5

The body is an archive: Collective memory, ancestral knowledge, culture and history

The body is an archive

Download chapter 5 (PDF 2.7Mb)

Positionality

In order to properly position myself within the context of this chapter, I need to introduce myself so that I might be recognised by other Native people, other Haudenosaunee, other Onöndowa’ga:’ (Seneca), by the Creator and by the other living beings of this natural world. My name is Rosy Simas Dewadošyö’ (get ready for winter). I am of the Joäshä’ (Heron) clan of the Onöndowa’ga, who are one of the Six Native Nations of the Haudenosaunee.

As a Haudenosaunee, I am keenly aware that it is not my place to write or speak as an expert on our culture and customs. That is a role reserved for faith keepers, clan mothers, chiefs and scholars who have been given permission from Haudenosaunee leadership to do so. Rather, I describe in this chapter how the tradition of oral storytelling relates to wampum, and how my body is an archive. I call upon my first-person experience through a self-reflexive and autoethnographic approach and I cite those whose role it is to talk on Haudenosaunee culture with expertise.

It is my responsibility as a Haudenosaunee, a Seneca, as a Native artist and an independent scholar who is committed to living in relationship with the natural world to attend to the ways in which I engage with the institutional structures that exist within the world of the arts and academia. I do so by maintaining holistic and accountable relationships with other Native people, with my family and with my ancestors. As a result, this responsibility directly influences the ways in which I investigate, analyse, consider and conduct my research, both as an arts practitioner and an independent scholar. That responsibility and obligation is reflected here, within this chapter.

In addition, I want to acknowledge and thank those who have helped me think on this subject and encouraged me through the process of writing this chapter: editors Amanda Harris and Jakelin Troy, dance scholars Ananya Chatterjea, Sam Aros Mitchell and Jacqueline Shea Murphy.

Introduction

I consider my body to be an ever-evolving archive. I am a Native artist who generates performance and visual artwork from intersensory listening, to create transdisciplinary art to intentionally connect with audiences through movement, images, sound, metaphor and narrative. I also believe that this kind of work I do, an approach I liken to other Indigenous transdisciplinary artists, is paramount to the survivance of Indigenous people. Gerald Vizenor, in his book Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance, describes survivance as an “active sense of presence, the continuance of Native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name. Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry”.1

I propose here that Haudenosaunee knowledge and storytelling–imparting practices, by Haudenosaunee and for Haudenosaunee, are complete sensorial experiences which are critical to the cultural revitalisation and survival of communities. In this chapter, I will explore how these sensorial practices are a holistic part of growth of the familial, ancestral, historical and cultural archive within the physical bodies of the community. I describe how longstanding Haudenosaunee knowledge–imparting practices, which include oratory, wampum, oral storytelling and recitation, are all repetitive energetic forms for telling, sharing and understanding. In the writing of this chapter, I have considered the differences between scholarly archives that have been violent towards Indigenous peoples and the Indigenous archive, which, through a process of conceptualisation, re-Indigenises space and builds possibility for connection and healing for and between Indigenous bodies. Lastly, I describe how my work has oscillated between the archive/archives, the colonial archive and the Indigenous archive, and how this has manifested sites for healing and connection, both for me and for the communities with whom I share these practices.

Archive/archives

This concept of my body as an ever-evolving archive presents several challenges within the world of academia and art. Here I use the word and concept of “archive” as a way of defining the source of resilience and healing, and yes, survivance that comes from the wisdom, strength and empathy of our ancestors, family and community. I recognise that many scholars have written about the “archive” and the subsequent relationship to the body. For one, Diana Taylor in The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas2 has illuminated the repeated scenarios of settler-colonial discovery and conquest, which continue to haunt the Americas to this day. Taylor has called to attention the polarities that exist between the written word and embodied practice as well as between the settler valorisation of the textual body and the Indigenous understanding of the body. Yet these concepts remain stuck, trapped behind a binary that allows for little intervention.

I also recognise Ohlone Costanoan-Esselen and Chumash poet and scholar Deborah A. Miranda has even stated in her poetry that “My body is an archive”. In her book Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir3 Miranda performs an intervention between the colonial archive and the Indigenous archive, drawing attention to the ways in which the Indigenous archive carves out space for Native artists and scholars to continue to be in an intrinsic cultural and radical relationship with the world.

