3

A Warlpiri winter solstice ceremony: Performance, succession and the jural public

Warlpiri people heartily dislike the bitter cold of midwinter nights when the temperatures can drop to freezing, and the daytime temperatures are kept cool by the winds from the south-east that blow into Central Australia, bringing cold air from the aptly named Snowy Mountains. In 1972, I witnessed a publicly held winter solstice ceremony at Yuendumu, the explicitly articulated purpose of which was to shorten the night and hasten the warmth that comes with daylight.1 I imagined that such a ceremony would be a regular event – but, to my surprise, I learned that it had last been held probably between 1947 and 19492 and a performance before that had been held when many Warlpiri were living at Mount Doreen Station, immediately to the west, probably in the late 1930s. Nor has the ceremony been held again since 1972.3 Thus, despite the obvious avowed purpose, the ceremony had been held only three times in roughly 70 years, suggesting there were additional reasons for holding it. These emerged gradually.

The ceremony was held over 12 days, from 4 to 15 July 1972. Shortly after it finished, an Aboriginal friend of mine, Sammy Japangardi, who had worked closely with linguist Ken Hale but who had not been at much of the ceremony, came across to where I was living in the south-east of Yuendumu and said he wanted to record a letter for his friend Ken Hale (Japanangka) about the ceremony. This is what he said, as translated by Hale:4

Jampijinparlu ka mardani panulku marda. Jintakarirlangu wulpararri-yangka ngularra. Pinalku ka nyina Jampijinpaju. Wulpararri yangka nyampu kankarlumparra kujaka nguna; ngulaju ka Jampijinpaju pinalku nyina. Kulakalu yanga pinyi purlapapiya kala ngula-kalu wirnti Ngarrkapatuju kalu yangka wirnti, wati. Yarlu ka wiri karrimi. Ngunamika yangka walya, yarlu wiriyijala. Ngulakalu wirnti; karnta, ngarrka. Wulpararri, ngula kalu manyulunyangu(?) jukurrpawarnu, nguru ka rdangkarlmani munga, mungajala wulparrarriji. Ngulakalu wirnti yunparni kalu parrangkarlu, mungangkarlu. Kurdungurlu, kurdungurlu kalurla mungalyurrulku kalu wirnti. Mungalyururlangu. Kurdungurluju. Kirda, kirda ngulaju Jungarrayi, Japaljarri, Japanangka, Japangardi kirdaju. Wulpararriji [and] Jakamarra, Jupurrurla ngula kurdungurlu. Jangala, Jampijinpa kurdungurluyijala kalu nyina [That’s’ right and]… Napaljarri, Nungarrayi, ngula kirdayijala. Yangka ngarrkapiyanyijala kalu nyina kirda. Nungarrayi, Napaljarri. Napanangka, Napangardi. Ngulaji kirdayijala. Ngarrkangku kalunyanu kijini yangka purlapapiya, mardukuru, kirdangku, Jungarrayirli Japaljarrirli; karntangku, ngulakalunyanu kijini yawulyu. Yawulyuyijala kalunyanu kijirni karntangkuju yangka Napaljarrirli, Napanangkarlu, Napangardirli Nungarrayirli. Ngulakalunyarnu kijini yawulyu. Wirntinjakungarntirliyijala. Ngarrkaku kalujana kurdungurlurlu kijini madukurru. Nguyungku kalujana maparni maru. Maru yangka jukurrpa yangka nguyu, ngula munga. Wulpararri maruju. Ngulaju. Wanjilypiri. Kujaka yangka wulpararrirla nyinanjarra yani wanjilypiri, ngulaji jukurpayijala kalu purami nyanungu munga. Kulalparna(ngku) ngaka nyampu nyurruwiyirlangu ngarrurnu Japanangka nyuntuku.

Jampijinpa [NP] has a lot now evidently. Including among others the Wulpararri [the Milky Way ceremony]. He is knowledgeable about that. About the Wulpararri which lies above (i.e., classed as kankurlumparra, open, public [?]); with that, Jampijinpa is now familiar. It is not performed like a purlapa [a secular camp ceremony], but they dance. The men dance, the men. A large clearing is there, the land lies there, a big clearing. And they dance; men and women. They perform the Wulpararri of the jukurrpa. They shorten the sky, I mean the night. The Wulpararri is of the night. They dance and sing, in day time and night time. The kurdungurlu dance if in the morning (?) for example, in the morning. The kirda, that is jungarrayi, japaljarri … That’s the kirda of the Wulpararri. The kurdungurlu, that’s jakamarra, jupurrurla, jangala and jampijinpa – those are the kurdungurlu [that’s right, and] napaljarri, nungarrayi, they are also kirda. Just like men they are kirda. Nungarrayi, napaljarri, napanangka and napangardi. They are also kirda. The men decorate as for purlapa, with mardukuru [plant down], i.e., the kirda – Jungarrayi and Japaljarri. The women, they decorate yawulyu; they decorate yawulyu, those women – Napanangka, Napaljarri, Napangardi, Nungarrayi. They decorate yawulyu. They decorate yawulyu in preparation for dancing. The kurdungurlu men put the mardukuru on the men they rub them with charcoal. Black. Black is the jukurrpa, charcoal, that is the night. The Wulpararri is black. That’s stars. That lie along the Wulpararri, you know. Thus, they follow the night jukurrpa. I never told you about this before Japanangka.

