Cox, executive officer of the Western Australian Pork Producers’ Association, recounted an interaction with a senior manager in a production facility:

He said, ‘Come down here, I’ll show you a pig I’ve got in a hospital pen. It’s lame.’ He said, ‘I want to show it to you.’ He showed me the pig . . . [it] had a lame left back leg. Had a bit of infection in his toe. Now, that can get worse and that can get better, but it had been treated. Now, he said, ‘I’m going to euthanise that animal’, and I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because if the inspector comes up here and sees that animal, there’s a possibility I’ll be charged with cruelty.’ I said to him, ‘Well, I disagree with that.’ I said . . . ‘You’re not giving the animal [time]. It’s being treated.’ Although [this pig] lives a very short life, like 16 to 24 weeks for pork- and bacon-weight pigs, you’ve not given the animal a chance to recover to live the fullness of its life. (Interview: 2 October 2013)

Thus, even for people working within the same industry, the definition of a core concept such as cruelty is contestable. This can lead to multiple interpretations and a tendency towards regulatory risk avoidance (as in this case), or highly variable application of policy. This anecdote also illustrates an ongoing debate about the nature and significance of suffering: suffering may be deemed greater or lesser depending on the animal’s capacity to recognise that its present state will be subject to change (sometimes referred to as ‘informed anticipation of future states’).

Ethical consumerism and animals

Given the difficulty of using public opinion as a gauge for what may be seen as acceptable practice, industrial actors such as those listed above use heuristics to gauge what the public means when it talks about acceptable treatment of animals. This often involves looking not at opinion data but at incentivised behaviour: just where do people put their money? Justin Toohey of the Cattle Council of Australia observed:

I mean, how do you actually measure [concern for animal welfare]? It should be measured by the number of people who actually buy based on animal welfare. Recent surveys show that five to seven percent of consumers walk through Coles’ and Woollies’ door buying on the basis of welfare, and that’s when it comes to eggs and pigs and poultry and pork – you know, the intensive foods. (Interview: 4 July 2014)

In other words, to what extent do Australians routinely engage in ethical consumerism – the deliberate selection of products and services based on the perceived ethics of their production practices?14

Unfortunately, the evidence on this question is scarce in the Australian context. Ethical consumption motivated by welfare concerns has been undertaken by a majority of Australians at some point (Table 3.11), particularly since the establishment of labelling systems for meat, dairy (and presumably eggs) and cosmetics, but this data only provides insights into activities respondents have ‘ever done’. It is less helpful in identifying more general or ongoing patterns of behaviour.

| Has your concern for animals ever caused you to do any of the following? | Yes | No | Do not know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bought ‘free range’ or ‘humane’ meat or dairy products | 61% | 33% | 6% |

| Bought products labelled as ‘not tested on animals’ | 57% | 34% | 9% |

| Boycotted a particular store or brand | 25% | 66% | 10% |

| Refrained from buying meat or dairy | 17% | 78% | 5% |

Table 3.11. Previous consumer action undertaken due to animal protection concerns; n = 1,041. Humane Research Council (2014).

Table 3.12 outlines consumers’ stated attitudes to a range of practices. Given the gap between consumers’ stated concern in this table and what shoppers actually do in practice, many clearly overstate their objection to some practices. This reflects the fact that while it is easy to state a concern, the practicalities of making ethical purchases are not always so straightforward. Where trade-offs are necessary, ethical concerns slip, sometimes considerably. Recent market research into two of the product categories most likely to have been subject to ethical consumption by Australians provides evidence of the impact of explicit trade-offs on the likelihood that consumers will engage in ethical consumption. Research (n = 126) conducted for the Australian egg industry demonstrates that many consumers who prefer free-range eggs will accept higher production densities if it means prices can remain within one or two dollars of cage-produced eggs (Brand Story 2012). In a more complex product category, cosmetics, research shows that female shoppers will subordinate their concerns about animal testing (which 43 percent of respondents cited as a factor in their purchasing decisions) to ‘value for money’ (cited by 59 percent) and product performance (such as achieving a ‘natural look’, cited by 50 percent) (Roy Morgan Research 2014a; n = 6,333).

| Acceptable | Unacceptable | Don’t know / no answer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breeding animals to sell in pet shops | 50% | 46% | 4% |

| Testing medicines on animals | 48% | 47% | 5% |

| Making milk-producing cows pregnant every year and taking their calves from them so their milk can be used by humans | 47% | 47% | 6% |

| Conducting other types of research experiments on animals | 40% | 52% | 8% |

| Killing male chicks because they can’t become egg-laying chickens | 24% | 72% | 4% |

| Testing cosmetics on animals | 17% | 80% | 4% |

| Keeping egg-laying hens in cages for their entire lives | 12% | 86% | 2% |

Table 3.12. Attitudes to ethical consumerism, as revealed by responses to the question: ‘Do you personally think the following uses of animals are acceptable or unacceptable?’ (n = 1,202) Abridged from the Vegetarian/Vegan Society of Queensland (2010). Rows may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Explaining inconsistency

The gap between reported public concern for animal wellbeing and actual public behaviour may be explainable as an artefact of survey research: survey respondents, regardless of how well constructed the survey, may give what they see as the more socially acceptable answers, rather than describing their real attitudes or behaviours. Alternative explanations are offered by Burke et al. (2014, 248), who examined ethical consumption in Australia. They looked at a range of ethical reasons, both positive and negative, for consumers’ choice of products and services. They found that consumers who are motivated to choose products with ethical characteristics (who accounted for 41.5 percent of their sample) were most likely not to purchase ethical products because of a lack of availability, or because the products were only available from speciality stores. The next most common reason for not purchasing the ethical product was cost. (These factors are of course related, as obtaining ethical products from remote or specialty suppliers can entail additional costs, both in time and money.) For consumers ambivalent about ethical consumption practices (25 percent of their sample), the primary barriers were lack of information, and scepticism about the products’ ethical claims. The final third of their sample lacked an interest in ethical consumption.

