5

“Don’t try to quit cold turkey”

Figure 5.1 An English poster urging smokers not to try quitting cold turkey. NHS smokefree campaign 2008.

The figure above shows a poster that was used by government health services in England around 2010. I’m vague about the date because the poster has all but disappeared from public access, with only the rather distorted image shown above being locatable from Google Images. When I first saw it, I was just gobsmacked by the outrageously incorrect statement I’ve enlarged next to the poster in Figure 5.1. “But there aren’t many of them” (who quit cold turkey) is completely and utterly wrong. It is a weapons-grade lie which, as we have seen, is easily contradicted by data from going back several decades to at least to the 1960s, showing the constant dominance of unaided quitting among former smokers.

It is also a disabling lie, because its intent was to persuade smokers that any thought they had about quitting unaided was mere folly. A smoker would be fooling themselves if they thought they could quit without help. So the intent was to undermine any sense of agency that a smoker might harbour. The message in this poster was part of a planned and sustained effort in England by health authorities to actively try to dissuade smokers from trying to quit unaided. Its message “Don’t go cold turkey” (see figures 5.2 to 5.4) could not have been clearer: it told smokers that they should not attempt to stop without help. It wasn’t health authorities telling smokers not to give stop-smoking medications a try; it was going further and telling them not to put any trust in their own agency to quit. This was not a one-off, isolated message, but was very common and sustained in the UK and, as we shall see, a message that has come to dominate the public narrative on how to quit. If you google “cold turkey smoking”, oceans of webpages asserting the same message are instantly returned from all around the world.

In this chapter, before looking at the attacks on unassisted cessation by those promoting assistance, I’ll first examine a central premise of the case that is often made for the importance of maximising the number of smokers who need to be persuaded to use assistance when quitting. I’ll also summarise efforts that have been made to suggest that smokers ought to be supervised through a “tailored” progression toward quitting, rather than following the Nike slogan advice – “Just do it”. And I’ll also examine one of the best kept secrets in smoking cessation: a large proportion of those who quit find it surprisingly easy to do so.

I’ll then critically examine the claims made by those who would like to see as many smokers as possible who are attempting to quit be supervised and medicated in their attempts, and their reactions when this is questioned.

Figure 5.2 “Don’t go cold turkey” promotion in England. Source: Get Healthy Rotherham.

Figure 5.3 In Birmingham, UK local health workers took to shopping centres to promote their message. Source: https://www.bhamcommunity.nhs.uk/about-us/news/archive-news/cold-turkey-campaign/

Figure 5.4 The “Don’t go cold turkey” message persists in 2021 (Source: https://www.onhealth.com/content/1/tips_quit_smoking).

The slow death of the hardening hypothesis

As the percentage of the adult population who smoke continues its seemingly inexorable southward journey toward single-digits, it’s common to see and hear comments that the smokers who remain today are nearly all “hard core”. These so-called heavily dependent smokers are said to be impervious to the policies and campaigns which have caused so many millions to quit across the 60 years since modern tobacco control commenced with the publication of the 1962 Royal College of Physicians of London report and the 1964 US Surgeon General’s report, both called Smoking and Health. The argument runs that the ripe fruit of less addicted smokers has long fallen from national smoking prevalence trees, and that today most of those still smoking are profoundly addicted to nicotine and are unresponsive to the traditional suite of policies and motivational appeals that in the past have been associated with continuing declines in smoking.

This argument is known as the “hardening hypothesis”. It’s predictably used often by pharmaceutical companies; those health workers who making a living out of promoting the idea that smokers are unwise to try to quit on their own and need their professional help; and most recently by promoters of electronic cigarettes and the growing panoply of other novel products. These promoters often highlight the spectre of smokers who they insist “can’t” or won’t quit but want to switch to allegedly less dangerous ways of dosing themselves with nicotine many times a day.

The “can’t quit” group are said to be those who have “tried everything”, sometimes many times, but have repeatedly relapsed back to smoking. A well-cited 2008 paper by Karl Fagerström and Helena Furberg looking at smoking prevalence and nicotine dependency scores on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) in 13 countries concluded, “The significant inverse correlation between FTND score and smoking prevalence across countries and higher FTND score among current smokers supports the idea that remaining smokers may be hardening” (Fagerström and Furberg 2008). However, since that time, research on the hardening hypothesis has overwhelmingly found that it has little to no scientific support.

The most recognised way today of measuring the “hardness” of smoking is the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) (Chaiton, Cohen et al. 2007). This scores smokers out of a maximum of six points, comprising a score of 1–3 for number of cigarettes smoked each day, and 1–3 on the time taken after waking to light up the first cigarette of the day.

A European study with 5,136 smokers drawn from samples of over 18,000 people found that across 18 nations, there was no statistically significant relationship between a nation’s smoking prevalence and the HSI (Fernandez, Lugo et al. 2015). If the hardening hypothesis had been confirmed, nations with low smoking prevalence would have had higher HSI scores in the remaining smokers: these continuing smokers would have been smoking more cigarettes and lighting up earlier in the morning in nations with low smoking prevalence than in those with high. But they weren’t.

A 2020 review by the smoking cessation maven John Hughes of published studies on hardening (Hughes 2020) found that in none of the 26 studies he examined was there any evidence for a reduction in conversion (or transition) from current to former smoking, in the number of quit attempts, or success on a given quit attempt, with several studies finding that these measures increased over time. These results appeared to be similar across survey dates, duration of time examined, number of data points, data source, outcome definitions and nationality. Hughes concluded, “These results convincingly indicate hardening is not occurring in the general population of smokers.”

A Dutch research group went further. They calculated the prevalence of hardcore smoking in the Netherlands from 2001 to 2012. They classified smokers as “hardcore” if they satisfied each of four criteria: (1) smoked every day; (2) smoked on average greater than 14 cigarettes per day; (3) had not attempted to quit in the past year; and (4) had no intention to quit within six months. Across 12 years they found the prevalence of hardcore smoking decreased from 40.8% to 32.2% of smokers and as a proportion of the population, from 12.2% to 8.2%. Like almost all other studies, they “found no support for the hardening hypothesis”, instead suggesting that “the decrease of hardcore smoking among smokers suggests a ‘softening’ of the smoking population” (Bommele, Nagelhout et al. 2016).

There have been several papers on hardening published using Australian data. A 2010 paper (Mathews, Hall et al. 2010) examined three series of Australian surveys of smoking (National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS), National Health Survey (NHS) and National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHWB), spanning 7–10 years. The authors found that in two of the surveys (NDSHS and NHS), while smoking fell across the population, there was no change in the proportion of smokers who smoked less than daily, while in the NSMHW survey, that proportion increased from 6.9% in 1997 to 17.4% in 2007. The authors concluded that the paper presented “weak evidence that the population of Australian smokers hardened as smoking prevalence declined”.

The most recent Australian paper on this issue was published in Nature (Buchanan, Magee et al. 2021) using data from three waves (2010, 2013 and 2016) of the Australian NDSHS. The most inclusive definition of hardcore smoking (i.e. being a smoker with no plans to quit) showed a significant decline between 2010 and 2016 (5.49% to 4.85%). In contrast, the prevalence of hardcore smoking using the most stringent definition (i.e., a current daily smoker of at least 15 cigarettes per day, aged 26 years or over, with no intention to quit and no quit attempt in the past 12 months) did not change significantly between 2010 and 2016. The authors concluded,“The observed trends in the prevalence of hardcore smokers (i.e. either stable or declining depending on the definition) suggest that the Australian smoking population is not hardening. These results do not support claims that remaining smokers are becoming hardcore”.

A 2022 systematic review of the evidence on hardening described it as “a persistent myth undermining tobacco control” and concluded “the sum-total of the world-wide evidence indicates either ‘softening’ of the smoking population, or a lack of hardening” with reductions in smoking prevalence fostering even more quitting. The authors concluded “the time has come to take active steps to combat the myth of hardening and to replace it with the reality of ‘softening’” (Harris et al. 2022).