Ngaka karnangku nyampuju jalangurlu yilyamirra. Yangka munga jukurrpa nyanungu, Wulpararri. Yarrungkanyi, manu kumpu. Ngulaji kulkurrujarra ngulakula yangka nyanunguju munga jukurrpa. Ngulajangkalpa yanulku yangka wirlinyilpa yanu, ngulalparla yalikarilki mungajarrija. Wulpararri yanurnu Yarrungkanyi ngula karlarralku yanu. Mungaju parrangkawiyilpa yangka yanu. Nyampu karnarla Jampijinparlanguku milki-wangka, karnangku yilyamirra Jampijinpawana, jaru, yimi nyampu karnarla ngarrini munga, wirlinyilpa yanu yangka munga, parrangkawiyilpa yanu. Ngulalparla mungajarrijalku Wulpararri; jintajukujala. Ngulajangka, purlapapiyalku kalu yangka pinyi. Wirntimilki yikalu kulakalu pinyirlangu, kala wirntimilki kalu. Karnta kalu wirntimi pirdangirli, ngarrka kalu kamparru wirnti. Yangka kanardijarra. Kanardiyijala, ngarrka, watiji kanardijikijala kalu wirnti. Ngarrka manu wati jintajukujala; karnta kalu pirdangirli wirnti, watingka purdangirliyijala. Ngarrkangka yangka purdangirliyijala. Kanarliyijala. Ngarrka kamparru. Kamparrukura kalu wirnti. Kakarrarapurda. Karnta, kakarrarapurdayijala purdangirli, ngarrkangka purturlurla. Wulpararri nyanungu yarlungkaju kalu wirntimi. Kujakalu wirnti, ngula kalu munga rdangkarlmani. Nyiyaku kalu yangka rdangkarlmani yunparni kujakalu wulpararri. Wulpararri kalu rdangkarlmanilki. Yinga yaruju rdangkarrkanyi. Rdangkarrkurluku yangka, kajipanpa ngunakarla, jarda, ngula kajikanpa kapanku nyanyi, mungalyurrulku. “Hey!! Nyurru rdangkarrkangu”. Ngulalku kalu yangka rdangkarlmani. Yunparninyjarluju. Mungangkarlu kalu yunpani. Mungangkarlu tarnnga kalu yunpani. Nyina kalu parrangka … mungangkarlu kalu yunparniyijala, mungalyurru-mungalyurrulku yangka. Kujaka rdangkarrkanyjani, wurnturuwiyi, wanyjiljpiri ka yangka wiri jinta yarnkamirni, kujakalu ngarrini “daylight star”, ngulapiya, ngula kalu ngarrini “yarnkamirni ka” wurnturu yangka kujaka rdangkarrkanyjani. Yunpani kalu, nyiyaku wulpararri ngula kalu rdangkarlmani. Yangka kujaka, yinga yarujulku rangkarrkanyi. Rdangkarrkanyi yinga rdangkalpalku. Nyiyaku, kujakalu ngarrini rdangkarlpa, ngula yangka, short while kujaka yanirni ngulapiya. Kujakalu yangka panukari ngunamirra ngurrangka, ngula kulalpa kapankurnu rdangkarrkangkarla. Kirda yangka kujakalu ngunamirra ngurrangka. Kirda kalu panukari nyina, ngampurrpa, ngampurrpa kalu yangka yanirni panukari, ngulajuku ngurrju. Panukari kulakalu marda yangka ngurrju nyina ngampurrpa yaninyjarniki, manyukurra, wulpararrikirra yangka mungaku nyanunguku yunparninyjaku rdankarlmaninyjaku, mungaku yangka rdangkarlmaninyjaku yinga yaruju rangkarrkanyi. Kala panukari kujakalu yangka ngunamirra kirda, kulalpa ngulangkaji yaruju rangkarrkangkarla mungaju. Mungaju. Munga ka nyina, yangka tarnnga, kujaka, rangkarrkanyi, wurra, ngaka, ngulaji, yangka yaliki kajana, ngampurrpayijala mungaji nyina, kulakalurla panu yanini turnujarrimi. Kirda. Ngulangkaji kulalpa yantarlarni yangka munga yaruju rangkarrkangkarla. Pulyayijala ka yanirni mungaju. Rangkarrkanjarni yani. Kala kajilpalu panu nyinakarla, kirda, wulpararriki, yangka yarlukurra yantarlarni, ngurrangka ngunanyjaku ngulangka, ngulaju ngurrju. Japaljarri, Jungarrayi, Japangardi, Japanangka. Panujuku yangkalpalu yantarlarni. Kurdungurluju ngulajukujala ngurrjujala kurdungurluju, Jakamarra, Jupurrula, Jampijinpa, Jangala yangka kalu yanirni panujala, ngurrju, ngulanya.

Only now am I sending you this. About the night jukurrpa, you know, Wulpararri. Yarrungkanyi and Kumpu [two places associated with the night Dreaming]. Between them, that’s this night jukurrpa. From there he went hunting and at some point darkness fell on him. The Wulpararri came (from) Yarrungkanyi and went west then. The night. First, he went in daylight. This I am speaking for Nic’s instruction as well; I’m sending you this talk, I’m speaking this word about night, he went hunting, the night; first he went in daylight. Then night fell on him. It’s the very same Wulpararri. Now they perform it like a purlapa, you know, they dance but do not pinji [contrast wirnti- with pu-] They do not pu- but rather wirnti. The women dance behind, the men dance in front. You know, in two lines. The man, or men dance in a line. Ngarrka and wati mean the same [mature male]; the women dance behind, at the backs of the men, at the backs of the men, in a line also. The men are in front. They dance toward the front eastward. The women also dance eastward but behind; at the backs of the men. That Wulpararri is danced on a clearing. When they dance they shorten the night. (? …) they shorten something while singing the Wulpararri. They shorten the Wulpararri. In order that it will quickly dawn. The dawn, you know, if you sleep then you suddenly see the morning. “Hey, it has already dawned.” So they shorten it, by singing. They sing at night. All night they sing. They sit during the day and they sing at night, till early morning. When it dawns, in the distance at first, the big star appears, that they call the “daylight star”, like that, they say “it’s appearing” in the distance when it begins to dawn. They sing to thereby shorten the night. You know … in order for the dawn to come quickly. So it dawns short. What they say short, that you know, “short while” coming, like that. When some sleep in camp, it won’t dawn quickly. If the kirda sleep in camp. But [when] some of the kirda are desirous and come, that is good. Some might not want to come to the performance, to the Wulpararri to sing the night and shorten it so that it dawns quickly. But when some kirda stay away, in that event the dawn cannot come quickly. The night. The night stays long, only eventually will it dawn, after a long while. If they don’t all gather for it. The kirda. In that event, the night can’t come quickly and dawn. The night passes slowly and the dawn is slow. But if all the kirda attend the Wulpararri, at the clearing and if they camp there, then it is good Japaljarri, Japangardi, Japanangka all should come. The kurdungurlu likewise, Jakamarra, Jupurrurla, Jampijinpa, Jangala they all come. Good. That’s all.

