9

Controlling tobacco supply and the endgame

Comprehensive tobacco control, as embodied in the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), mandates a range of strategies to reduce tobacco use, including taxation, bans on tobacco advertising, labelling products with effective health warnings, regulation of contents and emissions, conducting public awareness campaigns, reducing exposure to second-hand smoke and promoting cessation (Guindon, de Beyer et al. 2003). Supply-side strategies in the FCTC include preventing illicit trade, providing economic alternatives to tobacco growers and preventing sales to minors. However, other than banning point-of-sale advertising and retail pack displays as residual forms of tobacco advertising, a supply side strategy that has only been minimally explored is the regulation and licensing of tobacco retailing and purchasing, and the introduction of retail floor prices for tobacco.

Below is an edited and updated version of a paper on these issues that I published with my colleague Becky Freeman in 2009 (Chapman and Freeman 2009).1

Licensing of tobacco retailers is uncommon in global tobacco control. While there are jurisdictions such as Canada, Australia, the USA and Singapore that require some form of retail licensure, the applicable conditions are minimal and removal of licence for breaching licensing conditions is rare.

Most tobacco retail regulation and licensing are based on the objective of restricting sales to adults. Consequently, most research on retailing has focused on monitoring sales to minors and the effects of enforcement practices and threats of fines on underage sales. While threats of fines can reduce sales, there is little evidence that such reductions translate to reduced use, because of the ease with which youth can acquire cigarettes through purchases made by older friends. Even though these jurisdictions sometimes stipulate loss of licence as a penalty for multiple violations for sales to minors, there is little evidence that this is ever invoked and no research literature demonstrating the utility of this threat as a serious deterrent. This is undoubtedly why the tobacco industry has long publicly tut-tutted about the terrible problem of youth smoking and offered to work with governments to reduce youth access to tobacco. It is symbolic, empty-gesture tobacco control designed to give the industry a foot in the door of government tobacco control discussions while the companies know it will do nothing to seriously reduce youth access (Assunta and Chapman 2004, Knight and Chapman 2004).

Unlike every other facet of tobacco advertising, packaging, and retail (non) display of packs, tobacco retailing throughout the world today remains almost entirely “normalised”: tobacco products can be sold by virtually any business which chooses to do so. We will now consider how regulation of tobacco retail environments might be widened from a sole concern to reduce sales to minors in the effort to further denormalise and thereby reduce tobacco use. It is based on a central concern to send an unambiguous public signal that governments regard tobacco as an exceptionally harmful product, deserving of retail sale restrictions at least as comparable to those that apply to prescribed pharmaceuticals in almost all countries.

We’ll consider licensing provisions and their rationales established by governments for a range of goods and services. These restrictions are often introduced because of health considerations with parallels to the goals of tobacco control. We’ll conclude that the major impediment to greater regulation of the tobacco retail environment is the historical regulatory trivialisation of tobacco products compared to assumptions made about other regulated products. We argue that concerted efforts will therefore be needed to change this assumption, if tobacco products are ever to be subject to the same range of serious and enforced regulatory requirements taken for granted for many other items of commerce, particularly pharmaceutical drugs. If this was to occur, potential exists for regulatory provisions to be introduced in five broad areas of tobacco retailing in addition to restricting sales to adults:

- Restrictions on the number and location of tobacco retail outlets

- Regulation of tobacco retail displays

- Floor (minimum) price controls

- Restricting the amount of tobacco that smokers could purchase over a given time

- Loss of retail licensure following breaches of any of the conditions of licence.

We’ll discuss each of these and then explore the idea that tobacco retail licences could become valued, tradable commodities in a policy environment based on the objective of limiting the number of tobacco retail outlets. Such a reduction could reduce the convenience of purchasing tobacco products and the frequency with which smokers and ex-smokers would encounter tobacco supplies in their local communities, a factor known to cue thoughts of purchase and smoking in smokers and ex-smokers (Wakefield, Germain et al. 2008).

Regulation of other goods and services

Consumers and the business sector are very familiar with the concepts of licensing and registration through a wide variety of requirements. All motor vehicle drivers and boat owners are required to be licensed and vehicles and sea craft registered. In Australia, all dogs must be registered to owners and those who wish to keep exotic animals such as reptiles must have a licence to do so. In many countries firearms can only be sold by licensed operators to those with firearm licences under very strict conditions. Food preparation and sales are also commonly subject to stringent licensing and safety inspections. In order to protect the health and safety of the public, many service professions and occupations must be licensed to legally carry out their tasks: doctors, dentists, pharmacists, electricians, plumbers, pesticide services, civil engineers, taxi drivers, and tattoo and body piercing artists are just a few examples. In this light, tobacco retailing stands out as being a curiously unregulated commercial enterprise, given the magnitude of problems arising from its commercial activity.

The licensing of purveyors of other potentially harmful products and services is based on a far wider range of concerns than simply preventing youth access, such as protecting personal and public health, safety and welfare; controlling provision and limiting availability; monitoring sales; and ensuring quality and accountability. Much licensing and regulation on a wide variety of goods and services is based on better ensuring that consumers are not harmed by the products or services they purchase.

It has often been observed that tobacco’s status as a product sold with few restrictions reflects the historic, gradual emergence of knowledge of its harm and the unwillingness of governments to respond to this harm in the way they would to any newly developed product known to cause such harm, by refusing to allow such a new product onto the market. But with tobacco having no safe level of use, and 181 governments being parties to the FCTC with its central goal of reducing tobacco use, the historical laissez faire attitude toward the regulation of tobacco retailing is anachronistic and incompatible with this broad goal.

Pharmaceutical retailing as a model

The inconsistent, ramshackle and poorly enforced situation of tobacco retailer licensing across Australian states and territories today contrasts markedly with the ways in which therapeutic goods (pharmaceuticals) are retailed. There is a regulatory paradox here as the government formally acknowledges that, while tobacco products cause unparalleled harm to health, it minimally regulates their sale. By contrast, pharmaceutical products designed to enhance health are heavily regulated so that the possibility of harm from unlimited access is reduced.

Virtually every aspect of pharmaceutical retailing is subject to government regulation: from which products can be sold, to where a pharmacy can be located, which staff can dispense certain pharmaceutical categories, where products can be stored and displayed, the amount of product that can sold to each customer and what the pharmacist must communicate to customers about some dispensed products. The cost of pharmaceuticals partly reflects these regulatory costs. So how might such conditions be applied to tobacco retailing?

To sell scheduled drugs, pharmacists must have a pharmacy degree, maintain their registration and would face severe penalties, including possible imprisonment, if they were found to be selling some categories of drugs without being presented with a valid doctor’s prescription.

By contrast, there are no restrictions on who can sell tobacco products, nor on where they can be sold. Accordingly, the retailing of tobacco products is ubiquitous: from all supermarkets and almost every corner store through to suburban barbers, who typically keep a few packs adjacent to gum and hair care products. The subtext of the current way tobacco products are sold is that they are in every way unexceptional, ordinary items of commerce, suitably treated in the same way that everyday grocery items are sold and undeserving of special restrictions. This view is inconsistent with the way that tobacco is regarded under many other aspects of tobacco control policy and may undermine public understanding of how seriously tobacco damages health. For example, in 1991 when tobacco advertising remained legal in Australia, a third of smokers agreed with the proposition that “If smoking was really harmful, the government would ban tobacco advertising” (Chapman, Wong et al. 1993). It is possible that the unrestricted retailing of tobacco may send a parallel message.

