3

Quitting unassisted: before and after “evidence-based” methods

Tweet from New Zealand vaping activist to Australian Senator Matt Canavan (pro-vaping member of the 2020 Senate Select Committee on Tobacco Harm Reduction), 13 November 2020. Source: https://twitter.com/ElianaRubashkyn/status/1327047735586021380

Most of the 20th century saw astronomical growth in smoking in many nations. This was almost entirely ignited by the mechanisation of cigarette production, which commenced from 1880. This dramatically reduced labour costs in what had hitherto been a highly labour-intensive industry involving the hand-rolling of cigarettes. Prior to mechanisation, an experienced worker in a factory could make about 240 cigarettes per hour. The first mechanised cigarette-rolling machine could make 12,000 an hour. Today’s Philip Morris International machines churn out 1.2 million cigarettes an hour (Philip Morris International 2021). Mechanisation saw the price of cigarettes fall rapidly, making them affordable to even those on meagre incomes. The rise of the advertising industry in the 1920s (Ewen 1976) enabled smoking to be invested with a host of meanings that saw the wholesale normalisation and glamourisation of smoking, first among men and later among women (Amos and Haglund 2000).

In these early decades of the 20th century, fragmentary references to advice and efforts to help people stop smoking can be found. But overwhelmingly, this period was a story of unstoppable smoking uptake, and the untrammelled promotion of smoking. On my bookshelves are numerous historical books about smoking, often given to me as gifts by graduating students who found them in second-hand bookshops and knew my love of history. These extol the delights of smoking (MacKenzie 1957), fulminate about the smoking “scourge”, provide advice about how to rid oneself of this vice and mention early “cures”.

Arthur King published a small book in 1913, The cigarette habit: a scientific cure (King 1913). The book commences with case studies on those who found quitting smoking agonisingly difficult. King openly declares smoking is an addiction for many, after having come to this realisation about himself (“If I couldn’t quit smoking, maybe I was addicted to smoking, just as much as the morphine user is addicted, or the chronic alcoholic”). Most of the book is then devoted to explaining his cure, which he explains is based on “a classic axiom in drug-addiction treatment that it takes exactly twenty-one days to get the patient ‘off the hook’”.

His “cure” involved many of the standard folk wisdoms that have persisted for over a hundred years in tips that are still often passed to smokers about how to overcome cravings when quitting. King gave lots of advice about drinking fruit juice and water, cleaning the teeth, deliberately banishing thoughts about smoking, going for walks, writing out long lists about all the pluses of quitting and so on. But there are also early examples of self-medication, with smokers advised to stock up on caffeine tablets, antihistamines, and Boots’ (the British pharmacy chain) “Anti-Smoking Tablets”. Addicted smokers were urged to obtain five 5 mg dexedrine (amphetamine) tablets, and 10 half-gram phenobarbitone tablets (used to control epilepsy) to assist them with quitting.

Allan Brandt’s epic history of the rise and decline of smoking in the 20th century, The cigarette century (Brandt 2007) notes that in the first decades, anti-smoking views were found among those who saw smoking as a vice and “a profound moral failing and a sign of other social and characterological flaws”. Youths who smoked were commonly believed to be “stunted in growth and under-developed in mind”, generating much tut-tutting and parliamentary activity designed to keep youth away from tobacco. But there are few accounts of efforts to promote quitting. Brandt describes (Brandt 2007, 48–9) the establishment of stop-smoking clinics in Los Angeles, Chicago, Hoboken and “many cities” that drew “a veritable mob” of smokers looking for treatments. These treatments included mouthwashes and swabs sometimes using silver nitrate designed to make the taste of smoking unpalatable.

A 1923 book published in Melbourne, Secret recipes (Holmes 1923), believed to be written by World War I medical officer Thomas J. Holmes, described an “anti-smoking mixture” where 36 grains of silver nitrate were mixed with 475 ml of water for use as an aversive mouthwash after meals. The book cautioned, “Do not swallow any of the mixture. It is almost tasteless, but is instantaneous in removing the desire to smoke”. A medical advice column in the Detroit News from 1949 also recommended the same path, cautioning that silver nitrate “is sometimes used to mark the skin”. It had often been used as a wart corrosive. The column continued, “One trying to quit smoking should exclude from his diet meat soups, broths or extracts, highly seasoned sauces or dishes. He or she should eat freely of apples, baked with meals or raw the first thing for breakfast and the last thing at night” (Brady 1949).

Such folksy hokum persisted for decades in leaflets and how-to-quit tip sheets often provided by health departments. For example, this Ugandan advice from 2004 counselled: “Nature has the remedy. Stretch out your arm and pick up a carrot. Chew it and smile. Within a few hours, all your distress will be gone. This orange root has large amounts of charm that is appropriate for those who wish to give up smoking. It accelerates the elimination of nicotine and its content of carotene reconstructs the mucosal membrane of the respiratory system that might have been damaged by smoking” (Nadawula 2004).