Pattern of daily activity

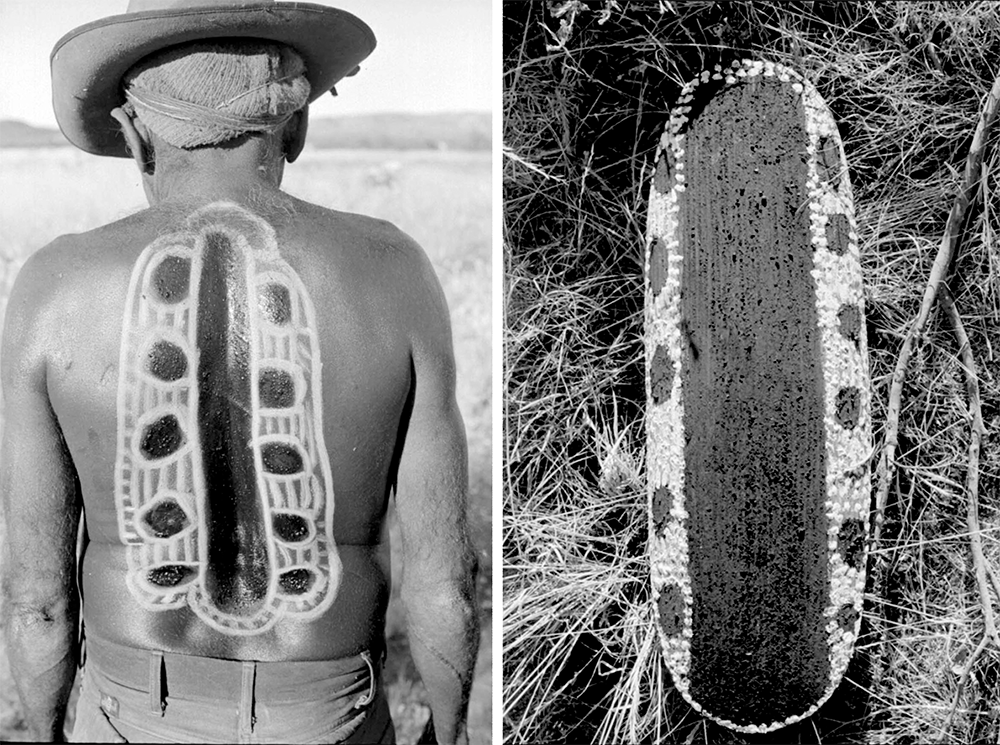

The general pattern of activity on each of those days was for men and women to gather, in two separate spaces, 50 or so metres apart, during the course of the afternoon (see Figure 3.1). By most late afternoons, between 20 and 50 men had come to the ground at some stage, with most staying. The numbers of women were similar but sometimes higher. Up to 12 men of the kirda’s (owner’s) patrimoiety would be decorated with black on their bodies outlined in white plant down (mardaguru) and with wood shavings (rilyi)5 in their headbands at first and in later days kukulypa (shavings still attached to the stick). In the case of the men, this would take place 30 metres or so to the south-east of the main ground (see Figure 3.2). Several oblong objects 68 centimetres long and 25 centimetres wide were made that represented uncircumcised boys, and some small oval objects 25–30 centimetres in diameter, representing stars. Like the two shields used, all the objects were painted in black, outlined in white (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.1 The three leading kirda, Jimmy Jungarrayi, Paddy Japaljarri Sims and Banjo, dancing on one of the first days, with women visible in the background but not yet dancing. Photo by Nicolas Peterson, 1972.

Figure 3.2 Kirda men moving to the ground for the daily dance. Photo by Nicolas Peterson, 1972.

Figure 3.3 (Left) Body painting on Joe Jampijinpa, a kurdungurlu, with the black pigment from burnt Hakea bark outlined in ground white ochre (ngunjungunju) mixed with plant down and laid onto a greased back; (right) a shield with another version of the Munga image. A few black lines can be seen attached to some of the stars. This is night emerging at sunset. Photo by Nicolas Peterson, 1972.

The women painted up each day with a range of yawulyu designs over the 12 days for the important places of Janyingki, Minamina and Kunajarrayi, as well as for the route of the initiated men or Munga (night or darkness) jukurrpa. As with the men, some of the kurdungurlu were also painted up, the women often sitting in two separate kirda patricouple groups, the Napapangka-Napangardi group being decorated with Minamina or Janyinki designs. These two places relate to the travels of an ancestral group of women going east, taking young boys for circumcision in Anmatyerr Country, which contrasts with the route of the initiated men taking boys to the west. At the conclusion of the singing, most of the women returned to their camp, and only a few older women stayed behind.

In the initial days, the oblong objects used by the men were mainly held horizontally while dancing in a sideways hopping way, north–south and facing east.6 At the end of the dance, the objects were thrown over the heads of the men and caught by the women dancing behind (see Figure 3.4). Those not holding objects danced with their arms bent at the elbows, palms face up, moving their arms up and down towards their shoulders as if throwing something over them, a movement in common with the women dancers. This was explicitly to encourage the Milky Way to move across the sky more quickly so that daylight would arrive sooner. The dancing took place between 5.00 pm and 6.30 pm each evening for three to five minutes, as it started to get dark, to the accompaniment of singing. The managers danced briefly after the owners each night. Some few people, less than half a dozen, were sleeping on the ceremony ground.

Figure 3.4 Kirda dancing in front of the Milky Way earth mound with a kurdungurlu standing on the right. Their body decoration is made with plant down (mardukuru) coloured from the same sources as the kurdungurlu’s decoration. Photo by Nicolas Peterson, 1972.

On the first day, as the dancing began, there was a brief period of wailing in memory of Wally Japaljarri, the previous holder of the ceremony. That night, a small group of men may have sung all night or at least late into the night. On day three, the ground was modified with a long, raised mound of earth 19 metres long, 76 centimetres wide and 23 centimetres high, stretching north–south, on which the ashes and charcoal from the night fires were scattered each morning (see Figure 3.4). On day four, a trip was made to Jiri, a site associated with the travels of the ancestral initiated men, to collect natural stones that were manifestations of these ancestral men. These stones were incorporated into the headdresses of the senior male dancers in subsequent days.