I am aware that within this globalised society, dance has recently gained prominence in academia, especially in the field of performance studies. Performance studies research of dance regards the conveyance of bodily knowledge and looks to the body as a fertile site of research engagement. As an art form, Western dance is bound up by Western cultural and educational ideologies. Researching Indigenous dance/movement art practices, contemporary or otherwise, through this research methodology just doesn’t work. What kinds of bodies in motion constitute “knowledge” when this art form is examined through these specific lenses? Whose bodies of work (and bodies, for that matter) are produced, valorised, researched and conveyed? Whose bodies are made invisible, excluded and forgotten?

My body/my archive

As an act of self-determination and resilience, I posit here that my Native body is indeed an archive, an ever-evolving part of the Native physical, spiritual and intellectual world. This archive or codex lives in relationality to the natural world and holds the power to decolonise, to heal bodies of land and water, while also possessing the ability to shift and change the contemporary spaces that we currently occupy.

In his book Hungry Listening xwélméxw (Stó:lō/Skwah), writer and scholar Dylan Robinson discusses the reclamation of Indigenous authority over scholarship through refusal. This refusal performs as a way to discontinue the contribution to limitations of settler-colonial views of Indigenous scholarship. In Robinson’s words: “This refusal functions as a corrective to the history of Indigenous knowledge extraction, misrepresentation and claiming of authority by settler scholars. In doing so, it returns authority to Indigenous people and re-emphasises the importance of language in the construction of knowledge”.4

The Indigenous body is not an archive to be “extracted” from, as has been the historical practice from Western scientists, scholars and those who settled on Turtle Island (North America) to steal from Indigenous people and return to Europe with their treasures. Despite settler colonialism’s multiple attempts to extrapolate the intellectual and spiritual resources of Indigenous people, the approach I take here stands steadfast as a refusal to those extractions.

It’s critical here to note the differences between “archive” and “archives” as constructed repositories of knowledge that contain historical documents and records. The “colonial archive” contains documents, maps and records produced by state or institutional agencies. My body as an archive represents my own experience, my own phenomenological encounters and my own histories, from a deeply corporeal space. By calling attention to these various archives, the capacity to create contemporary frameworks might be transformed through fostering an Indigenous holistic worldview, which ultimately can positively impact and influence all peoples.

The development of my creative process

About 10 years ago, I first came to understand that my body is an ever-evolving vibrant archive of genealogy, history, culture and creation. I realised how the movements of my childhood, of play, dance, ritual and ceremony – movements deeply connected to the earth – informed the very architecture of my body. As my bones were shaped by gestures, my senses became developed to receive and perceive information in culturally specific ways. Neurological pathways formed throughout my body, from experiences with family and with Elders. I found myself in a different relationship to nature than from those I was in school with. These movements were first imitated and then embodied. The origin, however, was from a deep cultural and physical groundedness.

Over the past two decades I have researched and developed methods to continue cultivating this deep relationship among my senses, physical experiences and nature as a means to create movement, images, text, sound and objects. I have performed this research myself as well as with others. My 2014 work, We Wait In The Darkness, exemplifies these claims and recuperates the Indigenous archive through this combined approach of deep listening, living in relationality with nature and intentional awakening of cultural memory.

From this work, memories awakened, my ancestors were evoked, and the rich culture and history of my people became revitalised through the act of deep listening. I contend here that it was through these multilayered sites of performance work, installations of visual art and immersive sound environments that an invitation came forth for deeper engagement. Through the process of creating this performance, past events were summoned, realised and understood. These events were ultimately transformed to become an act of healing and connection.

Haudenosaunee scholar Susan Hill (Wolf Clan, Mohawk Nation) and resident of Ohswe:ken (Grand River Territory) explains, “One of the Kanyen’keha words for clan is Otara; when one asks another what clan they belong to, the question literally translates to ‘what clay are you made of?’”5 Whether a Haudenosaunee knows the saying “what clay are you made of” or not, if they have learned movements passed down the generations through dance, games and physical work with family and community, those movements are powered by the force of gravity and its relationship with the substance of the earth.

