9

Howard’s queens in Whitlam’s republic: explaining enduring support for the monarchy in Australia

Howard’s queens in Whitlam’s republic

Support for retaining the constitutional monarchy in Australia was widely seen to be in an inexorable decline (Bean 1993) but in recent years, successive Australian opinion surveys have shown increasing levels of support for the monarchy. After the unsuccessful 1999 referendum to replace the Queen with a republican style of government, Australians have warmed to the monarchy. The Australian monarchy’s survival is an especially curious socio-psychological phenomenon because the Crown is not in residence and is shared between 16 nation-states. Moreover, Australian national mythology is steeped in the promise of the ‘fair go’ for all in an egalitarian society (Moran 2011). Given this, Australia’s reluctance to dismiss the Queen from her constitutional duties seems more ‘bizarre’ than British persistence with this institutional arrangement (Billig 1998, 1). A society that avows egalitarianism but retains its inegalitarian symbolism is perplexing. But this is not unique to Australia: Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway also wed the monarchy to a polity with tendencies towards egalitarianism.

This chapter provides an explanation for the recovery in support for the monarchy. In particular, I find that the Baby Boomer generation’s experiences with the sacking of the Whitlam government have left an impression on that generation’s preferences. It turns out that Baby Boomers are not more progressive than other generations, but remain more republican than other generations.

Trends in Australian attitudes to the monarchy

Australian attitudes towards the monarchy have been far from stable for the last two decades (Mansillo 2016). Before the 1990s, there was considerable stability of the Australian public’s views on the question of abolition (Bean 1993; McAllister 2011). By abolition, I refer to the removal of the institution of the Crown in Australian law. This chapter focuses on the trend in Australian opinion from 1993 onwards and disaggregates movements in public attitudes by key socio-political characteristics. I look more closely at the role of cohort socialisation and value change in shaping the electorate’s attitudes over that period. The data analysed in this chapter is taken from the Australian Election Study (AES) (1993–2016).1

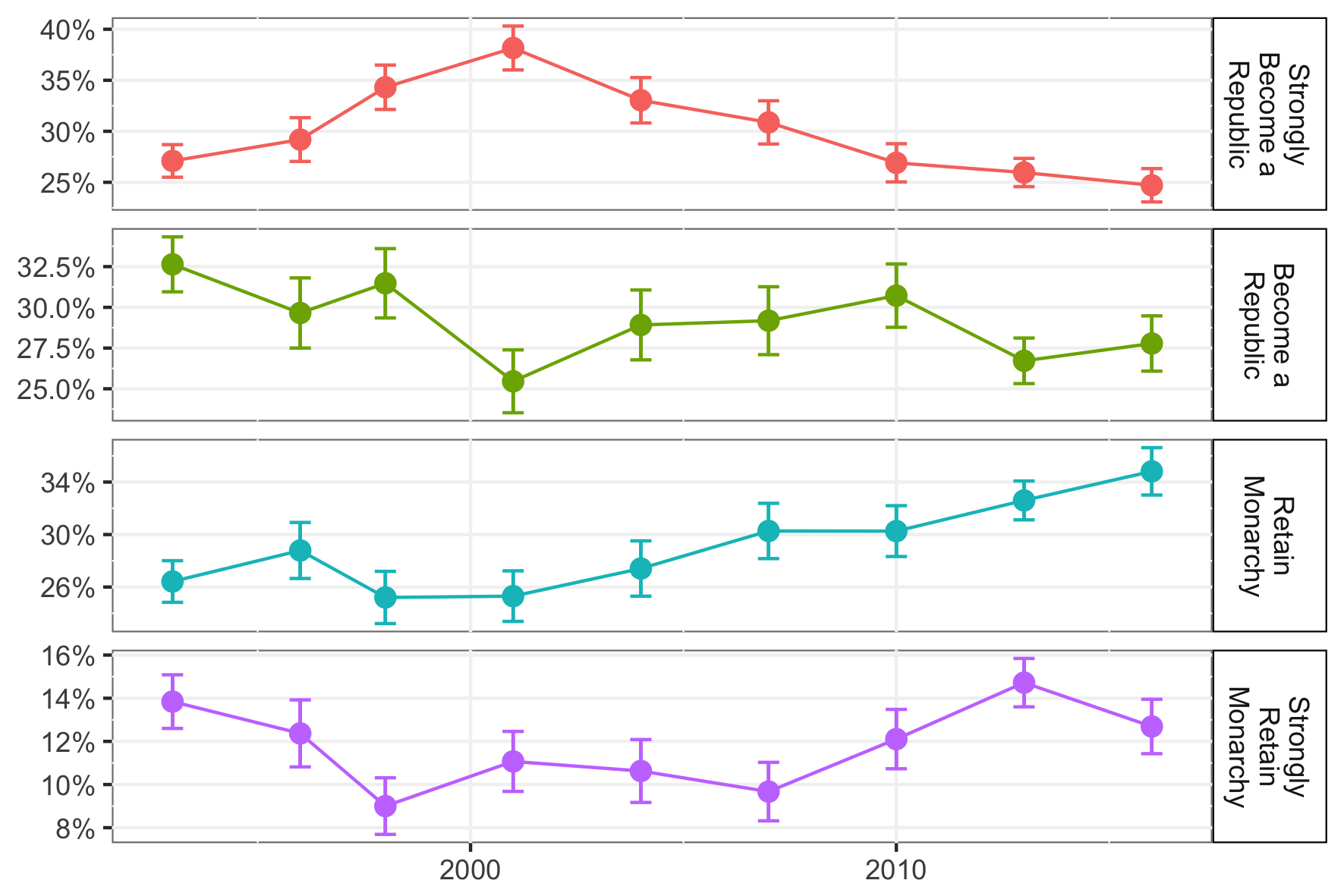

To begin, this chapter focuses on the abolition question. Respondents were asked: ‘Do you think that Australia should become a republic with an Australian head of state, or should the Queen be retained as head of state?’2 Figure 9.1 shows public opinion trends between 1993 and 2016. In 1993, 60 per cent of Australians preferred that Australia would become a republic. By 1998 this rose to 66 per cent – a year prior to the 1999 Referendum. Total support for the republic then withered over the next 15 years to 52 per cent in 2016. Not only has overall support for a republic fallen but its intensity has collapsed. In 2001, 38 per cent of Australians strongly preferred an Australian republic, and by 2016, this had fallen to 24 per cent.

Figure 9.1 Attitudes on retaining the monarchy, 1993-2016, %.

Source: Australian Election Study, 1993–2016.

Attitudes to the monarchy and age

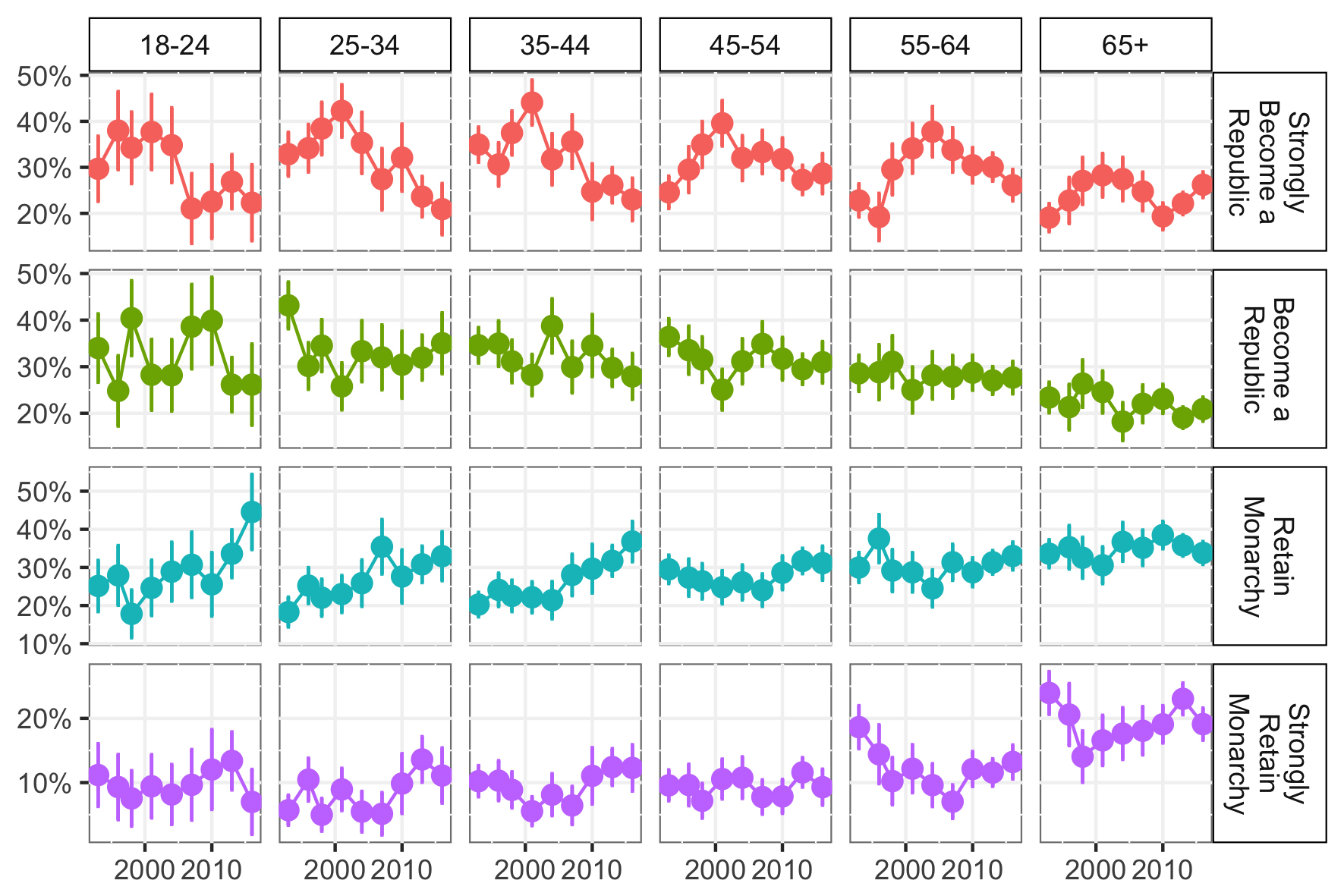

There is an interesting paradox between age and attitudes towards the monarchy. It is regularly assumed that young people in most advanced democracies hold generally progressive attitudes. This is thought to be a product of increasing physical and economic security and ‘generational replacement’ (Inglehart 1977; 1990). For example, young Australians typically hold more progressive views towards asylum seekers (Carson et al. 2016) and are more open to deeper links with Asia (McAllister and Ravenhill 1998). Young Australians also accept climate change science and support policy to curtail its effects at higher rates than older Australians (Tranter 2011; see also Chapter 4 in this volume). They position themselves to the left of centre and typically vote for progressive parties (McAllister 2011), and historically, they have been more supportive of the abolition of the Australian monarchy (Bean 1993). But, as Figure 9.2 shows, young Australians no longer prefer a republic in such large numbers (see also Mansillo 2016).

Figure 9.2 Attitudes about retaining the monarchy by age group, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

There are distinct age, cohort and period effects in the electorate’s attitudes. In 2016, young Australians aged between 18 and 24 years supported retaining the monarchy at higher rates compared to 1998. Due to data limitations these effects cannot be entirely separated through modelling. However, the attitudes of each cohort have an age profile which can be tracked over time. For instance, those aged between 18 and 24 years in 1993 had an approximate age range of 25 and 34 years old in 2001, and 35 and 44 years old in 2010 and 2013. This cohort’s overall support for a republic increased from 64 per cent in 1993 to 68 per cent in 2001. Over this period support intensified, with a 10 per cent increase in those who strongly favoured a republic. But by 2016, overall support had decreased to 51 per cent favouring a republic, with 12 per cent fewer who strongly held this preference. The observed changes over the period for this cohort’s attitudes demonstrate some flexibility in attitudes.

