4

In the media

Chapter 3 examined one facet of the relationship between the ‘public(s)’ and their attitudes towards animals: what people think, as well as what they do. In this chapter we expand our analysis to examine what might be called the ‘discursive context’ in which animals and welfare-related issues are considered: Habermas’ (1989) concept of the public sphere. The public sphere is an idealised view of society as an open and participative arena of popular dialogue in which ideas are shared and issues debated. It exists in conversations between individuals and in groups, as well as in the opinion pages and in electronic media. In Habermas’ usage, the public sphere is more than just a ‘talking space’; it is an important part of the political and social fabric. Through dialogue, debate and disagreement, the public sphere facilitates the formation and articulation of the popular will: that general consensus of the public that provides direction for political elites, and the political legitimacy for them to enact public policy.

In today’s public sphere, the media are critical both as spaces for public discourse and as institutional participants in their own right. This is particularly so when it comes to the representation of animals and animal issues, given their remoteness from the majority of Australians’ day-to-day lives. Aside from the very specific subcategory of animals with which Australians live, most Australians have only very infrequent interaction with animals and industrial animal use (sea-life being the only animals consumed as meat that are commonly served whole or in a recognisable form). As Baker (1993, 3, 11–14) argues, this distancing has diminished our view of animals and has reduced their wider social meaning: where once animals featured in the public sphere in metaphor, star signs and heraldry, they have been reduced to being either pets or parts. Farms are geographically distant, remote in our consciousness, and obscured by hyper-real representation.

This distance increases the power of media to shape our understanding of animals and animal industry, to influence popular opinion about animal protection, and to set the agenda for animal-related policy debates. As Soroka (2002, 86–90) has observed, the media’s effect on public opinion is strongest when the issue in question cannot be directly or systematically observed by the public, as there is no alternative source of evidence. In the absence of competing information, the media’s representations of the issue – particularly if these representations are homogeneous and consistent1 – can come to dominate public understanding.

In this chapter we explore two general areas of media representation. The first involves a policy-orientated analysis of how animal welfare is reported in Australian newspapers. The second, following Tyler and Rossini’s (2009, 45–6) argument about the importance of mediated images of animals and animal industry in shaping cultural norms and standards, looks at how animals and farming are represented in popular culture, examining representations of animals and their welfare in a cultural context, rather than a political or public-policy one. Both approaches are important in understanding how public opinion about animal welfare policy is formed. Policy is a formalistic and specific discourse, but it is also predicated on cultural norms, rituals and assumptions.

Animal policy in print

We will first consider the representation of animal protection issues in Australian media between 2005 and 2014 (inclusive). While the print media’s circulation has been declining since the growth of the internet (Tiffen and Gittins 2009, 181), print remains a significant source of policy and political information. This is due to its continued consumption by social, political and economic elites, as well as the tendency for print publications to set the news agendas of more popular media such as television and radio (a phenomenon known as ‘inter-media agenda setting’) (Young 2011, 45–6, 147). I have chosen to analyse a decade of news articles because this span of time allows us to see policy debates and reportage across a number of changes of both federal and state governments and to delineate between significant trends and minor ‘blips’ of coverage. This aligns with a general consensus (Capano 2012, 455–6) that a decade is often the most analytically useful window: long enough to observe change, while short enough to comment on in a way that practitioners may find valuable.

What coverage looks like

In the broadest terms, examining this decade of coverage allows us to delineate between two specific periods in print reporting of animal welfare issues. Prior to 2011, print reporting on animal protection can best be described as idiosyncratic. Unlike other policy areas that are either systematically reported by all major newspapers (politics, crime, economic issues) or are ‘owned’ by specific mastheads (such as the Australian’s coverage of the higher education sector), animal protection is neither systematically reported nor owned by particular mainstream publications. Animal protection, unlike topics such as international affairs, crime and the environment, is not a specific ‘beat’, with journalists specialising in the area and developing a detailed understanding of the topic (Becker and Vlad 2009, 64–7).

This lack of focus has implications. The first is erratic news coverage. The quantum of coverage of animal welfare issues within each of the major Australian newspapers changed considerably from year to year during the decade. The second is the nature of the coverage. Without a dedicated beat, journalists writing in the area are unlikely to develop technical expertise or a deep understanding of the relevant policy and industry actors (their motivations, interests and reliability as sources), or to become sensitive to changes in the policy landscape. The third is the source of coverage. Prior to 2011, coverage spikes tended to be driven by the effectiveness of animal protection organisations in promoting specific issues and causes within their jurisdiction. This explains, for example, the high level of reporting during this period in the comparatively small jurisdiction of Tasmania (see Chapter 6).2 Overall, before 2011 news coverage tended to be erratic and highly variable, written by generalist staff writers, and focused on particular events rather than long-term trends or topics.

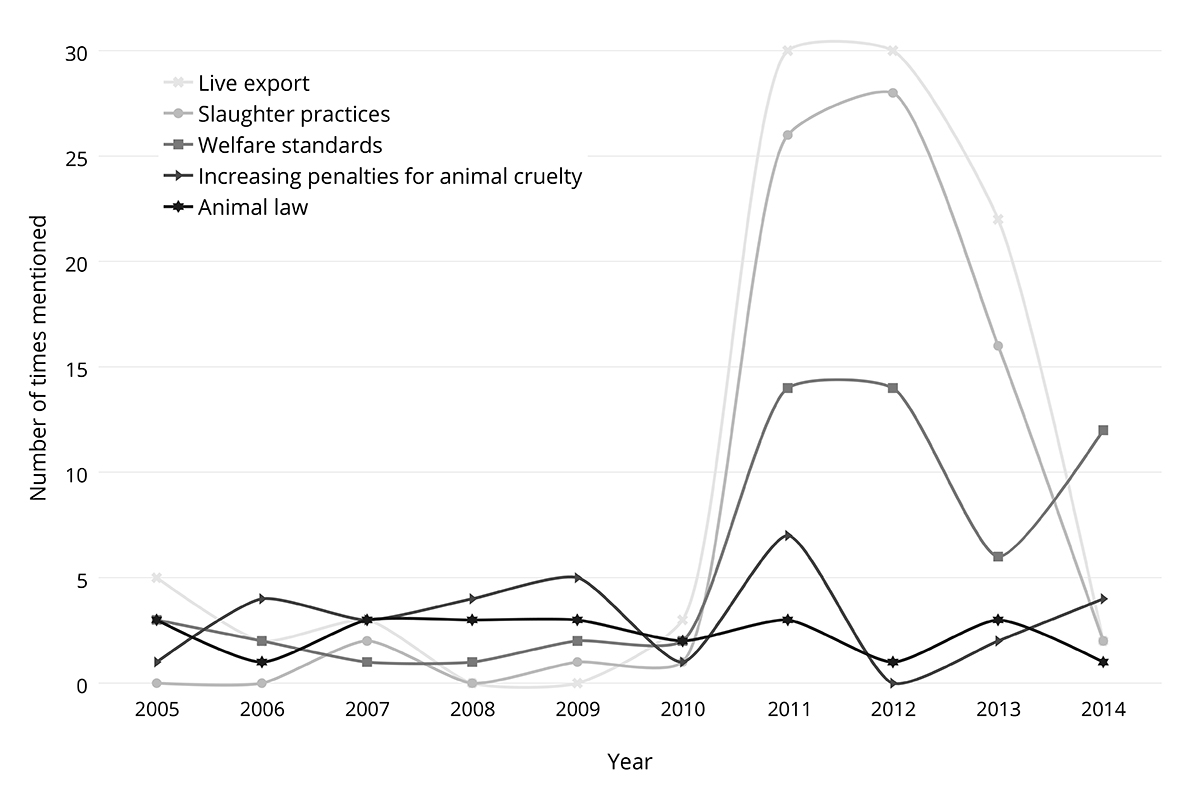

Since 2011 the proportion of coverage among the major outlets has become more structured: reporting on animal protection-related issues has become more systematic and consistent across the news industry. The cause of this drastic reshaping is the same event that motivated the writing of this book: as we can see in Figure 4.1, the issue of live exports of cattle to Indonesia is directly responsible for this change in Australian reporting. This event led to a considerable spike in the total news coverage of protection issues during 2011–2013. This increase remained highly focused on coverage of Indonesia and was directly tied to the popular, political and industrial reaction to the 2011 Four Corners special on Indonesian abattoir practices.

Figure 4.2. Number of events mentioned in newspapers, 2005–2014. Events mentioned fewer than ten times in the recording period have been omitted for clarity. The full dataset may be viewed at hdl.handle.net/2123/15349.

