8

Strategies for reducing smoking across populations

Psychologist Stanton Peele commenced his 1989 iconoclastic book Diseasing of America: how we allowed recovery zealots and the treatment industry to convince us we are out of control (Peele 1989) by summarising what he found fundamentally misleading about “disease theory” in addiction. His book contested the disease theory’s contentions that:

- An addiction exists independently of the rest of a person’s life and drives all choices about the substance(s) to which a person is addicted.

- Addiction is progressive and irreversible, so that the addiction inevitably worsens unless the person seeks medical treatment or joins a support group.

- The addict cannot recognise the disease in the absence of education by addiction experts.

- Addiction means the person is incapable of controlling his or her addictive behaviour without assistance.

He wrote that his book was an attempt to “oppose this nonsense by understanding its sources and contradicting disease ideology”. Peele’s criticisms focused entirely on the addiction treatment industry and the ways in which it disabled personal agency in those wanting to end their dependencies. Throughout this book, I’ve set out evidence for how this process arose and consolidated for the case of smoking.

Peele’s four criticisms provide a bedrock for understanding why it is that the excessive medicalisation and commodification of smoking cessation emerged and has been sustained. But it is important to emphasise that nothing in this perspective requires any disagreement that nicotine is a highly addictive drug which ticks all the definitional boxes for a dependence-producing drug. Tobacco and vaping industry chemists know a great deal about how to fine-tune the grip of nicotine to maximise the probability of experimental users developing quickly into daily users and holding them there.

That said, disease theory has infected popular understanding of addiction – including smoking – with often ridiculous hard determinist narratives: if you are a smoker, you’ll find it very hard to quit, you’ll fail perhaps many times to quit, and you’d be very foolish to think that you can quit without professional help or being medicated in your efforts.

Our 2010 PLOS Medicine paper on the neglect of unassisted quitting research and its dissemination to smokers concluded with a plea for restoring balance in communications with smokers about smoking cessation. We wrote, “public sector communicators should be encouraged to redress the overwhelming dominance of assisted cessation in public awareness, so that some balance can be restored in smokers’ minds regarding the contribution that assisted and unassisted smoking cessation approaches can make to helping them quit” (Chapman and MacKenzie 2010).

In our paper we also provided a summary of messages that should be given to smokers, but rarely are. These include:

- A serious attempt at stopping need not involve using NRT or other drugs, or getting professional support (note: we did not say that it must not involve pharmacotherapy).

- Assistance should be considered a second-line choice for those who really need help. It should not be the first-line as it is now throughout the professionalised guidance literature on quitting.

- NRT, other prescribed pharmaceuticals and professional counselling or support have helped many smokers, but are certainly not necessary for quitting.

- Along with motivational “why” messages designed to stimulate cessation attempts, smokers should be repeatedly told that going cold turkey or reducing then quitting are the methods that have been and remain most commonly used by successful ex-smokers.

- Many quit efforts are not serious attempts but little more than flaccid gestures with little conviction.

- So-called failures in quit attempts are a normal part of the natural history of cessation. For millions, they have been rehearsals for eventual success. Just because you did not succeed in an unassisted attempt doesn’t mean that a later attempt will also not succeed.

- More smokers find it unexpectedly easy or moderately difficult than find it very difficult to quit.

- Many successful ex-smokers do not plan their quitting in advance and those who don’t plan have greater success, probably because they have greater determination and are not distracted by largely evidence-free professional folklore about taking a staged approach to quitting.

- In a growing number of countries today, there are far more ex-smokers than smokers.

The core message I have tried to emphasise throughout this book has been that the overwhelming dominance of assisted cessation in the way that quitting has been framed over the past three decades has done a huge disservice to public understanding of how most smokers quit. Around the world, many hundreds of millions of smokers have stopped without professional or pharmacological help. In Chapter 5 we saw there is no strong evidence that while all this has been happening, today’s smokers have become “hardened”. If anything, the very opposite is the case.

The persistence of unassisted cessation as the most common way that most smokers have succeeded in quitting is an unequivocally positive message which, far from being suppressed or ignored, should be openly embraced by primary health care workers and public health authorities as the front-line “how to” message in all clinical encounters and public communication about cessation. It should be shouted from the rooftops of every government health department, non-government health organisation and emphasised opportunistically in media interviews about the importance of quitting.

Because of their trusted roles with patients, clinicians can play vital roles in motivating quit attempts and assisting smokers to quit. Drugs can certainly be a part of this. But what I lament is the way that unassisted cessation is mostly ignored and frequently denigrated by the professional smoking-cessation community, many of whom also have occupationally vested interests in maintaining the fiction that unassisted cessation is not a sensible or “evidence-based” way to quit. I support stepwise approaches to triaging assistance to smokers, but note that many smokers can quit unassisted and that the primary message to smokers ought not to overstate the difficulty of quitting by constantly characterising cessation as something that has virtually no chance of success when the experience of most ex-smokers abundantly shows otherwise.

In this chapter, I want to focus on what has driven so many to quit smoking since the 1950s. I will explore what lessons this holds for those working today in tobacco control, public health and government and what they should focus on more, rather than diverting energy to distracting strategies that can never deliver the large numbers necessary for driving smoking down across whole populations. Or worse, naïvely enabling strategies to flourish which risk slowing or reversing the trend away from smoking.

The melding of primary and secondary prevention

In public health, a basic approach to conceptualising preventive policies and interventions is the primary, secondary and tertiary distinction. Primary prevention involves actions taken to prevent a given health problem from ever occurring; secondary prevention is where steps are taken to identify a nascent problem early so that it might be treated early where evidence shows that early direction and treatment can improve outcomes; and tertiary prevention is activity designed to helping people better manage long-term health problems (e.g. chronic diseases, permanent impairments) to improve as much as possible their functioning, quality of life and life expectancy.

Smoking declines in populations in two ways: growth in the proportion of people who have never smoked, and increases in the proportion of smokers who quit permanently. The first is achieved by primary prevention and the second by the interplay of many factors which often work together to motivate smokers to quit (secondary prevention).

When it comes to cessation in nations which have embraced comprehensive approaches to tobacco control across several decades, there’s an elephant in the room unavoidable to anyone looking at the very top line of data on progress. In such nations, ex-smokers today significantly outnumber those who smoke. In the USA since 2002, there have been more former smokers in the USA than current smokers (United States Surgeon General 2020).

Australia is another perfect example, with there being more ex-smokers than smokers in all eight national Australian Institute of Health and Welfare triennial surveys conducted between 1998 and 2019. In 1998, 25.4% of Australians aged 14 and over smoked (daily or less than daily and any form of combusted tobacco) and 25.9% were ex-smokers. By 2019 this had changed to 14.9% (2.9 million) smoking, 22.8% (4.8 million) being ex-smokers, with 13.2 million having never smoked (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020h).

This 12% fall in the proportion who were ex-smokers between these 21 years is a product of smokers quitting or dying, but most importantly also because of the continual growth in the proportion of Australians who have never smoked (49.2% in 1998 and climbing to 63.1% in 2019) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020g). By definition, an ex-smoker must have once smoked. So when the size of the pool of never smokers keeps expanding, there are far fewer smokers available to contribute to the ex-smoking pool. By far the biggest contribution to increasing the proportion of people who do not smoke today (never smokers plus ex-smokers) comes from the huge primary prevention success story in reducing smoking uptake in young people. Around 60% of all smokers in Australia commenced regular smoking before the age of 18.

So in tobacco control, primary prevention has made the biggest impact by – across the years – greatly increasing the proportion of the population who have never smoked. Activities designed to motivate and help smokers to quit are secondary prevention, and around the world these too have seen cumulatively many hundreds of millions quit, particularly since the 1960s. However, it is vital to understand that many policies and initiatives often operate in both modalities. As we will see later in this chapter, consonant with what occurs with nearly all goods and services, rises in retail price such as via tobacco tax can motivate smokers to both quit or reduce daily cigarette consumption. But they can also be a factor which, along with others, deter uptake in young people on zero or very low incomes who are highly price sensitive.

