1

Vitality and change in Warlpiri songs and ceremonies

Milya-pinjaku warlaljaku kuruwarriki manu jukurrpaku ngulaju yangka yaninjaku juju (ceremonies)-kurra jukurrpaku nyanjaku manu milya-pinjaku. Yungurlupa mardarni jukurrpa tarnngangku-juku. Juju, yangka nganakurlangu warlalja (families)-ku. Yalumpu ngulakanpa nyina, kajikanpa kanginy-karri, yangka jujungka manu jukurrparla ngulakalu yirrarni.

To know our own kuruwarri and stories we must go to the ceremonies so we can learn about them. We must look after them and remember them. We can keep them for ourselves, for our own knowledge. How can we know who they belong to, to which families? You might not know who a design or a ceremony belongs to. But by attending these [ceremonies] you will know these jukurrpa.

Nganaku purda-nyanjaku, nganangkulpangku ngarrikarla? Yungunpa pina-pina-jarrimi kuruwarriki. Nyarrpara-wana-jangka nguru-jangka manu nyarrpara-wana-jangka jukurrpa parnka manu ngurukari-kirralku ka yanirra. Nyarrpa karlipa kanginy-karri, nganangku kapu-ngalpa pina-pina-mani kurdu-kurduju … (our generations today). Yangka warlalja (family) nganakurlangu family kujarra generations murnma kaji yanirni. Yungulu milya-pinyi kurdukurdurlu (our generations) jalangu-warnu-paturlu. Nyarrpa kalu-jana rdanparni jukurrpa-kurraju ngana-kurlangu? Nganangkulku kapu-jana pina-pina-mani nyampurra kajilpalu walku- jarrimi? Nganangkulku? Yungurlupa ngalipa-nyangu juju milya-pinyi junga-nyayirnirli jukurrpa-wati manu kuruwarri-wati. Nganangkulku kapi-jana pina-pina-mani yalumpurraju jukurrpaku manu kuruwarriki? Nganangkulku kapu-ngalpa pina-mani kurdu-kurdu ngalipa-nyangu?

How can you know about your jukurrpa and stories? Who is going to tell you or teach you about which country you are from and what you should know? Which country does the jukurrpa travel from and where does it go to? We worry a lot about how we can learn! Who is going to teach us and our kids now, today? Our own family that belongs to that [Dreaming] should keep passing on this one, so that our kids today will know how our jukurrpa and stories are connected. How will they know that? Who will teach them? Who? Who will teach us our own jukurrpa and stories the right way. Who is going to teach them that strong knowledge about jukurrpa and kuruwarri? Who is going to teach them those jukurrpa stories? Who is going to keep teaching our kids in the near future?

Jalangurluju, jalangurlu-juku yungunkulu milya-pinyi jukurrpaju nyurrurla-nyangu warlalja-kurlangu, nyarrpara-wana kajinpa yani. Ngana-kurlangu yungunpa milya-pinyi manu yungunpa-nyanu milya-pinyi nyuntu-nyangu warlalja-nyayirni nguru-jangka nyarrpara-jangka kuruwarriji nyarrpara-jangka jukurrpaju. Nyarrpara-wana-jangka yanurnu, nyarrpara ka yani? Kujarra. Yangka milya-pinja-nyayirniki yungulu ngalipa-nyangurlu kurdu-kurdurlu jalangu-warnu-paturlu milya-pinyi, manu mardarni yungulu, kajili wiri-jarrilki yungulu-jana yinkijirni nyampurra kuruwarriji yinyakarilki yinyakarilki yinyakarilki kurdukarilki nyanungurra-nyangu. Kujaku karna wangkami.

Now, today you should know and acknowledge our own family connections, so that our kids will know their cultural heritage. How can you know for sure your own jukurrpa and stories from your country, where it comes from? Where is it going? Like that. So that our kids today will really know and acknowledge their own stories and jukurrpa, and keep them. When they grow up and come to know their jukurrpa and stories and to pass them on to the next generation, to their kids, to their kids and so on, generation to generation.

Nyiya-jangka karnalu warrki-jarrimi? Nyiya-jangka? Jalangu-warnupaturlu kamparru-warnurlu yungulu milya-pinyi-nyayirni ngingingingirli. Nyanungurra-nyangu warlaja-nyanu jukurrpa. Nyarrpara-jangka nguru-jangka yanurnu? Yungulu-nyanu mardarni nyanungurra-nyangu, warlalja-kurlangu juju. Yungulu-jana pina-pina-mani nyanungurra-nyanulku kurdukurdulku. Kamparru-warnupaturlu ngulaju … yungulu yani nyanjaku warlalja nyanungurra-nyangu jukurrpa.

Why are we doing this work? What for today? So that our generations today can know for sure and keep their own stories and jukurrpa and their knowledge, their cultural heritage. Where did [that jukurrpa] come from? Where did it go? How far? They are their own stories and jukurrpa. So that from generation to generation they can teach their kids, our future generations, even the ones here can teach our future generations.

Ngaliparlu yungurlupa-jana manngu-nyanyi wiyarrpa ngalipa-nyangu family yungurlupa-jana kujanya proud nyina. Yungurlupa-jana kujarlu manngu-nyanyi tarnngangku-juku. Jukurrpa, kuruwarri kalalu milya-pinjarla nyurruwiyi-nyurruwiyi langangku mardarnu. Mardarnu kalalu-nyanu jujuju kujapiyarlu. Family connection kalalu-nyanu mardarnu junga-nyayirnirli. Yirriyirrirli kalalu kuruwarriji milya-pungu manu jukurrpaju. Nganalpa yukayarla yangka kujarra-piya kala-nyanu milya-pinjarla ngarrurnu … jungarngirli right way. Ngana-kurlangu jukurrpa? Kalalu-jana yinyapatu kujarra-piya langa-kurra mardarnu jukurrpaku-ngarduyurlu? Kalalu-jana wiyarrparlu mardarnu ngulalpalu nyurruwiyi-nyurruwiyi jujungka nyinaja. Nyinanjarla kalalu-nyanu purda-nyangu tarruku-nyayirni nyurru-warnu-paturlu.

All of us now we can think back and remember and be proud of our families and keep remembering forever. How they used to be strong and had knowledge and kept it in their minds from way back a long time ago for their jukurrpa and stories. Like that. They used to know their connections and were really careful with their kuruwarri and their jukurrpa. They were careful of who could join in and who could not – they did it the right way. They used to wonder and ask who the jukurrpa belongs to, like that, they would hear/see it and know who it belongs to. The poor things, they used to keep ceremonies and the knowledge from a long time ago. They would sit and listen to one another about the really sacred things from way back.

