4

Dreaming to sing: Learning and dream creation in the Australian desert

Barbara Nakamarra Gibson was born in the early 1930s in the Tanami Desert on the Warlpiri lands of her father. Her mother was a Mudburra speaker from the north-east. At the time, Aboriginal people of the region were still maintaining their semi-nomadic way of life, travelling in small families from water point to water point and gathering in large numbers on certain sites for initiations, funeral rites and land-based ceremonies celebrating the jukurrpa, totemic ancestors who presided over the formation of landscape features and their renewal. Her father had inherited from his own father a spiritual connection with the Janganpa (Possum), Yarripiri (giant Taipan snake) and Wampana (Wallaby ancestors associated with several sacred sites in the Granites region and for which he was the ritual leader). Barbara Gibson had inherited from him and her paternal aunts the role of ritual owner, kirda, for the Yawakiyi (Black Plums) and Ngurlu (Edible Seed) jukurrpa, the names of the ancestral beings who had accompanied the Possum and Wallaby heroes, respectively, on their epic journeys.

B. Gibson1 said that her lips and those of her sisters became blackened when the plums became ripe, a sign of their spiritual connection as kirda to Black Plum jukurrpa totems. All the jukurrpa watched over the people at the sites that had formed during their own jukurrpa journeys. To maintain the reproduction of the species and their proper balance, men and women had to follow the Law: hunting rules, promised marriages and the totemic rites on associated sacred sites. Like all other Warlpiri people, Barbara was said to embody a spirit-child (kurruwalpa) left in the earth by the jukurrpa and who had passed on her first name, Nakakut, given to her by the Yawakiyi (Plum) at Rirrinjarra, a water source in the rock formed by the tears of the Yawakiyi Plums, who had lost some of their companions in a battle with the black sugar-leaf corkwood tree (Parrawuju).

The spirit-children kurruwalpa reveal their future birth, their identity and their place of conception in a dream that the mother, father or another loved one has before the birth of the child; sometimes, the child embodies a jukurrpa different to that inherited from his or her father because the spirit-children are said to “catch” their parents when they move on other people’s territories. Nakakut’s childhood was full of these stories of a desert of infinite forms, matters and spirits. As soon as she learned to walk, Nakakut began to read the ground for all the signs that allow her to orientate herself: bird tracks indicating the proximity of hidden water sources, lines of ants piling up the grains of acacia seeds that the women then collect to make seedcakes, cracks in the soil revealing the underground presence of yams or other tubers, the texture of the earth and the animal droppings that indicate lizard burrows or small marsupials.

Nakakut grew up in the region around the sacred rocks at the Granites, an area that experienced two gold rushes in the first half of the 20th century. Suffering from drought, Warlpiri people were also attracted to the region because the ceremonial site at Yarturluyarturlu had water sources that dried up less than others. The miners complained about the influx of Aboriginal people. The government set up a ration depot there, which was quickly overwhelmed by the demand and miserable conditions of the Aboriginal people.

This population was moved to a reserve in the south in the late 1940s: Yuendumu. There, Nakakut and her sister married the same man they had been promised to at birth. They worked at the clinic and had several children. Hundreds of people were settled there. Conflicts ensued, with spears, boomerangs and fighting clubs. To relieve this overcrowding, the government decided to create a new reserve. The chosen site, Hooker Creek, was in the territory of the Gurindji tribe, but a number of Warlpiri were taken there, including Nakakut’s family. Some tried several times to walk the 600 kilometres of desert separating the new reserve from Yuendumu. But, each time, they were forcibly brought back. In 1967, all Aboriginal people in Australia benefited from a referendum that granted the federal government the right to legislate for Aboriginal people across the country. Soon after, the residents of the reserve were able to elect their first town council and replaced the name Hooker Creek with a traditional name: Lajamanu (Meggitt 1962; Munn 1973).

I arrived in Lajamanu in 1979. The Warlpiri had just won a land claim over part of their ancestral territory and were preparing to reoccupy places that had been inaccessible since they were sedentarised2 at Yuendumu and Lajamanu (Peterson et al. 1978). Nakakut camped with her husband and three of her sisters on the edge of the women’s camp. The mother of a 20-year-old son in initiation, she regularly participated in female rituals, singing, dancing and having her body painted. But, because she was still breastfeeding her youngest son, she sometimes had to interrupt these ritual activities to take care of him. I returned four years later, and she had become a businesswoman and caretaker of rituals, leading songs and dances. Her husband had used materials from an old windpump to build a few tin houses on their ancestral land, located 100 kilometres east of Lajamanu. The family camped there and returned once a week with an old tractor to stock up at the Lajamanu store.

By the early 1980s, the search for gold had resumed in the Tanami Desert, with the sophisticated equipment of open pit mines. The land title obtained by the Warlpiri granted them the right to an income from the region’s mineral resources. To undertake explorations and exploratory trenches, interested companies had to negotiate with the Aboriginal people recognised as the traditional owners of the region. Sometimes, the traditional owners objected to exploration in certain places they wished to protect for religious reasons and sought their protection in the event that minerals were found. The area of the sacred site at the Granites, for which Nakakut’s father had been the owner, was the subject of a request for exploration by a mining company. The knowledge she had inherited from him then took on an unforeseen importance.