Similarly, quit-smoking campaigns designed to motivate quitting in smokers are also seen by vast numbers of teenagers who don’t smoke. Many of them experience the same deterrent effects that smokers experience. Instead of thinking as smokers do, “I think I’ll quit,” they think, “Wow, I really don’t want to risk those illnesses happening to me. I won’t start” (White, Tan et al. 2003).

Throughout this book, we have seen that for as long as smokers have been quitting, a substantial majority of ex-smokers made their final, successful and long-term sustained quit smoking attempt unaided. They have not swallowed, worn, chewed or inhaled any aid or received any sustained assistance from any professional therapist, counsellor or advisor. Hundreds of millions of people around the world who once smoked discovered they had the agency to end what for many was a strong addiction without recourse to assistance. And as we saw in Chapter 5, the proposition that all of these people were simply the low-hanging fruit of light smokers who were able to quit more easily – an assumption of the hardening hypothesis – is simply not borne out by the evidence.

I’ve laid out evidence for this phenomenon and for the efforts of commercial interests in the pharmaceutical and NVP industries to discredit it and distract smokers from industry income-subverting thoughts that they might quit without using these industries’ products. Sadly, they have often been abetted in their efforts by leaders in public health and medicine, many of whom have been supported by grants and conference travel from those industries. Together, for the reasons I’ve set out, these interest groups have been major, industrial-strength purveyors of methods of quit-smoking mass distraction.

Big Tobacco, now also heavily invested in NVPs, sees an ideal nicotine delivery device as one which either holds smokers in smoking through dual use, or grips vapers in the other frantic nicotine self-dosing rituals we’ve all seen and which I described in Chapter 6. An ideal smoking-cessation product for a pharmaceutical or NVP company is not one which succeeds quickly and therefore renders continual use of such products no longer necessary. It is rather a product that doesn’t work very well at all but which can be cloaked in ever-changing marketing appeals that smokers need to use it longer, try it again, use it in combination with other drugs, or use it forever. NRT in particular fits that description like a glove.

The new narrative: don’t quit … switch!

Even well before the early 1960s, the dominant narrative about smoking has been that it was something that most people who did it regretted and struggled to end. But today this narrative is being undermined by a shift from one about quitting smoking to one about switching to NVPs, to the great delight of those in the industries whose very existence rests on the widespread continuation of nicotine dependency. Today, it is common to hear interviews with people introduced as authorities in tobacco control who give a perfunctory nod to quitting before gushing forth with snakeoil-like carnival barker style claims that make vaping sound like a wonder drug and nicotine as an almost vitamin-like substance.

Some of the very worst are down-in-the-last-shower, inexperienced people who were never engaged in any substantive way with the decades of successful tobacco control that saw smoking rates continually fall; the tobacco industry treated by governments, the media and the public as the corporate pariahs they have always been (Christofides, Chapman et al. 1999); and every advocacy campaign that was ever fought to curtail their dissembling and marketing succeed with the passage of laws the industry loathed and fought. Some of these “researchers” are supported by lavish grants originating from the tobacco industry and feted with international travel support laundered through “independent” third-party slush funds.

In sidelining quitting to put the spotlight on switching, two huge and inconvenient truths have become marginalised under the weight of anecdotal evidence from cult-like vaping advocates. First, as we saw in Chapter 6, the accumulating evidence is that a majority of those who take up vaping never give up smoking but instead engage in dual use, often for many months or years. And these dual users do not reduce their exposure toxicants: they in fact get more than smokers who do not vape – see Chapter 6 (Miller, Smith et al. 2020). Second, relapse to smoking rates in those who vape, including those who vape regularly, are higher than those smokers who try to quit without vaping (McMillen, Klein et al. 2019, Miller, Smith et al. 2020, Gravely, Cummings et al. 2021). Knowing this, the interests of the tobacco industry in promoting vaping are obvious (Sollenberger and Bredderman 2021).

And this is before we even touch on the alarming rise in regular nicotine use via NVPs in young people, who were on track in several nations to keep breaking all records in having the lowest smoking rates (and lowest of any nicotine use) since smoking began being monitored in national surveys.

But while all this has been happening, unassisted smoking has continued each year to deliver more net long-term ex-smokers than all other quitting methods combined. So what does the evidence show about factors which have fomented, stimulated, triggered and sustained this massive, ongoing but little appreciated and understudied phenomenon?

Attribution problems in smoking cessation research

When former or current smokers are questioned about their smoking, they are generally asked about their smoking history, their smoking frequency (how often and how many cigarettes they smoke), the number of times and the duration of their past attempts to quit, and whether they used any aids in their quit attempts and how long they persisted with these. Some studies also explore factors that quitters believe were responsible for their decision to try to quit.

As we saw in Chapters 3 and 7, for many smokers, having a method to quit (a how), is far less front-of-mind than having a reason to quit (the why of quitting). I’ve also emphasised that the obsession among many in tobacco control with cessation rates without giving equal or more weight to any cessation method’s population reach has muzzled efforts to encourage unassisted cessation. The key to unleashing more quitting throughout a nation’s smokers, then, may be to focus less on how to quit, and far more on motivating more smokers with a why to try to quit and to do this more frequently, regardless of whether these quit attempts are assisted or unassisted.

In this I’m reminded of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who said that those who have a “why” to live for can endure almost any “how”. So adapting Nietzsche, smokers who have deeply internalised powerful motivations for quitting will usually find a way to quit.

The vital importance of promoting quit attempts

A seminal paper from 2012 by Shu-Hong Zhu and colleagues (Zhu, Lee et al. 2012) is apposite here. The authors looked at US National Health Interview Survey population data from 1991 to 2010, to examine the key equation of population cessation impact = effectiveness × reach. The authors observed:

it might seem obvious that smokers must first try to quit before they can succeed, making the importance of quit attempts self-evident. However, the field of cessation has focused so much on developing interventions to improve smokers’ odds of success when they attempt to quit that it has largely neglected to investigate how to get more smokers to try to quit and to try more frequently.

In making this case, Zhu et al. noted that in both the USA and the UK, significant rises in using smoking cessation medications had not translated to higher quit rates. In the USA in 2000, 22.1% of smokers making quit attempts used medications and this increased to 31.2% by 2010. But they emphasised that there was “no corresponding incremental increase in the 3-month quit rate” and that changes in the quit rate across that time “correspond[ed] more to changes in the quit attempt rate than to changes in the use of cessation medications”.

When the UK turbo-charged the promotion of medications commencing in 1999, medication use changed dramatically. From 1999 to 2001, the proportion of quit attempts that involved cessation medications leapt from 28% to 61% (West, DiMarino et al. 2005). A corresponding change in the population cessation rate was projected but not found for those years (Kotz, Fidler et al. 2011).

So what do we know about how best to motivate more smokers to make more quit attempts?

What “works” in tobacco control?

Across some 45 years of working in tobacco control, there have been countless times when I’ve been asked, “So, has [insert here] policy or [insert here] campaign worked?” Most asking this do not then go on to explain what they mean by “worked”, but many hundreds of such conversations have taught me that they are most often wanting to know “What’s the evidence that a policy or campaign causes many extra smokers to quit for good?”

The question has its roots in clinical interventions where we all have had many experiences of the desired changes after using a drug. We all know what happens when we take an analgesic for pain, get an injection before having a tooth pulled or root canal therapy, apply a fungicide on athlete’s foot, or use contraceptives and avoid pregnancy. It quickly becomes very obvious when these things work!

So it’s understandable that people should ask the same about a piece of tobacco control legislation or a multimillion-dollar TV campaign about smoking when “doses” of these are given to whole communities. Do these things make a difference across whole populations? For example, in the wake of Philip Morris International being ordered to pay the Australian government $50 million in legal costs over the company’s failed attempt to thwart plain packaging (Donovan 2017), I was asked the question, “Has plain packaging worked?” many times. Those interested in this question can read a vast amount of research on this in Packaging as promotion: evidence for and effects of plain packaging (Greenhalgh and Scollo 2019).

The cauldron of proximal and distal influences

While many asking these questions demand a simple yes or no answer, the forensics of understanding how it is that people both try and succeed in quitting are far more complicated than the clinical assessment of a drug. In 1999, the late Tony McMichael, professor of epidemiology at the Australian National University, published a classic paper in the American Journal of Epidemiology titled “Prisoners of the proximate: Loosening the constraints on epidemiology in an age of change”. He wrote about the need to understand the determinants of population health in terms that extended beyond proximate single influences and drew as well on distal influences that can often simmer and percolate for many years before manifesting in cultural and individual change (McMichael 1999).

