7

Case studies

Case study 1: Improving the livelihood of farmers in Bougainville

Merrilyn Walton, David Guest, Grant Vinning, Grant A. Hill-Cawthorne, Kirsten Black, Thomas Betitis, Clement Totavun, James Butubu, Jess Hall and Dr Josephine Yaupain Saul-Maora.

Partners

University of Sydney (School of Life and Environmental Sciences, School of Public Health), Autonomous Bougainville Government, University of Natural Resources and Environment, PNG Cocoa Board.

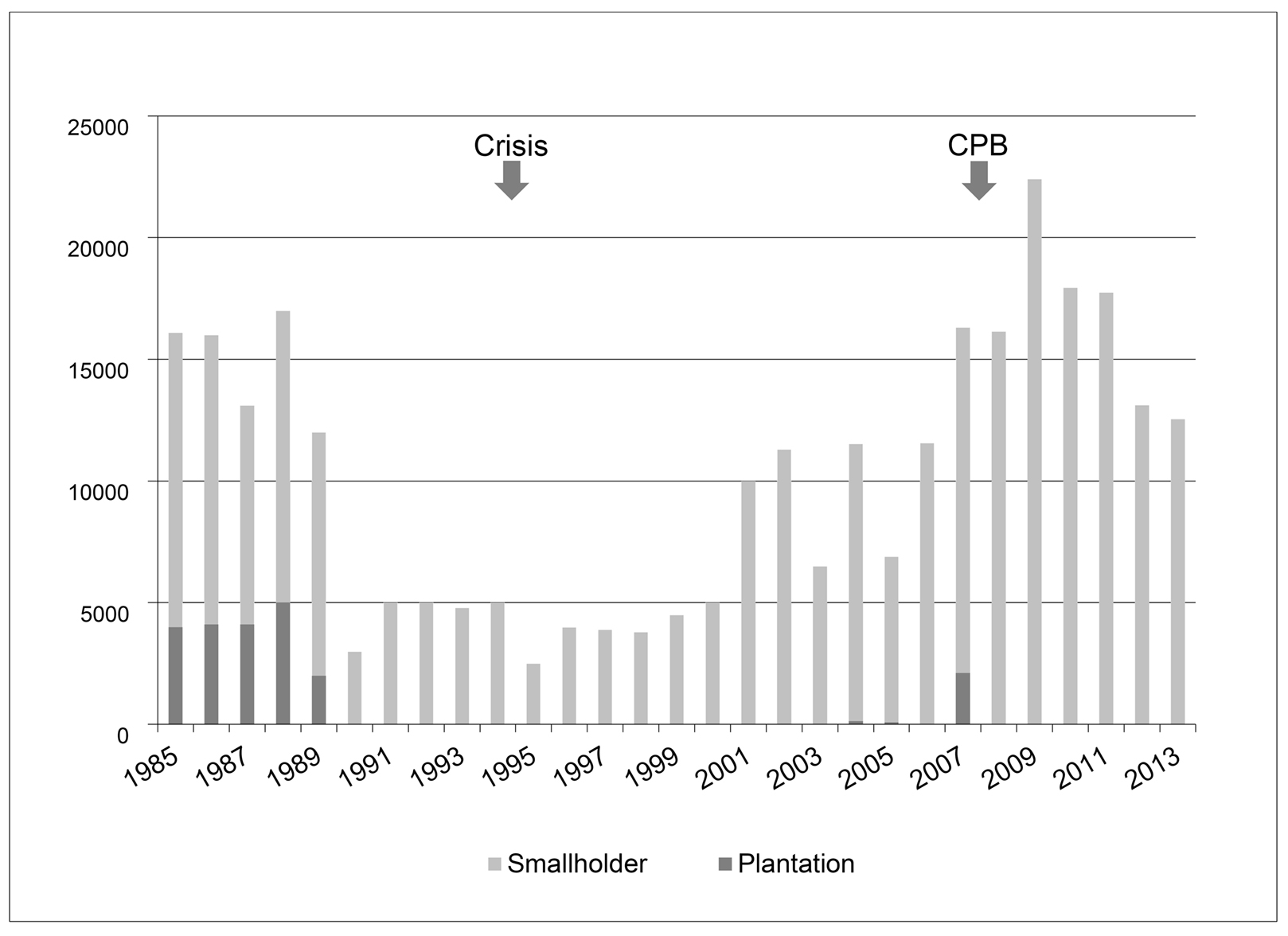

Nearly two-thirds of the population in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville (ARoB) produce cocoa. Before the Bougainville civil war, also referred to as the Bougainville conflict or ‘the crisis’ (1988–1998), about 28 per cent of the total annual production of 15,600 tonnes of Bougainville cocoa came from large plantations (Scales and Craemer 2008) (Figure 7.1). During the crisis, many of these plantations were abandoned and there was a collapse of smallholder production. When the civil war ended, many farming communities rebuilt their lives by focusing on crops that had the most potential to improve their livelihoods. Despite internal and external efforts, the potential benefits of improved cocoa management have not yet eventuated, due to inadequate extension support, labour shortage and inefficient cocoa supply chains.

The crisis had a similarly profound impact on the health sector with the destruction of hospitals and loss of health workers (AusAID 2012). Since 2010 many key health indicators have improved but a great deal more work is required. Childhood stunting along with maternal health are believed to be a significant problems. Importantly the extent to which poor health and access to health services impacts on the work and activities of daily living of people in Bougainville has not been examined (World Bank 2008).

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of this project, derived from priorities identified by communities in the ARoB, is to improve the profitability and vitality of smallholder cocoa-farming families and communities. The project envisaged public and private sector partnerships and the development of enterprises that enhance productivity and access to premium markets, while promoting gender equity, community health and wellbeing.

The project had the following objectives:

- Improve the productivity, profitability and sustainability of cocoa farming and related enterprises;

- Understand and raise awareness of the opportunities for improved nutrition and health to contribute to agricultural productivity and livelihoods;

- Foster innovation and enterprise development at community level; and

- Strengthen value chains for cocoa and associated horticultural products (ACIAR Project Proposal HORT/2014/094, 2016).

Getting the right team together

Cocoa-farming families were central to this project. While increased cocoa production was a primary goal, past experience suggested a focus on agriculture alone would not bring success. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach involving agriculture, health, nutrition, animal husbandry and economics was required. Research in most low-resource countries has historically been undertaken using a siloed approach involving just one discipline, with the focus being on a specific area – crop management, or health, or markets. But the experienced lives of people are not neatly compartmentalised – poor health may stop a farmer looking after their crops, a good harvest may rot without an accessible market, and fruit may wither on the vine without attention to climate and pests.

Engaging with communities

Prior to funding, the researchers had a relationship with the communities, having previously worked with them as well as meeting with the communities to explore their health concerns. Once the grant was confirmed, the team met with the ARoB collaborators and visited the communities in Village Assemblies across Bougainville to explain and seek feedback on the aims and approaches of the project, raise awareness of the project and generate community interest.

The community engagement process involved initial meetings with village community members to provide a summary of the project. Separate meetings were held with women and youth to ensure their voices were heard. We collated and analysed the information to ensure that the project incorporated realistic and viable suggestions or comments. During the initial meetings, names of potential community leaders were also obtained. One-on-one meetings were set up with these leaders, who were crucial in preparing for the livelihood surveys.

The project team and the cocoa farmers recognise that intensified farm management – including rehabilitation of existing cocoa, replanting with improved genotypes, improved cocoa agronomy, soil management and integrated pest and disease management (IPDM) – results in higher yields of cocoa beans (Konamet al. 2011). Different extension approaches that support intensified cocoa production will enable supplementary activities, such as food crops and small livestock, and activities to generate incomes for women and youth (Daniel et al. 2011). Diversifying incomes can improve livelihoods, including improved nutritional outcomes.

