10

Marriage and happiness: changing Australian attitudes to marriage

In this chapter, we begin by outlining some dramatic changes in relationship formation, and then ask whether there has been an accompanying shift in attitudes surrounding perceptions of marriage. We examine three key attitudes about marriage. First, we look at whether Australians believe that people in a marriage are happier than their unmarried peers. Second, we look at opinions about childbearing outside of marriage. Third, we investigate to what extent Australians consider marriage to be an outdated institution. We conclude with some observations about the future of marriage.

Recent changes in marriage behaviour

While marriage remains a central institution in Australian society, with most Australians still ‘tying the knot’, there have been many recent changes to how and when people marry. To set the scene, we start by outlining some of the major trends in marriage over the last 35 years (Table 10.1). Although the absolute number of people marrying every year has increased over time, so has the population of Australia. The crude marriage rate, which measures the number of marriages occurring in a given year per 1,000 people, has experienced a steady decline from 7.4 marriages per 1,000 people in 1980 to 4.8 marriages in 2015.

Not only have overall marriage rates fallen, but how and when people get married has also changed. Australians are increasingly marrying later and after first living together in a cohabiting relationship. In 1980, the average age for men marrying for the first time was 24 years, and the average first-time bride was 22 years of age. Of couples marrying in that year, about three out of ten lived together before tying the knot and the majority of marriages were performed by a minister of religion. Thirty-five years later, in 2015, the characteristics of couples marrying was very different. The average man marrying for the first time is 30 years old, and the average woman is 29. Living together before marriage is much more prevalent and now practised by eight out of ten couples. Most marriages are now performed by a civil celebrant rather than a minister of religion.

Table 10.1: Selected marriage statistics, 1980–2010, 2015.

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude marriage rate (marriages per 1,000 estimated resident population) | 7.4 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 4.8 |

| Median age at first marriage | |||||

| Men | 24 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 30 |

| Women | 22 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| % couples living together before marriage | 29 | 45 | 71 | 79 | 81 |

| % marriages performed by minister of religion (vs civil celebrant) | 64 | 60 | 47 | 31 | 25 |

| % of births born outside of marriage | 12 | 22 | 29 | 34 | 35 |

| Crude divorce rate (divorces per 1,000 estimated resident population) | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| Median interval between marriage and final separation | 7.5 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 8.5 |

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics (1994, 2000a, 2000b, 2010, 2016a, 2016b).

The declining rate of marriage has not occurred uniformly across sub-populations. There is evidence of growing socioeconomic differentials in the probability of marrying among young Australians (Heard 2011). For many young people, financial security and home ownership are still important preconditions for getting married, and as a result, marriage rates appear to be declining fastest among those with the lowest education and income (Heard 2011; Hewitt and Baxter 2012).

Alongside changes in entering into marriage, there has been dramatic change in the ending of marriages. The introduction of the ‘no fault divorce’ in the Family Law Act 1975 led to a sharp increase in divorces in the late 1970s. Since then, however, the divorce rate has stabilised somewhat and only fluctuated slightly. As a result of these changes, Australians are increasingly less likely to find themselves married at any point in time. According to the Census, in 1981 about 8 per cent of men and 4 per cent of women aged 40–44 had never been married. By 2011, the figure had increased to 25 per cent of men and 19 per cent of women. However, people who are not married may still be living with a long-term partner in a committed de facto1 relationship. De facto relationships are ones where the couple lives together but is not formally married, although the relationship may transition to a marriage at a later stage. In the early 1980s it was estimated that only around 5 per cent of couple relationships were de facto (ABS 1994). By 1992, this had increased to 8 per cent of all couples and by 2011 to 16 per cent (ABS 2012).

With cohabitation now a socially acceptable alternative to marriage (Evans 2015), many more children are also born out of wedlock, and the link between marriage and childbearing has weakened. The proportion of babies born outside registered marriage also rose from just over one in ten in 1980, to just over three out of ten births in 2015 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016a).

Changing attitudes to marriage

It is clear from the statistics presented above that it has become increasingly common for people to marry later (or not at all), and to have children outside of marriage. But how have people’s attitudes to marriage changed over time?

