6

Reanimating 1830s Nyungar songs of Miago

Reanimating 1830s Nyungar songs of Miago

Download chapter 6 (PDF 1.8Mb)

Introduction

Miago (also spelled Migeo, Maiago, Migo or Myago) was a Nyungar (also spelled Noongar, Nyoongar or Nyoongah) man from the south-west region of Western Australia (WA) who joined the HMS Beagle’s expedition to the north-west of Australia in 1837–38 as an intermediary.1 His departure, exploits and return inspired the composition of two widely shared local Nyungar songs, the lyrics of which were recorded in the journal of colonist and explorer Sir George Grey.2 These lyrics are among the earliest records of Nyungar singing. Although the songs about Miago were widely known in the mid-nineteenth century, no musical notation was transcribed, and the melody has not been passed on to contemporary generations of Nyungar people.

The 1829 establishment of the Swan River Colony – today known as Perth, the capital city of WA – was the beginning of British settler-colonial expansion in the state and the subjugation of local Aboriginal people.3 Throughout the nineteenth century, longstanding Nyungar cultural practices of sharing news and memorialising important events in song nevertheless remained relatively widespread among the Nyungar of Perth and other Aboriginal groups across Australia.4 By midway through the twentieth century, the increasingly disruptive and restrictive by-products of settler colonisation had combined to dramatically diminish the vitality of the Nyungar language and many of its attendant singing practices.5

Community-directed Nyungar cultural revitalisation efforts since the 1970s have motivated a steady resurgence of Nyungar language and singing, particularly to accompany dance performances or in popular music settings.6 The 2016 Australian Census recorded just 475 Nyungar language speakers.7 Although this figure represents just 1.5 per cent of the Nyungar population, it demonstrates increased identification with the language, as only 212 speakers were counted in 2001. The 2020 National Indigenous Languages Report classifies languages into seven categories based on their vitality, from “safe” to “no longer spoken (sleeping)”.8 Based on these categories, the Nyungar language could be described as both “critically endangered”, with a few very senior people knowing and using Nyungar vocabulary, and “reviving/revitalising/reawakening”, as use of language items among younger speakers has substantially increased since the beginning of concentrated language revitalisation movements in the late 1980s.

Like language revitalisation, much Aboriginal music revitalisation work draws on archival records and audio recordings.9 Although historical records and contemporary memories frequently characterise Nyungar singing as a communal activity, existing accessible audio recordings of Nyungar song feature only “lone singers”.10 Most are “more akin to elicited memories than fully-fledged performances”.11 Still, Nyungar in recent decades have drawn on sparse archives for inspiration, grafting newly composed melodies onto historically recorded lyrics and developing group performance repertoire from audio recorded in the late twentieth century.12 Access to much of the written and archival audio record of Nyungar song is presently restricted in various ways, so much so that it is difficult to know the extent of the data. Table 6.1 provides a rough snapshot of the extent of recorded Nyungar songs from 1837 to 1986.

| Source | Original documentation of individual song texts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Written lyrics | Lyrics with musical notation | Musical notation with no lyrics | Audio recordings of performance | |

| Grey 1837–39 | 12 | |||

| Salvado 1953 | 1 | |||

| Chauncy 1878 | 1 | |||

| Calvert 1894 | 4 | |||

| Bates 1904–12 | 65 | |||

| Hassell and Davidson 1936 | 1 | |||

| Laves 1931 | Unknown (restricted access) | |||

| Hercus 1965 | 1 | |||

| Tindale 1966–68 | 6 | |||

| Douglas 1965–67 | 1 | |||

| Douglas 1968 | 1 | |||

| Brandenstein 1970 | 8 | |||

| Theiberger 1986 | 2 | |||

Table 6.1 Records of Nyungar song 1837–1986.

Additionally, from 1999 onwards anthropologist Tim McCabe made recordings of many songs with Nyungar speakers, including the late Cliff Humphries and Lomas Roberts. Although access is restricted to most of this material, some of the songs have emerged via language revitalisation initiatives.13

In 2020 I was commissioned by the City of Perth, WA, to compose music for Nyungar singer Gina Williams based on Nyungar lyrics about Miago from Grey’s papers (see Figure 6.1).14 Williams had released three albums of contemporary music with Nyungar lyrics alongside guitarist Guy Ghouse.15 The three of us had longstanding relationships as performers in WA and I had previously worked on various projects associated with Nyungar song and language, including Hecate, the first Shakespearean theatre production presented entirely in an Aboriginal language of Australia.16 The Miago project was supported and endorsed by the City of Perth’s Nyungar Elders Advisory Group and Edith Cowan University Nyungar Elder-in-Residence Roma Yibiyung Winmar. Its aim was to achieve some degree of fidelity between newly recomposed songs about Miago and conventions of Nyungar singing in the nineteenth century.

The creative process was underpinned by thorough investigation of Nyungar song. Making aesthetic decisions about how to reshape and sustain a musical tradition is fundamental to music revival.17 Decisions associated with recomposing the Miago songs depended on the development of a contextual, linguistic and musical framework. This chapter will provide an overview of the Nyungar singing culture and the history of Miago’s songs, before discussing Nyungar song creation, language and musical aesthetics. This description of the process associated with reanimating songs about Miago may inform future music revitalisation initiatives working with similarly endangered languages and song traditions.

Nyungar song culture

Manifesting in everything from ceremony,18 to popular music festivals,19 karaoke20 and radio requests,21 song and performance continue to be vital to Nyungar lifeways. Analysis of Nyungar terms for singing and historical records suggests multiple functions of song in Nyungar society of the nineteenth century, including laments, songs for dance and entertainment, news and gossip, identifying oneself, and arrivals and departures.22 While some Nyungar performance repertoire may be customarily restricted to particular audiences and participants,23 the wide variety of written descriptions of Nyungar performances in the nineteenth century suggests that a range of Nyungar singing practices – and even ceremony associated with maintaining landscapes and kinship – were openly practised and sustained despite the presence of colonists.24 In the twentieth century, entrenched settler colonisation of Nyungar lands, assimilation policies and an imposed emotional regime inhibited most speaking and singing in the Nyungar language.25 Up until the early 1970s, access to human rights for Nyungar people inherently depended on avoiding overt public cultural expressions such as song and language.26 Consequently, from the onset of colonisation until the late 1970s, opportunities to perform, hear and learn Nyungar songs were dramatically diminished.

Today, most Aboriginal performance traditions across Australia face pressing issues of endangerment. Returning archival recordings to their Aboriginal communities of origin has become a common research practice,27 but few of the communities involved in such work have endured prolonged disruption to song traditions akin to the Nyungar experience. Because Nyungar singing was suppressed and denigrated throughout most of the twentieth century, the contemporary performance of surviving songs carries significant emotional weight.28 Recirculating Nyungar songs among descendants of the deceased singers who were recorded performing on archival recordings and their broader local Nyungar community supports individual and collective identity maintenance and feelings of connection.29 In the apparent aftermath of the assimilation era, Nyungar songs – as performative expressions of culture – can also give rise to tensions associated with the politics of Indigenous cultural identity.30 As a result, some individuals or groups may seek to retroactively impose tight restrictions on previously “open” and unrestricted songs which may have been widely known and shared among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the past. However, senior Nyungar are generally proud to publicly share old songs today.