In my dance workshops, I ask participants to use their imaginations to sense the fluid organic matter of their bodies that are made of the same substance as the earth. I ask them to imagine, through these sites of intentional communication, that the substances of their body can talk with and draw groundedness through the connection of reciprocity with the earth.

The archive of my body is also embedded with inherited historical trauma, epigenetic events that left chemical markers on my DNA from my grandmother and her grandmother. I have intuitively known that the memories I hold are not just my own. These memories are awakened through movement because they live within my body. Creating, for me, is a part of growing, understanding and healing.

Resmaa Menakem, an African American author, artist and psychotherapist who specialises in the effects of trauma on the human body and relationships, explains that painful memories are passed from generation to generation and that “these experiences appear to be held, passed on, and inherited in the body, not just in the thinking brain”.6 Through generative and grounded movements, these memories can be, as Menakem describes, “metabolized” and transformed.

For me, this “metabolization” becomes movement, gestures and expressions that inform all that I create and share with audiences.

The conceptual and physical process of working towards decolonising my practice includes an integration and utilisation of my somatic and contemporary dance training.

In teaching and creating dance, I work intersensorily and with movement that engages the whole person. This allows me to work with dancers holistically and develop movement that conveys directness, connectedness and strength. I contribute this connectedness in myself to my body’s archive that was encoded with memories of my ancestors, voices of my Elders, groundedness of those who taught me to dance around a pow-wow drum and the embrace of my mother, who was held by her mother, who was held by her mother.

When I bring these ideas into my work with others, I begin with the senses of touch, hearing and sight. By bringing awareness to these senses, I draw attention to their interconnectedness. I illustrate how this interconnectedness then becomes the body’s mechanism for listening.

In her chapter titled Intimate Strangers: Multisensorial Memories of Working in the Home, Paula Hamilton writes on “intersensoriality” and “that it is rare to experience only one sense at a time”. Hamilton quotes sensory scholar Steven Connor who argues that our senses are “inherently relational”; for instance, “the evidence of sight often acts to interpret, fix, limit and complete the evidence of sound”.7

Through the process of working intersensorily, this can be attended to. As movement engages the whole person, I have been able to work with dancers holistically, developing movement that conveys directness, connectedness and strength.

When one begins to explore a radical relationship with nature and other living beings, these “metabolised” memories can become expressions, gestures, healing and grounding movements. Within my creative work, and the work I do with others, this is shared with audiences.

Longstanding Haudenosaunee knowledge-imparting practices

Oratory speech, oral storytelling and recitation are all practices that are performed, repetitive, energetic forms for telling, sharing and understanding. These practices have been shared among the Haudenosaunee in Turtle Island since “the beginning time”, which is placed at the moment when Skywoman fell from the sky onto the turtle’s back.8 The Haudenosaunee oral transmission of stories is through the sensorial experiences of hearing, seeing, smelling, touching and tasting. Oratory speeches that share stories and histories from memory recur to be remembered and shared. This cultural practice is a complete intersensorial experience that works to embed meaning into the listener on a physical, spiritual and intellectual level.

The Haudenosaunee utilise wampum to interpret our stories, treaties and laws. Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh, a Condoled Bear Clan Mother of the Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation, describes the significance of wampum in Haudenosaunee history: “Wampum means white shell beads, which were originally used as a medium to console oneself in grief. Later, wampum belts were made to record and recognise agreements made by the Europeans.”9 Belts of wampum are considered living objects that need to be seen and physically touched by our communities in order to be alive.

As Haudenosaunee, we practise collective remembering, learning and creating through the senses. We need to touch the wampum and hear in Haudenosaunee languages the teaching/story of each belt or strand to ignite our collective memory. The whole body receives the experience and is changed. Collective memory is stored within the body of individuals within Native communities. As I have described Resmaa Menakem’s theory on metabolising inherited memories so we can heal from them, I suggest here that we inherit and can ignite intergenerational memories, which, in turn, may guide us to continually evolve our culture and connect to our ancestors, which ultimately is and always has been the key to Indigenous survivance.