While a smoker might nominate a particular policy, conversation with a doctor or anti-smoking campaign as being the reason they quit, much of what went on before provides the broad shoulders of concern that condition and carry the final, typically proximal attribution. There are synergies between all these factors and the demand to separate them all is like the demand to completely unscramble an omelette: we know that when all the ingredients are cooked together, the result can be very satisfying. But all cooks know that the final result is greater than the simple sum of each of the ingredients.

In science though, the appetite in the dining room is for all cooks to give reductionist explanations, where the goal is to pinpoint the exact contribution of every variable to an outcome (Shuttleworth 2008).

When they finally succeed, ex-smokers will often nominate a reason “why” they quit as they share their story with others. People will sometimes nominate a recent “straw that broke the camel’s back” as the precipitating reason for the final decision to quit and their resolve to see it through. This can be a symptom they have experienced; an incident like the smoking-caused death of a friend or family member; a particularly poignant campaign advertisement that they couldn’t get out of their head; the heartfelt pleading from a child or partner that they quit smoking; the sudden realisation that very few of their colleagues or friends smoke; an epiphany about being yoked by nicotine addiction when having to leave a restaurant to smoke out in a cold street with others with similar nicotine dependency; or being faced with a psychological barrier like cigarette prices going up to $35 a pack. Sometimes smokers are keen to point to several of these things clustering around the incident or conversation which they feel finally made them do it.

These proximal triggers can certainly stimulate quit attempts: factors easily identified, nominated by smokers aware of their influence, and sometimes easy to quantify with proxy measures like immediate boosts in calls to quitlines after known scheduling of televised quit messages (Miller, Wakefield et al. 2003).

But there are also vital distal or background factors at play, slowly and subconsciously eating away the foundations of smokers’ feelings of disease invincibility or apathy and denormalising pro-smoking social environments. Smokers get fewer positive reminders about smoking and experience a growing awareness that smoking is not something that the great majority of people do anymore.

Examples of these distal factors are advertising bans, graphic warnings on packs, plain packaging, smoke-free public spaces, tobacco taxation, and the constant flow of news and campaign information about the harm from smoking. Most countries with advanced tobacco control have implemented most of these policies. Few if any smokers will say they quit smoking because tobacco advertising was banned. Thirty years ago when we fought for advertising bans, tobacco companies used to jubilantly hold such survey findings aloft, pleading with governments to keep their hands off advertising. “See, this survey shows that no one names tobacco advertising as either a reason they took up smoking or continue to do it.” But does this mean that both advertising and its banning have no impacts?

The obvious question so often able to be asked about such tobacco industry protests is why, if a policy really offers no threat to tobacco sales, does the industry even worry about its introduction? Why bother spending hundreds of millions around the world to stop advertising bans, graphic health warnings on packs, plain packaging or the spread of smoke-free policies if none of these things allegedly makes any difference?

Advertising can have rapid effects, as any manufacturer or retailer can attest. But the impact of advertising bans also works in slow-burn fashion. Instead of the best efforts of advertising agencies to imbue every opportunity with memorable imagery and persuasions about the joys of smoking, in 1996 the final curtain came down forever in Australia on that long-running effort when the last outlet for tobacco sporting sponsorship ended. A child born in 1996 is 26 today in 2022. They have lived all their life never having been exposed to any form of tobacco advertising, promotion or sponsorship that can be controlled by Australian legislation.

While some smokers experienced an increased urgency to quit by the purposefully unappealing plain packs with their ghoulish (but deadly accurate) large graphic health warnings (Wakefield, Hayes et al. 2013), the primary goal for plain packs was to have whole generations grow up never having been beguiled by the designer edginess of tobacco pack branding and noting the exceptionalism of plain packaging among all other consumer goods. Tobacco is the only product where legislation mandates plain packaging (32 nations have either implemented, legislated it or announced that they will) (Canadian Cancer Society and International Status Report 2021) and out-of-sight retail display bans (Harper 2006). These thoughts (“Hmm, why does all this apply only to tobacco?”) might help shake the fragile foundations of the belief that tobacco is just another of the many risks in life.

Importantly, all these factors do not act in isolation, but like a constant and unstoppable termite colony, they work often unnoticed in synergy to erode the appeal of smoking.

A day in the life of Australian smoker Mr Rex Lungs, 2022

In my 1992 BMJ paper “Unravelling gossamer with boxing gloves: problems in explaining the decline in smoking” (Chapman 1993), I described a day in the life of a smoker who had just quit. The smoker woke to radio news of yet more bad research news about smoking; lived with disapproving family members who had often urged him to quit because they had been educated about the risks; winced every time at the price he had to pay for a pack; was acutely aware of all the places he couldn’t smoke and why those laws had been introduced; was self-conscious about the stench of stale tobacco that he carried about; and couldn’t shake some of the powerful anti-smoking advertising that intruded on his TV viewing.

A smoker might well nominate just one of these influences as top-of-mind when a researcher calls, but all play a part in a comprehensive approach to reducing the world’s leading cause of death, if we exclude poverty. A huge amount has changed in the day-to-day life of smokers in countries like Australia in the 38 years since that paper was published. So below, I have updated a day in the life of a smoker from 1993 to what it might be like in 2022. Let’s consider a recent day in the life of an Australian smoker, Rex.

As he wakes, Rex listens to a news item on his bedside radio concerning a new report which calculated that lung cancer is still the leading cause of cancer death in Australia and that 14% of smokers will develop lung cancer, including 7.7% of those who are currently smoking only 1–5 cigarettes/day and 26.4% of those who smoke >35 cigarettes a day (compared to 1.0% in never smokers) (Weber, Sarich et al. 2021). He had heard these grim reports so often since he started smoking as a teenager, but this one sticks in his mind because he’d taken some comfort in thinking that his mere 10 cigarettes a day would not be very risky. There goes another comforting rationalisation down the drain (Chapman, Wong et al. 1993, Oakes, Chapman et al. 2004).

The night before, he had been to a football match. It seemed like aeons ago that teams played for a trophy sponsored by a brand of cigarettes (the last tobacco-sponsored sporting event ended in Australia in April 1996). Now they even sold salads and sushi as well as the usual pies, hamburgers and greasy fries at sports stadia. And even though it was an outdoor stadium he’d been to, you weren’t allowed to smoke in the stands but had to go some distance behind one grandstand to a grim fenced-off “smoking area” and stand smoking with others.

As Rex sat at the breakfast table, one of his kids remarked that she could tell he’d already been out in the garden smoking because she could smell it on him. It seemed there had been dozens of these embarrassing jibes over the years. He wondered what people he worked with thought about this, but kept quiet about it. He knew his kids had lessons about smoking risks at school and felt bad that his smoking might make them worried about him dying early.

His wife, who, like the great majority of Australian women in their 40s didn’t smoke, actively disliked smoking. Ever since the late 1980s when Rex’s workplace had banned smoking, he had agreed to only smoke out in the garden and not in sight of their children. In making this request, it seemed to Rex that she was not really being overzealous. He had often heard scientists in the media talking about the risks of exposure to other people’s tobacco smoke and it seemed it was only the tobacco companies and shouty, swivel-eyed libertarian extremists who ever tried to dispute this. Smoking had become thoroughly denormalised (Chapman and Freeman 2008).

When he smoked outside, he always felt self-conscious and embarrassed that he was setting a bad example to his kids. He really didn’t want them to smoke and had recently had the thought that he had never heard any smoker ever express hope that their kids would take up smoking, at any age. He was definitely one of the 90% of smokers who regretted he’d ever started smoking (Fong, Hammond et al. 2004). He knew it was harming him. It was hideously expensive. It made him smell. He had long felt any loyalty toward smoking seeping away. Was there any product to which its loyal customers felt such loathing and ambivalence?