An annual chocolate festival sponsored by the project in partnership with the Australian High Commission in Papua New Guinea and Autonomous Government of Bougainville (AGB) is now a major community activity with the third festival celebrated in September 2018. Traditional field-day activities include demonstrating new planting materials, fermentation, livestock husbandry, food crops and community health activities. Cocoa buyers and other value-chain stakeholders participate. Music, sports, games and cultural activities are integrated into the festival program. The chocolate competition is a major event, attracting cocoa farmers who supply beans that are processed and made into chocolate samples. Papua New Guinea’s largest chocolate maker, Queen Emma in Port Moresby, made the chocolate for judging in the first two festivals according to a standard recipe. In 2018, beans supplied by the growers, were for the first time, prepared for judging at the newly established chocolate processing laboratory built by the Department of Primary Industries and Marine Resources in Buka. Trained chocolate judges and chocolate makers evaluate and rank each sample, with farmers producing the highest quality beans recognised in an awards ceremony at the festival.

Figure 7.2 Chocolate festival: Arawa, Bougainville, 2016. Photo: Grant Vinning

Funding

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research allocated funding to assist these communities, with a grant being awarded to a multidisciplinary team from the University of Sydney and collaborating partners in the Bougainville (ARoB) Department of Primary Industries, the Cocoa and Coconut Institute of PNG Ltd and the University of Natural Resources and Environment, PNG. Underpinning the funding for this AUD$6 million, six-year project was Australian support for building economic development in the ARoB; one that aimed to support a healthier, better educated, safer and more accessible Bougainville (Australian High Commission 2014).

Methods

Since there were few data available about livelihoods, the first step was to obtain baseline data against which improvements could be measured and priorities established. Survey questions were derived from the following validated questionnaires: the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, the USAID Demographic and Health Survey and the WHO World Health Survey, all of which have been used in similar low resource settings. The questions relating to agriculture practices and equipment were developed in a previous ACIAR project (HORT/2012/026) and had content validity.

We used CommCare, a simple mobile data acquisition tool, to collect data about geopolitical factors, economics, populations, livelihood strategies, housing standards, education, healthcare, access to mobile phones, banking, farm sizes and enterprises, details of cocoa activities (number and age of trees, management, yields, fermentation and drying, marketing etc.), and exposure to past training. Data were collected by trained interviewers who were selected from each of the three regions in Bougainville – Buin (South), Arawa (Central) and Tinputz (Northern). Data were collected over a 12-month period and entered into tablets using CommCare; the data was downloaded and compiled centrally.

Results from these surveys have been presented back to communities at meetings held in the three Research and Training Hubs established as part of the project. In addition, the health results have been provided to the ABG Secretary of Health who has used the data to develop the strategic health plan.

Box 7.1: Criteria developed with community for selection of villages and Village Assemblies

a. Had to be growing cocoa or identify as a cocoa farmer

b. Motivated and showing leadership

c. Possibility for expansion outside of Village Assembly (VA) with large population group

d. Need to complement existing projects on the ground

e. Balance between villages with good transport access and more remote communities

f. Balance between communities that have and haven’t received support before

g. Avoid duplication with other projects

h. Potential for diversification

i. Security of farm ownership and Village Resource Centre security

j. Geographic spread.

The methods for each of the project objectives are summarised below.

Objective 1: To improve the productivity, profitability and sustainability of cocoa farming and related enterprises

Meetings held with Bougainville Government, district government officers, cocoa farmers and village consultations; selection of participating villages

Data on cocoa farming were collected as part of the Baseline Livelihood and Health survey. Thirty-three communities across Bougainville were selected on the basis of transparent criteria and with guidance from the ABG Departments of Primary Industry and Marine Resources and Health and Community Government (see Box 7.1). These communities were surveyed. Village Resource Centres (VRCs) are being established in each Village Assembly (Since the research the name Village Assembly has been changed to Ward.), and Village Extension Workers (VEWs), of whom at least 40 per cent are female, are being selected and trained.

In each of the three regions 11 Village Assemblies (total n = 33 VAs) were selected and all households and villages in the selected VA were included in the study population.

Training of DPI Senior Facilitators, District Officers and selected VEWs

Intensive training was provided for DPI staff to be senior facilitators based at each of the three hubs (a total of 12). Selected participants attended a residential course over two weeks at the Mars Cocoa Academy in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Mars facilitated the training of facilitators with follow-up training delivered at the Kairak Training Centre by CCI and the University of Natural Resources and the Environment (UNRE) staff.

Establish baseline data about cocoa and other farming activities

Basic data were collected on the size and number of cocoa blocks, genotype, age and source of cocoa trees, farming equipment, land ownership, labour, food crops, livestock and incomes.

Establish village budwood gardens and nurseries

The availability of new planting materials limits cocoa rehabilitation. Nurseries are also seen as an alternative source of income for male and female farmers with restricted access to land.

Evaluate soils and compost and fertiliser requirements

Intensification of cocoa production requires improved soil management to sustain higher yields. Farmers have limited access to synthetic fertilisers, and previous research has shown the benefits of on-farm composts, that recycle waste and improve soil fertility. Soils vary, so local trials are to be established to determine optimum soil management.

Establish IPDM demonstration plots

Demonstration plots show the impacts of improved cocoa management, and also serve as training sites (‘classrooms in the cocoa block’ Guest et al. 2010).

Establish mobile support networks

Very few trained extension staff are available and their travel to remote villages is rare. Establishing mobile networks based on the tablets used in the CommCare surveys enables better access to their skills and advice.

Farmer training

Villages also requested training in cocoa management and processing, supplementary crops, food crops, livestock, budgeting, market access and family teams.

Objective 2: To understand and raise awareness of the opportunities for improved nutrition and health to contribute to agricultural productivity and livelihoods

Establish the extent to which health (including nutrition) and disease impacts on farming activities and workforce availability

This objective had six parts (health includes nutrition):

- Conduct livelihood survey in the 33 Village Assemblies

- Establish baseline data about the health of cocoa-farming families

- Establish the extent to which health and disease impacts upon farming activities

- Establish the health priorities of each community

- Develop an evidence-based cocoa-health framework (Cocoa Farmers Health Framework) that describes best practice in healthcare for communities

- Link with the Department of Health to facilitate community access to and use of existing healthcare services in VRCs.

Establish Advisory Committees

Each participating community has an advisory committee to oversee and guide the studies on the adoption of intensified and diversified cocoa-farming systems and the impacts of health on agricultural labour productivity. This committee is chaired by an appropriate village leader and includes women, youth and cocoa farmers along with the project team.

Terms of reference include oversight of the following activities:

- Approval of the research objectives

- Scope of the health research, including data collection

- Opting out of the health surveys and data collection

- Development and approval of mobile-based tools for collecting data

- Development of educational and training material and technological aids

- Identification of locations for data repositories

- Management of VRCs.

ARoB, district, cocoa farmers and village-level consultations

The impetus for the health component was initiated by cocoa-farming families. This invitation led to initial, but extensive, community consultations and observational visits. We held interactive discussion groups with some of the intervention communities to identify their specific needs and agree upon a realistic focus for the next steps. In order to expand upon this initial work, we conducted additional consultations at all levels (village, district and governmental) to ensure that this project integrating health and agriculture is sustainable and locally relevant to the communities and stakeholders.

The questions posed were:

- What are the main health concerns for the community?

- How are the health needs of the community currently being met?

- Can community members access relevant information via a spoken web application on basic mobile phones?

- Is the Cocoa Farming Health Framework a useful framework for identifying best practice in meeting a community’s healthcare priorities?

- Will this be a sustainable model?

