Introduction

‘To tilt at windmills’ is a venerable English idiom meaning to pursue an unrealistic, impractical, or impossible goal, or to battle imaginary enemies. In current usage, ‘tilting at windmills’ carries connotations of engaging in a noble but unrealistic (usually wildly unrealistic) effort, an endeavour which may garner the admiration of onlookers but which usually strikes other people as delusional.—The Word Detective1

The introduction of new technology has a long history of being accompanied by beliefs that take root among small proportions of the population who believe that rapidly proliferating inventions are silently eroding people’s health. Railway travel and electric light were early villains to those who saw such developments as Mephistophelian artifice that could bring only harm to communities and society. At the advent of electric light in the late 19th century, the belief was common that the night was divinely ordained to be dark. For some, artificially lighting up the darkness was a profanity that was likely to reap hubris.

Historian Linda Simon in her book Dark light: electricity and anxiety from the telegraph to the X-ray, notes that although the discovery of electricity generated excitement and electrical companies worked hard to build the market for electrical power:

more than thirty years after Thomas Edison invented the incandescent bulb in 1879 and soon afterwards installed a lighting system in a business section of lower Manhattan, barely 10 per cent of American homes were wired. Even after the First World War that percentage rose only to 20 per cent.2

One reason for this was that community concerns about the safety of electricity were widespread. The electrical companies ran advertising as late as 1923 assuring the public that ‘electric light is safe’. Simon notes that ‘Newspapers frequently reported electrical fires and accidental electrocutions, and magazines offered long lists of cautions for those who dared to install electricity’.3 Some worried about going blind from reading by electric light. On 10 May 1889, Science noted:

A new disease, called photo-electric opthalmia, is described as due to the continual action of the electric light on the eyes. The patient is awakened in the night by severe pain around the eye, accompanied by an excessive secretion of tears.4

On 24 September in the same year, the British Medical Journal carried a report that the newly popular telephone could cause ‘telephone tinnitus’, claiming that victims ‘suffered from nervous excitability, with buzzing noises in the ear, giddiness, and neuralgic pains’. The article contextualised the perils of these new contraptions:

As civilization advances, new diseases are not only discovered, but are actually produced by the novel agencies which are brought to bear on man’s body and mind … almost every addition which science makes to the convenience of the majority seems to bring with it some new forms of suffering to the few. Railway travelling has its amari aliquid in the shape of slight but possibly not unimportant jolting of the nervous centres; the electric light has already created a special form of opthalmia; and now we have the telephone indicted as a cause of ear troubles, which react on the spirits, and indirectly on general health.

M Gellé has observed, not in women only, but in strong-minded and able-bodied men, symptoms of what we may call ‘aural overpressure’ caused by the condition of almost constant strain of the auditory apparatus, in which persons who use the telephone much have to spend a considerable portion of each working day. In some cases, also, the ear seemed to be irritated, by the constantly recurring sharp tinkle of the bell, or by the nearness of the sounds conveyed through the tube, into a state of over sensitiveness which made it intolerant of sound, as the eye, when inflamed or irritable, becomes unable to bear the light.5

