2

Archiving documentation of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies on-Country at the Warlpiri Media Archive

Archival materials are increasingly becoming a reference point for specialised cultural knowledge of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies. Many Warlpiri Elders are also keen to make further recordings and utilise those made in the past to ensure that there is a way for future generations to connect to and understand these highly valued aspects of their cultural heritage. In some instances, archival materials are being drawn upon to inform contemporary ceremonial spaces (Curran 2020b, 102–105; Curran and Yeoh 2021), and Warlpiri Elders, in particular, are developing an insatiable hunger for access to archival documentation to trigger their memories and reactivate the knowledge required to maintain songs. The late Harry Jakamarra Nelson, a widely respected Warlpiri Elder who was a prominent cultural broker from a young age, explained:

Nyurrurla-patuku young-pala-patuku karna-nyarra wangkamirra, nyampu yangka yardiwajikari-yardiwajikari nyangkayili, recording-li purda-nyangka jarlu-paturlu kajili yunparni, nyurruwiyi, kujalpalu yunparnu nyurruwiyi, recording-manulpalu. Yalili-jana payika. Kardiya-patulu-jana payika ngayi nyampurlaju PAW Warlpiri media. Warlpiri-patu nyurrurlarlu, yungunpalu-jana purda-nyanyi warringiyi-puraji-patu ngamirni-puraji-patu manu wantirri-puraji-patu, jamirdi-puraji-patu — kujarralku. Pimirdi-nyanu too, mardukuja-patu, pimirdi-nyanu purda-nyangka, yaparla-nyanu kujarra walirra. Yunkulu-jana purda-nyanyi yunparninja-karra law ngalipa-nyangu jukurrpa Warlpiri-kirlangu. Palka-jala ka ngunami kujalu-jana record-manu yawulyu-kurlu, parnpa-kurlu. Parnpa-wangu-kurlu yawulyu-wangu-kurlu different kujarra side ka karrimi. Mardukuja-kurlangu, wati-kirlangu kujaju ka karri, karna-nyarra warnkiri-mani.

I am telling the young people to sometimes go to watch the old videos and listen to the old recordings from the early days. Go and ask the workers there at PAW Media. You young Warlpiri people, I’m telling you now, so you can go and listen to your grandfathers and your uncles singing. Women can listen to their aunties’ (father’s sisters) and their grandmothers’ (father’s mothers) songs. This is our Warlpiri law. There is so much recorded from long ago, on both women’s and men’s sides. (Nelson and Sims 2018)

In the same ways that Warlpiri Elders facilitate access to deep knowledge of the Country and jukurrpa through their leadership roles in ceremonies and through telling songs and associated stories, they are increasingly using archival recordings to tap into this powerful knowledge of their ancestors from generations before them. Documentation through audiovisual recordings and photographs can ensure that these important and valued aspects of Warlpiri cultural heritage are available for future generations. Otto Jungarrayi Sims stated:

Ngurrparlipa jukurrpakuju but ngulangku nawu kangalpa mardarni ngula kalu yunparni, ngulangku kangalpa pirrjirdiji mardarni yungulu kurdu-warnu-paturlu mani ngukunyparla, nyampurla kajikalu mani marda kurdu-warnu-paturlu.

We [middle-aged generations] don’t know about the jukurrpa but those recordings on which old people sing can keep us strong and we need to learn from them and the young generations need to learn from them. (Nelson and Sims 2018)

With consideration of the cultural value of and increasing community interest in archival material, this chapter illustrates the importance of supporting community-based archiving practices and access to archival materials in Warlpiri communities. We begin with a historical overview of the many documentation projects conducted around Warlpiri song and ceremonial material, reaching back to the 1930s expeditions into Central Australia by the South Australian Board for Anthropological Research through to present-day efforts led by Warlpiri people to preserve, maintain and revitalise these valued components of Warlpiri cultural heritage. We then go on to discuss PAW Media (formerly Warlpiri Media Association), which has held a pivotal role since the early 1980s in producing Warlpiri-owned and Warlpiri-produced media of various forms, including significant ceremonial content that Warlpiri people have filmed over the last five decades. For Warlpiri people, having the Warlpiri Media Archive (WMA) located in Yuendumu is imperative for two reasons: this is the Country where songs and ceremonies come from and belong, and this is where the large majority of Warlpiri people live and they need to be able to access these repositories of cultural heritage materials. We conclude this chapter with an overview of several contemporary initiatives, including digital platforms, to make audiovisual media of songs and ceremonies more accessible for current generations of Warlpiri people.

Documentary history of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies

In the Indigenous Australian context, Warlpiri culture has received significant ethnographic attention and is one of the best documented desert cultures, being the focus of 15 books on various topics (Curran 2020a; Dussart 2000; Gallagher et al. 2014; Glowczewski 1991; Hinkson 2014; Kendon 1988; Meggitt 1962, 1966; Mountford 1968; Munn 1973; Musharbash 2008; Napaljarri and Cataldi 1994; Saethre 2013; Vaarzon-Morel 1995; Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017a;). There is also a large body of linguistic work, including an extensive encyclopaedic dictionary (Laughren et al. 2022) and a number of unpublished theses (Elias 2001; Wild 1975). Significant numbers of recordings have also been made of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies over the last 90 years, beginning with those made by Norman Tindale as far back as 1931 with Warlpiri men at Cockatoo Creek (just 30km to the north of present-day Yuendumu), well before the establishment of the government reserve in 1946.1 The Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) library catalogue lists collections of mostly audio but also some audiovisual materials deposited by 31 people (Barry Alpher, Murray Barrett, Linda Barwick, H. Basedow, Jennifer Biddle, L. Bursill, J. Capp, Lee Cataldi, Georgia Curran, Megan Dail-Jones, Yukihiro Doi, R. Edwards, A.P. Elkin, Barbara Glowczewski, M.K. Hansen, M.C. Hartwig, Sandra Brun Holmes, J. Horne, Mary Laughren, M.J. Murray, Laurie Reece, Kenneth Hale, R. Larson, Alice Moyle, Richard Moyle, David Nash, Nicolas Peterson, K. Pounsett, Les Sprague, Gertrude Stolz and Stephen Wild). AIATSIS also has copies of Warlpiri women’s yawulyu recorded at the Central Australia Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) in Alice Springs. Many independent scholars also hold significant collections of Warlpiri songs that they have recorded over many decades (significantly Françoise Dussart, Diane Bell, Jennifer Biddle and Myfany Turpin). More recently, Carmel O’Shannessy has recorded several Warlpiri song genres in Lajamanu, Myfany Turpin at Willowra and Jennifer Green at Ti-Tree (these are all archived in the Endangered Languages Archive).2