As I’ll discuss later in this chapter, the advent of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) from the late 1980s and its 30 years of subsequent widespread use marked the first time that attempts at stopping smoking often involved large-scale efforts to promote using medication to assist quitting. Prior to NRT, those who “took something” to help them quit used preparations that made money for the patent medicine spruikers selling them, but as far as I can tell from the thin historical record, none of the snake oils touted by their commercial and moral evangelists ever saw them in widespread use. But as we will now see, very large numbers of smokers began quitting when news reports of the first serious case-control studies started being published from the early 1950s.

In the introduction to this book, I noted that the publication of the seminal British and US case-control studies on smoking and lung cancer in the early 1950s saw a rise in news and commentary about smoking. This was greatly amplified in the early 1960s with the publication of the summary reports on smoking and health by the Royal College of Physicians of London (1962) and the United States Surgeon General (1964).

In 1955, just five years after Wynder and Graham’s historic study of smokers and lung cancer was published in JAMA (Wynder and Graham 1950) and received widespread news publicity, 7.7 million Americans aged 13 and over (6.4% of the population) were former smokers. Ten years later in 1965, following further widespread publicity surrounding the 1964 US Surgeon General’s Report, Smoking and Health, the number of ex-smokers had ballooned to 19.2 million (13.5% of the population aged 13 and over were ex-smokers). At the Second World Conference on Smoking and Health held in London in 1971, Daniel Horn, the director of the US National Clearinghouse for Smoking and Health, presented results of a cohort of 2,000 US smokers interviewed in 1966 and then again in 1970. Twenty-six percent of men and 17% of women had stopped smoking for a year or more in this time. Horn noted that 99% had done so without any formal help: “The level of change in smoking habits in the United States has become quite massive and I regard it as a change in health behaviour that is largely dependent on individual decision” (Horn 1972).

By 1975, 32.6 million Americans (19.4%) had stopped smoking (Horn 1978). Quitting smoking had become a major phenomenon. In 1979, the then director of the US Office on Smoking and Health noted in a National Institute on Drug Abuse Monograph Series, “In the past 15 years, 30 million smokers have quit the habit, almost all of them on their own” (Krasnegor 1979). Many of these quitters had been very heavy smokers. The same monograph also stated that “longitudinal studies should be designed to investigate the natural history of spontaneous quitters … We know virtually nothing about such people or their success at achieving and maintaining abstinence” (Krasnegor 1979). In 2022, we have much improved on that situation, but the overwhelming majority of research on cessation has always focused on the “tail” of assisted cessation, not on the “dog” of unassisted quitting.

This major and enduring social and public health phenomenon of quitting smoking largely escaped the interest of researchers. There were very few research papers published in the 1960s and early 1970s about quitting. An early example by Graham and Gibson (Graham and Gibson 1971) reported on 382 smokers who had given up for at least a week. One hundred and twelve were classified as “successes” and the rest “recidivists”. Of the successes, 89% had apparently stopped completely on their first attempt, with the others having up to four attempts before succeeding.

How did they do it? The authors asked about aids used, which in those days appeared to consist of either eating sweets or chewing gum (the wisdom of the day seemed to be that smokers needed to have something going into their mouths instead of a cigarette), 48% of the successes had used such aids compared with 70% of the recidivists. The authors noted that “various authorities and bodies … issued statements condemning smoking, and data were published in newspapers from additional studies of prospective design”.

A 1972 US paper reported on a cohort of smokers interviewed in 1966 and again 1968 (Eisenger 1972). Fifteen percent reported having quit in the two years between the interviews. The author attributed this to “expanded efforts by the US Public Health Service, American Cancer Society and others to inform the public of the health hazards of smoking”. Again, this paper contained no information on how ex-smokers had quit. This might suggest that in those days, the question may have never occurred to researchers: it was obvious that if smokers were quitting in large numbers, they were doing it unaided.

Ken Warner’s 1977 paper in the American Journal of Public Health (Warner 1977) was probably the first time a helicopter view had been taken of population trends in per capita cigarette consumption across an early era in tobacco control. Using US data, he estimated:

While individual anti-smoking “events” such as the Surgeon General’s Report, appear to have had a transitory and relatively small impact on cigarette smoking, the evidence from this study indicates that the cumulative effect of years of anti-smoking publicity has been substantial. The analysis suggests that per capita consumption would have been one-fifth to one-third larger than it actually is, had the years of anti-smoking publicity never materialized. Increases in per capita cigarette smoking from 1970 through 1973 have been cited as evidence that the campaign has been ineffective; yet those increases totalled only 40 percent of what might have been anticipated in the aftermath of the TV-radio ads had there been no continuing effects of the campaign. Furthermore, in 1973 through 1975, abstracting from the effects of the campaign, conditions were conducive to the largest increases in consumption during the post-Report years – relative cigarette prices were falling for the first time; predicted consumption increased 16 percent during those three years. Yet following a 2 percent increase in 1973, actual consumption levelled out in 1974 and declined slightly in 1975.