The owners and rights holders for land and its associated totems are determined by a series of traditional rules. First, the care of totems and associated sacred sites is generally transmitted among the Warlpiri within the father’s patrilineal clan. Sometimes, when a child is raised by an adoptive father, it is the land of the adoptive father that they will inherit. The most important clan is the one that initiates the child and in which all men have paternally inherited responsibilities to the jukurrpa. Due to the sedentarisation of Warlpiri people and their dispersal to different communities, the determination of the rights holders for a place subject to an exploration application requires the gathering of the traditional owners for meetings to negotiate with the relevant mining company. At such meetings, some representatives often mention the name of a person forgotten in the list of rights holders due to their distant residence. Thus, mining meetings are an opportunity to reunite with close or distant relatives that may meet with not only people from Yuendumu (Dussart 1988) but also from other communities of the Warlpiri language area (Willowra, Ali Curang, Papunya) and neighbouring areas (e.g., Balgo, Kiwirrkurra), as well as those who now live in the camps on the outskirts of the towns of Katherine, Alice and Darwin. Sometimes, the Warlpiri even seek to find children who have been adopted by non-Warlpiri families as far away as Arnhem Land or by non-Indigenous families in Queensland or South Australia.

In 1984, when the site at the Granites was the subject of a mining agreement, hundreds of people felt concerned because it was a ceremonial site shared by several groups, many of whose members had grown up in the region. Everyone knew that the Granites site, Yarturluyarturlu, was linked to the Possum, but no-one seemed to know all the songs and dances that told the story of the journey. Two women from Lajamanu received new songs and body paintings for the Possum jukurrpa associated with this site in dreams and taught them to other women.

This innovation was based on a longstanding tradition of dreaming new verses of songs and episodes celebrating Dreaming ancestors. Such dreams did not have the status of creation but of remembrance of something considered “forgotten” from the repertories of the jukurrpa. After much discussion, the authenticity of these dream revelations was attested by the fact that the dreamers had sung the correct sequence of sites associated with the Possum jukurrpa prior to the revelations. Some Elders were somewhat embarrassed by the incorporation of these ritual elements into Warlpiri cultural heritage; indeed, they claimed to be the only ones who could celebrate the Possum, saying that women should celebrate another totem associated with the Possum’s travels. Nakakut knew all of the Possum story and knew how to sing this journey alongside that of the Yawakiyi (Plum). She taught this cycle of songs to her kin.

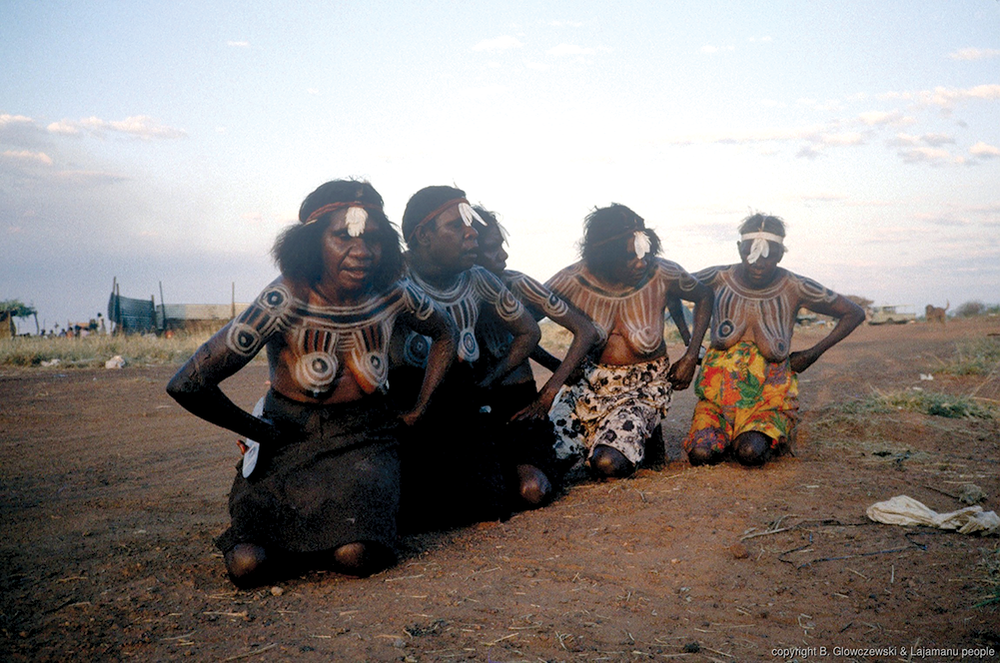

Shortly after Nakakut and her relatives sang the songs and danced for Yawakiyi jukurrpa (see Figure 4.1), one of her Warlpiri nephews emerged as the leader of the negotiations, knowing the best way to defend Lajamanu’s interests. At the time of the dream story presented here, Nakakut had just been recognised as one of the heirs to her father and was going to a mining meeting in Yuendumu community where she had lived with a double preoccupation: to prevent the destruction of the sacred site embodying the Possum ancestors and to ask for royalties from the exploitation of the minerals in the authorised region. A year later, the site would be protected by a large grid built around it, and alongside her sister and co-wife, she would receive a 4WD vehicle as compensation.

Figure 4.1 Barbara Gibson Nakamarra leading the Yawakiyi yawulyu dance.

Karnanganja manu Ngapa (Emu and Rain Dreamings) Told by Barbara Gibson Nakamarra

The other night, after Yakiriya told you [Glowczewski] the Emu story, I dreamed that I was sitting with her and the ancestral women. We were getting ready for a ceremony and a crowd of non-Indigenous people were taking pictures of us! My mother-in-law called out to me, very angrily, saying that she didn’t want non-Indigenous people to take pictures of us, but I said: “Don’t worry about it! They’re going to give us a truck.”