Despite the extent of these recordings, documentation on the details of songs and their associated content is minimal, and relatively little is written about this important component of Warlpiri cultural heritage. Françoise Dussart’s (2000) book sets out the social context for Warlpiri ceremonial life in Yuendumu in the 1980s, mentioning the kinds of song genres and performance contexts. Wild’s unpublished thesis (1975) and Curran’s book Sustaining Indigenous Songs (2020a), as well as two Warlpiri songbooks (Gallagher et al. 2014; Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017a), give details of Warlpiri song genres and performance contexts, alongside a number of journal articles and book chapters (Barwick and Turpin 2016; Barwick, Laughren and Turpin 2013; Curran 2010, 2011, 2013, 2017, 2018; Curran et al. 2019; Laughren et al. 2016; Turpin and Laughren 2013) and an audiovisual DVD (Laughren et al. 2010) and four-CD pack (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017b). This more recent work has produced detailed linguistic and musical transcriptions of these songs, bringing awareness to the value of the knowledge that they contain. However, the majority of the recordings of songs and ceremonies have little contextual documentation. The chapters in this book significantly add to their understanding, increasing the accessibility of these records for future generations by engaging present-day Warlpiri Elders and custodians in providing commentary and exegesis.

Beginnings of Warlpiri-led media production in Yuendumu: Warlpiri Media Association

PAW Media was formed in Yuendumu in 1983 as Warlpiri Media Association in response to advances in new media and communication technologies. Of particular importance was the announcement of the impending launch of the AUSSAT satellite in 1985, which would bring national television and radio programs to remote areas of Australia for the first time.3 A concern rose in Yuendumu, particularly among Elders, regarding the effects that imported television would have on their culture. Founding member Francis Jupurrurla Kelly remembered that:

[The old people] were worried about losing their culture and language and how they were going to teach young people with the satellite and everything pulling away the systems from their culture. In those times there weren’t even telephones for communications and all that. There was nothing and finally this satellite came along and people were talking about it. (Kelly 2013)

Another Warlpiri Media Association founder, the late Kurt Japanangka Granites, described the Warlpiri response to these technological advances:

When we started Warlpiri Media, we started taking our cameras and doing videos of the old people dancing and doing their culture. They were really happy and they wanted to show the world about our culture … From what we thought was the only way to get our message across … The media was coming in from outside and taking our stories outside which was not what we wanted. We wanted our stories to be told from our point of view, what we thought and were doing … And old people said, “Why can’t we have our own television in our language?” And without telling the government we went and did it ourselves – pirate television. We just did it for the community. (Granites 2013)

Kelly described this pirate television in more detail:

We were just putting VHS [tapes] in a little camera to take around to the communities because in that time they were all frightened of it. The television would go there, and they were shy. The people were shy to be on the television – they weren’t used to telling stories and all that and people were worried because they weren’t used to it. We were just sending out the signals to all the little communities – it only goes about 5–6 km around the communities just to watch it in black and white first. We did that and then the government found out that we were doing this for our communities and they decided to give us BRACS4 … Finally, we got this thing going and we made a formal committee and made Warlpiri Media as a representative of the communities. (Kelly 2013)

Figure 2.1 Paddy Sims, Paddy Stewart and Paddy Nelson watching television in the mid-1980s. Photo still from Satellite Dreaming (2016), courtesy of PAW Media.

A core group of senior men formed the Warlpiri Media Committee and drove the use of television and engagement with media in the early days (see Figure 2.1). Kelly explained that:

There were a couple of old people like Murray Wood. He was the first chairperson for Warlpiri Media. And we had Long Paddy Jakamarra and Jack Jakamarra Ross, Darby [Jampijinpa Ross], Paddy Stewart, Paddy Nelson and Paddy Sims – they were the strong people in that time … The money [for the televisions] came from the community themselves. On Friday, every pay day, [those] old men would sit at the shop and they used to talk “Chuck in for [a] television” and [people] used to chuck in $10, $20 of donations for the television so that people could see more. They were strong old people sitting there – they were the Elders in that group. (Kelly 2013)

Aboriginal activist and anthropologist Marcia Langton AO summarised the Warlpiri response to the new media in Yuendumu, highlighting that there was concern that:

a daily stream of imported programming would undervalue and limit local cultural traditions and control, whereas video production projects and exchange in the community reinforced certain cultural traditions. (1994, xxx)

During this time, when Warlpiri Media Association was being set up, the anthropologist Eric Michaels had been employed by the Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies (now AIATSIS) to conduct research on Warlpiri people’s engagement with new media (Michaels 1986, 1987). Michaels saw his research as an opportunity to support a shift in filmed representations of Warlpiri people; on his own accord rather than as part of his government job, he brought with him to Yuendumu video equipment for community use. This formed significant background for the beginnings of Warlpiri Media Association and its focus on Aboriginal-owned and Aboriginal-made productions for broadcast on radio and television.5 Langton explained that Michaels’ work “can be located in the middle of a local revolution: the empowerment of Aboriginal people in representations of them and by them” (Langton 1994, xxvii) and that it shows how “image production is another example of how Western technology and artefacts have been incorporated as part of Aboriginal customary law” (Langton 1994, xxxii). David Batty, who established the TV production unit at CAAMA and co-directed with Francis Jupurrurla Kelly the award-winning series Bush Mechanics, emphatically stated that:

The instrument [BRACS] we have in our hands is I think the most powerful instrument that Aboriginal people have ever been handed in terms of maintaining Aboriginal culture and languages. Ever. [emphasis in original] (Burum and Dowmunt 2016)