Warner focused on the impact of mandated anti-smoking advertising that was broadcast across the US following a ruling under the Fairness Doctrine between 1968 and 1974. Following advocacy by pioneering US tobacco control advocate John Banzhaf III, and the Federal Communications Commission, the broadcast Fairness Doctrine which required television and radio licensees to “operate in the public interest and to afford reasonable opportunity for the discussion of conflicting views on issues of public importance” was expanded from the discussion of political issues to also include the smoking and health debate. With the tobacco industry spending millions on broadcast advertising of tobacco products, the advocates succeeded in requiring anti-smoking advertisements to be broadcast between 1968 and 1970. Health groups received US$75 million each year to pay radio and television stations to run the ads. For example, the American Lung Association delivered 1,269 ads between 1969 and 1970 with this funding (Warner 1977).

Warner calculated that publicity arising from “the smoking-health scares of the early 1950s reduced consumption by about 3 percent in 1953 and about 8 percent the following year, with the effect trailing off throughout the 1950s. In 1964, the Surgeon General’s Report decreased per capita consumption by almost 5 percent. The anti-smoking TV and radio ads reduced consumption an average of better than 4 percent each of the three years they were aired under the Fairness Doctrine”.

So effective was the impact of this advertising that the tobacco industry agreed voluntarily to stop all tobacco advertising in broadcast media in a bargaining deal to end funding for the anti-smoking advertisements. This took effect from 1 January 1971. While the American Lung Association had paid via Fairness Doctrine funding for 1,269 TV ads from 1969 to 1970, between 1971 and 1974 it ran only 569 ads when it had to finance the cost itself after the Fairness Doctrine funding tap was turned off. Gideon Doron’s 1979 book The smoking paradox documented this early episode in tobacco control history (Doron 1979).

Neither Warner’s nor Doron’s analyses made any mention of the reductions in smoking they reported as being in any way attributable to assisted smoking cessation activity, but to reductions stimulated by mass-reach anti-smoking messaging. The only tobacco control policy in place for around a decade from the mid-1960s in a tiny handful of vanguard nations was tepid, general and very small health warnings on cigarette packs. The main drivers of all the quitting described above had been news publicity about the dangers of smoking. This shaped public views about the wisdom of continuing to smoke, and the US 1969–74 period where mass-reach anti-smoking advertising was broadcast in the USA at an average of only 306 screened ads a year, a tiny amount by the levels of major campaigns in later years (Dunlop, Cotter et al. 2013).

Of huge importance is Warner’s comment above that “individual anti-smoking ‘events’ such as the Surgeon General’s Report, appear to have had a transitory and relatively small impact on cigarette smoking, the evidence from this study indicates that the cumulative effect of years of anti-smoking publicity has been substantial”. It should counsel us to be wary of being what renowned Australian epidemiologist A.J (Tony) McMichael (1942–2014) described as “prisoners of the proximate” in our search for causal factors that are responsible for changing highly complex phenomena like smoking throughout a population. Rather, we need to understand by shifting to a more ecological understanding of the complexity of change that large-scale social, attitudinal and behavioural change percolates for years, reflecting the interplay of both proximal and distal factors (McMichael 1999) I will return to this issue in Chapter 8.

In 1990, Michael Fiore and colleagues published findings from the 1986 US national Adult Use of Tobacco Survey (Fiore, Novotny et al. 1990). They set their report against the dramatic fall in smoking prevalence from 40% in 1965 to 29% in 1987. Yet again, their central finding was that smokers who quit overwhelmingly did so unaided:

About 90% of successful quitters and 80% of unsuccessful quitters used individual methods of smoking cessation rather than organized programs. Most of these smokers who quit on their own used a “cold turkey” approach … Daily cigarette consumption, however, did not predict whether persons would succeed or fail during their attempts to quit smoking. Rather, the cessation method used was the strongest predictor of success. Among smokers who had attempted cessation within the previous 10 years, 47.5% of persons who tried to quit on their own were successful whereas only 23.6% of persons who used cessation programs succeeded.

As I discussed in Chapter 2, in later years commentators noting the frequent finding in population surveys that smokers quitting unassisted in real-world conditions succeeded more than those using assistance explained this as “indication bias”. They argued that those who were heavier, more nicotine-addicted smokers were going to find it harder to quit and would gravitate toward using aids and professional help. They were therefore biased as being a group who were likely to struggle more to quit than those who used aids. They argued that no one should be surprised that those who believed they could quit without help (because they were allegedly mostly less addicted, lighter smokers) were more likely to succeed in quitting than those who were more heavily addicted.

So the Fiore group’s findings summarised above are rather awkward for this explanation: they found no difference in quitting when comparing higher with low daily consumption – a key marker of nicotine dependency. It was quitting unassisted – regardless of daily smoking rate – that predicted success.

A systematic review of 26 studies which had reported on rates of cessation attempts from nine nations published between 1986 and 2010 found that all but two reported that smokers attempting to quit unassisted were in the majority (Edwards, Bondy et al. 2014). Heterogeneity in the papers about key issues like the duration of quitting precluded any pooled estimate of how many of those attempting to quit try to do so unassisted, but the range across the 26 papers was between 40.6% and 95.3%. Only some of the 26 studies provided data on whether their final successful attempt was unassisted (many quitters try a variety of ways to quit across a given year).