Songs of Miago

As part of the City of Perth’s online exhibition for the 150th anniversary of Perth Town Hall, the City of Perth’s Nyungar Elders Advisory Group decided that since the town hall site was recorded as being one of Miago’s camping spots,31 his story – and songs about him – should feature in the exhibition. By 1833, Miago had established himself as a mediator between Nyungar and colonists on the frontier. Historian Tiffany Shellam describes him as:

a Beeloo Nyungar man from Wurerup country, located around the upper reaches of the Swan River to the north of the Perth township. He had family and kin networks across the Swan and Canning river systems, which made it difficult for settlers to restrict him to a particular tribal group in their census reports and observations.32

Such was the ubiquity of song in Nyungar life during the early nineteenth century,33 singing is frequently mentioned in historical descriptions of Miago. In Meeting the Waylo, Shellam describes Miago’s song-making and legacy, including how Grey transcribed and interpreted songs performed by Miago and another Nyungar guide, Kaiber.34

During the Beagle’s Australian survey, assistant surveyor Lieutenant John Lort Stokes described him,

… gazing steadily and in silence over the sea, and then sometimes, perceiving that I watched him, say to me “Miago sing, by and by northern men wind jump up”: then would he station himself for hours at the lee-gangway, and chant to some imaginary deity an incantation or prayer to change the opposing wind … there was a mournful and pathetic air running through the strain, that rendered it by no means unpleasing; though doubtless it owed much of its effect to the concomitant circumstances.35

Grey wrote: “if a native [is] afraid, he sings himself full of courage; in fact under all circumstances, he finds aid and comfort from a song”.36 Miago sang not just to quicken his journey home, but also to express frustration and wrath. Stokes observed how after visiting Beagle Bay in the north of WA, Miago considered the way the local Nyul Nyul men examined his body to be:

An injury and indignity which, when safe on board, he resented by repeated threats, uttered in a sort of wild chant, of spearing their thighs, backs, loins, and indeed, each individual portion of the frame.37

Back at the Swan River colony, Grey transcribed a well-known “war song” likely to have been the same one Stokes described:

The men, when according to their custom they go walking rapidly to and fro, quivering their spears, in order to work themselves up into a passion, chant rapidly as follows:

U-doo Darr-na

Kan-do Darr-na

Miery darr-na

Goor-doo darr-na

Boon-galla darr-na

Gong-oo darr-na

Dow-all darr-na

De-mite darr-na

Nar-ra darr-na

Thus, rapidly communicating all the parts in which they intend to spear their enemies.38

Miago would have boarded the Beagle with a repertoire of songs from home. During the expedition, he likely composed new songs too.

Stokes questioned Miago regarding the account he intended to give his countrymen about the expedition, writing that:

His description of the ship’s sailing and anchoring were most amusing: he used to say, “Ship walk – walk – all night – hard walk – then by and by, anchor tumble down”.39

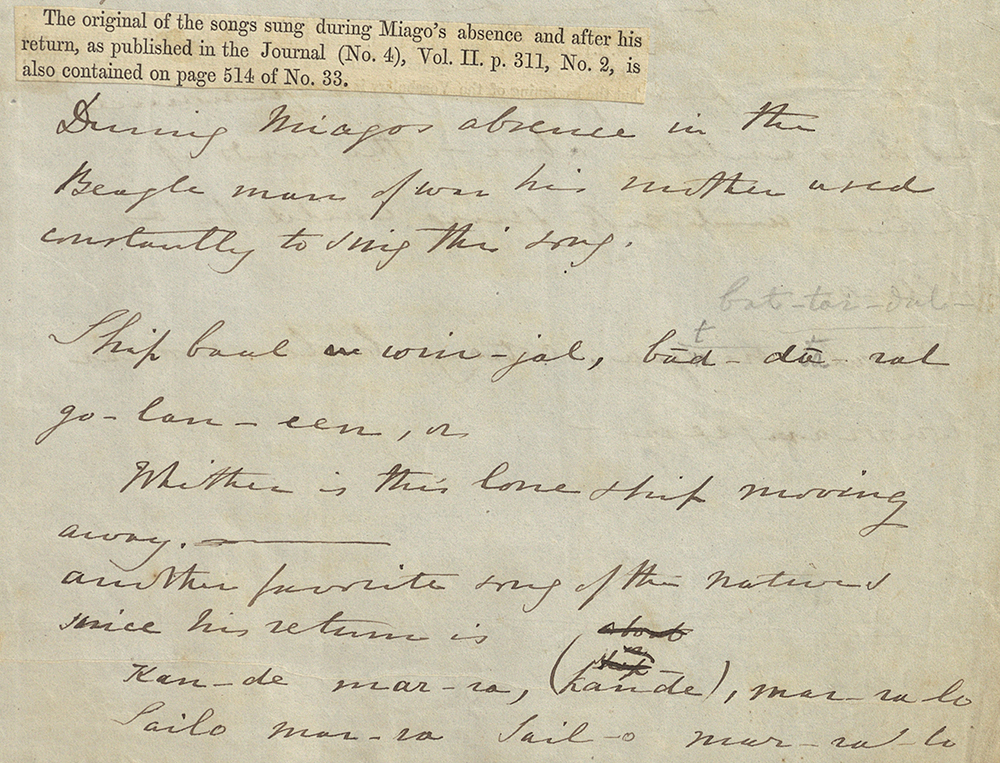

It is easy to imagine Miago’s composition about the journey delivered in the kind of “loud recitative” song that Grey cites as being the “customary mode of address” among Nyungar recounting current events in group settings.40 Miago’s departure and return also prompted other Nyungar to compose two songs which made “a great impression on the natives”.41 The lyrics are transcribed in Grey’s papers (Figure 6.1):

During Miago’s absence in the Beagle man of war his mother used constantly to sing this song:

Ship baal win-jal, bād-dā-ral

go-lan-een-

Whither is this lone ship moving away

Another favourite song of the natives since his return is

about a ship

Kan-de mar-ra, (kande), mar-ra-lo

Sailo mar-ra Sail-o mar-ral-lo

[Grey does not provide a translation of the second song]

Figure 6.1 Nyungar song lyrics about Miago in the papers of Sir George Grey. Used with permission from the National Library of South Africa, Cape Town.

For the purpose of this chapter, I will refer to these two songs as the “ship song” and the “sail song”. Considering the apparent popularity of these songs in the mid-nineteenth century, it seemed fitting to revisit them today as part of a public exhibition focusing on Miago.

However, presenting these songs as mute text in Grey’s handwriting seemed to reify them. Ethnomusicologist Gary Tomlinson goes so far as to suggest that the act of writing down an Indigenous song is tantamount to its colonisation; it reduces and enshrines it in written form according to an imperialist’s narrow interpretation, and consequently traps it as an artefact of the past.42 Meaningfully bringing these songs into the present demanded singing them again in a way that paid homage to Nyungar singing aesthetics while simultaneously aligning with contemporary language revitalisation goals in the Nyungar community. Rather than simply lifting something out of an archive, the objective here was to reanimate it with a sense of purpose.

Reanimating the archive

Engagement with the sparse and fragmented Nyungar song archive reveals two interrelated issues. Firstly, the Nyungar song archive is far from comprehensive. Most traces of Nyungar song in historical archives are merely written records of lyrics rendered in a variety of unreliable orthographies.43 Very little historical music notation of Nyungar song exists and the few accessible audio recordings of Nyungar singing made since the late 1960s feature what would mostly be described as “rememberings” of songs, rather than fully-fledged performances.44 Despite a few notable exceptions, it is rare for Nyungar people today to sing old Nyungar songs learned from Elders. Without much musical material from which to draw, we cannot be sure exactly how the Nyungar words written down by colonial observers would have sounded when they were originally performed.

