7

Warnajarra: Innovation and continuity in design and lyrics in a Warlpiri women’s song set

This chapter describes a Warlpiri women’s yawulyu song set referred to as Warnajarra. The interdependence of design and dance with song warrants some discussion of all three components; however, we focus predominantly on the song texts. These texts make great use of repetition and words from neighbouring languages. Warnajarra is from Pawu, an area south of Willowra community in Central Australia on the Eastern edge of Warlpiri Country (Vaarzon-Morel 1995; Wafer and Wafer 1980). To the east are Anmatyerr and Kaytetye people, whose closely related languages are of the Arandic subgroup – quite different from the Ngumpin-Yapa subgroup to which Warlpiri belongs.

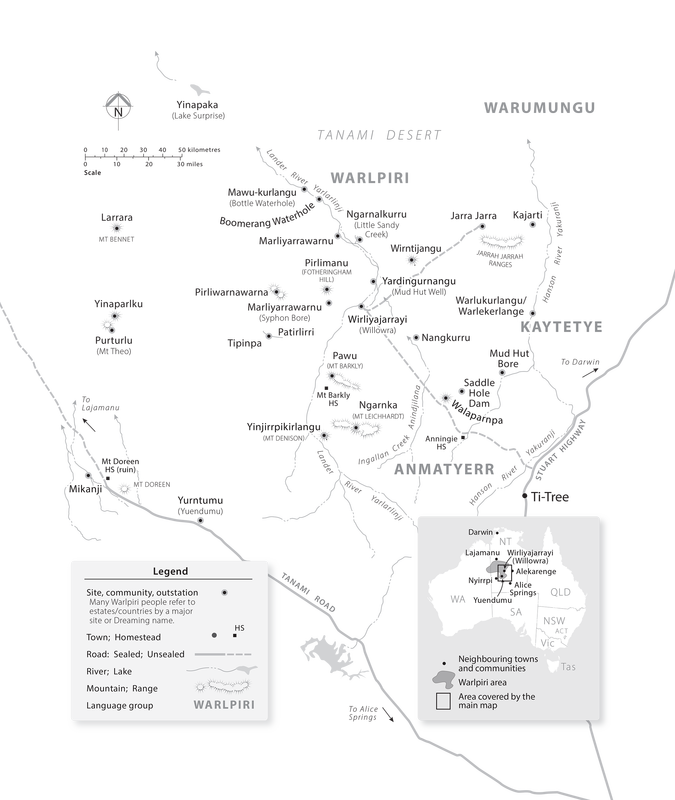

Pawu is often translated as “Mount Barkly”, the English name for a prominent hill and outstation on the Pawu homelands (see Figure 7.1). The patrilineal owners or kirda for the north-east side of Pawu, including its jukurrpa and songs, belong to the Jangala/Nangala and Jampijinpa/Nampijinpa subsections or “skins” (hereafter referred to as J/Nangala and J/Nampijinpa). Warnajarra “Two Snakes” is a major jukurrpa associated with Pawu and the J/Nangala and J/Nampijinpa subsections, and the snakes are said to be of Jangala skin.1 The Warnajarra travel north to Jarrajarra, an area whose patrilineal owners belong to the J/Nungarrayi and J/Napaljarri subsections and that is also associated with the neighbouring Arandic language Kaytetye. These subsections, along with the J/Napangardi and J/Napanangka, are in the opposite patrimoiety to J/Nangala and J/Nampijinpa, who marry into them. Jukurrpa associated with Jarrajarra include Jurlarda “Sugar Bag”, and several of the Warnajarra songs relate to Jurlarda jukurrpa and the ancestral Moon Man jukurrpa.

Figure 7.1 Map of the Warlpiri region (Morais et al 2024). Warnajarra yawulyu, the subject of this chapter, relates to Pawu (Mount Barkly), in the centre of the map.

It is not clear to which type of snakes Warnajarra refers. It may be that the referent of Warnajarra is intentionally vague; however, when asked, Nampijinpa described the snakes as “two little ones, quiet ones, grey ones”,2 which suggests they may be of the species Lialis burtonis, Burton’s legless lizard. While referred to as warna “snakes”, these two ancestors are, at some level, also human beings. In addition to the Warnajarra songs described in this chapter, Pawu also has yawulyu that celebrate a number of other ancestors, some of which are described in Turpin and Laughren (2013, 2014), Curran (2019) and Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu (2017).

The Warnajarra “Two Snakes” yawulyu described in this chapter was recorded by Megan Morais (nee Dail-Jones) in 1981 and 1982 as part of her research on Warlpiri women’s ceremonial dance (Dail-Jones [Morais] 1984, 1998).3 The singers also explained the meanings and words of the songs, which were translated at the time by Janet Nakamarra Long (Morais 1981–1982). Since then, yawulyu performance has declined at Willowra, as in other Warlpiri communities. The authors of this chapter subsequently worked with Willowra women in 2016–2019 to gain further understanding of the songs as part of a larger song documentation project.4 This created opportunities for younger women to hear and practise the songs, as well as learn their significance from Elders. An outcome of the project is a book of the 1981–1982 yawulyu (Morais et al., in press).

This chapter assembles work from these two fieldwork periods, almost 40 years apart, to draw attention to aspects of yawulyu where there is creativity, an indicator of vitality, such as that found in body designs, and where it is absent, as is the case in the songs – suggesting that this reflects the degree of exposure to and practice of visual arts versus ceremonial singing, respectively. The chapter argues that the poetic structure of songs is founded on knowledge of neighbouring languages and complex patterns of poetic reduplication; that is, patterns of syllable reduplication not found in speech. We put forward that the absence of new songs and the decline in the number of singers reflect a lack of familiarity with these structures.

We first discuss the corpus of recordings and then creativity in yawulyu designs. We then discuss the relationship between the meaning of verses and visual aspects (dance and design) and issues in identifying words and their meanings. We then discuss aspects of meter and focus on two salient features of Warnajarra song texts: the intermingling of neighbouring Arandic language vocabulary with Warlpiri and poetic reduplication. While both features are present in other Central Australian yawulyu (Koch and Turpin 2008), they are particularly prevalent in the Warnajarra verses.

The recordings

The analysis presented in this chapter draws on the two periods of fieldwork mentioned above: 1981–1982 and 2016–2019. A brief description of these events follows. Recordings of Warnajarra, on which the analysis presented here is based, are summarised in Tables 7.1 and 7.2 and described below.

Table 7.1 The 1981/1982 recordings by Megan Morais.

| Date | Recording name | Number of song items and verses |

|---|---|---|

| 28, 29 May 1981 | DJ_M01-019516–8 | 119 song items, 30 verses |

| 23 April 1982 | DJ_M02-021717 copy of P. Wafer’s recording |

37 song items, 9 verses |

Table 7.2 The 2016–2019 recordings in which Warnajarra was performed or translated.

| Date and recorders | Location | Content | Number of song items and verses |

| 30 June 2016 (Laughren and Turpin) |

Willowra | Discussion of songs on DJ_M01-019517 followed by a performance of Warnajarra: Peggy Nampijinpa, Lucy Nampjinpa, Leah Nampijinpa and Marilyn Nampjinpa | 48 song items, 22 verses |

| 16 August 2019 (Turpin and Morton) |

Alice Springs | Discussion of songs on DJ_M01-019517 and M01-019518 with Peggy Nampijinpa and Helen Morton | |

| 25 Nov 2019 (Turpin and Morais) |

Willowra | Discussion of songs from Pawu with Peggy Nampijinpa, Lucy Nampijinpa, Marilyn Nampijinpa and Marjorie Brown Nampijinpa |

The recording name refers to the archive number at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS).

In 1981, Warnajarra was performed during a yawulyu session of singing and painting up for Pawu (Mount Barkly). The main singers were Millie Nangala Kitson, Topsy Nangala, Molly Nungarrayi Martin, Ruby Nampijinpa Forrest, Mitipu Nampijinpa and Lady Napaljarri Morton, with many other women participating. The next day, Warnajarra was performed again, but with dancing following the painting up, and singing accompanying both these activities. This was a typical ceremonial procedure: painting up one day, followed by painting up and then dancing the next (or two days later). There is no doubt that the first yawulyu session strengthened the subsequent session.

Another recording of Warnajarra was made on 23 April 1982. This was in preparation for the Mount Barkly Land Claim. The performance was at Mount Barkly Station just after a hunting trip. Both Megan Morais and anthropologist Petronella Wafer (Vaarzon-Morel) were there, and the archived recording is a copy of P. Wafer’s recording. This did not include painting up (consequently, kirda, the patrilineal ceremonial owners, were not instilled with the power of the ancestors and did not become the embodiment of Warnajarra), but there was spontaneous dancing during the singing, which Morais documented in Benesh Movement Notation (Dail-Jones [Morais] 1984, 1992).5 A third performance of Warnajarra was held three days later, on 26 April 1982, with painting up and dancing at Pawu. Unfortunately, the recordings are of poor quality due to windy conditions; therefore, they could not be analysed. However, drawings of the ceremonial designs were made, and notes on songs were written down as the women painted up (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Women’s Warnajarra body design that represents Majardi (hairstring waistbelt, see Figure 7.4), 26 April 1982. Drawing by Megan Morais.

In 2013, Myfany visited Megan in California. Following from this, a request for Megan’s collection (audio, drawings, notes, photos) was made to AIATSIS for Myfany to bring to Willowra. In 2016, Mary and Myfany worked with Willowra women to transcribe and translate the songs on these recordings, which often resulted in further singing; in 2019, Megan also came to Willowra. Only the sessions relating to Warnajarra are listed below.

Relationship between design, dance and song text

Body painting and dance are integral to a full yawulyu performance. Both only occur with song and can provide further information or alternate understandings of the accompanying song. A brief look at body painting gives insight into the vitality and change that is currently taking place in yawulyu in Willowra.

Figure 7.2 is a copy of a body painting design that the Warlpiri women painted frequently during yawulyu in 1981–1982. This accompanied multiple song sets, including Majardi (hairstring waistbelt) that women use in Pawu dances. As Munn (1973, 146) stated, Warlpiri people perceive designs and songs as a single complex and treat them as “complementary channels of communication about an ancestor”. A design is sung on. The women doing the painting up must sing. Painting up and singing activate the kuruwarri (power) of the jukurrpa. The designs, songs and dance movements are comparable in that the different components of each can be perceived to be multifaceted, with many levels of interpretation (Morais et al., in press). This creates a potential avenue for changing associations or meanings.

While Myfany and Megan were going over Pawu designs and archived recordings in 2019, Lucy Nampijinpa Martin and Peggy Nampijinpa Martin sang one of the Warnajarra verses. At the end of the singing, Peggy said she had a new design. It came to her while singing the verse in Figure 7.3 (Verse 33).6 She had Selina Napanangka Williams draw the design as she explained it. Peggy said it was Majardi from Pawu. She included a drawing of a Majardi (hairstring waistbelt) she intended to make (see Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.3 The Warnajarra verse from 1982 (Verse 33, DJ_M02-021714, song items 1–3) that inspired Peggy’s new design, which was drawn after Peggy sang this verse on 25 November 2019 (audio recording 20191125_6).

Peggy’s new design (Figure 7.4) is significantly different to the 400 designs copied during yawulyu performances in 1981–1982. Differences in the design style include the break-up of the yoke, which predominantly had 1–3 lines painted under the neck going from shoulder to shoulder (see Figure 7.2). In the 2019 design, Peggy had created the yoke lines with small red, white and yellow squares. In effect, these squares create, as well as break up, the yoke lines. Significantly, the Warlpiri hand sign for yawulyu replicates the lines across the yoke, moving without pause from one shoulder to the other. In other words, in the past, the unbroken yoke represented yawulyu. Thus, now we have an altogether different rendition of yawulyu designs.

In addition to a change in the format of the yoke, Peggy’s 2019 design on the arms has changed in that it replicates the design on the yoke – multiple times over. This differs from the 1980s designs, where the arm designs usually replicated those on the breasts rather than the yoke. Figure 7.5 shows how arm designs replicated breast designs in 1981. Additionally, in the past, women painted circles and dots rather than small squares. Interestingly, Peggy’s breast elements are somewhat reminiscent of a 1981 Warnajarra body design from Pawu, demonstrating some continuity within her innovation.

Peggy’s 2019 design (see Figure 7.4) is indicative of changes that are occurring in yawulyu designs today: a new design inspired by a Warnajarra song sung 40 years ago and still being sung in 2019.7

Figure 7.4 The 2019 yawulyu design created by Peggy Nampijinpa Martin after singing the Warnajarra verse in Figure 7.3 (Verse 33). Penned by Selina Napanangka Williams. Underneath is the Majardi (hairstring belt) penned by Peggy. Both were later redrawn by Megan Morais and are presented here.

Figure 7.5 Warnajarra yawulyu body design from Pawu. Representation on paper by Megan Morais, 1981.

Designs, songs and dance movements are comparable in that the different components of each can be perceived to be multifaceted, with many levels of interpretation. Just as body designs provide multi-symbolic information, dance typically includes gestures and the use of highly symbolic props. The dance gestures can relate to the meaning of the text, or dance may add something extra about the text. Here we provide one example of each and refer readers to Dail-Jones [Morais] (1984, 1992, 1998) for further information about Warlpiri dance.

Dance related to the meaning of the text

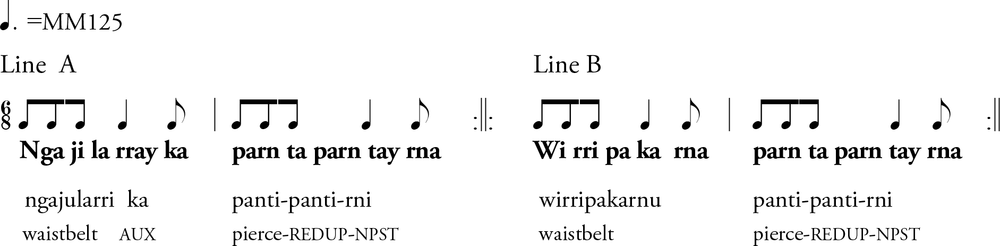

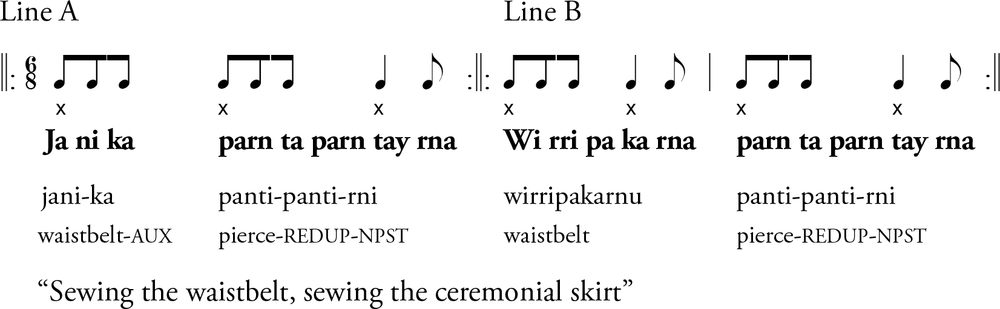

As in many yawulyu, dance is often a symbolic representation of the meaning of the verse it accompanies. In the early 1980s, Willowra women did not allow video recording or still photography, so Megan notated the dance using Benesh movement notation. Thus, Megan’s descriptions of the dance are based on both analysis through transcription, as well as field notes from the time. Consider the verse described in Figure 7.7 (Verse 13) and its accompanying dance described below. The senior women explained that ancestral women sang this verse while mending the traditional Majardi (hairstring waist belt) they were wearing.8 (A detailed discussion of the words in this verse and their meanings is provided following Figure 7.7.)