Of four that reported success rates differentiating assisted from unassisted, for unassisted these ranged from 79.5% in 1990 (Fiore, Novotny et al. 1990), 45.4% in 1994 (Lennox and Taylor 1994), 72.1% in 2007 (Lee and Kahende 2007), 66.9% prior to 1983, 57.4% in 1984–95 and 43.9% in 1996–97 (Yeomans, Payne et al. 2011). Each of these rates would be regarded as highly impressive if reported for any method of smoking cessation, particularly if the cessation was long-term.

We are hugely amnesic in forgetting or ignoring what happened in the days when what are today routinely called “evidence-based” treatments were unavailable. In the 1960s to late 1980s, there was nothing remotely approximating today’s suite of tobacco control policies that have slowly driven down smoking in countries like Australia from 41% of men and 29% of women in 1975 (Gray and Hill 1975) to only 11% of those aged 14 and over smoking daily today (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020e). In those days, there were no complete tobacco advertising bans, cigarettes were dirt cheap, there were few sustained (Lee and Kahende 2007) mass-reach anti-smoking campaigns, smoking was allowed almost everywhere and pack warnings, where they even existed, were tiny and timid (Chapman and Carter 2003). Yet hundreds of millions of smokers across the world were motivated to quit smoking without help, and a huge number did so permanently.

In looking to the future of smoking cessation we should not forget the often-repeated, important lessons from its past. But as we shall see in Chapter 5, drawing attention today to the enduring, heavy-lifting contribution of unassisted quitting to the ranks of ex-smokers has become something of a profanity in professional smoking-cessation circles, which are dominated by those determined to encourage smokers to do anything but try to quit on their own.

Enter Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) and prescribed medications

A search of the PubMed database of health and medical research shows the first paper published on gum containing nicotine for use in controlling smoking was published in 1973 (Brantmark, Ohlin et al. 1973). By the end of the 1970s, 15 papers had been published on the topic, and during the 1980s, turbo-charged growth saw another 293. Growing understanding of the effects of nicotine on the central nervous system, its addictiveness and on the potential for NRT to ease withdrawal prompted the widespread belief that cushioning withdrawal reactions by replacing nicotine in cigarettes with that in NRT would facilitate increased quitting. By the early 1990s, interventionists who focused on individualistic clinical models of smoking cessation were excited about what they saw as the first potentially mass-reach effective approach to cessation and were writing obituaries for face-to-face therapies:

What is required is a broader perspective and greater respect for the limited role of individual and even small group interventions. Over the past decade we have witnessed a sometimes grudging acknowledgement of and interest in the pharmacological aspects and addictive properties of tobacco (Lichtenstein and Glasgow 1992).

In Australia, NRT gum became prescribable by doctors from 1984, and patches from 1986. Both gum and patches were rescheduled by the Therapeutic Goods Administration in 1988 (2 mg gum) and 1997 (4 mg gum and patches), making them available over the counter (OTC) without a prescription. NRT products have been advertised directly to the public since 1998 and sold in supermarkets since 2005.

Two prescription-only quit-smoking medications, bupropion (marketed in different nations as Zyban™ or Wellbutrin™) and varenicline, also later became available. Bupropion, an anti-depressant which had been shown in clinical trials to be useful in smoking cessation, became available in the USA from 1985, and by 2021 remained the 27th most prescribed drug in the country (ClinCalc 2021) In Australia bupropion was subsidised under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme from 2001.

Varenicline (sold as Champix™ and Chantix™) is a nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor partial agonist. In the presence of nicotine, varenicline blocks nicotine’s ability to bind with these nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain, nullifying the effects of nicotine. Its availability commenced with releases in the USA and Europe in 2006 and in Australia in 2008 (Greenhalgh, Stillman et al. 2020). A meta-analysis found that the abstinence rate at 24 weeks or more for a 12-week course of varenicline plus counselling was more than twice that of counselling alone. Pooled data from three trials found that more people were abstinent from smoking at 12 months with varenicline than with bupropion (Stead, Perera et al. 2012).

By far the greatest potential for counselling in conjunction with the provision of varenicline is the brief advice typically offered by doctors, which accompanies prescription during a consultation. A Cochrane review concluded, “Simple advice has a small effect on cessation rates. Assuming an unassisted quit rate of 2 to 3%, a brief advice intervention can increase quitting by a further 1 to 3%. Additional components appear to have only a small effect, though there is a small additional benefit of more intensive interventions compared to very brief interventions” (Stead, Buitrago et al. 2013). So a “doubling of impact” from varenicline needs to be understood as a doubling of a modest effect. In Chapter 4, I look at the extent to which doctors ever offer smokers advice on how to quit.

During the 30-plus years in which these products have been available, the pharmaceutical industry has poured huge resources into both physician-directed and general public-directed promotions. For example, in 2008 total promotional expenditure for the market leader Nicorette™ in Australia was $3.108 million, with Nicabate™ spending $4.603 million. Champix™ (varenicline) spent $4.555 million. The USA and New Zealand are the only two OECD nations which allow direct-to-the-public advertising of prescription-only medications. In Australia, pharmaceutical companies selling prescribed smoking cessation drugs have circumvented this by running advertising where the brand names are never mentioned but smokers are urged to “ask your doctor” about a drug that can help you quit.