On days 10–11, much time was spent by the kurdungurlu making an object 7.6 metres long and approximately 20 centimetres in diameter of grass and cloth wrapped around two sturdy saplings, which in turn were wrapped around with hairstring, near the preparation area, to the south-east.7 When completed, this would represent the Milky Way. On the evening of the penultimate day, there was talk of singing all night, but it was bitterly cold, and we all went to sleep after a couple of hours. In the middle of the night, there was a brief period of singing; however, due to the cold, we were soon asleep again. One of the oblong objects had a cross piece added to the top and was explicitly identified as a marlulu (male novice prior to circumcision).

Throughout the ceremony, a series of payments was made between the kirda and kurdungurlu. When food was involved, it was brought by the kirda for the kurdungurlu. Most of these payments happened very informally; I witnessed only one group of them on the penultimate day. A kirda brought a large billy can full of boiled eggs and chicken for the kurdungurlu. Earlier, the senior kurdungurlu had received about $40 from the kirda. He kept $12 and put the $28 down on the ground where a group of kurdungurlu was sitting; most took $2, but one senior kurdungurlu gave $10 to one man. The kurdungurlu then collected $26 for the kirda, four of whom got $5 apiece and one $6, with $10 coming from the senior kurdurngurlu, who had kept $12 of the original payment, and the rest contributed by other kurdungurlu, who had not shared in the distribution of the $40.

On the final afternoon at 4.00 pm, the kurdungurlu brought the kirda over to see the emblem of the Milky Way they had been working on for the last few days to the south of the dancing space. When the organiser of the ceremony, Paddy Sims, whose name was Wulpurrari, arrived at the ground, his face was painted red, and he wore a feather through his nose; but, by sunset, his face was black and white like the rest. At sunset, 11 kirda men carried the long object representing the Milky Way onto the ground and danced facing east, moving it up and down.8 The women danced behind them. They danced for three verses and then put the object down on the mound, thus concluding the ceremony (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 Kirda bringing the Wulpararri emblem onto the ceremonial ground on the final afternoon. This image appears in the David Betz film Singing the Milky Way (2006). Photo by Nicolas Peterson, 1972.

Figure 3.6 The ground at the end of the ceremony showing the Milky Way as an earth mound covered in the ashes from the overnight fires of people sleeping at the ground, with four of the kukulypa still upright on the mound and the emblems placed on it. The group of kirda and kurdungurlu men is settling up after the ceremony. Photo by Nicolas Peterson, 1972.

The ceremony raised a number of questions, but no answers were forthcoming at the time: Why was it held so sporadically? How did people remember what to do and keep the right songs in mind with such infrequent performances? What precipitated the holding of the ceremony in 1972? And what was the connection between night and initiated boys?

Travels of initiated men jukurrpa

Upon inquiring as to whom the appropriate person was to ask about the travels of the initiated men connected to the Munga jukurrpa, I was directed to Karlijangka, Peter Japaljarri, a ceremonial leader in the north camp. I asked him about the travels of the men, and this is what he told me:9

A group of initiated men emerged out of the ground at Bilinara north of the Tanami in Mudburra/Gurindji country. They travelled south to Dunmarra where they held a Kankarlu ceremony making the youths travelling with them into men, travelling further south they arrived in Warnayaka country and at Mirirrinyungu held an initiation ceremony with young boys brought to the place by a Nangala from the southwest. Further on they arrived at Kurlurrngalinypa holding both circumcision and subincision ceremonies before moving on. At a certain point the group took to the sky and landed north of Kiriwaringi. An old man sleeping some way away saw the travellers, picked up his boomerang and pretended to be asleep. The leading traveller was attacked by this man, Pirilpungu, and killed. The skin and bone of the dead man were scattered but when the head fell to the ground the skin and bones gathered around it and the man reconstituted himself. He then killed Pirilpungu and the same thing happened to him. The two men became friends. From Kiriwaringi the party split into four groups all travelling south, at least two of the parties travelled through Lungkardajarra where there was a big rainbow snake. At Ngiji one of the groups lit firesticks from a soakage and before meeting up with the other three groups at Kaljukarrka, north of Jila well rockhole. They flew away from here and landed at Pakarlipanta where there are three soakages, before going on to Manajarrayi where they made more young men. At Jalayanpiri, a large claypan, they used vines to make witi poles for a circumcision ceremony before flying away to Yanjilypiri. Here Pirilpungu was killed as they were short of fat. They removed the fat from his kidneys and kept it in small parcels behind their ears like tobacco. The man he had fought with in the north looked around for him but could not find him. He made a sacred object in memory of his dead friend, brought it around in the darkness to where the men were sitting on the ceremonial ground, and sat down feeling sorry. He then painted a cross on his chest and moved closer to the men. They asked him what songs he wanted to hear. He was not fooled by their friendliness knowing they had killed his friend. When they started singing Walupurrkupurrku jipijipi he gathered everybody up in a whirlwind and pushed them deep into a hole in the ground, putting them to death for ever. The skin and bones of the dead friend went back to Mirirrinyungu and there the dead man reconstituted himself.

This account brought together partial information given to me by numerous people about the travels of the initiated men over the days of the ceremony. I also spoke to Banjo Jungarrayi, a close Countryman of Paddy Sims, who would have been more actively involved in the ceremony had he not been unwell. He listed the places the men travelled to after Yanjilypiri as they went west: Jiri, Manjagururri, Yaljawariji/Paryilpilpa, Ngalpi (the Munga emblem was dropped here and unravelled), Kurijiydulpa, Kunjari (the head of the Munga ancestor fell down here and the travels ended).10

Mervyn Meggitt has an account of the travels of the initiated men (1966, 106–113); however, other than a few commonalities regarding where the travels started from, the account is quite different from that of Karlijangka – only the places of Kurlurrngalinypa and Yanjilypiri are in common. Indeed, the two accounts could hardly be more different. Further, while Meggitt’s account includes references to night and the Milky Way, Karlijangka’s account does not. This is because, in Karlijangka’s account, the circumcision ceremony is the Munga ceremony.

