5

Minamina yawulyu: Musical change from the 1970s through to the 2010s

Minamina yawulyu are sung as a long series of verses by Warlpiri women1 living in Yuendumu and Lajamanu. Associated with the travels of a group of ancestral women who came out from Minamina,2 a site in the west of Warlpiri Country, the verses recount the travels of the Minamina women through a series of named places on their eastward journey. The verses sometimes refer to the women as walarajarra or karrparnu, the digging sticks they carry.3 Together with the associated Country, designs and dances, Minamina songs and stories are owned by Warlpiri women of the Napangardi/Napanangka patricouple, kirda who are supported by kurdungurlu from the Nakamarra and Nangala subsection groups, although nowadays the kurdungurlu category tends to extend more generally to include any of the few senior women who still have knowledge of how to perform the songs. This is one indication that these songs are highly endangered. We discuss six recorded performances of Minamina yawulyu songs performed across a span of five decades by groups of singers in Yuendumu.4 We compare these recorded performance instances to uncover some of the prominent changes, as well as stable features, across this period, illustrating a level of simplification and reduction in variability and complexity while maintaining the core essence of the songs and associated Country and the connections of individuals through inherited kinship rights.

The earliest known recordings of Minamina yawulyu songs were made by Rosalind Peterson in 1972 in Yuendumu with a large group of Warlpiri women who were painting up for a broader ceremony to be held that evening.5 Many records of other performances exist (e.g., the recordings made by Richard Moyle in Balgo in 1979 and referred to in Moyle 1997); however, for this chapter, we focus on performances recorded in Yuendumu or led by women from Yuendumu. Some of the verses on this recording are still sung today by current generations of Warlpiri women, many of them descendants of the singers in the recording. Today’s Minamina yawulyu songs are recognisably the same, using the same iconic tune and many similar lyrics referring to the landscape and the actions of the group of travelling ancestral women. Despite this (in many ways) remarkable level of continuity, there have also been significant changes to the performance contexts in which these songs are being sung, which have led to changes in selection of songs, musical setting and body designs.

In this chapter, we compare six recorded sets of Minamina yawulyu across a five-decade period. The recordings were made in three distinct blocks (1972, 2006 and 2016–2018). The earliest recordings were audio only, so they could not capture dancing and other important contextual features of the performance, although Rosalind Peterson took careful note of body designs and some other performative features in her field notes. Accordingly, our longitudinal analysis is limited to common features across the whole corpus. We will focus on 1) the song texts and overarching themes, 2) the ways rhythmic text verses are set to melodies and 3) the designs painted during the singing. We also make some general observations about the associated dancing.

To begin, we provide a general overview of the Minamina story and set out further details of the focal recorded performance instances, details of when and how they were made, and some observations of shifts in their performative features.

The story of the ancestral women from Minamina6

In 2006, shortly after leading the singing of Minamina yawulyu for an elicited recording, Judy Nampijinpa Granites, as senior kurdungurlu, told the following story.

Yinya kujakarnalu yunparni ngulaju karnalu Minamina yinya yunparni karlarra, ngurra nyanungu Minamina. Karntalkulpalu miirn-nyinaja Napanangka, Napangardi, wati-wangurla. Karntakarilpalu, yalumpujuku, karnta-patunya.

This one that we’re singing is really from Minamina. This song is the one from Minamina, way over to the west. At their home there at Minamina, the women are busying themselves. The women were really busy getting ready. All the Napangardis and all the Napanangkas – no men, there were only women there.

Karnta kanalyurr-pardinya kuja karrinja-pardija wurnaku-ngarnti. Milpirri mayi kalu-jana. Ngula-ngurlu nyampu wajarnalu ngurra-ngurlu nyampu-ngurlu yali-ngirli ngarna-ngurlu kuja karrinja-pardija. Yuwayi, yurna-kurralkulpalu nyampuju karrinja-pardijalpa, karrijalpa. Karrinjalu pardija ngarna7-ngurlu yinya-ngurlu.

The women stood up ready to travel. They rose up like rain clouds. From there, like that, they stood up to travel away from their home. Yes, they stood up to travel to another place from there, from their home, they stood up just like that.

Ngulalku karrparnu ready-manu. Yurnakulkulpalu wiyarrpalpalu yurnangkulkulpalu walarajarra-manu. Yurnangku ngula karnalu yunparni ngulaju kurrkara. Mirdijirrpi-jirrpi warlurr-wangkami ka kurrkara.

Then the digging sticks [the ancestral women] got ready to travel to another place – the dear things. Those walarajarra [the digging sticks/the ancestral women] [were going off to another place. We are singing about the desert oak country from afar. The bent-over [from the wind] desert oaks are making a sad sound.

Barbara Napanangka Martin is kirda for Minamina, her biological father’s country and jukurrpa.8 In 2017 she wrote down a further section to this story.

Yarnkajarnili Janyinki-wana jingijingi. Kujalu yukajarni Warrkakurrkukurra, ngunajayanirnili. Warrkakurrkurla ngunanjarlalu jukajuka-yirrarnu karrparnu. Kujaka yangka manja-wati karrimi Warrkakurrkurla.

They went to Janyinki and then went straight through. Like that they all came in together, to Warrkakurrku (Mala Bore). They camped there. They left their digging sticks standing up there. Those mulga trees are still standing there like that today at Warrkakurrku.

Wirntinjayanulu jingijingi ngunanjarla. Kakarraralu yanu. Wirntinjayanulu kakarrara. Aileron-kurralu yanu. Ngula-kurralu yanu. Karrkungurrpa-lpalu pina nyinanjarla yirraru-jarrijalku. Yirraru-jarrijalu ngulajulu yarnkajarni jurujuru, nganayi karrparnu. Yurrujurujuru kujalu yanu walyangka karrparnuju karlarra-purdayijala. Kakarrumpayi-jangkalu pina yanu karlarrakurra. Kujalu kulpari-jarrija, yarnkajalu karlarrakurralku. Kulpari-yanulu karlarrajuku yurrujurujuru, nganayi karrparnu. Kanunjumparralu yarnkajarra, yinyalu pina yanu Minamina-kurra ngulalu yukaja. Tarnnga-jukulpalu nyinaja yinyajukuju.

After camping there they danced along the way. They went eastwards dancing along. They went along past Aileron. After dancing they turned around and looked back [westward] and they all felt homesick, those digging sticks [the women]. They turned around, feeling homesick and then they all travelled back. They went past, back towards the west. They went all the way back to Minamina and they went back in there for good.

Minamina yawulyu: Six recorded performance instances

Warlpiri women’s yawulyu are typically performed in a number of different community-based contexts. In recent decades, opportunities to perform have expanded to include new contexts, such as intercommunity women’s meetings, showcases for openings and exhibitions, and staged performances (see Curran and Dussart 2023). When Warlpiri communities hold larger ceremonies, typically involving men’s singing and women’s dancing, beginning after sunset and going into the night, yawulyu are performed in the late afternoon in private women’s spaces. Several hours before sunset, women sing and paint each other up with associated designs. On occasion, brief dancing will follow, typically finishing within half an hour. During the painting up, slower tempo yawulyu songs are sung, with some of the same verses being sung at a faster tempo for the dancing.

As with yawulyu more generally, Minamina yawulyu song items consist of the varied repetition of a fixed text (verse) of two (or occasionally three) lines, repeated over a period of approximately 30 seconds to one minute, until the completion of a longer melodic contour. Each of these song items is followed by a pause and another song item based on the same verse before moving on to new verses in subsequent items (see Barwick and Turpin 2016; Barwick, Laughren and Turpin 2013; Curran et al. 2019; Turpin and Laughren 2013). Each verse references places, features of the landscape and/or the actions of the group of ancestral women as they travelled from Minamina.

As mentioned, the six different recorded instances we consider in this chapter were made during three periods over the last five decades: Recording 1 was made in ceremonial contexts over several days in 1972; Recording 2 was made in an elicited context in 2006; and Recordings 3–6 were made in various performance contexts in 2016–2018.

We acknowledge the many limitations of recordings as documents of a performance instance. None of the six recordings we will discuss is a complete documentation of an entire performance – even if it was, many aspects of the surrounding social context cannot be captured in recordings (even those supplemented by additional information in accompanying written notes). For example, for Warlpiri women, each performance nurtures the particular relationships between the singers, other people present, and the Country and jukurrpa to which they are connected. In these dimensions, each performance instance is unique, and neat comparisons cannot be made between them. Notwithstanding these evident shortcomings, this body of recordings is regarded as a valuable resource for contemporary Warlpiri performers because it represents some of the only detailed documentation of the songs performed in older performances. Therefore, analysing features that are captured well by recording can give us some valuable perspectives on change over time.

Recording 1: Painting up with Minamina yawulyu (June 1972; Peterson 1972–1973)

In 1972–1973, Rosalind Peterson lived with her husband, anthropologist Nicolas Peterson, in Yuendumu, where he was undertaking ethnographic fieldwork. During this period, she participated in a number of women’s yawulyu events and made notes and recordings on some of these, including a number of sessions on 24–26 June 1972, during which 14 verses of Minamina yawulyu were sung (for full details including the names of the singers, see Peterson 1972–1973).9 R. Peterson also made detailed notes about the participants and their relationships to each other, as well as sketching in coloured pencil the designs painted on the women’s chests and stomachs while they were singing.

In 2007, Curran, Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan and Thomas Jangala Rice listened to these recordings during a visit to Canberra and wrote down the words of many of the verses. Rice was kurdungurlu for Minamina because it was his mother’s jukurrpa and Country; thus, he knew the songs well from hearing them sung frequently by his mother when he was a child. More recently, Barwick, Martin and Curran have reviewed these recordings with senior contemporary singers and kirda for Minamina, particularly Lynette Nampijinpa Granites (senior singer), Connie Nakamarra Fisher (senior singer), Elsie Napanangka Granites (kirda), Geraldine Napanangka Granites (kirda) and Valda Napanangka Granites (kirda). In part due to the poor sound quality at parts of the old recordings,10 but also due to shifts in knowledge and difficulty in understanding the “hard” language used in these songs, these sessions raised many questions within this group. Only a few of the verses were recognisable, and most were unknown by the current singers of Minamina yawulyu, although L. Granites was able to identify a number of keywords in the songs.