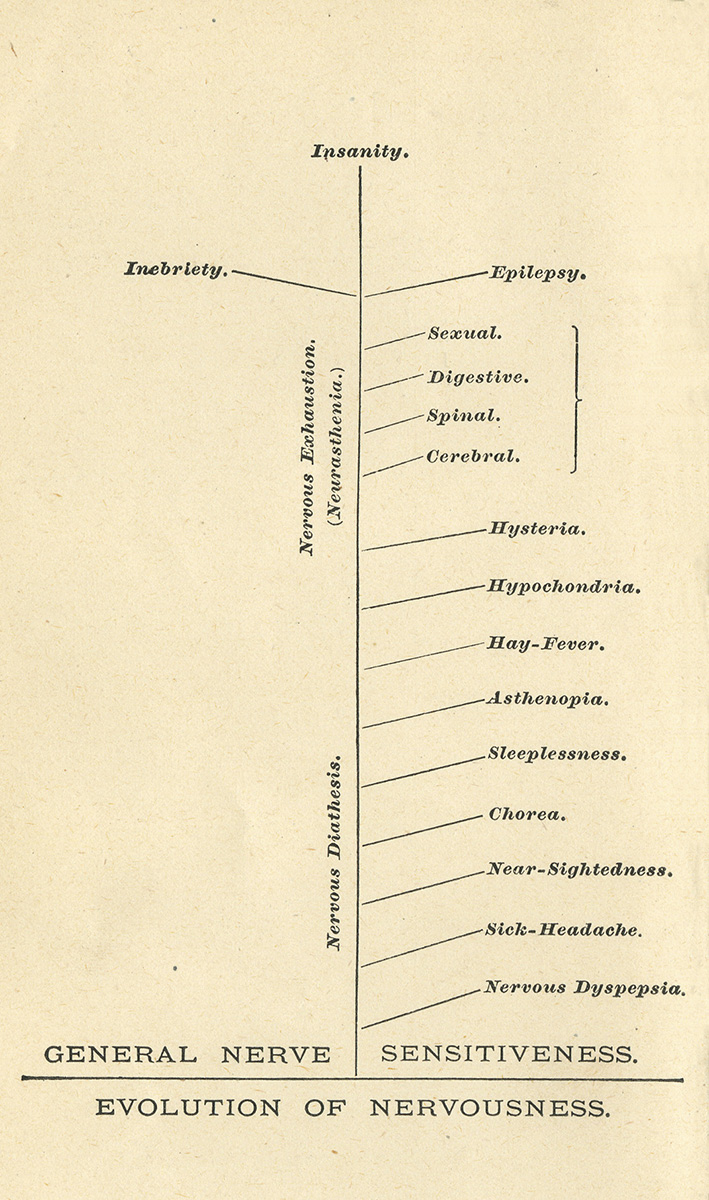

George Miller Beard was a prominent US neurologist who from around 1869 began promoting the diagnosis of ‘neurasthenia’ in his prolific clinical writings and books. His central thesis was that modern living and the pace of life among the well-to-do was causing a proliferation in a range of progressive symptoms shown in Figure i.1.

In what today reads like the quintessence of sexist ideology permeating clinical guidelines, the recommended treatment for women suffering from neurasthenia was the rest cure. This consisted of: ‘Undisturbed seclusion from children, family members, and friends combined with … uplifting literature and light exercise.’ Women were thought to be:

particularly sensitive to the draining effects of strenuous mental effort, the dangers from which the Rest Cure protected them. Those with the worst cases were prescribed complete bed rest for six to eight weeks in dim rooms with only soothing activities, sometimes excluding books or substantive conversations.6

Men, being made of sterner stuff, were prescribed ‘vigorous, even strenuous exercise in natural areas away from the pernicious influences of modern life.’ They were ordered to travel to remote areas, such as the cattle ranches of the American west or the European Alps.

Among the causes of all this nervousness, Beard included several new-fangled inventions: ‘wireless telegraphy, science, steam power, newspapers and the education of women; in other words modern civilization’.

In the years since, power lines, televisions, electric blankets, hair dryers and washing machines, microwave ovens, computer screens, mobile phones and transmission towers, and, most recently, wi-fi, smart electricity meters, LED light bulbs and even solar electricity roofing panels are examples of new technologies where claims of potential calamitous consequences – typically ‘cancer’, but sometimes problems of biblical plague proportions – have been megaphoned by activist groups opposed to them.7 Typically, these waves of anxiety arise in a very small proportion of the population, are promoted by electro-phobic groups (these days online), attract an initial burst of media coverage and then dissipate as the technology in question proliferates and becomes commonplace and valued, making the alarmist claims harder to sustain when the threatened disease increases fail to materialise.

Figure i.1 The progression of nervousness. Source: George M. Beard (1880), American nervousness: with its causes and consequences (Claude Moore Health Sciences Library 2007).