On the way to the train station to go to work he stopped to buy a new pack. He looked at the price board in the newsagent (there had been no cigarettes on retail display for over a decade since state government legislation forced all tobacco stock to be stored out of sight). His usual 25-stick-pack of premium cigarettes now costs $48.50 – just under $2 a cigarette – while the average 20-cigarette pack costs $35. Ten years ago, Rex used to smoke a full pack a day. At today’s prices that would set him back $17,700 over a year. So he had deliberately cut down to 10 cigarettes a day. But even that was still gouging $7,080 from his wallet each year. He’d seen a travel package offer showing where, for that money, he could take his whole family of four on a week’s luxury holiday to Bali, flights included, when travel resumed after COVID-19.

One of the sweeteners of pre-COVID-19 overseas travel had been that he could bring back two cartons of duty-free cigarettes, saving big money on what they would have cost him in Australia. But that too had all stopped, with duty-free being now limited to just one unopened pack.

Boarding his train, he pondered that here he was in the place where all these smoking bans started. Public transport had gone smoke-free in New South Wales way back in 1976, joined in 1987 by all domestic flights in Australia. These days there was not a single airline anywhere in the world which allowed smoking or vaping.

His daughter was soon to move interstate to attend a specialised course at a Melbourne university. She would need shared rental accommodation. As he browsed his phone for what was available, he noticed how many of the “share accommodation” listings specified that only non-smokers need apply. Indeed, as far back as 1992, 42% of share accommodation advertisements specified this requirement – a higher rate than any other quality sought by advertisers (Chapman 1992).

Smoking had been banned in all indoor workplaces in the years after all government departments banned smoking in offices in 1987. He’d even heard that lonely hearts advertisements overwhelmingly specified that people ruled out smokers when looking for a date (Chapman, Wakefield et al. 2004). Browsing his newspaper, he saw a large advertisement from a life-insurance company offering substantially reduced rates for non-smokers.

Walking from the train and arriving at work, Rex stubbed out what would be his last cigarette until lunchtime. You hadn’t been able to smoke in restaurants since 1990, and in bars and pubs since 2 July 2007. At lunchtime, Rex went with some colleagues to a nearby café for a coffee and sandwich. He noticed that even at the tables outside the café on the footpath, smoking was not allowed. At the ever-diminishing number of cafés where you could still smoke outside, he was often self-conscious about the death stares he’d get from nearby tables when he lit up. He then passed a street sign warning him that he could be fined for discarding his cigarette butt in the street – the non-biodegradability of butts made them a major pollution problem, especially in a city where stormwater ran into the picturesque harbour around which the city was built. Being very environmentally conscious, he felt quietly ashamed about his usual throw-away method of disposing of butts.

And if you were driving your own car, the police could pull you over and fine you if you were smoking in your car when you had children inside (Freeman et al. 2008). He’d been to an outdoor prog-rock concert recently, and despite it being outdoors, announcements were made from the stage about there being a sectioned-off smoking area, way back near the toilet areas.

Home that evening, Rex relaxed in front of the TV where on the news he heard a report linking smoking with yet another dreaded disease. “Was there anything that smoking didn’t cause?” he thought to himself, reflecting on all the news reports he had heard about the subject over the years. Being a sports fan, he zapped his TV between channels showing the national soccer and basketball competitions. And there it was again: anti-smoking sponsorship messages on the sidelines and even on the players’ clothing.

He’d given some thought to taking up vaping. But as an avid Twitter user, he’d noticed that so often when posts were made about vaping, they were made by those who seemed to have little interest in anything else. Their Twitter handles even described them as vapers. Their photographs often showed them vaping. Some even talked about their “vaping lifestyle” and went to vaping meet-ups. This reminded him of many stock-market obsessives, golfers, video gamers and dope smokers he tried to avoid. They were so one-dimensional. He liked wine and craft beers too. But he’d no sooner want to badge his whole identity on Twitter as a wine drinker as it would ever occur to him to proudly present himself there as a steak eater (he liked steak too). It seemed like taking up vaping ran big risks of being pulled into a kind of cult. And the massive plumes of vapour you’d see vapers billowing down the street looked very try-hard “please look at me”. So vaping held little appeal.

The next day, Rex decided that he would finally quit. Over the years, he’d made several gestures to do so that lasted a few days. And again, over the next 12 months, he made a few unsuccessful attempts, one inspired by a brief warning given to him by his doctor, and another being a few weeks where he used OTC nicotine gum after prompting from his pharmacist. Eighteen months after his initial decision, he smoked what would be his last cigarette. In doing so, he joined approximately 4.8 million Australian adults who identify themselves as former smokers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020h).

Shortly after he finally stopped smoking, he was interviewed by a researcher working on the evaluation of a government media quit-smoking campaign. Rex joined those responding that they had seen the campaign; who said they strongly agreed that the campaign made them think about quitting; and who responded that “health reasons”, “social unacceptability” and “cost” were the three main reasons they stopped smoking.

The researchers subsequently wrote a scientific article where they claimed that their statewide media campaign was probably a key factor responsible for a quit rate within the state which was higher than that found in other states without such campaigns. This claim was based on extrapolations made from the sample of aggregated recent quitters like Rex.

Bringing the background into the foreground

While Rex provided the researcher with what he thought were the “main” reasons he decided to finally quit, the many other influences in the typical day just described were not irrelevant. They were just not top-of-mind. We might conceptualise the most acknowledged and frequently researched factors as foreground foci in tobacco control evaluation research. But there are also many complex “hidden in clear sight” background factors that rarely if ever are even acknowledged when researchers consider population-wide movements in smoking prevalence (Chapman 1999).

Hughes et al. encapsulated well the privileging of proximal factors over distal influences in accounting for cessation when they wrote in 2012, “we doubt that exposure to media advertisements on cessation would decrease the rate of relapse [to smoking] years after they were seen, but they may still be effective, even over the long-term, because they stimulated quit attempts while the advertisements were still airing” (Hughes, Cummings et al. 2012).

This is a remarkably myopic view of the way in which we should understand behaviour change. It is dismissive of the idea that decisions we take today could have anything to do with particular and many cumulative influences we may have been exposed to in sometimes even the distant past. It suggests that we change only in response to recent stimuli. And it overly atomises the part played by single variables like a particular anti-smoking message in the consolidating awareness of a broad canvas of negativity about continuing to smoke that eventually motivates cessation. Basic educational and child development psychology take it as elementary that early influences and life experiences are pivotal in influencing broad constructs like self-esteem, confidence and resilience. So the idea that exposure to anti-smoking influences in even the deep past could come home to roost much later when a confluence of more proximal, enabling factors fomented to make this happen is hardly a radical thought.

In 1998 Melanie Wakefield and Frank Chaloupka called for more attention from those in tobacco control to the description and quantification of tobacco control “inputs” (Wakefield and Chaloupka 1998). By this, they meant that we needed far more fine-grained detail about all the ingredients in a nation’s “black box” of tobacco control policies and actions aimed at reducing smoking. It was not good enough, for example, to just note and tick off that a nation had health warnings on packs, school anti-smoking curricula, anti-smoking media campaigns or smoke-free policies. Wakefield and Chaloupka noted that the preoccupation with outcomes in evaluation research was often accompanied by overly casual accounts of the policy and intervention variables that were assumed to be the causative factors potentially producing change. They argued for the further development of a range of indices to measure the comprehensiveness of tobacco control policies and programs.

And the reliability of claims about even seemingly black and white, uncomplicated components of tobacco control can sometimes be very poor. For example, when I wrote a situation report on Papua New Guinea for the WHO’s Western Pacific Office in 1987, PNG was about to introduce bans on tobacco advertising (Roemer 1993). In 1996, Hayman reported widespread tobacco advertising was still to be seen throughout the country, including music and sporting sponsorship (Hayman 1996). And in 2011, a review described the bans as very weak with over 85% of PNG youth reporting having seen tobacco advertisements (Cussen and McCool 2011). Similarly, many nations have passed smoke-free policy legislation but far fewer, particularly in low-income nations, ever implement the legislation in any way that such policies are often fully implemented and enforced in more affluent nations. My wife was a primary school teacher for nearly 40 years. Yes, she said, there was curriculum material on smoking available to use with children. But was it actually used in the way that maths, spelling, reading, art and music were always taught and never considered optional? No.

