4

Animating cultural heritage knowledge through songs: Museums, archives, consultation and Tiwi music

Animating cultural heritage knowledge through songs

Download chapter 1 (PDF 2.6Mb)

Introduction

Ceremony [is how] young people start to learn about this singing and dancing – how you dance your own Dreaming dancing. All sort – like, you know, everyone has their own dancing from their grandfather, down to their fathers. That’s where we get that. It’s time for them to listen, to learn. It’s time now, never too late … Parlingarri [long ago]. Way back, from the past – and today. It’s a bit different. Parlingarri, old people used to have that knowledge – the words and the song written in their pungintaga [head], brain.

Jacinta Tipungwuti1

Throughout the twentieth century, intangible (recorded song and dance) and tangible (photographs, painted, carved and woven) Tiwi cultural items were collected by (non-Tiwi) observers, researchers and collectors. These often began as private collections, with many recordings of intangible culture making their way to public archives, while tangible culture ended up in museums and galleries. Oral and written evidence confirms that ceremony2 on the Tiwi Islands was discouraged and disapproved of, both passively and actively, by missionaries through the early- to mid-twentieth century and this had a marked impact on performed cultural practice. Senior Tiwi women and men have described their experiences of being brought up in the Catholic mission school, removed from family, ceremony and language. Current Tiwi Elders were leaders in reclaiming cultural rights and ownership through the 1970s and 1980s and have continued to dance ceremony, compose traditional song and create painted, carved and woven art3 while negotiating changing social and cultural motivations and pressures. Throughout the ebb and flow of these cultural, political and social shifts, the collected culture has remained in place, artificially separated into material and intangible culture. It is only through speaking with current Tiwi culture and knowledge holders that the interconnectedness of performance and artefact is now being added to the record.

This chapter deals with a series of consultations between Amanda Harris, Matt Poll, Genevieve Campbell, Jacinta Tipungwuti and additional Tiwi cultural custodians at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and at the Sydney University Museum Collection store in March 2019 during a visit to Sydney by a small group of Tiwi singers for a performance at the Seymour Centre4 and in follow-up discussions on the Tiwi Islands.5 The Tiwi custodians included Jacinta Tipungwuti, Regina Kantilla, Augusta Punguatji,6 Anthea Kerinaiua, Frances Therese Portaminni and Gregoriana Parker, who identify as members of the Strong Women’s Group, so named for their roles as cultural leaders and holders of song knowledge. They were accompanied by Francis Orsto, an emerging songman and authority of cultural practice. They (henceforth the Strong Women’s Group7) had travelled to prepare for a performance, and this context created an opportunity for active agency and rich engagement with the historical record of Tiwi culture held in the collections.

Ethnomusicologist Genevieve Campbell travelled with the Strong Women’s Group and participated in all the consultations. In this chapter, Campbell has contributed the broad context for understanding Tiwi historical collections and present interpretations in collaboration with Jacinta Tipungwuti as a representative of the group. Cultural historian Amanda Harris provided historical context for the audiovisual materials that were watched with the group and reflections on how they are viewed now and curator Matt Poll has documented the history of the Macleay Collections and reflections on the contemporary consultations.

Senior Tiwi woman Jacinta Tipungwuti had viewed the Macleay Museum Collection back in 20098 with a group of Tiwi delegates who travelled to Sydney and Canberra as part of the repatriation process of the ethnographic Tiwi recordings held at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). That also included viewing the Tiwi collections at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra and the National Film and Sound Archive and the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) in Sydney.9 Jacinta contributed to this chapter as a representative of senior Tiwi culture and knowledge custodians. Through the process of assessing and consulting on the collections, she (and the others in the group) articulated the sense that the material and the information embedded in them were “owned” not by individuals, but by kinship and Country groups and that those credited as the singers, dancers, painters or carvers were, at the time, the current custodians of those songs, dances and designs. This raises questions for archivists and historians around reclamation, ownership and agency of Indigenous stakeholders in the presentation of their cultural heritage. In their recent reflection on digital archival returns, Barwick, Green, Vaarzon-Morel and Zissermann state: “Even where intellectual property rights can be said to be held by Indigenous contributors to research, such rights can only be held individually (not collectively). This does not properly reflect Indigenous law and practices regarding the custodianship and intergenerational transmission of knowledge”.10 Jacinta’s words quoted at the start of this chapter give a sense of this cross-generational and communal custodianship of collective knowledge that informed all of our consultations.

This chapter builds on other recent scholarship that has sought to think about the ways “collections” can disperse records of culture across institutions and pose challenges to cultural custodians seeking to reassemble fragmented records. Often the result of collaborative work, this scholarship has begun to highlight the ways the priorities of archives and those of communities may differ. Barwick et al. also identify a tension between the archive’s emphasis on “products” and living communities’ emphasis on “process”; in other words, a contrast between archives as “the documentary by-product of human activity” and “knowledge management systems that depend on face-to-face communication as the primary means of cultural transmission”.11

In the same volume, Gibson, Angeles and Liddle explore the challenges faced by contemporary language custodians of archival records whose historical orthographies remain in a static past, written down a century ago. As orthographies have varied across the archives and in the labelling of collections, they are, while highly valued records of language and stories, simultaneously disconnected from those of the younger generation trying to learn.12 Both Barwick et al. and Gibson et al. show the considerable challenges posed by assemblages of cultural materials in archives that are disconnected in complex ways from the contexts for culture among contemporary custodians. In another recent volume on repatriation of music, Daniel B. Reed describes repatriation as the “moment when archival memory and human memory” meet. Reed suggests that memory is preserved in different forms in oral traditions and in archives, but that connecting the two through repatriation brings the archive into its context as “part of the processes of human life”.13

Visual art and material culture in museums and galleries are often regarded as separate from these records of song and language preserved in archives. The fraught histories of museum collections of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material culture have been the topic of considerable scholarship. Scholars including Nicholas Thomas, Ian McLean, Sandy O’Sullivan and Sally K. May have interrogated the complex histories of collection of this tangible culture and the delineation of some objects as museum pieces and others as modern art.14 The separation of historical materials across archives, museums, libraries, cultural institutions and private collections is addressed by Thorpe, Faulkhead and Booker in the context of larger agendas of repatriation of human remains. They show that different kinds of fragmented collections need to be brought into dialogue with one another to properly contextualise practices of collecting and to realise the potential for repatriation back to communities.15

In this chapter, we also highlight the dispersal of Tiwi records of cultural practice into “collections” held in different kinds of institutions. Like Thorpe et al. we aim to bring material and ephemeral cultural collections into dialogue and to highlight ongoing relationships between songs, cultural practice and material culture used in performance. We interrogate the notion of museum and archive “collections”. Whereas the word implies a process of assembly, cultural objects have historically been separated and dispersed, not only from one another, but also from their cultural context, stripped of meanings and connections, and rendered inanimate. These assemblages are often categorised by a researcher or curator, or publishers’ intentions, rather than an understanding and arrangement of information through the practice of culture. In photographic archives, for example, documentation of performances in the form of printed copies of photographic images are many times shuffled like a deck of cards, their numbering and ordering entirely arbitrary and their inherent archival value lost. We show how recent work with custodians of Tiwi culture reassembles parts of the cultural whole that have been fragmented by non-Indigenous collection practices that separate material culture and performance of dance and song into distinct categories.

