4

Climate scepticism in Australia and in international perspective

The 2016 State of the Climate report produced by the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO states that ‘Global average annual carbon dioxide (CO2) levels are steadily increasing’ and that ‘Australia’s climate has warmed in both mean surface air temperature and surrounding sea surface temperature by around 1°C since 1910’. While the rate of planetary warming remains a topic of scientific interest, estimates of the proportion of climate scientists who agree that anthropogenic climate change is occurring range between 90 and 100 per cent (Powell 2015; Cook et al. 2013; Anderegg et al. 2010; Doran and Zimmerman 2009; Oreskes 2004). A recent survey of climate researchers found that 97 per cent of published climate scientists agreed global warming has mainly anthropogenic causes (Cook et al. 2016). In Australia, the Climate Institute (2016) found that 77 per cent of Australians believe that climate change is happening, a figure that has been steadily increasing from 64 per cent in 2012. The Climate Institute (2016) also found that 60 per cent of Australians agree with the statement, ‘I trust in the science that suggests the climate is changing due to human activities’ – again, an increase from 46 per cent in 2013.

However, a substantial minority of people in many countries, including Australia, appear to disagree with the scientific consensus over the veracity and implications of climate change (Tranter and Booth 2015), while many tend to ‘overestimate the numbers of people who reject the existence of climate change’ (Leviston et al. 2013, 334). Although the proportion who reject climate change outright is relatively small (as we will see below), sceptics comprise a disproportionately vocal minority of the population in many Western nations. Opponents of the scientific consensus tend to ‘exaggerate the actual degree of uncertainty in the scientific community or imply that uncertainly justifies inaction’ (Lewandowsky et al. 2015). Such approaches have been labelled ‘scientific certainty argumentation methods’ or SCAMs (Freudenburg et al. 2008).

While trust in climate science appears to be increasing (Climate Institute 2016), deep political divisions persist over the existence of climate change and the way that Australia should respond (Tranter 2011, 2013; Tranter and Booth 2015; Fielding et al 2012). The political divide in Australia in many ways resembles that in the United States (e.g. Wood and Vedlitz 2007; Jacques et al. 2008; McCright and Dunlap 2011; Hamilton 2011), where large differences of opinion over climate change are extant between Republicans and Democrats, with the former more likely to reject anthropogenic climate change. For example, Hamilton et al. (2015, 6) found that trust in climate science in the US ‘is highest among Democrats and lowest among Tea Party supporters’, while among American conservatives, trust in science has declined since the mid-1970s (Gauchat 2012), and climate change has become increasingly polarised politically (e.g. Kahan et al. 2012). Divisions over climate change are not due to different levels of general scientific knowledge among climate supporters and detractors (Kahan 2015). Rather, in the US (and I suspect also in Australia), political polarisation over scientific findings arises when issues challenge particular worldviews (such as valorising free markets), but is absent when they do not (Kahan 2015; Lewandowsky et al. 2016). When it comes to attitudes on climate change in the US, political polarisation actually increases with higher levels of self-reported knowledge and education (Hamilton 2011; Hamilton et al. 2015), with political conservatives less accepting of climate change as their education level and knowledge of climate change increases, while liberals become more accepting.

In Australia, the influence of political partisanship is also strong and reflects the cues of party leaders and the policy positions of the major parties (Tranter 2013). The Australian Greens and to a lesser extent the Australian Labor Party support stronger action on climate change, while the Liberal–National Coalition’s ‘Direct Action’ policy aims to provide incentives for industry to reduce emissions, in order to meet the 2020 target of reducing emissions by 5 per cent below 2000 levels. The direct action policy replaces the previous Labor government’s carbon pricing scheme, often referred to as the ‘carbon tax’. The Coalition’s direct action scheme has been criticised as ineffective. When Kumarasiri, Jubb and Houghton (2016) interviewed senior managers of ‘carbon-intensive listed companies’, they found ‘Direct Action was not as effective as a carbon tax in driving companies to act urgently and manage emissions’.

Climate scepticism in Australia

While the aim in this chapter is to examine levels of climate scepticism, it is important to recognise that climate sceptics are not a homogenous group (Poortinga et al. 2011). Some reject the notion of anthropogenic climate change altogether, arguing that while the planet may be warming, climatic changes are natural fluctuations that have occurred for millennia. Matthews (2015, 158) suggest these ‘strong sceptics’ may also ‘express the opinion that climate activists or climate scientists are in some way dishonest or fraudulent’. For Hobson and Niemeyer (2013) this outright rejection of climate science is an example of ‘deep scepticism’ while it has also attracted the label ‘climate change denial’ (e.g. Armitage 2005; Jacques et al. 2008; Dunlap and McCright 2010).

Other sceptics agree that anthropogenic climate change is occurring, but that the rate of warming is far slower than most climate scientists claim. For Matthews (2015, 157), these are ‘lukewarmers’, who ‘accept that human emissions of carbon dioxide have warmed the planet significantly and will continue to do so in the future. However, they believe that the level of warming will be lower than that predicted by many climate scientists, and that the global warming scare has been exaggerated.’ Matthews (2015, 158) also identifies ‘moderate sceptics’ who are ‘characterised by views that warming of the climate is not a problem, that a large proportion of past warming is due to natural processes, that the threat posed by climate change has been greatly exaggerated . . .’

The term ‘neosceptic’ has also emerged to describe those who, while not outright sceptics, are nonetheless opposed to policy options to limit anthropogenic climate change (Stern et al. 2016; Perkins 2015). Stern et al. (2016) found that climate change sceptics ‘offered a changing set of arguments – denying or questioning ACC’s [anthropogenic climate change] existence, magnitude, and rate of progress, the risks it presents, the integrity of climate scientists, and the value of mitigation efforts’. As McCright and Dunlap (2010, 111) argue in relation to climate scepticism in the US: ‘Activists in the American conservative movement have obfuscated, mis-represented, manipulated and suppressed the results of climate science research’.

When provided with a list of 12 environmental concerns and asked how urgent these were for Australia, 63 per cent of respondents to the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA) 2013 rated climate change as urgent, well below issues such as marine conservation, the destruction of wildlife, waste disposal, pollution, soil degradation and the logging of forests (Blunsdon 2016a).1 Yet, when asked to rank the same 12 environmental issues in terms of how much they worried people in the past 12 months, climate change emerged as the most urgent environmental issue (Tranter and Lester 2015). While climate change may be a major environmental concern to many Australians, how do their attitudes compare to the citizens of other advanced industrialised countries? In this chapter, survey data from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) is examined so that the level of climate change scepticism among Australians can be compared to scepticism in other advanced industrialised countries. Data from AuSSA 2014 is then drawn upon to consider Australians’ knowledge of climate change, and to determine important social, political and attitudinal correlates of climate scepticism in Australia.

Major influences on attitudes to climate change

In Australia, as in many other countries, climate change attitudes have been shown to be associated with various social characteristics. These include gender, age, education, and worldviews (e.g. McCright and Dunlap 2011a; Hamilton 2010; Whitmarsh 2011; Tranter 2011). In the US, McCright and Dunlap (2011b) have shown ‘conservative white males’ to be more likely than others to hold sceptical positions, while in the United Kingdom sceptics are more likely to be men, to be aged over 65, to be right-of-centre, and to hold individualistic worldviews (Whitmarsh 2011). Unlike the pattern of gender differences in general scientific knowledge (Hayes 2001), McCright (2010) found that women in the US have both higher knowledge of climate change, and are more concerned about it than men are, but that women are more likely than men to underestimate their knowledge. Having low trust in governments is also associated with climate scepticism (Lorenzoni and Pidgeon 2006; Dietz et al. 2007; Tranter and Booth 2015), while in Australia, people living in rural locations tend to view politicians, government and the media as untrustworthy sources on climate change (Buys et al. 2014).