My family had the first television set in our small street in Bathurst, New South Wales in the early 1960s. CBN Channel 8 began broadcasting from the town of Orange on 17 March 1962. The kids from the street would gather in our living room after school to watch programs like The Mickey Mouse Club, but some were anxious that their parents would find out, as they had been told not to watch television because of the danger of ‘rays’ being emitted.

Today, someone expressing constant anxiety about the dangers of radiation exposure from watching television would be seen as decidedly technophobic, or plain wacky.

When mobile telephones were introduced into Australia in the 1980s, there was considerable popular anxiety about transmission towers causing unspecified disease in those who were exposed. In 1995, Tony Abbott, who would go on to disparage wind energy as Australian prime minister, publicly stoked local anxiety about a mobile base station in the northern beaches area of Sydney, where he was the federal MP for Warringah. A collection of Sydney television news clips from 1995 gives the flavour.8 I wrote about this in the Sydney Morning Herald in March 1997, noting the utter irrationality of the Lane Cove local council’s regulations regarding where transmission towers could be placed in relation to different types of buildings and facilities.

Local councils in Sydney have struggled to respond to growing resident action about the placement of mobile phone towers across their municipalities. Recently I received a letter from one informing me about decisions regarding minimum distances towers can be located from people.

Note here that it is ‘distances’ not ‘distance’. If you live in the council district, the council will not allow a tower within 300 metres of your house. But if you work in the area, the towers can come as close as specified in any deal struck between your employer or a landowner and a phone company. They can plonk one right outside your office or factory window, in your car park, wherever.

The council wrote that it had taken ‘potential health impact’ into account in fashioning its resolutions. From this, we can draw one of two conclusions: that the council believes people at work are somehow more robust than people in houses to resisting the alleged health effects of radio frequency radiation (RFR) emitting from the towers; or that it finds this a preposterous idea and instead believes that workers are less uptight about exposure than residents and won’t mind a tower or two. What the thousands who work and live in the area are supposed to make of this is anyone’s guess.

But wait, there is more. If you are in a school, any sort of child-care facility, a hospital or, most intriguingly, ‘any recreational facility’, you won’t find a tower within 450 metres of you. Observe that yet further layers have now been added to this emerging hierarchical model of radiation susceptibility.

Someone playing golf, bowls or having a picnic apparently cannot resist RFR like a worker can. Along with infants, children, the sick and the elderly, those taking recreation get to enjoy an extra 150 metres buffer zone. Or at least while the kids are at day care or school. When they go home in the afternoon, the council thinks it’s OK to locate the towers up to 150 metres closer. Given that children spend more time at home than in school, the two different minimum distances cannot reflect any rational concern to minimum exposure.9

This sort of utterly capricious and bizarre approach to distance zoning was repeated years later in policies on the minimum distance that wind turbines could be placed from residences (see Chapter 3).

Today, more than 30 years since the introduction of mobile phones into Australia, we still see very occasional instances of concern, as in the case of the distressed woman seen in a 2013 news report wearing a cloth head cover, convinced that it will somehow protect her from the feared radio frequency radiation being emitted from mobile phone transmission towers.10 Such expressions of anxiety are now extremely uncommon. Near universal use of cell phones and the accompanying widespread rollout of transmission towers, together with no evidence of any rise in the national incidence of brain cancer (the condition most frequently nominated by alarmists as likely to arise from exposure to mobile phones),11 make the claims sound incredible.

Early close personal encounters

I first saw windfarms while living in Lyon, France in 2006 during a research sabbatical. On various trips I saw occasional clusters of them and thought they looked quite majestic: they seemed emblematic of an exciting future in which the world would start moving to renewable energy. Like many, I saw them as being all about the non-polluting harvesting of an endless, free resource. Here was this century’s natural progression of previous centuries’ use of wind to sail ships and turn windmills, but to a degree that offered part of the solution to the growing problem of global warming from carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions: a problem that 97 percent of the world’s climate scientists agree is real, increasingly caused by humans, and likely to be catastrophic if not rapidly abated.12 As has often been remarked, if 97 percent of the world’s leading relevant specialist doctors told you that you needed a lifesaving operation and 3 percent said that you need not worry, a decision to trust the 3 percent would almost certainly be ‘brave’ or utterly unwise. Moving to replace polluting energy sources with renewable energy, including that generated by windfarms, is at the very front line of solutions that offer some hope of averting or reducing the size of that catastrophe. Yet a small but determined number of people are determined to wreck that hope.