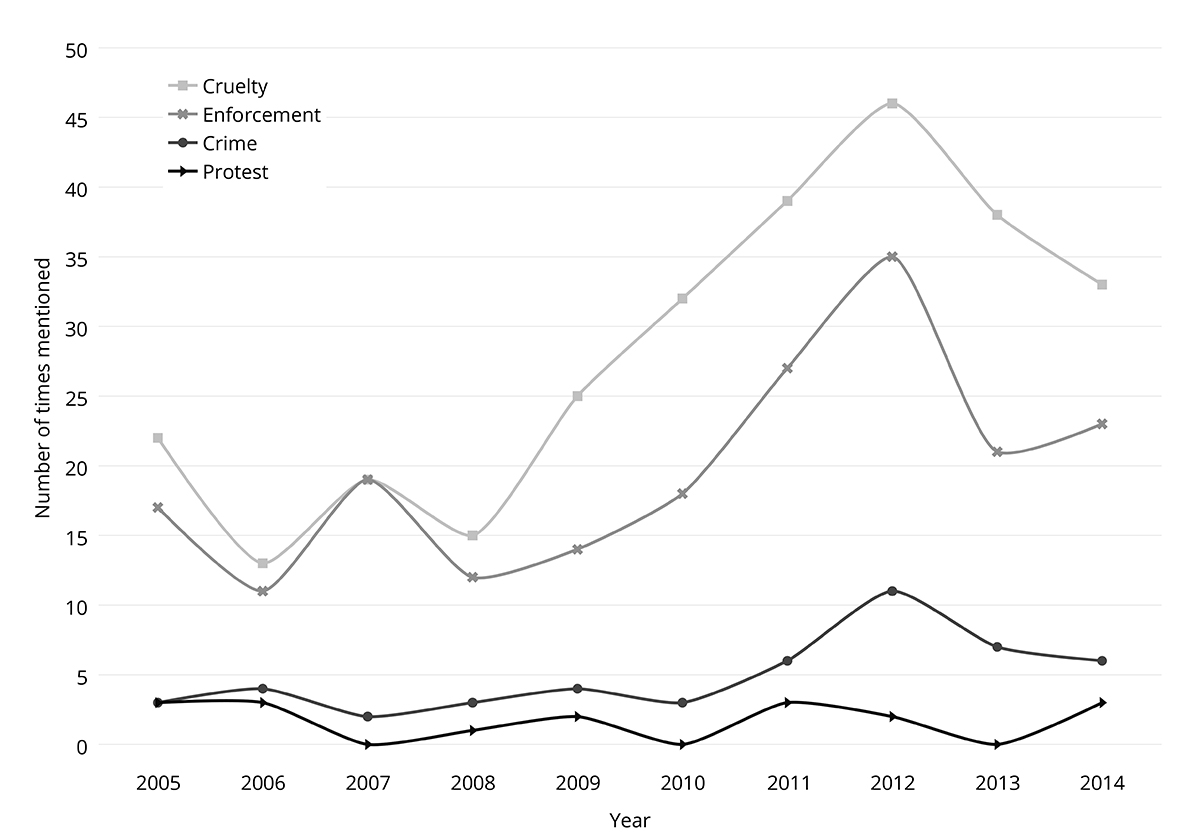

Regardless of this very narrow focus post-2011, the shift in the news agenda does represent a large increase in reporting on animal protection issues in Australian print media. This change did not, however, displace existing patterns of reporting. Prior to 2011, coverage of animal protection was mostly comprised of local crime reporting of cruelty offences. As we can see in Figure 4.2 (the reporting of specific events), acts of cruelty tend to be strongly associated with law enforcement in the Australian media, and the increased focus on live exports correlated with higher levels of cruelty reporting overall. Given the term’s lack of clear meaning in the community, as identified in previous chapters, the focus on animal cruelty cases is interesting. While animal protection organisations tend to focus on highlighting cruelty in farming and industrial contexts (see Chapter 6), the press tend to focus on acts of individual cruelty, especially those perpetrated against companion animal species3 in or near residential areas.4 Prior to 2011, dogs and cats were the focus of most reporting; from 2011 onwards they were later joined by the two major live-export species (cattle and sheep).

The Indonesian issue was such an unusual media event, the spikes it produced in the data set can make it difficult to see the other activist-led shocks from the same period. There were, however, two other major news-making events. PETA (USA)’s campaigns against the use of Australian wool by major fashion labels (in 2004 and 2011) are visible only as minor increases in reporting about sheep in 2004–2007 (see Chapter 6). Meanwhile Russia’s suspension of kangaroo-meat imports (2008, 2009–2012) because of concerns about food safety and handling is hard to identify amid the background noise of periodic cruelty cases involving kangaroos, although a small peak can be found in the 2009–2010 data. A further suspension of exports to Russia in May 2014 went virtually unreported (Tapp 2014).

Apart from these distinct spikes, most reporting of animal welfare issues in Australia during this decade consisted of crime stories. These stories tend to be police procedural in nature, prompted either by a court case and the result of a news organisation’s court beat,5 or by press releases about mistreated animals, often with appeals for information, put out by welfare organisations such as the RSPCA. In structure, these stories tend to take the form either of a ‘spot’ (where a case is presented and resolved, usually through a prosecution, in the course of a single story) or a ‘continuing’ story (in which the perpetrators remain at large or the court case is ongoing). Both types of stories emphasise events and facts over depth or a broader perspective (Tuchman 1978). Only the most ‘newsworthy’ spawn follow-up reports (bestiality prosecutions, for example, although exceedingly rare, are more likely to generate additional prurient coverage).

Exception and norm: ‘A bloody business’

One exception to this trend is worthy of detailed discussion. On 30 May 2011, the Australian national broadcaster aired its now-infamous episode on slaughter practices in Indonesia. Prepared in collaboration with the animal advocacy organisation Animals Australia and the RSPCA Australia, the episode included graphic footage of the slaughter of cattle exported from Australia. The premise of the episode was that, regardless of claims made by the live-export industry that considerable work had been done to ensure that slaughter practices in Indonesia were humane, actual practices remained rudimentary, with some animals experiencing a slow death at the hands of inexperienced meat workers. Animals Australia’s Lyn White had gained considerable access to places of slaughter and provided the ABC’s flagship current-affairs show, Four Corners, with video footage. It depicted the realities of animal processing in a developing nation in a way that is rarely, if ever, seen on prime-time television.

Not for the first time in the program’s half-century of production, a high-profile episode set the political agenda for an extended period. Every major newspaper reported extensively on the show’s claims and the subsequent fallout: the public reaction and popular mobilisation; the government’s decision to suspend the live-export trade with Indonesia; the industry’s reaction and counter-mobilisation. Parliamentarians reported an increase in direct calls to their electorate offices (interview: K. Thomson MP, Member for Wills, 26 June 2014; ABC 2011). The issue also had longevity, and was still among the top 30 policy concerns in the lead-up to the 2013 federal election (Roslyn 2013).

In his analysis of the issue, Coghlan (2014) highlights the emotional impact of the show and its focus on the suffering on individualised animals that are normally lost in herds. However, there is some debate as to the extent to which this impact was felt in rural constituencies.6 As the live-export industry was previously largely unknown among the general public, there was much scope for the story to ‘run’, with follow-up articles tracking policy debates and industry responses, background features into the industry and the long history of activist complaints about live export going back 30 years, and discussions of the lived experience of Indonesians, Australian production and distribution systems, access to refrigeration overseas, and a raft of related topics that gave the issue ‘oxygen’.

In managing the sudden influx of media demands, the industry was hampered by the comparatively small size of the export sector and divisions within it. This led to a slow and uncoordinated response to media inquiries. Justin Toohey of the Cattle Council observed:

When the crisis hit, again, it comes down to territorialism: ‘Oh, that’s live exporters, they need to deal with this issue, they need to be in the media, they need to fix this, they need to say why this happened and where we’re going with it.’ So, we rest, wrongly, on live export and their experts in that area. So, what happened . . . the chairman at the time of Live Corp, and the representative council, [were] so inundated with media reaction, that they couldn’t cope with the workload. They kind of almost went underground, and then in stepped the Cattle Council. (Interview: 4 July 2014)

Without a media strategy, the industry rapidly lost the capacity to control media coverage of the issue.

Thus, the coverage of Indonesian live exports was a unique media event in the decade in question. From an agenda-setting perspective, the case was the first animal protection issue to attract consistent and sustained media coverage at a national level. It appeared to attract considerable initial public interest, which was sustained and increased by ongoing reporting by journalists who developed expertise in the area. It was also distinctive in terms of content. The scope of the story tended to expand over time to include more actors (both political and industrial), and the coverage articulated the complexity of the industrial production process, as well as of the competing interests at play. Specific policy instruments developed to respond to the problem, such as the Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS), also received media attention. ESCAS was discussed in the media in unusual detail: in the content analysis discussed previously, it was the single most frequently mentioned act or regulatory instrument discussed in print in 2012, the year of its introduction. This coincided with a general increase in discussion of policy options in the print media in Australia. Specific policy instruments, such as the use of CCTV in meat processing and other animal-industry settings, are rarely directly examined in reporting of animal protection debates, but now began to receive more attention.7 While the live-export issue had largely subsided by 2013–2014, alterations to ESCAS were covered by the media, demonstrating an ongoing interest in the issue and its resolution. Some of these stories were clearly the result of monitoring of implementation by animal protection organisation. The press also reported changes to import quotas by the Indonesian government in 2015, and the signing of live-export market agreements with China the same year.

It could be argued that, although the issue of live exports received intense and sustained media attention for about four years, the coverage remained within the established patterns of animal protection reporting in Australia. Attention was paid to a specific type of animal seen as valuable within a specific context; while the coverage gave readers an insight into a part of the animal agricultural sector seldom seen in Australia, the reporting of the issue remained within a relatively narrow news agenda. This can be seen as an example of rapid agenda closure: once the possibility of a full ban on live exports was discarded in favour of the ESCAS, the option of total abolition disappeared from the popular debate and the industry resumed its trajectory towards growth. For the casual reader, the policy debate revolved around the extent to which ESCAS was being effectively implemented, and the cost–benefit of this model of welfare assurance.

This reflects a distinct contrast between the wide range of theoretical and ethical positions discussed in Chapter 2, and media discussions of animal protection. As Pendergrast (2015) argues, based on his analysis of media coverage of the live-export debate in the immediate aftermath of the Four Corners broadcast, while the issue was constructed by the media as an industry scandal, it was largely reported within a conventional framework that extended Australian industrial production norms overseas: the central question of much reporting was to what extent Australian cows received the same deaths in Indonesia as Australia. Seen simply as a ‘welfare’ scandal, the issue never escaped the perspective of ‘new welfarism’, as discussed in Chapter 2. While the issue’s longevity meant there was opportunity for journalists to branch into wider debates and employ narratives from different ethical traditions, this did not occur. Pendergrast found that more radical arguments, such as those of abolitionist thinkers and organisations, were excluded from media coverage, while more conventional ‘welfarist’ animal advocates were privileged.