Indeed, the next day I had to fly to the meeting in Yuendumu, where I intended to ask the mining company for a truck as compensation for my ancestral rights for the Granites region, where they had interests. And the dream continued and revealed to me two new songs, one for the Yankirri (Emu) jukurrpa and the other for the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa. The songs were given to me by the wooden female Emu egg, the poor thing, who is alone now that you have her male companion. I made them both years ago for Yakiriya, that’s why she sang for me. She made me sick before my dream; I was cold without knowing why. Then, when I woke up, when I was on the plane, I felt very unwell. My husband asked me what was wrong and I replied that I was nauseous probably because I had not had breakfast. It is true that I was also nervous about speaking at the meeting. When I returned, I said to Yakiriya, “it was the ‘cracked feet’, the Emu, that made me feel so weird with this pain in my stomach. I took on the plane the two songs I had been given!”

Yakiriya knew because I told her my dream before I left. She is the one who with two other Nangala was singing in my sleep the new Emu song: karnanganja nangunangu mangurrularna mangurrungurru … Karnanganja refers to the parents of the egg, nangunangu is the waterhole they saw and the rest means that they sat there and then moved on. But as they sang Emu songs, all the women, myself included, were painted with the Rain/Water Dreaming designs.

Two Napanangka, Betty and Nyilirrpina, stood up the nullanulla (mangaya) imbued with ritual power. They erected it on the spot where the Emu and his wife covered their eggs, near the huge waterhole formed by the Initiated Man (Ngarrka) Dreaming that belongs to my husband. So I danced with the other women and we sang the new Rain/Water song: murraninginti kutakuta jurdungku jurdungku luwarninya … murraninginti means on the other side: that is, the west in relation to the east where the Emu travelled through; kutakuta is the storm and jurdu, the whirlwind. When it comes to luwarni “throwing”, it evokes the lightning strikes. Suddenly a cloud of dust rushed over us. A very powerful wind lifted the sand. The whirlwind covered us with dust. At the same time the rain began to fall. We sang and danced the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa song and got sent the sandstorm and were answered by the lightning bolts. These came from the sacred kurrajong trees of Lullju where the Rain/Water people brought them out when they filled the hole with water.

All the women ran for cover, not to their shelters, but under the dome-shaped foliage of the trees as we once did. The dance ground was surrounded by them. I shouted to both Napanangka, “Come! There’s too much wind and dust!” They continued to dance and to pull out the nullanulla they had erected. Still dancing, they then joined us to keep it safe.

That’s when I woke up in the middle of the night. I thought of our traditional ceremonies for the Emu Dreaming and the Rain/Water Dreaming. I thought of the two Nangala, now deceased, who were the most expert in leading the rituals. Custodians of the Rain/Water Dreaming in the Kulpulurnu region and of the Emu Dreaming with the two rockholes in the rock where the Emu and his wife discovered the miyaka (kurrajong fruit). These two women taught me their knowledge, like at school. The whole Kulpulurnu clan was my family because my father’s clan often visited them in times of drought. Thinking about those who have taught me, I had a lot of pain.

When I went back to sleep, I went back into the same dream. The sandstorm had subsided, the rain had stopped. We were only a small group of women: two Nakamarra, my sister Beryl and me, two Nangala, Yakiriya and another woman, a Nampijinpa and one of the two Napanangka, Betty Hooker, who led us. We danced for the big soakage Kuraja, which is near the town of Katherine. That’s where the Rain/Water Dreaming ends. There are black stones all around there. We call them “Black clouds”, an expression that also refers to the sea.

The Rain/Water Dreaming painted designs that we wore on our chests have turned into paintings of the Emu Dreaming. Napanangka said, “Now you will follow the Emu Dreaming to the salt water, the sea.”

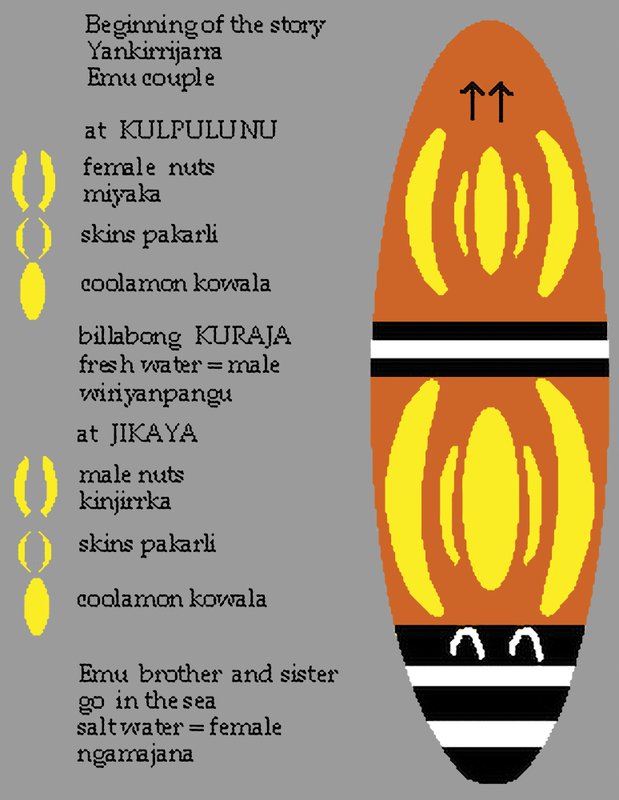

She took a large wooden dish, which she painted with the designs of the Emu Dreaming (see Figure 4.2). Dancing the Emu Dreaming, we found ourselves far north, in Jikaya, a site along this Dreaming trail, where there are many small waterholes. Still dancing, each of us dipped one foot in one of the holes and removed it as soon as she felt the water rise. It was funny, we tasted the water from all the holes with our feet!