Surprisingly, Lewandowsky and Oberauer (2016, 217) argue that ‘General education and scientific literacy do not mitigate rejection of science, but, rather, increase the polarisation of opinions along partisan lines’. Sceptics are claimed to assimilate information on climate change in a biased manner, with Corner et al. (2012, 463) finding newspaper editorials are evaluated differently based upon whether people accept or reject anthropogenic climate change. Strong sceptical views on climate change also tend to become entrenched (Hobson and Niemeyer 2013), suggesting that such beliefs are not easily swayed by evidence presented by climate scientists. Although as Whitmarsh (2011, 699) found, while ‘more information will not engage the most sceptical groups, since information will tend to be interpreted in relation to existing views, and entrenched views are very hard to change. For non-sceptical and ambivalent groups . . . climate change communication – which is currently characterised by an over-reliance on hype and alarmism – can be improved’.

Attitudes on climate change vary according to the competing worldviews and values that underpin them. As Lewandowsky and Oberauer (2016, 217) put it, ‘People tend to reject findings that threaten their core beliefs or worldview’. In contrast to ‘collectivists’, ‘individualistic’ worldviews are associated with rejection of anthropogenic climate change and policies to attenuate its impacts, because of perceived restrictions such action would impose upon commerce and industry (Kahan et al. 2012). In a somewhat similar vein, McCright and Dunlap (2010) posit the ‘anti-reflexivity thesis’ – that is ‘a perspective that attributes conservatives’ (and Republicans’) denial of anthropogenic climate change (ACC) and other environmental problems and attacks on climate/environmental science to their staunch commitment to protecting the current system of economic production’ (Dunlap 2014). As McCright, Dentzman, Charters and Dietz (2013) put it, the ‘Anti-Reflexivity Thesis expects that conservatives will report significantly less trust in, and support for, science that identifies environmental and public health impacts of economic production . . . than liberals.’ In the analyses that follow, I assess the influence of political ideology and political partisanship upon knowledge of climate change and attitudes toward anthropogenic climate change in Australia.

Australian attitudes on climate change – recent national and comparative data

The main focus here is on climate change attitudes and climate scepticism in Australia. I first consider how sceptical of climate change Australians are compared to the citizens of 13 other advanced industrialised countries, then focus upon the Australian case, modelling different aspects of climate scepticism. In addition to developing a profile of the social and political background of climate sceptics, I evaluate the importance of the following as predictors of climate scepticism: respondent worldviews, value orientations, trust in government and interpersonal trust, and general concern about environmental issues.

The data analysed here are from two sources, the 2010 International Social Survey Programme’s Environment Module (ISSP Research Group 2012), and the 2014 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA; Blunsdon 2016b). Few cross-national studies examine climate scepticism. One important reason for this is that cross-national examination of climate scepticism requires appropriate international survey data. The ISSP administered the third wave of their Environment Module surveys in 2010, and in that survey a question on climate change was included for the first time. The ISSP question is: ‘In general, do you think that a rise in the world’s temperature caused by climate change is . . . extremely dangerous for the environment, very dangerous, somewhat dangerous, not very dangerous, or, not dangerous at all for the environment?’

For the purpose of the analyses here, climate sceptics are defined as those who respond that climate change is not very dangerous, or not dangerous at all for the environment. The ISSP survey allows cross-national comparisons to be made on climate change, although the survey does not specifically refer to human-induced (anthropogenic) climate change. Unfortunately, many surveys do not measure climate scepticism in a precise manner. For example, many do not refer to anthropogenic climate change, and as mentioned above, the vast majority of peer-reviewed climate scientists suggest that global climate change is mainly caused by anthropogenic global warming (Cook et al. 2016). The ISSP question is therefore an imprecise measure of the concept, but is a useful proxy measure of climate change for cross-national comparative purposes, because in everyday language ‘climate change’ tends to be associated with anthropogenic climate change. For a more detailed discussion of the ISSP questions see Tranter and Booth (2015).