Analysis of the small dataset of Nyungar song has resulted in rough conclusions about stylistic conventions typical of Nyungar vocal music.45 While these ideas could function as a starting point for attempting to graft appropriate melodies onto archival lyrics, operating with so little source data increases the danger of reifying a once dynamic and adaptable song tradition. Consequently, finding ways to sing these lyrics about Miago could not rely on analysis of the archive alone. The task demanded investigation of not just aesthetics but also characteristically Nyungar processes of composition.

Accounts of Nyungar song and many studies of Aboriginal music elsewhere refer to singers receiving songs while in dream-states.46 Based on her ethnographic work with Nyungar in the early twentieth century and revealing the esoteric nature of Nyungar songs composed in dreams, Daisy Bates states that in some cases where this occurs, the person who received the song may not be able to reveal its meaning. Bates describes Ngalbaitch of Jerramungup explaining the process of a Nyungar singer trying to find a song, stating:

they seem to hear it coming into their ears and going away again, coming and going until sometimes they lose it and cannot catch it. The jannuk (spirit) will however fetch it back to their ears.47

Providing an example of this process in the early twentieth century, Bates writes of Nyungar singer Bandoor dreaming a song one night, and learning it the following day.48 Anecdotal reports state that dreams also inspire many classical popular composers;49 Vogelsang et al. demonstrate that “being creative in waking-life is reflected in creativity in the dream”.50 The general prominence of song in Aboriginal life may partially explain the seemingly high propensity for new songs to reveal themselves in dreams among Aboriginal singers.51 However, even in recent years, as old Nyungar songs are rarely heard, certain Nyungar individuals occasionally describe receiving or dreaming about old-style Nyungar songs they attribute to ancestors.52 Employing what could be described as an Indigenous method,53 perhaps I needed to wait for the music for these old words to reveal itself.

Nyungar song language

Across many regions in Australia, Aboriginal people may readily sing songs originating from distant locations, in languages they may not necessarily comprehend.54 However, in past work with Nyungar song, senior community members “instructed that the first step in a process to get these songs performed again should involve developing a more solid idea of what the songs mean”.55 In support of this aim, I compiled a dataset of Nyungar wordlists to assist in translating archival songs. Study of Aboriginal languages such as Nyungar – in various states of critical endangerment or revival – frequently involve working with idiosyncratic and inconsistent wordlists originally collected by non-linguists who rarely understood the complexities of the language they were documenting. Working with historical Nyungar language sources also demands consideration of differences due to dialect, orthography, borrowings (the use of English near homonyms), cognates (words with a similar form and meaning),56 misheard sounds and incorrect glosses.57

As part of the process of reanimating the two songs of Miago from Grey’s journal, developing a deeper understanding of the lyrics seemed a suitable starting point. Cross-referencing Grey’s original and published versions of the songs alongside the Nyungar wordlist dataset revealed both inconsistencies in interpretation of and insights into Nyungar poetics. Grey’s original diary entry for the “ship song” provides the English interpretation of the text only as “Whither is this lone ship moving away”.58 His Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery was published in 1841 and expands on this with seemingly greater creative licence:

Whither does that lone ship wander

My young son I shall never see again

Whither does that lone ship wander.59

Analysis of the Nyungar language lyrics reveals that Grey has embellished the second line of his interpretation, as the original Nyungar lyric does not mention “seeing” or any kind of temporal concept. The Nyungar lyrics simply ask “win-jal” (where) “baal” (it, the ship – in English) is. The term “bād-dā-ral” is variously translated as “lone-wild, trackless”,60 a “barren tract of land”,61 “waste, a; barren land utterly destitute of vegetation”62 and “wild, desolate”.63 The final term, “go-lan-een”, based on Grey’s interpreted “young son” likely derives from “koolang” (child), with an additional suffix or non-lexical extension “-een”. This term could also feasibly be “koorlaniny” (moving continuously). The lexical ambiguity here could be purposely poetic.

In Grey’s original record of the “sail song”, the words “about a ship” are written and crossed out above the term “kande”.64 Grey’s 1839 wordlist has the same term: “kan de: move unsteadily, as a ship”. In both cases, “kan” (or “ken”) is dance, stomp or step and “de” seems to be a poetic addition.65 Grey’s published journal includes the interpretation “unsteadily shifts the wind-o, unsteadily shifts the wind-o, the sails-o handle, the sails-o handle-ho”.66 It seems like the ship is dancing in the wind. “Mar” or “maar” is both “hand” and “wind” (which may possibly be more accurately rendered as “maarr”), so there may be polysemic poetics at play.

Although there is no recorded audio of the Miago songs, most of the lyrical terms featured in the songs are present on the earliest audio recordings of Nyungar language elicitation from 1960 onwards,67 and are spoken by experienced Nyungar speakers today, showing no dramatic change in pronunciation over 60 years. Although sibilant sounds are absent from the Nyungar language, they are present in both songs at the onset of English-language words “ship” and “sail”. In his original notes, Grey has seemingly corrected these terms to conventional English spelling rather than represent them phonetically in the manner that Nyungar of the 1830s may have pronounced them. In his subsequently published journal, Grey has rendered the lyric “sail” as “tsail”, demonstrating Nyungar adaptation of sibilant sounds. While it is difficult to determine exactly how Nyungar of the 1830s would have pronounced the remaining Nyungar-language lyrics, the degree of fidelity between Grey’s original notes, the early recorded audio and contemporary speakers does not suggest a significant shift. Nevertheless, as Nyungar language pronunciation is fundamentally different to English, the sounds of the language are crucial to sustaining a classic Nyungar song aesthetic. Whether Aboriginal or not, for anyone who primarily speaks English, a language with mostly front-of-mouth sounds, it can be very challenging to create the back-of-mouth sounds typical of Aboriginal languages like Nyungar.68

Modes of Nyungar song

After consideration of lexical meaning and pronunciation of the Nyungar text, the next step involved creating an appropriate musical setting for the lyrics. Nyungar music is primarily vocal, so consideration of vocal timbre is equally as important as matching the melodic, rhythmic and structural characteristics of recorded songs from the past in attempts to maintain a distinct Nyungar musical style. According to Hugo Zemp,69 “nothing is more characteristic of a musical style than vocal timbre, for a few seconds may be more than enough to identify the origin of a song”. Grey’s early description of singing practices in the early colonial period starkly contrasts European and Nyungar aesthetic vocal preferences:

A native sings joyously in the most barbarous and savage sounds … while the surrounding natives loudly applaud, as soon as the singer has concluded. But should the astounded European endeavour to charm these wild men by one of his refined and elegant lays, they would laugh at it as a combination of silly and effeminate notes …70

Nyungar singers did not strive to produce the forward-projected, restrained vocal sounds common to nineteenth-century music in Britain. Much Aboriginal singing can be characterised as “back-projected”, with the resulting sound resonating through the body and sometimes the ground too, when performers are seated. Based on his work with Aboriginal performers at Belyuen in the Northern Territory, ethnomusicologist Allan Marett reveals that “one of the most important things that an apprentice song man learns from his teacher is to imitate the teacher’s voice” and describes confusion over the identity of recorded performers due to multiple singers also possessing “the same voice”.71