The Warlpiri Media Archive

Despite not being formally established until 2005, the WMA housed at PAW Media is one of the oldest and most extensive local archives in Aboriginal Australia, having operated as a keeping place for valuable audio and audiovisual materials since the beginnings of the organisation in the early-mid-1980s. Today it is well established, and further WMA productions and other donated materials are stored on hard drives in a climate-controlled room for conservation purposes and backed up on the PAW server. This archive holds collections of analogue video productions made by Warlpiri Media between 1983 and 2001, from which time their productions were shot digitally and were stored on their redundant array of independent disks (RAID) storage system. There are also over 1,000 tapes comprising Warlpiri Media Associations’ News presented by Warlpiri speakers, recorded ceremonies and films of Yuendumu School Country visits and Yuendumu Sports’ Weekends, as well as 13 episodes of the Warlpiri-language children’s Manyu Wana. The 400 most significant items in this archive are also duplicated at AIATSIS and the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, both in Canberra. For Warlpiri communities, this archive has immense social significance because it provides documentation of Warlpiri culture and history; it is particularly valued as it is on-Country, mediated by Warlpiri people and part of their living culture. Hinkson (2015), however, has told of the fragility of this system, emphasising the impact of inter-institutional and political pressures on Indigenous archiving projects. PAW Media has seen disaster in recent years with the collapse of their RAID server. Significant records were lost because there was no backup for the materials on this server and many of the originals were covered in dust. Due to the impediments to providing high-quality preservation in a remote, hot and dusty location, PAW Media is working through an ongoing digitisation process for its archive to strengthen its longevity and enable better cataloguing and user access.

Simon Japangardi Fisher, the senior archive manager at PAW Media, is responsible for ensuring that cultural protocols regarding deceased people and sensitive and restricted materials are adhered to, with Valerie Napaljarri Martin and Elizabeth Napaljarri Katakarinja overseeing the women’s materials. They all have an overview of materials in the archive and work with this collection, listening through the audio recordings, particularly to screen for content and produce a better cataloguing system. Fisher described his role as follows:

I am a Warlpiri researcher. I do a lot of archiving work, researching all my families. I’ve looked at a lot of collections at the libraries, at the museums and I work with various universities. The old people tell me what to do – the person that they trust is me. I’m [a] Warlpiri person who’s an Elder who has the two systems of knowledge – the kardiya philosophy and the yapa knowledge – I can be in both cultures.

My partner [Katakarinja] is also researcher and my boy [is interested] too. It was interesting last night, we were looking at old footage and he said to me “How can I do research?” This was the first time he asked me a question like this. He said how can I do research? I want to learn more about this knowledge. And I told him about how his grandfather was a tour guide for Norman Tindale in 1931 and 1932 onwards, when they went to Cockatoo Creek. But mostly that is all sensitive.

We have a Keeping Place in the other building. It’s more important because mostly this has been taken away by western anthropologists and we want it returned so we can start doing research. A lot of old people used to come along and say, “My father has been recorded by this anthropologist”. It is a bit sad [when we can’t find it] but some are returned. A lot of young people want to come with their USBs for recordings of their grandfather and grandmother. Even older people, they [sometimes] want to look at the sensitive stuff. Jampijinpa, Nic Peterson has done a lot of research around the Tanami with men. (Fisher and Curran 2021)

As put forth by Linda Barwick, the advent of digital archiving has meant that the traditional archives, which had previously dealt only with “collectors who typically travelled to remote places”, can now be replaced to “put the user/owner, not the institution, at the top of the model, and explore ways in which reciprocal relationships can, indeed must, be acknowledged and implemented” (Barwick 2004, 254). She explained that:

When there are effective and rapid communications between individuals and their community cultural centres on the one hand, and between the cultural centres and the digital archives on the other, it becomes practical to reassert the cultural authority of the home communities and individuals. The archive can then take on its most effective role in providing a service of managing, backing up, and providing access to data rather than having to assume the additional burden of administering the data it “owns” at arms’ length from the communities involved. (Barwick 2004, 256)

As a community organisation, PAW Media also plays an essential role in mediating and providing space for working through the inevitable dilemmas that arise from the reincorporation of old cultural materials back into present-day social worlds. Gibson has commented more broadly that “Indigenous peoples are increasingly making use of archival records to answer questions about cultural heritage” (Gibson 2020). It must also be noted that this can be an uncomfortable space as there may be questions around restricted or sensitive materials, questions around authority or gendered access to particular cultural knowledge, and uncertainty about the rapid shifts that are occurring around listening and viewing materials with images and voices of deceased people. Additionally, the form of knowledge management within archives with emphases on documentation, metadata, provenance and controls over access requires shifts to traditional Warlpiri forms of knowledge management, which emphasises strategic ambiguity as a way of managing access (see Michaels 1991).

PAW Media is supported by First Nations Media (formerly the Indigenous Remote Communications Association), who promote cultural management of the collections and provide training opportunities for local media workers, including around access platforms such as Keeping Culture, which is installed on the computers in the Warlpiri Research Space room at PAW Media. In 2020, PAW Media was also chosen as a pilot organisation to trial Mukurtu, another access platform to cultural materials. Their review concluded that “no single platform [is] able to meet the diverse archive needs in the First Nations community media sector” (First Nations Media 2020). Long-term and ongoing efforts by PAW Media workers to continue collaborating with archives and researchers aim to ensure the proper preservation, digitisation and documentation of cultural materials within an era of rapid technological advances. Fisher described some of his experiences:

I work with people at Sydney University and I’ve done a lot of research with Charles Darwin University. I did work with Ara Irititja, at the Strehlow Centre, NT Archives and Alice Springs library – I do a lot of research at these places. I’ve done repatriation too with the State Library and the Museum. I look at the protocols and intellectual property – I look through old photos, old slides, documents … all from various communities [across the western part of Central Australia]. I went to Portugal, to a conference on the other side of the world. This inspires me – collaborating with everybody like that. (Fisher and Curran 2021)6

“Vitality and Change in Warlpiri Songs” project (2016–2020)

In recent years, an Australian Research Council–funded Linkage project collaboration between the University of Sydney, Australian National University and PAW Media (of which this book is a product) has also seen the return of many large collections of song and ceremonial recordings that have previously only been held at AIATSIS or by individuals to the WMA, Warlpiri individuals and other community organisations. While many researchers, filmmakers and other people who have undertaken audiovisual recordings of Warlpiri songs and ceremonies have supplied community copies and regularly provide individuals with CDs, DVDs and USB sticks of these materials, the hot and dusty conditions and outdoor lifestyles of most Warlpiri people mean that these do not last long. Systematic organisation of these materials at a local repository like PAW Media is essential if Warlpiri people are to have long-term access to these legacy recordings.7 Further, we have shown that for proper repatriation of these cultural materials, support must be provided for activities that is led by knowledgeable Warlpiri people to appropriately engage relevant community members (see Curran 2020b). Some of the initiatives undertaken as part of the project are discussed below.