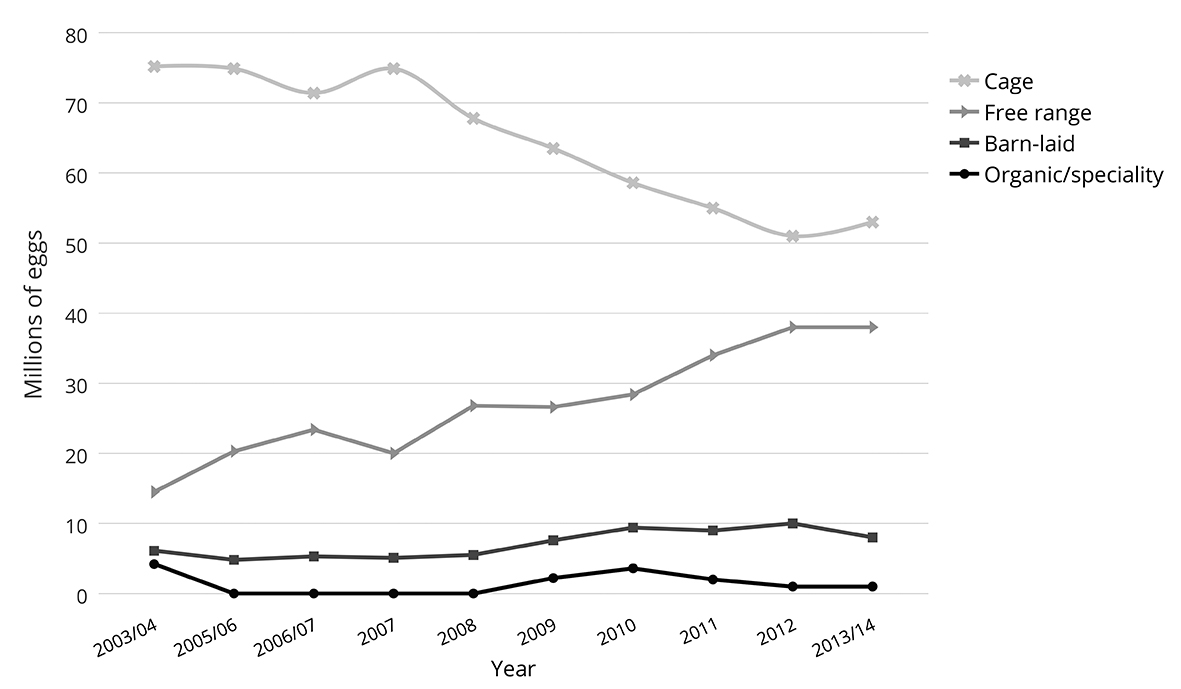

The issue of access or availability can be seen in the uptake of non-cage eggs in Australia over the last decade. As illustrated in Figure 3.6, the increasingly wide availability of free-range eggs (commonly promoted as having higher welfare standards) has been accompanied by higher sales, even in the face of a utility trade-off to consumers (that is, higher prices relative to cage eggs). Research by the Australian consumer advocacy organisation CHOICE in 2014 found that most purchasers of free-range eggs based their decision on the products’ presumed welfare advantages over cage eggs (68 percent purchased in part on this basis). Other reasons cited were concern for farmers (52 percent) and better taste (44 percent) (Clemons and Day 2015). As I will discuss below, while such figures may suggest an increased concern for animal welfare, they may alternatively reflect the satisfaction of a latent consumer preference.

Figure 3.6. Comparative egg sales as ethical consumption, 2003/04–2013/14. Compiled from Australian Egg Corporation Limited Annual Reports, 2004–2014.

While some of the stakeholders I interviewed did cite lack of availability as a reason for the gap between consumers’ stated preferences and their actual behaviour, lack of knowledge about production practices was mentioned more frequently. Many attributed this to increased urbanisation, the smaller proportion of people employed as farmers, and the movement of production animals out of cities (interviews: W. Judd, Director, Queensland Dairyfarmers’ Organisation, 19 April 2013; a member of parliament, South Australia, 25 September 2014; The Hon. Robert Brown MLC, Shooters and Fishers Party, 18 March 2014). The former NSW agriculture minister Steve Whan observed that the decline in the domestic slaughter of chickens had ‘disengaged’ consumers from the reality of animal death (interview: 19 March 2014). Similarly, in reflecting on his period managing agricultural shows, Roger Perkins noted that even these opportunities for urban Australians to interact with rural life no longer include demonstrations of animal butchering or routine invasive animal husbandry practices (interview: 24 April 2014).

