7

Insights from qualitative research with unassisted quitters

Self-change research pioneers Harald Klingemann, and Mark and Linda Sobell have emphasised that “When treatments are perceived as overly intensive, demeaning and requiring unnecessarily severe changes in life-style, they lack appeal and are unlikely to be utilized”, that “it needs to become common knowledge among the public that self-change is a frequent occurrence” and that “We need to develop new ways of assessing ‘tacit knowledge’ from various angles because ‘people know more than they can say’” about pathways out of addiction (Klingemann, Sobell et al. 2010).

These three wise observations were at the heart of a three-year NHMRC study I led titled The natural history of unassisted smoking cessation in Australia. From knowing that unassisted smoking cessation was comparatively massively understudied compared to assisted cessation methods (Chapman and MacKenzie 2010), we were curious if qualitative researchers had shone their torches on this phenomenon and explored insights hidden among the vast numbers of ex-smokers who had quit on their own. Our work used grounded theory and an interpretive, social constructionist approach (Charmaz 1990, Charmaz 2006) to explore the factors associated with successful quitting in a sample of ex-smokers who had quit between six months and two years earlier. A social constructionist approach allowed the exploration of the subjective and complex experiences of participants to provide an account of how ex-smokers understood and made sense of the process of successful quitting that they had used.

Our research led to seven published papers (Smith and Chapman 2014, Smith, Carter et al. 2015a, Smith, Carter et al. 2015b, Smith, Chapman et al. 2015, Smith, Carter et al. 2017, Smith, Carter et al. 2018, Smith 2020) and a PhD thesis written by Andrea Smith who was employed on the grant and led the writing on all of the papers.

This chapter is an edited amalgam of two of these papers: a synthesis of the findings of all qualitative research on unassisted cessation, The views and experiences of smokers who quit smoking unassisted. A systematic review of the qualitative evidence (Smith, Carter et al. 2015b) and Why do smokers try to quit without medication or counselling? A qualitative study with ex-smokers published in BMJ Open (Smith, Carter et al. 2015a). I have edited both papers to concentrate on the research questions addressed, principal findings and discussion sections of the papers. Readers are referred to the papers, both published in open access, for the complete texts, tables, figures and references.

Paper 1: The views and experiences of smokers who quit unassisted. A systematic review of the qualitative evidence

Research into smoking cessation has achieved much. Researchers have identified numerous variables related to smoking cessation and relapse, including heaviness of smoking, quitting history, quit intentions, quit attempts, use of assistance, socioeconomic status, gender, age, and exposure to mass-reach interventions such as mass media campaigns, price increases and retail regulation. Behavioural scientists have developed a range of health behaviour models and constructs relevant to smoking cessation, such as the theory of planned behaviour, social cognitive theory, the transtheoretical model and the health belief model. These theories have provided constructs to smoking cessation research such as perceived behavioural control, subjective norms (Azjen 1991), outcome expectations, self-regulation (Vohs, Baumeister et al. 2017), decisional balance (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983), perceived benefits, perceived barriers and self-efficacy (Becker 1974). The knowledge generated has informed the development of a range of pharmacological and behavioural smoking-cessation interventions.

Yet, although these interventions are somewhat efficacious, as we have seen throughout the book the majority of smokers who quit successfully do so without using them, choosing instead to quit unassisted; that is, without pharmacological or professional support (Edwards, Bondy et al. 2014, Smith, Chapman et al. 2015). Many smokers also appear to quit unplanned as a consequence of serendipitous events (West and Sohal 2006), throwing into question the predictive validity of some of these cognitive models. The enduring popularity of unassisted cessation persists even in nations advanced in tobacco control where cessation assistance such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and the stop-smoking medications bupropion and varenicline are readily available and widely promoted. Yet little appears to be known about this population or this self-guided route to cessation success. In contrast, the phenomenon of self-change (also known as natural recovery) is comparatively well documented in the fields of drug and alcohol addiction (Miller and Smith 2010, Slutske 2010), and health behaviour change (for example, eating disorders, obesity and gambling) (Sobell 2007).

In our systematic review of unassisted cessation in Australia (Smith, Chapman et al. 2015) we established that the majority of contemporary cessation research is quantitative and intervention focused (Kluge 2009). While completing that review we determined that the available qualitative research was concerned primarily with evaluating smoker and ex-smoker perceptions of mass-reach interventions such as marketing or retail regulations, tax increases, graphic health warnings, smoke-free legislation or intervention acceptability from the perspective of the GP, current smoker, or third parties likely to be impacted by mass-reach interventions. Australian smoking-cessation research provided few insights into quitting from the perspective of the smoker who quits unassisted. However, our systematic review highlighted that 54% to 69% of ex-smokers quit unassisted and 41% to 58% of current smokers had attempted to quit unassisted (Smith, Chapman et al. 2015).

We consequently became interested in what the qualitative cessation literature had to say about smokers who quit unassisted. Qualitative approaches offer an opportunity to explain unexpected or anomalous findings from quantitative research and to clarify relationships identified in these studies (Dixon-Woods, Agarwal et al. 2004, Atkins, Lewin et al. 2008). By integrating individual qualitative research studies into a qualitative synthesis, new insights and understandings can be generated and a cumulative body of empirical work produced (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009). Such syntheses have proved useful to health policy and practice (McDermott, Graham et al. 2004, Thomas and Harden 2008). By focusing our review on the views of smokers (i.e. on the people to whom the interventions are directed), we might start to better understand why many smokers continue to quit unassisted instead of using the assistance available to them. Such an understanding might help us to decide whether we should be developing better approaches to unassisted cessation or focusing our attention on directing more smokers to use the efficacious pharmacological and professional behavioural support that already exists.

