6

Expert domains of knowledge in Ngurlu yawulyu songs from Jipiranpa

This chapter focuses on Ngurlu yawulyu “Edible Seed” songs from the Warlpiri homeland of Jipiranpa, as performed and explained by Fanny Walker Napurrurla (c. 1926–2019). The associated story concerns a man of the Jakamarra skin from Jipiranpa, who lusts after his mothers-in-law: two Nangala women from Kulpurlunu, whose Dreaming is Ngapa (Rain/Water). As they travel across Jipiranpa Country,1 the two Nangala women collect and process many different types of edible seed, observed and tracked by Jakamarra. We reflect on some of the challenges for contemporary Warlpiri people in accessing and passing on to future generations the expert knowledge of Country, Dreamings and performance conventions that are integrated within the songs.

Recordings of the songs were made in 1996 and 1997, when a group of Warlpiri women living at Alekarenge, including Napurrurla, performed Ngurlu yawulyu “Edible Seed” songs for Linda Barwick, David Nash and Jane Simpson. The Jipiranpa songs that form the subject of this chapter were performed intermingled with a second set of Ngurlu yawulyu songs from the Warlpiri homeland of Pawurrinji. Years later, in 2010, Napurrurla and her daughters, Sarah Holmes Napangardi, Jessie Simpson Napangardi and Judith Robertson Napangardi, worked alongside Laughren and Barwick to transcribe and translate the Jipiranpa verses and record additional stories and commentary. In 2018–2021, Barwick and Laughren checked the recordings and transcriptions of the 47 Jipiranpa verses with Napurrurla’s daughters and Warlpiri translator Theresa Ross Napurrurla.

In the main part of the chapter, we introduce the songs and stories associated with them, as explained by Fanny Walker Napurrurla, reflecting on some of the difficulties inherent in working with the multiple domains of expert knowledge inherent in the ancestral story and the songs. These include knowledge of Jipiranpa Country and its various ancestral tracks and stories, knowledge about seed-processing practices, knowledge of musical conventions and knowledge of the “hard language” of song. Appendix 6.1 contains text transcriptions, linguistic glosses, rhythmic transcriptions and commentary for each of the 47 Jipiranpa verses.

Social history of the Jipiranpa Ngurlu songs

In 2010, Fanny Walker Napurrurla explained to Barwick and Laughren how the Ngurlu yawulyu songs had been brought to Alekarenge along with other Warlpiri Dreamings:

I was a young woman (adult) when I came to Alekarenge. People had been at Philip Creek first, and there was no water, so we were moved to Kaytetye people’s country at Alekarenge. The old people brought the songs and ceremonies for Miyikampi. They brought the Ngurlu Seed ceremonies for Jipiranpa and for Pawurrinji. They brought the Ngapa Rain/Water ceremony for Kulpurlunu.

The Nangalas and Nampijinpas danced for Ngapa (rain/water).

The Napanangkas and Napangardis danced for Miyikampi.

The Nakamarras and Napurrurlas danced for Jipiranpa (my side) and for Pawurrinji.

Also the Jarrajarra groups (Napaljarri-Nungarrayi) had their business and the women would dance for their own father’s father’s country and Dreaming.

It was the old people who have since passed away who taught me and the others the songs and dances and paintings. They used to paint up.2

Napurrurla was very strong in her identification with her Country, Jipiranpa. In 2021, Napurrurla’s daughters, Jessie Simpson Napangardi and Sarah Holmes Napangardi, reminisced about Napurrurla’s last visit to Jipiranpa:

We went with our mother to Jipiranpa around … 2018 or 2019. She asked us to take her. She talked to all of us to take her one last time to see her country.

That Jipiranpa is on the south side. Rangers from Willowra go and look after that country.

Jipiranpa is a beautiful place. Not too rocky. Stones that sparkle in the moonlight. It was really hot when we went, so we had to make shade.

It was a long, long road to Jipiranpa. We slept halfway on the trip, and we went to other people’s country too.

We stayed for two nights at Jipiranpa. First, we settled in and found a place to camp. The next day we went in the Toyota. Our mum was showing us that place – the rockholes. She was telling stories and singing. We were just driving around going from one rockhole to another.

Our mum and that old man J. Bird Jangala were talking for that milarlpa “spirit people”. She was saying that it was her last trip and was telling them that it was OK for her family to keep visiting that place after she was gone.

We had feeling for that country. We could feel those milarlpa around us. If we woke up at night, we had to wake up others for company.3

This statement shows how visits to Country can create strong memories and instil attachment to Country, ancestors and Dreamings.

Edible Seed Dreamings

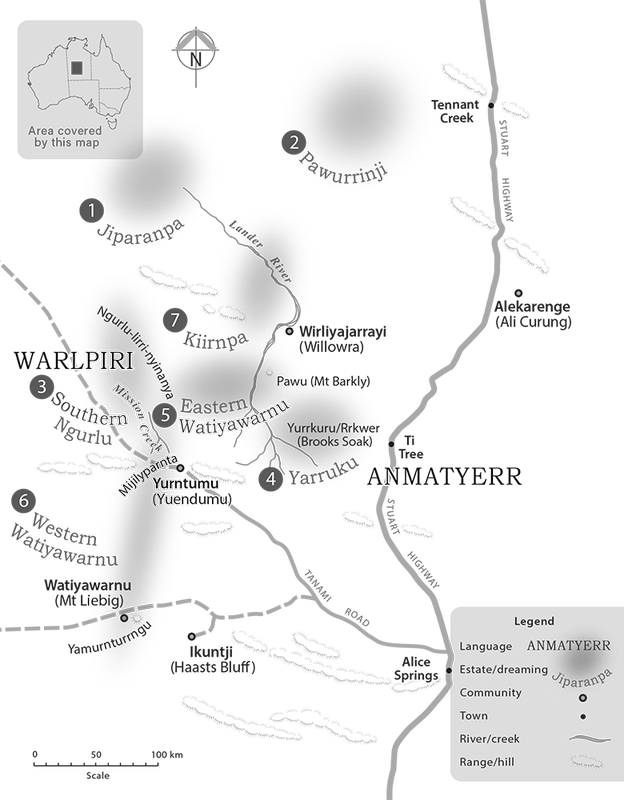

Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji are just two of a number of different Warlpiri Countries associated with Edible Seed Dreamings (Curran et al. 2019; see Figure 6.1). The various seed Dreamings have in common a stock of women’s knowledge and understandings about how to gather and process edible seeds, but each Dreaming is embedded within its own characteristic ancestral places and histories and often has its own ways of structuring the songs and their music. Some Dreaming tracks cross different Countries, and this is the case for the Ngurlu Dreaming for the Countries of Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji. Several verses in the Ngurlu Jipiranpa song set also occur in other yawulyu song sets, including the Ngurlu yawulyu from Pawurrinji (Barwick 2023), the Arrwek/Yarruku yawulyu (Watts et al. 2009; Yeoh and Turpin 2018), and the Jardiwanpa yawulyu (Gallagher et al. 2014).

Figure 6.1 The general location of Warlpiri and Anmatyerr “Edible Seed” yawulyu, including (in the north) Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji (from Curran et al. 2019). Map by Brenda Thornley.

This chapter will focus on the Jipiranpa songs for which Fanny Walker Napurrurla was principal kirda (owner). Most of these songs were discussed at length with her by Barwick and Laughren when we replayed these sessions to her and her family when visiting Alekarenge in 2010 (Figure 6.2).4 Napurrurla did not want to comment on any Pawurrinji songs included in the recordings.

Figure 6.2 Fanny Walker Napurrurla discusses her yawulyu Jipiranpa songs with Mary Laughren and Linda Barwick, witnessed by her daughters and other family members, Alekarenge, 19 July 2010. Photo by Myfany Turpin. Used with permission.

Background to the 1996–1997 recordings

In 1996 and 1997, Barwick and linguist David Nash recorded four sessions of Ngurlu yawulyu singing at Alekarenge. These were non-ceremonial performances staged primarily for the purpose of recording. Facilitated by Nash and fellow linguist Jane Simpson, Barwick was visiting Alekarenge at the request of a senior Warlpiri songman, Engineer Jack Japaljarri, who wanted to record his knowledge of men’s yilpinji songs (selected public men’s songs that could be heard by women).5 At Japaljarri’s request, each day, Barwick also moved to the nearby jilimi “single women’s quarters” to record women’s ceremonial yawulyu songs from a number of different Dreamings, including Ngapa “Rain” yawulyu and Ngurlu “Edible Seed” yawulyu.

As explained above by Fanny Walker Napurrurla in 2010, holders of the Ngurlu “Edible Seed” Dreaming at Alekarenge at this time came from two different Warlpiri estates (“Countries”): Jipiranpa, in the Tanami Desert west of Alekarenge, and Pawurrinji, north-west of Alekarenge (rough locations shown in Figure 6.1). In the 1920s and 1930s, many Warlpiri people from these and other Countries left their homelands, driven out by drought and the Coniston massacres (Kelly and Batty 2012; Nash 1984). Napurrurla and the other women who performed Ngurlu yawulyu for Barwick in 1996 and 1997 had previously lived and performed together on Warumungu Country at Phillip Creek Reserve, established in the 1930s, which was transferred, due to lack of water, in the 1950s to a new government settlement on Kaytetye Country that was initially given the name “Warrabri”6 and later renamed Alekarenge (Bell 1993; Nash 1984, 2002).

The kirda for Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji Countries belong to the same Napurrurla-Nakamarra semi-moiety.7 In the four performances in our corpus, the principal kirda were Fanny Walker Napurrurla and Mary O’Keeffe Napurrurla (for Jipiranpa) and Ada Dickenson Napurrurla (for Pawurrinji). The kirda were supported in holding and performing their songs by senior kurdungurlu “managers”, who had inherited Ngurlu Country and Dreaming affiliation through their mothers (so belonging to the Nungarrayi and Napangardi subsections) or mother’s mothers (Nampijinpa, Nangala). In these performances, the principal kurdungurlu were Irene Driver Nungarrayi, Edna Brown Nungarrayi and Lillian Napangardi.8 The principal performers on each occasion are listed in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Four performances of Ngurlu yawulyu recorded at Alekarenge by Linda Barwick and David Nash in 1996 and 1997.

| Performance # | Date performed and session title | Kirda | Kurdungurlu | Recording ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance 1 | 17 September 1996 “Yawulyu Ngurlu at Jipiranpa” |

Fanny Walker Napurrurla, Mary Napurrurla, Ada Dickenson Napurrurla, Annette Nakamarra, Marjorie Limbiari Nangala-Napurrurla | Irene Driver Nungarrayi, Lillian Napangardi, Peggy Napangardi, Jessie Rice Nungarrayi, Edna [Brown] Nungarrayi | Barwick AT96/18, DT96/5, notebook 96/1:17–28 |

| Performance 2 | 21 September 1996 “Yawulyu Ngurlu coming in to Pawurrinji” |

Ada Dickenson Napurrurla, Fanny Napurrurla | Irene Driver Nungarrayi, Lillian Napangardi, Nancy Jones or Downes Nungarrayi, Nancy Lauder Nungarrayi, Rosie Napangardi | Barwick AT96/23–24; DT96/10–11; notebook 96/1: 87–99 Nash: V53 |

| Performance 3 | 19 August 1997 “Yawulyu Ngurlu at Jipiranpa” |

Mary Small O’Keeffe Napurrurla, Ada Dickenson Napurrurla, Annette Nakamarra, Ivy Napurrurla, Lorraine Napurrurla | Edna Brown Nungarrayi | Barwick AT97/13AB; DT97/8, notebook 97/2; Nash: V61 |

| Performance 4 | 20 August 1997 “Yawulyu Ngurlu Pawurrinji and Jipiranpa mixup” |

Mary Small O’Keeffe Napurrurla, Ada Dickenson Napurrurla, Amy Morrison Nakamarra, Lorraine Limbiari Napurrurla, Ivy Limbiari Napurrurla, Elaine Driver Nakamarra, Maudie Fishhook Nakamarra, Annette Nakamarra Jackson | Edna Brown Nungarrayi | Barwick AT97/16AB–17A, DT97/11; notebook 97/2; Nash: V64 |

As is usual in Central Australian traditional singing, each singing session consisted of several short song items, separated by stretches of silence or quiet discussion. Song items are grouped into sets of 2–5 repetitions of a single verse. A given verse may recur later in a singing session or in a different session.9 Although the verse order is said by some to follow a fixed sequence of events and sites to form a “songline”, in practice, ordering is flexible and can be based on several factors, typically discussed between kirda and kurdungurlu in the breaks between song items.10

Each Ngurlu yawulyu performance comprised over 100 song items (see second column of Table 6.2). The third column of Table 6.2 shows the total number of discrete verses in each session. In total, 19 of the total 47 Jipiranpa verses occurred in more than one performance. In the fourth and fifth columns of Table 6.2, we have subdivided the verses in each Ngurlu yawulyu performance into those belonging to Jipiranpa and those belonging to Pawurrinji. We can see that in both 1996 and 1997, the women chose to perform first a session focused on Jipiranpa verses (Performances 1 and 3) and, on a later day, a session focused on Pawurrinji verses (Performances 2 and 4). Nevertheless, each performance recorded includes verses from both Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji.

Table 6.2 Distribution of song items and verses from Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji across the corpus.

| Performance | Number of song items | Total number of discrete verses | Number of Jipiranpa verses | Number of Pawurrinji verses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance 1 (1996) | 104 | 37 | 33 | 4 |

| Performance 2 (1996) | 191 | 51 | 3 | 48 |

| Performance 3 (1997) | 110 | 35 | 30 | 5 |

| Performance 4 (1997) | 110 | 32 | 6 | 26 |

The verses selected and the sequence in which they are performed can vary considerably from one performance to another, but particular verses are generally chosen to highlight stories and connections relevant to the purpose of the performance and the people who are participating. For example, in these song sessions, the mixing of Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji verses reflects the affiliations of those participating in the performances, as well as their shared Dreamings, histories and migration stories.

Texts, rhythms, translations and comments for each of the 47 Jipiranpa verses identified in our recordings are included in Appendix 6.1, together with an indication of where to find the songs on the recordings. Most verses were discussed intensively by Fanny Napurrurla and Mary Laughren in 2010. For several verses, Fanny Walker Napurrurla provided additional versions as part of her commentary. Translations and comments for four of the verses (Verses 25, 31, 32, 40) are tentative because we were not able to discuss them directly with Fanny Walker Napurrurla in 2010. In 2020, Theresa Ross Napurrurla assisted with translations, and some additional commentary was also provided in 2021 by Napurrurla’s daughters, Sarah Holmes Napangardi, Jessie Simpson Napangardi and Judith Robertson Napangardi.

What Ngurlu yawulyu Jipiranpa songs are about

The songs interweave several themes related to the Dreaming story associated with the song. In 2010, Fanny Walker Napurrurla explained to Barwick and Laughren that the story concerns an ancestral Jakamarra from Jipiranpa who is following (and lusting after) two Nangala sisters (whose Dreaming is Ngapa “Rain”) as they travel across his Country. These Nangala women stand in the classificatory mother-in-law relationship to Jakamarra, the most prohibited “wrong way” social relationship in the Warlpiri marriage exchange system. Normally, any form of social contact between mothers-in-law and sons-in-law is strictly avoided. In this way, the story highlights the Warlpiri Law of marriage exchange (Curran 2020; Laughren et al. 2018).

Napurrurla explained:

Parajalpa-palangu Nangala-jarra, Jakamarrarlu, Yimarimarirli. Wrong-way.