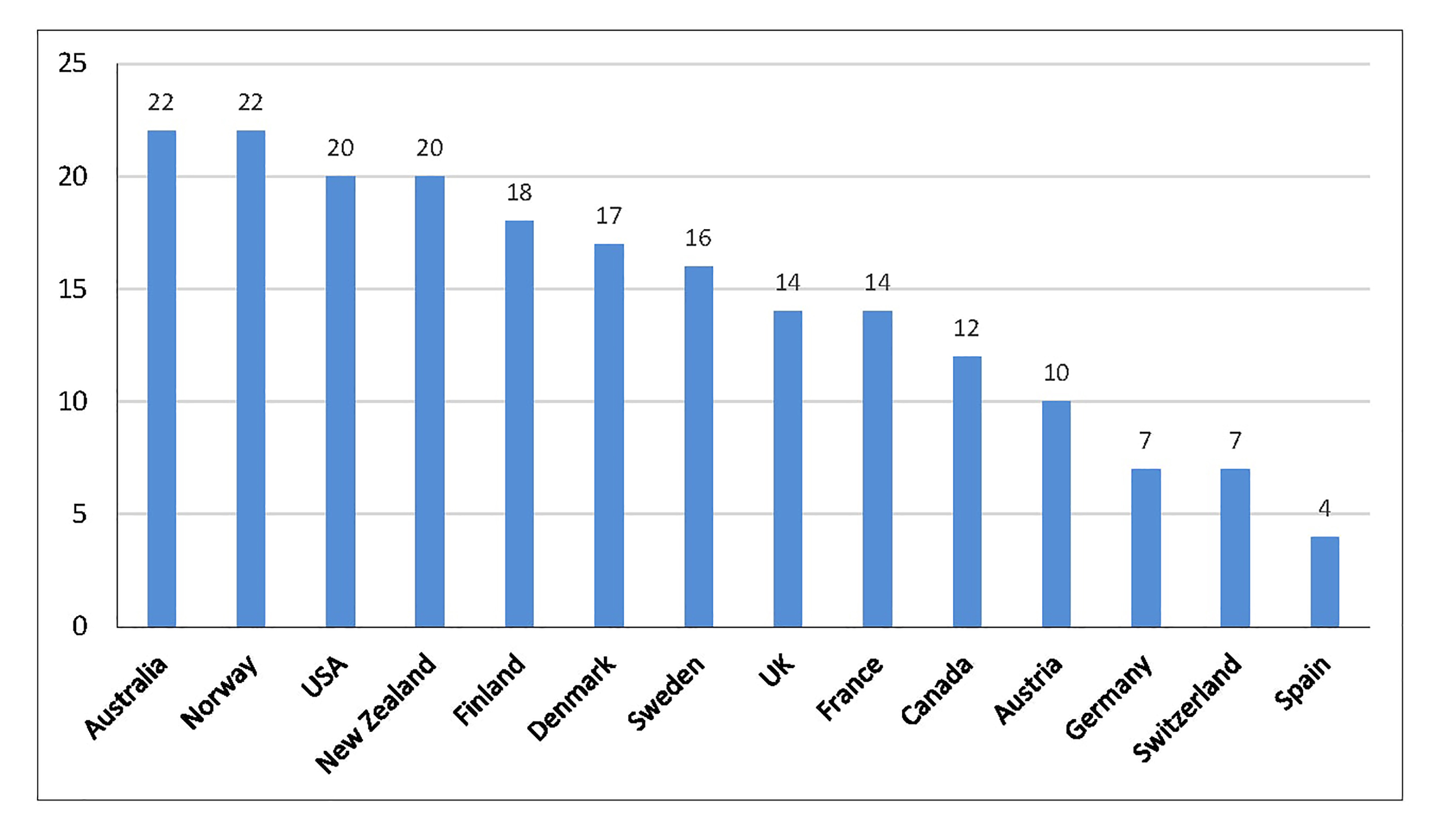

Figure 4.1 Respondents who believe that climate change is ‘not very dangerous’, or ‘not dangerous at all’ for the environment, %.

Source: International Social Survey Programme 2010.

Given the limitations of the ISSP data, I also examine items included in AuSSA 2014, that enable a more detailed examination of climate change attitudes. The AuSSA questions were designed specifically to measure attitudes to anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic climate change, and outright rejection of climate change, among a nationally representative sample of Australian adults.2 Several questions from the AuSSA are used to examine climate change attitudes. The following first taps aspects of climate scepticism: ‘Which of the following statements do you personally believe? 1. Climate change is happening now, and is caused mainly by human activities; 2. Climate change is happening now, but is caused mainly by natural forces; 3. Climate change is not happening now; 4. I don’t know whether climate change is happening or not.’

AuSSA 2014 also contains a question that measures what respondents believe about the consensus position among scientists: ‘Which of the following statements do you think is more accurate? 1. Most scientists agree that climate change is happening now, caused mainly by human activities. 2. There is little agreement among scientists that climate change is happening now, caused mainly by human activities.’ The third question asks respondents about their knowledge of climate change: ‘How much do you feel that you understand about climate change – would you say a great deal, a moderate amount, only a little, or nothing at all? 1. A great deal. 2. A moderate amount. 3. Only a little. 4. Nothing at all.’

The advantage of the AuSSA questions is that they clearly distinguish between the consensus position of climate scientists (i.e. that climate change is mainly anthropogenic), and two sceptical positions: outright rejection of climate change, and a rejection of the scientific consensus in favour of climate change that is naturally occurring. The AuSSA questions replicate survey items administered by Hamilton (2011) and Hamilton et al. (2015) in the US and therefore facilitate a comparison of attitudes in the two countries, as US data on these questions were also collected in 2014. In the next section I examine how Australia sits relative to other countries on climate scepticism, and consider how social background and other potential predictors are associated with sceptical climate change attitudes, before focusing more closely upon analysing climate scepticism in the Australian case.

Australian climate scepticism in comparative perspective

The ISSP results in Figure 4.1 show the responses of Australians and the citizens of 13 other countries on the dangers of climate change for the environment. Based upon these results, the proportion of Australians who do not see climate change as dangerous for the environment is 22 per cent, equal with Norway and a slightly larger proportion than that for New Zealanders and Americans. While Australians and Norwegians are very sceptical of climate change relative to other advanced countries, scepticism is relatively low among the citizens of Spain, Germany, Switzerland and Austria. These results situate Australia internationally, but we can learn more about the cross-national profile of climate sceptics by exploring their socio-demographic and political backgrounds. For example, to what extent does gender or political party allegiance shape the climate change attitudes of Australians compared to those of the citizens of other advanced countries?

Several predictors of sceptical attitudes have been operationalised drawing upon the social science literature on climate change. Table 4.1 shows the results of regression analyses (expressed as odds ratios)3 for the 14 ISSP countries, modelling the social and political background of those who not believe that a rise in the world’s temperature caused by climate change is dangerous for the environment. In other words, these results allow a comparison of the background characteristics and attitudinal dispositions of ‘climate sceptics’ across the 14 countries.

Table 4.1: Climate change sceptics in international perspective (odds ratios).

| Australia | Austria | Canada | Denmark | Finland | France | Germany | NZ | Norway | Spain | Sweden | Switz. | UK | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 1.5** | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.7** | 1.9*** | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.6** | 1.5* | 1.8** | 2.4*** | 1.7* | 1.6* | 1.1 |

| Aged 65+ | 1.3* | 1.3 | 0.93 | 1.6* | 2.1*** | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.9*** | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Degree | 0.6*** | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.6* | 1.4 | 0.6* | 1.1 | 0.5* | 1.1 |

| Live in large city | 0.7* | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.01 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.7* | 0.8 | 0.5** | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Non-religious | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.6* | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.6* |

| Postmaterial (+ Post) | 1.07 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 1.13 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 1.32 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 0.91 | 1.55** |

| Party left–right (+ right) | 1.87*** | 1.14 | 1.85*** | 1.69*** | 1.37* | 1.12 | 1.39* | 1.54*** | 1.63*** | 1.22 | 1.22 | 0.99 | 1.51** | 1.70*** |

| Distrusts government | 1.3* | 0.6* | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.6** | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4* | 1.5* | 1.6* | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.7* | 1.5* |

| Science solves envir. probs. | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.5* | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.5* |

| Unconcerned about envir. | 4.7*** | 2.7*** | 8.4*** | 1.5* | 4.6*** | 2.2*** | 2.3** | 3.7*** | 5.1*** | 2.3** | 6.0*** | 3.9*** | 7.9*** | 3.9*** |

| Solution to envir. problems | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.56 | 0.8 | 1.4* | 0.9 | 0.99 | 1.4* | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.98 | 1.2 | 0.98 | 1.02 |

| Private enterprise | 1.5** | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.5* | 1.2 | 1.5** | 1.2 | 1.4* | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7* | 1.04 | 2.6*** |

| Reduce income inequality | 0.6*** | 1.03 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.04 | 0.7** | 0.6* | 0.7* | 0.9 | 0.5** | 0.9 | 0.99 | 1.1 | 0.4*** |

| Nagelkerke R2 | .25 | .09 | .19 | .13 | .17 | .06 | .05 | .16 | .24 | .08 | .24 | .07 | .24 | .27 |

| N | 1,841 | 971 | 945 | 1,160 | 1,141 | 2,119 | 1,323 | 1,092 | 1,291 | 2,416 | 1,086 | 1,191 | 847 | 1,325 |

Source: ISSP 2010.

Notes: * p< .05; ** p< .01 *** p< .001. Dependent variable ‘Climate Change Sceptics’ =0; or 1 if ‘a rise in the world’s temperature caused by climate change is . . . not dangerous or not dangerous at all for the environment’.

Comparing each independent variable (i.e. each row) across the countries, it is apparent that certain variables have a consistent and statistically significant influence on scepticism (at 95 per cent confidence). Men are more likely than women are to be sceptical about a dangerously warming climate in nine of the 14 countries, including Australia. Age is a less consistent predictor, but where the results are statistically significant, older people tend to be more sceptical than their younger counterparts. However, age is only a notable correlate for results in Australia, Denmark, Finland, and New Zealand. Tertiary educated people are less likely than others to be sceptical of a warming climate, but once again, this only holds for Australia and three other countries.