(Statement and translation by Valerie Napaljarri Martin)

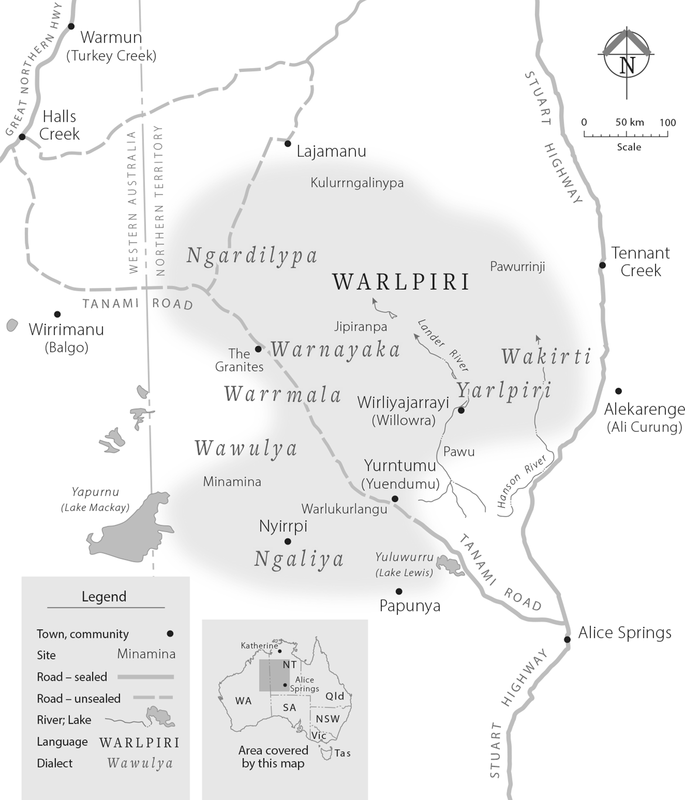

Ceremonies are vital to the cultural identity of Warlpiri people living in communities across the Tanami Desert region of Central Australia (see Figure 1.1). At the heart of ceremonies are the songs that make ceremonies effective; that celebrate people’s relationships to the land; and that encode detailed information about Warlpiri Country, cosmology and kinship.

Figure 1.1 The Warlpiri regions. (Map by Brenda Thornley)

Warlpiri ceremonies are organised into named genres and repertories comprised of defined songs whose textual, musical and dance characteristics mark them as belonging to particular groups of people who also own the associated Country and cultural knowledge. Today, however, the ceremonies in which the songs are sung are in decline, and only a small group of the eldest generation has full knowledge of the songs and their associated meanings. For many Warlpiri people, as Valerie Napaljarri Martin emphasised above, this raises a level of uncertainty about how these important aspects of their cultural life will be carried forward into the future. Can the songs continue to have meaning without the ceremonial contexts?

In 2018 Warlpiri Elder Rex Japanangka Granites (c. 1949–2019) replied to questions on whether he was concerned about a decline in knowledge and practice of songs among younger generations of Warlpiri people in the following way:

Well with our old songs, they should be taught, because that’s the songline. We can’t change it because it’s there all the time, you know the country never changes. Kuruwarri tracks are always there. I mean, the songs don’t change, it’s there because we still sing the tracks of how it is. Like if it’s trees or rocks, it never changes, you never pull it down. It’s there all the time in the tracks. (R. Granites 2018)

In this way, he compared his Warlpiri Country to a living archival repository; because Warlpiri cultural heritage is held to be within Country eternally, he expressed his assured faith and optimism around its safety, continuity and future. As is the case for many Aboriginal peoples across Central Australia whose worldviews centre around a timeless creational epoch known in Warlpiri as jukurrpa, historical time merges with the present and the future (Myers 1986, 48–54), accounting for this affirmation of the ever-presence of Ancestral Beings and their songs and stories. Other Warlpiri Elders also share this view. For example, senior yawulyu singer Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites stated that:

Nyampuju tarnnga-juku ka nguna, jukurrpaju ka nguna tarnnga-juku. Nuulpa change-jarriyarla-rlangu lawa. Tarnnga-juku ka nguna jukurrpaju, kajili kamparru-warnu-paturlu wajawaja-maninjayani, kapu yinyakarirlilki mardarni jujuju.

[Songs are] always here forever. There will be no change. Jukurrpa is here forever. If the older generations pass on, then the younger generations can carry on with the ceremonies. (Granites and Brown 2017)

While these assertions pervade the thinking of older generations of Warlpiri people, there is also deep reflection on the past vibrancy of ceremonial life and its decline in recent decades. When listening to recordings of Warlpiri women’s ceremony made in the 1970s, senior female singer Lynette Nampijinpa Granites nostalgically reflected:

Back then there were so many women dancing. Listen to their feet – there are so many of them. We used to do business every day back then. Now we only do it sometimes. (Granites and Brown 2017)

The same Elders also reiterate the importance of making sure that younger generations have the means to reactivate and access the songs and ceremonies in the future. Another Elder and prominent yawulyu singer, Peggy Nampijinpa Brown, explained that:

Kuruwarriji tarnngangku-juku, kurdu karnalu-jana pina-pina-mani yangka, yungulu kurdungku mardarni tarnngangku-juku ngula karnalu-jana pina-mani. Nyampunya karlipa-janarla yirrarnilki.

Kuruwarri are here forever, we teach the young generations so they can learn and keep the culture with them. That’s why we teach them. That is why we are doing this work [documenting songs]. (Granites and Brown 2017)

Nyirrpi-based yawulyu singer Alice Nampijinpa Henwood (2018) explained how she addresses this concern by proactively teaching younger generations about songs and ceremonies and continually reiterating the importance of the stories for their family history and cultural heritage:

Wangkami karna-jana yangka “Nyuntu-nyangu warringiyi-kirlangu-nyanu yunpaka waja, nyampukari yangka warringiyikari-kirlangu yunparni”. Wangkami karna-jana yangka kalu nyinami, nyinami yangka kalu. Nyuyu-mani karna-jana, wali wangka karnalu, wangka karna-jana ngajulu yungulu yangka jungangku yangka warringiyi-nyanu-kurlangu might be yapirliyi-nyanu-kurlangu yunparni. Warringiyi-nyanu-kurlangu-juku- jala, ngula-kurlangu yungulu yangka yunparniyi nyanungurrarlulku kajili yangka lawarra jarrilki ngularlanguku yangka.

I say to them “This is your grandfather’s Country and Dreaming – you sing it”. I get them together and they listen to me when I tell them the stories about their grandfathers’ and grandmothers’ Dreamings. So later on when we pass away they can carry on with the singing. (Henwood 2017)

Responding to these concerns about the passing on of knowledge of ceremonies and their associated songs, this chapter addresses the tension between the continuity of tradition and the inevitability of change. Although Warlpiri people are often adamant that jukurrpa ancestors created traditional songs in the exact forms in which they are sung today, changes to and inventions within Warlpiri song forms are common and easily incorporated into this Warlpiri understanding of song transmission. Françoise Dussart (2000) has detailed the Warlpiri process of dreaming “new” songs – a phenomenon also addressed by Stephen Wild (1987) and illustrated in Chapter 4 of this book by Glowczewski and Gibson. Both Ken Hale (1984) and Peter Sutton (1987) have discussed processes by which songs are sung with slight but deliberate differences so that knowledgeable Elders have avenues for control of the dissemination of knowledge and creativity while maintaining the powerful essence at the core of the ceremonial manifestations of jukurrpa (see also Marett 1994; Merlan 1987; Sutton 1987). The renowned ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl explained this relationship of the past to the present as “the idea that something that a society maintains and shares can change in character and detail and yet remain essentially the same” (Nettl 1996: np).