Figure 4.2 Sketch of the Emu designs on the wooden dish. Image by Barbara Glowczewski.

All night we danced. At dawn, just before sunrise, the sea appeared, the salt water is black and vast. Napanangka said: “This is where you must end up, for here the brother and sister Emu went back into the ground.”

Each of us tasted the sea with our feet as we had done from the Jikaya holes. Huge waves rose and I was very scared. Suddenly we found ourselves again at the great black-stone swamp where the Rain/Water Dreaming ends. I saw a circular ceremonial ground and a crowd of ancestral women with unknown faces. With that, I woke up. The day was beginning. The women of the Dreaming had shown me, in its entirety, the ancient ceremony for Emu and Rain/Water by making me travel to the end of the two ancestral itineraries.

We perform this ceremony alongside men every four to five years to introduce boys to the Yankirri (Emu) and Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa and clans. We dance all night, as in my dream: before night falls, we sing the verses corresponding to the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa of Kulpurlunu. Around midnight, the songs and dances take us to Jikaya, the site of the Emu with the small waterholes that I saw in my dream.

Just before sunrise, we close the ceremony with the dance of the arrival of a brother and a sister Emu at the sea. There in the sea, the bodies of the two Emu children stay forever. It is their kuruwarri designs that inhabit the two wooden eggs that we paint on this occasion. At each ceremony, we paint them fresh in red with white markings similar to the footprints of the emus.

The same emu prints are painted on the ritual boards used to close the ceremony; they represent the parents of the two children, who did not go to sea but returned to the desert near Kulpurlunu, the site of the Rain/Water Dreaming. At one end of the dish, thick black lines represent the sea, undrinkable salt water that we call karnta (woman). These features are separated from each other by white lines, clouds. Two white arches on top correspond to the two Emu children. This part of the dish shows the end of the Emu’s journey.

The middle of the dish corresponds to half of the journey coinciding with the end of the Rain/Water Dreaming section at the large black-stone swamp, Kuraja. Two black features represent the drinkable fresh water that we call wirriya (boy). Between these features and those representing the sea, two long yellow arches depict the male kurrajong fruits of the Jikaya region of the Yankirri (Emu) jukurrpa, while on the other half of the dish, the same yellow arches depict the female fruits of the Kulpurlunu region of the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa. Between the yellow arches of the bottom (south) and the top (north), we draw a yellow oval corresponding to the dish (parraja), the hollow log that was used by the Emu parents to prepare the fruits. Around the two ovals, small yellow arches represent both the white skin of the fruit and the yellow powder from inside.

At sunrise, during the last dance with this painted dish, we insert the ritual pole into the ground, which is adorned in its upper part with black lines separated by white lines, representing (as on the dish) the sea and clouds. Then the respective owners of the Emu and Rain/Water jukurrpa bury the pole. We say that they bury the two jukurrpa until the next ceremony.

It is not enough to dream of a new song or a new painting and to say that they come from the ancestral heroes of the jukurrpa. In general, it is necessary to follow the corresponding route. In my case, the Emu egg, the little girl, led my pirlirrpa (spirit) through her jukurrpa so that I could identify the words of the song I had heard. In the same way the Rain/Water jukurrpa caused the sandstorm while I slept, confirming that the other song came from Lulju. Mungamunga (The Voices of the Night)3 have different ways of making us understand things. For example, the sandstorm erupted just after my mother-in-law’s anger that she didn’t want non-Indigenous people to take a picture of us. When I told her to let them do it because they’d give us a truck, she shouted: “The truck is for you! Not for me.”

Now my mother-in-law is a Nangala, an owner of the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa. Like other women, I was painted with this jukurrpa, though for the most part we were not the custodians. Perhaps that’s why she got angry and her jukurrpa inflicted the storm on us. Yakiriya told me that if I had received this nocturnal reminder of the jukurrpa tracks for Rain/Water and Emu and the revelation of two songs, it is because we do not celebrate these two jukurrpa enough.

By teaching women the new songs, we can revitalise the traditional ceremonies for Emu and Rain/Water Dreamings. It is true that here in Lajamanu, unlike Yuendumu, there are no longer many Nangala and Nampijinpa from Kulpulunu. The old ones have passed on and the others are too old or too young to dance. There are other Nangala but they come from the Lungkardajarra region and it is that part of the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa that they look after. The Nangala may be jealous and will resent me for trying to teach them a new song about their Dreaming. But that’s how it is, these Nangala have no ritual responsibility for the region I dreamed of. But me, I was initiated in my youth by several Nangala from Kulpurlunu. Also, I can direct this part of the celebration of the Rain/Water Dreaming with two other Nakamarra, Ngawalyungu and Puljukupari, whose maternal grandmothers were custodians of the same region.

As for my own maternal grandmother, she was the owner of the Rain/Water Dreaming from Pawu, that is to say for the final sequence of this route: her clan takes over the story looked after by the Kulpurlunu clan. My sons-in-law and my daughters-in-law come from both regions. Ngulajuku (That’s all, I’ve finished).