Despite the broad divisions applying to classic Aboriginal performance genres from different geographical regions,72 and the range of musical sub-types associated with cultural and social delineations, classic Aboriginal song styles in Australia are “obviously more related to each other than to anything outside the continent”.73 Indeed, Stephen Wild suggests, “it seems that Aboriginal music across Australia consists of variants of a common underlying type”.74 Generally, classic Aboriginal music is primarily vocal and most traditional instruments are percussive.75 Tunstill states that more often than not, this music “needs communal effort to produce it”.76 Furthermore, sung melodies usually begin “high and loud”, before “descending to a reiterated low soft note”,77 and vocal rhythm is “most often syllabic”.78

Despite this general similarity, it would be tokenistic to create new music for archival Nyungar songs relying only on general “superficialities: a descending melody, a regularly repeated stick beat”, while remaining ignorant of “structural intricacies”.79 Analysis of historical descriptions of Nyungar performance and 19 more recent examples recorded between 1965 and 2015 distinguish Nyungar songs by a number of features but also suggest a breadth of aesthetic possibilities.80 Nyungar songs exhibit a range of structural characteristics which imply the existence of multiple song genres and a significant degree of flexibility in the song tradition. Although some of the vocal rhythms in Nyungar songs are syllabic, helping to emphasise a strong regular beat, others are relatively melismatic and rhythmically complex.

The contrast between Nyungar songs that imply a steady “danceable” rhythmic pulse and those that feature far less stable, “expressive” timing suggests the existence of two basic “types” or “modes” of Nyungar song. Those outlining a regular beat would more readily be accompanied by dance and percussive accompaniment and could be performed by a group of singers with minimal need for cues and memorisation. Although no presently accessible archival audio recordings of Nyungar song feature examples of group singing or instrumental accompaniment, historical literature refers to both.81 As we discovered in singing workshops held across 2017–19,82 a number of more “expressive” songs in the Nyungar archival collection are difficult for more than one performer to sing as they utilise vocal melisma, significant tempo rubato and complex metre. These features are particularly characteristic of six songs performed solo by renowned Nyungar singer Charlie Dabb and recorded at Esperance, WA, in 1970.83

All presently accessible archival recordings of Nyungar song are solo performances – or “rememberings”. However, rhythmic features of a particular Nyungar song could characterise it as either a more “danceable” or “expressive” piece and imply the likely corresponding “group” or “solo” nature of its intended performance context. Still, these proposed modes of Nyungar song need not be exclusive. Demonstrating how the “expressive/solo” and “danceable/group” modes may be combined in a single piece, Daisy Bates describes informal performances at night by Nyungar who gathered to perform at the Perth Carnival in 1910. She outlines interactions between Nyungar man Nebinyan, as a “lead” singer, and the rest of the group, who “join in” at specific moments:

The recitative or song was always commenced by Nebinyan alone, the others only joining in the chorus, so to speak, or keeping up a sort of murmuring accompaniment throughout the melody. Weird and strange they sounded in the stillness and darkness of the night. The natives had rolled themselves in their rugs, but as the old man warmed to his task, and as the memories of early days crowded upon him, lending to his poor cracked voice a fictitious energy, one by one the others sat up and joined their voices to his in harmony. Presently the old voice took a minor key, and I watch the singers literally drone themselves to sleep as the old man’s song gradually trailed off into silence.84

Although Bates – untrained as a musician – uses the word “harmony”,85 based on the nature of most Aboriginal song I am inclined to interpret this as meaning “unison” or perhaps octave harmony. Furthermore, in light of this description, it is entirely possible in that in “soloist” sections of group performances, “lead” singers utilised the more “expressive” elements of Nyungar song including rubato, increased rhythmic complexity and occasional ornamentation.

Grey describes the songs about Miago as being popular and widely known; however, he describes only solo performances of these songs and never mentions accompanying dance. It is feasible to conclude that both songs about Miago were more likely to have been performed in the more rhythmically complex “expressive/solo” mode. This informed the decision to feature complex meter in creating new melodies for the songs about Miago. In addition to abiding by the conventions of these theoretical modes of Nyungar song, using complex meter rather than common time automatically distinguishes the songs about Miago from most of the music heard in Australia today.

Nyungar tunes

Bates’ recollection of Nebinyan switching from singing in what was presumably a major key to a minor key is reasonably significant, given the lack of historical descriptions of Nyungar melodies. The recollection of early Western Australian pastoralist Janet Millett that Nyungar “songs were always in the minor key” is of dubious value,86 as she also claims to have never observed Nyungar using percussion instruments, suggesting that she witnessed only a few select performance types. Furthermore, the melodic variety evident among recorded examples of Nyungar songs indicates that former Western Australian “Protector of Natives” Jesse Hammond’s statements that “[t]hey only had about three of four different chants for their dancing” and “[i]n their ordinary singing too, though they had various words, the tune was nearly always the same”,87 could also reflect narrow experiences with the gamut of Nyungar performance and – as is typical of colonial descriptions of Indigenous performance – limited musical knowledge.

Recorded performances of Nyungar song from 1965 onwards all demonstrate a clear tonal centre and loosely diatonic pitch relationships which would usually suggest a “major” key.88 Both “major” and “minor” tonalities are suggested by the six pieces of notated music inspired by, or attempting to faithfully record, Nyungar singing in the nineteenth century.89 Chauncy notates a “morning song” performed by Nyungar on the Swan River in the “key” of C, but the melody features a flattened sixth and seventh, implying a “minor” flavour.90 While providing a very sparse representation of a musical tradition, these notations support the general conclusions upon listening to audio recordings of Nyungar performances that classic Nyungar songs may evoke major and minor tonalities and feature anything from two or three different repeated pitches to more nuanced melodies employing five or six note “scales”. In keeping with the practicalities of the previously discussed solo and group “modes”, rhythmically complex Nyungar songs are likely to feature a degree of complementary melodic complexity.

Some of the recorded Nyungar songs with more complex melodies conclude by falling in pitch to an octave below the implied “tonic”. Bates provides a description for one of Nebinyan’s songs about a whaling expedition which closely matches the structural and melodic character of three songs about the sea performed by Charlie Dabb,91 all of which use complex meter, triplet rhythms and rubato to invoke the flow of the ocean and feature this “octave drop” technique. In her notes, Bates states:

The tune of this song was in utmost “harmony” with the words of the song. Sung in a low voice, it represented the voices of the great waves, the great seas as they murmured along shores = Goomba warrin in a very low and slow bass ended the song.92

Bates’ use of the term “harmony” in the context of describing solo vocal performance indicates that she had an affective rather than technical understanding of the term. This form and structure may be characteristic of a song genre Bates implies when stating that “[m]ost of the seacoast tribes have their own songs of the sea”.93 While the “octave drop” is also featured in other Nyungar songs without ocean themes, this melodic feature seems appropriate for the sea-based songs about Miago.

As is common in Aboriginal music of neighbouring regions, examples and descriptions of classic Nyungar song considered in this study indicate the prevalence of repeated melodic contours concluding with a descent in pitch.94 Most Nyungar songs are relatively isorhythmic, overlaying repeated text and vocal rhythms with different alternating and mostly descending melodic contours. Due to the rarity of strophic songs in the recorded examples of Nyungar song, even lyrically simpler songs with only one or two lines of text, like the songs about Miago, were still likely to have been isorhythmic. The fidelity between audio recordings of one song performed by Nyungar singer Charlie Dabb in 1970 and then Gordon Harris in 1986 provides evidence of the fixed, rather than improvised, nature of at least some Nyungar song items.

