7

Authenticity and illusion: Performing Māori and Pākehā in the early twentieth century

Authenticity and illusion

Download chapter 7 (PDF 2.6Mb)

Introduction

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, before radio and “the talkies” established themselves as forms of popular entertainment, vaudeville, the music hall and variety stage served up a huge array of performance events. Anything from acrobats and jugglers, tableaux of famous artworks, musical and dramatic segments, to dancing dogs and performing monkeys could appear on the same playbill. Of especial interest for audiences in Europe and North America were novelty acts that blurred the lines between entertainment and racial taxonomy, between the authentic and the illusion. Between 1910 and 1929 two New Zealand women trod the boards of music halls and appeared on the silent silver screen performing representations of New Zealand to audiences in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres. By adapting and presenting performances that represented and stood for Māori (Indigenous New Zealander) and Pākehā (non-Māori), these women – Princess Iwa and Bathie Stuart – contributed to notions of Māori and Pākehā as separate but related ethnographic entities. This essay shines a light on the archival offerings that uncover moments in their professional careers while also endeavouring to understand how their songs, dances, costumes and embodied expression both created and reflected impressions of a nation/dominion, race and gender. Moreover, by delving into the world of historical performance via photographs, newspaper items, playbills, films and scrapbooks, the evolution of embodied cultural hybridities emerges.

My interest in the archives of these two women and their careers in the performing arts stems from my curiosity on uncovering developments in corporeal expressions of culture both in New Zealand and internationally, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Specifically, I wondered how songs and dances, performed by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples on stage and, later, on film, transcended and traversed “traditional” or non-commercial settings and purpose to become shared histories of cultural identities and performing arts. In examining past iterations of representations of race and gender via music and movement, new understandings of cultures emerge, oftentimes disrupting accepted notions of tradition and authenticity, as Tavia Nyong’o states, “hybridity unsettles collective and corporeal memory”.1

Though all interpretations of historical events rely on scrutiny of primary and secondary sources, performance history demands that the historian imagines movement and sound in the empty spaces on stages, between the lines of sheet music, and behind the static images of facial and bodily expression fixed in photographs. My research aligns with Jane R. Goodall’s observation that “performance is not only or even primarily a verbal medium … communication occurs as much through imagery, movement and expression, all of which leave only partial and secondary traces in the archive”.2 Pertinent to this research, the connections between the performances of a 100 years ago by these two women and the narrative I have constructed of their lives and careers were enhanced by my own personal and embodied history as a dancer and performer. When reading a newspaper review of a performance or analysing a photograph taken on stage, grounded with my own somatic knowledge, I could intuit the flow or force of a movement or gesture. My own experience mirrors that of choreographer and researcher Martin Nachbar when he states that the “body that enters the archive in order to find documents of dance, is itself already a carrier of movement knowledge”.3 Seeing beyond a stationary image, I could sense the excitement or nervousness of these women when standing on stage in front of an audience, feeling the power of communicating through body, eyes and voice as I conjured felt memories of my own past performances.

I also have consulted closely with Iwa’s grand-niece, Christchurch-based singer Angela Skerrett Tainui, the two of us sharing our findings on Princess Iwa as we each came upon more material on her life and career.4 The story of Iwa’s career in the UK had faded from memory among some whanau in New Zealand as her contemporaries passed on and with no known surviving recordings to keep her voice present, but Angela has worked tirelessly over the past decade to reintroduce Iwa to them via the surviving archival sources and seeking oral histories from iwi. An audio documentary that she produced, Whakamarantanga o Iwa, is held at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.5

Alongside the absence of a recorded voice, dance especially has often been referred to as ephemeral, the “quintessential artform of the immediate”, or the “vanishing present”.6 From notation forms being varied and not widely adopted, to the variations in reconstruction/restaging success from photographs, choreographic notes and films, fixing or preserving dance is problematic. Yet, in many ways, archival source material of performers and performances resurrects long forgotten but nonetheless transcendent moments of beautiful musical notes in the air or expressive, evocative gestures of the limbs. Though the extant documents are not the performance itself, they can open the door to the past. Imagination, coupled with a deeply held belief in the centrality of the performing arts in the formation of societies and cultures throughout history, enables the fragile material in folders to breathe.

The archives, if given due respect and attention, can reanimate performance. My research has uncovered musical scores long forgotten and photographs buried in boxes seldom opened. The anticipation of hearing a piece of music not performed in 100 years or viewing a hand-made costume last worn on stages in early twentieth-century London is beyond words. This chapter is an attempt to fill in the gaps of the stories left by those fragments of performance by two remarkable women.

Princess Iwa: The “Maori Nightingale”

The review in the 15 October 1911 edition of Lloyds Weekly News enthusiastically stated that “Iwa, the ‘Maori Nightingale’ is the latest musical star at the Palace Theatre”.7 Headlining an act dubbed the “Dusky Dancers”, Princess Iwa appeared as the soloist with a group of young Māori women, the “poi girls”. The career of Iwa and her journey from the southernmost point of New Zealand to stages in the United Kingdom reveals the emergent expression of identity of New Zealand as a place where Māori and Pākehā collaborated and coexisted. Princess Iwa first arrived in the UK in 1911 as the soloist in Maggie Papakura’s (née Thom) group of Māori performers and carvers. Papakura herself was famous as a tourist guide at the popular hot pools, springs and geysers in Rotorua, in the North Island of New Zealand. In response to a request from financial backers to take a group of entertainers plus a replica whare (house) to Australia and beyond, Papakura directed the group, acutely aware of the lure for Europeans of Māori performing their songs and dances in a “native” environment. She also believed that overseas touring benefited Māori who would come back to New Zealand and impart “their ideas to those who remained behind”.8 And so, in late 1909 Papakura and her assembled group of “Maori Entertainers” set sail for Sydney. In 1910, performing in Sydney and Melbourne with Papakura’s group, Iwa was described by the Sydney Sunday Sun as “the star attraction of the Maori village” possessing “a contralto voice of great richness and power” while another Sydney newspaper noted the “fine vocalisation of Iwa, who is known in New Zealand as the ‘Glorious Maori contralto’”.9