Some keys to the Warlpiri interpretive system

Ngulajuku is the conventional way to close every story, of a myth, a dream or a simple conversation. Nakakut Nakamarra’s dream and the comments she provides in her narration refer to two totemic routes that stretch close to the Granites for hundreds of kilometres from south to north: the Rain/Water jukurrpa that created many water points by flooding the plains and the Emu jukurrpa. Nakakut says that she dreamed of the Emu because, shortly before, she had helped me translate the myth of the Emu told by her friend Yakiriya, whom she saw dancing in her dream and who, in exchange for a blanket, had given me a ritual object – a painted wooden emu egg – that Nakakut had made for her. Nakakut wanted the exchange to be photographed. It should be noted that the dream begins with her mother-in-law complaining that too many non-Indigenous people are taking pictures of them.

Women make wooden eggs that represent the fertility of the emus and are also used in rituals to encourage human fertility. The Emu Dreaming tells, among other things, the story of a male who follows a female and falls in love with her; when he finds her, he travels with her, and they have many children, some of whom travel far with them, over a thousand kilometres, outside their Country, to the sea. The Emu story offers an alternative family model for the Warlpiri, who are often polygamous. In fact, the emu is monogamous; moreover, the male incubates the eggs alternating with the female who goes in search of food. Emus are associated with a variety of plant foods, including miyaka (Red Kurrajong) fruits. The Emu ancestor passed on the method for preparation to prevent the yellow powder that covers them from blinding someone who rubs it in their eyes. The exchange of roles continues when the emus are small. Nakakut, who had made two wooden eggs (see Figure 4.3) – a male and a female – comments in her account that it was the one who stayed alone with Yakiriya, “the female, the poor one”, who gave her the dream. The gift she gave me of a male egg followed two other gifts: in five years, I had received two baby carriers, although I had not yet had a child at the age of 28. When I gave birth to my two daughters, Nakakut’s efforts finally made sense as, through the classificatory kinship system, I called her ngati, mother.

Figure 4.3 Barbara Gibson, Yakiriya, Beryl Gibson and Barbara Glowczewski with the male and female wooden emu eggs. Image supplied by Barbara Glowczewski.

Since groupings and kinship relationships are very important in Aboriginal social organisation but also in dreams, it should be remembered that Warlpiri people practice a system of classification in eight subsections called “skin names”. The eight names are taken two by two to form different kinship relationships so that everyone in their social world uses a kinship address term with respect to all other members, even if there is no biological connection. Similarly, all non-Aboriginal people living on site – teachers, nurses or ethnologists – are bound to enter this kinship network, which is the keystone of social and ritual organisation.

Indeed, everyone is owner kirda of their Dreamings and assistant/manager kurdungurlu of the Dreaming of their mother and their spouse. But, when a ceremony takes place, all members of the present group are automatically divided into one or the other role according to their skin names. People who have the same skin name as the person who is the owner of the Dreaming in question consider themselves “skin brothers”; as such, all those who have the skin name in the position of “father”, “mother-in-law” or “father of the mother-in-law” of the real owners will also behave like kirda “masters/bosses” of the ritual (e.g., able to dance). All those whose skin name is in the “opposite” position – “father-in-law”, “sister’s child” or “brother/sister-in-law” – will be in a kurdungurlu position and will have to “work” for the ritual, either choreographing the dances, painting the ritual objects or preparing the ground (calling this job “worker”, “manager”, “lawyer” or “policeman”!).

The narrator of the dream is of Nakamarra skin. The owners of the Emu jukurrpa (as well as the Rain/Water jukurrpa) are Jangala/Jampijinpa for men and Nangala/Nampijinpa for women. A Nakamarra is mother of Nungarrayi and Jungarrayi, who marry Jangala and Nangala, respectively. The husband of a Nakamarra is Japaljarri, whose father is Jungarrayi, and mother is Nangala. Therefore, a Nakamarra woman is both “mother-in-law” for Jangala and Nangala (who marry her children) and daughter-in-law of Nangala, who is the mother of her husband. Therefore, she is a classificatory owner of the Emu and Rain/Water jukurrpa in two ways. In Nakakut’s dream, we find several Nangala: first, her mother-in-law, who wants non-Indigenous people to stop taking pictures, then her friend Yakiriya, who told me the Emu myth and gave me the egg made by Nakakut. The dreamer further offers us her interpretation of their presence in her dream.

She also says that, during her dream, she woke up thinking of two other Nangala, the deceased owners of the Emu and Rain/Water jukurrpa, who instructed her when she lived in the Granites region. Thus, she associates her dream with the time of her childhood, before sedentarisation in Yuendumu, the community where she was to fly the day after this dream to defend her land and rights. Nakakut emphasised that her own maternal grandmother, a Nampijinpa, was the owner of the Rain/Water jukurrpa from Pawu: that is, the final sequence of this route because her clan takes over the story celebrated by the clan at Kulpurlunu. She adds that these sons-in-law and daughters-in-law (thus Jangala and Nangala) come from both regions and that, unlike in Yuendumu, in Lajamanu where she now lives, the Rain/Water Dreaming of this region of the Tanami Desert is not celebrated enough. She notes that the responsibility is to reactivate her connections, which would explain the purpose of the songs she heard in her dream.