At both individual and societal levels, attitudes and behaviours about marriage can be expected to reinforce each other via various ‘feedback loops’ (Nazio and Blossfeld 2003; Emens, Mitchell and Axinn 2008). If we use cohabitation as an example, at the individual level a person who has more favourable attitudes towards cohabitation is more likely to cohabit themselves. Similarly, if at a societal level cohabitation becomes an increasingly accepted alternative to marriage, more people will engage in this behaviour as they will not have the fear of being stigmatised. But behaviour can in turn impact on attitudes. Someone who was previously opposed to divorce might find themselves more accepting of it once they experience it themselves. And, as the proportion of the population who have experienced divorce increases, so does the population who is exposed to this behaviour via their peers. This in turn can make divorce a more socially acceptable behaviour.

Drawing on data from the National Social Science Survey (NSSS), the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA), as well as the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, we examine how attitudes about marriage have changed from the late 1980s until 2012. We outline the overall change over time in attitudes but also specifically look for the influence of respondent gender, age, and relationship status on attitude change.

An influential idea in the world of family research is that there are ‘his’ and ‘her’ marriages, and that men and women receive different benefits from marriage. As Bernard (1972, 14) noted over four decades ago: ‘there are two marriages in every marital union, his and hers. And his . . . is better than hers’. Although this ‘differential benefits’ hypothesis has since been questioned (Williams 2003; Jackson et al 2014), we look at the gender differences in how questions were answered in order to take into account possible differences in how men and women perceive marriage. We also compare attitudes towards marriage by age of respondent as studies on a wide range of social issues find that older people tend to have more conservative views than younger people (Tilley and Evans 2014). Social attitudes towards marriage are also influenced by each individual’s own experience with marriage, so we therefore distinguish between respondents based on their current relationship status. Furthermore, as social attitudes commonly differ between urban and rural residents, we include an indicator of where respondents live. Finally, we also consider the impact of education on respondent attitudes to marriage – previous research suggests education levels matter to both attitudes and behaviour in this area (Treas et al. 2014; Hewitt and Baxter 2012).

Are married people seen as being happier than unmarried people?

Research conducted across time and in different countries generally finds that married people are happier than their unmarried peers (Easterlin 2003), although the exact relationship between marriage and happiness is complex (Stutzer and Frey 2006). In countries where cohabitation is more widespread there is little difference in the wellbeing of cohabiting versus married people (Vanassche, Swicegood and Matthijs 2013; Lee and Ono 2012). However, in Australia, some researchers still find evidence that married people have higher life satisfaction than their cohabiting peers (Evans and Kelley 2004). In this section we do not examine the effect of marriage on happiness per se, but rather what Australians think about marriage and happiness. If married people are generally seen as being happier than others, then this can be seen as a declaration of the superiority of marriage (Treas et al. 2014).

The following statement has been presented in surveys in 1988, 1994, 2003 and 2012 ‘Married people are generally happier than unmarried people’. Respondents were asked to consider this statement and could choose between the following response options: Strongly agree, Agree, Neither agree nor disagree, Disagree and Strongly disagree, or Can’t choose (in 1989 and 2012). The distribution of responses is shown in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2: Married people are generally happier than unmarried people, %.

| 1989 | 1994 | 2003 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 12 | 9 | 10 | 4 |

| Agree | 33 | 34 | 35 | 22 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 28 | 34 | 32 | 37 |

| Disagree | 20 | 17 | 17 | 25 |

| Strongly disagree | 5 | 6 | 6 | 9 |

| Can’t choose | 2 | n/a | n/a | 3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Sources: National Social Science Survey (NSSS) 1989 (N=4,060; Kelley et al. 1990), International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) 1994 (N=1,662; Kelley et al. 1994); Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA) 2003 (N=1,215; Gibson et al. 2004); Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA) 2012 (N=1,421; Blunsdon 2016).

Note: Sample sizes shown are for the final analytical sample after missing values were excluded.

Looking at the broad trends over time allows us to see whether there has been any change over the last few decades in how Australians view marriage and the extent to which it is seen as superior to being unmarried. A strong and consistent shift away from agreeing that married people are generally happier than unmarried people is evident. In 1989, 46 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. By 2012, this had fallen to just 26 per cent.