Following the publication of a report from a 2020 Senate committee on tobacco harm reduction convened by two political champions of “light touch” vaping regulation who were outvoted by the majority of their committee (Australian Senate 2020b), in 2021, the Australian government mandated that all nicotine liquid and NVPs would require a doctor’s prescription (see later in this chapter). This policy decision was supported by the overwhelming majority of relevant professional health bodies in Australia, but implacably opposed by the three tobacco companies dominating the Australian market (each of which is heavily invested in NVPs) and a ragbag of tiny vaping lobby groups either funded directly by the industry or operating as astroturf “independent” groups with funding channelled through third parties.

Opponents of the proposal thought they were onto a winning argument by continually contrasting the open-slather, “sold everywhere” way that tobacco products have always been retailed – with restrictions on selling NVPs. Their view was that the NVP access should match that of tobacco and not be more restrictive. In effect they were arguing, “Let’s repeat the same mistakes we made in allowing open slather sales and promotions with cigarettes.”

But, more fundamentally, the stratospheric dangers of smoking were not fully understood for at least 40–50 years after mass consumption and the commerce that facilitated it had commenced in the first decades of the 20th century. After mechanisation of cigarette production made cigarettes as cheap as chips, it then took us 40–50 years between the 1960s and today to fight for all the policies and campaign funding that have together taken smoking down to its lowest ever levels.

Out of ignorance and under sustained pressure from the tobacco industry, the tobacco epidemic saw nations make every regulatory mistake possible when cheap, mass-produced cigarettes appeared on sale almost everywhere. Our understanding of the health risks that may be posed by NVPs is in its early infancy, given the latency periods that apply with the development of chronic disease (see Chapter 6).

It is often said that if cigarettes were invented tomorrow, and we knew now what we didn’t know when they entered the market, no government in the world would permit their sale, let alone allow them to be sold in every convenience store.

With pharmaceutical products that save lives, treat illness and reduce severe pain, we allow only people with a four-year pharmacy degree to sell them. And only to those with a temporary licence issued by a doctor (a prescription) to use them. With cigarettes, we foolishly allow them to be sold everywhere.

Restrictions on the number and location of tobacco retailers

Numerous precedents exist for the government imposing restrictions on the number and location of various commercial activities. These restrictions are imposed for reasons including urban aesthetics, public amenity, to limit competition for certain retail activities deemed important to remain economically viable in local communities and delivered at a high standard to consumers, or (as might be argued for tobacco) to reduce the proliferation of businesses deemed less socially desirable (e.g. nightclubs which might attract large, noisy crowds in residential areas, firearms dealers, brothels, X-rated video outlets). Urban areas are often zoned residential or industrial, and from this flow restrictions on the types of business that can operate in residential zones. A person cannot decide to turn their residence into, for example, a restaurant, a brothel or a childcare centre without the permission of zoning and licensing authorities.

The arguments for reducing access to tobacco products are driven by the same core reasons for why 181 nations have ratified the WHO’s FCTC: that smoking kills two in three of its long-term users (Banks, Joshy et al. 2015) – some eight million a year at present; that many other commodities which cause even a small fraction of such deaths are banned, e.g. lead in petrol and paint; asbestos in brake linings and building insulation; fireworks (Abdulwadud and Ozanne-Smith 1998); semi-automatic firearms in civilian ownership (Chapman 2013); often subject to strict regulatory control (e.g. pharmaceuticals, food additives, pesticides, and industrial and agricultural chemicals), or subject to recalls or market withdrawal (e.g. many examples of unsafe consumer goods, motor vehicles (Hemenway 2009)).

Tobacco and cigarettes have enjoyed the legacy of being sold as ordinary, largely unregulated consumer items for well over 130 years. While advertising, packaging, tax and smoke-free regulations have been widely introduced throughout the world across the last 70 years, moves to reduce and more strictly control the number of retailers and their conditions of operation are barely in their infancy.

Possible models might range from the nationalisation of tobacco retailing involving a single network of government-controlled outlets (as with alcohol in Sweden) to a model where a highly restricted number of licences based on an agreed number of tobacco retail outlets per 100,000 population could be auctioned to the highest bidder. Objections from current sellers unable to compete for such licences could be met with many precedents where major restrictions on previously open-slather retailing have been introduced in attempts to limit use.

This raises the interesting possibility that if tobacco retail licences were to be made mandatory across the country, similarly limited and the conditions pertaining to the conduct of a tobacco retail business strictly regulated, a tobacco retail licence could become a highly valued commodity promising restricted, profitable retailing access. The issuing of taxi licence plates in Australia is similarly strictly limited and prior to the advent of competition from Uber, these plates traded at prices many times higher than the value of the actual taxi itself. Retailers who risked having their retail licence revoked by breaching any condition of licence would thus risk losing a valuable asset. Provided governments acted against such breaches, this would seem a potential way of introducing large incentives to obey the law on matters, such as restricting sales to adults and enforcement of display bans.

Globally, alcohol retailing is subject to many such controls. These include: nationalisation of alcohol distribution, limiting hours and or days of sale, restrictions at community events, restricting the location, density and types of alcohol outlets, mandatory server training, and licensing and server liability. When granting liquor sales licences, community and social factors are often considered. For example, in New South Wales when applying for a liquor licence, applicants must include a National Police Certificate, a community impact statement, a scaled plan of the proposed licensed premises and a copy of the local council’s development consent or approval for the proposed premises. The community impact statement summarises the results of consultation by applicants with local councils, police, health, Aboriginal representatives, community organisations and the public.

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 international studies looking at the relationship of tobacco retailing density and proximity to smoking prevalence concluded: “Across studies, lower levels of tobacco retailer density and decreased proximity are associated with lower tobacco use” (Lee, Kong et al. 2021).

Canadian researchers have measured the effect of tobacco outlet density around schools in Ontario and found that the “more tobacco retailers there were surrounding a school, the more likely smokers were to buy their own cigarettes and the less likely they were to get someone else to buy their cigarettes” (Leatherdale and Strath 2007). New Zealand research suggests that accessibility to retail outlets selling tobacco may not impact on national smoking rates. The researchers found that after controlling for individual-level demographic and socioeconomic variables, individuals living in neighbourhoods with the best access to supermarkets and convenience stores had higher odds of smoking compared to individuals in the worst access neighbourhoods. However, the association between smoking prevalence and neighbourhood accessibility to supermarkets and convenience stores was not apparent once other neighbourhood-level variables (deprivation and rural location) were included (Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2009). The authors suggested that restrictions on the number of tobacco outlets in residential neighbourhoods, and area-based restrictions, such as those with a high concentration of workplaces, may influence the consumption of tobacco. If tobacco retail outlets were to be limited, causing smokers to have to plan their purchases more, this may reduce “spontaneous” purchases which had not been pre-planned. If this policy was implemented in concert with price controls and limits on the number of cigarettes purchased (see both arguments below), this may reduce consumption.