Those arguing that today’s smokers are increasingly heavily addicted and unable to stop, and therefore need assistance to do so, have very poor evidence supporting their case. Globally, vast numbers of smokers continue to stop or reduce their smoking every year. These include very heavy smokers and, as we will see below, many who quite suddenly stop smoking without making much if any preparation to do so.

There is also interesting evidence from Canada that people diagnosed with schizophrenia quit smoking at about the same rate as those in the wider population. Repeated surveys 11 years apart (1995 and 2006) in a community-based psychiatric rehabilitation program in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, found that the number of quitters tripled over the past decade and the number of daily smokers decreased by almost one-third from 63% to 43% (Goldberg and Van Exan 2008).

Those who argue that it’s now time we recognised that the traditional suite of population-focused policies and programs have run their course, that we are seeing diminishing returns and now need to call in the cavalry with widespread intensive, one-on-one support services and lifetime use of NRT or vaping – are blowing evidence-free and often self-serving smoke. In nations where net quitting rates may have slowed, the explanation is therefore not likely to be that remaining smokers can’t quit, but that we may be reaching a significant rump of smokers who are best understood as won’t or don’t want to quit die-hard smokers. In Chapter 6, I’ll return to this issue to consider ways in which it may be sensible to put in place policies that allow such continuing smokers to access non-combustible forms of nicotine under carefully regulated circumstances, while ensuring we do more to implement evidence-based, population-level measures that we know will reduce smoking, and do all we can to minimise the uptake of vaping by those who don’t smoke (especially teenagers).

Spontaneous, unplanned quitting vs stages of change progression

Anyone working in public health since the mid-1980s who has opened a research journal in health promotion or attended a conference where health-related behaviour change is being discussed will have been unable to avoid encountering the “Stages of Change” (SOC) or “Transtheoretical” Model of behaviour change. This model posits that there are five stages at which any person with a chronic behaviour pattern like smoking, being physically inactive or having a poor diet will currently be located. The model holds that individuals move through the stages in sequence (precontemplation, preparation for change, taking action, maintenance of the change and termination) (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983).

Adherents of the model argue that understanding which stage a person is currently at allows the tailoring of interventions and support to maximise further progression through to the termination stage.

There has been no other model which has gained anything like as broad adherence among researchers of health-related behaviour, particularly when it comes to smoking cessation. In 2005 the then editor-in-chief of Addiction, Robert West, located 540 papers in PubMed for the search string “stages of change”: 170 were about smoking, 60 on alcohol, seven on cocaine and two on heroin or opiates. However, West wrote a memorably scathing editorial calling for the model to be “put to rest” (West 2005). He summarised a large number of failings in the model, with perhaps the largest being what might be cruelly called the “No shit, Sherlock!” criticism that the theory was an unhelpful description of the obvious:

that individuals who are thinking of changing their behaviour are more likely to try to do so than those who are not, or that individuals who are in the process of trying to change are more likely to change than those who are just thinking about it … it is simply a statement of the obvious: people who want to plan to do something are obviously more likely to try to do it; and people who try to do something are more likely to succeed than those who do not.

West went further, describing the model as “little more than a security blanket for researchers and clinicians … the seemingly scientific style of the assessment tool gives the impression that some form of diagnosis is being made from which a treatment plan can be devised. It gives the appearance of rigour”.

“Tailoring” treatment for individuals after rigorous assessment of the stage they are at holds out the promise of greater precision in efforts to help smokers quit and so is understandably attractive to those yearning for the holy grail of much more effective approaches to cessation. But there’s just a slight problem here: a 2003 systematic review comparing stop-smoking interventions designed using the SOC approach with non-tailored treatments found no benefit over those that were based on the model (Riemsma, Pattenden et al. 2003).

Perhaps the most important limitation of the SOC model is its silence on “how people can change with apparent suddenness, even in response to small triggers” (West 2005). Across the many years I edited Tobacco Control, we received many papers which were often simple descriptive studies about the distribution of smokers in different settings across the stages of change. The senior editorial team would roll our eyes at the plodding regularity of the PhD industry churning these out.

In 2005, we published a refreshingly original short paper from a Canadian general practitioner, Lynn Larabie from Kingston, Ontario. She had noted the dominance of using “planned” approaches to quitting in clinical guidelines encouraging HCPs to assist smokers to quit. But Larabie had gained a strong clinical impression that many quit attempts, including successful ones, were anything but planned.

She interviewed 146 of her patients who had smoked more than five cigarettes a day for at least six months and had made at least one serious quit attempt. She found that just over half (51.6%) of quit attempts were described as being unplanned or spontaneous, and that these were more common in ex-smokers than those who had relapsed (Larabie 2005). In other words, those who quit without planning to do so seemed to quit for longer than those who planned it all out.

There is mixed evidence on whether planning or “spur of the moment” quitting decisions are associated with different quitting success down the track. West and Sohal, noting that Larabie’s study was the first of its kind, reported on findings from interviews with 918 English smokers who had made a serious quit attempt and 996 ex-smokers (West and Sohal 2006). They found that:

48.6% of smokers reported that their most recent quit attempt was put into effect immediately the decision to quit was made. Unplanned quit attempts were more likely to succeed for at least six months: among respondents who had made a quit attempt between six months and five years previously the odds of success were 2.6 times higher in unplanned attempts than in planned attempts; in quit attempts made 6–12 months previously the corresponding figure was 2.5.

These findings stimulated them to propose “A model of the process of change based on ‘catastrophe theory’ … in which smokers have varying levels of motivational ‘tension’ to stop and then ‘triggers’ in the environment result in a switch in motivational state. If that switch involves immediate renunciation of cigarettes, this can signal a more complete transformation than if it involves a plan to quit at some future point.” I’ll return to this idea in Chapter 8 where I’ll look at the importance of making quit attempts, rather than delaying them because of notions of it not being the “right time” to do so.

In 2010, a paper from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country study (Canada, US, UK and Australia) found those who reported quitting on the day they decided to do so, and those who delayed attempting to quit for a week or more had comparable six-month abstinence (Cooper, Borland et al. 2010).

A US study of 900 smokers and 800 ex-smokers recruited from a market research database were asked online about the planning involved in their most recent attempt. Just below 40% said that their most recent quit attempt involved no pre-planning (smokers: 29.5%; ex-smokers: 52.4%). Again as Larabie had found, the odds of a “spontaneous” quit attempt lasting for 6 months or longer were twice that of attempts which were pre-planned (71.7% vs. 45.6%) (Ferguson, Shiffman et al. 2009).

This paper contained a fascinating example of what can happen when researchers appear to not like the findings of their own work. All authors of this paper made declarations of support from the pharmaceutical industry and noted: “Given the evidence that use of medication can double success rates, it is surprising that even without this assistance unplanned quitters were more likely to be successful. [my emphasis] It seems important to find ways to combine the favorable prognosis of unplanned quit attempts with the benefit of medication, for example, by ensuring easy, rapid access to medication.”

So, unplanned, unassisted smokers did better than those who were assisted with medication, but the authors still felt compelled to try to convince such smokers to use medication anyway. They also suggested the removal of barriers to NRT sale such as prescription-only or pharmacy-only status, failing to note that these barriers had already been removed in the USA where the study took place. The “surprise” expressed by the authors of this paper seems revelatory of the myopic hold that assisted smoking cessation can have on the population-wide picture of how people quit.

Understanding that smokers can and do make sudden and often successful quit attempts should invite a lot of curiosity in tobacco control circles about the possibility that there could be potent triggers which are more likely to ignite quit attempts in smokers. In Chapter 8, I’ll explore what we know about such triggers that have been used in mass media campaigns to stimulate quit attempts.

How difficult is it to quit smoking?

Another major platform of the “don’t try to quit cold turkey” mantra is the claim that most smokers find quitting extremely difficult. There are, of course, many smokers who do find it very hard to quit. These smokers are a much-studied group, not least because those with intense interests in selling them medications and offering professional help see them as their customer base and so they often gather intelligence about how they might best succeed in convincing them to not go it alone. Here, you’d imagine an obvious thing to do would be to study former smokers who had permanently succeeded in quitting with the goal of seeing if there were important lessons that might be used to inspire and help those trying to quit. On the rare occasions when ex-smokers have been asked about their recollections of how difficult it was to quit, we have seen distinctly myth-busting data.