Live exports, like individual cases of animal cruelty, tended to be reported through an episodic rather than thematic frame. Thematic framing places a specific event or issue into a broader context, highlighting the ongoing nature and underlying causes of an issue. Episodic framing, in contrast, tends to emphasise the particular event, focusing on proximate causes in an ahistorical fashion (Iyengar 1991). This leads to an understanding of the immediate event but limits deeper learning. Episodic accounts tend to focus on individualistic attributions of blame or responsibility, rather than on systematic or societal causes. In addition, as Gross (2008) argues, while episodic reports tend to evoke a greater emotional response in media consumers (as seen in the public response to the Four Corners episode), they are often less persuasive instigators of policy change. Without a connection to wider systematic or causal narratives, the individualised focus can be engaging but not necessarily productive.

What gets covered, how, and why?

The lack of an established media beat for animal welfare presents a problem for all parts of the animal welfare debate. Pendergrast’s complaints, outlined above, come from a critical animal studies perspective, with an emphasis on animal liberation (ICAS 2015). From the perspective of established and emerging organisations that promote enhanced welfare standards within current legal paradigms, however, the view was quite different. One senior animal-welfare advocate reported that it was relatively easy to get media coverage for his organisation, observing that ‘the media absolutely loves reporting on animal cruelty matters’ (interview: 5 September 2014). Similarly favourable coverage was reported by a number of RSPCA representatives (interviews: M. Mercurio, CEO, RSPCA Victoria, 4 June 2013). As Michael Beatty, the head of media and community relations for the RSPCA Queensland, noted, such access enabled these organisations to get their preferred visuals communicated, maximising the impact of their media coverage:

If I get [a] large article in the paper or on the TV news, inevitably [a peer in another industry] either texts or rings me up and says, ‘You bastard, I’m working with lumps of coal and you’ve got little animals.’ Yeah, so it’s a lot easier. (Interview: 16 April 2013)

Importantly, however, using particular cruelty cases and images of individual photogenic animals to ‘sell’ stories may perpetuate the use of episodic framing, and so limit the range of narratives employed by the media.

While welfare organisations are able to generate considerable ‘free media’, industry tends to speak through paid advertising. Outside of rural media, industry representatives can see journalistic interest as problematic; they complain that the media are prone to generalise about whole sectors based on the conduct of atypical ‘bad eggs’ (interview: A. Spencer, 23 June 2014). Rural media have been critical of mainstream coverage of issues such as live export for this reason, arguing that the activists’ footage was unrepresentative of industry practices overall (Nason 2015). The scale of animal agriculture, its wide geographic distribution, and a lack of sustained reporting in major mainstream media work against the type of thematic framing that might put ‘bad eggs’ into a broader context. This is particularly true of reporting about foreign nations, where language barriers and the decline of local bureaux hamper reporting.

Media coverage of live exports, and the dominant role of activists’ footage in initiating public debate, infuriated many in animal industry, including those outside of the sheep and cattle sectors; some saw it as the ill-treatment of fellow farmers by an ill-informed press (interview: N. Ferguson, 3 September 2013). Some conservative politicians were suspicious of the national broadcaster’s motivations in reporting on animal protection issues. This took place against the backdrop of a wider public controversy about the ABC’s editorial position, a debate that has flared up over the last decade (Boucher and Sharpe 2008, 82). One South Australian MP observed:

[The ABC] mainly run [the story] in one direction, and they run it really hard, and they make it easy for the activists to get a run. You don’t see that happening with the commercial media . . . There wouldn’t be any DNA on it, but I think there are people in high places within the ABC that are probably fairly closely associated with the animal activists, and prepared to give them a fairly good run. That’s my observation . . . it’s really interesting because [on] the other side of the debate, the ABC has Country Hour, they have Landline, and they traditionally [have] been fairly focused on agriculture and rural people, but on this [story] they do [so] much damage [to farmers] because it’s been blown out of all proportions. (Interview: 25 September 2014)

As discussed above, others in the animal industry have expressed concerns about the industry’s own media management. The extent to which the MP’s view of the media is shared within the industry appears to vary. Such views do reflect a sense of existential threat within some communities, generated by some of the recent media coverage.

Interviewees also identified the technical and scientific knowledge of journalists reporting on animal protection issues as a significant factor in the quality and fairness of reporting. The level of scientific literacy among journalists reporting on technical policy has been raised as a problem more generally (Dunwoody 1999, 76). In the area of animal protection, the media’s relationship with scientific organisations can be tenuous at times. The director of the Victorian Bureau of Animal Welfare expressed some exasperation in dealing with journalists:

The most difficult group I have to deal with are the media. They can be quite vindictive. I can provide them with what I think is balanced information and they’ll write pretty awful articles. So, we tend to steer away from them. (Interview: 21 August 2013)

However, avoiding the media can be counter-productive in the long run. If, following negative experiences with journalists, the technical experts in such organisations tend to send media requests ‘upstairs’ to the minister’s office, they may miss an opportunity to steer public discussion towards a more technical, and therefore thematic, understanding of issues and events. This ensures reporting remains in the ‘political’ space.

An alternative explanation for the intensity and longevity of the Indonesian live-export issue credits the power of national identity. This argument links the atypical coverage of this specific story with wider cultural concerns and currents in Australian society. In Fozdar and Spittles’ 2014 analysis of the coverage of the live-export issue, they highlight the significance of the continual identification of the cattle in question – both in the original Four Corners broadcast and subsequent reporting – as ‘Australian’ or, more informally, as ‘our cows’. It seems not all cows are equal in the eyes of Australians: cattle raised in this country are given more and different moral concern than cattle raised overseas. Interestingly, in a nation created by a shared xenophobic urge and presently in the throes of a decades-long political debate about the recognition of refugees’ rights (Jupp 2007), it is surprising how quickly metaphorical passports were made available to the bovine.

This outpouring of concern, Fozdar and Spittles argue, was a response to persistent negative characterisations of Australians in the international and domestic media. The Australian public were criticised by one British journalist for having ‘tiny hearts’,8 and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has consistently been critical of the detention of asylum seekers.9 Thus, the outpouring of concern for cows at slaughter provided a counter to other examples of our profound lack of humanitarianism. In addition, Fozdar and Spittles argue, the story played on Orientalist traditions of seeing Western behaviours as civilised and Eastern practices as barbaric.

Additional evidence of this tendency can be found in the response to domestic animal-welfare issues. When similarly confronting footage emerged of live animals being used as training bait in greyhound racing in 2015, the public and media response was more muted, with only modest coverage of the initial report, subsequent investigations and government response. This difference is notable, given the greyhound story involved clear breeches of anti-cruelty laws as well as attempts by owners and trainers to gain unfair advantage in competition. Similarly, the media and the public paid comparatively little attention to international bans due to sheep mulesing and kangaroo-meat processing. In all three cases, the chief difference was that the concerning practices took place within Australia, and were largely conducted by Australians. This explanation accords with Baker’s (1993, 67–71) analysis of media representations of ‘Britishness’ in the UK, and of the perception that affection for animals and concern for their welfare is a British national characteristic. According to Baker, this perception is articulated via popular media reports that emphasise the ordinary Britisher’s revulsion at the practices of other nations (he cites a famous case of British tourists ‘duped’ into eating dolphin sausage; News of the World, 22 July 1990), or at the behaviour of immigrants.

In Australia, we can identify a similar association between ‘Australianness’ and concern for animal welfare in the mobilisation or confection of public concern about halal food production practices. This issue has been taken up by parts of the Australian political right (for example, through the Senate inquiry into third-party certification of food, established in May 2015, largely at the insistence of South Australian Liberal Senator Cory Bernardi) and by far-right groups (Gartrell 2015). The final committee report, released in 2015, largely dismissed these concerns (Economics References Committee, 2015). Image 12 shows animal rights messages displayed by the Party for Freedom outside a halal expo in the western suburbs of Sydney in 2015. The Party for Freedom was established circa 2013, and takes inspiration from the Dutch party of the same name (Partij voor de Vrijheid) set up by Geert Wilders (Flemming 2013). The group is an offshoot of the Australian Protectionist Party and its main policy focus is anti-immigration, especially concerning Asian and Muslim migrants. Under its current name the group has undertaken small demonstrations outside supermarkets that have celebrated the end of Ramadan (2014), run anti-refugee counter-protests (2015), and participated in the Reclaim Australia protests (2015). It is unlikely that animal protection is the group’s primary concern; it does not even mention the issue in its policy documents.10 Halal slaughter and a professed interest in animal protection are used to exaggerate the differences between ‘Australians’ and the small Australian Muslim and Jewish communities who are granted variations to conventional slaughter practices.

While it is significant that the majority of Indonesians are Muslim, this does not explain the unusual interest in live exports to this particular destination. Fozdar and Spittles are likely right not to attribute this to simple cultural chauvinism. (Reports about live exports to nations in the Middle East have not prompted the same response.) Why, then, did the public take such an interest in the Indonesian story? Ongoing characterisations in the Australian media of Indonesian society and its government provide some clues. Of all the nations in the region, Indonesia has received the most media attention in Australia in recent decades, particularly in extensive and often sensationalist reporting of Indonesia’s treatment of ‘our people’ (Noszlopy et al. 2006). Since 2005 the Australian media have been obsessed with the treatment of Schapelle Corby, a young white woman arrested for importing a commercial quantity of cannabis into Indonesia. Concurrent with the live-export coverage was intensive scrutiny of the trials and executions of the ‘Bali Nine’ heroin importers Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran; much Australian coverage was critical of the application of the death sentence (described as ‘barbaric’ by public officials, academics and in media editorials; Lines 2015; Maguire 2015; Goodsir 2015) and of the Indonesian political and judicial machinery (McNair 2015; ABC 2015). Indonesia thus serves a kind of cultural double duty in the Australian imagination: Indonesia’s treatment of animals shows the true humanitarianism of Australians, while its systems of governance treat Australians as little more than animals.

Which animal protection issues attract media attention, and how they are reported, thus appear subject to a range of factors. Domestic issues are reported sparingly or idiosyncratically, with little continuity over time. Issues that cross the threshold into major public debates are few and far between, and determined by a range of highly unpredictable variables and cultural insecurities.