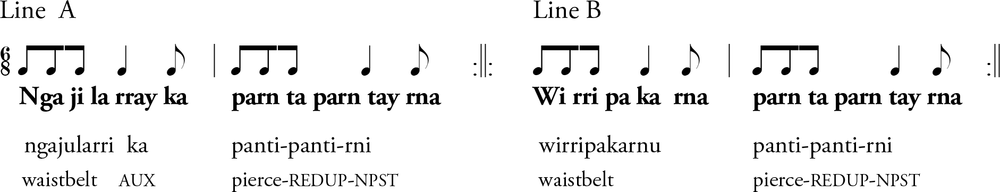

The accompanying dance movement involved hands near one’s lap, palms facing in towards the stomach and forefingers touching, fingertips pointing down, and doing a slight patting action of 3–5 beats (down on the main beat) as the hands move to the left of the body while the upper torso and head turn to the left, following the action of the hands. The action was repeated alternately to the right side and the left. One person threw dirt over her back during these movements (the Benesh notation of this dance can be seen in Appendix 7.2). The movements in this dance relate to both the meaning and the rhythm of the verse. The rhythm of the verse is made up of a 5-syllable/note pattern (rtyqe) that repeats four times (Figure 7.3, Verse 13). This vocal rhythm may correspond to the “slight patting action of 3–5 beats”. The body painting worn by the performers is also said to represent the word in the text, Majardi (hairstring waist belt) (see Figure 7.2).

Dance not directly related to the literal meaning of the song text

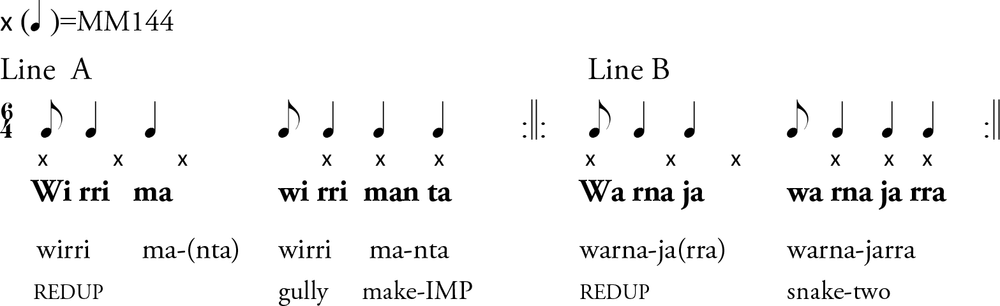

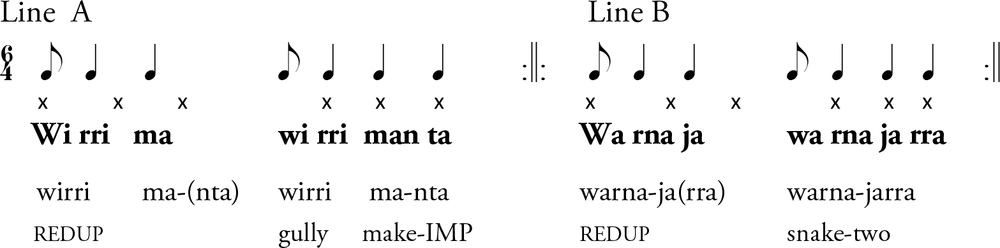

The dance can also be a symbolic representation of actions or objects that are not mentioned in the text. For example, the dance accompanying the verse in Figure 7.6 (Verse 6) involves turning the torso and the head to the right, and down, and then to the left and down, ad lib. This symbolises how the snakes were looking around as they were hunting. Literally, the verse text is “Make a gully, you two snakes!” The song evokes a small gully or water channel at Pawu, where water flows from a spring. The Two Snakes got to this site where they made this gully for the water to run through. The dance action symbolises the looking-around action by the Two Snakes, an action not overtly referred to in the verse.

Figure 7.6 A verse of Warnajarra where the dance represents the Two Snakes ancestors looking around (Verse 6).

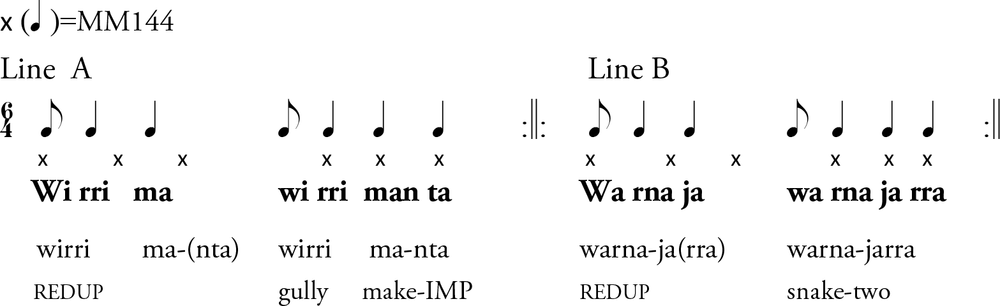

Like most Warnajarra verses, the verse in Figure 7.6 shows reduplication. The sequences wirrima wirrimanta in Line A and warnaja warnajarra in Line B are both examples of reduplication. In both cases, the reduplication is partial rather than full – as the full words are wirri-manta and warna-jarra. Partial reduplication can copy from either the beginning of a word (left edge) or from the end of a word (right edge). In this verse, both reduplications copy from the left edge of the word, omitting the final syllable: wirrima(nta), warnaja(rra). Both leftwards and rightwards reduplication is present in Warnajarra. Finally, the entire line is a reduplication – there is no unaccounted-for text in either line. Here, we can say that reduplication is a method of line formation. The remainder of this chapter outlines the many different patterns of reduplication: partial and whole reduplication, from the left edge or right edge, and even more complex patterns. The discussion thus far has assumed that identifying the underlying words is uncontroversial; however, this is rarely the case in song.

Issues regarding identifying words in songs

It can be difficult to identify words in Aboriginal songs, as many researchers have observed (Brown et al. 2017; Clunies Ross, Donaldson and Wild 1987; Koch and Turpin 2008; see also Vaarzon-Morel et al., Chapter 8, this volume). Varying degrees of certainty about a speech equivalent have led researchers to talk about songs ranging from complete transparency (where the words are unanimously agreed upon) to opacity, where speakers may not know the speech equivalent (Walsh 2007). Opacity can be due to sound changes imposed on words or because foreign, archaic or special poetic words (“spirit language”) are used (Brown et al. 2017). The task is even more challenging because songs are often highly elliptical and enjoy multiple possible interpretations. Vagueness and ambiguity seem to be highly prized, possibly to maximise the relevance of a verse in multiple contexts.

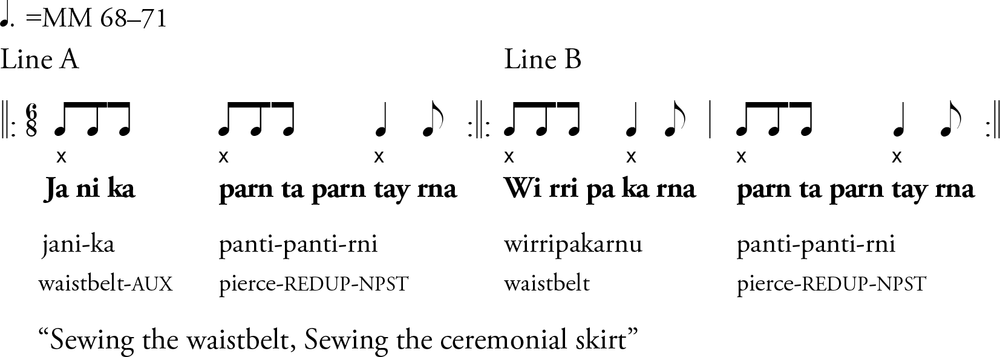

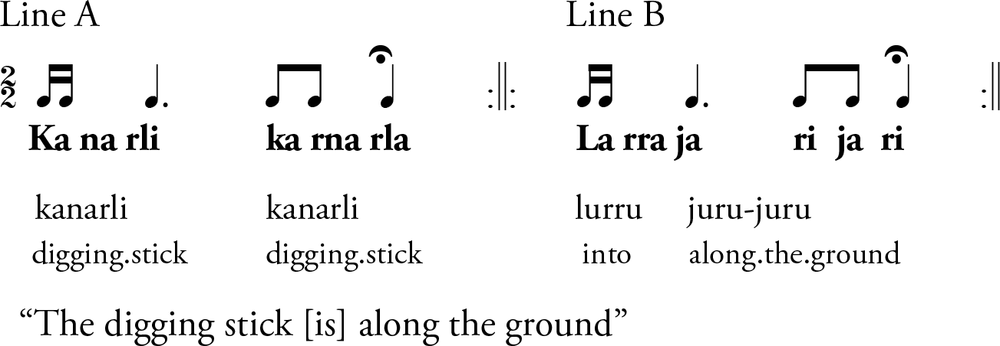

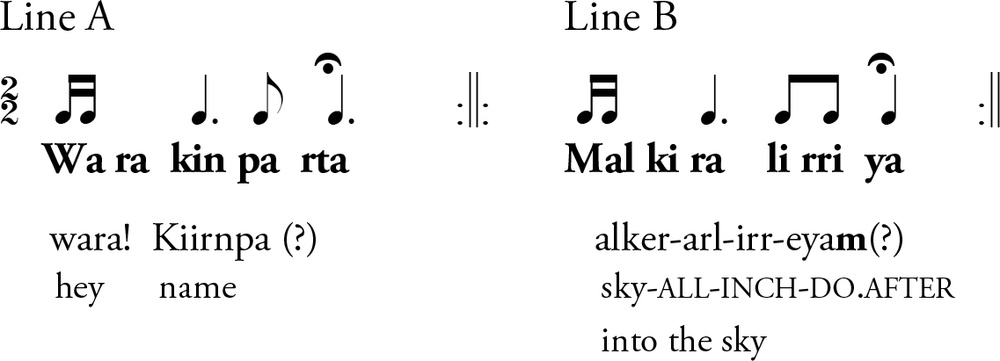

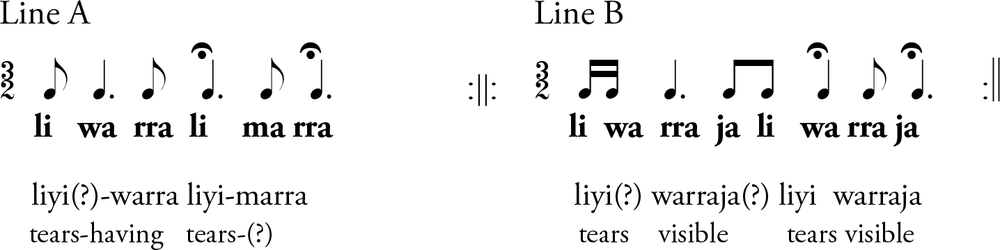

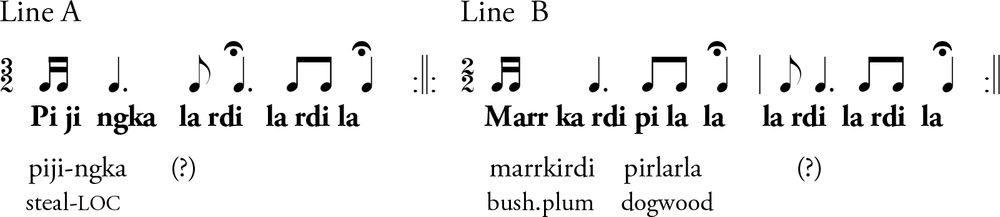

Even the most transparent song texts can have a degree of ambiguity. By way of illustration, consider the Warnajarra verse in Figure 7.7 (Verse 13). Note that the final hemistich (half-line) is identical in both lines, as is common in yawulyu.

Figure 7.7 Ambiguity in the words of a Warnajarra verse (Verse 13).

There are three possible speech equivalents for the final hemistich in each line. It could be panti-panti-rni “sewing” or the past form pantu-pantu-rnu “sewed”, or parnta-parnta “covering”, followed by either -rna “I” or rna, a common song vocable (with no known meaning) occurring at the end of a bar as an upbeat (Turpin and Laughren 2013).9 It is the presence of the auxiliary ka in Line A that determines the correct interpretation shown as “a)”. In addition, there are two possible referents of the song: a group of ancestral women or the two ancestral Jangala Snake Men, who were later described as sewing string on their belt to make a hairstring waist belt.10

This verse also illustrates two further points about how yawulyu verses are formed. First, notice the recurrence of wirri in this verse and the previously considered verse (Figures 7.6 and 7.7), in seemingly semantically unrelated words: wirri “gully” and wirripakarnu “hairstring belt”, also present in the everyday Warlpiri word wirriji “hairstring”. The use of wirri may serve to unite the images to which these songs relate. Repetition of syllables may thus become associated with particular meanings.

Second, the verse is made of two nearly identical lines. Their rhythm is the same, and the text in the second hemistich is the same; further, while the words in the first hemistiches differ (ngajularri, wirripakarnu), their meaning “waistbelt” is the same. Such parallelism between lines is a common way of forming a yawulyu verse. Such methods of line formation are particularly prevalent in Warnajarra and are the focus of this chapter.