This conceptual framework allows for change in different ways and at different rates, while also recognising the ever-presence of a life-force or essence that is referred to by Warlpiri people as jukurrpa or kuruwarri.1 This essence is held consubstantially within places on Warlpiri Country, within Warlpiri people with inherited ties to it, and within songs and ceremonies. In Chapters 3–10, the authors present case studies of different aspects of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies as they relate to continuity and change. Each of these is historically contextualised, some are based on ethnographies of past decades (e.g., Chapters 3, 4 and 9), some on more contemporary initiatives (e.g., Chapters 8 and 10), and others have as their focus the analytical aspects of musical details in recordings (e.g., Chapters 5, 6 and 7). In this chapter, we address some of the major themes that arise through this concern with continuity and change, particularly through an assessment of the present-day vitality of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies, barriers to intergenerational transmission and considerations for potential revitalisation. We begin, however, by setting out the social and musical context against which to consider these issues.

The Warlpiri social and musical context

The Warlpiri region of Central Australia dominates the expansive Tanami Desert covering a broad region north-west of the major town of Alice Springs, flanked by Lake Mackay on the western side and Anmatyerr communities, including Yuelamu, Laramba and Ti-Tree, on the eastern side. Willowra lies on Warlpiri land, but many people residing there also have Kaytetye, Anmatyerr or Alyawarr links. The most northern Warlpiri community, Lajamanu, is located on Gurindji Country, but close by to the south is Warlpiri land with its associated jukurrpa, songs and ceremonies. The southern part of Warlpiri Country borders Luritja and Pintupi lands and the communities of Papunya, Haasts Bluff and Mount Liebig.

In Alice Moyle’s 1974 classification of musical regions of Australia, Warlpiri groups are within the region described as “‘C’ Central and South Central (interior Northern Territory to Bight)” (1974, xiv), encompassing a large section of the western half of South Australia and all the Central Australian region of the Northern Territory. Moyle described songs in this region (as well as many others in Australia) as “Continuous” in that they have “similar strings of syllables and melodic divisions marked by descents. The sound instruments used in accompaniment … belong to the idiophone class [percussion instruments]” [emphasis in original] (1974, 352). According to Moyle, other shared features across this region are the use of sound instruments to mark a finish to singing, song items of comparatively short duration (one minute or less) and several vocal descents within the one song item (Moyle 1974, 352). She also noted similarities with the region to the west, an influence recognised more recently by Treloyn (2017) despite Moyle’s categorisation of the Kimberley as a different “musical region”.

Aboriginal groups across this desert region and beyond engaged in significant trade and exchange of songs and ceremonies well before Europeans arrived. Some Elders today reflect on these histories to time-depths well beyond their own memories. A recent example of ceremonial borrowing is evident in the present-day Kurdiji ceremonies held each summer for the initiation of young boys into adulthood, in which the original Warlpiri Kirrirdikirrawarnu ceremony has been replaced by the simpler and less time-intensive ceremony Warawata, borrowed from Pintupi groups in the south (Curran 2020; Myers 1986). Despite the complexity of the interrelationships between different Aboriginal groups and the fluidity of ceremonial authority in contexts of trade and exchange, Warlpiri people are quite clear about the lines of authority with regards to being “boss” for ceremonies, so much so that there are bitter disputes on the rare occasions when this is questioned. Ceremonies, and their role in fostering social connections between groups, have been a primary reason for extensive travel across this region. Widespread travel continues to this day, with most Warlpiri people undertaking long-distance journeys to participate in initiation ceremonies in various locations across the desert, a practice only enhanced as more Warlpiri people have come to own cars since the 1970s (Peterson 2000).

Since the establishment of settlements across Warlpiri Country in the years following World War II, there has been a tendency for larger-scale ceremonies that are inclusive of more community members to predominate (Kolig 1981; for descriptions of the sweeping “Balgo business” in the 1980s, see also Laughren 1981; Wild 1981; Young 1981). By far and away, the most common of these today are the regional variations of the Kurdiji (for initiation), which has expanded significantly in scale in the last five decades, now often involving hundreds of people from numerous family groups. Smaller-scale site-based ceremonies are nowadays only held in connection with Kurdiji ceremonies. However, senior Warlpiri singers hold in their minds a score or more of different jukurrpa, each including many unique songs.

Table 1.1 lists the main Warlpiri song genres, named according to the ceremonies in which they are sung.2 The table distinguishes these different genres based on performative restrictions, the gender of the performers and the ceremonial contexts in which they are performed. These are the genres of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies currently known by singers living in Warlpiri communities today.

Table 1.1 Features of Warlpiri song genres and ceremonies based on contemporary attitudes (which may shift over time).

|

Song genre / ceremony name |

Performance restrictions (restricted, private, public) |

Gender of performers |

Ceremonial contexts in which they are sung |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kurdiji (songline chosen from community) |

Public |

Male singers, female dancers |

Kurdiji (initiation ceremonies) held in public community contexts |

|

Jardiwanpa/Ngajakula |

Public |

Male singers, female dancers |

Conflict resolution ceremonies (see Chapter 8) held in public community contexts |

|

Parnpa |

Restricted to men |

Male singers and dancers |

Components of Kurdiji, private men’s contexts |

|

Purlapa |

Public |

Male and female singers, male dancers |

Public community events |

|

Yilpinji (men’s and women’s) |

Restricted to men or women only, some men’s songs are sung in public contexts |

Male singers and dancers, or female singers and dancers |

Gender-restricted contexts |

|

Yawulyu |

Private and public (depending on performance context) |

Female singers and dancers |

Private women’s contexts and public community events |

|

Jilkaja-ku |

Women only |

Female only (boys and men are asleep) |

While accompanying boys on jilkaja (initiatory) journeys |

While some of these genres share names and basic forms with neighbouring Aboriginal groups (e.g., yawulyu, or awely in Arandic languages, are sung by women across Central Australia; Gurindji wajarra have similar entertaining purposes to purlapa), others are distinctly Warlpiri. Warlpiri songlines relating to sites on Warlpiri Country are also incorporated into imported ceremonial forms traded from other regions. For example, the Jardiwanpa/Ngajakula ceremonial complex, held high by people in Warlpiri communities, has historical links to the north-east from where it was brought south-west to Warlpiri Country in the early 20th century. A version of this ceremony was described by Spencer and Gillen (1901) as it was held among Warumungu people near Tennant Creek. Despite its origin, the Warlpiri Jardiwanpa does not relate to Warumungu Country but rather is centred around a songline beginning at Wirnparrku (west of Haasts Bluff) and travelling northwards through owned Warlpiri sites (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of a counterpart and similarly performed ceremony: Ngajakula). The larger-scale ceremonies held by Warlpiri people today, like Kurdiji, may include sections of different genres, with men and women separately performing parnpa and yawulyu in the earlier stages and later joining to sing Kurdiji songs in the all-night section of the ceremony.