Murray Barrett’s recordings (1950s): Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

In March 2017, Simon Japangardi Fisher travelled to Canberra to visit AIATSIS and facilitated the return of digital versions of recordings made in the 1950s by Murray Barrett with people in Yuendumu. Barrett had regularly visited Yuendumu to provide dental care to residents throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Barrett recorded many hours of songs and stories, mostly with senior Warlpiri men, including Fisher’s grandfather, but also with some women and men who had only recently passed away.8 Engagement with these recordings has been led by Fisher, with Curran assisting with the women’s content (for further details, see Curran, Fisher and Barwick 2018). Many of the recordings captured “older” styles of song and dance, which contemporary Warlpiri people remember but no longer perform today.9

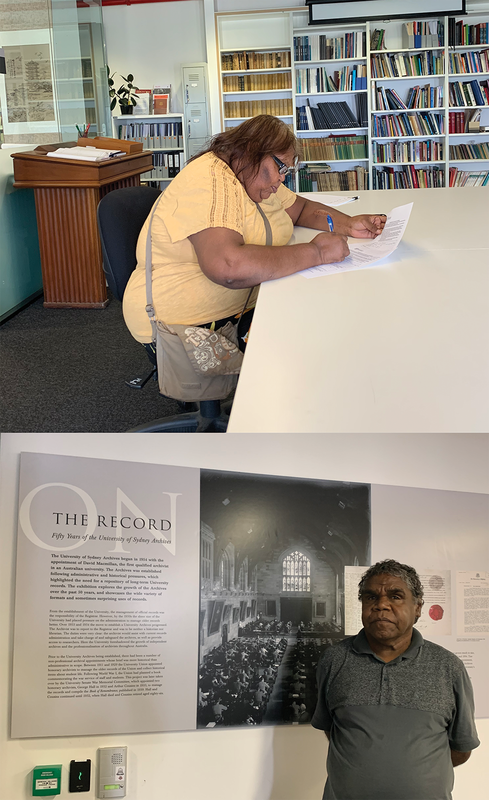

1953 Collections from Phillip Creek: University of Sydney Archives

In December 2019, Fisher and Katakarinja visited the University of Sydney Archives (see Figure 2.2); they now have community copies of many photographs and sound recordings taken by anthropologist A.P. Elkin in 1953 when visiting the settlement at Phillip Creek near Tennant Creek.10 Fisher has spent time separating those photos and recordings that are for men’s-only viewing. There is also some women’s content associated with Wakirti Warlpiri women from Alekarenge and Tennant Creek.11

Figure 2.2 Simon Japangardi Fisher and Elizabeth Napaljarri Katakarinja visit the Sydney University Archive, 2019. Photo by Georgia Curran.

Collections from the 1970s and 1980s: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

In March 2018, a group of 16 Warlpiri people travelled to AIATSIS and spent several days in male and female groups reviewing materials (see Figure 2.3). The listening rooms were filled with nostalgia and emotion as the groups reviewed recordings from many decades ago. This group delegation took back a hard drive of many large collections of audio recordings to WMA; this is now available for Warlpiri people, who have begun listening through these recordings and annotating their contents. Martin explained:

Figure 2.3 Warlpiri men and women visit the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in 2018 to review materials to return to the Warlpiri Media Archive. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Curran)

Ngularna yanu Canberra-kurra, maninjunurna hard-drives AIATSIS-jangka. Ngulajangkarna kangurnu PAW-kurra, yalumpu-juku ka nguna yardayarda-kurlu. Rdujupaturlu ngulalpalu nyurruwiyi-nyurruwiyi yunparnu, mardarnulpalu-nyanu. Ngulajangkaju kalalu-jana pina-pina-manu nyurruwiyiji yijardu-nyayirnirli. Jalangurluju yungulu generations to generation jalangu-warnu-paturlu pina-pina-mani nyanungurra-nyangu kurdu-kurdulku yungulu yani PAW-kurra-nyayirni, yungulu-nyanu milya-pinjarla mardarnilki warlalja nyanungu-nyangu kuruwarri manu jukurrpa manu nguru-nyanu. Nyarrpara-ngurlu yanurnu, nyarrpara-kurra yanu?

When I came back from Canberra, I brought hard drives from AIATSIS to PAW and it’s there. That’s sensitive materials for older women to see as well, and that was from a long time ago the old ladies used to sing and dance. In the hard drives there’s sensitive material, only the older women can have access to it. Our kids today can go to PAW and have access to the public material (not the forbidden ones). And they can see and keep it to themselves. Those stories and jukurrpa. Where did it come from, where did it go to? (Martin 2021)

Most of these song recordings are accompanied by sparse notes containing little more than a song genre, jukurrpa and the names of the singers. Song custodians have become more aware of these recordings and are now able to collectively maintain them. In bringing these recordings into the awareness of the contemporary generation of song custodians, an overview of their contents has begun to be maintained collectively. There are many songs that were long forgotten and many that linked closely to the identities of particular Warlpiri people and families. This documentation process has made it possible to extract clips from these recordings for family use; for example, the kanta (“bush coconut”) yawulyu songs sung on a recording by Stephen Wild in 1973 were listened to by Lynette Nampijinpa Granites and other female singers in 2021 prior to the initiation ceremonies of related boys.

