4

The modest impact of most popular interventions

It is now commonplace for cessation researchers to note that many smokers do not use NRT, bupropion or varenicline correctly or for sufficient duration and that professional support can improve quit rates. But how many smokers are even interested in receiving such support?

We have known for many years that smokers overwhelmingly express a preference to quit on their own. In a 1990 South Australian study, 46% of smokers were uninterested in any of the eight options for assistance with quitting. But these would have included many smokers who were not interested in quitting at all. The most preferred option (24%) was for a “program through your doctor”. Only 7% were potentially interested in a stop smoking group, and 0.6% in using a quitline (Owen and Davies 1990).

In this chapter, I’ll discuss some of the main interventions with mass-reach potential that smoking-cessation advocates have proposed to assist large numbers of smokers to quit, as well as what the evidence shows about the potential of each.

Quitlines

Of all smoking cessation interventions, contacting a phone quitline involves the least inconvenience and costs a smoker nothing. For decades, we have been used to calling helplines for everything from support for problems across a wide range of consumer goods and services, including appliance problems, warranties, insurance and travel. So if any form of help was to be a good candidate for attracting the most smokers, quitlines would be it.

Phone quitlines have held great promise as relatively inexpensive, highly accessible services to support smoking cessation (Stead, Perera et al. 2007). Clinicians time-pressed or lacking confidence in how best to deal with seemingly intractable smoking inpatients might feel assured by specialised referral services available in some nations. Yet, with few exceptions, the literature examining their use and outcomes shows that very few smokers (6% appears to be the best achieved) (Miller, Wakefield et al. 2003, Cummins, Bailey et al. 2007, Woods and Haskins 2007) seem prepared to even call up a quitline, despite the lines being highly publicised, including their phone number being shown on all cigarette packs in some nations. In 1993 at a time when California experienced large-scale, well-funded tobacco control campaigns, a much-publicised quitline saw only 0.05% of smokers ever call up for advice (Zhu, Rosbrook et al. 1995). In 2004–05 in the USA, an average of 1% of smokers contacted a quitline (Cummins, Bailey et al. 2007). A decade later, this had not moved, with about 1% of smokers still ever calling one up (Rudie and Bailey 2018).

But do the outcomes of quitlines match their promise even for the small proportions of smokers who ever contact them? In a nation where NRT was already free to smokers, a large English RCT (Ferguson, Docherty et al. 2012) comparing standard quitline support with (a) free NRT and (b) six follow-up calls from the service to smokers provided important information about two central questions about assisted cessation:

- What proportion of smokers wanting to quit are interested in receiving support and medication in an environment where NRT is already provided free via doctors?

- Does assisted cessation offered in real-world conditions match the outcomes achieved in clinical trials?

The data in this large study invite questions about how acceptable the offered interventions are even to smokers who express interest in quitting. Of 75,272 smokers making quitline contact and expressing interest in quitting over the recruitment period, 26,468 (35%) agreed to receive further support, but only 5,355 (7%) agreed to set a quit date. It would seem, therefore, that the vast majority of calls to quitlines may not be from those who are on the cusp of a serious quit attempt. Many may be making general enquiries on how to go about quitting but are not ready to try. In this trial, it appeared that some may also have accessed the quitline via the web or by interactive television, and so may have been less inclined to agree to a telephone-based form of ongoing support: people self-select into the mode of communication with which they most feel comfortable and online support is increasingly popular (see later on in this chapter).

Among this large group of trial participants who were motivated to quit and willing to receive further support, the authors noted that the take-up of the offered intensive telephone follow-up was similar to the use of such interventions among standard care participants. This was most likely to be because in the UK these interventions were already widely accessible. The findings here are important because they challenge the commonly expressed assumption that offering ever more intensive telephone support might increase quit rates. In fact, the study showed that there is probably an upper limit to consumer preparedness to accept more intensive support-based interventions, or to making the pathway to NRT even more accessible than it already is.

At six months, those in the study who were allocated NRT saw marginally lower self-reported cessation rates than those participating in standard telephone interaction, and quit rates were significantly worse in the group given free NRT once exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) validation of smoking cessation was taken into account: 6.6% of those in the NRT study arm were CO validated as having quit, compared with 9.4% of those in the no-NRT arm.

Unlike in clinical trials, cross-sectional and cohort studies of real-world cessation mostly show that those quitting unassisted have better success rates than those using medication and transform far more smokers into ex-smokers (Shiffman, Brockwell et al. 2008). As discussed in Chapter 2, “indication bias” may be explanatory here, with more dependent smokers who have poorer prospects for cessation being more likely to be using medication. However, this explanation does not apply in this study because smokers contacting the quitline were randomised and levels of dependency were comparable across all three arms of the trial. Yet being offered readier access to free NRT was associated with worse outcomes. This may imply that provision of NRT in this very low-effort way might have had unintended consequences: perhaps by undermining its perceived value to smokers and/or their commitment to actually using it properly. Provision of NRT is no substitute for determination to quit. Admittedly, motivation by itself is usually insufficient in most quit attempts too (Vangeli, Stapleton et al. 2011), yet quitting primarily by one’s own means is the way in which the large majority of ex-smokers have finally succeeded.

North American quitlines

In the USA and Canada, quitlines are widespread. A 2018 report of the North American Quitline Consortium (NAQC) for the years 2006–17 provides a large amount of data on utilisation, costs and outcomes. Between 2006 and 2017, US$1.02 billion was provided to operate some 50 quitlines, with US$99.8 million in 2017. In 2017, 964,029 calls were made to these quitlines, with 333,919 (34.6%) being “unique” (i.e. first-time callers), and the remaining number of calls being repeat calls from these first-time callers. These numbers represented an estimated 0.87% of all US smokers, with the NAQC’s target being 6% or more. In not one year between 2009 and 2017 did the reach exceed 1.19% of smokers, falling some 500% below the minimum target reach set by the consortium management.

There were 52 state quitlines invited to participate in the 2017 survey. Only 27 of these reported data on callers’ self-reported quit-smoking and response rates, and of these only six reported response rates of over 50% from callers to questions about quitting. With these very major caveats, 27.6% of quitline callers who responded reported having not smoked for 30 days or more (Rudie and Bailey 2018).