By 2013, there is clearly a nonlinear relationship with age: more of those aged between 18 and 24 years old (48 per cent) wished to retain the monarchy than those aged between 55 and 64 years old (43 per cent). However, more Australians aged 65 years or older (59 per cent) preferred to retain the monarchy than those aged between 55 and 64 years. Baby Boomers express the most pro-republican views overall. Baby Boomers’ views have not been adopted by their children. This is against expectations that ‘generational replacement’ would produce higher levels of republicanism (Bean 1993, 202–3).

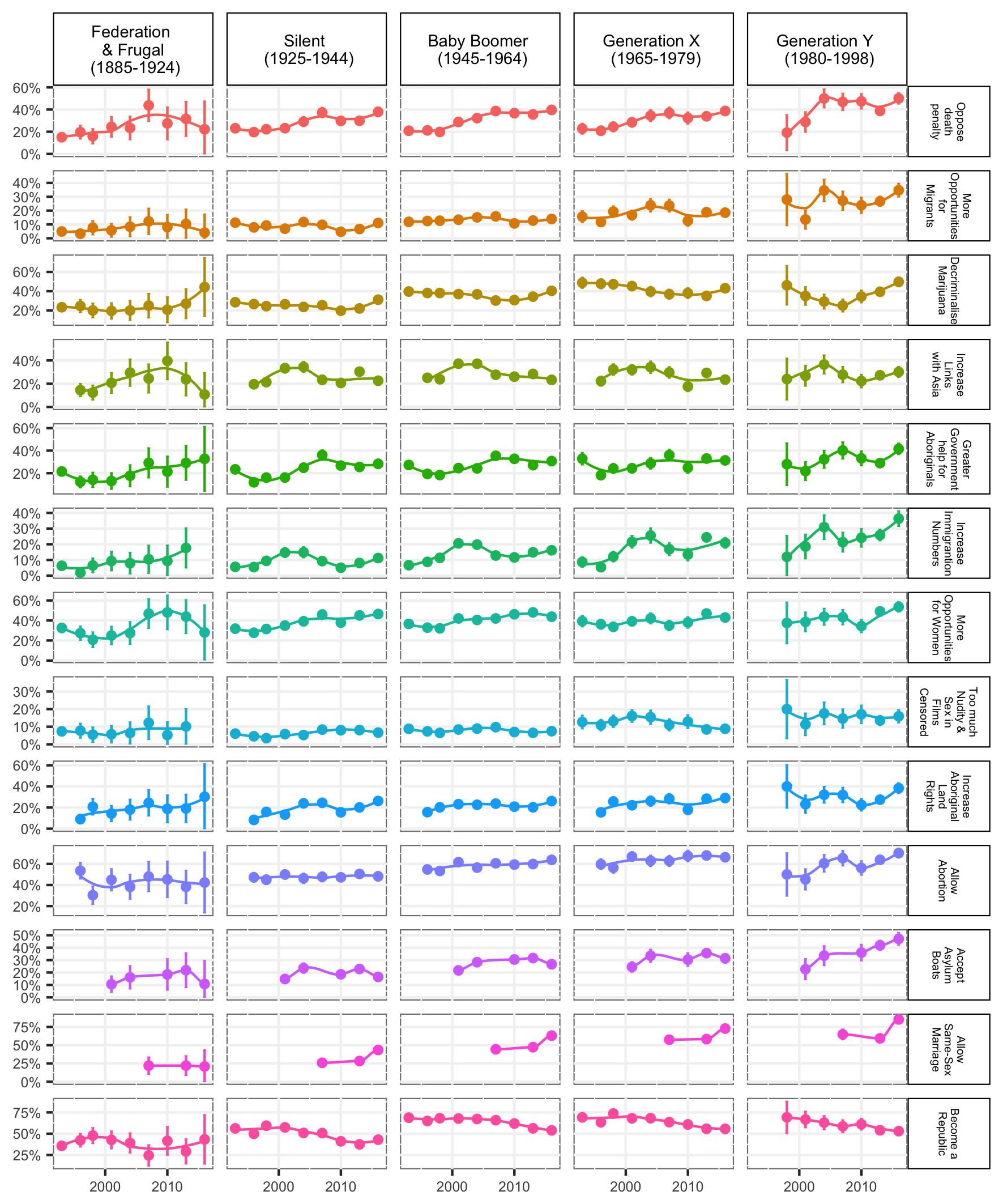

Baby Boomers have higher levels of support for an Australian republic, but why? Is this generation generally more progressive than other generations or did the experience of the Whitlam government make Baby Boomers exceptional? To assess whether Baby Boomers are more progressive than other generations, a series of social attitudes are compared by generation (see Appendix 9.1, Fig. 9.1A). Baby Boomers maintain more progressive views towards abolishing the monarchy than other generations. However, Generation Y is more progressive in their attitudes to same-sex marriage, allowing asylum seeker boats, higher immigration, Aboriginal land rights, censorship of nudity and sex in films, decriminalisation of marijuana, and greater opportunities for migrants. Baby Boomers and Generation Y have similar levels of support for allowing a readily accessible abortion, greater opportunities for women, and greater links with Asia. Australian republicanism is exceptional to Baby Boomers, who demonstrate little evidence of being more progressive than other generations. Despite historiography that stresses Baby Boomer involvement in progressive politics and social movements during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the generation is not more progressive on many social attitude indicators than younger generations.3 The Baby Boomer generation is regularly characterised by the radical activists who broke away from Old Left activities to participate in more informal, participatory and expressive practices which formed the basis of activities ranging from the freedom rides campaign for Indigenous rights, women’s liberation, gay liberation, and similar groups (Macintyre 2004, 232–36). Many sections of the contemporary feminist movement mourn ‘the passing of feminism’ and its rejection by many young women (Adkins 2004, 429), a historiography that idealises the 1960s and 1970s feminist movement and the Baby Boomer generation. For Australian Baby Boomers, the republic is their issue.

A Whitlam generation?

Political socialisation has an invaluable role in explaining an otherwise perplexing fact: unlike most issues debated in Australian politics, young people have less progressive attitudes than their parents when it comes to the monarchy. No individual is born an adult. Socialisation is a process whereby attitudes and social norms are developed through social learning (Bourdieu 1990, 135). Research suggests that the prime age for political socialisation is between the ages of 12 and 18 years (Schuman and Rodgers 2004; Torney-Purta 2004) but socialisation continues throughout life and the ‘fresh encounters’ with politics between the ages of 17 and 25 years also play a crucial role in forming political predispositions (Erikson 1968; Mannheim 1952; Somit and Peterson 1987). Figure 9.2 suggests that those who entered the 65 years or older cohort in 2016 – those born between 1949 and 1951 – were first-time voters in 1972.4 The first government they could elect was dismissed three years later. It is unsurprising that, at a time these Australians were becoming politically aware, the dismissal led these first-time voters to reject retaining the monarchy. This shift is reflected in the small drop in support for the monarchy compared to 2013 for those aged 65 years and over.

Major political events socialise voters and crystallise attitudes that remain decades later. The 1975 dismissal of the Whitlam government uniquely focused the public’s attention on the role and powers that the Constitution affords the governor-general and provided the foundations for the later growth in public support for Australian republicanism. Many Baby Boomers were politically socialised during this crisis, which appears to have left a mark on the cohort’s view of the monarchy (Mansillo 2016). While Baby Boomers have never had a particularly favourable opinion of the monarchy, their children have only really been presented with a generally favourable media image, and were socialised during the Howard era which some characterise as a conservative period (Johnson 2007; Gulmanelli 2014). Despite royal scandals in the 1990s (Benoit and Brinson 1999; Black and Smith 1999), in the twenty-first century, Buckingham Palace has maintained a good public image (Balmer 2009; 2011; Bastin 2009; Greyser et al. 2006; Wardle and West 2004). Billig (1998, 215) holds that both young and new royals provide ‘a breath of fresh air’ that can be seen to be ‘moving with the times’ as ‘[e]ach generation becom[es] less formal, less remote; the deferential society [becomes] more egalitarian’. In other words, younger members of the royal family appear more human and tolerable than older members. This change also goes some way to explain the age profile of support and opposition to the monarchy.

Australian republicanism is dear and salient to those who were adolescents or young adults when Whitlam was dismissed, but the issue does not interest many beyond this narrow cohort. Still, contemporary political elites in Australia are drawn overwhelmingly from cohorts who were politically socialised when the role of the monarchy was problematic. The Australian political class and media elites may be attracted to the issue with their pronounced opinions, explaining the many calls to restart the republican movement in recent years. Difficulty in a relaunched republican campaign gaining traction may arise with the young’s lack of fervency on the issue. A successful campaign would craft a campaign strategy mindful that the political figures who run the campaign are generationally distinct from those whom they must persuade on the reform. It is quite likely that elite and mass opinions on the republic are dissimilar. Such situations have the potential to cause political acrimony and campaign stagnation, with elites unable to relate to, or strategise appropriately to, the mass public opinion they seek to influence and convert into votes (Dalton 1987).

The republican movement has further demographic and political challenges. The median voter has become more supportive of retaining the monarchy and this has become increasingly diffuse across constituencies of interest. The median voter theorem would imply that parties would be motivated to reduce risks of dealignment, especially from new competitors (Downs 1957). Those most keen for a republic became eligible to vote in 1981. This cohort became the median-aged voter 18 years later when the 1999 referendum was held. Since then, policy demand for a republic from the public has declined, unlike demand from political elites. At the 2016 election this cohort was aged between 53 and 59 years while the median voter was aged 47 years. This constituency is relatively stable in their voting behaviour, with little risk of defecting from their partisan voting behaviour. Those whom political elites are most interested in competing for are increasingly less likely to be republicans. Recent canvassing for a new republican campaign has come from those politically socialised when Whitlam was dismissed. Political elites who currently have power will find appeals to young people that do not have cause to problematise the monarchy frustrating. Vexation may be amplified by a link between monarchism with ethnocentric and civic nationalisms (Mansillo 2016, 224). There would be difficulty employing republican appeals to national identity if nationalists associate the nation with monarchy. Disassociation of nationalism and monarchy requires stimuli. Perhaps the 1990s royal scandals produced a unique opportunity structure that facilitated the republican campaign’s inroads into public opinion. Political elites keen on abolition face a difficult strategic question: when to push for another referendum, given the risks. For any political elite who can foresee possible failure in abolishing the monarchy at a second referendum, the greatest unease would be the wait until a third referendum. Success has become less certain in recent years.

Attitudes to the monarchy divided by gender

There are reasonably large attitudinal differences between men and women, with about 15 per cent more women tending to support retaining the monarchy than men (see Figure 9.3). These differences were particularly pronounced in 1993 and from 2010 onwards in the AES data. For half a century, there have been persistent differences by gender on the question of abolition (Mansillo 2016, 218–20). Gender differences in attitudes have converged on many social issues (McAllister 2011, 112–20). However, attitudes towards retaining the monarchy are an exception.

The difference observed between the genders in Australia, however, does not appear in Britain (Billig 1998, 173). Billig (1998) found only differences in interest in royalty by gender in Britain but no difference on the question of abolition – something present in Australia. Billig describes a ‘household division of labour’ where royalty is a ‘female’ topic of conversation, and identified this ‘gendered territory’ in the interviews he conducted: ‘Royalty was being marked out as female business. Mothers, not fathers, would be interested in royal books; girls, not boys, would stand in the playground chatting about the Royal Family’ (Billig 1998, 179).