The right to hold the ceremony

The 1947–1949 performance of the ceremony was associated with Wally Japaljarri, the senior owner of the ceremony, having speared a Jupurrurla man in the foot.11 The ceremony was held by way of compensation, although exactly how this acted as compensation is still unclear. It was also the occasion when Paddy Sims, the organiser of the ceremony I witnessed, learned about the ceremony, but he did not make it clear to me why he decided to put the ceremony on when he did. It was not until many years later, when I was talking with a man in his forties, that I got an answer, even if only obliquely: “Wulpurarri [Paddy Sims] held the ceremony because he could.”

Wally was the former senior owner of the ceremony and of the unrelated site of Kunajarrayi, as well as a formidable man with a reputation as a fighter, who had died around 1968.12 Paddy had acknowledged rights in Country 30 kilometres to the north-west of Kunajarrayi at Nyinyirripalangu and Panma, where his father was buried. He was of the same patricouple as Wally and as the ancestral travelling men with boys who had come from Kurlurrngalinypa in the northern Tanami to Yarrungkanyi (Mount Doreen) in almost all accounts I heard, except that from Karlijangka, and then on to Yanjilypiri before travelling west. Although Paddy was named after the Milky Way, he could not hold the ceremony while Wally was alive, as Wally was the senior man in the area and would not let him. Once Wally had passed away, he could hold the ceremony himself and appeared to be motivated to do so by two factors: he intended to have his son circumcised the following year and, by using this reason for putting on the ceremony, Paddy was able to demonstrate that he was now in control of the ceremony and the associated sites. Further, he was also keen to assert that he was the appropriate person to control the important nearby site of Kunajarrayi, as Wally had not left any heirs. This recognition was provided by the willingness of the senior men in the neighbouring estates at Yarripilangu to the south-east and Janyinki to the north to participate in the ceremony as their acceptance of the legitimacy of holding it was essential to its widespread acceptance.

Their support is shown by the list of men who were present on most days the ceremony was held and, particularly, on the final day when the key men of the kirda moiety joined together to carry the main Milky Way emblem onto the ceremonial ground (see Figure 3.5). These were the men in order, with their Country indicated in brackets:

Jimmy Jungarrayi (Yarripilangu)

Mick Jungarrayi (Yarripilangu)

Dinny Japaljarri (Kunajarrayi)

Paddy Sims Japaljarri (Panma)

George Japangardi (Country unknown)

Andy Japangardi (Janyinki)

Pompey Japanangka (Janyinki)

Paddy Lewis Japanangka (Pintupi from the west)

George Japangardi (Pintupi from the west)13

Arthur Japanangka (Pintupi from the west)

Jack Japanangka (Pikilyi)

It was essential to involve the two brothers Jimmy and Mick, as the senior men in the area to the south, which is why they were up the front. Both men were fathers-in-law to Paddy Sims’ wife’s siblings, one to a brother and the other to a sister. Next was Dinny Japaljarri, a recognised kirda for Kunajarrayi; although knowledgeable about ritual matters, he did not seem to have any ambition to be a leader in ceremonial affairs, as is indicated here in his endorsement of Paddy’s actions. I am unable to place George Japangardi, but Andy and Pompey were the two senior men from the Country to the north, with Andy married to Paddy’s mother’s brother’s daughter. The Pintupi men were close Countrymen of Paddy’s from further west. Jack Japanangka was the senior man for the important area around Pikilyi to the east, which is also close to both Kunajarrayi and Yanjilypiri. The senior manager was the father of Paddy’s wife, and three of the most active kurdungurlu were his mother’s brother’s sons.

The songs

Twenty-two distinct songs were sung over the days of the ceremony. The singing was typical of such ceremonies. From time to time, while people were getting decorated and preparing ceremonial objects, they would sing one or two verses. Then, in the late afternoon, as the sun set, they would dance and sing a sequence of songs. I did not record the songs each day, so I am unclear how much variation there was, but my impression was that there was little if any. Table 3.1 lists exegeses for the songs recorded on the final day, based on commentary by Long Paddy Jakamarra with permission from Paddy Sims.

Table 3.1 The songs sung on the final day of the ceremony with exegeses provided by a senior man.

| English exegesis of verse | |

|---|---|

| 114 | The men are walking along carrying the Milky Way on their shoulders. Their backs are getting sore. The managers threaten to spit in disapproval because of the behaviour of the owners in putting down the Milky Way on the plain. |

| 3 | In the very distant east, the second light is appearing. |

| 4 | In the distant east, as the women dance, daylight starts to come quickly. |

| 5 | I was running quickly, daylight in the distance, I with my child’s legs running. |

| 9 | As the sun sets, the sky is red and black with patches of darkness as the sun goes behind the mulga windbreak.15 |

| 13 | Evening stars emerging in the east, all the other stars emerging in the east.16 |

| 21 | The legs of all the Jungarrayis are shining. |

| 22 | The legs of all the Japaljarris are shining. |

| 30 | Coming close, coming quickly from Yaruju, the children are playing. |

| 33 | All the stars of the Milky Way are falling down in the south. |

| 39 | I, Yijingapi, am running quickly like the flight of the moth. |

| 42 | The moth hangs in the wurrkali tree opposite the sitting singer. |

| 48 | Holding a ceremonial object that looks white like the butterfly that appears in the daylight hours. |

| 51 | Holding the white ceremonial object that looks like the Morning Star coming out. |

| 55 | Over there in the distant east, black streaks appear between the first rays of the sun. |

| 92 | Morning Star, stands out as the shining one among many stars. |

| 97 | I straighten out the file of people as they walk along. |

| 118 | (obscure – may refer to rubbing ochre and fat over the boys to be initiated each day). |

| 122 | I am going to make plant down for my relatives. |

| 132 | Stars slipping away (i.e., nearly morning). |

| 135 | Look to the west and see the sacred object. |

| 136 | They walk along in a spread-out line. |

The actual sequence of songs sung is listed below.