By answering these questions, we anticipate we will be able to:

- estimate the extent to which poor family health is impacting on productivity

- estimate the extent to which communities have access and can utilise primary healthcare facilities

- estimate the impact of health educational strategies (written and telephone aids)

- estimate immunisation coverage.

Link health information to rollout of satellite farmer training

In this stage, we plan to link Department of Health programs to the rollout of satellite farmer training centres in remote villages across Bougainville – Village Health Volunteers based alongside Village Extension Workers in Village Resource Centres.

Objective 3: To foster innovation and enterprise development at community level

Support the establishment of DPI regional research hubs in Bougainville

During the decade-long crisis most government and public infrastructure was destroyed. The Department of Primary Industry and Marine Resources (DPI) is the Autonomous Bougainville Government (ABG) department responsible for supporting the redevelopment of agricultural livelihoods. This project is assisting the department to build three regional hubs for applied research and training of village extension staff and farmers.

Establish Village Resource Centres linking CCI, UNRE, AVRDC with DPI and DoH

Trained Village Extension Workers (VEWs), supported by the ABG, the PNG Cocoa Board, PNG University of Natural Resources and Environment and World Vegetable Centre, will establish village resource centres (VRCs) in targeted Village Assemblies. These VRCs will focus community activities in agriculture, health and community development, and will provide feedback on local requirements for future activities.

Develop supplementary food crop and livestock enterprises

While cocoa is a potentially profitable and rewarding cash crop, farmers need to build resilience to buffer radical shifts in world cocoa commodity markets. Supplementary enterprises, including nuts, fruits and food crops as well as small livestock, not only diversify family income, but provide additional income earning opportunities for women and youth and valuable sources of family nutrition.

Support economic development through enterprise development

Intensifying cocoa production requires land, labour and resources that may not be available to all farmers. On the other hand, intensification also supports specialisation so that new business opportunities open up for farmers choosing not to invest in cocoa production, such as establishing nurseries, fermenteries, composting facilities, trading posts and small livestock husbandry. These new enterprises contribute to the resilience of farming communities.

Monitor farming systems

These developments in village activities will be monitored using the Livelihood and Health surveys to evaluate the social and economic impacts they have on village communities.

Objective 4: To strengthen value chains for cocoa and associated horticultural products

- Improve quality through better post-harvest handling, fermentation and drying

- Develop cocoa value chains and market access

- Extension, education and capacity building

- Link resource centres with schools/technical colleges to facilitate technology/skills training and transfer

- Chocolate festivals.

Outcomes

At the time of publication this project had reached the three-year milestone. In that time, the Chocolate Festival has become an annual event celebrating chocolate and the role of cocoa farmers, and linking farmers to buyers and chocolate makers. The livelihood survey has been completed for all three regions and is being analysed. A total of 5,172 respondents completed individual surveys with information available on 12,397 registered household members. A report on the Livelihood Survey has been presented to the Government of Bougainville. The survey findings are summarised below:

- Most farmers either own their land or use clan lands.

- The wealthiest farmers were the healthiest, better-educated and had diversified incomes, independent of other biological, geographical or socioeconomic factors.

- The strongest negative correlations with cocoa production were low levels of education, chronic ill health and physical afflictions and these families tended to live in relative poverty.

- Intensification of cocoa farming makes diversification possible.

- Wealthier farmers grew an average of 2.8 other crops while poorer farmers grew an average of only 2.0 other crops.

- Regardless of wealth many farmers grew coconuts, bananas and betel nut but these crops did not obviously contribute to wealth, perhaps suggesting they are consumed rather than sold.

- A strong correlation exists between ownership of livestock (pigs and chickens) and wealth.

These data support our recommendation to integrate farmer health service delivery with agronomic and family farm teams training. We now have strong evidence that improving farmer health will also increase cocoa production in Bougainville, and the wealth of rural smallholder communities. Cocoa farming communities face hardships in a number of areas, particularly in access to safe water sources and sanitation. While a majority of the population attended a community school only 14 per cent received a high school education and only four per cent attained tertiary education. Only one third have a bank account but over half owned a mobile phone. Around 42 per cent of the population reported moderate to severe food insecurity.

The report to the government separately reports on men’s and women’s health.

- More than a quarter of the male population and 14 per cent of women had been treated for malaria in hospital within the last six months.

- Both men and women reported that the main reasons for seeking health care in the last six months related to symptoms of cough and fever.

- Both sexes reported symptoms of a range of chronic conditions that were undiagnosed and untreated.

- While nearly all women received antenatal care from a nurse, most did not present for their first appointment until after the first trimester.

- Routine antenatal tests were variable, with over half being tested for HIV during pregnancy.

- One-quarter of women described their last pregnancy as unwanted; 11 per cent were currently using family planning methods.

- Sixty per cent of children were reported to have a registered birth certificate.

- Nearly 100 per cent of mothers reported breastfeeding their baby in the first day.

- Almost one quarter of children in the age group 12–23 months had not received any vaccinations.

- Over one-third of the children in our survey under the age of five years needed to access health care in the 12 months before the survey.

- A significant 58 per cent of children under five years were found to have stunting, with 19 per cent being severely stunted.

- Over a third of children under the age of five years were found to be underweight (513) and almost a fifth wasted (237).

The prevalence levels reported for stunting, wasting and being underweight are considered to be very high, based on the World Health Organization cut off values for public health significance.1 While a large proportion of stunting is across all regions, the South bears a slightly higher burden.

The data are continuing to be analysed and priority areas identified in consultation with the Bougainville government. Anthropometric data were collected for under-fives including weight, height and circumference of the middle arm and head. Similar data were obtained for mothers.

The survey provides vital information about livelihoods, including demographics, socioeconomic factors, cocoa markets, health, nutritional status, agriculture and more. Hubs are being established with hub managers employed in each of the three regions.

The main challenge facing the project related to combining health and agriculture. Agricultural aid projects, until this one, did not include a health component. Careful explanation of One Health concepts and the relationship between nutrition, health and productivity as well as strong support from the research team for maintaining the health and nutrition components eventually saw the funding authority embrace the benefits of such a multidisciplinary approach.

In 2019 The Australia Indonesia Centre funded a pilot study of the Village Livelihood Program.

Acknowledgements

This six-year, 6-million-dollar project is funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (2016–22).

Case study 2: Sustainability and profitability of cocoa-based farming systems in Indonesia

Merrilyn Walton, David Guest, Peter McMahon, Nunung Nuryartono, Grant Vinning, Jenny-Ann Toribio, Kim-Yen Phan-Thien, Sudirman Nasir, Andiimam Arundhana and Dian Sidik Arsyad

Partners

University of Sydney (School of Life and Environmental Sciences & School of Public Health)

Institut Pertanian Bogor (International Center for Applied Finance and Economics)

Hasanuddin University Faculty of Public Health

The problem being addressed

Improving the productivity of the Indonesian cocoa industry is a high priority within the national agricultural policy portfolio. The multiple causes of the significant drop in production since 2011 include price volatility and uncertainty, limited financial literacy, labour shortages resulting from outside employment, poor farmer health and nutrition, outmoded farm management (over 85 per cent of farmers are smallholders utilising non-intensive and poor management practices), ageing cocoa trees and the depletion of soil nutrients (forest rent). Because these farmers harvest cocoa worth only around US$600 annually at current prices (IPB survey data, Neilson, Palinrungi, Muhammad and Fauziah 2011), farmers often supplement their income by undertaking work off-farm, and cultivate crops with higher short-term returns.