Figure 9.3 Attitudes about retaining the monarchy by gender group, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

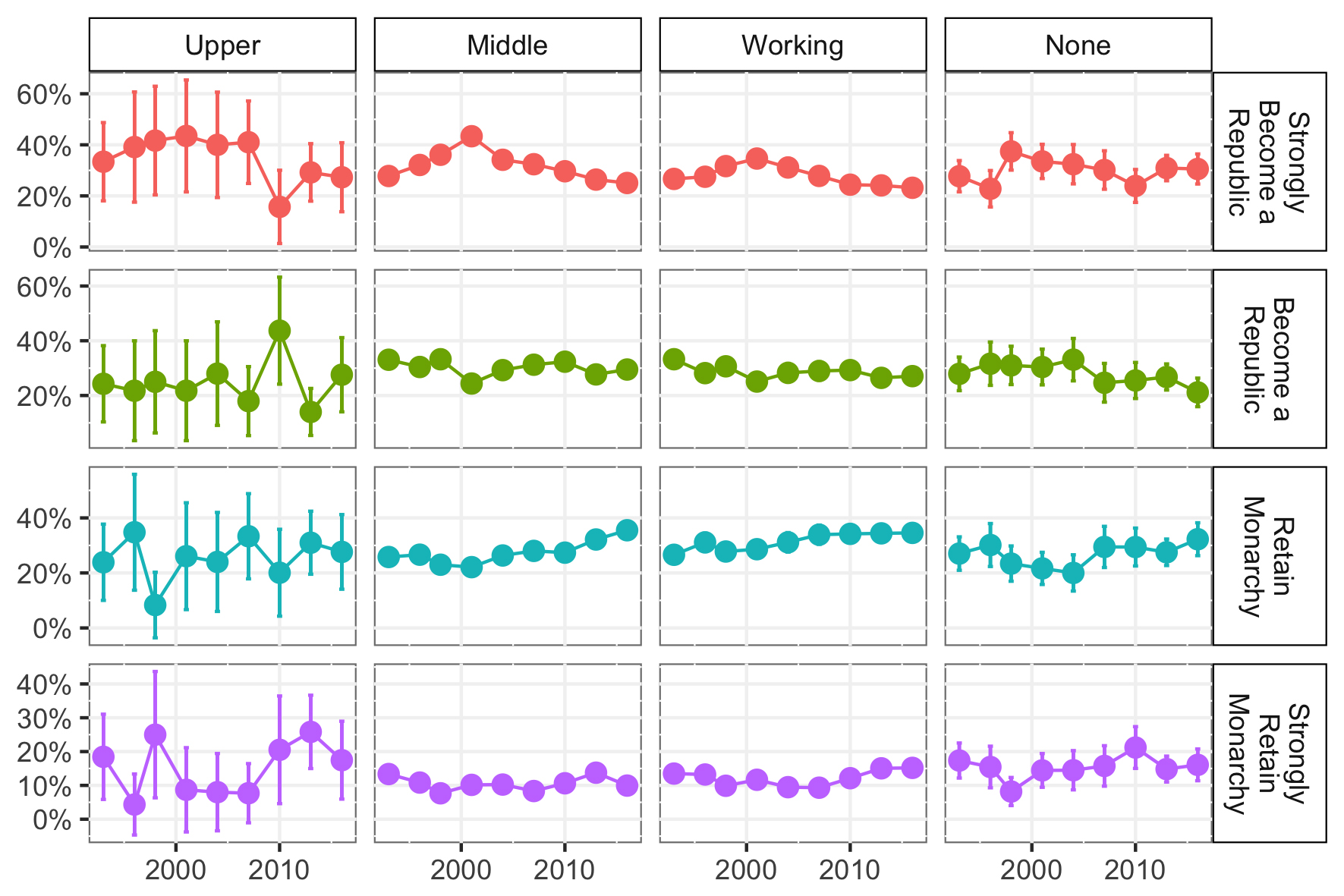

Socioeconomic status, education, and attitudes towards the monarchy

Socioeconomic status produces great differences in attitudes to retaining the monarchy. For simplicity, I use self-assessed class identification. There are stark differences in attitudes by class identities, as depicted in Figure 9.4. There is generally stronger support for a republic by those who identify with the upper and middle classes. Class social identities enable citizens to position themselves within a society’s intergroup social dynamics and such identification is a cognitive shortcut to understanding societal complexities (Hogg 2000).

Middle and upper class republicanism observed in Figure 9.4 fits well with assessments made by Stuart Macintyre (2004, 258–66) about the Keating government’s foray into the politics of a new national identity. He argues that Prime Minister Paul Keating – the chief advocate for a republic – had a ‘preoccupation’ with ‘big picture Australia’. This gave an impression of obsession with ‘noisy minority groups’ and their postmaterialist ‘pet’ issues such as the republic, reconciliation with Aboriginal Australians, and strengthening multicultural Australia, all as 1990s Australia languished through high unemployment. Those experiencing economic hardship and economic insecurity when confronted with insecurity of both culture and national identity cannot be expected to embrace republicanism with as much vigour as the well-to-do.

Figure 9.4 Attitudes towards retaining the monarchy by class identification, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

Despite enduring differences in attitudes between the upper/middle and working classes towards the monarchy, attitudes within classes have fluctuated. The AES data details more nuance than Macintyre (2004) suggests. In 1993, middle-class Australians were statistically indistinguishable from working-class Australians on whether Australia should retain the monarchy or become a republic. However, from then on, the middle class diverged from the working class, increasing their support for the republic. It should not be lost that when Keating was elected, middle- and working-class Australians had the same level of republicanism. By 1998 far more middle-class Australians were republican-leaning compared with working-class Australians. This difference persists but the degree has diminished over time. Since 1999 there has been convergence of views by class, as the referendum becomes a more distant memory. Overall, the middle and working classes have become less republican but small differences remain in their level of support for retaining the monarchy.

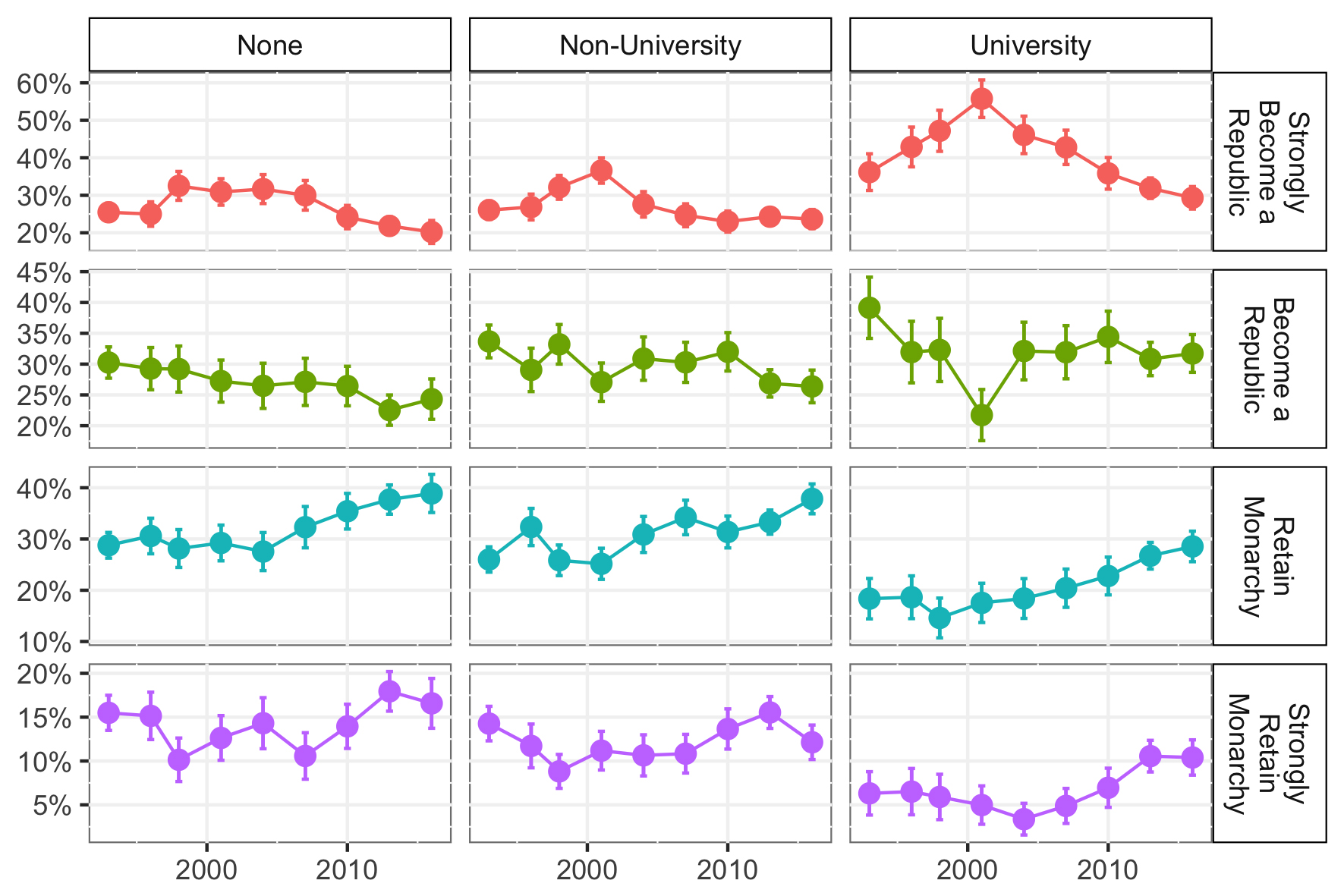

There is an expected similarity in the relationships of both class identification and education on attitudes towards retaining the monarchy (see Figure 9.5). This is unsurprising as a higher class position affords greater educational opportunities and greater education levels enable access to higher social class positions. The well-educated can improve their socioeconomic status through more lucrative jobs and those from high socioeconomic backgrounds have relative advantages through their greater capacity to afford their children educational opportunities not available to lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Figure 9.5 Attitudes towards retaining the monarchy by education levels, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

University-educated Australians have the lowest level of support for retaining the monarchy. However, more university-educated Australians supported retaining the Crown in 2016 than in 1993. In the 15 years from 2001 to 2016, university-educated Australians have also ‘weakened’ the strength of their republicanism, with half as many strongly preferring a republic. In 1993, Australians with a non-university post-school qualification were statistically indistinguishable from Australians without a post-school qualification. Both groups became more republican in the late 1990s, but both have since reduced that support. Those without a post-school qualification have a warmer opinion of the monarchy in 2016 than in 1993. Education is a good distinguishing feature of attitudes between Australians but over time there is little stability of attitudes produced by education. While the direction of support has remained relatively consistent in the period studied, the base level of each education level has fluctuated. Education as a proxy for political interest may have acted as an intermediary for media salience in the formation of attitudes.

Partisanship and attitudes towards retaining the monarchy

Political partisanship is the attachment to a political party that offers citizens a shortcut to navigate an otherwise complex political world and thereby reduces cognitive burden on citizens (Burden and Klofstad 2005). Moreover, political partisanship has long been known to be influential in determining social and political attitudes (McAllister 2011; McAllister and Kelley 1985) – including attitudes towards the monarchy (Bean 1993). Partisan identities condition voters’ attitudinal positions. Parties provide cues that activate latent predispositions or biases in citizens’ minds. These cues affect the degree to which individuals support attitudinal positions. Despite partisanship levels declining in post-industrialised countries, partisanship is comparatively stable in Australia and remains an essential conceptual tool to comprehend mass public opinion (Dalton and Wattenberg 2002).