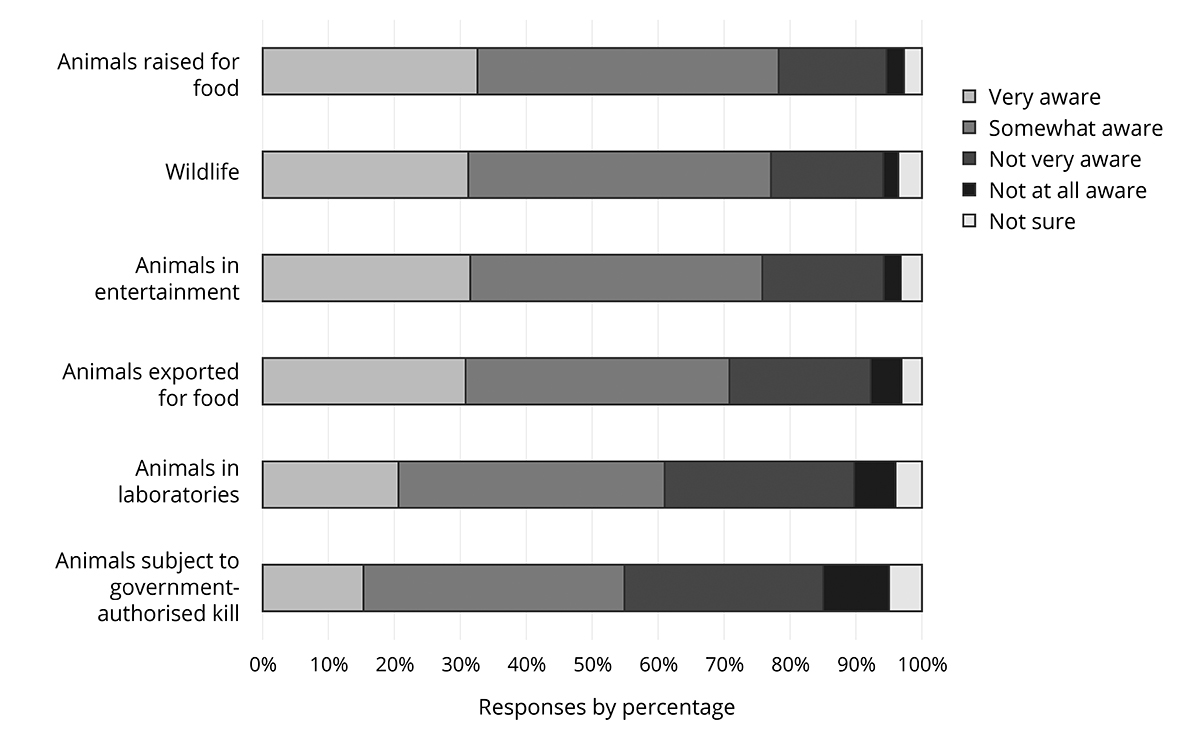

This question of knowledge and understanding has implications for the provision of ethical products in mainstream retail environments; demand and supply are both tied to the scale and effectiveness of activist campaigns (interview: a representative of the retail industry, 22 April 2014). Interestingly, while many respondents mentioned the low level of public knowledge about animals and animal production systems, the public tend to feel comparatively well informed about animal protection issues, particularly for those animals they most commonly have instrumental relationships with. This is illustrated in Figure 3.7.

Figure 3.7. Awareness of issues affecting animal wellbeing; n = 1,041. Humane Research Council (2014).

Importantly, attitudes towards animals appear to be established early, and tend to last a long time. Examining animal protection attitudes in America, Kendall et al. (2006) found that childhood background had the strongest effect on attitudes towards animal care. Those who grew up on a farm (strongest effect) or a non-urban area (strong effect) expressed the least concern about animal wellbeing. This study (n = 4,030) also found some evidence of an ‘underdog effect’, with people lower down the educational, economic and social ladder having greater concern for animal wellbeing, a finding that undermines the widely held belief that animal protection is a middle-class or elite interest. This is supported by comparative analysis of survey data by Franklin et al. (2001), who dismiss a correlation between concern for animal protection and ‘post-material’ values (that is, a lack of interest in material signals of social success) and education levels.

When it comes to the consumption of food, an expansive literature exists linking dietary behaviour to developmental socialisation and social norms. The acquisition of eating habits and food preferences has been extensively studied, often with sobering results for advocates of improved nutritional education (Judd et al. 2014). This research emphasises the enduring effect of a carer’s food choices on the future consumption habits of the children in their care (Orrell-Valente et al. 2007), and the intergenerational continuity of these practices (Bril et al. 2001). In addition, particular ingredients are not consumed separately, but resolve into culturally and temporally specific ‘cuisines’, defined by the basic ingredients they commonly employ, by their flavour profiles and by modes of preparation (Rozin 1996, 236). This cultivation of expectations and taste reinforces specific types of food ingredients within what we might call a person’s ‘food culture’. In addition, the relationship between these social norms and matching regulation further serves to reinforce (Giddens 1986) these practices and the classification of certain animal products as necessary or essential to authentic cuisines (interview: L. White, 24 September 2014).

The influence of social norms is important in shaping the behaviour of adults over time. These clusters of normative attitudes are shared within peer groups and provide strong indicators of what behaviour is socially appropriate (Brennan et al. 2013, 28–9); they can be used to identify what constitutes ‘cultural competence’ in a given community (Leynse 2008, 35–7). Sutton (2010, 218) highlights the role of food and taste metaphors in key social and religious rituals that link past and present. In terms of the treatment of animals, there is strong evidence that individuals measure their own food consumption (both what they consume and how much) against their perceptions of their peers’ consumption patterns (Rivis and Sheeran 2003; Lally et al. 2011). Importantly, social norms do not just determine tastes, but also define social relationships. Social positions are signalled by a range of cultural practices and relationships (Tallman et al. 1983, 35–7). This observation can be extended to how we view animals and our interactions with them. Thus, for example, the association of dog racing with working-class people (Young 2005) both reflects the activity’s history and defines and sustains its current identity.

Given that developmental norms about animal use are acculturated in childhood, the work of Bastian et al. (2012) can help us to understand how Australian adults maintain conflicting ethical positions regarding animals. Focusing on what they call the ‘meat paradox’ – the fact that ‘people’s concern for animal welfare conflicts with their culinary behavior’ – Bastian et al. investigated how people deal with this conflict. Based on a series of experiments, they concluded that those animals that are most commonly eaten are widely considered to have lower mental capacities than those that are not (n = 71). The researchers also found that, on being reminded that an animal was being raised for consumption, subjects (n = 66) offered a lower estimation of the animal’s mental state than did those who were not subject to the same prompt. Finally, participants who were about to eat meat strongly reduced their estimation of the animal’s mental capacity compared with subjects who were not (n = 120).

Overall, Bastian et al. argue that subjects adjusted their attitudes to align with their behaviour in order to deflect the unpleasant dissonance that would result if they were to recognise the animal’s subjectiveness. Even those who abstain from animal consumption often admit to long periods of avoiding the realities of their consumption habits (interview: individuals associated with the Sydney veg*n community, 8 May 2014). This avoidance is confirmed by market research undertaken by the meat industry. As Andrew Spencer, the chief executive officer of Australian Pork Limited, observed:

I think the vast majority of the community – and our focus group backs this up – the vast majority of the community eat meat and use products of animal agriculture in other ways such as wool and other things. They don’t have a direct interest in how it comes about that they have meat on their plate or a jumper on their back. And in fact, when asking them, they understand that an animal has to die for the process of meat production, but they don’t really care or know too much about that. So, that’s really where the community stands. (Interview: 23 June 2014)

Importantly, for Spencer’s focus group participants, this capacity for avoidance was predicated on a degree of trust in the meat industry. This demonstrates how the regulation of cognitive dissonance is both an internal psychological process, but also one tractable to environmental influences. Information that challenges assumptions about the source of meat, therefore, can provide a cognitive trigger to review an individual’s assumptions about the production practices underlying routine food purchases and consumption. These types of informational challenges are discussed later in this volume.