Three Australian Senate inquiries

Political opponents of windfarms in Australia caused there to be three Senate inquiries into windfarms in the five years between 2011 and 2015. There have also been two state government inquiries, in South Australia and New South Wales, both in 2012. The 2015 Senate inquiry saw the main political opponents of windfarms dominate the Senate committee, with just one member, Senator Anne Urquhart, Labor Senator for Tasmania, taking a contrary position.13

The majority report that was published is an utter travesty of impartial inquiry. It was the report of a committee set up and populated by four sworn enemies of windfarms, exercising their power within a parliament led by a prime minister (Tony Abbott) who infamously declared that climate change was ‘crap’ and who in 2015 recalled that the only wind turbine he had ever been close to (on Rottnest Island) was ‘ugly and noisy’.14 ‘Local authorities said this was the first complaint they had ever heard,’ he observed.15 Abbott found no difficulty in throwing a juicy bone to four salivating members of the Senate crossbench (John Madigan, Bob Day, David Leyonhjelm and Nick Xenophon) and encouraging them to unleash their contempt for windfarms and give a major stage to a wide range of impassioned, unswerving opponents. Abbott would have hoped that by indulging their fantasies, he would ingratiate himself to them and quid pro quo secure their vital votes on government legislation. At various places throughout the book we look at what this oddball committee had to say about the evidence relevant to health issues that it received. The main outcome of the committee’s report was the establishment of a National Wind Farm Commissioner charged with investigating complaints about windfarms. In March 2017, the much anticipated first report was released by the commissioner, Andrew Dyer. We will consider this report and its findings in Chapter 6.

When I saw windfarms occasionally in France in 2006 I gave them little thought. It certainly never occurred to me that I was looking at agents that might cause health problems. I was unaware that at that time in Australia, there were already some 22 windfarms operating. I’d never seen any at home nor even read of their existence. In the European autumn of 2008, I holidayed in the Minervois district of Languedoc in southern France and this time I saw many clusters of them. They were unavoidable on any trip in any direction in that part of France. I drove up very near several of these and became fascinated. At that time, I’d still never encountered any suggestion that they might be somehow toxic to those living near them. Villages and farm houses were all around them.

I first encountered this claim in February 2010 when I heard a radio report about some distressed residents living near the newly opened windfarm near the central Victorian hamlet of Waubra, near Ballarat. At the time I was writing regularly for the online news source Crikey and its health-focused cousin, Croakey.16

I decided to write a piece triggered by the news report. I asked whether the health claims being made were:

calculated displays from a few people seeking to cash in on hopes of land sales or compensation? Do they reflect genuine health effects actually caused by the noise from the wind farm? Or are they equally genuine health effects caused by residents’ anxiety about the towers?17

In Chapter 7, I describe the reaction caused by this first dip of my toe into the shark-infested waters of windfarm opposition and my subsequent five years of public engagement with this issue.

In May 2014 (just an hour after reading online that the then Australian treasurer, Joe Hockey, had described windfarms as ‘utterly offensive’),18 my wife and I were driving through the Andalusian plains of southern Spain past hundreds of wind turbines quietly turning on ridges, often near towns. Spain is one of many European nations that has taken wind energy very seriously, with 23.1 gigawatts (GW) of installed capacity, the fifth most in any nation. Australia has just 4.237 GW, putting us in 17th position (see Table i.1).

| Country | Gigawatts installed | Country | Gigawatts installed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 China | 168.732 | 11 Sweden | 6.520 |

| 2 USA | 82.184 | 12 Turkey | 6.081 |

| 3 Germany | 50.018 | 13 Poland | 5.782 |

| 4 India | 26.700 | 14 Portugal | 5.316 |

| 5 Spain | 23.074 | 15 Denmark | 5.298 |

| 6 UK | 14.543 | 16 Netherlands | 4.328 |

| 7 France | 12.066 | 17 Australia | 4.327 |

| 8 Canada | 11.900 | 18 Mexico | 3.527 |

| 9 Brazil | 10.740 | 19 Japan | 3.234 |

| 10 Italy | 9.257 | 20 Romania | 3.026 |

Table i.1 Top 20 nations by installed wind power capacity (Global Wind Energy Council 2017).