Recording 2: The Warlpiri Songlines project (December 2006; Curran and Egan 2005–2008)

In 2005–2008, Curran and Egan worked together with a group of senior female singers to record and document various yawulyu for the “Warlpiri Songlines” project.11 On 18 December 2006, Judy Nampijinpa Granites (older sister to Lynette Granites and grandmother to Geraldine, Valda and Elsie; see Granites’ profile) led the singing of a Minamina yawulyu song set that was recorded and archived with the “Warlpiri Songlines” collection at AIATSIS. Judy had good knowledge of Minamina yawulyu because not only had she been a main leader for women’s ceremonies in Yuendumu over many decades but also her husband was kirda for this jukurrpa (for further details on Judy’s role as female ritual leader, see Dussart 2000).12 She had the strong support of seven other singers who together sang 15 verses of Minamina yawulyu. Following the recording, Judy re-listened to these songs and provided detailed stories about each, unpacking their meanings. The stories were documented alongside the song texts in the book Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017, 11–34). Martin has played a key role in writing down these stories both as kirda for Minamina and due to her strong bilingual skills in writing both English and Warlpiri. As Judy passed away before we started making this book, Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites assisted Martin in interpreting the song texts and stories for the written representation (see Curran, Martin and Carew 2019).

Recording 3: Making the Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu DVD (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017)

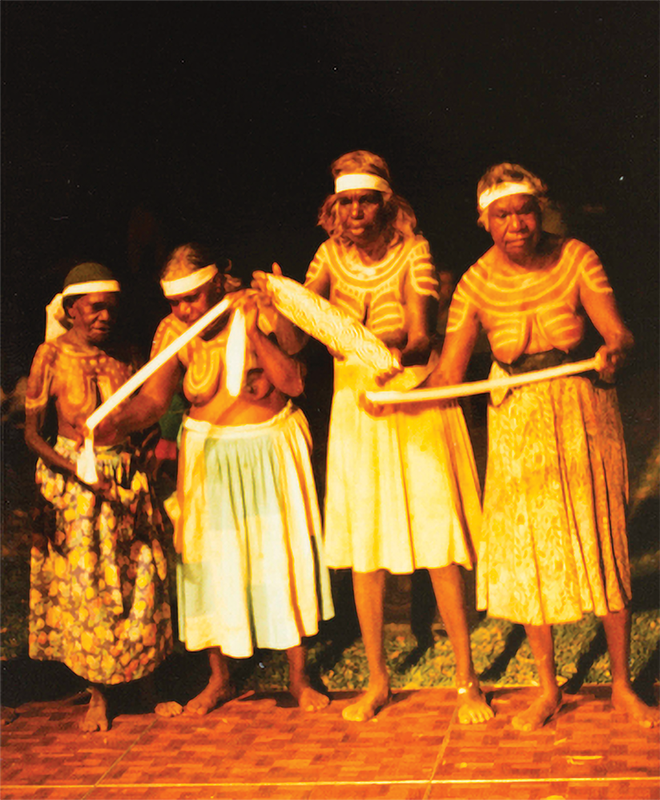

During the book’s development, a group of Warlpiri women decided they wanted to make four short films to showcase the dances for the yawulyu song series represented in the project for inclusion as a DVD accompaniment to the book Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya Kurlangu Yawulyu (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017). On 18 July 2016, a large group of Warlpiri women gathered at a women’s ceremonial ground at Mijilyparnta (Mission Creek) with filmmaker Anna Cadden. The group began the session by painting up four women who all had patrilineal kirda rights for Minamina yawulyu. Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites led the singing of four verses, supported by only three other women, including Coral Napangardi Gallagher, who had been an important and knowledgeable singer during her life but was very elderly when the recording was made.13 As part of the painting up-session, Granites also included a number of other verses of women’s songs associated with jilkaja, a ritual women sing to escort a boy who is travelling to a community for his initiation.14 Following the painting up, the women danced in a long line led by Martin to three different Minamina yawulyu verses (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Barbara Napanangka Martin leads the Minamina yawulyu dances for the film. Photo still taken from a video made by Anna Cadden, 2016.

Recording 4: Painting up at the Southern Ngaliya dance camp (Curran 2017)

Since 2010, Incite Arts and the Warlpiri Youth Development Aboriginal Corporation have collaborated with Warlpiri women to hold biannual dance camps where Warlpiri women gather to sing yawulyu and teach younger generations. These events are held over a long weekend at the beginning of the school holidays at different outstations near Warlpiri communities. In April 2017, a dance camp was held at Mijilyparnta (Mission Creek), attended by a large number of Warlpiri women who had recently been reviewing proofs of the songbook to be published later that year. In the book is an old photo of a particular section of Minamina yawulyu known as jintiparnta (a native truffle that grows in the sandhill country in cold weather) painted on Yarraya Napangardi, a much-loved yawulyu singer and kirda from Minamina and relative for many people in attendance. Peggy Nampijinpa Brown decided she would paint Cecily Napanangka Granites, Yarraya’s brother’s daughter (pimirdi), and therefore also kirda for Minamina, with the same designs (for further details of this event, see Curran 2020c). Peggy, as a senior kurdungurlu, painted Cecily while a group of women sang five Minamina yawulyu verses; however, they did not dance Minamina yawulyu later that evening as originally planned because Cecily returned back to Yuendumu for medical reasons.

Recording 5: Painting up with Minamina yawulyu for the book launch at the Northern Territory Writers Festival (Deacon and Turpin 2017)

In 2017, a large group of Warlpiri women travelled to Alice Springs to launch the Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017) book at the Northern Territory Writers Festival. On 21 May 2017, at a chilly morning hour, the group gathered at the Olive Pink Botanic Gardens and began to paint up. As the group planned to dance the Yarlpurru-rlangu (“Two Age-Brothers”) yawulyu in the indoor section of the Olive Pink Cafe, which involves the meeting of Minamina and Mount Theo ancestors, a number of women were painted up with Minamina yawulyu in an outdoor space. Three verses of the Minamina yawulyu were sung as two sisters, Elsie Napanangka Granites and Alice Napanangka Granites, were painted with Minamina designs. At the same time, a larger group of women were simultaneously painting up with Ngapa yawulyu designs, so it was difficult to identify the number of Minamina yawulyu items performed for the painting up. Another dancer, Audrey Napanangka Williams, was painted with Mount Theo designs and danced as the Mount Theo ancestor. A growing crowd emerged to watch as the group painted up and then followed them as they danced into the room (see Figure 5.2). One Minamina yawulyu verse was sung while they danced, followed by an additional verse specific to the meeting up of the two different ancestors from the different Country at Minamina and Mount Theo.

Figure 5.2 Two sisters, Alice Napanangka Granites and Elsie Napanangka Granites, dance as two ancestors from Minamina, who meet up with their age-brother from Mount Theo, danced by Audrey Napanangka Williams. Photo still taken from video footage by Ben Deacon.

Recording 6: Painting up with Minamina yawulyu for a performance at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Canberra (Macdougall and Duke 2018).

In 2018, when a group of 16 Warlpiri men and women travelled to Canberra, several dances of Warlpiri women’s yawulyu and men’s purlapa were performed at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy (for details of the purlapa, see Curran and Sims 2021). The Minamina group planned to dance the Yarlpurru-rlangu yawulyu with Barbara Napanangka Martin and Alice Napanangka Granites painted up as two Minamina ancestors and Jean Napanangka Brown as a Mount Theo ancestor (see Figure 5.3). These three women danced together while the rest of the group of women sang a yawulyu associated with the meeting of these two ancestral beings.15 During the painting up of Martin and A. Granites, four verses of Minamina yawulyu were sung.

Figure 5.3 Barbara Napanangka Martin and Alice Napanangka Granites dance as the Two Age-Brothers from Minamina with Jean Napanangka Brown as the Age-Brother from Mount Theo. Photo by Georgia Curran.

Made across varying contexts (public, private, women’s only), the six recordings involved different women as song leaders, singers, dancers and in other participatory roles – all factors that influence the song choices and other features of the performance. Table 5.1 sets out a brief comparative summary of some of these features, including the reason for the performance, the number of singers, the overall duration of the event, the number of verses recorded and the number of song items recorded.

Some features in Table 5.1 may be interpreted as evidence of shifts in performance practice over time, while other variations may seem to be due instead to shifting performance contexts.

Table 5.1 Comparison of features of the six recorded performance instances.

| Performance event and date | Reason for performance | Number of participants (singers in brackets) | Overall duration | Number of verses | Number of items recorded (av. = average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recording 1 (1972) Women’s ceremonial event (1972) |

Women’s painting up prior to a larger ceremony (women-only event) | 42 (of whom unknown number of singers) | 10 hrs approx. over 3 days (3 hrs recorded); painting up and some dancing | 14 | approx. 80 items per hour (8–25 items / verse) |

| Recording 2 (2006) Elicited recording (2006) |

Documentation purposes (women-only event for public dissemination) | 8 (7) | 35 mins | 15 | 42 items (2.8 items / verse) |

| Recording 3 (2016) DVD painting up and dancing (2016) |

Documentation: video footage to be included with yawulyu book (women-only event for later public dissemination) | 23 (4) | 30 mins painting up plus 12 mins dancing | 4 + 3 (not including jilkaja songs) | 17 items painting up (av. 4 items / verse) |

| Recording 4 (2017) Southern Ngaliya dance camp (2017) |

Teaching and learning: women’s camp focused on teaching young girls (women-only event) | approx. 50, including many younger women and children (4) | 19 mins painting up | 5 | 24 items |

| Recording 5 (2017) Northern Territory Writers Festival performance (2017) |

Public performance: to launch the yawulyu book | 18 (6) | 20 mins painting up (mixed yawulyu) plus 8 mins dancing | 3 + 1 | 6 audible items (av. 1.5 items / verse) |

| Recording 6 (2018) Aboriginal Tent Embassy performance (2018) |

Public performance: showcasing Warlpiri songs to Canberra audience | 12 (3) | 20 mins painting up and 10 mins dancing | 4 | 17 items (av. 4.25 items / verse) |

Reasons for performance: There is a trend in more recent times for performances of Minamina yawulyu to be more public. While many performance instances were held in women-only contexts, in recent years, younger Warlpiri women have often been the target audience for teaching and learning activities (e.g., at dance camps), as well as for documentary purposes (e.g., 2006 elicitation, 2016 DVD production). However, in the latter case, the performances were also designed to include non-Warlpiri female and male public audiences. Two events, the 2017 Northern Territory Writers Festival book launch and the 2018 Tent Embassy performance in Canberra, were explicitly designed for non-Warlpiri audiences that included both men and women.