Be careful what you wish for?

There are, though, several critically important concerns that need thorough investigation before such policies should be enacted. First, it seems intuitively obvious that in areas with low smoking prevalence, we would expect to find fewer tobacco retail outlets than in areas where there are more smokers. Basic due diligence about setting up a tobacco outlet would see retailers doing their homework and working out the most promising locations. Investing in establishing a tobacco business in an area with low smoking prevalence (e.g. high socioeconomic suburbs) would not be very sensible. By analogy, there are very few farm machinery shops or agricultural supply shops in cities, but plenty in rural towns.

So top-line findings of a positive association between retail outlets and smoking prevalence are likely to be highly predictable and an example of “Gosh, who’d have ever imagined!” research. The implied policy message is “if you regulate to reduce retail outlets, we’d predict this would drive down prevalence”. But it might be more a case of when smoking prevalence is low or falls – perhaps because factors like rising socioeconomic status and house prices in certain suburbs – reverse causality is at play, and the lower local demand for tobacco is reflected in tobacco businesses closing or not setting up, not the other way round.

Second, 20 years ago in Australia, every suburb would have several outlets selling take-out alcohol not to be drunk on the premises, and every pub would have a takeaway section. But today almost all alcohol retailing is done by a supermarket duopoly: 76% of liquor retailing is via these two supermarkets or their liquor barn subsidiaries, with a declining 10.7% via small, typically suburban liquor stores, and the remainder sold through takeaway from pubs (Hinton 2021). These fiercely compete for the liquor market via price discounting and home delivery free for orders over $100.

Might the same not happen with reduced tobacco access policy if the outlet reduction policy was taken up? Supermarkets are already the largest tobacco retailers, with over half of all tobacco sales (Bayly & Scollo 2020). Might not this see huge concentration of tobacco retailing, leading to margins being squeezed down even further and smokers getting cheaper deals, causing an uptick in sales because of price’s critical role in demand elasticity?

Parallel floor price policy (discussed below) would be essential, as would thorough vigilance of the industry’s efforts to circumvent the law by all manner of marketing subterfuge.

Third, retailing (especially since COVID-19) has radically changed with online buying and home delivery, and more broadly with the drift to massive shopping centres which shoppers drive to and from. Online purchasing allows warp-speed price comparisons with reduced prices because online retailing avoids large retail shop costs. Old assumptions about proximity of retailing to residence being important are looking very shaky in many locations.

Regulating tobacco retail display

Scheduled drugs which either require a doctor’s prescription or which are subject to limited supply mediated and registered through a pharmacist must be stored in a part of the pharmacy designated as a dispensary. The dispensary is an area in which members of the public are not permitted to enter, and therefore are unable to handle (and potentially shoplift) drugs stored there. Many dispensaries store prescription-only drugs out of sight of customers. The same principle should apply to tobacco retailers: products should not be displayed. Research has shown that retail displays of tobacco prompt unplanned purchases and weaken resolve not to smoke (Wakefield, Germain et al. 2008, Carter, Mills et al. 2009, Carter, Phan et al. 2015). A WHO evidence brief describes the evidence underpinning display ban policy (WHO Europe 2016).

Iceland was the first nation to implement a display ban in 2001, but since then only ten other nations have followed (Australia, Canada, Croatia, Ireland, Serbia, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, Thailand and the UK) (Wikipedia 2021b). Clearly, there remains huge potential to pick up the international implementation pace of this policy.

Floor price controls

Everyone reading this will have experienced shopping for discounted prices on goods. Like all other non-luxury goods manufacturers, tobacco companies are well aware that lower prices attract purchasing and they engage in many forms of discounting to chase sales. Price controls are often reluctantly imposed by governments in free markets, with retail price competition being regarded as a sacrosanct principle of such markets. However, again there are many precedents for governments imposing minimum unit or floor price controls in situations where various national interests are invoked.

The notions of floor and ceiling prices (a price specified as the lowest or highest legal purchase price of a good or service that can be charged) exist for many commodities in agriculture, in rent control and for minimum wages. Prescribed pharmaceuticals are subject to price controls in Australia to ensure their accessibility to all who need them. In regulating retailing, governments could establish a floor price for tobacco products, below which it would be illegal to sell them. This would limit serious discounting if competition were to be further concentrated as I suggested above if policies on limiting tobacco retail outlets were pursued.

Canadian provinces led the way on floor prices with alcohol (Stockwell 2014) and in 2018 Scotland became the first nation to introduce minimum unit floor prices for alcohol (Robinson, Mackay et al. 2021). The Queensland government has legislated to restrict price discounted “happy hours” and banned hoteliers offering free drinks (Business Queensland 2019). In Sweden, all alcohol is sold via the government monopoly Systembolaget which “exists for one reason: to minimise alcohol-related problems by selling alcohol in a responsible way, without profit motive”.

In the USA, as at 2011, 25 states and the District of Columbia had minimum purchase price laws that applied to cigarette sales. These laws originated to protect small businesses, not public health. Cigarette prices in these states tend not to be any higher than in states without such laws, as price discounts offered to retailers as promotional incentive programs are not used to calculate the minimum price (Tobacco Control Legal Consortium 2011). Minimum price policies will be more effective in keeping cigarette prices high if price discounting from manufacturers or wholesalers to retailers was not permitted.

Limitations on the number of cigarettes a smoker could buy

When a person is prescribed a drug by a doctor, the prescription specifies that a limited supply be released by a pharmacist. Patients requiring further supplies can then return to a doctor for a repeat prescription, allowing the doctor to determine whether further supplies are necessary; to monitor the patient’s health; and if necessary, change the dose. A doctor’s prescription is, in effect, a temporary licence to consume a particular drug.

With tobacco, smokers are at liberty to buy unlimited supplies. Under a policy governed by the explicit objective of reducing consumption and encouraging cessation, governments could introduce a regulation stipulating an upper weekly limit to tobacco product purchases. To facilitate this, smokers’ permits or licences could be introduced incorporating a sliding scale of fees, with substantially higher fees acting as a disincentive to allow purchase of more than 15 cigarettes a day, just above the current average consumption, and a cheaper but still substantial licence allowing purchase of, say, five per day. An attractive cashback provision could be incorporated as an incentive for people wishing to permanently surrender their licence when they quit.

As discussed earlier, the great majority of smokers regret ever starting (Fong, Hammond et al. 2004), and in excess of 40% make an attempt to stop every year. I have never met a former smoker or heard one speaking in the media who regretted quitting. Many smokers are therefore likely to support such a policy in the way that many support other tobacco control policies which act as a brake and disincentive to the smoking they wished they’d never started (Edwards, Wilson et al. 2013).