In this review, we examined the qualitative literature on smokers who quit unassisted in order to answer the following research questions: (1) How much and what kind of qualitative research has explored unassisted cessation? (2) What are the views and experiences of smokers who quit unassisted? Our search strategy (see original article for full description) found just 11 eligible qualitative papers.

Research question 1: How much and what kind of qualitative research has explored unassisted cessation?

The earliest study identified was a 1977 US study investigating why smokers seeking treatment (psychotherapy) often fared no better than smokers who quit unassisted (Baer, Foreyt et al. 1977). This was followed in the late 1980s and 1990s by studies (from the US and Sweden) investigating unassisted cessation as a phenomenon in its own right (Solheim 1989, Mariezcurrena 1996, Stewart 1999), and one US study in which unassisted cessation data were reported but this was not the primary focus of the study (Thompson 1995). Subsequent to this, no qualitative studies were identified that focused on unassisted cessation per se: the six post-2000 studies (from Hong Kong, US, UK, Canada and Norway) had as their primary focus either cessation in general (Abdullah and Ho 2006, Nichter, Nichter et al. 2007, Bottorff, Radsma et al. 2009, Murray, McNeill et al. 2010, Medbø, Melbye et al. 2011) or health behaviour change (Ogden and Hills 2008).

Research question 2: What are the views and experiences of smokers who quit unassisted?

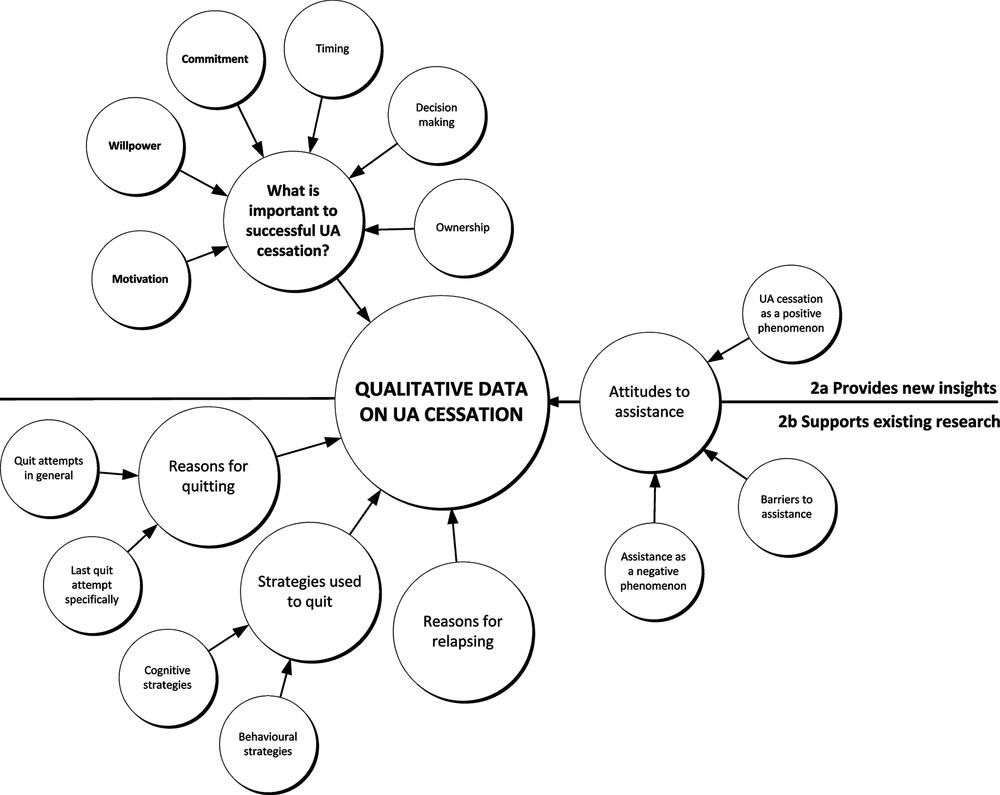

The full set of concepts derived from the qualitative literature were grouped into those that included descriptive themes that have already been covered in the literature (Figure 7.1 below the line) and those concepts that included descriptive themes that provided potentially new insights into unassisted cessation (Figure 7.1 above the line). The existing quantitative smoking-cessation literature had, for example, already often reported on attitudes to assistance, reasons for quitting, strategies used to quit and reasons for relapsing. While encouraged by the consistency between the qualitative and quantitative studies, our aim was to focus on what the qualitative literature could report from the smokers’ perspective about quitting unassisted that had the potential to offer new or alternative insights into the process or experience of unassisted cessation. From this perspective the most interesting themes were those that related to three concepts: (1) motivation; (2) willpower; and (3) commitment. Four further concepts (timing, decision making, ownership and the perception that quitting unassisted was a positive phenomenon) were of interest but insufficient data were available on which to base an analysis.

Figure 7.1 Themes and concepts derived from the 11 primary studies. Source: (Smith, Carter et al. 2015b).

Although these concepts appear in the literature on smoking cessation, below we explore the meaning of these concepts as defined by smokers and ex-smokers who have quit unassisted, as well as the researchers who studied them.

Motivation. Although motivation was widely reported, it was difficult to discern exactly what motivation meant to smokers as opposed to researchers. Smokers rarely talked directly about motivation or used the word motivation to describe their quit attempt. Yet motivation was frequently included in the accounts researchers gave of how and why smokers quit.