The report does not provide denominator data on which the “reach” percentages were based. However, if we were to very generously assume that 27% of 0.87% of smokers living in these states quit for 30-plus days among North American smokers in the 53 states in which NAQC consortium members ran quitlines, then 0.23% of smokers in these states may have been helped to quit by these services (23 in 1000 with this figure almost certainly being much lower because of non-response bias most likely being weighted heavily toward those who did not quit).

With these low levels of reach, and even lower levels of population-attributed smoking cessation rates, it is hard to conclude that quitlines qualify as significant components of the factors which drive down smoking across populations. Those who run them of course defend them as being important ingredients in comprehensive approaches to tobacco control. They often wave cost–benefit data about, showing that the costs per smoker “treated” and helped to quit are trivial. The 2017 North American report cited above calculated this to be just US$1.81 per smoker “treated”, although no figure was provided on the cost per successful quit attempt.

Stop-smoking groups and counselling

John Pinney, a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s US Office on Smoking and Health, published estimates of the availability of quit-smoking products and services in the USA in 1995. A survey of group programs in 10 US cities found that in four of them, nothing was being offered by a major voluntary health agency because of “lack of demand”. Data provided by three commercial smoking cessation vendors, SmokeEnders, Smoke Stoppers and SmokeLess showed 108,000 “cessation program unit sales” (presumably course fees paid by individuals) in 1993; “estimated sales” obtained from Marketdata (presumably a market research group) for 1993 showed a miscellany of 1,120,500 offerings provided by 14 agencies or commercial groups and two treatment modalities, hypnosis (350,000) and acupuncture (85,000). Others included the American Cancer Society (150,000 – presumably course attendance), programs offered by non-affiliated hospitals (175,000) and the Seventh-day Adventist Church (85,000) (Pinney 1995). All this occurred against a background of 47 million smokers in the USA (MMWR 1997).

A 2013 survey of contacts in 166 parties (nations) to the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) saw 121 which responded claim that 20 had a network of treatment support covering the whole country. The authors qualified all their results in their paper by writing “for the most part, their responses could not be validated, although we made a considerable effort to identify contacts as knowledgeable as possible about tobacco cessation. Where responses were unclear we corresponded with respondents to ensure that the questions had not been misinterpreted and to clarify their responses. With some questions we acknowledge a degree of subjectivity in interpretation of their meaning” (Pine-Abata, McNeill et al. 2013). Forty of the 121 nations responded that they had nationwide treatment services.

Many nations can indeed point to examples of dedicated, specialised quit-smoking centres. But to my knowledge, only six nations, Japan, Korea, England, Ireland, Thailand and New Zealand (with dedicated services for Māori people), have in recent years implemented anything approaching what might even remotely be described as a nationwide network of such centres.

A 2014 evaluation of quit services offered in New Zealand by 32 Aukati Kai Paipa (AKP) (Māori stop smoking) providers during 2012–13 estimated that 2,035 smokers who had used these services may have quit at three months. An example of one clinic, the Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Health Clinic in Auckland, was given where 211 smokers set target quit dates. Of these, 45% (n=95) were Māori and the abstinence rate at three months was 21%, yielding 19 quits. With obvious understatement, the report concluded, “This is clearly a small percentage of the total number of Māori smokers in Auckland, 5,637.” The annual budget for these services was NZ$5.8 million.

The report concluded, “Apart from the wide variation between the District Health Boards these data demonstrate that AKP is not a means for producing mass quitting on the scale necessary for reaching the 2025 [smoking prevalence reduction] goal. Even a doubling of the numbers of quitters by AKP would not substantially impact on the numbers of smokers in New Zealand within a ten-year period.” In 2013 there were 460,000 smokers including 122,000 Māori smokers and 702,000 ex-smokers in New Zealand (SHORE & Whariki Research Centre 2014).

I was told about the provision of these services in Japan in 2009 when I visited the country to give a keynote address titled “What should we do more of, and what should we do less of in tobacco control today?” at a national meeting of smoking-cessation professionals in Sapporo, Hokkaido Prefecture. Many in the audience worked in these cessation services and were not very happy hearing my message that there was very little evidence that clinics made any significant contribution to reducing smoking prevalence in any nation.

Notwithstanding the profusion of these clinics in Japan, there is scant information about their impact in English language research publications. Were there any important findings about these centres, we’d expect publications about it in English language journals. But this has not happened.

A rare evaluation of a smoking cessation clinic in a Japanese community teaching hospital reported on data from all smokers who had participated in a three-month cessation program comprising combined pharmacological treatment and cognitive behavioural therapy (Tomioka, Wada et al. 2019). During the decade 2007–17, only 813 smokers participated, with 433 (53.3%) completing. Of these, 288 (66.5%) achieved smoking cessation for four weeks – 35% of those who had enrolled. So this clinic graduated an average of just 29 quitters a year, many of whom would be expected to relapse in the months that followed, and some of whom may have quit anyway, had they never attended the clinic.

Such numbers are utterly trivial, even when multiplied many times over to account for the additional similar numbers from different clinics, when considered against the goal of maximising smoking cessation across a whole population in a country as populous as Japan.

In the opening presentation at the 13th Asia Pacific Conference on Tobacco or Health (APACT) held in Bangkok in September 2021, the opening speaker stated that Thailand has some 560 quit-smoking clinics. I’ve found no published assessments in English of the contribution of these clinics to reducing smoking prevalence in Thailand.

The English experience with quit-smoking centres

In April 2000, England embarked on what was almost certainly the most intensive and widespread effort the world has ever seen to set up a nationwide network of specialised smoking cessation centres. A large body of research and commentary was published about this experiment, which continues today, albeit in a much-reduced form (Action on Smoking and Health 2019).

In 2005, the journal Addiction published a supplement containing a collection of papers describing the establishment and early evaluation of a network of smoking treatment services and centres across England. A 1998 government white paper, Smoking kills, had made the case for such a network. The first paper in the supplement set out a history of the establishment and implementation of smoking-cessation services in England (McNeill, Raw et al. 2005).

Early in their paper, the authors made the remarkable statement that “Although it was not expected that smoking cessation treatment would influence smoking prevalence directly, treatment had been identified as an important and complementary approach to tobacco control.” Despite this frankly underwhelming prediction of the centres’ likely net impact (having no direct impact on reducing smoking prevalence), unprecedented funding was poured into their operation. Between 1999–2000 and 2002–03, £75.7 million was allocated, and £138 million budgeted between 2003 and 2006: a total of £213.7 million across seven years. Based on self-reported quitting, 518,500 smokers stopped for four weeks, although as we will see these numbers reduced dramatically when assessed at 12 months.