Yimarimari11 Jakamarra followed the two Nangala women. Wrong way [they were his classificatory mothers-in-law]

Wiiwii-jarrinjinanu-pala. Mawu-palangu nyangu. “Nyampu nyurruwarnu waja”. Tuurn-kijirninja-yanu. “Nyurruwarnu-juku, nyurruwarnu waja nyampuju. Wurnturulpa-pala yanu karlarra.” Jutu-pungu-palangu.

They [the two women] urinated as they went along. He saw where they had urinated. “This is an old one” [Jakamarra said to himself]. He kept going [following their tracks]. “Still an old one, this is an old one. The two of them have gone far west.” He stopped following them.

“Yanirni kapala, kutulku waja!” Finishi-manu jutulpa-palangu …

Nguru-nyanu-kurra-pala yanu, Kulpurlunu-kurra marda-pala yanu.

“They are coming this way, getting closer now!” He finished going after them …

They [the two Nangalas] went back to their own place. Maybe they went to Kulpurlunu [principal site for Ngapa (Rain/Water) Dreaming].12

Expert knowledge of edible seeds

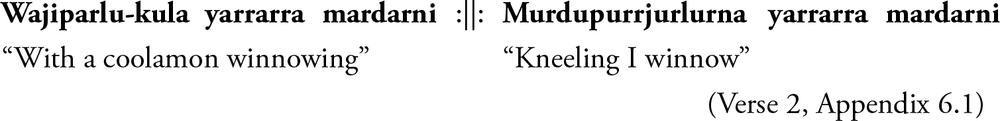

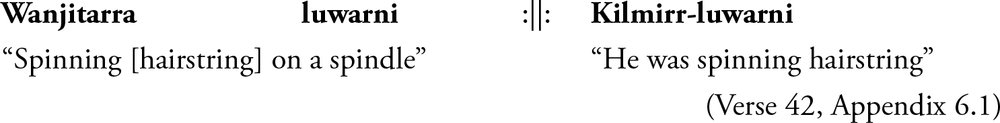

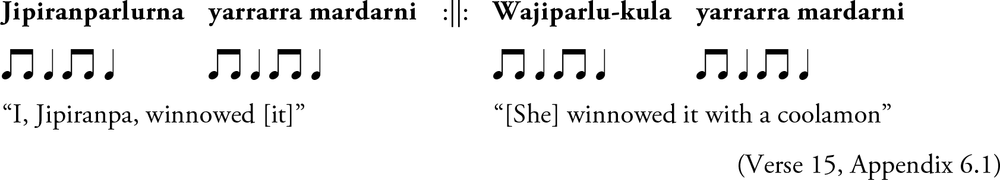

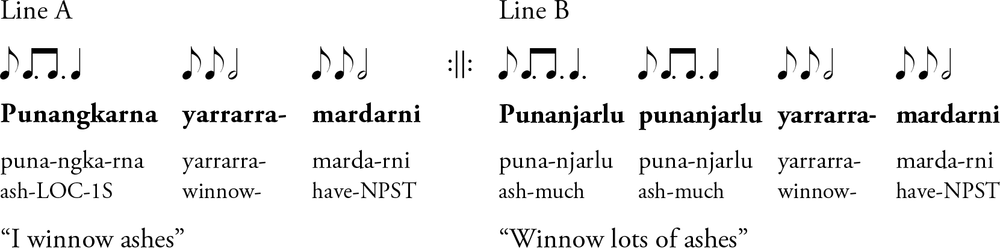

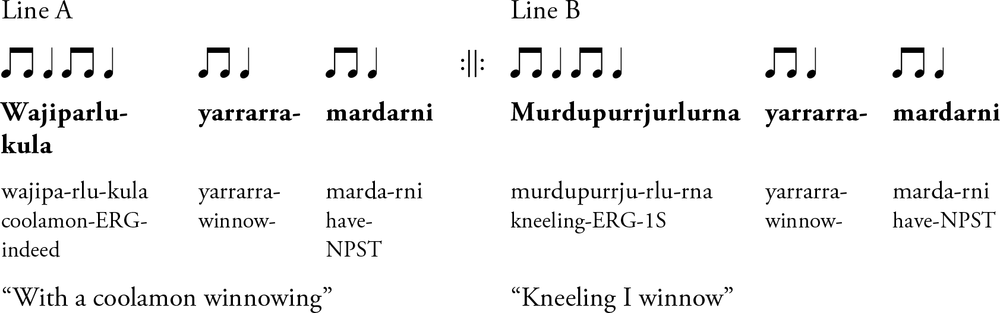

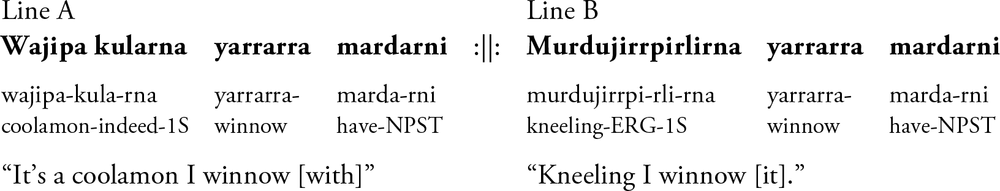

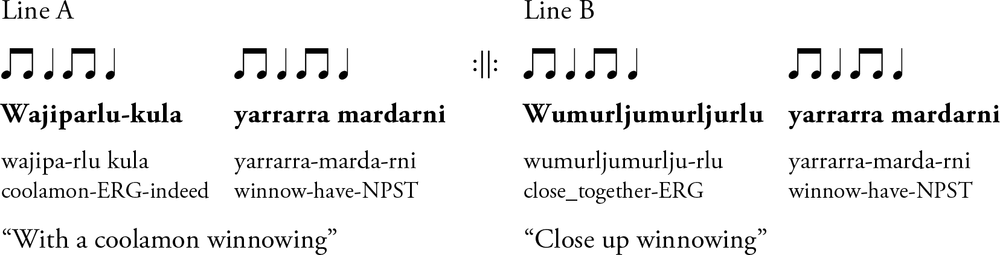

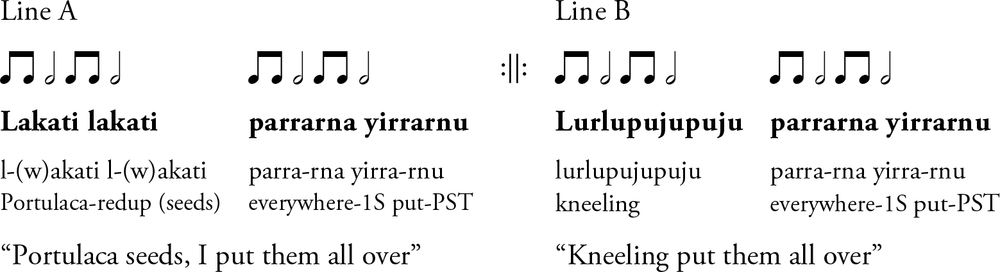

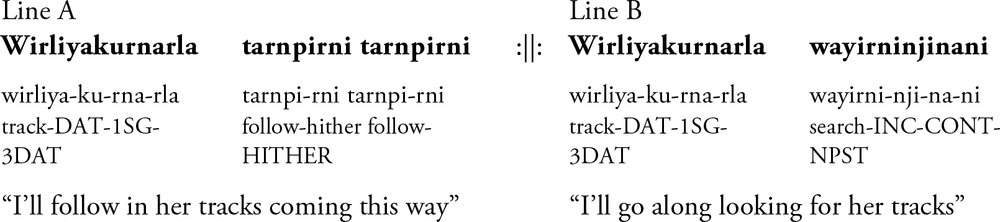

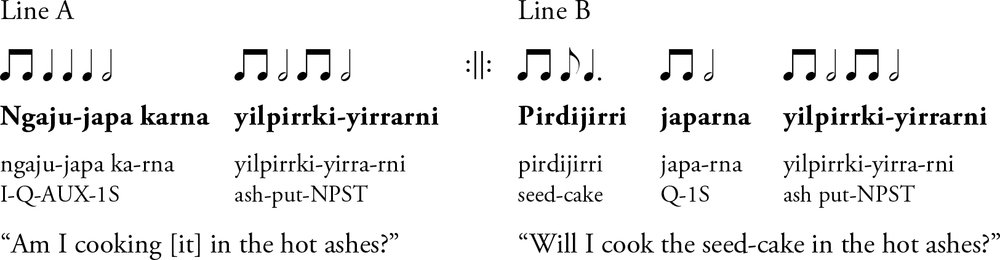

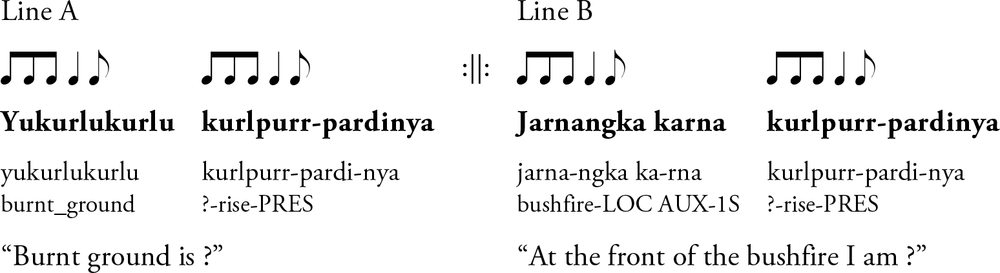

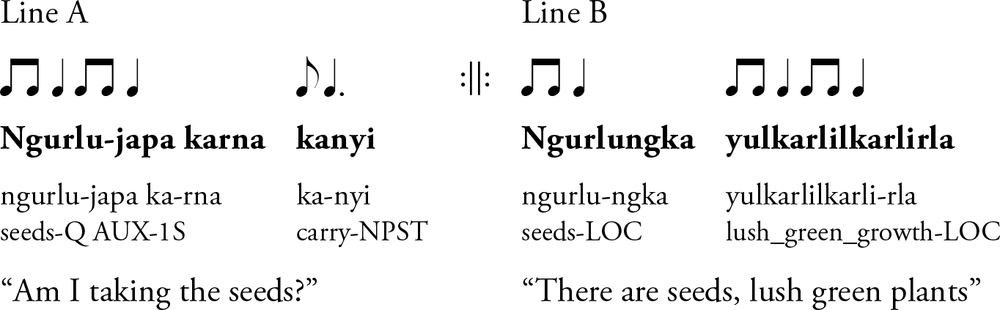

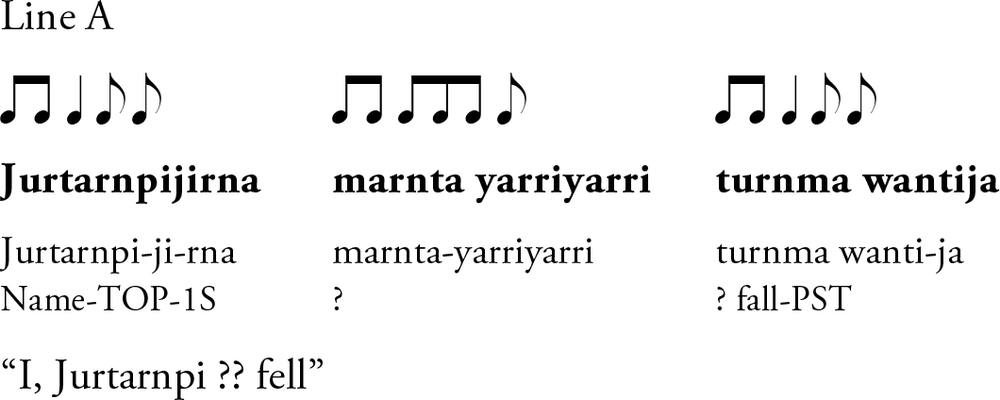

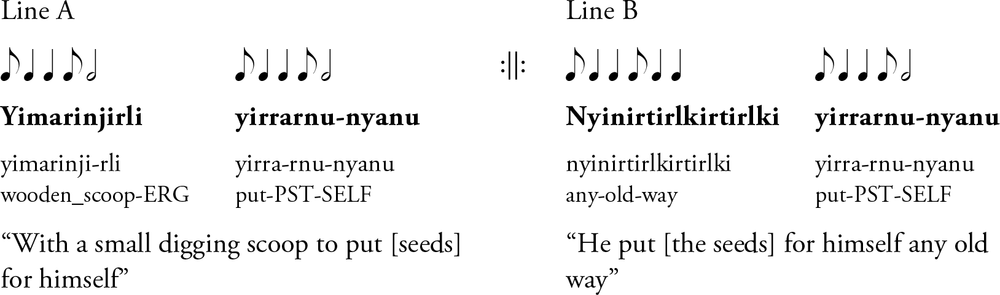

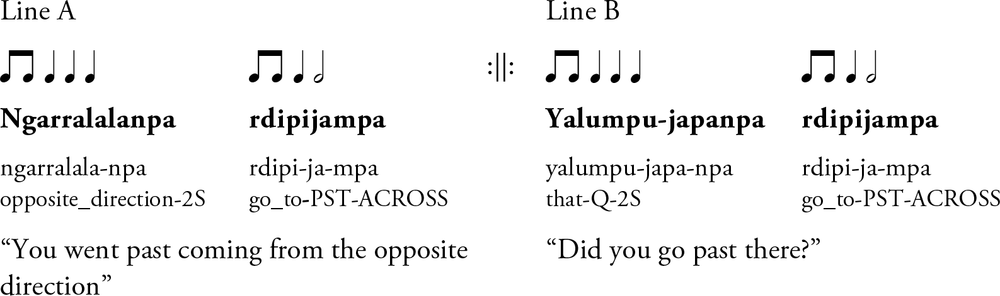

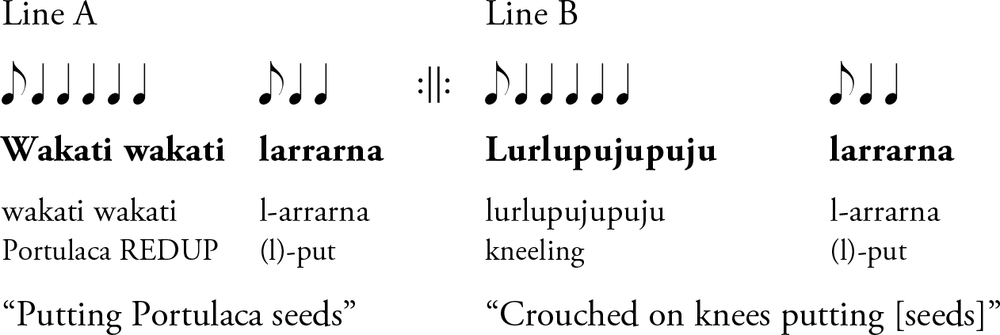

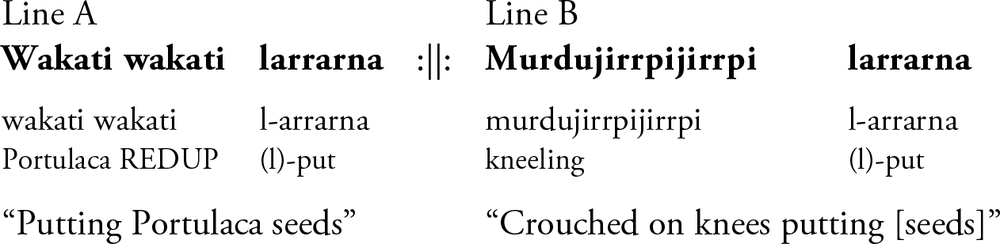

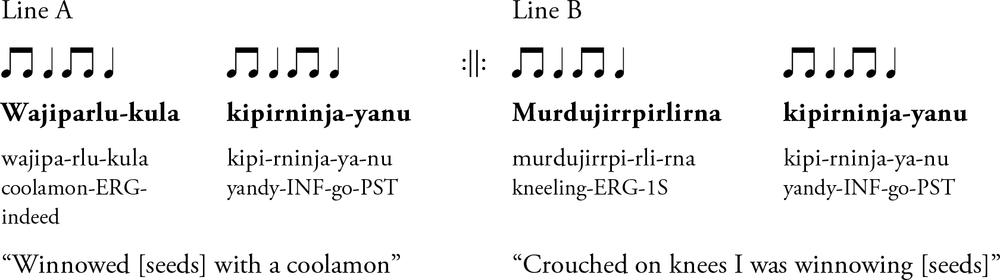

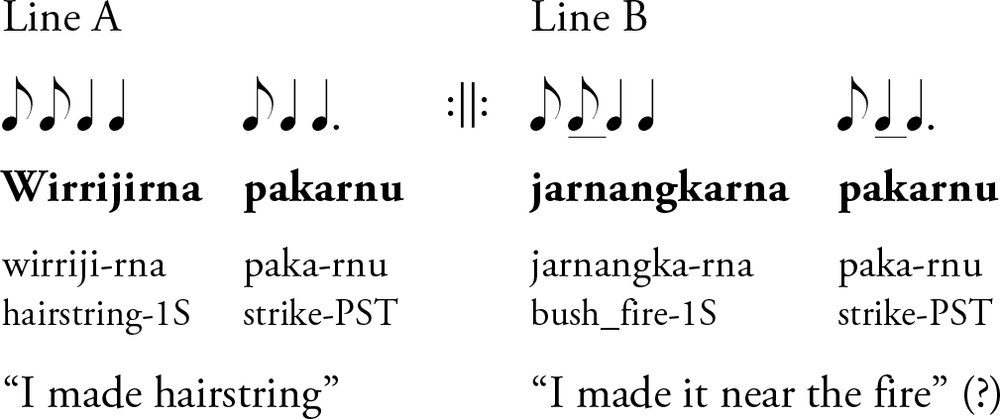