In 2012, I set out the case for a smoker’s licence in full in a paper in PLOS Medicine together with detailed exploration of objections to this idea (Chapman 2012). In summary, all adult licence holders would be issued with a swipe smart card licence calibrated to show the number of cigarettes that could be purchased in a given period, with an upper limit set to thwart anyone planning to on-sell on a large scale to unlicensed smokers. Smokers wishing to set limits to their own consumption would be free to set their own maximum number of cigarettes able to be purchased over a period. No sales would be possible without a swipe card licence, with all sales electronically reconciled against issued licences. COVID-19 rapidly accelerated global familiarity with QR code sign-ins and declarations of vaccination status. This technology could be very easily adapted to incorporate a smoker’s licence (An 18-minute video explaining the concept is at https://tinyurl.com/27f2nms5).

Communities in all but the most impoverished nations have long accepted that to obtain a prescribed drug, a person must first visit a doctor, be assessed as requiring the prescribed drug, pay the doctor a fee, obtain a prescription, find a pharmacy and pay the pharmacist for the drug, sometimes subsidised by governments. I am not suggesting that smokers would have to obtain a doctor’s prescription to buy tobacco, but that limitations should be placed upon the ability of smokers to acquire unlimited tobacco products, with the device of a smoker’s licence acting like a de facto prescription to obtain a limited supply.

In December 2021, New Zealand became the first nation to announce adoption of the concept of the smoke-free generation. The central provision here is that from a date to be proclaimed sometime in 2022, it would be henceforth illegal for any tobacco retailer to sell tobacco products to anyone born after a particular year. Media comment suggested that this would be age 14, and that this would increase by one year on the anniversary of the 2022 proclamation. In other words, commencing sometime in 2022, anyone born later than 2008 would not legally able to ever be sold tobacco products (Ministry of Health New Zealand 2021a).

It has long been illegal in New Zealand to sell tobacco to people aged less than 18. Yet 18% of minors who are smokers report buying cigarettes (Lucas, Gurram et al. 2020). Prosecutions of shops selling to minors are uncommon to rare in most nations. So the 2021 announcement begs the question of the extent to which it would be actively implemented, given this history. The introduction of mandatory, sales-linked proof-of-age documentation via a government app with this being reconciled against retailers’ tobacco stock data would go a long way to prevent retailers from ignoring the new regulation. Without such a measure, it is difficult to be optimistic that much would change in the age-old reality of many retailers being willing to ignore the law.

Loss of licensure following breaches of conditions of licence

In the states where retail tobacco licences exist, revocations of such licences are unheard of in Australia. Occasionally tobacco retailers have been fined for selling tobacco to minors, but the likelihood of this occurring is so rare that many retailers clearly reason that it is simply part of the cost of doing business with minors. In Canada, suspension of a licence can follow conviction for selling to minors, but not removal of licence. This is not the case in many jurisdictions for those repeatedly supplying alcohol to minors, where liquor suppliers can lose their licence. In the professions, doctors, lawyers and accountants are delicensed or barred from practice following successful prosecution of breaches of their professional duties. A pharmacist, for example, found to be selling restricted drugs to those without prescriptions would be subject to investigation, leading to possible prosecution and loss of registration as a pharmacist.

If retailing was concentrated in fewer outlets by the limitations I described on the number of outlets, the stakes involved in licence loss for what would then be large-scale retailers would be enormous. Selling to underage smokers would thereby be hugely disincentivised. By restricting the number of tobacco licences issued and allowing them to be tradable, loss of licence would loom as a highly significant disincentive to breach any of the conditions of licensure.

The trivialisation of tobacco retailing lies at the root of why most of the above provisions do not operate in any nation today. None of these provisions will be taken seriously by governments until tobacco retailing is radically reframed in public and political consciousness in the ways analogous with the range of absolutely normal, taken for granted controls that have long applied to pharmaceutical retailing. Concerted and imaginative effort will be needed to transform public perceptions of tobacco retailing away from its current laissez faire status as just another ordinary grocery item.

Prescription access to nicotine vaping products

From 1 October 2021 any Australian wanting to legally vape nicotine has been required to have a doctor’s prescription (Therapeutic Goods Administration 2021b). The policy has been very welcomed by nearly all public health agencies, professional bodies and state health departments. Goods which require a prescription can only be retailed through pharmacists in Australia. Provision also exists for vapers to import NVPs provided the imported goods arrive in Australia with a genuine copy of the prescription in the packaged goods. If targeted or random customs inspections find unauthorised NVPs, the goods are seized and the importer fined significantly (Therapeutic Goods Administration 2021a).

The only interest groups which have been apoplectic about the policy have been all three major tobacco transnationals marketing in Australia (all have NVPs), the small number of vaping shops which are now unable to sell vapable liquids containing nicotine – as has always been the case in Australia – and want a slice of the action; convenience stores (for the same reason); a coterie of conservative backbench federal politicians; and a small rabble of vaping advocacy groups.

Why regulate NVPs?

Vaping interests have long been engaged in a global effort to rehabilitate nicotine’s reputation. They are usually fine in agreeing that nicotine is addictive, but bend over backwards to promote it as being all but benign. “As risky as coffee” is a trivialising comparison commonly used. In 1976, the late addiction specialist Michael Russell wrote that “People smoke for nicotine but they die from the tar” (Russell 1976). This has become a mantra for vapers against their pet evil of nicotine regulation, rarely absent from any interview. But in fact across the 46 years since Russell wrote those words, a large research literature has emerged on concerns about nicotine’s likely role as a cancer promoter (Schaal and Chellappan 2014), as a vasoconstrictor with major implications for cardiovascular disease (Kennedy, van Schalkwyk et al. 2019), as a disruptor of cognitive development (Goriounova and Mansvelder 2012) and as a possible cause of psychosis (Quigley and MacCabe 2019). I have assembled a large collection of published research on concerns about nicotine (Chapman 2019).

For these reasons, and because of the strong addictive potential of nicotine in NVPs (Jankowski, Krzystanek et al. 2019), Australia’s TGA has long sensibly classified nicotine as a poison or a therapeutic substance when used in small doses (Therapeutic Goods Administration 2017).

Vaping advocates are fond of arguing that because nicotine is freely available in tobacco products, it follows that nicotine for vaping should enjoy at least the same, if not more accessibility and be freely sold almost anywhere. This argument has all the integrity of a chocolate teapot. Cigarettes were given their unregulated commodity status at the beginning of last century, long before the evidence accumulated about two in three long-term users dying from smoking (Banks, Joshy et al. 2015). Vaping advocates insisting that NVPs should share a regulatory level playing field with cigarette accessibility seem happy to risk repeating the Sisyphean task we have faced with tobacco of trying to reduce the damage that 120 years of non-regulation has facilitated. It’s been 56 years since health warnings first appeared on tobacco packs and tobacco control commenced. The power of the tobacco industry has ensured that the legislative drag has nearly always been glacial.

Nicotine should not be exempted from regulation

Every new therapeutic substance first made available to the public is regulated in all but politically chaotic nations where almost anything can be bought over the counter in any quantity. Vaping advocates seem to believe their virtuous mission should exempt NVPs from regulation, despite their every second sentence extolling the therapeutic virtues of vaping in cessation and harm reduction, thus catapulting it straight into the ambit of therapeutic regulation.