Variations across the nation

Notwithstanding the generalisations outlined above, there is considerable regional variation in the Australian print media. Looking at the newspaper data set, we can sort coverage by the primary location of the reporting newspaper and its audience (‘urban’ or capital-city newspapers, ‘regional’ or non-capital municipalities, and ‘rural’ areas) and compare different regions to the national average. (These categories are, of course, to some degree misleading. Many ‘capital city’ newspapers are effectively state or national papers and are read widely in regional and rural areas, both in print and online.)

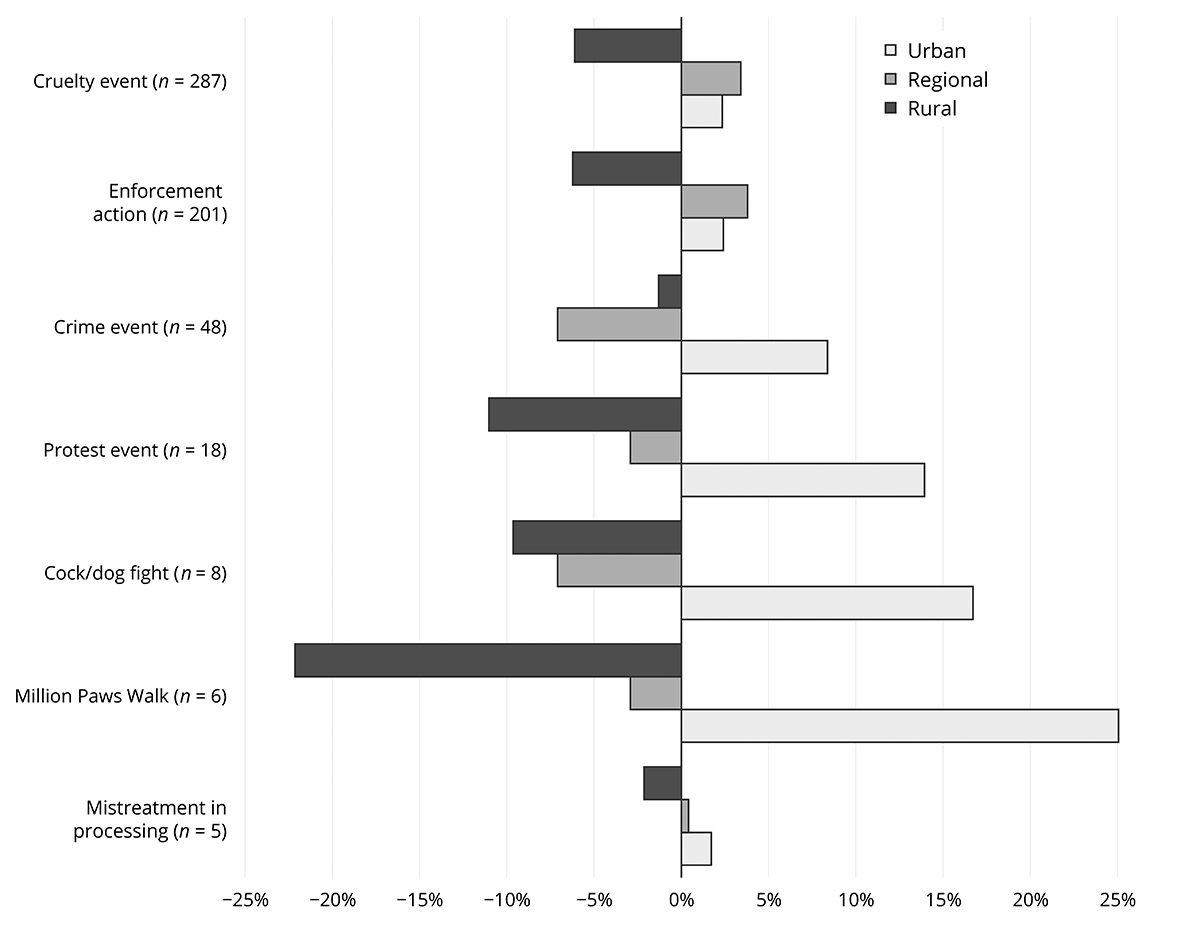

Figure 4.3. Regional variations in event reporting from the national average (percent), 2005–2014.

This analysis shows that there are considerable differences between metropolitan and rural media coverage (where ‘metropolitan’ includes both capital and regional cities). As we can see in Figure 4.3, specific animal-cruelty events receive greater coverage in metropolitan newspapers than in rural papers. Events run by welfare and activist organisations (such as protests and the RSPCA’s annual mass ‘dog walk’) also tend to receive more coverage in capital-city newspapers. This can be explained in part because such events are more likely to occur in larger population centres. But it also appears to be in line with the attitudinal orientations identified in the comparative Animal Attitudes Scale data presented earlier in the book. The greater coverage of animal cruelty issues in metropolitan papers aligns with the higher levels of concern for individualised animals’ wellbeing identified among metropolitan people.

Looking at the reporting of animal protection issues between regions, Figure 4.3 demonstrates a logical divergence in the level of reporting. Issues strongly associated with rural industry are more frequently reported in rural newspapers. This includes situationally specific issues (such as live exports), as well as ongoing issues affecting rural production (such as stock transport, the development of new welfare standards, and the use of CCTV in production settings). Reflecting the findings in Figure 4.2, meanwhile, the policy implications of animal cruelty events are more often discussed in urban newspapers (such stories include calls to increase penalties for animal cruelty, changes to animal law, adoption of surplus animals, and methods of mitigating cruelty in society). Chicken-cage issues are an interesting outlier, perhaps reflecting the tendency for chicken production to take place closer to population centres than other kinds of animal agriculture; chicken-cage issues are disproportionately discussed in regional newsprint.

Print media does tend to behave in a predictable manner with regards to the editorial choices of mastheads in different geographical markets. Newspapers cover the stories they anticipate their target audience will be interested in. In doing so, the print media tend to create regionally specific content that serves the interests of local readers even if that means concealing some information (Pariser 2011). For all the talk of ‘national conversations’ about policy issues, the public sphere is fragmented into different communities, distinguished from one another by both interest and geography. In addition, some of the concerns of industry about the lack of depth and context in media coverage of farm production are confirmed by this comparison: more detailed discussions of animal production policy tend not to leak into the popular print media of the major population centres. Importantly, this underlines the comparatively superficial level of concern identified in Chapter 3.

Animals on screen

It is also useful, in attempting to understand popular attitudes to animals and their welfare, to examine the representation of animals in popular culture. The value of looking at culture (Raymond Williams’ ‘one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language’; 1976) was touched on in Chapter 3’s discussion of the power and origins of our social norms concerning the treatment and use of animals. While technical and rational debates about policy issues may be the ideal of democratic liberal theorists such as Habbermas, culture provides an important anchor to policy-making. Policies that uphold accepted norms are seen to reflect ‘common sense’. Those that run counter to folk logic run the risk of being dismissed as belonging to das Wolkenkuckucksheim – ‘cloud cuckoo land’. In her philosophy of decision-making, Hannah Arendt (1953, 387) identifies the intimate relationship between politics and social norms: the ability of elites to demonstrate awareness of, and be simpatico with, popular ‘common sense’ is the most important political skill in modern times. For Arendt, political common sense is not an innate characteristic of ‘the great’, but the product of a politician’s engagement in the wider cultural context (what she calls Weltsinn, a ‘sense of the world’), including an understanding of their constituents’ cultural history and traditional practices (Borren 2013).

Mass or mainstream culture (Davis 2014, 28) shapes policy-making by creating a policy terrain in which it is politically safer to tread the well-worn paths of social norms than to scale the heights of innovation. Culture provides the metaphorical language with which complex policy can be explained, as well as everyday examples and justifications for decisions (Stone 2002). Popular media’s selective and distorted representation of animals habituates a particular view of animals, and constrains the public’s understanding of the realities of the lives of animals and the people who work with them. As we have seen in the public reaction to the Four Corners episode about live export, when viewers’ limited awareness is challenged, the shock can be profound.

Television’s power lies in its capacity to cultivate viewers’ attitudes over time through the repetition of social norms and stereotypes (Gerbner and Gross 1976). Television has been, until very recently, the most significant communication channel in the media life of most Australians. Effective television presents complete vignettes or synecdoches of life to the viewer, creating linear narratives about the role of animals and people in society. But visual media is also richly symbolic. As Tait (2013, 183–4) states, this can have a powerful effect on how animal meanings are constructed and sustained:

animals are engaged by humans in the process of embodying and hence performing human emotions through the mis-en-scène and the constructed framing in television and cinema. Humans unthinkingly transact and communicate their emotions with and through other animals . . .

In doing so, our cultural unconscious, and the meanings we give to particular animals, are exposed. Drawing upon a content analysis of each of the five major free-to-air television stations during prime-time viewing, we can get an understanding of how animals are most commonly depicted on Australian screens. We will then turn to an example of how less mainstream attitudes are depicted in popular culture: the representations of atypical diets on television.

Any analysis of Australian television must also include advertising. Advertising can be a highly important indicator of popular culture for a variety of reasons. First, it indexes against the popular. That is, more popular products and services generally receive more advertising, by nature of the political economy of media (Herman and Chomsky 2002). Second, because of the increasingly compact way advertising is communicated in all media, it is often informationally dense and uses sophisticated interpretations of popular culture to create its messages. Animals in advertising are often used as symbolically rich metonymies of broader contexts (Berger 2011, 62). From a content analysis of Australian free-to-air television, therefore, we can get a sense of which animals appear on Australian television screens, how they are depicted, and in what contexts.