One important point to keep in mind is that, in responding to the question, it is unclear whether the implied comparison is between married people and single people or de facto couples – or both. Given the fact that the question is open to interpretation, different respondents may use different comparison groups. For example, someone who is currently cohabiting might compare married people to cohabiting people. In a general sense, in answering the question, respondents are likely to draw on their own experiences: someone who was unhappily married and is now divorced may not rate marriage as a source of happiness.

Table 10.3: Percentage agreeing that married people are generally happier than unmarried people, by selected characteristics for each year, %.

| 1989 | 1994 | 2003 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 51 | 50 | 52 | 35 |

| Female | 40 | 37 | 39 | 20 |

| Age | ||||

| <30 | 28 | 34 | 30 | 12 |

| 30–39 | 40 | 33 | 40 | 18 |

| 40–49 | 45 | 41 | 46 | 25 |

| 50–59 | 56 | 45 | 44 | 25 |

| 60–69 | 65 | 54 | 54 | 30 |

| 70+ | 75 | 68 | 60 | 42 |

| Relationship statusa | ||||

| Married | 52 | –– | 51 | 34 |

| Cohabiting | 18 | –– | 35 | 13 |

| Separated/divorced | 31 | –– | 37 | 17 |

| Widowed | 61 | –– | 45 | 16 |

| Single & never married | 28 | –– | 24 | 10 |

| Urban/rural | ||||

| Rural | 49 | 45 | 44 | 28 |

| Urban | 44 | 43 | 45 | 26 |

| Education level | ||||

| Incomplete secondary | 49 | 45 | 45 | 30 |

| Completed secondary | 39 | 41 | 42 | 22 |

| University | 42 | 45 | 47 | 26 |

| Total % | 46 | 44 | 45 | 26 |

| Total N | 3,988 | 1,662 | 1,215 | 1,421 |

Note: a 1994 cohabitation information was not available in this year. Sources: NSSS 1989; ISSP 1994; AuSSA 2003 & 2012.

To further examine this question, we grouped together everyone who said they agreed or strongly agreed that married people are generally happier and compared the percentage of respondents who agreed across different characteristics, such as gender, age, and relationship status. The results can be seen in Table 10.3. Starting with gender, it is clear that in every year men were more likely than women to agree with the statement that married people are generally happier. This sex difference has been observed in other studies that have examined this question (Parker and Vassalo 2009; Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001; Treas et al. 2014). This difference in how men and women responded to this statement could result from differences in how men and women view marriage and the benefits they believe marriage has. Previous research has shown that men may derive more benefits from marriage and that husbands report greater marital satisfaction than wives (Bernard 1972; Fowers 1991).

A very strong relationship was also evident between agreeing with this statement and a person’s age. Compared to younger people, older people were significantly more likely to feel married people were happier than unmarried people. This is consistent with what we expected: older people tend to have more traditional views about marriage and are therefore likely to believe being married is superior to not being married.

As suspected, current relationship status was an extremely important influence in responses to this statement. Married people, and widowed people, were the most likely to agree with the statement. Conversely, in every year those who were single and never married, or cohabiting, were the least likely to agree. For example, in 2002, just over half of married people agreed or strongly agreed that married people are happier than unmarried people, compared to a quarter of those who were single and never married and about a third of those who were cohabiting. Separated or divorced people also had low levels of agreement on the question, likely reflecting their own unhappy experiences. Contrary to what we expected, neither the geographic location of respondents nor their education level mattered to attitudes.

Shifts in opinion about marriage appear to have occurred across all the individual characteristics of people examined above, but it is most evident when looking at age. Apart from some small inconsistencies between 1994 and 2002, agreement with the statement fell across the board, with the biggest shift from 2003 to 2012. One possibility for this change over time could be that the composition of the respondents has changed in terms of their characteristics. We know that, for example, the percentage of people who are married has decreased over time, and that levels of education have increased. This could account for some of the differences in the views expressed. However, we find that even after taking account of these compositional differences in respondents, there was a large shift in opinion across the years.

Should people who want children get married?