Very early in my career in 1983 I read a 151-page report, Smoking attitudes and behaviour, by English researchers Alan Marsh and Jil Matheson and produced by the British government’s Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (Marsh and Matheson 1983). The report, which is today very difficult to obtain (I found it in the US Truth Tobacco Industry Documents digital collection) was based on data obtained from 1,300 non-smokers and 2,700 smokers in Britain. They asked the respondents two questions:

- Would you say you found giving up smoking: (choose one) very difficult/fairly difficult/not at all difficult

- Was giving up (choose one): harder than expected/the same as expected/easier than expected

Here is what they found:

Nineteen percent of ex-smokers say they found their effort to quit “very difficult”, 27% agreed it was “fairly difficult” while a narrow majority, 53% said they found it “not at all difficult” to give up smoking. It might be said that this result supports the view that once smokers make up their minds, the effort to stop is not as great as it is supposed to be … 15% found it “harder than they expected” to give up smoking, 38% found it much as they had expected while 41% found it, as best they could recall, actually easier than they expected.

Importantly, Marsh and Matheson noted that “these figures are derived from those who, however modest the length of their achievement so far, have succeeded. The majority of triers who found it ‘impossible’ have removed themselves from the count by resuming their habit”.

Their report provides a cross-tabulated table of answers to the two questions shown above. They commented here that “the results suggest that smokers who found giving up difficult, and more difficult than they imagined it would be, are quite rare among the ex-smokers (16%). About six out of every ten of these ex-smokers say either they found the effort less difficult than they expected or that they had expected little difficulty and had experienced none”. They also noted that:

It seems that only one factor determined how hard or easy a time our ex-smokers had in giving up smoking and that is the number of cigarettes they were smoking each day when they stopped. Those smoking 10 a day or less had little difficulty with three quarters of them saying they found it “not at all difficult”. Those whose former daily intake fell into the 11–20 range found more difficulty with 22% saying they found it “very difficult” and among those who gave up an even heavier habit this figure rises to 31%. Interestingly though, above 10 a day, the proportions saying “not at all difficult” remain unchanged so that among those giving up a habit of more than 30 a day, still nearly half of them (47%) say they found it “not at all difficult” to abandon a level of consumption popularly associated with an extreme and compulsive dependence. That is to say, leaving aside the lightest smokers, someone abandoning a really heavy daily consumption will be just as likely to say they found the effort “not at all difficult” as someone smoking, say, 15 or 20 a day but if they do find it at all difficult they are more likely to find it “very difficult” than will the more moderate smoker.

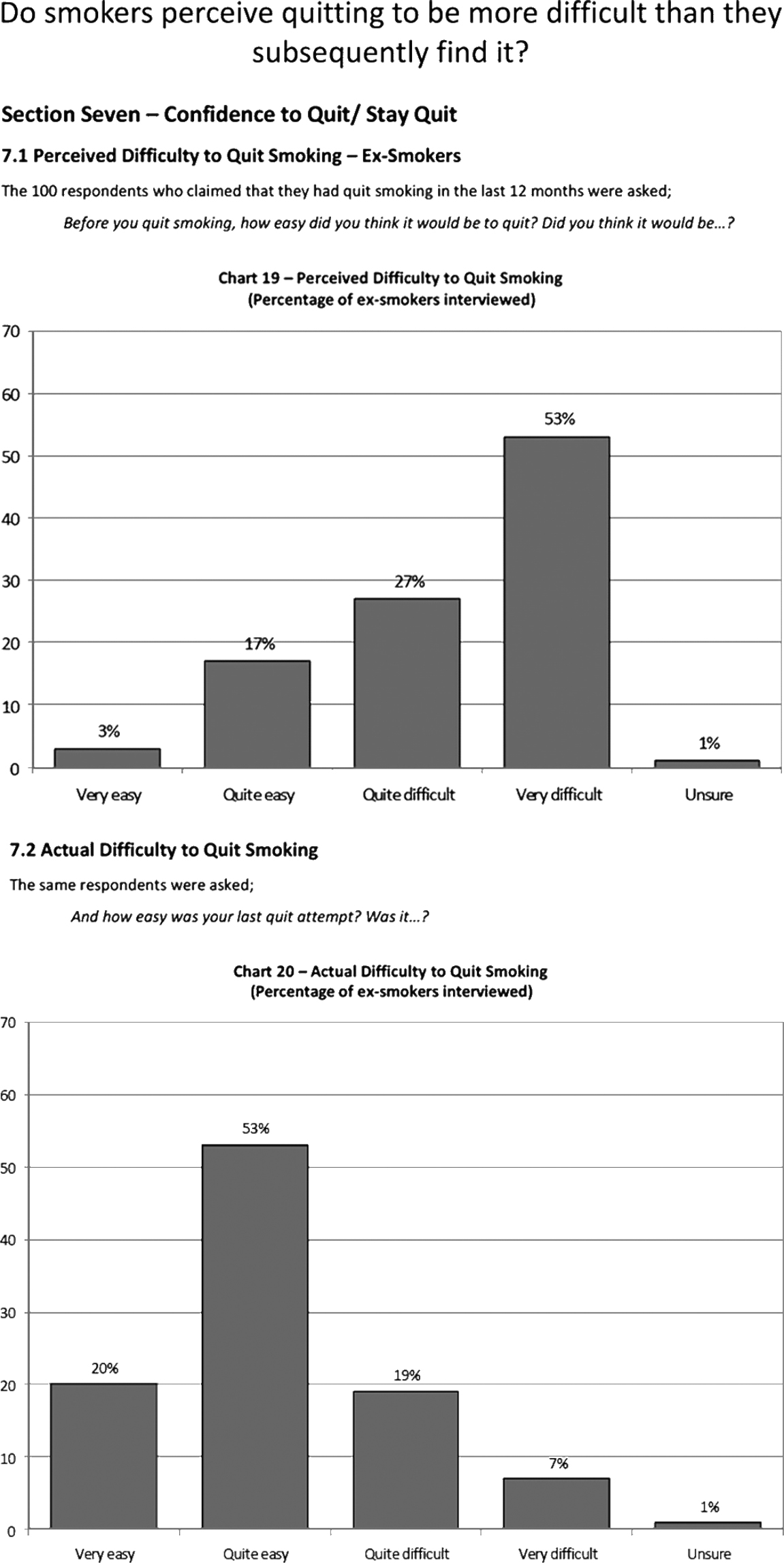

In the years since that report was published I have rarely seen other studies also ask questions similar to those of Marsh and Matheson. A couple of exceptions were a 2012 Tasmanian report (see Figure 5.5) reporting on the large differences between perceived and actual experienced difficulty in quitting and an unpublished paper reporting on Israeli military recruits. The majority (80%) of respondents felt that it was going to be difficult to quit smoking. However, the respondents’ final quit attempt was not as difficult as first thought, with 73% reporting that it was “quite easy” or “very easy”.

The Israeli study (Vered, Kedem et al. 2016) reported on all 1,574 ex-smokers in the Israeli Defence Force undergoing periodic medical examinations between September 2013 and June 2015. The great majority (83.4%) reported quitting unassisted. Cessation was reported as harder/much harder than expected by only 7.1%, easier/much easier than expected by 50%, and as expected by 42.8%. As with the research described earlier, those who reduced smoking gradually before cessation were significantly more likely to report difficulty than those who stopped abruptly.

Figure 5.5 Perceived difficulty of quitting reported by Tasmanian ex-smokers, 2012. Source: Quit Tasmania 2012.

Again, it is important to emphasise that ex-smokers have all successfully quit (for whatever length of time). We can assume that many of those who tried but relapsed would be likely to describe their experience as difficult (although some may have found it easy to quit but were tempted back into smoking after some time by lack of resolve to stay quit, rather than by finding the actual quitting experience impossibly hard).