As they travel, the two Nangala women gather seeds and sit down in various places to make food from them. Specific seed-processing actions referenced in the songs include gathering seeds, threshing them, winnowing to remove chaff and husks, yandying to separate seeds from other material, and grinding and preparing seedcakes (Curran et al. 2019).13 For example, Verse 2 refers to specific winnowing actions performed by the ancestral Nangala women (using a coolamon, sitting on their heels to winnow by tossing the seeds up in the air for the wind to blow away the chaff; Example 6.1).

Example 6.114

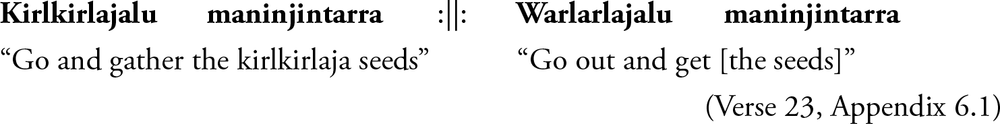

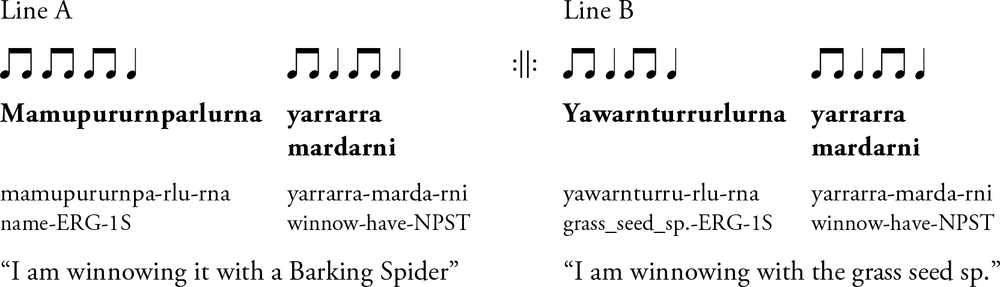

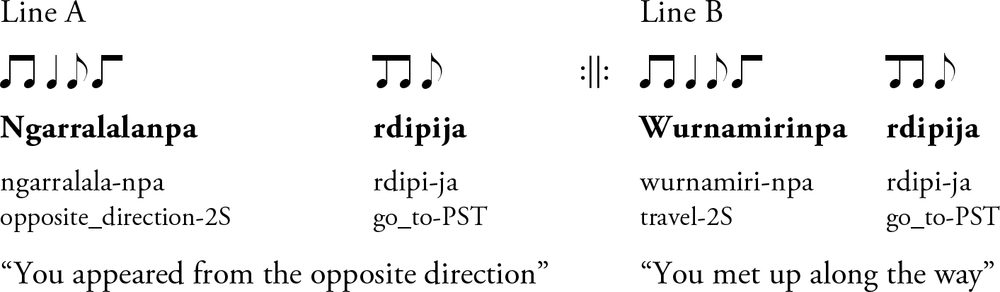

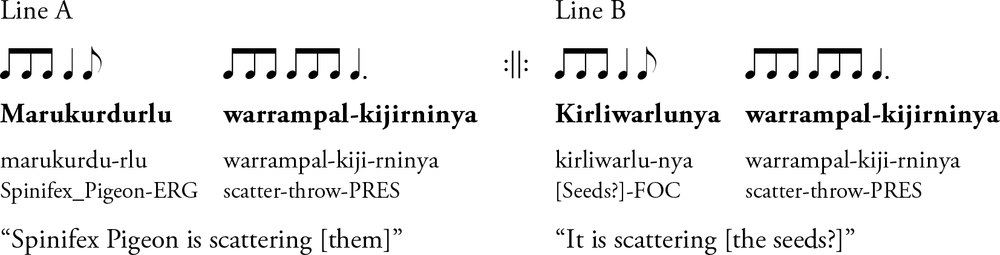

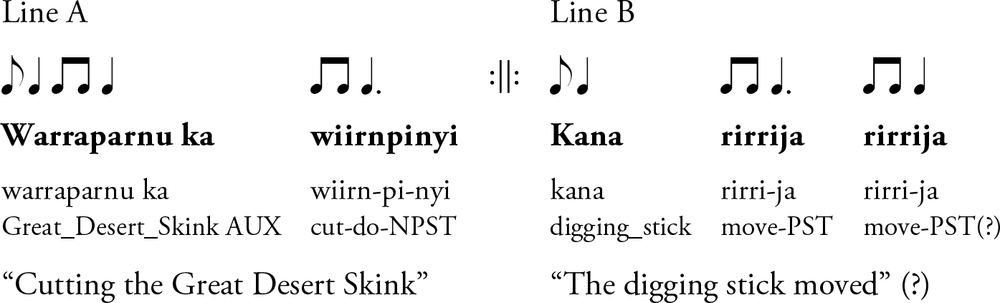

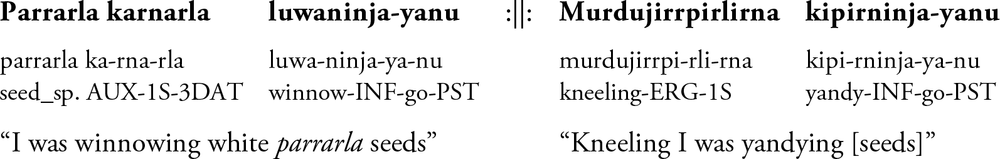

For those who know Jipiranpa Country well, the specific plants and animals mentioned in the songs (e.g., Verses 23 and 8) may provide indirect clues to the specific tracts of Jipiranpa Country where the named biota typically occur (Example 6.2).

Example 6.2

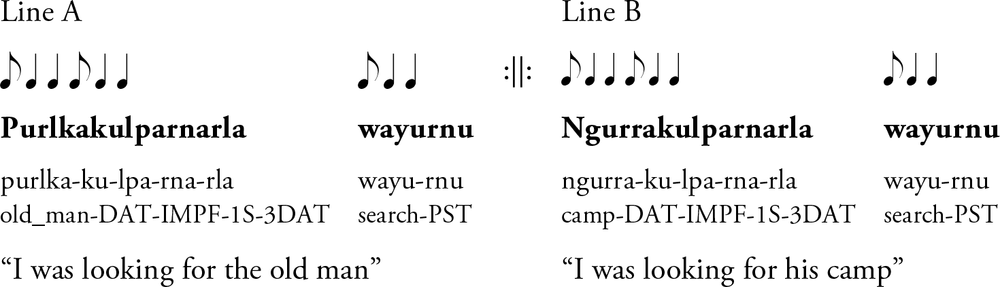

Expert knowledge of ancestral ceremonies and stories

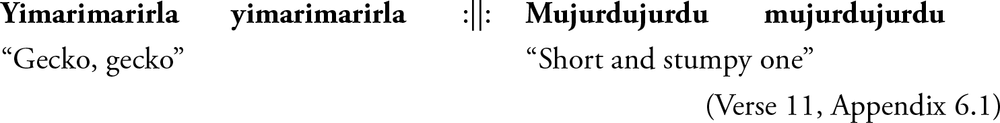

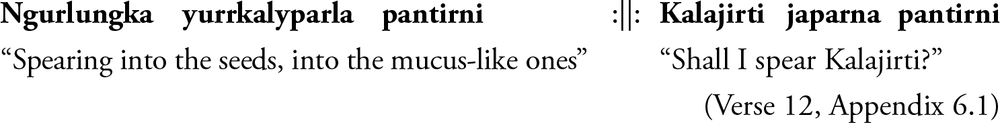

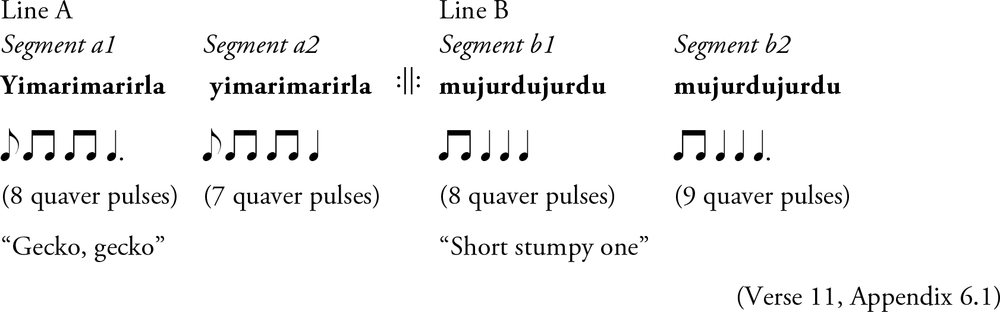

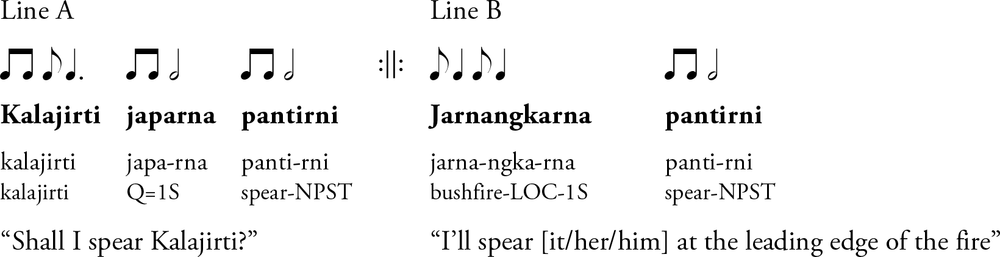

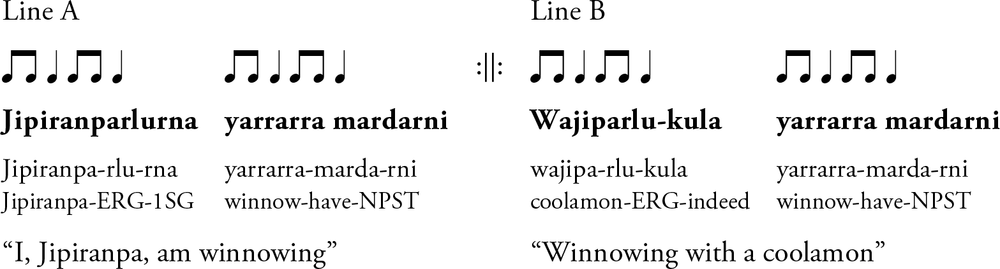

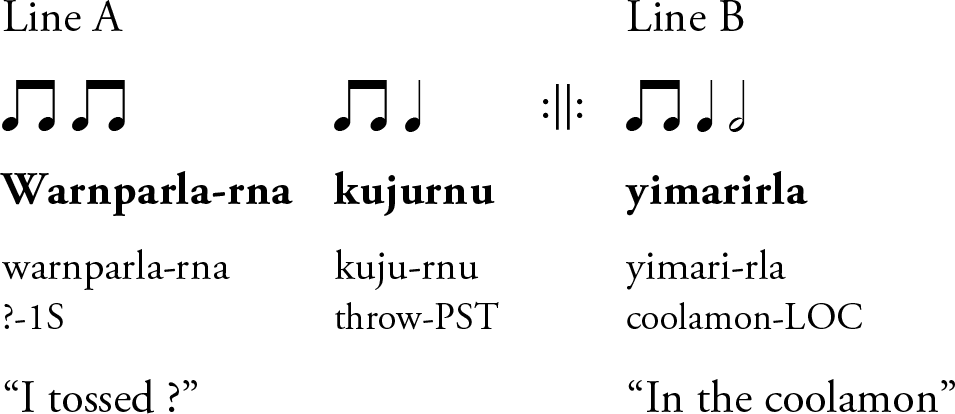

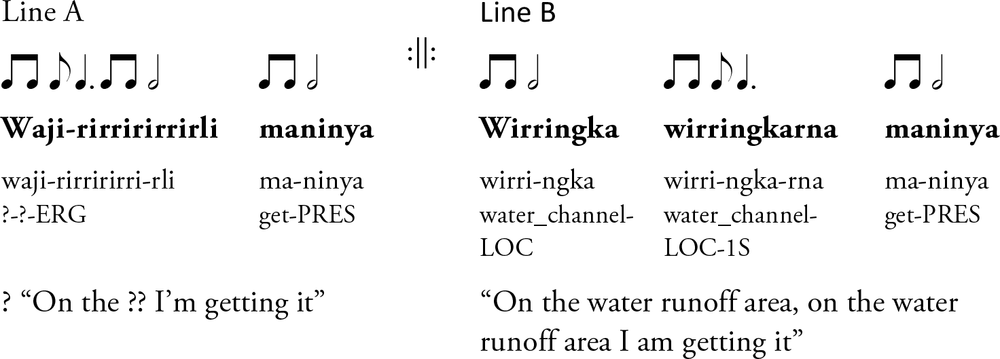

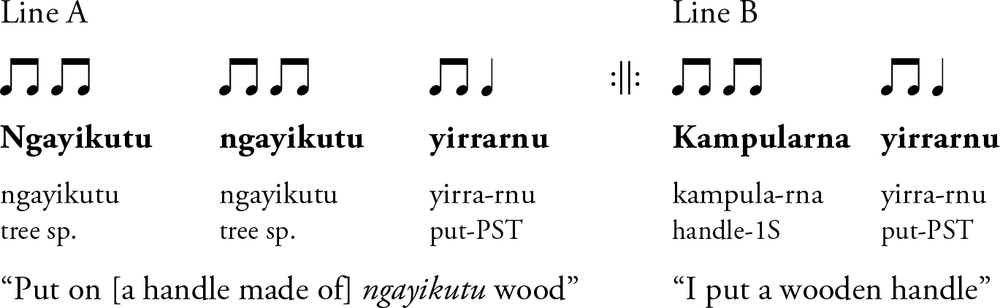

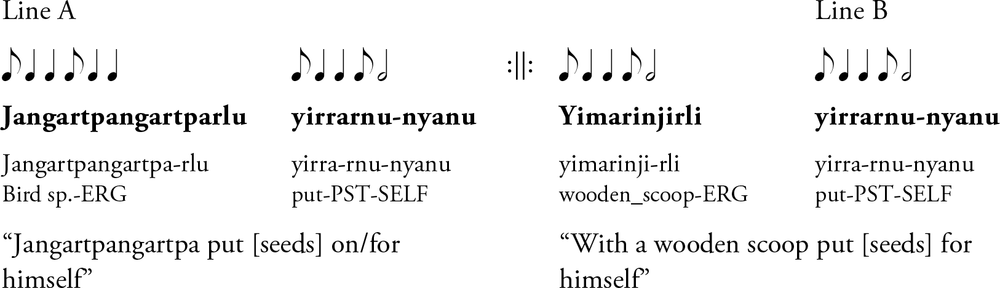

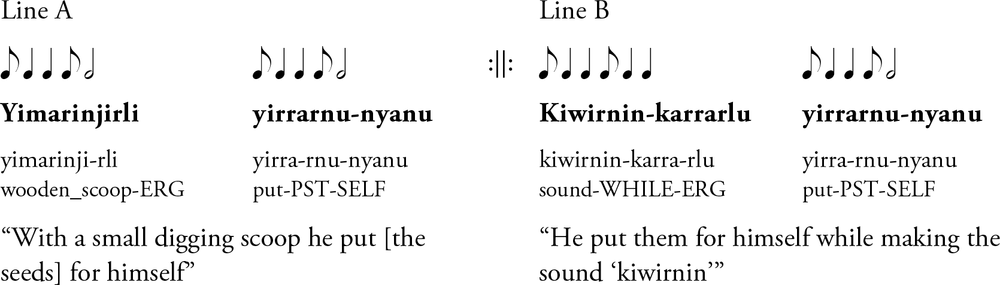

The Jakamarra who is following the two Nangalas is referred to by various special names that evoke specific aspects of the ancestral story. The Jakamarra’s names include Yimarimari (e.g., Verse 11, Example 6.3) and Kalajirti (e.g., Verse 12, Example 6.4).

