8

Reanimating Ngajakula: Lander Warlpiri songs of connection and transformation

Ngajakula is a major public Warlpiri ceremonial complex associated with the Japangardi-Japanangka-Japaljarri-Jungarrayi patrimoiety. It complements the Jardiwanpa fire ceremony, which belongs to the opposite patrimoiety. Although Dreamings associated with Ngajakula continue to be sung, the ceremony has not been performed in its entirety for many years. In 2018, the Willowra community, concerned that detailed knowledge of the songs would be lost, decided to record a Ngajakula song cycle as part of the Lander Warlpiri Cultural Mapping Project.

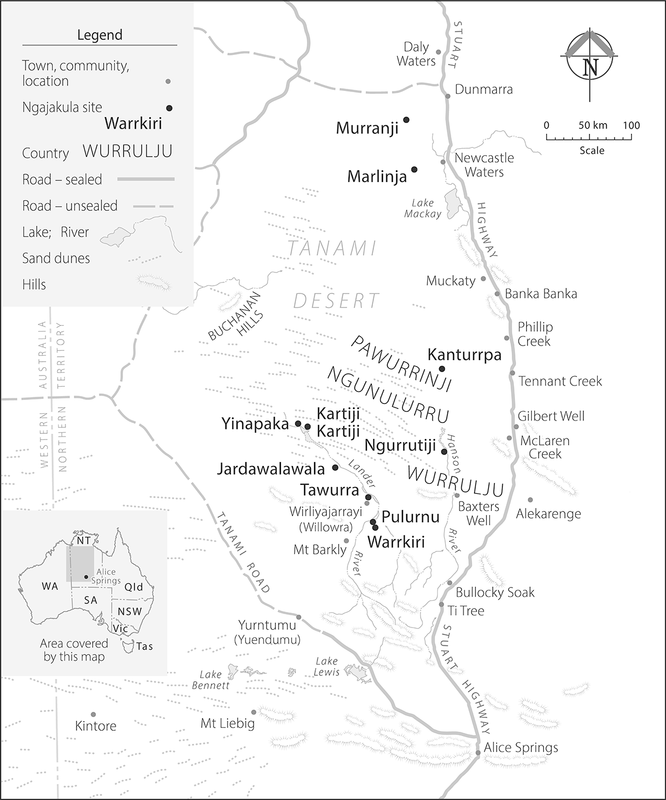

This chapter reflects on the initial phase of the Ngajakula project, when over 60 songs connected with the northern Lander region were recorded, and Elders Kumunjayi Jungarrayi Ryder1 and Teddy Jupurrula Long instructed younger people about Dreamings and sites associated with the ceremonial complex. While both men and women participated in the event and sang Ngajakula, our focus here is on the portion of the songline led by Jungarrayi through his Country to the north of Willowra, along the Lander River and east (see Figure 8.1). Our account builds on long-term collaboration between Warlpiri and Anmatyerr knowledge holders and non-Indigenous researchers who have worked on the Willowra mapping project. The remainder of the chapter is in five main parts.

Figure 8.1 Ngajakula sites along the Lander River, north of Willowra. Map by Brendy Thornley.

We begin by describing the context in which Ngajakula songs were recorded during the mapping project and introduce the Dreamings and associated Countries sung during the recording sessions. Then, drawing on historical sources, including written records and audiovisual material, in the second section, we discuss the findings of earlier ethnographic accounts of fire ceremonies, with a particular emphasis on Ngajakula. As we will see, ethnographers’ evolving understandings of the fire ceremonies are instructive, revealing dimensions of Ngajakula that warrant further examination throughout the chapter.

Our discussion of the history of fire ceremonies in the different Warlpiri communities highlights both differences and similarities. There is no single authoritative reading of fire ceremonies, and the variations reveal the significance of placing ceremonial performances (and their interpretations) within the appropriate historical and socio-geographic contexts. The Warlpiri song texts discussed in this chapter are both emplaced and relational, and our chapter attempts to show how issues of scale, sociality and ecology, and the interchangeability of human and non-human beings, inflect understandings of relationality (and its embeddedness) over time. Accordingly, in the third section, we discuss the history and significance of Ngajakula in Willowra people’s lives. We also consider the role Ngajakula has played historically in aligning relations between sociolinguistic groups and Countries through space and time.

The fourth section provides a condensed overview of the stories and songs of the north-eastern Ngajakula songline. The selected details offered at this point allow us to better appreciate the issues raised in the fifth section of the paper. There, we consider what it means to Willowra people to learn about the Ngajakula songs in the present and reflect on the implications of the ongoing documentation and revitalisation of Ngajakula songs and ceremony for the future.