The 2008 Champix™ launch saw over 100,000 visitors to the brand’s “Outsmart Cigarettes” website during the campaign period. It encouraged 7% of all Australian smokers to make a quit attempt with Champix™, with 248,296 prescriptions being filled and $50,936,964 in sales occurring in its first year on the market. Champix™ became market leader within five months, doubling the size of the smoking cessation category (Australian Advertising Council 2009).

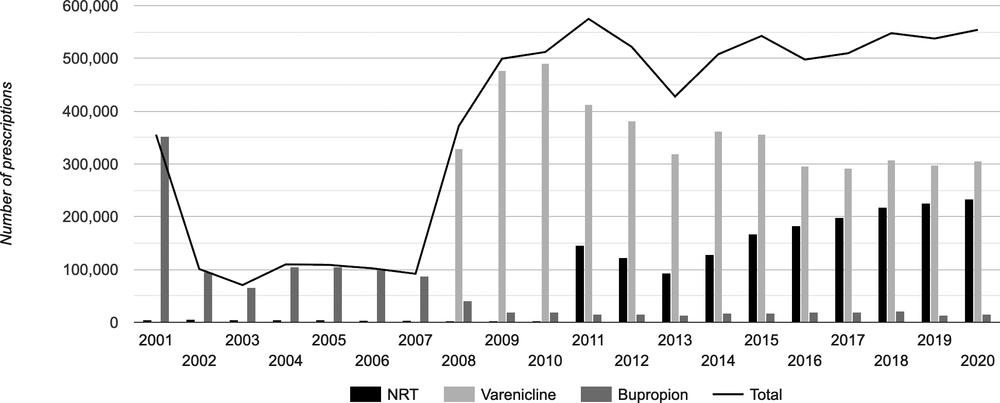

Figure 3.1 shows the volume of prescriptions for NRT, bupropion and varenicline in Australia from 2002 to 2020. Note that NRT can also be sold OTC, so the numbers shown are very conservative for its total use in Australia. From 2011, any smoker could obtain NRT via prescription at a subsidised price.

Between 2001 and 2020, 1.162 million scripts were issued for bupropion; between 2008 and 2020, 4.631 million for varenicline; and between 2011 and 2020, 1.792 million for NRT, all on top of unknown but certainly many millions of packs of OTC NRT. The number of smokers in Australia across this time fell from 3.6 million in 2001 to 2.9 million in 2019 despite population growth of 18.8% in that time (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020h).

Figure 3.1 Prescriptions in Australia for smoking-cessation medications 2001–20. Source: https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-7-cessation/7-16-pharmacotherapy

How has mass use of smoking-cessation medication affected cessation at the population level?

Given this fall, an obvious question to ask is, “What has been the impact of all this prescribing and sales of these so-called effective drugs on smoking cessation across the Australian population?”, always bearing in mind that there were many other policy factors designed to reduce smoking that were introduced during the same period. Particularly since 2008, in a smoking population of some 2.9 million (the 2019 figure) there has been a staggeringly high level of smoking-cessation pill swallowing, patch wearing and gum chewing among Australian smokers. With the Niagara of advertising promises of effectiveness cascading for years about these products, what has actually been the population impact? Two studies have examined this.

A 2008 examination of monthly data on Australian smoking prevalence from 1995 to 2006, which assessed the potential impact of televised anti-smoking advertising, cigarette price, sales of NRT and bupropion, and NRT advertising expenditure found that neither NRT or bupropion sales nor NRT advertising expenditure had any detectable impact on smoking prevalence across this 12-year period. Government anti-smoking campaign advertising and tobacco price did (Wakefield, Durkin et al. 2008).

The same research group updated their analysis in a second paper published in 2014 (Wakefield, Coomber et al. 2014), looking at the impact of increased tobacco taxes; strengthened smoke-free laws; increased monthly population exposure to televised tobacco-control mass-media campaigns and pharmaceutical company advertising for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), using gross television ratings points; monthly sales of NRT, bupropion and varenicline; and introduction of graphic health warnings on cigarette packs. They used Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) models to examine the influence of these interventions on smoking prevalence, and again found increased availability of these smoking cessation medications was not statistically associated with changes in smoking prevalence. They found that increased tobacco taxation, more comprehensive smoke-free laws and increased investment in mass-media campaigns played a substantial role in reducing smoking prevalence among Australian adults between 2001 and 2011.

These Australian findings echoed an earlier US analysis. A 2005 Annual Review of Public Health paper on the impact of NRT on smoking analysed national cigarette consumption and NRT sales from 1976 to 1998, and concluded that sales of NRT were associated with only a modest decrease in cigarette consumption immediately following the introduction of the prescription nicotine patch in 1992. However, no statistically significant effect was observed after 1996, when the patch and gum became available without prescription OTC, after which annual quit rates as well as age-specific quit ratios remained stable (Cummings and Hyland 2005).

What’s the upshot from RCTs and observational studies of NRT?

In the 48 years since the first paper on NRT appeared, an immense volume of research on these three drugs has been published, with some recent renewed attention to cysteine, an antioxidant (Syrjanen, Eronen et al. 2017). Over the years, many important reviews, meta-analyses and papers have looked at questions of whether smokers using NRT or prescribed smoking cessation medications have higher quit rates than those who try to quit without using these products. Here are a selection of some of the more important of these across the years.