When NRT first became available in the 1980s in gum form, in every country it was sold it was scheduled as a prescription-only drug. No one thought this was anything other than sensible and normal for a new drug. When nicotine patches, lozenges and inhaler sprays later appeared, they too were prescription-only. Over the years, as use of NRT proliferated and some ex-smokers used it for many years with only minor apparent adverse effects, NRT access was gradually liberalised through rescheduling. Approved maximum doses, however, have remained small through concerns about toxicity.

Drug scheduling can work in the opposite direction too. The very useful opiate, low-dose codeine, was available OTC in Australia in a variety of pain-relieving medications until February 2018. Following accumulating evidence of abuse and harm, it was then rescheduled to prescription-only access (Cairns, Schaffer et al. 2020).

Alex Wodak, an unswerving advocate for open access to nicotine vaping juice, has argued that “Vaping is to smoking what methadone is to street heroin” (Wodak 2020). Correct. But curiously Wodak failed to note that methadone is only available via special prescription authority, dispensed at some pharmacies and clinics. In 2020, on a census day, 53,316 persons across Australia were being treated for their opioid dependence with prescribed methadone, buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021). Australia’s new regulations will make nicotine vape juice available in much the same way, but in potentially every pharmacy.

I’m not aware of Wodak advocating for methadone to be available to whoever wants to buy it from any retailer wanting to sell it, in just the way that cigarettes can be sold. But if he does hold such views, good luck in selling that argument.

Prescribed access will greatly reduce teenage access to e-cigarettes

As discussed in Chapter 6, smoking rates in Australian teenagers have never been lower (Greenhalgh, Winstanley et al. 2019), a phenomenon also seen in other nations like the USA, Canada and the UK which, like Australia, also have had comprehensive tobacco control policies for decades. Like the tobacco industry, the business model for the vape industry (Chapman 2015), which includes all major tobacco companies, is not just about promoting its products to current adult smokers. Just as any car company which ignored young first car buyers would need its corporate head examined, all tobacco and vaping companies are well aware of the critical role that new (read “young”) nicotine addicts have in their long-term commercial prospects. Reports have found 45% of US vaping retailers (Rapaport 2019) and 39% of English shops (Smithers 2016) sell to underage customers.

Vaping advocates are usually sensitive to the reception that any expressed complacency about teenage vaping will cause, and so concentrate talk about their mission on helping smokers switch. But as the evidence about rising youth vaping uptake has accumulated and become undeniable, they fall back to, “Well, isn’t it better that they vape than smoke?” As discussed in Chapter 6, successful tobacco control has succeeded in getting teenage smoking down to near rock bottom. Data released on 10 December 2021 by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for 2020–21 showed only 2% of 15–17-year-old Australians smoke (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021a). So we are supposed to all concur that the huge, widespread problem of 2% of teenagers smoking is being kept on the leash by burgeoning rates of teenage vaping?

The wider-than-Sydney-Harbour-heads problem here is that many totally nicotine-naïve youth are now regularly – not just experimentally – vaping. In the USA “The significant rise in e-cigarette use among both student populations has resulted in overall tobacco product use increases of 38 percent among high school students and 29 percent among middle school students between 2017 and 2018, negating declines seen in the previous few years” (US Food and Drug Administration 2019).

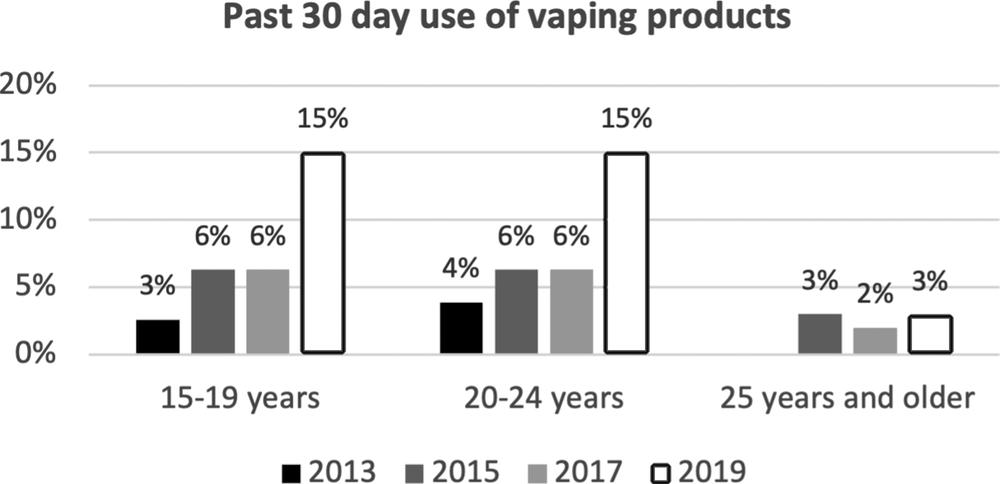

In Canada, vaping skyrocketed in teenagers and young adults between 2017 and 2019 after being made openly accessible in 2018.

Figure 9.1 Past 30-day use of vaping products, by age groups, Canada 2013–19 (Source: Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada 2020).

Most vaping advocates have always been careful to stress that the putative benefits of vaping are all about adult smokers who want to quit smoking. You won’t hear many of these people publicly thrilling to the data I showed in Chapter 6 on the large proportion of adults who vape and smoke and who have no interest in quitting smoking. Nor to that on long-term ex-smokers taking up vaping. And especially to data on the huge momentum in nicotine-naïve kids taking up regular vaping.

With prescribed legal access to vapable nicotine now mandatory in Australia, two factors are currently in play which together seem likely to greatly diminish access by kids.

First, because only pharmacies are authorised to fill prescriptions, no businesses other than pharmacies are allowed to sell NVPs in Australia. In the early months of the policy, public health agencies have been reporting a steady stream of breaches of these regulations, with large fines being issued by the TGA (see Therapeutic Goods Administration 2021c, Therapeutic Goods Administration 2021a). This is a marked contrast to the rare prosecutions taken against retailers who sell cigarettes to minors.

Illegal flavoured disposable vapes being sold in convenience stores, online and at markets currently remain highly accessible. COVID has seen many health department staff seconded to other COVID-related duties, so surveillance and inspection efforts have been reduced.

Second, very few doctors would issue a NVP prescription to a child. On-sellers thinking that they could shop around doctors to get multiple prescriptions and then supply the feverish teenage demand will be easily traced via their Medicare number used in paying for their prescription.

A major Achilles heel here is that the personal importation scheme, preserved after pressure from conservative backbench MPs in 2021, needs to be urgently revoked. Those with a prescription can send a copy to an exporter in another country who can then send NVPs to the authorised personal importer. With hundreds of millions of international items arriving by post and courier into Australia every year, clearly any attempt at thoroughly screening these for unauthorised NVP imports or those with fake prescriptions will be hugely inefficient. Growing anger in the public health and school sectors over widespread access by children seems certain to increase. Inconsistencies in personal import regulations between tobacco and NVPs loom as a potent leverage point in advocacy for revoking personal NVP importation. It has been illegal since 2019 to personally import cigarettes into Australia beyond one duty-free pack carried by arriving travellers (Australian Border Force 2021). Maximum fines for unauthorised importation of NVPs currently stand at $220,000. This risk will deter many individual vapers as well as criminals intending to on-sell in bulk.