Princess Iwa was born Evaline Skerrett (Ngāi Tahu) in 1890 on Stewart Island. She was raised in Bluff, Southland, where she also first started singing. In 1909, Iwa placed second in the Sacred Solo-Contralto category of the Dunedin musical and elocution competitions. The Australian judge cited her as a “contralto with a future” and soon after she came to the attention of Papakura.10 The young singer proved an ideal symbol of successful Māori assimilation and her association with Papakura provided the springboard for her notoriety in the UK. Indeed, much of the archival material found for my research on Iwa is contained within Papakura’s papers held at the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford.

The blending of Māori themes, setting and performers with European musical forms and compositional styles constituted new cultural expressions of and for New Zealand, especially as European cultural expression became more prominent within New Zealand society from the end of the nineteenth century as the processes of colonisation solidified and strengthened. Consequently, opportunities for cross-cultural performance events increased for both Māori and Pākehā. Expressions of popular culture in the early twentieth century, particularly songs, stage acts and films also provided platforms for the creation of aesthetic hybrids in the performing arts.

One such instigator of this form of music was composer Alfred Hill.11 Many of Hill’s compositions, championed by some Māori performers including Papakura and Princess Iwa, reflected his quest to rediscover Māori music, alter it and introduce it to a wider audience. Australian-born Hill studied composition at the Leipzig Conservatory of Music, Germany, in the 1880s where his ear for European music was attuned. Hill’s 1896 cantata Hinemoa portrayed, via Western musical forms scored for chorus and orchestra, the Te Awara story of mismatched lovers and the triumph of true love. Indeed, following Hinemoa’s premiere in Wellington, Hill was praised in the Evening Post for his ability to adapt and manipulate “Maori song” with his “masterly” handling of the Hinemoa legend.12 However, Sarah Shieff has described Hill’s compositions as a “veneer” of Māori laid over European forms of music, keeping the “Western forms intact”.13 His 1917 collection of songs published as Waiata Maori (Waiata meaning song in te reo Māori, the Māori language) have been referred to as “Europeanized Maori songs” and offered advice for singers on pronunciation of te reo Māori.14 Here Hill suggested that “the pronunciation is practically the same as Italian”, thus emphasising the romantic, foreign and “high” cultural element of this music.15 These European interpretations and imaginings of Māori created a nostalgia for Māori culture, while also assuming ownership of Māori cultural expressions.

The idea that with colonisation the “weaker” of the races would be gradually erased clashed with the inclusion of Māori themes and settings in music and drama. This theory, known as fatal impact, along with the process of assimilation that was imposed on Māori from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, contributed to both a continuing erasure of Māori cultural expressions, including language and spirituality, and a longing to preserve aspects of culture. Māori were kept “alive” in the public’s imagination through storytelling, drama and music. The explanation offered by Judith Williamson describes this process of cultural colonisation: “what is taken away in reality, then is re-presented in image and ideology so that it stands for itself after it has actually ceased to exist”.16 Hill’s compositions clearly illustrate this transformation of Māori music into forms of popular cultural expression in an emerging bicultural society, as do Princess Iwa’s and Bathie Stuart’s acts.

Hill’s most popular song, Waiata Poi, illustrates an aspect of the “dying Māori” ideology via his relationship with well-known painter Charles Goldie. Goldie, famous for his portraits of Māori, hoped to capture the essence of the “disappearing” race in his work, with titles of his portraits such as The Last of the Tohungas and A Noble Relic of a Noble Race. As Hill explained, Waiata Poi came to him as he sat in Goldie’s studio in the evenings listening to the “old people sing half-remembered chants of the olden days”.17 The early career success of Princess Iwa relied heavily on the performances of Hill’s songs, in particular Waiata Poi. While in Australia and later the UK, Iwa performed Hill’s Waiata Poi, among other works.

In an interview with the Norwood News Iwa promoted Hill’s talents, expressing “loud praise” for his works, which the reporter concluded as Iwa stating that Hill was the composer “whom English and Maoris alike look upon as their representative musician”.18 A newspaper review appearing five years after she first arrived in the UK confirms that Waiata Poi continued to be an important item in her solo repertoire:

In the Maori song “Waiata Poi” which has been admirably arranged by Alfred Hill, Princess Iwa sang the exhilarating weird melody of her native land – which in some of its strains is reminiscent of Magyar – with fine flair and with just that distinctive suggestion of the bizarre which renders it so stimulating to the imagination.19

When she arrived in London in 1911 for the Festival of Empire with Papakura’s troupe, Iwa immediately stood out. Personifying cultural hybridity, at once an Indigenous, “authentic” performer and European operatic songstress, the “Maori Nightingale” caught the attention of a public fascinated by her mixed-race heritage and pure, sweet voice. Under Papakura’s direction and by association with Waiata Poi in particular, Iwa appeared as a performer who crossed cultural lines, appealing to European audiences with her renditions of Pākehā interpretations of Māori music. A showbill in Nottingham listed Iwa as “a British subject of Maori nationality who will sing a typical Maori song in the picturesque costume of her country”.20 It is clear that the Māori soloist resisted categorisation with her embodied difference. Her costume of traditional piupiu (dyed flax reed) skirt and feathered cloaks juxtaposed with her voice, which was that of a European classical singer.21