Carrumbo: Film by Victor Carell

During this same trip to AIATSIS, music historian Amanda Harris facilitated a viewing session for senior Warlpiri men Harry Jakamarra Nelson, Rex Japanangka Granites and Otto Jungarrayi Sims of the film Carrumbo, made by Victor Carell in the 1950s and including footage of a restricted men’s ceremony. These men identified the restricted parts of this film and those that were open for public viewing. In collaboration with Fisher, Harris then produced an edited (unrestricted) version of the film and deposited both restricted and unrestricted versions with PAW Media in Yuendumu for use and viewing by relevant community (see Harris 2020, 180). This remains some of the oldest video footage of Warlpiri people in existence.12

Warlpiri Women’s Law and Culture meetings (1990s): Anne Mosey’s collection

While the group from Yuendumu was visiting AIATSIS in March 2018, former Yuendumu Women’s Centre coordinator Anne Mosey also joined the group for several days. Mosey had a collection of video materials that she had filmed during the 1990s alongside Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites (now a senior yawulyu singer in Yuendumu, but then a young woman) when she worked in Yuendumu. At the time, led by powerful female singers, in particular Dolly Nampijinpa (Daniels) Granites (see Chapter 9), the Yuendumu Women’s Centre’s main purpose was to raise funds to support travel for a group of women to attend business meetings across the western side of the Tanami Desert and beyond into the Kimberley. The videos made during these trips capture many of the yawulyu, which women from Yuendumu shared during these large ceremonial gatherings. Edited versions of these videos have now been created and are regularly played during screening evenings at women’s dance camps (see Figure 2.4), as well as being in popular demand at the Yuendumu Women’s Centre and Old People’s Program.13

Figure 2.4 Warlpiri women viewing videos made during Women’s Law and Culture meetings in the 1990s at a dance camp at Bean Tree outstation in August 2019. Photo by Georgia Curran.

Digital spaces for Warlpiri songs and cultural continuity

In response to the increasing desire of people in Yuendumu and other Warlpiri communities to have better access to archival materials, a 2018–2020 project has seen the development of a password-protected website space through which archival audio and audiovisual materials, as well as photograph collections, can be viewed (see Figure 2.5). This website space is devoted specifically to materials on Warlpiri songs and ceremonies that are open for public viewing; at the time of writing, it contains only Warlpiri women’s materials. The website also hosts additional educational resources, including lyric videos designed for learning women’s yawulyu, created through collaborations with Warlpiri transcribers and senior owners and managers of the songs.14 Offline accessibility of the website is important, and the use of a Raspberry Pi server is being developed so that Warlpiri families who do not have internet access in Yuendumu can access the website materials and resources.15 This will also mean that people can access these archival materials during family camp-out events, including the Yuendumu School’s “Country visits” and the biannual dance camps held by Warlpiri women in outstations across the Tanami Desert.16 Enid Nangala Gallagher, who has been central to the co-design of the website, commented:

Figure 2.5 Trish Lechleitner and Ruth Napaljarri Oldfield view old photographs on an iPad at a dance camp at Bean Tree outstation in 2019. Photo by Georgia Curran.

This is more than a space to store old recordings and photographs, it is a way for past and present generations to engage together in teaching and learning of songs, dances and designs into the future.

Singers and dancers produce and maintain digital technology from this community base in Yuendumu to continue to pass on their cultural knowledge to future generations and share elements with a broader world.

Fisher commented on the digital literacy of younger generations of Warlpiri people:

These younger generations … they know how digital things work. A lot of young people want to record in language, their music – reggae, gospel, making radio documentaries – young people are really interested, they’ve got facebook, instagram, twitter, they get carried away. They are recording new things and some want [to access] sensitive stuff which is not shown in public but is used to teach younger generations. I take them to the archives into the special room and look at it. A lot of people come, even older people, and they say, “Can you record [give me copies of] me?” We get a hard drive and record [copy] their stuff. (Fisher and Curran 2021)

For the future: “They can listen to the voices of the old people”

The role of archives and cultural organisations in this space is complicated, and access to archival materials is certainly not without dilemmas. However, Warlpiri interest in accessing, managing and learning from archival materials is continuously increasing. In Martin’s words:

Nyampu ngulakarlipa mardarni PAW-rla kuruwarri-kirli manu jukurrpa-kurlu. Marda kuurlu-jangka yungulu yanirra yinya-kurraju. Ngurrju-nyayirni karlipa mardarni PAW-rla (archiving). It’s really important ngalipa-nyanguku kurdu-kurduku jalangu-warnu-patuku. Yungulu-jana pina-pina-mani nganungurra-nyangu kurdu-kurdulku yangka kamparrurlu.

It’s good that here at PAW we got our own archives with stories and Dreamings, so the kids from the school will have access to it. And it’s really important that our kids today get to know this so that they can teach their own kids in the future.

Martin continues:

Yinyarla PAW-rlaju, archive-rlaju nyanungurra-nyangu warlalja. Yungulu milya-pinyi, ngana-kurlangu? Nyarrpara-jangka, which family-jangka? Kuja. Ngana-kurlangu family ngajuju? Kuja. Kujarraku yungulu nyanyi PAW-rlaju, archive-rlaju. Yungulu yinjani jalangu-warnu-paturlu (generations to generations). Yungulu-nyanu milya-pinyi, nyarrpara-jangka family-jangka? Yungulu mardarni junga-nyayirnirli warlalja.

So that at PAW they can see and learn at the archive their own stories and Dreamings. Who does it belong to, which family? That one. Which family, that one. So they can see for themselves at PAW, at the archive, who it belongs to. So that they can know, generation to generation. To know for themselves which family they are from. So they can keep knowing their own stories and Dreamings. (Martin 2021)

Nelson reflected in 2018 on the values of archival recordings for future generations and the kinds of ways in which Elders can facilitate engagement with younger generations, who may not have learned about these songs and ceremonies in the traditional ways. In the following statement, he gives a kind of permission to future generations, encouraging them to access archives, engage with them and recognise that these legacy materials are part of their identity that is passed down to them as Warlpiri people:17

Kurdu-kurduku kajili-jana jiily-ngarrirni, kajilpalu-jana yirrakarla video picture-rlangu marda, kurdu-kurdu kajikalu nyina and purlka-patu there jirrama marda three-pala marda, four-pala marda. Ngulangku kajika-jana ngarrirni jukurrpa-wati nyampu waja yirdi nyampu waja, nyampuju jukurrpa so and so. Ngajuju karna nyinami ngulaju ngampurrpa-nyayirni yungulu juju mani kajili nyanyi ngakalku kajirlipa ngalipa lawa-jarrimirra. Ngaju kajirna lawa-jarrimirra, yungulu palka nyanyi ngaju-kurlu kujajulu record-manu nyampu jukurrpa like jardiwanpa-kurlu, might be kurdiji-kirli-rlangu, kujarra, ngakalku yungulu nyanyi, that’s ngurrju no tikirliyi. Linpa nyampu purda-nyanjaku, purda-nyanjaku.