Number of participants: In 1972, a large number of women participated, although we do not know exactly how many of these were singers. R. Peterson’s fieldnotes (1972) list 42 performers, including a large group of kirda from Minamina, each of whom had to be painted up as the verses were sung. By contrast, in the 2016–2018 performances, only 2–3 kirda were painted up, and there were only 4–5 singers, even in larger-scale events, like the Southern Ngaliya dance camp. This represents a significant reduction in the number of singers compared to the unknown but certainly large group of singers audible in the 1972 recording, and even the 12 singers who participated in the 2006 documentation session.

Overall duration of performance: Together, the above factors resulted in a much shorter overall duration of more recent performances – under an hour, compared to more than 10 hours in 1972. The more public nature of some recent performances may also have had an effect on overall duration because performers often faced the pressures of external timeframes.16

Number of verses and their repetitions: Flowing from the above observations, recent performances held in 2016–2018 demonstrate a dramatic reduction in the numbers of verses sung compared to the older recordings of 1972 and 2006, as well as fewer repeated items of each verse. In the 1972 recording, the same verse would be repeated over and over again (between 8 and 25 times) as each kirda was painted up with the relevant body design (see Appendix 5.2 for examples). The constrained time frames and the small number of kirda for the more recent performances appear to have resulted in less time being devoted to painting up (average four items per verse) due to not only the smaller number of kirda but also less elaborate or less extensive body designs (see further below).

As we will illustrate in this chapter, these factors have a major influence on the ways in which Minamina yawulyu are being performed and passed on to younger generations.

The language and overarching themes of Minamina yawulyu

As is the case for many songs sung by Warlpiri women, the words used in Minamina yawulyu require interpretation from knowledgeable singers. Ruth Napaljarri Oldfield explained of Minamina yawulyu that “this is hard language, not like some other yawulyu. Not everyone can understand these songs, only the really old women” (Ruth Napaljarri Oldfield, cited in Curran 2010, 106). As discussed elsewhere, this is not so much because the words are radically different from spoken words in Warlpiri (as is often the case for songs) but more because the specific connotations of words require bringing together complex knowledge from many domains, which is only fully known by the senior singers (Curran 2010, 114).

Singers in Yuendumu today have difficulty discerning (i.e., identifying the words being sung) and explaining the lyrics of Minamina yawulyu, contrasting them to other Warlpiri yawulyu (e.g., Watiyawarnu), which are described as “easy”. In 2021, senior singer Lynette Nampijinpa Granites was able to articulate some of the words of the songs on the 1972 recording so that we could write them down but could not expand significantly on their meanings. Nevertheless, in her discussion of the 1972 songs, she was able to identify some of the focal themes, many of which are also present in songs sung in more recent recordings, although some are not.

Theme 1: Swaying movement of the vertical figures

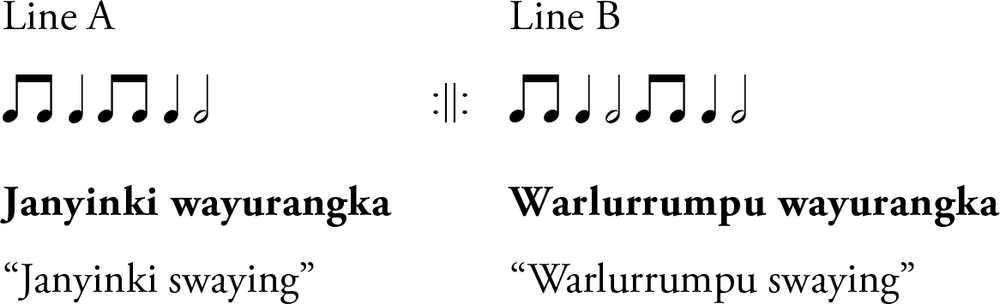

Listening to the 1972 recording in 2021, L. Granites identified dominant visual imagery of the Minamina yawulyu, evident in many verses sung in 1972, illustrated here in Example 5.1.17

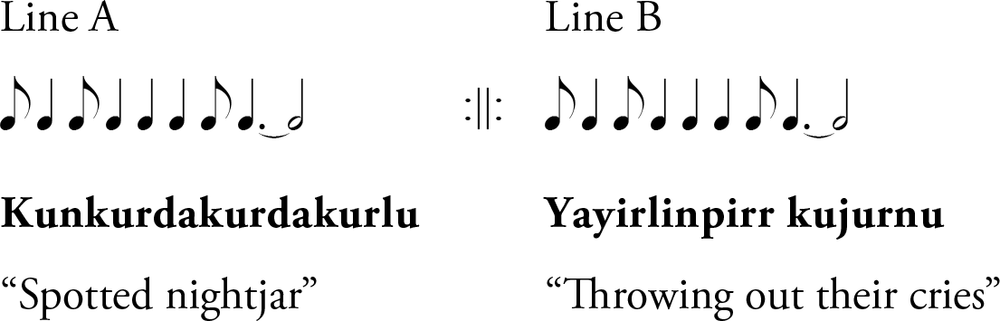

Example 5.1

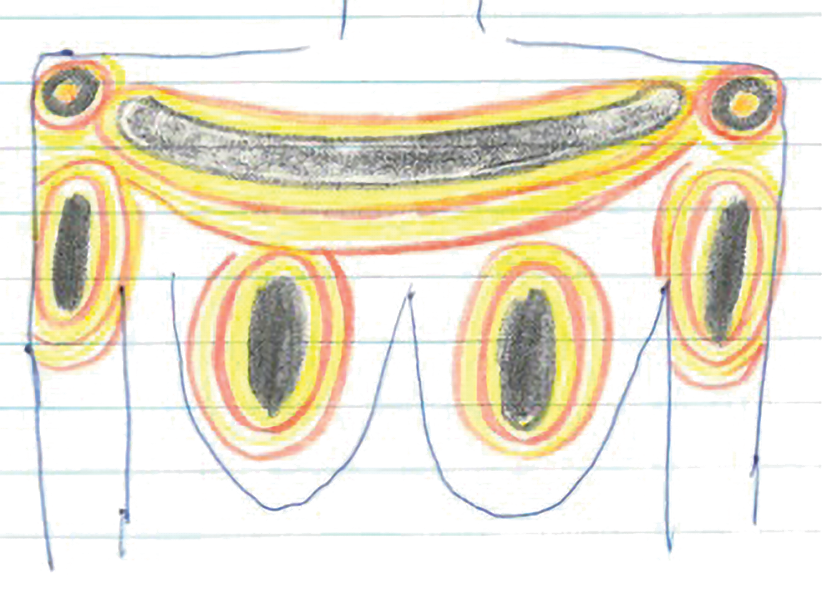

L. Granites was able to articulate the word wayurrangka (wa-yurr-wang-ka), which was tricky for others to hear because the syllables merged together in sung form and because the word does not appear in contemporary Warlpiri (e.g., Laughren et al. 2022).18 L. Granites explained that this referred at once to the swaying of the trees and the movement of long upright figures of the travelling ancestral women. This word is sung often in various verses throughout the 1972 recording but has since gone out of use and does not appear in verses sung in more recent performances. Nevertheless, the theme of long, skinny, vertical objects with a swaying movement remains as dominant visual imagery in the verses recorded more recently. Example 5.2 from the 2006 recording was also sung in the 2017 and 2018 public performances.

Example 5.2

In this verse, the word walarajarra was explained in 2006 by Judy Nampijinpa Granites as referring simultaneously to the digging sticks carried by the ancestral women, to the upright women’s bodies as they walked and to the desert oak trees that grow in the Country around Minamina (see Figure 5.4). This imagery is also reflected in body designs painted on women’s chests in the 1972 performances, which is now the main design featured in the 2016 and 2018 performances (discussed later in this chapter).

Figure 5.4 Minamina and the Country to the east are dominated by desert oak trees, symbolically representing the ancestral women as they travel and the digging sticks that they carry. Photo by Mary Laughren.

Theme 2: Ritual power or essence of the ancestral women and their Country

Another dominant theme still evident in verses from the 2016–2018 recorded performances is exemplified by the word minyira – literally “fat, lard, grease, marrow, butter, oil” (Laughren, 2022: 434) but metonymically referring to the women’s oil-laden headbands. The oil dripping from the women’s headbands as they dance symbolises their ritual power. In 2006, Judy Granites explained that minyira also meant the smell of the earth after rain, referring to the strong essence of the Country most prominent after rain (Young 2005).

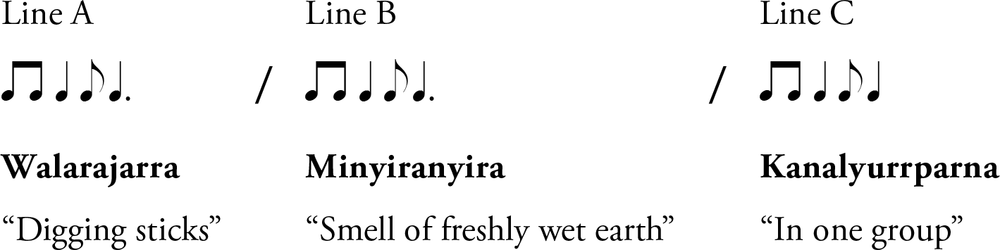

The word minyira (sometimes partially reduplicated as minyiranyira) appears in Example 5.3 (1972) and Example 5.4 (2016), as well as elsewhere in the corpus.

Example 5.3

Example 5.4

Theme 3: Place names

Across recent performances, verses centred on central place names for the Minamina jukurrpa are emphasised. This strong trend emerges in the telling of jukurrpa stories (evident in the story that began this chapter), as well as in songs for both Warlpiri men and Warlpiri women. The prominence of place names emphasises Country as perhaps the most essential aspect of jukurrpa and constitutes a core focus for many senior Warlpiri people in ceremonial performance. For example, the places Minamina and Janyinki are focal sites in the travels of the ancestral women, and these placenames feature prominently in song verses from across the five-decade period.19

Decline in songs with women-only subject matter and connotations

In the 1972 recording, songs on numerous other themes recur – themes that were drawn out by Egan and Rice, as well as by Granites.20 Many of these songs contain subject matter restricted to women, including content focused on female sexual desire and menstruation. Many of these verses cannot be published because knowledge of their content is restricted to a senior female audience, but there are some examples from the 1972 performance that can be discussed here, including Example 5.5.

Example. 5.5

For knowledgeable senior women, this verse alludes to the sexy way a woman walks when she has a baby in a coolamon tied around her shoulders and waist with the snake vine.21 This song can be used in private contexts as a yilpinji to attract a particular desired man, but a “light” interpretation of the verse (as in Example 5.5) allows it to be sung in contexts involving younger children, with emphasis placed on the movement of the group of ancestral women, rather than its sexualised connotations. Nevertheless, this song does not occur in the more recent performances (all of which are either public performances or events involving younger generations) and has likely been lost from the repertory known by current senior Warlpiri singers. Despite the women hearing this song recently on the older recordings, it has not been reincorporated into recent more open performance contexts.