Another paper described the interventions offered by the treatment services. Ninety-nine percent of these recommended NRT and 95% bupropion. Group counselling was run less often in rural areas because of transportation problems. One-on-one counselling was described as the dominant mode of interaction with smokers. Coordinators of the services who were interviewed identified a variety of problems like shortages of staff with appropriate skills (51% agreed or strongly agreed this was a problem) and lack of career structure for service staff (81% agreed or strongly agreed) (Bauld, Coleman et al. 2005).

In the same Addiction supplement, two papers described short-term and one-year quit outcomes, assessing the impact of the treatment centres. At four weeks, 53% of clients were validated by carbon monoxide testing as not smoking (Judge, Bauld et al. 2005). In two areas of England (Nottingham and North Cumbria) researchers found validated quit rates had sunk to 14.6% of those who had set a quit date by 12 months, with three-quarters having relapsed. This paper did not compare either the quit rate or quit volumes obtained with the background quit rate among smokers in a comparable population without treatment centres (Ferguson, Bauld et al. 2005).

A 2010 systematic review of 20 studies published from 1990 (before the 2000 boost in provision of services) to 2007 on UK National Health Service smoking-treatment services found 15% of participants had quit at 52 weeks (Bauld, Bell et al. 2010). And an evaluation of two Glasgow, Scotland interventions (a group counselling and one-on-one counselling with pharmacists) found carbon monoxide–validated quit rates of 22.5% at four weeks, which fell to 6.3% (group counselling) and 2.8% (pharmacists support) at 52 weeks. The authors concluded, “Despite disappointing 1-year quit rates, both services were considered to be highly cost-effective” (Bauld, Boyd et al. 2011). Twelve-month cessation rates in those who attempt to quit unassisted typically are in the vicinity of 5% (Kotz, Brown et al. 2014).

Another paper in the 2005 Addiction supplement assessed the cost-effectiveness of the English treatment services in 2000–01, and compared these with the benchmark cost-effectiveness of £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) saved set by the UK’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Across 58 service centres assessed in the study, the median number of staff employed was 7.25 and the median annual total cost of each service centre was £214,900, of which 54% went to NRT and bupropion costs, 38% to staff costs.

Allowing for relapse, they extrapolated the costs of achieving four-week quit rates to 12-month permanent quit rates attributable to the services’ intervention as being an average of £684, falling to £438 when savings in future healthcare costs were counted. These figures were thus well below the £20,000 QALY benchmark, causing the authors to conclude that the services were “a worthwhile investment for health providers compared to many other health-care interventions” (Godfrey, Parrott et al. 2005).

Given that a large majority of ex-smokers in whole populations quit smoking without any treatment from smoking cessation services, this bullish conclusion ought to have reasonably been compared to the cost-benefits of unassisted cessation. The zero costs to the government of people quitting without ever going near a professional service or using state-subsidised smoking cessation medications balanced against the benefits of this group’s into-the-future healthcare cost savings would of course have produced an impressive headline, but not one that would have been welcomed by advocates of the dominant treatment paradigm in England.

Impact of English quit services on smoking prevalence

So what did all this achieve nationally? A 2005 report concluded, “Nationally, stop smoking services achieved a reduction in prevalence by 0.51% in 2003/04. If persisting up to 2010, this success would lead to a reduction in prevalence of 3.3% – i.e. from the current level of 26% to 22.4%.” The report then heavily qualified this by noting that the estimates were based on self-reported quit rates recorded at just four weeks after attendance at the services but that 75% of early quitters are known to relapse by 12 months.

The authors then provided a revised contribution of the English quit services, writing, “all the estimates of reduction in prevalence … could legitimately be divided by four – producing an overall reduction in prevalence of 0.13% per year or around 1% (from 26% to 25%) by 2010 for England” (Tocque, Barker et al. 2005).

Milne conducted a similar analysis for the English counties of Northumberland and Tyne and Wear, and concluded that “at best, current NHS smoking cessation services are unlikely to be reducing the prevalence of smoking by more than 0.1–0.3% a year”. He contrasted this with what had been achieved recently in California where between 1988 and 1995, smoking prevalence fell 10% while in the rest of the USA it fell 5.5%. California focused on legislative measures for smoke-free areas, after “heavy early investment in cessation services had produced disappointing results” (Milne 2005).

Irish researchers reached similar findings about the 93 quit service provider centres they were able to find in a 2009 study: “Reaching the recommended target of treating 5% of smokers does not seem feasible” (Currie, Keogan et al. 2010).

Some eight years after the 2005 evaluations, West et al. (West, May et al. 2013) reported that across 10 years (2001–02 to 2010–11), 5,453,180 smokers attended and set quit dates at English smoking cessation services operating through 151 English Primary Health Care Trusts (PHCTs). Some 92% of those who contacted PHCTs did so only once, with the remainder having more than one contact. The 5,453,180 number refers to the number of quit dates set, with some of these being set multiple times by the same individuals.

The West group applied longer-term relapse estimates to the four-week self-reported quit data, and calculated a 12-month cessation yield above that which would have been expected from just writing a prescription for a smoking cessation treatment. For the most recent year in their paper, this produced an additional 21,723 long-term ex-smokers nationally. Averaged across the 151 PHCTs, this is 144 per PHCT in a year, or fewer than three additional long-term quitters each week. At the time this paper was published, England had some 11.22 million smokers aged 16 and over, and some 33.3% made a quit attempt in 2011 (West and Brown 2012). So the maximum annual 12-month long reduction in national smoking prevalence attributable to the PHCT centres might be about 0.19% (19 in 10,000 smokers) or 0.58% of all those in England making a quit attempt.

A 2019 report from England’s leading tobacco control advocacy agency, Action on Smoking and Health, lamented the 30% cut in local authority funding of specialised stop-smoking services between 2014–15 and 2017–18. It found that 89.8% of expenditure on total tobacco control was spent on specialised stop-smoking services, with the residual spent on issues like illicit trade investigation and promoting smoke-free areas. Quit rates measured at four weeks after treatment saw that the highest quit rates (414 per 100,000 smokers (0.41%) were in those local authority regions which employed specialised quit-smoking staff (Action on Smoking and Health 2019). Again, significant relapse after four weeks would be expected.