Implications

The Australian public’s attitudes towards animals and animal protection are complex. Public sentiment is variegated and inconsistent, with variation between and within species, over time, and between expressed views and exhibited behaviours. Both short- and long-term factors influence people’s beliefs and practices. For a politician or policy-maker, therefore, the area of animal protection policy is a democratic nightmare: Australians have strong but highly abstract views about these issues, a limited understanding of production practices, and no common language in which to articulate their concerns. In the democratic responsive or ‘weathervane’ model of politics (Dunleavy and O’Leary 1989), this type of context is likely to lead to relative policy stasis, as policy-makers wait for popular opinion to congeal or for an agenda to be constructed by pressure groups.

While this type of unstructured opinion presents significant problems for the political class in responding to issues of sudden popular concern – as we will see in the more detailed discussion of the live-export debate – the salience of the animal welfare issues for the Australian public is not high. While competing definitions exist,15 for our purposes ‘salience’ is the importance the public place on a particular issue relative to others that may be politically significant (Hutchings 2003, 143). The relationship between salience and the behaviour of policy elites is established by Epstein and Segal (2000, 66–7): elites are more likely to address issues deemed more significant by their core constituency. In Australia the comparative salience of a range of issues is illustrated in Table 3.13, with animal welfare ranked ninth in a list of ten issues of public concern.

| Order of importance of the issue | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 28% | 23% | 14% | 2% |

| Rising prices/inflation | 16% | 12% | 15% | 3% |

| Family relationships | 13% | 9% | 8% | 10% |

| Tax reform | 11% | 10% | 8% | 7% |

| Education | 10% | 18% | 18% | 3% |

| Terrorism | 7% | 5% | 8% | 12% |

| The environment | 5% | 8% | 10% | 4% |

| Unemployment | 4% | 9% | 11% | 7% |

| Animal welfare | 4% | 3% | 4% | 34% |

| International and trade | 2% | 3% | 5% | 19% |

Table 3.13. Comparative issue salience, ranked in order; n = 1,000. Southwell et al. (2006).

However, keeping in mind the comparatively large sub-group in this survey that ranked animal welfare as their fourth most important concern, we can argue that the issue’s overall low ranking does not reflect a complete lack of interest, but rather a potential or latent interest that could be mobilised and activated. This is attested by the public outrage over live export.

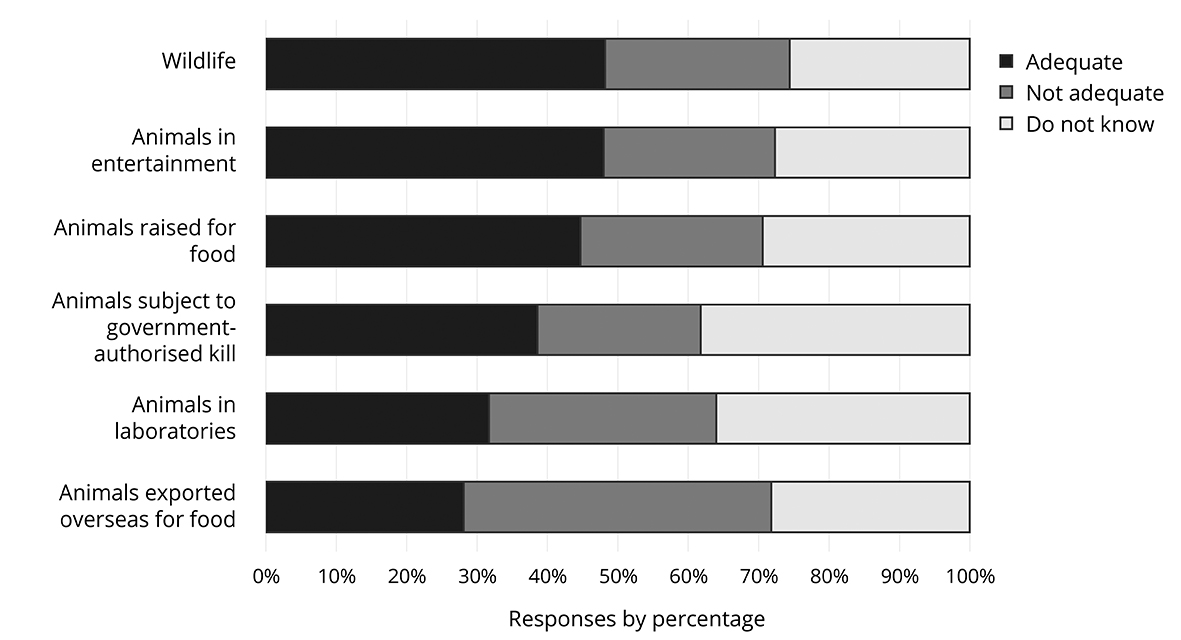

Figure 3.8 Perceived adequacy of welfare laws in Australia; n = 1,061. Source: Humane Research Council (2014), 18.

The comparatively low salience of animal welfare issues seems to be predicated on the widespread view that Australia’s performance in this area is, if not good, at least ‘not too bad’ (78 percent of respondents; Southwell et al.; 2006; n = 1,000). Given the previously identified modest level of concern for animal welfare (see the discussion of the AAS score above), the level of performance overall is consistent with public perceptions of regulatory performance. Less graduated data collected more recently (Figure 3.8) shows greater variation in the public’s perception of legal protections for different types of animals, as we would expect, indicating that averages may not capture the different levels of concern felt for different species and different types of animal use.

The extent to which public opinion about animal protection issues has changed over time is not possible to quantify accurately, as no genuine longitudinal data exists. Some increase in concern may be inferred by comparing the data from the last decade. The proportion of Australians who identified current animal protections as ‘poor’, ‘very poor’ (Southwell et al. 2006; n = 1000) or ‘not adequate’ (Figure 3.8) increased from about 22 percent in 2006 to about 29 percent in 2014. Differences between the two surveys in method and scale, however, make it difficult to draw more than a tentative conclusion. Certainly a dramatic shift in salience cannot be claimed from this data. As with the example of free-range eggs, changing consumption patterns may illustrate an increasing concern for animal protection (at least as it relates to one particular practice), but could just as easily be explained as a delayed response by industry to a latent consumer demand, or as a consequence of the slow diffusion of information about the product.