The material and performed culture viewed by the Strong Women’s Group (and the focus of this chapter) included:

- 1927–29 and 1942 collections of Tiwi artefacts at the Macleay Museum

- 1948 footage of a public corroboree in Darwin Botanic Gardens16

- 1963 Aboriginal Theatre performance, film and associated exhibition17

- 1964 film In Song and Dance18

Prompted by the participants, this also led to discussions about a further event:

- 1970 Ballet of the South Pacific

Returning to the University of Sydney in 2019 as invited consultants on research into historical public performances by Aboriginal people (represented by the film footage listed above) and the preparation of the Tiwi exhibit included in the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s new permanent exhibition – Ambassadors – has confirmed for the Tiwi group their valid and valuable role in engaging with research, archives and museums. For those who had been to Sydney and Canberra in 2009 it was also an opportunity to take a leading role in the ongoing story of the engagement and to be the latest holders of the responsibility for the items themselves.19

The interconnectedness of material pieces and recorded song and dance was apparent in all interactions with the collections. Songs mark totems, clans and Country groups just as painted designs do. Similarly, recorded songs – the recordings themselves – are tangible, and the reactions to the audio and visual items in the archive create a tangible experience in the same way as holding a century-old stone axe or ceremonial spear. Song becomes artefact in this context, as the voice, the words, the manifestation of the ancestor and the song subject all create a visceral experience to the Tiwi custodian and another – different, but equally meaningful – to the non-Tiwi observer, who is in turn invested with the importance of the archive, its content, and its potential value to the custodians.

Those people in those days, they had to paint because the ceremony was coming. They kept them going. Each Dreaming has different paint. Different where we come from like totem. Great and grandfathers, fathers. It’s sort of like we all Tiwi people from the two islands [but] different totem. It was passing down from the old people. Passing down the knowledge they had. Passing down to us, and us, we are passing down our knowledge to next generation, ongoing.

Jacinta Tipungwuti

The Macleay Museum Collection of material culture

The University of Sydney has, for nearly a century, been custodian of a selection of objects from the Tiwi Islands. The assemblage contains four Tunkalinta and three Arawanikiri (types of spears), four Kurrujuwa (metal axes) and two Mukwani (stone axes), as well as a selection of around 60 photographs acquired by three different collectors between the 1920s and 1950s. The collections were transferred from the University of Sydney Department of Anthropology to the permanent collections of the Macleay Museum (now incorporated into the Chau Chak Wing Museum) between 1960 and 1964 and have been rarely exhibited.

The distance between the museum’s location in south-eastern Australia and the Tiwi Islands off the coast of the Northern Territory means that there have been few opportunities for Tiwi people, who have significant personal and cultural connections to the items, to view the collection. In 2019, the Strong Women’s Group’s tour to Sydney for performances not far from the museum storerooms provided an opportunity to follow up on the previous visit more than a decade earlier and to start new conversations about what these objects mean for Tiwi today.

These conversations among the visiting Tiwi community would result in new interpretive layers being added to the objects’ exhibition in the university’s new Chau Chak Wing Museum (opened in November 2020), part of the transition from the older “natural history” style museum space into a new building designed to incorporate the multiple forms of collections across the University Art Collection and Nicholson Collection. The Tiwi group’s visit to the collections enabled an entirely new way of thinking about positioning Tiwi exhibition objects in relation to each other that was not previously in the curatorial brief.

Several of the items that formed the basis of consultation with the Strong Women’s Group were acquired by American anthropologist Charles William Merton Hart in the 1920s, as part of research funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC), administered via the University of Sydney Department of Anthropology. Hart conducted his research among Tiwi people between 1928 and 1929.20

Among the objects are two metal axes21 with resin and plaited cane, decorated with alternating bands of yellow and white ochre, and two stone axes with similar production techniques but different patterning of the ochre. One of the stone axes is labelled as a “Koong Kwang”. This bears no resemblance to Tiwi orthology but is in the group’s opinion a rough transcription of an archaic word for stone axe or hammer – Mukwanga. Neither are names that the community use to discuss these objects in 2020. A modern (metal-headed) axe is Kurrujuwa or, less often used, the old word Walimani, a loan-word from Iwaidja. It was decided that Mukwani (a small stone axe) should be used in the exhibition to label the stone axes and Walimani to describe the metal axes.22

The original labelling of the Macleay Collection exemplifies past museum practices that were grounded in the science of anthropological research, but today these collecting purposes are entirely at odds with the ways that the community would represent themselves to the outside world. For example, very little was known about the provenance or function of the Tiwi spears, which form a centrepiece of the new museum display. While there is no way to be certain what degree of agency the Tiwi makers and owners of the spears had at the time they were collected, the 2019 Tiwi group were of the opinion that the spears provided to collectors in 1928 would have been free from ritual connections, having been retired from use.23 There are numerous Tiwi words (many no longer in use)24 describing many variations of spears, creating potential layers of meaning and impact for Tiwi viewers that the curators were unaware of when they relied only on the written catalogue documentation. The visiting Tiwi group was able to add rich information about their ritual use and gender associations, the meanings of their carved and painted designs, and the kinship groups to which their makers likely belonged. The degree of painted decoration and their carved design indicated to Tiwi cultural authorities that the spears were used in ceremony and in ritual/mock fighting. Conversely, the axes were not considered ceremonial and there was speculation as to whether they perhaps had been painted at the request of collectors. All the items were confirmed to be free of any restrictions that would impede their public display.

The updating of historical documentation and language words for items such as these presents another opportunity to engage directly with current cultural custodians. The often-scant collection metadata represents another potential pitfall of museums presenting historical or archival information, reinforcing a hierarchy and imbalance between Tiwi community knowledge of these types of objects and the museums as authorities or primary sources of information. The simple process of renaming the spears and axes in the current Tiwi language and seeking accurate information and cultural context is a subtle shift in the process of museums recognising the agency and autonomy of community members in the consultation process.

The museum’s Hart Collection was of particular interest to Tiwi singers when considered in relation to the audio recordings Hart made on the islands in 1928.25 Several correlations were made between the song items and the tangible objects and photographs in the Hart Collection in terms of ceremonial context, likely artists and singers, and reference to kinship, Country identities and ancestral totems. Hart’s photographs of ceremony being performed show particular dance gestures that match song items among the Hart recordings. Completing the circle, the photos show men carrying ceremonial spears which, while not the actual objects in the museum, confirm the performative context of the kinds of spears held in the collection.

Not all of the objects in the new Chau Chak Wing Museum Tiwi assemblage were acquired through anthropological research. One Tunkalinta/Numwariyaka (straight barbless spear) and three Arawanikiri (barbed spears) were acquired via private collector Frank Delbridge in 1927 (and possibly purchased in Darwin) and by Cecil Blumenthal, who was based on Bathurst Island as a radar technician in 1942.

Continuities in song and material culture

An interesting link exists between Blumenthal’s wartime collection activities, and local history and its documentation through performance. The Japanese air strike of Darwin in February 1942, which saw aeroplanes fly over and strafe the south-east of Bathurst Island, was documented in song within a Kulama26 ceremony, most likely in around March that year. The song has entered the Tiwi repertoire with varying versions retelling (and enacting through dance) the story of the planes, the radio controllers’ attempts to warn the mainland, the subsequent bombings and the killing of civilians.