In her dream, Nakakut stages two Napanangka, the skin name in a position of “mother” with regard to her own. It turns out that Beatty Napanangka, whom she sees leading the line of dancers, was the boss of the Kajirri ceremony, which, five years before, during my first stay in 1979, had served as the framework for the collective initiation of the dreamer’s eldest son as well as that of his sister and her co-wife, another dancer in her dream. In the latter, the two Napanangka erect a sacred mangaya pole in the ground, then remove it by dancing exactly as the women do during the Kajirri ceremony. The dreamer evokes Mungamunga as the “Voices of the Night”, which has various ways of making us understand things by giving different identities to dream characters and creating meaningful situations like the anger that becomes (or turns into) a sandstorm. Mungamunga is also said to take the form of various ancestral heroines, including the two Nampijinpa sisters associated with the secret ceremony Kajirri, as the maternal grandmother of Nakakut and the unidentified dancer who accompanies the dreamer and the other women mentioned in their journey to the sea.

In her dream, the dreamer thus relives the mythical path of the original Rain/Water jukurrpa, as well as that of the Emu jukurrpa, as recounted by the ancestors since the beginning of time. The authentication of the real sites through which they travelled is necessary to confirm the authenticity of the two new songs that she dreamed, respectively, for Emu and Rain/Water jukurrpa. It is necessary to renew the spiritual link with the land by singing and dancing the songs and dances inherited from previous generations as much as the new songs and dances received in dreams, which are the means of keeping the tradition alive, attesting to the memory of the dream and the ancestral beings as effectively always in the making. We have seen by this example how dream, myth, reality and ritual feed into each other. The narrator’s self-reflection on her own dream helps us, through her clear perception and sense of humour, to understand that it is necessary to incorporate spoken narrative and elaboration to prevent confusion between dream, myth and reality. This distinction is often difficult to identify in Aboriginal statements (Poirier 1996), especially when, as in the case of dreams reported by Roheim (1988), the conditions of elaboration and the narrator’s reference system are not given to us. The important thing to remember is that if everything has a prior context (Glowczewski 1991c), the story is like an “audiovisual” reading, deciphering traces, signs seen and heard in dreams, landscapes and everything in the environment that leaves footprints, be it humans, animals, rain and wind or even unknown forces.

In 1994, 10 years after the story of the dream told here, Nakakut came to visit me when I had just given birth to my second daughter in Broome, a small town on the north-west coast located 1,500 kilometres from Lajamanu. By then, widowed from her husband and after long ordeals of mourning, she had left Lajamanu and settled with an Aboriginal man from Tennant Creek in Kununurra, a small town in north-eastern Western Australia, halfway to Broome. It was the first time she had seen the Indian Ocean from the west coast. I showed her a cliff that the Aboriginal people of the region, the Yawuru and Djugun, of which my husband is a descendant, associate with the Dreaming of a giant Emu, Garnanganja, the same name as the ancestral Emu from the desert. This one left his footprints, arrow-like, more than a metre wide in diameter, engraved like fossils, in several places in the reefs; these traces were identified by specialists as those of different species of feather dinosaurs. On this cliff is an escarpment with many small holes that fill with seawater at high tide. As we dipped our feet into them, a strange feeling invaded us both – I felt transported into the desert; she recoiled, hugging my daughter and refused to go any further, sitting behind the cliff to protect herself from the “power” of this place. For me, it was like deja vu of the dream she had told me 10 years before when, in her words, “tasting” the site full of small waterholes in the rock, she had found herself – in her dream – at the edge of the salt water, the Pacific Ocean where the myth of the Emu ends, as it was told to me by her friend Yakiriya. Was the fertility egg she had painted for Yakiriya and which she had given me related to the birth of my daughter on the edge of the Indian Ocean? The myth and the dream seemed to come together in my reality.

References

Dussart, Françoise. 1988. Warlpiri Women’s Yawulyu Ceremonies: A Forum for Socialisation and Innovation. PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 1984. “Viol et Inviolabilité: Un Mythe Territorial en Australie Centrale”. Cahiers de Littérature Orale 14: 125–50.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 1991a. Du Rêve à la Loi Chez les Aborigènes: Mythes, Rites et Organisation Sociale en Australie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 1991b. “Entre Rêve et Mythe: Róheim et les Australiens”. L’Homme 118(31.2): 125–32.

Glowczewski, Barbara (ed.). 1991c. Yapa. Peintres aborigènes de Balgo et Lajamanu/Aboriginal Painters from Balgo and Lajamanu. Paris: Baudoin Lebon Editeur (bilingual catalogue).

Glowczewski, Barbara. 2000. Pistes de Rêves. Art et Savoir des Yapa de Désert Australien (Dream Trackers. Yapa Art and Knowledge of the Australian desert) (bilingual CD-ROM). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Publishing.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 2002. “Mémoire des Rêves, Mémoire de la Terre: Jukurrpa”. In Rêves: Visions Révélatrices. Réception et Interprétation des Songes dans le Contexte Religieux, edited by M. Burger, 75–97. Berne: Peter Lang.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 2016. Desert Dreamers. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press/Univocal.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 2020. Indigenising Anthropology with Guattari and Deleuze. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Glowczewski, Barbara and Barbara Gibson Nakamarra. 2002. “Rêver pour Chanter: Apprentissage et Creation Onirique dans le Désert Australien”. Cahiers de Littérature Orale 51: 153–168.

Glowczewski, Barbara, Mary Laughren and Jerry Jangala Patrick. 2021. “Jurntu Purlapa: Warlpiri Songline for the Jurntu Fire Dreaming Site”. Cahiers de Littérature Orale 87: 229–38.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1962. Desert People. A Study of the Walbiri Aborigines of Central Australia. London: Angus & Robertson.