Indonesian cocoa production since the 1980s has been dominated by an unsustainable boom in smallholder plantings in Sulawesi and a parallel decline in productivity as forest rent becomes exhausted (Table 7.1; Ruf 1987; Akiyama and Nishio 1996).

| Decade | Average % growth of cocoa planting area | Average % growth of productivity |

|---|---|---|

| 1967–1975 | 0.045 | 0.138 |

| 1976–1985 | 0.192 | 0.055 |

| 1985–1995 | 0.222 | 0.038 |

| 1996–2005 | 0.073 | 0.037 |

| 2005–2015 | 0.040 | -0.041 |

Table 7.1. Per cent increases in cocoa planting area and productivity for each decade between 1967 and 2015. Source: Unpublished data from Nuryartono and Khumaida (2016)

Aims and objectives

This 18-month project examined opportunities to improve the profitability of cocoa farming in Indonesia and was funded by the Australia–Indonesia Centre (AIC). Included in the project was a critical evaluation of existing and past activities, such as the US$450 million GERNAS-Kakao program (2009–2014), constraints to technology adoption and opportunities for diversification, value chain development, and de-commoditised marketing.

Objective 1

- A comparative analysis between Australia, PNG and Indonesia to understand the constraints and opportunities facing cocoa-based value chains in order to support management and policy recommendations to lift farmer and value chain productivity and profitability.

- A comprehensive review of the literature on farmer livelihoods, diets and health, incomes from crops and livestock, inclusion of women and youth, local and global industry trends, government policy impacts (including GERNAS and the cocoa export tax), and opportunities for adding value through processing and diversification, and improving the efficiency of value chains. Similar data from other countries in the region (Australia and PNG) was obtained to enable comparative analysis, particularly in relation to the impacts of health and diet on agricultural productivity.

- Baseline livelihood surveys and interviews of cocoa farmers and stakeholders to identify constraints and opportunities for diversified value chains to improve the sustainability and profitability of cocoa-based farming systems. Profitability, wellbeing and resilience of communities participating in the following can be compared:

- diversification programs, e.g. cocoa and goat mixed farming

- agricultural improvement programs, e.g. cocoa fertiliser trials

- professionalisation programs, e.g. Mars Cocoa Development Centre program and Mondelez International Cocoa Life program.

Objective 2

- Investigate constraints and opportunities to incorporating small livestock such as goats for compost production, meat, kids and milk at the Mapili demonstration site

- Compare the economic viability of fermented vs unfermented cocoa

- Compare the economic viability of the industrialisation of cocoa production in Indonesia and Australia

- Identify opportunities for satellite businesses and micro-entrepreneurship resulting from diversification

- Identify opportunities for the employment of youth and women resulting from diversification.

Objective 3

- Conduct a baseline survey of health status in cocoa-producing villages

- Develop programs to improve access to better nutrition and maternal health

- Develop a training package for Village Healthy Living Advocates.

Getting the right team together

The team comprised agricultural, food and veterinary scientists, economists and public health practitioners. The team members had each worked previously with at least one member of the team, but this was the first time they all worked together on the same interdisciplinary project.

Engaging with communities

Prior to the study several members of the team held community consultations with the cocoa-farming communities in Sulawesi to ascertain their concerns about cocoa production and health. The study site at Polewali Mandar was chosen because farmers in this area have been exposed to over 30 government and NGO development projects over the past decade, including a series of ACIAR projects involving members of the current team (Hafid and McKenzie 2012). The main healthcare concerns villagers experienced included: respiratory tract infections, tuberculosis diagnosis and management, type 2 diabetes, lack of antenatal services, lack of women’s health services, and poor understanding of sanitation and public health.

In addition, the late presentation of children with fever to a health service is not uncommon as parents typically treat their children with traditional medicines. They seek healthcare when there are signs of severe fever (dehydration and reduced consciousness) but the delayed treatment often impacts on the effectiveness of medical interventions.

Healthcare facilities include the Pustu (Puskesmas Pembantu; village level health centre), which provides perinatal and midwifery services free of charge. The Pustu is also equipped to treat fevers with paracetamol and respiratory infections with co-trimoxazole. Vaccination of the population using the national PPI program is also coordinated by the Pustu. The Puskemas (Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat; sub-district level health centre) provide more advanced services including reviews by medical staff, basic emergency care, dentistry and basic laboratory facilities. First-line TB treatment is coordinated by the Puskesmas. Both facilities identify training as a significant issue.

Funding

Prior to receiving funding from the Australia–Indonesia Centre in 2016 the research team had previously applied for funding from many national and international funding bodies (2013–2015) unsuccessfully. The most common response was that our holistic approach extended beyond the disciplinary mandate of the funding agency, and may overlap with other programs.

Method

Our mixed methods project provided quantitative data as well as contextual information (qualitative) as both are necessary to address the concerns of local communities. The objectives were:

- A literature review to highlight issues affecting the cocoa value chain within Indonesia, including export relations with key importers and strategies adopted by other cocoa producers.

- Key informant interviews (KII) with government health, livestock and agricultural extension staff, international cocoa companies and other stakeholders concerned with cocoa sustainability in Indonesia using semi-structured guidelines.

- An analysis of the impact of the cocoa export tax on the value chain and farmer prices based on published reports and interviews with local cocoa processors and government staff.

- Two village surveys based on household interviews, which provided baseline data on health and economic livelihood in communities dependent on cocoa in Polewali Mandar District, a major centre of cocoa production.

- Development of a Livelihood Curriculum based on survey data and KII to provide guidelines for training village health volunteers and cocoa/farm management volunteers.

- A cost-benefit analysis of a working mixed farm in a case study of farm diversification, including a trial to reduce kid pre-weaning deaths (by a Sydney Masters candidate).

- Further project studies based on the village surveys on financial knowledge, technical efficiency, effect of consumption and farming practice on rural carbon footprints and nutritional awareness and behaviour (by Masters and fourth-year students).

- Two studies on consumer perceptions of niche chocolate and the possibilities for a market for single origin chocolate using sensory flavour evaluation and chemical analysis (by a Sydney-based Honours student).

- Workshop presentations on project findings to government stakeholders and the Cocoa Sustainability Partnership to obtain feedback and develop recommendations arising from the project.

Village surveys

The Livelihood questionnaire developed for the ARoB (previous case study) was used to capture baseline data for this project. Baseline data were collected from four cocoa-farming villages in the subdistricts of Mapilli and Anreapi, Polewali Mandar District, West Sulawesi Province. Villages dependent on raw cocoa bean sales for community livelihoods were selected for purposive sampling. Half were regarded as either relatively remote while the remainder had easier access to nearby town centres. Households were selected randomly but were excluded if their main income source was not cocoa. Household members were interviewed to elucidate their main livelihood and health issues, access to health services and constraints to productivity. Responses were recorded on tablets. Anthropometric data were collected for under-fives including, weight, height and circumference of the middle arm and head. Similar data was obtained for mothers. A further survey of the same four villages using a comprehensive (open) questionnaire provided more details on economic livelihood and further data for Masters project studies. For these individual studies students developed their own questionnaires.

In addition to the systematic literature review on livelihoods, crops, livestock and health for selected cocoa-farming communities in Sulawesi, we analysed the status of the Indonesian cocoa industry, value chains, fermentation, processing, livestock enterprises as well as diet and main health indicators for the farmer population. We also reviewed the indicators of human nutrition and health as constraints to rural labour productivity in Indonesia and Australia, including associations between dietary quality (nutritional adequacy and dominance of high-mycotoxin risk foods), health and impact on livelihoods.

The introduction of mixed cocoa/goat enterprises potentially present an additional source of microbial contamination. This requires consideration in respect to the composting of manures, proximity to water sources, and contamination of cocoa or other crops (e.g. vegetables), as well as hand hygiene practices.

Data obtained from baseline and follow-up interviews on livelihoods and community health included measures for the following:

- Farm-level cocoa-farming practices

- Farm-level cocoa bean fermentation and drying

- Industry-level cocoa bean fermentation and drying and processing

- Farm-level cocoa, goat and food crop production

- Market for cocoa, goats and food crops

- Household-level labour productivity and availability, cocoa production levels and income sourced from cocoa production

- Household diets

- Household sanitary practices

- Extent of stunting and under- and over-nutrition

- Household-level sick days lost to productivity and school attendance

- Impact analysis will be applied by using econometric modelling to measure different observed variables between communities.