It is likely that many of these smokers attending cessation services would have stopped smoking anyway in the absence of the services, because as I have shown throughout this book it has always been the case that most people who quit smoking do so independently of any formal assistance, pharmacological or behavioural.

In England, 4.8% of people who smoked in 2010 were not smoking in 2011 (West and Brown 2012). This translates to some 538,560 ex-smokers. Those additional 21,723 who quit for 12 months after attending an English cessation PHCT centre thus represent about 4% of all those who most recently quit for 12 months.

From the variability in cessation across the PHCT centres, the authors argue that those which provided less intense support should be funded more to allow greater intensity of contact and higher quit rates to occur. If a goal of such services is to contribute meaningfully to population-wide cessation, West et al.’s data would suggest that such centres are unlikely ever to be a significant platform for reducing smoking prevalence under realistic funding increases; and exemplify the inverse impact law of smoking cessation (Chapman 2009). West has described the cessation services as the “jewel in the crown of the NHS” (Triggle 2013). If services responsible for 4% of long-term quitters are described like this, what superlatives would be appropriate descriptions for the policy and advocacy factors that motivated 96% of smokers to quit long-term without needing to access these services?

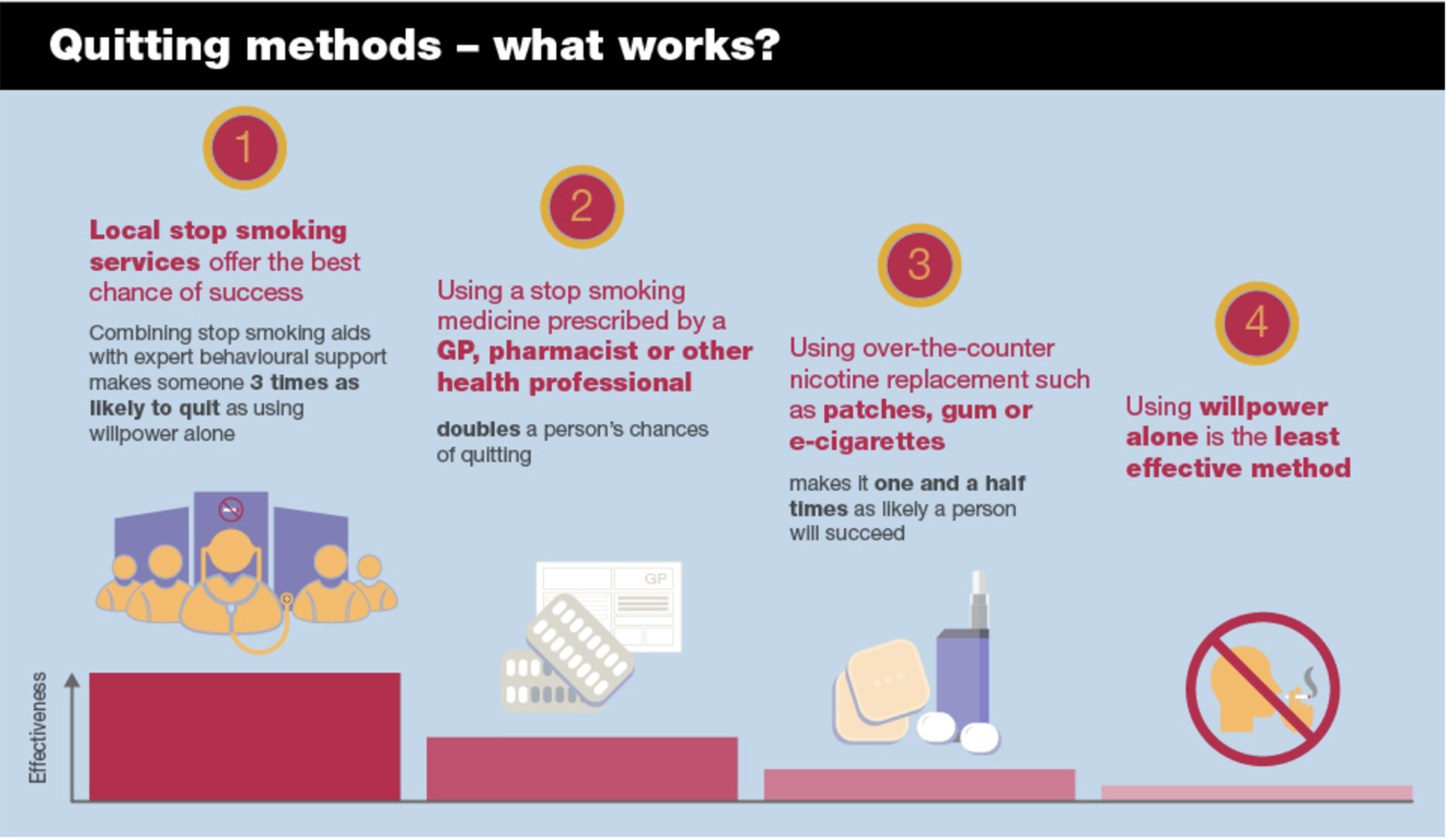

Public Health England (PHE) updated its guide to quitting smoking in 2019 and included Figure 4.1. If we were looking for a candidate graph which best illustrated the “weapons of mass distraction” metaphor for smoking cessation, this is it. If PHE had set out to answer the question, “What have been the methods used by most of England’s ex-smokers when they finally quit?” the graph would have of course been completely different, with what they call “willpower” or unassisted quitting towering over all the other methods, and attendance at England’s specialised smoking-cessation centres requiring a magnifying glass to help readers see their tiny contribution.

Figure 4.1 Quitting methods: success rates. Source: (Public Health England 2019).

Apart from the brief embrace of quit clinics I described in the introduction which occurred in Sydney in conjunction with the 1981–83 Quit. For Life campaign, Australia has never been down a path proliferated with quit clinics. Indeed, there has never been any significant lasting clamour calling for this to happen. A census undertaken in 1992 of all Australian stop-smoking centres reported that the “throughput” (i.e. total number of smokers) attending was 8,800, representing just 0.2% of the 3.837 million Australian smokers at that time (Mattick and Baillie 1992).