That is, there appeared to be a disjunct between the way that researchers talked about motivation and the way that ex-smokers understood it. On looking at the data related to motivation it became clear to us that when researchers talked about motivation they were in fact talking almost exclusively about reasons for quitting. Typical reasons included cost, a sense of duty, health concerns, feeling out of control, feeling diminished by being a smoker, deciding the disadvantages of smoking outweighed the benefits, or expectations that life would be better once they quit. We concluded that the data on motivation reported in these 11 qualitative studies added no new insights to the data on reasons for quitting which had not already been reported in the quantitative literature.

Smokers used the word motivation differently: not to describe the reason they quit, but to describe what sustained them through their quit attempt. We included these data (Stewart 1999) under the concept of commitment (see below). Our main conclusion about motivation was that smokers and researchers appear to be using the word to denote different concepts.

Willpower. The concept of willpower was clearly important to smokers and often used by researchers to account for smokers’ success or failure, but was rarely examined or unpacked. Willpower was reported to be a method of quitting, a strategy to counteract cravings or urges (much as NRT or counselling is regarded as a method of quitting or a way of dealing with an urge to smoke), or a personal quality or trait fundamental to quitting success. For example, although Ogden and Hill (2008) classified their participants according to whether they had “stopped smoking through willpower or a smoking course”, they gave no definition or explanation of what willpower was. Similarly, Thompson (1995) reported many participants used “sheer willpower to overcome the strong urges to smoke”, and Abdullah and Ho (2006) reported relapsed smokers cited “willpower and determination” as key factors for quitting success, but did not elaborate on what was meant by willpower. Stewart’s 1999 study of smokers who quit unassisted attempted to understand willpower from the smokers’ perspective, yet despite directly questioning smokers about willpower, Stewart could find no agreement among smokers as to what willpower was. In summing up, Stewart concluded: “it is difficult to connect a successful cessation attempt with the use of willpower without creating a tautology: one is successful if one has willpower, and one has willpower if one is successful” (Stewart 1999), capturing what is arguably still an issue in contemporary smoking-cessation research.

Commitment. Smokers’ talk about commitment was nuanced and multilayered. In contrast to motivation and willpower we did not need to rely upon the researchers’ interpretations to gain an insight into what commitment might mean to smokers. Smokers talked directly about being committed. To them it meant being determined, serious or resolute. Being committed was essential to their quitting success. Commitment was what differentiated a serious quit attempt from previous unsuccessful quit attempts, and was the hallmark of their final successful quit attempt.

Commitment could also be tentative or provisional. Medbø (2011) reported smokers who appeared keen to try to quit but were not necessarily committed to seeing the quit attempt through. It is possible a further level of commitment was being withheld, contingent perhaps on how difficult quitting turned out to be or on how the smoker felt about having quit once they got there. One of Stewart’s participants illustrated the difference, “OK I’m going to give this a valiant attempt and if it’s not going to work then I’ll go back to smoking and it will be OK.” The smoker is committed to trying but not necessarily committed to quitting.

Commitment could also be cumulative. Smokers talked about a point of no return, which described a point in the cessation process when they had made a firm commitment to quit, they had made a decision and they would not change their mind. Smokers described this as the point in time at which they believed there was too much invested to relapse now.

Discussion

In this review we synthesised the qualitative data reporting on the views and experiences of smokers who successfully quit unassisted (without pharmacological or professional behavioural support). The existence of only a handful of studies over more than 50 years, with no study specifically addressing unassisted cessation post-2000, indicates that up until now little research attention has been given to the lived experiences and understanding of smokers who successfully quit unassisted. As a consequence relatively little is known about smokers’ perspectives on what is the most frequently used means of quitting and the way described by the majority of ex-smokers as being the most “helpful” (Hung, Dunlop et al. 2011, Newport 2013). It is widely accepted that searching qualitative literature is difficult (McDermott, Graham et al. 2004, Shaw, Booth et al. 2004). Although it is possible that relevant studies were missed, given the comprehensiveness of our search strategy, the comparative lack of studies found through searching seems likely to reflect an evidence gap, and therefore an important area for future research.

This lack of qualitative research was unexpected for two reasons. First, we were aware of a small but not insubstantial body of quantitative evidence on smokers who quit unassisted; and second, in the course of our literature search we had identified a considerable number of qualitative studies on smoking cessation. On closer examination it became clear that few of these reported specifically on smokers who quit unassisted. This supports what Kluge found in 2009; that is, the qualitative smoking-cessation research that does exist is concerned primarily with evaluating the success or acceptability of smoking cessation interventions, particularly in vulnerable populations such as adolescents or the socially disadvantaged (Kluge 2009).

Concepts central to self-quitting

Motivation was identified as a central concept in this review, but analysis of the studies showed that motivation appeared primarily in the researchers’ accounts of quitting rather than in the smokers’ accounts of quitting. On closer examination, the data related to motivation consisted almost entirely of reasons for quitting. Within the quantitative literature on smoking cessation, motivation is an established psychological construct which has been operationalised in numerous studies designed to determine the role of motivation in quitting success (Borland, Yong et al. 2010, Smit, Fidler et al. 2011). Motivation has been identified as critical to explaining cessation success (Nezami, Sussman et al. 2003). The lack of explicit discussion about motivation by smokers who quit unassisted in the studies included in this review is therefore interesting. Though motivation could be inferred from the smokers’ accounts, it had to be done by using the variables that comprise motivation, such as reasons (motives) for quitting or the pros and cons of smoking versus quitting. Given the relative lack of data, it is difficult to conclude whether this is (1) because smokers do not talk directly about motivation, or (2) whether from the participants’ perspective motivation is not the driving force behind successful unassisted cessation (either because another concept is more important or because too much time has passed since their quit attempt for them and they have forgotten how important motivation was to them).