Overall, therefore, we can see that popular opinion about politically relevant issues can be divided into four areas of relevant knowledge:

- What is the salience of the issue (both overall and with regards to specific cases)?

- What is the public’s confidence in organisations involved in animal protection?

- What is the public’s knowledge of animals and industrial practices, and their understanding of the status of different animals as moral patients?

- What is the public’s capacity to articulate ethical concerns in a coherent manner?

While it is possible to learn about a given issue in a structured, deliberate manner, the public does not always do so. Some changes in public opinion reflect the influence of activist groups, and this has implications for decision-makers. For example, increased salience without a corresponding increase in public knowledge may lead to calls for action that are impossible or counter-productive. Declining confidence in regulation or production may mobilise public concern even if there has otherwise been no change in the issue’s salience. An increase in the public’s ability to identify and coherently articulate their ethical concerns would likely see a movement towards a more conservative ethical position in opinion polling (more accurately reflecting the public’s actual position), without actually reflecting a change in underlying attitudes.

Two sub-publics

In the preceding section I have attempted to paint a picture of what might be called ‘mainstream’ Australians’ attitudes to animals and their wellbeing. The convoluted story this presents demonstrates both the complexity of our relationships with animals and the difficulty of generalising about any nation, even a comparatively small one. As Asen (2000, 424–25) observes, while terms like ‘public opinion’ and ‘the public’ may invoke a cohesive political community that learns and reasons en masse, the reality is that the Australian population is a complex set of nested publics, overlapping but distinct, and a range of social and political dialogues makes up popular discourse. We can map out the major currents in this ocean of opinion, but we can never satisfactorily reify the populace into a single public.

Within this complexity, however, it is useful to highlight some overlooked groups relevant to an understanding of the policy debate over animal protection. In this section we explore two. The first is farmers and other workers in animal agriculture. This economic and cultural sector is significant both for the way it contributes to the wider public’s ideas about farm animal care, and as a potential site of policy intervention through the regulation of farm practice. Understanding the norms and practices of those who deliver policy, according to implementation scholars such as Lipsky (2010) and his successors, is critical to understanding the capacity to realise and implement policy change. Thus, it is important to understand how farmers think about animals and their wellbeing, as well as popular opinion about farmers and their performance in this area. The second sub-public consists of people who eschew animal products. This group’s opinions and behaviour may appear to be at odds with those of the majority, but it is a sizeable and growing group. It is also significant because of its connections with activists engaged in animal protection debates.

On the farm

Farm animals may not be central to the concerns of most Australians, but in sheer numbers they account for the majority of human–animal interactions in Australia. Farming practices therefore shape the lived experience of most of ‘our’ animals. Given the significance of farmers in this ethical story, it is interesting to note what a small and shrinking group they represent. There are approximately 101,422 farmers engaged in animal agriculture in Australia, making up less than 0.5 percent of the total population.16 This, of course, understates the significance of the sector to the Australian economy, and the corresponding number of people who work to support farmers directly or are employed ‘downstream’ in industries that process, move, store, value, insure, wholesale, retail, resell and dispose of the products of animal agriculture.

| General community* | Primary-industry sector** | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers | Meat workers | ||||||||||

| Overall | Male | Female | Overall | Male | Female | Overall | Male | Female | |||

| AAS | 67.6 | 63.8 | 69.5 | 61.8 | 64.8 | 58.2 | 58.4 | 60.5 | 56.0 | ||

| s.d. | 9.3 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 11.4 | 10.7 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 7.5 | 11.2 | ||

| n | 550 | 186 | 364 | 67 | |||||||

Table 3.14. Animal Attitude Scale, primary-industry sector. Compiled from *Signal and Taylor (2006) and **Taylor et al. (2013), both studies employing the same instrument.

To get a sense of how farmers view animals, we can compare the attitudes of people in the primary-industry sector with those of the wider community. Using the AAS scale, Table 3.14 shows that this group expresses lower levels of concern about animal protection than the wider community, suggesting a more instrumental view of animals. There is variation within the primary-industry sector depending on the type of workplace interactions respondents have with the animals they produce. Meat workers, for example, have on average lower levels of concern than farmers (see Table 3.14).

It is important to remember that the notion of a linear metric for concern may be misleading. Philips and Philips’ (2011) study of sheep farmers’ attitudes to animal wellbeing show how differences in AAS scores may be influenced by different conceptions of what aspects of animal care are significant. In this research the authors found that sheep farmers tended to conceive of animal wellbeing as the overall nutrition of their flocks, while placing less emphasis on other issues that were of concern to the general public (such as surgical mulesing without pain relief). These issues were given lower emphasis because of the cost that would be involved in addressing them (a trade-off similar to that seen in our data on ethical consumerism above). The farmers’ focus clearly ran counter to general public opinion about what constitutes acceptable treatment of farm animals; in a survey of Victorians, less than 10 percent (n = 1,061) said they would prioritise demand for food over other issues (Coleman et al. 2005).