Following their appearances at the Festival of Empire and the Coronation Festival in London in the summer, Iwa and the “poi girls” were offered a contract to perform at the Palace Theatre in the autumn of 1911. The promotional photograph of the Palace season shows Iwa standing on her own wearing her kahu kiwi (cloak of kiwi feathers) with a tāniko (geometric-patterned stitched border) draped across her chest. A large hei tiki (greenstone pendant) hangs around her neck. She stands on a korowai whakahekeheke (a woven cloak decorated with tassels and feathers). The accompanying “poi girls”, posed in the seated “canoe poi” configuration, wear an assortment of korowai (tasselled cloaks) and piupiu. Aside from their “exotic” dress, these Māori women offered “dances … weird yet fascinating and totally different from anything seen in London”.22

The Māori women drew large crowds to the Palace and their act was favourably reviewed. A caption in a London newspaper described how the “songs and dances by the troupe of Maoris, headed by the sweet-voiced Iwa, have proved so popular at the Palace Theatre that their engagement has been indefinitely prolonged”.23 The Times singled out Iwa as the “sweet singer of the Maoris”, adding that “it is refreshing to come across something rather out of the common run”, while the Croyden Times called Iwa “the beautiful and extraordinary powerful contralto”.24 All these accounts highlight the contradictory nature of the song and dances that relied upon the embodied combination of “primitive” and “skilled”. In the public’s mind, Iwa’s proficiency as a classical singer contrasted with her costumes and barefoot performances.

Iwa’s early musical influence came from both Māori and Pākehā styles of singing. By the 1870s, Ngāi Tahu, Iwa’s tribal affiliation in Bluff, had been “regarded as the most ‘European’ of the Māori tribes” due to the large influx of sealers and whalers and interracial marriage with these predominantly American and European arrivals.25 Consequently, the ethnomusicologist Mervyn McLean describes how “Maori became bimusical in both the traditional Maori and the European systems” over the years of contact and colonisation.26 In addition to the songs of whalers, merchants, soldiers and boat builders, the introduction of Christianity and hymn singing all added to the mix of songs among Māori and interracial communities. With this hybridity came new forms of musical expressions, blending melodies, song structure, time signatures and tonality. Iwa’s choice of songs, her singing style, and her ability to use both English and te reo Māori in her songs reflect these developments.

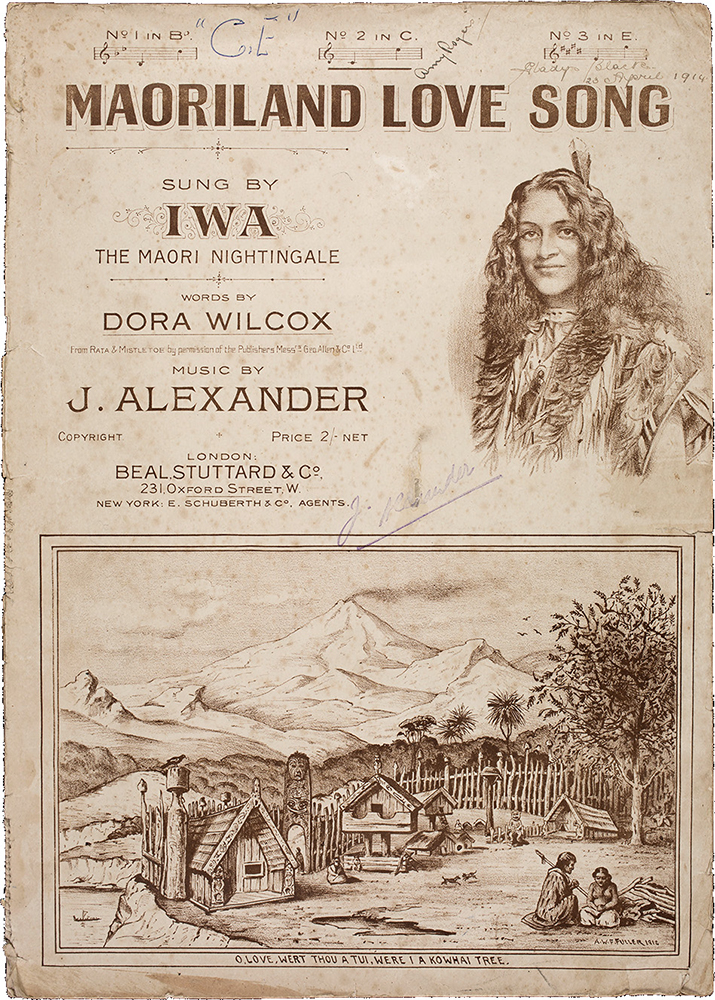

Figure 7.1 “Maoriland Love Song”, words by Dora Wilcox; music by J. Alexander. London: Beal, Stuttard & Co., 1912. (A-015-001, Fuller, Alfred Walter Francis, 1882–1961. Used with permission of Alexander Turnbull Library/Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, Wellington).