While one third of babies born in Australia today are born outside of a marriage, the majority are still born in a marriage. In this section, we look at how people view the link between marriage and family formation and their level of agreement to the statement: ‘People who want children ought to get married’. Again, the available response categories ranged from Strongly agree to Strongly disagree. Looking at the overall trend from 1989 to 2012, there is a clear decline in the level of agreement. In 1989, 72 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that people who want children ought to get married. By 2012, this had fallen to 47 per cent (see Table 10.4).

As before, we grouped together those who stated they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that people who want children ought to get married, to examine the distribution of answers further. Unlike the earlier question, with regards to childbearing and marriage, men and women appear to have very similar views with little difference between the sexes. The only exception was in 2012 where men were more likely to agree with the statement (54 per cent) than their female counterparts (41 per cent). Once again, age was very strongly related to how they answered the question with older people being significantly more likely to agree compared to young people. However although this pattern is observed in all years, over time agreement has fallen across all age groups (see Table 10.5).

Again, current relationship circumstances heavily influenced responses to this statement. Married and widowed respondents were most likely to express the view that people who want children ought to get married, with single and cohabiting respondents less likely to agree. Interestingly, separated and divorced people still registered high levels of agreement with the statement, indicating that in many cases they still believe people should be married if they want to have children.

Table 10.4: People who want children ought to get married, %.

| 1989 | 1994 | 2003 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 28 | 26 | 24 | 15 |

| Agree | 43 | 44 | 41 | 32 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 |

| Disagree | 13 | 12 | 12 | 25 |

| Strongly disagree | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| Can’t choose | 1 | n/a | n/a | 0.4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Sources: NSSS 1989; ISSP 1994; AuSSA 2003 & 2012.

Whether people lived in an urban or rural area appeared to have little influence on how people answered this question. Education did differentiate, as those with lower levels of education were more likely than those with higher levels of education to support the view that people who want children ought to get married. This could partly be an effect of age as the older cohorts tend to have lower levels of education.

Is marriage an outdated institution?