This difference between the general public and the ‘sub-public’ of agricultural workers, it can be argued, reflects very different lived relations with animals. Where the general population’s experience with live animals revolves around a small number of highly individuated companion animals, farmers and related professional staff (such as rural veterinarians) have traditionally tended to focus on the meso-level, concentrating on the health of the overall population (interview: N. Ferguson, 3 October 2013). They measure animal welfare performance in ratios and against industry or regional norms (for instance, death rates may be measured in blocks of a thousand animals, and compared against sectoral averages). As one industry representative observed:

We produce 500 million-plus chickens a year. That’s a lot of chickens . . . even if you have a minimal mortality, [it’s] still going to sound, when you multiply that, like an awful lot of chickens dying out there every year, just as an example. So, it’s very easy to present things in a way that should put the industry in a bad way, whereas in reality, if you compared us to other countries, you know, it’s fantastic. So, it’s easy to play with figures and make someone look bad if you want to. (Interview: a representative of the chicken industry, 31 January 2014)

Animal protection and welfare, therefore, tend to have very different meanings in the industrial context: they are equated with overall health, as opposed to a concern for individual suffering. Wes Judd of the Queensland Dairy Farmers’ Organisation expressed this view when he stated that farmers equate animal welfare with good animal-husbandry practices (interview: 19 April 2013), where ‘husbandry’ includes a wide range of day-to-day practices. These practices are designed to balance productivity and health, within the necessary limits of the animal’s productive lifespan. Animals reared for things other than meat (such as dairy and wool) are likely to live considerably longer than meat animals; meat production has been increasingly optimised to create the fastest possible transition from birth to slaughter. Significantly, unlike animal protectionists, those working in the industry tend to see ‘welfare’ as relative, rather than as an absolute standard.

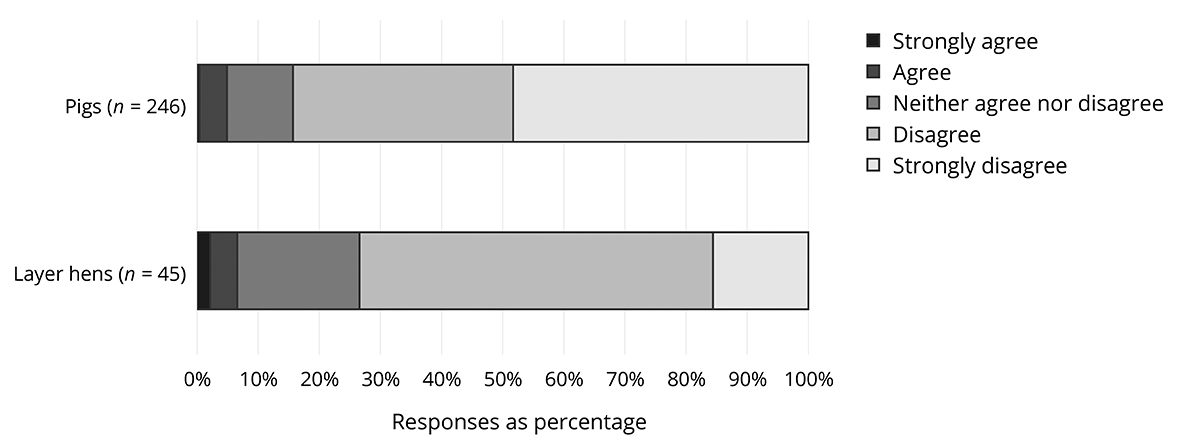

Thus, we are likely to see ‘town and country’ talking at cross purposes on the question of appropriate animal care, with the former emphasising individual treatment and the avoidance of suffering, and the latter looking at general health over the animal’s whole productive lifespan. While Philips and Philips’ sheep-farmer research stressed that primary producers and their families were cognisant of animal pain (to the extent that some farmers reported that other members of their families refused to participate in practices such as mulesing),17 other research with farm workers is less conclusive that animals’ pain is of ethical concern to producers. This is illustrated in Figure 3.9: fewer than 7 percent of Australian stockpeople believe that pigs or layer chickens are capable of experiencing human-like pain. This points to considerable variations between species, different production contexts and different types of farm workers. Unfortunately the evidence is scant.

Figure 3.9. Australian stockpersons’ perceptions of animals’ capacity to experience pain ‘like humans’. Redrawn from Coleman (2007).

Regarding farms and farming

While the Australian public may not prioritise farm animals in their ethical schema, popular attitudes towards farmers’ treatment of their animals is politically relevant. To what extent does the wider public see farmers as responsible for animal protection? How does the public assess farmers’ performance in this area, and their capacity to achieve the levels of care desired by the community? I have established above that popular (mis)understanding of farm practices develops by a complex and indirect process, particularly as it relates to welfare outcomes. While popular media often like to promote farming using idealised and anachronistic images of wooden barns and free-roaming livestock (see Chapter 4), critics of farm practices employ imagery of Fordist industrial production systems. This points to the public’s understanding of farmers and farming as a core element in conflict over the welfare of production animals.

We can establish that the majority of Australians see industrialised and intensive farming practices as both unnatural and antithetical to animal welfare (see Table 3.15).18 However, the use in this survey of the term ‘factory farming’, a term preferred by animal rights activists (and descended from Harrison’s 1964 book Animal machines), may have skewed the responses more negatively than they otherwise would have been. Australians oppose intensive animal agriculture, but what this table does not tell us is the extent to which Australians associate current animal agriculture in this country with ‘factory farming’. There is a large gap in popular knowledge of the practical realities of farms, and this highlights a major problem for both farmers and their critics: as O’Sullivan 2011 observes, not only are Australians ignorant of farm practices, they are largely unaware of their own ignorance. Moreover, although a simple majority of Australians designate industrial production as ‘unnatural’, over 60 percent of respondents still think these systems can deliver an acceptable product. Once again, popular opinion is neither straightforward nor easy to pin down.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | No opinion / Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern methods of ‘factory farming’ in the production of eggs, milk and meat are cruel | |||||

| 19% | 33% | 35% | 5% | 8% | |

| Modern methods of ‘factory farming’ in the production of eggs, milk and meat are unnatural | |||||

| 15% | 36% | 34% | 6% | 10% | |

| Meat production and processing industries can be trusted to ensure the safety of the meat product | |||||

| 10% | 53% | 25% | 6% | 6% | |

Table 3.15. Attitudes towards industrial animal agriculture; n = 2000. Compiled from Franklin (2007).

What the table does demonstrate is that, unlike many farmers, the public do not necessarily link animal welfare with good animal husbandry or effective production systems. Indeed, in a spontaneous-recall question of 1,000 Victorians, Parbery and Wilkinson (2013) identified that most respondents defined a ‘good farmer’ as one who demonstrated: professional competence (58 percent of respondents), environmental management (43 percent), and a hard-working nature (40 percent). Caring for animal wellbeing, on the other hand, was mentioned by only 16 percent of respondents.