Unlike most of the group in London, Iwa did not return to New Zealand in 1912. During the Palace season, Iwa received “cheering words” from respected operatic England-based singing teachers and based on their encouragement she decided to “stay and study”.27 Settling in the UK, she developed her performing career as a solo artist and appeared on the variety stage of music halls throughout the country for the next decade. Her repertoire at this time perhaps reflected the influence of her vocal coaches, especially the songs she incorporated into her act that required an operatically trained voice, including “My Treasure”, “Nearer My God to Thee” and “I Know a Lovely Garden”. Glowing notices, articles and reviews from Birmingham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Norwich, Plymouth, Manchester, Liverpool and Newcastle appear throughout these years. The sentiment from the review of her performance with the Ayr Burgh Choir concert in Scotland during this time is typical:

Princess Iwa’s appearance on the platform was eagerly awaited by the audience, and she must have been delighted with the warmth of the reception accorded on the grounds of personality alone. She has a voice of great range and power, pure tone, flexibility, and expressional quality, which stamps her as a front rank artist, and her career will be watched by all who had the pleasure of listening to her renderings both of our ballads and her own home gems of song. The effect of her singing was heightened by her appearance in native dress and with bare feet. She will not be soon forgotten.28

In the years 1915–18 Iwa performed in numerous benefit concerts in aid of the war effort, sharing the bill with members of the popular Carl Rosa Opera Company. In 1921 the Glasgow Bulletin published a photograph of a very stylish Iwa beside her equally sartorially smart husband, tenor Wilson Thornton. Under the headline “Glasgow is Their Choice”, the newspaper informed that “Mr. Wilsun [sic] Thornton and his wife (The Maori Princess Iwa) have severed their connection with the Carl Rosa Opera Company. They intend to settle in Glasgow to teach singing”.29 The Glasgow Evening News also publicised the couple’s move: “Mr. Thornton, it may be recalled, is married to Princess Iwa, a Maori lady in whose bloodline is a Royal strain. She was associated with her husband in opera, and will assist him in his latest enterprise.”30 While conducting this archival research, I travelled to Glasgow and stood outside their home. While Iwa never returned to the land of her birth, having died in London in 1947, I feel that I have helped to bring her story home.

Bathie Stuart: “The Girl who Sings the Maori Songs”

While Iwa carved out a niche for herself in the UK as the “Maori Nightingale”, a Pākehā woman in New Zealand fashioned a career as a wahine Māori (female) performing songs in te reo Māori, incorporating movements and gestures that mirrored a Māori persona. Billed as “The Girl who Sings the Maori Songs”, Bathia (Bathie) Stuart created a racialised caricature both on stage and screen that imitated Māori cultural practice. Contrasting with Princess Iwa, a Māori woman who offered a British-ised version of Māori, Stuart’s act relied on her audience’s awareness that she was a Pākehā who could conjure “Māori-ness” through song, dance and costume. Reflecting contemporary blackface/ethnic impersonations such as Al Jolson’s in the film The Jazz Singer (1927), or Toots Paka and Gilda Gray who performed “Hawaiian” dances on mainland United States in the first decades of the twentieth century, audiences knew that Bathie was not Māori. Nonetheless, her unique portrayal of wahine Māori was celebrated and well received.31 Indeed, so convincing was Stuart’s performance that an anonymous reviewer, almost certainly Pākehā, commented Stuart “is a Maori maid in all but colour”. The story that emerges from the archives of Stuart’s life and career highlights the concepts of the “malleability of ethnicity” and “racial masquerade” so prevalent in early twentieth-century popular entertainment.32

Bathie Stuart was born in Hastings on the North Island’s east coast in 1893 to parents of Scottish descent. She began her performing career at age 14 when she became a member of Pollard’s Juvenile Opera Company, touring operettas on the vaudeville circuit throughout New Zealand and Australia.33 Having survived being stricken by the 1918 Spanish flu (her husband, unfortunately, did not), by her mid-twenties Stuart developed her own music and comedy act. In a 1984 interview held in her archives, Stuart describes how she believed that she was always “unusual” because she had been so “interested in the Maori lore and could sing Maori songs”. She claimed that “no other Pakeha did that in those days. I was the only one”.34 Like Alfred Hill, it seems that Stuart was drawn to Māori songs and felt compelled to promulgate and popularise Māori cultural expression. Unlike Princess Iwa, whose repertoire consisted of concert and parlour songs reflective of her operatic training, Stuart’s songs and dances fit into a comedic, entertaining style.

There is no doubting that opportunities availed themselves to Stuart because she was a white woman. In the early 1920s the Māori population resided primarily in rural and segregated areas of the country. Tourist areas such as Rotorua provided spaces where Pākehā and overseas guests could attend performances of Māori performing arts, such as haka, poi and waiata. These performances allowed for both close proximity to Māori and Māori culture and defined distance from Europeans and everyday life. Therefore, that Stuart was able to create images and representation of Māori for her Pākehā audiences is understandable given the absence of Māori from Pākehā daily life. As historian James Belich has explained, Māori at this time were “isolated from and marginal to, the Pakeha socio-economy” and lived predominantly in the rural environment.35 The 1923 Census recorded the uneven population of New Zealand, with 1.2 million Europeans/Pākehā compared to roughly 53,000 Māori.36 Hence, it is not surprising that Māori culture was transplanted and translated onto stage and screen in the early twentieth century in an effort to retain a sense of New Zealand’s unique history, minus reminders of the colonial atrocities, disputes over land acquisition, and erasure of spiritual and cultural practices.

There were other vehicles for Māori storytelling by Māori, and one area where the ideologies of some Māori and Pākehā coexisted in this period was within the sphere of the performing arts. However, owing to the constrictions of assimilation, these tended to reflect the growth in hybrid cultural expression. For instance, a decade before Stuart created her vaudeville act, the Māori Opera Company presented a staged version of the Hinemoa story as a three-act opera with a small orchestra and a cast of 30 Māori performers. The music, composed by Englishman Percy Flynn, aimed to showcase Māori culture via European musical settings. This setting of a well-known Māori story in a Western performance form aligned with the views of some Māori, especially men who were educated in Pākehā-led institutions or were associated with the Christian church. Reverend Frederick Bennett, the instigator of the Māori Opera Company, strongly advocated for assimilation. As a man with mixed Māori-Irish ancestry and an ordained Anglican minister, Bennett worked hard to cultivate European sensibilities and practices among Māori. The Poverty Bay Herald reported in 1915 that Bennett, as “proprietor”, appeared on stage and explained “how the production of the play has been entered upon, so as to create an interest in the Maori mind for the higher art”.37 Therefore, Māori and Māori culture had a presence within the realm of popular entertainment in the early twentieth century.