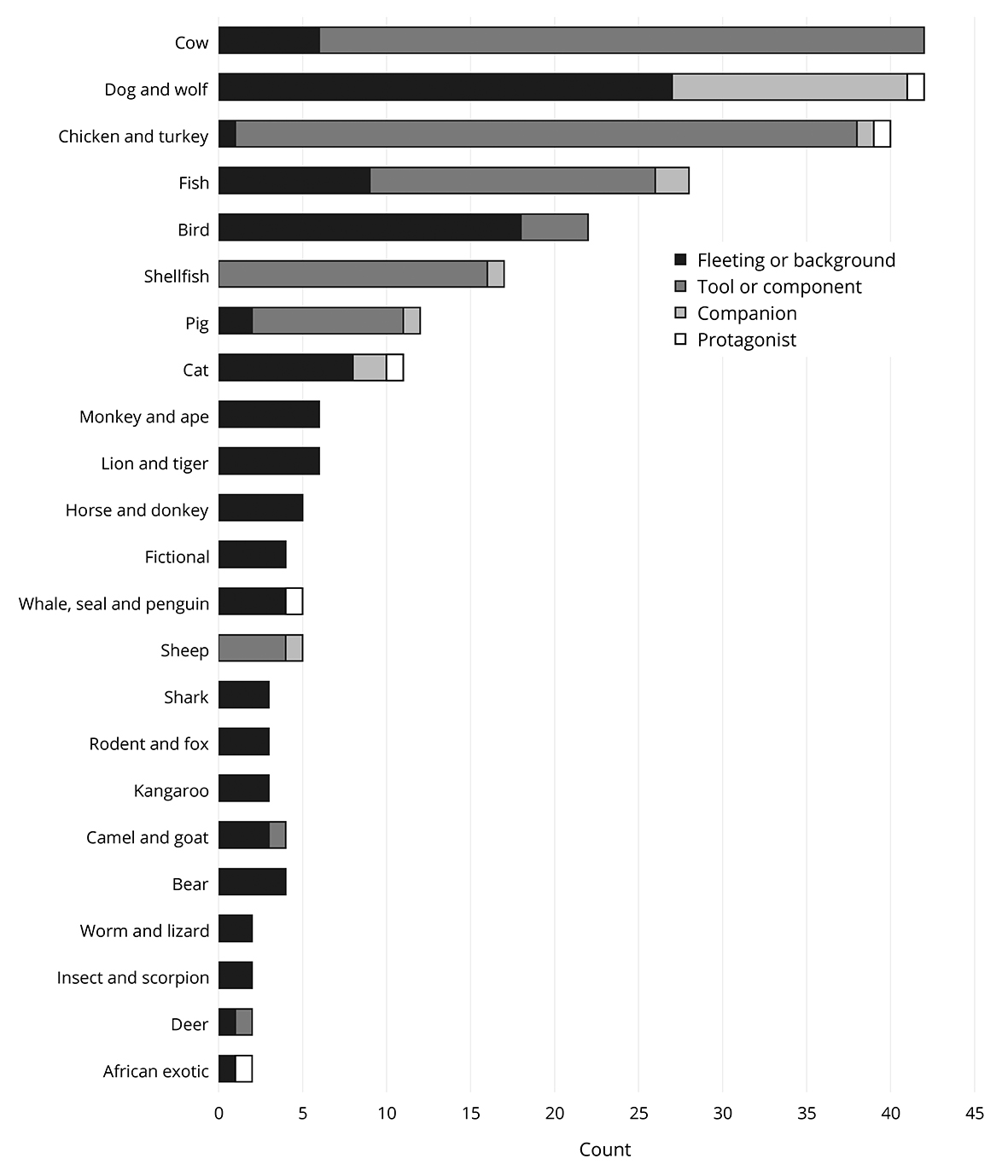

Given the diversity of animals in nature, only a very narrow band of animals appears frequently on television.11 Reflecting and reinforcing the anthropocentric attitudes identified in Chapter 3, the animals most often seen on television are those used as food, followed by companion animals: cows, dogs, chickens, fish and other birds. What is also interesting is the comparative absence from our screens of pest animals (collapsed into the ‘other’ category given their scarcity in the dataset), and of native animal species, which appeared almost exclusively in tourism and travel advertising. The latter is not an artefact of the inclusion of non-Australian content; television advertising in Australia is almost completely produced domestically.

The dominance of food and industrial animals (including animals used for service, transport and entertainment) in the sample is partially explained by examining which types of programming are most likely to feature animals on Australian prime-time television: most animal appearances are in advertisements. This is consistent with the idea already articulated that advertisements are likely to use animals as signifiers to maximise their bandwidth (Pieters et al. 2010). The preponderance of animals as products (and in products) goes some way to explaining their frequent appearance in television commercials. One example is typical. In an advertisement for a national supermarket chain, the viewer follows a protagonist through a series of vignettes depicting food consumption and preparation, all of which feature animal products as a key ingredient. The journey leads the viewer back to an idealised farm and farmer. In this advertisement, the number of different elements and scenes, and the overarching narrative (namely that quality products are supplied to happy customers as a result of a partnership between retail and production), could be said to be as complex as the surrounding programs.

In addition to the simple representation of animals as products to be consumed, the dataset also included examples of animals being used as more complex signifiers. Advertisements use visual cues to signal meanings and values to the audience without having to make these connections explicit (Lloyd and Woodside 2013, 14). Companion animals often play this role in advertisements. Where they are not advertising products specifically for companion animals (such as pet food), these animals may be employed to signify the security of home and family. In familial settings, often alongside children, dogs are commonly used to represent the happy, clean and modern home. Threats to the home may be signified by unhappy or at-risk pests (as seen in a series of insurance advertisements featuring claymation dogs and cats).12

Figure 4.4. Animals on Australian free-to air television, billing or characterisation.

Outside of advertising, the second most common category of television content to feature animals is cooking and lifestyle shows.13 In these shows most animals appear as ingredients (Figure 4.4), rather than as live animals. Meat tends to feature as the dominant or most valued ingredient in these programs, with vegetables secondary in significance. Demonstrating the influence of ‘foodie’ movements on popular culture, the quality of the animal ingredient is sometimes highlighted (either directly, through appeals to the audience to use quality ingredients, or by describing the meat using adjectives that convey quality). When companion animals appear in these shows, they tend to provide background scenery (happy homes again); occasionally they take a more central role, for example as the subjects of veterinary treatment (one lifestyle program in the sample included an extended segment about pet psychology and fear management). Overall, however, as we can see in Figure 4.4, animals are nearly never depicted as demonstrating significant agency relative to people; they are very rarely protagonists or antagonists.

Turning from average representations, let us now examine how popular culture presents atypical diets to the general community, by drawing on separate case material selected for this purpose. Using a selection of episodes of the long-running cooking programs MasterChef Australia (FremantleMedia Australia 2009–2011; Shine 2012–) and My Kitchen Rules (MKR; Seven Network 2010–), we can examine the representation of veg*n meals. MasterChef and MKR are useful examples for a number of reasons. First, although it has spawned a range of imitators and competitors, MasterChef set the standard for competitive prime-time cooking shows. Both shows have rated extremely highly in their timeslots for many years. And, both programs’ content is directly influenced by commercial tie-ins with advertisers and in-show promotions. They are thus calibrated strongly towards a mainstream audience. Finally, MasterChef and MKR have tended to set the agenda for other media: their content, contests, and personalities have been closely reported and discussed in the wider media.

In season two of MasterChef (2010), contestants were faced with an ‘invention test’: as a special challenge, they were to prepare a vegetarian meal (episode 42). Demonstrating that gendered perceptions of meat consumption continue to hold sway in Australia, the challenge was judged by ‘six of the most meat-loving men in Australia’ (a cattle farmer, two builders, two truck drivers and a firefighter). The episode reiterated the conventional association between meat, muscle and labour, with one of the guest judges observing that he considered it ‘hard to work eight or nine hours on the tools with a stomach full of broccoli’. Here the distinction between the guest judges – working class and uniformly white – and the show’s contestants – mostly urban professionals of both genders, including some visible minorities; of the 24 finalists, only three worked in a trade – was put into sharp relief. Five years later, a similar challenge on MKR did not appear to need the same conceit: three pairs of contestants made vegetarian meals and were assessed by the regular judges, in a format no different from most of the show’s challenges (season six, 2015, episode 40). In this episode, the major challenge was the use of specific ingredients, rather than the absence of meat.

The gendering of meat consumption and vegetarianism was still visible in MKR, however. In season four (2013), teams were set the challenge of cooking for the public in a series of themed street-food vans, one of which was vegetarian (episode 39). Teams had to compete for customers with their respective offerings. After failing to entice a group of male customers away from the vegetarian van with the promise of meat, one competitor, a young woman, exclaimed, ‘Boring! There are grown men wanting a veggie burger over a steak.’ Interestingly, the episode uncovered a high demand for the vegetarian option among customers in the Sydney CBD, a phenomenon mentioned several times by the contestants. The contestants, uniformly omnivorous, recognised the increasing prevalence of abstainer diets, an increase consistent with the findings in Chapter 3. This gap between the public and the competitors is to some extent a structural feature of these programs: because they require contestants to cook omnivorous meals if they are to compete effectively, the shows rarely feature contestants with non-mainstream diets. (Season six of MasterChef, in 2014, did include an advocate of veg*n cooking, Renae Smith, who remained in the running until the last month of broadcasting; although she cooked meat during the competition, she was vocal in her support of veg*n food. The show has also featured several ‘former vegetarians’ as contestants, who have discussed this as part of their show persona.)

Demonstrating this tendency to sequester veg*n meals, in season three (2011; episode 46) of MasterChef, contestants were required, in pairs, to cook for people with special dietary requirements. Two of the pairs were set the challenge of cooking a vegan meal; they were in competition against others cooking for people on low-salt, low-fat, low-sugar and low-gluten diets. Veganism was presented as one of a number of dietary restrictions that chefs may encounter in their normal work. The show’s producers did not feel the need to explain veganism to the audience, suggesting that they felt confident viewers would be familiar with the term; veganism’s connection to animal rights was not discussed. Interestingly, the teams set other challenges (such as restrictions of salt and fat) were portrayed as struggling more than those assigned vegan meals.