Vocabulary from neighbouring languages

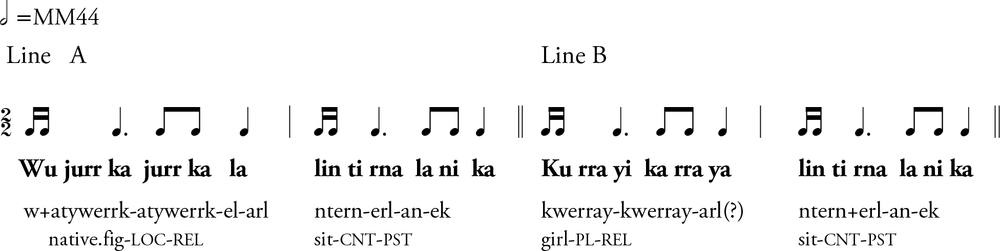

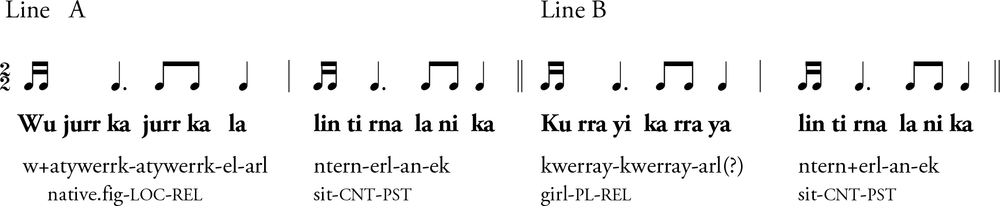

A striking feature of the Warnajarra song texts is the large number of words from neighbouring Arandic languages and a small number likely from Warumungu, spoken further north. Pawu is close to the eastern extremity of Warlpiri Country, and there is a long history of people from this area interacting with Anmatyerr- and Kaytetye-speaking people to the east (Vaarzon-Morel 1995; Wafer and Wafer 1980). In the 1980s, many older yawulyu performers at Willowra spoke or understood either or both Anmatyerr and Kaytetye, as well as Warlpiri.11 Arandic languages and Warlpiri have different sound systems. One of the main differences is that Warlpiri words start with a consonant and end in a vowel and have stress on their first syllable, while Arandic words mostly start with a vowel and have stress on their second (i.e., first post-consonantal) syllable (Breen 2001). Arandic words are woven into poetic lines altered to adhere to the Warlpiri sound system. This usually involves adding a consonant to the beginning of a word and turning central vowels into a high vowel, “i” or rounded “u” and changing the quality of the final vowel (not written in Anmatyerr orthography), which is typically “a” when sung although a high vowel in Warlpiri speech. For example, consider the final word of Lines A and B in Figure 7.8 (Verse 18). This is likely an Anmatyerr verb meaning “sitting around”, internerl-anek, which becomes l + intirnirl-aniki in song. It can be seen that the added consonant “l” is actually the final consonant of the relativiser -arl from the end of the previous word, transferred to the beginning of the next word internerl-anek. The “e” is altered throughout to “i” when borrowed into Warlpiri.12 Note that the line-final vowel is “a”, not “i”, which is a common line-final vowel in yawulyu, especially in Arandic. In Line B, the speech equivalent could be Kurraya, as pointed out by a reviewer, an important place that features in Warumungu yawulyu, or Arandic kwerray “girl-VOC”. Lexical ambiguity arising from Arandic, Warumungu and Warlpiri words as possible speech equivalents is one source of ambiguity in song meaning.13

Figure 7.8 A Warnajarra verse with speech equivalents from neighbouring language varieties, here showing Arandic words on which the song text is likely based (Verse 18).14

Most Arandic words begin with a vowel, but Warlpiri words must begin with a consonant – hence the insertion of “w” before “atywerrk” in Line A in Figure 7.8. Typically, the consonants “w” or “y” are added to the beginning of Arandic words borrowed into Warlpiri. For example, wijirrki is the Warlpiri, and Warumungu, word for the native fig (Ficus brachypoda). In yawulyu also, additional consonants are inserted word-initially, including nasal consonants “m” and the lateral “l”, which have their origin in the Arandic song practice of transferring the final consonant of a monosyllabic suffix to the beginning of a word (as on the verb in Figure 7.8). In Arandic yawulyu, when there is no available final consonant to be transferred, a glide is inserted line-initially, as in Line A in Figure 7.8, or the initial vowel is dropped (Turpin 2005, 193, 2007). The retention of rounding on the vowel following “j” in wujurrka (Figure 7.8) mirrors the Arandic spoken form of atywerrk.

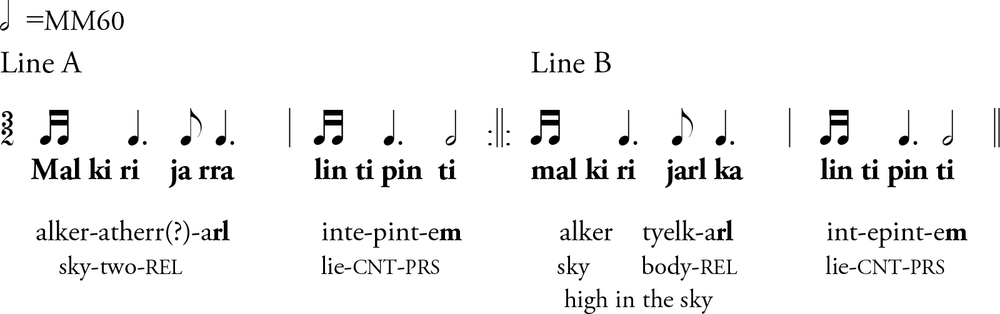

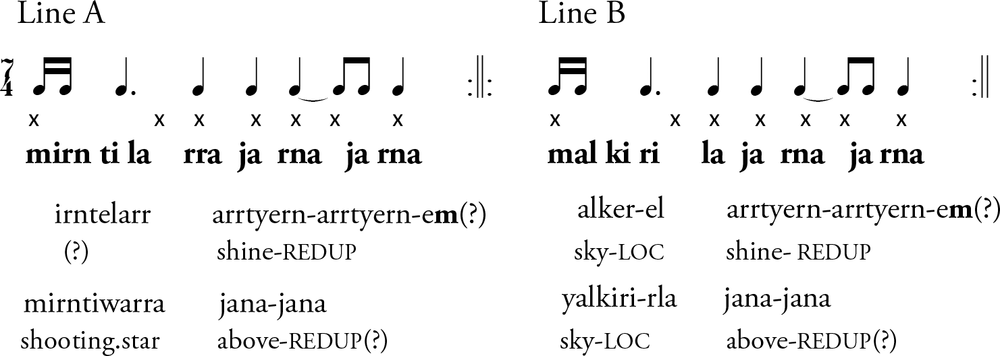

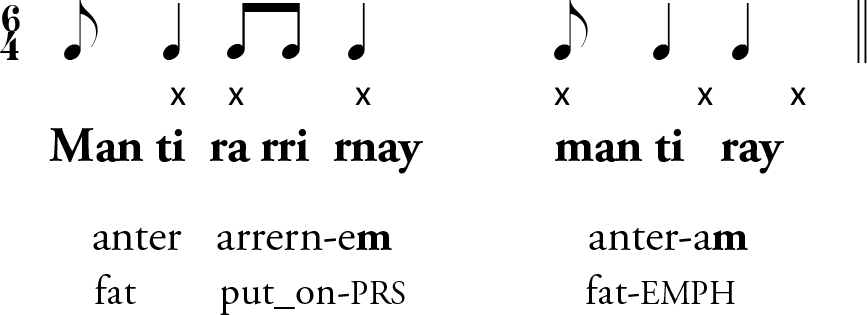

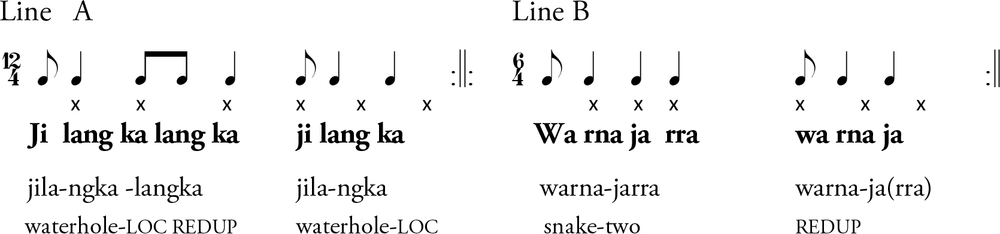

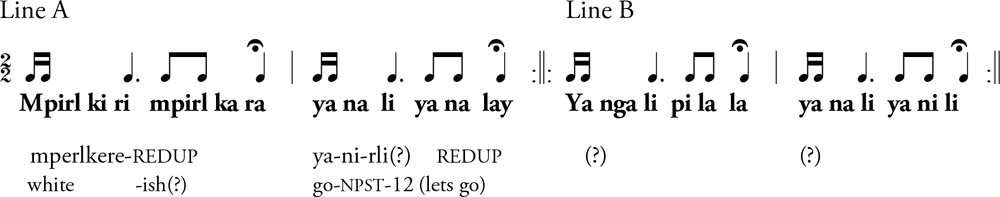

Some Arandic words have been incorporated into Warlpiri and have a set form, such as yalkiri “sky”; however, in song, we find that there can be a different consonant at the beginning of the word. For example, “sky” is sung with an initial “m” not “y” in the verse in Figure 7.9 (Verse 30). This is the result of transferring the final consonant of the Arandic verbal inflection -em (non-past), “m” to the beginning of the line. Note that while the speech equivalents in the middle of the line are not known, it is possible they end with either the locative (-el) or relativiser (-arl), and that this is the source of the “l” at the beginning of the Anmatyerr verb. This is the same resyllabification seen in Figure 7.8, a process that also occurs in connected speech.15 In contrast, the line-initial consonant “m” is transferred from the previous line-final suffix, a process documented in Hale (1984, 260) and Turpin (2005, 236) in other Warlpiri and Arandic songs respectively. The line, as a poetic structure, is not a feature of speech; thus, line-final consonant transfer is unique to central Australian singing traditions. Notice too that the transfer of final consonants in Figures 7.8 and 7.9 is limited to monosyllabic root-level suffixes: a constraint also found in other Arandic–Warlpiri songs (Hale 1984; San and Turpin 2021).

Figure 7.9 A Warnajarra verse with Arandic vocabulary and final consonant “l” transferred to the beginning of the next word and “m” to the beginning of the next line (Verse 30).

Variability in the initial consonant of the word is a further telltale sign that these are not everyday Warlpiri words but purely song forms. For example, the verse in Figure 7.7 has the word ngajularri “waistbelt”, but this is sometimes sung as majularri, varying the initial consonant.16

Meter

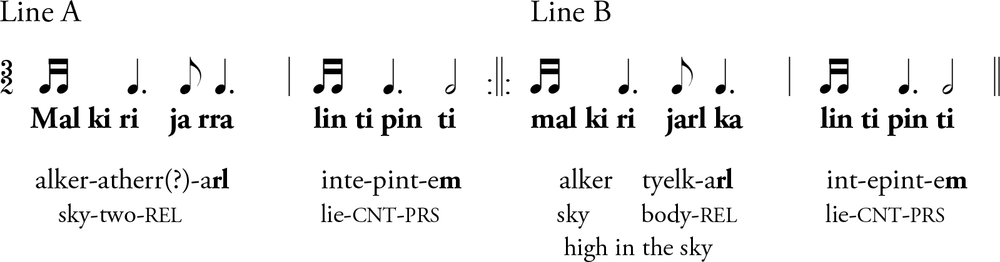

Most of the 28 Warnajarra verses fall into one of two broad meters: a slow meter and a fast syncopated meter. Contrasting meters within a song set are also found in other Warlpiri yawulyu (Turpin and Laughren 2013, 2014), as well as in neighbouring Kaytetye (Turpin 2005). Only one Warnajarra verse has a meter other than these two fast and slow meters. This is the verse considered in Figure 7.7 (Verse 13). It has a compound triple meter, a meter frequently used in Ngatijirri “Budgerigar” yawulyu (Turpin and Laughren 2013). The Warnajarra and Ngatijirri jukurrpa tracks intersect, and it may be that this triple meter verse in the context of a Warnajarra performance alludes to the Ngatijirri jukurrpa associated with Wirliyajarrayi (Willowra) where the performers were living.