Workplace smoking-cessation programs

A sibling of the dedicated smoking-cessation service is the workplace smoking-cessation program. These are typically externally run programs where smoking-cessation specialists come to workplaces either in person or virtually via online or telephone counselling, and offer assistance to smokers wanting to quit. Management offering a variety of health promotion programs and facilities (such as gyms, healthy canteen food choices, stress management) are often also keen to reduce smoking among their staff, with higher absenteeism among smokers being one motivator (Halpern, Shikiar et al. 2001).

A 2004 review of 19 papers reporting on workplace smoking cessation programs covering doctors’ advice, education, cessation groups, incentives and competitions found no evidence that early cessation results persisted beyond 12 months (Smedslund, Fisher et al. 2004).

A 2014 Cochrane review of smoking-cessation programs offered in workplaces found “strong evidence that some interventions directed towards individual smokers increase the likelihood of quitting smoking”, noting, “All these interventions show similar effects whether offered in the workplace or elsewhere” (Cahill and Lancaster 2014).

As always, we need to look at the reach of such interventions if we are to understand whether promising methods of quitting have any hope of having a measurable impact across a population. Here the Cochrane review noted, “Although people taking up these interventions are more likely to stop, the absolute numbers who quit are low.”

GP interventions

In 1979, Michael Russell (1932–2009) from the Addiction Research Unit of the Institute of Psychiatry, University of London published a paper with colleagues in the British Medical Journal (Russell, Wilson et al. 1979) where they estimated a blue-sky impact on smoking cessation in England if every general practitioner was to urge all of their smoking patients to quit. Given that it is extremely doubtful that there is any important intervention in all of medicine which every doctor always urges all appropriate patients to use, such a benchmark was always going to be highly fanciful.

Over four weeks, the Russell group recruited all 2,138 cigarette smokers attending 28 general practitioners in five group practices in London. These were allocated to one of four groups: a control group who received nothing; another control group which was just given a questionnaire on smoking; a third group who were advised by their GP to stop smoking; and a fourth group who were given a leaflet on quitting, and told that they would be followed up by their GP. Follow-up data were obtained from 88% of patients at one month and from 73% at a year.

The proportions in these four groups who stopped smoking during the first month and were still not smoking a year later were 0.3%, 1.6%, 3.3%, and 5.1%. These differences in outcomes were highly statistically significant (P<0.001).

The authors concluded that “any GP who adopts this simple routine could expect about 25 long-term successes yearly. If all GPs in the UK participated the yield would exceed half a million ex-smokers a year. This target could not be matched by increasing the present 50 or so special withdrawal clinics to 10,000”.

Russell’s paper, with its promise for population-wide major impact on tobacco control by the simple giving of advice and warning of follow-up to all smokers, lit a fuse of excitement among those working in tobacco control. It launched an era within tobacco control of smoking cessation research in primary healthcare settings which spread from work with GPs, to dentists, health visitors and ancillary healthcare workers. In the decades that followed, all national or international tobacco control conferences included a well-attended stream on smoking cessation in healthcare settings.

So how did things develop, with such potential being promised? Let’s first look at some evidence about how many GPs even recognise which of their patients smoke.

In 1989, researchers from the University of Newcastle in Australia published a fascinating study reporting on the extent to which general practitioners identified and attempted to give brief quitting advice to smokers in their practices (Dickinson, Wiggers et al. 1989). The researchers approached 108 GPs to obtain their consent to interview patients prior to their consultation, and to tape their consultations with the doctors. Of those doctors approached, 56 consented, as did 2044 (76%) of eligible patients. The study was conducted over 18 months.

The GPs correctly identified only 56.2% of smokers, a rate just above coin-toss accuracy. Those who identified smokers gave brief counselling on smoking cessation to 78% of those who had a smoking-caused disease; 40% with smoking-exacerbated disease; and 35% of those with no smoking-caused or exacerbated diseases. Importantly, these rates were obtained while GPs were consenting to have their consultations recorded. Knowing that their clinical practices were monitored by researchers interested in public health and prevention, it is highly likely that most if not all the doctors in the study would have tried to be on their very best behaviour as diligent prevention-focused clinicians. The rates of correct identification and counselling obtained were therefore likely to be high, with the GPs’ real-world, unobserved rates likely being lower than those recorded under such “be on your toes” observation conditions.

In 1996, the same research group analysed 1,075 audiotapes of patient interviews with doctors and found patient recall was systematically biased toward over-reporting of a question being asked about smoking (Ward and Sanson-Fisher 1996).

The Newcastle group returned to this issue in 2001, with only 34% of GPs who returned a questionnaire reporting that they provided cessation advice during every routine consultation with a smoker, as advised in national smoking cessation guidelines (Young and Ward 2001). In 2015, they again revisited the issue. This time, the participating GPs correctly identified 66% of their smoking patients as smokers, a big increase in the intervening years. The researchers approached 48 GP group practices with 12 (25%) agreeing to be involved. Together, these had 87 doctors of whom 51 (59%) agreed to participate. With study participant information undoubtedly explaining that this was a study about doctor–patient interactions on smoking, again, it is highly likely that those practices and doctors who declined participation were less likely to be those who knew they gave particular attention to smoking. This sample is therefore likely to be one biased toward doctors who had awareness of smoking as an important focus in primary healthcare. Yet even here, as recently as 2015, we see rates of physician engagement with smokers that remain far below Michael Russell’s 1979 promise of every smoker being counselled to quit by every doctor they ever saw.

In England, a study of 29,492 smokers attending primary care in the Trent region in April 2001 found only 1,892 (6.4%) were given prescriptions for smoking cessation treatments across subsequent two years. With quintessential English understatement, the study authors concluded that this low proportion “strongly suggests that a major public health opportunity to prevent smoking related illness is being missed” (Wilson, Hippisley-Cox et al. 2005).