Postmaterial values also predict environmental concern in Western countries (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Postmaterialists tend to prioritise quality of life issues such as the environment, to a greater extent than materialists. The latter are more likely to be concerned with economic growth and national security (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). In general, we might expect postmaterialists to be less sceptical than materialists. However, as can be seen in Table 4.1, this measure has no impact upon climate scepticism with the exception of the US, where postmaterialists are actually more sceptical than materialists.

A far more consistent predictor is the party left–right variable. The ISSP researchers placed respondents on a left–right scale based upon expert classification of the political party they identified with. As previous studies found in countries such as the US and Australia (e.g. McCright and Dunlap 2011a, Tranter 2011), the results show that supporters of right-wing parties are far more likely than left party supporters to be climate sceptics in nine countries. The size of the odds ratios shown in Table 4.1 suggests that the impact of the left–right scale is even stronger for Australia than the US. Low trust in government is added as a potential predictor of scepticism (Lorenzoni and Pidgeon 2006, 85). The question asks ‘[M]ost of the time we can trust people in government to do what is right’. Agree and Strongly agree responses are contrasted with other responses. Having low trust in government is associated with scepticism in eight countries, although Austrians who distrust government are the exception here, as they are less likely to be sceptical of climate change.

Another measure included in the models in Table 4.1 are beliefs in the power of scientific solutions to environmental problems. This variable measures agreement or strong agreement with the statement ‘Modern science will solve our environmental problems with little change to our way of life’. Higher confidence in scientific answers to environmental problems was expected to be associated with lower climate scepticism, but has minimal impact in these results. The item ‘How much do you feel you know about solutions to these sorts of environmental problems?’ serves as a measure of self-assessed knowledge of environmental problems. The 5-point response scale ranges from ‘Know nothing at all’ (1) to ‘Know a great deal’ (5). High knowledge is measured here as answering 4 and 5 on the scale, yet once again, it is not an important predictor of climate scepticism. Higher knowledge is modelled with the expectation that understanding how to solve environmental problems should be associated with less concern about climate change. However, the results for this variable are inconclusive, with only two countries showing statistically significant results.

Two indicators from the ISSP data are also included in the models in Table 4.1 as proxies for citizen ‘worldviews’ (Kahan et al. 2012). These are ‘Private enterprise is the best way to solve [country’s] economic problems’ and ‘It is the responsibility of the government to reduce the differences in income between people with high incomes and those with low incomes’ (5-point scales from Strongly agree to Strongly disagree). Strong agreement and agreement are contrasted with other responses for each question. The expectation is that ‘individualistic’ worldviews (i.e. those who disagree with governments redistributing income) and those who believe in the importance of private enterprise should be more sceptical than others. The results provide some evidence that ‘individualists’ are more sceptical than ‘collectivists’ on climate change among six of the 14 countries for each measure.

Low concern for environmental issues has been found to predict environmental scepticism (Engels et al. 2013). Environment concern is derived from the question ‘Generally speaking, how concerned are you about environmental issues?’ (Responses: 1=Not at all concerned to 5=Very concerned), with low levels of concern represented by response options 1 and 2 on the scale. In fact, being unconcerned about the environment is by far the most consistent and strongest correlate of climate scepticism. Low environmental concern is aligned with climate scepticism in all 14 countries, even after statistically adjusting for social and political background and other factors modelled here. While this finding does not necessarily mean that climate sceptics are also anti-environmentalists (Tranter and Booth 2015), this consistent cross-national finding is certainly worthy of further research.

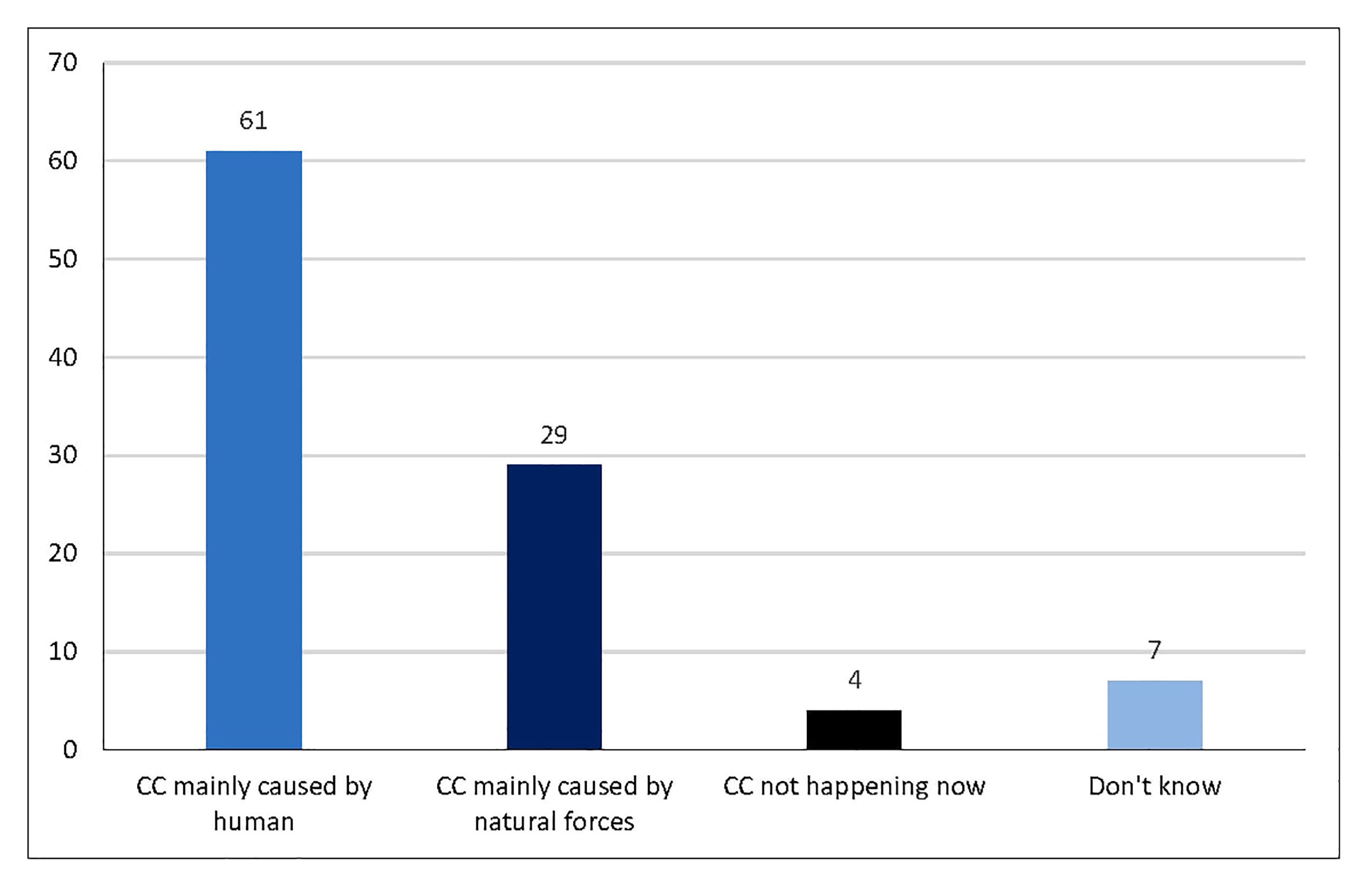

Figure 4.2 Australian views about the causes of climate change, %.