This metamorphosis from traditional and ritual expression by Māori to entertainment by both Māori and Pākehā cast a shadow over cultural production and representation, and it was out of this shadow that Stuart as a “Pakeha Maori” emerged.38 In 1926 Stuart created a sensation with her act “Bathie Stuart and her Musical Maids”. During their four-week run at the Majestic, a vaudeville cinema theatre managed by Henry Hayward in Auckland, Stuart successfully portrayed a Māori woman who, although lacking tribal affiliation or distinct connections to a specific place in New Zealand, entertained on stage. Following this sold-out season, which a reviewer in the Auckland Star described as the “instantaneous success of Miss Bathie Stuart and her accompanying native girls”, Stuart toured the next incarnation of this group, “Bathie Stuart and her Maori Maids”, throughout the Hayward circuit.39

Stuart claimed that women from Rotorua taught her the “songs, poi, dances and haka” for her stage show with the “Maori Maids” and that Apirana Ngata, a respected statesman of Māoridom, taught her “many of the Maori songs”.40 The Maids’ act consisted of the songs “Hoki Tonu Mai” and “Pokarekare”, sung in te reo Māori, in addition to poi dances and haka.41 Surrounding herself with her “Maori Maids” and performing Māori, through song, dance and dress, Stuart simultaneously highlighted her own non-Māori identity while also celebrating Māori culture. Drawing attention to Māori culture and customs through the phenomenological engagement between audiences and performers reflects a complex cultural exchange between Māori and Pākehā at this time. Stuart assumed both a Māori and non-Māori identity in the moment of performance.

The acceptance and success of Stuart’s act mirrors Alison Kibler’s description of the “racial masquerade” that was employed by American entertainers in the late nineteenth century. Kibler states that “racial masquerades emboldened some white comediennes by setting them apart from svelte, perky chorus girls”.42 Stuart certainly used her comedic flair and short stature to her advantage. In the 1925 Australian “comedy drama in six reels” The Adventures of Algy, Stuart portrayed “Kiwi McGill”, a young woman living with her father on a New Zealand farm, whose future is uncertain. Unlike the archival evidence of Princess Iwa’s career, found primarily in photographs and newspaper accounts, we are fortunate to be able to view Bathie Stuart in action, as it were.

Viewing the extant copy of The Adventures of Algy offers the opportunity to experience Stuart’s performance style and movement vocabulary, which is not as readily available when interpreting a static image. Performed and filmed almost 100 years ago, Stuart’s dancing in this moving picture draws the viewer towards a deeper comprehension of corporeal expression of past bodies. Unaccompanied by music (this is a silent film), the dance sequences focus attention on the temporal expressions of culture in movement and clothing, via breathing, working, entertaining, bodies. And we witness the energy of the movement: mistakes, reactions, intent.

When the film’s Australian director, Beaumont Smith, arrived in New Zealand in early 1925 to conduct a series of screen tests throughout the country seeking Algy’s leading lady, a newspaper reported that Stuart, “known throughout the Dominion as ‘The Girl who Sings the Maori Songs’ is the young New Zealand heroine in support of Claude Dampier [the lead male actor]”.43 The familiar show-within-a-film setup of 1920s motion pictures, seen in movies such as Golddiggers of Broadway, is echoed here in this silent film, as Kiwi, a hard-working but unlucky dancer, is discovered by a theatrical producer performing her “Maori” dances with her friends in Rotorua. Troubled by her father’s financial hardships, Kiwi visits her Māori friend Mary for advice. Kiwi arrives at the local Māori village dressed in her feathered cloak, when Mary suggests a temporary solution. Mary’s caption says, “Dance for us, Kiwi, and forget your troubles”. Seeing Kiwi in this environment, surrounded by Māori, viewers are meant to understand that Māori accept Kiwi and her interpretation of Māori haka. Moreover, she is encouraged to dance as wahine Māori by Mary, who is wahine Māori. Kiwi acts on Mary’s advice and stands, her cloak falling to the ground, revealing her piupiu and woven top draped over one shoulder. She dances, thrusting her hands and hips to the side, circling her wrists and placing one hand near to her ear with a shimmering movement, movements meant to resemble what wahine might perform in a haka or poi dance. As Kiwi dances, a group of European men and women, led by a Māori guide, watches with interest. This is when the Australian theatrical producer discovers the “distinct novelty” for his new revue. Forthwith, Kiwi heads to Australia to headline a new show in Sydney.44

The large-scale stage production number in Algy, filmed at Sydney’s Palace Theatre, featured Kiwi dancing in front of a chorus of 20 dancing women, all attired in grass skirts, cropped tops and short dark wigs. Their choreography includes typical stage movements of the day – unison lines of turns, kicks and promenades – with the addition of “exotic” gestures, such as hip circles and hand waving, invoking Māori wiriwiri (hand shimmer) or Hawaiian hula hand gestures. This exaggerated “mélange of movements, at times conjuring various ethnicities and time periods” culminates with Kiwi downstage swaying in a crouched position with her raised hand clutching a club.45 Her triumphant final stance signalled both the power of the imagined “traditional” movements and the female body. Thus, in The Adventures of Algy, Bathie Stuart as Kiwi McGill simultaneously represented both an idealised wahine Māori and a Pākehā who had colonised Indigenous expression through her movements and costume.

“How much Maori can you do?”