From the studies included in this review, it appears that – at least in smokers’ self-understanding – commitment might be more important than motivation as an explanation of successful unassisted cessation. The enthusiastic and explicit talk about being determined, committed or serious suggests that this concept resonates more with smokers than the concept of motivation. The overlapping and at times contradictory natures of commitment and motivation have been highlighted recently by Balmford and Borland who concluded that it may be possible to quit successfully while ambivalent, as long as the smoker remains committed in the face of ebbs and flows in motivation (Balmford, Borland et al. 2011) Further complicating the relationship, some regard commitment as a component of motivation, operationalising motivation as, for example, “determination to quit” (Segan, Borland et al. 2002) or “commitment to quit” (Kahler, Lachance et al. 2007).

The greater research interest in reasons for quitting or pros and cons of quitting (i.e. motivation) as opposed to commitment may be because motivation is simpler to measure; for example, by asking people to rate or rank reasons, costs or benefits. From a policy and practice perspective, it may also be easier to draw attention to these reasons, costs and benefits, rather than engage with commitment. For example, mass-media campaigns can remind smokers of why they should quit by pointing out the benefits to short-term and long-term health. However, this review draws attention to the importance of commitment for sustained quitting, at least from the point of view of smokers and quitters. The UK’s annual Stoptober campaign in which smokers committed to being smoke-free for 28 days indicates that creative approaches to addressing commitment can be successful (Public Health England 2013).

The final concept identified, willpower, was described in terms of multiple constructs (a personal quality or trait, a method of quitting, a strategy to counteract cravings or urges), suggesting smokers and researchers may use it as a convenient or shorthand heuristic when talking about or reporting on quit success. Despite this lack of clarity, the word has persisted in the qualitative and quantitative smoking cessation literature. It could be fruitful for future research to further examine the meaning of willpower, and particularly its relationship to other more tightly defined concepts such as self-efficacy (Etter, Bergman et al. 2000), self-regulation (Vohs, Baumeister et al. 2017) and self-determination (Deci and Ryan 2010), from the perspective of both researchers and smokers.

No matter how widely available and affordable smoking-cessation assistance becomes, it is likely there will always be a significant proportion of smokers who choose to quit unassisted. It is important to understand what drives these smokers to quit this way and to better understand their route to success. Orford and colleagues working on the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial made a strong case for including the client’s perspective, arguing that it is wrong to assume that clients have no perspective into their own change processes, and that we should resist the dominant “drug metaphor” which has adopted the model of an active professional applying a technique to a passive recipient (Orford, Hodgson et al. 2006). McDermott and Dobson also advocated for the need for contemporary public health policy to ground itself in the experiences of those whose lifestyles it seeks to change (McDermott, Dobson et al. 2006). As the vast majority of smokers who quit successfully continue to do so without formal help, it is likely that a better understanding of this experience, from the perspective of the smokers and ex-smokers themselves, could inform more nuanced and effective communication and support for quitting.

Conclusion

Our review identified three key concepts –motivation, willpower and commitment – circulating in smokers’ and ex-smokers’ accounts of quitting unassisted. Insufficient qualitative evidence currently exists to fully understand these concepts, but they do appear to be important in smokers’ and ex-smokers’ accounts and so worthy of research attention. A more detailed qualitative investigation of what motivation, willpower and commitment mean to smokers and ex-smokers would complement the existing body of behavioural science knowledge in tobacco control. A better understanding of these concepts from the smokers’ perspective may help to explain the often puzzling popularity of quitting unassisted rather than opting to use the efficacious pharmacological or professional assistance that is available. Health practitioners could potentially use such knowledge, in combination with what we already know from population-based research into smoking cessation, to better support all smokers to quit, whether or not they wish to use assistance.

Paper 2: Why do smokers try to quit without medication or counselling? A qualitative study with ex-smokers

Summary

Objective When tobacco smokers quit, between half and two-thirds quit unassisted: that is, they do not consult their GP, use pharmacotherapy (NRT, bupropion or varenicline) or phone a quitline. We sought to understand why smokers quit unassisted.

Design This was a qualitative grounded theory study (in-depth interviews, theoretical sampling, concurrent data collection and data analysis). Full details of design, sample selection and data coding and analysis can be read in the published paper.

Participants Twenty-one Australian adult ex-smokers were studied (aged 28–68 years; nine males and 12 females) who quit unassisted within the past six months to two years. Twelve participants had previous experience of using assistance to quit; nine had never previously used assistance.

Results Along with previously identified barriers to use of cessation assistance (cost, access, lack of awareness or knowledge of assistance, including misperceptions about effectiveness or safety), our study produced new explanations of why smokers quit unassisted: (1) they prioritise lay knowledge gained directly from personal experiences and indirectly from others over professional or theoretical knowledge; (2) their evaluation of the costs and benefits of quitting unassisted versus those of using assistance favours quitting unassisted; (3) they believe quitting is their personal responsibility; and (4) they perceive quitting unassisted to be the “right” or “better” choice in terms of how this relates to their own self-identity or self-image. Deeply rooted personal and societal values such as independence, strength, autonomy and self-control appear to be influencing smokers’ beliefs and decisions about quitting.

Conclusions The reasons for smokers’ rejection of the conventional medication model for smoking cessation are complex and go beyond modifiable or correctable problems relating to misperceptions or treatment barriers. These findings suggest that GPs could recognise and respect smokers’ reasons for rejecting assistance, validate and approve their choices, and modify brief interventions to support their preference for quitting unassisted, where preferred. Further research and translation may assist in developing such strategies for use in practice.