Two things here are notable. First, that in these striking data about many ex-smokers finding the quitting experience less traumatic than expected, we rarely (if ever) hear comments or see campaigns from those in tobacco control discussing or highlighting this. We very seldom hear any efforts to de-bunk or leaven the “it’s very, very hard to quit smoking” meme by pointing out that many ex-smokers were pleasantly surprised that quitting was not as tortuous as they expected. This good news story might be very motivating to some contemplating quitting but who hesitate because they have been deluged with horror stories and rarely hear alternative perspectives.

Second, given what the few rare studies which have asked ex-smokers these questions have found, it is remarkable that this issue is not routinely explored in studies of quitting. It is almost as if there is a collective “let’s not go there” agreement among researchers to avoid learning more about this. A narrative of quitting being almost always very difficult is less unsettling for those whose careers depend on assisting people to quit than one of “Hey, if you want to quit, you may be able to easily do it by yourself.”

The shunning and denigration of unassisted quitting

In 2003, the American Cancer Society (ACS) published US data from 2000 showing that 91.4% of US ex-smokers had “Quit ‘cold turkey’ or slowly decreased amount smoked” while 6.8% had “followed recommended therapy (drug therapy and/or counselling)”. For every smoker who had quit with “recommended therapy”, 13.4 had successfully quit by themselves (American Cancer Society 2003). The report noted that “An estimated 44.3 million adults (24.7 million men and 19.7 million women) in the United States were former smokers in 2000. In 2000, 48.8% of US adults who ever smoked cigarettes had stopped smoking.” Despite this massive ratio, the ACS report astonishingly said nothing whatsoever about this wherever-you-look, in-your-face phenomenon. Instead, across six pages it jumped into line with the established “you need help” orthodoxy and summarised the virtues of quitting with assistance.

When I spot such subversive unassisted quitting figures that seem to have quietly snuck into reports like these almost without comment or discussion, I try to imagine the conversations in the editorial writing groups who produced them. I wonder if they went something like this with the ACS report:

Report writer: Are you saying that we should keep it very quiet that millions of people have and still do quit unassisted?

Chair of writing group: Look, let’s acknowledge the data on unassisted quitting, but not dwell on it. I suggest one line in a table or a footnote in small print up the back of the report. Can I see a show of hands? … Good, done!

In 2019, two of the world’s most cited researchers in tobacco control, Judith Prochaska and Neil Benowitz, published a 23-page review with 233 references in Science Advances, titled “Current advances in research in treatment and recovery: nicotine addiction” (Prochaska and Benowitz 2019). They set out to “review current advances in research on nicotine addiction treatment and recovery, with a focus on conventional combustible cigarette use and evidence-based methods to treat smoking in adults”. It contained copiously referenced summaries of what is known about the efficacy and effectiveness of various pharmacotherapies, e-cigarettes, brief and intensive counselling, quitlines, mobile phone and internet technologies, and financial incentives. But nowhere in the entire article did it mention that the method that has produced by far the most ex-smokers well before and continuously since the 1960s has been unassisted cessation.

A similar review published in The Lancet in 2008 also gave unassisted cessation only cursory attention – a mere nine words in a nine-page review (“Although most smokers will give up on their own …”) (Hatsukami, Stead et al. 2008). It is common to see unassisted cessation framed as a challenge to be eroded by persuading more to use pharmacotherapies. For example: “Unfortunately, most smokers … fail to use evidence-based treatments to support their quit attempts” (Curry, Sporer et al. 2007). Prominent English physician John Britton wrote in The Lancet, “If there is a major failing in the UK approach, it is not that it has medicalised smoking, but that it has not done so enough” (Britton 2009).

Both the 2019 Prochaska and Benowitz and the 2008 Lancet reviews were written as information for those involved in tobacco treatment, but importantly also concerned recovery from nicotine dependency. With the majority of smokers “recovering” unaided from being smokers, the assumption that this unavoidable, large-scale and enduring phenomenon should have zero or negligible reference in reviews and guidelines on how to quit is seriously, remarkably and quite appallingly bizarre. Yet unassisted quitting is almost always ignored in cessation clinical guidelines written for health professionals on how they might best help their patients to quit. While the US National Center for Health Statistics routinely included a question on “cold turkey” cessation in its surveys between 1983 and 2000, it mysteriously disappeared in 2005 (National Center for Health Statistics 2008), despite unassisted cessation remaining the method used by most successful quitters (Shiffman, Brockwell et al. 2008).

If a smoker asked their doctor the perfectly sensible and understandable question, “How have most ex-smokers quit?”, failure to emphasise that most have always stopped unaided would be like explaining that most cyclists, roller skaters and surfboard riders have professional tuition rather than being self-taught in these skills, that most people who exercise do it under supervision of a trainer or in a class, that most entirely competent domestic cooks attended cooking classes and that most guitarists in thousands of the world’s bands were fully trained in music schools rather than being self-taught or having a few early lessons (Pierce and Chiareza no date).

I know of no campaigns and only rare health promotion messages that highlight the fact most ex-smokers quit unaided even though hundreds of millions have done and continue to do just that.

Drivers of the medicalisation of smoking cessation

In 2010, I published a paper with Ross MacKenzie in PLOS Medicine titled The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences (Chapman and MacKenzie 2010). We set out to test a broad hypothesis I had described in a short Lancet paper in 2009: The inverse impact law of smoking cessation (Chapman 2009). This posited that “the volume of research and effort devoted to professionally and pharmacologically mediated cessation is in inverse proportion to that examining how most ex-smokers actually quit. Research on cessation is dominated by ever more finely tuned accounts of how smokers can be encouraged to do anything but go it alone when trying to quit – exactly opposite of how a very large majority of ex-smokers succeeded.” We tested the hypotheses that support for research into unassisted cessation and non-pharmaceutical interventions is less common and that research on pharmaceutically mediated cessation is frequently conducted by researchers supported by pharmaceutical companies.

We searched Medline for “smoking cessation”, limiting results to English language original articles, meta-analyses, and reviews published in 2007 and 2008. We found 511 papers which were studies of cessation interventions. Of these, 467 (91.4%) reported the effects of assisted cessation and 44 (8.6%) described the impact of unassisted cessation. Of the studies describing assisted interventions, 52.9% involved pharmacotherapy and 47.1% non-drug interventions. Of the papers describing cessation trends, correlates, and predictors in populations, only 11% contained any data on unassisted cessation.

Of the 84 papers for which competing interest information was available, 48% of pharmacotherapy intervention studies and 10.3% of non-pharmacotherapy intervention studies had at least one author declaring support from a company manufacturing cessation products and/or research funding from such a company – but no unassisted cessation study did.

We argued that there are three main synergistic drivers of the research concentration on assisted cessation and its corollary, the neglect of research on the natural history of unassisted smoking cessation. These are: the dominance of interventionism in health science research; the increasing medicalisation and commodification of cessation; and the persistent, erroneous appeal of the “hardening” hypothesis, discussed earlier in this chapter.

The dominance of interventionism

Most tobacco control research is undertaken by individuals trained in positivist scientific traditions. As I described in Chapter 2, hierarchies of the quality of evidence give experimental evidence more importance than observational evidence (Rychetnik, Frommer et al. 2002); meta-analyses of RCTs are given the most weight. As I’ll develop more in Chapter 8, cessation studies that focus on discrete, easily quantifiable proximal variables, such as specific cessation interventions, provide “harder” causal evidence than those that focus on distal, complex and interactive influences which coalesce across a smoker’s lifetime to end in cessation. Specific cessation interventions are also more easily studied than the dynamics and determinants of cessation in whole populations (Chapman 1993). Experimental research focused on proximal relationships between specific interventions and cessation poses fewer confounding problems and sits more easily within the professional norms of scientific grant assessment environments, which are populated largely by scientists working within the positivist tradition.

The dominance of the experimental research paradigm is amplified by pharmaceutical industry support for drug trials. More than half the papers we found on assisted cessation were pharmaceutical studies and, unsurprisingly, these were much more likely than papers on non-pharmacological interventions to have industry-supported authors. Companies have an obvious interest in research about the use and efficacy of their products and less interest in supporting research into forms of cessation that compete with pharmacotherapy for the cessation market.