The Elders, maybe two, three or four of them, might sit with the young generations and look through the videos and the photos. They will then tell them the names of the jukurrpa and who it belongs to. I am keen for them to learn, to see and listen. By the time when we all pass away, when I pass away I want people to still see my photos, and the Jardiwanpa and the Kurdiji,18 all those kind of things, they can see later on, that’s good. They can listen to the voices of the old people. (Nelson and Sims 2018)19

References

Barwick, Linda. 2004. “Turning it All Upside Down? Imagining a Distributed Digital Audiovisual Archive”. Literary & Linguistic Computing 19(3): 253–63.

Barwick, Linda and Myfany Turpin. 2016. “Central Australian Women’s Traditional Songs: Keeping Yawulyu/Awelye Strong”. In Sustainable Futures for Music Cultures: An Ecological Perspective, edited by Huib Shippers and Catherine Grant, 111–44. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barwick, Linda, Mary Laughren and Myfany Turpin. 2013. “Sustaining Women’s Yawulyu/Awelye: Some Practitioners’ and Learners’ Perspectives”. Musicology Australia 35(2): 1–30.

Burum, Ivo, dir, prod, and Tony Dowmunt, prod. 2016. Satellite Dreaming: The History of Indigenous Television Production and Broadcasting [The CAAMA Collection]. Ronin Films.

Curran, Georgia. 2010. “Linguistic Imagery in Warlpiri Songs: Some Examples from Minamina Yawulyu”. The Australian Journal of Linguistics 30(1): 105–15.

Curran, Georgia. 2011. “The ‘Expanding Domain’ of Warlpiri Initiation Ceremonies. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Peterson, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber, 39–50. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2013. “The Dynamics of Collaborative Research Relationships: Examples from the Warlpiri Songlines Project”. Collaborative Anthropologies 6: 353–72.

Curran, Georgia. 2017. “Warlpiri Ritual Contexts as Imaginative Spaces for Exploring Traditional Gender Roles”. In A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes, edited by Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn and Don Niles, 73–88. Canberra: ANU Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2018. “On the Poetic Imagery of Smoke in Warlpiri Songs”. Anthropological Forum 28(2): 183–96.

Curran, Georgia. 2020a. Sustaining Indigenous Australian Songs. New York: Berghahn Books.

Curran, Georgia. 2020b. “Incorporating Archival Cultural Heritage Materials into Contemporary Warlpiri Women’s Yawulyu Spaces”. In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, edited by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 91–110. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Curran, Georgia and Otto Sims. 2021. “Performing Purlapa: Projecting Warlpiri Identity in a Globalised World”. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 22(2): 203–19.

Curran, Georgia and Calista Yeoh. 2021. “‘That Is Why I Am Telling This Story’: Musical Analysis as Insights into the Transmission of Knowledge and Performance Practice of a Wapurtarli Song by Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu, Central Australia”. Yearbook for Traditional Music 53: 45–70.

Curran, Georgia, Simon Japangardi Fisher and Linda Barwick. 2018. “Engaging with Archived Warlpiri Songs”. In Communities in Control, FEL XXI Alcanena 2017, edited by Nicholas Ostler, Vera Ferreira and Chris Moseley, 167–74. Hungerford: Foundation for Endangered Languages.

Curran, Georgia, Barbara Napanangka Martin and Margaret Carew. 2019. “Representations of Indigenous Cultural Property in Collaborative Publishing Projects: The Warlpiri Women’s Yawulyu Songbooks”. Journal of Intercultural Studies 40(1): 68–84.

Dussart, Françoise. 2000. The Politics of Ritual in an Aboriginal Settlement. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Elias, Derek. 2001. Golden Dreams: Place and Mining in the Tanami Desert, PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra.

First Nations Media. 2020. “Archive Platform Project 2019–2020”. Accessed 1 July 2021. https://firstnationsmedia.org.au/projects/archiving-project/archive-platform-project-2019-20

Fisher, Simon Japangardi and Georgia Curran. 2021. “Country Doesn’t Change”. Presentation at PARADISEC@100 conference, 17–19 February 2021. Sydney: University of Sydney. https://youtu.be/cQCGFipzJbQ?list=PLP7ZXIu_hereTOj-lRBF7frTUT-v2PbX6

Gallagher, Coral, Peggy Brown, Georgia Curran and Barbara Martin. 2014. Jardiwanpa Yawulyu. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Gibson, Jason. 2020. Ceremony Men: Making Ethnography and the Return of the Strehlow Collection. New York: State University of New York Press.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 1991. Du rêve à la loi chez les Aborigènes. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Harris, Amanda. 2020. Representing Australian Aboriginal Music and Dance 1930–1970. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Hinkson, Melinda. 2002. “New Media Projects at Yuendumu: Inter-Cultural Engagement and Self-Determination in an Era of Accelerated Globalization”. Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 16(2): 201–20.

Hinkson, Melinda. 2014. Remembering the Future. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Hinkson, Melinda. 2015. “Pictures that move: Two tales from the Warlpiri archives”. Paper presented at the Image, Music, Text symposium, University of Sydney, 20 March 2015.

Kendon, Adam. 1988. Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Langton, Marcia. 1994. “Introduction”. In Bad Aboriginal Art, edited by Eric Michaels, xvii–xliii. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Laughren, Mary, Myfany Turpin and Helen Morton. 2010. Yawulyu Wirliyajarrayi-wardingki: ngatijirri, ngapa. (Willowra songlines: Budgerigar and rain) [DVD]. Willowra: Willowra community.