Seeing windfarms and solar energy expanding, I felt hopeful that my children and grandchildren will grow up in a world in which clean energy will complement, then match, and eventually replace polluting fuels, at prices commensurate with the fact that the fuel it uses is free and boundless. What’s not to like?

In 2015, I drove with my wife down to Waubra, to get up close to some of the 128 turbines on Australia’s most publicised windfarm. In 2010 Waubra had been chosen by a small group of anti-windfarm activists in naming their Waubra Foundation, an organisation subsequently stripped of its Australian Charities and Not-for-Profits Commission ‘health promotion’ status in 2014.19 In 2013, it ignored a petition signed by more than 300 Waubra residents asking the Waubra Foundation to stop running down the town’s name for its self-absorbed cause.20 I wanted to see for myself what the fuss in Waubra was about. For several hours we drove around the local roads, stopping the car a dozen or so times near different turbine clusters. It was a warm, sunny day, with a mild yet obvious wind blowing. All the turbines were turning, powering what one turbine-hosting farmer told us later was enough for 110,000 homes, just from this one windfarm.

Inside the car with the windows up, we could hear nothing. Outside the car, the overwhelming sound was that of the wind blowing in our ears. Beneath that sound was the barely audible sound of the gently turning blades. To even call it a ‘whooshing’ sound would be very misleading. That’s a word I would use to describe convoys of large trucks driving past you at speed as you stood on the side of a road. It was more like the sound of a slightly amplified whisper in the distance. In Chapter 3, we provide a sample of some of the more colourful turns of phrase that windfarm opponents use to describe this slight sound.

My wife, who had not been near an Australian windfarm before but had often heard me talk about the Waubra objectors, was incredulous. The first time we stopped the car, turned off the motor and stepped outside, she opened with a forceful ‘You must by joking!’, followed by ‘This is just nothing compared to what hundreds of millions live with every day in the world’s cities.’

Indeed. And in fact people like us. I live in Sydney’s inner western suburb. Depending on the wind direction, we, along with hundreds of thousands of others living under Sydney’s three flight paths, get these planes sometimes as frequently as every two minutes, from the moment the second hand sweeps past 6am until a last boomer takes off at about 10.40pm each night. The planes are often 300 to 400 metres above our roof.

The planes always stop conversation outdoors and sometimes rattle our double-glazed soundproofed windows. On days with low cloud, the noise is very much louder, with echoes of trapped noise flashing back and forth as the planes pass overhead. We’ve lived under the main flight path for 26 years, raised three children and two grandchildren here, and had countless dinner parties and conversations. The noise that surrounds every city resident is incomparably louder and more constant than that experienced by people living near windfarms. And as we shall see in Chapter 2, city residents are also bathed in infrasound, the sub-audible component of total wind turbine sound that is the focus of much of their opponents’ anger and anxiety.

At Waubra we visited a turbine host who had seven or so towers on his sheep farm. We made our way to the nearest turbine, about 500 metres from his house. Hundreds of sheep grazed contentedly in the shade of the tower, many of them having sought it out to rest. My collection of 247 symptoms and diseases said to be caused by windfarms (see Appendix 1) contains several entries about sheep, but apparently no one had told these sheep that they should feel disturbed.

Our host chuckled about the local objectors: ‘I think for most of them, being complainers has become part of their identity. They get to see their name in the newspaper. They get to travel around the place telling their story.’