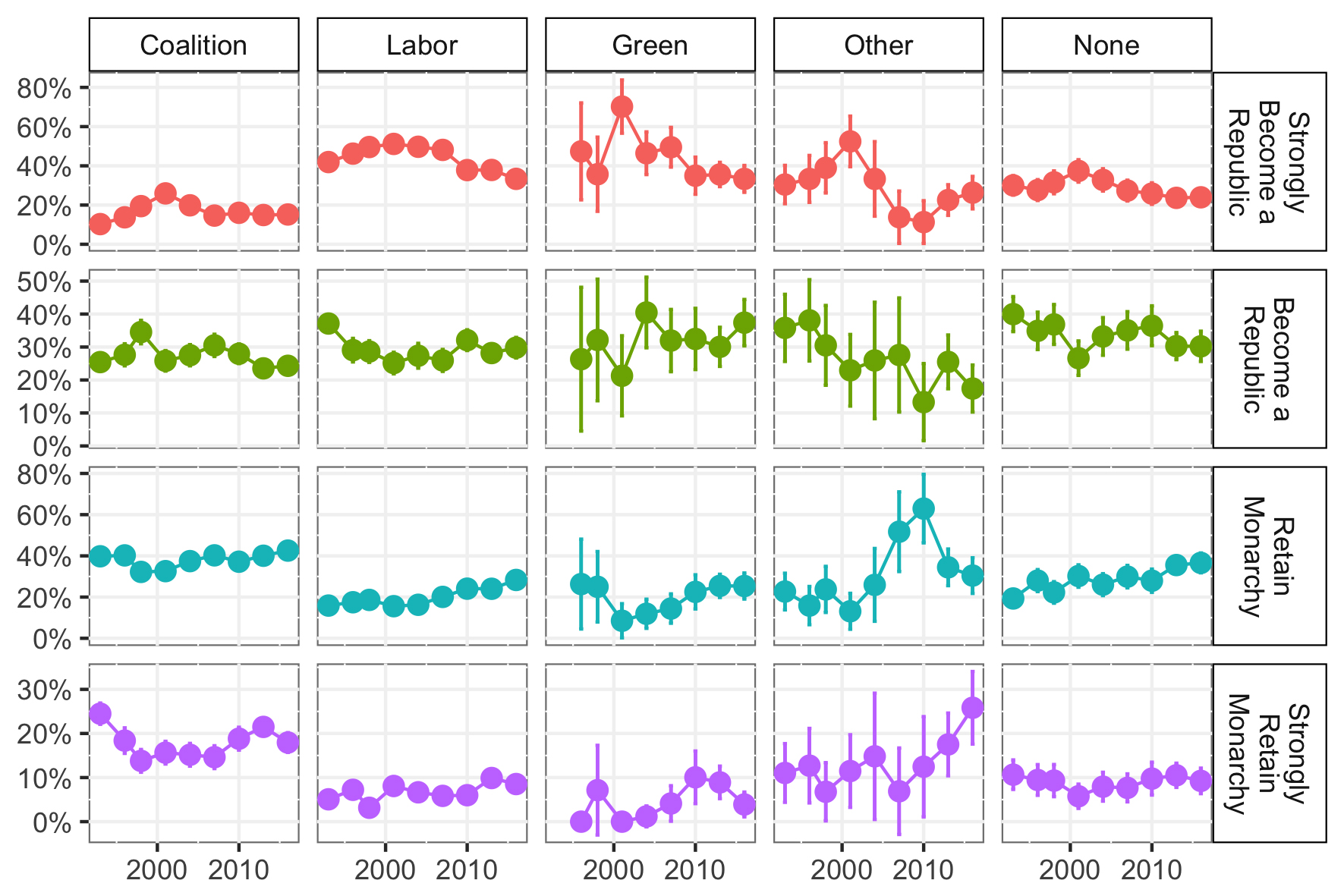

Figure 9.6 Attitudes towards retaining the monarchy by partisanship, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

Overall, Liberal–National Coalition partisans prefer to retain the monarchy (see Figure 9.6). In 1998, there was slim majority support for a republic (53 per cent) among this group, but this has since collapsed to a minority in 2013 (39 per cent). Labor partisans from 1993 to 1998 overwhelmingly supported a republic. In 1998, 21 per cent of Labor partisans preferred to retain the monarchy but this grew to 37 per cent in 2016. Attitudes were highly durable in the 1990s when issue salience made partisanship a relevant cue to inform attitudes. This effect may have weakened as the monarchy–republic issue featured less on the political agenda. Greens partisans are generally republicans: only 9 per cent in 2001 supported retaining the monarchy but this has since increased to 29 per cent by 2016. Those who identify with other minor parties since 2001 have increased in their support for retaining the monarchy.

In 2016, with 37 per cent of Labor partisans monarchists, Labor is more ‘cross-pressured’ on the issue than at any other time in the previous two decades. Of the 44 Australian referendums presented to the public since Federation, only eight have successfully passed and all have been with effective bipartisan support for the proposed reform. For republican campaigners to have a chance at success, support from both the Coalition and Labor would be required. Moreover, Labor partisans who are conflicted on the issue – or ‘cross-pressured’ in the language of Hillygus and Shields (2008) – could be persuaded at a general election to defect to another party if the Coalition tried to wedge Labor on this issue (see Carson et al. 2016; Wilson and Turnbull 2001). At the same time, the re-emergence of One Nation could pose the Coalition a potential threat to its electoral competitiveness. Monarchism taps into a strain of ethnic nationalism in the electorate which may be a source for One Nation or another far-right party to wedge the Coalition between inner-city ‘small-l liberal’ Liberal voters and culturally threatened (socially conservative) suburban Liberal and rural National voters. The issue may help facilitate One Nation’s appeal among ethno-nationalist Australians – the same people attracted to the party in 1998 when there was an active republic campaign.

Both Labor and Coalition party strategists have little interest in campaigning for a republic when they seek each other’s cross-pressured partisans to win office. In addition, partisans of other parties and the non-partisans are becoming an increasingly large component of the electorate. These crucial voters are evenly split on the issue. It remains to be seen how willing Labor and Coalition elites are to campaign on the issue given the risks of electorate realignment from the major parties.

Political interest and attitudes towards retaining the monarchy

An enduring debate in political science surrounds the public’s political sophistication and its implications for how citizens behave politically in a democracy. The level of public knowledge of and general interest in politics has long been thought to be essential for any democracy. For citizens to make meaningful decisions they must understand their options when political questions are presented. Citizens must understand their political system if they intend to wield influence and control their representatives. Core to a well-functioning democracy is that voters maintain an interest in political affairs (Almond and Verba 2015). The political knowledge and interest in politics of Australians are both quite low, similar to the situation in other post-industrialised countries (McAllister 1998).