Enduring public affection for farmers appears to indicate that for most members of the public, modern Australian farms are not synonymous with Fordist agricultural systems. Industry representatives report that their own market research reveals strongly positive opinions of farmers among the general public. This goes beyond perceptions of competence and hard work; farming is also viewed as an honest and trustworthy profession. Justin Toohey of the Cattle Council summed up the general consensus of many farm representatives:

We do have surveys around and evidence of a very high level [of] trust . . . [consumers rank] farmers about sixth to eighth at least in terms of trust, out of the list of 50 [occupations] . . . You’ve got the usual sort of second-hand car salesmen at the bottom. Farmers are up way, way, way up high, and that trust is kind of what we call . . . ‘licence to operate’ . . . and we need to retain that. And that sort of helps, I think, a lot of consumers to believe that farmers do have the welfare [of] the animals in mind, and in spite of the issues that happen in the media, we think we’re holding their trust pretty well. (Interview: 4 July 2014)

This optimism among industry representatives, however, was accompanied by concerns that the public’s positive perception of farming may be under threat, and that this could undermine farmers’ ‘licence to operate’ (interview: general manager (policy), National Farmers’ Federation, 14 November 2014). As the public depend on media representations for their view of farmers (see Chapter 4), there is concern in some agricultural sectors that the public are highly susceptible to negative depictions of contemporary animal agriculture.

Certainly, when Parbery and Wilkinson (2013) asked respondents to rank farmers’ treatment of animals using a ten-point scale, the average ranking was 6.8. This was lower than the average performance level respondents said they desired (8.7). If the public were more concerned about farm-animal protection, this under-performance could present a risk to farmers’ good standing. However, what is significant is that the public are not sure how much capacity farmers have to influence farm practices. Thus while survey respondents say that they want farmers to have a high level of influence on farm practices (4.2 on a 5-point scale), they see farmers’ actual level of influence as far more limited (3.5). The implication is that, even though the public may not be entirely happy with farmers’ treatment of animals, farmers are not held fully responsible for this shortfall. Organisations further along the supply chain are seen to be more responsible for influencing farm practices, including supermarkets (with an influence score of 4, compared with a preferred level of 2.1) and chemical and biological technology companies (3.5, with a preferred level of 2.1). Importantly, consumers assess themselves as having a low capacity to influence farm practices (2.7, with a preferred level of 3.6).

Overall, Australians have a high regard for a type of farming that is rapidly disappearing from our shores: the family-based small-business farmer using traditional methods that he or she determines and implements autonomously. Australians are more sceptical of intensive, conglomerate farming practices, which they see as unnatural and providing poor welfare outcomes for animals. Farmers, interestingly, are not seen as key determinants of welfare outcomes, suggesting that public opinion is oddly bifurcated in its concerns for farmers and for non-human animals.

The abstainers

Another important sub-public (or sub-publics) comprises what might be called non-consumers: those who regularly avoid the consumption and/or use of animals and animal products. While abstention might be considered just another type of the ethical consumption discussed above, we can distinguish these individuals as a distinct sub-public by their systematic or enduring commitment to avoiding or minimising animal use. While this distinction is one of degrees, delineating this group is important due to its size, and to its relationship with political activism.

These types of communities are sometimes poorly conceptualised by the literature on ethical and political consumerism. Theoretical literature tends to treat ethical and political consumerism as ‘lower-order’ social-change actions than electoral participation or formal membership of a political organisation. These practices have been characterised, for example, as ‘less organized, less structured, and more transient than traditional political participation’ (Stolle et al. 2005, 252). This view, however, is unlikely to resonate with those Australians for whom political consumerism is a holistic lifestyle, and who give a formal label to their consumption choices. In fact, formal participation in organisational politics (for instance in political parties, interest groups and social movements) is increasingly influenced by political consumerism, rather than vice-versa (Gauja 2012, 170). Formal political organisations are increasingly adopting product boycotts and corporate campaigns as major parts of their political strategies (Karpf, 2012).

In examining the proportion of the public who routinely or systematically avoid consuming animals, we find an array of practices that can be divided into a range of subclassifications and sub-subclassifications. As a reference for the discussion to come, Table 3.16 maps the major categories, although I will focus largely on vegetarian and vegan diets.19

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Pescetarian | Avoids meat, with the exception of sea-life |

| Pollotarian | Avoids meat, with the exception of bird-life |

| Pollo- pescetarian |

Avoids meat, with the exception of sea- and bird-life |

| Vegan | Avoids meat, animal products and animal labour |

| Freegan | Vegan, but will consume meat and/or animal products that have been recovered from the waste system (so-called dumpster diving), on reductionist/anti-capitalist grounds |

| Fruitarian | Generally follows a vegan diet and primarily consumes fruits, nuts and seeds |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian | Avoids meat and animal products, with the exception of milk and eggs |

| Lacto vegetarian |

Avoids meat and animal products, including eggs, but consumes milk |

| Ovo vegetarian |

Avoids meat and animal products, including milk, but consumes eggs |

| Flexitarian | Generally follows one of the vegetarian diets, but will occasionally consume animal products |

Table 3.16. Typology of Australian abstainers.

It should be recognised that such tables can be misleading. In this case, the potential deception takes two forms. First, jokes about the ‘vegan police’ aside (that is, the idea that vegans are humourless self-appointed moral arbiters of dietary compliance; see Greenebaum 2012), an individual’s identification with a specific designation may not be absolute. Is a self-identified vegan no longer a ‘real’ vegan if they undertake a cancer treatment originally tested on animals? Does the accidental but inevitable death of animals in agricultural farming invalidate all categories bar the flexitarian? Interviewees from this community recognised that some people who self-identify with such categories can exhibit a tendency to become ‘gung-ho’, or, in the other direction, to be more pragmatic (interview: individuals associated with the Sydney veg*n community, 8 May 2014). Second, reliance on such labels fails the scientific test of true typology: the categories are neither comprehensive nor completely exclusive.