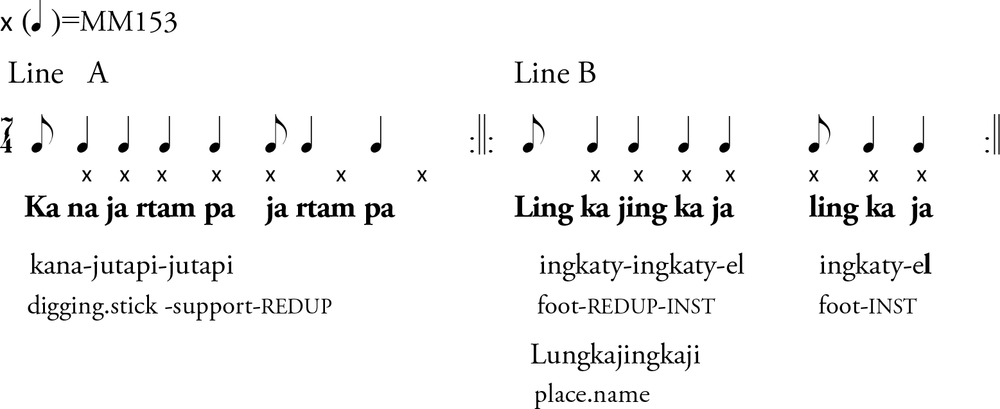

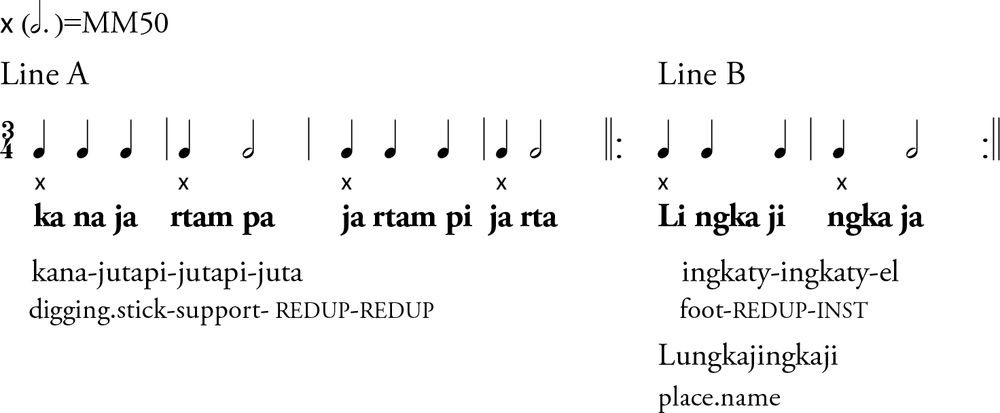

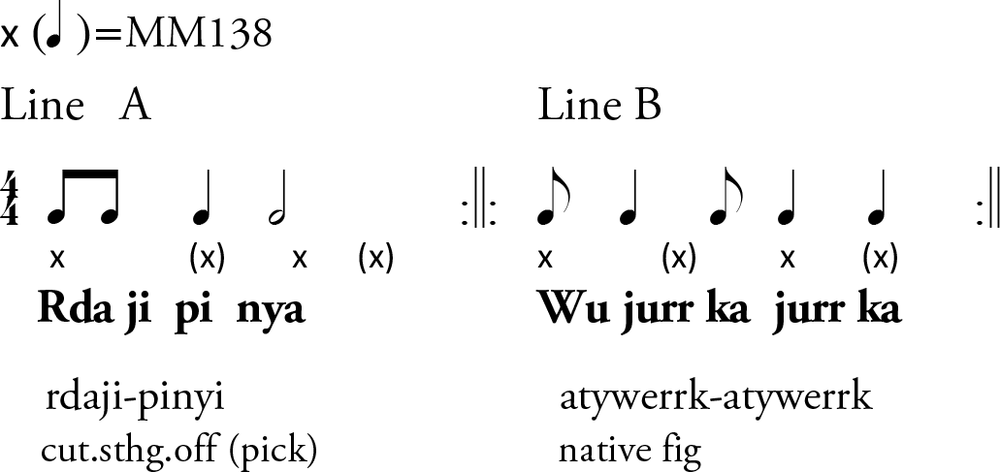

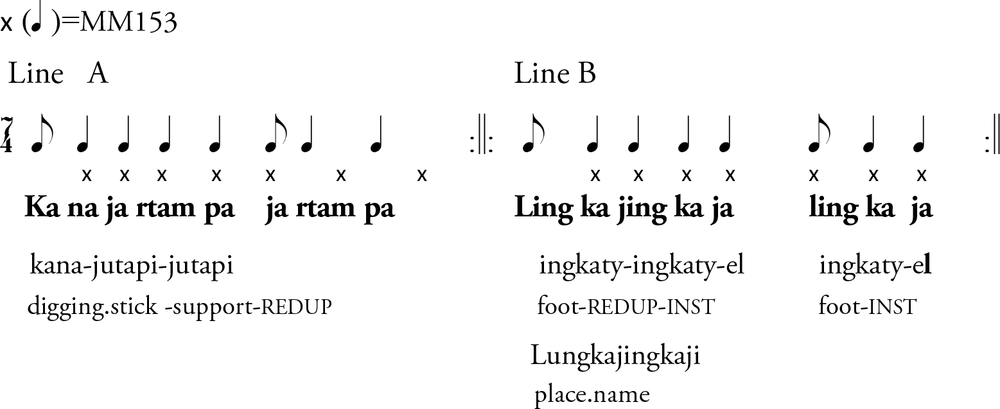

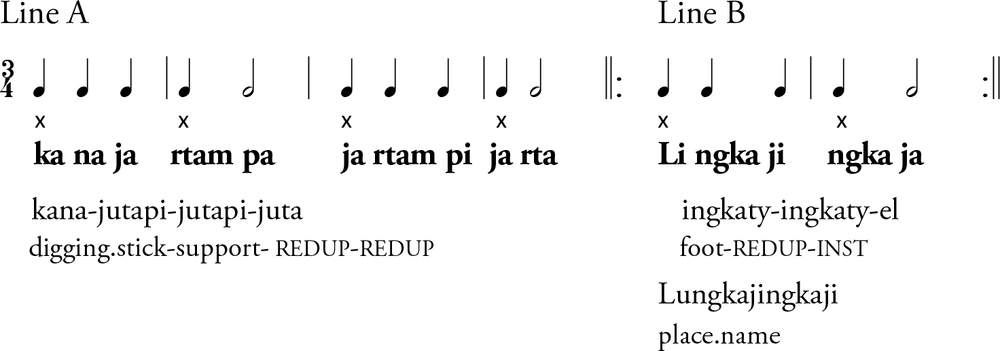

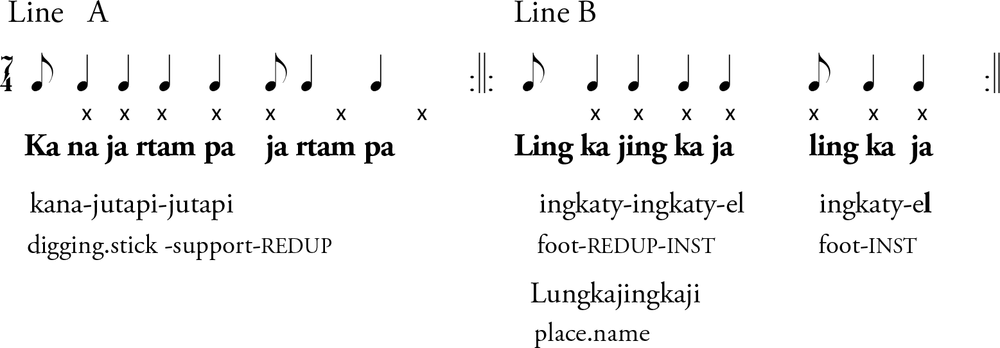

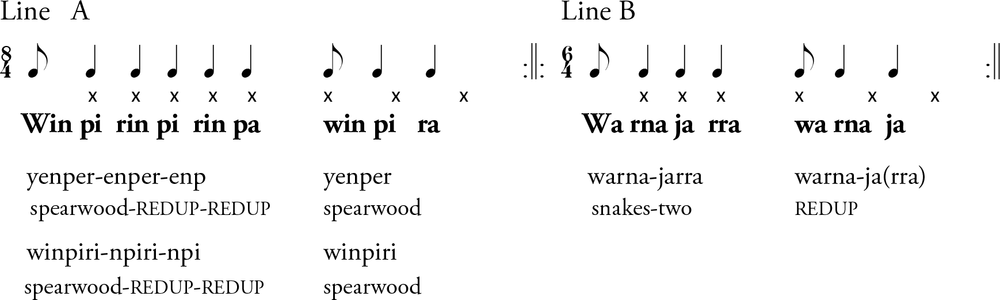

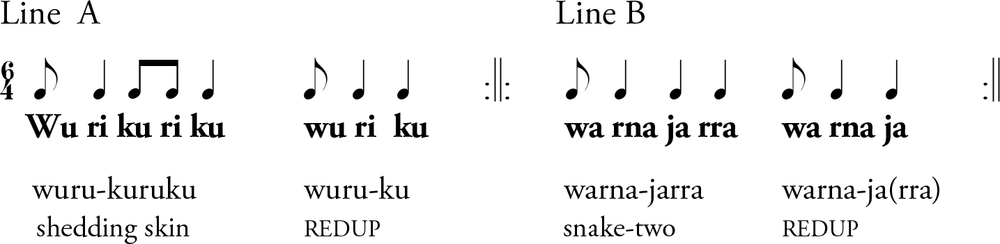

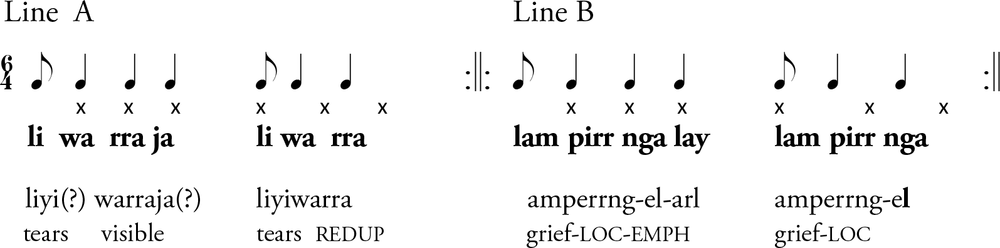

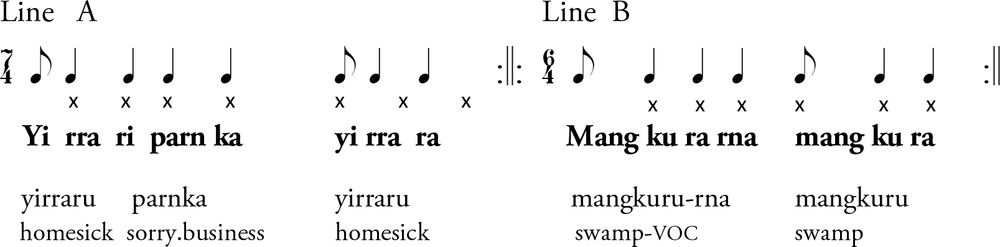

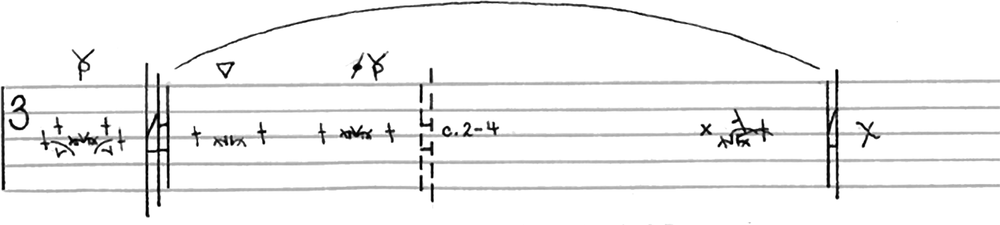

Approximately half the Warnajarra verses are in the fast syncopated meter, which often consists of some repeated text. Figure 7.10 (Verse 3) shows a verse in the fast meter, where reduplication can be seen with jartampa in Line A and lingkaji in Line B (lingkaji is, in fact, a triplication, as identified by the underlining). Clapping occurs on every crotchet beat. Figure 7.11 (Verse 2) shows a verse in the slow meter – in this case, slow triple meter with a regular clap accompaniment (marked by “x”) at a tempo of MM = 50 bps (represented as a dotted minimum in Figure 7.8). Slow meter often has no clap accompaniment (e.g., Figures 7.7 and 7.8). The slow meter may allude to the Moon Dreaming, which also intersects with Pawu.17

Figure 7.10 A Warnajarra verse in the fast meter, with 153 clap beats per minute (Verse 3). It is based on the words kana, ingkatyel and a form of either jurtampi or jutapi.

The slow meter verse in Figure 7.11 (Verse 2) has the same words as the verse in Figure 7.10 (Verse 3): jartampa and lingkaji. Comparing these two verses with the same words reveals how different patterns of reduplication and the use of different meters can produce vastly different verses.

In Figures 7.10 and 7.11, the immediate reduplication is either partial (e.g., lingkaji-ngkaji; jartampi-jarta) or, if it is identical, its rhythm contrasts (e.g., jartampa jartampa). Note that in the identical triplication, there is an intervening partial reduplication (lingkaji ngkaji lingkaji). Partial reduplication can be from the right edge, leaving out the initial syllable (li-ngkaji ngkaji), or from the left edge, leaving out the final syllable (jarta-mpi jarta).

Figure 7.11 A Warnajarra verse in the slow meter, with 50 clap beats per minute (Verse 2). Note that it is based on the same words as the verse in the fast meter in Figure 7.10 above.

These different patterns of reduplication can lead to different interpretations of what the speech words are, depending on whether one “hears” Warlpiri or Arandic speech equivalents. For example, lingka is a word for “snake” in Warlpiri, while ingka or angkety is “foot” in various Arandic languages. We return to this verse in more detail below, where we discuss triplication and the relationship between linguistic variety and reduplication type.

Reduplication

One of the most striking features of the Warnajarra verses is the use of reduplication. In speech, reduplication can be a means of word formation (e.g., English “hanky-panky”, “riff-raff”) or mark grammatical information, commonly plurality or repeated action. Other types of reduplication occur only in poetry and song, where it may be associated with specific meanings or used as a marker of the genre and a method of line formation. Reduplication can involve only part of a word, such as the consonants in “riff-raff” or the “anky” part of “hanky-panky”, or it can be an exact copy of the word, as is the case for contrastive focus in English. In poetry and song, reduplication can also be a means of line formation. In this section, we illustrate the different functions of reduplication and their many different forms found in Warnajarra. Reduplication, both total and partial, is a more significant feature of the Warlpiri lexicon than of the English lexicon (see Nash 1986).18

Lexical reduplication

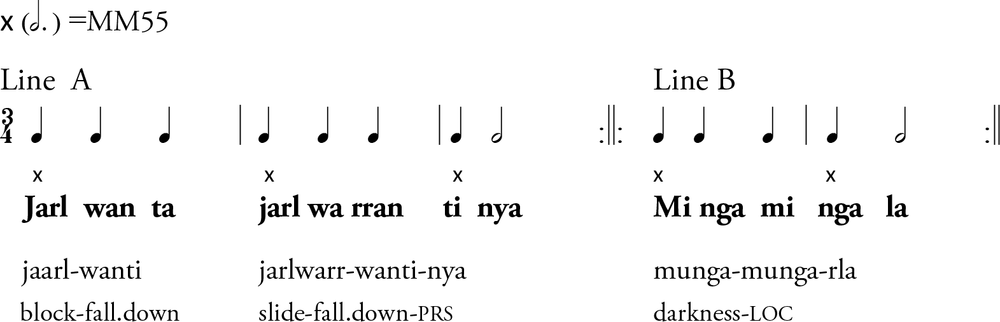

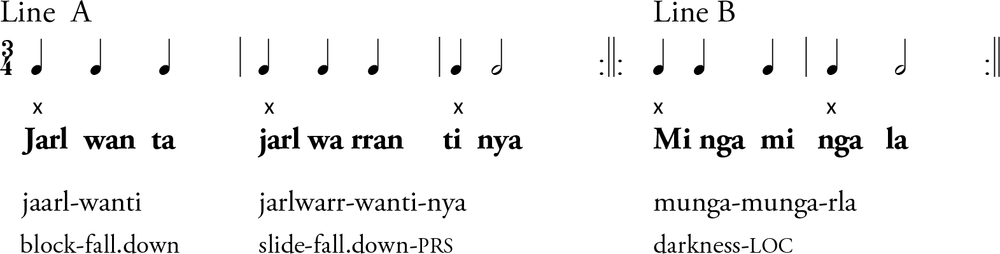

Lexical reduplication is common in spoken Warlpiri and song texts, including Warnajarra. Figure 7.12 (Verse 22) shows a Warnajarra verse that contains the Warlpiri word munga-munga “dark” (when sung, it is pronounced minga-minga), a lexical reduplication of munga “darkness, night”. This reduplicated word is also one of the names of Ancestral Dancing Women who travel from west to east in association with male initiation ceremonies. The reduplication forms the entire line (Line B).19

Figure 7.12 An example of lexical reduplication, munga-munga “darkness”, forming an entire line (Line B) in Warnajarra (Verse 22).

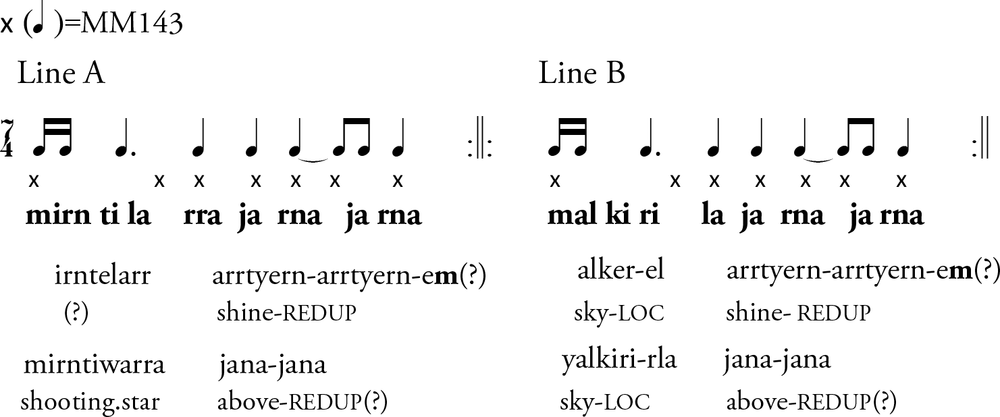

Lexical reduplication can also form just part of a line. This can be seen in both lines of the verse in Figure 7.13 (Verse 1), where the second (and final) word of each line is jarna-jarna.

Figure 7.13 A lexical reduplication jarna-jarna in the second half of the lines (A and B) in Warnajarra (Verse 1).