In 2000, the US National Cancer Institute published a 230-page monograph titled Population based smoking cessation: proceedings of a conference on what works to influence cessation in the general population (National Cancer Institute 2000). In the first chapter, tobacco control veteran David Burns summarised the promise of physician-assisted smoking cessation:

The gap between the effect achieved in clinical trials and the population data defines the potential that can be achieved if these modalities are delivered in a more comprehensive and organised manner and integrated with other available cessation resources. If physician advice achieves the effectiveness demonstrated in clinical trials, it could result in as many as 750,000 additional quits among 35 million smokers who visit their physicians each year. If the success rate of pharmacological interventions matched that in the clinical trials, as many as 500,000 additional quits each year could be achieved, and an even greater number could be expected if the larger numbers of smokers who are trying to quit could be persuaded to use pharmacological methods.

One approach to improving the results seen with physician advice and pharmacological interventions is to increase the fraction of smokers who receive advice or use cessation assistance. However, a great deal of research and programmatic support has already been committed to increasing the frequency with which physicians advise their smoking patients to quit, and this effort has shown a substantial increase in the fraction of patients who report that their physicians have advised them to quit. Independently, pharmaceutical companies have advertised the availability of cessation treatments extensively, which has resulted in substantial demand for and use of these interventions. Both of these efforts should continue, but it is not clear that additional resources would add to the number of individuals encountering either of these two interventions, and given the limited evidence for a population based effect on long-term cessation for either of these interventions as they are currently practised, allocation of additional resource may not be appropriate … the promise of these interventions as established in clinical trials is not fulfilled in their real world applications. [my emphasis]

Anyone thinking this very blunt conclusion might have sounded the death knell for efforts to have physicians become more active in promoting smoking cessation would have been very mistaken. Those working in this area have never swerved from the pursuit of Michael Russell’s blue-sky calculations where every doctor counselled every smoker.

Pooled data from the US National Health Interview Surveys between 1997 and 2003 found 84% of Americans saw a primary healthcare provider (HCP) in the past year (range across different respondent occupations 68% to 95%). Across all occupations, 53% of smokers had been advised by a HCP to stop smoking (range 42%–66%) (Lee, Fleming et al. 2007).

By 2020, the US Surgeon General’s report on smoking cessation concluded that “advice from health professionals to quit smoking has increased since 2000; however, four out of every nine adult cigarette smokers who saw a health professional during the past year did not receive advice to quit” (United States Surgeon General 2020). In more than a decade, physician advice rates had only moved up slightly.

Despite these undeniably depressing findings, very clearly, any suggestion that HCPs should in any way be discouraged from advising smokers to quit would be irresponsible. Smoking is such a huge risk factor for so many health problems that the case for it being routinely noted with patients as a vital sign as important as temperature, pulse and respiratory rates, blood pressure and weight is unarguable. Yet with current rates of advice to quit from physicians being less than 60%, and over four decades having passed since Russell’s famous recommendation of brief advice to quit, GP advice to quit rates remain trenchantly and scandalously low, showing little evidence of significantly rising.

Online quit interventions

The revolution in online interactive communication has seen a huge increase in the availability of programs to assist and support people wanting to improve their health in such areas as dietary change, physical activity, mental health, and substance use, including smoking cessation.

A 2017 Cochrane systematic review of 67 trials of online smoking-cessation interventions involved data from over 110,000 participants, with cessation data after six months or more being available for 35,969 smokers. The interventions ranged from simple provision of a list of smoking cessation websites to those involving internet, email and mobile phone delivered components. The review found that interactive and tailored internet programs led to higher quit rates than usual care or written self-help at six months or longer. However, the estimate of these “higher” rates in pooled results was very modest with confidence intervals crossing the null, and therefore being statistically non-significant (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.22, n= 14,623), and many of the studies being classified as having moderate to low study quality and at high risk of bias. The review therefore provides very little that suggests these potentially mass-reach interventions are currently producing anything more than a good deal of activity rather than cessation achievement (Taylor, Dalili et al. 2017).

The Australian Department of Health has made available an app, My QuitBuddy, which allows smokers to see motivational and supportive data on their quitting progress. On World No Tobacco Day 2020, the Minister for Health, Greg Hunt announced that between January and May in the early months of COVID-19, the app had been downloaded more than 24,000 times, “a staggering 310 percent increase over the same time last year” (Hunt 2020). This means that in those months in 2019, it was downloaded fewer than 6,000 times. Curiously, no one I’ve spoken to has seen any evaluation of whether most of those downloading the app use it and whether they attribute any quitting success to it.

Contingency payments

Contingency payments in health promotion campaigns are where people receive monetary rewards or prizes for achieving particular outcomes. These can include cash, extra workplace leave, store vouchers or the return of money deposited by participants to motivate them to change. Smokers are sometimes promised incentives if they quit, typically needing to sustain this for a few months. These schemes have been run in a variety of settings, particularly in workplaces where they are sometimes bankrolled by management.

A 2021 Cochrane review of behavioural interventions found high certainty that, compared with those who received no smoking cessation support, smokers who received financial incentives had 1.5 times greater odds of successfully quitting (Hartmann-Boyce, Livingstone-Banks et al. 2021). The 2019 Cochrane review compared the financial amount of the incentives that varied between trials, ranging from zero (self-deposits) to US$1,185, although no clear direction was observed between trials offering low or high value incentives. A 2020 meta-analysis similarly found no clear relationship between the amount of financial incentives and quit rates. The incentive amount may also affect socioeconomic groups differently.

To my knowledge, these schemes have never been “upscaled” from time-limited experimental status often run by researchers to national, state or city-wide operation. This contrasts with incentives currently operating in some countries to encourage people to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

But there are important differences between a nation’s concerns to have large and rapid increases in COVID-19 vaccination and national concerns to reduce smoking rates. The prevalence of active COVID-19 cases is causing massive economic damage to major sectors of entire nations. Smoking has negative economic consequences too, but these do not rain down in pandemic intensity, rather slowly percolating throughout nations year in and year out. For this reason, it seems highly unlikely that any government would invest in incentive payments to smokers for them to quit. And as I flagged earlier, many lifetime non-smokers might reasonably ask whether they too ought to be rewarded with a government financial incentive for having decided to never smoke. That prospect seems even more remote.

Quit and win lotteries

A related financial incentive smoking cessation scheme is “quit and win” (Q&W) lotteries. Here, smokers enter their name to win a sometimes substantial prize like a car or family holiday if their name is drawn at a date after the lottery entry period has closed and their non-smoking status is then confirmed by biochemical test. Those entering the lotteries are encouraged to be honest: a non-smoker entering and pretending to be a smoker could be drawn as a winner and verified as a non-smoker, although those organising the lotteries can try to minimise the chances of this happening by also requiring any winner to name a person of standing in the community (such as their doctor) to certify that they were a smoker at the time they entered.