Musical vitality of Warlpiri song genres

Internationally, there are some standard measures of musical vitality, including trends in the number of proficient musicians, the age range of participants and the performance frequency and contexts. Catherine Grant’s “Musical Vitality Endangerment Framework” (2014) is a 12-factor assessment tool to systematically measure the vitality or endangerment of music genres worldwide. Both a quantitative and qualitative measurement is given against each of the factors. Schippers and Grant further argue that this systematic way of measuring musical vitality is important for at least three reasons:

- To enable diagnosis of situations of music endangerment and determine the urgency to implement initiatives towards sustainability;

- to ensure the right remedial action is taken, as assessing the factors causing endangerment will help establish focus and priorities for action, and

- to enable methodical evaluation of the efficacy of any efforts to maintain or revitalise the music genre. (Schippers & Grant 2016, 106)

Such a tool provides one way to measure the vitality of Warlpiri songs against a broader international context. Additional measures specifically developed for Aboriginal Australian song include the average number of unique songs performed per occasion, changes in the relative frequency of performance of different songs and the musical diversity of song repertoires (e.g., how many different tempi, melodies and rhythmic types are performed per repertory over time; Treloyn and Charles 2021; Treloyn, Martin and Charles 2016). In Warlpiri contexts, the number and complexity of specific dances performed and kuruwarri designs painted are also important measures of ceremonial vitality.

While presenting points for comparison with the transmission of oral traditions on a broader international scale, such data must be set against broader understandings of transmission and vitality of ceremonial song in Aboriginal Australia developed by and with practitioners, including practitioner understandings of the contemporary decline in the holding of ceremonies and collaborative development of practical ways by which song transmission can be revitalised.

The assessment presented in Table 1.2 has taken “Warlpiri song” as a general category, encompassing all genres outlined in Table 1.1. We acknowledge that some Warlpiri genres, and certain repertories within these genres, have relative strength compared to others and have included more specific comments to this effect in italics in the “Assessment of Warlpiri songs” column. We have followed the guide as set out by Grant in undertaking this assessment (2014, 111–24). For further consideration of how the Warlpiri context compares to other international contexts on this scale, Grant’s guide is a useful reference. Grant’s assessment requires placement of the music genre on a scale from 0 to 5, representing increasing vitality.

Table 1.2 Assessment of the vitality of Warlpiri song genres against the 12

factors of Grant’s “Music Vitality and Endangerment Framework” (2014).

|

Grant’s 12 factors |

Degree of vitality (0–5) |

Assessment of Warlpiri songs (using Grant’s assessment rubrics and with Warlpiri specific comments in italics) |

|---|---|---|

|

Factor 1: Intergenerational transmission *A key indicator of strength |

2 Severely endangered: the music genre is performed mostly by older generations. |

Some younger people attend ceremonies and participate in dancing and are painted with designs but are not learning how to sing. |

|

Factor 2: Change in number of proficient musicians in the past 5–10 years |

1 Significant decrease in proficient musicians. |

Songs are only known by a small group of Elders, and many have passed away in the last 5–10 years. |

|

Factor 3: Change in number of people engaged with the genre in the past 5–10 years |

2 Moderate decrease in people engaged with the genre. |

Many older singers are passing away with an overall decrease in engagement. Nevertheless, there is some recent interest in revitalisation projects from middle and younger generations. |

|

Factor 4: Pace and direction of change in music and music practices in the past 5–10 years |

1 Pace and direction of change reflect significantly decreased strength. |

For most songs, there is a rapid rate of change in a negative direction (harmful for the music genre). For public genres, particularly yawulyu but also purlapa to a lesser degree, new contexts for performance are being taken up and the rate of change is slower (more people retaining) and more positive (is useful for maintenance of the music genre). |

|

Factor 5: Change in performance context(s) and function(s) in the past 5–10 years |

2 The music genre is performed only in irregular formulaic contexts and functions. |

Warlpiri songs are mostly performed in ceremonial contexts, so their social function has changed, but this does not apply to Kurdiji in the summer ceremonial season. |

|

Factor 6: Response to mass media and the music industry |

2 Weak – The genre shows reluctance in its engagement with and response to mass media and the music industry. |

Senior singers are not interested in engagement, and younger people feel a lack of authority to drive engagement with mass media. |

|

Factor 7: Accessibility of infrastructure and resources |

4 All infrastructure and resources required for creating, performing, rehearsing and transmitting the music genre are accessible, but not necessarily easily. |

Minimal infrastructure and resources are required and are mostly available (e.g., ochres, feathers, materials), although there can be some difficulty in accessing these. |

|

Factor 8: Accessibility of knowledge and skills for music practices |

1 The community holds only some of the required knowledge and skills. |

Warlpiri songs are embedded in complex multimodal ceremonial forms, which only a small number of people have the learned skills and knowledge required to perform. |

|

Factor 9: Official attitudes towards the genre |

4 The genre is supported through overarching policies supporting cultural expressions, without differentiation and without consultation with culture bearers. |

Australian governments provide theoretical and funding support for “maintenance of endangered songs” but do not consult with Warlpiri singers about their specific context. |

|

Factor 10: Community members’ attitudes towards the genre |

3 Community support for the maintenance of the music genres is moderate. |

Warlpiri Elders and middle-aged generations are proud of these traditions and see them as core to their cultural identity, whereas younger generations see them as old-fashioned. |

|

Factor 11: Relevant outsiders’ attitudes towards the genre |

4 Support for the music genres by relevant outsiders is strong. |

Staff of community organisations and researchers provide support for activities that promote and set up regular performance contexts. There is also interest in the music genres from a broader intercultural audience outside Warlpiri communities. |

|

Factor 12: Documentation of the genre |

2 Limited documentation exists in varying quality. |

Warlpiri women’s yawulyu have been better documented than other genres of Warlpiri song, but many repertories remain undocumented, and only a small number have been documented in an accessible and usable way, although current work is adding to this. |

Eight of the 12 factors (1–6, 8, 12) firmly place Warlpiri song in a category of endangerment, which is a red flag, as many senior and middle-age generations of Warlpiri people recognise, as do outsiders who understand these kinds of song traditions to be unique and valuable expressions of humanity (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2021). As expressed by Fisher:

[Support for ceremonial vitality] is dear to my heart as a Warlpiri man. Within my lifetime I have witnessed the decline in traditional modes of transferring knowledge that is core to Warlpiri identity. This project will initiate new ways for our community to ensure the passing on of this knowledge to younger generations.

Despite their clear endangered status, the ceremonies and their related songs remain key to Warlpiri life and cultural heritage; Warlpiri people, young and old, express a deep desire for their continuation even if they are unable to muster the support to hold the ceremonies. It is significant to note from the above assessment of musical vitality that, despite the challenges to intergenerational transmission and struggles to pass on the knowledge required to sing songs, there is community interest in supporting the maintenance of Warlpiri song (Factors 9 and 10), and the relevant infrastructure continues to be available (Factor 7), as well as relatively good levels of support from outsiders including researchers and non-Warlpiri staff who work at community organisations (Factor 11). Although considerable efforts to document the songs have been made (Factor 12), existing documentation is patchy (especially indexing of older material, which affects searchability). Community-led efforts to improve documentation of certain genres (e.g., yawulyu) have served to highlight the urgency and complexity of undertaking this time-consuming work with other genres. This work is dependent on strong collaborative relationships between Warlpiri Elders, Warlpiri linguists and language workers; younger participants; and support from researchers and community organisations (Curran 2020; Curran, Fisher and Barwick 2018).