Understanding public health anxieties

Our interest as authors in this issue has been in no small part an extension of a longstanding interest we’ve both had in the ways in which putative risks to health are understood and communicated within communities and in the news media. Risk-communication researchers have long identified elements of risk perception which are likely to amplify community anxiety and outrage about alleged environmental hazards. In 1997, I co-authored a paper on this as it applied to community concerns about mobile telephone towers.21 When a hazard is believed to arise from exposure to a natural source or agent, anxiety is low compared to when the source or agent is thought to be industrial or artificial. We rarely hear of communities living in windy locations describing symptoms caused by the sound of wind itself, despite wind having frequencies in the audible and sub-audible ranges (see Chapter 2). But with windfarms the sound is perceived as being somehow artificial in origin, and so of greater concern. Hazards that are imposed on people, as opposed to voluntary exposures, also increase outrage. People who ski voluntarily and enthusiastically expose themselves to a high risk of serious injury without complaint. But there are legions of examples of extremely low-level risks ‘imposed’ on communities causing mild panics. In Chapter 5, we provide a chart looking at factors known to be relevant to panic and outrage about often low-risk agents, illustrating the case of wind turbines.

Similarly, the ‘new’ can provoke anxiety. Mobile phone towers went through a phase of alarming some citizens who had for many years blithely walked without a care in the world past suburban electricity substations and TV and radio towers. Today communities are used to the sight of mobile phone transmission base stations and the outrage sometimes seen in the past is now rare.

In public health, when the goal is to have people change their behaviour in some way, there are two broad risk communication goals. If people are unaware of or indifferent to a serious risk, the task is to find ways of making them more aware and sufficiently concerned to take action, whether this be to avoid exposure to an agent, to stop or reduce doing something like smoking, eating a poor diet or drinking and driving, or to start or increase a behaviour like immunisation, physical activity or safe sex.

But there are also many issues where people’s behaviours reflect sometimes wildly exaggerated concerns about things that in fact pose negligible risk. Such health anxieties can cause large numbers of people to worry needlessly about extremely low-probability risks, seeking medical advice and testing and self-medicating unnecessarily. Some get clinically anxious and consumed by their fears. (Worse, some may misattribute illness to the wrong cause, and thereby deprive themselves of readily available and effective treatments.)

People’s lives can be significantly adversely impacted when they become preoccupied by erroneous beliefs. In extreme cases they can develop excessive anxiety or debilitating phobias about extremely low risks such as air travel, household ‘germs’, ‘chemicals’, or radio signals. When such personal irrationalities are championed by those in power, like politicians and sections of the news media, it is not just the irrational whose lives can be affected. If those opposed to wind energy were to succeed in greatly inhibiting the rollout of windfarms in Australia and the handful of other nations where windfarm opposition has occurred, the speed with which we can combat climate change could be greatly compromised. Successful opposition to windfarms globally could have extremely serious consequences for life on earth.

Outline of this book

In the first chapter, we sketch the history of the development of wind turbines, from the iconic windmills most readily identified with the Netherlands, to early small-scale prototypes of electricity-generating windmills that began to be designed late in the 19th century, through to today’s global explosion in the harvesting of wind as renewable energy and the exciting recent developments in battery storage that are rapidly expanding as we write.

We then review the various objections initially made by those opposed to windfarms. These included concerns about aesthetics, and the economic and local environmental impacts of windfarms, their alleged negative impact on land values, and their supposed propensity to decimate bird and bat populations. It was only later that objectors decided to turbo-charge the idea that living (or even spending short amounts of time) near wind turbines could endanger human health. Non-health concerns are still voiced today, although health issues are probably those most often advanced by objectors in the handful of nations where anti-windfarm groups are active.