While these programs certainly present veg*n cooking as outside the mainstream of Australian cultural life, the reception of the contestants’ veg*n meals by the public via the use of in-show competitions and challenges and by the judges was largely positive, and involved a wider range of dishes than simply those that might be described as simulacra of meat-based meals.14 This appears to demonstrate the popular attitudes towards vegetarian food identified in Chapter 3: the diet may be widely considered non-mainstream and, in Australia, considered not masculine, but it is not generally seen as deviant and its market share is not trivial.

Animals online

During the last decade the uptake of broadband and mobile internet services has dramatically reshaped the Australian media landscape, with rapid increases in the amount of time Australians are spending online (Chen 2013, 8). Thus, in considering the representation of animals in popular media and how the public use media to access information about animals, the online habits of Australians are relevant: are they similar or different to other media consumption habits?

To examine this question we can map what Australians explicitly look for on the internet by using Google search data from the same period as covered by our newspaper content analysis. Search data is useful and telling because, unlike the comparatively passive connection between television content and consumer interests, search provides specific and quantifiable evidence of what the public are actively interested in. In this case Google is a good indicator of general trends in search behaviour in Australia, as the site has had an extremely high market share (over 90 percent of all searches) for a considerable period of time in this country (Cowling 2010; Cowling 2012; AFP and Bloomberg 2015). This data provides a picture of animal searches over the period 2005–2014 (inclusive), and reveals that the same two ‘privileged’ groups of animals are the most frequently searched for: companion animals and food animals. Thus, the most frequently searched-for animal aggregated terms for the decade were (in descending order): dog/puppy, chicken/bird, fish, pig/pork/bacon, horse, cat/kitten, beef/cow/cattle, and lamb/sheep/mutton.

Remarkably, the list of the most commonly searched-for animals is almost identical to the list of animals most commonly represented on television. Of the top eight searches for animals (which comprise the majority of all searches for animals), seven also appear in the equivalent list for television. Digging further into this data, we can see that the search context (the broader interest or motivation for the search, if it can be ascertained) often has similarities with how animals are displayed on popular television. For example, we can see that searches for dogs tend to focus on pet-related information, while searches for food animals tend to focus on recipes (a list of related search terms is provided in Appendix G). This confirms the idea, already established above, that animals are given chiefly instrumental and anthropocentric meanings in popular media.

Examination of the search data does reveal some differences with television content. The first is the comparatively high level of searches for horses, usually in the context of recreational activities (whether riding or racing). Horses are the fifth most popular animal in the search data, but only the 11th most commonly depicted animal on television. The second is the frequency of Google searches for ‘wild’ and ‘pest’ animals, which tend to be largely invisible on Australian television. Searches for sharks, for example, tend to spike in the context of recent attacks or sightings in populated areas. (The appearance of spiders in the data, meanwhile, seems to be an artefact, reflecting interest in the popular superhero rather than the animal.)

Animals and farmers ‘in real life’

While the media is an important source of imagery and information about animals and animal production, Australia’s highly urban population also encounter non-companion animals directly, through recreation and tourism (undertaking over 30 million day or overnight visits per annum; Moyle et al., 2015). Physical exposure to production animals, on the other hand, is most commonly seen in highly stylised urban contexts: in supermarkets, and in agricultural shows, by which the ‘country comes to the town’.15

A stroll down the aisle

Of Australia’s 14 million shoppers, 12 million visit a supermarket at least once per week (Langley and Hogan 2015), with the top two chains controlling 72.5 percent of market share (Roy Morgan Research 2014b). As Elliott (2012, 302) observes, supermarkets are where most food choices occur. Product packaging is therefore another important and pervasive source of information about animal products and production processes. Often, packaging uses symbolism to convey information or impressions about the product and its origins (Maher 2012, 502–3). Using a content analysis of the packaging seen on supermarket shelves,16 we can identify the most common representations of animals and, importantly, of farming. Given the scarcity of depictions of farmers and farming in electronic media, the latter is particularly interesting.

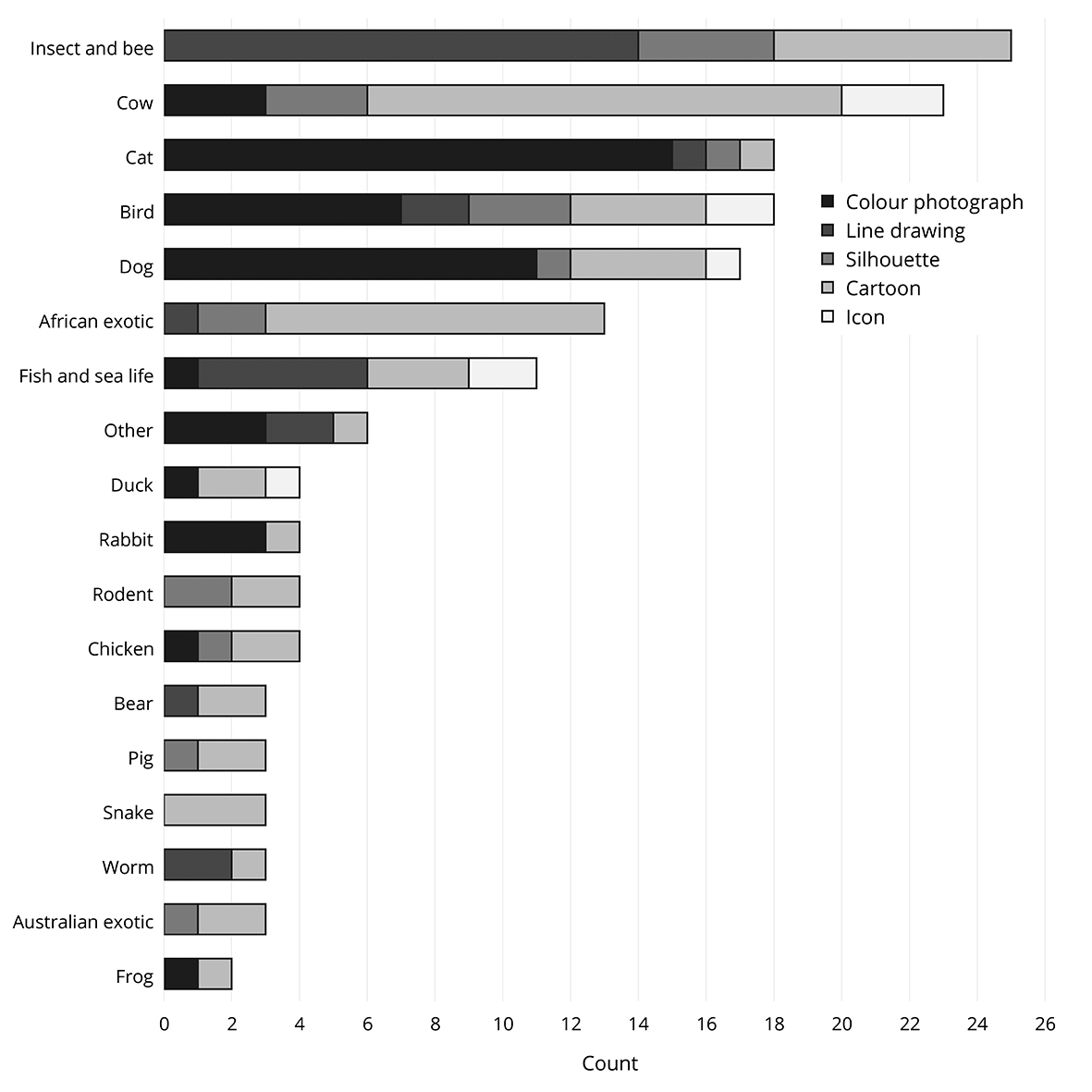

Figure 4.5. Representations of animals on Australian supermarket shelves. Compound categories use the same more common/least common convention.

Looking first at how animals17 are represented on product packaging in supermarkets, Figure 4.5 shows some continuity with the anthropocentric selection of animals seen in television and in Google searches (that is, there is a focus on companion animals and food animals). But there are important differences. Pest animals (particularly insects and rodents) finally make a significant appearance, as do birds other than chickens (often playing a role as brand identifiers, or on bird-food packaging). Only two product categories regularly feature animals or farming-related images on their packaging: household traps and poisons, and pet food and pet accessories (Table 4.1). Interestingly, and in line with previous evidence about how Australians engage in cognitive avoidance of animals as we get closer to their consumption (Chapter 3), animals whom we intend to eat or kill (either as food or as pests) are more likely to be depicted in abstract representational forms on product packaging than in a realistic manner. Thus, in Figure 4.5 we can see not only the type of animals represented on supermarket shelves, but their progression away from lifelike images, moving along a scale of abstraction from photographs (least abstract) to icons (most abstract).

| Product category | Percentage including animals on packaging |

|---|---|

| Poison or household cleaner | 21.5 |

| Pet food or pet product | 21.5 |

| Dairy or eggs | 12.8 |

| Meat (fresh or canned) | 9.2 |

| Sweets and biscuits | 9.2 |

| Beverages (including tea and coffee) | 4.6 |

| Fruit and vegetables (packaged) | 4.1 |

| Body or beauty | 3.5 |

| Cooking oils | 3.0 |

| Cereals and breakfast foods | 2.5 |

| Misc. ingredients | 2.5 |

| Pre-packaged complete meals | 2.0 |

| Baby or infant products | 1.5 |

| Other | 1.5 |

Table 4.1. Categories of supermarket products employing animal or farm imagery on their packaging.

Interestingly, animals are almost completely absent from the packaging of meat products, with the exception of fish. (Fish products for both human and animal consumption commonly feature illustrations or photographs of fish. As previously noted, fish purchased from fishmongers is one of the few meat products purchased whole and served in recognisable form.) Apart from fish, most meat sold in supermarkets has little in the way of imagery on its packaging, with producers electing for clear film instead. Only a very small subset of meat included images of any kind. The most common animal imagery on meat packaging were the animal silhouettes featured on RSPCA-approved meat products; the second most common were pastoral scenes. In the latter category, photographs of pasture were devoid of the animals contained in the product: they featured empty landscapes, referring only implicitly to the animal contained therein.