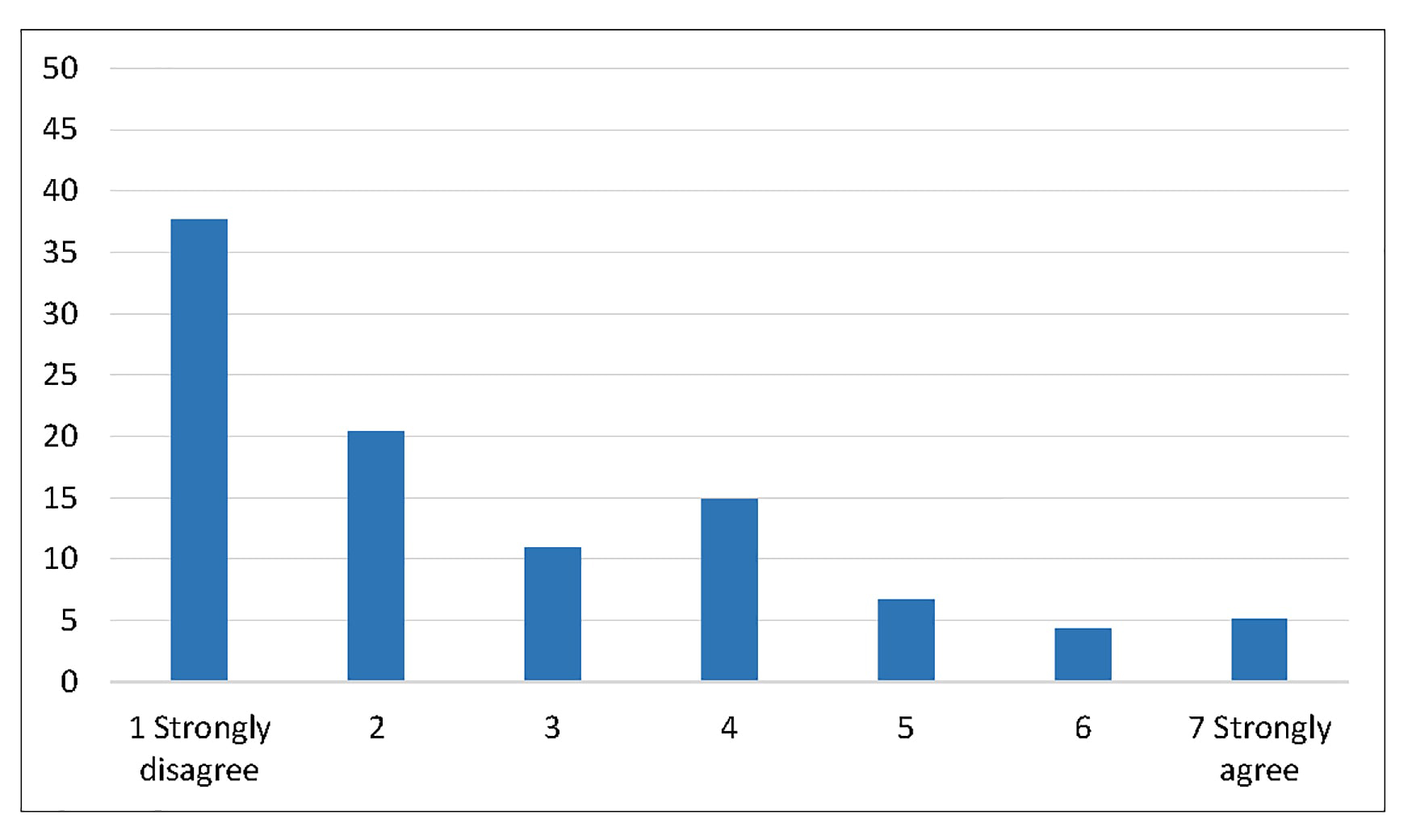

Given the large changes in opinions regarding marriage that have accompanied actual, observed trends in society, it might be tempting to say that Australians now consider marriage an outdated institution. The HILDA survey asked about this in 2005, 2008 and 2011.2 Over this short period of time there was no change in the distribution of responses, so for this section we only show the latest data from 2011. In HILDA, the response categories were presented on a 7-point scale with 1 labelled as ‘Strongly disagree’ and 7 labelled as ‘Strongly agree’. There was a very strong tendency to strongly disagree with this assertion as seen in Figure 10.1.

Those who answered 1 or 2 on the scale were grouped together to see whether any patterns could be detected with regards to not agreeing and a person’s gender, age, relationship status, urban or rural residence and highest education level.

Men were slightly more likely to agree that marriage is outdated (see Table 10.6). However, the difference in how men and women responded to this statement was minimal. Those aged 30 to 49 were most likely to agree that marriage is an outdated institution. Not surprisingly, married people were the least likely to agree, as were those who were widowed. There was no difference between urban and rural respondents. In terms of education there was some indication that those with lower levels of education were more likely to agree that marriage was outdated.

Source: Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey Wave 11, 2011 (N=15,127).

Source: Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey Wave 11, 2011 (N=15,127).

Table 10.5: Percentage agreeing that people who want children ought to get married, by selected characteristics for each year, %.

| 1989 | 1994 | 2003 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 73 | 71 | 68 | 54 |

| Female | 70 | 70 | 64 | 41 |

| Age | ||||

| <30 | 52 | 44 | 42 | 33 |

| 30–39 | 62 | 53 | 48 | 30 |

| 40–49 | 77 | 67 | 63 | 41 |

| 50–59 | 86 | 79 | 74 | 43 |

| 60–69 | 92 | 87 | 83 | 53 |

| 70+ | 96 | 93 | 88 | 80 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married | 77 | –– | 71 | 54 |

| Cohabiting | 41 | –– | 40 | 21 |

| Separated/divorced | 64 | –– | 68 | 45 |

| Widowed | 92 | –– | 77 | 62 |

| Single and never married | 57 | –– | 45 | 35 |

| Urban/rural | ||||

| Rural | 74 | 72 | 68 | 50 |

| Urban | 71 | 70 | 65 | 46 |

| Education level | ||||

| Incomplete secondary | 75 | 77 | 72 | 54 |

| Completed secondary | 66 | 64 | 62 | 43 |

| University | 66 | 60 | 57 | 45 |

| Total % | 71 | 70 | 66 | 47 |

| Total N | 3,988 | 1,662 | 1,215 | 1,421 |

Sources: NSSS 1989; ISSP 1994; AuSSA 2003 & 2012.