Laughren, Mary, Georgia Curran, Myfany Turpin and Nicholas Peterson. 2016. “Women’s Yawulyu Songs as Evidence of Connections to and Knowledge of Land: The Jardiwanpa”. In Language, Land and Song: Studies in Honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch and Jane Simpson, 425–55. London: EL Publishing.

Laughren, Mary, Kenneth Hale, Jeannie Egan Nungarrayi, Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1962. Desert People. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1966. The Gadjari Among the Warlpiri Aborigines of Central Australia (Oceania Monograph 14). Sydney: University of Sydney.

Michaels, Eric. 1986. The Aboriginal Invention of Television: Central Australia 1982–86. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Michaels, Eric. 1987. For a Cultural Future: Francis Jupurrurla Makes TV at Yuendumu. Sydney: Art & Text.

Michaels, Eric (ed.). 1991. Bad Aboriginal Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mountford, Charles P. 1968. Winbaraku and the Myth of Jarapiri. Adelaide: Rigby.

Munn, Nancy. 1973. Warlbiri Iconography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Musharbash, Yasmine. 2008. Yuendumu Everyday. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Napaljarri, Peggy Rockman and Lee Cataldi. 1994. Yimikirli: Warlpiri Dreamings and Histories. San Francisco: Harper Collins.

O’Keeffe, Isabel, Georgia Curran, Jodie Kell, Linda Barwick, Ruth Singer, Simon Japangardi Fisher, Elizabeth Napaljarri Katakarinja, Jenny Manmurulu and Sandra Makurlngu. Forthcoming 2023. “Endangered Languages or Endangered Multilingual Ecologies? Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Perspectives from communities in Arnhem Land and Central Australia”. In Teaching and Learning Resources for Endangered Languages, edited by Jakelin Troy, Mujahid Torwali and Nicholas Olster. Leiden: Brill.

Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Media and Warlpiri Media Association. 1995. Fight Fire with Fire. Ernabella and Yuendumu: Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Media and Warlpiri Media Association.

Saethre, Eirik. 2013. Illness is a Weapon: Indigenous Identity and Enduring Afflictions. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Turpin, Myfany and Mary Laughren. 2013. “Edge Effects in Warlpiri Yawulyu Songs: Resyllabification, Epenthesis and Final Vowel Modification”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 33(4): 399–425.

Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Georgia Curran (eds). 2017a. Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu [including DVD]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Georgia Curran (eds). 2017b. Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu [4-CD set]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Wild, Stephen. 1975. Warlbiri Music and Dance. PhD thesis, University of Indiana, Bloomington.

Vaarzon-Morel, Petronella (ed.). 1995. Warlpiri Women’s Voices. Alice Springs: Institute for Aboriginal Development.

Venner, Mary. 1988. “Broadcasting for Remote Aboriginal Communities Scheme”. Media Information Australia 47(1): 37–43.

Interviews

Granites, Kurt Japanangka. 2013. Interviewed by Denis Charles. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Kelly, Francis. 2013. Interviewed on 23 September 2013 for the “30 Year Anniversary of Warlpiri Media Association”. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Martin, Valerie Napaljarri. 2021. Interviewed by Georgia Curran, 21 May 2021. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Nelson, Harry Jakamarra and Otto Jungarrayi Sims. 2018. Interviewed by Valerie Napaljarri Martin, recorded by Georgia Curran and Linda Barwick, 10 May 2018. Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Alice Nampijinpa Henwood (c.1945)

Nampijinpa was born at Mount Doreen Station, a cattle station to the west of Yuendumu, where her father worked as a stockman. During her early childhood, she learned to find food in the surrounding bush. When her family was moved to Yuendumu after World War II, Nampijinpa spent her childhood attending missionary school. When she was married to her promised husband, she moved southwards to Haasts Bluff, where she had her first child. She then returned to Yuendumu and had three more children. In 1983, following the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act of 1976, she moved back to traditional lands in Nyirrpi and Emu Bore, where she has lived ever since. Nampijinpa is a senior singer and kirda for the Ngapa (Rain) jukurrpa, which travels along the south side of Yuendumu. She currently works for the Southern Tanami Rangers and is involved in species rehabilitation and teaching biocultural knowledge to younger generations.

Ngajuju kalarna-jana nyangu wirntinja-kurraju panu-jarlu and jalangu-jalanguju ngulaju wirntimi kiyini karnalu. Yuwayi ngajurna learn-jarrija-jala that’s why karna yunparni yangka jalpi-rlangurlu yuwayi. Yunparninjarla yangka wirntimi karna, panu-jarlu yangka karna-jana teachji-mani you know wirntinjaku even wiri-wiri-rlangu yangka.

I saw lots of dancing in the old days, and still today we dance. I learned all these a long time ago, that’s why I can sing all the songs today – like on my own. I sing and dance, I teach a lot of girls to dance. I even teach the older women to dance.

Kalalu wirntija panujarlu-jala, wali yangka jalangu-jalanguju yangka karlipa marnkurrpa-karrikarrilki wirntimi. Yuwayi, kalalu yirrarnu, puul-yirrarnu yangka panungku-wiyi yangkaju jalangu-jalangu lil bit-lki yangka yukanti-yukantilki, yukanti-karrikarrilki yangka.

In the olden days, lots of people joined in for the dancing and the singing, but now only a few people participate in dances. Yes, they sang together, they were big mobs, and today only a few songs are sung.

Paddy Japaljarri Sims (c.1931–2010)

Japaljarri was born at Kunajarrayi (Mount Nick). Japaljarri was kirda for Yiwarra (Milky Way), Ngarlkirdi/Warna (witchetty grub/snake), Warlu Kukurrpa (fire) and Yanjirlpirri (star). He grew up on his traditional lands until he was a young man. All his life, he hunted for goannas, kangaroos, emus and other bush tucker; he passed this knowledge on to other young men. As a young man, he worked sawing mulga trees for firewood and later became a gardener in the Yuendumu area near Four Mile Bore, where he was involved in growing watermelons, cucumbers, carrots, tomatoes and other vegetables. He worked at the Yuendumu School teaching jukurrpa, painting, hunting, traditional dancing and bush tucker, and helping out with excursions “out bush”, as well as to Alice Springs and Darwin.