Sexual content was similarly avoided at the Southern Ngaliya women’s bush camp in 2017, when Cecily Napanangka Granites was painted with the jintiparnta “native truffle” design. In this instance, the senior singers had requested a copy of the proofs of the forthcoming book from which to copy the design because they had not painted it for many years (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017). It was felt to be important to paint this design on Cecily as a way of carrying forward her specific relationship to her aunt (father’s sister), who featured in the photo in the book (for further details, see Curran 2020c). The senior singers noted that they had forgotten the particular yawulyu verses associated with jintiparnta. While hinting at the sexual connotations of this particular design, they sang open songs as they painted Cecily. Despite this event being a private women’s bush camp, there were many younger children and visitors for whom sexualised content was not appropriate.

Kurdaitcha birds: Reinforcing cultural values

A prominent theme throughout many yawulyu songlines is the sporadic appearance of ancestral figures in the form of birds who lustfully pursue groups of travelling women. These “kurdaitcha birds”, as senior Warlpiri women refer to them, are always of the wrong skin group for marriage to those of the group of women, and any resulting sexual liaisons lead to negative outcomes for the women, ranging from humiliation to death.

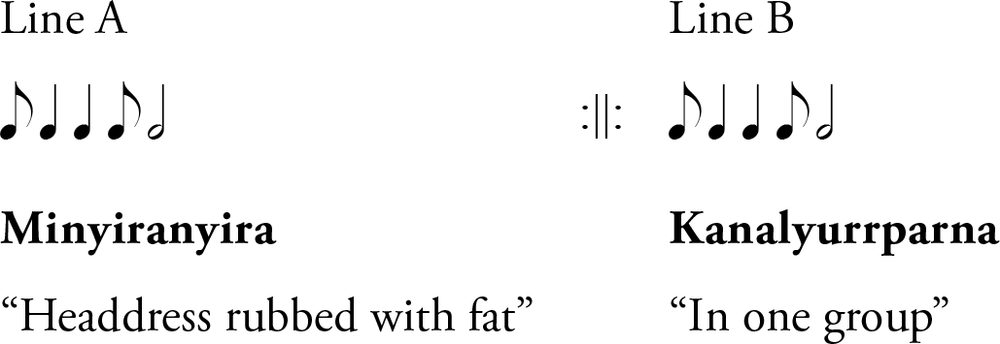

As discussed elsewhere, the presence of these birds in songs represents a fear of loss of particularly valued aspects of Warlpiri identity, notably “of connections to country, of traditional social organisation, of control over women’s sexuality, and of the gendered forms of sociality which have until recently typified Warlpiri life” (Curran 2020b, 128). Kurdaitcha birds are common figures in the verses from the 1972 and 2006 recordings; their significance is drawn out in deeper ways in the accompanying stories. Examples 5.6 and 5.7 are verses from the 2006 recording about the “Spotted Nightjar” bird – named in the songs as either yinkardakurdaku (Example 5.6) or kunkurdakurdaku (Example 5.7) – who pursues the group of women throughout their eastwards journey, flitting around them in the nearby bush and calling out repeatedly in the manner typical of this bird species (which is rarely seen but often heard).

Example 5.6

Example 5.7

Kurdaitcha birds like this do not feature as much in the more recent recordings from 2016 to 2018. This may indicate a possible classification of this type of cultural knowledge as inappropriate for broader public performances (e.g., women-only category). During the 2016–2018 period, the only occasions on which verses about the kurdaitcha bird were sung were women-only events: the DVD production and the Southern Ngaliya dance camp, despite both events being videoed for archiving and broader circulation. Example 5.8, sung in 2016 and 2017, is a version of Example 5.6 but uses the alternative name for the bird, “Kunkurdakurdaku”, as found in Example 5.7.

Example 5.8

While the pursuit of the travelling women from Minamina by the spotted nightjar bird is central to the jukurrpa story, it seems that these verses are now held to be inappropriate for the contemporary public performance settings in which Warlpiri women today perform yawulyu. In the final DVD production intended to be viewed by the general public, in the story told by Martin guided by Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites (transcribed earlier in this chapter), she chose not to mention this aspect of the story. Although the verse in Example 5.8 was sung, its surrounding story remained unexplained in this context. Instead, the singers chose to emphasise the named places through which the ancestral women travel.

Changes in musical settings across time

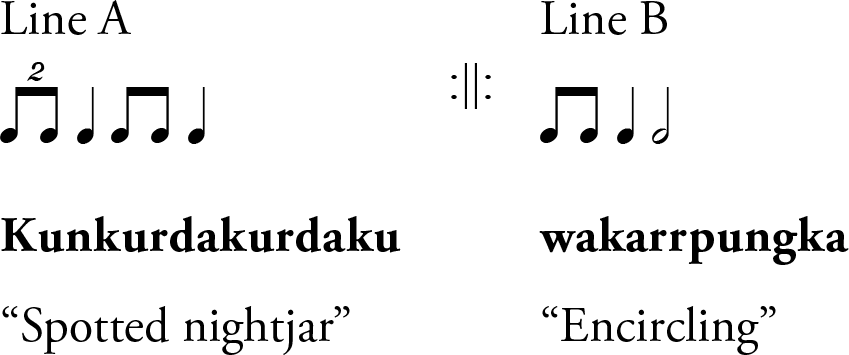

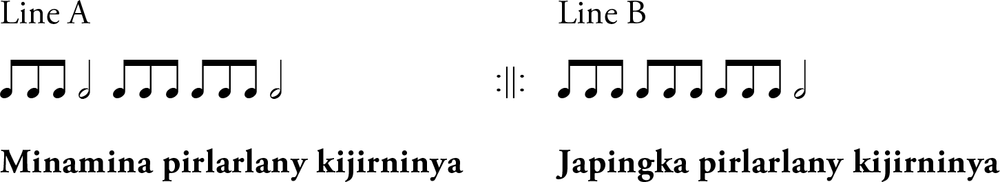

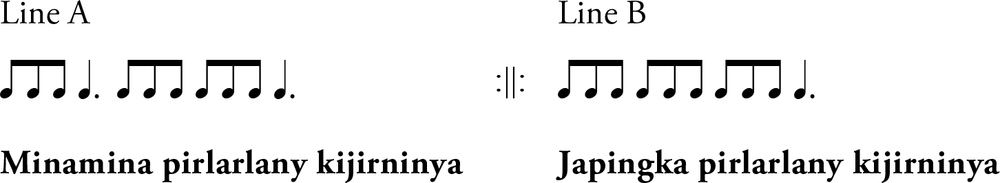

Only one verse, presented below in Examples 5.9A and 5.9B, occurs in all three periods covered by our sample. These Examples were recorded in 1972, 2006 and three of the four performances in 2017–2018.22 Usually performed as the first verse in the recording, it serves as an anchor to the focal site of Minamina, from where the group of ancestral travelling women begin their journey. By comparing the ways in which this verse has been performed across the performances, we uncover some shifts in the ways in which the rhythmic text of the verse is performed across the characteristic Minamina melody.

Contemporary shifts in setting of text-rhythm to melody: Comparing a verse performed across the five-decade period

It is normal in Warlpiri songs, as in other Central Australian songs, that each verse tends to have a fixed rhythmic setting (forming a unit often referred to as “text rhythm”). Example 5.9A shows the usual text-rhythm of the verse when performed for painting, as occurs in many instances across all five performances. In one performance at the 2017 Northern Territory Writers Festival, the verse was also performed for dancing, resulting in a change to the text-rhythm given in Example 5.9B.

Example 5.9A

Example 5.9B

While the text-rhythm of Example 5.9A can be classified as additive, with no regular pulse,23 the text-rhythm of Example 5.9B demonstrates a regular pulse, notated here as a dotted crotchet, and the dancers’ movements are synchronised by clapsticks beaten by the lead singer. Comparing the two settings, we can see that this regularity in the text-rhythm is achieved simply by reducing the duration of the long note to a dotted crotchet rather than a minim. We cannot be certain whether the use of this verse to accompany dancing is a recent innovation or was simply not previously recorded.

Another common feature of the Central Australian musical style is flexibility in text-melody layout – that is, the placement of the text-rhythm cycle onto the melodic contour characteristic of each song set (Barwick 1989; Ellis 1985; Pritam 1980; Turpin 2007b). The melodic contour typical of Minamina and used across all five performances uses five pitches, approximating to degrees 8, 7, 4, 3, 2 and 1 of a gapped major scale, presented in the order 78/4321/4321 (where slashes represent breaths separating distinct melodic sections). These pitches are relative rather than fixed – in the 1972 and 2006 performances, the tonic (final) is F, but in the three recent performances, the tonic is variously C, B flat and E flat.

In 1972, the oldest Minamina performance analysed, we can observe a great variety of text-melody layouts across its 17 consecutive items (see Appendix 5.1). We have already noted that in the 1972 performance, a far greater number of items was performed per verse than in recent performances, where only 2–4 consecutive items were typical.

One notable feature of text-melody layout occurs only in the 1972 performance. Text line reversal occurs where the text line pairs AA and BB are presented reversed on the melody in consecutive items. This occurs nine times in the 17 items of the 1972 performance but not at all in the later performances. This reversal of the melodic placement of the text draws attention to the flexibility of the musical system and may be an important educational tool for novice learners (Barwick 1990).24 By contrast, the later performances since 2006 all begin with the AA text line pair.

Another important variable is the overall duration of the song item. While the 1972 performance presents a minimum of two and a maximum of six melodic sections, with most being three or more, both items in the 2006 performance present four melodic sections (not counting the initial humming performed by the song leader Judy Nampijinpa Granites). By contrast, in the 2017–2018 performances the maximum number is three, with two or even one melodic section occurring on occasion. The duration of each section is relatively shorter also, with many sections presenting only two lines rather than the three or four lines commonly found in melodic sections in the 1972 and 2006 performances.

In summary, the constrained time frames of later performances have contributed to an apparent lessening in the complexity of the musical system. If we consider that teaching and learning of songs by Warlpiri women are usually inductive rather than explicit, the reduction in the number of presentations of verses, together with the reduction in the duration of melodic sections and song items, makes it more difficult for the novice learner to pick up that the melodic system is actually very flexible. This perhaps encourages a more rote learning approach, where the alignment of textual and melodic units suggests a more fixed placement of the text on the melody. However, as Marett has suggested, such simplification of the musical system may facilitate greater participation by learners (2007). The most important features of this Minamina verse, its text-rhythm setting and the core melodic contour characteristic of the song set, are preserved more or less intact.