The availability of pharmaceutical industry research funding – often provided without the lengthy processes of open tender or independent peer review – can be highly attractive to researchers understandably intent on keeping their soft money funded teams employed. Furthermore, it is often observed that “research follows the money”, with scientists being drawn to well-funded research areas (Russo 2005). Researchers steeped in clinical backgrounds where medication is nearly always indicated as the way that health problems are resolved may self-select to seek funding. The large pool of research funding for pharmacotherapeutic cessation may cause researchers to gravitate toward such studies while those interested in the natural history of smoking cessation have to secure funding through highly competitive public grant schemes.

This greater availability of funding for certain sorts of research produces a distorted research emphasis on pharmacotherapy that, when combined with the industry’s formidable public relations and marketing abilities and direct-to-consumer advertising, concentrates both scientific and public discourse on cessation around assisted pharmacotherapy. Fortune Business Insights put the global NRT market value of NRT at US$2.81 billion for 2020, saying that the demand for NRT during the 2020 COVID pandemic grew 12.2% and was projected to increase to US$3.92 billion in 2028. Eighty percent of the global market was in North America and Europe, with 80% of market share held by two companies, GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson Inc (Fortune Business Insights 2021). Chantix™/Champix™ (varenicline) earned Pfizer US$918 million in revenue worldwide in 2020 (Pfizer Inc 2020).

With this sort of money swirling around, it comes as no surprise that messages about cessation frequently focus on drugs. An early study found the pharmaceutical industry placed more messages about quitting in front of smokers than any other source: in the USA, there were 10.37 pharmaceutical cessation advertisements per month but only 3.25 government and NGO cessation messages (Wakefield, Szczypka et al. 2005).

The medicalisation and commodification of cessation

Iconoclast Ivan Illich was one of the first to discuss the tendency toward the medicalisation of everyday life in a paper in the Journal of Medical Ethics in 1975 (Illich 1975). On 3 October 2021 a PubMed search for “medicalization or medicalisation” returned 581 papers in the peer-reviewed health and medical literature, with the first mention published in 1974. Many concerns previously perceived as normal human differences or problems have now been defined as tractable illnesses that can benefit from diagnosis and often lifetime drug taking (Conrad 1992, Deyo and Patrick 2005, Moynihan and Cassells 2005). These include shyness and sadness (Horwitz and Wakefield 2007, Lane 2007), tallness in girls (Rayner, Pyett et al. 2010), baldness in men (Jankowski and Frith 2021) and many, many more normal human differences and phases of life. Le Fanu has described galloping medicalisation as an iatrogenic catastrophe (Le Fanu 2018).

In 1975, Renaud wrote of the fundamental tendency of capitalism to “transform health needs into commodities … When the state intervenes to cope with some health-related problems, it is bound to act so as to further commodify health needs” (Renaud 1975). The pharmaceutical industry creed is that wherever possible, problems coming before physicians need to be pathologised as biomedical problems that need to be treated with medication. Tobacco use, like other substance use, has become increasingly pathologised as a treatable condition as knowledge about the neurobiology, genetics and pharmacology of addiction develops. The burgeoning commodification of smoking cessation by manufacturers of both effective and ineffective drugs seems to have induced a kind of professional amnesia in tobacco control circles about the many millions who quit in the decades before the dominance of the contemporary smoking cessation discourse by pharmacotherapy.

The NRT industry in particular has been well served by a plethora of studies which recommend an ever-expanding menu of ways and times to consume NRT. These include:

- NRT for light smokers (Rahmani, Veldhuizen et al. 2021).

- NRT for both “pre-quit” and “post-quit” (Lindson and Aveyard 2011, Przulj, Wehbe et al. 2019).

- Multiple, combination, dual-form NRT (Tulloch, Pipe et al. 2016).

- NRT long after stopping to prevent relapse (Agboola, McNeill et al. 2010).

One Pfizer-sponsored study examined the effect on quit attempts of varenicline when used by smokers with no immediate intention of quitting, suggesting that thinking may be circling the challenge of promoting pharmacotherapy even to those unmotivated to quit (Hughes, Rennard et al. 2011).

It appears that there is no smoker, regardless of how much or little they smoke, and regardless of whether they are not at the point of trying to quit, actively trying to do so or have long stopped smoking, for whom medication and especially NRT is not recommended. It is in the interests of that industry to persuade as many smokers as possible to use pharmaceutical aids for as long as possible.

All smokers should use NRT: a promotional case study

From December 2009 until February 2017, the transnational pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) published a website called Path2Quit, an online, interactive website designed to assist smokers to understand which pathway to quitting was optimal for their personal smoking profile. The website is available today on the Wayback Machine (GlaxoSmithKline 2009). The home screen showed three statements:

- Quitting is really hard.

- Different smokers need different solutions.

- Discover which path is right for you and start your journey on the right track.

GSK manufactures the Nicabate™ NRT brand. I decided to put the site to the test of what it would advise a light smoker, who’d never tried to quit smoking, who was not very addicted to nicotine and was confident of their ability to quit.

Figure 5.6 Screenshot of GSK’s Path2Quit web promotion, Australia, 2009–17.

A signpost (Figure 5.6) showed three different potential pathways which by clicking “start”, smokers would discover the best route for them. The next screen asked, “Have you ever tried to quit smoking?” with four options (never, once, 2–4 times and 5-plus). I clicked “never”. The next screen asked, “How many cigarettes do you smoke a day?” The options were less than 10, 10–14, 15–19 and 20-plus. I clicked “less than 10”. The third screen fished for nicotine dependence, asking, “How long after waiting do you reach for your first cigarette?” (“less than 30 minutes or 30 minutes or more”) I clicked the less urgent time.

The next three screens probed confidence and preferred pace in quitting, asking whether a smoker was ready to quit now and give up all cigarettes immediately, was anxious about quitting altogether suddenly, or preferred to “take one step at a time” (I opted for the first to suggest that I believed in crash-tackling the nicotine demon rather than trying to slowly tame it.) Another asked cryptically, did I “want to actively manage my own cravings” or “I want a product that will manage my cravings for me”. Again, I clicked the first to signal that here was a smoker confident they could handle their way out of smoking.

The next and penultimate screen had: “Based on your answers, the product we believe will give you the best chance of success is … ”) and one more click revealed the answer. Surprise! I should use a Nicabate™ patch 24 hours a day, even though I was a light smoker who’d never tried quitting before, was probably not nicotine dependent and had a sleeves-rolled-up, confident attitude to quitting.

I then experimented with different responses to the questions and – you guessed it – it didn’t matter which option I clicked, every combination of responses recommended that I use Nicabate™. All Path2Quit directions amazingly lead to the same destination: using NRT. Predictably, the website never mentioned quitting unassisted.

At the time that this website was published, the Cochrane systematic review stated, “Most of the studies [on the efficacy of NRT] were performed on people smoking more than 15 cigarettes a day” and demonstrated “no benefit for using patches beyond 8 weeks”.

Attacks on my work on unassisted cessation: perspectives from the woods and the trees

Between 2010 and 2013, my work with other authors on unassisted cessation (Chapman 2009, Chapman and MacKenzie 2010, Chapman and Wakefield 2013) was subjected to five extended attacks, mostly by doyens of the English smoking-cessation research community who had all been long-standing researchers and public advocates for assisted cessation. Most, but not all, had declared histories of support from pharmaceutical companies with skin in the smoking-cessation game.

The first cab off the rank was a gratuitous swipe by English smoking-cessation researcher John Stapleton in a commentary on Banham & Gilbody’s The scandal of smoking and mental illness where he wrote, “There are some who argue that the sort of effective help to stop smoking described in this issue of Addiction and in other reviews should be denied people with mental illness, and all smokers. They argue that viewing tobacco dependence as a disorder and helping smokers individually in the way caring societies normally help those with health-related disorders is unnecessary and counter-productive” (Stapleton 2010). Our PLOS paper (Chapman and MacKenzie 2010) was cited in support of this claim.