Jarna-jarna may be the Warlpiri word jarna-jarna, a genre of men’s ceremony, or (as a reviewer suggested) the reduplicated form of the everyday Warumungu word jana “above, high”, which is appropriate in this context.20 However, the line initial “m” suggests an Arandic source for both lines, as shown at the end of both lines in Figure 7.13.

Grammatical reduplication

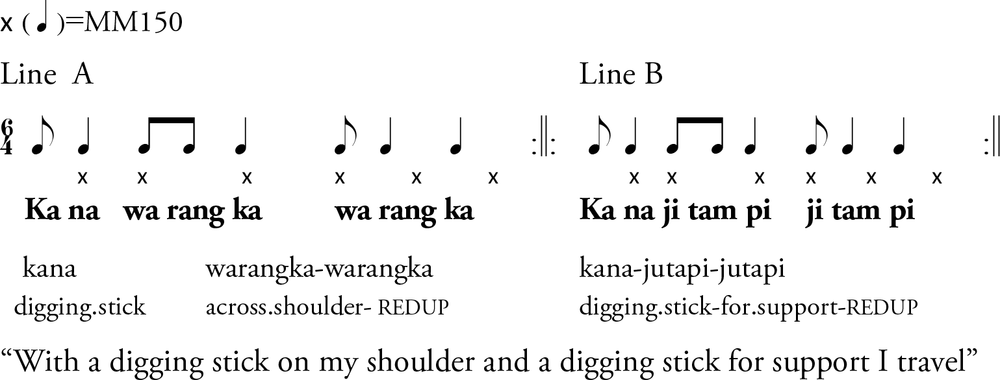

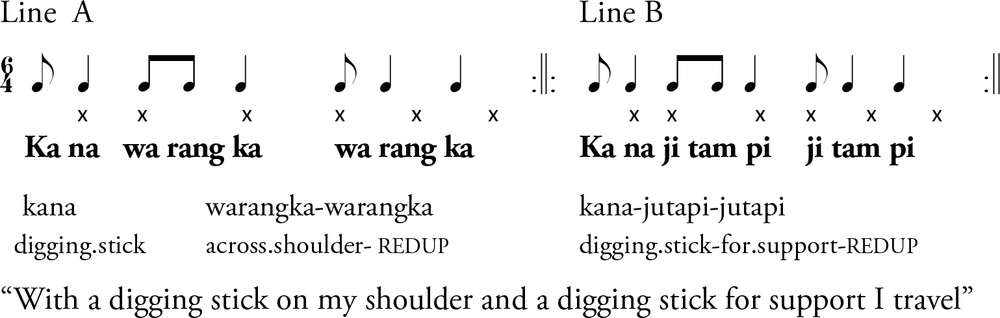

Grammatical reduplication is far more common in Warlpiri than English; unsurprisingly, it is also found in song texts, including Warnajarra. Figure 7.14 (Verse 4) shows a verse in the fast meter that contains grammatical reduplication, which signals a distributive action or multiple subjects. The second word of Line A, warangka “across the shoulders”, is reduplicated; thus, the phrase (and line) as a whole means “(multiple people) going along with a digging stick across their shoulder”. Line B contains a similar reduplication, although the speech equivalent of -jutapi “for support” is less certain.

Figure 7.14 Grammatical reduplication marking distributive action (Verse 4).

Notice that, in both lines, the base is set to a different rhythm than the reduplicant: ryq (base) and eq q (reduplicant). In the fast meter, the base has two short (S) notes followed by one long (L) note (i.e., SSL), while the reduplicant has SLL (short-long-long). In the fast meter, we see the greater use of long notes in the reduplicant as if it is an emphatic rendition of the base.

Word repetition

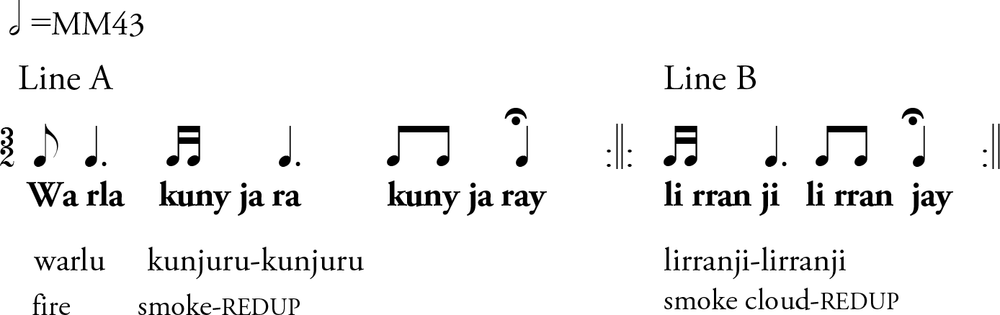

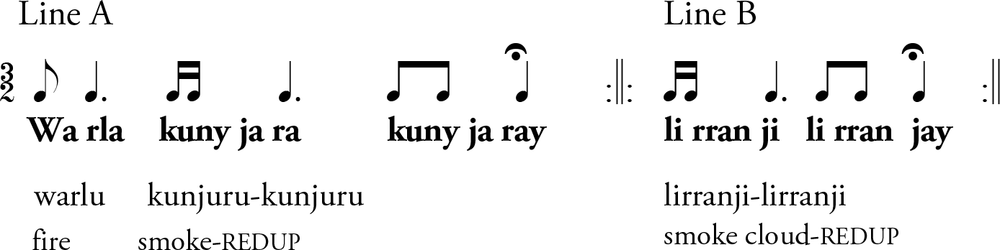

In Warnajarra, repetition of a nominal occurs, and it is unclear whether this is lexical or grammatical reduplication to create a word with a slightly different but related meaning21 or simply the repetition of a word forming two separate noun phrases. Figure 7.15 (Verse 19) shows a verse with word repetition in both lines. The second word of Line A repeats kunjuru “smoke”; and in Line B, lirranji – the only word in the line – repeats. The reduplicant in both words is in line-final position. The difference in the final vowel of the words (kunjura/kunjuray) is due to a process found only in song, where alteration of line-final vowels occurs to form a diphthong (written “ay”) in accordance with an ABBA pattern of line repetition (Turpin 2022).

Figure 7.15 Grammatical reduplication marking plurality (Lines A and B, Verse 19) in the slow meter (Verse 19).

There is no evidence from explanations given by singers that such word repetition creates a different meaning. Notice also how the repeated word is set to a different rhythmic pattern than the former: dg q. ryq, which may suggest a repeated word rather than a lexical reduplication. To the researcher’s ear, it is as if it is an emphatic or exaggerated repetition of the base.

In Figures 7.13, 7.14 and Line A of 7.15, the reduplication accounts for only some of the line as the first word in these lines is not reduplicated (mirntiwarri, kana, warlu). In contrast, the repetition in Figure 7.15, Line B (lirranji lirranji) accounts for the whole line; thus, this is also a method of line formation.

Poetic reduplication

The term “poetic reduplication” refers to reduplication that occurs only in song rather than speech; thus, its meaning is particular to and associated with yawulyu and presumably other aspects of the jukurrpa as this is what yawulyu pertains to. If such reduplications were used in speech, presumably, they would be used deliberately to allude to yawulyu. As a point of comparison, consider child-directed speech words, such as “wee-wees”, that connote a context of children. Poetic reduplication in Aboriginal song has been noted in other Central Australian songs (Strehlow 1971, 189; Turpin 2005, 204, 212), including in another yawulyu song from Pawu (Turpin and Laughren 2013). The remainder of the chapter identifies the different types of reduplication patterns, relating these to whether the speech equivalent is Warlpiri or Arandic and whether the accompanying meter is fast or slow.

Partial reduplication

In spoken Warlpiri, there are two principal types of partial reduplication, both of which involve the reduplication of a metrical foot that contains two (or three) vocalic mora. At the left edge of a word, the initial morpheme can be reduplicated and preposed to the base. This is especially productive with preverbs and verbs. Considering first preverbs, one example is jaka-jakarr-(w)apa “walk squeaking foot”. The partial reduplication of the manner preverb jakarr as jaka is in free variation with the total reduplication of the preverb (i.e., jakarr-jakarr-). Verb stems minus the inflectional suffix also reduplicate, such as panti-rni “pierce/poke” -> panti-panti-rni “pierce/poke many/repeatedly”. These productive grammatical reduplications contrast with lexical reduplication where the reduplicant is monomoraic, as in jarnjarn-paka-rni “chop into pieces”, kunykuny-ngarni “suck on”.22 Non-productive lexical reduplication is also a feature of some nouns, such as kirlil-kirlil-pa “Galah” or jintirr-jintirr-pa “Willy Wagtail” where -pa is added to the consonant-final reduplicant, thus creating a vowel-final word as required. Right edge reduplicants are of the form (C)CVCV, and these are not productive. The reduplicated CVCV foot may follow a monomoraic base (e.g., ji-wiri-wiri “rising smoke”; ja-rlantu-rlantu “roomy, spacious”) or a bimoraic foot (e.g., jirnta-rarra-rarra “squirting”; jurda-warra-warra “skipping”; laja-warra-warra(-pi-nyi) “get lots of”). These lexical right edge reduplicants can also be of the form CCVCV, where the initial C acts as a syllable coda to the preceding CV sequence (e.g., ja-rntarru-rntarru “on knees”). Warlpiri words cannot begin with a CC sequence, nor can they begin with the consonant “ly”, which is at the left edge of the reduplicant in ji-lyiwi-lyiwi “sizzle”. Preverbs or verb stems longer than two syllables may also be reduplicated, but always as total reduplications (e.g., pirltarru-pirltarru-yani “stretch out visible for a long way”). These are productive.

Taking Kaytetye as an example of a neighbouring Arandic language, total reduplication indicates plurality or an increase or decrease in the intensification of meaning and occurs with nominals, preverbs and noun formatives. Examples include the nominal arrilpe “sharp” -> arrilp-arrilpe “very sharp”; the preverb pererre “back and forth”, as in pererre ape- “go back and forth” -> pererre-pererre ape- “go back and forth lots of times”; and the noun formative awap- “block”, as in awap-arre- “block” -> awap-awap-arre- “block lots of things”. There is also partial reduplication of final CVCV in lexical items pwe-lyerrelyerre “dust, marks”.23 With some words, there are two possible analyses for the reduplication pattern, such as the Kaytetye word for “galah”, kelkelkelke, which could be analysed as ke-lelkelelke (12323) or kelelkelel-ke (12123). The 12323 reduplication patterns also occur in Kaytetye yawulyu, occurring in 14 of 90 lines (Turpin 2005, 221). The reduplication is also attested in the occasional longer lexical item, such as elerterre-kamekame “Australian kestrel”. Partial verb stem reduplication is more complex and not discussed here (for details, see Panther 2020).

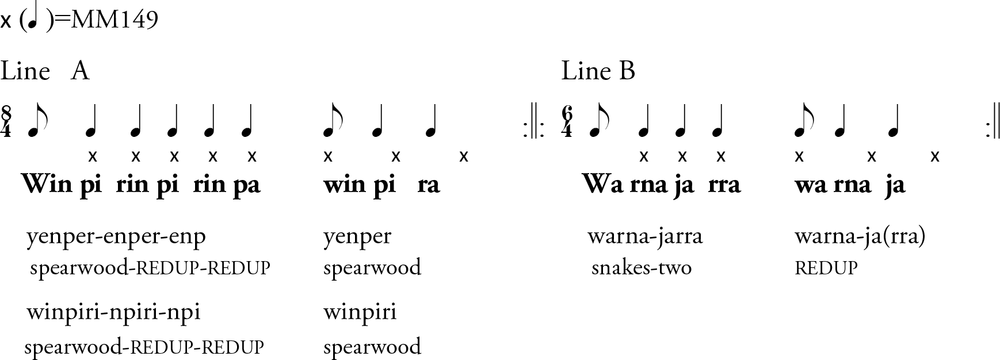

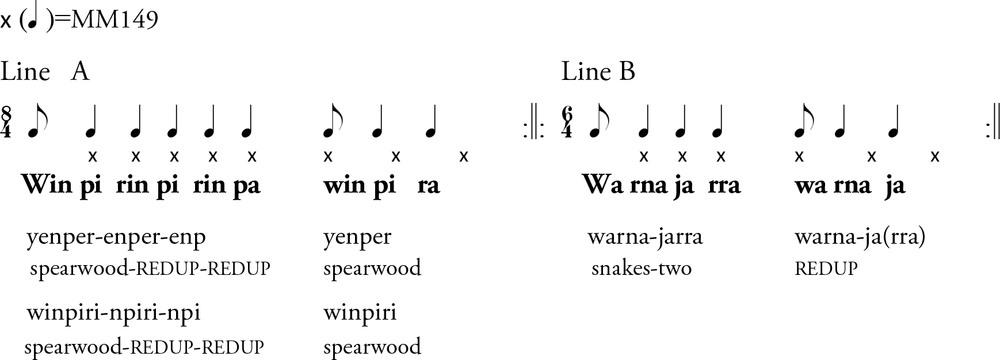

Poetic reduplication is typically partial reduplication. Figure 7.16 (Verse 8) is a partial reduplication that forms the entire line. It is in the fast meter. The “base” of the reduplication is a four-syllable word warna-jarra “snake-two”, and the “reduplicant” copies only the first three syllables (warnaja), leaving off the final syllable “rra”; thus, it copies from the left edge in a manner not found in the spoken language. Notice how the copied element warnaja has the exact same rhythm (SLL) in both the base and the reduplicant. Only the relationship between the clap beat (x) and the vocal line differs. In the base, the beat coincides with the second syllable; in contrast, in the reduplicant, it coincides with the first syllable. Copying of the rhythm is only attested in partial reduplication; whole reduplication always employs a different rhythm in the base and reduplicant.

Figure 7.16 Partial reduplication from the left edge – warnaja – with identical rhythm, base preceding reduplicant. Line B is in three Warnajarra verses: Verse 8 (shown here), 12 and 14.

The reduplication in Line A is discussed in subsection “Triplication”.