Introduction

Smoking-cessation researchers, advocates and healthcare practitioners have tended to emphasise that the odds of quitting successfully can be increased by using pharmacotherapies, such as NRT, bupropion and varenicline, or behavioural support such as advice from a healthcare professional or from a quitline. However, instead of using one or more of these forms of assistance, most quit attempts have always and continue to be unassisted and most long-term and recent ex-smokers quit without pharmacological or professional assistance.

Researchers have identified a number of issues relating to the choice to use assistance. They generally conclude that failure to use assistance can be explained by treatment-related issues such as cost and access, and patient-related issues such as lack of awareness or knowledge about assistance, including misperceptions about the effectiveness and safety of pharmacotherapy or concerns about addiction (Etter and Perneger 2001, Bansal, Cummings et al. 2004, Gross, Brose et al. 2008, Shiffman, Ferguson et al. 2008).

The policy and practice response to the low uptake of cessation assistance has typically focused on improving awareness of, access to and use of assistance – in particular, pharmacotherapy. NRT, bupropion and varenicline are often provided free of charge or heavily subsidised by the government or health insurance companies. NRT is on general sale in pharmacies and supermarkets, and is widely promoted through direct-to-consumer marketing. Clinical practice guidelines in the UK, USA and Australia advise clinicians to recommend NRT to all nicotine-dependent (>10 cigarettes per day) smokers. Specialist stop-smoking clinics, and dedicated telephone and online quit services provide smokers with tailored support and advice. These products and services have not had the population-wide impact that might have been expected from clinical trial results (Wakefield, Durkin et al. 2008, Zhu, Lee et al. 2012, Wakefield, Coomber et al. 2014), leading some researchers to suggest that patient-related barriers such as misperceptions about effectiveness and safety are a greater impediment than treatment-related barriers (Vogt, Hall et al. 2008). Little attention, however, has been given to how and why smokers quit unassisted. If we can explain how the process of unassisted quitting comes about and what it is about unassisted quitting that appeals to smokers, we may be better placed to support all smokers to quit, whether or not they wish to use assistance.

We conducted a qualitative study to understand why half to two-thirds of smokers choose to quit unassisted rather than use smoking-cessation assistance. Smoking-cessation researchers have highlighted the importance of gaining the smokers’ perspective (DiClemente, Delahanty et al. 2010, Orleans, Mabry et al. 2010) and suggested qualitative research might provide the means of doing so (Cook-Shimanek, Burns et al. 2013). Although a number of qualitative studies have examined non-use of assistance in at-risk or disadvantaged subpopulations (Kishchuk, Tremblay et al. 2004, Bryant, Bonevski et al. 2011, Hansen and Nelson 2011), only a few have looked at smokers in general. Few studies have examined explicit self-reported reasons of why smokers do not use NRT; to our knowledge, none has examined explicit, self-reported reasons of why smokers do not use prescription smoking-cessation medication.

The two research questions guiding the study were what does quitting unassisted mean to smokers? And what factors influence smokers’ decisions to quit unassisted?

Results

Our central analytical focus was the original, previously unreported categories in our analysis. When grouped, these suggested four new processes that could help explain unassisted quitting:

- Prioritising lay knowledge.

- Evaluating assistance against unassisted quitting.

- Believing quitting is their personal responsibility.

- Perceiving quitting unassisted to be the “right” or “better” choice.

The four analytical categories that explain the process and meaning of quitting unassisted, with illustrative quotes from the interviews, are shown in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 The four analytical categories that explain the process and meaning of quitting unassisted, with illustrative quotes

|

Category: Prioritising lay knowledge

|

|

Participant quotes “I’ve done this, I’ve done the gum before, it’s my turn to just do it by myself with common sense and willpower.” Female, 57 years old “I’ve known a couple of people around town that have tried to give up with patches and that and they’ve gone 3 or 4 weeks and they’ve started smoking again and all that.” Female, 52 years old “I’ve got friends that have used the patches and the gum a lot. They’ve been unsuccessful. They’ve done the gum and the patches, I don’t know how many times. They’ve spent so much money on them, and they just cannot make it work.” Female, 31 years old “Well [assistance] hadn’t worked in the past and I didn’t think – I’d come to the realisation that it was just in the mind, it was just a matter of willpower, it was just a matter of saying no and sticking to it.” Male, 59 years old |

|

Category: Evaluating assistance against unassisted quitting

|

|

Participant quotes “It was a big thing that if I’m going to save money by not smoking then why should I spend money on not smoking.” Male, 45 years old “The cigarettes, that’s the fun. Why would you spend $20 on non-fun?” Female, 34 years old “I found [NRT] expensive. I thought that if you’re going to get nicotine anyway at least there should be some positive reason for it.” Female, 56 years old “If I’m going to quit smoking I’m going to do it cold turkey and get it over and done with.” Female, 52 years old “I went to the GP and he said oh, you need to continue to smoke though for a couple of – what was it? It is a week? I was like oh no, but I want to stop now.” Female, 34 years old “It’s too much of a hassle . . . You’ve got to go out and buy the thing. You’ve got to stick it on or chew it or unwrap it.” Male, 61 years old |