Example 6.3

The Warlpiri word yimarimari (alternate pronunciation yumarimari)15 refers to a specific lizard that is light in colour. Fanny Walker Napurrurla commented that this Jakamarra was also light-skinned. Napurrurla’s daughter Sarah Holmes Napangardi identified yimarimari as a lizard like a gecko but bigger with a colourful back. The word yimarimari can be analysed as a partial reduplication of yimari, a word that occurs in several other songs in the Jipiranpa set (sometimes in the form yimarinji), and that is variously translated into English as “wooden scoop”, “coolamon” or (in Laughren et al. 2022) “women’s dancing board” (see Verses 20, 27, 36, 37, 38) – all implements of similar shape that are specifically associated with women. This name for Jakamarra, then, is related to women’s activities including ceremonial activities. The other word in Verse 11, mujurdujurdu is another name for yimarimari (possibly referring to the gecko’s short fat tail; the spoken Warlpiri form is mujurdu “stumpy”).

Example 6.4

Jakamarra’s other name, based on the Warlpiri word kalajirti, refers to spinifex, a dominant and defining species of the Tanami Desert region, where Jipiranpa is located. The prickly qualities of spinifex are repeatedly referenced by the songs’ recurrent use of the verb pantirni “spear, poke” (Verses 3, 4, 12). In discussing this song in 2021, Napurrurla’s daughter Sarah Holmes Napangardi commented that people who are married wrong skin, which is common these days, are called wingki “immoral”, a concept that is related to kalajirti. This name for Jakamarra, then, evokes his activities in pursuit of his mothers-in-law.

Expert knowledge of Jipiranpa Country and its ancestral songlines

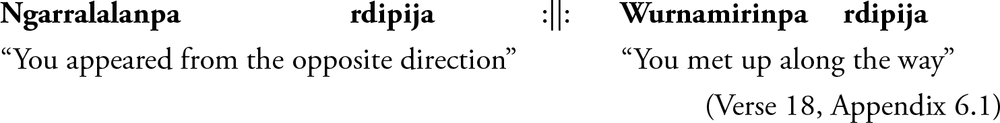

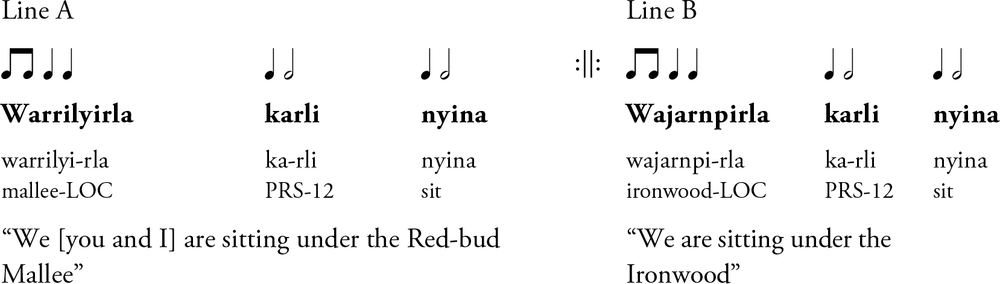

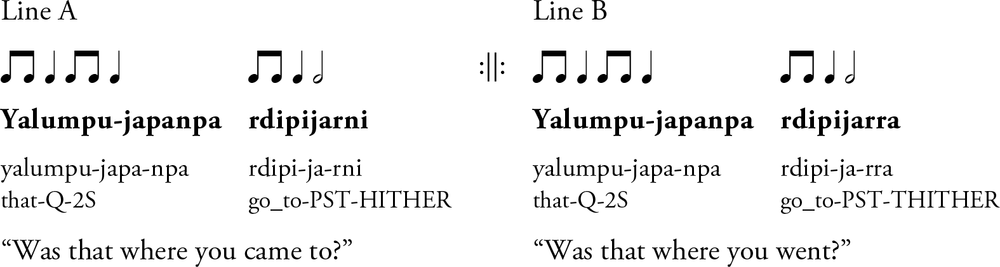

Several texts (e.g., Verse 18, Example 6.5) refer to the meeting of Jakamarra and the Nangala sisters.

Example 6.5

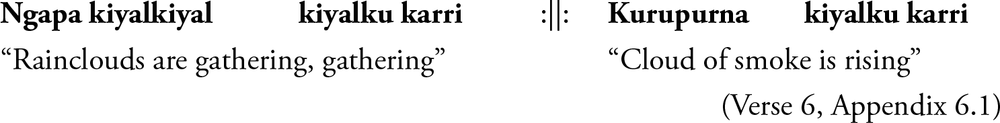

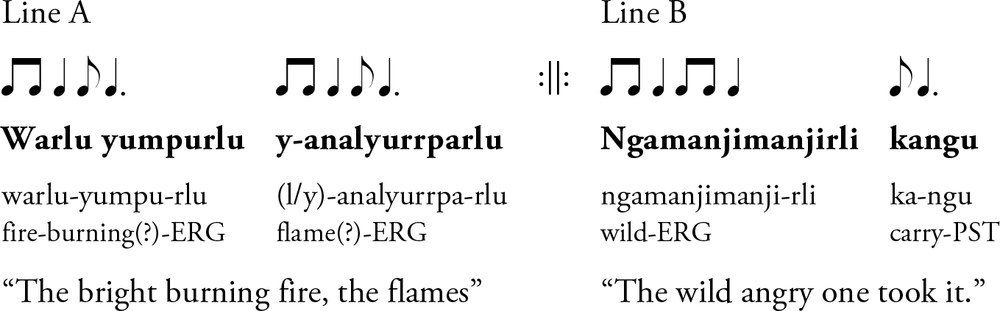

Verse 6 (Example 6.6) references Ngapa jukurrpa, the Nangalas’ Rain/Water Dreaming, the story of which also includes the generation of rainclouds from clouds of smoke. In the Jipiranpa song set, references to fire often seem to be associated with Jakamarra.16

Example 6.6

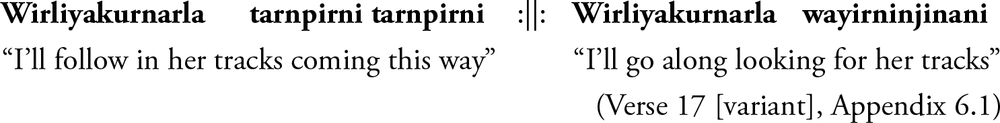

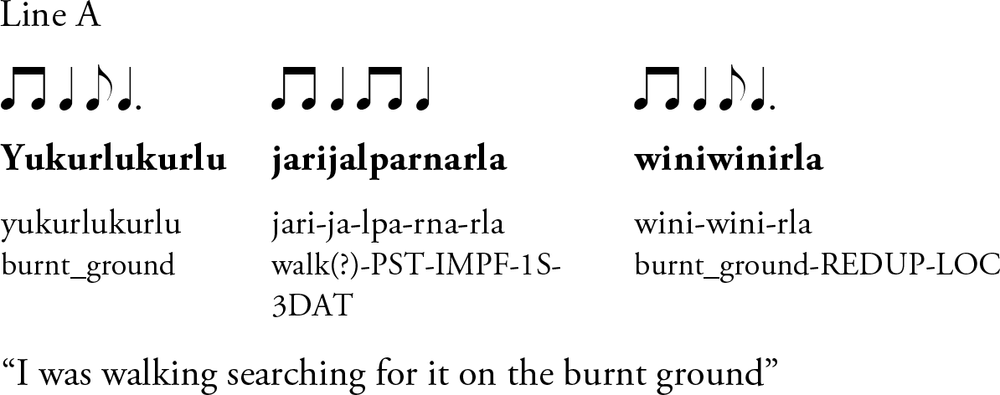

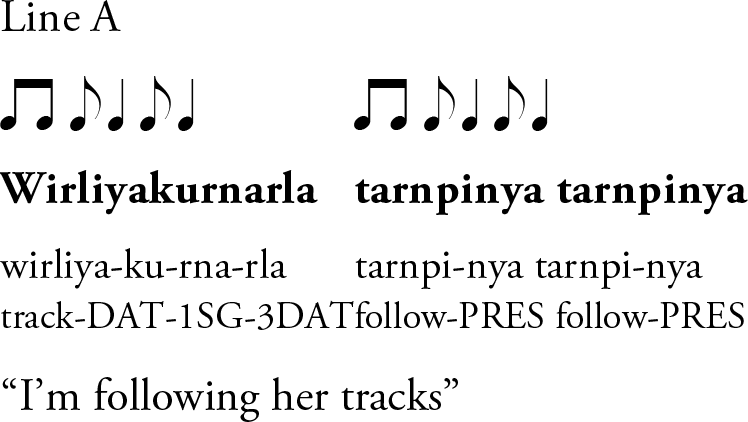

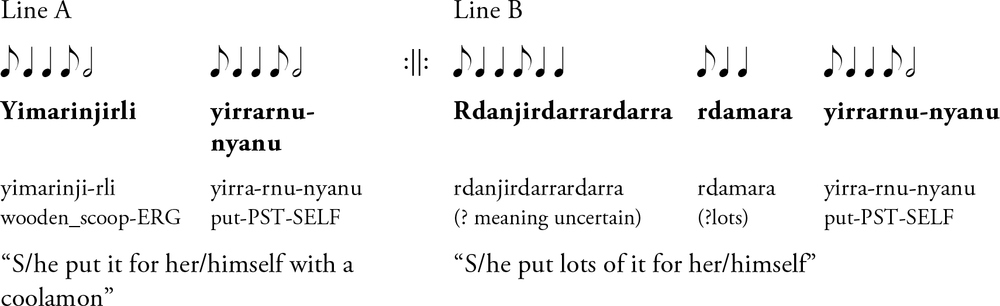

As the women travel, the Jakamarra is following their tracks and spying on them (Verse 17, Example 6.7).

Example 6.7

Jakamarra performs sorcery to get the Nangala women.

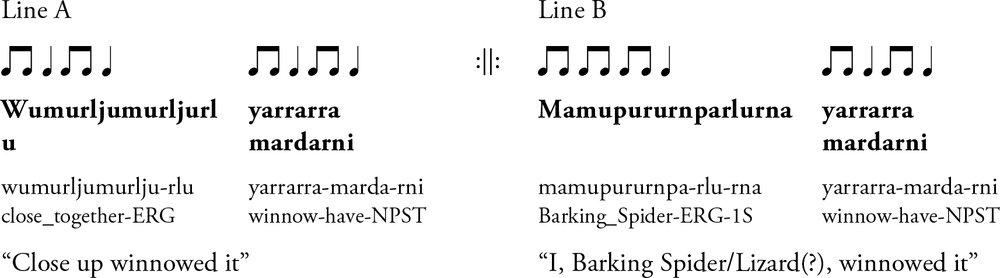

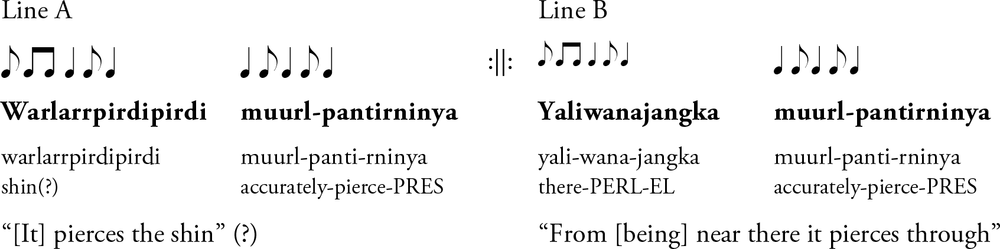

Sometimes, Jakamarra performs various acts of sorcery (e.g., Verse 42, Example 6.8; see also Verse 38) to bring the Nangala sisters under his control.

Example 6.8

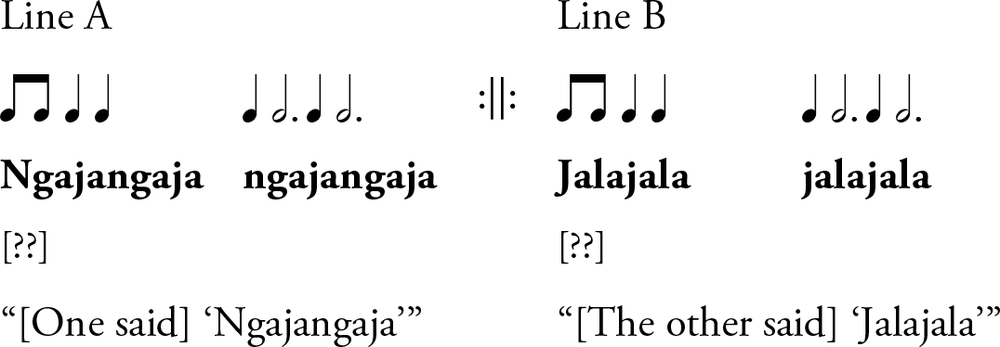

Some of Jangala’s tricks include shapeshifting as a type of spider or lizard (as already seen in Verse 11, Example 6.3 above). The women notice various odd things as Jakamarra manifests in a variety of forms (e.g., Verse 10, Example 6.9; see also Verse 34).