The call to better document tobacco control actions led to instruments to try and score the comprehensiveness of tobacco control policies and programs. Examples include Levy’s 2001 SimSmoke simulation model (Levy, Friend et al. 2001); Levy and others’ Tobacco Control Scorecard (2004 and 2017) (Levy, Chaloupka et al. 2004, Levy, Tam et al. 2018); Joossens and Raw’s 2006 Tobacco Control Scale (Joossens and Raw 2006); and the World Health Organization’s more simplified six policy domains MPOWER checklist from 2008 (Song, Zhao et al. 2016).

These were all important starts. But there can be large and important gaps between what those supplying information to researchers or the WHO for its regular updates on global progress in tobacco control enter into their questionnaires, and what actually happens in a country. Those requesting the information are often in no position to cross check these issues, particularly for low-income nations where the currency and quality of data is often poor. Across my career I’ve frequently seen evidence that such requests for information land on the desks of people who are either very unaware of the difference between what is meant to be the case and what is actually the case in a country. Sometimes this misinformation is deliberate, designed to not embarrass a country in international league tables on tobacco control practice when they have implemented very little.

News media coverage of tobacco control

Importantly, Wakefield and Chaloupka (Wakefield and Chaloupka 1998) also noted the need to quantify and account for “environmental” issues such as unpaid news media coverage of tobacco issues. This truly gigantic factor cannot be overemphasised. Were it possible to quantify all media coverage of tobacco in societies with 24-hour access to a multitude of radio, television, print media, the world wide web and social media, in aggregate, this coverage would routinely and massively eclipse even the most intensive coverage gained through formal, typically very time-limited, purchased public health campaigns.

Much of this huge reportage is far from being easily dismissed as inconsequential ephemera: some of the most potent and recalled episodes in the history of tobacco control have been powerful prime-time television documentaries, prolonged episodes such as the tsunami of previously secret internal tobacco documents being released before and after the US Master Settlement Agreement (Clegg Smith, Wakefield et al. 2003) and the coverage of legal cases, such as the late Rolah McCabe’s suit against British American Tobacco for promoting smoking to her when she was a teenager (Wakefield, McLeod et al. 2003). Such examples are newsworthy because they often embody time-honoured news values like injustice, corruption, predatory corporate behaviour, government incompetence, wolves in sheep’s clothing, duplicity and hypocrisy (Chapman 2007).

These news subtexts inflect the meaning of news stories about smoking and thereby shape public and political understanding of something ostensibly “factual” in ways that can in turn shape individuals’ understandings of the meaning of smoking and public health efforts to reduce it.

Tobacco control has long been highly newsworthy (Chapman 1989, Menashe and Siegel 1998, Champion and Chapman 2005). In 1995, 38% of all front pages of the Sydney Morning Herald carried at least one health story (Lupton 1995). Of these, tobacco stories ranked second after those about health services. From a journalist’s perspective, tobacco control offers rich pickings that often conform with editors’ notions of newsworthiness. This field is resplendent with stories of conflict, corruption, moral rectitude and reprobation. To the endless delight of the media, practically every organ of the body can be afflicted by tobacco use and tobacco’s stratospheric toll on health lends itself to numerous excursions into quantification rhetoric – efforts to make statistics memorable to audiences (Potter 1991). Celebrities’ efforts to quit or criticism directed at the influence of their smoking on young people are routine news events (Chapman and Leask 2001).

The media’s appetite for villains finds inexhaustible sustenance in the conduct of the tobacco industry, which has long provided a low benchmark for referencing ethical low-life. If you google “just like the tobacco industry”, oceans of examples of unethical conduct in a wide variety of other industries are instantly returned. At the October 2021 COP26 climate meeting in Glasgow, oil companies were likened to the tobacco industry in the way both engaged in denial about the health consequences of their products. Repeatedly casting the tobacco industry in such an unfavourable light seems likely to be associated with the community’s ranking of tobacco industry representatives’ trustworthiness as lower than that of a used-car salesman, the traditional low standard for ethical behaviour (Chapman 2020). This in turn strengthens the hand of governments wanting to introduce tough tobacco control legislation.

The Australian Health Minister, Nicola Roxon, is responsible for introducing plain tobacco packaging, which commenced in December 2012. When I asked her about the political conditions that allowed her to pursue this radical policy, she said she was emphatic the tobacco industry’s appalling reputation as corporate pariahs was important in this decision:

When the taskforce report came, marshalling all the evidence for various measures including plain packaging, this was when I really started to give it serious thought. I can remember one of my advisors, on my personal staff, not the bureaucrats, saying to me well, this is just a “no-brainer”. Meaning, it might be new and bold, but it hit a political sweet spot too – you have good evidence, you have doctors and researchers on side, you’re trying to protect kids and the only one lining up against you is the tobacco industry. With a sceptical media and pretty well informed public, fighting such a discredited industry was not as dangerous as people thought (Chapman and Freeman 2014).

That corporate bottom-dwelling reputation did not happen serendipitously. It was the result of decades of tobacco control advocacy which helped focus news media attention on the industry’s nefarious activities and the ever-increasing resultant related public and cross-party political antipathy toward Big Tobacco.

There can be few more important questions for tobacco control than better understanding the complex nature of dominant forces driving regret and this antipathy to smoking and the powerful industry that seeks to perpetuate it. There are also few more perplexing questions than why the study of this messy complexity does not command the same or greater research attention as the study of discrete, easily quantified and often sponsored interventions typically generates. The research privileging of sponsored interventions and the comparative neglect of the study of ubiquitous background media “noise” about smoking, such as the examples given earlier, is probably best explained by the political imperatives for evaluation: funding agencies want to know what their campaign investment has achieved and may be less concerned about issues they feel they do not control, or for which they cannot take credit.

That said, decades of experience and evidence show that there are several undeniably foundational factors in any comprehensive national tobacco control program. I’ll now look at some of the most important of these.

Health concerns

Smoking of course kills. And when ex-smokers are asked about why they quit, health concerns have always been the overwhelming reason given for quitting (for example, 92% in this longitudinal study (Hyland, Li et al. 2004), followed by cost, way back at 59%, and why 90% of smokers regret that they ever started (Fong, Hammond et al. 2004). In the vast and endlessly repetitive research literature on this question, there is typically daylight between health concerns as the first nominated reason given by smokers for quitting, and every other factor named by ex-smokers and those trying to quit.

Years of smoking can cause serious, often lethal damage to practically every part and system of the body. While many smokers subscribe to a constellation of self-exempting, rationalising beliefs designed to reduce the cognitive dissonance between what they do (smoke) and what they know (smoking is profoundly unhealthy) (Chapman, Wong et al. 1993, Oakes, Chapman et al. 2004), avoidance of frequent negative information and comments about smoking is increasingly difficult.

Yet one of the most bizarre and enduring beliefs I’ve heard countless times across my career in public health has been from those who say to you knowingly, “Well, it’s been shown that scare tactics just don’t work when you are trying to get people to change their behaviour.” I reply that I find that hard to believe, given that former smokers almost invariably cite concern about health consequences as the primary reason they quit; that upward of 90% of people in some nations have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 because they are very afraid of getting seriously ill and dying; or that the use of condoms in casual sex became very widespread after campaigns promoted it as the best way to avoid acquiring the dreaded HIV/AIDS and STDs or experiencing unwanted pregnancy. Yet many are still unconvinced, and the folk-wisdom meme of scare campaigns “not working” doggedly persists.

Many of the serious health consequences of smoking are hidden away in internal organs. Those with end-stage emphysema are not out in public doing their shopping or queuing next to you to enter a cinema. They are so disabled by their laboured breathing that they can barely walk across a room. They don’t get about much and don’t have a sign hanging around their necks saying, “My lungs are wrecked by years of smoking.” Those who have had feet or legs amputated after gangrene from peripheral vascular disease similarly don’t advertise their experience so that observers understand that this was also something caused by smoking.

So where, then, do people find out about these often hidden-away diseases and their links with smoking? They read about it all in news reports about the toll of smoking. They see forthright information campaigns on television, on graphic tobacco-pack warnings and in occasional documentaries which explain the links, people suffering these conditions voice their regret and health care workers express their anger at the tobacco industry.