Q&W lotteries had their heyday in the 1980s and early 1990s when their novelty energised many people working in smoking cessation to set them up in the hope that they would stimulate large numbers of smokers to enter, quit and remain ex-smokers long after the lotteries had been drawn. I was one of them. An early review of 12 lotteries in Minnesota, USA, reported that between 1% and 5% of smokers in local communities entered (Pechacek, Lando et al. 1994). In 1991, I worked with a television station in Newcastle, NSW, to run and evaluate a Q&W lottery. A local car dealer donated a small new car in return for publicity for his business. I drew and announced the winning entry, and drove with the film crew to a Hunter Valley coal-mining site where a miner was the lucky winner. I stood by in a urinal block where he supplied a urine sample for cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) testing to confirm that he was not smoking. His doctor confirmed that he had indeed been a smoker.

We published an evaluation of the lottery (Chapman, Smith et al. 1993) finding that in an estimated district population of 101,300 smokers aged 20 and over, 1,167 (1.15%) people had entered after duplicate entries were removed. We also discussed a core problem that besets most accounts of whether such interventions help smokers quit: lead time bias. This bias is sometimes called “borrowing from the future” bias and refers to the issue of whether quit lotteries genuinely increase the numbers of ex-smokers in communities in which they are run, or whether they simply provide an illusion of success by attributing a cessation effect to a researched event, when the attributed quitting volume may well have occurred in the absence of the lottery, reflecting a secular trend to quitting. Some smokers who enter these lotteries may have intended and succeeded in quitting even if the lottery had not been run. If they brought their quitting forward a few weeks or months from when it might have occurred anyway (thus borrowing from the future), the net quitting numbers across a wider time may not have been different. This is of course a question that can be asked about any intervention, and one that can only be resolved by comparing observed with expected changes over longer windows of time. Unfortunately, few research groups have sufficient resources to conduct such studies or have access to local or regional data that could help answer the question.

A year later in 1992, I had an opportunity to test whether a Q&W lottery, promoted via national television, with entry undertaken through a national chain of 4,177 pharmacies and a prize of a $30,000 car, might do any better than the earlier lottery run in Newcastle. A health magazine program, Live it Up, screened across Australia on Sunday evenings on the Channel 7 network. In six sequential episodes an estimated 1,466,000 people viewed all six episodes. The lottery received 7,769 entries, with about 7% being multiple entries from the same people. Forty percent of pharmacies submitted no entry forms.

So some 7,236 unique individuals from an estimated 1.446 million viewers (1 in 200) entered. I became intrigued with another question. How many entrants were trying to game the lottery by pretending to be smokers when they were not?

Several months after the Q&W lottery had been drawn, we followed up a random sample of 10% of entrants from the Sydney area (n=300), and had an independent experienced interviewer remind those questioned that the contest was long over (Chapman and Smith 1994). She then asked them whether they had in fact really been smokers when they entered. Nearly one-third of those questioned admitted that they had entered the lottery on false pretences, saying that they were smokers when in fact they were not. Those who said that they were smokers when they entered the lottery were asked about their smoking status at follow-up. Of 4,777 entrants who were smokers, 530 (11%) either quit during the six weeks of the program or in the three months before follow-up interview.

So here was a mass-reach intervention that saw six segments of a nationwide television program broadcast in early evening prime time on a weekend. Each program segment was designed to be maximally motivating to smokers. The substantial prize was expected to entice large-scale participation in the lottery, turbo-charging the levels of background quitting that would be expected to occur across the weeks that the program ran, had the intervention not run.

Using the most recent population data on smoking, we estimated that across the four months of the TV program and follow-up interval, some 25,328 smokers would have quit across Australia. We don’t know how many of the 530 self-reported quitters who entered the lottery would have quit regardless, nor do we know how many smokers who watched and were inspired to quit but didn’t enter the Q&W lottery. But making non-heroic assumptions about these numbers and remembering that many of those who reported quitting would relapse in the months and years after follow-up, it would have been very difficult to sell the story that this innovative intervention which was seen by large numbers of smokers caused anything but a tiny, one-off ripple of cessation across Australia.

How much intervention research is ever “upscaled” to become routine in mass-reach settings?

If you open the pages of public health research journals, for over 50 years, you will find a very large number of trials and evaluations of what is known as intervention research. These can include interventions in clinical settings looking at the effects of drugs, diagnostics or procedures on relevant health outcomes; interventions in community settings where groups of people in existing networks like workplaces, schools or among self-selecting community participants want to improve their health; or in whole populations as might occur with a change in laws, regulations, product standards or local government policies.

Research agencies which fund intervention research, and governments which provide those agencies with funding for competitive distribution to the best applicant research groups, invariably justify this funding as a vital step in producing evidence-based knowledge that has the best chance of improving public health. The thinking goes like this. First, what health problems are regarded as having high priority in prevention or treatment, with considerations of greater safety, effectiveness and equitable access to all relevant populations? Problems which adversely affect large numbers of people, and which cause significant burdens of death, illness and lower quality of life are often given priority status by grant bodies when they ring-fence special funding for such problems.

Second, does a research proposal describe a proposed intervention which, if successful, would be likely to attract significant interest well beyond academic research circles after it has concluded? For example, if a trial of a smoking-cessation program for hospital in-patients was found to be very successfully conducted and produced clearly higher quit rates in participants than in matched controls, would this be likely to be widely adopted in other hospitals?

Third, which researchers and groups have proven track records in both conducting and publishing high-quality research on such priority issues? Research grant agencies try to back proven research champions, and also look at the presence of early career researchers on a team who will hopefully benefit from research apprenticeship with more experienced colleagues.

Then there is a fourth consideration: one which in my experience is given far less attention by grant review committees who select and rank applications. This is the question that considers the ultimate “so what?” of research applications. It concerns the whole issue of what is the point of trialling, evaluating and publishing lots of intervention-relevant research when so little of it ever becomes adopted later? How much research ever becomes “upscaled” so that its findings change the way things are done in the world long after a demonstration research project shows it has promise? It goes well beyond asking about the reception a piece of research has had within the very cloistered world of one’s national and international research peers, via metrics like high citation rates from other researchers or keynote speaking invitations to the peak global conferences or prestigious awards.