Reanimation

Analysis of a broad, scattered sample of Nyungar vocal music captured in audio recordings (1965–2014) and also represented in nineteenth-century musical notation indicates that a significant degree of melodic and structural variety is characteristic of classic Nyungar song genres. As noted by Rosendo Salvado in the early nineteenth century, these constituted “a graceful and beautiful style … and a grave and serious one … a war song”, along with music to make one “very tearful”, and up-tempo songs and dance that were “happy and gay and full of life”.95 In light of this, the task of grafting appropriate melodies to archival Nyungar song lyrics and, indeed, creating new songs within a distinct Nyungar musical tradition is a significant challenge. Creative decisions regarding how to reanimate the songs about Miago were underpinned by a thorough understanding of the linguistic, historical and social context of the archival lyrics. I established a framework for composition by identifying apparent “expressive/solo” and “danceable/group” modes of Nyungar song, with “expressive/solo” songs featuring complex meter, utilising a greater number of different pitches and sometimes concluding an octave below the implied tonal centre.

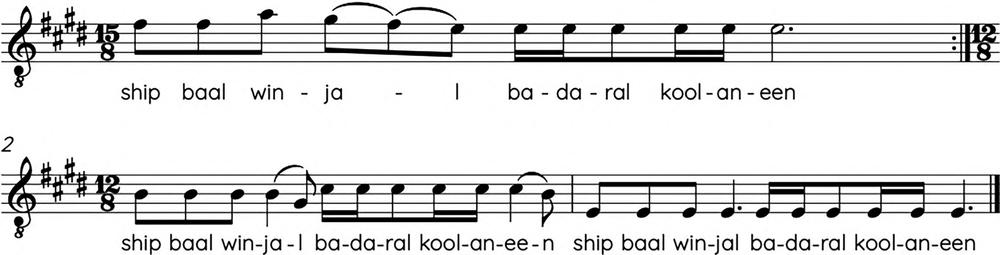

Given that the historical record describes only the songs about Miago being performed solo, it made sense to employ the conventions typical of a “solo/expressive” Nyungar song. Within that framework, and after years of immersion in the remaining archival and living traces of Nyungar song traditions, the final compositional step involved waiting for the melodies to emerge from a subconscious or dream-like state. The framework helped me remain cognisant of not “straightening-out” complex meter or “imperfect” pitch as I vocalised and recorded melodic ideas when they arrived. The “ship song” (Figure 6.2) ended up with a triplet feel akin to the ocean songs of Charlie Dabb, while the “sail song” (Figure 6.3) included the wide pitch range and complex meter typical of other “solo/expressive” Nyungar songs. Both songs concluded with an “octave drop”. Given the “loosely” diatonic nature of Nyungar song, the importance of pronunciation and timbre, I prepared an audio recording of the song and a lyric sheet with notes about meter for Gina Williams to sing. I also devised a simple harmonic progression for Gina’s guitarist, Guy Ghouse.96 The notation for the songs in Figures 6.2 and 6.3 demonstrates the use of musical conventions described in this paper for illustrative purposes.

Figure 6.2 Melody for the Nyungar “ship song” about Miago.

Figure 6.3 Melody for the Nyungar “sail song” about Miago.

Gina and Guy’s subsequent recording of the songs about Miago were uploaded as part of the City of Perth’s Kuraree online exhibition in June 2020.97 At the time of writing this chapter, fewer than 150 people had engaged with the songs as part of that exhibition. The two songs about Miago were only performed again in January 2021 when I received an impromptu invitation to sing at a Welcome to Country for artists involved in Perth Festival. Noted Nyungar singer Barry McGuire was one of the senior people in charge of the occasion. After the public part of the event had concluded, he gathered with Gina and me to discuss the processes I undertook to reanimate the songs about Miago described in this chapter. Together, Gina and I sang the songs and the three of us noted how these songs chronicle contemporary events and include English-language terms “sail” and “ship” while remaining consistent with Nyungar traditions of singing. While it is impossible to know how faithful the new melodies for these songs are to the original ones, they did not sound out of place. The songs are a small part of an online resource Roma Yibiyung Winmar and I are building to increase access to Nyungar song and language content and hopefully encourage more singing in our endangered language.98

Conclusion

This chapter provides a specific example of how archival records can form the basis for a “reanimation” of songs whose transmission through performance has been broken. It has implications in the fields of archival studies, Aboriginal history and performance practices, and music sustainability. It is significant that the reanimation of these two songs about Miago was requested by a group of senior Nyungar people, undertaken by a Nyungar researcher/composer, and performed by a Nyungar singer. Aboriginal cultural revitalisation can be fraught with tensions associated with the perceived ownership of archival material and how that material should be appropriately shared.99 In this context, it is important that the lyrics about Miago have long been in the public domain and were once widely known by both men and women, Nyungar and colonists. Although Grey provided interpretations of what these lyrics meant, re-translating them was a worthwhile activity as it shed new light on Nyungar poetics and vocabulary. In endangered language contexts, having a solid evidence-based idea of what archival lyrics mean can build confidence in the community to perform old songs again.100

The reanimated versions of the songs about Miago were informed by analysis of historical references to Nyungar musical aesthetics. Nevertheless, the creative process was equally guided by the choice to actively avoid popular music conventions and underpinned by my immersion in archival recordings and remaining singing practices among Nyungar today. Regardless of how much research one can undertake on old song styles, singing old lyrics anew – off the pages of archival texts – is ultimately a creative activity. The perceived success of such an undertaking may be alternately judged in terms of its faithful reproduction of old traditions, its reception among the community of origin today, or its ability to persist into the future.

References

AIATSIS. National Indigenous Languages Report. Canberra: AIATSIS, 2020.

Apted, Meiki Elizabeth. “Songs from the Inyjalarrku: The Use of a Non-Translatable Spirit Language in a Song Set From North-West Arnhem Land, Australia”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30, no. 1 (2010): 93–103.

Austlang. W41: NOONGAR / NYOONGAR. Canberra: AIATSIS Collection, n.d. https://collection.aiatsis.gov.au/austlang/language/w41.

Barrett, Deirdre. The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use Dreams for Creative Problem-Solving – and How You Can Too. New York: Crown, 2001.

Barwick, Linda, Bruce Birch and Nicholas Evans. “Iwaidja Jurtbirrk Songs: Bringing Language and Music Together”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2 (2007): 6–34.

Barwick, Linda, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, eds. Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond. LD&C Special Publication 18. Honolulu and Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2019.

Bates, Daisy. The Native Tribes of Western Australia, ed. by Isobel White. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1985.

Bates, Daisy. “Derelicts: The Passing of the Bibbulmun”. Western Mail, 25 December 1924.

Bates, Daisy. “Daisy Bates Papers” (1912): manuscript. MS 365, Section XI Dances, Songs. National Library of Australia, Canberra.

Bates, Daisy. “Native Shepherding: An Experience of the Perth Carnival”. Western Mail, 12 February 1910.

Bithell, Caroline and Juniper Hill, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Music Revival. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Bracknell, Clint. “Hecate: Adaptation, Education and Cultural Activism”. In Reimagining Shakespeare Education – Teaching and Learning Through Collaboration, ed Liam Selmer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.

Bracknell, Clint. “Rebuilding as Research: Noongar Song, Language and Ways of Knowing”. Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 2 (2020): 210–23.