1(1); 2(1): 3(3); 4(4); 5(5); 6(5); 7(1); 8(1); 9(9);10(9); 11(5); 12(5); 13(13); 14(1); 15(1); 16(13); 17(1); 18(1); 19(1); 20(9); 21(21); 22(22); 23(22); 24(22); 25(4); 26(5); 27(5); 28(4); 29(4); 30(30); 31(30); 32(9); 33(33); 34(33); 35(9); 36(9); 37(33); 38(33); 39(39); 40(39); 41(39); 42(42); 43(39); 44(33); 45(33); 46(33); 47(33); 48(48); 49(48); 50(48); 51(51); 52(51); 53(51); 55(55); 56(55); 57(55); 58(55); 59(55); 60(51); 61(51); 62(51); 63(51); 64(51); 65–72(1); 73–76(30); 77–82(28); 83–87(48); 88–91(51); 92(92); 93–96(92); 97(97); 98–106(97); 107–111(33); 112–117(1); 118(118); 119–121(118); 122(122); 124–127(48); 128–131(51); 132(132); 133–134(132); 135(135); 136–137(135); 138–140(92); 141(141); 142–143(141); 144–145(21); 146–147(22) (it’s not clear at the end of the tape that the ceremony is finished, but it is very close if not).

In the songs, there is no direct mention of night, only of the Milky Way, daylight, the setting sun and the Morning Star. The orientation is to the east, but the reference of the rest of the songs is to carrying the Milky Way on the shoulders going west. The reference to carrying the Milky Way on the shoulders is to the initiates who are being taken to a circumcision ceremony, alluded to as a Munga ceremony here. The other references in the songs are obscure, and no interpretation was offered by the men I spoke with. Most of the songs are shared with other rituals, including those held at the last Kankarlu ceremony under Karlijangka’s direction two or three years before this ceremony, and the Ngarrka or initiated men’s jukurrpa songs that can be part of the annual initiation ceremonies.

While discussing this ceremony with a colleague, David Nash, he asked whether the conjunction of the Morning Star with the winter solstice was a significant part of the ceremony. I do not know; however, on the basis of our conversation, I think it possible, given that this ceremony (and the previous one) appear to have a relationship with it. This is because the Morning Star would only be around at the time of the winter solstice every eight years, when the star reaches its maximum elongation – that is, rising with the greatest time gap before sunrise.17 In 1972, this was on 27 August. Going on this calculation, the previous performance of the ceremony, which I had estimated to be between 1947 and 1949, would have been in 1948, when the maximum elongation was on 3 September. Unfortunately, I have not been able to verify this link with any knowledgeable Warlpiri person at this stage. It makes a great deal of sense to me that the ceremony was not performed every year, as I originally assumed, and this is an object lesson in taking anything to do with Warlpiri ritual and religious life too literally.

Performance, succession and the jural public

While the tendency today is for outsiders to see ceremonies such as this one as cultural performances that can be revived if the proper details exist in the ethnographic record, the word “performance” is misleading (e.g., see Michaels 1989). While the performative approach to the Munga ceremony would usually emphasise the enactment, staging and aesthetics of the dancing, singing, fabrication and decoration – which fits with the idea of revival and restaging of such ceremonies – this is to approach the ceremony from the point of view of an audience member. However, there is no audience at such a ceremony, even if some people are apparently just watching. The importance of the performance is that it is doing something, bringing something about and changing things; consequently, it is integral to the social relations between all the people present.

Sims had to secure agreement from a range of parties with different interests to hold the ceremony. A group of regional kin had to agree that he could legitimately take control of the ceremony despite his inability to hold it earlier. By holding the ceremony, he consolidated his claim as Wally’s heir and to a wide area of Country east of Panma, including the important site of Kunajarrayi. Although there must have been verbal discussion of this, only by holding the ceremony could this be publicly ratified. By holding the ceremony, he could demonstrate that he had not only the ritual knowledge but also, and more importantly, the support of the senior men in the area. This required their active physical participation in the ceremony for all to see. The important people in this event were the kirda, senior men in the same patrimoiety from neighbouring Countries. This was not a situation in which the kurdungurlu were custodians of knowledge in a regency context but one in which a kirda man could succeed to an adjacent Country and the high status associated with it, due to the important site it encompassed, only by getting other senior Countrymen to acknowledge his claim through their participation.

This gathering was a manifestation of what is now frequently referred to as the jural public, which must, in effect, ratify the succession. What is striking is how small the effective core of such a public can be. The average daily male presence at the ground was 36, and not one of those who attended more than four times came from the north or east sections of the Yuendumu community. The highest number of men at the ground was on the second day, when several people clearly came just to see what was happening. Of the total of 89 men who appeared over the 12 days, 35 came on only one or two days. A number of younger men appear to have come due to kinship obligations, three men because they were actual brothers-in-law to Paddy Sims, and at least four others because they were sons of key participants. One key Janyinki kirda and his son came three times between them when it might have been expected that the father, at least, would have been there most days. Thus, the participation was virtually entirely from the west camp, underlining that the ceremony was very much about social relations within that group of Countrymen, and the participating women being the wives, sisters and other close female kin of these men. The core people were the 10 people with Paddy Sims bringing the Milky Way emblem onto the ceremonial ground and dancing with it, but the presence of others as witnesses to the event was essential.

Conclusion

The emphasis on munga (night) with initiation reflects a cultural association between darkness, the west and women, contrasting with light, the east and men. The ritual death of circumcision takes place at night; the next morning, the boy wakes up as a young man. The more common tradition associated with the initiation of Warlpiri boys is the songline associated with the travels of a party of women from Minamina, near the Western Australia–Northern Territory border, taking young boys east to be made into men (see Curran 2020). In this Munga ceremony, revived after more than 20 years of it not being held, the songs sung were associated with a separate but well-known songline, so it was not a case of the men having had to remember songs they had not sung for a long time. Regarding the Munga emblem and ground plan, the situation was different – as far as I am aware, they had not been created since the last time the ceremony was held.

From a historical perspective, the holding of this ceremony is impressive evidence of the radically different world Warlpiri people inhabited up to the early 1970s. The senior generations clearly believed the underlying title to the land was theirs to be managed in transactions between themselves. They were, of course, aware of the pastoralists’ rights, which were understood just as usage rights; however, as Coniston Johnny, the head Aboriginal stockman for Coniston station, put it so eloquently in 1972, the shade and the kangaroos belong to the Aboriginal people (see Bryson 2002, 46; Mortimer 2019, 162). It is sobering to realise that this ceremony was probably one of the last times that such a claim and ratification to Country took this traditional form at Yuendumu because, by 1979, the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 had been passed, and the Warlpiri land claim had been successful. With those events, Warlpiri people, as had other Aboriginal people in the Territory, quickly understood that their claims to land must be recognised by their being on genealogies and lists held by the Central or Northern Land Council, expanding the politics of recognition beyond their own relatives into the intercultural field.