From the literature review, surveys and interviews we identified and evaluated a number of opportunities and interventions for cocoa-farming diversification.

Outcomes

Cocoa farm productivity, and as a consequence family farm livelihood, has been declining due to a complex set of factors. Far from becoming the largest cocoa producer globally (a goal set by the government of Indonesia), Indonesia could soon fall from its current position as the third largest cocoa producer. The majority of smallholder farmers produced 400 kg or less dry beans per year on their 1 ha farms and relied on cocoa as their sole source of farm income (Neilson et al. 2011, IPB). Thus, their income from cocoa is approximately $600 annually, and farmers need to undertake off-farm employment or plant alternative crops to support their families. Because farmers spend less time managing their cocoa, this workload is neglected, delegated to women (adding to their workloads and feminising agriculture), or left to less experienced youth.

We have identified market uncertainty, poor financial literacy, ageing farmer populations, poor rural health and nutrition as reasons for declining investment in cocoa. This project has explored approaches to improve livelihoods by integrating farming systems (reducing costs) and providing supplementary sources of income, sustainable production practices, including pest and disease management, connecting market demands and improved quality and pricing recommendations to reduce income uncertainty.

A value chain study conducted under this project at IPB indicated that price uncertainty influenced farmers and acted as a deterrent to capital and labour investments. In addition, land ownership was a key factor in access to finance, and certificates of ownership encouraged youth engagement.

We are working closely with health authorities to improve the focus and delivery of health services for smallholder cocoa farmers. The project has identified significant gaps in:

- health extension, particularly in knowledge underpinning key recommended practices

- eye and mental health

- early detection of infections, especially in children

- malnutrition

- how to address increasing incidence of non-communicable disease.

A curriculum for a village volunteer livelihood program was completed. A similar curriculum for cocoa/farm management was developed. The framework of the curriculum, which consists of different training modules, was discussed in detail with district health staff in November 2017 and 2018 during visits to Polewali Mandar by the Sydney team and staff from Hasanuddin University. The curriculum is based on key areas of farming and healthcare: preventive healthcare, infectious diseases, medication, eye health, nutrition, family planning and health promotion, and outlines practical activities at the village level to address these. The main targets of the program are village volunteers (known as kadre) who assist the government midwives based in most villages. Interviews conducted with current volunteers showed a high level of commitment, but a lack of training and knowledge regarding the causes of various health problems. The village volunteer livelihood program is being converted to a mobile phone application (mobile phone is the main form of distance communication in rural areas). Further funding from the Australia–Indonesia Centre has been obtained to pilot the Village volunteer livelihood program.

Summary of results

- Price volatility was a major deterrent to farmer investments in agricultural inputs and management practices.

- Fluctuations in international price were transmitted directly to farmer and domestic prices and, additionally, price variation was greater at the farmer level, demonstrating that investments by farmers bear higher risks than downstream players.

- Increased production requires intensification as new land for expansion of cocoa planting is restricted.

- Numerous training programs have increased farmer knowledge on Good Agriculture Practice (GAP), but the implementation of this training is limited by lack of capital for investment into planting material, fertilisers and extra labour to apply management strategies.

- Youth are not attracted to cocoa farming.

- Access to formal finance is a key constraint.

- Smallholders may use available funds to purchase new planting material but expenditure on chemical inputs and labour to intensify cocoa production is negligible.

- Technical efficiency scores are low.

- The study demonstrated access to finance is improved by financial literacy.

- Household income was higher on farms that had diversified into other crops.

- Evaluation of a mixed farm (cocoa/goat) model based demonstrated efficient use of resources and favourable cost/benefit ratios. (However, this requires capital to establish goat herd and shed, and access to capital is limited).

- The study found that premiums for fermented beans are inadequate as large trader/processors import fermented beans and source unfermented beans in Indonesia for cocoa butter and powder.

Health findings

- Health constraints to productivity were demonstrated in Polewali-Mandar, supporting the WHO-DALY estimates of substantial losses in labour productivity due to poor health and nutrition.

- Key health issues detected were:

- high blood pressure (34.5 per cent of a subsample of adult males; 30 per cent reported by the District Health office for pregnant mothers, higher than the national average)

- undernutrition (26.3 per cent) and malnutrition (23.7 per cent) in young children, high rates of adult obesity (31.4 per cent in females and 24.1 per cent in males)

- joint pain (24.8 per cent in women and 30.1 per cent in men).

- high rates of blurred vision (19.1 per cent in women and 33.1 per cent in men)

- over 80 per cent of both genders had never had an eye examination

- few resources are available for mental health patients

- a high proportion of households accessed open or unprotected water sources and either lacked or had only shared access to, a latrine

- dietary diversity (especially important for young children) was low and daily consumption of vegetables was only 53.4 per cent in adult males

- gender roles are separated on cocoa farms and women generally do not attend training programs, yet they performed key roles in harvesting, drying and selling to collectors.

The results of the survey in regard to health and nutrition were similar to results from other similar surveys of cocoa farmers in Ethiopia, Cote d’ Ivoire and Bougainville.

The research has also identified priority areas for further research which will be discussed with the cocoa-farming communities.

Acknowledgement

This 18-month project was funded by the Australia–Indonesia Centre (2016–18).

Case study 3: Salmonella Brandenburg – a One Health team approach to controlling an emerging animal and human pathogen

Stan Fenwick

Identifying the problem to be addressed

Prior to 1996, Salmonella outbreaks were recorded sporadically in sheep flocks in New Zealand (NZ), causing significant economic losses due to diarrhoea, abortions and deaths, with S. Typhimurium and S. Hindmarsh the principal serovars involved. Factors involved with outbreaks included periods of high stocking density, inclement weather and poor husbandry. A killed trivalent vaccine released in the 1980s (Salvexin, Schering-Plough; containing S. Typhimurium, S. Hindmarsh and S. Bovismorbificans) had been developed to control the disease in sheep and cattle, and this was widely used by sheep farmers in the country.

The situation changed in 1996 when a sheep farm in Mid Canterbury, in the South Island of NZ, experienced an outbreak of abortions and deaths in pregnant ewes. From that first farm, epidemics of abortions and deaths spread to other nearby farms in 1997 and by 1998 south to Otago and Southland, linked to the transport of sheep for grazing between drought-affected Canterbury and the southern provinces. Typically, around 5 per cent of ewes aborted on affected farms. Salmonella Brandenburg (SB), a previously uncommon isolate recovered from sporadic infections in NZ sheep, was identified as the causative organism. At the peak of the epidemic, from 1999 to 2001, over 900 farms and thousands of sheep were affected across the three regions. Economic losses were estimated at around $10,000 per farm per year. During the epidemic, sporadic cases were also seen in cattle and other animals, including cats, dogs, deer, goats, pigs, poultry, wild birds and horses. While sporadic cases were seen regularly in cattle during the epidemic peak, outbreaks in cattle gradually became more common in Southland, a primary dairy area, causing significant economic losses. Outbreaks mostly occurred in late winter to early spring, when management practices prior to the lambing period, and adverse environmental conditions, contributed to high levels of contamination and ease of transmission. Outbreak peaks appeared to be cyclical, with the highest number of affected farms in 1999–2000, and smaller peaks in 2005 and 2010. The cyclic five-year pattern was thought to be due to waning flock immunity. The disease has now become endemic in the lower South Island but interestingly has rarely been seen in other sheep farming regions of the country. Sporadic cases have been reported in the North Island, principally in veal calves, but the organism has not become established.