Barriers to intergenerational transmission

Despite all this interest and concern, loss of song knowledge is unavoidably continuing apace. This is because it is an effect of modernisation. For older Warlpiri people, songs and the ceremonial contexts of their singing have been instrumental in achieving a wide range of practical ends ranging from affecting the weather, affecting people’s affections, curing sickness, making people fall sick, causing plants and animal species to flourish, making boys into men and resolving disputes, to mention the most important. The loss of song knowledge is driven by a complex of factors, including declining acceptance of the instrumental effectiveness of some of the ceremonies and, therefore, the motivation to hold them. Other important factors are changing world views and loss of detailed knowledge of Country (Barwick, Laughren and Turpin 2013). These key factors also reflect changing demographics within the Warlpiri communities, marked by an expanding young population and an older population with disproportionate levels of chronic illness. Although increased mobility has extended the range of social networks across the desert (Peterson 2000), leading to initiation ceremonies becoming larger than ever, this is putting disproportionate pressure on the few senior men who possess the knowledge and fitness required to sing the songs for them, and fewer individuals seem to be actually mastering the related songlines (Curran 2011; Peterson 2008).

While Grant’s music vitality assessment emphasises that a key indicator of the strength of a musical genre is the level of intergenerational transmission, the loss of song knowledge is not about musical tradition, as such, but rather the loss of the significance of the ceremonies and, therefore, the motivation of the younger generations to invest the necessary discipline and time required to learn the songs. The songs cannot just be picked up through rote learning or copying what is heard on a recording because their significance is embedded in ceremonial purpose and is highly multimodal, joining singing with dancing, body decoration and ceremonial constructions. Musically, these songs come together in complex ways, with the words and rhythms to which verses are set needing to be matched to melodic forms that are not the same each time the song is performed (Curran and Yeoh 2021). To be able to pick up these musical skills, extensive background experience participating in ceremonial contexts is essential; however, the issue of belief is also fundamental.

For songs to have a life independent of their traditional ceremonial context, there must be a repurposing that provides people with a meaningful motivation to learn and perform them. Warlpiri women have successfully achieved this in relation to the yawulyu genre that was in the past particularly linked to women’s health maintenance and conflict resolution but which has now found a role in the intercultural domain of cultural exchange such as exhibition openings (see Curran and Dussart 2023; Dussart 2004).

Some ideas for community-led revitalisation

Strategies for supporting the survival of the important cultural knowledge held in song, especially as it relates to place, are necessary if future generations are to have a way of accessing this. These must recognise that the old motivations for holding ceremonies are fading fast (with the exception of the Kurdiji ceremonies) and that new and rewarding forums need to be created if interest in songs is to be revitalised. Targeted projects across Australia, including the Top End (Marett et al. 2006), Kimberley regions (Treloyn and Charles 2015, 2021) and Noongar region (Bracknell and Scott 2019), have shown some success in revitalisation efforts. Here, we suggest several strategies for community-led revitalisation and engagement with vulnerable musical traditions. These suggestions have been developed from discussions within our project (detailed in Chapter 2), as well as noted successes in other similar projects.

1. Supporting existing ceremonial contexts

The late senior Elder H. Nelson highlighted that one of the main ways in which songs and ceremonial knowledge are passed on today is in the Kurdiji ceremonies held each summer, sometimes several times in individual Warlpiri communities (as well as other communities across Central Australia). Warlpiri people also travel widely across the desert to participate in these ceremonies in other communities with which they share social and ceremonial relationships. In these contexts, adult men often learn for the first time how to paint the designs of their patrilineally inherited jukurrpa, as well as how to dance to the parnpa. Women may also participate in yawulyu, and large numbers of people participate in dancing in the all-night component (Curran 2020). It is evident, however, that only a small group of senior men know how to sing the songs to pull this ceremony together. Providing practical and logistical support for these ceremonies, which are still being held annually, is perhaps one of the most crucial areas where revitalisation can occur.

2. Setting up and supporting performance spaces and occasions in communities

In many Warlpiri communities, there are initiatives to set up new spaces for the performance of these vulnerable song traditions. For example, Warlpiri women from across the Tanami Desert communities participate biannually in the Southern Ngaliya dance camps in which community organisations support a camp-out in an outstation near a Warlpiri community, including transport, food and payments for participation. The Women’s Law and Culture meeting led by the Central Land Council is another example of this kind of support for a set-up context.

Men have generally not sought the same level of support, but there have been grassroots efforts to revitalise purlapa in southern Warlpiri communities with Elders singing while instructing young men on how to dance (Curran and Sims 2021). This is empowering for Warlpiri men but lacks frequency as it does not occur to a schedule or have external support. By contrast, the biennial Lajamanu-based Milpirri festival (designed, in Wanta Steven Jampijinpa Patrick’s words, to “make jukurrpa relevant to the 21st century”; Biddle 2019) is carried out with external funding and in partnership with Tracks Dance Company (discussed in Chapter 10). Chapter 8 of this volume describes a song documentation project that aspired to the revitalisation of song knowledge of Ngajakula in Willowra. Warlpiri women from Yuendumu have also become involved in many projects to support yawulyu events, including setting up dance camp events and staged performances in larger cities and towns (Curran and Dussart 2023).

3. Documentation of song and ceremony

Song documentation, a recognised factor in Grant’s framework, has been undertaken for a number of decades in Yuendumu, with a recent surge in the last 10 years. While these documentary projects produce valuable resources that can be used by communities, it is the process of working on these materials that is one of the biggest factors contributing to revitalisation. Recent documentation work (Gallagher et al. 2014; Laughren and Turpin 2013; Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017; many of the chapters in this book) has contributed to a better understanding of Warlpiri songs but has made it obvious that the substantial recorded legacy of this important element of Warlpiri cultural heritage is still inadequately documented and thus of limited usefulness as a basis for revitalisation. It is urgent to bring older and younger generations of Warlpiri people together to document further details of the language, music and other associated cultural information for these legacy recordings – not only to pass down the cultural knowledge embedded in them but also to plan how to sustain their traditions into the future.

4. Engagement with archival materials

While we devote more attention to this in Chapter 2, it must be mentioned that engagement with archival resources contributes significantly to song knowledge. In reviewing and managing collections of audio, visual and audiovisual materials that have been made in Warlpiri communities, Warlpiri people can gain significant understanding and knowledge of vulnerable traditions (Curran, Fisher and Barwick 2018). In Chapter 2, we address this further.

5. Promoting performance to a broader audience

Aboriginal Australian arts, culture and languages represent and are recognised as crucial and highly visible components of Australia’s national identity; this high level of outside recognition can contribute to slowing if not reversing progress towards further endangerment. Opportunities for Warlpiri people to perform in broader public contexts engender support from outsiders who recognise the value of this unique song tradition and its encoding of biocultural knowledge and practices (Curran et al. 2019). Community engagement with research also enables Warlpiri voices to participate in national and international debates on Indigenous cultural heritage and to contribute to current assessments of music vitality. This unique and innovative Indigenous perspective has a bearing on questions of song repatriation and revitalisation and, ultimately, to understandings of song change. By sharing information with other communities affected by similar issues and the broader community, new collaborations can emerge across Australia and internationally. The impacts of globalisation in Warlpiri communities have been pronounced, with all younger people having easy and frequent access to social media, which dominates a large part of their lives. While this connectivity provides greater access to entertainment from outside (with the consequent withdrawal of attention from local contexts), it also enhances sharing of cultural information via digital means with families and the broader Warlpiri diaspora, as well as the general public (Vaarzon-Morel, Barwick and Green 2021).