We also conducted further analysis to examine the interaction between different factors on the probability of agreeing that marriage is outdated. For the most part men at all ages were more likely to agree that marriage is outdated but particularly men in their 50s. However the difference between men and women was not significant.

What is the future of marriage?

We have shown here that there have been large shifts in attitudes about marriage in Australia, but that these shifts have only occurred in the last 15 years or so. Brown and Wright (2016) also find a similar and equally significant change in attitudes between 2003 and 2012 in the United States. Given the nature of survey data it is possible that this is an artefact of the way survey questions are posed or in the types of people who respond. It is also possible that the exposure that the Australian public has had to changing family types – both in their personal lives and as well as through media – has led to a large shift in how open we are to different ways of forming relationships and raising children. Compared to 20 or 30 years ago, it is now increasingly likely for an individual to know of someone close to them who has never married, who is cohabiting or has had children outside of marriage, who has divorced and formed a new relationship, or is part of a ‘blended’ family. We speculate that the large shift from 2003 to 2012 could be a result of this spread of ‘knowledge awareness’ (Nazio and Blossfeld 2003) through old and new media.

But can we expect further shifts in attitudes to marriage and relationships? What is clear is that most respondents do not think that the institution of marriage is outdated. Perelli-Harris (et al. 2014) show that the nature of marriage is evolving across cultures as individuals manage the changing role of intimate relationships in their lives. It is also likely that the change in Australian legislation to allow same-sex marriage will lead to a reimagining of marriage for both homosexual and heterosexual couples. What we do know is that most Australians still marry and that there is no evidence that marriage will disappear, despite predictions in the media. Perhaps as Cherlin (2004) posits, marriage in Australia has become ‘de-institutionalised’ and lost its practical importance; however, its symbolic importance seems to still be high and, in many ways, getting married is still seen as a marker of prestige. As Lauer and Yodanis (2010) note, new ways of forming relationships and childbearing are not a threat to the institution of marriage; they are just a sign that there are now more partnership options available to people.

Table 10.6: Percentage who agree that marriage is an outdated institution, by selected characteristics, %.

| 2011 | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 |

| Female | 15 |

| Age | |

| <30 | 16 |

| 30–39 | 17 |

| 40–49 | 19 |

| 50–59 | 16 |

| 60–69 | 14 |

| 70+ | 13 |

| Relationship status | |

| Married | 11 |

| Cohabiting | 26 |

| Separated/divorced | 25 |

| Widowed | 12 |

| Single and never married | 20 |

| Urban/rural | |

| Rural | 16 |

| Urban | 16 |

| Education level | |

| Incomplete secondary | 18 |

| Completed secondary | 16 |

| University | 14 |

| Total % | 16 |

| Total N | 15,127 |

Source: HILDA Survey Wave 11 (N=15,127).

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1994). Marriages and divorces, Australia, 1994. Catalogue No. 3310.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2000a). Births, Australia, 2000. Catalogue No. 3301.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2000b). Marriages and divorces, Australia, 2000. Catalogue No. 3310.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010). Marriages and divorces, Australia, 2010. Catalogue No. 3310.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012). Marriages and divorces, Australia, 2011. Catalogue No. 3310.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016a). Births, Australia, 2015. Catalogue No. 3301.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016b). Marriages and divorces, Australia, 2015. Catalogue No. 3310.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Bernard, Jessie (1972). The future of marriage. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Blundson, Betsy (2016). Australian Survey of Social Attitudes, 2012 [computer file]. Canberra: Australian Data Archive, Australian National University. doi: 10.4225/87/57e0d745ba4e8.

Brown, Susan and Matthew Wright (2016). Older adults attitudes toward cohabitation: two decades of change. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 71(4), 755–64.

Cherlin, Andrew J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family 66(4), 846–61.

Easterlin, Richard A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100(19), 11176–83.

Emens, Amie, Colter Mitchell and William G. Axinn (2008). Ideational influences on family change in the United States. In Ideational perspectives on international family change. Rukmalie Jayakody, Arland Thornton and William G. Axinn, eds. 119–150. London: Taylor & Francis.