Acknowledgements

I thank Paddy Sims and the other senior people involved in the ceremony for allowing me to attend, take photographs and record the singing. My greatest debt is to Long Paddy Jakamarra for his year-long tutoring of me about the Warlpiri world. In respect to the Munga ceremony, he helped me transcribe the songs and provided a detailed exegesis. My thanks are also due to Karlijangka for his account of the travels of the initiated men from the north. I am grateful to Ken Hale for transcribing and translating the recording I made of Sammy Johnson’s account of the ceremony for him, to Rosalind Peterson for her notes on the women’s activities and to Georgia Curran for helpful advice. I have benefited enormously from David Nash’s enthusiastic interest in the topic of this chapter, knowledge of Warlpiri culture and our many invaluable conversations.

References

Betz, David. 2006. Singing the Milky Way: A Journey into the Dreaming [film]. San Francisco: Song Lines Aboriginal Art.

Bryson, Ian. 2002. Bringing to Light: A History of Ethnographic Filmmaking at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2020. Sustaining Indigenous Songs: Contemporary Warlpiri Ceremonial Life in Central Australia. New York: Berghahn.

Laughren, Mary, Kenneth Hale, Jeannie Egan Nungarrayi, Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1962. Desert People. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1966. Gadjari Among the Walbiri Aborigines of Central Australia (Oceania Monograph 14). Sydney: University of Sydney.

Michaels, Eric. 1989. For a Cultural Future: Francis Jupurrurla Makes TV at Yuendumu. Melbourne: Art and Text Publications.

Mortimer, Lorraine. 2019. Roger Sandall’s Films and Contemporary Anthropology: Explorations in the Aesthetic, the Existential and the Possible. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Munn, Nancy. 1973. Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sims, Otto Jungarrayi. 2017. “Otto Jungarrayi Sims, Yanyilpirri Jukurrpa (Milky Way Dreaming)”. Uploaded 9 May 2017. Facebook video, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1192303170892978

Tommy Jangala Watson (1948–)

Jangala was born at Mount Doreen Station, where he grew up walking around and eating bush foods. Jangala is kirda for the Ngapa “Rain” jukurrpa that travels through Puyurru. In the 1960s, he worked as a drover, then as a fruit picker and later for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, fixing fences and building houses. He lived with his family at his outstation on his Country in the 1980s. He has worked at the Yuendumu School for a long time teaching kids about Warlpiri culture. He is an important senior man in Yuendumu and has recently been involved in the repatriation of cultural objects from the South Australia Museum.

Culture way, learn jarrijarna, still karna nyinami yangka pirrjirdi karna mardani, milya pinyi nguruju ngaju nyanguju. Karna jana yangka puta puta nganayi mani yangka pina mani nyampuju kurdukurdu-pinki. Wali yantarnirli nyinakalu ngaju nyangurla yirna nyarra pina pina mani yirna nyarra nguru kurrarlangu kanyi, warru kanyi nguru yinya ngalipa nyangu big one ka karrimi, ngulaku.

I know about culture, and I am still strong today. I know everything about my Country. I’m trying to teach my younger generations. Come to me so I can teach you and take you back to country to learn about it, our country is big.

Parnpa waja pinjaku karnalu jana yirrarni young people warrki jarrinjaku.Karnalu jana ngarrirni “ungunpa mardani nyuntu nyangu kurlangu warringiyi kirlangu, ngaju nyangu warringiyi kirlangu whole lot yangka”. Carry on warringiyi nyanu kurlangu tarnnga juku.

We help the young men prepare for the parnpa (where the father of the son in bush camp does the dancing). We say to them, “So you can keep your grandfather’s (father’s father’s) and my grandfather’s [culture] and so on.” They can carry on their grandfather’s culture.

Tarnngajuku karnalu mardani pirrjirdi jiki, karnalu yangka start mani marnakurrawarnu every Christmas time still karnalu mardani palka juku kurdijiji. We also join in Anmatjerre people. Wariyiwariyi-rla and Ti-tree-rla and Willowra-rla, Lajamanu and Nyirrpi kuja nawu.

We still have our culture strongly, we start every Christmas time and we still have our Kurdiji. Anmatyerr people join with us when there’s ceremony going on. People come from Mount Allan, Ti-Tree, Willowra, Lajamanu and Nyirrpi.

Junga waja learn jarrija we bin learn that way, we are living strong jalangurlu but like young people they don’t come and ask em yangka nganimpa Nuu kalu nganpa payirni yangka nganimpa “Like pina manta nganpa yungurnalu pina jarri” nuwu kalu nganpa yanirni yangka japirni nganimpa.

True we learned proper in them days, and we are strong but nowadays young people don’t come to us and ask us, “Teach us so that we can know.” They don’t come and ask us, nothing.

Thomas Jangala Rice (c.1938–)

Thomas Jangala Rice was born in 1938 and grew up around the region of Mount Doreen Station to the west of present-day Yuendumu. He learned traditional hunting skills during this time and worked as a drover for the cattle station as a young man. He is kirda for the Country around Mikanji and the Ngapa jukurrpa, which is important to this region. As a young adult, he moved into Yuendumu with his two promised wives and has had an important role in his community ever since. Later in his life, he married Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan; together, they had an important role in the Warlpiri Youth Development Aboriginal Corporation’s Jaru-pirrjirdi bush trips. Jangala and Egan worked closely with Georgia Curran on the Warlpiri Songlines project between 2005 and 2008, shortly before Egan’s untimely death in 2009. Jangala has worked as a police aid and tracker with the Yuendumu Men’s Night Patrol and at the school, teaching traditional culture. He has had roles on the Yuendumu Council, Central Land Council and the Warlukurlangu Art Centre, through which he was central to the refurbishment of the Yuendumu Men’s Museum in 2010.