In addition to the effect on farm animals, SB also became an important direct zoonosis with well-defined occupational risks, which indirectly affected family members. Prior to 1996, SB was an infrequent human pathogen in NZ (around 25 cases of food poisoning per year), but a marked increase in human cases was recorded in 1998 (134 cases per year) and remained high during the epidemic years. Human cases peaked during the lambing and calving periods, from September to November, coincident with animal outbreaks. Typically, Salmonella infections in NZ peak in the late summer months and are largely food-borne. From 1998–2002 over 550 SB cases were notified in affected regions, approximately a fifth of the total Salmonella isolations from the southern South Island. Many rural workers, including veterinarians and their families, were affected. Salmonella Brandenburg became the predominant isolate at Southland hospital from 1997, with many isolations from extra-intestinal sites indicating invasive disease.

Getting the right team together

The evolution of a One Health team to combat the disease began gradually, with different members and stakeholders joining the outbreak response team over the first 1–2 years, adopting many different roles. Initially the disease was predominantly a sheep issue and the team thus involved farmers and large animal veterinary practitioners from affected areas, and veterinarians and laboratory scientists from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) regional centres in Canterbury and Otago. Once the organism responsible for the disease had been identified as Salmonella, scientists at the Ministry of Health (MOH) enteric reference group at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) were involved in serotyping of the isolates. Coincidentally, staff from the microbiology laboratory at the Institute of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences (IVABS), Massey University, became involved in molecular typing of isolates from animals at this stage and developed close links with CDC, sharing information over the next few years. Massey’s involvement came about as a result of prior professional linkages with Schering-Plough, the veterinary pharmaceutical company responsible for the development and marketing of Salvexin, the original Salmonella vaccine sold in NZ.

Once the outbreaks had been confirmed as salmonellosis, farmers who were concerned that the vaccine they were using had somehow become ineffective initially criticised Schering-Plough. After the strain had been defined as SB, however, it was acknowledged by the scientific community that cross-immunity to the outbreak strain from the killed vaccine was lacking and that the only possible solution was to include the new strain in a multivalent vaccine. This is usually a long and formidable process involving significant R&D efforts, including small-scale efficacy and safety trials, government approval, scaling up to commercial vaccine production, product registration, marketing etc.; however, the severity of the outbreak and its effect on both humans and animals launched an unprecedented, multidisciplinary campaign to fast-track the procedures. From the outset, Schering-Plough worked closely with scientists and veterinarians from Massey University and MAFF, and also with private practitioners from affected areas, to conduct research into the efficacy of a vaccine including SB antigens. Initial experiments were performed in mice, and subsequently in sheep, and the results were encouraging enough to involve rapid commercialisation and field trials. Salvexin-B was approved and launched in 2000, 3–4 years after the initial cases had appeared.

In parallel with the multidisciplinary approach to combat the animal disease, the concomitant increase in human infections resulted in the team expanding to include members of the medical profession. Medical laboratory scientists, doctors, public health workers and epidemiologists from the hospitals, health departments and laboratories in the affected areas, and from central government, were all involved, interacting closely with their animal health and industry colleagues. This rapid and successful embracing of a One Health approach to this new disease may have been facilitated in NZ due to the prior efforts of a very farsighted epidemiologist from Massey University, Professor David Blackmore, who at least 10 years earlier had persuaded two key ministries (MOH and MAFF) to co-fund the Veterinary Human Health Advisory Group (VHHAG) to convene and share information on zoonotic diseases in the country on a regular basis. The group included representatives from many stakeholder groups involved in detection, prevention, control and research into key zoonoses in NZ, and its genesis was inspired by high levels of leptospirosis and brucellosis affecting employees in the animal industries. This body helped to smooth the way for quick and efficient collaboration and information sharing across disciplines in response to the outbreak.

Following the initial outbreak response, members of the team expanded to include scientists researching many other aspects of the disease, from microbiology to field epidemiology. Central government also became involved in research efforts due to the knock-on effect that the disease had on NZ sheep meat exports. Reports from Spain that SB had been found in NZ sheep meat resulted in several countries in Europe placing a temporary ban on imports, with severe economic ramifications for the NZ sheep industry, including farmers, abattoirs and meat exporters. A large quantitative risk analysis (QRA) was performed to examine the safety of NZ sheep meat in order to provide information to persuade overseas governments to revoke the ban. The QRA, which examined the microbiological risks from farm to carcass, involved a strong multidisciplinary effort including laboratory and field staff from MAFF and IVABS, veterinary practitioners, farmers and abattoir workers.

Other major research efforts involved identification of risk factors for spread of the disease, and environmental scientists and wildlife biologists from the Department of Conservation became important partners. Results of the research provided strong evidence for the role of wild birds in transmission between farms, principally black-backed seagulls scavenging on aborted foetuses and dead sheep, and also for contamination of waterways linking farms by birds and pasture runoff. Examination of seagull gut contents revealed very high levels of Salmonella carriage with no signs of illness.

Importantly, examination of isolates from all affected regions, and from multiple animal species and humans by the Massey IVABS group, in collaboration with the enteric reference laboratory at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), showed that the Salmonella Brandenburg outbreak strain was clonal and very stable, i.e. all strains were identical using DNA fingerprinting technology and the fingerprint of the outbreak strain did not alter over many years. Looking retrospectively at historical SB isolates from a collection of CDC showed that the clone was markedly different from previous isolates of the serotype from food-borne infections prior to the outbreak. This encouraged intense speculation on the source of the novel strain (e.g. overseas travellers, sewage, seagulls, migratory birds) as well as providing justification for inclusion of the outbreak strain in the newly developed vaccine.

It is important to note that, throughout the outbreak years, research results continued to be shared rapidly between sectors and they were used to support the development of appropriate control measures and to provide advice to farmers and other stakeholders to limit the spread of the disease and the risk of human infections.

Engaging with communities

One Health is a movement that emphasises the importance of collaboaration by multiple disciplines to solve complex health problems, and response to this outbreak was distinguished by the strong co-operation of many sectors, including public and private sectors and local communities. Communication about the outbreak, its cause, risk factors and prevention and control measures took place at multiple levels during the first year of the outbreak. Most importantly, considerable efforts were made by multidisciplinary teams to engage directly with affected communities, especially farmers, veterinary and medical practitioners and other stakeholders. The outbreak peaked between 1998 and 1999 in the southern South Island provinces of Otago and Southland, and the scale of the problem affecting sheep farming communities led to rapid appeals for assistance from the veterinary profession, the pharmaceutical industry and the government. Schering-Plough responded quickly by providing financial support for multidisciplinary teams, including government, university and private practice veterinarians and government and private medical practitioners and microbiologists, to travel to affected areas to hold a series of town hall meetings to deliver information about the disease. Several hundred affected farmers attended the meetings and many heart-breaking stories of farms and families seriously affected by the disease were recounted. Despite limited information in the early stages of the outbreak, the different disciplines in the team provided relevant information on the origins of the disease, how the disease had progressed south from Canterbury, how it was being spread locally, how people were likely becoming infected and appropriate biosecurity, hygiene and management measures required to limit animal and zoonotic transmission. While the mood of the meetings was often tense, with particular concern about the lack of protection provided by Salvexin, local farmers and veterinarians were on the whole very pleased at the rapid response by the multiple sectors.

Following the meetings, numerous visits were also made to local veterinary practices to discuss control measures and risk factors in more detail so that the best advice could be provided to clients. At least three key veterinary practices were involved with the team and over the following months provided regular updates to agricultural communities via newsletters and farm visits. Further meetings by the OH team were held over the first couple of years to discuss new knowledge from research, to report progress on development of a new vaccine and finally to launch the new vaccine and to discuss its efficacy and usage. By engaging the community early in the piece, considerable goodwill was developed, and farmers rapidly adopted recommended control measures with some success.