Partial reduplication from left edge, base before reduplicant

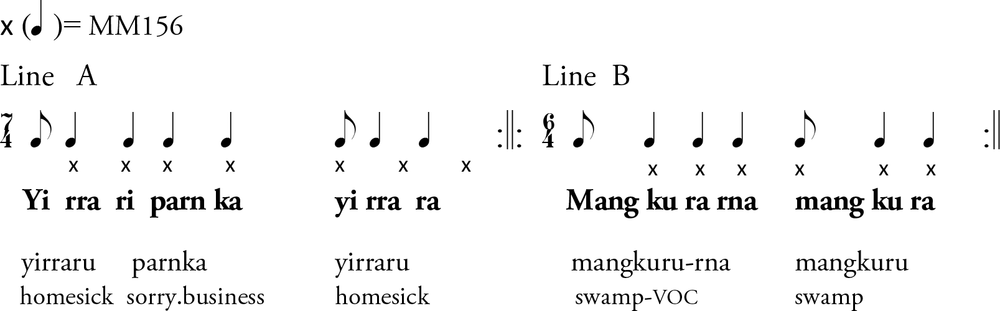

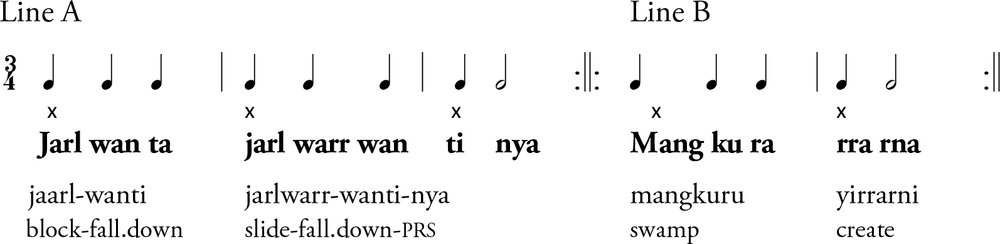

In Figure 7.16 (Verse 8), the partial reduplication starts from the left edge of the base; that is, syllables 123 (wa.rna.ja) are copied but not syllables 234 (rna.ja.rra). Left edge reduplication is frequently associated with words of Warlpiri origin, such as warna “snake”. In some left edge reduplication, a syllable is added rather than deleted before the word is repeated. This can be seen in Figure 7.17 (Verse 23), where the word mangkuru “swamp” has the syllable rna added before the word is repeated.24 This ensures the reduplication is not identical; here, there is an additional syllable and note in the “base”, while the reduplicant is only three syllables. The syllable rna is a vocable in other Warlpiri yawulyu (Turpin and Laughren 2013) and Kaytetye yawulyu (Turpin 2005, 212), where it occurs as the final syllable of a metrical unit. Note that this is homophonous with the 1sg pronoun “I”.

Figure 7.17 Base that has a vocable as its final (fourth) syllable. Reduplication from left edge of word, base followed by reduplicant. Fast meter (Verse 23).

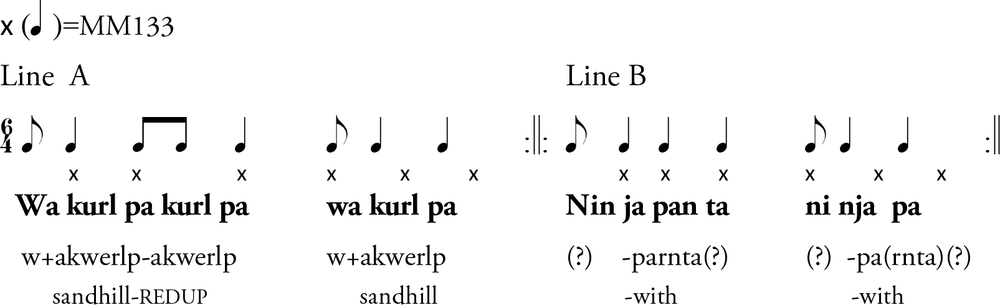

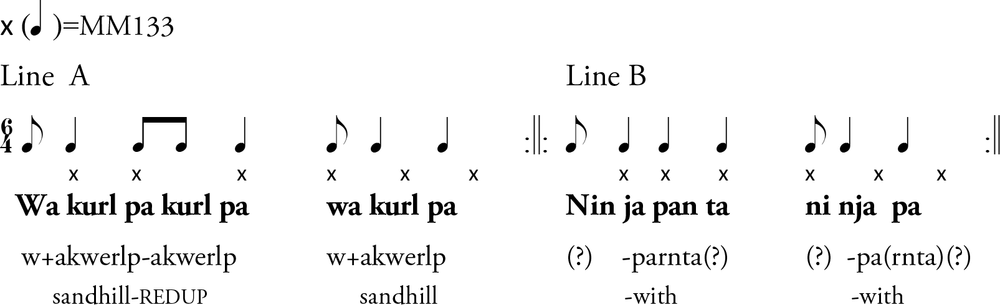

The same pattern of partial reduplication from the left edge, with the same rhythm, can be seen in Line B of the verse shown in Figure 7.18 (Verse 15). In this instance, the fourth syllable appears to be part of a suffix. The base is a phrase “ninjaparnta”, whose meaning is unknown. The final element “rnta” is omitted in the reduplicant. This pattern of partial reduplication can be represented as 1234 123.

Figure 7.18 Partial reduplication from the left edge – ninjapa – with identical rhythm, base followed by reduplicant. Line B, fast meter (Verse 15).

Partial reduplication from left edge, base after reduplicant

Thus far, we have seen partial reduplication from the left edge where the base precedes the reduplicant (Figure 7.18, Verse 15; Figure 7.17, Verse 23; Figure 7.16, Verse 8). In the line Warnajarra-warnaja (Figure 7.16, Verse 8), we know that warna-jarra is the base because it is a word, while warnaja is not a word and is thus considered the reduplicant. Consider the line in Figure 7.19 (Verse 6). Here, the base comes after the reduplicant. That is, the four-syllable word warna-jarra follows the three-syllable reduplicant. Line A of this verse follows the same pattern, with the three-syllable reduplicant preposed to the four-syllable base. While it is possible to analyse warnaja in Line B as warna-ja or warna-ju where the third syllable is an assertive or topic-marking clitic, such an analysis of wirrima in Line A is not available as this is not a word and there is no monosyllabic suffix or enclitic -ma. If the base contains the imperative verb ma-nta, then this reduplication differs from the productive reduplication of a preverb or verb stem since both are copied here. Notice that the partial reduplication again copies the rhythm of the base; however, as it omits the final syllable, it is not identical reduplication.

Figure 7.19 Base after reduplicant in both lines of the verse. Partial reduplication from the left edge base after reduplicant. Fast meter (Verse 6).

In Figure 7.19 (Verse 6), the three-syllable reduplicant warnaja precedes the base. What is so striking about this verse is not so much that the base comes after the reduplicant but that the same text is used for both orderings: warnajarra-warnaja (base + reduplicant), warnaja-warnajarra (reduplicant + base).

Figure 7.19 represents the verse as sung in the 1981 performance. In the 1982 performance, this verse was sung with the hemistiches reversed in each line: wirrimanta wirrima / warnajarra warnaja, thus changing the reduplication pattern to base before reduplicant, as in Figures 7.17 and 7.18. This is the only verse where the order of hemistiches differs in a subsequent performance.

Partial reduplication from right edge

Another pattern of partial reduplication is 12323. Here, the initial syllable of the line is not repeated. Such “right edge” reduplication occurs when the speech equivalent is of Arandic origin. Figure 7.20 (Verse 17) shows a line comprised of this pattern. The line is based on the Arandic word atywerrk “native fig” (Ficus platypoda).25 This word is reduplicated, and the consonant “w” added to the beginning.26 Thus, what appears as partial reduplication from the right edge is constructed from whole reduplication of an Arandic word, and a consonant is added as lines must be consonant initial (Turpin 2007a). Although wijirrki “native fig” exists in Warlpiri, and neighbouring Warumungu, its origins are possibly Arandic as the rounded vowel in song points to the Arandic form.

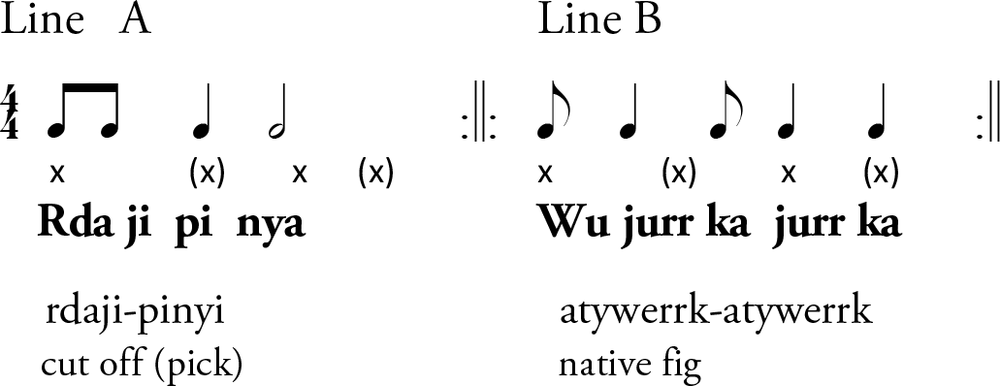

Figure 7.20 Partial reduplication from right edge: Arandic base atywerrk reduplicated and consonant added to beginning (Verse 17).

The 12323 partial reduplication is widespread in the neighbouring Kaytetye language not only as a form of lexical words (e.g., pwelyerrelyerre “dust”)27 but also as a method of line formation in yawulyu. Turpin (2005, 212) found that 14 lines of a Kaytetye rain song set conform to this pattern.28

Triplication

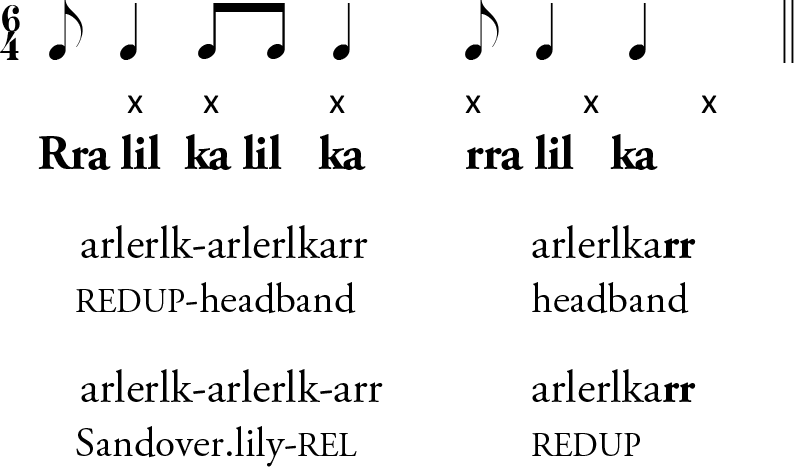

In Figure 7.21 (Verse 3), we see partial reduplication from the right edge: lingkaji-ngkaja.29 Right edge reduplication in Warnajarra is frequently associated with words of Arandic origin, as argued in the previous section. We suggest that Line B is based on an Arandic word ingkaty “foot”, which has various forms in Arandic languages today.30 The word is reduplicated (ingkaty-ingkaty), and the consonant “l” is added to the beginning of the word, thus conforming to lines starting with a consonant (the source of the “l” is discussed below the Figure). The first three syllables are further repeated (a pattern 123 23 123), forming a line of eight syllables through “triplication”.

Figure 7.21 Partial reduplication from the right edge: Line B consists of syllables that repeat in a triplication pattern of 123 23 123 (Verse 3).

The initial consonant “l” is most likely the Arandic instrumental suffix -el; thus, the phrase is ingkaty-el “(go) by foot”.31 The suffix -el marks each as a separate word, as opposed to the internal reduplication in ingkaty-ingkaty-el.

As in most verses from this song set, each line is repeated before commencing the other line. The process of transferring the final consonant of the line-final suffix to the beginning of a line, followed by repetition for a Warlpiri verse (in Anmatyerr language), is one outlined by Hale (1984, 261). In the figures the transferred consonant is in bold face. In the fast meter, many Warnajarra lines, such as that shown above, are formed through this pattern of triplication. On the surface, it appears to be a partial reduplication from the right edge; however, as we have shown, it is partial reduplication from the left edge of an Arandic base ingkaty-ingkatyel followed by consonant transfer and resyllabification.

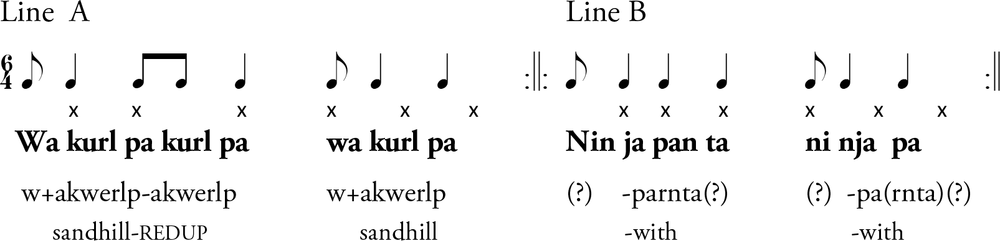

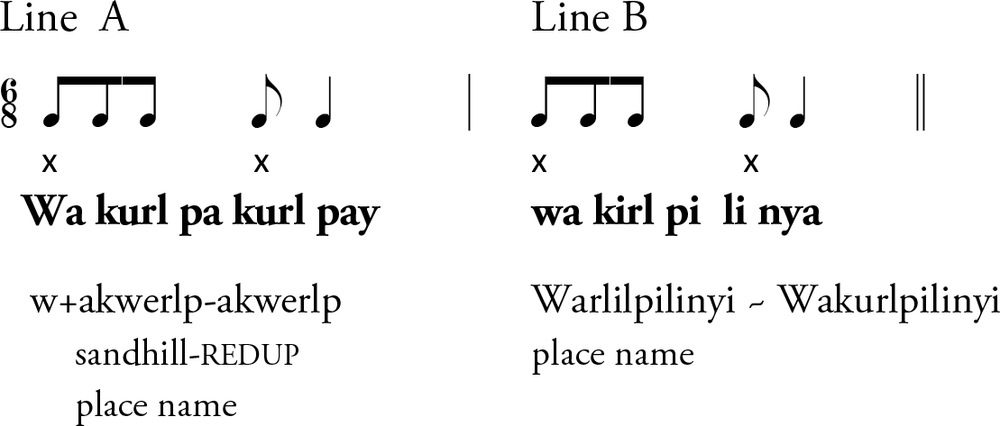

Some lines of the 123 23 123 pattern add an initial consonant rather than transferring the final consonant. As has been observed for Arandic yawulyu, such consonant transfer is only possible if the final consonant is a monosyllabic suffix – not when it is part of the root (Hale 1984; Turpin 2005). Figure 7.22 (Verse 15) shows one such line. The line is based on the Arandic word akwerlp, which has related but different meanings in Arandic languages.32 The word akwerlp is reduplicated, and a consonant “w” is added to the beginning of the word/line: w+akwerlp-akwerlp-a, creating a five-syllable form. The three-syllable “base” is then repeated: w+akwerlp-akwerlp-a w+akwerlp-a. As with wijirrki “native fig”, Wakurlpu also exists in Warlpiri as a place name, but this place name is not what this verse refers to.

Figure 7.22 Triplication with partial reduplication from the right edge. Fast meter (Verse 15, Line A).