Example 6.9

The mamupururnpa winnowed by the Nangalas along with their grass seed provides a dilemma for interpretation and, thus, translation. While the definition in the Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary (Laughren et al. 2022) is “barking spider” (a translation affirmed by Napurrurla’s daughters in 2021), in 2010, Napurrurla herself commented that mamupururnpa was “a tiny lizard mixed in with the seeds being winnowed”. Warlpiri translator Theresa Ross Napurrurla suggested that in this context, the translation could be “thing making a humming sound”, a common attribute of both barking spiders and some species of gecko. It is possible that the word mamupururnpa could be derived from mamu (the word used in Pintupi and other Western Desert languages for an evil spirit, as well as in expressions meaning “clever, knowing, skilful, tricky”) with the addition of puru “hidden, covered” (plus the endings -rn + -pa). According to the Pintupi dictionary, mamu is an invisible spirit that hides in dark places and looks out to harm humans (Hansen and Hansen 1992, 53–54). In this light, it is plausible that in this verse, mamupururnpa refers to Jakamarra under a different guise – a man hiding away from the Nangalas but intending to have sex with them, so needing to get close to them surreptitiously.

Expert musical knowledge

Although musical settings of yawulyu verses can be quite diverse in terms of text repetitions and other conventions for text-setting,17 there are well-established norms for Central Australian song performance. These norms are established and communicated in performance, in which a group of women, led by one or two senior singers (usually kirda), sing verses in a sequence decided by the song leaders in discussion with senior kirda and kurdungurlu. Although there may be some negotiation in the musical details of the verse, especially when a new verse first begins to be sung, the ideal is strong unison singing of the ancestral verses. Most of the Jipiranpa verses conform to these widespread norms. For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on expert musical knowledge of the rhythmic setting of text while noting that the performance of other musical features, including melody and the alignment of text to melody, requires similar expertise.

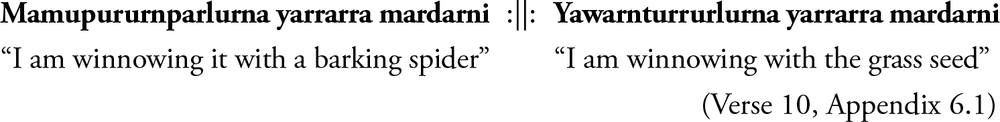

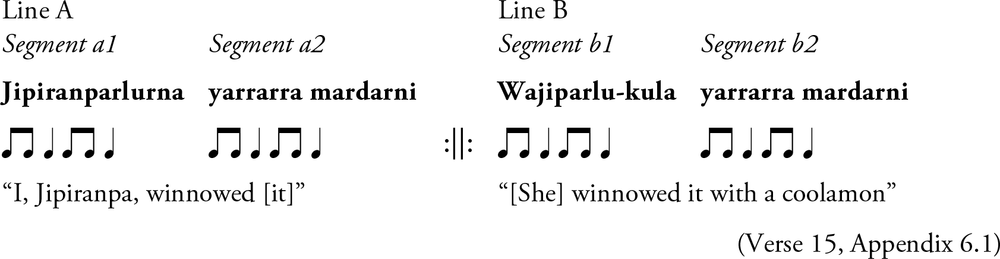

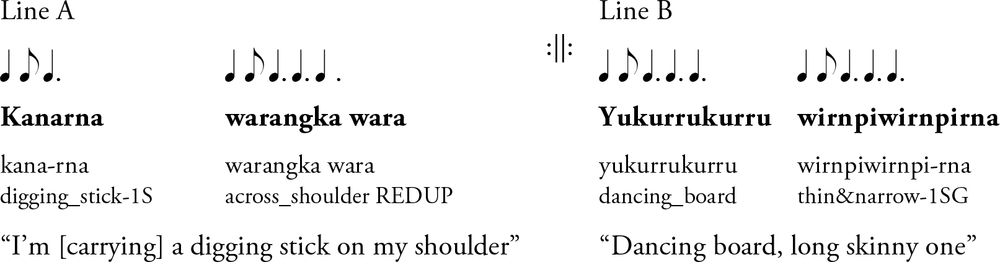

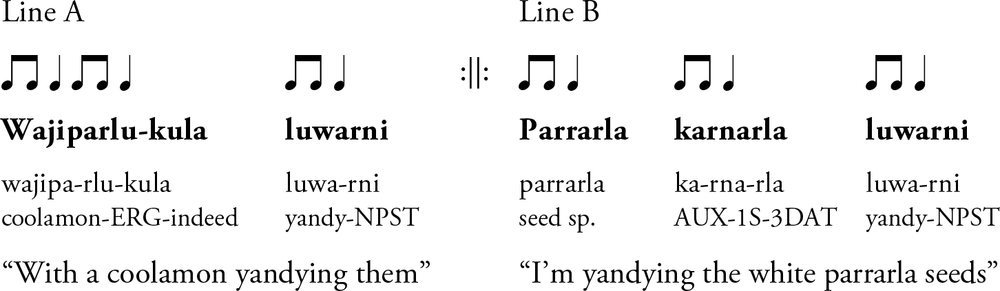

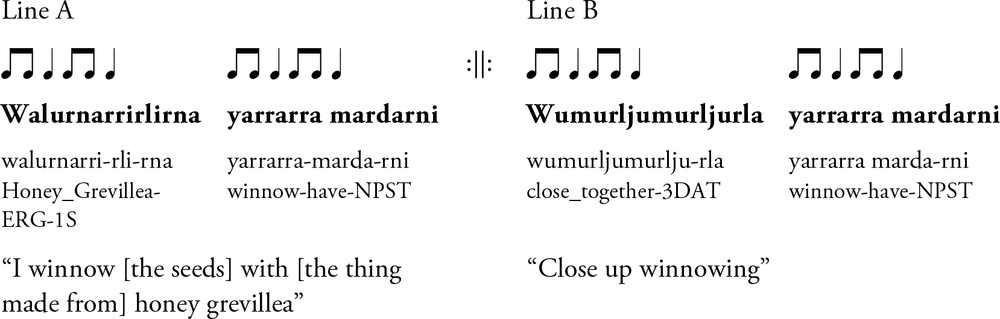

Verses typically consist of a fixed text string, usually subdivided into two, or rarely three, lines. Sometimes, these lines can be further subdivided into two or three text-rhythm segments. Normally the same text string will be set to an identical rhythm whenever it occurs, although there are some exceptions to this rule (discussed below). As an example, let us consider Verse 15 (Example 6.10).

Example 6.10

As is often the case, the two lines share part of their text (segments a2 and b2, yarrarra mardarni “winnowed”) while the first segment differs (a1 jipiranparlurna “I, Jipiranpa” and b1 wajiparlu-kula “with a coolamon”). The whole text-rhythm cycle, in this case consisting of consecutive repeats of both lines (form AABB), is repeated over and over in the course of a single item until the complete melody is presented, usually in 3–4 melodic phrases.18

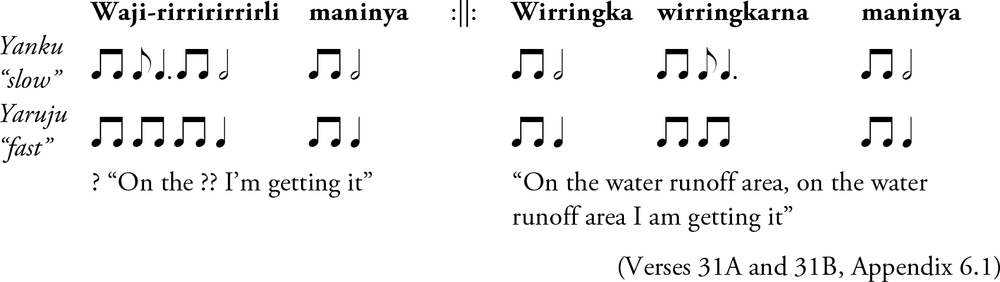

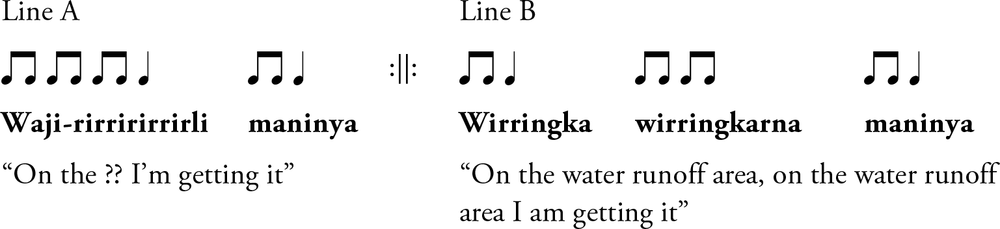

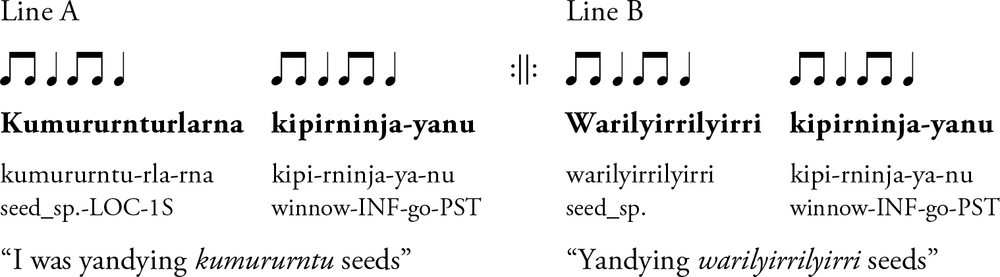

In one instance (Verse 31, Example 6.11), the same text is set to two different rhythmic settings in consecutive items of Performance 1, first presenting the “slow” version (Warlpiri yanku; 31A, transcribed in 3/4 time), then the “fast” (Warlpiri yaruju; 31B, transcribed in 2/4 time). In full performances including dance, different dance movements would be performed to match these “slow” and “fast” rhythmic types.

Example 6.11

Due to the existence of these two rhythmic settings for Verse 31, there are 48 rhythmic texts in total across the 47 verses in the Jipiranpa corpus.

Standard features of rhythmic text in Jipiranpa verses

We have identified five common features of the text-rhythm settings of Jipiranpa verses, whose distribution across the corpus of 48 Jipiranpa rhythmic texts is shown in Table 6.3.19 In each case, the vast majority of verses adhere to a pattern we will call “standard”, shown on the left of the table, with a minority, shown on the right, displaying non-standard features.

Table 6.3 Standard and non-standard forms of five rhythmic text features and their distribution across the corpus of 48 rhythmic texts.

| Feature | Standard | n/48 | Non-standard | n/48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verse structure | AABB | 44 | Other (A, AB) | 4 |

| Line length equality | Equal (lines equal duration) |

37 | Unequal (4:3, 3:2, 5:4, 9:7) |

11 |

| Text meter type | Simple: 2/4 (fast), 3/4 (slow) |

30 | Other (3/8, 5/8, 6/8, additive) |

18 |

| Stress alignment (left edge) | Yes | 35 | No | 13 |

| Longest note (right edge) | Final | 45 | Non-final | 3 |

- Verse structure: 44 of the 48 rhythmic texts in the corpus have the text repetition pattern AABB (i.e., where the text/rhythm cycle is “doubled” – comprised of two consecutive repetitions of each text line pair). Only four rhythmic texts (7, 11, 13 and 33) follow a non-standard pattern, with a single line A (texts 7 and 33) or two unrepeated lines AB (texts 11 and 13).

- Line length: 37 of the 48 rhythmic texts in the corpus have the same rhythmic duration in both lines of a text couplet or, in the case of a single line text, each segment (Verses 7 and 33).

- Text meter type: A majority of verses in the corpus (30) are in a simple meter: 2/4 for fast songs and 3/4 for slow songs. A variety of other rhythmic meters can be found: some verses are set in 3/8, 5/8, 6/8 or additive meter.

- Stress alignment (left edge): The standard for this corpus (in 35 out of 48 rhythmic texts) is for the musical stress to align with phonological stress in Warlpiri on the first syllable of the phonological phrase (the “left” edge of the text segment; Turpin and Laughren 2013). From a rhythmic perspective, we could say that the first syllable falls on a beat. In 13 of the 48 rhythmic texts, the initial syllable of the text string is unstressed (i.e., set to an upbeat or anacrusis); thus, rhythmic stress is misaligned with normal word-initial stress in spoken Warlpiri.

- Longest note (right edge): 45 of the 48 rhythmic texts follow the general convention of having the final note of a line or segment (the “right” edge of the phonological phrase) being the longest or equal longest in the line.20 Three rhythmic texts violate this convention (Verses 18, 25 and 33).

As an example of standard text-setting, consider again Verse 15 (Example 6.12):

Example 6.12

- Verse structure: Each line of rhythmic text is repeated, yielding the standard verse structure AABB.

- Line length equality: The two lines are exactly equal in rhythmic duration and thus standard. Indeed, in this case, they are also identical in rhythm, each consisting of 4 repetitions of the core rhythmic cell (quaver-quaver-crotchet).

- Text meter type: The rhythmic meter is a simple type (2/4) and thus standard.

- Stress alignment (left edge): On the left edge, stress is standard, aligning with the first syllable of each line and, indeed, of each word within the line.

- Longest note (right edge): On the right edge, the final note in each line is equal to the longest note occurring within the line (a crotchet) and thus standard.

Verse 15 thus conforms to all five of the standard text-setting conventions for this song set, as outlined in Table 6.3.

Transgression of musical norms in Ngurlu yawulyu from Jipiranpa

By contrast to the text-setting norms set out above, the predominantly non-standard text-setting of Verse 11 is set out below (Example 6.13).

Example 6.13

- Verse structure: This text appears to be AABB in form, but the duration of the final long note in each half-line varies between a dotted crotchet (when the immediately following segment begins with an upbeat) and a crotchet (when the immediately following segment aligns word stress and musical stress on the first syllable). Therefore, it must be analysed as AB in form and thus non-standard.

- Line length equality: The two lines are of unequal rhythmic duration, with Line A consisting of 15 quaver values (8 + 7) and Line B consisting of 17 quaver values (8 + 9). This feature is classified as non-standard.

- Text meter type: The base rhythmic meter is indeterminate, totalling 15 quaver pulses in Line A and 17 quaver pulses in Line B. This meter is classified as non-standard.

- Stress alignment (left edge): Stress alignment differs between the two lines, with Line A beginning with an unstressed short note, misaligning with Warlpiri’s word-initial stress, while Line B begins on the beat, thus aligning with expected word stress. The misalignment in Line A means that for this feature, too, the text-setting is classified as non-standard.

- Longest note (right edge): This is the only text-setting convention this rhythmic text seems to follow, but even here the situation is complex. In Line A, the longest note value (dotted crotchet) occurs at the end of segment a1, rather than at the end of the whole line (where segment a2 finishes with a crotchet). In Line B, the dotted crotchet occurs at the end of segment b2, coinciding with the line-final position. Because both lines end with a longer note value, on balance, we have classified this feature as standard.

Thus, Verse 11 uses non-standard text-setting conventions in four of the five features identified in Table 6.3, and even the fifth feature (placement of longest note) differs in some respects from the norm.

Distribution of text-setting features according to song theme

In these Ngurlu yawulyu songs from Jipiranpa, particular themes seem to be marked by the use of standard or non-standard musical conventions. We have classified the 48 rhythmic texts in the corpus into three thematic groups according to the type of activity represented or referenced. Twenty-one of the 48 verses are about seed processing or related activities of the Nangala women; 19 refer directly or indirectly to Jakamarra and his activities; and a further eight verses are presently unclassified or ambiguous, sometimes due to lack of discussion with Fanny Walker Napurrurla.

If we consider the distribution of these thematic groups against the proportion of standard to non-standard musical features for each of the 48 rhythmic texts, the following pattern emerges (see Table 6.4).