The book’s central focus is on claims that wind turbines are the direct cause of illness in some of those exposed to them, and in Chapter 2 we explore the emergence of this proposition. The notion began to attract minor attention from around 2002, when claims made in unpublished ‘research’ by a British doctor were covered by a few news outlets and began to be circulated among objectors.22 The 2009 appearance of a self-published book, Wind turbine syndrome, by a US paediatrician, Nina Pierpont, acted like petrol thrown onto a fire of latent anxiety in a small number of communities where activists were doing their utmost to spread concern and to urge people to attribute common health problems to sub-audible sound emitted by the turbines.23 The book put the alleged health issue on the global map, although as we shall see, concerns about windfarms and health are virtually unknown in most nations which have windfarms today. In Chapter 2 we also look forensically at a sister ‘disease’ to the non-disease of wind turbine syndrome: vibroacoustic disease (VAD). We show its origins as a concept developed by a heavily self-citing Portuguese research group.24 On the basis of a case study about a single person presented at a conference, VAD was suddenly also deemed by this research group to be caused by wind turbines. VAD remains largely unrecognised by others. While there are occasionally claims made about the audible sound of wind turbines turning, it is the sub-audible low frequency infrasound emitted (at entirely unspectacular levels) by wind turbines (and importantly for the argument we will develop in this book, also by wind itself) that has been the focus of most of the claims that wind turbines cause humans and animals to become ill. So in Chapter 2 we critically examine the proposition that infrasound from wind turbines might be noxious while that emanating from a wide range of other natural and mechanical sources is, judging by the lack of claims about them, apparently harmless.

We then examine the seemingly unending number of symptoms and diseases that windfarm opponents have claimed afflict humans and animals exposed to turbines. I have been vigilantly collecting these claims since early in 2012, much to the amusing chagrin of windfarm opponents, who seem confused about whether they believe the many problems on the list are real, or privately understand that the publicity I have generated about the range of problems being advanced is harming their cause, simply because many of the claims are so ludicrous. Take the time to read through the list in Appendix 1 and decide for yourself.

In Chapters 3 and 4, we consider in detail the flaws inherent in claims made by windfarm opponents that exposure to wind turbines is a direct cause of health problems. In Chapter 3 we critically examine a series of ‘gotcha’ arguments repeatedly used by windfarm opponents, such as the claims that only those ‘susceptible’ suffer and that turbine hosts are contractually gagged to not complain. We consider the peculiar tendency for windfarm complaints to appear mostly in English-speaking nations and how the ‘drug’ of money seems to be a wonderful antidote against complaining. We finish Chapter 3 with a close examination of claims that in Australia ‘over 40’ families have had to abandon their homes because of wind turbine noise. My attempts to chase down the evidence behind this factoid saw efforts mounted to try and stop me doing so. We describe those efforts in Chapter 7.

In Chapter 4 we look at studies that have been repeatedly exalted by opponents as allegedly constituting serious evidence that wind turbines cause direct harms to humans and animals. These arguments and papers appear to be the best shots that windfarm opponents have been able to muster. Readers queasy about blood sport are warned that this section is not for the faint-hearted. Some of the studies we review here are appallingly inept and pointing out their many weaknesses may appear cruel.

By 2015, there had been 25 reviews published of the evidence that windfarms are a direct cause of health problems. In Chapter 4 we summarise the conclusions of these reviews, highlighting that published in 2015 by an expert committee of Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council.25 We end Chapter 4 by summarising the findings of what is by any assessment the largest and most important study of whether wind turbines adversely affect health: the 2014 Health Canada Study.26

In Chapter 5 we turn to the main argument of this book: that ‘wind turbine syndrome’ and the various claims that go along with it are a casebook example of what we have called a communicated disease: a ‘disease’ that can be spread by people talking, reading, and writing about it. We will first explore the phenomenon of the nocebo effect, the inverse of the well-known placebo effect (placebo is Latin for ‘I shall help’; nocebo means ‘I shall harm’). Placebo effects occur when personal expectations that something will make a symptom improve or disappear lead to it doing just that, even when the agent involved is completely inert. Nocebos work in the opposite direction: being told that exposure to something is likely to have an adverse outcome will often produce such an outcome, even when the agent concerned is inert or non-existent.

We argue that concerns about wind turbines can foment anxiety in some people who have those concerns. Anxiety can produce real affective somatic symptoms, and some of those who loathe windfarms attribute their symptoms to direct impacts of the turbines, not to their anxiety about those alleged impacts. We look closely at several areas of evidence that make the case for direct effects impossible to sustain.