Munn, Nancy. 1973. Walbiri Iconography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Peterson, N., P. McConvell, S. Wild, and R. Hagen. 1978. Claim to Areas of Tradition Land by the Warlpiri, Kartangarurru–Kurintji. Alice Springs: Central Land Council.

Poirier, Sylvie. 1996. Les Jardins du Nomade. Cosmologie, Territoire et Personne dans le Désert Occidental Australien. Münster: Lit (avec le concours du CNRS [French Scientific Research Center], Paris).

Roheim, Geza. 1988. Children of the Desert II. Myth and Dreams of the Aborigines of Central Australia (Oceania Ethnographies 2). Edited and introduced by John Morton and Werner Muensterberger. Sydney, University of Sydney.

Stanner, William Edward. 1958. “The Dreaming”. In Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach, edited by William A. Lessa and Evon Z. Vogt, 23–40. Evanston, Illinois: Row, Peterson & Company (Australian Signpost, 1956).

Ruth Napaljarri Oldfield (c.1945–)

Ruth is an owner for the Ngarlu (Sugarleaf), Janganpa (Possum) and Warlawurru (Eagle) jukurrpa associated with the Country to the east of Yuendumu, near Mount Allan community. This is both Warlpiri and Anmatyerr Country. Ruth has lived in this area her whole life, walking through this Country as a young girl and then working as a housemaid and cook. When she moved into Yuendumu as a young adult, she was employed as a health worker. In her later life, she has become an internationally acclaimed artist, famous for her paintings of the Ngatijirri (Budgerigar) jukurrpa. Ruth lives in Yuendumu with her family and is a senior singer and custodian for many yawulyu songs.

Nganayi yangka kalalu-nganpa ngarrurnu kiyini, “Yiniwayi wajalu pina jarriya nyuntu-nyangurla yawulyurla”. Yunparninjaku kalarnalu start jarrija. Wariyiwariyirlarnalu nganimpaju learn jarrija, nganimpajurnalu pina jarrija. Kalalu-nganpa learn-i manu yangka pinarri manu kalalu-nganpa yawulyurluju. Warrki-jangka yangka kalarnalu yanurra after work, kalalu-nganpa yirrarnu “Nyuntulku kanpa do mani waja jalangurluju, nyuntulurlulku waja kanpa yunparni”. “Nyunturlulku kanpa do mani.” Kalalu-nganpa ngarrurnu kujarlu, yuwayi. Kalarnalu-jana nyangu-jala, pina jarrija kalarnalu nyanjarla. Yuwayi yangka kalarnalu-jana nyangu yawuly- kurraju nganimparluju. Learn jarrijarna Yurntumurla ngajuju. Pina-manuju pimirdi-nyanurlu.

They used to tell us “Learn your yawulyu (women’s songs).” And we used to start singing. Yes, we were taught yawulyu (women’s songs) at Wariyiwariyi (Mt Allan). Every day after work they used to paint us and then say, “You do it now, it’s your turn to sing now.” “You do it now,” they used to tell us, and we used to watch them dancing. I also learned later at Yuendumu … with my aunties …

Wurlkumanujulpa palka nyinaja, nganayiji Jilaliki-palangujulpa palka nyinaja. Ngularralpalu palka nyinaja, ngularra kalarnalu-jana nyangu yangka wirntinja-kurra. Kalalu-nganpa ngarrurnu, “Wirntiyalu nyurrurla-nyangurla waja yungunpa pina jarri waja nyuntu-nyangurla yawulyurla, kurdijiki-ngarnti nganayiki-ngarnti yawulyuku-ngarnti waja karnta-kurlanguku-ngarnti.” Kujarra kalalu-nganpa ngarrurnu. Yuwayi yijardu kalarnalu wirntija.

My old grandmother was here [in Yuendumu] and they [her and her sisters] were the ones who taught us. We used to watch them dance all the time and they used to tell us, “Dance your yawulyu (women’s songs) so that you can know how to dance when it’s time for kurdiji (big ceremony).” That’s what they used to say to us and then we would dance.

Yangka jalangurlangu kujalpalpa nyinaja no songlpalu yunparnu wiyarrparlu. Yuwayi wiyarrpa, warraja-jala ka ngunanjayani yawulyu-wati yalumpuju. Yuwayi warraja ka ngunanjayani. Panukarirli right mardalu wajawaja-manu wiyarrparlu, some-palarluju kalu wajawaja-mani, yuwayi nganimparluju karnalu mardarni-jiki-jala.

Some, these days, must have lost theirs, and others are losing theirs, but we are still holding on to ours. Today people are just sitting down and no songs are being sung. Yes, poor things, [but] the yawulyu is still around. Yes it is still present and people do know it.

Coral Napangardi Gallagher (c.1935–2019)

Napangardi was an important singer in Yuendumu until she passed away in 2019. She was an owner for the Mount Theo/Puturlu jukurrpa and kurdungurlu for the Jardiwanpa. In 2014, she published the book Jardiwanpa Yawulyu in collaboration with Peggy Brown, Barbara Martin and Georgia Curran. She worked tirelessly to teach younger generations traditional hunting skills, songs and dances. As a young woman, she lived with her husband and family at Wayililinpa outstation, to the south of Yuendumu.

Peggy Nampijinpa Brown (c.1941–)

Nampijinpa is a senior juju-ngaliya and leader for women’s ceremonial life in Yuendumu. She is kirda (owner) for the Yankirri (Emu) jukurrpa, and also identifies with the Warlukurlangu (Fire) and Ngapa (Rain) jukurrpa. She was awarded an Order of Australia for her work founding the Mt Theo Program (now Warlpiri Youth Development Aboriginal Corporation, WYDAC). She lives in Yuendumu and is often at Mt Theo looking after young Warlpiri people.