Tying Haudenosaunee wampum interpretation practice to my own experience of awakened memory through my relationship with objects and artefacts for We Wait In The Darkness has brought up further questions for me. Looking at my own work and the work of other Native artists, I wonder how Native practices continue to awaken collective memory and move through the relationship with objects/materials, and how this might render the physical body as an archive of knowledge, wisdom and culture. How can a Native artist’s body also be a vehicle for healing and connection? How can such a body, living in radical relationality to the natural world, shift, change and decolonise performance, academic and institutional spaces?

Here I look to Indigenous studies scholars Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy and their introduction to a special issue of the journal Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, which describes “radical relationality” as a growing web that “blankets the world in stunning beauty and restores the balance that our stories and prophecies have always foretold”.10 I turn to Indigenous studies scholar and Goenpul woman of the Quandamooka Nation, Aileen Moreton-Robinson, who has described Indigenous methods of “relationality” as being “grounded in a holistic conception of the interconnectedness and inter-substantiation between and among all living things and the earth, which is inhabited by a world of ancestors and creator beings”.11 This holistic connectedness requires that we, through our bodies, have been and continue to be in relationship to our environment and other beings. We experience life via our senses, which inform our every physical, spiritual and intellectual move. It follows then that body-based artists, through developed methodologies, can create artwork intrinsically tied to, in response to, and with bodies sensorially in relation with the natural world, by weaving and connecting the legibility of the Native body between land and constellations, between story and body.

In the urban intertribal community in which I live, I have witnessed over many years radical relationality at work in the art practice of Native artist Dyani White Hawk (Lakota). In the 2017 TPT Minnesota Original documentary The Intersection of Indigenous & Contemporary Art, White Hawk explains how her creative process is underpinned by her physical (sensorial and spiritual) playing of “the Great Lakes form of the Indigenous game lacrosse”.12 This holistic connection looks to a medicine game, which, when played in relationship to other Native bodies and in nature, supports health, wellbeing and therefore, her practice. White Hawk strives to make “graceful, and poetic, and poignant” art that she hopes will attract viewers into “conversation through beauty” as an invitation “to talk about the intersectionality of our histories”.13 This is necessary, she explains, as the general population has not been exposed to the histories of Native people. In this way, White Hawk is creating her own web of radical relationality by influencing other Native artists and artists of colour in our community through her work, which is deeply connected to a practice that is based in a holistic relationship with the land, people and other beings of the natural world.

There is a shared connection to the approach that White Hawk describes here in my own work. Although we may work with different mediums, I believe the overlap becomes apparent. Throughout these interventions that White Hawk speaks of, which consider the phenomena of perception, we share a common approach. By deploying a de-centring and unsettling methodology, we share common values in what Dylan Robinson xwélméxw, Stó:lō scholar and settler scholar Keavy Martin describe as “aesthetic actions”. “Aesthetic action” stands in for a broad category of the ranges of sensory stimuli that include image, sound and movement. These stimuli have the potential for social and political change through critical and intentional engagement. Martin and Robinson state: “We believe this to be important because of the potential for embodied experiences to go unrecognized or unconsidered, even as they have enormous influence on our understanding of the world”.14

This intervention between people, spaces and land remains simultaneously dialogic, verbal and corporeal. It remains an investigation, between my body, my people and my own embodied culture. Yet there is an invitation for all to enter into these spaces. Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman’s book, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations, “charts women’s efforts to define themselves and their communities by interrogating the possibilities of spatial interventions” and discusses the labour of Indigenous artists and scholars who “(re)map” the “communities they write within and about … to generate new possibilities”.15 Goeman looks to the work of geographer Doreen Massey and her reflections on space, surmising that if place is considered to include a flow or fluidity which extends to the intangible and spiritual notions embedded within Indigenous practices, then for Goeman place possesses the permeability and potential to work “as a meeting place”.

Scholars and activists have posited that Indigenous land education must be regarded in its relationship to the legacies of colonial violence, which have in turn created a great need to rebuild relationships to land and to one another. For me, this significance is apparent. I believe it is through “aesthetic action” that I tacitly de-centre and unsettle this connection. As a result, the participants experience through these multiple, nuanced sites of aesthetic action a shock of recognition in which “interest, empathy, relief, confusion, alienation, apathy, and/or shock”16 becomes manifested, as Menakem has discussed.