Outline of book structure

This book includes profiles of a number of Warlpiri people who were involved in interviews conducted at Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications (PAW Media) in 2017–2019. Valerie Napaljarri Martin and Simon Japangardi Fisher led these interviews, which were conducted in Warlpiri, transcribed and then translated by Theresa Napurrurla Ross into English. In these interviews, some with respected Elders and some with emerging cultural leaders, individuals reflected on the changes to songs and ceremonies across their lifetimes and the value of access to written, audio, video and photographic documentation of these ceremonies through the Warlpiri Media Archive held at PAW Media. Perspectives from these interviews have been included in individual profiles and incorporated into the ideas presented in Chapters 1 and 2.

The chapters gathered in this book relate directly to the issues raised in this chapter addressing the central tensions for Warlpiri people who see songs as forever held in Country and fundamental to their cultural identity but struggle to maintain and foresee their relevance in the current and future Warlpiri lives in which ceremonies are becoming increasingly less important for social functioning.

Chapter 2, written collaboratively by a team of researchers who have been working in Yuendumu at PAW Media, focuses on archiving and the value of on-Country archiving in Warlpiri communities. The perspectives of Elders who were interviewed on this topic are central to this chapter; their voices articulate the ways in which archival resources can be utilised by future generations to connect to their cultural heritage. This chapter also outlines, through the history of Warlpiri Media Association, how many of these issues have been at the forefront of Warlpiri minds since the beginnings in the mid-1980s. It details documentary efforts reaching back to early expedition-style recordings to present-day Warlpiri-led efforts.

The remaining chapters all focus on particular songlines or ceremonial contexts. Chapters 3 and 4, both based on ethnography from the 1970s and 1980s, illustrate the ways in which change is inherent in Warlpiri ceremonies, with negotiation and adaptability being central features. Chapter 3 provides a case study of how the motivation to hold a certain class of ceremony is unintentionally destroyed by factors external to the Warlpiri community. It follows the specific negotiations required of Paddy Japaljarri Sims to hold a winter solstice ceremony that would form public community recognition of his succession to and control of an important area of Warlpiri Country. However, this traditional mode of proving links to land was made irrelevant by the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976; the 1979 success of the Warlpiri land claim meant that being on lists and genealogies held by the Central Land Council was the key to recognition of rights.

Chapter 4 documents the main way in which a songline can be changed not by loss but by addition. Gibson recounts and reflects on the process of dreaming a “new” song and the ways this was incorporated into established Ngapa “Rain” and Yankirri “Emu” jukurrpa collectively held by Warlpiri women. The authors also reflect on how this song responded to particular contemporary circumstances and was a necessary addition to the repertory as it renewed spiritual links to land by incorporating this song into those that had been passed down through generations.

Chapters 5, 6 and 7 all focus on analyses of the songs sung during particular recorded performance instances, all dealing with technical aspects of the musical, linguistic and performative complexity of classical women’s songs. Chapter 5 turns to the changes that have taken place in the Minamina yawulyu songline between 1972 and the 2010s. This chapter reveals that there have been significant changes in the extent and modes of performance, including song selection and explanation, musical setting and body designs; however, nevertheless, key themes expressed in song verses, music and body designs persist across the generations. In particular, those linked to connection to Country are emphasised, ensuring that a strong female cultural identity continues to be passed on to younger Warlpiri women.

Chapter 6 underlines the discipline and time that must be put into acquiring the old levels of performance, gives details of the rhythmic texts and reflects on the difficulty of working on the hard language of Warlpiri song in relation to two “edible seed” songlines. These are associated with Country around Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji, in the north-west of the Warlpiri region, as they were performed and explained by Fanny Walker Napurrurla. The analysis of the musical conventions of these songs as they are broken into verses uncovers thematic links to a trickster, Jakamarra, central to the jukurrpa storyline at Jipiranpa.

Chapter 7 unpacks the details of reduplication in a song set sung by Warlpiri women in Willowra, a Warlpiri region with many Kaytetye language influences. Through detailed examples of the Warnajarra verses recorded by Morais over 40 years ago, and more recently documented by the authors in 2019, they illustrate how the use of reduplication is associated with a particular faster syncopated meter, which relates to particular Warnajarra sites. In contrast, a slower rubato meter in which other verses are sung seems to relate more to other jukurrpa. This case study elegantly illustrates how rhythm and tempo encode the essence of the ancestors, furthering Catherine Ellis’s observations of the representation of particular Ancestral Beings in melodies.

Chapters 8, 9 and 10 turn to Warlpiri efforts to ensure that ceremonial songs maintain their purpose and function against shifting social contexts. Chapter 8 addresses the attempt to reanimate the songs associated with the Ngajakula ceremony by involving the community in mapping the long songline to give the songline new relevance. The past role of the Ngajakula and related Jardiwanpa revolved around the resolution of conflict, but current emphasis is on it reinforcing connections to particular Warlpiri jukurrpa and sites and the shared Law of all Warlpiri across a broad region. This gives the songs significance without the ceremony, which may or may not be revived with a new focus of celebrating interconnectedness between Countries.

Chapter 9 concerns the most successful repurposing of both songs and ceremony. It is a classic study of how one group of Warlpiri women, among the first in the early 1980s, took their yawulyu songs and dance to southern Australia for the opening of exhibitions and meetings. It follows the travels of a group of Warlpiri people from Yuendumu to Adelaide to perform the Warlukurlangu yawulyu. Importantly, it presents the motivation of the ritual leaders, Dolly Nampijinpa Daniels/Granites and Judy Nampijinpa Granites, via discussion of their negotiations around the choices of performances, and recognises the rewards of travel and compensation.

The final chapter addresses the radical transformation of ceremony into theatre. It describes an entirely new musical performance of the Milpirri at Lajamanu, examining whether this follows a traditional form and can, therefore, be called a purlapa – or whether it is a quite new form and a festival. Milpirri is an emergent event that has been held biannually in Lajamanu since 2005 and which is intended to provide a platform for the rejuvenation of specific forms of song and dance, including from men’s purlapa and women’s yawulyu, joining these with choreographed hip-hop primarily performed by children from the school. The authors show the influences from Ancestral ritual genres, from the church and from the emergence of popular reggae and rock bands, and how these have been integrated with the assistance of Tracks Dance Company from Darwin working closely with Artistic Director Wanta Jampijinpa Patrick and other community members. This event marks the complete transformation from ceremonies motivated by traditional purposes, replacing them with a theatrical event with contemporary motivations and purposes.

References

Barwick, Linda, Mary Laughren and Myfany Turpin. 2013. “Sustaining Women’s Yawulyu/Awelye: Some Practitioners’ and Learners’ Perspectives”. Musicology Australia 35(2): 191–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2013.844491

Biddle, Jennifer. 2019. “Milpirri: Activating the At-Risk”. In Energies in the Arts, edited by Douglas Kahn, 351–371. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bracknell, Clint and Kim Scott. 2019. “Ever-Widening Circles: Consolidating and Enhancing Wirlomin Noongar Archival Material in the Community”. In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, edited by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 325–38. Honolulu; Sydney: University of Hawai‘i Press and Sydney University Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2011. “The ‘expanding domain’ of Warlpiri initiation rituals”. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Peterson, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber, 39–50. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2020. Sustaining Indigenous Songs. New York: Berghahn.