In Chapter 6, we will introduce readers to some of the main opponents of windfarms in Australia. We will look at the main organisations that have operated in Australia; an anonymous, frequently defamatory website that daily posts poisonous material about wind energy and anyone seen to be supporting it; acousticians who have worked with windfarm opponents; and the principal politicians who have lead the charge against windfarms in Australia.

A small number of anti-wind activists operating mainly in parts of Canada, the USA, the UK, Ireland, New Zealand and Australia have made wind turbine syndrome their cause célèbre. Without exception, they see themselves as contemporary Galileos, fearlessly holding aloft the truth in the face of doctrinaire, conspiratorial denial from the scientific establishment, which has now published 25 reviews of the evidence since 2003. These conclude there is very poor evidence for claims of direct health effects from wind turbines. The activists point knowingly to the historical denials of harm by the asbestos and tobacco industries, convinced that the pernicious ‘Big Wind’ industry is reading from the very same playbook (see Chapter 3).

In a career in public health of some 40 years, I have rarely encountered the virulence and sheer nastiness that I have experienced since becoming involved in this issue. Chapter 7 describes the main attacks used by anti-windfarm interests that I have experienced since first writing about this issue in 2010. Sunlight makes a powerful antiseptic.

In the final chapter, we attempt to look at what governments, the wind industry and communities might do to reduce anxiety and opposition to wind turbines. Many nations have experienced few or no health claims about windfarms or indeed much anti-windfarm sentiment at all. There are lessons to be drawn from this.

We are both social scientists. In Chapter 6, we describe windfarm opponents’ efforts to narrow the range of expertise deemed relevant to evidence and policy debate about alleged windfarm harms. Social scientists, unless their findings are considered useful to anti-wind agendas, have frequently been pilloried by opponents as unqualified to contribute. This is because the questions that social scientists bring to the debate are both obvious and unavoidable, and threaten efforts to frame the debate narrowly in terms of soundwaves striking human ears.

Social scientists working in health and medicine have long asked fundamental questions about patterns of illness that do not conform to the predictions of medical models. We ask questions about the social, cultural, economic and communicative environments that see often highly variable susceptibility in populations to putative risks.

Anyone who has been near a windfarm knows how quiet they are compared to the many noises that we are all surrounded by, particularly if we live in cities. If you have never visited a windfarm, we would strongly encourage you to do so. (Some windfarms allow the public, by special arrangement, to sleep out in very close proximity to turbines.) The difference between what you may have heard about the sound of wind turbines and what you will experience is a major ‘penny drop’ experience. We hope this book will provide a valuable truth serum for readers wanting background on how to interpret the manufactured controversy about wind turbines causing disease.

1See http://www.word-detective.com/2009/03/tilting-at-windmills/.

2Simon 2005, 4.

3Simon 2005, 91.

4Simon 2005, 367.

5Anon. 1889.

6Claude Moore Health Sciences Library 2007.

7See: powerlines (Safespace n.d.); televisions (EM Watch n.d.a), electric blankets (Mercola 2009), hair dryers, washing machines (Carpenter 2012), microwave ovens (Wayne and Newell n.d.), computer screens (EM Watch n.d.b), mobile phones (EMR Australia 2015) and transmission towers (Chapman and Wutzke 1997), and, most recently, wi-fi (Group 2015), smart electricity meters (EMR Australia n.d.), LED light bulbs (Mercola 2016), and solar electricity roofing panels (Chapman 2015a).

8Chapman 2014a.

9Chapman 1997.

10See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5LZMFZF4F4.

11Chapman, Azizi et al. 2016

12NASA 2013.

13Commonwealth of Australia 2015e.

14O’Brien 2010.

15Cox and Arup 2015.

16Sweet, Chapman et al. 2009.

17Chapman 2010.

18Bourke 2014.

19Conroy 2014.

20McGrath 2013.

21Chapman and Wutzke 1997.

22Harry 2007.

23Pierpont 2009.

24Chapman and St George 2013.

25National Health and Medical Research Council 2015.

26Health Canada 2014.