Recuperating the archive: We Wait In The Darkness

Through living in relationship with and paying attention to these objects, through the practice of deep listening with my senses, the objects began to awaken memories. For me, cultural memories appeared as feelings, thoughts, words, images and colours. Through my practice of creating dance and visual art, the memories become expressions through gesture or physical action, and the weaving together of these movements became the dance.

In 2000, I began a custom of purchasing Seneca-made tourist-trade objects and memorabilia (baskets, beadwork, souvenirs) sold online with the intention of restoring them to my community in our cultural museum. Beginning in 2012, I shifted my focus primarily to maps and other historical documents defining Haudenosaunee territories from the positionality of the dominant European and then United States and Canadian governments.

In 2014, my body, memories, oral stories, familial objects and historical archives were all utilised in the creation of We Wait In The Darkness. In collaboration with French composer François Richomme, We Wait In The Darkness was a dance performance, a gallery installation and later a museum exhibition. We Wait In The Darkness, the dance, was a composition of gestures and generative movement that wove together time and space, to cross dimensions, to heal the historical trauma that scarred the DNA of my grandmother, her mother and our ancestors. The work premiered in Canada at Montréal Arts Interculturals (MAI) and in the United States at the Red Eye Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The dance toured the US and Canada, and was performed in Marseille, France.

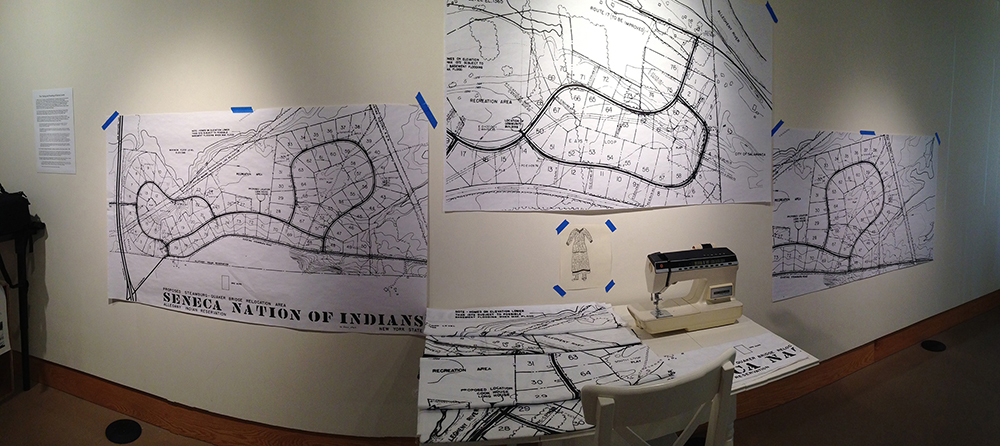

We Wait In The Darkness, the installation, contained textiles, moving images, moving sound and paper sculptures that created an environment in which I performed, as well as historical objects such as maps, and cultural and family artefacts. The installation originated at All My Relations Arts, a Native owned and run gallery in Minneapolis. The installation was shared with communities in Northern Minnesota and became a museum exhibition at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston, Illinois.

The dance and installation were produced simultaneously, each informing the other. My repetitive interactions with living cultural, familial and historical objects became an interactive dialogue generating movement vocabularies that became central to We Wait In The Darkness the dance. Choreography, story and memory inspired the contemporary art pieces for the exhibition and set design for the stage. All these physical acts of making dance and visual art guided how the exhibition was installed and contextualised. This work oscillated between the archive/archives, the colonial archive, my body as an archive and the Indigenous archive.

While creating We Wait In The Darkness, my body, spirit and mind were interpreting and processing memories and sensations. My body integrated this information in my bones, organs, muscles and memory, and as new neurological pathways. This new intelligence became a part of the architecture of my body and the archive of my body. The completed exhibition was an installation of historical, cultural and family objects that was in dialogue in the gallery with the contemporary art pieces that I created. My intention for the exhibition and dance was to create an experience for the audience from which they could integrate new understandings and sensations.