In addition to communities, communication with other stakeholders, including government agencies, meat industry leaders and the veterinary and medical professions, was achieved by meetings, conferences, journal papers and media announcements. Engaging with the media early in the outbreak was an important task, as sharing relevant scientific information prevented innuendo and supposition and encouraged responsible journalism; in effect local newspaper journalists also became de facto members of the outbreak response team.

Funding the project

As this was a very complex outbreak involving multiple stakeholders, funding came from a number of different sources and for many different pieces of the puzzle. After the initial outbreak had been investigated by government agencies, Schering-Plough put a considerable amount of funding into veterinary practices to investigate the disease on individual farms and to support meetings to communicate findings with farmers and veterinarians in the affected regions. They also funded a substantial amount of research into many aspects of the disease. Although they were a commercial pharmaceutical company, the senior management in NZ felt a sense of social responsibility to the farmers and veterinary practices that had been their clients for many years, in particular as they were the only company promoting a Salmonella vaccine in NZ.

Once a decision had been made by the company to include SB in the Salvexin vaccine (and this involved a lot of technical meetings and discussions on feasibility and costs), Schering-Plough invested a large amount of money to fund the vital research to develop and test the vaccine. This research was performed at Massey University in the North Island of NZ where good facilities existed for the series of experiments that needed to be conducted in mice and sheep to assess efficacy and safety and to provide data for product registration. Costs of the research were significant, in particular because the experiments had to be carried out following very strict biosecurity standards in order to avoid release of SB into the environment, with subsequent risk of spread to sheep producing regions outside the affected zones.

Recognising the importance of the disease for the economy and human health, the NZ government provided funding for research into the epidemiology of the disease, in particular the work to define the risk factors for maintenance and transmission of the organism. Once issues had arisen over the finding of SB in exports of sheep meat, the government also funded the large and complex QRA designed to provide information to importing countries on product safety.

Veterinary practices and Massey University also provided funding, through research grant allocation, and in-kind contributions. Although this was on a smaller scale and largely invisible, a number of university scientists, and veterinary practitioners in the affected regions, put a considerable amount of time and effort into working with farmers impacted by the disease, often pro bono, and with a sense of social responsibility to the communities they worked in.

Methods used

As might be imagined, over the course of the initial years of the outbreak a large number of methods were used to define and investigate the problem. At the outset, these were largely microbiological and epidemiological; however, later molecular biological methods, risk analysis, behaviour change communication, animal experimentation, pathology and environmental science methodologies were used to elucidate different aspects of the disease.

Outcomes and legacy

The outcomes of the One Health collaboration were perhaps slow to develop, but given the scale of the problem and the human, animal and environmental factors at play, this was understandable. Due to the efforts of a number of key team members, farmers put in place effective control measures that gradually resulted in the decline of the outbreak. Farmers’ awareness of the issues was raised considerably by the strong emphasis that the team placed on communication, and this paid dividends as flock management strategies were changed to combat the disease and human cases dropped. Improving farm management and biosecurity had obvious flow-on benefits for the control of other endemic diseases, and this too could be considered a very good outcome.

Obviously one tangible legacy was the development of an improved, effective vaccine that could be used to control the disease, although the vaccine alone was not sufficient, and many other good management practices needed to be adopted by farmers. The combined efforts required to bring the vaccine to commercialisation showed that, in a crisis, working together is vital, and kudos must go to the many people involved in the process.

Although the disease had severe economic effects for many farmers, it also helped to strengthen community bonds in affected areas, by bringing together all the stakeholders and giving each of them a voice. This was a major outcome of the successful One Health approach that was quickly and efficiently put into effect following the outbreak and involving communities from the beginning helped to break down barriers that might have previously existed between professions and the many people affected by the disease.

In conclusion, the disease was not eradicated completely and Salmonella Brandenburg has become endemic, with limited numbers of cases seen each year in sheep and cattle. On the bright side, the disease has been contained to the lower South Island, and farmers have learned to live with the situation and to take effective measures to respond to cases as they arise. This was probably the largest outbreak of Salmonella recorded in animals worldwide and only the success of the prompt and efficient One Health response, involving multiple sectors and disciplines, prevented it from spreading to other sheep-rearing regions of New Zealand and probably globally.

Case study 4: The role of tradition in Aboriginal wellbeing

Paul Memmott

This chapter is catalysed by the continuing lack of success2 in addressing the multifaceted disadvantage within modern Australian Aboriginal communities despite many policy shifts and goals, the most recent being the national ‘Closing the Gap’ policy. This disadvantage is reflected in the statistical measures and key performance indicators (KPIs) of modern neoliberal government bureaucracy such as life expectancy, incidence of life threatening diseases and risks (e.g. foetal alcohol syndrome, kidney failure, heart disease), child development vulnerability, mental health, unemployment, household crowding, substance abuse, self-injury, suicide, family violence (multiple forms), Indigenous crime rates, imprisonment, homelessness, school dropout etc. The constant framing of Aboriginal wellbeing in deficit values reflecting national standards of citizen status and conditionality, and the failure to view the circumstances from an Aboriginal leadership and cultural perspective, tends to mask, even drown, the positive attributes within Aboriginal societies and communities that can act as a community-driven platform from which to contribute strong social capital to address these issues.

Thus, this chapter attempts to model a good-practice case study on how an Aboriginal agency can establish, evolve and grow incrementally without sacrificing its independence, integrity and vision and drawing selectively on Aboriginal cultural traditions and values as drivers within the modern intercultural context of Australian society. This is despite the tendency for successive governments to impose top–down, ‘we-know-best’ policies that stifle grassroots, community-driven approaches. Government resources and short-term problem-solving processes are inadequate to readily solve interconnected labyrinths of health, social, economic and psychological problems; a more holistic sustainable approach that is community-value driven and community-owned is required. This quandary can be partly informed by accurate understanding of Aboriginal contact history processes for specific groups and regions, and how over many decades such histories have generated longitudinal problems within Aboriginal families and societies with successive dysfunctional enculturations in descending generations that become increasingly difficult to arrest and reverse. For example, underlying the historical problems in this case study region from 1860 include disease, massacres, slave labour (30 years), decimation, taking of country, total life control (from 1898 until the mid-1970s) under the Aboriginal Acts, poor nutrition, removal to penal settlements, breakdown of social leadership cohesion and values, indentured labour for 75 years, which eventually reversed to widespread unemployment and welfare benefit dependency in the early 1970s.

Contemporary good-practice Aboriginal agencies are vexed by constantly changing governments and policies as well as inter-family and inter-group Aboriginal politics (forms of lateral violence) driven by the competition for scarce resources, rival Native Title claims and subsequent monetary distributions by developers to self-forwarding traditional owners, and inherent family nepotism mitigating against collective advancement. Thus, the way politics of tradition are operationalised may be either positive or negative towards social wellbeing and unfortunately, as witnessed by those in the Native Title industry, the latter outcome is all too common.

A recurring problem for government and Aboriginal agencies alike is where to intervene in this labyrinth. Housing, health and leadership have each been suggested as a priority. Referred to as the ‘Aboriginal problem wheel’ since the early 1970s, this challenge continues to vex. This case study I present has particular cultural, regional and economic contexts, but it is only one path among many simultaneously occurring in other Australian local contexts. The aim is to distil good-practice principles that can be applied and tested across the continent. Knowledge of this case study draws from action research, the author (an anthropologist and transdisciplinary researcher) having had multiple roles in the case-study agency since, and even before, its establishment.

The Indjilandji-Dhidhanu case study

This case study3 starts with an extended family of Indjilandji-Dhidhanu people (‘Indjilandji’ for short) from the upper Georgina River basin, who have a commitment to Aboriginal identity and connection to tribal land and the opportunity to gain recognition for such through Native Title. They recognised that their strategic political expression of tradition could drive economic opportunity through the advantageous leverage off ILUAs (Indigenous Land Use Agreements) under the Native Title Act.