Bracknell, Clint. “The Emotional Business of Noongar Song”. Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 2 (2020): 140–53.

Bracknell, Clint. “Connecting Indigenous Song Archives to Kin, Country and Language”. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 20, no. 2 (2019). DOI: 10.1353/cch.2019.001.

Bracknell, Clint. “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”. Yearbook for Traditional Music 49 (2017): 93–113.

Bracknell, Clint. “Maaya Waabiny (Playing with Sound): Nyungar Song Language and Spoken Language”. In Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia, eds James Wafer and Myfany Turpin. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 2017: 45–57.

Bracknell, Clint. “Natj Waalanginy (What Singing?): Nyungar Song from the South-West of Western Australia”. PhD Thesis, University of Western Australia, 2016.

Bracknell, Clint. “Say You’re a Nyungarmusicologist: Indigenous Research on Endangered Music”. Musicology Australia 37, no. 2 (2015): 199–217.

Bracknell, Clint and Casey Kickett. “Inside Out: An Indigenous Community Radio Response to Incarceration in Western Australia”. Ab-Original: Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations 1, no. 1 (2017): 81–98.

Bracknell, Clint and Kim Scott. “Ever-widening circles: consolidating and enhancing Wirlomin Noongar archival material in the community”. In Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 18 Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2019: 325–338.

Brady, John. A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Native Language of W. Australia. Rome: S. C. DE Propaganda Fide, 1845.

Brandestein, Carl Von. Sound Recordings Collected By Carl Von Brandenstein (recorded 1967–70): tape recording. VON-BRANDENSTEIN_C04, 1967–70. AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, Canberra.

Breen, Marcus. Our Place, Our Music. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1989.

Calvert, Albert. The Aborigines of Western Australia. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Company, 1894.

Castle, Robert L Van de. Our Dreaming Mind. New York: Ballentine, 1994.

Chauncy, Philip. “Notes and Anecdotes of the Aborigines of Australia”. In The Aborigines of Victoria: With Notes Relating to the Habits of the Natives of Other Parts of Australia and Tasmania Compiled from Various Sources for the Government of Victoria, ed. Robert Brough Smyth. Melbourne: Government Printer, 1878: 221–84.

Dench, Alan. “Comparative Reconstitution”. In Historical Linguistics 1995: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Manchester, August 1995, eds John Charles Smith and Delia Bentley. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1995: 57−73.

Donaldson, Tamsin. “Translating Oral Literature: Aboriginal Song Texts”. Aboriginal History 3 (1979): 62–83.

Douglas, Wilf. Sound Recordings Collected By Wilf Douglas (recorded 1965): tape recording. DOUGLAS_W01. 1965. AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, Canberra.

Douglas, Wilf. The Aboriginal languages of South-West Australia: speech forms in current use and a technical description of Njungar. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS), 1968.

Ellis, Catherine. “Creating with Traditions”. Sounds Australian 30 (1991): 14.

Gone, Joseph. “Considering Indigenous Research Methodologies: Critical Reflections by an Indigenous Knower”. Qualitative Inquiry 25, no. 1 (2018): 45–56.

Grace, Nancy. “Making Dreams into Music: Contemporary Songwriters Carry on an Age-Old Dreaming Tradition”. In Dreams – A Reader on the Religious, Cultural, and Psychological Dimensions of Dreaming, ed. Kelly Bulkeley. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001: 167–71.

Grey, George. “Papers of Sir George Grey”. Unpublished manuscript, 1838. Cape Town: National Library of South Africa.

Grey, George. “Vocabulary of the Aboriginal Language of Western Australia (Continued) (24 August to 12 October)”. Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 1839.

Grey, George. Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia: During the Years 1837, 38, and 39, Volume 1 and 2. London: T. & W. Boone, 1841.

Haebich, Anna. Dancing in Shadows: Histories of Nyungar Performance. Crawley, WA: UWA Publishing, 2018.

Haebich, Anna and Jim Morrison. “From Karaoke to Noongaroke: A Healing Combination of Past and Present”. Griffith Review 44 (2014): 1–8.

Hale, Kenneth L. and Geoffrey O’Grady, Balardung and Mirning Language Elicitation (recorded 1960): tape recording. OGRADY-HALE_01. 1960. AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, Canberra.

Hammond, Jesse. Winjan’s People: The Story of the South-West Australian Aborigines. Perth: Imperial Printing, 1933.

Hassell, Ethel and Daniel S. Davidson. “Notes on the Ethnology of the Wheelman Tribe of Southwestern Australia”. Anthropos 31 (1936): 679−711.

Hercus, Luise. Sound Recordings Collected by Luise Hercus (recorded 1965): tape recording. HERCUS_L16. 1965. AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, Canberra.

Hercus, Luise and Grace Koch. “Lone Singers: The Others Have All Gone”. In Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia, eds James Wafer and Myfany Turpin. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 2017: 103–21.

Humphries, Cliff. Aalidja Maali Yok Birrla-ngat Kor-iddny (Swan Woman Returns to Her River). Noranda: Ngardarrep Kiitj Foundation, 2020.

Knapp, Albert. Interview by Clint Bracknell, 2015, at Yardup, WA. [Digital Audio Recording].

Laves, Gerhardt. The Laves Papers: Text in Kurin (1931). Canberra: AIATSIS.

Levine, Victoria Lindsay. “Musical Revitalization Among the Choctaw”. American Music 11, no. 4 (1993): 391–411.

Livingston, Tamara. “Music Revivals: Towards a General Theory”. Ethnomusicology 43, no. 1 (1999): 66–85.

Marett, Allan. “Ghostly Voices: Some Observations on Song-Creation, Ceremony and Being in Northwest Australia”. Oceania 71 (2000): 18–29.

Millett, Janet. An Australian Parsonage, or, the Settler and the Savage in Western Australia. London: Edward Standford, 1872.

Moore, George Fletcher. A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. London: W.S. Orr and Co., 1842.

Nancarrow, Nancy. “What’s That Song About?: Interaction of Form and Meaning in Lardil Burdal Songs”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30, no. 1 (2010): 81–92.

Neuenfeldt, Karl. “The Kyana Corroboree: Cultural Production of Indigenous Ethnogenesis”. Sociological Inquiry 65, no. 1 (1995): 21–46.

Salvado, Rosendo. Memorias Históricas Sobre La Australia: Y Particularmente Acerca La Misión Benedictina de Nueva Nursia y Los Usos y Costumbres de Los Salvajes. Translated by D.F. De D. Barcelona: Imprenta de los Herederos de la V. Pla, 1853. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/8489598.

Salvado, Rosendo. The Salvado Memoirs. Ed. E.J. Storman. Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 1977.

Shellam, Tiffany. “Miago and the ‘Great Northern Men’: Indigenous Histories from In Between”. In Indigenous Mobilities: Across and Beyond the Antipodes, ed. Rachel Standfield. Acton, ACT: ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc., 2018: 185–207.

Shellam, Tiffany. Meeting the Waylo: Aboriginal Encounters in the Archipelago. Crawley, WA: UWA Publishing, 2019.

South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council. South West Native Title Settlement Agreement. n.d. https://www.noongar.org.au/about-settlement-agreement.

Stasiuk, Glen. “Weewar”. ABC TV, Australia, 2006.

Stokes, John Lort. Discoveries in Australia: With an Account of the Coasts and Rivers Explored and Surveyed During the Voyage of the Beagle in the Years 1837–38–39–40–41–42–43. London: T. & W. Boone, 1969.