Table 6.4 Distribution of standard text-rhythm features according to thematic groups.

| Thematic groups | ||||

| Feature distribution strength | Seed processing | Jakamarra | Unclassified | TOTAL |

| 5/5 standard | 15 | 2 | 3 | 20 |

| 4/5 standard | 2 | 9 | 4 | 15 |

| 3/5 standard | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| 2/5 standard | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| 1/5 standard | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 21 | 19 | 8 | 48 |

Table 6.4 shows that the majority of rhythmic texts associated with the Nangalas’ seed processing (15 of 21 verses) conform completely to the standard text-rhythm features as outlined in Table 6.3, while all except two verses (17/19) dealing with the activities of Jakamarra and his encounter with the women have at least one non-standard feature. Thus, we suggest that Jakamarra’s norm-defying behaviour in pursuing his two mothers-in-law is reflected in the preponderance of non-standard text-rhythm conventions in verses that concern him. Perhaps the musical rule-breaking in Jakamarra’s verses reflects his pursuit of “wrong way” social relationships.

Conclusion

As is widely recognised, song texts can be very difficult to interpret.21 Deciphering and interpreting song texts can be even more difficult when the principal performers and owners have passed away and ways of life have changed dramatically so that there is no longer a wide understanding of some of the practices and domains of expert knowledge that are embedded in the song texts. This is the situation of many contemporary Warlpiri people who may now have grown up in communities far from their ancestral homelands (Barwick, Turpin and Laughren 2013; Wild 1987).

Sarah Holmes Napangardi, Fanny Walker Napurrurla’s eldest daughter and kurdugurlu for these Ngurlu songs from Jipiranpa, stated, “I grew up on ngurlu”;22 however, by the time their family was living in Alekarenge, her mother would still sing yawulyu, but only a few. She taught Sarah some songs. In 2010, Napurrurla herself commented that:

The young girls still dance and get painted up, but they don’t sing. They don’t know the songlines. We older women paint up the young women and young girls. The young girls dance with the paintings we put on them.23

Napurrurla’s daughters agree that understanding their mothers’ songs now can be “a little bit hard”.24 We suggest that Elders’ often-expressed wishes for teaching and learning of yawulyu songs to take place “on Country” (Barwick, Laughren and Turpin 2013) recognise the power of situational learning to integrate multiple domains of expert knowledge. Contemporary Indigenous Ranger programs across Australia are increasingly incorporating cultural activities into their land management activities (Ens et al. 2016). For example, the already cited account of Napurrurla’s final visit to Jipiranpa was facilitated by the Indigenous Rangers from the nearby Warlpri community of Willowra and bolstered her daughters’ “feeling for that Country” and its milarlpa (ancestral people).25 Similarly, the Southern Tanami Ranger Group, with leadership from Enid Nangala Gallagher, Alice Nampijinpa Henwood and other Elders, has supported the creation of resources for song learning that are recorded and developed on Warlpiri Country.26 This seems to be one important arena for Warlpiri people to expand their activities to support intergenerational transmission of expert knowledges and their contexts.

In compiling this chapter, Barwick and Laughren have been mindful of the general risk of misinterpretation in intercultural contexts and of the related specific issue that our attempts to write down and interpret the “hard” language of the yawulyu Jipiranpa verses may contain errors. Recovering the correct text from audio recordings – the starting point of our work – is an exercise fraught with difficulty (Bracknell 2017; Hercus and Koch 1995; Turpin and Laughren 2013), and there are also acknowledged difficulties in translating poetic language with its use of esoteric, oblique and sometimes ambiguous language (Barwick 2011; Koch and Turpin 2008; Walsh 2007), not to mention the required specialist contextual knowledge of seed-processing practices, Jipiranpa Country and its ancestral stories. Musical features of Central Australian songs are similarly highly complex and sometimes difficult to interpret (Ellis 1985; Ellis and Barwick 1987). Any errors we have made risk misleading or disempowering contemporary and future Warlpiri people, who are the rightful holders of this knowledge tradition. We have tried to counter these risks by checking our part of the work, firstly with Fanny Walker Napurrurla and her family and secondly with Warlpiri experts in language and culture. We respectfully offer our part of this work as a tribute to our co-author, the great ceremony woman, Fanny Walker Napurrurla, asking that readers take the written versions of the songs we present here not as authoritative exegesis but more as suggestions or pointers to the full richness of yawulyu as performed.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the family of Fanny Walker Napurrurla, including Sarah Holmes Napangardi, Jessie Simpson Napangardi and Judith Robertson Napangardi, for their interest, comments and permissions. Thanks also to Theresa Ross Napurrurla for assistance with Warlpiri translations; to David Nash, Jane Simpson and Myfany Turpin for their ongoing support through the many years it has taken to complete this research; and to Gretel Macdonald for research assistance in the latter stages of the project. At various times, fieldwork has been funded by the Australian Research Council Queen Elizabeth II Research Fellowship (1992–1996), the Australian Research Council Linkage project LP0989243 (for interviews undertaken in 2010), the Australian Research Council Linkage project LP160100743, the Kurra Aboriginal Corporation, Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications, and the University of Sydney. Thanks to Myfany Turpin and anonymous peer reviewers for additional comments that have improved the chapter.

References

Barwick, Linda. 1989. “Creative (Ir)regularities: The Intermeshing of Text and Melody in Performance of Central Australian Song”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 12–28.

Barwick, Linda. 2011. “Including Music and the Temporal Arts in Language Documentation”. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork, edited by Nicholas Thieberger, 166–79. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199571888.013.0008

Barwick, Linda. 2023. “Songs and the Deep Present”. In Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep History, edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker and Jakelin Troy, 93–122. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press and the American Philosophical Society.

Barwick, Linda, Bruce Birch and Nicholas Evans. 2007. “Iwaidja Jurtbirrk Songs: Bringing Language and Music Together”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 6–34.

Barwick, Linda, Mary Laughren and Myfany Turpin. 2013. “Sustaining Women’s Yawulyu/Awelye: Some Practitioners’ and Learners’ Perspectives”. Musicology Australia 35(2): 191–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2013.844491

Bell, Diane. 1993. Daughters of the Dreaming. 2nd ed. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Bracknell, Clint. 2017. “Maaya Waab (Play with Sound): Song Language and Spoken Language in the South-West of Western Australia”. In Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia, edited by Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin, 45–57. Canberra; Newcastle: Pacific Linguistics & Hunter Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2019. “‘Waiting for Jardiwanpa’: History and Mediation in Warlpiri Fire Ceremonies”. Oceania 89(1): 20–35.

Curran, Georgia. 2020. “Bird/Monsters and Contemporary Social Fears in the Central Desert of Australia”. In Monster Anthropology: Ethnographic Explorations of Transforming Social Worlds through Monsters, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Geir Henning Presterudstuen, 127–42. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350096288.ch-008

Curran, Georgia, Linda Barwick, Myfany Turpin, Fiona Walsh and Mary Laughren. 2019. “Central Australian Aboriginal Songs and Biocultural Knowledge: Evidence from Women’s Ceremonies Relating to Edible Seeds”. Journal of Ethnobiology 39(3): 354–70. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-39.3.354

Dixon, R. M. W. 1980. The languages of Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donaldson, Tamsin. 1979. “Translating Oral Literature: Aboriginal Verses”. Aboriginal History 3: 62–83.

Ellis, Catherine. 1985. Aboriginal Music, Education for Living. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Ellis, Catherine. 1970. “The Role of the Ethnomusicologist in the Study of Andagarinja Women’s Ceremonies”. Miscellanea Musicologica 5: 76–208.

Ellis, Catherine and Linda Barwick. 1987. “Musical Syntax and the Problem of Meaning in a Central Australian Songline”. Musicology Australia 10: 41–57.

Ens, Emilie, Scott Mitchell L., Yugul Mangi Rangers, Craig Moritz and Rebecca Pirzl. 2016. “Putting Indigenous Conservation Policy into Practice Delivers Biodiversity and Cultural Benefits”. Biodiversity and Conservation 25: 2889–2906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1207-6

Gallagher, Coral Napangardi, Peggy Nampijinpa Brown, Georgia Curran and Barbara Napanangka Martin. 2014. Jardiwanpa Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu. Batchelor: Batchelor University Press.

Garde, Murray. 2006. “The Language of Kun-Borrk in Western Arnhem Land”. Musicology Australia 28: 59–89.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1984. “Remarks on Creativity in Aboriginal Verse”. In Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, edited by Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington, 254–62. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Hansen, Kenneth L. and Lesley E. Hansen. 1992. Pintupi/Luritja Dictionary. 3rd ed. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

Hercus, Luise and Grace Koch. 1995. “Song Styles from Near Poeppel’s Corner”. In The Essence of Singing and the Substance of Song: Recent Responses to the Aboriginal Performing Arts and Other Essays in Honour of Catherine Ellis (Oceania Monograph 46), edited by Linda Barwick, Allan Marett and Guy Tunstill, 106–20. Sydney: Oceania Publications.

Kelly, Francis Jupurrurla, dir, and David Batty, dir. 2012. Coniston. Yuendumu/Brunswick: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications/Rebel Films.

Koch, Grace and Myfany Turpin. 2008. “The Language of Central Australian Aboriginal Songs”. In Morphology and Language History in Honour of Harold Koch, edited by Claire Bowern, Bethwyn Evans and Luisa Miceli, 167–83. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Laughren, Mary, Georgia Curran, Myfany Turpin and Nicholas Peterson. 2018. “Women’s Yawulyu Songs as Evidence of Connections to and Knowledge of Land: The Jardiwanpa”. In Language, Land and Song: Studies in Honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch and Jane Simpson, 425–455. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Laughren, Mary, Kenneth Hale, Jeannie Egan Nungarrayi, Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Morton, John. 2011. “Splitting the Atom of Kinship: Towards an Understanding of the Symbolic Economy of the Warlpiri Fire Ceremony”. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Peterson, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber, 17–38. Canberra: ANU Press.

Moyle, Richard M. 1979. Songs of the Pintupi: Music in a Central Australian Society. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Nash, David. 1984. “The Warumungu Reserves 1892–1962: A Case Study in Dispossession”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 2–16.

Nash, David. 2002. “Mary Alice WARD (1896–1972)”. In Australian Dictionary of Biography (Volume 16; 1940–80 Pik–Z), edited by John Ritchie and Dianne Langmore, 490–91. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A160582b.htm

Peterson, Nicolas. 1970. “Buluwandi: A Central Australian Ceremony for the Resolution of Conflict”. In Australian Aboriginal Anthropology: Modern Studies in the Social Anthropology of the Australian Aborigines, edited by Ronald M. Berndt, 200–15. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Peterson, Nicolas and Jeremy Long. 1986. Australian Territorial Organization: A Band Perspective. Sydney: University of Sydney.

San, Nay and Myfany Turpin. 2021. “Text-Setting in Kaytetye”. In Proceedings of the 2020 Annual Meeting on Phonology, edited by Ryan Bennett, Richard Bibbs, Mykel Loren Brinkerhoff, Max J. Kaplan, Stephanie Rich, Amanda Rysling, Nicholas Van Handel and Maya Wax Cavallaro, 1–9. Columbia: Linguistics Society of America. https://doi.org/10.3765/amp.v9i0.4911

Simpson, Jane and David Nash. 1990. Wakirti Warlpiri: A Short Dictionary of Eastern Warlpiri with Grammatical Notes. Tennant Creek: Jane Simpson and David Nash.

Treloyn, Sally. 2007. “‘When Everybody There Together … then I Call That One’: Song Order in the Kimberley”. Context: A Journal of Music Research 32: 105–21.

Turpin, Myfany. 2007a. “Artfully Hidden: Text and Rhythm in a Central Australian Aboriginal Song Series”. Musicology Australia 29(1): 93–108.

Turpin, Myfany. 2007b. “The Poetics of Central Australian Song”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 100–115.

Turpin, Myfany. 2012. Kaytetye to English Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

Turpin, Myfany and Mary Laughren. 2013. “Edge Effects in Warlpiri Yawulyu Songs: Resyllabification, Epenthesis, Final Vowel Modification”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 33(4): 399–425.

Turpin, Myfany and Tonya Stebbins. 2010. “The Language of Song: Some Recent Approaches in Description and Analysis”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30(1): 1–17.

Walsh, Michael. 2007. “Australian Aboriginal Song Language: So Many Questions, So Little to Work With”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 128–44.

Watts, Lisa, April Ngampart Campbell, Clarrie Kemarr and Myfany Turpin. 2009. Mer Rrkwer-Akert [DVD]. Alice Springs: Charles Darwin University Central Australian Research Network.

Wild, Stephen A. 1984. “Warlbiri Music and Culture: Meaning in a Central Australian Song Series”. In Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, edited by Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington, 41–53. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Wild, Stephen A. 1987. “Recreating the Jukurrpa: Adaptation and Innovation of Songs and Ceremonies in Warlpiri Society”. In Songs of Aboriginal Australia (Oceania Publications), edited by Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Wild, 97–120. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Yeoh, Calista and Myfany Turpin. 2018. “An Aboriginal Women’s Song from Arrwek, Central Australia”. Musicology Australia 40(2): 101–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2018.1550141

Appendix 6.1 Verses and rhythms for Ngurlu yawulyu from Jipiranpa

Ngurlu yawulyu songs from Jipiranpa are ordered in this Appendix following the order of Performance 3 (tape AT97/13AB), then Performance 1 (tape AT96/18AB), then Performance 4 (tape AT97/16AB_17A).

Each distinct verse is numbered 1–47 (four have text variants, and one has both slow and fast versions, making a total of 48 distinct rhythmic texts). The verse number is followed by an indication of how many times the verse occurs in the corpus (giving song item codes as per Barwick’s database). For each verse, the lines in the text (usually two) are presented in a series of text/rhythm tables following the order and line repetition structure first heard; it is not uncommon for text line order to be reversed in some items.

We use the musical repeat symbol :||: for internal repetition of each line (AABB); and the slash symbol / to separate unrepeated lines (AB).

The first line indicates syllabic rhythm; the second line is the Warlpiri text written in standard Warlpiri;27 the third is morphemic representation of the text; the fourth morpheme-by-morpheme glossing; and the last line is a free translation.

Comments by kirda Fanny Walker Napurrurla (FW) on 18–19 July 2010 (recorded on T100718a and T100719a), by kurdungurlu Sarah Holmes Napangardi (SH) in 2021, by translator Theresa Ross Napurrurla (TR), or by the transcribers (Mary Laughren [ML] and Linda Barwick [LB]) are presented when relevant beneath the text/rhythm tables.

Abbreviations used in glosses:

1 = first person; 2 = second person; 3 = third person; 12 = first and second person dual (inclusive); AUX = auxiliary; CS = changed state; DAT = dative case; EL = elative case; ERG = ergative case; FOC = focus; IMP = imperative; IMPF = imperfective aspect; INC = incipient; INF = infinitive; LOC = locative case; NPST = non-past tense; PERL = perlative case; PL = plural; PRES = present tense; PST = past tense; Q = question; REDUP = reduplication; S = subject; TOP = topic.

Verse 1

5 items (AT9618A-s20_22; AT9713A-s01_02)

Comments:

FW: Puna-lpa yarrarra-mardarnu “She was winnowing ashes”. Cooking ngurlu “seeds” in hot ashes.

ML: The frequent ending -rna (as on puna-ngka) is ambiguous between the first-person singular subject enclitic pronoun “I” and an epenthetic “vocable” element added to a phrase to provide enough syllables to match the rhythmic pattern (Turpin and Laughren 2013, 400). We will gloss all instances as “1S”, but some should probably be analysed as a vocable.