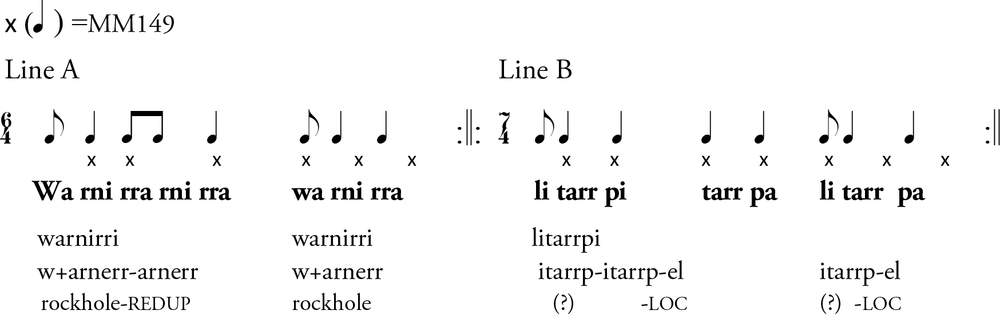

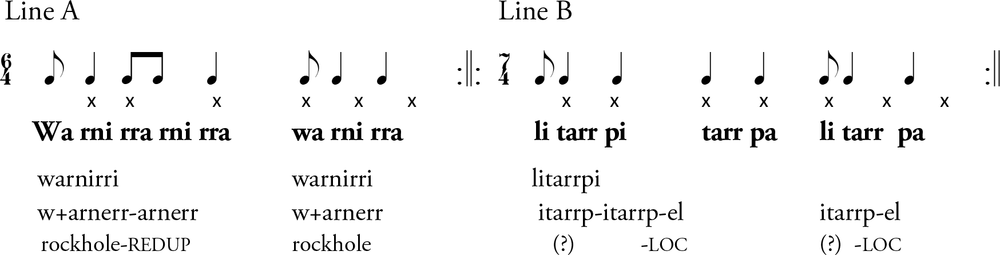

Notice how the rhythm differs in every iteration of the repeated syllables: SLS SL SLL. The 123 23 123 pattern of line formation through triplication can be seen in both lines of Verse 26 (see Figure 7.23). Line A may be based on the Arandic word arnerre “rockhole”, reduplicated, and the consonant “w” again inserted at the beginning of the word.33 Line A again has a unique rhythm for each repeated sequence, the same rhythm as seen in Figure 7.22 (Verse 15). In contrast, Line B has the same rhythm for the base and the “triplicant” SLL LL SLL; however, the final vowel differs in the base litarrpi from the reduplicant and triplicant litarrpa. In this line, a syllable has the same rhythm in all three iterations. It is not known what speech equivalent (if any) corresponds to the base, although the initial “l” and the reduplication from the left edge of the line suggests an Arandic speech equivalent.34

Figure 7.23 Triplication with partial reduplication from the right edge. Contrasting rhythm in Line A; identical rhythm in line B. Fast meter, Verse 26.

A more complicated triplication can be seen in Figure 7.24 (Verse 8). Here, a three-syllable base is repeated, and a syllable is added to form a nine-syllable line. Given that words do not end in a consonant, the base can be considered winpiri. This has a number of possible speech equivalents: one is “spearwood” (Pandorea doratoxylon), a borrowing from Arandic (u)yenpere “spearwood”.35 While the speech equivalent is uncertain, we can say that the base is partially reduplicated from the right edge, reduplicating all but the initial consonant win.pirin.pirin. The syllable -pa is added to this consonant-final string, win.pirin.pirin.pa.36

Figure 7.24 Triplication with partial reduplication from the right edge and additional syllable. Fast meter (Verse 8).

This pattern of reduplication can also be seen in Chapter 6, with Song 30, Line B, second hemistich:

| winpirin | pirinpa |

| yalkarlirl | karlila |

| 1 2 3 | 2 3 4 |

As we have seen, reduplication from the right edge is associated with words of Arandic origin as these words are vowel initial, and Warlpiri adds a consonant to the front of these, which is not reduplicated. In contrast, left edge reduplication is associated with words of Warlpiri (and possibly Warumungu) origin, as we saw with warna “snake”, mangkuru “swamp in open country” and wirri “gully”.

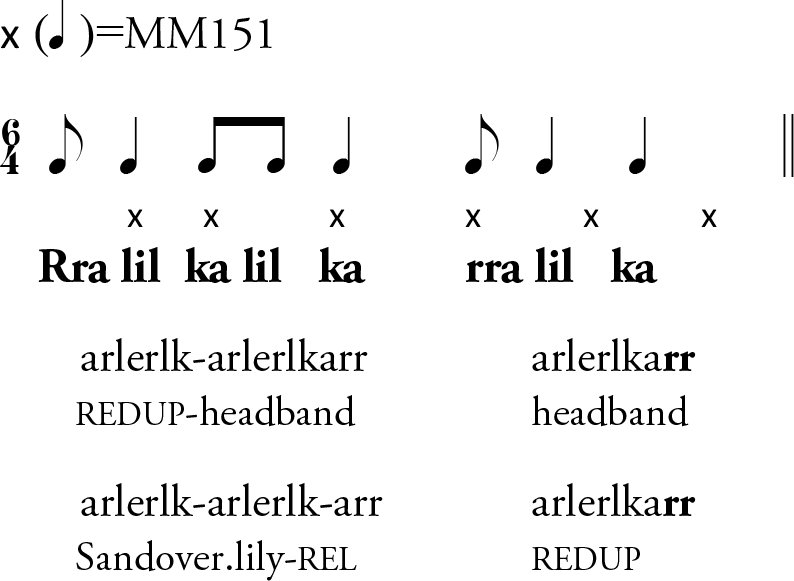

A further right edge triplication is illustrated in Figure 7.25 (Verse 7). This is a verse comprised of only one line, based on a single Arandic word arlerlk-arlerlk “Sandover Lily” (Crinum flaccidum; Green 2008, 66).37 This word is a lexical reduplication and serves as the base for the partial reduplicant that follows. The source of the line-initial consonant “rr” – which is not a permitted word-initial consonant in Warlpiri – may be the Kaytetye relative suffix -arr. Line-final “rr” is transferred to the line-initial position, and the word-final “rr” internal to the line resyllabifies to form the onset of the reduplicant. This pattern is the same as discussed regarding Figure 7.21 (Verse 3): alyerlk-alyerk-arr alyerlk > rr-alyerlk-alyerlka- rr-alyerlka-.

Figure 7.25 Right-edge triplication: 123 23 123. Fast meter (Verse 7, one line only).

Here, we have another interesting instance of “deliberate” ambiguity. A competing analysis of the word in Figure 7.25 (Verse 7) is the phonologically similar word for a woman’s white headband used in yawulyu performances: iylerlkarr is the Anmatyerr respect language term. The semantic association between these two words lies in their whiteness; the white headband stands out on the women’s heads, while the white flower of the Sandover Lily stands out when it blossoms after good rains. There is also a shared erotic connotation; yawulyu enhances female attractiveness and may attract illicit relations, while the onion-like tuber of the Sandover Lily is poisonous, a symbol of illicit relations in some yawulyu verses. In both cases, what may appear attractive is dangerous if consumed. As the final “rr” in iylerlkarr “headband” belongs to the word and is not an inflectional suffix or enclitic, it is not a candidate for consonant transfer. Thus, we retain the alyerlk-alyerlk “Sandover Lily” analysis of the literal text.

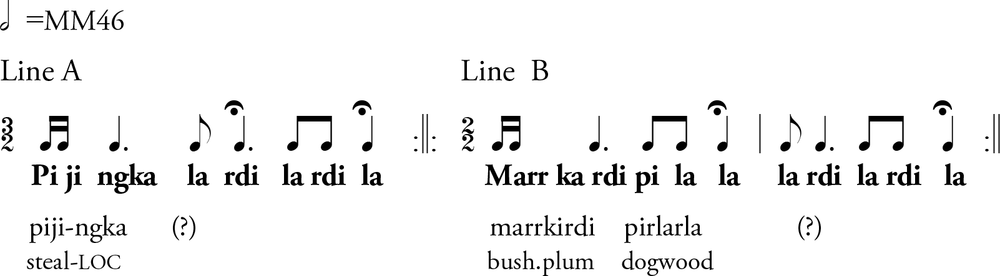

Partial reduplication, partial line

In addition to various patterns of partial reduplication as a method of line formation, partial reduplication can also occupy only some of a line. This can be seen in Figure 7.26 (Verse 27), which is a verse in the slow meter. Here, the initial text, pijingka, which means “pinching with the fingers”, is not reduplicated, whereas the last five syllables contain a partial reduplication, lardi-lardila, a sequence of 12 123. Although the word from which the reduplication is derived is unknown, it is likely that the base follows the reduplicant because the longer form, lardila, is likely the base.

Figure 7.26 Partial reduplication lardi-lardila. Slow meter (Verse 27).

Reduplication that forms only part of the line was also seen in kana-jutampi-jutampi (Figures 7.10, Verse 3 and 7.11, Verse 2), where the speech equivalent may be a single phrase comprised of a lexical reduplication.

Conclusion

Warnajarra is characterised by much poetic reduplication of varying patterns: partial and whole; from the right edge and left edge of the line; word repetition; and even “triplication”, including patterns not found in spoken Warlpiri. This contrasts with many other Warlpiri and Arandic yawulyu, where the text appears closer to spoken language. While other yawulyu have examples of reduplication, the reduplication in these is more like reduplication found in everyday speech: grammatical and lexical reduplication. Like other yawulyu from the eastern Warlpiri region, which contain both Arandic and Warlpiri vocabulary, Warnajarra shows up different patterns of reduplication tied to the language variety – Arandic vocabulary is associated with reduplication patterns from the right edge and may involve line-initial consonant addition and transfer. In contrast, productive Warlpiri reduplication occurs only from the left edge.

A feature of reduplication in Warnajarra is that the base and its reduplicant are either not textually identical or, if they are, these are set to different rhythms. This near-identity convention is also found in other yawulyu, including that from Pawu (Turpin and Laughren 2014) and in neighbouring Kaytetye (Turpin 2007a, 103). While reduplication occurs in verses of both meters of Warnajarra (fast and slow), it is a more characteristic feature of verses in the fast meter. Fast meter verses tend to relate to the Warnajarra ancestors, whereas the slow meter verses seem to relate to other jukurrpa whose path is crossed by Warnajarra. The association of musical style with different sociopolitical groups was noted early on by musicologists such as Catherine Ellis:

The portion of a song which refers to sacred places within the care of a local group may be performed only by members of that group and it is in their own musical idiom. (Ellis 1966, 138)

Later, Ellis (1985, 92) argued that melody encodes the essence of an ancestral being in Western Desert songs. In the case of Warlpiri yawulyu, rhythm and tempo may also play a significant role in musical representation of the ancestral being. The relationship between the Warnajarra meters and their subject matter requires further investigation.

Without knowing the conventions of song creation, including the complex reduplication patterns we find in Warnajarra, and the different treatment of Arandic vocabulary, it would not be possible to “find” new Warnajarra yawulyu song texts. This knowledge was traditionally acquired through frequent attendance at yawulyu performances and engagement in singing alongside older and more knowledgeable singers. Notably, we find an example of innovation in the yawulyu visual design accompanying song. Perhaps the modern and transformative practices of Indigenous painting on canvases (as well as, e.g., paper, material, cars), widespread across Australia, has somehow influenced Peggy Nampijinpa’s “finding” of a new yawulyu design. Young and old Warlpiri people participate in creating visual designs that relate to traditional jukurrpa and employ traditional graphic motifs while introducing many innovative features, with economic opportunities arising from this. In contrast, fewer people have learned traditional song over the past 40 years. The unfamiliarity of this style of singing was evident to Mary Laughren in 2014 when Elder Jerry Jangala Patrick taught a purlapa (created in the 1980s) to younger Warlpiri people in the Lajamanu Church; they had difficulty mastering the rhythmic texts, whose conventions differ from speech in many ways, some of which have been demonstrated in this chapter. This contrasted with Mary’s experience in the 1980s when these songs were created and learned by Warlpiri with ease. Certainly, Warlpiri people today are fluent in a wide variety of musical genres, composing and performing in Warlpiri; yet rarely (if ever) are the traditional conventions for associating text and rhythm incorporated into these other genres. This contrasts with the visual arts where elements of traditional Warlpiri iconography are drawn on in contemporary artistic practices.

References

Breen, Gavan. 2001. “The Wonders of Arandic Phonology”. In Forty Years On: Ken Hale and Australian Languages, edited by Jane Simpson, David Nash, Mary Laughren, Peter Austin and Barry Alpher, 45–69. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Brown, Reuben, David Manmurulu, Jenny Manmurulu, Isabelle O’Keeffe and Ruth Singer. 2017. “Maintaining Song Traditions and Languages Together at Warruwi (Western Arnhem Land)”. In Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia, edited by Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin, 257–74. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Clunies Ross, Margaret, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Wild (eds). 1987. Songs of Aboriginal Australia (Oceania Monograph 32). Sydney: University of Sydney.

Curran, Georgia, Linda Barwick, Myfany Turpin, Fiona Walsh and Mary Laughren. 2019. “Central Australian Aboriginal Songs and Biocultural Knowledge: Evidence from Women’s Ceremonies Relating to Edible Seeds”. Journal of Ethnobiology 39(3): 354–70. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-39.3.354

Dail-Jones [Morais], Megan. 1984. “A Culture in Motion: A Study of the Interrelationship of Dancing, Sorrowing, Hunting, and Fighting as Performed by the Warlpiri Women of Central Australia”. Master of Arts thesis, University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Dail-Jones [Morais], Megan. 1992. “Documenting Dance: Benesh Movement Notation and the Warlpiri of Central Australia”. In Music and Dance of Aboriginal Australia and the South Pacific (Oceania Monograph 41), edited by Alice Moyle, 130–43. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Dail-Jones [Morais], Megan. 1998. “Warlpiri Dance”. In The International Encyclopedia of Dance (vol. 1), edited by Selma Jean Cohen, 227–29. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, Catherine. 1966. “Aboriginal Songs of South Australia”. Miscellanea Musicologica 1: 137–90.

Ellis, Catherine. 1985. Aboriginal Music, Education for Living: Cross-Cultural Experiences from South Australia. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Fabricius, Anne H. 1998. A Comparative Survey of Reduplication in Australian Languages (Studies in Australian Languages 3). Munich: Lincom Europa.

Green, Jennifer. 2008. Eastern and Central Anmatyerr to English Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

Ghomeshi, Jila, Ray Jackendoff, Nicole Rosen and Kevin Russell. 2004. “Contrastive Focus Reduplication in English (the SALAD-Salad Paper)”. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 22(2): 307–57.

Hale, Ken. 1984. “Remarks on Creativity in Aboriginal Verse”. In Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, edited by Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington, 254–62. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Koch, Grace and Myfany Turpin. 2008. “The Language of Central Australian Aboriginal Songs”. In Morphology and Language History. In Honour of Harold Koch, edited by Claire Bowern, Bethwyn Evans and Luisa Miceli, 167–83. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Laughren, Mary, Kenneth Hale, Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan, Patrick Marlurrku, Paddy Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1966. Gadjari Among the Walbiri Aborigines of Central Australia (Oceania Monograph 14). Sydney: The University of Sydney.

Morais, Megan. 1981–1982. “Fieldnotes of [Warlpiri] Women’s Ritual Business at Willowra, NT (3) Meetings: 120–130” [unpublished manuscript]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Morais, Megan, Lucy Nampijinpa Martin, Peggy Nampijinpa Martin, Helen Morton Napurrurla, Janet Nakamarra Long, Maisie Napaljarri Kitson, Maureen Nampijinpa O’Keefe, Clarrie Kemarr Long, Jeannie Nampijinpa Presley, Marjorie Nampijinpa and Brown, Selina Napanangka Williams, Leah Nampijinpa and Martin and Myfany Turpin. In press. Yawulyu: Art and Song in Warlpiri Women’s Ceremony. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Munn, Nancy. 1973. Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Nash, David. 1986. Topics in Warlpiri Grammar (Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics, Third Series). New York: Garland Publishing Inc.