The illusionary nature of Stuart as an Indigenous New Zealander led to a second career promoting New Zealand to Americans. Having settled in the United States in the late 1920s, she “pioneered adventure/travel film lectures across America”, publicising New Zealand as a tourist destination.46 The events leading up to Stuart’s career on the lecture circuit in the United States parallels the story of how Kiwi McGill was discovered by the Australian producer in The Adventures of Algy.47 In the 1984 interview Stuart explained that after lunching at a women’s club in Los Angeles, the host introduced her as “our guest from faraway New Zealand who will speak to us in her native tongue”. Explaining that English was her first language, Stuart nonetheless performed her “Maori” dance. Upon witnessing this performance, a booking agent present at the luncheon asked Stuart if she realised what a “remarkable novelty” she possessed, asking, “How much Maori can you do?”48 From then on her presentations in the United States consisted of showing a tourism film on New Zealand, a short lecture on customs and landmarks, and a performance of her interpretations of waiata, haka and poi. Her publicity flyers promised that Stuart was “as proficient in the rendition of their [Māori] ceremonials and sweet haunting melodies as the natives themselves”.49 These illustrated lectures relied on her ability to perform waiata and haka, as she emphasised in a letter to the New Zealand Government Publicity Department in a solicitation for their support: “I am sure that an ordinary lecture on New Zealand could not arouse the enthusiasm that is achieved by a talk embellished with the poetry and rhythmic dances of our ‘First New Zealanders’”.50 It is clear that although Stuart never attempted to pass as Māori, her careers in show business and tourism nonetheless depended on her convincing portrayal of Māori in song and dance.

Figure 7.2 “The only white woman interpreting the unusual folk lore of the Maori people”, Miss Bathie Stuart. [TO1 118 5/3 1 R21484799] Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, used with permission.

Conclusion

So what can the microhistories from the archives of these two New Zealand performers reveal about larger phenomena in music, dance and entertainment? The careers of both women slotted into expressions of early twentieth-century popular culture of controlled exoticism, signified by the female form encased in somewhat revealing clothing, often barefoot, performing unfamiliar (to a non-Indigenous audience) rituals, songs and dances on stage or film. Princess Iwa, with her charming, melodic voice, “native” clothing and the regal designation of “Princess” enchanted her audiences by combining songs sung with expertise with the accoutrements of “Other”. A Māori woman by birth, the incongruity of an operatic voice coupled with Indigenous clothing only enhanced her popularity in the public’s eye.

Bathie Stuart, by enacting Māori through song and dance, while being recognised for her ability as a Pākehā to “interpret” Indigenous culture, transported Māori songs and movement into the realm of popular light entertainment. Importantly, Stuart projected “New Zealand-ness” to audiences who were becoming increasingly aware of their own identities – politically, socially, culturally – as separate from the “home country” of Great Britain. Since 1907 when New Zealand achieved Dominion status from the UK, allowing for self-government at home rather than strict adherence to the rule of the British Crown from a distance, New Zealand visual artists, writers, composers and performing artists sought to create identifications of nationhood via their work.

Significantly, throughout their performing careers, it was essential for both women that they highlighted their origins as New Zealanders; the idea that “authenticity equals ancestry” seems relevant here.51 Both conjured notions of New Zealand through their corporeal expression. Their uniqueness was also good for business, as reflected in a comment made by the manager of the Palace Theatre in London. Predicting that Princess Iwa’s future success relied on her singing “in Maori”, the manager emphasised it would be a “fatal mistake” if she sang “the usual Pakeha drawing room song”.52 For both women it was through performances of song and dance that their identities as New Zealanders became known. Their different versions of a “New Zealand woman” – Princess Iwa an assimilated Māori, Bathie Stuart a Pākehā interpreting and also celebrating Māori culture – represented modern twentieth-century New Zealand society.

Researching the extant archival material of these two women, it becomes clear that music and choreographed movements can reinforce attachments to place and create notions of race. Princess Iwa’s performances, in particular her renditions in te reo Māori of Alfred Hill’s Waiata Poi and Hine e Hine by Te Rangi Pai, substantiated her ancestry, even though her perfectly pitched soprano voice belied her Indigenous heritage in the public’s perception of what an Indigenous voice should sound like. The movements of haka and poi, so intrinsically linked to Māori, confirmed Stuart’s authenticity as a New Zealander, albeit a Pākehā performing interpretations of Māori culture.

The conflicts of comprehension that arose as I absorbed the material in these archives illuminated the work that historians of performing arts undertake. The archives revealed strongly held beliefs on race, societal hierarchies and acceptability, especially within the realm of popular culture in the early twentieth century. As I have not had access to accounts of either performer in te reo Māori, it is difficult to know how contemporary Māori viewed their “acts”. By the early twentieth century te reo Māori was largely confined to Māori communities and all but banned in schools and in public. Though there were newspapers written in te reo at the time, I could find no reference to either performer’s acts in these archives.

That sounds and gestures could stand for national identity and racial heritage was an important consideration for both women, reflecting a common phenomenon in the performing arts of the era. By the early twentieth century, cultural hybridity manifested in numerous displays of popular culture, reinforcing the notion that “all cultures are involved in one another; none is single and pure, all are hybrid”.53 Above all else, both Princess Iwa and Bathie Stuart relied on the incongruous but modern nature of their very hybrid beings. As both Māori and Pākehā, their songs and dances shaped expressions and representations of New Zealand and laid the groundwork for future innovations in the evolving and changing nature of bicultural and transcultural performing arts, particularly in later forms of musical and choreographic expression.

References

“A Contralto with a Future”. Evening Post, 1 October 1909, 7. https://bit.ly/3Pb66ul.

“Alfred Hill Obituary”. New Zealand Listener, 18 November 1960, 34.

Bathie Stuart. Ref TO 1 118 5/3 part 1. Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

Bathie Stuart Papers. MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Folder 3. New Zealand Film Archive/ Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiāhua, Wellington.