Curran, Georgia and Françoise Dussart. 2023. “‘We Don’t Show our Women’s Breasts for Nothing’: Shifting Purposes for Warlpiri Women’s Public Rituals –Yawulyu – Central Australia – 1980s–2010s”. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. https://doi.org/10.1177/00084298231154430

Curran, Georgia and Otto Sims. 2021. “Performing Purlapa: Project Warlpiri Identity in a Globalised World”. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 22(2–3): 203–19.

Curran, Georgia and Calista Yeoh. 2021. “‘That is Why I Am Telling This Story’: Musical Analysis as Insight into the Transmission of Knowledge and Performance Practice of a Wapurtarli Song by Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu, Central Australia”. Yearbook for Traditional Music 53: 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/ytm.2021.4

Curran, Georgia, Simon Japangardi Fisher and Linda Barwick. 2018. “Engaging with Archived Warlpiri Songs”. In Communities in Control: Learning Tools and Strategies for Multilingual Endangered Language Communities – Proceedings of FEL XXI Alcanena 2017, edited by Nicholas Ostler, Vera Ferreira and Chris Moseley, 167–74. Hungerford: Foundation for Endangered Languages. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/20389

Curran, Georgia, Linda Barwick, Myfany Turpin, Fiona Walsh and Mary Laughren. 2019. “Central Australian Aboriginal Songs and Biocultural Knowledge: Evidence from Women’s Ceremonies Relating to Edible Seeds”. Journal of Ethnobiology 39(3): 354–70. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-39.3.354

Dussart, Françoise. 2000. The Politics of Ritual in an Aboriginal Settlement: Kinship, Gender and the Currency of Knowledge. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Dussart, Françoise. 2004. “Shown but Not Shared, Presented but Not Proferred”. The Australian Journal of Anthropology 15(3): 253–66.

Ellis, Catherine. 1985. Aboriginal Music, Education for Living: Cross-cultural Experiences from South Australia. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Grant, Catherine. 2014. Music Endangerment: How Language Maintenance Can Help. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hale, Kenneth. 1984. “Remarks on Creativity in Aboriginal Verse”. In Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, edited by Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington, 254–62. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Kolig, Erich. 1981. The Silent Revolution: The Effects of Modernisation on Australian Aboriginal Religion. Philadelphia: The Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

Laughren, Mary. 1981. Religious Movements at Yuendumu 1975–1981. Canberra: Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies.

Marett, Allan. 1994. “Wangga: Socially Powerful Songs?” The World of Music 36: 67–81.

Marett, Allan, Mandawuy Yunupiŋu, Marcia Langton, Neparrnga Gumbula, Linda Barwick and Aaron Corn. 2006. “The National Recording Project for Indigenous Performance in Australia: Year One in Review.” In Backing Our Creativity: The National Education and the Arts Symposium, 12–14 September 2005, 84–90. Surry Hills: Australia Council for the Arts. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/1337

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1962. Desert People. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Merlan, Francesca. 1987. “Catfish and Alligator: Totemic Songs of the Western Roper River, Northern Territory”. In Songs of Aboriginal Australia (Oceania Monograph 32), edited by Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Wild, 142–67. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Moyle, Alice. 1974. North Australian Music: A Taxonomic Approach to the Study of Aboriginal Song Performances. PhD thesis, Monash University, Melbourne.

Myers, Fred. 1986. Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self: Sentiment, Place, and Politics Among Western Desert Aborigines. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Nettl, Bruno. 2013. “Relating the Present to the Past: Thoughts on the Study of Musical Change in Ethnomusicology”. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:221935861

Peterson, Nicolas. 2000. “An Expanding Aboriginal Domain: Mobility and the Initiation Journey”. Oceania 70(3): 205–18.

Peterson, Nicolas. 2008. “Just Humming: The Consequences of the Decline of Learning Contexts among the Warlpiri”. In Cultural Styles of Knowledge Transmission: Essays in Honour of Ad Borsboom, edited by J. Kommers and Eric Venbrux, 114–18. Amsterdam: Askant.

Schippers, Huib and Catherine Grant. 2016. Sustainable Futures for Music Cultures: An Ecological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sutton, Peter. 1987. “Mystery and Change”. In Songs of Aboriginal Australia, edited by Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Wild, 177–96. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Treloyn, Sally. 2017. “Singing with a Distinctive Voice: Comparative Musical Analysis and the Central Australia Musical Style in the Kimberley”. In A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes, edited by Kristy Gillespie, Sally Treloyn and Don Niles, 147–69. Canberra: ANU Press.

Treloyn, Sally and Rona Googninda Charles. 2015. “Repatriation and Innovation: The Impact of Archival Recordings on Endangered Dance-Song Traditions and Ethnomusicological Research”. In Research, Records and Responsibility: Ten Years of PARADISEC, edited by Linda Barwick, Nicholas Thieberger and Amanda Harris, 187–205. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Treloyn, Sally and Rona Goonginda Charles. 2021. “Music Endangerment, Repatriation, and Intercultural Collaboration in an Australian Discomfort Zone”. In Transforming Ethnomusicology Volume II, edited by Beverley Diamond and Salwa El Castelo Branco, 133–147. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197517550.003.0009

Treloyn, Sally, Matthew Dembal Martin and Rona Googninda Charles. 2016. “Cultural Precedents for the Repatriation of Legacy Song Records to Communities of Origin”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 94–103.

Turpin, Myfany and Mary Laughren. 2013. “Edge Effects in Warlpiri Yawulyu Songs: Resyllabification, Epenthesis, Final Vowel Modification”. Australia Journal of Linguistics 33(4): 399–425.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2021. “What is Intangible Cultural Heritage?” https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003

Vaarzon-Morel, Petronella, Linda Barwick and Jennifer Green. 2021. “Sharing and Storing Digital Cultural Records in Central Australia”. New Media & Society 23(4): 692–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820954201

Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Georgia Curran. 2017. Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu [including DVD]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Wild, Stephen. 1981. Contemporary Aboriginal Religious Movements of the Western Desert (Lajamanu). Canberra: Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies.

Wild, Stephen. 1987. “Recreating the Jukurrpa: Adaptation and Innovation of Songs and Ceremonies in Warlpiri Society”. In Songs of Aboriginal Australia (Oceania Monograph 32), edited by Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen A. Wild, 97–120. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Young, Elspeth. 1981. Balgo Business in Yuendumu. Canberra: Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies.

Interviews

Granites, Lorraine Nungarrayi and Peggy Nampijinpa Brown. 2017. Interview by Valerie Napaljarri Martin, recorded by Georgia Curran, 8 April 2017. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Granites, Rex Japanangka. 2017. Interviewed by Simon Japangardi Fisher, recorded by Georgia Curran and Linda Barwick, 25 May 2017. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Henwood, Alice Nampijinpa. 2018. Interviewed by Valerie Napaljarri Martin, recorded by Georgia Curran and Linda Barwick, 15 May 2018. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Nelson, Harry Jakamarra and Otto Jungarrayi Sims. 2018. Interviewed by Valerie Napaljarri Martin, recorded by Georgia Curran and Linda Barwick, 10 May 2018. Yuendumu: PAW Media and Communications.