Verse 2

3 items (AT9713A-s03_05)

Comment:

ML: Murdupurrju in line B, based on murdu “knee”, is equivalent to murdujirrpijirrpi in Verse 44 and murdujirrpi in Verse 2 (variant) and Verse 45.

Verse 2 (variant)

4 items (AT9618A-s23_26)

Verse 3

2 items (AT9713A-s11_s12)

Comments:

SH: Sarah explains that people who are married wrong skin, which is common these days, are called wingki, which is related to kalajirti.

ML: Jarna refers to a bush or grass fire, particularly the leading edge where the flames are active, and where animals escaping fire were more easily speared.

ML: Kalajirti is a type of Gummy Spinifex grass and is also the name of a man who is one of the ancestral beings celebrated in this ceremony.

Verse 4

3 items (AT9618A-s34; AT9713A-s13_14)

Comment:

FW: Women sing this song to attract their boyfriends. It is a “love” song or yilpinji.

Verse 5

6 items (AT9618A-s36_38; AT9713A-s15; AT9713A-s39_40)

Comments:

FW: Ngurlu, panturnulpa Kalajirtirli “Kalajirti was piercing/poking the seeds”.

ML: The verb pantirni denotes a sharp pointed entity coming into contact with something: corresponding to English verbs “poke”, “stab”, “pierce”, “spear”. Although we gloss all occurrences as “spear”, these other verbs might better describe some events.

ML: Yurrkalypa in this context may refer to the shiny melted spinifex resin following bushfire.

Verse 6

5 items (AT9618A-s04_06; AT9713A-s16_17)

Comment:

FW: The cloud of smoke from the bushfire rises and causes rainclouds to form.

Verse 7

10 items (AT9618A-s11_13; AT9713A-s18_20; AT9713A-s44_45; AT9713B-s22_23)

Comments:

FW: The people were walking on the burnt ground.

ML: The origin and meaning of past tense verb jari-ja is unclear. Jari denotes thick scrub.

Verse 8

5 items (AT9713A-s21_22; AT9713A-s53_55)

Comment:

LB: Musical settings of this verse vary. In AT9713A-s21_22, singers consistently perform the long notes as minim, used here. In AT9713A-s53_55, singers audibly disagree regarding the duration of long notes; some singers perform consistent dotted minims.

Verse 9

2 items (AT9713A-s23_24)

Verse 10

6 items (AT9618B-s02_04; AT9713A-s25_27)

Comments:

FW: Mamupururnpa was a tiny lizard mixed in with the seeds being winnowed; yawarnturru seeds were winnowed by the Dreaming ancestor.

SH and JL: Mamupururnpa identified as barking spider.

TR: In translating this text, suggested “thing making a humming sound” – as do both barking spiders and fat-tailed geckos.

ML: An alternative reading would be that both mamupururnpa and yawarnturru are names of the ancestor(s) this verse celebrates: A. “I, Mamupururnpa, am winnowing”; B. “I, Yawarnturru, am winnowing”.

Verse 11

5 items (AT9618A-s17_19; AT9713A-s37_38)

Comments:

FW: Mujurdujurdu was another name for Yimarimari, a Jakamarra from Jipiranpa who followed his mothers-in-law, two Nangala women.

SH: Sarah identifies yimarimari as the tiny lizard mixed in with the seeds. She explains that it is like a gecko but bigger with a colourful back. Mamupururnpa is identified as a barking spider.

ML: Spoken form is unreduplicated mujurdu. Partial reduplication (mujurdu-jurdu) is commonly employed in songs.

Verse 12

1 item (AT9713A-s41)

Verse 13

2 items (AT9713A-s42_43)

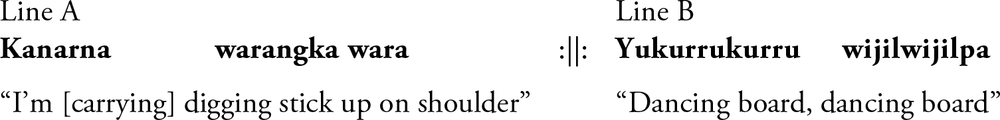

Comments:

FW: Kanalpa jinta kangu yukurrukurrurlu wijilpajilparlu. “The yukurrukurru ‘Dancing Board’ Dreaming carried one digging stick across her shoulders.”

ML: Another type of partial reduplication found in songs is exemplified by warangka wara in which only the initial two syllables are reduplicated; in spoken Warlpiri, the fully reduplicated warangka-warangka may be used.

ML: Verse 13 evokes women dancing and acting out part of the story of this song set.

LB: Note text repetition varies. Mostly AABB text: AABA/BAA/BBAAB.

Verse 13 (variant)

2 items (AT9618B-s15_16)

Comments:

FW: Wijilwijilpa and yukurrukurru both refer to the “Dancing Board” Dreaming.

LB: Note (mostly) AB text – order of segments in second line sometimes reversed: AA’BABA/BABA.

LB: Compared to Verse 13, this version substitutes the last word in Line B wirnpiwirnpirna “thin and narrow” with the word wijilwijilpa, a synonym for yukurrukurru “dancing board”.

Verse 14

5 items (AT9618B-s32_34; AT9713A-s46_47)

Comment:

ML: Vowel-initial Arandic words incorporated into Warlpiri songs, such as the word for Portulaca sp. in Line A, are typically sung with an initial “l” (e.g., lakati-lakati, a reduplicated word). The spoken Warlpiri name of this species is wakati as in Verse 44, line A. Note that parrarna is similar to parrarla, the name of an edible seed, which appears in Verse 39, Line B.

Verse 15

2 items (AT9713A-s48_49)

Comment:

ML: Jipiranpa is both a place name and the name of the ancestor.

Verse 16

3 items (AT9713A-s50_52)

Verse 17

3 items (AT9713A-s56_58)

Verse 17 variant

[not on original recording – sung by FW in 2010 elicitation session]

Verse 18

6 items (AT9618B-s21_23; AT9713A-s59_AT9713B-s01_02)

Comments:

FW: The paths of the Dreamings crossed as they came from opposite directions.

LB: Myfany Turpin (personal communication) points out that this verse also occurs in the Arrwek (edible seed) song set (see Yeoh and Turpin 2018, 103, verse labelled “rrwek24”). It also occurs in Jardiwanpa yawulyu (see Song 38 in Gallagher et al. 2014, 86).

In both lines, the rhythmic notation is intended to show the strongly stressed triple grouping that crosses word boundaries. This is an example of misalignment of musical stress with normal first syllable word stress in spoken Warlpiri. Note the almost identical text in Line A, Verse 41. The text here in Verse 18 is set in yaruju “fast” style, in contrast to the yanku “slow” style of Verse 41.

Verse 19

9 items (AT9618A-s07_09; AT9713B-s03_06; AT9713B-s29_30)

Comments:

FW: Smoke was rising up from the burnt ground after the fire had passed on. [Glossed analyurrpa as jarra “flame”.]

ML: The initial consonant of the vowel-initial word analyurrpa is sung variably as “y” or “l”. This word is possibly related to ngalyurrpa “flickering, blazing”, as suggested by meaning given by FW; it is also similar to kanalyurrpa “many together”.

Verse 20

2 items (AT9713B-s07_08)

Comments:

SH: Sarah suggests that rdanjirdarrardarra refers to lots of people or things there. She mentions a potential synonym jirdangarra, meaning lots of people there, as in jirdangarra nyinami kalu.

ML: Narrow wooden scoop is recorded as yimari in spoken language; yimarinji may be a song form.

Verse 21

4 items (AT9618B-s50_51; AT9713B-s09_10)

Comments:

FW: Yilpirrki-yirrarni is the same as julyurl-yirrarni “put into fire”.

ML: In one instance, Line B was sung as: pirdijirri-rna japa yilpirrki-yirra-rni.

Verse 22

4 items (AT9713B-s11_14)

Comment:

ML: We did not have the opportunity to discuss this verse with Fanny Walker Napurrurla, hence there is some uncertainty about the translation. One reviewer noted a similarity between Warumungu kiirli “seed” and kirliwarlu in Line B; however, kiirli refers to non-edible seeds that must be cleaned out of fruits before eating (equivalent to Warlpiri kurla), as opposed to edible seeds that are ground to prepare for eating. Kirliwarlu might be the name of a seed being scattered by the pigeon. Another possible parsing is kirli warlu-nya where kirli refers to something belonging to another (typically son-in-law) and warlu “fire”, so the free translation of this line might be “scattering fire belonging to son/mother-in-law”.

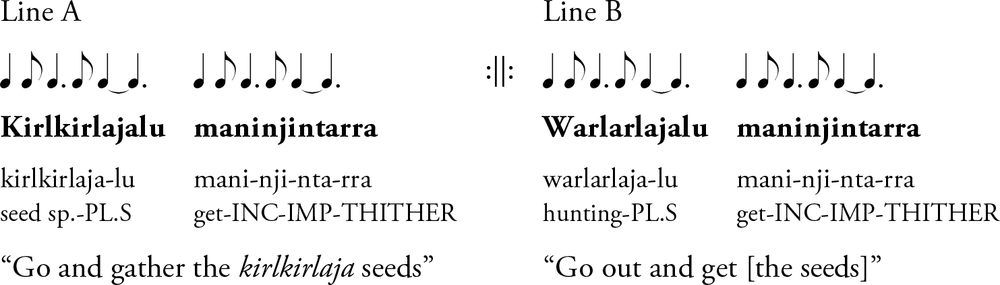

Verse 23

6 items (AT9618B-s05_07; AT9713B-s15_17)

Comments:

FW: They were collecting seeds while out gathering food.

ML: A reviewer alerted us to the link between Warumungu walala and warlarlaja “hunting” in line B; -ja may be an assertive marker added to the word of Warumungu origin.

Verse 24

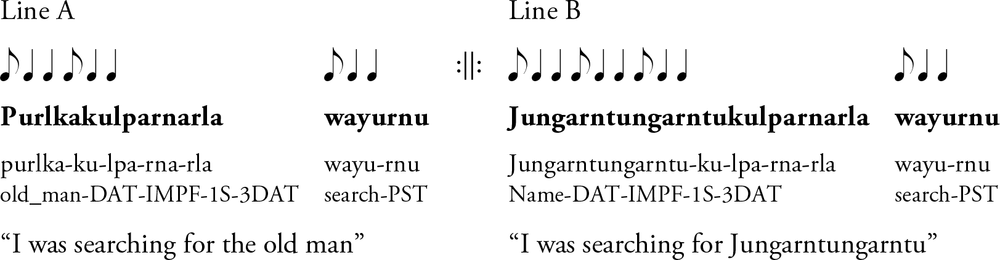

3 items (AT9713B-s18_20)

Comments:

FW commented: ngurra-ku-lpa-rna-rla “camp-DAT-IMPF-1S-3DAT”, which FW said was that they were looking for where the old man was sleeping/camping.

ML: Jungarntungarntu may be the name of a place.

LB: The line quoted by FW occurs in Verse 43.

Verse 25

4 items (AT9713B-s21; AT9713B-s39_41)

Comment:

ML: Text and interpretation are tentative, because we were unable to check the song with Fanny Walker Napurrurla in 2010. The first words of lines A and B present parallel forms, which suggests that both yankuyanku and pirlirnarda are names: yanku “slow”, pirli “stone, hill”.

Verse 26

8 items (AT9618A-s01_03; AT9713B-s24_28)

Verse 27

3 items (AT9713B-s31_33)

Verse 28

3 items (AT9713B-s34_36)

Comment:

FW: Identified mamupururnpa as a small lizard that people used to eat; it was mixed in with the seeds being cleaned.

Verse 29

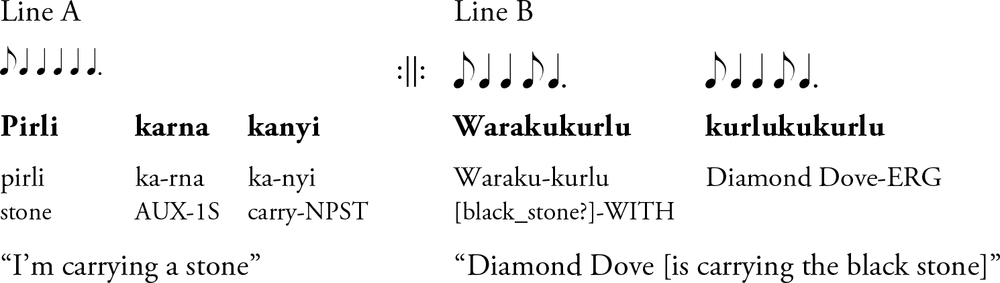

4 items (AT9713B-s42_45)

Comment:

ML: This is likely to be waraku-kurlu “black stone-WITH” from Kaytetye arake: “black stone used for making stone knives and axes; burnt wood used for painting ceremonial designs; soft black stone used for painting ceremonial designs” (Turpin 2012, 150–51). The ERG on kurlukuku “Diamond Dove” indicates that this is the name of the one carrying the black stone (also referred to more generally as pirli “stone” in the A line). Further adding to the complexity of interpretation, pirli is also used to refer to some seeds; and in this case, the use of waraku in Line B could further specify black seeds (like those in wakati in Verse 14). Note that the sound pattern kukurlu occurring at the end of both segments of Line B derives from different sources.

LB: Myfany Turpin (personal communication) advised that this verse also occurs in the Arrwek song set. Although not published in Yeoh and Turpin (2018), it can be seen in the 2009 film Mer Rrkwer Akert (Watts et al. 2009).

Verse 30

3 items (AT9713B-s48_50)

Verse 31A (slow version)

1 item (AT9618A-s14)

Comment:

ML: Based on discussion with Fanny Walker Napurrurla, unknown form waji-rirririrri (Line A) may have same meaning as wirri (Line B). This is where seed-bearing grasses grow best.

Text and interpretation are tentative, because we were unable to check the song in detail with FW in 2010.

Verse 31B (fast version)

2 items (AT9618A-s15_16)

Verse 32

3 items (AT9618A-s27_29)

Comment:

ML: Text and interpretation are tentative, because we were unable to check the song with Fanny Walker Napurrurla in 2010. Warlarrpirdipirdi has been analysed as a partially reduplicated form of the spoken form warlarrpirdi.

Verse 33

3 items (AT9618A-s30_32)

Comments:

FW: Jurtarnpi was the name of a Nakamarra woman, aunt of FW, who had passed away. It is the name of the Dreaming who is singing herself in this song.

ML: The name “Jurtarnpi” may be built on the verb tarnpi “follow tracks of”, as in Verse 17. The future form of this verb is tarnpi-ji.

Verse 34

3 items (AT9618A-s39_41)

Comments:

FW: The skink warrarna breaks up into pieces while cooking.

ML: In glossing, I have assumed that rirri-ja is a variant of the verb recorded as yurirri-ja “move” in spoken language. Warraparnu (eastern Warlpiri) and warrarna (western Warlpiri) refer to the same skink species (dialect variation).

Verse 35

3 items (AT9618A-s46_48)

Verse 36

4 items (AT9618A-s49_52)

Comments:

FW: Jangartpangartpa is the name of a bird, which is also the old man’s name. It lives in the Jipiranpa area.

ML: There may be an association with the place name Jangarlpangarlpa north of Jipiranpa.

Verse 37

2 items (AT9618A-s53_54)

Verse 38

1 item (AT9618A-s55)

Verse 39

4 items (AT9618B-s08_11)

Verse 40

4 items (AT9618B-s17_20)

Verse 41

2 items (AT9618B-s24_25)

Comments:

FW: The old Jakamarra man, Kalajirti, went back to Jipiranpa, his own Country, after he had chased and had illicit sex with his two mother-in-laws (two Nangala women).