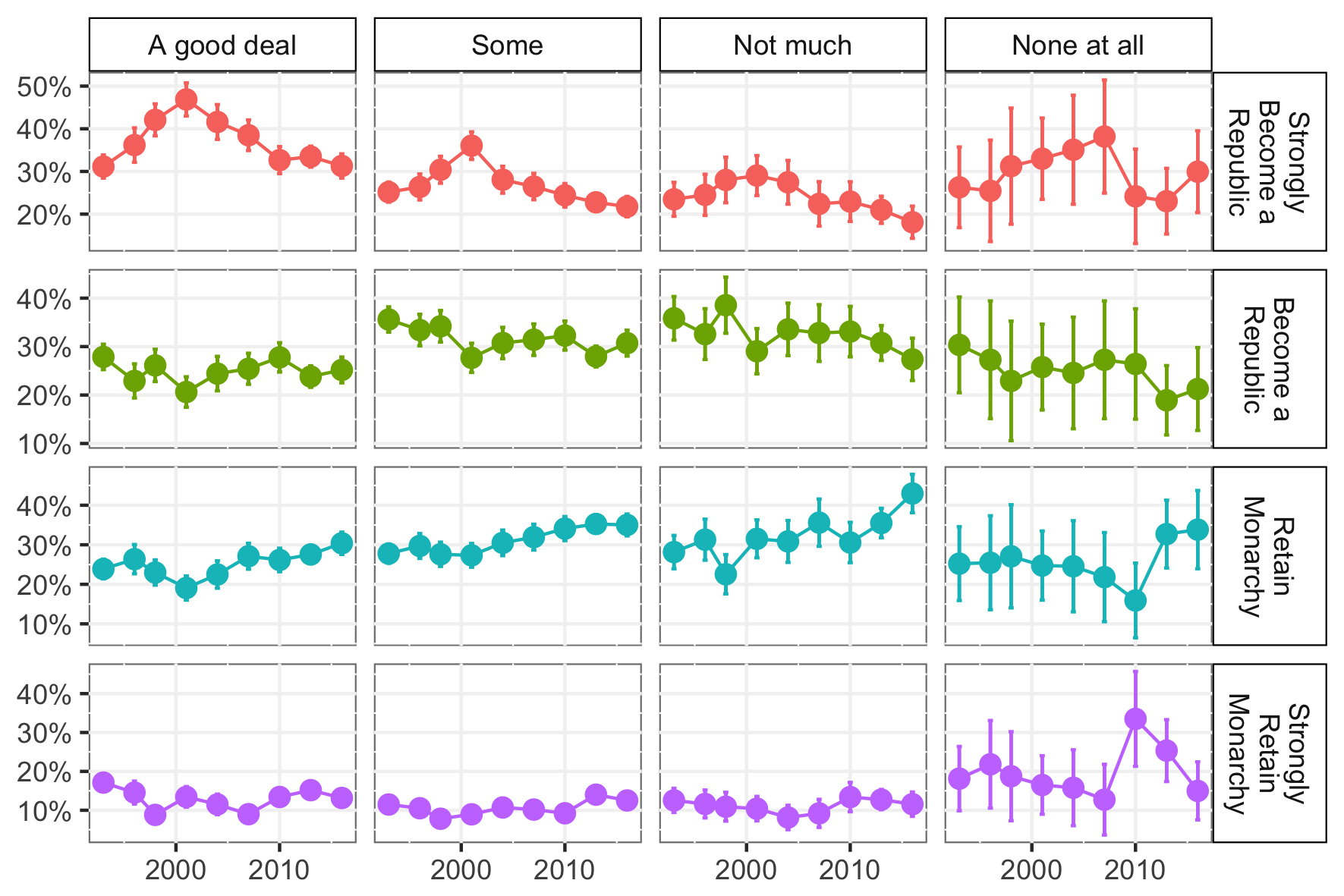

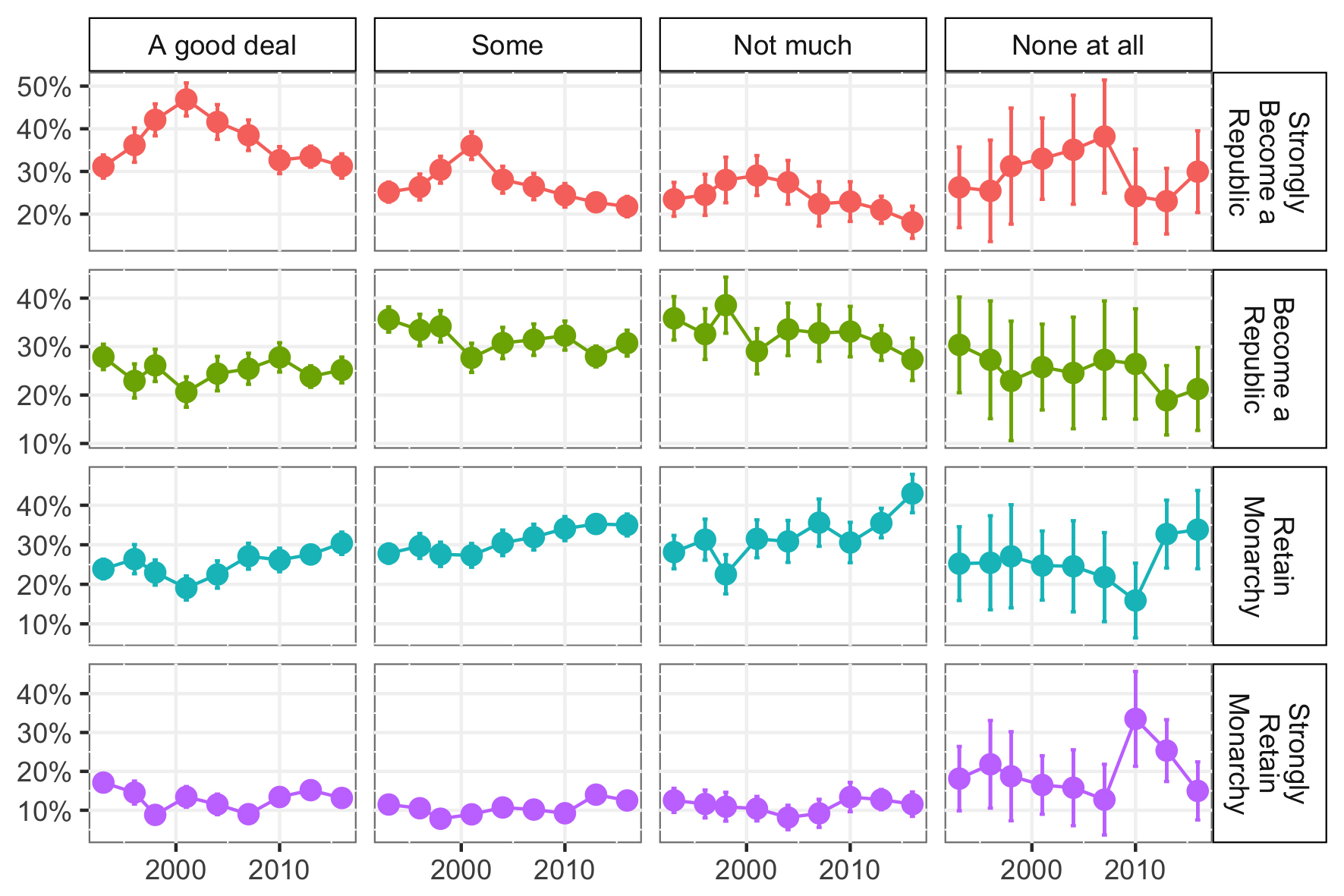

Attitudes toward retaining the monarchy should be affected by levels of political interest. People who are interested in politics tend to consider political questions and have firmer and more consistent views. People who are not interested in politics are not likely to frequently encounter political information but, when they are exposed, they are potentially easily swayed. Unlike most advanced democracies, Australia compels the least sophisticated voters to the polls. These voters do not typically turn out to vote in comparable democracies where voting is not compulsory. This makes the views of those with less political interest and little political sophistication more crucial to political outcomes for Australian democracy. Figure 9.7 disaggregates attitudes to retaining the monarchy by level of political interest. In 1993, attitudes were statistically indistinguishable between those with high and low levels of interest in politics. The monarchy became increasingly contested during the 1990s and therefore politically salient in the lead-up to the 1999 referendum. Those with the greatest levels of political interest became increasingly more republican. Those with ‘some’ interest in politics from 1993 to 2016 have become marginally more inclined to prefer retaining the Queen. Those uninterested in politics were far less republican. Those completely uninterested or with ‘not much’ interest in politics were statistically indistinguishable in 2001 from their 1993 views. As expected, even after enduring the most intense republic campaigning, these citizens’ attitudes did not shift.

All in all, those interested in politics are less likely to support a republic in 2016 compared to 2001. A marked shift in support for retaining the monarchy by those with ‘some’ or ‘not much’ interest in politics occurred between 2010 and 2013 (again, see Figure 9.7). This increase corresponded to a period that captures the marriage between Prince William and Catherine Middleton, lending weight to the argument that public spectacles like royal weddings legitimise royalty and improve attitudes towards the monarchy (Mansillo 2016, 230). Those citizens who are ambivalent on the issue appear to have greatly shifted their views in that period. Perhaps the period effect of royal scandal and the referendum in the 1990s (which enabled the sudden collapse in support) has ceased to be influential.

Figure 9.7 Attitudes towards retaining the monarchy by political interest, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

Monarchy yields to postmaterialism?

Advanced industrial societies following the Second World War experienced unprecedented levels of security through economic growth and stable international politics (Kremer 1993; Mearsheimer 1993). After the Great Depression and world wars, social-democratic parties in advanced industrialised democracies developed welfare states to reinforce the security offered by unprecedented prosperity. Postwar birth cohorts whose survival was secure developed more ‘postmaterialist’ values, i.e. prioritising self-expression, autonomy and quality of life (Inglehart 1977; 1990). After the Second World War, values and cultural norms have shifted through generational replacement, advanced by new social movements (Inglehart 1990, 314). Accordingly, these values should be important in determining attitudes towards the monarchy.

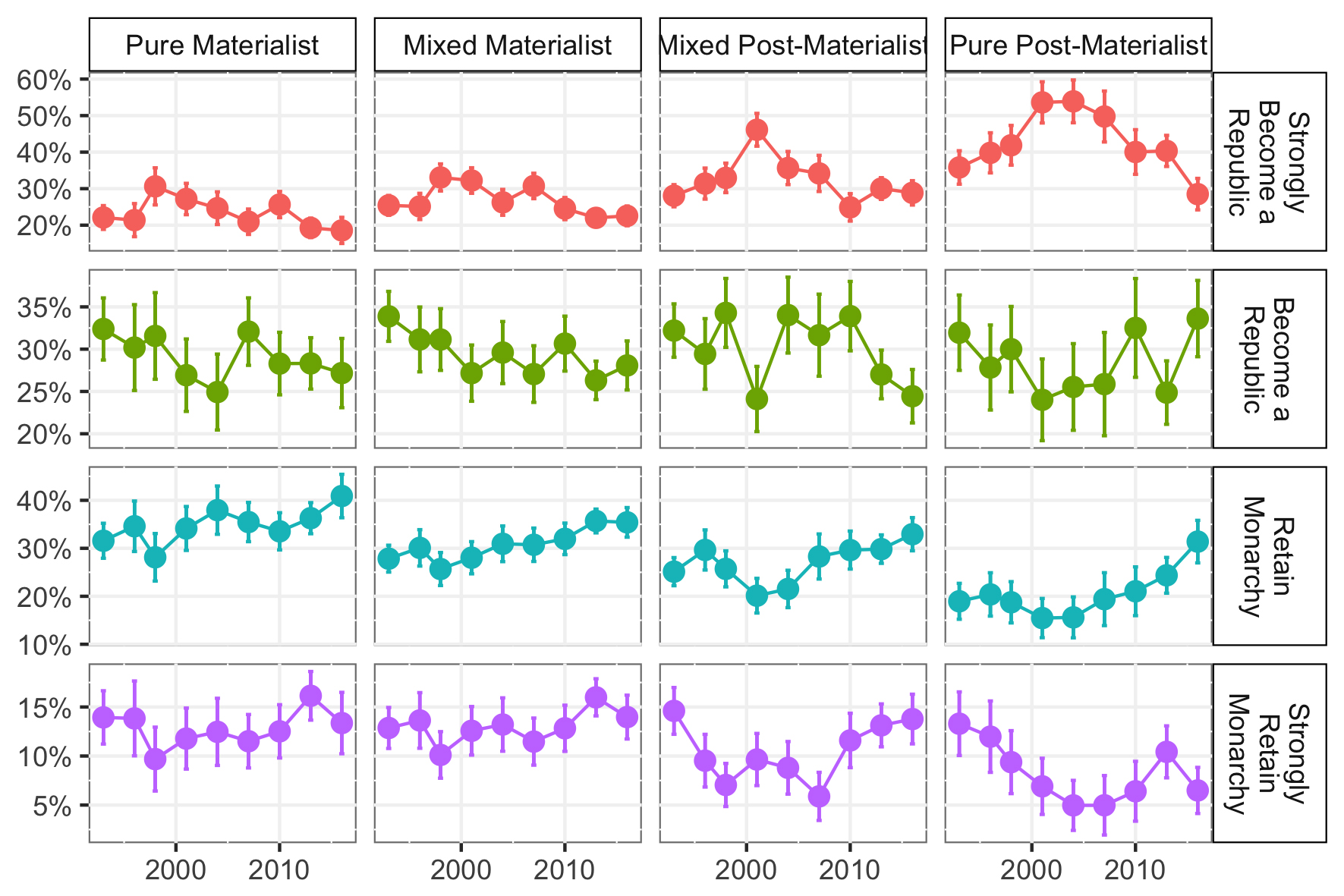

Figure 9.8 Attitudes towards retaining the monarchy grouped by the Postmaterialism Index, %.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

A postmaterialism index is constructed from responses to a set of two questions on important goals for a nation. They include two materialist options: ‘maintain order in the nation’ and ‘fight rising prices’; and two postmaterialist options: ‘give people more say in the decisions of the government’ and ‘protect freedom of speech’.5 Respondents who select only materialist or postmaterialist categories are classified as such. Those who select a postmaterialist option then a materialist option are mixed postmaterialists and conversely those who select a materialist option before a postmaterialist option are classified as mixed materialists.

Unsurprisingly, postmaterialists favour the replacement of the monarchy more than materialists (see Figure 9.8). There is relative stability in the levels of republicanism for materialists. Postmaterialists have had more fluctuation in their attitudes with support for retaining the monarchy increasing in recent years. Pure postmaterialists and mixed postmaterialists declined markedly in their support in the 1990s. There was a small drop for mixed-materialists’ and pure-materialists’ support for the monarchy in 1998 before then returning to trend. Mixed-materialists and mixed postmaterialists began in 1993 at the same position. By 2016 mixed-materialists had increased their overall support for retaining the monarchy somewhat, but mixed postmaterialists remain at their 1993 levels.

What determines attitudes towards the monarchy in Australia?