The 1949 film Darwin – Doorway to Australia includes footage of a large public corroboree in Darwin’s Botanic Gardens in April 1948 – the first such public event since the end of World War II. The film shows Tiwi Yoi (Dreaming) dances that are performed today, and the Strong Women’s Group were particularly interested to hear mention of the Japanese air attack on Darwin during World War II in the film and suggested it is likely that this event might have been the first public performance on the mainland of a Tiwi Kulama “Bombing of Darwin” or “Air Raid” song.27 The song has been performed many times since WWII, in the traditional Kulama musical and linguistic form as well as in the women’s “modern” form with guitar. For older Tiwi people in particular this was an empowering event that signified the Tiwi’s sense of being part of Australia and involved in the war, but mixed feelings remain about the warnings to Darwin going unheeded/ignored. “Bombing of Darwin” was performed at the Darwin Festival Closing Ceremony in 2009,28 in an event quite similar to the 1948 corroboree. Presented on a prepared sand dance ground, it included groups from Beswick, the Tiwi Islands, Maningrida and Darwin (groups also represented in the 1948 footage) performing in a corroboree set up for a large public audience. During both the 1948 and 2009 events, performers grasped spears of the kind held in the museum’s collection.

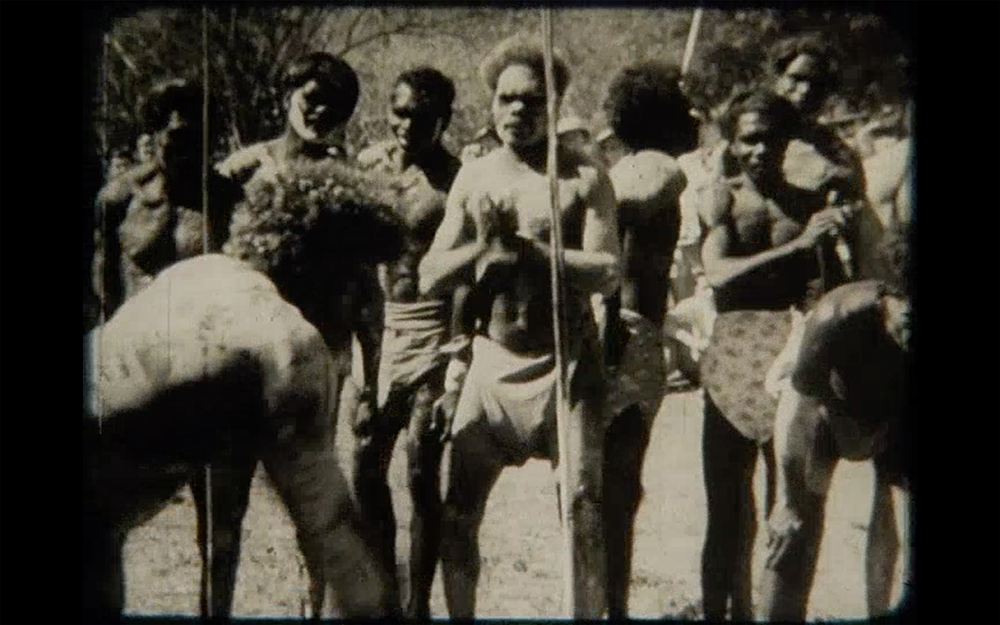

Figure 4.1 1948 Botanic Gardens corroboree – still from film Darwin – Doorway to Australia (1949), C809, 1139364, Northern Territory Archives, Darwin.

A turtuni or Pukumani pole is also visible in the 1948 footage.29 Pukumani poles have been of particular interest to anthropologists, art historians and collectors due to their size and decoration and because they are unique to Tiwi mortuary ceremonies. The complexities of displaying mortuary-related material have made ethical collection and display a complex subject for Tiwi engagement with museums and archives for many years. Some of the earliest collections of Pukumani poles on record are those collected by government “protector” Herbert Basedow in 1911, and poles collected in 1924, held by the Vatican Ethnological Museum. Basedow’s notes say the poles collected in 1911 were from a Pukumani Yiloti (Final) ceremony held for a baby some years before Basedow was there and that the body was exhumed but was deemed to be in too poor condition to collect (Basedow 1913). Basedow had the poles repainted by Tiwi men and then removed from the site and shipped to Adelaide, where they were eventually housed at the South Australian Museum in 1934. These circumstances have been particularly upsetting for Tiwi Elders.

The Vatican Ethnological Museum’s description of its collection of Pukumani poles states that “traditionally the posts should be left to deteriorate; however, these were produced for display and are among the most ancient museum specimens in the world”.30 Whether the poles collected in 1924 were in fact “produced for display” (and not for an individual’s mortuary ceremony) is questionable. There is some evidence that in the early contact era Tiwi people offered ceremonial paraphernalia (spears, baskets, and woven arm and head bands) in exchanges of goods with visitors to the islands (Venbrux 2008), but it is widely agreed among Tiwi people today that, as the process of harvesting, carving and painting the poles forms part of the ritual stages of Pukumani – the deceased’s final, and most important, mortuary ceremony – they should never be removed. Moreover, the poles erected in the early part of last century were in the ancestral place of the deceased’s Country; the poles symbolise the person and stand in their Country always, to slowly break down into the earth.

The first Pukumani poles to be commissioned as works of art (rather than objects for display in an ethnographic museum) were the 17 poles displayed in the AGNSW, acquired in 1958 by Dr Stuart Scougall and then gallery director Tony Tuckson.31 It is significant that the Melville Island artists, knowing the poles were destined for exhibition and a non-ceremonial context, used ironwood rather than bloodwood, which was traditionally used for ceremony.32

These stories of collected Pukumani poles raised questions around the public display of objects and performances intended for ritual as the group watched two other excerpts of footage: one of the 1964 North Australian Eisteddfod, and another of a 1963 touring show called the Aboriginal Theatre, featuring 17 Tiwi performers among its cast.33 A significant feature of the Aboriginal Theatre’s staging for its Sydney and Melbourne shows was the Pukumani poles around which the Tiwi performances revolved.

Looking at footage and listening to recordings of the Aboriginal Theatre as performers and ceremony leaders themselves, the group agreed that the dances and song texts were not altered, simplified or re-created in any way differently for the purpose of the non-Tiwi audience context. They recognised phrases and words that are still used in Pukumani and Kulama ceremonies on the islands and agreed that those songs would have been in the men’s repertoire for (Tiwi) family and community events. The “Pukumani” segment of the concert comprised a selection of songs that would be performed as part of the (much larger) series of mortuary rituals and observances collectively known as Pukumani. The segment gave a demonstration of some elements of a mortuary ceremony, including the “Mosquito” and “Honey Bag” opening of ceremony, the calling of ancestral and Country names, and ritual wailing but, importantly, it did not refer to an actual deceased person. In a close parallel with the acquisition of the Pukumani poles in the AGNSW, the Tiwi listeners in 2019 told us that it was therefore fine to be performed in a public concert and that the words, the respect and the cultural meaning were intact. It was presented consciously as a piece of cultural heritage and art, as are the poles.