If, as most political forecasters are predicting, there is a change of government in Australia in 2022, the votes of Labor, the Greens and progressive independents will easily ensure that such a revocation will occur.

Will Australian doctors be willing to prescribe nicotine?

A weakness with this scheme is the possibility that into the future, only a few doctors will be interested in prescribing access to nicotine juice. Before the scheme was made mandatory, fewer than ten doctors out of over 122,000 registered medical practitioners across the country were said to be doing this, with an unknown but desultory number of prescriptions being issued as a result. This hugely underwhelming participation rate was largely explained by the ability of vapers and others to easily import nicotine juice, making going to a doctor to get an authority to buy nicotine from a compounding chemist uncompetitive. As this importing ability was regulated from 1 October 2021, more Australian doctors may now be willing to prescribe. But it is possible that with nicotine continuing to have what the TGA calls “unapproved product” status as a drug (Therapeutic Goods Administration 2021), many doctors will remain uninterested. Challenging legal issues may arise in the event of an adverse reaction or health problems arising from vaping nicotine which had been obtained via a prescription. It is conceivable that such patients may seek redress from doctors who issued the authority for them to use such an unapproved substance.

The end for combusted tobacco?

Throughout my career, I’ve been urged to support and advocate for a wide range of policies and campaigns. I have always tried to be assiduous in considering the ethical implications of any tobacco control policy. To the annoyance of some of my more “whatever it takes” colleagues, I wrote several detailed papers (Chapman 2008a, Darzi, Keown et al. 2015, Chapman 2000) that were critical of proposals that smoking should be banned in wide open spaces like parks and beaches because there is no evidence that the fleeting exposures others may experience in such contexts are harmful (Licht, Hyland et al. 2013). I support a ban on smoking inside prison buildings because the minority of prisoners who do not smoke should not be forced to be exposed to second-hand smoke for the lengthy hours that prisoners are locked in often shared cells every day. But I support prisoners being allowed to smoke in open air sections of prisons. All serious epidemiology on the harmful effects of second-hand smoke exposure has shown that it is chronic exposures in enclosed domestic and occupational settings, not fleeting exposure outdoors, that causes disease.

I also declined to join those who believe that the state should be able to instruct movie directors to censor scenes of smoking under the threat of having their movies rated R (over 18 years old), which can have major negative box-office receipt consequences (Chapman and Farrelly 2011). To me, the assumption that public health goals should be able to be used to justify intrusion into the content of cultural, artistic or cinematic expression is dangerous and redolent of the playbooks used by authoritarian political regimes. Once precedents are set, conga lines of advocates for a wide variety of censorship and restrictions on personal conduct, often passionately espoused as being for the good of society, queue up to prosecute their visions for a better society. History is full of episodes of horrendous persecution of individuals and groups who want to express their beliefs or behave in ways that meet the disapproval of others.

I have often been asked by journalists, interviewers, students and members of the public whether I support the banning of tobacco. Across a 45-year career, I have never once advocated for smoking to be banned. My reasoning here has nothing to do with my strong agreement that smoking already kills some eight million people a year and harms many more. It is rather that the acid test of the ethics of stopping people from doing various things has always been the 19th-century utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill’s famous statement in On Liberty (1859): “That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

I support the right of people to end their own lives by accessing humane means of doing so. I also believe people should not be prevented from pursuing leisure or adventure activities which are dangerous to them alone, as much as we might hope that they would decide to not do these things. Obvious examples here are lone ocean sailing, mountain climbing, base-jumping and other dangerous sports. I’m happy to support some mandatory intrusions on individual liberty where there are only risks to the individual, but not to others. Examples here are compulsory seatbelts for vehicle occupants, helmets for motorcyclists and cyclists, and lifejackets for those in boats. These involve truly trivial impositions on freedom where the risk reduction benefits massively outweigh the deprivation of freedom disbenefits. The outrageous erosion of the freedom to not use a seat belt which might prevent a person spending the rest of their life with severe disability is such an example.

Many tobacco control policies and publicity campaigns are explicitly intended to make the choice to smoke one that is ushered through a daily obstacle course of exposures, considerations and nudges known to reduce the likelihood that someone will want to take up smoking and continue to do it.

Seriously dissuasive taxes; minimum floor prices; ghoulish, arresting graphic health warnings; banishing smoking away from exposure to others; banning all tobacco advertising (including paid product placement in movies and with social media influencers); banning misleading descriptors like “light and mild”; preventing manufacturers spicing up cigarettes with flavours that disguise what would otherwise be a far less palatable smoking experience; restricting retail purchasing to an ever-decreasing number of retail outlets and licensing smokers in the way that all users of prescribed drugs require a temporary licence to access pharmaceuticals are all policies I’ve been happy to advocate. Most of these are policies which have been endorsed by the 181 nations which are parties to the WHO’s FCTC which came into force on 27 February 2005.

But as most of these policies play out across the world and smoking rates are at their lowest ever recorded in nations with advanced tobacco control policies, there is still an immense number of people who continue to buy tobacco products – 1.1 billion at the most recent estimate – thanks mostly to world population growth (GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators 2021).

So should we just continue to erode this number using the menu of policies and campaigns which have driven smoking prevalence down to record levels in nations with comprehensive tobacco control? Or is it time that tobacco control moved to the next level and treated tobacco the way that other unambiguously deadly commodities have been treated?

There is a wide-open door being held ajar here by J.S. Mill’s dictum quoted earlier. When he wrote about power being exercised over “any member of a civilised community” to prevent harm to others, he was writing about individuals. But had Mill known that smoking could harm others chronically exposed to tobacco smoke, he may well have used smoking as an example, as ethicist Robert E. Goodin laid out in his classic 1989 analysis The ethics of smoking, published 130 years later, of the ethics of preventing smoking when others were exposed (Goodin 1989).

And had there been transnational tobacco corporations in the mid-19th century when Mill was writing, doing all they could to promote smoking and thwarting effective tobacco control and thereby harming millions by their daily actions, he may well have also readily agreed that industry’s liberty should be very much on the table for radical constraint.

While there can be proper concerns about impositions on freedom of individuals, a whole different set of considerations opens up when proposed constraints on corporations’ actions which harm individuals are considered.

Ever since the bad news began rolling in from the early 1950s about the inconvenient problem of the very nasty harm that smoking causes, the industry has pursued a public agenda of announcing successive generations of allegedly reduced harm products. Unfortunately, every one of these crashed as false hopes (Chapman 2016). All were primarily designed to keep nicotine-dependent customers loyal to the companies’ evolving products and to dissuade people from quitting.