Barbara Gibson Nakamarra (1938–c.1995)

Barbara Gibson Nakamarra, born in 1938 in the Tanami Desert, was settled at Yuendumu as a young girl and married with her sister Beryl to Tony Japaljarri Gibson. She worked at the clinic and was moved again to Lajamanu, where she became a leading authority on rituals. In the 1980s, the family spent much time at the Kurlurrngalinypa outstation, where they were asked to re-enact their hunting–gathering life for a Japanese Museum crew. She helped B. Glowczewski with many translations for the Dream Trackers CD-ROM (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2000) and started to paint in 1986, exhibiting in many galleries. One of her paintings was presented in a touring exhibition in France (Glowczewski, Yapa. Painters from Balgo and Lajamanu catalogue, edited by Baudoin Lebon, 1991) and the Lenz Culture Institute in Austria (Zeit: Mythos Phantom Realität, Springer, 2000). After her husband’s death, she went to live in Tennant Creek and Kununurra, where she continued to paint. She passed away in the mid-1990s.

1 Nancy Munn (1973, 196, 200–3) mentioned a night ceremony she recorded, but this was a restricted men’s ceremony (parnpa), combined with a berry dreaming and events unrelated to anything mentioned to me in connection with the ceremony described here, although the kirda were of the same patricouple.

2 Long Paddy Jakamarra saw the ceremony during the period that Wally Langdon was superintendent (several people mentioned this). It was held near the Kirrirdi Creek turn-off beside the Alice Springs–Vaughan Springs Road. Long Paddy said he had also seen it at Mount Doreen Station after the war, when it was organised by BulBul and Wally Japaljarri, but maybe I misheard this and it was before the war; otherwise, this would mean it was held very close to the early Yuendumu one.

3 In an online video, Otto Sims, the son of Paddy Sims (the promoter of this ceremony), who was 12 at the time this ceremony was held, commented that “we don’t perform that ceremony any more but we do tell stories to our young people” (Sims 2017).

4 The Warlpiri orthography has changed since Ken Hale transcribed the tape; with the help of Georgia Curran and David Nash, the transcript has been converted into the current orthography.

5 The Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary (Laughren et al. 2022) defines rilyi as the shavings made when a man scrapes smooth a boomerang, leaving the bark and wood in small pieces. Rilyi must be differentiated from kukulypa headband decorations that are used in circumcision ceremonies. Kukulypa decorations keep the shavings attached to the stick. The Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary gives several meanings for kukulypa. The first is multiple individuals of a kind in close proximity to each other, thus forming a unit. It is also used to refer to when men go together in an armed group. “Kukulypa is when they pile together sticks, like those short small ones – like of Whitewood or Witchetty – that they gather together. Then they put the bundle on their heads, and then they go off – that is how the armed men travel – with bundles. Many of them.” This is slightly ambiguous but probably means that people embarking on revenge parties put these shaved sticks into their headbands.

6 During the first days of the ceremony, these objects represented boys as babies; the horizontal orientation of the objects reflected them at the stage when they were carried by their mothers in coolamons. Later, the objects were held vertically, marking the growth of the babies into young boys – all this in the care of the men.

7 There was a lot of hair string at the ceremonial ground, one ball made from the hair of the two domesticated camels at Yuendumu owned by Thomas Rice.

8 It had originally been planned to finish the ceremony on Sunday but because some men had driven to Alice Springs for alcohol, it was decided to finish the ceremony before they returned as it was feared the people involved might disrupt the ceremony.

9 Peter Japaljarri (pers. comm. 1972) to Nicolas Peterson.

10 On another day, Banjo mentioned that there was a “big wulpararri hail stone” (i.e., “Milky Way manifestation as a stone”) at Pirilyi near the Western Australian border, which is broken in half. After this happened, the ancestral man travelled on to Ngarrkakurlungu.

11 See Meggitt (1962, plate opposite page 44, 122) for reference to Wally.

12 In August 1967, myself as anthropologist and Roger Sandall as filmmaker working for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (now the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies) filmed several men’s rites at Kunajarrayi. The most important rite was Wally’s celebration for the site. It had particular significance for all present because of his great age, which made it clear that it was the last time he would do this. The resulting film, Walbiri Ritual at Gunadjari (1969), is not for public viewing but is archived at the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

13 Although my notes have this man at ninth position, it is quite clear from the photograph that he was in eighth position given his size relative to Arthur Japanangka.

14 The numbers in this column refer to the actual place in the sequence of verses sung when this verse was sung for the first time. The actual sequence of songs sung is listed at the bottom of this table. While 143 verses were sung, there were only 22 different verses. Most verses were sung a number of times at different places in the overall sequence.

15 The numbers in this column refer to the actual place in the sequence of verses sung when this verse was sung for the first time. The actual sequence of songs sung is listed at the bottom of this table. While 143 verses were sung, there were only 22 different verses. Most verses were sung a number of times at different places in the overall sequence.

16 David Betz’s film Singing the Milky Way (2006) is an introduction to Aboriginal art and the Dreaming via a biographical essay on Paddy Sims. The film was made in the early 2000s. and includes Figure 3.5. At the end of the film, Paddy says that he wants the video/DVD to keep being shown after he has died to keep the knowledge of the Munga ceremony alive.

17 David Nash (pers. comm 2021) has pointed out that Venus, usually identified as the Evening Star, would be in the west so it is not entirely clear which star Long Paddy Jakamarra had in mind. Nash provided the following table of the dates on which Venus becomes most clearly visible ordered by month so the approximate link with the winter solstice is evident. David Nash provided the following table of the dates on which Venus becomes most clearly visible ordered by month so the approximate link with the winter solstice is evident.

Morning 1961 Jun 20 Evening 1967 Jun 20

Morning 1953 Jun 22 Evening 1959 Jun 23

Morning 1945 Jun 24 Evening 1951 Jun 25

Morning 1980 Aug 24 Evening 1943 Jun 28

Morning 1972 Aug 27 Evening 1978 Aug 29

Morning 1964 Aug 29 Evening 1970 Sept 01

Morning 1956 Aug 31 Evening 1962 Sept 03

Morning 1948 Sept 03 Evening 1954 Sept 06

Morning 1940 Sept 05 Evening 1946 Sept 08

Morning 1975 Nov 07 Evening 1981 Nov 11

Morning 1967 Nov 09 Evening 1973 Nov 13

Morning 1959 Nov 11 Evening 1965 Nov 15

Morning 1951 Nov 14 Evening 1957 Nov 18

Morning 1943 Nov 16 Evening 1941 Nov 23