Stubington, Jill. Singing the Land: The Power of Performance in Aboriginal Life. Strawberry Hills, NSW: Currency House, 2007.

Thieberger, Nicholas. Ngatju Project, Language Elicitation and Songs, WA. (recorded 1986): cassette recording. THIE-YOUNG_01. 1986. AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, Canberra.

Tindale, Norman. Site Information, Songs, Cultural Discussions From South-West WA. (recorded 1966–68): tape recording. TINDALE_N07. 1966–68. AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, Canberra.

Tomlinson, Gary. The Singing of the New World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Turpin, Myfany, Brenda Croft, Clint Bracknell and Felicity Meakins. “Aboriginal Australia’s Smash Hit That Went Viral”. Conversation, 20 March 2019. https://bit.ly/3AZrdvD.

Vogelsang, Lukas, Sena Anold, Jannik Schormann, Silja Wübbelmann and Michael Schredl. “The Continuity between Waking-Life Musical Activities and Music Dreams”. Dreaming 26, no. 2 (2016): 132–41.

Wafer, James and Myfany Turpin, eds. Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 2017.

White, Isobel. “The Birth and Death of a Ceremony”. Aboriginal History 4, no. 1 (1980): 33–42.

Wild, Stephen. “Ethnomusicology Down Under: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes”? Ethnomusicology 50, no. 2 (2006): 345–52.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native”. Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409.

Wooltorton, Sandra and Glenys Collard. Noongar Our Way. Bunbury: Noongar Language and Culture Centre, 1992.

Zemp, Hugo. Voices of the World: An Anthology of Vocal Expression. France: Le Chant du Monde, 1995.

1 Tiffany Shellam, “Miago and the ‘Great Northern Men’: Indigenous Histories from In Between”, in Indigenous Mobilities: Across and Beyond the Antipodes, ed. Rachel Standfield (Acton ACT: ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc., 2018), 185–207.

2 George Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia: During the Years 1837, 38, and 39 (London: T. & W. Boone, 1841).

3 Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native”, Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006), 387–409.

4 Tamsin Donaldson, “Translating Oral Literature: Aboriginal Song Texts”, Aboriginal History 3 (1979), 62–83; Clint Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”, Yearbook for Traditional Music 49 (2017), 93–113.

5 Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”.

6 Clint Bracknell and Kim Scott, “Ever-widening circles: Consolidating and enhancing Wirlomin Noongar archival material in the community”, in Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel (LD&C Special Publication 18. Honolulu & Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2020), http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24890/, 325–38; Karl Neuenfeldt, “The Kyana Corroboree: Cultural Production of Indigenous Ethnogenesis”, Sociological Inquiry 65, no. 1 (1995), 21–46; Anna Haebich, Dancing in Shadows: Histories of Nyungar Performance (Crawley, WA: UWA Publishing, 2018).

7 Austlang, W41: NOONGAR / NYOONGAR (Canberra, ACT: AIATSIS Collection, n.d.), https://collection.aiatsis.gov.au/austlang/language/w41; South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, Settlement Agreement (n.d.), https://www.noongar.org.au/about-settlement-agreement.

8 AIATSIS, National Indigenous Languages Report (Canberra, ACT: AIATSIS, 2020).

9 James Wafer and Myfany Turpin, eds, Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra, ACT: Pacific Linguistics, 2017).

10 Luise Hercus and Grace Koch, “Lone Singers: The Others Have All Gone”, in Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia, eds James Wafer and Myfany Turpin (Canberra, ACT: Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 103–21.

11 Clint Bracknell, “Connecting Indigenous Song Archives to Kin, Country and Language”, Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 20, no. 2 (2019), 8.

12 For example, Len Collard singing in Glen Stasiuk, Weewar (ABC TV, Australia, 2006); Clint Bracknell, “The Emotional Business of Noongar Song”, Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 2 (2020), 140–53.

13 Sandra Wooltorton and Glenys Collard, Noongar Our Way (Bunbury: Noongar Language and Culture Centre, 1992); Cliff Humphries, Aalidja Maali Yok Birrla-ngat Kor-iddny (Swan Woman Returns to Her River) (Noranda: Ngardarrep Kiitj Foundation, 2020).

14 Grey, “Papers of Sir George Grey” (unpublished manuscript, 1838), 573.

15 Gina Williams & Guy Ghouse, http://www.ginawilliams.com.au, accessed 1 August 2021.

16 Clint Bracknell, “Hecate: Adaptation, Education and Cultural Activism”, in Reimagining Shakespeare Education – Teaching and Learning Through Collaboration, ed. Liam Selmer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

17 Victoria Lindsay Levine, “Musical Revitalization Among the Choctaw”, American Music 11, no. 4 (1993), 391–411; Tamara Livingston, “Music Revivals: Towards a General Theory”, Ethnomusicology 43, no. 1 (1999), 66–85; Caroline Bithell and Juniper Hill, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Music Revival (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

18 Isobel White, “The Birth and Death of a Ceremony”, Aboriginal History 4, no. 1 (1980), 33–42.

19 Neuenfeldt, “The Kyana Corroboree”.

20 Anna Haebich and Jim Morrison, “From Karaoke to Noongaroke: A Healing Combination of Past and Present”, Griffith Review 44 (2014), 1–8.

21 Clint Bracknell and Casey Kickett, “Inside Out: An Indigenous Community Radio Response to Incarceration in Western Australia”, Ab-Original: Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations 1, no. 1 (2017), 81–98.

22 Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”.

23 Daisy Bates, “Daisy Bates Papers” MS 365, Section XI Dances, Songs (manuscript, 1912); George Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions.

24 Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”.

25 Bracknell, “The Emotional Business of Noongar Song”.

26 Haebich, Dancing in Shadows.

27 Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, eds, Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond. LD&C Special Publication 18 (Honolulu and Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press, 2019).

28 Bracknell, “The Emotional Business of Noongar Song”.

29 Clint Bracknell, “Rebuilding as Research: Noongar Song, Language and Ways of Knowing”, Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 2 (2020), 210–23.

30 Clint Bracknell, “Say You’re a Nyungarmusicologist: Indigenous Research on Endangered Music”, Musicology Australia 37, no. 2 (2015), 199–217.

31 Daisy Bates, “Derelicts: The Passing of the Bibbulmun”, The Western Mail, 25 December 1924, 55.

32 Shellam, “Miago and the ‘Great Northern Men’”, 186–87.

33 Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”.

34 Tiffany Shellam, Meeting the Waylo: Aboriginal Encounters in the Archipelago (Crawley, WA: UWA Publishing, 2019).

35 John Lort Stokes, Discoveries in Australia: With an Account of the Coasts and Rivers Explored and Surveyed During the Voyage of the Beagle in the Years 1837–38–39–40–41–42–43 (London: T. & W. Boone) 1/221–22.

36 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, 2/404.

37 Stokes, Discoveries in Australia, 1/59.

38 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, 2/544.

39 Stokes, Discoveries in Australia, 1/22.

40 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, 2/253.

41 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, 2/409–41.

42 Gary Tomlinson, The Singing of the New World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

43 Bracknell, “Rebuilding as Research”.

44 Clint Bracknell, “Maaya Waabiny (Playing with Sound): Nyungar Song Language and Spoken Language”, in Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia, eds James Wafer and Myfany Turpin (Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 45–57.

45 Clint Bracknell, “Natj Waalanginy (What Singing?): Nyungar Song from the South-West of Western Australia” (PhD thesis: University of Western Australia, 2016).