N=1,435. Source: Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA) 2014.

Exploring climate scepticism among Australians

While the ISSP data are somewhat limited for modelling the complexity of climate change scepticism, data from the AuSSA 2014 enable a more detailed analysis of climate change attitudes among Australian adults. According to AuSSA, 61 per cent of Australians believe that climate change is occurring and is mainly caused by human activities, while 29 per cent believe climate change is happening, but is caused mainly by ‘natural forces’ (Figure 4.2). Only a very small minority of Australians completely reject the notion of climate change (4 per cent) while the remaining 7 per cent claim that they don’t know whether it is happening or not. The Australian results can be compared with data from the US based upon the same survey question in 2014. Hamilton et al. (2015) found that 53 per cent of Americans believe in anthropogenic climate change (even less than the 61 per cent of Australians), although the proportion of Americans claiming climate change to be ‘natural’ was very close to the Australian estimate at 31 per cent (Hamilton et al. 2015).

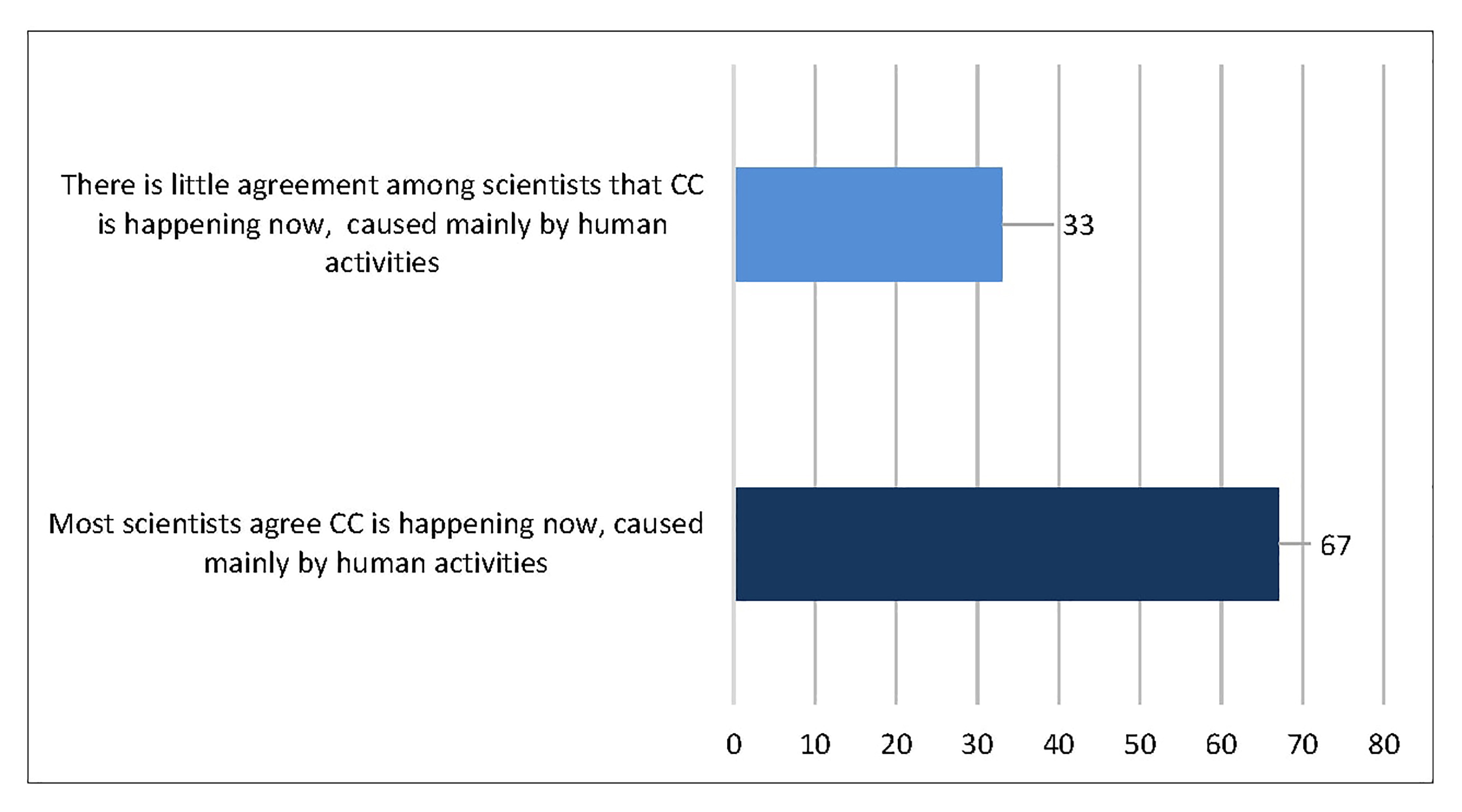

Figure 4.3 Australian attitudes about the degree of scientific consensus about climate change, %.

N=1,435. Source: AuSSA 2014.

Figure 4.3 shows that two thirds of Australians believe most scientists agree that climate change is happening now, and has mainly anthropogenic causes. This still leaves a large minority who are unaware of the consensus position of climate scientists (Cook et al. 2016). However, if researchers such as Cook and Lewandowsky (2016) are correct, such responses are not necessarily irrational rejections of the scientific consensus.

To what extent do social and political background characteristics differentiate climate change attitudes in Australia? To model these associations, regression analysis is again used to examine several dependent variables in Tables 4.2 and 4.3. Table 4.2 models the background characteristics and political orientations of self-assessed knowledge of climate change, while in Table 4.3, three outcomes are considered. Those who reject climate change outright are compared to all other responses, then Australians who believe that climate change has mainly natural causes are compared with people who accept that climate change is mainly human-induced. The third dependent variable in Table 4.3 models Australians’ views of scientific agreement on anthropogenic climate change.

Turning first to the results in Table 4.2, it is clear that men are more likely than women to claim higher knowledge of climate change in Australia. This is consistent with McCright (2010), who found women more likely than men to understate their knowledge of climate change, although this hypothesis cannot be directly assessed because actual measures of climate change knowledge were not included in AuSSA 2014. However, the gender, age and education findings here are similar to those found using quiz questions on political processes and institutions (McAllister 1998; Tranter 2007). Given that climate change is a highly politicised issue in Australia, it is likely to be an aspect of ‘political knowledge’ more generally. Neither trust in government nor interpersonal trust have an impact on self-assessed climate knowledge. However, accessing news from commercial sources is associated with lower levels of knowledge, as is Coalition party identification. The politically non-aligned are also less knowledgeable on climate change than Greens or Labor identifiers, or at least they believe they are less knowledgeable.

Table 4.2: Self-assessed knowledge of climate change.

| Social background | (odds ratios) |

| Men | 1.9*** |

| Aged 65+ | 1.4* |

| Degree | 1.8*** |

| Live in large city | 0.98 |

| Attitudes | |

| Non-trusting of government | 1.2 |

| Non-trusting of people | 1.1 |

| News from . . . | |

| Commercial TV/radio | 0.6*** |

| Newspapers | 0.6*** |

| Political orientations | |

| Left–right (0–10) | 0.97 |

| Coalition party ID | 0.6** |

| No party ID | 0.5*** |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.12 |

| N | 1,341 |

Source: AuSSA 2014.