In 2006, Etter and Stapleton published a meta-analysis of 12 RCTs comparing NRT with placebo (Etter and Stapleton 2006). They found that while NRT performed better than placebo, “the long-term benefit of NRT is modest” and that smokers might “require repeated episodes of treatment”.

In a 2011 paper, Hughes and colleagues reviewed non-RCT studies of NRT cessation outcomes reported in retrospective cohort studies of OTC NRT users versus non-users, as well as those comparing prescribed NRT with OTC NRT, including that given free to quitline callers (Hughes, Peters et al. 2011). They concluded that about half the studies “found statistically greater quitting among NRT users, and the most rigorous studies did not find greater quitting among users”. They suggested that indication bias (Shiffman, Brockwell et al. 2008) (see Chapter 2) plausibly explained these findings: those using NRT were more addicted smokers who would have had lower likelihood of quitting than those attempting to quit unaided.

The Cochrane Collaboration first reviewed NRT in 2004, with its most recent update published in 2018. Only RCTs were considered. The 2018 review looked at 133 RCTs with 64,640 participants and focused on the primary comparison between any type of NRT and a placebo or non‐NRT control group. People enrolled in the studies typically smoked at least 15 cigarettes a day at the start of the studies. The authors concluded:

There is high‐quality evidence that all of the licensed forms of NRT (gum, transdermal patch, nasal spray, inhalator and sublingual tablets/lozenges) can help people who make a quit attempt to increase their chances of successfully stopping smoking. NRTs increase the rate of quitting by 50% to 60%, regardless of setting, and further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of the effect. The relative effectiveness of NRT appears to be largely independent of the intensity of additional support provided to the individual. Provision of more intense levels of support, although beneficial in facilitating the likelihood of quitting, is not essential to the success of NRT (Hartmann-Boyce, Chepkin et al. 2018).

This resounding conclusion about the superiority of any form of NRT over placebo or any control group, especially in the context of the ongoing mass sales of NRT in nations like Australia, both OTC and via prescription on government price subsidy, invites important questions about why such widespread and enduring consumption of this effective NRT appears to have not been clearly mirrored in changes in national smoking prevalence.

A 2013 US national Gallup poll reported that only 8% of ex-smokers attributed their success to NRT patches, gum or prescribed drugs (Newport 2013). In contrast, 48% attributed their success to quitting “cold turkey” and 8% to willpower, commitment or “mind over matter”. Nearly 40 years earlier, a 1974 Gallup survey reported that most smokers would not attend formal cessation programs and preferred to quit on their own (Newport 2013).

In 2017 US researchers published results from two cohorts of smokers followed for a year between 2002 and 2003, and 2010 and 2011 (Leas, Pierce et al. 2018). The two population samples had many smokers who had tried to quit in the year prior to the study. These included those using smoking cessation drugs, and those not. The study found that in smokers trying to quit, there was no evidence that use of varenicline, bupropion or NRT increased the probability of smoking abstinence for 30 days or more when measured at one-year follow-up compared to those not using these drugs.

This study is of particular importance because the analysis undertaken sought to test whether indication bias (see Chapter 2) was responsible for the frequently observed outcome that unassisted quitters succeed more than assisted quitters because of confounding (i.e. those less likely to quit because of stronger addiction self-select to use medication far more than less addicted smokers). The authors in this study anticipated this issue and all smokers were assessed by what the study authors called a “propensity to quit” score (a score involving factors like smoking intensity, nicotine dependence, previous quit history, self-efficacy to quit, and whether they lived in a smoke-free home where quitting would likely be more supported).

In their analysis, those who tried to quit with drugs and those who didn’t were matched on this propensity to quit score confounder, so that “like could be compared with like” in the analysis. Using these matched samples to provide a balanced comparison, there was no evidence that those using any of the three drugs increased the probability of 30 days or more smoking abstinence at one-year follow-up.

The authors concluded, “The lack of effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids in increasing long-term cessation in population samples is not an artifact caused by confounded analyses.” They suggested a possible explanation of this was that counselling and support interventions often also provided in efficacy trials are rarely delivered in the general population.

Two back-to-back papers first published in the Tobacco Control journal in 2018 looked at (1) changes in 27 European countries in smoking prevalence and tobacco control policies between 2006 and 2014 (Feliu, Filippidis et al. 2019), and (2) changes in the use of smoking cessation assistance in the same nations between 2012 and 2017 (Filippidis, Laverty et al. 2019). In the paper looking at smoking prevalence and policies, countries with higher scores in the Tobacco Control Scale (a scale that enables ranking of nations on the extent to which they have implemented a range of tobacco control policies) (Joossens and Raw 2006) had lower smoking prevalence and higher quit ratios than those nations with low scores on the Tobacco Control Scale. The “quit ratio” is the proportion of ever smokers who have quit (so different from the prevalence of ex-smokers in a population).