No industry likes seeing its longest and most loyal customers dying early. They’d far prefer that they lived to consume and be contributing cash cows for as many years as possible. There is also no industry more publicly loathed and mistrusted than the tobacco industry (Freeman, Greenhalgh et al. 2020). Against this, the harm-reduction agenda represents a trifecta of hope for Big Tobacco: it’s a kind of perpetual holy grail, never reached but always sought, with the promises of seeing smokers living and consuming longer. It’s also a way of enticing new generations of users into the market who each time swallow the hype about radically reduced-risk products. And it carries hope of eroding the industry’s ongoing corporate pariah status (Christofides, Chapman et al. 1999), with its attendant risks of attracting sub-optimal staff indifferent to working in a killer industry (Chapman 2020). Harm reduction is a virtue-signalling cornucopia that keeps on giving.

Enter NVPs

NVPs are the latest harm-reduction debutantes. The size of the popularity wave they are riding in several nations puts these products in the league of two previous, long disgraced illusory heavyweight champions of harm reduction: filter tips and so-call light and mild cigarettes. Filters are almost universally still used today in cigarettes, but with eight million deaths a year still occurring, it’s a bit like saying that arsenic is less harmful than cyanide, thanks to filters. Because of compensatory smoking, lights and milds were declared misleading and deceptive descriptors by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in 2005 and outlawed (Anon 2005). Tobacco companies in the USA were obliged to run court-ordered corrective advertising, including messages about the lights and milds scam (Kodjak 2017).

The rise of NVPs has been accompanied by a chorus of Big Tobacco CEOs proclaiming that they mark the beginning of the end of smoking. “Look what we are doing,” they gush. “We are transforming ourselves into companies that are saving lives! We are investing billions into research, development, production and marketing of these new products.”

But on the floors that house those in the executive who pull the strings for the entire companies, they know exactly how the company bread is buttered and what the future vision looks like. And for all the sloganeering about the end of smoking, that future has, as always, cigarettes right at the very front of the business model.

BAT’s 2018 half-yearly report could not have been more emphatic on this from its opening paragraph, “Our strategy is to continue to grow our combustible business while investing in the exciting potentially reduced risk categories of HTP, vapour and oral. As the Group expands its portfolio in these categories, we will continue to drive sustainable growth” [my emphases] (British American Tobacco 2018).

A senior Philip Morris International spokesperson, Corey Henry, told the New York Times in August 2018, “As we transform our business toward a smoke-free future, we remain focused on maintaining our leadership of the combustible tobacco category outside China and the US” (Kaplan 2018).

In 2017 Altria, previously known as Philip Morris Companies, Inc., noted that Philip Morris USA candidly spoke of “making cigarettes our core product” (see https://twitter.com/SimonChapman6/status/908283373994500096).

Reduced-risk products instead of or as well as cigarettes?

In 2019, six researchers who declared that they were happy to state they worked with the tobacco industry, wrote in Addiction, “If the tobacco industry seeks to make money by making reduced-risk products instead of more risky products, we fail to see this as a menace to public health” [my emphasis] (Hughes, Fagerström et al. 2019).

Yes, I’m afraid they did fail to see the menace. Put simply, there is no evidence – apart from an incontinent river of public “trust us” declarations – of any tobacco company taking its foot off the twin business-as-usual accelerators of massively funded marketing of combustible tobacco products (chiefly cigarettes), and continuing efforts to discredit and thwart policies known to have an impact on preventing uptake and promoting cessation.

In recent years companies like BAT and Philip Morris have been relentless in seeking to dilute, delay and defeat any policy posing any threat to their tobacco sales. This is not the behaviour of an industry earnestly trying to get all its smokers to quit. Witness their massive efforts to stop Australia’s historic plain-packaging legislation (Chapman and Freeman 2014). Witness their years’ long efforts to stop Uruguay’s graphic health warnings (Anon 2021). As recently as December 2016, BAT’s lawyers wrote an appalling letter (see Herbert Smith Freehills 2016) to the Hong Kong administration trying to stop graphic health warnings going ahead. This was from a company that published in its 2016 financial results statement a call to “champion informed consumer choice” (Durante 2016).

There is a very long history of the tobacco industry, hand on heart, promising that it really wants to make cigarettes a thing of the past. These were all harm-reduction adventures of mass distraction, designed to reassure smokers that they could continue to consume the industry’s tobacco products.

Phasing out cigarettes?

In a 2020 open-access paper, editors at Tobacco Control Elizabeth Smith and Ruth Malone articulated the most cogent case yet for tobacco control to take the gloves off and introduce radical policies which will end the sale of combustible tobacco (Smith and Malone 2020). Their argument runs like this.

In 1985, the United Nations unanimously adopted guidelines for consumer protection including that “Governments should adopt or encourage the adoption of appropriate measures … to ensure that products are safe for either intended or normally foreseeable use” (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development 1985). So when it comes to tobacco, there is arguably no other product which comes anywhere close to being the prime candidate for governments to apply such scrutiny. Smith and Malone wrote:

All advanced nations require cars to undergo crash tests before they are sold, food manufacturers and processors are held to hygienic standards, and drugs undergo clinical trials to establish safety and effectiveness. Legal consumer products found to be hazardous are regularly pulled from the market, such as toys presenting choking hazards for children; batches of contaminated processed food or individual components of complex goods (e.g., batteries, airbags) that work improperly. Manufacturers or retailers sometimes recall goods that appear to malfunction, even without reported injuries. For the most part, consumers assume that products offered for sale are reasonably safe.

Tobacco fails any test of consumer safety but bizarrely continues to enjoy exceptionalist status being shielded from the powers of consumer protection law. They continue:

From the consumer protection standpoint, most people do not believe that people “need”, “deserve” or “have the right to” purchase cars that are unsafe to drive, medications that poison them or food that spreads disease … The “right to smoke” framing obscures the generally accepted ethical obligation of reputable companies to sell only products that do not cause great harm when used as intended.

So laws ensuring product safety should also apply to all tobacco products. Not just to their marketing, advertising, packaging and where they cannot be smoked in the case of combustible forms, but to the products themselves. De facto exemption of tobacco products from consumer safety laws would be like regulating civilian firearm access but deciding that dynamite and explosives were fine to be on sale to anyone who wanted to buy them.

Smith and Malone write about the “phasing out” of cigarette sales, arguing that instances of this are already happening is a very small number of US towns and cities with low smoking prevalence, driven by local governments. They suggest that these bans will in time spread to neighbouring towns or municipalities and note that similar gradual spread occurred with the rollout of smoke-free ordinances. They readily admit this will be “an arduous and lengthy process”, as indeed was the smoke-free-areas chapter in tobacco control history. Smoking was first banned on trains and buses in my state of New South Wales in 1976. It took until 1 December 2006 before smoking was finally banned in pubs and bars, the so-called last bastions of freedom to ignore the occupational health and safety of bar workers.

Smith and Malone stress the importance of public health advocates continually trying to change the dominant narrative away from cigarettes being an ordinary, legal consumer product to characterise them as being an “inherently defective, unsafe product that falls into the same category as contaminated food, asbestos and lead paint. These are products that states find too hazardous to be made available to the public, and regardless of cost … the government removes them from the marketplace.” They suggest a parallel case would be comparison with the phase-out of leaded petrol: “As with tobacco, manufacturers knew for decades that leaded gasoline was hazardous and concealed that knowledge. Still, the eventual phase-out of leaded gasoline in the USA took a decade.”