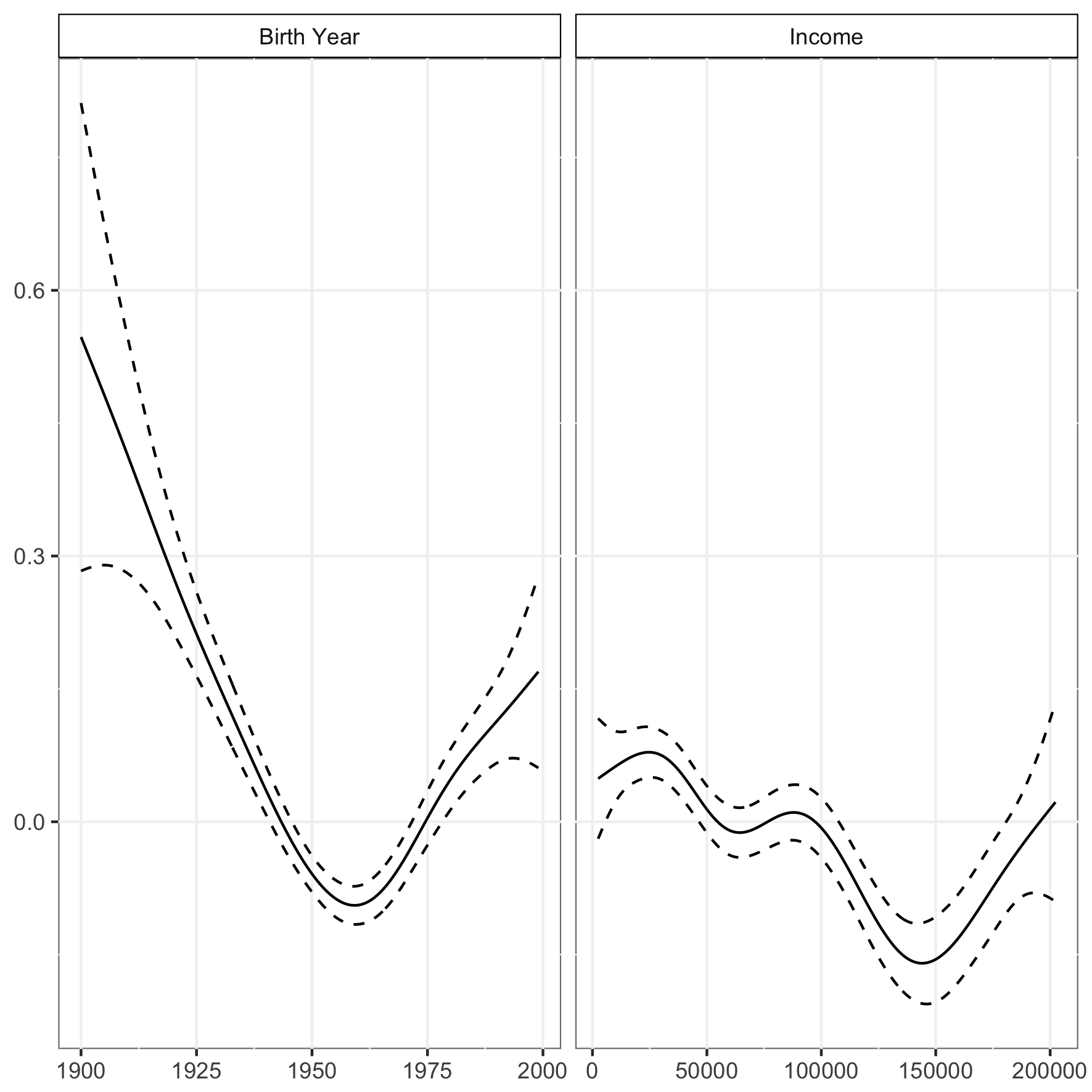

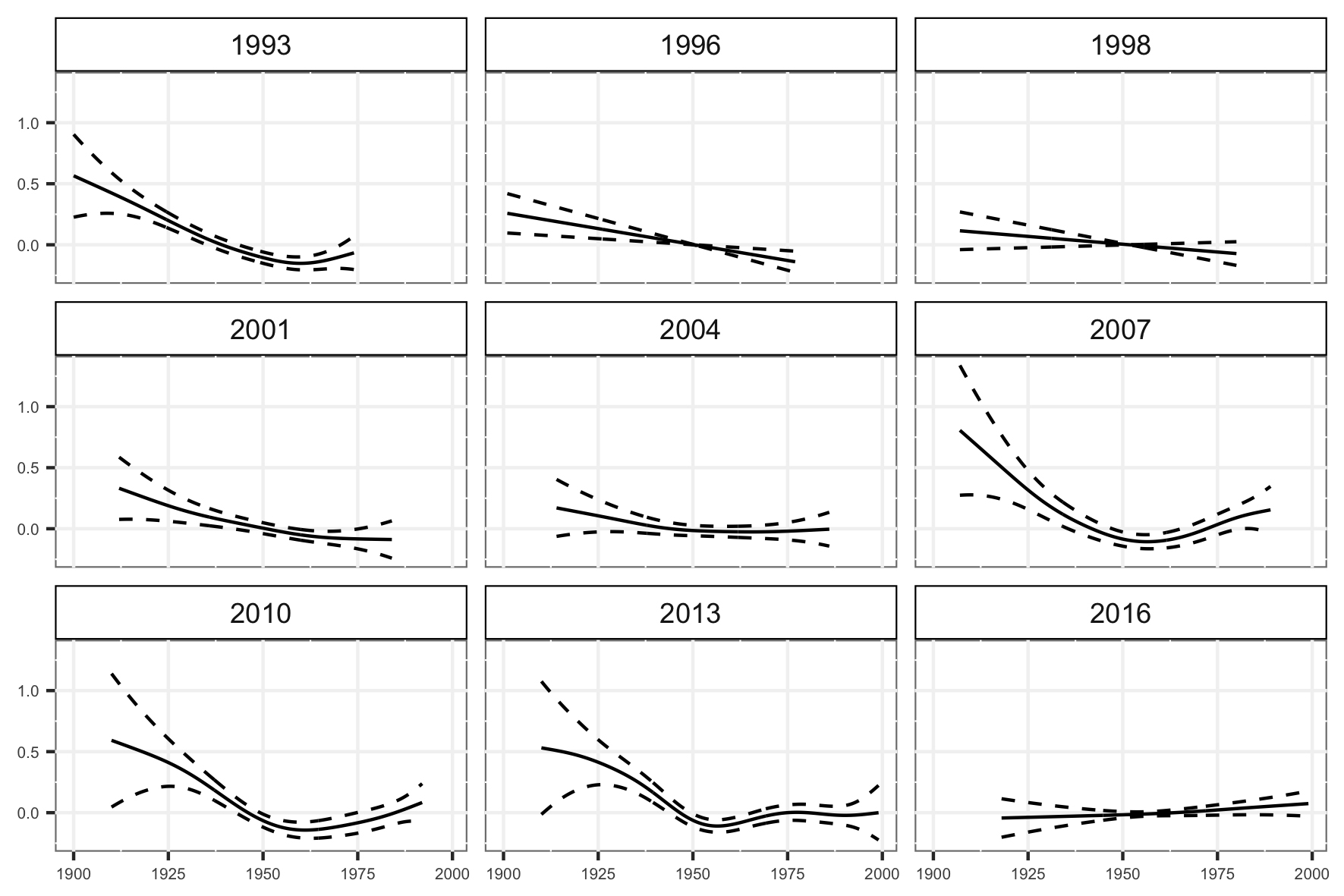

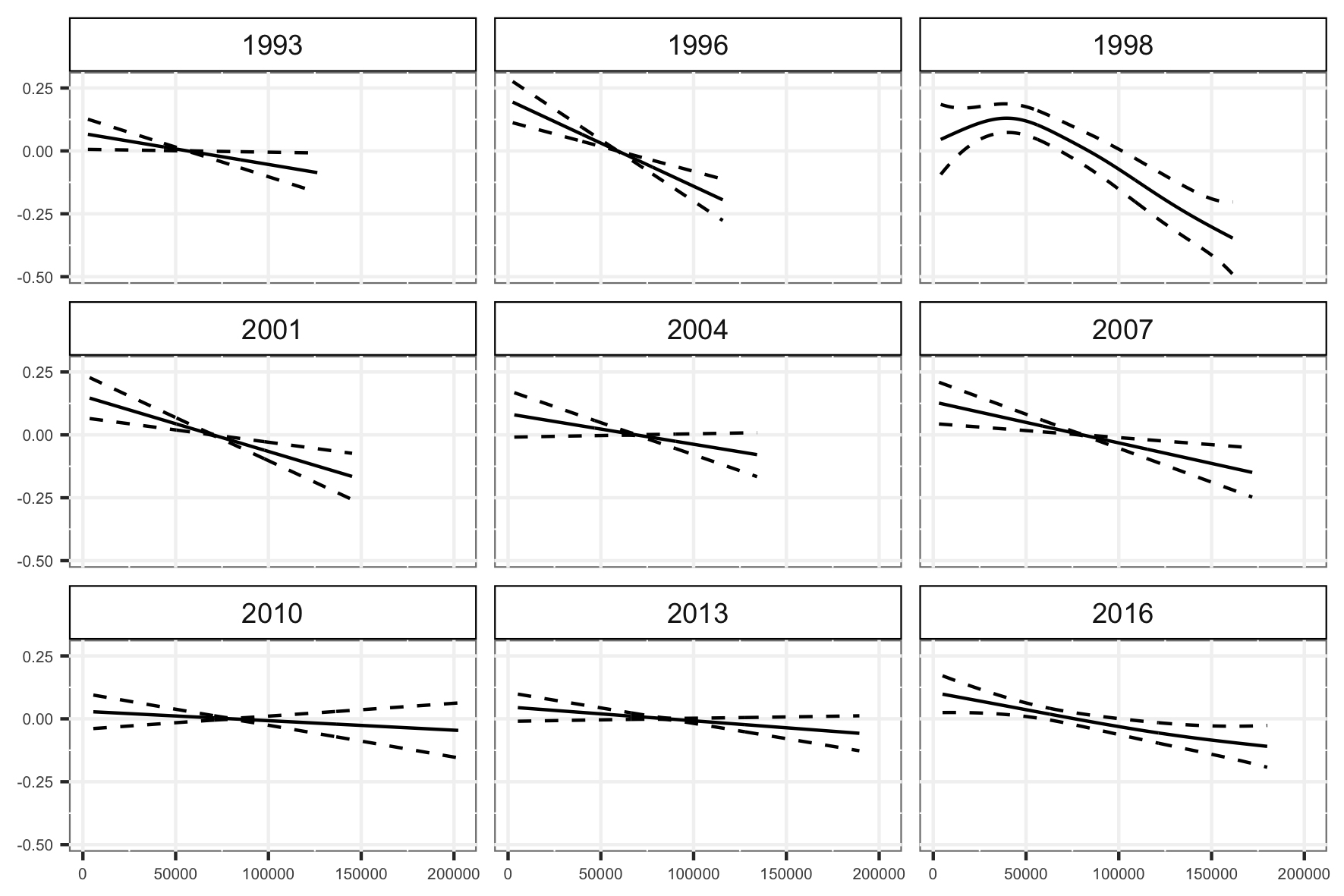

This chapter identifies several socio-political characteristics that structure opinion towards retaining the monarchy in Australia. To assess which factors are the most consequential and what durability they have in structuring attitudes, I employ a semiparametric generalised additive model (Wood 2011). Semiparametric regression was selected because age and income have nonlinear relationships with attitudes towards retaining the monarchy.6 For each of the nine studies attitudes towards replacement of the monarchy are regressed over birth year, family income, gender, university education, the postmaterialism index, Coalition partisanship, and level of political interest.7 The parameter and curve estimates are provided in Table 9.A2 and Figures 9.A2 and 9.A3.

The effects that birth year and income have on opinions move concurrently with each other. Years where birth year has a linear relationship, family income has a nonlinear relationship and vice versa. This fluctuation in effects between years could suggest a period effect or perhaps an over-identified model. In 1993, and 2007 through to 2013, birth year has a nonlinear relationship with support for retaining the monarchy greatest among older and younger birth cohorts. The lowest support is from those born during the late 1950s and 1960s who were socialised during the 1970s. These results confirm the cohort socialisation hypothesis that Mansillo (2016, 220–24) proposes. Consistently, those oldest birth cohorts record the highest level of support for the monarchy while those socialised at the time when the Whitlam government was dismissed maintain the lowest level of support.