Among Tiwi consultants there have been widely differing opinions on the ethics surrounding the collection of some recorded material, especially the recordings of mourning songs. Some Tiwi people listen with interest to the performance elements that have been preserved for posterity, or with sentimental pleasure and pride – as did the group as they listened to the publicly staged performance of the Aboriginal Theatre, hearing the wailing and sung/intoned sighs of Amparru (grieving) songs as elements of ritual. Others heard, among the rest of the ethnographic recorded archive, personal grief and pain and thought it inappropriate for anyone other than close family to listen. There are ongoing discussions about the difference between singing for family and singing for visitors/researchers (in the context of ceremony), with many people concerned that singers might have been discomforted by the intrusion of the recorder (or not have been aware of its presence), or of the long-term ramifications of being recorded.

The complex circumstances of collected recordings are exemplified by a Pukumani ceremony recorded in 1966 with a very different context to the Aboriginal Theatre. Warabutiwayi Mungatopi (Allie Miller) played an important role as cultural ambassador and performer in the 1950s–1970s. In 1953 he was part of the group of Aboriginal dancers performing for Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Brisbane. He was one of ethnographer Charles Mountford’s principal singers in 1954 and therefore a good deal of his vocal, linguistic and family history is recorded.34 Mungatopi also led the Tiwi group sent to the North Australian Eisteddfod in Darwin in 1964 and the film35 made about the event features him, as a white-haired Elder, dancing crocodile, his Yoi (Dreaming).

Allie Mungatopi/Miller and his wife Polly were also primary consultants for Sandra Holmes, who collected extensive field recordings of ceremonies as well as paintings and carvings in the 1960s.36 It is perhaps then not a coincidence that, when the Pukumani ceremony for Polly and Allie Miller’s deceased young son was held, in May 1966, at the then Bagot Aboriginal Reserve in Darwin,37 it was presented to a non-Tiwi audience as an exhibition of sorts. The segment below, written by Holmes, indicates that the ceremony was seen by the government Native Welfare Branch as a good opportunity to give (white) people a new cultural experience. Unlike the consciously staged performances mentioned in this paper, it seems that on this occasion the Tiwi people were not necessarily given much of a choice in the matter. Allie is quoted as having been upset at the lack of understanding and respect for his son’s ceremony: “Too many white people come … we never ask them to come, only Welfare man can say.”38 In the following quotation Holmes makes the distinction between ceremony and performance:

The Welfare Branch had declared an Open Day for tourists and locals … Polly sang softly to the ghost of her dead son and signalled for me to record it … Crowds of white visitors jostled each other for photo opportunities, staring expectantly up the hill to where the Tiwi mourners were assembled in full ceremonial regalia.39

By Holmes’ accounts the ceremony was just as it would have been (in terms of structure and ritual) without any non-Tiwi onlookers. Clearly, though, they were being watched as spectacle. Holmes goes on to report:

At this point a senior welfare officer stood up and made a speech to thank the public for attending the ceremony and the Tiwi people for the performance. By prior arrangement the sculptures and grave posts would be sold to various dealers and other outlets.40

The distinction between “ceremony” and “performance” in Holmes’ reporting of the welfare officer’s words implies there was a difference in perception between the audience’s and the mourners’ experiences of the event. The white audience was watching a performance (with the added exoticism of knowing it was a ceremony) while the mourners were attempting to have ceremony for family, knowing they were being watched and photographed.

By contrast, in the 1964 eisteddfod film we see Allie speaking to the group (in Tiwi) saying, “We need to get ready and practise for this thing in Darwin. Ted Evans came across from Darwin to Snake Bay to tell us we are going in”.41 The Strong Women’s Group viewed this as an indication that the performers’ involvement was real and informed. Mary Elizabeth Moreen (Polly and Allie Miller’s daughter and related by marriage to Rusty Moreen, who features in the film), now in her late sixties, was involved in her parents’ consultations with Holmes. It is perhaps no coincidence that Mary is now a leader among the Strong Women’s Group and has been proactive in reclaiming recorded collections and engaging with museums and archives.42

The songs and singers as animators of the archive

Way back they used the name of what they did in the past. We can name them because it’s a bit similar to those in the past. The same sound. It’s the way they used to say and hear somebody say and they put it in a song. It’s like a good thing, saying and singing all these songs in the traditional way of singing. We all have different versions, different songs – it’s all part of the good songs and the words’ meaning.

Jacinta Tipungwuti

The body painting and feathered beards and headdresses worn by performers in the 1948 corroboree footage and the intricately painted spears in the Macleay Collection inspired much discussion about the perceived lost richness of ritual paraphernalia and preparation today. Tiwi viewers were also interested to see the paint on Eddie, a young boy featured in the Aboriginal Theatre film. The design is specific to a particular stage of initiation and is no longer used. Justin Puruntatameri, a leading song and culture man who passed away in 2012, aged 87, is shown as a much younger man, applying the design. Current Elders noted that this film shows that Mr Puruntatameri was continuing the practice of painting initiands in 1963 (more recently than people had thought) and it sparked discussion around the possibility of reintroducing the designs and some of the ceremonial dance and song events that involve young people.

The choice of participants in each of these performance events (based perhaps on cultural or socio-political authority) and the song choices they then made have had significant effect on which song types, which dances and which elements of the otherwise fragile song language have endured. In much the same way, the collection of certain artists’ items have preserved particular designs and stories, with corresponding empowerment of individuals and of groups both at the time of collection or recording and recently, as they have become items of cultural heritage that add to the story of the museum collections.

While discussing the 1963 Aboriginal Theatre, Regina Kantilla talked about coming to Sydney to perform in a similar show – the 1970 Ballet of the South Pacific. Opening at Her Majesty’s Theatre on 6 April 1970, the Ballet of the South Pacific brought together 20 Aboriginal performers from Northern Australia with dancers from the Cook Islands, directed by Beth Dean and Victor Carell.43 The format of the Ballet of the South Pacific very closely mimicked the format of the 1963 Aboriginal Theatre, even to the extent of including some of the same musicians or dancers and many members of the same communities, though the production team was different. Members of the Bathurst Island Tipungwuti, Puruntatameri and Portaminni families were involved in both the 1963 Aboriginal Theatre and 1970 Ballet of the South Pacific.44 The subject matter of songs featured in the Aboriginal Theatre and also in the Darwin eisteddfod are indicative of the Country and kinship affiliations of the performers involved in each.