Number and variation of body painting designs

Five of the six song events analysed in this chapter are accompanied by the painting of body designs. It is evident that painting up is a far lengthier component and is valued and given more attention by Warlpiri women despite dancing often receiving more public attention. In the instances where dancing did occur, it was short in duration.25 Due to its elicited nature, no painting up was done as part of the 2006 performance, but all others feature the painting of red, black, white and sometimes yellow ochre designs. Over the three days in 1972 when Peterson recorded the Minamina yawulyu ceremonies, she copied 13 different designs painted on women’s breasts, décolletage and upper arms. Each of these designs was painted on numerous women, and their relationships to each other were noted by Peterson too (see Appendix 5.2). Peterson also documented designs drawn on stones, one design painted on a woman’s belly (around her belly button), one design painted on a woman’s upper knees, one design painted on a kuturu “ceremonial pole” inserted into the centralised ceremonial ground, and one design painted on a yukurrukurru “dancing board” held by women during the brief stints of dancing that Peterson noted occurring sporadically during the painting up. Peterson noted that the belly design was “covered over quite quickly”. Nowadays, these belly designs are rarely painted and are often only associated with specific nyurnukurlangu “healing songs” performed in non-public contexts. By contrast, the designs painted on chests are paraded around with pride and often not washed off for several weeks. A woman who is being painted up is said to be imbued with ancestral power as the painted designs and oil are applied to her body.

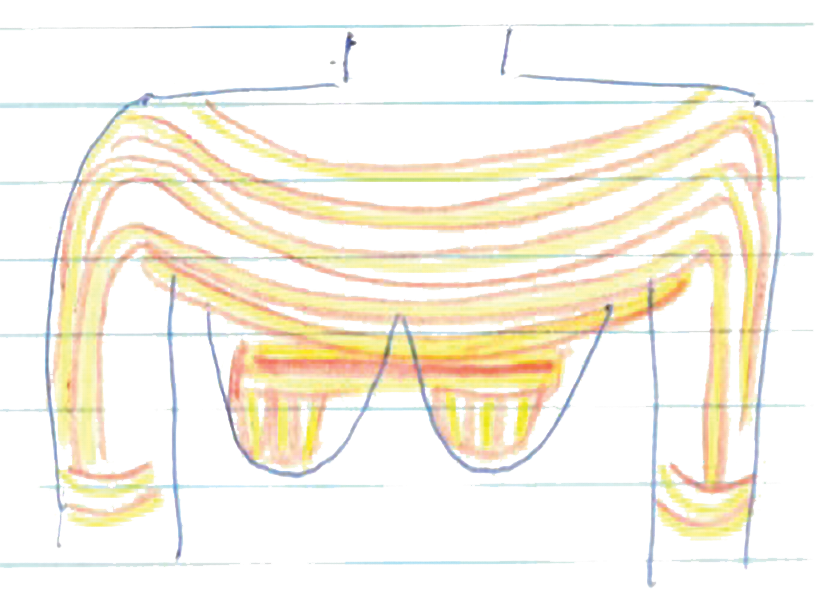

Across the recordings made during the 2016–2018 period, it is evident that the variety of designs had greatly reduced, with only three designs painted – one being copied directly from a photograph from the 1980s and the other two being variations on a single design. The main Minamina design painted on women’s chests during 2016–2018 has long vertical lines down each breast and arm, which are said to also represent the “digging sticks’ that are a key theme in both past and contemporary Minamina yawulyu performances (see Appendix 5.3).

In three of the four performances in recordings 2016, 2017 and 2018, a variation on a single design was painted on all women present with connections to Minamina as kirda. In 2016, all Napangardi/Napanangka women were painted with the same design for Minamina – a series of long vertical lines representing the digging sticks (see Figure 5.5). In the public performances in 2017 and 2018, a variant of this design was painted that did not incorporate the circular designs on the shoulders and lower arms.

Figure 5.5 Barbara Napanangka Martin and Joyce Napangardi Brown painted up with Minamina designs in 2016. Photo by Georgia Curran, 2016.

Despite the overt loss of variation of design in the more recent performances, the strict rules apparent around who paints whom have been maintained across the five-decade period. As a rule, only kirda are painted by their kurdungurlu, senior women with the authority and knowledge to do so. In the more recent recordings, one obvious exception is Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites’ role in painting up. Despite not being in the right kin category for kurdungurlu, her late husband was kirda for Minamina, as was the case for other Nampijinpas in the 1970s who held key kurdungurlu roles. Granites is one of the main senior singers who lead most yawulyu singing and performance in Yuendumu today and has been described as “kurdungurlu for everyone” due to her broad-ranging ritual knowledge.

Conclusion

It is evident that, as there are fewer senior singers and differing performance contexts in the more recent period of 2016–2018, there is a reduction or simplification (or both) of many aspects of what were previously more complex systems of knowledge surrounding performances of Minamina yawulyu. The performances in our sample reveal an overall reduction in the number of verses, the number of repetitions of each verse and the number of associated body designs painted on the women’s bodies as part of the performances. This reduction in the repertory makes sense given the dramatically reduced number of knowledgeable singers today compared to the 1970s when most women over 30 living in Yuendumu were active participants in regular yawulyu events.26

Also observable from these comparisons is a reduction in variability in the setting of verses to melody, indicating various kinds of simplification of song form. In the more recent performance instances, a possibly more westernised and simplified approach is used where the same text line pair always begins each song item. The flexibility of text and melody placement is one aspect of yawulyu singing that is difficult to learn in the contemporary context; knowledge of how to do so relies on a lifetime of participation in different kinds of yawulyu events. Nevertheless, today’s singers take care to perform the correct verses to the correct melodic contour, thus maintaining the core facets of Minamina musical identity.

While several of the more public themes have been carried forth into the recent performances, others that are more restricted to women-only contexts led by groups of knowledgeable senior singers have been dropped from the repertories sung in more recent times. This is likely because, in past decades, yawulyu ceremonies were held in more private women’s contexts where there was also space to discuss surrounding stories and explain the connotations of the songs. In more recent performances, many of which are performances to the broader public, key themes are carried forward but only in their “open” forms, and there is often little chance to articulate the deeper – and less public – meanings of these songs. When Warlpiri women nowadays hold yawulyu in women-only contexts, there is also often an emphasis on teaching younger dancers and children through demonstration and showcasing songs and dances to visitors. Many themes are deemed inappropriate in such contexts, resulting in their loss from the repertories known by the contemporary group of singers.

In a similar way, the reduction in the number of designs may be due to the increase in public performances and youth-focused events where there is a tendency to paint up large groups of young women and children with generic designs, with significant time pressure placed on senior women to ensure that these events are successful. Certainly, the much longer periods devoted to painting up in the 1972 performance, reflected in the high number of items performed for each verse, facilitated more careful and more detailed selection and application of designs.

The overall tendency to reduce variability and complexity observed in multiple dimensions across this chapter has resulted in a notable reduction in the variety of Minamina yawulyu verses known and performed by senior Warlpiri singers. We suggest that such changes allow the song leaders to maintain performances and ensure that younger generations are inheriting the core and deemed essential parts of their cultural identity. Allan Marett (2007) described a similar but perhaps more conscious decision by senior performers of the Walakandha wangga from Wadeye (Port Keats), suggesting that previously complex musical and dance practices were strategically simplified “in order to strengthen the articulation of a group identity in ceremonial performance” (2007, 63). For Warlpiri women, we suggest that musical simplification may be one way in which senior song leaders (in some cases reduced to a single person) can manage the pressures they face to hold together the singing while also instructing younger dancers and guiding other aspects of ceremonial performance. Where once there would have been large groups of women, in more recent performance instances, there are often only a few singers, and sometimes a single leader who knows the songs, guides the dancing and other ritualised movement, and instructs on how to paint the designs. The simplifications we have pointed out may be one way in which song leaders are making their immense role doable, with various performance aspects adapted on the fly when leaders feel overwhelmed by their many responsibilities.

In a contemporary context where Warlpiri women are concerned about the intergenerational transfer of knowledge and practices surrounding yawulyu, Minamina is by no means unusual in making these adaptations. The efforts of senior women to ensure that contexts still exist for younger generations to learn about and understand yawulyu are testament to the important cultural value placed on this song genre. Although some performative aspects may change in response to changing circumstances, it is evident that core knowledges of places in Warlpiri Country and individual women’s family connections are prioritised in the varying ways Minamina yawulyu are being carried forward. The choice to focus on these aspects of Warlpiri place-centred connections ensures that younger women can carry forth a strong cultural identity. The simplification or reduction of some aspects of the performance is a practical means for Warlpiri women today to ensure that they can maintain Minamina yawulyu and a strong female cultural identity for younger generations of Warlpiri women, enabling them to know about and feel connection to their Country and its associated kinship networks and ceremonial practices.

References

Barwick, Linda. 1989. “Creative (Ir)regularities: The Intermeshing of Text and Melody in Performance of Central Australian Song”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 12–28.

Barwick, Linda. 1990. “Central Australian Women’s Ritual Music: Knowing through Analysis versus Knowing through Performance”. Yearbook for Traditional Music 22: 60–79.

Barwick, Linda and Myfany Turpin. 2016. “Central Australian Women’s Traditional Songs: Keeping Yawulyu/Awelye Strong”. In Sustainable Futures for Music Cultures, edited by Huib Schippers and Catherine Grant, 111–144. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barwick, Linda, Mary Laughren and Myfany Turpin. 2013. “Sustaining Women’s Yawulyu/Awelye: Some practitioners’ and Learners’ Perspectives”. Musicology Australia 35(2): 191–220.

Bell, Diane. 1983. Daughters of the Dreaming. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2010. “Linguistic Imagery in Warlpiri Songs: Some Examples of Metaphors, Metonymy and Image-Schemata in Minamina yawulyu”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30(1): 105–15.

Curran, Georgia. 2016. “Travelling Ancestral Women: Connecting Warlpiri People and Places through Songs”. In Language, Land and Song: Studies in Honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch and Jane Simpson, 425–455. London: EL Publishing.

Curran, Georgia. 2018. “The Poetic Imagery of Smoke in Warlpiri Songs”. Anthropological Forum 28(2): 183–96.