One of the components that is scored in the Tobacco Control Scale is “treatment for dependent smokers” with a maximum possible score of 10/100 for that component of the scale. So while nations across Europe that were scoring high in the scale were enjoying lower smoking prevalence, what was happening to the use of assisted smoking cessation methods across time? The Filippidis et al. paper found that among current and former smokers, those who had ever attempted to quit without assistance increased from 70.3% (2012) to 74.8% (2017), while use of any pharmacotherapy fell from 14.6% to 11.1% and use of smoking cessation services (this included advice from a doctor and calling quitlines) also fell from 7.5% to 5%. E-cigarette use rose from 3.7% to 9.7%. These findings would have given little encouragement to advocates for proliferating assisted cessation across Europe.

In a 2018 paper using the US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study data (Hyland, Ambrose et al. 2017) between wave 1 (2013) and wave 2 (2015), the authors reported persistent abstinence (not using any tobacco product for more than 30 days) by different quit method used at last attempt (Benmarhnia, Pierce et al. 2018). In ascending order of worst to best quitting outcomes, the quitting outcomes were (1) using e-cigarettes: 5.6% (2) NRT: 6.1% (3) varenicline: 10.2% and (4) bupropion 10.3%. But the most successful all-tobacco quit rate was for “no aid used” (i.e. cold turkey or unassisted cessation) with 12.5%.

Moreover, when we multiply these quit rates by the numbers of smokers using each quit method, the yield of persistent quitters who quit unaided at two years was even starker (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Smokers with persistent abstinence (>30 days) from all tobacco (numbers) by quit method used among 3,093 smokers [numbers and (percentages)]. Note: Total row numbers add up to 3370 while the total shows 3093 because the reported use of products is not mutually exclusive. Some smokers report using more than one product to help them quit.

| Quit method | |

|---|---|

| E-cig user at Wave 1 (n=200) | 11.2 (3.8%) |

| E-cig user sometime after Wave 1 (n=569) | 21.1 (7.1%) |

| NRT (n=533) | 32.5 (10.9%) |

| Varenicline (n=156) | 15.9 (5.4%) |

| Bupropion (n=92) | 9.5 (3.2%) |

| No aid used (n=1820) | 227.5 (76.6%) |

| Total (n=3093) |

296.9 |

So in this major national cohort of US smokers, the much-maligned (see Chapter 5) and neglected unassisted cessation attempters quietly ploughed on, continuing their massive historical dominance of how most ex-smokers quit, contributing 1.5 times more quitters than all other methods combined, including those obtained via the much-vaunted new so-called disrupter, e-cigarettes (see Chapter 6). So not only did the supposed new heavyweight cessation champion, e-cigarettes, produce the lowest rate of persistent abstinence from all tobacco use after one year compared to all other quit methods, but their net contribution to population-wide tobacco abstinence was utterly dwarfed by all other methods (10.9% vs. 89.1%).

Australian data

In 2013–15, I was lead researcher on a three-year NHMRC grant researching unassisted smoking cessation in Australia. One of our first papers systematically reviewed all peer-reviewed research published between 2005 and 2012 about unassisted smoking cessation in Australia (Smith, Chapman et al. 2015).

We located 14 studies (11 quantitative and 3 qualitative) which reported on the number or proportion of smokers who quit unassisted. The 11 quantitative studies reported that between 54% and 78% of ex-smokers quit unassisted, and between 41% and 82% of current smokers had attempted to quit unassisted. Of the studies with representative rather than convenience samples, between 54% and 69% of ex-smokers quit unassisted and between 41% and 58% of current smokers had attempted to quit unassisted.

Two of the quantitative studies compared rates of successful cessation for smokers who used assisted and unassisted methods of quitting (Doran, Valenti et al. 2006, Kasza, Hyland et al. 2013). The Kasza et al. study found that smokers who used the NRT patch, varenicline or bupropion were more likely to maintain six-month abstinence from smoking than those who attempted to quit without medication. The odds ratios for the three medications compared to unassisted controls were 4.09, 5.84, and 3.94 respectively, which the authors noted were comparable to results from RCTs. However, this cohort study reported attrition rates of approximately 30% between surveys, with missing subjects being replenished. Attrition rates of over 20% are considered a serious threat to validity (Bankhead, Aronson et al. 2017).

Notwithstanding the different quit rates across the quit methods used, the net yield of quitting in this study was again higher for those using no medication (385) than for those using medication (326) because of the greater numbers who attempted to quit without medication.

The Australia-wide 2003–04 Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) study of patients attending general practices reported a success rate (the number of former smokers divided by the total number attempting to quit for each cessation method) for smokers who quit cold turkey (defined as “immediate cessation with no method of assistance”) of 40%, compared with 21% for bupropion and 20% for NRT for quit attempts since February 2001 (n=1030) (Doran, Valenti et al. 2006).

A 2011 study of recent quitters found two-thirds had used cold turkey; that it was used by a larger proportion of quitters who had been abstinent for more than six months; and that it was perceived as being more helpful than any other method (Hung, Dunlop et al. 2011).