The exhibition included maps used to create a visual representation of the dwindling of the land of the Seneca over the past 400 years, and I wanted people to understand in a profound way, through their sense of sight, that the Haudenosaunee have experienced massive loss culturally and geographically because of the diminishing of their land. And that we remain deeply impacted by this history of loss to this day. I learned through my practice of pulling together over a hundred family, community, and cultural objects and archives that these material things are embedded with tangible memory and energy. Some of these pieces are living objects.

Each performance featured a 5-foot x 6-foot drawing of a section of a map replicated from a US Corp of Engineers map, which was created to relocate Senecas who would be (who were) displaced by the creation of the Kinzua Dam. Thirty minutes into the dance the sound ceases, and the audience hears me begin to tear the oversized map. The silence preceding the tearing is intentional to draw the audience nearer to me on stage – listening not just with their ears but with their whole beings. I carefully tear the boundary lines of each land plot on the map. I take the pieces and place them in various spots on the stage, distributing some of the torn plots to the audience. Both Native and non-Native people receive these pieces. Some people wonder what they are to do with this metaphorical gesture, some people are uncomfortable, having to think about what it means for them to hold a piece of Seneca land, plotted by the US government to be redistributed as a commodity, like canned meat, to be consumed.

I remember during the Minneapolis premiere handing two torn paper plots to a Seneca friend who had not inherited land on our reservation. In this exchange, I wished with my gesture that I could return her birthright to her, a place where she can be in relationship with the place of our ancestors. I have collected the torn pieces from the tour of over 30 presentations of the dance. These torn pieces will be repurposed once more and will become paper sculptures for another installation.

Figure 5.1 Rosy Simas tearing up an oversized Seneca Reservation relocation map during a performance of We Wait In The Darkness. Photo by Steven Carlino for Rosy Simas Danse, 2015.

Figure 5.2 Installation of fabric and paper of Seneca relocation maps for a traditional Seneca dress design, We Wait In The Darkness exhibition view, All My Relations Arts in Minneapolis. Photo by Rosy Simas, 2014.

Figure 5.3 Rosy Simas in an excerpt of We Wait In The Darkness at the Judson Memorial Church. Photo by Ian Douglas, 2015.

Conclusion

I posit that being a Native artist who is working in radical relationality does more than just interconnect me with others in the shared common goal of living in relationship with nature. It is by way of deep intersensorial listening that I awaken the culture stored within my archival body. I posit that in community with others, our collective memory actively contributes to the survivance of our specific Native cultures. I continue to demonstrate this through my own creative practice, and I am seeing it in the practices of other Indigenous artists.

Over the past 20 years, I have researched and developed approaches and methods to cultivate a deep relationship among my senses, physical experience and nature, which I use to create dance, sculpture, film and textiles. My research has led to the creation of dance and visual artwork that evokes my ancestors, taps into genetic memory, and brings me and those with whom I work into a vested relationship with the environment, as well as the issues of Native people and other living beings. The senses are key in my practice because it is through the senses that transmission is experienced. The repetition of such transmissions can generate energy which can exponentially grow into a web of radical relationality.

Through my dance-making processes, I have come to experience the ways in which energy works across realms of connectivity and relationality and to understand what this means. Energy is not bound by the same laws of physics as the beings who are confined by gravity seem to be. Energy can impact our bodies’ physiological systems. Dance educator and scholar Barbara Mahler discusses how “energy, which is a force that can be channelled through a conduit, when intentionally channelled through the skeleton system, has the potential to actually change the shape of our bones”.17

As a long-time student of Mahler’s, I am living evidence of how this channelling of energy through the skeleton can stabilise and ground the body, despite the years of destabilising postmodern and contemporary dance training I have had. What I have learned with Mahler, coupled with my own research, has made it possible for me to make work that connects with the energy of my ancestors. I am, the earth is, and nature are, the conduits through which the energy of my ancestors flows and connects.

Ancestors, not bound by space and time, are continually interacting with us. Their remains are literally supporting us as they have become a part of the earth we live on. We are not only influenced by these transmissions through the continued practice of deep listening, but we can also create from those experiences. In fact, by multiplying this energy through repetitive movement and actions we can build more energy, which can then be transmitted outward, further influencing the web of radical relationality.