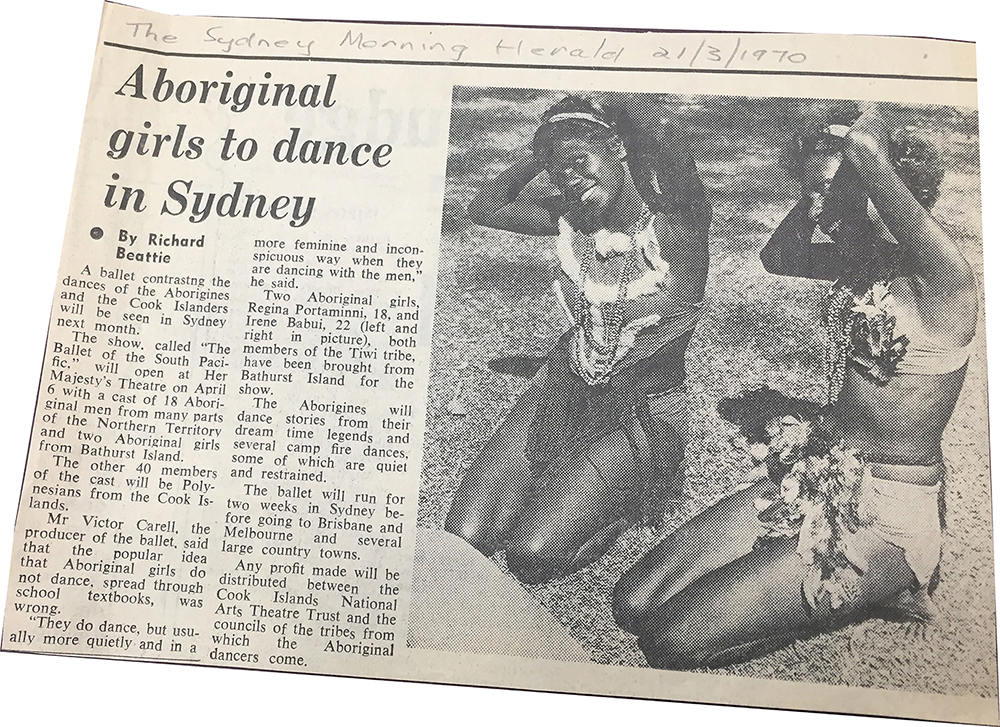

Figure 4.2 Regina Portaminni and Irene Babui, pictured in Richard Beattie, “Aboriginal Girls to Dance in Sydney”, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1970, clipping in Beth Dean and Victor Carell papers, MS 7804, Box 10. (State Library of NSW.)

In the 1970 shows, Tiwi women Regina Portaminni (now Kantilla) and Irene Babui presented a set of women’s dances.45 Regina was amused, in 2019, to see the photo of her younger self in this photograph. Their costumes were not Tiwi, but perhaps a choice made by the producers to portray an islander look since the Tiwi women’s lack of “cultural dress”46 necessitated creation of a “native” costume – Regina wasn’t sure and didn’t recall any discussion about costume choice. There was some offence taken by some of the wording in the newspaper article and the description of their performance as “primitive dances”. Regina was not so concerned about this though and recalled the fun she and Irene had had on the tour and said “that’s just how they talk about us back then … I don’t know, it was cute those outfits we had … but I was very nervous too, but that’s maybe why I learned how to do it. Now I’m so good on stage!”47

This costuming anachronism aside, there were many connections found between the archive collections and ongoing continuity of practice. In the context of the performers sharing their culture, the potential for the performances to be forward-looking and future-facing seems also to have been a key motivator. Most of the songs performed in the Aboriginal Theatre are performed today with the song texts varying slightly within the parameters of individuals’ extemporisation and with accompanying dance and gestures unchanged. The opinion of the Strong Women’s Group is that the song subject choices were also just like “the songs we show to people these days” with a combination of ancestral stories, the Yoi (Dreaming) of the participants and a recognition of the event itself through song. A song translating loosely as “Cars, Town Life, Aeroplane” in the 1963 Aboriginal Theatre program is considered by the group to be the performers’ acknowledgement of their trip to Melbourne in the tradition of Tiwi songs that document current events for the social record.

Maybe they sat down and talked about the program. Like we do with you sometimes. Choose some palingarri [old] stories, some Yoi for each person [totemic dances], some story songs. They sang that Nyingawi song to tell people about how we Tiwi learned to sing Kulama … and maybe “Bombing of Darwin” is interesting for white people to know those planes went over here, you know?

Jacinta Tipungwuti

At their own performance in Sydney the week of viewing the footage, the group spontaneously inserted into the program a healing song to acknowledge the funeral of a Tiwi woman48 being held that day. Knowing they would have been leading the healing stage of the funeral if they’d been attending, they sang because

we were feeling bad not being at home and singing for her like we should be, so we sang it for her here. Share that sadness with friends in Sydney. Respect too. Showing respect for our sister.

Jacinta Tipungwuti

A more generic version of a healing song would likely have been on the program anyway, just as in the “Pukumani” performance in 1963, and although they had a non-Tiwi audience, the cultural integrity and function of the song for the Tiwi participants overrode the fact that there was an audience.

Across the consultations, the principal connection between the group and the archives was the performance of culture. A core feature of Tiwi oral and embodied knowledge keeping is the creation of occasion-specific song text that acknowledges both the ancestral predecessors and the current knowledge holders. This makes fluid and transparent the boundaries between cultural artefacts (with their connections through designs to Country and kinship groups and ancestral stories) and sung artefacts (songs marking those same Country and kinship groups and ancestral stories). Just as Tungutalum sang “I am talking into the gramophone” for Hart’s recorder in 1928,49 and the Tiwi men in 1963 created a song to add their journey to Melbourne to the oral record, the Strong Women’s Group in 2019 sang, among a program of ancestral and Country songs, a song to explain that they were in Sydney missing the AFL Tiwi Islands Grand Final. All are examples of the performance motivations for people to whom song is fundamentally a vehicle for knowledge transmission.

The 1928 recording of Tungutalum was played in the opening sequence of the 2019 performance in Sydney, completing a circle of animating culture in a tangible way. Having seen the objects collected by Hart at the time the recording of Tungutalum was collected, we then heard Tungutalum singing his own proactive engagement with the process of creating an archive that would then be re-engaged with nearly a century later.

Recordings among the archives of now-obsolete song forms (having not been performed in living memory), such as the “Mosquito” and “Honey Bag” calls and some dance gestures shown in the 1948 footage, have been cited by senior culture people as an important opportunity to reclaim cultural heritage – just one example of audiovisual archives having as tangible a presence as artefact. Like “corroborees” that have long brought people together in cultural exchange, the recordings of public performances, concerts and eisteddfods play an important role in supporting ongoing performance practices. The preparation of high-quality performances helped give validity to ongoing practice of traditions that might otherwise have been under pressure to fall away in favour of church hymns in language, or communication and adoption of teaching in English.50

When talking about the performances in the Botanic Gardens and the memories the Tiwi women had of being part of eisteddfods in Darwin and precursor competitions held on the islands, there is a sense of nostalgia for the experiences they had, and also a feeling that those events served a role in maintaining song culture, creating a goal and sense of pride in performing for an outside audience. That era has left a lasting impression on the culture now because it is the young women and men who had those experiences who have become the Elders holding onto culture. Jacinta Tipungwuti recalls learning these songs for the eisteddfod and remembers that it was only after they completed their schooling that they were able to develop knowledge in Tiwi song practice. Now children are able to learn Tiwi songs from their Elders as part of everyday life.

Cultural leaders and cultural ambassadors

They had that strong culture! And they left that for us … generation to generation … You know when old people pass away there’ll be nobody there singing and dancing, but they have to know, have that knowledge … today and listen to the Elders [in the footage] what they are singing about and the language that belongs to us.