An International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country study (which included an Australian arm) compared rates of successful cessation for individuals using or not using stop-smoking medications. Although the study did not differentiate between those quitting unassisted and those quitting with behavioural support, the results provide an indication of the success rate for unassisted cessation, given that the proportion of smokers who use behavioural assistance in Australia is very small (Cooper, Borland et al. 2011). The study reported that, of those who smoked 10-plus cigarettes per day and quit without medication, 14% were abstinent at six months, compared with smokers who quit with medication, of whom 16% were not smoking at six months. After controlling for differential recall bias, of those who quit without medication, 5% were abstinent at six months, compared with 14% at six months.

Trends in proportion of smokers and ex-smokers who quit unassisted

Successive Cancer Institute NSW Smoking and Health Surveys from a decade ago and a 2011 ITC study indicate that the proportion of smokers and ex-smokers quitting or attempting to quit unassisted is falling (Cancer Institute NSW 2009, Cancer Institute NSW 2011, Cooper, Borland et al. 2011). In NSW, the proportion of smokers and ex-smokers who quit or attempted to quit cold turkey on their most recent quit attempt fell from 68% to 55% between 2005 and 2012 (Cancer Institute NSW 2009, Cancer Institute NSW 2011). The ITC study reported that in Australia the proportion of smokers and ex-smokers who quit or attempted to quit without help fell from 63% in 2002–03 to 41% in 2008–09. The pharmaceutical industry’s large-scale efforts to promote the use of its products appeared to be succeeding in undermining many unassisted attempts, despite the lack of evidence in populations where smoking prevalence is falling that smokers’ nicotine dependency is “hardening” and is instead more likely to be softening (see Chapter 5).

Stop smoking medications in low-income nations

Pharmaceutical aids to smoking cessation became available in different nations commencing from the early 1980s. However, in many nations they remained for a long time either unavailable or priced well beyond the reach of all but the well-to-do. For example, a 2012 report on use of medications to quit in the past year found rates above 40% in the UK, USA, Canada and Australia but below 10% in Germany, Uruguay, Mexico, China, Thailand and Malaysia (Borland, Li et al. 2012).

When I visited Cambodia in 2010, a pack of 105 2-mg NRT gum was selling for US$58.10. Product information for 2-mg Nicabate™ gum advised a maximum of 20 pieces per day. Even if we were to halve that, a 30-day supply would have cost a Cambodian smoker US$166, when the average monthly income then was US$170. The corresponding cost for the same product used at the same rate for a month in the Philippines is US$140.50, where the average monthly income in 2010 was US$171. Data on the cost of NRT and varenicline in low-income nations in the Middle East and North Africa shows a similar picture (Heydari, Talischi et al. 2012). At such prices, quite obviously, NRT was utterly beyond the reach of anyone but wealthy elites in the world’s poorest nations.

In a 2010 study, only 5.6% smokers in China used smoking cessation medications (Jiang, Elton-Marshall et al. 2010). Cessation treatments are unlikely to be an important factor that directly affects the quit rate or motivation to quit in China, home to the largest number of smokers in the world (Qiu, Chen et al. 2020), and in 2021 this was emphatically confirmed. In a six-city survey of men, 972 (31.5%) were unassisted cessation attempters and 535 were ex-smokers of whom 521 (97.6%) achieved abstinence without assistance. This abstinent group accounted for 18.6% of smokers (prior and current smokers) (Jiang, Yang et al. 2021).

Notwithstanding this, in Chapter 5 I’ll look at an attack made on our work in a public health ethics journal where two authors tried to suggest that any detraction from the mission to encourage smokers in low-income countries to use quit-smoking medications was somehow unethical (Bitton and Eyal 2011).

Forty-two years after tobacco dependence was officially recognised for the first time in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) by its inclusion in the third edition of the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III) (Neuman, Bitton et al. 2005) and some 35 years after NRT started to be heralded as the first big hope for smoking cessation, it is time to take stock of cessation pharmacotherapy. It appears that this “treatable condition” is not responding as hoped to NRT or to the prescription smoking-cessation medications bupropion and varenicline that followed. Sadly, it remains the case that by far the most common outcome at 6 to 12 months after using such medication in real-world settings is continuing smoking.

Undoubtedly, much smoker resistance to using cessation medication is due to many smokers learning from other smokers that real-world experience of using these drugs does not produce outcomes that remotely compare with benchmarks for other drugs they use for other purposes. Few if any other drugs for any purpose with such abject track records would ever be prescribed. Despite massive publicity and (in some nations) subsidies given to NRT, bupropion and varenicline during these decades, the additional tens of millions of persons (or hundreds of millions globally) who quit smoking in this time continued to dominantly include those who quit without pharmacological or professional assistance (Fiore, Novotny et al. 1990, Pierce, Cummins et al. 2012). For the ever-optimistic evangelising assisted cessation, this is perennially explained as sub-optimal reach or message dissemination. Their solution is invariably that effort should be redoubled to facilitate greater access to assistance, improving smoker knowledge about the benefits of assistance and further individualised treatment. But after over four decades of the pharmaceutical industry’s turbo-charged, no-expense-spared efforts to increase physician engagement and erode population resistance to pharmaceutical-based cessation, how many more years can the narrative of getting even more smokers to medicate retain any realistic credibility?