Notes: * p< .05; ** p< .01 *** p< .001.

Given that only a small proportion of respondents completely reject the notion of climate change, the resulting sub-sample is small and only strong associations are statistically significant at the 95 per cent level for the first dependent variable (Table 4.3). Those who claim to know ‘nothing at all’ about climate change are far more likely to claim that it is not occurring at all. Source of news is again a factor here, with reliance upon commercial TV or radio news associated with complete rejection of climate change. Identifying with the Liberal–National Coalition parties, or having no party affiliation, is also associated with outright rejection of climate change.

People who tend to reject climate change outright are unlikely to have their views swayed on the subject, even in the face of evidence from expert sources. Hobson and Niemeyer (2013, 408) found ‘public climate change communication strategies or interventions can unintentionally alienate such individuals further’. Given that only 4 per cent of the AuSSA sample claim climate change is not occurring, arguably of far greater importance is the relatively large proportion of people who believe that climate change is occurring due to ‘natural forces’. Some researchers suggest that such views may be shifted by the presentation of scientific evidence (e.g. Hobson and Niemeyer 2013) or exposure to the consensus view of climate scientists (e.g. Lewandowsky and Oberauer 2016). The relatively large proportion of Australians who agree that climate change is occurring mainly because of ‘natural forces’ is therefore more interesting from a policy perspective, as citizens with such views, at least in principle, may be more likely to shift with the provision of information or cues from political leaders (Tranter 2013).

Table 4.3: What predicts climate scepticism among Australians? (odds ratios).

| No climate change | Natural CC vs ACC | Scientists do not agree on ACC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social background | |||

| Men | 1.8 | 1.6*** | 1.2 |

| Aged 65+ | 1.1 | 1.7*** | 1.7*** |

| Degree | 0.6 | 0.6** | 0.7* |

| Live in large city | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Attitudes | |||

| Low self-assessed knowledge of CC | 5.6** | 0.99 | 3.9*** |

| Non-trusting of government | 2.2 | 0.8 | 0.96 |

| Non-trusting of people | 1.3 | 2.4** | 1.5 |

| News from . . . | |||

| Commercial TV/radio | 2.2* | 1.9*** | 1.7*** |

| Newspapers | 1.6 | 2.1*** | 1.6* |

| Political orientations | |||

| Left–right (0–10) | 1.06 | 1.16*** | 1.15*** |

| Coalition party ID | 13.7*** | 4.0*** | 3.9*** |

| No party ID | 5.0* | 1.7** | 2.1*** |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| N | 1,323 | 1,188 | 1,314 |

Source: AuSSA 2014.

Notes: * p< .05; ** p< .01; *** p< .001. CC refers to climate change. ACC is anthropogenic climate change.

Coalition identifiers are four times as likely as Labor and Greens party identifiers to believe in ‘natural climate change’. These strong partisan results suggest that if, for example, bipartisan agreement could be reached among political leaders over appropriate approaches to addressing climate change at some time in the future, partisan attitudes may also shift. However, in practice this seems rather unlikely in the present political climate. Close to bipartisan agreement on climate change was reached in 2009 when then leader of the opposition, Malcolm Turnbull, supported then prime minister Kevin Rudd over a carbon pollution reduction scheme. Yet bipartisanship on this issue was instrumental in Turnbull’s demise as leader of the Liberal Party in December 2009. This rejection of a climate change progressive reflected not only the position of elected Liberal Party members, but a larger conservative constituency who were opposed to such action on climate change. The current, politically pragmatic approach adopted by Turnbull as prime minister (i.e. having no truck with carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes) suggests that the attitudes of conservative Australians on this issue may be difficult to sway.

Believing that climate change has mainly ‘natural’ as opposed to anthropogenic causes is also quite strongly socially anchored. Australian men are more likely than women to be believe in natural causes, as are older Australians. Tertiary education is also a factor, with graduates more likely than non-graduates to believe in anthropogenic climate change. Unlike the ISSP results discussed above, or some previous research findings (e.g. Lorenzoni and Pidgeon 2006; Dietz et al. 2007), trust, or lack of trust in government, does not tend to predict climate change attitudes for these more nuanced questions. However, interpersonal or generalised trust in others does – those who have little trust in others are around twice as likely to believe in natural, rather than anthropogenic, causes.

The source of one’s news is also a potential influence on climate change attitudes. People who mainly source their news from commercial television or radio, or newspapers, are far more likely to believe in natural rather than anthropogenic climate change. This to an extent reflects the influence of conservative elements of the Australian press. Those who believe that climate change is either not occurring at all, or that it is not caused by anthropogenic influences, may well gravitate to news outlets whose editors and journalists espouse similarly sceptical views. Bacon (2013) found that Australian newspapers such as the Herald Sun (Melbourne), the Daily Telegraph (Sydney) and the Advertiser (Adelaide) that are owned by or are subsidiaries of News Corp are most likely to ‘reject’ or ‘express doubt’ about anthropogenic climate change. Finally, in addition to the influence of Coalition party identification, a separate effect is apparent for political ideology: self-locating on the right of the political spectrum is linked to believing in natural climate change.

Comparing the impact of the independent variables upon the three dependent variables, several similarities in the direction and sizes of the effects are extant. However, one important difference is self-assessed knowledge of climate change. Low knowledge is an important predictor of rejecting climate change outright, and for the climate science dependent variable, but does not differentiate anthropogenic from ‘natural’ attitudes toward climate change. Based on these results, it seems that some Australians are comfortable in rejecting the science on climate change, while simultaneously acknowledging that they know ‘nothing at all’ about climate change.

Making sense of the climate scepticism of Australians

Australians are among the most climate sceptical of people living in advanced industrialised countries. As climate sceptics, they rank alongside Norwegians, Americans, and New Zealanders. In terms of political divisions, Australians are somewhat similar to Americans when it comes to climate scepticism. Like citizens of the US (e.g. McCright and Dunlap 2011, 2011a; Wood and Vedlitz 2007), attitudes toward climate change are deeply divided by party allegiances in Australia (Tranter 2011; Fielding et al. 2012), with National and Liberal party identifiers far more sceptical of anthropogenic climate change than Greens and Labor partisans. The politically unaligned also tend to be climate sceptics when compared to parties of the left or centre-left. This is important, as these non-partisans comprise a large proportion of Australians, around 36 per cent according to the results of AuSSA 2014. The politically unaligned seem closer to political conservatives on climate change. Like swinging voters, non-partisans may be influenced by either side of the climate debate, rather than tending to follow the cues offered by party leaders (Tranter 2013). Based on their own assessment, the politically non-aligned are less knowledgeable of climate change than those who identify with political parties, and as I have found in other analyses (not shown here), they tend to be younger than average, a known correlate of lower political knowledge (McAllister 1998; Tranter 2007). They are also located at the centre of the left–right ideology scale, while the strongest climate sceptics tend to be located on the right of the political spectrum. These factors, coupled with their lower knowledge of climate change, suggest that the views of non-partisans are not entrenched and their attitudes on climate change may potentially shift with greater knowledge of climate science.