Jacinta Tipungwuti

As language and music experts listening to the full audio of the Aboriginal Theatre performance, the Tiwi group was able to add song text, translations and some small corrections to song subjects mentioned in the film’s narration and program – details that would not have affected the audience perception but that reiterate the value of information that those with cultural authority and knowledge can add to an archive. As experts in the performance of ceremony, the group also added value to the museum collection, organising Hart’s photographs in sequence by recognising dances and gestures specific to certain ritual stages. It was clear that they saw the objects (in this case the photographs and the dance, gesture and spears they depict) not as inanimate, but as representations of performed culture. Each photograph was described in terms of the dance or the gesturing it had captured and the spears (both in the photographs and in the collection) were described by the way they were held and which part of ceremony they were used for. Here performance constituted the value of the archival objects, and the objects enabled a deeper understanding of the performative context and corrected some assumptions of the use of artefact. This series of photos was another example of a collection categorised by a researcher or curator rather than through the practice of culture. Reassembling them in their performed order has reanimated and enriched their meaning.

At the Macleay Collection viewing, the contrasting, yet equally meaningful, reaction to artefacts brought these differing and interconnecting agencies together as the group viewed the spears, the designs on which were known to Elders and family names attributed to potential individual makers. These designs were familiar and brought up emotions not only of interest from a heritage perspective but also of strong family pride and sentiment. They identified the idiosyncratic painted design elements of two distinct artists and designs connected to particular kinship groups. With this and the women’s descriptions of how the spears are carried in ritual and dance in mind, the group and the curator developed the layout, order and positioning of the spears for the new display. This collaborative and participatory process of co-authoring display design and label information (where appropriate) reflects the expectations of contemporary community agency by retaining the autonomy of community opinion and authority.

A catalogue of designs and a length of fabric in the collection that is labelled as an example of one of the first designs from Bima Wear screen printing on Bathurst Island created a particularly strong point of collision between archive and living culture. Jacinta had a (newly made) skirt in her luggage in fabric of that same design. Some of the women present had worked at Bima Wear in the past and all have worn these fabrics daily since the 1970s. Not unlike the group’s reaction to some of the songs in the audiovisual archive that were “just like we do now” and the grouping of spears by artist by identifying painted design elements used today, talk afterwards suggested the women were a little concerned that they might offend the people at the archives by saying that what they have been looking after so carefully is actually quite normal. On the other hand, as Augusta Punguatji said, “It is really good to let them know that we are still doing what those people did back then because our culture is so strong.” These direct associations between current culture holders and their predecessors confirm their role not only as custodians of an ongoing culture but also as holders of knowledge that is of great value to museum curators and researchers.

Across the film material and the museum collection we also found that some items are no longer made or performed in exactly the same way, traditions having been modified through time and the creative idiosyncrasies of individuals, and so they have become important items of cultural heritage, preserved in the archive for both Tiwi and non-Tiwi viewers.

The following, from the promotional material associated with the Sydney performance in 2019, describes some of the motivation the Strong Women’s Group share through their intangible cultural heritage:

Ngarukuruwala means we sing songs. The Tiwi Strong Women’s Group don’t really “rehearse” or “perform” – they come together to sing. They don’t really see themselves as a choir. They are a group of women who share a connection through the songs they know, create and sing together nearly every day.51

As the group have described their own approach towards the rehearsal process, which is not entirely different from the research process for museum exhibitions, it is not the end result – the performance or the exhibition itself – that is the main goal. It is in the process of coming together, the continuation of practice and the sharing of knowledge that the real cultural value of the items (tangible and intangible) is found.

Figure 4.3 Gemma Munkara and Katrina Mungatopi viewing the Tiwi display; Chau Chak Wing Museum, May 2021.

Coda

They carry [the spears] when they start to have the ceremony, coming in. The opening of the ceremony they carry this spear – the Elder of the ceremony.

Jacinta Tipungwuti

In May 2021 eight Tiwi singers52 performed in the new Chau Chak Wing Museum and viewed the Tiwi display for the first time. As they approached the case, senior songwoman Calista Kantilla called out the Tiwi ancestral Countries and kinship groups, acknowledging the group’s presence as visitors to others’ ancestral lands and as representatives of their own ancestors as current Elders. Just as they would in ceremony (and just as we had recently seen in the filmed and photographed archives) they carried spears – one a beautiful example of the broad-headed, double-barbed Arawanikiri ceremonial spear, made by Bede Tungutalum, a current senior culture man and artist and a direct male descendant of Tungutalum who was photographed and recorded by Hart in 1928.53 Having spent time discussing the spears in the museum collection, gaining insights into the ochre designs and the ceremonial functions of the different types of spears in the display, it was a powerful moment then for the curators to witness the animating of what was previously merely collated data – the spears being used in contemporary, ongoing performative cultural practice. In real-time demonstration of their agency and engagement with the archives, the group read the object labels, and the spelling and the cultural information, and as the senior culture person present, Calista gave her official nod of approval. In a symbolic gesture of acknowledgement and ratification of the display, the group then danced towards the display case, animating the cultural heritage in front of them and holding spears very closely resembling those made by their ancestors a century ago.

It’s hard to explain. The young people need to understand because in the future time they will make this place better for themselves and their families. It will strengthen them and give them more, like healing, and they will understand “who am I?” First thing they’ll say to themselves. “Who am I, where I belong to?” which is the main identity. It’s important for them to know their culture and the way they are living today.

Jacinta Tipungwuti

References

“A Royal Tour Disappointment”. West Australian, 20 April 1948, 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article46904700.

“Aborigines Thrill Big Crowd with Dance and Ritual”. Northern Standard, 23 April 1948, 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49984700.

“Ballet of the South Pacific”. Australian Women’s Weekly, 1 April 1970, 25. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47814074.

Barwick, Linda, Jennifer Green, Petronella Vaarzon-Morel and Katya Zissermann. “Conundrums and Consequences: Doing Digital Archival Returns in Australia”. In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel. Honolulu and Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2019: 1–27.

Basedow, Herbert. “Notes on the Natives of Bathurst Island, North Australia”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 43 (1913): 291–323.

Campbell, Genevieve. “Ngarriwanajirri, the Tiwi Strong Kids Song: Using Repatriated Recordings in a Contemporary Music Project”. Yearbook for Traditional Music 44 (2012): 1–23.

Campbell, Genevieve. “Sustaining Tiwi Song Practice Through Kulama”. Musicology Australia 35, no. 2 (2013): 237–52.

Christie, Michael. “Digital Tools and the Management of Australian Desert Aboriginal Knowledge”. In Global Indigenous Media: Cultures, Poetics, and Politics, eds Pamela Wilson and Michelle Stewart. Atlanta: Duke University Press, 2008: 270–86.

“Death Dance Star Mobbed in Darwin”. Courier-Mail, 19 April 1948, 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49666240.

Dunbar-Hall, Peter and Chris Gibson. Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music in Australia. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2004.

Gibson, Jason, Shaun Penangke Angeles and Joel Perrurle Liddle. “Deciphering Arrernte Archives: The Intermingling of Textual and Living Knowledge”. In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel. Honolulu and Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2019: 29–45.

Hart, Charles William Merton. “Fieldwork Among the Tiwi, 1928–1929”. In Being an Anthropologist, ed. G. Spindler. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970.

Holmes, Sandra Le Brun. The Goddess and the Moon Man: The Sacred Art of the Tiwi Aborigines. Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman House, 1995.

Janke, Terri. “Indigenous Knowledge and Intellectual Property: Negotiating the Spaces”. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 37, no. S1 (2008): 14–24.

Lee, Jennifer. Tiwi Today: A Study of Language Change in a Contact Situation. Canberra: Australian National University, 1987.