Curran, Georgia. 2020a. Sustaining Indigenous Songs. New York: Berghahn Books.

Curran, Georgia. 2020b. “Bird/Monsters and Contemporary Social Fears in the Central Desert of Australia”. In Monster Anthropology: Ethnographic Explorations of Transforming Social Worlds through Monsters, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Geir Henning Presterudstuen, 127–142. London: Bloomsbury.

Curran, Georgia. 2020c. “Incorporating Archival Cultural Heritage Materials into Contemporary Warlpiri Women’s Yawulyu Spaces”. In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, edited by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 91–110. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Curran, Georgia and Françoise Dussart. 2023. “‘We Don’t Show our Women’s Breasts for Nothing’: Shifting Purposes for Warlpiri Women’s Public Rituals—Yawulyu—Central Australia 1980s–2020s”. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. https://doi.org/10.1177/00084298231154430

Curran, Georgia and Otto Jungarrayi Sims. 2021. “Performing Purlapa: Projecting Warlpiri Identity in a Globalised World”. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 22(2–3): 203–19.

Curran, Georgia, Barbara Napanangka Martin and Margaret Carew. 2019. “Representations of Indigenous Cultural Property in Collaborative Publishing Projects: The Warlpiri Women’s Yawulyu Songbooks”. Journal of Intercultural Studies 40(1): 68–84.

Dussart, Françoise. 2000. The Politics of Ritual in an Aboriginal Settlement: Kinship, Gender and the Currency of Knowledge. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Ellis, Catherine. 1985. Aboriginal Music, Education for Living. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Laughren, Mary, Kenneth Hale, Jeannie Egan Nungarrayi, Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Marett, Allan. 2007. “Simplifying Musical Practice in Order to Enhance Local Identity: The Case of Rhythmic Modes in the Walakandha Wangga (Wadeye, Northern Territory)”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 63–76.

Moyle, Richard. 1997. Balgo: The Musical Life of a Desert Community. Nedlands: Callaway International Resource Centre for Music Education.

Peterson, Rosalind. 1972. Fieldnotes from Yuendumu [unpublished].

Pritam, Prabhu. 1980. “Aspects of Musical Structure in Australian Aboriginal Songs of the South-West of the Western Desert”. Studies in Music 14: 9–44.

Turpin, Myfany. 2007. “Artfully Hidden: Text and Rhythm in a Central Australian Aboriginal Song Series”. Musicology Australia 29(1): 93–108.

Turpin, Myfany and Mary Laughren. 2013. “Edge Effects in Warlpiri Yawulyu Songs: Resyllabification, Epenthesis, Final Vowel Modification”. Australia Journal of Linguistics 33(4): 399–425.

Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Georgia Curran (ed.). 2017. Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu [including DVD]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Young, Diana. 2005. “The Smell of Greenness: Cultural Synaesthesia in the Western Desert”. Etnofoor 18(1): 61–77.

Archival references

Curran, Georgia and Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan. 2005–2008. “Warlpiri Songlines (Minamina Yawulyu)”. [AIATSIS accession no. PETERSON_CURRAN_01]

Curran, Georgia. 2017. “Southern Ngaliya Dance Camp at Mijilyparnta” [unpublished field recording, video].

Deacon, Ben and Myfany Turpin. 2017. “Northern Territory Writers Festival” [unpublished field recording, video].

Macdougall, Colin and Nathan Duke. 2018. “Warlpiri Performance at the NT Tent Embassy” [unpublished field recording].

Peterson, Nicolas. 1972–1973. “Nic Peterson Collection (Y7 Women’s Ceremony)” [43 audiotape reels, approx. 60 minutes each, digital access copies]. [AIATSIS accession no. PETERSON_N03]. Recorded at Yuendumu, NT.

Warlpiri women from Yuendumu (produced by G. Curran). 2017. Yurntumu-wardingki juju-ngaliya-kurlangu yawulyu: Warlpiri women’s songs from Yuendumu [DVD]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Appendix 5.1. Melody/text layout across 26 items of MI01 (common verse across all performance instances analysed).

| Line A: minamina pilarlany kijirninya Line B: japingka pilarlany kijirninya Abbreviations: melodic section (MS), text line reversal (TLR), text line phasing (TLP), Northern Territory Writers Festival (NTWF), Tent Embassy (TE). | |||||||

| Item | MS1 | MS2 | MS3 | MS4 | MS5 | MS6 | Comment |

| 1972 i | BB | AA | BBA | ||||

| 1972 ii | AA | BBAA | BBA(A) | TLR | |||

| 1972 iii | AA | BBAA | BBA(A) | ||||

| 1972 iv | AA | BBA(A) | BBA(A) | ||||

| 1972 v | BBAA | BBA(A) | BBA(A) | TLR disagreements MS1 | |||

| 1972 vi | BB | AABB | AAB(B) | TLR | |||

| 1972 vii | BB | AABB | AAB(B) | ||||

| 1972 viii | AA | BBAA | BBA(A) | TLR | |||

| 1972 ix | BB | AA | BBA(A) | BBA(A) | TLR | ||

| 1972 x | - | BB | AA | BB | AA | BB | TLR straight on, no MS1, maybe MS5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| 1972 xi | [A]AA | BBA | BBA | NB: note incomplete text cycle MS2 – 3 lines/MS | |||

| 1972 xii | BB | AABB | inaudible | TLR talking | |||

| 1972 xiii | AA | BBA | ABB | AAB | TLR | ||

| 1972 xiv | BA | ABB | AA | BB | AA | BB | straight on – TLP |

| 1972 xv | - | AB | BAA | BB | AA | BBA | nearly straight on – TLP |

| 1972 xvi | [A]AA | BBAA | BBA(A) | TLR | |||

| 1972 xvii | AA | BBA | |||||

| 2006 i | [-?] | [A]A | BBA(A) | BBAa1 | a2BB | recorder on mid-item | |

| 2006 ii | [hum] | AABB | Aa1 | a2BB | AABB | cued by TR | |

| 2017 NTWF iii | Aa1 | a2BB | AA(B) | items i, ii, iv inaudible due to competing singing | |||