However, the results show that, by 2016, young Australians were more supportive of retaining the monarchy than their seniors. When the issue held more salience amid royal scandals in the 1990s and politics surrounding the referendum, younger birth cohorts also had low levels of support. Salience of the issue conditions cohort opinion. Overall, moving from the highest support to lowest support there is 0.6 change in the dependent variable on the 1 to 4 scale.

Similarly, there are modest effects for family income in the survey years of 1993 and in surveys taken between 2007 and 2013, but there is far greater support for the monarchy in lower-income households than high-income households (with an income threshold effect that improves support for a republic around $60,000). When the issue salience was high, low-income households and those in the youngest birth cohorts shifted their support away from the monarchy. Support returned as the issue declined in salience.

How have the influences on attitudes to retaining the monarchy changed over time?

Education has an enduring effect on opposition to the monarchy. Overall, on the dependent variable’s 1 to 4 scale the effect of a university education produces on average a 0.2 change. The direction of the effect has been durable but its size has shifted. Education had a small effect in 2013 and when the issue was at its most salient in the late 1990s. Otherwise, when the issue has not been salient, education has had a larger effect on attitudes. Gender has typically had a significant effect, with women tending to support retaining the monarchy more than men. The effect was at its highest in 2016 at 0.3, which was twice the effect size of a university education for that year. Most years it has been lower. Mansillo (2016, 225) found during high and low issue salient periods, female British migrants and Australian-born women had identical attitudes on the issue; this was not the case for male British migrants, who exhibit more support for the institution than Australian-born men. Furthermore, the same study found a significant effect for education levels only for women in low salience periods; men and women in high salience periods did not demonstrate a significant effect for education levels, and age had a linear effect for men but no effect among women (Mansillo 2016, 226, 229). The finding that the effect for gender has strengthened in recent years and the evidence from Mansillo (2016) suggest there is significant scope for future research to unpack and explain these gendered differences in attitudes.

Over time, there has been a collapse in the effect size of Coalition partisanship on attitudes. Between 1993 and 2001, the effect size halved, indicating a realignment was underway that left an enduring structural weakness in support for the monarchy. Measured on the 1 to 4 scale of the dependent variable, Coalition partisanship had an effect of 0.84 in 1993 but has remained between 0.45 and 0.51 since the referendum in 1999. Postmaterialism has a small but enduring effect that produces opposition to the monarchy. The small effect sizes were counter to expectations that social values predominantly inform attitudes.8 Social values are typically thought to be central to attitude formation. Like the dependent variable, the index scaled from 1 to 4. The models find significant but ranging effect sizes. Moving from pure materialist to pure postmaterialist positions, the models find effects that range between 0.12 and 0.41 change in the dependent variable on its 1 to 4 scale.

The level of political interest has an overall stable effect in weakening support for the monarchy. The change in the dependent variable from the lowest to the highest level of political interest ranges from 0.13 to 0.46 over the period studied. The effect is about four times the size of gender for most years, or twice the effect size of a university education. This result suggests that the disengaged in politics prefer the status quo.

Overall, however, the largest effect identified is produced by birth cohorts. This is followed by large effects for political partisanship, political disinterest and postmaterialism while controls for gender, family income, and education have relatively small effects on attitudes.

Cohorts and media attention in shaping support for the Australian republican cause

These findings raise a follow-up question. If much of the variance can be explained by generational socialisation, what could explain the improvement across most generations long after their formative years? There is substantial attitudinal variance by political interest levels despite attitudes being structured around birth year cohorts. Scholars such as Kullmann (2008) argue that Australia’s republican ‘penchant’ exists, unlike in New Zealand, because the issue has received long-term media attention. Media increases the exposure of citizens to various issues, which increases the issue’s perceived importance and attitudes are considered with reference to media frames, partisanship or ideological predispositions. Media activity has the potential to prime public opinion. Media salience – the prominence given to a topic in media content – of the Australian republic issue provides stimuli that could influence the public’s attitudes. I now turn to test the hypothesis that the topic’s high media salience provides a stimulus that reduces support for the monarchy. This also provides an opportunity to more confidently identify the non-monotonous birth year effect curve shape.

Agenda-setting theory holds that media organisations have an ability to influence the salience of issues on the public agenda (McCombs 2005). Editors and producers use their editorial judgement to determine whether they will cover an issue and how much prominence they assign to it. Media consumers infer issue importance from its prominence within a news broadcast or page position and article length allocated in a newspaper. News media content is more likely to reach those who have reasonably firm opinions – people interested in politics seek out news and current affairs and those uninterested do not. News media salience may not directly prime attitudes of uninterested Australians who do not expose themselves to significant volumes of news and current affairs media. News media salience may indirectly prime attitudes of the politically uninterested by changing the topic’s salience in other media types such as comedy programs with a political flavour (Xenos and Becker 2009) or through introducing information through discussions with peers (Huckfeldt and Sprague 1995). Salience of a topic in news media content could directly or indirectly have implications for attitudes.

To test whether media salience has implications for attitudes towards retaining the monarchy, the previous regression model is repeated on the pooled AES data with a measure of media salience and an interaction with political interest. Media salience of the republic issue was created using a Factiva keywords search of print media mentions of an ‘Australian republic’ in major Australian newspapers over a year. Details of the scale are in Appendix 9.1. The results are reported in Appendix 9.2 and Figure 9.9.

Figure 9.9 Support for retaining the monarchy by birth year and family income (normalised to 2016 dollars).

Source: AES 1993–2016.

Note: Family income is mean-centred on the dependent variable, which is from 1 to 4.

The model indicates there is a significant negative interaction effect between low political interest and high media salience for the republic (as described in Appendix 9.1). This means that high media salience for the republican issue makes citizens who are politically uninterested less inclined to support retaining the monarchy. Gender, partisanship, education, and income have similar effects to the previous results for individual years.

By pooling the sample over the 23-year period, there is more data to better assess the cohort socialisation thesis discussed earlier. Figure 9.9 captures birth year’s nonlinear relationship with support for the monarchy. As described previously those who were politically socialised around the Whitlam government’s 1975 dismissal are the least supportive of the monarchy. Those who were socialised outside this period have less reason to oppose this institution. The other nonlinear relationship, the effect of family income, finds those with the most republican attitudes have equivalent 2016 inflation-normalised family incomes between $100,000 to $180,000. Family income has a considerably smaller effect on attitudes than birth year cohorts.

Conclusion

Australian attitudes towards the monarchy’s retention have changed over the past two decades. Advocates for another republic referendum face an uphill battle to convince Australians of their cause. This is especially the case because of the growing cohorts of voters with higher support for the monarchy than their parents. Social scientists writing about this subject two decades ago did not foresee a shift in public opinion contrary to expectations that ‘generational replacement’ would create a perpetual decline in support for the monarchy (see Bean 1993). These unexpected improvements in support for retaining the monarchy witnessed in recent years can be explained by existing social theory. Earlier assumptions that generational replacement would produce an ever-declining level of support for the monarchy is inconsistent with the observations made. These earlier thoughts on the topic can be built upon and nuanced. By acknowledging that different birth cohorts were politically socialised at different times with different experiences, changes in the electorate’s attitudes to the monarchy and the republican cause can be understood. On top of this, changes in media attention to the issue (that generate salience) provide a further temporal dimension to fluctuations in public opinion. Citizens that have little interest in politics are more prone to be swayed on the issue in high media salience periods. When media salience was last high, the media frame was typically negative and support for the monarchy was lower. It remains to be seen if media framing contributed to the formation of more negative public opinion towards the monarchy or if media salience itself changes public opinion, as the Kullmann (2008) comparison with New Zealand suggests.

Australian attitudes towards the monarchy have been remarkably stable but there has been a degree of malleability among Australians who are less politically interested. The structure of attitudes for socio-political characteristics such as gender, education, partisanship, and social values has remained relatively stable. There have been major movements in attitudes as a product of the interaction effect of media salience of the republic issue and low levels of political interest. Levels of political interest has remained relatively stable (McAllister 2011, 63).9 The evidence presented here suggests media salience has been crucial to the fluctuation in attitudes observed.

There is a distinct birth cohort who are keenest on Australia becoming a republic. This has implications for the potential for another republic campaign. Those keenest are increasingly distant from the median voter and their political demands are more likely to fall on deaf ears among political party elites who compete for votes. Despite some attitudinal rigidity from Baby Boomers, there has been some warming to the monarchy over time by cohorts who have little reason to problematise this institution (Mansillo 2016). The role that improved public relations and media image (Benoit and Brinson 1999) as well as ‘banal nationalism’ has had in self-legitimising the institution should not be neglected (Billig 1998).

Australian Baby Boomers, despite being keener on an Australian republic, are on most issues less progressive compared to Australians from Generation Y. The republic is a Baby Boomer preoccupation and a product of their unique political socialisation. A successful coalition for change would require more than Baby Boomers. Presently there is not enough support for another referendum to be successful. Any campaign would need to convince a significant proportion of the electorate to change the Constitution. The 1999 referendum failed as those who supported a republic could not agree on the form that an Australian republic should take (McAllister 2001). The double majority requirement for a majority of voters and majority of voters within a majority of states is a very high barrier to a campaign’s success. Short of royal scandals similar to those of the 1990s that undermined the monarchy, there are few social forces that could stop the royals from holding on to their throne.

References

Adkins, Lisa (2004). Passing on feminism from consciousness to reflexivity? European Journal of Women’s Studies 11(4), 427–44.

Almond, Gabriel A. and Sidney Verba (2015). The civic culture: political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Australian Election Study (2016). The AES studies: 19932016. http://www.australianelectionstudy.org/voter_studies.html.

Balmer, John M. (2009). Scrutinising the British monarchy: the corporate brand that was shaken, stirred and survived. Management Decision 47(4), 639–75.

Balmer, John M. (2011). Corporate heritage brands and the precepts of corporate heritage brand management: insights from the British monarchy on the eve of the royal wedding of Prince William (April 2011) and Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee (1952–2012). Journal of Brand Management 18(8), 517–44.

Bastin, Giselle (2009). Filming the ineffable: biopics of the British royal family. Auto/Biography Studies 24(1), 34–52.

Bean, Clive (1993). Public attitudes on the monarchy–republic issue. Australian Journal of Political Science 28(4), 190–206.

Bean, Clive and Elim Papadakis (1994). Polarized priorities or flexible alternatives? Dimensionality in Inglehart’s materialism–postmaterialism scale. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 6(3), 264–88.

Benoit, William L. and Susan L. Brinson (1999). Queen Elizabeth’s image repair discourse: insensitive royal or compassionate queen? Public Relations Review 25(2), 145–56.

Billig, Michael G. (1998). Talking of the royal family. London: Routledge.

Black, Elisabeth and Philip Smith (1999). Princess Diana’s meanings for women: results of a focus group study. Journal of Sociology 35(3), 263–78.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1990). In other words: essays towards a reflexive sociology. Cambridge: Polity.

Burden, Barry C. and Casey A. Klofstad (2005). Affect and cognition in party identification. Political Psychology 26(6), 869–86.

Carson, Andrea, Yannick Dufresne and Aaron Martin (2016). Wedge politics: mapping voter attitudes to asylum seekers using large-scale data during the Australian 2013 federal election campaign. Policy and Internet 8(4), 478–98. doi: 10.1002/poi3.128.

Dalton, Russell J. (1987). Generational change in elite political beliefs: the growth of ideological polarization. The Journal of Politics 49(4), 976–97.

Dalton, Russell J. and Martin P. Wattenberg (2002). Parties without partisans: political change in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

Davis, Darren W. and Christian Davenport (1999). Assessing the validity of the postmaterialism index. American Political Science Review 93(3), 649–64.

Downs, Anthony (1957). An economic theory of voting. New York: Harper.