The body, spirit and intellect interpret, process and integrate memories through the very act of creating and sharing. Through multiple We Wait In The Darkness performances and installations of the We Wait In The Darkness exhibition over four years throughout Turtle Island, an awakening in myself and the audience occurred. Multiple reiterations imitated the recitation of Haudenosaunee teachings that work to heal Native communities and honour our ancestors.

With each performance I was creating movement that generated new energy from an intentional relationship with my senses. The more the dance was shared, the more the story of my grandmother’s life and the tragedies that our people experienced were told; it was through this telling that healing has continued for me, the audiences who witnessed it (Native and non-Native) and my ancestors.

What I learned through pulling together over a hundred family, community and cultural objects, as well as paper documents, was that all of these objects are embedded with memory. Like the Haudenosaunee practice of touching and interpreting the living wampum, when the exhibition artefacts were touched or seen, collective memory was awakened and stored in the archives of our bodies.

References

Goeman, Mishuana. Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Hamilton, Paula. “Intimate Strangers: Multisensorial Memories of Working in the Home”. In A Cultural History of Sound, Memory, and the Senses, eds Joy Damousi and Paul Hamilton. New York: Routledge, 2016: 194–211.

Hill, Susan. The Clay We Are Made Of. Manitoba, Canada: University of Manitoba Press, 2017.

Mahler, Barbara. Klein Technique Workshop. Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2000.

Martin, Keith and Dylan Robinson. Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

Menakem, Resmaa. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas, NV: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

Miranda, Deborah. Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir. Berkeley, CA: Heyday, 2013.

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. “Relationality: A Key Presupposition of an Indigenous Social Research Paradigm”. In Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, eds Chris Andersen and Jean O’Brien. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2017: 69–78.

Robinson, Dylan. Hungry Listening. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Rodriguez, Jeanette with Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh. A Clan Mother’s Call: Reconstructing Haudenosaunee Cultural Memory. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2017.

Shenandoah, Joanne and Douglas M. George-Kanentiio. Skywoman: Legends of the Iroquois. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 1998.

Taylor, Diane. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert. Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1994.

Whitehawk Polk, Dyani. The Intersection of Indigenous & Contemporary Art, a Minnesota Original Twin Cities Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) documentary, 2017.

Yazzie, Melanie and Cutcha Risling Baldy. “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water”. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 7, no. 1 (2018): 1–18.

1 Gerald Robert Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1994), 12.

2 Diane Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

3 Deborah Miranda, Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir (Berkeley, CA: Heyday, 2013).

4 Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 22–23.

5 Susan Hill, The Clay We Are Made Of (Manitoba, Canada: University of Manitoba Press, 2017), 5.

6 Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathways to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (Las Vegas, NV: Central Recovery Press, 2017), 68.

7 Paula Hamilton, “Intimate Strangers: Multisensorial Memories of Working in the Home”, in A Cultural History of Sound, Memory, and the Senses, eds Joy Damousi and Paula Hamilton (New York: Routledge, 2016), 200.

8 Joanne Shenandoah and Douglas M. George-Kanentiio, Skywoman: Legends of the Iroquois (Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 1998).

9 Jeanette Rodriguez and Iakoiane Wakerahkats:teh, A Clan Mother’s Call: Reconstructing Haudenosaunee Cultural Memory (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2017), 22.

10 Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy, “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water”, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 7, no. 1 (2018), 11.

11 Aileen Moreton-Robinson, “Relationality: A Key Presupposition of an Indigenous Social Research Paradigm”, in Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, eds Chris Anderson and Jean O’Brien (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2017), 71.

12 Dyani White Hawk Polk, personal communication, 2021.

13 Dyani White Hawk Polk, The Intersection of Indigenous & Contemporary Art, a Minnesota Original Twin Cities PBS documentary, 2017.

14 Keith Martin and Dylan Robinson, Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016), 89.

15 Mishuana Goeman, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 3.

16 Goeman, Mark My Words, 109.

17 Barbara Mahler, Klein Technique Workshop (Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2000).