To get a clearer sense of what actually occurs within this wider group, it is possible to map out the types of choices made by people who abstain from animals or animal products using three sorting questions: (1) What type of animal products are not consumed? (2) How is this consumption constrained? (3) When, or under what conditions, do exemptions from this abstention arise? An inclusive mapping of the choices made by abstainers reveals an array of practices, some of which fall clearly into recognised categories, and some of which exist within or between these groups.

How big is the abstainer subset of the Australian population? In this area some evidence exists, thanks to market research that has examined both self-identification and actual behavioural practices. This data, from 2010 and 2013, is presented in Table 3.17. The underlying research shows that, while 6 percent of the public identified as vegetarian or vegan (veg*n) in 2010, when questioned about personal consumption practices, the number of Australians who reported consuming no animal products at all was 2 percent. The four percentage-point difference can be explained by the existence of ovo- and lacto-vegetarians, flexitarians, pescetarians, pollotarians and freegans. A study of South Australians in 2003 produced similar results: from a sample of 603, 1.5 percent identified as vegetarian and a further 7.2 percent as semi-vegetarian (Lea and Worsley 2003, 407).

On the other hand, the 2013 data is somewhat ambiguous. In a 2013 survey the market-research firm Roy Morgan reported that 10 percent of Australians self-identified as vegetarians. If we employ the ratio of vegans to vegetarians from the 2010 results,20 as well as the that of self-classification to actual behaviour,21 we can argue that as at 2013, 3.33 percent of the Australian public meet the generally agreed definition of vegetarian, and 0.55 percent the generally agreed definition of vegan, together accounting for approximately 4 percent of the population. Thus, the total number of abstainers is somewhere between 900,000 and 2.7 million people, who range from strict abstainers to semi-vegetarians. Overall, this represents a considerable sub-public and points to an uptake in abstention in recent years, at a rate of between 0.43 and 1.66 percent of the total population per annum.

| Vegetarian | Vegan | Total veg*ns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010* | Self-reported | 5% | 1% | 6% | |

| Behavioural (assumed) | 2% | n/a (0.33) | 2.33% | ||

| 2013** | Self-reported (assumed) (i) | 10% | n/a (1.66) | 11.66% | |

| Imputed behavioural (ii) | 3.33% | 0.55% | 3.88% | ||

| Imputed number |

Lower estimate (ii) | 770,000 | 128,487 | 898,487 | |

| Upper estimate (i) | 2,310,000 | 385,500 | 2,695,500 | ||

Table 3.17. Reported and imputed veg*ns in Australia, 2010–2013. Compiled and imputed from *Vegetarian/Vegan Society of Queensland (2010; n = 1,202) and **Roy Morgan Research (2013; n = 20,267).

Why do these people abstain? The motivations of this large subgroup in the community sit within a range of ethical traditions. Referring back to Appendix B, the work of Adams and Donovan, Warren, Singer, Regan and Francione may be relevant in describing the various practices and motivations of this sub-public. However, it is not possible simply to equate consumption decisions with ethical concern for animals: consumption habits are commonly based on a combination of explicit and implicit factors that can be difficult to unpack. Moreover, not all abstainers are motivated only or primarily by animal welfare concerns. Several of the participants in the focused discussion of veg*nism highlighted the perceived environmental advantages of the diet as their primary motivation for abstaining from animal products (interview: 8 May 2014; M. Collier, 17 April 2013). Personal health and social trends can also be influential determinants for some individuals. Certainly, in comparisons between self-reported vegetarians and the wider public, Roy Morgan Research (2013; n = 20,267) found that abstainers were more likely to report that they:

- favour natural medicines and health products (50 percent more likely)

- follow a low-fat diet (47 percent more)

- enjoy health food (30 percent more)

- enjoy doing ‘as many sports as possible’ (23 percent)

- undertake exercise (7 percent).

Market research also supports the importance of age, showing that people under 35 are far more likely to identify as abstainers. Population health research also highlights the greater tendency of vegetarians and semi-vegetarians to reside in urban settings (12 percent higher than non-vegetarians; Baines et al. 2007, 439).

In a final demographic observation, it is important to note a gender bias: most Australian vegetarians are women. The higher participation by women in abstention is noted by an array of authors (Neale et al. 1993, 24; Janda and Trocchia 2001, 1227; Ruby 2012, 142; Parks and Evans 2014, 15), and we will see in Chapter 6 that women who engage in animal protection politics score higher than male activists on the Attitudes to Animals Scale. The source of this variance is unclear. Essentialist or developmentalist theories that women have greater empathy with, or concern for, animals (Paxton 1994) are undermined by the AAS scores presented in Table 3.4 and by other studies that looked at peoples’ stated motivations for adopting vegetarian diets (Lea and Worsley 2003). Lupton argues that the relationship between gender and vegetarianism is a social construct, reflecting a tendency in Australian society to masculinise meat consumption (1996, 105): many will recall the Australian Meat and Livestock Corporation’s advertising campaign of the 1980s featured the slogan ‘Feed the man meat’. Lupton also suggests that female vegetarianism may be a response to women’s relative lack of power in society (16, 57), in that control over the bodily consumption of food is a site of power for women in a patriarchal environment – particularly for younger women. Vegetarianism and other types of abstention represent an assertion of power or control, with women exercising their capacity to regulate both the type and quantity of their food intake.

There also appear to be some deeper differences between abstainers and the omnivorous majority. Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machines, Filippi et al. (2010) examined the automatic responses of omnivores, vegetarians and vegans to a series of images, some neutral and some featuring negative images of humans and animals (n = 60) – these images showed mutilations, murdered people, humans and animals under threat, torture, wounds, and the like (e10847). Using mapping produced by the fMRI, the researchers were able to compare the brain activity of these three groups. They observed that veg*ns displayed a greater tendency to generalising empathic responses to other species than omnivores (e10847).22 This may scale up into the political positions individuals adopt. Allen et al. (2000), from a study of New Zealanders (n = 348), identify that vegetarians have different underlying social values. They are more likely to reject social norms that lead to hierarchical domination and authoritarianism (they score low on the psychological measure of social dominance),23 and to prefer norms associated with equality, peace and social justice; they also place more significance on emotional states and awareness. The authors endorse the argument that systematic avoidance of meat is associated with rejection of conventionally constructed masculinity as both dominating and emotionally distant.