Lee, Jennifer. “Tiwi–English Interactive Dictionary”, from Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL) Interactive Dictionary, ed. Maarten Lecompte (for interactive version), 2011 http://203.122.249.186/TiwiLexicon/lexicon/main.htm.

May, Sally. Collecting Cultures: Myth, Politics, and Collaboration in the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press, 2009.

McLean, Ian. Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art. London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2016.

Mountford, Charles. The Tiwi: Their Art, Myth and Ceremony. London: Phoenix House, 1958.

Simpson, Colin. Adam in Ochre: Inside Aboriginal Australia. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1951.

O’Sullivan, Sandy. “Reversing the Gaze: Considering Indigenous Perspectives on Museums, Cultural Representation and the Equivocal Digital Remnant”. In Information Technology and Indigenous Communities, eds Lyndon Ormond-Parker, Aaron Corn, Cressida Fforde, Kazuko Obata and Sandy O’Sullivan. Canberra: AIATSIS Research Publications, 2013: 139–49.

Reed, Daniel. “Reflections on Reconnections: When Human and Archival Modes of Memory Meet”. In The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, eds Frank Gunderson, Rob Lancefield and Bret Woods. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018: 23–36.

Thomas, Nicholas. Possessions: Indigenous Art, Colonial Culture. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

Thorpe, Kirsten, Shannon Faulkhead and Lauren Booker. “Transforming the Archive: Returning and Connecting Indigenous Repatriation Records”. In The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Repatriation: Return, Reconcile, Renew, eds Cressida Fforde, C. Timothy McKeown and Honor Keeler. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2020: 822–34.

Venbrux, Eric. “Quite Another World of Aboriginal Life: Indigenous People in an Evolving Museumscape”. In The Future of Indigenous Museums: Perspectives from the Southwest Pacific, ed. Nick Stanley. New York: Berghahn Books, 2008: 117–34.

1 Mrs Tipungwuti, co-author on this paper, is directly quoted throughout. Her thoughts and opinions as representative of the group involved in viewing the material are incorporated in the body of the text. All quotations are from conversations led by Jacinta with the Strong Women’s Group, in Sydney in March and May 2019 in Wurrumiyanga, Bathurst Island, reflecting on the visit to Sydney.

2 Here we refer to the Kulama rituals, which formed the basis of education and initiation for young Tiwi people, and Pukumani-associated ceremonies and rituals related to death and mourning.

3 This includes making artefacts for local ceremonial and utilitarian use, as well as creating art for external sale and/or display.

4 A performance by the collaborative group Ngarukuruwala (we sing songs) was presented by the Sydney Environment Institute at the Sound Lounge, Seymour Centre, 15 March 2019.

5 The films (and photographs) of the museum collection were shown to other Tiwi individuals with particular family connection to and cultural knowledge of the material.

6 Mrs Punguatji passed away in August 2022. Her name is included here with the knowledge and permission of her family.

7 For the purposes of this chapter, Mr Orsto is happy for us to refer to the group as the Strong Women’s Group on the reader’s understanding that he was also present.

8 Regina Kantilla and Francis Orsto were also among the group in both 2009 and in 2019. Regina, Augusta Punguatji and Frances Therese Portaminni returned again in 2021.

9 It also included performances at the Conservatorium of Music and the National Film and Sound Archive, both of which were informed by the discoveries the group had made in the collections.

10 Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green, Petronella Vaarzon-Morel and Katya Zissermann, “Conundrums and Consequences: Doing Digital Archival Returns in Australia”, in Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel (Honolulu & Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2019), 10. See also: Michael Christie, “Digital Tools and the Management of Australian Desert Aboriginal Knowledge”, in Global Indigenous Media: Cultures, Poetics, and Politics, eds Pamela Wilson and Michelle Stewart (Atlanta: Duke University Press, 2008), 270–86; Terri Janke, “Indigenous Knowledge and Intellectual Property: Negotiating the Spaces”, The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 37, no. S1 (2008), 14–24.

11 Barwick et al., “Conundrums and Consequences”, 2.

12 Jason Gibson, Shaun Penangke Angeles and Joel Perrurle Liddle, “Deciphering Arrernte Archives: The Intermingling of Textual and Living Knowledge”, in Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel (Honolulu & Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2019).

13 Daniel Reed, “Reflections on Reconnections: When Human and Archival Modes of Memory Meet”, in The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, eds Frank D. Gunderson, Rob Lancefield and Bret Woods (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

14 We note that the opening chapters of McLean’s recent book focus on performance rather than visual arts. However, McLean states that the outlawing of corroborees after the nineteenth century means that his focus shifts back towards his chief research topic – visual art practices rather than performative ones. Ian McLean, Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2016); Nicholas Thomas, Possessions: Indigenous Art, Colonial Culture (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1999); Sandy O’Sullivan, “Reversing the Gaze: Considering Indigenous Perspectives on Museums, Cultural Representation and the Equivocal Digital Remnant”, in Information Technology and Indigenous Communities, eds Lyndon Ormond-Parker, Aaron Corn, Cressida Fforde, Kazuko Obata and Sandy O’Sullivan (Canberra: AIATSIS Research Publications, 2013); Sally May, Collecting Cultures: Myth, Politics, and Collaboration in the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition (Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press, 2009).

15 Kirsten Thorpe, Shannon Faulkhead and Lauren Booker, “Transforming the Archive: Returning and Connecting Indigenous Repatriation Records”, in The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Repatriation: Return, Reconcile, Renew, eds Cressida Fforde, Timothy McKeown and Honor Keeler (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2020).

16 Courtesy NT Archives, Darwin – Doorway to Australia (1949), C809, 1139364, Northern Territory Archives, Darwin.

17 AIATSIS, “Songs and dances from Bathurst Island, Yirrkala and Daly River performed at the Aboriginal Theatre in Sydney in 1963”, audio recordings, ELIZABETHAN_01; NFSA, The Never Never Land, film, Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, Artransa Park Film Studios, 1964, 10092, National Film and Sound Archive.

18 NFSA – Lee Robinson, In Song and Dance, Film Australia, 1964.

19 Although the AIATSIS recordings have been shared around the Tiwi community they were released to the 11 individuals in 11 hard copies and so those individuals are still regarded as the custodians of the material.

20 Charles William Merton Hart, “Fieldwork Among the Tiwi, 1928–1929”, in Being an Anthropologist, ed. G. Spindler (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970).

21 These were made using found iron objects the Tiwi group recognised as coming from ships/shipwrecks. They gave oral accounts of shipwrecks and of iron from Sulawesi being traded by Makassar peoples to the Tiwi since the seventeenth century, long before it was introduced by the British. Among the ethnographic recordings of Tiwi song are mentions of Makassan boats and the old Tiwi language includes some words likely borrowed from Portuguese via visitors from Indonesia.

22 These decisions were made referring to the current Tiwi Dictionary and opinions of speakers. Lee, Jennifer. “Tiwi-English Interactive Dictionary”, from Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL) Interactive Dictionary ed. Maarten Lecompte (for interactive version), 2011. http://203.122.249.186/TiwiLexicon/lexicon/main.htm. For more on lexical change, see Jennifer Lee, Tiwi Today: A Study of Language Change in a Contact Situation (Canberra: Australian National University, 1987).