Nyampu kuruwarri yungulu panungku nyanyi. And ngurrara nyuntu-nyangu warringiyi-kirlangu karnalu-nyarra kijirni nyampuju yungunparla marlaja mardarni.

We want lots of people to see these jukurrpa. And this is your grandfather’s (father’s father’s) jukurrpa that I’m putting on you, so you can remember and carry it on.

Kuruwarriji tarnngangku-juku, kurdu karnalu-jana pina-pina-mani yangka, yungu kurdungku mardarni tarnngangku-juku ngula karnalu-jana pina-mani. Manu kuja new generation-ki karnalu-jana puta wangka, kuruwarri yungurnalu-jana jamulu yungkarla yilpalu yangka mardakarla nyanungurrarlulku.

The Dreaming is forever, we teach the young generations so they can learn and keep the culture with them. That’s why we teach them. And we would like to give our culture to the new generations to keep and to carry on.

Ngulaku, yinyirra karnalu-jana, yungulu-nyanu tarnngangku mardarni warlalja warringiyi-kirlangu. Manu juju yungulu-nyanu mardarni ngurrara-nyanu yungu mardarni warringiyikirlangu tarnngangku-juku. Nuwu wajawaja-manta! Yungulu langangku mani, ngukunyparlu yungulu mardarni. Ngajuju yapa kalarnalu nyuyu jarrija yangka ring place-kirra, kalarnalu nyinaja wali kalalu yunparnu. Wurra-wiyi-jiki, wurulyparlu kalarna-jana pina-nyangu. Kalarna ngulajangkaju pina yanu. Kalarnarla think jarrija yaliki yawulyuku kuruwarriki. Pinarni yanu kalarna.

So they can keep their grandfather’s (father’s father’s) country without losing them. To always have the knowledge of the country. People used to gather around at the ceremony place, they use to sing, then I would listen to them singing. Then I would go back thinking I should learn those songs, the yawulyu.

Kalalu yijardu yunparnu, kalarna-jana nyangu-wiyi, pingkangku kalarna yunparnu. Wirntinjakuju pina-jalalparna nyinaja. Wali yawulyulku yalumpu, pingkangku-wiyi, pingkangku-wiyi kalarna yunparnu. Warrajarlulku kalarna yunparnurra. Nyampu karna mardarni panu-kurlangu langangkulku, yangka kujakarna manngu-nyanyi. Milyapinyilki karna yawulyuju yalikari-kirlangu yalikari-kirlangu. Kalarnalu yangka jintangkarlu yunparnu.Ngulanya karnalujana marlaja mardarni nganimparluju. Ngula-warnuju kurdu-kurdukulku karnalu-jana yangka yunparni, pina-pina-mani karnalu-jana ngajarrarlulku, yilparnalu-jana jamulurra yungkarla or ngati-nyanurlulparla mardakarla.

They would sing, I used to watch and listen. Then I would sing softly, I already knew how to dance but I wanted to sing too. I can sing now, I have lots of songs, even other people’s songs. We used to sing together, that’s why we still carry it on, we want to teach our young ones to sing. We teach our young ones, so they can keep it and carry on with their mothers.

Kalalu-nganpa pina-pina-manu wirntinjarlu-wiyi. Wirntija-wiyi kalalu. Wali kalarnalu-jana nyangu, wali yangka kalarnalu jalajala jarrijalku, wirntijarralku kalarnalu. “Kari jungarni waja kanpa wirntimi ngurrju waja. Kuja wirntiya waja ngula karnangku pina yinyi.” Wali yijardu kalarnalu-jana rdanparnu, kalarnalu wirntijalku. “Jungarni kanpa wirntimi, nyunturlurlu marda kapunpa mardarni jujuju, Tarnngangku-juku kapunpa mardarni. Kurdijirla, yawulyurla kapunpa mardarni tarnngangku-juku. Yaparla-nyanu-kurlangu jaja-nyanu-kurlangu, nyampuju kanpa mardarni warringiyi-nyanu-kurlangu nyuntuku-palangu-kurlangu. Tarnngangku-juku ngukunyparlu manta!”

They used to teach us by dancing at first. They would dance first. We would watch them then we would want to try and we would dance. “Dance like this’’ — we would dance alongside the elders. They taught us to dance, and they used to say to us, “You are dancing the right way, you are dancing the right way, maybe you will keep all these ceremony songs. You will have them at Kurdiji times and women’s ceremony times. Ones belonging to your grandmothers (father’s mother, mother’s mother) and great aunts (father’s father’s sisters). You will keep this because it is your grandparents’ jukurrpa, keep it in your head forever!”

1 In Warlpiri, you cannot call someone by the same name as yours but instead use the expression narruku “same name” or another name. The original French version of this chapter appeared after the mourning period following B. Gibson’s passing. In this chapter, Glowczewski refers to B. Gibson either as “B.” (standing for her English name, Barbara), or by Nakakut, a diminutive form of her subsection name “Nakamarra”.

2 This refers to the government reserves in which Warlpiri people were forced to settle in the period post-World War II.

3 This translation for Mungamunga was agreed upon with B. Gibson for Desert Dreamers (Glowczewski 2016). These invisible forces can take the shapes of different totemic ancestors, deceased people and contemporary strange beings who can seduce men, women and children.