However, the commitment to Aboriginality was not something easily understood given the nature of colonial violence and oppression in the region since 1861. In preparing the historic-anthropological analysis for the Federal Court (Memmott 2010a), it became apparent that only one extant clan of Indjilandji-Dhidhanu people remained on country out of an estimate of 12 or so clans who were present at the time of arrival of the first colonial exploring party led by William Landsborough from the Gulf of Carpentaria (arriving December 1861). What happened to the other 11 clans? There was a complex history, initially violent during the first 60 years with the advent of the Native Mounted Police, but becoming more submissive for most of the 20th century primarily because of the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of Sale of Opium Act 1897. This Act was administered by local police who instigated punitive removal of those who resisted compliance with its indentured labour requirements.

The single Indilandji clan group who managed to both survive and remain (with cultural connections) on country for 150 years, working as labourers and stock hands within the pastoral industry, became identified in the Federal Court proceedings as the Idaya Descent Group having descended from their ancestor Idaya who was alive when the first Europeans rode onto the Georgina basin at the start of the wet season in 1861 (the party of explorer William Landsborough). Idaya’s great-great-grandson Colin Saltmere, a former Head Stockman and ATSIC Councillor, led the first self-funded Native Title claim in Australia (as opposed to government-funded through the National Native Title Tribunal). This strong sense of bush self-reliance and a life of stock-camp work ethic, combined with customary beliefs in Aboriginal Law, were basic ingredients in the development of the group’s enterprise endeavour and practice style.

At the outset of their claim process (early 2000s), two significant regional economic opportunities arose in the Indjalandji country that provided income from ILUA agreements between the traditional owners and the development proponents. One was a proposed phosphate mine. The other was a state government upgrade of the Barkly Highway starting with a new bridge over the Georgina River at the border town of Camooweal. The ILUA agreement with the miner paid the professional fees to continue the Native Title claim, while the agreement with the Main Roads Department delivered a prefab donga work camp with dining room, kitchen, laundry, bore and electricity connection for an Aboriginal labour team. The mine never went ahead but the camp was named the Dugalunji Camp and became a base for successive road-building contracts. The Myuma Corporation gradually upskilled its team, recycled profits into plant purchase and a road-metal quarry and expanded its capital base. A strong partnership was established with Main Roads such that successive contracts for regional remote road maintenance are ongoing.

However, the Myuma Group (as it came to be known, with three constituent corporations soon established) understood the fickle nature of remote economies and diversified its forms of economic activity to establish a ‘hybrid’ economy (after Altman 2007) – see Box 7.2. One of the most successful enterprises is the establishment of a pre-vocational training scheme for young Aboriginal adults whereby industry groups, especially mining, pre-pay for up to 30 trainees at a time to undergo a 12 to 15-week course to prepare them for employment with a capacity to sustain themselves in the rigours of working life. (Many skills have to be included from basic construction tasks, to obtaining driving and plant licences, writing a CV, and workplace safety.)

Box 7.2: The Hybrid Economy of Myuma Group (2005–18)

- Quarry products

- Road building and maintenance; road traffic control

- Road camp and mining camp village construction

- Painting and craft

- Cultural heritage clearances and inductions

- Pre-vocational training for construction and mining industries (60 to 70 trainees per year × 14 weeks). (Now 120 trainees per year × 12 weeks.)

- Prisoner workforce training

- Ranger training

- National Park management

- Fencing contracts

- Co-operative research with University of Queensland

- Remote Jobs Community Program (RJCP) – several regions in Queensland and Northern Territory

- Trade apprenticeship training

- Gas pipeline construction subcontractor.

While Myuma PL focused on making money, the second corporation, the Dugalunji Corporation, specialised in land management and cultural activities stemming from a strong customary ethic of caring for country. A Ranger Group was eventually formed and trained to provide land-care services on the Georgina basin. The Myuma Group’s profits were recycled into building and expanding its Dugalunji Camp as well as allocations for regional charitable causes through its third corporation, Rainbow Gateway. Eventually, Rainbow Gateway became the vehicle for taking on the federal government regional contract of running the work-for-dole employment schemes (CDEP followed by RJCP).4 At the time of writing, the Myuma Group had a turnover of over $15 million per annum from its various activities.

My context as researcher-author in this ethnographical essay

This summary history of the Myuma Group does not do justice to the complex evolution of this good-practice service delivery agency which is Aboriginal-owned, managed and majority staffed. The participation of white professionals to date has always been part of its commercial success story and the author is one of those persons. I commenced pure research in the region in the early 1970s, and after completing my PhD (which was a crossover from architecture into anthropology) established my own research consultancy in the early 1980s which was always dependent upon land claims and Native Title claims for income. In the early 2000s I was the expert anthropologist witness for the Indilandji-Dhidhanu claim as well as carrying out cultural heritage consultancies for the group; it brought lasting relationships with individuals covering three generations of the Idaya Descent Group. With the encouragement of Myuma leader Colin Saltmere we started a process of conceptual incubation which included my establishing cultural workshops in the pre-vocational courses that can number up to four courses per year. This led me into a role as the Dugalunji Camp anthropologist visiting Camooweal every month or two, enabling me to become a participant observer as applied in anthropological methodology. I became immersed into the Dugalunji Camp life seeking to understand what made it successful from the point of view of camp managers, the workers, and trainees.

Publications resulted from efforts to record and understand how Myuma’s success story has unfolded (e.g. Memmott 2012). This case study analyses the three workshops regularly conducted for each group of trainees. Unpacking the curriculum which was heavily influenced by the needs of the Dugalunji Camp shows the relationship between the employment and the wellbeing of Aboriginal people in the camp. The curriculum today mirrors the camp’s philosophy of integration of Aboriginal beliefs with the spiritual nature of country, psychological and social health of the workers and their connection to a sustainable workforce in the mainstream Australian economy. The potential for an empowering way out of the horrible circumstances of third or fourth generation welfare dependency that many of the incoming trainees have experienced becomes real.

The Dugalunji Camp training courses5

A trainee in the Dugalunji Camp may find themselves in a mixed-gender class of up to 30 individuals of whom some may come from that trainee’s own home town or community, may even be related and/or with shared cultural understandings, while others come from elsewhere with diverse personalities and backgrounds. The one predictable feature is the shared sense of their Aboriginality, but how it manifests will vary. Senior training staff need to appreciate all Aboriginal/Islander cultural regions of Queensland and the types of cultural change processes they have experienced. The psychology and cultural make-up of a Wik trainee from Aurukun will be different from a rural town trainee from Western Queensland towns such as Dajarra or Boulia, and they in turn will be different again to a trainee from south-east Queensland towns such as Caboolture or Ipswich, or to a rainforest person from the Atherton Tableland. There remain recurring class or workshop occasions/compositions when all manner of such juxtapositions of diverse individuals occur. Because heterogeneity also reflects workplace environments, this situational context is a useful scenario in which to explore diverse worker values and behaviours and how to make sense of and develop personal operational capacity and team skills within such diverse settings.

In mid-2013, non-Aboriginal staff realised during a Myuma trainers’ evaluation workshop that family violence experiences were the norm for the majority of trainees. Physical fights, strong abuse, attempted and actual suicides and sexual trauma were common experiences (true to the national statistical measures of these problems). This reflects the embeddedness of personal psychological and social dysfunction among many Aboriginal families and requires historical models of cultural change to understand the origin of this phenomenon, as well as explain it to the trainees so as to sensitise them to their personal and family problems. Creating a vision of opportunity for them to liberate themselves and their families from it to some extent is the goal; but at the very least to show them how their family problems may undermine their employment and the need to build up their personal resilience.