Rex Japanangka Granites (c.1948–2019)

Japanangka was born around 1949 and grew up in many different areas, including Yuendumu, the Granites and Lajamanu. He did his early schooling in Lajamanu and then moved to Yuendumu. He was one of the first groups of young blokes to go back to school after going through the Law. He remembers that in the mid-1960s, he would stay in the Munga business camp at night and then go to school in the morning. He also went through Kankarlu in the 1970s. He became a bilingual teacher at Yuendumu School in the 1970s, was Chairman of the Central Land Council in the 1990s and worked as an artist and in mediation and pastoring in his later years (see Granites 2009). Japanangka was kirda for Minamina jukurrpa.

We have a lot of our old people and old ladies who are always there in those communities. When we growing up they’d look at us and see if we were suitable for ceremonies. And the fathers would look at them and then say “Yes, we’re ready for our young people to go through the Law.” Some of us, we are part of it. When we were teenagers we were frightened but that’s our Law and we go through it. We still do this today. Not just in one place, but in places where they originated from west to east following the Dreaming patterns.

We still sing and teach it. Not in a classroom but outside here. Outside where it’s open. The country is there. We sing about the country. Some of my family here are part of that country and we are kurdungurlu. Kurdungurlu is what we call the custodians – our mothers, our grandfathers – it’s the father’s side [kirda] that we look after.

Reference

Granites, Rex. 2009. What I am Part of [unpublished autobiography].

Harry Jakamarra Nelson (c.1944–2021)

Jakamarra was born at Mount Doreen Station as one of 12 children. He was kirda for the Country around Wapurtarli, close to the station area. When he was a child, his family moved into Yuendumu so that the children could attend school, and they became close to the Fleming family, who served as missionaries over many decades. He had a key role as an educator in the early years of the Yuendumu School’s bilingual education program. From a young age, Jakamarra acted as a cultural broker for his community’s engagements with visitors. He famously spoke at the National Aborigines Day in Martin Place in 1963 at the young age of 19. He was a passionate advocate for Warlpiri land rights and self-determination over many decades, including as a spokesperson against the Northern Territory (NT) Intervention and the prior amalgamation of councils in the NT. Jakamarra was the driving force in the establishment of the Yuendumu Men’s Museum built in the 1960s and its reopening as a refurbished museum in 2015. He was a leader (watirirririrri) for the annual ceremonies held over summer in Yuendumu and regularly travelled across a broad region of the Central Desert to assist other communities with their ceremonial activity. Jakamarra was involved in the production of Yarripiri’s Journey (Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications), which documented the Jardiwanpa songline for which he was responsible. Jakamarra sadly passed away in February 2021.

Ngajuju karna nyinami ngulaju ngampurrpa-nyayirni yungulu juju-mani kajili nyanyi ngakalku kajirlipa ngalipa lawa-jarrimirra. Ngaju kajirna lawa-jarrimirra, yungulu palka nyanyi ngaju-kurlu kujajulu record-manu nyampu jukurrpa like jardiwanpa-kurlu might be kurdiji-kirli-rlangu kujarra, ngakalku yungulu nyanyi, that’s ngurrju no tikirliyi.

I want them [young people] to learn, to see and listen, when we all pass away. When I pass away I want people to still see my photos, and Jardiwanpa and Kurdiji, all those kind of things – I want them to see them later on. That’s good, not to be restricted.

Warlpiri-patu nyurrurlarlu, yungunpalu-jana purda-nyanyi warringiyi- puraji-patu ngamirni-puraji-patu manu wantirri-puraji-patu, jamirdi-puraji-patu kujarralku. Aunty-nyanu too, mardukuja-paturlu, pimirdi-nyanu purda-nyangka, yaparla-nyanu kujarra walirra, yunkulu-jana purda-nyanyi yunparninja-karra law ngalipa-nyangu jukurrpa Warlpiri-kirlangu.

You Warlpiri young people, I am talking to you today, so you can listen to your grandfathers and your uncles singing. Women can listen to their aunties’ and their grandmothers’ songs. This is our law, Warlpiri law.

Otto Jungarrayi Sims (c.1960)

Jungarrayi was born and grew up in Yuendumu and Nyirrpi. He is kurdungurlu for the Country around Wapurtarli (Mount Singleton, see profile photo). Following in the footsteps of both his father, Paddy Japaljarri Sims, and his mother, Bessie Nakamarra Sims, Jungarrayi is an internationally acclaimed artist. He works tirelessly as an advocate for Warlpiri culture to ensure that his cultural traditions remain strong into the future. Jungarrayi is the chairperson for Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation.

Yuwayi jalangu karna wangkami jalangu-warnu-patuku. Japikalu-jana jarlu-patu yungulu-nyarra pina-yirrarni, manu yantalu PAW-kurra, nyangkalu yardiwajirla nyarrpalpalu nyinaja jarlupatu ngulalpalu yunparnu, jukurrpa ngulalpalu mardarnu, parnpa juju ngulalpalu mardarnu wirijarlu. Yungunkulu nyurrurlarlulku mardarni pirrjirdirli, tarnngangku-juku yungunkulu mardarni rdukurdukurla, pirlirrpa yungu-nyarra pirrjirdi mardarni. Ngulalpalu jarlu-patu nyinaja pirrjirdi, yungunkulu nyurrurlarlulku mardarni, yuwayi.

Yes, I am speaking today to the young generations, ask your elders to teach you or go to PAW to watch videos. This is how people in the olden days used to live and participate in corroborees – they had big jukurrpa. So that you can keep it and carry it on in your hearts and spirits and to keep you strong, the way our ancestors were, they were strong, it’s your turn to keep it and to carry on.

Ngulangku kapungku mardarni, nyuntu-nyangu jukurrparlu kapungku mardarni pirrjirdi, yijardu-nyayirni kapunpa nyinami junga, nyiya-kujaku kajikanpa warntarlakari yani, jukurrpa ngula kajika warntarlakari yani kajikanpa wapakarra wapami. But jukurrpa nyuntu-nyangu kajinpa manngu-nyanyi, mardarni kirda-nyanu-kurlangu manu jamirdi-nyanu-kurlangu manu warringiyi-nyanu-kurlangu, kapunpa nyinami nyanungu-nyayirni pirrjirdi. Yuwayi, mardaninjaku palkarni, yungurlipa-jana, yungunkulu-jana nyurrurlarlulku pina-yirrarni yungulu mardarni nyampu, manulu yanta PAW kurra. Japikalu-jana warrkini-patu: “Yungurna nyanyi nyampu waja, nyarrpalpalu yunparnu jarlu-paturlu”.

That will keep you strong, your jukurrpa will keep you strong, keep it, that way you won’t lose it, as you won’t know what to do when you lose it. But if you keep your father and grandfather’s jukurrpa it will keep you really strong. Yes let’s look after our precious knowledge, so that you can keep on teaching and also go to PAW and ask the workers, “I want to see this, how the old people sang in their time.”

1 In some Aboriginal languages in Central Australia, the word for “taste” or “scent” is used to refer to this essence (Ellis 1985: 86).

2 Meggitt (1962, 209) and Dussart (2000) have also defined Warlpiri song genres and ceremonies with some slight differences to these categories. Curran (2020) also included a genre of men’s singing juyurdu “sorcery songs”, but these have been excluded here as they are no longer sung.