| NTWF iv | Aa1 | a2BB | AA(B) | dancing | |||

| NTWF v | - | AA | BB | AA | dancing | ||

| SNDC i | AAB(B) | fragment | |||||

| 2018 TE i | AA | BB | AA | ||||

| 2018 TE ii | AA | BB | AA | ||||

| 2018 TE iii | AA | BB | |||||

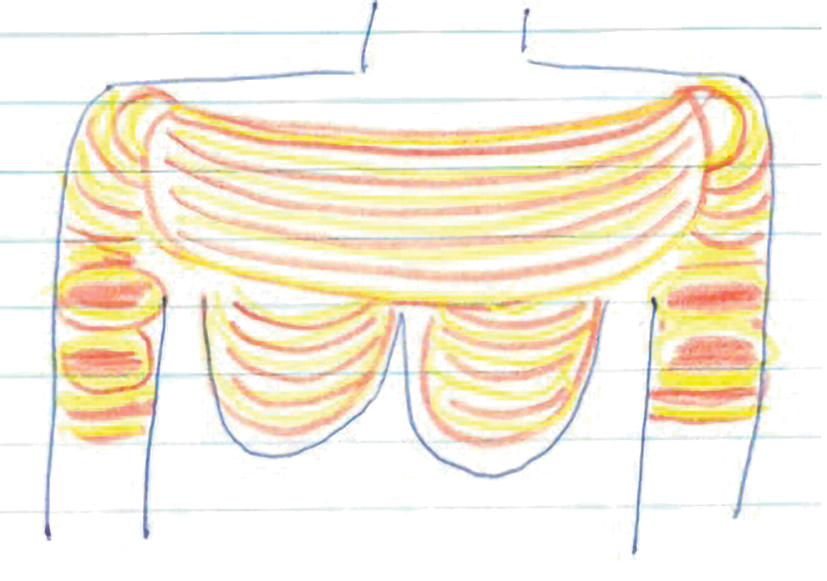

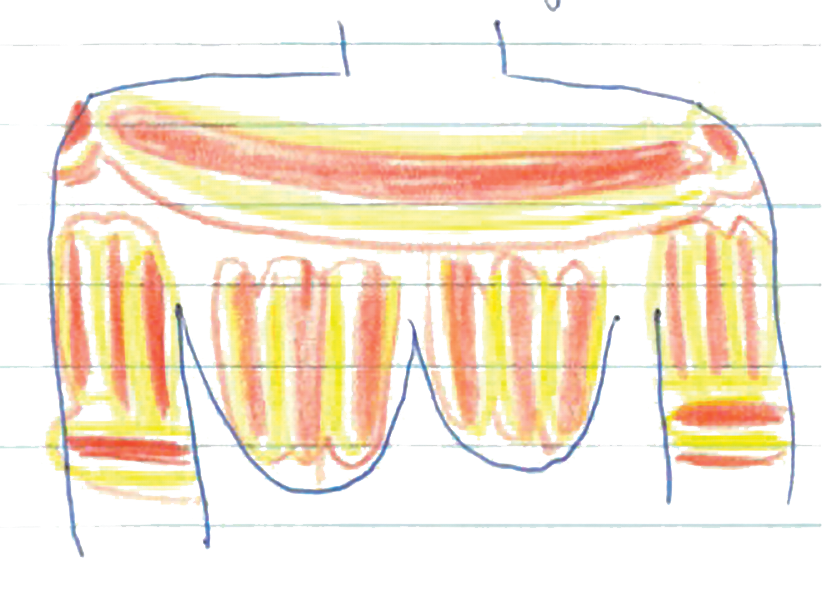

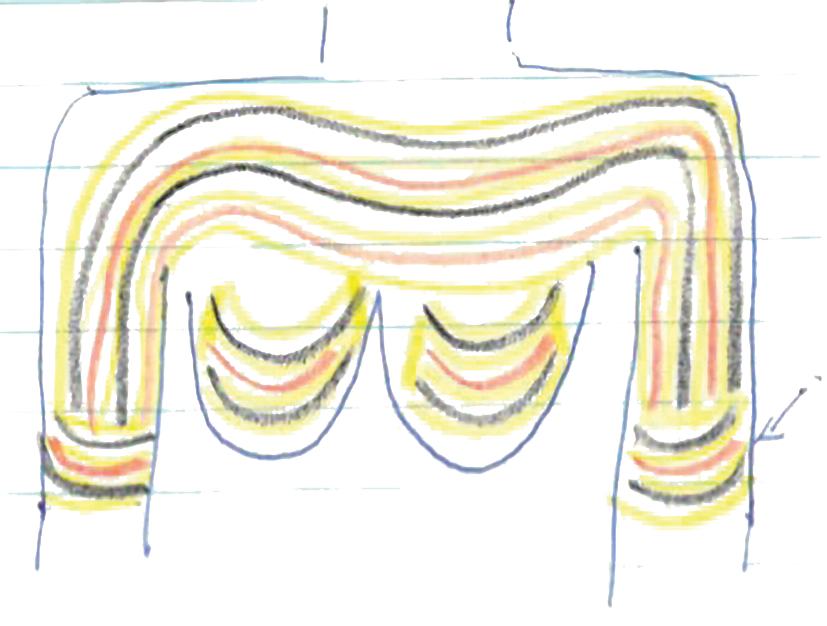

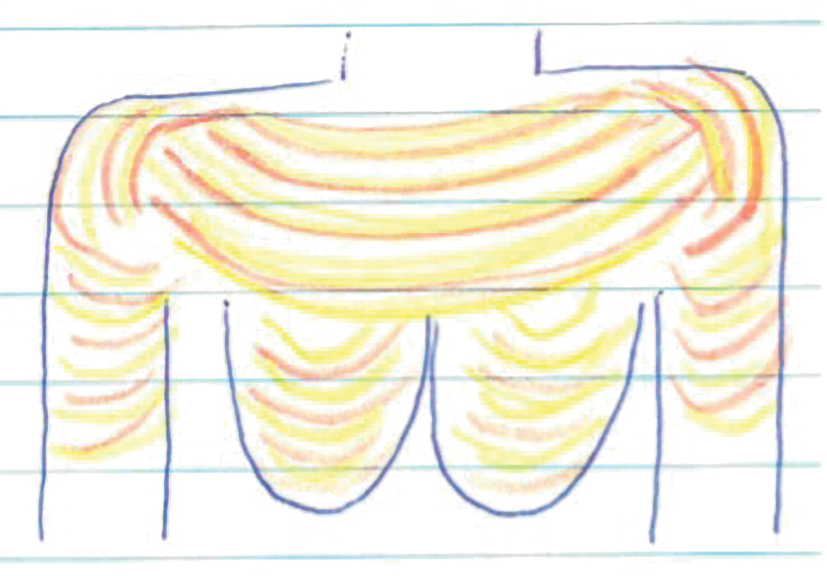

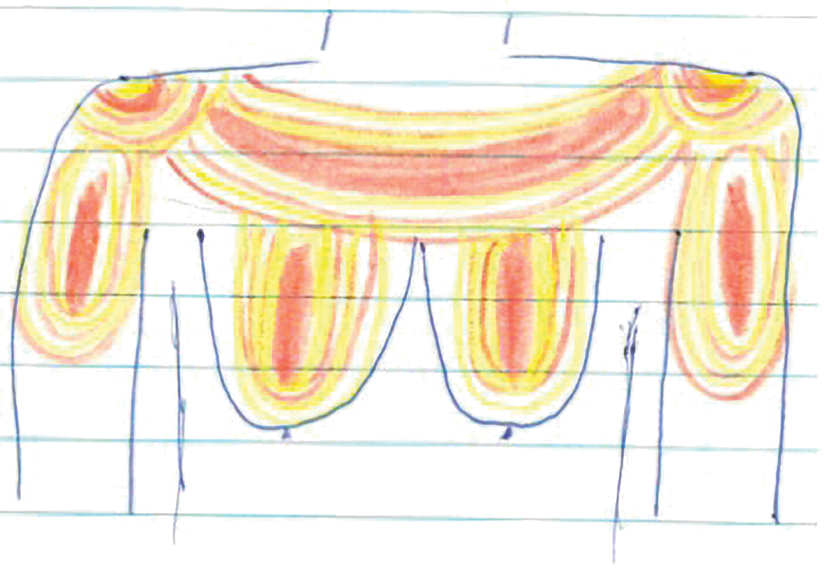

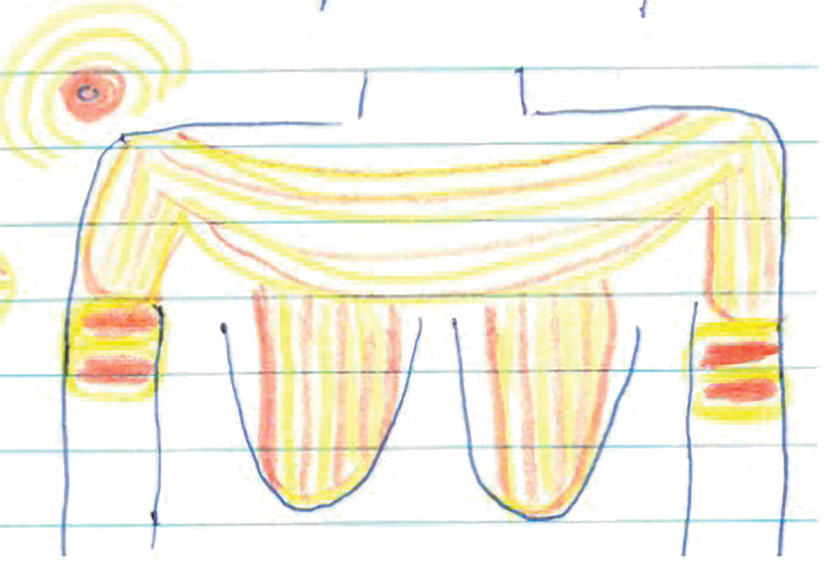

Appendix 5.2. Designs painted in 1972 based on Rosalind Peterson’s notes (orthography changed to standardised version).

Note: the yellow-coloured pencil represents white ochre used during the painting up

| Date/Design # | Design | Who painted who (relationship) |

|---|---|---|

|

24/6/1972 |

|

Maggie Napangardi painted by Dolly Nampijinpa (mantirri “sister-in-law”) |

| 24/6/1972 Design 2 |

|

Judy Napangardi painted by Jeanie Napurrurla (yurntalpa “brother’s daughter” > ngati “mother”) |

| 24/6/1972 Design 3 |

|

Millie Napangardi painted by Helen Napanangka (jukana “cross-cousin” for each other) |

| 24/6/1972 Design 4 |

|

Polly Napangardi painted by Dolly Nampijinpa (yabala?) |

| 24/6/1972 Design 5 |

|

Mary Napangardi painted by Jeanie Napurrurla (yurntalpa “brother’s daughter” > ngati “mother”) |