For a long time, Japaljarri painted at the Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation, an Aboriginal-owned and -governed art centre, and exhibited regularly with Warlukurlangu Artists both nationally and internationally from 1985. In 1988, Japaljarri was selected by the Power Gallery, University of Sydney, to travel to Paris with five other Warlpiri men from Yuendumu to create a ground painting installation at the exhibition Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou. The trip took place in May 1989, and the painting received worldwide acclaim.

Japaljarri was also one of the five senior male artists who painted the original Yuendumu Doors – groundbreaking in pioneering two-way learning at the Yuendumu School and beginning the Warlpiri art movement. In 2000, Paddy Japaljarri Stewart, his good friend, undertook to produce 30 etchings of the original Yuendumu Doors in collaboration with Japaljarri and under the guidance of Basil Hall, Northern Editions Printmaker (Northern Territory University). The first print of the etchings was all on one page and had its debut alongside the Yuendumu Doors when they were exhibited in Alice Springs. As a set, the etchings were launched in 2001 to great acclaim, winning the 16th Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award for works on paper.

Japaljarri’s work has been included in numerous general exhibitions of Aboriginal art including Dreaming: The Art of Aboriginal Australia (The Asia Society Galleries, New York, 1988), The Continuing Tradition (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1989), Mythscapes: Aboriginal Art of the Desert (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1989) and L’été Austràlien a Montpellier (Musée Fabre, France, 1990).

Japaljarri sadly passed away in 2010.

1 Kramer was sent out to bring Warlpiri people in to meet the members of the Board for Anthropological Research, who were set up at Cockatoo Creek.

2 David Nash has an online bibliography of Warlpiri song materials (http://www.anu.edu.au/linguistics/nash/aust/wlp/wlp-song-ref.html) that lists approximately 60 items.

3 See the documentary Fight Fire with Fire (1995), by Pitjantjatjara Yangkunytjatjara Media and Warlpiri Media Association, for an overview of the establishment of remote media organisations in Yuendumu and Ernabella in the 1980s. In 2016, the documentary Satellite Dreaming, produced by Ivo Burum and Tony Dowmunt, gives an overview of the introduction of media communications into remote Australia, featuring Yuendumu and Warlpiri Media Association’s history.

4 The Broadcasting for Remote Aboriginal Communities Scheme (BRACS) was introduced by the Australian federal government in 1985 and allowed for local broadcast of radio and video services via being beamed from the new AUSSAT satellite, including locally produced video and radio programs.

5 Hinkson criticised Michaels’ approach in the 1980s, arguing that he pushed for Warlpiri engagement with a particular version of self-determination that was focused on “cultural maintenance” or “cultural reproduction” and allowed Warlpiri people only “one way of engaging with new media” (2002, 205). In the 1990s, the Tanami Network rose as the first publicly accessible and Aboriginal-owned videoconferencing facility in the Northern Territory, and the use of new technology was incorporated into ever-developing intercultural social relations and engagements (Hinkson 2002, 209–212).

6 Fisher is refering to the Ara Irititja Archival Project at the Strehlow Research Centre and NT Library. PAW Media purchased a licence for the archival access point Keeping Culture based on this platform.

7 In addition to the collections outlined in this chapter, this project has also seen additional digitisation and organisation of other collections of recordings of Warlpiri songs, including those made by Jennifer Biddle in Lajamanu and Françoise Dussart in Yuendumu in the early 1980s.

8 The late Harry Jakamarra Nelson, who passed away in February 2021, was a cultural broker for Barrett and older Warlpiri men that he recorded. Many older Warlpiri people also remember Barrett’s visits to their communities, with Francis Jupurrurla Kelly even being trained as a dental assistant to Barrett.

9 For example, when Nancy Napurrurla Oldfield heard these recordings, she reminisced about the purlapa that used to be held in Yuendumu’s south camp when she was a young girl. She described how men used to dance around in a circle beating their fists alternately on their chests in keeping with the rhythm of the song (Curran, Fisher and Barwick 2018; Curran and Sims 2021).

10 In this community, Warlpiri people identify with Wakirti Warlpiri language, also spoken in the communities of Alekarenge and Willowra (see O’Keeffe et al., in press).

11 Linda Barwick has organised and documented this collection to be accessed easily by appropriate Warlpiri women.

12 Extensive black and white cinefilm footage was also taken during the Board for Anthropological Research missions at Cockatoo Creek (1931, 1936, 1951), but this has remained only available in archives (South Australian Museum and AIATSIS) and contains restricted material that Warlpiri men have not wished to make publicly available.

13 Thanks to Lauren Booker who assisted with the reviewing and editing of these films, working closely with senior Warlpiri women and Anne Mosey in Yuendumu in 2019.

14 Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC) staff member Jodie Kell and honours student Grace Barr have adopted a key role in developing these lyric videos in collaboration with Warlpiri singers and younger, literate learners.

15 For more information on the Raspberry Pi server, which provides remote offline access to a website, see https://language-archives.services/about/data-loader/.

16 Yuendumu school has “Country visits” each term to various outstations around Yuendumu. Family groups go together to these sites and spend the week focused on learning about the places, jukurrpa, songs and dances from Elders. The Southern Ngaliya dance camps are held biannually and involve women from Warlpiri communities gathering for three or four days to sing and dance yawulyu. Incite Arts and Warlpiri Youth Development Aboriginal Corporation have collaborated with Warlpiri women to organise these since 2010.

17 Because this statement may sit at odds with some traditionalist understandings of taboos around viewing images and listening to the voices of deceased Aboriginal people, Nelson made this statement explicitly to ensure that future generations would recognise the value of engagement with these media and the shifts that had occurred within his lifetime around these cultural protocols.

18 Jardiwanpa and Kurdiji are the names of two ceremonies in which men sing and women dance (see Curran 2020 for further descriptions).

19 Harry Jakamarra Nelson and Otto Sims, interview with Simon Japangardi Fisher, 2017.