23 There are references (Simpson 1951; Holmes 1995) to ritual paraphernalia being “sold” to visitors at the conclusion of ceremonies in which they were used. This correlates with traditions of creating ceremonial objects afresh for each event, and that spears were often used for non-ritual contexts (hunting or fishing) after they were created for ceremony.

24 Due to lexical change following Pukumani restrictions on words associated with the deceased and the impact of the introduction of English, the Tiwi language has undergone significant change over the past century. See Lee, Tiwi Today.

25 The Hart recordings were repatriated after the 2009 Tiwi delegation to Canberra.

26 Kulama, traditionally held annually (at the beginning of the dry season) is an initiation and well-being ceremony. An explanation of Kulama’s multi-layered and complex functions is beyond the scope of this chapter (see Genevieve Campbell, “Sustaining Tiwi Song Practice through Kulama”, Musicology Australia 35, no. 2 (2013), 237–52). Pertinent here is that one of Kulama’s ritual stages is the vehicle for marking current events and important news through song. Kulama songs among the recorded archive include topics such as Macassan boats, storms causing damage, mission houses being built and the moon landing in 1969.

27 “Aborigines Thrill Big Crowd with Dance and Ritual”, Northern Standard, 23 April 1948, 5, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49984700; “Death Dance Star Mobbed in Darwin”, Courier-Mail, 19 April 1948, 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49666240; “A Royal Tour Disappointment”, West Australian, 20 April 1948, 6, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article46904700.

29 The turtuni, more commonly referred to in the literature as Pukumani poles, are large decorative poles carved from tree trunks and painted with intricate ochre designs that form the centrepiece of mortuary-related Pukumani ceremonies. They stand as “grave poles” either at the actual site of burial or in the Country of the deceased (this having changed over the last century due to the logistics and regulations of townships and the introduction of Catholic cemeteries).

30 Ethnological Museum Anima Mundi, “Pukumani grave posts”, accessed 24 June 2021, http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-etnologico/collezione/pali-funerari-pukumani.html.

31 In 2009, 87-year-old Margaret Tuckson († wife of the late Tony Tuckson) met with a Tiwi group at the AGNSW to view the poles together. It was a meaningful experience for the group and for Mrs Tuckson, who recalled the impact of the commission in 1958 and what it meant for the art gallery and for Indigenous Australian art in general. The group was able to make a couple of small corrections to the displayed information accompanying the exhibit, including correcting the attribution of one artist’s name.

32 Wurringilaka (Corymbia nesophila – Melville Island bloodwood), endemic to the islands, has been replaced to some extent in recent years by Kartukini (Erythrophleum chlorostachys – ironwood) for carving due to its durability and accessibility.

33 The Tiwi performers were Christopher Tipungwuti, Bennie Tipungwuti, Valentine Pauitjimi, Daniel Pauitjimi, Barry Puruntatameri, Noel Puantalura, Declan Napuatimi, Conrad Paul Tipungwuti, Freddie Puruntatameri, Matthew Woneamini, Eddie Puruntatameri, Walter Kerinaiua, Hector Tipungwuti, Felix Kantilla, Raphael Napuatimi, Justin Puruntatameri, Timothy Polipuamini. Press Release: “45 Aborigines to arrive on Sunday for Sydney Presentation”, 28 November 1963, Box 51, Folder 66/1 (Administration) Aboriginal Theatre & Exhibition, Records of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, MS 5908, NLA.

34 (Mountford 1958) and AIATSIS audio recordings C01-002916 through C01-002918.

35 Lee Robinson, In Song and Dance, Film Australia, 1964, courtesy of NFSA. Thanks to Colin Worumbu Ferguson and Jordan Ashley for identifying Rusty Moreen in the film.

36 AIATSIS audio recordings S02_000181A through S03_000187B and Sandra Le Brun Holmes, The Goddess and the Moon Man: The Sacred Art of the Tiwi Aborigines (Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman House, 1995).

37 The ceremony was held in Darwin because the child had died in Darwin en route to hospital.

38 Sandra Le Brun Holmes, The Goddess and the Moon Man: The Sacred Art of the Tiwi Aborigines (Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman House, 1995), 31.

39 Holmes, The Goddess and the Moon Man, 22.

40 Holmes, The Goddess and the Moon Man, 29.

41 Translation provided by Tiwi speakers (the film gives no translation). Ted Evans was the Northern Territory chief welfare officer at the time.

42 Mary Elizabeth Moreen was in the delegation to Canberra and viewed the Macleay Collection in 2009. Unfortunately she is now too unwell to travel but has been involved in discussions of the collection from her home.

43 We had no footage of this, but Regina talked about coming to Sydney to perform in it, and we have since returned photos from her media interviews about the show to her. “Ballet of the South Pacific”, Australian Women’s Weekly, 1 April 1970, 25, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47814074. The full cast of Australian performers was: Irene Babui, Regina Portaminni, Simon Tipungwuti, Mathew Wonaeamirri, Edward Puruntatameri, Leon Puruntatameri, Frederick Nanganarralil, William Calder Nalagandi, Jackson Jacob, Larry Lanley, Gordon Watt, Arthur Roughsey, Yangarin Kumana, Nalakan Wanambi, Munguli Monangurr, Cyril Ninnal. Program for Ballet of the South Pacific, Subject file: Ballet of the South Pacific – Programs and Posters, Beth Dean and Victor Carell Papers, MLMSS 7804/10/7, SLNSW.

44 A Tiwi delegation also performed at the 1976 Pacific Arts Festival in Rotorua.

45 Program of Ballet of the South Pacific in James Cook M. Ephemera – Box 2 – (1900– ), SLNSW; and Richard Beattie, “Aboriginal Girls to Dance in Sydney”, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1970, clipping in Carell, Victor – Proposed ballet of the South Pacific, A2354 1969/289, NAA, Canberra.

46 Tiwi men’s ceremonial dress of nagas, loin cloths, was added in the early twentieth century with the arrival of the missionaries, while women and girls were put into skirts. European dress then became the norm. The establishment in 1969 of the Bima Wear screen printing and sewing cooperative on Wurrumiyanga (Nguiu), Bathurst Island, created dresses decorated with Tiwi designs that the Tiwi women wear today as a form of cultural dress, but in the 1960s there was no specific “traditional” dress for Tiwi women.

47 Now, at the age of 67, Regina is the most outgoing of the women on stage, often taking lead dancing roles.

48 The woman who died was the direct sister of one of the group and a classificatory sister to all of them.

49 C.W. Hart audio. AIATSIS collection C01-004240B-D33.

50 See also Dunbar-Hall and Gibson’s discussion (following Ellis) of hymns as a continuation of the sacred function of music in the cultural practice of many Aboriginal people. Peter Dunbar-Hall and Chris Gibson, Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music in Australia (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2004), 42.

51 From promotional material prior to the Sound Lounge performance, http://sydney.edu.au/environment-institute/events/tiwijazz-ngarukuruwala-sing/.

52 Calista Kantilla, Elizabeth Tipiloura, Katrina Mungatopi, Frances Therese Portaminni, Gemma and John Louis Munkara, Regina Kantilla and Augusta Punguatji.

53 The two other spears have no confirmed artist or age. They are “very old” according to Calista. They bear a close similarity to those in the collection, which was of great interest to the group.