The comparison though is far from perfect. Leaded petrol had a ready substitute in unleaded alternatives. Similarly, calls to phase out fossil fuels always point to obvious renewable power alternatives. Incandescent bulbs rapidly disappeared with the advent of LED lighting. Records, cassettes and CDs were overtaken by MP3s and streaming. And film cameras by digital cameras and smart phones. All of these examples saw tentative consumer resistance often turn into tsunamis of uptake of the improved alternatives.

If we were confident from the hype that NVPs could indeed deliver all they promise, it would be obvious where a phase-out of tobacco could lead. Tobacco retailers would continue to profit from nicotine dependency in barely the blink of an eye, governments would see their tobacco tax receipts continue, switched to NVPs. But as we saw in Chapter 6, it is very far from clear that NVPs will indeed drive smoking down rather than sustain it through dual use and increasing relapse.

Governments derive significant revenue from tobacco tax and goods and services taxes (GST) that are added to nearly every commodity or service transaction. Many people have taken this to mean that governments have a clear interest in doing nothing that would ever kill or badly wound the goose laying these golden eggs. But this reasoning is deeply flawed. Here’s why: non-smokers do not engage in daily rituals of calculating how much tax revenue their selfish acts of not smoking deprive the government in tobacco tax and then squirrel this money away in a box under their beds forever or put it through a shredder.

Instead, they use their money to purchase other goods and services. Each of these expenditures is GST inclusive, generates employment and has multiplier effects in the economy. So, if there was no smoking or vaping, there would not be a neatly packaged and easily identified bolus of tobacco tax that went directly into Treasury surrounded by dazzling neon signs calling on everyone to be grateful to Big Tobacco for their marvellous contributions to economic well-being. Instead, this money would be dissipated into many different expenditure routes, each of which – just as occurs with tobacco expenditure – generates tax, employment and economic well-being.

Moreover, as Warner and Fulton showed in a case study of what would have resulted had the state of Michigan, USA, somehow had zero tobacco consumption between 1992 and 2005, 5,600 extra jobs would have resulted (Warner and Fulton 1994). Big Tobacco has been hugely successful in spinning its story to people with low literacy in economic matters, but in fact in many nations, tobacco expenditure compares poorly in social benefit terms to expenditure on other goods and services.

It is very easy to throw the “phasing out” expression around as a sensible-sounding aspirational goal. But when we look for what would be involved in any step-by-step progression of a program of phasing out, there are scant details.

My reading of where the “phasing-out” argument rests at the moment is as follows:

- It is unarguable that the ludicrous exceptionalist status of tobacco as a deadly product which has so far escaped serious regulation or banning as an unsafe product needs to be raised as a fundamental starting point in every global and national high-level discussion about the future of tobacco control.

- For as long as tobacco continues to be sold as an unregulated product through virtually any retailing context, this will powerfully condition the commonly expressed view that “tobacco cannot be that harmful, because otherwise governments would ban it”. Tobacco needs to be legally classified as a controlled, restricted product in all its forms.

- Large majorities of the population, including smokers, support measures designed to make their decision to smoke a more difficult choice. This gives strong support to “next steps” rhetoric from governments about how they might best accelerate the fall in smoking. They will be cheered on by a large proportion of the community (Gartner, Wright et al. 2021).

- Consistent and commensurate with a formally declared status as a restricted product, tobacco access and retailing could then change. Much more restrictive regulation of tobacco retailing is an obvious candidate for a next big step. The key elements of retailing restricted products should be: licensing all retailers; introducing permanent loss of license for anyone selling to minors or breach of other licensed retailer regulations; and requiring that tobacco be sold in dedicated tobacco retail settings away from other grocery or mixed-business-style goods and only to those permitted to buy tobacco (see number 5); and requiring all retailers have electronic records to reconcile all sales with their registered inventory of tobacco stock.

- All tobacco purchasing should be conducted through a date-of-birth-linked QR code, with capabilities to data-link purchasers with tobacco stock sold. This would ensure that all customers were over the legal age to purchase tobacco and that retailers only sold stock that had been logged onto their official stock inventories, much in the same way that pharmacists must always have fully reconcilable records of all restricted stock.

- The evidence that NVPs are all but benign and clearly superior to other ways of quitting – including unassisted quitting – is poor and in the case of assessing any potential long-term harm, very premature. Accordingly, it would be reckless to allow NVPs to be sold in an any less restricted way than any therapeutic substance entering a market is now sold: via the authority of a doctor’s prescription, as described earlier about the current Australian arrangements. Some drugs (e.g. NRT) were rescheduled as OTC access after years of monitoring for safety issues when they were prescribed. The same potential may exist for NVPs, although because there are literally many thousands of NVP apparatuses and NVP compounds, this will be much more complex than it was for NRT with its standardised formulations.

- The overarching objective of NVP regulation should be to make approved products available under a prescription regimen only for adult smokers assessed as genuinely wanting to quit smoking. This will pose many challenges as NVP marketers will game the rules by incentivising doctors to provide these products to as wide a range of applicants as possible, using perfunctory assessments. Surveillance of doctors’ over-prescribing here will be as important as it has been for other controlled drugs.

The endgame in chess is often the longest and slowest phase of the game. The word does not at all connote a rushed period of play just before a game ends. Much of the above will take time in the same way that all policy advances in tobacco control have taken (with rare exceptions). Where tobacco control has been taken seriously, there are now nations with national smoking prevalence below 10% (Iceland 7.3% daily and Norway 9% daily) (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021), and subpopulations with smoking rates sometimes well below that level. In the USA only 8% of 18–24-year-olds smoke, 7.2% of Asians, 8.8% of Hispanics, 6.9% with an undergraduate education and just 4% with a graduate degree (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021). In Australia 7.9% of people with a bachelors degree or higher smoke, 7.7% of those who speak a language other than English at home, and 8.2% of those in the highest socioeconomic quintile (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020h). Only 8.8% of women and 8.3% of 18–24-year-olds smoke daily (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021). In the UK, 7.3% of those with a degree smoke and 9.3% in managerial occupations (Office for National Statistics 2020a).

Tobacco control is widely regarded as the poster-child of chronic disease control in nations that have implemented comprehensive regulatory “upstream” policies which reach every smoker and potential smoker. No other non-communicable disease area – e.g. obesity, Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, sedentary lifestyles – can point to the magnitude of sustained improvements that tobacco control has caused over decades.

Throughout this book I have emphasised that far too much organised tobacco control is focused on activity that, in its net contribution to reducing smoking, is a story of the tail trying to wag the dog. The over-focus on tail wagging techniques in tobacco control for the past 30 years has caused mass distraction from what is quietly going on with the dog itself. Here, there is much to both celebrate and amplify with policies and motivational campaigns that have proven track records and are detested by the tobacco industry because of that impact. Those two tests are all we really need to know in how we continue to make smoking history.

1 Reproduced from Tobacco Control, S Chapman, B Freeman, 18, 496–501, 2009 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.