Belich, James. Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000. Auckland: Penguin Books (NZ) Limited, 2001.

Brown, Michael. “Hoki Mai Ra”. National Library of New Zealand. 11 August 2014. https://natlib.govt.nz/blog/posts/hoki-mai-ra.

Desmond, Jane. Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Diamond, Paul. Makereti: Taking Māori to the World. Auckland: Random House, 2007.

“Dunedin Competitions”. Otago Daily Times, 1 October 1909, 6. https://bit.ly/3yPuPiz.

Franco, Mark. “Introduction: The Power of Recall in a Post-Ephemeral Era”. In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment, ed. by Mark Franco. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018: 1–19.

Goodall, Jane R. Performance and Evolution in the Age of Darwin. London: Routledge, 2002.

Hill, Alfred. Waiata Maori: Maori Songs Collected and Arranged by Alfred Hill. Dunedin: John McIndoe, 1917.

“‘Hinemoa’ and Other Original Works”. Evening Post, 19 November 1896, 5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP18961119.2.52.

Kibler, Alison. Rank Ladies: Gender and Cultural Hierarchy in American Vaudeville. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Lindholm, Charles. Culture and Authenticity. Malden: Blackwell, 2008.

Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers (1901–10), cuttings and ephemera. Box VII. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs etc. Box X. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

“Maori Opera Company: Hinemoa at the Opera House”. Poverty Bay Herald, 14 October 1915, 7. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/PBH19151014.2.49.

McLean, Mervyn. Maori Music. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996.

“Miss Bathie Stuart and her Maori Maids”. Auckland Star, 8 May 1926, 18. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19260508.2.156.5.

Nachbar, Martin. “Tracing Sense/Reading Sensation: An Essay on Imprints and Other Matters”. In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment, ed. Mark Franco. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018: 19–33.

New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1923, https://bit.ly/3x4dxwN, accessed 29 November 2012.

Nyong’o, Tavia. The Amalgamation Waltz: Race, Performance, and the Ruses of Memory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

“Return of the Maoris: Causes of the Failure”. Auckland Star, 10 January 1912, 8. https://bit.ly/3RgNpHE.

Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Random House, 1994.

Schultz, Marianne. Performing Indigenous Culture on Stage and Screen: A Harmony of Frenzy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Shieff, Sarah. “Magpies: Negotiations of Centre and Periphery in New Zealand Poems by New Zealand Composers, 1896 to 1993”. PhD thesis, University of Auckland, 1994.

Skerrett Tainui, Angela, dir., Miri Stacey Flemming, Angela Wanhalla and Paul Diamond. Princess Iwa, the Maori Contralto, Whakamaharatanga o Iwa. Christchurch: Kereti Productions, 2011. CD.

Smith, Beaumont, dir. The Adventures of Algy. Wellington: New Zealand Film Archive/ Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiāhua, 1925. 20007.0072, film.

“The Adventures of Algy”, Bathie Stuart Papers. MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Drop folder. New Zealand Film Archive/ Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiāhua, Wellington.

Thomson, John Mansfield. A Distant Music: The Life and Times of Alfred Hill 1870–1960. Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Wanhalla, Angela. In/Visible Sight: The Mixed-Descent Families of Southern New Zealand. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2009.

Williamson, Judith. “Woman is an Island: Femininity and Colonization”. In Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. by Tania Modleski. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986: 99–119.

1 Tavia Nyong’o, The Amalgamation Waltz: Race, Performance, and the Ruses of Memory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 13.

2 Jane R. Goodall, Performance and Evolution in the Age of Darwin (London: Routledge, 2002), 5.

3 Martin Nachbar, “Tracing Sense/Reading Sensation: An Essay on Imprints and Other Matters”, in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment, ed. Mark Franco (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 19–33.

4 I also met and shared my research with Iwa’s surviving grandson, Ibsen Barclay, who has lived his entire life in London.

5 Angela Skerrett Tainui, Miri Stacey Flemming, Angela Wanhalla and Paul Diamond, Princess Iwa, the Maori Contralto, Whakamaharatanga o Iwa, Kereti Productions, 2011.

6 Mark Franco, “Introduction: The Power of Recall in a Post-Ephemeral Era”, in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment, ed. Mark Franco (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 1–19.

7 Lloyds Weekly News, 15 October, 1911 n.p., Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, Box X – Photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs etc., the property of Mr. J.S. Barclay, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

8 Paul Diamond, Makereti: Taking Māori to the World (Auckland: Random House, 2007), 96. At the time Papakura was referred to as “Maggie” publicly. Her archives held at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, are named “Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers”. Her birth name was Margaret Thom. Makereti is the Māori transliteration of Margaret.

9 Sydney Sunday Sun, 1 January 1911, n.p. Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, newspaper clipping, 25 December, 1910, cuttings and ephemera 1901–10, Box VII, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

10 “Dunedin Competitions”, Otago Daily Times, 1 October 1909, 6, https://bit.ly/3yPuPiz; “A Contralto with a Future”, Evening Post, 1 October 1909, 7, https://bit.ly/3Pb66ul.

11 Hill lived from 1869 to 1960, thus his working life spanned both the ninetenth and twentieth centuries.

12 “‘Hinemoa’ and Other Original Works”, Evening Post, 19 November 1896, 5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP18961119.2.52.

13 Sarah Shieff, “Magpies: Negotiations of Centre and Periphery in New Zealand Poems by New Zealand Composers, 1896 to 1993” (PhD thesis, University of Auckland, 1994), 18, 28–29.

14 Mervyn McLean, Maori Music (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996), 313.

15 Alfred Hill, Waiata Maori: Maori Songs Collected and Arranged by Alfred Hill (Dunedin: John McIndoe, 1917).

16 Judith Williamson, “Woman is an Island: Femininity and Colonization”, in Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tania Modleski (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986), 112.