46 Meiki Elizabeth Apted, “Songs from the Inyjalarrku: The Use of a Non-Translatable Spirit Language in a Song Set From North-West Arnhem Land, Australia”, Australian Journal of Linguistics 30, no. 1 (2010); Linda Barwick, Bruce Birch and Nicholas Evans, “Iwaidja Jurtbirrk Songs: Bringing Language and Music Together”, Australian Aboriginal Studies 2 (2007); Allan Marett, “Ghostly Voices: Some Observations on Song-Creation, Ceremony and Being in Northwest Australia”, Oceania 71 (2000); Nancy Nancarrow, “What’s That Song About?: Interaction of Form and Meaning in Lardil Burdal Songs”, Australian Journal of Linguistics 30, no. 1 (2010); Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”.

47 Bates, “Daisy Bates Papers”, 36/208.

48 Bates, “Daisy Bates Papers”, 34/408.

49 Robert L. Van de Castle, Our Dreaming Mind (New York, NY: Ballentine, 1994); Deirdre Barrett, The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use Dreams for Creative Problem-Solving – and How You Can Too (New York, NY: Crown, 2001); Nancy Grace, “Making Dreams into Music: Contemporary Songwriters Carry on an Age-Old Dreaming Tradition”, in Dreams – A Reader on the Religious, Cultural, and Psychological Dimensions of Dreaming, ed. Kelly Bulkeley (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001).

50 Lukas Vogelsang, Sena Anold, Jannik Schormann, Silja Wübbelmann and Michael Schredl, “The Continuity between Waking-Life Musical Activities and Music Dreams”, Dreaming 26, no. 2 (2016): 139–40.

51 Jill Stubington, Singing the Land: The Power of Performance in Aboriginal Life (Strawberry Hills, NSW: Currency House, 2007); Bracknell, “Conceptualizing Noongar Song”.

52 Conversations with Kylie Bracknell, Barry McGuire and Annie Dabb in 2020.

53 Joseph P. Gone, “Considering Indigenous Research Methodologies: Critical Reflections by an Indigenous Knower”, Qualitative Inquiry 25, no. 1 (2018).

54 Myfany Turpin, Brenda Croft, Clint Bracknell and Felicity Meakins, “Aboriginal Australia’s Smash Hit That Went Viral”, Conversation, 20 March 2019, https://bit.ly/3AZrdvD.

55 Bracknell, “Rebuilding as Research”, 218.

56 Alan Dench, “Comparative Reconstitution”, in Historical Linguistics 1995: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Manchester, August 1995, eds John Charles Smith and Delia Bentley (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1995).

57 Bracknell, “Rebuilding as Research”.

58 Grey, “Papers of Sir George Grey”, 573.

59 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, 2/70.

60 George Grey, “Vocabulary of the Aboriginal Language of Western Australia (Continued) (24 August to 12 October)”, Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 1839, 136.

61 J. Brady, A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Native Language of W. Australia (Rome: S. C. DE Propaganda Fide, 1845), 15.

62 G.F. Moore, A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia (London: W.S. Orr and Co, 1842), 167.

63 Moore, A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia, 169.

64 Grey, “Papers of Sir George Grey”, 573.

65 Grey, “Vocabulary of the Aboriginal Language”, 144.

66 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, vol. 2, 310.

67 Kenneth L. Hale and Geoffrey O’Grady, Balardung and Mirning language elicitation (Canberra: AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, tape recording. OGRADY-HALE_01. 1960); Wilf H. Douglas, Sound Recordings Collected by Wilf Douglas (Canberra: AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive, tape recording. DOUGLAS_W01. 1965).

68 Bracknell, “Hecate: Adaptation, Education and Cultural Activism”.

69 Hugo Zemp, Voices of the World: An Anthology of Vocal Expression (France: Le Chant du Monde, 1995), 119.

70 Grey, Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery, vol. 2, 305.

71 Allan Marett, “Ghostly Voices”, 23–24.

72 Marcus Breen, Our Place, Our Music (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1989).

73 Guy Tunstill cited in Breen, Our Place, Our Music, 7.

74 Stephen Wild, “Ethnomusicology Down Under: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes?”, Ethnomusicology 50, no. 2 (2006), 350.

75 Breen, Our Place, Our Music.

76 Tunstill cited in Breen, Our Place, Our Music, 8.

77 Tunstill cited in Breen, Our Place, Our Music, 7.

78 Schultz cited in Breen, Our Place, Our Music, 7.

79 Catherine J. Ellis, “Creating with Traditions”, Sounds Australian 30 (1991), 14.

80 Bracknell, “Natj Waalanginy (What Singing?)”.

81 Hammond, Winjan’s People: The Story of the South-West Australian Aborigines; Bates, “Daisy Bates Papers”.

82 Bracknell, “The Emotional Business of Noongar Song”.

83 Von Brandestein, “Sound Recordings Collected by Carl von Brandenstein [tape recording]” (1967–70).

84 Daisy Bates, “Native Shepherding: An Experience of the Perth Carnival”, Western Mail, 12 February 1910, 44.

85 Bates, “Native Shepherding”, 44.

86 Janet Millett, An Australian Parsonage, or, the Settler and the Savage in Western Australia (London: Edward Standford, 1872), 85.

87 Hammond, Winjan’s People, 52.

88 Bracknell, “Natj Waalanginy (What Singing?)”.

89 Rosendo Salvado, Memorias Historicas Sobre La Australia : Y Particularmente Acerca La Mision Benedictina de Nueva Nursia y Los Usos y Costumbres de Los Salvajes., trans. D.F. De D. (Barcelona: Imprenta de los Herederos de la V. Pla, 1853), https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/8489598; Philip Chauncy, “Notes and Anecdotes of the Aborigines of Australia”, in The Aborigines of Victoria: With Notes Relating to the Habits of the Natives of Other Parts of Australia and Tasmania Compiled from Various Sources for the Government of Victoria, ed. Robert Brough Smyth (Melbourne: Government Printer, 1878), 221–84; Albert Calvert, The Aborigines of Western Australia (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Company, 1894).

90 Philip Chauncy, “Notes and Anecdotes of the Aborigines of Australia”, 266.

91 Von Brandestein, “Sound Recordings Collected by Carl von Brandenstein [tape recording]”.

92 Bates, “Daisy Bates Papers”, 34/34.

93 Daisy Bates, The Native Tribes of Western Australia, ed. Isobel White (Canberra, ACT: National Library of Australia, 1985), 335.

94 Breen, Our Place, Our Music.

95 Rosendo Salvado, The Salvado Memoirs, ed. E.J. Storman (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 1977), 133.

96 Given the efforts described above to recreate the sound of these songs as faithfully as possible, the inclusion of guitar accompaniment may be surprising. However, Ghouse has been a constant part of Williams’ musical activity since 2010 when she began performing in Nyungar language. Consequently, the City of Perth’s Nyungar Elders Advisory Group and Williams herself felt most comfortable that the song be recorded in the vocal-and-guitar duo format.

97 “The Heart of Perth, Kuraree”, Perth City, https://kuraree.heritageperth.com.au, accessed 1 August 2021.

98 “Mayakeniny: Restoring on-Country Performance”, https://www.mayakeniny.com, accessed 1 August 2021.

99 Bracknell, “Connecting Indigenous Song Archives”.

100 Bracknell, “Rebuilding as Research”.