We set fire to this straw-man argument (Chapman and MacKenzie 2012), noting that our paper made no reference at all to smokers with mental illness, contained no discussion about smoking as a disorder and emphatically said nothing about denying treatment to anyone. One of the final statements in our paper was that “NRT, other prescribed pharmaceuticals, and professional counselling or support also help many smokers, but are certainly not necessary for quitting” (see more on this in Chapter 8).

M’lud, the accused is charged with spreading four “fallacies”

The next salvo was fired in an editorial in Addiction (Should smokers be offered assistance with stopping?), signed by nine authors, led by the journal’s editor-in-chief, Robert West (West, McNeill et al. 2010). The editorial was translated into French, Spanish and Mandarin and displayed prominently for months on the homepage of the pharmaceutical-industry-sponsored website, www.treatobacco.net. It seemed that the English assisted-cessation officers’ mess had decided that our upstart arguments needed to be jumped on from a great height. The editorial set out four “fallacies” they believed we were promoting. Triumphantly, they declared that after the application of their blowtorch, these fallacies were now “out of the way”. We were not invited to respond to the editorial, despite this being customary and common in most serious journals, including Addiction.

They claimed that the first fallacy illustrated that we “misunderstood arithmetic” because anyone numerate could surely see that if 5% of 1000 smokers quit without assistance, the resultant 50 ex-smokers clearly were an inferior outcome to a 20% success rate in 100 (i.e. 20) assisted smokers quitting. They wrote, “So in this example, more than twice as many smokers will have stopped without assistance as with it, despite the fact that doing it this way was four times less effective.”

The authors’ supercilious reasoning here of course depended entirely on their criterion for success: higher quitting success rates, not higher quitting numbers. As I discussed in Chapter 4, no evaluation of the English smoking-cessation special services has ever shown that their contribution to reducing smoking prevalence has been anything more than minor and a pale shadow of the numbers who have quit decade after decade without ever going near a smoking-cessation professional or using medication. So, if the goal here is all about pointing to impressive quit rates in cessation settings, which, in aggregate, barely caused a blip in national smoking prevalence, then we wave the white flag. But of course in the goal of increasing national smoking cessation, the proof of the pudding is not success rates, but total success numbers. So we kept our white flag furled.

Our second egregious fallacy was to argue that denigration of unassisted cessation as inferior and something to be actively advised against might actually cause many hearing those messages to do just what was being advised: to not try to quit on their own. That is plainly the intent of any message saying, “Do not go cold turkey”. Here the authors argued that in a nation where assisted cessation was strongly promoted and cold turkey disparaged, there was no evidence of smokers reducing their quit attempts. Perhaps not. But hundreds of millions of ex-smokers globally know a thing or two about successful unassisted quitting. Yet they are perpetually disenfranchised by professionals, and hear and read constantly that the way they actually quit is not recommended and not “evidence based”. But the evidence is all around us in plain sight. There are many experienced quitters out there who possess wisdom, but it is mostly ignored.

Self-change scholars Harald Klingemann and Mark and Linda Sobell are explicit about the importance of taking self-changers far more seriously. They note that public awareness of self-change dominating cessation of problem behaviours is often limited and argue that “disseminating knowledge about the prevalence of self-change could be a type of intervention itself” (Klingemann, Sobell et al. 2010). What if such news actually empowered people to try to change?

Many critics start from the premise that unassisted cessation attempts are far less successful than those assisted by professionals and/or medication, and by reason of that, it would be wrong-headed if people are led to try to stop using less effective methods when they would have chosen more effective ones.

To this I would say that the bottom line on “more effective” is far less sanguine than a good deal of the messages that are sent to smokers, which are mostly based on clinical trial outcomes with all the problems I discussed in Chapter 2. The group-think here is “Let’s all keep quiet about this and jump hard on those who give this subversive message any major oxygen.” Hustlers for assisted cessation write about unassisted cessation as if it is hopeless, a shocking recipe for failure. How perplexing then that for decades it has continued to deliver so many more successes each year than combined yields from the anointed “evidence-based” methods backed by assisted-cessation advocates.

Those who argue this believe they should never compromise and recommend anything but the very best. I’m reminded of the adage that the perfect should not be the enemy of the good. On several occasions I’d been taunted by critics suggesting that my logic would require that I would not recommend antibiotics for the treatment of pneumonia, as if there were obvious parallels between being ill with pneumonia and being a smoker who wanted to stop. But there are important differences between the two which make the comparison very misleading. When you have pneumonia it needs to be urgently treated. Before the advent of antibiotics, pneumonia killed very large numbers of infected people often quite quickly, particularly the aged. The same cannot be said about untreated smoking: the great majority of smokers who keep smoking will not die today, this week, this month or even this year from a disease caused by smoking. The health risks of smoking accumulate over decades, and while many thousands of smokers die every day around the world from smoking-caused and exacerbated diseases, no one argues that it was the recent cigarettes they smoked which killed them or that, as often occurs with untreated pneumonia, death occurs quickly. And that’s before we even get to questions I’ve looked at throughout this book about whether the real-world effectiveness of stop smoking medications are in any way comparable to the value of taking antibiotics for pneumonia.

In 2010, three papers addressing the stubborn problem of unacceptably low rates of US smokers using assisted cessation were published back-to-back in a special supplement of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (Abrams, Graham et al. 2010, Levy, Graham et al. 2010, Levy, Mabry et al. 2010). These detailed papers explored every conceivable way that the intransigence of American smokers in resisting the promises of medications and professional supervision might be eroded. One paper modelled the huge population-wide health benefits that would follow if this came to pass. It all had a very familiar ring to it.

But it’s plainly the case, with the promotion of assisted cessation having now been on full throttle since the late 1980s with pharmaceutical industry general practitioner promotions, pharmacy in-store promotions and displays, massive direct-to-consumer advertising saying don’t try to do it alone, and endless efforts to reduce barriers to health care professionals engaging more in identifying and assisting smokers that the assisted-cessation camp has fired off its full arsenal of strategies, many, many times. Does anyone seriously imagine that there are big rabbits still left in hats that will see a far bigger proportion of smokers want to avail themselves of cessation services and medications than has happened so far? There is no evidence from anywhere for this hope.

The West group’s third alleged fallacy we were spreading was that RCT evidence is not mirrored in real-world outcomes (for all the reasons set out in Chapter 2) and that longitudinal cohort studies provide greater guidance on how well different cessation methods actually perform when used in conditions that post-RCTs, they will always be used in. The West-led nine authors’ counter arguments here argued that recall bias plagues such studies and that confounders like nicotine dependence levels are often uncontrolled in cohort studies. Recall bias is certainly an issue when it comes to recall of quit attempts (as I discussed in Chapter 2) but it is not a major problem when recall of final, successful quit attempts is the key outcome of interest. Smokers remember how they finally quit, but often don’t recall failed quit attempts that may be little more than gestures rather than serious tries.

In Chapter 2, I also discussed the peculiar sleight-of-hand argument often used by assisted-cessation stalwarts concerning “indication bias”. Here, when trying to explain why smoking-cessation medications and NRT often do less well than unassisted quitting in real-world studies, it’s argued that no one should be surprised that heavy smokers fare badly when trying to quit. The sleight of hand here is, of course, that it’s the more dependent smokers who are typically highlighted as the very smokers who most need assistance to quit. So they are especially urged to use medications. But when data show they often do worse than unassisted quitters, the post hoc explanation then dragooned into explanation is that we should not have expected them to succeed because of the very same reason they were recommended to be used.

The West nine authors’ gotcha moment then came by citing one evaluation (Ferguson, Bauld et al. 2005) which showed assisted quitters did better than typical unassisted quitters. Chapter 3 of this book discussed a good deal more evidence inconvenient to that one citation.

Our fourth fallacy was apparently to argue that mass-media campaigns are a better investment than setting up national networks of smoking-cessation centres. The latter attract very small percentages of all smokers while well-funded, mass-reach campaigns find and influence huge numbers of the whole population and, as I will discuss in Chapter 8, motivate many smokers to make quit attempts.