|

Category: Believing quitting is their personal responsibility

|

|

Participant quotes “It’s my problem. Not problem, I think that’s a bad choice of words, but I was the one smoking.” Male, 28 years old “That’s so important that you don’t make an issue out of it. It is a personal – you’re right. You are so right. It is a personal thing.” Male, 61 years old “Yeah, okay, I screwed up, I smoked for years, I really need to do something about this and cope with it.” Female, 57 years old “I’m not much of someone to go to a doctor unless there was, unless I thought there was a serious problem with myself I don’t normally go to a doctor.” Male, 45 years old “I’m independent and I’m stubborn and that’s the only way that I knew how to do it. I wasn’t going to – I’m not a person to ask for help. So I don’t think I would have asked for help to quit smoking.” Female, 31 years old “OK I did the Champix, I stopped for maybe – I can’t remember if it was two or three months – but like it didn’t work because it actually, the change sort of wasn’t from within,” Female, 56 years old “I think quitting cold turkey, you’re going to have more chance of actually [staying] a non-smoker, if you quit cold turkey . . . because I think that you need that willpower to stay motivated to not smoke.” Female, 31 years old “Because in the grand scheme of things, it’s always your willpower that’s going to stop you. So you might be able to use other methods to help you quit smoking, but six months down the track, you need to have that willpower to stop you doing that again.” Female, 31 years old “I feel a sense of accomplishment in knowing that I did it cold turkey. Knowing that I didn’t have to go to other means to do it. That I was able to use my willpower.” Female, 31 years old |

|

Category: Perceiving quitting unassisted to be the “right” or “better” choice

|

|

Participant quotes “I think I just didn’t want to [use assistance], I just felt that for me to do it properly I actually had to be able to do it myself.” Female, 50 years old “[Taking medication] had crossed my mind, but I’m a fairly stubborn person I suppose. I don’t really – I believe that I should be able to do it myself, without those sorts of things.” Male, 31 years old “I think that if you’re truly committed you don’t need anything.” Female, 56 years old |

Prioritising lay knowledge

Many participants expressed views about assistance that were at odds with accepted knowledge in smoking cessation on the effectiveness, side effects and long-term safety of assistance. These “misperceptions” about assistance appear to arise because participants’ personal experiences and lay knowledge of assistance do not tally with what they have been told about assistance by their GP, pharmacist or through direct-to-consumer marketing of NRT by pharmaceutical companies. The gulf between what smokers have personally experienced or heard from others, and what health professionals are telling them was particularly evident in participants’ talk of unmet expectations of what assistance could realistically do for them. For many, the experience of using assistance had not been as expected, including not being as effective as they had believed it would be.

Participants talked of the importance of shared narratives of assistance that were predominantly negative and shared narratives of quitting unassisted that were predominantly positive. Shared stories of assistance – both personal and second-hand – were stories of failure to quit, and of unpleasant and sometimes serious side effects. In contrast, talk about quitting unassisted often featured family and friends who had managed to quit successfully on their own.

In order to resolve the tension between what is going on in “their world” and what the professional medical and healthcare worlds are endorsing, participants prioritised what they knew: either directly from their own experiences or indirectly from “trusted” sources. As a consequence, participants appeared to discount professional advice in favour of their own first-hand quitting experiences and the collective narratives of quitting successes and failures that circulated in their social groups. This lay knowledge-making based on personal and collective experiences appears to be a powerful force at play in smokers’ decisions about quitting.

Evaluating assistance against unassisted quitting

On the whole, participants did not seem to be quitting unassisted because of a lack of awareness or knowledge about the assistance available to them. Instead participants appeared to have engaged in an evaluation of the perceived costs and benefits of using assistance compared with the costs and benefits of quitting unassisted. Factors in this cost–benefit balance related primarily to the perceived convenience of unassisted quitting (in terms of time to being “quit” and the effort required to make the quit attempt happen) and the importance of short-term financial savings. These arguments were sometimes explicit and sometimes implicit.

Participants talked about wanting to quit now, immediately. NRT and smoking-cessation medication both involve a treatment period in which the smoker is still a smoker: they cannot yet call themselves a “non-smoker”. In their opinion, use of assistance essentially delays their progression to being totally quit. In contrast, going “cold turkey” provides an immediate satisfaction and instant non-smoker status. There often appeared to be a sense of urgency or a need for an immediate and complete change of status in those who opted to quit unassisted.

Using assistance was also associated with an investment of practical and logistical effort. Assistance required the adoption of new – but temporary – routines and habits. It was a middle ground or halfway house through which the smoker would have to pass. They would have to complete this “assistance” phase before being able to adopt yet another set of routines and habits to become nicotine free or drug free. These temporary routines associated with assistance included obtaining or purchasing assistance, carrying it around and remembering to use it. For some, this temporary, additional set of routines appeared simply too complex, too bothersome and too high a price to pay in terms of the inconvenience generated.

For a number of participants, spending money to quit, especially when quitting was motivated by a desire to save money, appeared counter-intuitive. For such participants, thoughts were focused on the here and now, on the short-term rather than long-term savings. Few participants appeared to regard money spent on assistance as a long-term investment in future financial savings. As a consequence, using assistance to quit was viewed as a barrier to maximising potential savings while quitting. For NRT specifically, this balancing of the pros and cons extended beyond the financial cost of cigarettes versus cost of NRT to the perceived pleasure that the financial spend was likely to provide. Spending $20 on cigarettes was reasonable because it would deliver pleasure; spending $20 on something that was going to make you miserable was not. An unwillingness to spend on NRT also appeared related to an inability to reconcile nicotine’s dual role as part of the problem and the solution, and to fears of becoming addicted to NRT gums, patches or inhalers.

Believing quitting is their personal responsibility

Quitting appeared to be an intensely individual experience and one that the smoker believed only they could take charge of. Ultimately quitting was something they had to face themselves. Many participants seemed to have reached a point where they regarded smoking to be their problem and quitting to be their personal responsibility. Quitting was, therefore, not necessarily something that could be helped or facilitated by external support (be it from family, friends or health professionals).