LB: Note text line placement on melody is reversed in second item, to start with BB text line pair. Note the almost identical text Line A in Verse 18. In this case the rhythm is yanku “low”, and there is an extra syllable (-mpa ACROSS).

Verse 41 (variant)

Sung by FW in elicitation session, 2010.

Comments:

LB, ML: This text was offered by FW in 2010 (recording T100719a) when discussing Verse 41 as sung on the 1996 recording. Both lines of this version are based on Line B of Verse 41. The two lines are identical apart from the contrasting morphemes -rni “hither” and -rra “thither”.

Verse 42

3 items (AT9618B-s26_28)

Comments:

FW: The old man was spinning string from other people’s hair on his spindle.

ML: Kilmirr- is analysed as a preverb (of unknown meaning) because Warlpiri words must end in a vowel. This is also justified by the anacrusis on the first syllable of the verb luwarni.

LB: The rhythm is notated in 3/8. Note that in both lines the second element luwarni begins on an anacrusis (meaning the second syllable of luwarni bears musical stress).

Verse 43

3 items (AT9618B-s29_31)

Comment:

LB: Line B was quoted by FW as a comment on Verse 24.

Verse 44

3 items (AT9618B-s35_37)

Comment:

ML: Larrarna is analysed as vowel-initial “put” verb arrarna from an Arandic language source, with initial “l” prefixed to provide a consonant-initial word. In spoken Warlpiri, yirra-rni “put”, as in Verse 38, is also an Arandic borrowing.

Verse 44 (variant)

[Not on original recording; FW explanation and “correction” in 2010]

Comments:

FW: The women were down on their knees gathering up the Portulaca seeds.

LB: Compared to Verse 44, this version substitutes lurlupujupuju “kneeling” with the synonym murdujirrpijirrpi, based on the stem murdu “knee”, also pronounced mirdi.

Verse 45

4 items (AT9618B-s38_41)

Comment:

ML: Murdujirrpi in Line B, based on murdu “knee”, is a shorter form of murdujirrpijirrpi “kneeling”, which appears in Line B of Verse 44 variant. In spoken Warlpiri, the longer form murdujirrpijirrpi is more common.

Verse 45 (variant)

[Not on original recording; FW explanation and correction in 2010]

Comment:

LB: Compared to Verse 45, this version has a different Line A.

Verse 46

4 items (AT9618B-s42_45)

Comment:

ML: Warilyirrilyirri is the Warumungu name of a wren species. Seeds can be named after birds because of the shape of the seed or seed cluster, e.g. puntaru “little buttonquail”; “Quail’s Foot Grass seed”.

Verse 47

4 items (AT9618B-s46_49)

Comments:

FW: He was spinning hairstring near the fire.

ML: Alternative glossing for jarnangkarna: jarna-ngka-rna “shoulder-LOC-1S” is “I made/struck it on the shoulder”.

Nellie Nangala Wayne

Nangala was born in 1952 and grew up on Mount Doreen cattle station west of Yuendumu. When she was a young girl, she moved to Yuendumu, where she went to school. When she was a young woman, she married and had three children. Nangala has worked at the Yuendumu Old People’s Program and the Yuendumu Women’s Centre. She has also been an important member of the Yuendumu Women’s Night Patrol. Nangala has been central to recent projects to record and document women’s yawulyu, particularly in her involvement in the production of Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017), as well as public performance events. Nangala is an important ceremonial leader for the Southern Ngaliya women’s dance camps.

Ngajuju Nangala, ngapa jukurrpa, kuruwarri ngula karnalu yirrarni, yunparni, jukurrpaju ngapa. Yuwayi ngapa dreamingji. Milyapinyi karna jukurrpa kujakarnalu-jana yirrarni kurdu-kurduku every nganayi yangka school-rlangurla culture day ngula karnalu-jana ngapa jukurrpa yirrarni jukurrpaju and jirrnganja nguna karnalu-jana ngapangka-juku yuwayi.

I am Nangala, belonging to the Ngapa (Rain/Water) jukurrpa. We sing and paint the Ngapa Dreaming. I know the jukurrpa that we put on the kids at school when there is a culture day, and sometimes we go out and do the Ngapa ceremony with the kids.

Ngula karnalu follow mani song, ngaju-nyangu big sister-rluju learn manurra yuwayi right up. Ngapa yanu yatijarra, yinya kajana yatijarra karrimirra ngapa panukarikilki nyampu nganayi-ngirli nyampu kulkurru yangka my brother-kurlangu Jiwaranpa, far as there. Nganimpa-nyanguju ngulalpa nganimpa-nyangu big brother nyinaja yalumpurla Jiwaranparla outstationrla, yinyaju panukarikilki ka-jana karrimirra yatijarra ngula yanu yuwayi nyampuju ngapa yuwayi.

We follow the songs my big sister taught me, yeah. The Ngapa went up north, and the Ngapa jukurrpa on the northern side belongs to those people on that side, our Ngapa jukurrpa goes far as my big brother’s outstation called Jiwaranpa. The Ngapa jukurrpa on the northern side belongs to those people from that area.

Reference

Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Georgia Curran. 2017. Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu [including DVD]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Maisie Napurrurla Wayne

Napurrurla was born in Ti-Tree. When she was young, she came down to Yuendumu and grew up around Cockatoo Creek, to the north of Yuendumu. She is a kirda for the Ngurlu “edible seed” jukurrpa from near Mijilyparnta (Mission Creek) as well as Yumurrpa “white yam” in the Southern Ngaliya part of Warlpiri Country. She is a senior leader for yawulyu in Yuendumu and a leader for the biannual Southern Ngaliya dance camps through which she teaches this cultural knowledge to younger generations. Napurrurla has worked as a health worker at the Yuendumu clinic, as a childcare worker and at the Yuendumu Women’s Centre.

Yuwayi kurdu-warnu-patulku, yuwayi yangka pina-pina-mani-jala karnarlu-jana yuwayi.Yuwayi ngurrju kajikarlipa-jana pina-pina-mani yunparninjaku, yunparninjaku and nganayiki yangka yawulyuku kaji wirnti yinga mardarnirra nyanungurlulku yangka ngalipakariji. Ngajurlangu kajirna lawa-jarrimi yingalu kurdu-warnu-paturlulku mardarnirra nyanungurrarlulku, yuwayi. Pina-pina-jarrijarna ngulaju kamina-wiyi yangka kaminarnalu pina-pina-jarrija jaja-nyanurla, yapirliyi-nyanurla pina-pina-jarrijarna, yuwayi, and pimirdi-nyanurla. Yeah pina-pina-jarrijarnalu. Kurdu-warnu-wiyilparna lampunu-wangu-wiyi yangka lampunu turnturnpa kalarnalu nyinaja yuwayi.

Yes we are already teaching our younger generations. It’s really good for us to teach the young girls to sing and dance the yawulyu so they can keep it and carry on with it when they get older, and when I pass away they can keep it. I was taught by my grandmothers when I was just a young girl, and also my aunties taught me when I was a young girl.

Yangkalpajulu pina-pina-manu ngulaju yalilparna nganayi-pinki kuturu-pinki grab-manu and parraja wali ngulangkulpaju pimirdi-nyanurlu, yapirliyi-nyanurlu marda. “Manta ngula waja”, kalajulu kujarlu jiiny-ngarrurnu, “Manta waja and wirntinjayanta yalumpu-kurlu” yuwayi. “Parla-kurlu-ngurlulku manta waja yalumpu parrajalku manta waja! Jungarni wirntiya ngula-kurluju!” Yijardulparna wirntija, nganayi pimirdirlilpaju manu yapirliyirli, jajangku, especially yapirliyi-nyanurlu, pimirdi-nyanurlu. Yuwayi, wurlkumanu yalirli tardungku yuwayi. Yuwayi, ngampurrpa karna nyina yangka yingalu, karlipa-jana wangka purdangirli-warnu-watilki, “Nyuntulku waja yungunpa mardarnirra, ngampurrpa karnangku wangka waja yeah nyuntulku waja kajirna ngajurlangu nyurnurra jarrimi yungunpa nyunturlulku run- mani, kanyinpa nyampuju, kanyi nyunturlurlulku.” Yuwayi.

When I grabbed the coolamon or the dancing pole my grandmother and my auntie would say to me, they used to point to me and say “Get that thing for you to dance with!” That’s what they used to say to me. Then I would dance with my grandmothers and my aunties, that old lady Tardu taught me. Yes, I am interested so we can tell [the young people] “You keep this [knowledge] now so that you can be responsible when I pass away.”

Peggy Nampijinpa Martin

Nampijinpa is the daughter of Maudie Nungarrayi and Fuzzy Martin Jangala. Peggy is kirda for Pawu (including Warnajarra) and kurdungurlu for Patirlirri and the Ngatijirri jukurrpa complex. Peggy is a leader in women’s business in Willowra. Growing up and living in Willowra, she participated in yawulyu – women’s ceremonial business – as much as a mother of six could. She learned from the older women over the years. Since 2016, she has helped explain the meanings and ownership of the songs, along with Lucy Nampijinpa Martin and Helen Napurrurla Morton; Peggy has been key in the documentation of Warlpiri women’s yawulyu. In 2019, she provided a newly received yawulyu design for Warnajarra, thereby demonstrating continuity of tradition. Today she is one of two leading businesswomen in Willowra who knows the songs, designs and stories and sings loudly and clearly. She is a co-author of Morais et. al (in press 2024, Aboriginal Studies Press) Yawulyu: Art and song in Warlpiri women’s ceremony.

Reference

Morais, Megan, Lucy Nampijinpa Martin, Peggy Nampijinpa Martin, Helen Napurrurla Morton, Janet Nakamarra Long, Maisie Napaljarri Kitson, Maureen Nampijinpa O’Keefe, Clarrie Kemarr Long, Jeannie Nampijinpa Presley, Marjorie Nampijinpa Brown, Selina Napanangka Williams, Leah Nampijinpa Martin and Myfany Turpin. In press 2024. Yawulyu: Art and Song in Warlpiri Women’s Ceremony. Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Lucy Nampijinpa Martin

Lucy Nampijinpa Martin was born out bush near Willowra around 1930 to Ruth Nungarrayi and Fuzzy Martin Jangala. Lucy is kirda for Pawu (Mount Barkly), including Warnajarra. She is kurdungurlu for Patirlirri and Ngatijirri jukurrpa. Lucy grew up participating in yawulyu. She was an integral part of the women’s business documented in 1981–1982, and the Warnajarra series discussed in this book. She has been essential in the repatriation of materials to the community. It is via Lucy that the revitalisation of culture can take place. She is one of the leading businesswomen in Willowra today. As such, it is she who knows the songs and designs. She is a beacon of knowledge. In 2019, when playing songs previously recorded in 1981–1982, it was Lucy Nampijinpa Martin who would join in and sing loudly and clearly. Afterwards, she and Peggy Nampijinpa Martin would explain the songs. Younger women gathered around to listen and to learn. Lucy’s work features throughout Chapter 7 – it includes the songs she sang in 1981–1982 and has sung since for further recording purposes.

1 In previous publications, the place name “Jipiranpa” has also been transcribed as “Jiparanpa”.

2 Edited summary by Mary Laughren from her interview in Warlpiri with Fanny Walker Napurrurla and Jessie Simpson Napangardi (T100718a-03.wav). This recording was made by Myfany Turpin, and fieldwork was funded by the Australian Research Council Linkage project LP0989243. See Chapter Appendix for details of these comments.

3 Written statement created with Gretel Macdonald, 15 October 2021.

4 See Chapter Appendix for further details and summary of these Barwick-Turpin recordings T100718a, T100719a.

5 Japaljarri and his close friend Joe Bird Jangala led the men’s singing and decided what was to be recorded and who else needed to be included in the performance group. Men’s singing sessions recorded under the direction of Japaljarri and Jangala included several different Dreamings, including Yilpinji Ngapa (Rain/Water Dreaming), Yilpinji Malikijarra (Two Dogs Dreaming) and Yilpinji Ngurlu (Edible Seed Dreaming).

6 The name “Warrabri” was a portmanteau based on Warramungu (Warumungu) and Warlbri (Warlpiri), the home languages of many of the people moved to the settlement, although the settlement itself was on Kaytetye Country.

7 See Peterson and Long (1986) for explanation of Warlpiri kinship and land tenure systems.

8 Maggie Green Nampijinpa was also present for Performances 3 and 4; Suzie Newcastle Nampijinpa was also present for Performance 4.

9 For example, in Performance 1, Verse 7 recurs three times, as song items 18–20 and 44–45 on tape AT97/13A and song items 22–23 on tape AT97/13B, and also in Performance 1 as song items 11–13 on tape AT96/18A (archived with AIATSIS Collection BARWICK_L01).

10 For discussion of song ordering in various Australian song traditions, see Ellis (1970), Moyle (1979) and Treloyn (2007).

11 The personal name “Yimarimari” is discussed further below.

12 Discussion with Mary Laughren and Linda Barwick, recorded by Myfany Turpin in July 2010. Translation by Mary Laughren.

13 Note that many of these actions are repetitive and rhythmic in nature, as are songs and their associated dances that enact these ancestral actions.

14 For all examples, see Appendix 6.1 for breakdown of words and possible translations.

15 The Warlpiri language of the verses contains many forms that are characteristic of the eastern dialect, Wakirti Warlpiri (Simpson and Nash 1990).

16 See Curran (2019), Morton (2011), Peterson (1970), Vaarzon-Morel et al. (Chapter 8, this volume) for discussions of the cultural significance of fire in relation to marriage exchange.

17 See many works of Turpin and her collaborators, including San and Turpin (2021), Turpin (2007a, 2007b), Turpin and Laughren (2013) and Yeoh and Turpin (2018).

18 The placement of the rhythmic text on the melody is decided in performance, and often varies between consecutive items. See Barwick (2023, 1989) for examples and discussion of the principles of text-melody alignment in the Central Australian musical system.

19 For the purposes of this musical analysis, the sample size is 48, counting the fast and slow versions of Verse 31 as different rhythmic text combinations.

20 Correspondingly, short notes typically mark the beginning of a structural unit.

21 For discussion of Australian examples, see among others, Barwick, Birch and Evans (2007), Dixon (1980), Donaldson (1979), Koch and Turpin (2008), Garde (2006), Hale (1984), Turpin and Stebbins (2010), Walsh (2007) and Wild (1984).

22 Personal communication to Gretel Macdonald, 2021.

23 Edited summary of interview by Mary Laughren [T100718a-03.wav] in AIATSIS collection BARWICK_J01. Warlpiri text of relevant section: ML: Manu kamina-kamina? FW: Yuwayi. Yirntija-gain kalalu. Yeah. Yirntija kalalu. ML: Pina-pina-manulu-jana yawulyuku yunparninjaku? FW: Lawa. Yawulyu-mipalpalu-jana kujurnu. […] ML: Nuu kalu yunparni young-people-rlu? FW: Walku. ML: Wirntimi kalu? FW: Yirntimi kalu. Jessie: Kamina-kaminalu wirntija. ML: Kuruwarri-kirli. FW: Kuruwarri kujurnu-rnalu-jana.

24 Jessie Simpson Napangardi, personal communication to Gretel Macdonald, 15 October 2021.

25 Written statement created by Jessie Simpson Napangardi and Sarah Holmes Napangardi with Gretel Macdonald (15 October 2021).

26 See List of Contributors for further details on Enid Nangala Gallagher and profile for Alice Nampijinpa Henwood this volume.

27 In this summary of the verses, we have opted for standard Warlpiri rather than phonetic text as sung because the latter may include vowel alterations that tend to be inconsistent from one rendition of the text line to the next, and that may also vary between individual singers in group performance.