Yet some have argued that setting out to worry or scare people into adopting or avoiding various behaviours like smoking is “unethical”. In 2018, I looked critically at this proposition in the American Journal of Public Health (Chapman 2018). An edited version of that paper follows.1

Is using scare tactics unethical?

The efficacy and ethics of fear campaigns are enduring, almost perennial debates in public health which re-emerge with whack-a-mole frequency, eloquently chronicled by Fairchild et al (Fairchild, Bayer et al. 2018). Driven by evidence-based reasoning about motivating behaviour change and deterrence (Wakefield, Loken et al. 2010), these campaigns intentionally present disturbing images and narratives designed to arouse fear, regret and disgust.

Smoking causes a huge range of health problems which currently cause the deaths of up to two in three long-term smokers (Banks, Joshy et al. 2015) with an annual global death toll of some eight million (Global Burden of Disease 2019 Tobacco Collaborators 2021). Some of the health problems which eventually cause death, like respiratory and cardiovascular disease, can cause smokers many years of disability and wretched quality of life. Much of the damage being caused over years of smoking is internal and non-symptomatic until disease is well advanced.

Health problems can be profoundly negative experiences unappreciated by those not living with them. Pain, immobility, disfigurement, depression, isolation and financial problems are common sequelae or consequences of disease and injury. It is beyond argument that these are outcomes which are self-evidently anticipated and experienced as adverse, undesirable and so best avoided. Efforts to prevent them are therefore, prima facie, ethically beneficent and virtuous.

Five main criticisms

Criticism of the ethics of fear messaging has taken five broad directions. First, it is often asserted that fear campaigns should be opposed because they are ineffective: they simply “don’t work” very well and even worse, might backfire and perversely promote the very things they are supposed to be preventing. Fairchild et al. note that this argument persists despite the weight of evidence (Fairchild, Bayer et al. 2018). One 2015 meta-analysis of the research literature on the use of fear in health communication concluded:

Overall, we conclude that (a) fear appeals are effective at positively influencing attitude, intentions, and behaviors; (b) there are very few circumstances under which they are not effective; and (c) there are no identified circumstances under which they backfire and lead to undesirable outcomes (Tannenbaum, Hepler et al. 2015).

The ineffectiveness argument can be valid independent of the content of failed campaigns: “positive” ineffective campaigns should also be subject to the same criticism. Yet sustained criticism of ineffective “positive” campaigns is uncommon, suggesting this criticism is enlisted to support more primary objections about fear campaigns.

Victim blaming?

Second, critics argue that such campaigns target victims, not causes of health problems, and so are soft options mounted in lieu of more politically challenging “upstream” policy reform of social determinants of health such as education, employment or income distribution, or legislative, fiscal and product safety law reforms.

However, it is difficult to recall any major prescription for prevention in the last 40 years not involving advocacy for comprehensive strategies of both policy reforms and motivational interventions. For example, tobacco control advocates target advertising bans, smoke-free policies, and tax rises as well as increased public awareness campaign financing. When governments fail to enact comprehensive approaches to prevention, supporting only public awareness campaigns, this is plainly concerning. The resultant concentration of public discourse around the importance of individualistic change instead of systemic, legislative or regulatory change in controlling health problems may lead to public perceptions that solutions are mostly contingent on what individuals do or don’t do (Bonfiglioli, Smith et al. 2007). This myopic definition of health problems and their solution promotes victim blaming (Crawford 1977), where notions of individual responsibility are held to explain all health problems when any volitional component is involved.

This can be a serious criticism of failed government commitment to prevention, but is it a fair and sensible criticism of public awareness campaigns in themselves? Those making this argument draw the meritless implication that until governments are prepared to embrace the full panoply of policy and program solutions to health problems, they should not implement any individual element of such comprehensive approaches: if you cannot do everything, don’t do anything.

Further, in any public health utopia where governments enacted every platform of comprehensive programs and made radical political changes addressing the social determinants of health, every health problem with a behavioural, volitional component would still require individuals to make choices to act and to be sufficiently motivated to do so. Campaigns to inform and motivate such changes will always be needed. The reductio ad absurdum of this objection is that attention-getting warning signs and poison labels are unethical.

Stigmatisation

Third, those who live with the diseases or practice the behaviours that are the focus of these campaigns can sometimes experience themselves as having what sociologist Erving Goffman called “spoiled identities” (Goffman 1963) and may feel criticised, devalued, rejected and stigmatised by others. The argument runs that these campaigns “ignore evidence that stigma makes life more miserable and stressful and so is likely to have direct health effects” and fail to recognise that the stigmatised health states or behaviours “travel with disadvantage” (Carter, Cribb et al. 2012).

Criticism of fear campaigns is mostly applied to health issues where personal behaviour as opposed to public health and safety is the focus. Campaigns seeking to stigmatise and shame alcohol and drug-affected driving, environmental polluters, domestic violence perpetrators, sexual predators, owners of savage dogs, or restaurant owners with unhygienic premises are rarely criticised. Some people deserve to be stigmatised, apparently.

Prisoners of structural constraints?

A fourth argument used against fear campaigns is that many personal changes in health-related behaviour are difficult, requiring physical discomfort, perseverance, sacrifice and sometimes major lifestyle change, often limited by structural impediments like poor access to safe environments, cost, and work and family constraints.

But unless one subscribes to an unyielding, hard determinist position that people have no agency and are total prisoners of social and biological determinants, the idea that individuals even in the direst of circumstances cannot make changes in their lives when motivated to do so is an extreme position, difficult to sustain. It is instructive, for example, to reflect that today in many nations, it is only a minority of the lowest socioeconomic group who still smoke.

Is it always wrong to upset people?

Perhaps the most common argument, though, is that we should always avoid messaging which might upset people. This argument has two subtexts. First, an assumption is made that how people feel about something ought to be inviolate and to challenge it is disrespectful. But we all have our views challenged often on many things, and some of those challenges motivate reflection and change, and in the process make us sometimes feel uncomfortable. Why is the goal of avoiding any communication which might make people feel uncomfortable or self-questioning, self-evidently a noble, ethical criterion in the ethical assessment of public health communication?

Here, feelings about desirable health-related practices often reflect powerfully promoted commercial agendas to normalise practices like over-consumption, poor food choices, and addiction. The notion that such agendas should be not challenged out of some misguided fear of offending those who are its victims would see the door held open even wider to those commercial forces seeking to turbo-charge the impacts of their health-damaging campaigns. If a smoker gets comfort and self-assurance from inhabiting the commercially contrived meanings of smoking promoted through tobacco advertising, should we suspend strident criticism of tobacco marketing because it might be disrespectful of smokers?

It is a perverse set of ethics that sees it as virtuous to keep powerful, life-changing information away from the community simply because it upsets some people (Chapman 1988). Should we really tip-toe around, say, vividly illustrating how deadly sunburn can be through fear of offending some of those who value tanning? While advertising that vividly portrays the carnage and misery caused by speed and intoxicated driving may upset some people who are quadriplegic, how do we balance the support for such campaigns by others now living that way and evidence that fear of public shame and personal remorse works to deter both? And if ghoulish pack-warning illustrations of tobacco-caused disease like gangrene and throat cancer render the damage of smoking far more meaningful than more genteel explanations, whose interests are served by decrying such depictions as being somehow unethically disturbing?

Some in the community do not like encountering confronting information that challenges their ignorance or complacency, but public health is not a popularity contest where an important criterion for assessing the merits of a campaign is the extent to which it is liked.

Fairchild et al.’s paper (Fairchild, Bayer et al. 2018) is a superb contribution to the public health communication field’s confused thinking on fear appeals in public health and deserves wide discussion.

Recent neglect of public awareness campaigns

Australia had long been a global leader in mass-reach, hard-hitting, government-funded public awareness campaigns. Across different periods, these campaigns have been run by state health and federal departments. Quit Victoria’s encyclopaedic Tobacco in Australia website documents all of these campaigns in great detail (Bayly, Carroll et al. 2021). In particular, between 1997 and 2001, a national campaign well funded by the federal government, Every Cigarette is Doing You Damage, was run. The campaign featured six see-once-and-never-forget advertisements focusing on different health consequences of smoking (Chapman, Hill et al. 1998). A whole supplement of research papers on the development, implementation and impact of this campaign was published in Tobacco Control in 2003 (Various authors 2003).