17 John Mansfield Thomson, A Distant Music: The Life and Times of Alfred Hill 1870–1960 (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1980), 81–83. Hill’s obituary in the New Zealand Listener heralded Waiata Poi as “the most popular and best-loved of all New Zealand songs”, New Zealand Listener, 18 November 1960, 34.

18 Norwood News, 30 September 1911, n.p., Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs etc., the property of Mr. J.S. Barclay, 1984, Box X, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

19 The Daily Mercury, 5 October 1916, n.p., Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs etc., the property of Mr. J.S. Barclay, 1984, Box X, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Magyar refers to native Hungarian.

20 Clipping, n.d. Entertainments: Ayr Burgh Choir Concert, Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs, etc., property of Mr. J.S. Barclay, 1984, Box X, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

21 Clipping, n.d. Entertainments: Ayr Burgh Choir Concert, Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, 67.

22 Bystander, 1 November 1911, n.p., Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs etc., the property of Mr. J.S. Barclay, 1984, Box X, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

23 Bystander, 1911. Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers.

24 The Times, 17 October 1911; Croyden Times, 11 October 1911, Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, photocopies of an album of newspaper cuttings, photographs etc, the property of Mr. J.S. Barclay, 1984, Box X, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

25 Angela Wanhalla, In/Visible Sight: The Mixed-Descent Families of Southern New Zealand (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2009), 115.

26 Mervyn McLean, Maori Music (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996), 275. McLean presents several reasons why Māori singing and loss of singing traditions occurred in the wake of colonisation, including a decline in song composition by Māori, loss of cultural practices where singing was integral, fear of incorrect delivery or memory loss of words leading to ill fortune or death, and loss of language. See Maori Music, esp. Chapter 18.

27 Mervyn McLean, Maori Music, 275.

28 Clipping, n.d. Entertainments: Ayr Burgh Choir Concert, Maggie Papakura – Makereti Papers, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

29 Glasgow Bulletin, 25 August 1921, 6.

30 Glasgow Evening News, 30 August 1921, Playbills 1921, clipping, Mitchell Library, Special Collections, Glasgow.

31 See Jane Desmond for a discussion of these non-Indigenous women who performed “Hawaiian” on popular stages in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Jane Desmond, Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

32 Alison M. Kibler explains how, with performances such as Al Jolson’s in the 1927 film The Jazz Singer, blackface acts “constructed new American identities” as “a link between old and new identities … and the ‘whitewashed’ histories of racial unity”. This “whitewashing” of history was also present in New Zealand society during Bathie Stuart’s career. Alison M. Kibler, Rank Ladies: Gender and Cultural Hierarchy in American Vaudeville (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 115.

33 Bathie Stuart Papers, MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Folder 3, New Zealand Film Archive/Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiahua, Wellington.

34 Transcript of interview with Bathie Stuart by Julie Benjamin, Laguna Beach, 1 February 1984, Bathie Stuart Papers, MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Folder 3, New Zealand Film Archives/Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiahua, Wellington.

35 James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000 (Auckland: Penguin Books (NZ) Limited, 2001), 191.

36 New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1923, http://www3.stats.govt.nz/New Zealand Official Yearbooks/1923/NZOYP, accessed 29 November 2012.

37 “Maori Opera Company: Hinemoa at the Opera House”, Poverty Bay Herald, 14 October 1915, 7, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/PBH19151014.2.49.

38 Unlike earlier nineteenth-century usage of this term, applied primarily to men who had “turned” Māori and adapted to a Māori way of life and were possibly taking a Māori wife, “Pakeha Maori” as applied to Stuart signified her performance repertoire and stage costumes with the express acknowledgement that she was indeed a Pākehā.

39 “Miss Bathie Stuart and her Maori Maids”, Auckland Star, 8 May 1926, 18, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19260508.2.156.5.

40 Bathie Stuart, Ref TO 1 118 5/3 part 1, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

41 These are the titles of the songs as referred to at the time. See: Michael Brown, “Hoki Mai Ra”, National Library of New Zealand, 11 August 2014, https://natlib.govt.nz/blog/posts/hoki-mai-ra. More recent popular names of these songs are “Hoki Hoki Tonu Mai” and “Po Karekara Ana”.

42 Kibler, 126.

43 The Adventures of Algy, Bathie Stuart Papers, MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Drop folder, New Zealand Film Archive/Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiahua, Wellington.

44 The Adventures of Algy, 20007.0072, New Zealand Film Archive/Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiahua, Wellington.

45 Marianne Schultz, Performing Indigenous Culture on Stage and Screen: A Harmony of Frenzy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 147.

46 Bathie Stuart Papers, MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Folder 1, New Zealand Film Archive/Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiahua, Wellington.

47 Schultz, 151.

48 Transcript of interview with Bathie Stuart by Julie Benjamin, Laguna Beach, 1 February 1984, Bathie Stuart Papers, MA 1591, MANS. 0010, Folder 3, New Zealand Film Archive/Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiahua, Wellington.

49 Bathie Stuart Papers, TO 1 118 5/3-1, Archives New Zealand, Wellington. Bathie Stuart died in California in 1987, aged 94.

50 Letter to the New Zealand Government Publicity Department, Overseas Publicity Board, Wellington, from Bathie Stuart, 29 October 1929. Bathie Stuart Papers, TO 1 118 5/3-1, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

51 Charles Lindholm, Culture and Authenticity (Malden: Blackwell, 2008), 21.

52 “Return of the Maoris: Causes of the Failure”, Auckland Star, 10 January 1912, 8, https://bit.ly/3RgNpHE.

53 Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Random House, 1994), xxv.