Erikson, Erik (1968). Youth, identity and crisis. New York: W.W. Norton.

Glass, Jennifer, Vern L. Bengtson and Charlotte C. Dunham (1986). Attitude similarity in three-generation families: socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal influence? American Sociological Review 51(5), 685–98.

Goot, Murray (2013). Studying the Australian voter: questions, methods, answers. Australian Journal of Political Science 48(3), 366–78.

Greyser, Stephen A., John M. Balmer and Mats Urde (2006). The monarchy as a corporate brand: some corporate communications dimensions. European Journal of Marketing 40(7–8), 902–8.

Gulmanelli, Stefano (2014). John Howard and the ‘Anglospherist’ reshaping of Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science 49(4), 581–95.

Hillygus, D. Sunshine and Todd G. Shields (2008). The persuadable voter: wedge issues in presidential campaigns. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hogg, Michael A. (2000). Subjective uncertainty reduction through self-categorization: a motivational theory of social identity processes. European Review of Social Psychology 11(1), 223–55.

Huckfeldt, Robert R. and John Sprague (1995). Citizens, politics and social communication: information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald (1977). The silent revolution: changing values and political styles among Western publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Johnson, Carol (2007). John Howard’s ‘values’ and Australian identity. Australian Journal of Political Science 42(2), 195–209.

Jones, Barry (2007). A thinking reed. London: Allen & Unwin.

Kremer, Michael (1993). Population growth and technological change: one million BC to 1990. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108(3), 681–716.

Kullmann, Claudio (2008). Attitudes towards the monarchy in Australia and New Zealand compared. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics 46(4), 442–63.

Macintyre, Stuart (2004). A concise history of Australia. Second edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mannheim, Karl (1952). The problem of generations. In Essays on the sociology of knowledge. Paul Kecskemeti, ed. 276–322. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Mansillo, Luke (2016). Loyal to the crown: shifting public opinion towards the monarchy in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science 51(2), 213–35.

McAllister, Ian (1992). Political behaviour: citizens, parties and elites in Australia. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

McAllister, Ian (1998). Civic education and political knowledge in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science 33(1), 7–23.

McAllister, Ian (2001). Elections without cues: the 1999 Australian republic referendum. Australian Journal of Political Science 36(2), 247–69.

McAllister, Ian (2011). The Australian voter. Sydney: UNSW Press.

McAllister, Ian and Jonathan Kelley (1985). Party identification and political socialization: a note on Australia and Britain. European Journal of Political Research 13(1), 111–18.

McAllister, Ian and John Ravenhill (1998). Australian attitudes towards closer engagement with Asia. The Pacific Review 11(1), 119–41.

McCombs, Maxwell (2005). A look at agenda-setting: past, present and future. Journalism Studies 6(4), 543–57.

Mearsheimer, John J. (1993). Why we will soon miss the cold war. Atlantic Monthly 266(2), 35–50.

Minkenberg, Michael and Ronald Inglehart (1989). Neoconservatism and value change in the USA: tendencies in the mass public of a postindustrial society. In Contemporary political culture: politics in a postmodern age. John Gibbons, ed. 81–109. London: Sage Publications.

Moran, Anthony (2011). Multiculturalism as nation-building in Australia: inclusive national identity and the embrace of diversity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 34(12), 2153–72.

Schuman, Howard and Willard Rodgers (2004). Cohorts, chronology, and collective memories. Public Opinion Quarterly 68(2), 217–54.

Somit, Albert and Stephen A. Peterson (1987). Political socialization’s primacy principle: a biosocial critique. International Political Science Review 8(3): 205–13.

Torney-Purta, Judith (2004). Adolescents’ political socialization in changing contexts: an international study in the spirit of Nevitt Sanford. Political Psychology 25(3), 465–78.

Tranter, Bruce (2011). Political divisions over climate change and environmental issues in Australia. Environmental Politics 20(1), 78–96.

Wardle, Claire and Emily West (2004). The press as agents of nationalism in the Queen’s golden jubilee: how British newspapers celebrated a media event. European Journal of Communication 19(2), 195–214.

Wilson, Shaun and Nick Turnbull (2001). Wedge politics and welfare reform in Australia. Australian Journal of Politics and History 47(3), 384–404.

Wood, Simon N. (2011). Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 73(1), 3–36.

Xenos, Michael A. and Amy Becker (2009). Moments of Zen: effects of The Daily Show on information seeking and political learning. Political Communication 26(3), 317–32.

Appendix 9.1

Table 9.A1: Survey item coding for regression models.

| Measure | Coding | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Response variable | 1 = Strongly favour Australia becoming a republic 2 = Favour Australia becoming a republic 3 = Favour Australia retaining the Queen 4 = Strongly favour Australia retaining the Queen |

|

| Gender | 0 = Male 1 = Female |

|

| Partisanship | 0 = Not a Coalition partisan 1 = Coalition partisan |

|

| University qualification | 0 = No university qualification 1 = University qualification |

|

| Postmaterialism | 1 = Pure materialist 2 = Mixed materialist 3 = Mixed postmaterialist 4 = Pure postmaterialist |

This is the coding scheme adapted in Minkenberg and Inglehart (1989). |

| Political disinterest | 1 = A good deal [of interest in politics] 2 = Some [interest in politics] 3 = Not much [interest in politics] 4 = None [No interest] at all [in politics] |

|

| Family income | Annual family incomes in dollars that have been standardised for inflation | Family income, specifically gross annual family income, is measured ordinally in the AES between various enumerated incomes points on a scale. This scale’s measures have changed over the period the AES has collected its data to reflect the changes in the Australian economy, especially inflation and the income distribution. To standardise these ordinal measures, a ratio scale is created by taking the median of the incomes range for a category. This is then multiplied by the total change in inflation between the quarter that the election took place in and the quarter of the 2016 election occurred to standardise these measures. Inflation data was sourced from the Reserve Bank of Australia. |

| Birth Year | Year | |

| Republic media salience | 0 = Least standardised media content on an Australian republic for a year 1 = Most standardised media content on an Australian republic for a year |

The number of mentions of ‘the republic’, ‘Australian republic’, ‘Australian president’, and ‘Australian Head of State’ – but excluding ‘the republic of’ to prevent foreign states such as the Republic of the Congo from being added to the tally – in the print editions of the Advertiser (Adelaide), the Age (Melbourne), the Australian, the Australian Financial Review, the Courier-Mail (Brisbane), Daily Telegraph (Sydney), Herald Sun (Melbourne), Hobart Mercury (Tasmania), Northern Territory News, Sun Herald (Sydney), Sunday Age (Melbourne), the Sydney Morning Herald, and the West Australian (Perth) in a year was divided by the number of articles published in the print editions of each year. This was confined to general news and excluded articles categorised as relating to business, sport or music. The use of proportions rather than mentions was to control for the changing volume of articles written year to year and missing publications for earlier years. This was divided by the number of articles in the sample for that year and standardised to a 0 to 1 scale. |

Table 9.A2: Regression coefficients (support for retaining the monarchy).

| 1993 | 1996 | 1998 | 2001 | 2004 | 2007 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 | Pooled | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.110*** | 0.056 | 0.089* | 0.009 | 0.180*** | 0.076 | 0.245*** | 0.129*** | 0.304*** | 0.143*** |

| (0.036) | (0.049) | (0.048) | (0.049) | (0.050) | (0.048) | (0.044) | (0.033) | (0.040) | (0.014) | |

| Coalition Partisanship | 0.840*** | 0.663*** | 0.549*** | 0.446*** | 0.511*** | 0.493*** | 0.453*** | 0.479*** | 0.504** | 0.542*** |

| (0.037) | (0.050) | (0.051) | (0.051) | (0.053) | (0.050) | (0.046) | (0.036) | (0.042) | (0.015) | |

| University Education | -0.197*** | -0.309*** | -0.184*** | -0.210*** | -0.352*** | -0.183*** | -0.263*** | -0161*** | -0.157*** | -0.195*** |

| (0.052) | (0.062) | (0.064) | (0.063) | (0.063) | (0.059) | (0.052) | (0.036) | (0.044) | (0.018) | |

| PostMaterialism | -0.024 | -0.063** | -0.071*** | -0.128*** | -0.137*** | -0.117*** | -0.038* | -0.085*** | -0.072*** | -0.078*** |

| (0.018) | (0.025) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.025) | (0.023) | (0.017) | (0.020) | (0.007) | |

| Political Disinterest | 0.041* | 0116*** | 0.081** | 0.154*** | 0.026 | 0.082** | 0.097*** | 0.102*** | 0.046* | 0.096*** |

| (0.024) | (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.032) | (0.034) | (0.032) | (0.029) | (0.022) | (0.025) | (0.012) | |

| Republic Media Salience | -0.055 | |||||||||

| (0.060) | ||||||||||

| Political Disinterest * Republic Media Salience | -.060** | |||||||||

| (0.029) | ||||||||||

| Constant | 1.86*** | 1.927*** | 1.876*** | 1.916*** | 2.177*** | 2.065*** | 1.959*** | 2.148*** | 2.126*** | 2.032*** |

| (0.070) | (0.104) | (0.097) | (0.102) | (0.109) | (0.093) | (0.088) | (0.070) | (0.083) | (0.033) | |

| N | 2,444 | 1,399 | 1,440 | 1,543 | 1,330 | 1,436 | 1,853 | 3,386 | 2,212 | 17,043 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.234 | 0.177 | 0.129 | 0.132 | 0.159 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.103 | 0.105 | 0.129 |

Figure 9.A1 Political attitudes by generation, %.

Figure 9.A2 Birth year mean-centred effects on attitudes towards retaining the monarchy grouped by each study.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

Source: AES 1993–2016.

Figure 9.A3 Family income mean-centred effects on attitudes towards retaining the monarchy grouped by each study.

1 The Australian Election Study is a mail-out cross-sectional survey with repeated measures conducted in the three months after each federal election since 1987.

2 The closed measures were: ‘Strongly favour [Australia] becoming a republic’; ‘Favour becoming a republic’; ‘Strongly favour retaining the Queen [as the head of state]’; and ‘Favour retaining the Queen’.

3 Namely, the emergence of feminist, gay liberation, anti-nuclear, anti-war, civil rights, freedom of speech, and environmentalist social movements

4 In 1972, the voting age was 21 years old; it was lowered to 18 years in 1973.

5 Postmaterialism is measured here by the Minkenberg and Inglehart (1989) operationalisation of the Inglehart (1977; 1990) index. Identifying and measuring postmaterialism in public opinion surveys is highly debated since there are major concerns about frequent measurement validity (Bean and Papadakis 1994; Davis and Davenport 1999). The index items have been repeated on surveys for decades to maintain consistency in surveys of record despite these measures being unable to capture the full complexity of value change that early scholars of value change theory could not have predicted. While the index has its limitations it still contains value for social researchers.

6 Additivity or linearity cannot be reasonably attributed to age or income on the dependent variable. For example, the effect of a change in family income by $10,000 from $20,000 to $30,000 for an individual would be more consequential than the same increase in family income from $100,000 to $110,000.

7 Family income has been inflation-normalised to 2016 dollars.

8 The finding of small effect size reinforces measurement concerns in the literature (Bean and Papadakis 1994; Davis and Davenport 1999).

9 There is a question to be raised over declining data quality as response rates to the AES has halved over the period (Goot 2013). Response to a survey on politics is predicated to some degree on interest in politics. Nonresponse bias causing missing data on the variable of interest is a potential issue for the validity of such findings. If people who are uninterested in politics systematically do not answer surveys, there is a nonresponse problem for the characteristic we are drawing inferences from.