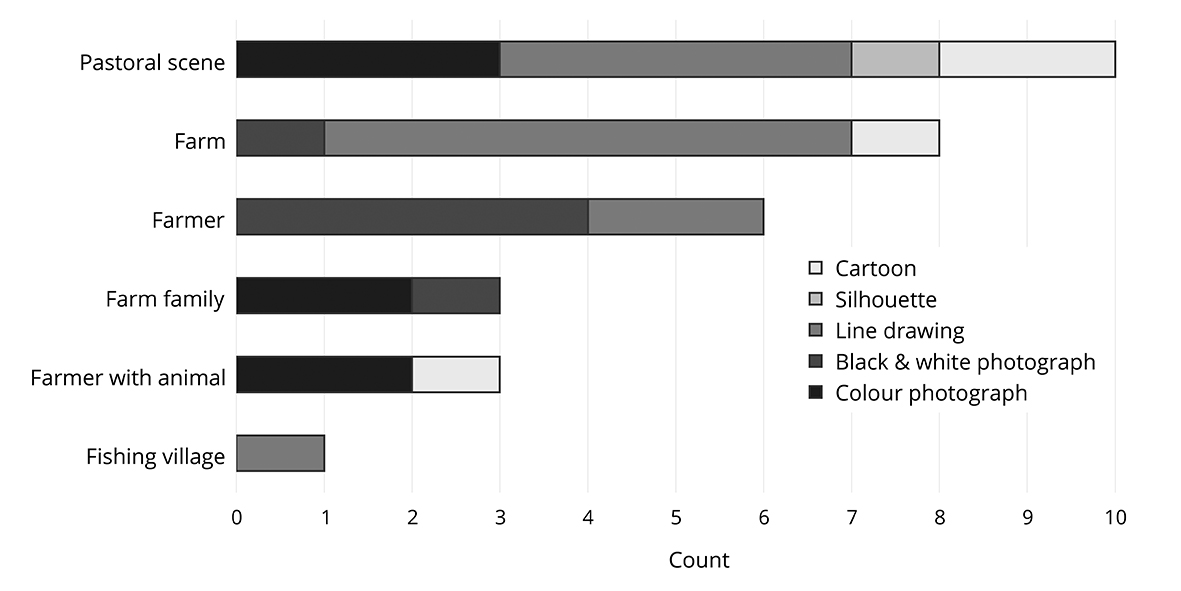

Turning to representations of farmers and farming on food packaging, Figure 4.6 provides a breakdown. We can see that representations of farms are dominated by pastoral scenes, with farms commonly signified by barns or old-fashioned windmills. These representations are less stylised than the depictions of animals in Figure 4.5, and are more likely to be photographic. Yet most images of farms are still hardly lifelike: they tend to take the form of idealised or archaic portrayals, rather than realistic representations of modern production facilities. This carries over, to some extent, into images of farmers themselves: this is the only category where large numbers of black and white photographs are used. Farmers are depicted as individuals (predominantly men) or as part of ‘farm families’, avoiding the reality that farms in Australia today comprise large agribusiness enterprises as well as family owned and operated properties. Interestingly, farmers are rarely shown with farm animals. Overall, in the symbolic language of the Australian supermarket, farmers and farms are depicted as clean, largely free of animals, and somewhat quaint.

Figure 4.6. Representations of farmers and farming on Australian supermarket shelves.

Farmers and farming on display

These abstract and unreal representations can have a spiralling effect, further reproducing accepted social norms and expectations (Noelle-Neumann 1984). For some involved in animal industry, this is part of a virtual ‘fight to the death’ over the ideological and cultural image of animal agriculture. The Hon. Robert Brown MLC, a member of the NSW upper house for the Shooters and Fishers Party, observed the ‘cleansing’ of agricultural shows:

This is how bad it is. Must be probably about 20 years ago now, the Royal Agricultural Society decided because of community pressure that they would not any longer exhibit carcasses. You know how they used to hang carcasses and grade the carcasses . . . They don’t do that anymore; you only see live animals. So, you march your bull around the ring, and the bull gets the [ribbon], but the meat industry no longer gets to hang carcasses and have [a] first-place carcass. (Interview: 18 March 2014)

For Brown, this continues a process whereby the expectations of an increasingly sheltered urban community encourage the further sanitation of representations of farming practices. Popular understanding of the realities of animal agriculture become increasingly distorted over time. Animal advocates, however, cite these agricultural shows as an example of the deliberate concealment of agricultural practices by the industry itself, which is aware that its practices are no longer popularly accepted (Ellis 2013, 361–2).

While the exact process that drives this self-representation by agricultural industries and individuals can be debated, it is certainly true that the urban agricultural shows have become far more sanitised than they were in the past. Taking the example of the 2015 Brisbane agricultural show (‘the Ekka’) it is clear that, while agricultural and other animal demonstrations (including pet shows) still occupy most of the physical space allocated to participants,18 there has been a Disneyfication of representations of animal use at these events (Bryman 2004, 2). While some animal production practices are still on display, they are limited to ‘harvesting’ activities (such as shearing and milking). Food animals such as cattle and goats are displayed, but with little or no reference to meat production, while juveniles (including chicks, calves and piglets) are provided for handling and patting (Images 2, 3). Throughout, there is a heightened emphasis on animals’ cuteness, both in the imagery on display and in the ways participants are encouraged to interact with animals. At the 2015 show, education about animal slaughter was limited to a small display in the Beef Pavilion, including a ‘Carcase to Cuts’ diagram of the various meat cuts (Image 1). Discussions of animal welfare at agricultural shows tend to focus on the ‘good husbandry is good welfare’ model discussed in previous chapters. For example, at the same 2015 Brisbane show, the presenter of a milking display emphasised the need for dairy cattle to be free of stress in order to produce milk effectively. Another display in the Beef Pavilion provided brief information about the welfare and environmental aspects of cattle farming, apparently aimed at children.

This sanitised and hyper-real version of farming is also identified by O’Sullivan (2011) in her discussion of the Sydney Royal Easter Show. Importantly, linking back to the Habermasian ideal of spaces that provide opportunities for policy-related debate, her interpretation of the show space highlights the absence of the most contested animal-use practices from public display. From a democratic-idealist perspective, this undermines dialogue about those practices: it removes an opportunity for defenders of the status quo to argue for its necessity, or for opponents of contemporary farm practice to challenge them.

Counter-narratives

So far we have examined popular and mainstream representations of animals, farming and abstention. These depictions provide the cultural context in which policy-making generally occurs. Just as political activism challenges legal norms, however, this mainstream vocabulary of animal use does not go unchallenged by abstainers. Abstainers who are motivated by ethical reasons do not seek only to reduce the quantity of animals used and consumed by humans; they also present a challenge to the cultural and linguistic status quo. Where the general public have an anthropocentric and egocentric attitude to animals, through the propagande par le fait (the ‘propaganda of the deed’), this group demonstrates a willingness and capacity to live as non-conformists. Members of the veg*n community are not just a notable sub-public; some can also be said to form a ‘counter-public’.

The term ‘counter-public’ was first proposed by Fraser (1990), with particular emphasis on repressed or oppressed groups within the body politic. These groups differ from other sub-publics in the way they threaten and/or challenge dominant cultural and political norms. Counter-publics form and sustain their own distinctive discursive communities, developing group awareness and affinity, and producing and distributing discourses about themselves and their relationship with the wider community and its norms. By naming the unnamed and presenting alternative social and political theories, they can present a competing view of reality and so undermine dominant norms. In presenting alternatives to the everyday social order, counter-publics can develop and propagate what Warner (2010, 119) calls a ‘special idiom for social reality’: a language for social critique and for the reformulation of social power relations.

This can be overstated, of course. There are often debates within these communities as to the extent that membership entails a moral imperative to proselytise and to uphold the political values of the wider group (often expressed as the notion of ‘being a good veg*n’; interview: individuals associated with the Sydney veg*n community, 8 May 2014), and the extent to which members actively promote their alternative viewpoint varies within and between groups. From an ethnographic study of Australian freegans, for example, Edwards and Mercer (2013, 184) found that this subset of the veg*n community tends not to promote their waste-minimisation practices in the same way as their US counterparts do. They might practise the same dietary lifestyle, but reflect different local political characteristics. Australian vegetarians and vegans, on the other hand, have a long history of actively proselytising, in both the first (19th century) and second (1970s onwards) waves of these movements (the Anti-Vivisection Union of Australia was actively engaged in the promotion of ethical veganism as early as 1978; AVUA 1978, 5). Such dietary alternatives have a longer history in Australia than is often recognised.

Alternatives to the mainstream

This production of counter-hegemonic messages takes a variety of forms, including criticism of conventional practices and the promotion of alternative representations of them (for example, using the term ‘factory farms’ rather than ‘agribusiness’, or the phrase ‘happy meat’ to mock claims of improved animal welfare standards by meat producers). To some extent, these groups are increasingly adopting a transnational identity and language. However, while they do often promote internationally sourced content, the Australian veg*n counter-public also has a long history of producing its own material. This includes:

- information about community events, products and services

- educational or outreach material, encouraging the adoption of, and adherence to, veg*n diets (including recipes, dietary and health advice)

- information about the veg*n community itself (as seen in the market research commissioned by the Vegetarian/Vegan Society of Queensland, research employed extensively in Chapter 3)

- adaptations of international material for local purposes; and

- uniquely Australian content about local issues and concerns.

This variety of material speaks to an increasingly wide range of audiences. One interesting recent example is Marston’s (2014) Leo escapes from the lab, an illustrated children’s book that describes the experience of a cat used for invasive scientific research, his eventual adoption, his ongoing post-traumatic fears, and his hope for a world without animal experimentation. Produced by an anti-experimentation advocacy organisation, this volume is interesting for its willingness to directly engage with children. The publication of popular political fiction by activists has strong parallels with the first era of vegetarianism in Australia, such as Hudson’s 1914 novella The red road: a story by a roan bullock on the wrongs suffered by animals at the hand of man.