AuSSA 2014 shows that only about 4 per cent of Australians completely reject the notion that climate change is occurring, while 29 per cent believe it is occurring but has natural causes and 7 per cent ‘don’t know’ if it is happening or not. A majority (61 per cent) believe that anthropogenic climate change is happening, which is also the consensus position of peer-reviewed climate scientists (Cook et al. 2016). Yet one third of Australians believe there is little agreement among scientists about the anthropogenic causes of climate change. One interpretation of the latter finding is that such people are simply misinformed, unaware of ‘state of the art’ climate science. However, several researchers have found that when people approach highly politicised issues such as climate change, they do so through a perceptual screen mediated by their worldviews (e.g. Kahan 2015; Lewandowsky and Oberauer 2016). It may not be lack of scientific knowledge that leads many Australians to either reject anthropogenic climate change or believe that climate change is a mainly natural phenomenon (Kahan 2015), but that the implications of acting on such issues conflict with deeply held worldviews.

As Lewandowsky and Oberauer (2016) argue, rejection of science does not necessarily occur in an irrational manner; rather, it involves a process they refer to as ‘rational denial’. For example, given the current state of development of renewable power sources, reducing CO2 emissions by imposing a carbon tax, or an emissions trading scheme on high greenhouse gas emitters (or more radically, closing coal-fired power plants) would likely drive up the cost of energy, which would not only impact upon power prices for public consumers, but also create an impost upon businesses, in turn impeding economic growth. For those who place a high value upon the free market, the imposition of government regulations to achieve lower emissions is in direct conflict with their worldviews. While one may understand the findings of climate scientists, the implication of taking action to reduce climate change can cause cognitive dissonance that results in reduced trust in climate scientists (Lewandowsky and Oberauer 2016). Cook and Lewandowsky (2016 in Lewandowsky and Oberauer 2016, 4) found that ‘participants who strongly supported free market economics lowered their acceptance of human-caused global warming in response to information about the climate consensus . . . people adjusted their trust in climate scientists downward, thereby not only avoiding an adjustment of their belief in the science but also safe-guarding their endorsement of free-market economics’.

In addition to political divisions, scepticism tends to be higher among Australian men than among women, a case resembling the ‘conservative white male’ effect in the US (McCright and Dunlap 2011b). The similarities with the US do not end there. For example, both countries have a substantial conservative mass media hostile to the consensus position on climate science. In the US, right-wing talkback radio and Rupert Murdoch-owned media outlets such as FOX News ‘consistently denigrate climate change . . . providing frequent opportunities for contrarian scientists and CTT representative to disparage climate change, the IPCC, and climate scientists’ (Dunlap and McCright 2011, 152). The editorial pages of newspapers such as the Wall Street Journal feature ‘a regular forum for climate change denial’ (Dunlap and McCright 2011, 152).

In Australia, a somewhat similar situation exists where climate sceptics are given greater media coverage relative to the consensus position of climate scientists in certain media, for example Murdoch’s News Corp-owned television, and commercial radio stations (Bacon 2013). The results presented in this chapter are supportive of such claims. Compared to those who favour public broadcasters (i.e. the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the Special Broadcasting Service), Australians who rely upon commercial TV or commercial radio for their news and information tend to reject climate change outright, to be more sceptical of the consensus position of climate scientists, or to believe that climate change has natural causes.

Changing the attitudes of at least some sceptical Australians on climate change is a precursor to changing behaviour and will provide an impetus for changes to government policy toward stronger action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This brings us to the importance of a bipartisan political stance on climate change (Donald 2017). Political agreement between the major parties is a necessary, although perhaps not sufficient condition for real change to occur. Bipartisanship needs to be accompanied by dissemination of climate science research in a way that reflects the consensus position of climate scientists who publish research in peer-reviewed journals, rather than over-representing the numerically small but extremely vocal opinions of climate sceptics who are so prominent in right-wing media (e.g. McCright and Dunlap 2011; Bacon 2013).

In experimental research, Ranney and Clark (2016) found that explaining how the greenhouse effect operates increases acceptance of climate science across the political divide. Cook and Lewandowsky (2016, 160) also found that ‘among Australians, consensus information partially neutralized the influence of worldview, with free-market supporters showing a greater increase in acceptance of human-caused global warming relative to free-market opponents’. However, importantly, the climate change message needs to be framed in a way that is compatible with the views of political and economic conservatives, yet in a way that does not challenge or conflict with their more sceptical worldviews (Kahan 2015). For example, by highlighting the economic opportunities that will accompany the growth of the renewable energy sector if this sector is encouraged to grow. These should be seen as challenges to be overcome, rather than insurmountable obstacles. The alternative, continuing on the path of inadequate action, moving too slowly to address the most important global problem, will see our wide brown land and ‘bronzed Aussies’ turn into burnt offerings on the BBQ of climate change, an outcome that Direct Action policies and even Slip, Slop, Slap will prove ineffective to prevent.

References

Anderegg, William, James Prall, Jacob Harold and Stephen Schneider (2010). Expert credibility in climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107(27), 12107–2109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003187107.

Armitage, Kevin C. (2005). State of denial: the United States and the politics of global warming. Globalisations 2(3), 417–27.

Bacon, Wendy (2013). Sceptical climate part 2: climate science in Australian newspapers. Australian Centre for Independent Journalism. https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/Sceptical-Climate-Part-2-Climate-Science-in-Australian-Newspapers.pdf.

Blunsdon, Betsy (2016a). Australian survey of social attitudes, 2013. Canberra: Australian Data Archive, Australian National University.

Blunsdon, Betsy (2016b). Australian survey of social attitudes, 2014. Canberra: Australian Data Archive, Australian National University.

Buys, L., R. Aird, K. van Megen, E. Miller and J. Sommerfeld (2014). Perceptions of climate change and trust in information providers in rural Australia. Public Understanding of Science 23(2): 170–88.

Climate Institute (2016). Climate of the nation 2016: Australian attitudes on climate change. http://www.climateinstitute.org.au/articles/publications/con-2016-report-page.html/section/478.

Cook, John and Stephan Lewandowsy (2016). Rational irrationality: Modeling climate change belief polarization using Bayesian networks. Topics in Cognitive Science 8, 160–79.

Cook, John, Naomi Oreskes, Peter Doran, William Anderegg, Bart Verheggen, Ed Maibach, J. Stuart Carlton, Stephan Lewandowsky, Andrew Skuce, Sarah Green, Dana Nuccitelli, Peter Jacobs, Mark Richardson, Bärbel Winkler, Rob Painting and Ken Rice (2016). Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters 11. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002.

Cook, John, Dana Nuccitelli, Sarah Green, Mark Richardson, Bärbel Winkler, Rob Painting, Robert Way, Peter Jacobs and Andrew Skuce (2013). Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters 8(2). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024.

Corner, Adam, Lorraine Whitmarsh and Dimitrios Xenias, D. (2012). Uncertainty, scepticism and attitudes towards climate change: Biased assimilation and attitude polarisation. Climatic Change 114, 463–78.

CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology (2016). State of the Climate. https://bit.ly/2Mt4JqD.

Dietz, Thomas, Amy Dan and Rachael Shwom (2007). Support for climate change policy: social psychological and social structural influences. Rural Sociology 72(2), 185–214.