The editorialists insisted that comparing the respective contributions of stop smoking services and media campaigns was a “false dichotomy” because they worked synergistically, and along with policy initiatives like tax rises and smoke-free public areas, together were driving down smoking across the population. But this stock response hides the evidence I described in Chapter 4 which shows that the attributed contribution made by English quit-smoking services to national falls in smoking prevalence was very small. Expenditure on media campaigns on smoking in England between June 2008 and February 2016 averaged £5.58 million per year (Kuipers, Beard et al. 2018), while that allocated to cessation services between 1999 and 2006 averaged £30.53 million per year (McNeill, Raw et al. 2005). English local health authorities in 2014–15 and 2017–18 allocated 89.8% of expenditure on total tobacco control to specialised stop-smoking services (£121.2m in 2014–15 and £85.2 (Action on Smoking and Health 2019). Clearly, important questions need to be asked about the opportunity costs of allocating such disproportionate expenditure to methods of increasing cessation when the track record of cessation services is and is realistically destined to remain small.

“Unsupported by the facts”

On 13 October 2011 a third damp squib salvo was fired by Jacques Le Houezec, a French consultant to pharmaceutical companies manufacturing smoking-cessation treatments, who posted to the now-defunct global tobacco control listserv, Globalink. Signed by ten senior researchers in tobacco control, eight of whom were English, and seven of whom signed the 2010 Addiction editorial, the post read:

It is regrettable that Professor Chapman persists with the fallacies dealt with in the editorial by West and colleagues (West, McNeill et al. 2010). The editorial is open access and points out that the optimum approach to cessation is to encourage smokers each time they try to stop to use the most effective method available to them. Unaided cessation has been found in clinical trials, clinical observational studies and population level studies to be less effective than using either pharmacotherapy under supervision or behavioural support or ideally a combination of the two. To argue that an approach to quitting is the best one because it is the most common is illogical and unsupported by the facts.

John Britton, Professor of Epidemiology and Director, UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies, University of Nottingham

Linda Bauld, Professor of Socio-Management, University of Stirling

Dorothy Hatsukami, Forster Family Professor in Cancer Prevention, University of Minnesota

Martin Jarvis, Emeritus Professor of Health Psychology, University College London

Jacques Le Houezec, Special Lecturer, University of Nottingham, Manager www.treatobacco.net

Ann McNeill, Professor of Health Policy, University of Nottingham

Hayden McRobbie, Reader in Public Health Interventions, Queen Mary University of London

Martin Raw, Special Lecturer, University of Nottingham

John Stapleton, Senior Research Associate, University College London

Robert West, Professor of Health Psychology, University College London

I replied to the listserv the next day:

This debate is ultimately a debate between those who are fixated on success rates and those who are more interested in success numbers; a debate between those with orientations that are inescapably clinical and those whose ultimate criteria for “the best” is population focused; between those who look at the net cessation yield of various cessation modalities in a population, and see what is obvious (unassisted remains not only more preferred but produces far more successes), and those who get more excited by success rates of some of those modalities but seem blind to their continuing failure to collectively deliver more successes.

Advocates for assisted cessation have had something like 30 years to show that they can persuade smokers to take drugs, call quitlines, attend clinics and abandon silly notions that they might succeed in quitting without all this. Despite the billions of dollars that must have been spent globally in this time on advertising to physicians, direct-to-consumers, in continuing medical education, attracting government subsidies and funding consultants (like most of the signatories), it remains the case that most who quit today do not quit with these forms of assistance. None of these signatories deny this. They instead denigrate it as “illogical” that smokers should ever be told this or that it is undeniably, potentially empowering good news.

They use lame analogies with other forms of pharmacotherapy for other illnesses, trying to paint a spurious equivalence between the treatment of diseases which seldom improve without drugs, and smoking, where we know that most ex-smokers have always stopped without drugs or other assistance.

If the final test of “optimum” cessation policy is the decline of smoking in whole populations and the “how” stories told by most of those who stopped, then we can look at the evidence. In Australia, we today [2010] have 15.1% of 14+ adults smoking daily – and significantly less than this in two states. Both prevalence and cigarettes per day have never been lower and are showing no signs of slowing. We have a handful of UK-style clinics here which collectively contribute an insignificantly small number of ex-smokers to the number who quit each year. What’s the score in the UK, the world’s assisted cessation capital? Isn’t the tail trying to wag the dog?

My final question about smoking prevalence in England in 2010 was rhetorical. In 2010, Australian smoking prevalence (including even very occasional use, and including all forms of combustible tobacco) was 18% (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020c). In England it was 20% for cigarettes and roll-your-own cigarettes only (National Statistics 2012). The most common “lame analogy” I was referring to was about the best way to treat pneumonia, discussed earlier.

A fourth attack

A fourth smackdown appeared in 2013 in a short paper in Nicotine & Tobacco Research journal (Raupach, West et al. 2013), again including Robert West among the authors. They wrote:

One argument used by these authors is that unaided quit attempts are effective because many former smokers report to have quit without help. This argument is based on a logical fallacy, which ought to be obvious, but clearly is not.

They then provided data from the Smoking in England study showing that smokers who had used assisted approaches to quitting had the highest rates of successful quitting at their last quit attempt, while those who had tried to quit unassisted had the lowest rates. From this, they argued – yet again – we had got things completely around the wrong way and were blind to our most egregious, irresponsible error. It was obvious all that mattered in answering any question about “success” in quitting was to use a head-to-head comparison of assisted methods and unassisted methods and see who fared best in terms of rates of success. So if we took 100 smokers using assistance and 100 not using assistance, we could see which approach yielded the highest success rate at the most recent quit attempt. What more was needed to answer the question? It was that simple and we couldn’t get our limited heads around that, apparently.

We replied, suggesting that there was a myopic “not seeing the woods for the trees” problem with their critique (Chapman and MacKenzie 2013). We wrote:

Those with a clinical focus are often understandably preoccupied with the question of which smoking cessation approaches are most efficacious. If assisted approaches triumph in such comparisons, the task then becomes how to increase use of such assistance in significant proportions of the smoking population. For nearly 30 years there has been a constant refrain from proponents of assisted cessation that they just need to work better to improve desultory participation in clinics, premature abandonment of medication, low single-digit percentages of smokers ever calling quitlines and stagnant levels of sub-optimal interventions by primary care workers. This Sisyphean task is seemingly endless, but meanwhile the hardening hypothesis appears to be largely discredited and rogue nations like Australia which fail to heed the English wisdom continue to be perplexed about the virulence of the criticism directed at our recalcitrance while smoking prevalence continues to fall faster than theirs.

By contrast, those with a “woods” orientation start with a different question which combines effectiveness with reach or participation to answer the question, “What approaches to tobacco control reduce smoking most in a population?”

Population-focused analysts can see great merit in approaches which might not have the highest head-to-head efficacy, but which have far higher consumer acceptance and so greater net population impact. They are less concerned with failure rates than with net success numbers.

Raupauch, West and Brown epitomised the myopic “trees” orientation when they boasted that England has “probably the highest assisted quitting rate anywhere in the world” before turning to the comparative failure rate of those who try to quit unassisted. But the profane rhinoceros in the room which apparently must never be acknowledged let alone commended by assisted-cessation proponents (who are very often supported by the pharmaceutical industry), is that despite all this “failure”, unassisted cessation unarguably is and always has been the approach used by the large majority of people who have quit smoking successfully. It is undeniably the “most” successful strategy if your frame of reference is actual population impact. Our heresy has been to point this out and to suggest that it is in fact an instructive, good news message, not one that should be deemphasized or attract denigrating campaign slogans like “Don’t go cold turkey”. Globally, hundreds of millions of unassisted ex-smokers’ experiences testify to this, something which did not prevent a 2008 English NHS poster containing the flagrant misinformation that “There are some people who can go cold turkey and stop. But there aren’t many of them” (see Figure 5.1).

Quitting “attempts” are often half-hearted. So much so, that unassisted attempts are frequently not even recalled (Kasza, Hyland et al. 2013). But a preoccupation with failures in such attempts seems to blind some to the net effect of all this failure: that despite it, unassisted cessation delivers nearly twice as many ex-smokers as all other approaches combined (Shiffman, Brockwell et al. 2008).