While established veg*n organisations still actively sell domestically produced books that are unlikely to be stocked by commercial bookstores (although cookbooks may have the potential to cross over into the popular marketplace), the internet has seen a significant shift towards online communication and a fall in demand for print publications (interview: M. Collier, 17 April 2013). Thus, for example, while the VVSQ still maintains a DVD-lending library, newer organisations have tended to focus on the online space. Vegetarian Victoria (vegvic.org.au) is an early example of an organisation with an extensive online presence, distributing dietary and shopping information on its website since its formation in 1998. The site today includes social media and extensive curated video content (‘VegTube’). The more recently established Vegan Australia (veganaustralia.org.au, founded in 2012) has similarly focused on a web-only communication strategy, providing a national list of events in addition to its advocacy work (interview: Greg McFarlane, Chair, Vegan Australia/Vegan Society of NSW, 17 May 2013). Each organisation combines outreach and service activities.

Some parts of the veg*n community retain their ‘outsider’ status through the active use of alternative and subversive media. Freedom of species, an animal advocacy radio program and podcast, is produced in Melbourne at the community radio station 3CR (www.freedomofspecies.org); it combines activist discussion and academic interviews. Another animal studies podcast, Knowing animals, is produced by Dr Siobhan O’Sullivan of the University of New South Wales (knowinganimals.libsyn.com). Veg*n graffiti, meanwhile, puts the message directly in front of the wider community and is used both to promote veg*n dietary practices or to publicise related media. That this type of guerrilla marketing challenges social norms is evidenced by the frequent presence of counter-messaging on these graffiti (in Image 7 and 8, ‘Fuck up’ and ‘Stop forcing your opinion on everyone else you vegan fuck wits!’).

Bonding and sustaining

‘Vegan fuck wits’ may thus not feel as accepted by the broader community as the evidence presented in Chapter 3 might suggest (Table 3.18). This can also be seen in the discursive practices commonly employed by and within the veg*n community, which can be both inclusive and defensive. This demonstrates the other important aspect of Fraser’s notion of counter-publics. In addition to challenging social norms, they can serve as ‘spaces of withdrawal and regroupment’ where the community can develop its capacity to resist rhetorical assault from the mainstream. An Australian example of this is Waddell’s (2004) book But you kill ants: answers to 100 objections to vegetarianism and veganism. A not-for-profit publication, the book provides a set of clear, canned responses to common concerns and objections that veg*ns may encounter. Similar combinations of the informative and the defensive are common in outreach and educational literature. These publications tend to synthesise a wide range of materials, from medical information (such as questions about protein and calcium deficiency) to summations of animal rights philosophy. This reflects Louw’s (2010, 131–5) argument that successful popularisation of alternative worldviews involves a ‘two-tiered intelligentsia system’: an interaction between a scholarly or intellectual group that generates the theoretical elements of the worldview, and popular communicators who translate these conceptual arguments for a wider audience. Vegan Australia, for example, clearly identifies its mission as one of popularisation: it aims to be a ‘focused, media-aware organisation dedicated to getting the vegan message out there for the sake of animals, people and our planet’ (Vegan Australia n.d.). Individuals such as the Fairfax columnist Sam de Brito (2014), who was a vegan, may use their public profiles to talk about their own dietary choices and about animal welfare issues. Given the conventional associations between meat eating and manhood discussed above, de Brito is particularly interesting, as he was also strongly associated with writing about – and personifying – contemporary Australian masculinity.19

Communities based on alternative diets are not united only by defensiveness. The service work of veg*n organisations also creates social cohesion. Veg*n community organisations run social events (frequently meals, which account for 32 percent of national events in a given year), activist events (including talks, outreach activities, political activism and organisational meetings; 31 percent), and instructional activities (such as cooking classes and expos or fairs; 31 percent). Some of these activities are aimed at internal ‘bonding’ within the community; others focus on ‘bridging’: building links to the wider community. To use the language of social capital, such social networks generate trust and reciprocity (Field 2003, 5). As Bandura (1997) has observed, communal investment in building internal social capital and cohesion can improve the group’s ability to take effective collective action.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have examined representations of animals, farming and non-mainstream diets in the Australian mainstream media. This provides the cultural context in which policy-making occurs; it reflects the social norms of a society that is dominated by people who routinely consume and use animals. In reviewing media representations of animals, farming and alternative dietary choices, we can see the origins of popular attitudes towards animals discussed in Chapter 3. While the media landscape has expanded in recent years, it is still strikingly narrow where depictions of animals are concerned. The media act as a kind of feedback loop: animals of interest to humans as prey or as pets dominate the media landscape, but they do so largely as shades: they appear as fleeting background images, or as stylised representations of the real. Farms and farmers fare little better; caught in a permanent nostalgia, they appear in black and white or in theme-park-like fantasies. Such depictions reinforce the moral status quo, but can only do so thanks to popular ignorance about the realities of animal use and farm life. In the media’s distorted mirror of the world, consumers see what they want to see. When challenges to this sanitised view pop that bubble, the public may be shocked and angry – but without a strong base of knowledge, this anger tends to remain unfocused and can be quickly sated.

For policy-makers, this presents a complex challenge: if public interest is shallow and can easily be driven by media campaigns, animal protection issues run the risk of breaking out like bushfires. Public outrage is unpredictable, fast moving, but also quickly extinguished. With low levels of consistent community concern, political elites may feel they lack a popular mandate to address even widely known welfare problems in the face of organisational interests who may be resistant to change, or who may themselves lack the capacity to control their own stakeholders. This suggests a policy domain, therefore, that is not structured around the interests and concerns of policy-makers to ensure orderly policy development. This may result from a failure to engage in the work of agenda building, or from the fact that policy-makers are seldom the central actors in the policy domain. In Chapter 5, therefore, we will map out the animal protection policy domain in Australia.

1 In two senses: that the issue is newsworthy enough for it to be reported, and that the audience either engage, or fail to actively disengage with, coverage. The latter notion – active disengagement – is related to the concept of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957), where audiences actively avoid media content because it is objectionable in some way.

2 Tasmanian-specific issues, for example, receive more than three times the level of coverage of Western Australian-specific issues in the time period. Per capita, Queensland is also significantly over-reported.

3 The reporting of cruelty offences against dogs tends to be related to an owner or carer, while cat cases tend to be associated with seemingly random attacks against ranging animals. It is difficult to determine if reported attacks against cats focus more on domestic or stray animals.

4 Rural and regional areas see a greater level of reporting (though still a low level overall) of cruelty acts against native animals. Often these are associated with illegal or botched hunting (for example, the discovery of live animals with arrows in them).

5 This may be a long-established reporting convention in Australia. Newspaper reports from the 19th century similarly resulted from policing actions. Interestingly, a number of these reports focus on prosecutions made for veterinary procedures police deemed inappropriate (see, for example, Age, 20 November 1864, and Sydney Morning Herald, 14 November 1865).

6 Kelvin Thomson argues that the issue mobilised both urban and rural constituencies, whereas Steve Whan MLC (interview, 19 June 2014) argues that this was not the case and that concern remained contained to urban areas.

7 A good example of another instrument that received some attention during the decade was the establishment of a register of cruelty convictions, created with the objective of monitoring individuals with major anti-social tendencies.

8 Katie Hopkins, writing in the UK tabloid newspaper the Sun, in response to migrant deaths in the Mediterranean in April 2015.

9 This was highlighted at the Geneva Roundtable in May 2011 by UNHCR and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

10 https://www.partyforfreedom.org.au/policies/. Folkes (2015) did, however, highlight animal welfare issues in an email sent to supporters to promote the event. There is an established connection between far-right groups and animal welfare. It is often noted that the National Socialist government of Germany (1933–1945) had some of the most extensive animal protection laws of its time. As Bruns (2014, 40) observes, these laws were also used to demonstrate the moral superiority of Germans to ‘Jewish-materialistic’ medical practices such as the increasingly popular use of vivisection by scientists. In Australia today the far-right appears on both ‘sides’ of this issue. In 2015 the neo-Nazi United Patriots Front found themselves in opposition to animal liberationists over the latter’s plan to protest against a circus (Belot and Inman 2015).

11 For the purposes of this study, an ‘appearance’ was defined as the distinct representation of an animal, in whole or in part, in a television program or advertisement. There was no attempt to measure the length of time on air (the random sample, however, included no cases where animals were protagonists). Animals included were live, dead, and animated representations, but animals as stylised logos were excluded.

12 This may be the result of broadcasters’ codes that limit their use of messages that generate fear. The 2015 Free TV Australia Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice states that General Classification content should ensure that ‘Where music, special effects and camera work are used to create an atmosphere of tension or fear, care must be taken to minimise distress to children’. Thus in the insurance advertisement, rather than depict a human at risk from a storm, a cat is blown away by the strong winds. This demonstrates that pets are considered family members, but with a lower status than human family members, as identified in Chapter 3.

13 The former being more common in the sample than the latter, but each sharing many similar thematic and visual elements.

14 MasterChef (season two, episode 42) featured one dish described as ‘vegetarian shepherd’s pie’ and MKR (season six, episode 40) a veggie burger, but the majority of meals were not simply veg*nised versions of conventional meat-based recipes.

15 For a broader and deeper discussion of animals in the contemporary human environment, see O’Sullivan (2011).

16 Drawing on Moskowitz et al.’s (2009, 54) characterisation of the content analysis of packaging, this is an explicitly external product analysis aimed at assessing the range of content as seen in situ, as opposed to a complete, detailed analysis of single product items.

17 In this study, as opposed to that of the analysis of television content, animal parts were excluded from classification, in order to look at the connection between animals as products and animal representations in the context where purchasing occurs.

18 Including the Community Arena (chiefly used for the display of large animals such as horses and cattle), the display and housing of animals occupied approximately 60 percent of the space in 2015.

19 de Brito (1969–2015) died during the writing of this volume.