Panther, Forrest. 2020. Topics in Kaytetye Phonology and Morpho-Syntax. PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, Newcastle.

San, Nay and Myfany Turpin. 2021. “Text-setting in Kaytetye”. In Proceedings of the 2020 Annual Meeting of Phonology, edited by Ryan Bennett, Richard Bibbs, Mykel Loren Brinkerhoff, Max J. Kaplan, Stephanie Rich, Amanda Rysling, Nicholas Van Handel and Maya Wax Cavallaro, 1–9. Columbia: Linguistics Society of America. https://doi.org/10.3765/amp.v9i0.4911

Strehlow, T.G.H. 1971. Songs of Central Australia. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Turpin, Myfany. 2005. Form and Meaning of Akwelye: A Kaytetye Women’s Song Series from Central Australia. PhD thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/1334

Turpin, Myfany. 2007a. “Artfully Hidden: Text and Rhythm in a Central Australian Aboriginal Song Series”. Musicology Australia 29: 93–107.

Turpin, Myfany. 2007b. “The Poetics of Central Australian Song”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 100–15.

Turpin, Myfany. 2022. “End Rhyme in Aboriginal Sung Poetry”. In Rhyme and Rhyming in Verbal Art, Language, and Song, edited by Venla Sykäri and Nigel Fabb, 213–28. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. https://doi.org/10.21435/sff.25

Turpin, Myfany and Mary Laughren. 2013. “Edge Effects in Warlpiri Yawulyu Songs: Resyllabification, Epenthesis and Final Vowel Modification”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 33(4): 399–425.

Turpin, Myfany and Mary Laughren. 2014. “Text and Meter in Lander Warlpiri Songs”. In Proceedings of the 43rd Australian Linguistic Society Conference 2013, 1–4 October, 398–415. Melbourne, University of Melbourne.

Turpin, Myfany and Alison N. Ross. 2012. Kaytetye to English Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

Vaarzon-Morel, Petronella (ed.). 1995. Warlpiri Women’s Voices: Warlpiri Karntakarnta-Kurlangu Yimi: Our Lives Our History. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

Wafer, James and Petronella Wafer. 1980. The Lander Warlpiri/Anmatjirra Land Claim to Willowra Pastoral Lease. Alice Springs: Central Land Council.

Walsh, Michael. 2007. “Australian Aboriginal Song Language: So Many Questions, So Little to Work With”. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 128–44.

Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Georgia Curran (ed.). 2017. Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu [including DVD]. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Appendix 7.1 Warnajarra Verses

Poetic words, reduplication and words of Arandic origin are shown in grey. These may be words from neighbouring languages and/or words only used in song. Following an Aboriginal word, (?) signals that this is not a confirmed speech equivalent; following an English word, it signals that this is not a confirmed meaning.

Linguistic glosses are as follows:

1sg = 1st person singular; aux = auxiliary; cnt = continuous aspect; imp = imperative; inst = instrumental; loc = locative case; np = non-past tense; pl = plural; prs = present tense; RDPL = reduplication; rel = relativiser, voc = vocable.

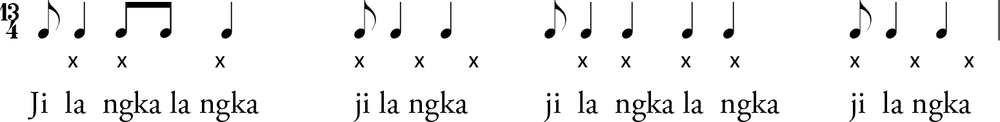

Verse 1

x (q)=MM143

Verse 2

x (h.)=MM50

Verse 3

x (q)=MM153

Verse 4

x (q)=MM150

Verse 5

h=MM42

Verse 6

x (q)=MM144

Verse 7

x (q)=MM151

Verse 8

x (q)=MM149

Verse 1038

x (q)=MM140

Verse 11

h=MM48

Verse 12

q=MM139

Verse 13

q.=MM125

Verse 14

x (q)=MM136

Verse 14 (variant)

Verse 15

x (q)=MM133

Verse 16

x (q.)=MM81

Verse 17

x (q)=MM138

Verse 18

h=MM44

Verse 19

h=MM43

Verse 20

h=MM43

Verse 21

x (q)=MM165

Verse 22

x (h.)=MM55

Verse 23

x (q)=MM156

Verse 24

x (h.)=MM58

Verse 26

x (q)=MM149

Verse 27

h=MM46

Verse 28

h=MM46

Verse 30

h=MM60

Verse 33

q.=MM 68–71

Appendix 7.2 Benesh notation for the dance accompanying (Verse 13 and 33)

MBW-A: ‘majardi’

Lorraine Nungarrayi Granites

Nungarrayi grew up in Willowra but lived a lot of her adult life in Yuendumu after she married. She is kirda for the Wurrpardi and Ngatijirri jukurrpa from the Country near Willowra. She is a senior female song leader and knows and sings a large repertory of yawulyu songlines as she has participated in ritual life since she was a young girl. Nungarrayi has worked tirelessly on the recording and documentation of women’s yawulyu, especially in the DVD production Yurntumu-Wardingki Juju-Ngaliya-Kurlangu Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu (Warlpiri Women from Yuendumu and Curran 2017) and is central to the biannual Southern Ngaliya dance camps through which she teaches this cultural knowledge to younger generations. Nungarrayi was involved in the establishment and maintenance of the Yuendumu Old People’s Program in Yuendumu, where she worked for many years.

Jalangukuju yangka yawulyulkurlupa-jana milki-yirrarnilki … Nyampunya karnangku kijirni nyampuju nyuntu-nyangu ngurrara karnangku kijirni nyampuju, nyuntu-nyangu warringiyi-kirlangu.

Today, we sing the jukurrpa for our young generations and we say to them while we paint them that these are their grandfather’s (father’s father’s) songs.

Yunparnilki karnalu nyampu nawu, kijirni kujakarnalu, yunparninja-karrarlu. Yuwayi warringiyi-kirlangu papa-kurlangu. Yuwayi warringiyi-kirlangu papa-kurlangu.

We sing about the Country, and we paint while singing. The grandfather’s and the father’s jukurrpa.

Kajikanparla wait-jarri kurdungurluku yinyaju, you can wait kurdungurluku.

Kajinpa juju-wardingki nyina, ngulaju yantarni. Kajikanparla wait-jarri kurdungurluku yinyaju, you can wait kurdungurluku. Kaji kangku ngula-juku yanirra kajikangku yajarnilki, “Yantarni nyanjaku!”

You have to wait for the kurdungurlu. If you are a ceremonial person, well, just come along. You have to wait for the kurdungurlu. They are the ones that say you can come to the ceremony. “Come to see!”

George (Cowboy) Jungarrayi Ryder

Known to many as “Cowboy”, Jungarrayi sadly passed away in 2020. As a senior Warlpiri man and kirda for Ngunulurru and Yinapaka in the Lander region, Jungarrayi led the Willowra Ngajakula revitalisation project. Jungarrayi’s deep knowledge was gained through a life lived on the land. He was born about 1935 “in the bush” near Mungakurlangu on the Lander. Jungarrayi recalled that his father, Fred Japaljarri Karlarlukarri, and mother, Beryl Nakamarra, took him around the Country and:

Taught me everything. They told me, “Don’t do the wrong thing, you’ve got to follow your grandfathers.” The kurdungurlu and old people taught me the stories about Country way, jukurrpa, the law. I walked everywhere, all over, without shoes, in the early days, no flour, in the bush before Welfare.

One day, while young, Jungarrayi was picked up on a truck and taken to work around Willowra station. On that occasion, he ran away, but later he worked as a stockman on Anningie, Willowra and other stations, building windmills, yards and fences, and droving cattle. He was given the name “Ryder” because he was “among horses all the time”. Throughout this time, Jungarrayi maintained an intimate relationship with the land and continued to learn “from the old people”. He remembered them as “really knowledgeable, important old men, living together jintangka [“in one, united”], jurdalja way,39 kirda and kurdungurlu, no argument”.

Jungarrayi was kurdungurlu for the Jardiwanpa jukurrpa “as far as Tilkiya” and kirda for Ngajakula on the lower Lander. He was an expert, juju-ngaliya, running all the business. As an Elder, Jungarrayi took seriously his responsibility to instruct younger generations about jukurrpa. He shared his knowledge generously, teaching his family and other Lander families about their Countries. He also taught kardiya, while working tirelessly for his people on numerous collaborative intercultural projects, including the Willowra cultural mapping project, native title claims, and with Warlpiri rangers and Central Land Council land managers regarding fire and other caring-for-Country activities. Jungarrayi was a wise, dignified teacher and a deeply caring family man who left a rich legacy. He was pleased to have recorded Ngajakula and happy to share the story. The following chapter is in memory of Jungarrayi.

1 Warna “snake”, -jarra “two of”.

2 Peggy Nampijinpa to Helen Morton and Myfany Turpin, 18 August 2019, recording 20190816-1, 6’33”. To be archived at AIATSIS.

3 This research was supported by a grant from AIATSIS in 1981.

4 This research was supported by three Australian Research Council grants: LP0560567, FT140100783 and LP140100806.

5 Later in 1982, the audio recording was translated during a meeting with the women, and the accompanying dance movements were discussed.

6 The musical Figures represent a verse. The top row is the speed of the clap beat (“x”) accompanying the singing (showing both 1982 and 2019 tempo). Where the verse is divided into two lines, these are indicated as “A” and “B”. The row underneath is a rhythmic representation of the vocal line, and the dotted double lines show that the line repeats before moving on to the other line. The row beneath this is the sung syllables. The rows beneath this show the Warlpiri and/or Arandic speech equivalents with an English gloss or linguistic abbreviation in small caps underneath. Poetic words and reduplication are shown in grey. Where possible, a free English translation is provided underneath. See Appendix 7.1 for list of linguistic abbreviations.

7 For further information on changes in yawulyu today, see Morais et al. (in press).

8 Majardi are worn as a ceremonial sporran or apron by men and women. They are referred to in the early ethnographic literature as a “pubic tassel”. They are often the subject matter of yawulyu.

9 Given a tendency for verbs to occur in line-final position and to be in non-past forms, we suggest that panti-panti-rni “sewing” is the most likely speech equivalent.

10 Peggy Nampijinpa to Helen Napurrurla and Myfany Turpin, 16 August 2019 (audio file 20190816-01, to be deposited at AIATSIS).

11 Despite their similar sound systems, Kaytetye and Anmatyerr use different spelling systems. Throughout this chapter, the Anmatyerr spelling system based on that in Green (2008) is used for all Arandic words to simplify the comparison of Arandic words with Warlpiri.

12 In spoken Warlpiri, words of Arandic origin are pronounced with a final high vowel “i” or “u”, subject to vowel harmony conventions.

13 Meggitt (1966, 26–28) discusses the interpretation of song lines inherited from non-Warlpiri sources based on phonetic similarity, and the accompanying vagueness as to their literal meaning.

14 The tempo of this slow meter song is based on the minim, as this is closest duration to the clap beat that occurs in other slow meter verses. Bar lines correspond to both the grouping of two beats in a bar and the hemistich.

15 See Hale (1984) for a discussion of this phenomenon, which also contributes to the Warlpiri spoken lexicon.

16 Warlpiri mawulyarri and Warumungu makkulyarri are alternate words for ngajularri; in both languages, majardi also refers to a hairstring belt.

17 A yawulyu performance relating to the Pawu and Patirlirri areas includes one verse in this same slow meter, which is said to be associated with the Moon Dreaming (Turpin and Laughren 2013, 408).

18 See Fabricius (1998) for a wider discussion of reduplication patterns in Australian languages.

19 We discuss the partial poetic reduplication in Line A, jarlwa-nta jarlwa, below.

20 The Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary defines jarna-jarna as “songs sung by men during dance with witi poles performed prior to initiation”. Note that jarna-jarna also means “loads carried on the shoulder”, leading to further ambiguity of the verse (Laughren et al. 2022).

21 Warlpiri has grammatical reduplication that marks a non-default reading of a word; that is, it may indicate plurality, or repeated actions, or it may denote something similar to the denotation of the simple term (e.g., yalyu “blood”, yalyu-yalyu “red” (i.e., blood-like); kunjuru “smoke”, kunjuru-kunjuru “smoky, grey”).

22 There is no kuny-ngarni since preverbs must be minimally bimoraic (with two vowel morae); instead, there is kuuny-ngarni “suck” with a long vowel. Productive reduplication would give kuuny-kuuny-ngarni.

23 Cognate with Eastern Warlpiri and Warumungu pulyurrulyurru “red”.

24 This word for swamp may also be cognate with Warumungu mangkkuru “black soil plain”, which is also used for “sea”.

25 This word atywerrk has an optional initial vowel, either “e” or “a”, depending on the Arandic variety. Its pronunciation can have an initial rounded vowel, central vowel or no vowel.

26 Note that long vowels are subject to assonance patterns that affect every other repetition of a line in performance: that is, AABB, where a line and its repetition have a different vowel quality.

27 Pulyurrulyurru also means “red” in Eastern Warlpiri and Warumungu.

28 It may be significant that this song set also belongs to the same patricouple.

29 Singer Peggy Nampijinpa stated that “Lingka-jingkaja” refers to a place; however, no speech equivalents were given.

30 Some reflexes of ingkatye “foot” include Kaytetye angketye (Turpin and Ross 2012, 118) Anmatyerr ingka “foot” (Green 2008, 323) and ingkatyel-wem, which means to walk in someone’s footprint (Green 2008, 324) in Anmatyerr, Arrernte and Alyawarr.

31 The form ingkatyel “by foot” with consonant transfer is similarly in a verse of the Kaytetye Rain yawulyu (Turpin 2005, 238).

32 In Anmatyerr, akwerlp means “riverbank, creek bank; slope or top of a hill”; in Kaytetye and Alyawarr, it means “sandhill”.

33 The Warlpiri equivalent is warnirri and the Warumungu warnirr.

34 Peggy Nampijinpa identified litarrpitarrpi as the name of the rockhole referred to in Line A.

35 Another possible speech equivalent is elper “quickly” (K), one of the meanings given for this verse; another is anper (A), which has two meanings, “fantastic” and “beside”. It could also be Warumungu wirnppar(i/a) “break-fut/imperative”.

36 In Warlpiri phonotactics, the syllable -pa is added to a consonant-final word to make it vowel final; however, it may also be a partial triplication.

37 It may also be based on a reduplication (and partial reduplication) of iylerlkarr (Turpin and Ross 2012, 31) “white headband”: ilerlk iylerlkarr iylerlkarr (see Appendix 7.1).

38 The absence of Verse 9 is deliberate.

39 That is, observing reciprocal and respectful relations between people related through marriage.