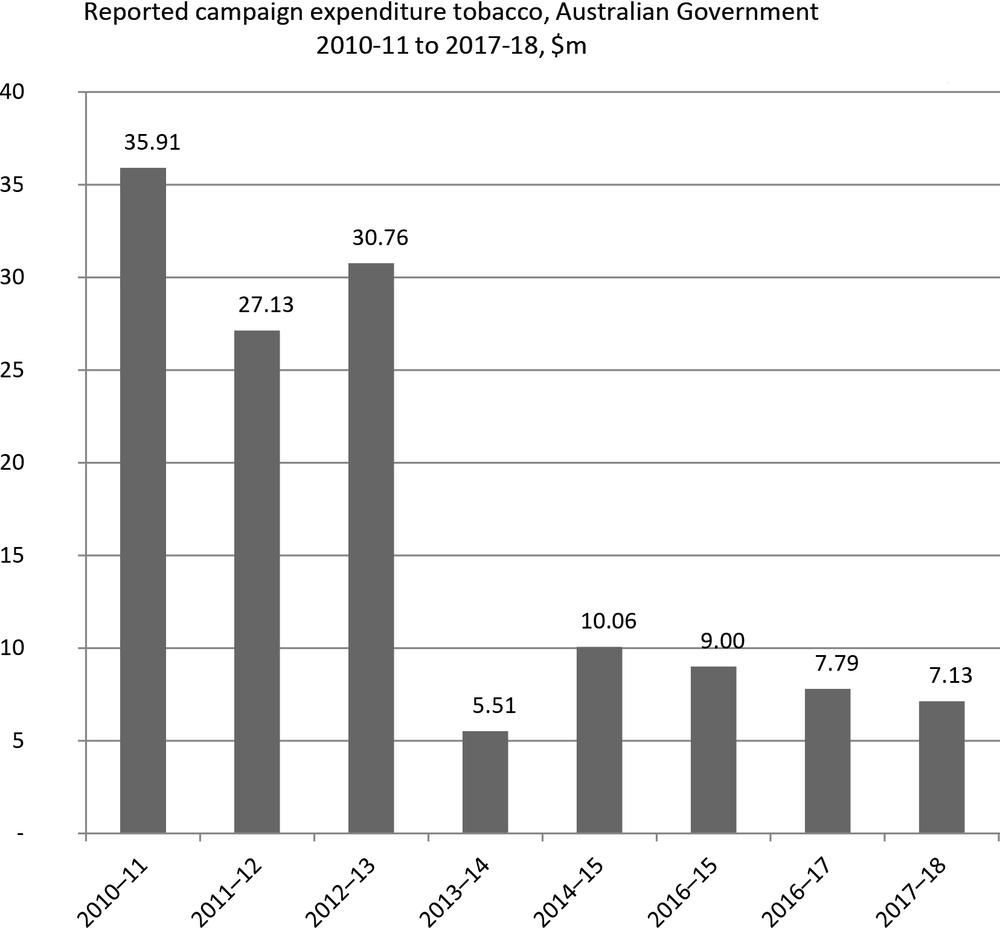

But while Australian governments have long been magnificent in being in the global vanguard of legislative initiatives like complete advertising bans, high tobacco tax, plain packaging and smoke-free public spaces, in recent years they have taken their minds well off the importance of significantly funding mass-reach campaigns. Figure 8.1 below shows the fall-off in federal government funding across recent years. State health departments have run many campaigns in the years since.

Figure 8.1 Annual federal government expenditure on anti-smoking advertising campaigns by financial year, adjusted for inflation to 2018 ($millions) (Source: Figure 14.3.2 in Bayly, Carroll et al. 2021).

Australian governments were among global pioneers in funding large-scale often powerfully motivating public awareness campaigns as flagship components of comprehensive tobacco control campaigns. Regrettably, support has been desultory in the years since 2013. This has not been because the campaigns haven’t worked but almost certainly because of the confluence of two factors:

- The persistence of the erroneous view that such campaigns have achieved all they could have achieved and that remaining smokers are impervious to persuasions not to smoke (the hardening hypothesis discussed in Chapter 5).

- Most recently, the “all hands on deck” effect of COVID-19 in vacuuming almost all the attention of health authorities and seeing many health promotion staff seconded into COVID-19 related work.

If Australia is to reduce the gap between population subgroups which now have sub-10% smoking prevalence and those which sometimes have double or more those rates, re-investment in mass-reach campaigns should be at the very top of advocates’ priority lists.

Tobacco taxation

There is popular cynicism that governments tax tobacco only because it is an ageless, endlessly fertile goose that just keeps laying massively lucrative golden revenue eggs. Tobacco tax including 10% added Goods and Services Tax (GST) comprised $15.744 billion (3.39%) of the $464.1 billion in total tax revenue raised by the Australian Commonwealth government in 2020–21. The government’s December 2021 Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) also estimated that there was a significant downward trend of 9.8% likely to occur (Commonwealth of Australia 2021).

Tobacco tax certainly raises considerable revenue, but after health concerns, it is also widely regarded as the single most important factor driving down smoking, a conclusion drawn as far back as 1999 by the World Bank (The World Bank 1999). So it is a massively important win–win policy for both governments and public health. Over decades, internal tobacco industry documents have repeatedly shown their full awareness of this. Tobacco company Philip Morris (Australia) in 1983 said: “The most certain way to reduce consumption is through price” (Philip Morris Records 1983). Then again in 1985:

Of all the concerns, there is one – taxation – which alarms us the most. While marketing restrictions and public and passive smoking do depress volume, in our experience taxation depresses it much more severely. Our concern for taxation is, therefore, central to our thinking about smoking and health. It has historically been the area to which we have devoted most resources and for the foreseeable future, I think things will stay that way almost everywhere (Philip Morris International 1985).

And in 1993: “A high cigarette price, more than any other cigarette attribute, has the most dramatic impact on the share of the quitting population” (Schwab 1993).

In late April 2010, Australia’s Rudd Labor government raised the tobacco tax unannounced and overnight by an unprecedented 25%, and at the same time announced its historic plain packaging plans, eventually implemented in December 2012. A 2010 Treasury paper modelled the likely impact of the 25% rise (Department of the Treasury 2010). They predicted that the 25% tax increase would see a decline in tobacco consumption of approximately 8% and an increase of 15% in tax revenue. But another Treasury paper from 2013 showed that this increase in fact reduced consumption of dutied tobacco products by 11% (Australian Treasury 2013).

British American Tobacco’s then boss in Australia, David Crow, publicly acknowledged the impact of the tax in 2011, telling a parliamentary committee:

We saw that [tobacco tax reduces sales] last year very effectively with the increase in excise. There was a 25% increase in the excise and we saw the volumes go down by about 10.2%; there was about a 10.2% reduction in the industry last year in Australia (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health 2011).

In 2019, Wilkinson et al. examined the impact on Australian smoking prevalence on those aged 14+ of the 2010 25% increase which was followed by annual 12.5% increases commencing in December 2013 (Wilkinson, Scollo et al. 2019). They reported that the 25% tax increase was associated with both immediate (−0.745 percentage points) and sustained reductions in smoking prevalence (monthly trend −0.023 percentage points). This was driven by reductions in the prevalence of smoking of factory-made cigarettes. However, the prevalence of smoking cheaper and (then) lower-taxed roll-your-own tobacco increased between May 2010 and November 2013. Immediate decreases in smoking and changing trends in the prevalence of smoking of roll-your-own were most evident among groups with lower socioeconomic status.

The global tobacco industry’s stock line on tax-induced price rises has long been a “look-over-here” strategy where it seeks to frame the main effect of rising prices as being a stampede by smokers to buy illicit, duty-not-paid cigarettes. It has invested heavily in commissioning reports from prominent global accountancy firms to argue that tax rises drive price-sensitive smokers to purchase illicit duty-not-paid cigarettes which are much cheaper. Some of these reports have claimed as many as 1 in 6 of all cigarettes smoked in Australia are sourced from illicit trade.