Participants often talked about being the person best placed to know why they smoked, why they wanted to quit, and what was likely to work for them. To these participants, external help or assistance was unlikely to be useful or necessary. For many this appeared to be because they had previous experience of unsuccessful assisted quit attempts (with, for example, OTC NRT, prescription NRT, smoking-cessation medications or behavioural support) and had learnt that for them, assistance was unhelpful or solved only part of the problem. Conversely, other participants had not previously used professional or pharmacological support to quit and therefore did not see the need to do so now. Still others simply did not equate smoking with being ill, or regard smoking and quitting as medical conditions: this meant medical support was not appropriate and little benefit would be gained from involving a GP in the quit attempt. Several participants implied that a GP would be able to offer only generic or lay quitting advice that was unlikely to be relevant to them personally: in other words, from the participant’s perspective, the GP could add little to the participant’s own personal store of quitting experiences.

A number of participants also appeared to have an issue with adopting a substitute behaviour (i.e. NRT or smoking-cessation medication). To these participants, the use of NRT or drugs meant that they were still dependent on nicotine or another substance to deal with their need for nicotine. If they really wanted to quit and to quit for good, they needed to take that step themselves, which to them essentially precluded the use of assistance and in particular, NRT.

Perceiving quitting unassisted to be the “right” or “better” choice

In contrast to the dominant medical and health promotion discourse about quitting unassisted being undesirable or even foolhardy, many participants saw quitting unassisted as the “right” or “better” way to quit. This belief appeared to be closely associated with what participants referred to as “being serious” about quitting. It appears that underlying these beliefs may be a set of values that the participant and perhaps also Australian society, as a whole, endorses.

Participants talked, either explicitly or implicitly, about the values that were important to them in relation to their quit attempt: independence, strength, autonomy, self-control and self-reliance. These values are, broadly speaking, also reflective of values central in many western societies and cultures. It seems likely that these broadly held values were influential in shaping participants’ beliefs about quitting unassisted being the right or better choice and the belief that quitting was “up to me”. Quitting unassisted allowed the participant to realise a need to feel independent, in control and autonomous, something that they would not necessarily have felt if they had used assistance. Some participants even suggested that seeking help from a GP or another source such as a quitline would be tantamount to admitting failure. The independent nature of their quit attempt was seen as an important contributor to the success of that attempt.

In summary, many participants believed they had achieved something of value by quitting unassisted, and appeared to take this achievement as an indicator of the strength of their moral character. In this context, quitting unassisted was presented as a morally superior option; quitting unassisted was evidence of personal virtue. It is important to note, however, that this was rarely used as a measure of the moral worth of others. Participants rarely suggested that other smokers who used assistance to quit were morally inferior. Rather, they presented their final, unassisted quit attempt as evidence that their personal virtue had increased over time, thus bolstering their own sense of identity and self-worth.

Discussion

In this community sample of ex-smokers who had quit on their own without consulting their GP or using smoking-cessation assistance, issues of cost and access to assistance, misperceptions relating to the effectiveness and safety of pharmacotherapy, and confidence in their ability to quit on their own affected their decision to quit unassisted. This was consistent with earlier quantitative and qualitative research. However, we found that the influences on non-use of assistance were more complex, involving careful judgements about the value of knowledge, the value of different quitting strategies, the importance of taking personal responsibility and the moral significance of quitting alone. Future efforts to improve uptake of assistance may need to take some of these influences into consideration.

In an effort to understand what appears to be conflicting advice about quitting and how to quit successfully, participants appear to fall back on trusting their intuition or common sense, giving preference to their personal and shared knowledge of quitting over professional or theoretical knowledge. Lay knowledge (or lay epidemiology) has previously been used to understand how health inequalities develop in smokers (Graham 1994, Lawlor, Frankel et al. 2003, Graham 2009), to inform health promotion practices in smoking cessation (Springett, Owens et al. 2007) and to explain the range of self-exempting beliefs used by smokers to avoid quitting (Oakes, Chapman et al. 2004). Our study is the first to demonstrate how lay knowledge influences non-use of assistance when attempting to quit smoking.

Participants who quit on their own often appeared reluctant to consult their GP, primarily because they did not view smoking or quitting as an illness, reflecting what others have also reported (Levinson, Borrayo et al. 2006, Fu, Burgess et al. 2007). Our analyses show that this reluctance to consult a GP may also be because smokers perceive the GP has little to offer beyond the smoker’s own lay knowledge, reflecting what others have recently reported for smoking cessation consultations in general practice in the UK (Pilnick and Coleman 2010). This reluctance to consult a GP may be reinforced if the smoker is hesitant about using pharmacotherapy or if they believe smoking is not a “doctorable” condition. Doctorable is a term coined by Heritage and Robinson (Heritage and Robinson 2006) to explain the way in which patients in the USA account for their visits to primary care physicians and to demonstrate how patients orientate to a need to present their concerns as doctorable. Before visiting a physician, patients make a judgement as to whether they require medical help. They are aware that the physician will subsequently judge their judgement when they present at the surgery. It is conceivable that this need to present only when the individual perceives the condition to be doctorable could apply not just to smoking cessation, but to other difficult-to-change health behaviours such as losing weight or getting fit.