Donald, Peta (2017). Industry, environment, community groups demand bipartisan energy policy. ABC News, 13 February. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-13/industry-groups-demand-bipartisan-energy-policy/8263928.

Doran, Peter and Maggie Zimmerman (2009). Examining the scientific consensus on climate change. EOS 90(3), 22–23.

Dunlap, Riley (2014). Clarifying anti-reflexivity: conservative opposition to impact science and scientific evidence. Environmental Research Letters 9. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/9/2/021001.

Dunlap, Riley and Aaron McCright (2011). Organized climate change denial. In The Oxford handbook of climate change and society. J. Dryzek, R. Nrgoaard, R. and D. Schlosberg, eds. New York: Oxford University Press.

Engels, Anita, Otto Hüther, Mike Schäfer and Hermann Held (2013). Public climate-change scepticism, energy preferences and political participation. Global Environmental Change 23, 1018–27.

Fielding, Kelly, Brian Head, Warren Laffan, Mark Western and Ove Hoegh-Guldberg (2012). Australian politicians’ beliefs about climate change: political partisanship and political ideology. Environmental Politics 21(5), 712–33.

Freudenburg, William, Robert Gramling and Debra Davidson (2008). Scientific certainty argumentation methods (SCAMs): science and the politics of doubt. Sociological Inquiry 78(1), 2–38.

Gauchat, Gordon (2012). Politicization of science in the public sphere: a study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review 77(2), 167–87.

Hamilton, Lawrence (2011). Do you believe the climate is changing? Carsey Institute Issue Brief No. 40. Durham: University of New Hampshire.

Hamilton, Lawrence (2010). Education, politics and opinions about climate change: evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change 104(2), 231–42. doi: 10.1007/s10584-010-9957-8.

Hamilton, Lawrence C., Joel Hartter, Mary Lemcke-Stampone, David W. Moore and Thomas G. Safford (2015). Tracking public beliefs about anthropogenic climate change. PLOS One 10(9): e0138208. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138208.

Hayes, Bernadette C. (2001). Gender, scientific knowledge, and attitudes toward the environment. Political Research Quarterly 54(3), 657–71.

Hobson, Kersty and Simon Niemeyer (2013). What sceptics believe: the effects of information and deliberation on climate change scepticism. Public Understanding of Science 22(4), 396–41.

Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel (2005). Modernization, cultural change and democracy: The human development sequence, New York: Cambridge University Press.

ISSP Research Group (2012). International Social Survey Programme: Environment III–ISSP 2010. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5500 data file version 2.0.0. doi: 10.4232/1.11418.

Jacques, Peter, Riley Dunlap and Mark Freeman (2008). The organisation of denial: conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environmental Politics 17(3), 349–85.

Kahan, Dan (2015). Climate science communication and the measurement problem. Political Psychology 32, 1–43.

Kahan, Dan, Ellen Peters, Maggie Wittlin, Paul Slovic, Lisa Ouellette, Donald Braman and Gregory Mandel (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change 2, 732–35.

Kumarasiri, Jayanthi, Christine Jubb and Keith Houghton (2016). Direct action not as motivating as carbon tax say some of Australia’s biggest emitters. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/direct-action-not-as-motivating-as-carbon-tax-say-some-of-australias-biggest-emitters-64562.

Leviston, Zoe, Iain Walker and Morwinski, S. (2013). Your opinion on climate change might not be as common as you think. Nature Climate Change 3, 334–37.

Lewandowsky, Stephan and Klaus Oberauer (2016). Motivated rejection of science. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25(4), 217–22.

Lewandowsky, Stephan, Naomi Oreskes, James Risbey, Ben Newell and Michael Smithson (2015). Seepage: Climate change denial and its effect on the scientific community. Global Environmental Change 33, 1–13.

Lorenzoni, Irene and Nick Pidgeon (2006). Public views on climate change: European and USA perspectives. Climatic Change 77(1–2), 73–95.

Matthews, Paul (2015). Why are people skeptical about climate change? Some insights from blog comments. Environmental Communication 9(2), 153–68.

McAllister, Ian (1998). Civic education and political knowledge in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science 33(1), 7–23.

McCright, Aaron (2010). The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Population and Environment 32(1), 66–87.

McCright, Aaron, Katherine Dentzman, Meghan Charters and Thomas Dietz (2013). The influence of political ideology on trust in science. Environmental Research Letters 8. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/044029.

McCright, Aaron and Riley Dunlap (2010). Anti-reflexivity. The American conservative movement’s success in undermining climate science and policy. Theory, Culture & Society 27(2–3), 100–33.

McCright, Aaron and Riley Dunlap (2011a). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. The Sociological Quarterly 52, 155–94.

McCright, Aaron and Riley Dunlap (2011b). Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change 21(4), 1163–72.

Oreskes, Naomi (2004). The scientific consensus on climate change. Science 306(5702), 1686.

Perkins, John (2015). Mitigation measures: Beware climate neo-scepticism. Nature 522(287). doi:10.1038/522287c.

Poortinga, Wouter, Alexa Spence, Lorraine Whitmarsh, Stuart Capstick and Nick Pidgeon (2011). Uncertain climate: an investigation into public scepticism about anthropocentric climate change. Global Environmental Change 21, 1015–24.

Powell, James (2015). The consensus on human-caused global warming. Skeptical Inquirer 39: 42.

Ranney, Michael and Dav Clark (2016). Climate change conceptual change: scientific information can transform attitudes. Topics in Cognitive Science 8(1), 49–75.

Stern, Paul, John Perkins, Richard Sparks and Robert Knox (2016). The challenge of climate-change neoskepticism. Science 353(6300), 653–54.

Tranter, Bruce (2007). Political knowledge and its partisan consequences. Australian Journal of Political Science 42(1), 73–88.

Tranter, Bruce (2011). Political divisions over climate change. Environmental Politics 20(1), 78–96.

Tranter, Bruce (2013). The great divide: political candidate and voter polarisation over global warming in Australia. Australian Journal of Politics and History 59(3), 397–413.

Tranter, Bruce and Kate Booth (2015). Scepticism in a changing climate: a cross-national study. Global Environmental Change 33, 154–64.

Tranter, Bruce and Libby Lester (2015). Climate patriots? Concern over climate change and other environmental issues in Australia. Public Understanding of Science. doi: 10.1177/0963662515618553.

Whitmarsh, Lorraine (2011). Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global Environmental Change 21(2), 690–700.

Wood, Dan and Arnold Vedlitz (2007). Issue definition, information processing and the politics of global warming. American Journal of Political Science 51(3), 552–68.

1 The other environmental issues were extreme weather events, biodiversity, mining, overpopulation and nuclear power.

2 AuSSA 2014 is drawn from a national sample of Australian adults administered between May 2014 and February 2015. The 2014 survey was administered by mail in four waves to a systematically drawn sample of Australian adults aged 18 and above, achieving a response rate of 31 per cent (Blunsdon 2016b). The sampling frame was the Australian Electoral Roll, with analyses based upon a sample size of 1,435 cases.

3 Odds ratios that are larger than 1 suggest the presence of a positive association between the independent and dependent variables. Odds less than 1 suggest the relationship is negative. For example, in Table 4.1, the odds for Australian men are 1.5 times that of women, and are significant at p < .01. This suggests that men are more sceptical than women that rising temperatures are dangerous for the environment.