| 24/6/1972 Design 6 |

|

Jeanie Napurrurla painted by Judy Nampijinpa |

| 25/6/1972 Design 7 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

| 25/6/1972 Design 8 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

| 25/6/1972 Design 9 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

| 26/6/1972 Design 10 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

| 26/6/1972 Design 11 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

| 26/6/1972 Design 12 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

| 26/6/1972 Design 13 |

|

Details not provided in Peterson’s notebooks |

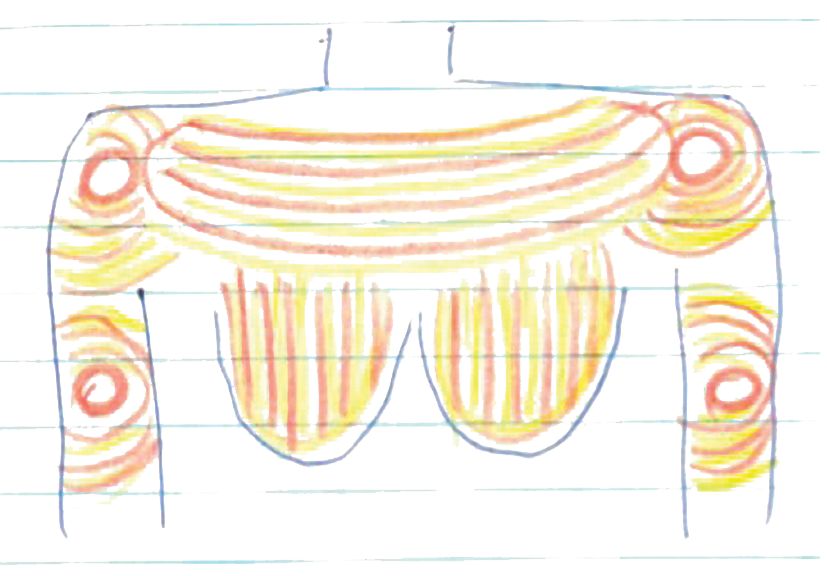

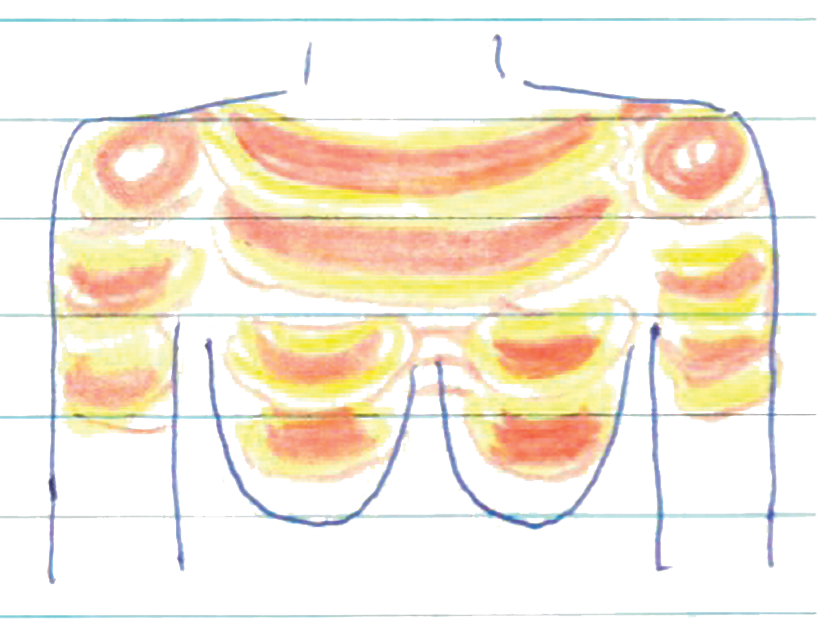

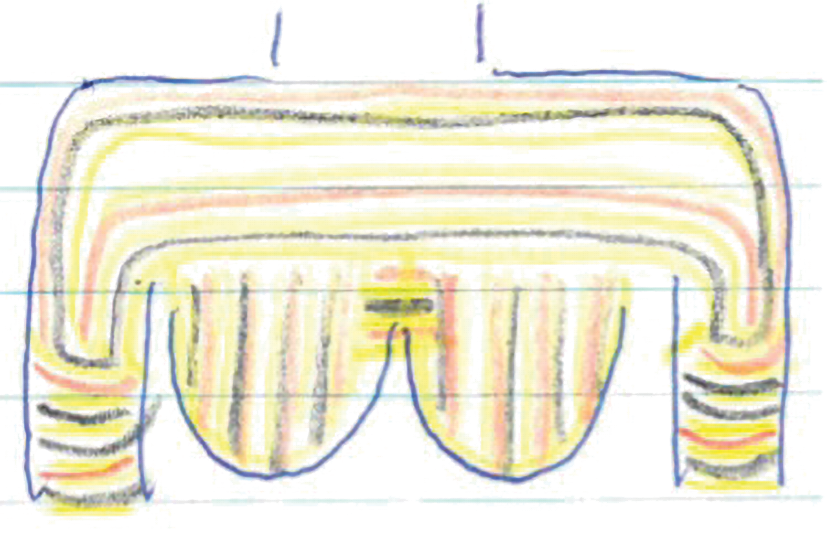

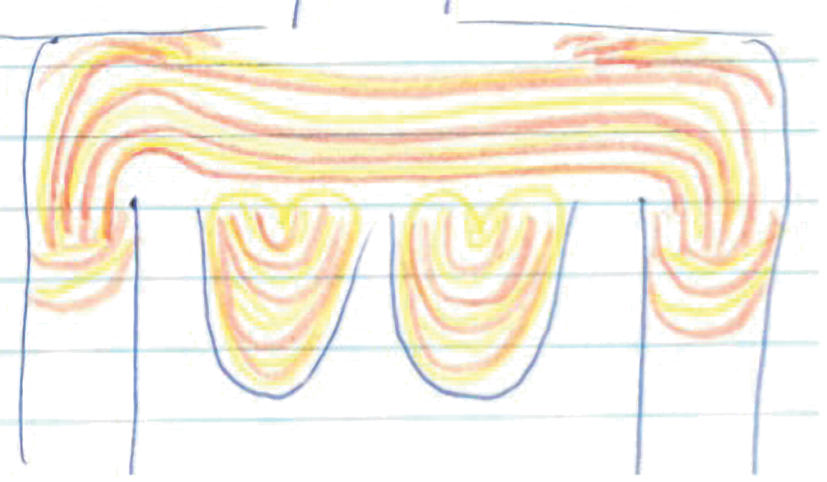

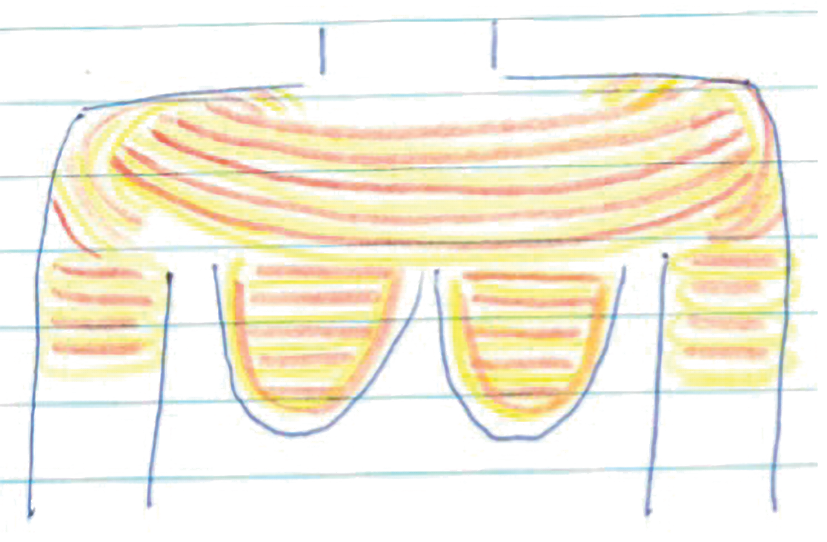

Appendix 5.3. Designs painted in performances (2016–2018).

| Date/Event | Design | Key features | Who painted who? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18/7/2016 |

|

Vertical lines down breasts and arms represent digging sticks | Joyce Napangardi Brown and Barbara Napanangka Martin painted by Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites; Cecily Napanangka Granites painted by Peggy Nampijinpa Brown |

| March 2017/ Southern Ngaliya dance camp |

|

Circular designs across chest represent the truffles | Cecily Napanangka Granites painted by Peggy Nampijinpa Brown with guidance from Lucky Nampijinpa Langton |

| May 2017/ Northern Territory Writers Festival |

|

Vertical lines down breasts and arms represent digging sticks | Alice Napanangka Granites and Elsie Napanangka Granites both painted by Lynette Nampijinpa Granites |

| 2018/Tent Embassy |

|

Vertical lines down breasts and arms represent digging sticks | Alice Napanangka Granites and Barbara Napanangka Martin both painted by Lynette Nampijinpa Granites |

Fanny Walker Napurrurla

Photo by Gertrude Stotz. Used with permission.

Fanny Walker (c. 1926–2019) was a traditional Warlpiri woman who maintained a very strong connection to her father’s Country of Jipiranpa, its stories and rituals. She was born in the Pawurrinji area near a rockhole called Karlampi from which her personal name Karlampingali derived. Napurrurla lived at the Phillip Creek Native Settlement before being moved with two of her daughters to the Warrabri Aboriginal Reserve, now known as Alekarenge, established by the government in 1956. Napurrurla had a great love and knowledge of Warlpiri yawulyu and was an active performer until her death in 2019. In 2009, she and her sisters collaborated with their son Brian Murphy and his Ali Curung Band Nomadic to create innovative performances that combined her traditional yawulyu singing with western-style country rock music, including a song about Jipiranpa. In 1996–1997, Napurrurla was among a large group of Alekarenge women recorded by Linda Barwick singing two series of Ngurlu yawulyu songs associated with Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji. In 2010, she collaborated with Barwick and Laughren in their documentation of the Jipiranpa song series by again singing the verses, speaking them in Warlpiri and explaining their meaning and geographic context.

1 Warlpiri men also sing songs about the journey of the group of ancestral women, but this chapter is devoted to the women’s songs. The Minamina songs that men sing are sung all night for Kurdiji ceremonies in Lajamanu (see Curran 2016).

2 There are many sites around Warlpiri country named Mina. In Warlpiri the word mina refers to a “[protective entity in which being lives or sleeps.] nest, lair, home, shell, living place, residence, niche, camp, enclosure, husk, shell, protective membrane, pericarp” (Laughren et al. 2022). In this chapter, Minamina is a specific place located in the far west of Warlpiri country, to the north-east of Lake Mackay.

3 The association of digging sticks with women is very salient. Females’ umbilical cords are karlangu “digging stick” and males’ are karli “boomerang” (Laughren et al. 2022: 1337).

4 As there is relative fluidity of movement between Warlpiri communities, the singers would have had affiliations to a number of different Warlpiri communities.

5 Nicolas Peterson (2022 pers. comm.) has noted that the community was preparing for a Jardiwanpa ceremony that was being held in the evenings, but which was never finished due to a death in a nearby community.

6 See the book Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu (2017) by Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran, in which this story and some of the verses of Minamina yawulyu have been written down.

7 Ngarna is also the word used for an ant nests (as well as depressions in the country) indicating that the women moved away like ants move away from their nest.

8 Barbara’s mother remarried when Barbara was a young girl so she grew up with a father from different Country. Although Barbara knew all her life that she was kirda for Minamina, it is only in the last five years that she has started learning from senior Warlpiri women about Minamina stories, songs and dances in the process of documenting them for the book, Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran (2017).

9 These recordings are archived at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) with Nicolas Peterson’s recordings from Yuendumu (1972–1973).

10 The recording machine was positioned close to the stone in which ochres were being ground; in some sections, this dominates the audio recording, overriding the singer’s voices.

11 This was an Australian Research Council Linkage project between the Australian National University, University of Queensland, the Central Land Council and the Warlpiri Janganpa Association, with Chief Investigators Nicolas Peterson, Mary Laughren and Stephen Wild, PhD student Georgia Curran, and key research collaborators Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan and Thomas Jangala Rice.

12 Judy and her sisters were married to Japangardi brothers who were all kirda for Minamina.

13 C. Gallagher was, however, one of the main singers accompanying Judy Granites in the 2006 recording, which was made when she was one of the main senior singers in Yuendumu.

14 These jilkaja songs have been excluded from this chapter as they are only intended for Warlpiri women to hear. Because Granites led the singing during this event, no other senior women picked up that these jilkaja songs were inappropriate to include. Lynette Granites, who had not been part of the recording as she was in Alice Springs at the time, complained about this to Lorraine Granites a number of years later and asked for them to be removed from public access points.

15 The yawulyu verse sung while the women were dancing is classified as being Yarlpurru-rlangu “Two Age-Brothers”, referring to the jukurrpa story about the two ancestors who were initiated in the same ceremony and meet together to re-establish the special bond that they have for life.

16 At the Northern Territory Writers Festival performance in 2017, the event organisers had an allotted time for the Warlpiri women’s presentation and a livestream organised, creating pressures to hurry along the painting up and dancing.

17 Often the repeated lines in a verse differ in their final vowel qualities, though this is not perceived as linguistically significant by singers. In the following examples, the standard form of the line-final vowel is presented.

18 The word wayurangka may be an example of poetic language used only in song.

19 Janyinki is nowadays sung about in a “light” version of the verse due to the centrality of this site for the travels of the ancestral women; however, it has strong women-only knowledge that is not shared publicly.

20 Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan and Thomas Jangala Rice, pers. comm. 2006 and Lynette Nampijinpa Granites, pers. comm. 2017.

21 The snake vine has many other uses, which the song may also evoke in other contexts.

22 The verse was not performed for the 2016 DVD performance (Recording 3 in Table 5.1).

23 While clear groupings of the short notes into triplets can be observed, the long notes are consistently four quavers in length.

24 Other clues to the flexibility of the system may be gained when the text line pair or a text line is split across two melodic sections (e.g., 1972, items xiv and xv), or when a text line is split across two sections, usually only possible when there is a mid-line long note (e.g., Minamina / pilarlany kijirninya, found in Deacon and Turpin 2017, items ii and iv).

25 Often, for public performances, Warlpiri women paint up in a private space before entering a staged area to dance. The audiences that attend these performances see only the dancing component of yawulyu.

26 Attrition of song knowledge has been further exacerbated by demographic shifts of recent decades that have seen significant proportional increases in Yuendumu’s youth population.