In addition to judgements relating to the value of lay knowledge, our study highlights how smokers make judgements about the value of different quitting strategies based on perceptions of time and effort required, convenience and cost. This process of evaluation has been reported for decisions related to the taking of other prescribed medications. Pound et al. reported that patients often weigh up the benefits of taking a medicine against the costs of doing so and are often driven by an overarching desire to minimise medicine intake (Pound, Britten et al. 2005). In the current study, this evaluation of different quitting strategies often resulted in the participant forming a negative opinion of assistance and, in particular, of NRT. Given nicotine’s complicated history and transformation from an addictive, toxic and potentially harmful drug to a medically useful drug it was not surprising that many participants found it difficult to reconcile nicotine’s portrayal as being part of the problem and a possible solution (Keane 2013), and as a result appeared to be resisting use of medications to assist them to quit.

Underneath the prioritising of lay knowledge and the evaluation of different quitting strategies were deep-rooted cultural values, such as independence, strength, self-reliance, self-control and autonomy, which influenced participants’ views on assisted and unassisted quitting. Lay knowledge in combination with these multilayered influences led many participants to believe that quitting unassisted was the “right” or “better” way to quit, that the participant was personally responsible for their quitting and that quitting unassisted was a prerequisite for “being serious” about quitting. This key concept, being serious, is one we believe is critically important to Australian smokers and one we are exploring further in our ongoing research.

It should be noted that this study included only successful ex-smokers (quit for at least six months). Given that these individuals were interviewed in the context of a successful quit attempt, attribution theory (Weiner 1985) might provide some insight into the emergence of independence, strength, self-control and personal virtue as components of the successful unassisted quit attempt in these interviews. Attribution theory suggests a self-serving bias in attributions such that success is attributed to internal factors (such as personal virtue), and failure to external or situational factors. It might be informative to conduct some research with smokers who tried to quit on their own and failed, as well as with ex-smokers who successfully quit with assistance to explore whether concepts relating to external or internal attributions emerge for these different groups of quitters.

Implications and future research

A proportion of smokers is unlikely to choose to use assistance to quit smoking or is reluctant to do so. Too much focus on pharmacological assistance may fail this group. It may be a more productive and a potentially more patient-centred approach to acknowledge that for these smokers quitting unassisted is a valid and potentially effective option.

Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines prioritise results from randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses of RCTs. As a consequence, current smoking-cessation guidelines in the UK (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2018), USA (Krist, Davidson et al. 2021) and Australia (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2021) position pharmacotherapy as first-line therapy for those dependent on nicotine (>10 cigarettes per day). A range of government policies ensures pharmacotherapy is free or heavily subsidised, available on prescription and/or OTC, and that smokers have access to widely promoted and free quitline advice and support, and/or dedicated stop-smoking services.

As discussed in Chapter 2, RCTs are designed to evaluate the efficacy of interventions, such as medications, in carefully controlled study populations; they cannot capture and often seek to eliminate the complexities associated with patients’ lived experiences. This complexity may, however, be of relevance when making decisions about how to manage patients with complicated health-related behaviours, such as smoking. By retaining and examining some of the complexity surrounding quitting smoking, we have highlighted how participants’ beliefs, values and preferences can influence the decision to quit unassisted. Previous research into patient-centred care has also identified that respect for a patient’s beliefs and values (McCormack and McCance 2006), needs and preferences, (Laine and Davidoff 1996), and knowledge and experience (Byrne and Long 1976) are central to delivering care that is tailored to the needs of the individual patient. Accordingly, patient-centred care for smokers may include recognising and respecting smokers’ reasons for declining assistance, validating and approving their choices, and modifying brief interventions to support their preference for unassisted quitting, where preferred.

Healthcare policy does not operate in a vacuum. As our study indicates, success of any given policy is critically dependent on the broader social and cultural context. This is especially true for tobacco control given the influence of key stakeholders such as the tobacco industry. Recent research highlights how the tobacco industry capitalised on the powerful notion of personal responsibility to frame tobacco problems as a matter for individuals to solve (Mejia, Dorfman et al. 2014). To our knowledge, our analysis is the first to indicate smokers do indeed feel personally responsible for quitting. Smokers’ beliefs about quitting have been heavily influenced by social and cultural ideals, some of which are highly likely to have been shaped by the tobacco industry’s individual choice rhetoric. The complexity of how such rhetoric has influenced smokers has to date been unexplored.

The value placed on lay knowledge and on different quitting strategies by participants indicates that GPs, health promotion practitioners and pharmaceutical companies may be advised to be mindful of the consequences of overselling assistance and potentially unrealistically raising smokers’ outcome expectations, further fuelling the apparent gulf between lay experiences and expert-derived knowledge. The low absolute efficacy rates of NRT and stop-smoking medications create a challenge: is it possible to communicate about these products without disheartening smokers or making promises that may be difficult to deliver?

Cultural values are likely to play a role in the choice to use assistance or not, and future research should explore these issues in other cultures. It would be useful to replicate this study in other cultural contexts and in countries less advanced in tobacco control to determine whether the study findings are applicable across countries, cultural dimensions and stages of the tobacco epidemic.

For those patients who do seek medical advice, GPs may need to be cognisant of the role of lay knowledge and the patient’s evaluation of different quitting strategies when counselling and advising about quitting smoking. The challenge will be to support those smokers who wish to quit unassisted while avoiding stigmatisation of those smokers who want or need assistance to quit.

Conclusion

A smoker’s reluctance to use assistance to quit may sometimes be difficult to understand. Through this empirical work we are now able to suggest some explanations for this behaviour.

The reasons for smokers’ rejection of the conventional medical model for smoking cessation are complex and go beyond the modifiable or correctable issues relating to misperceptions or treatment barriers. Lay knowledge and contextual factors are critically important to a smoker’s decision to seek or resist assistance to quit. Smokers prioritise lay knowledge, evaluate assistance against unassisted quitting, believe quitting is their personal responsibility and perceive quitting unassisted to be the right or better option.