Two websites, one maintained by Michelle Scollo at the Cancer Council Victoria (Scollo 2020) and one developed by the Tobacco Tactics project at the University of Bath (Tobacco Tactics 2020b) are peerless as sources of evidence and critical analysis of the often outrageous industry claims made about illicit tobacco trade, particularly in the Australian context. A 2012 review of well over 100 empirical studies of the impact of taxation on tobacco consumption concluded:

tobacco excise taxes are a powerful tool for reducing tobacco use while at the same time providing a reliable source of government revenues. Significant increases in tobacco taxes that increase tobacco product prices encourage current tobacco users to stop using, prevent potential users from taking up tobacco use, and reduce consumption among those that continue to use, with the greatest impact on the young and the poor (Chaloupka, Yurekli et al. 2012).

A systematic review of the quality of evidence commissioned or promoted by the tobacco industry on the extent of illicit tobacco trade (ITT) identified problems with “data collection, analytical methods and presentation of results, which resulted in inflated ITT estimates or data on ITT that were presented in a misleading manner. Lack of transparency from data collection right through to presentation of findings was a key issue with insufficient information to allow replication of the findings frequently cited” (Gallagher, Evans-Reeves et al. 2019).

If illicit tobacco were as easy to obtain as the tobacco industry argues, how is it that ordinary smokers, who are increasingly drawn from less-educated population groups, can manage to find where to buy them with alleged consummate ease, while the full resources of the Australian Federal Police and tax office inspectors cannot manage to do so very often? Australia has always scored very low on indexes of corruption. It currently ranks 11th least corrupt out of 179 nations (Transparency International 2021). So suggestions that police and border force officials collude with criminals importing and distributing smuggled tobacco have little credibility.

Most amusing of all here is the duplicity of Big Tobacco’s unctuous posturing about heinous tax rises encouraging smuggling and tax avoidance, when the industry uses these rises as cover to camouflage increases in its own margins. The Cancer Council Victoria’s research on price changes after plain packaging reveal this. From August 2011 to February 2013, while excise duty rose 24¢ for a pack of 25 cigarettes, the tobacco companies’ portion of the cigarette price (which excludes excise and GST), jumped $1.75 to $7.10 (Scollo, Bayly et al. 2015). While excise had risen 2.8% over the period, the average net price rose 27%. Philip Morris’ budget brand Choice 25s rose $1.80 in this period, with only 41¢ of this being from excise and GST. Later work showed that across three years tobacco retail price increases were above the combined effects of inflation and increases in excise and customs duty (Egger, Burton et al. 2019). Moreover, there is a large body of evidence that transnational tobacco companies have had major ongoing involvement in facilitating global tobacco smuggling (Gilmore, Fooks et al. 2015, Gilmore, Gallagher et al. 2019, Tobacco Tactics 2020b).

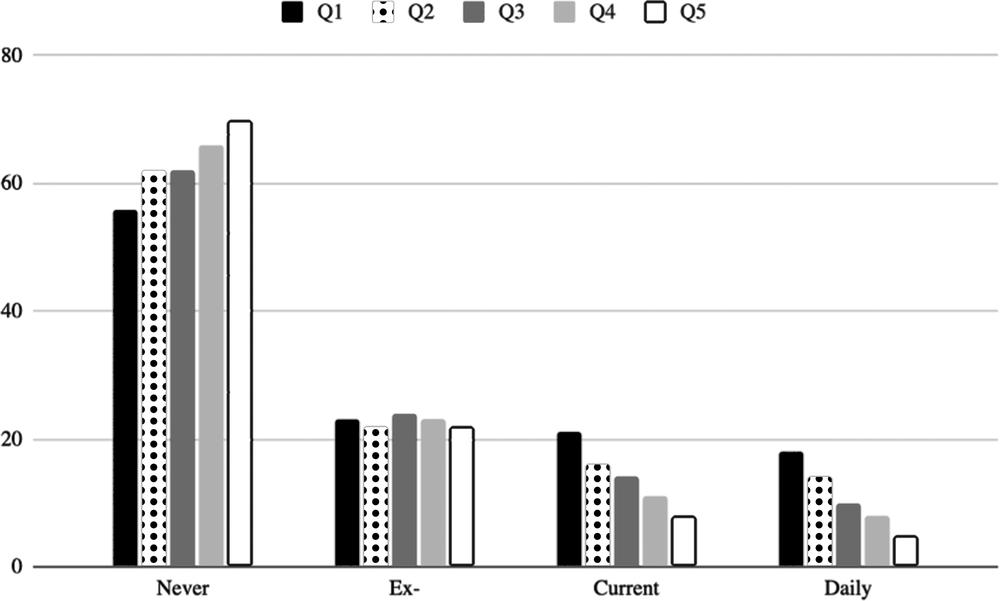

It’s often erroneously argued that those on low incomes are impervious to tobacco control measures like price rises, and suffer further deprivation with each price rise. Tobacco control is alleged to be “taking food out of children’s mouths and new clothing off their backs” because of outrageous taxes. Figure 8.2 below shows the smoking status of Australians aged 14 and over in 2019 across five quintiles of social disadvantage. As can be seen, there is not a lot of difference in the proportion of ex-smokers across the quintiles.

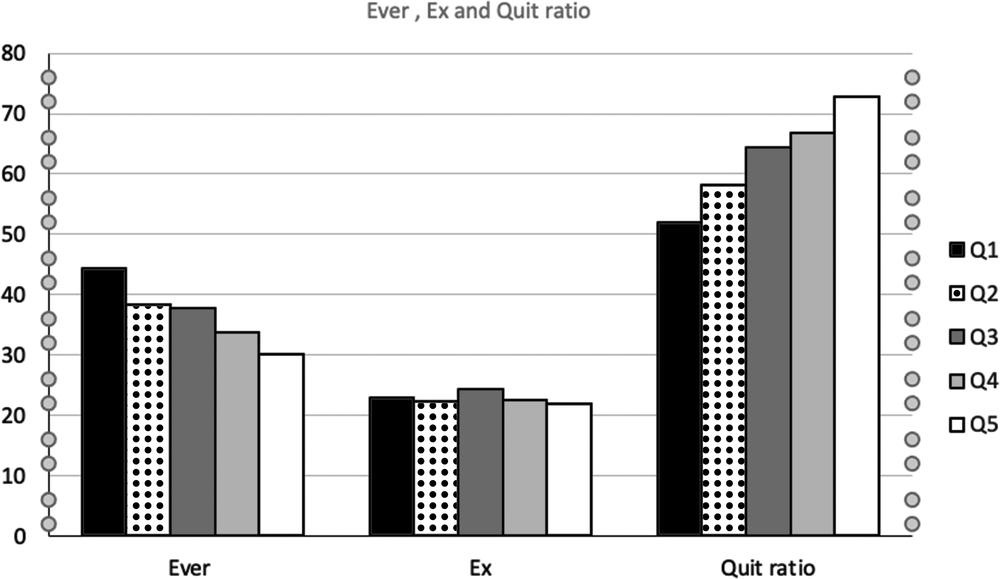

However, these apparent similarities are due to big differences across socioeconomic quintiles in the proportions who have ever smoked. Instead, the “quit ratio” (the proportion of ever smokers who are former smokers) is the key indicator here (see Table 8.3 below). As can be seen, in 2019 some 52 % of people who ever smoked in the lowest quintile have quit, compared with nearly 73% of those who have ever smoked in the highest quintile.

Taking up smoking is much more common if you are less educated and unskilled than the obverse – a glass half empty observation. But the glass half full, more optimistic observation is that a clear majority of every socioeconomic group in Australia today have never smoked, thanks to the impact of preventive tobacco control.

Figure 8.2 Never, ex-, current and daily smoking prevalence by five quintiles of social disadvantage (1 = highest disadvantage 5 = lowest) Australians aged 14+ 2019 (Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020e).

Figure 8.3 Quit ratios (proportion of ever smokers who are former smokers) by five quintiles of social disadvantage (1=highest disadvantage 5= lowest) Australians aged 14 and over, 2019 (Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020e).

1 Reproduced from American Journal of Public Health, S Chapman, Is it Unethical to Use Fear in Public Health Campaigns? September 2018; 108(9): 1120–1122 with permission from The Sheridan Press on behalf of the American Public Health Association.