Finally, in a candidate for a “pots calling kettles black” award, Raupauch, West and Brown claimed that we selectively cited observational studies that “do not show benefit for treatment”. But they then selectively cited studies that support their position. Again, their words mischaracterised what such studies show: treatment does benefit many, but in “real-life”, this can be actually less than the unassisted success rate because of indication bias, where more severely dependent smokers with a higher probability of relapse receive a treatment and less dependent smokers do not.

It is “unethical” to not promote treatment for smoking in low-income nations

A fifth attack landed in 2011 in the journal Public Health Ethics (Bitton and Eyal 2011). Two authors mounted a lengthy critique (titled “Too poor to treat? The complex ethics of cost-effective tobacco policy in the developing world”) that Ross MacKenzie and I, in our 2010 PLOS Med paper, were condemning smokers in low-income nations to lack of access to NRT and quit-smoking medicines.

We published a reply (Chapman and MacKenzie 2012) to their paper. In it, we rehearsed many of the arguments in this book but focused on the twin issues of the dismal real-world performance of smoking-cessation medications and the stratospheric cost of these products in nations where incomes are very low.

Warner and Mackay have argued that “We can have our cake and eat it too”, stating that further resources and emphasis should be given to treating tobacco dependence as well as to public-health, population-focused approaches to promoting cessation (Warner and Mackay 2008). Wealthy nations arguably can afford both approaches, although as I wrote earlier, there are few if any drugs which attract the epithet “successful” when 90% or higher of those who take them still have the problem a year after treatment.

However, today’s largest smoker populations are nations with massive populations on low incomes for whom quit-smoking aids are prohibitively expensive. This was emphasised in a 2011 survey of tobacco treatment across 121 nations (Pine-Abata, McNeill et al. 2013), interestingly co-authored by Asaf Bitton, the first author on the “Too poor to treat?” paper questioning the ethics of smoking treatments being often unavailable in low-income nations.

In the 2011 survey, just 19 of the 121 respondents providing information on the provision of different elements of smoking-cessation support in their nations were from low-income nations. Twelve of the 19 said their nations “had no specialized treatment at all” for smokers; one had a quitline; and none had nationwide tobacco dependence treatment services. The authors concluded, “A third of countries had no specialized treatment services at all. Availability of medications was limited, and they were frequently perceived to be unaffordable … Overall, tobacco cessation support and treatment appear to be a low priority for most Parties, especially lower-income countries … Unfortunately, most countries’ health care systems do not cover the cost of tobacco cessation medications and in some countries even NRT, one of the less expensive medications, is far more expensive than cigarettes.”

Ten years on from this assessment, I’ve seen no updated data suggesting that much has changed. A packet of 210 pieces of 4 mg Nicorette™ gum was selling from an Indonesian online pharmacy in November 2021 for 959,000 rupiah (A$90.13). Nicorette’s manufacturers suggest 20-a-day smokers wanting to quit should use 1–2 gums per hour, up to a maximum of 20 day. Assuming a smoker used 10 gums a day, then a month’s supply would cost A$128.76. With average monthly earnings for Indonesians in December 2020 being A$228, the average Indonesian would need to outlay 56% of their earnings on nicotine gum if they used it as recommended (CEIC 2022).

So in Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation, NRT is way out of the reach of all but the wealthy. NRT and prescribed medications would thus seem to be largely irrelevant to population-wide cessation goals in many low- and middle-income nations. Such nations emphatically cannot afford “both” and are often still struggling to fund basic primary health care, and public-health and sanitation infrastructures. Population-oriented, mass-reach tobacco control policy and programs are the exceptions in such nations. In my view, it would be a disaster for tobacco control progress if such nations were to be influenced to proliferate the labour-intensive UK-style models of assisted cessation I discussed in Chapter 4 before they implemented comprehensive and sustained population-focused cessation policies and programs. In most nations, tobacco control is in its nascent phase. Siphoning resources and scarce personnel into smoking-cessation strategies that reach relatively few and help even fewer would be grossly inequitable. And that is a serious ethical problem.

In summary, if most ex-smokers quit unaided and many as we have seen early in this chapter don’t find it too difficult to do so, this is a very important, empowering message that should be shouted from the rooftops to smokers instead of “You need help! Don’t try doing it alone!” It is a message that should be used to balance the overwhelming dominance of the pharmaceutical and vaping industry driven messaging about cessation: that most smokers will find it hard to quit and that most need assistance in the form of drugs or professional oversight to do it. What we get instead is widespread denigration of going cold turkey, a message plainly encouraged by Big Pharma which sees cold turkey as “the enemy”, as it was put to me once by a GSK executive. It is seriously depressing to see this situation persist year after year.

Why does Big Tobacco never attack assisted smoking cessation?

Finally, across my entire career I cannot recall a single instance of any tobacco company or “independent” astroturf group or sock puppet doing the industry’s bidding, which has ever launched an all-out attack on or even mildly criticised any smoking cessation treatment service, quitline or any of the other cessation approaches described in Chapter 4.

Even more telling is the seemingly bizarre involvement of the tobacco industry in actually running quit-smoking programs. McDaniel et al. summarised their motivations well in a 2017 paper (McDaniel, Lown et al. 2017) showing that these quit programs and other mundane corporate social responsibility gestures served wider purposes of:

enhancing the industry’s image and credibility (Apollonio and Malone 2010); marginalizing public health advocates (Landman, Ling et al. 2002); creating allies among policymakers and regulators (Landman, Ling et al. 2002); forestalling effective tobacco control legislation and preventing enforcement of existing tobacco control laws (Landman, Ling et al. 2002, Apollonio and Malone 2010); providing a litigation defense (Mandel, Bialous et al. 2006); and directing funds away from programs that work (e.g. those that directly confront the tobacco industry) and toward programs in which the industry could be a partner (Mandel, Bialous et al. 2006).

Article 5.3 of the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control concerns tobacco industry interference in tobacco control (Assunta and Dorotheo 2016). The history of industry interference has included trenchant attacks often lasting decades on policies, laws and regulations which threaten to seriously stimulate large-scale quitting, reducing the number of cigarettes smoked by continuing smokers, preventing uptake or denormalising smoking by expanding smoke-free public spaces. Some of the most sustained opposition has been levelled against tobacco tax rises, advertising and promotion bans, pack warnings (particularly graphic health warnings), plain packaging, smoke-free laws, point-of-sale display bans, ingredient disclosures and duty-free limits.

Hard-hitting mass-reach campaigns with substantial budgets have also been attacked. An early example of this was an attempt to stop a pioneering campaign operating on the North Coast of New South Wales. “All printed advertisements were suspended for 15 weeks from October 1979 (four months after the start of the antismoking campaign) after complaints to the Media Council of Australia by the three major tobacco manufacturers. One television commercial was also suspended pending a change in wording.” All of the complaints concerned issues of advertisements disparaging smoking (Egger, Fitzgerald et al. 1983).

Against all of this, the tobacco industry has never opposed or even criticised anything to do with assisting smokers to quit whether this be efforts by governments, health agencies or pharmaceutical companies. Its indifferent behaviour to these activities has been similar to its typical silence on school health education curricula about smoking, mandatory signs in shops about it being illegal to sell to children, and laws on minimum age of tobacco purchase. Indeed, it has often trumpeted its own corporate social responsibility efforts to dissuade children from smoking through initiatives it privately described as “a phony way to express sincerity [to governments about tobacco control] as we all know” (Assunta and Chapman 2004, Knight and Chapman 2004).

The tobacco industry’s reaction to policies that in any serious way threaten its bottom line (sales) has long been shorthanded in global tobacco control as the “scream test”. If the industry screams loudly in the media, in its lobbying of governments and in its efforts through the courts to stop, reverse or neuter tobacco control policies, this is an unfailing litmus test of its understanding of which policies are potent ways of reducing smoking. The corollary of this is that when it stays silent on any development, it understands these things are inconsequential. Its silence on quit-smoking treatments and services is deafening.