It fundamentally answers the question “Did this research change things for the better?”

I often find myself in situations where people I’ve just met ask me what I “do” in my work. It’s easy to explain the day-to-day of teaching and research in a university. Most people understand that research is published in scholarly journals. They are very familiar with news media reports of interesting or breakthrough research, and hearing the researchers involved talk about why the research they have done is important and what it might change for the public good. But you can see the penny drop when you give illustrations of how your work actually contributed to making a difference or leveraged change in important ways.

Perhaps of all public health research, intervention research is imbued with hopes that it might produce findings of great practical importance in changing individual, clinical, institutional, educational or regulatory behaviour and practice. Despite millions of dollars being invested in intervention research each year, little is understood about how much of this research produces findings that have utility for clinicians, communities or institutional program planners. Similarly, little is understood about the characteristics of “successful” researched interventions which go on to become widely adopted in the “real world” compared to those which are never adopted.

Toward the end of my career, I led two Australian NHMRC research grants that went to the heart of these questions. The first explored the characteristics of highly “influential” Australian researchers in six fields of public health, and the second sought to understand the nature and characteristics of intervention research that has had a demonstrated impact on policy and practice, and the research translation process by which the impact of the research occurred. In short, what is it about both research and researchers whose work in public health actually makes an impact beyond the arcane world of other researchers?

With the first project, we contacted every Australian researcher who had published five or more peer-reviewed papers in the past 10 years in the fields of alcohol, illicit drugs, injury prevention, obesity, skin cancer and tobacco control. We invited them to nominate six Australian researchers in their fields who they considered to be the “most influential”. We did not define “influential” but encouraged them to consider any characteristic that they believed defined influence. We then interviewed the six most nominated researchers in each field, exploring why they believed they were seen by their research peers as influential.

Finally, we interviewed a cross-section of politicians in health portfolios, their senior staff, senior health bureaucrats and heads of non-government health organisations, asking them about how they came to trust and work with researchers when it came to policy change matters. We published four papers on this work (Haynes, Derrick et al. 2011, Haynes, Gillespie et al. 2011, Haynes, Derrick et al. 2012, Chapman, Haynes et al. 2014).

In the context of our consideration about how much intervention research ever influences policy and practice, our work in this project concluded that with rare exceptions, all those nominated as most influential by their peers were those who, besides being excellent, highly productive researchers, very strongly believed that researchers had a duty and responsibility to disseminate their research as widely as possible. Almost all were well-known public advocates for change in their fields. They appeared regularly in news media, led peak committees, and actively sought to bring their work to the attention of policy makers who were in a position to support its subsequent upscaling into policy and practice.

With the second project, we focused on all NHMRC funded project grants commencing in the eight years from 2000 to 2007 that involved the conduct and evaluation of impact arising from health interventions. There were 107 of these, of which 50 research team leaders agreed to participate in our research. With those who declined to participate, we suspected that many of these were likely to have produced no evidence supporting the efficacy of their interventions and/or did not ever get subsequently implemented in relevant communities. It seemed intuitive that had an intervention proved to be successful and later taken up for use in clinical or community practice, the researchers involved would have been delighted by this and very happy to discuss it with our team. The sample of 50 comprised a mix of treatment and management (n=20), early intervention/screening (n=12) and primary prevention/health promotion interventions (n=18), implemented in clinical and community settings. Topics reflected a wide variety of health disciplines, including medicine, psychiatry, psychology, dietetics, dentistry, physiotherapy, speech pathology, nursing and public health.

We reviewed the publications arising from these 50 projects to determine if the interventions being researched had produced results that might stimulate uptake of the interventions in relevant contexts. We then interviewed the researchers about their knowledge of any such uptake and impact and looked for evidence of any impacts of the research in a wide range of sources, just in case the original researchers were unaware that their work had inspired adoption of the interventions. We produced three papers from this work (Cohen, Schroeder et al. 2015, King, Newson et al. 2015, Newson, King et al. 2015).

We found that 56% of the projects reported at least one statistically significant intervention effect of potential interest to real-world practice and that 34% had evidence of subsequent specific policy and practice impacts (such as clinical practice changes; organisational or service changes; development of commercial products or services; policy changes) that had already occurred and were corroborated. However, mostly these were quite small examples of local or institutional intervention uptake, not state or nationwide.

What I took from this was that many researched interventions do not produce positive findings that are likely to inspire adoption in the community (hopefully, failed interventions being less likely to inspire adoption). And of course that’s not a problem at all: the task of any scientific evaluation is to faithfully and transparently report all important outcomes, whether positive or negative. But our finding that for only about one in three intervention projects was there any corroborated evidence that any part or the complete intervention had subsequently become a routine part of prevention or treatment practice in health care settings or the community should give major pause.

This research finding was salutary. It suggests that many researched interventions which have been shown under trial conditions to “work” are, regardless of their positive outcomes, destined to never move onto any sort of real-world implementation after the research projects finish. Researchers move on to the next phase of their research careers and many do not see it as their responsibility to advocate for, or even publicise, what their research has demonstrated.

Excitement about interventions which perform well in trials or in field conditions is therefore often confined mostly to the academic research community. Any publicity that occurs at the time of publication, as occurs with all news reporting, rapidly fades. Research publications are often pay-walled and so inaccessible to the general public and journalists. Good news stories from research seldom translate into good news about the interventions concerned being upscaled for mass-reach potential impact. The lessons here need to be kept very firmly in mind when assessing the likelihood that promising interventions will simply progress through to being provided to sometimes millions in communities.

This chapter has looked at several very commonly advocated, potentially mass-reach smoking cessation interventions. Most, if not all, have fallen badly short of the promises held out for them over decades. Yet despite all this, in 2020 the US Surgeon General concluded, “More than three out of five US adults who have ever smoked cigarettes have quit. Although a majority of cigarette smokers make a quit attempt each year, less than one-third use cessation medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration or behavioral counselling to support quit attempts.” In just these two sentences, we have two important points: that stopping smoking is a widespread social phenomenon, and that most of those who succeed somehow managed to do it without using “approved” methods. In chapters 7 and 8, we’ll look at how this happens.