Evans, Ann (2015). Entering a union in the twenty-first century: cohabitation and ‘living apart together’. In Family Formation in 21st Century Australia. Genevieve Heard, Dharmalingam Arunachala, eds. 13–30. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Evans, Mariah D.R. and Jonathan Kelley (2004). Effect of family structure on life satisfaction: Australian evidence. Social Indicators Research 69(3), 303–49.

Fowers, Blaine J. (1991). His and her marriage: a multivariate study of gender and marital satisfaction. Sex Roles 24(3–4), 209–21.

Gibson, Rachel, Shaun Wilson, David Denemark, Gabrielle Meagher and Mark Western 2004). The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes, 2003 [computer file]. Canberra: Australian Data Archives, the Australian National University.

Heard, Genevieve (2011). Socioeconomic marriage differentials in Australia and New Zealand. Population and Development Review 37(1), 125–60.

Hewitt, Belinda and Janeen Baxter (2012). Who gets married in Australia? The characteristics associated with a transition into first marriage 2001–6. Journal of Sociology 48(1), 43–61.

Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) (2011). Wave 11 [computer file]. Melbourne: the Melbourne Institute, the University of Melbourne.

Hull, Kathleen, Ann Meier and Timothy Ortyl (2010). The changing landscape of love and marriage. Contexts 9(2), 32–37.

Jackson, Jeffrey B., Richard B. Miller, Megan Oka and Ryan G. Henry (2014). Gender differences in marital satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 76(1), 105–29.

Kelley, Jonathan, Clive Bean and Mariah D.R. Evans (1990). National Social Science Survey: Family and Lifestyles, 1989–1990 [computer file]. Canberra: Australian data Archive, the Australian National University.

Kelley, Jonathan, Clive Bean and Mariah D.R. Evans (1994). International Social Survey Programme, Family and Changing Sex Roles II, Austral [computer file]. Canberra: Australian data Archive, the Australian National University.

Lauer, Sean and Carrie Yodanis (2010). The deinstitutionalization of marriage revisited: a new institutional approach to marriage. Journal of Family Theory and Review 2(1), 58–72.

Lee, Kristen Schultz and Hiroshi Ono (2012). Marriage, cohabitation, and happiness: a cross-national analysis of 27 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family 74(5), 953–72.

Lesthaeghe, Ron and Dirk van de Kaa (1986). Twee demografische transities? In Mens en Maatschappij. Ron Lesthaeghe and Dirk van de Kaa, eds. 9–24, Van Loghum-Slaterus: Deventer.

Nazio, Tiziana and Hans-Peter Blossfeld (2003). The diffusion of cohabitation among young women in West Germany, East Germany and Italy. European Journal of Population 19(1), 47–82.

Parker, Robyn and Suzanne Vassalo (2009). Young adults’ attitudes towards marriage: family statistics and trends, Family Relationships Quarterly 12, 18–21.

Perelli-Harris, Brienna, Monika Mynarska, Caroline Berghammer et al (2014). Towards a new understanding of cohabitation: insights from focus group research across Europe and Australia, Demographic Research 31(34), 1043–78.

Qu, Lixia and Ruth Weston (2008). Attitudes towards marriage and cohabitation. Family Relationships Quarterly 8, 5–10.

Stutzer, Alois and Bruno S. Frey (2006). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics 35(2), 326–47.

Thornton, Arland and Linda Young-DeMarco (2001). Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: the 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family 63(4), 1009–37.

Tilley, James and Geoffrey Evans (2014). Ageing and generational effects on vote choice: combining cross-sectional and panel data to estimate APC effects. Electoral Studies 33, 19–27.

Treas, Judith, Jonathan Lui and Zoya Gubernskaya (2014). Attitudes on marriage and new relationships: cross-national evidence on the deinstitutionalization of marriage. Demographic Research 30, 1495–26.

Vanassche, Sofie, Gray Swicegood and Koen Matthijs (2013). Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross-national differences in the effects of marital status and children on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 14(2), 501–24.

Williams, Kristi (2003). Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44(4), 470.

1 In this chapter we refer to de facto and cohabiting couples interchangeably.

2 This chapter uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.