The detailed information provided in these two sections is not primarily intended for the ethnographic archive. The collaborative authorship of this chapter reflects Willowra people’s desire to utilise different technologies and approaches for promoting knowledge of Lander Warlpiri cultural heritage and engaging younger generations. The recent performance of the Ngajakula fire ceremony, a public ceremony involving men and women at Willowra, together with recordings and observations presented in this chapter, form part of the Willowra community’s efforts to promote intergenerational transmission and understanding of the ceremony. This reflects the present volume’s broader themes of vitality, continuity and change.

Recording the Ngajakula songlines

Over the past few years, the Willowra community has undertaken a cultural mapping project, in the course of which Elders have instructed younger people about their Dreamings and sites while visiting their Country (Vaarzon-Morel and Kelly 2020). In the process, those collaborating on the project have mapped sites associated with ancestral actors involved in Ngajakula, Jardiwanpa and other ceremonial complexes. While locating sites within estates, Elders have emphasised the significance of ceremonial associations in linking different Dreamings and social groupings concerned with the reproduction of Warlpiri social life. In recognition of the fact that Ngajakula is no longer performed, it was decided to record a particular portion of the Ngajakula songline that relates to sites to the north and east of Willowra. As Jungarrayi commented, “we can sing first and later put places on the map for young fellas to learn”.2 To date, we have completed the first phase of the project, which involved the recording of Jungarrayi’s Ngajakula songline.

In preparation for the recording session, the ceremonial ground at Willowra was swept, firewood gathered and a windbreak erected. Jungarrayi then proceeded to carve clapsticks to beat the rhythm of the verses. Meanwhile, a large canvas map of sites visited in the Lander region was hung from a Toyota parked near the ceremony ground (see Figures 8.2 and 8.3). With women gathered a short distance away, Jungarrayi (kirda for Ngajakula) and Jupurrurla (his kurdungurlu) introduced the session by describing the importance of the project and providing an overview of Countries and key Dreamings that crisscross the Lander region. They then traced the path of Ngajakula along a north–south route as it linked different jukurrpa (Dreamings) and Countries and intersected two Jardiwanpa lines.

Figure 8.2 Kurdungurlu Teddy Jupurrurla Long instructing younger people about jukurrpa places (Willowra, 2018). To the left is Dwayne Ross. Photo by Petronella Vaarzon-Morel.

Figure 8.3 Preparing to record Ngajakula song cycle (Willowra, 2018). Photo by Petronella Vaarzon-Morel.

In discussing Ngajakula, they stressed that they celebrate the jukurrpa for Country over which they hold responsibility as kirda and kurdungurlu and that they “use proper ceremony for our area”. As Jungarrayi stressed: “I can’t touch that southern side [Ngaliya Warlpiri Ngajakula and Jardiwanpa songlines], only Purluwanti and Willowra and Ngunulurru area sites.” Further distinguishing his songline from the southern one, Jungarrayi contrasted the vocal style of each, pointing out that he sang Ngajakula “light and high” not “pirrjirdi, heavy like Yuendumu mob south”.

The series of Ngajakula songs that were then sung and recorded focused on encounters between ancestral beings in the section of the Ngajakula songlines that connects Marlinja (near Newcastle Waters), Ngunulurru (sandhill Country between the Lander and Hanson floodouts) and Yinapaka (Lake Surprise). The Dreamings celebrated in the songs were Purdujurru “Brush-Tailed Bettong” (Bettongia penicillata), Panungkarla “Ramsay’s Python” (Aspidites ramsayi), Milwayi “Central Bandy-Bandy, Common Bandy-Bandy” (Vermicella vermiformis), Ngapangarna “Water bird” (also referred to as kalwa – the generic Warlpiri gloss for “Heron, egret”), Jurrurlujurru “Mulga Parrot (?)”,3 Jarnpa (“malevolent being”), Jurlarda (“Sugarbag”, i.e., “bush honey”), Purluwanti “Eastern Barn Owl” (Tyto javanica), Jutiya “Desert Death Adder” (Acanthophis pyrrhus)4 and Jinjiya (tree species said to be “like bloodwood”).5

Although the Ngajakula songline also passes through Countries and celebrates Dreamings associated with the J/Napangardi and J/Napanangka semi-moiety, their songs were not sung during our recording session. We explore the recorded songs later in this chapter. In the next section, we discuss earlier ethnographic accounts of Ngajakula to contextualise our material.

The written history of Ngajakula: Anthropological accounts

Over a hundred years ago, ethnographers Baldwin Spencer and Francis J. Gillen (1904) wrote that Warumungu, Jingili and Wakaya tribes possessed an elaborate fire ceremony that involved both male and female participants. The ethnographers were fortunate to witness a fire ceremony performed at Tennant Creek between 24 August and 7 September 1901. They noted that it was called Nathagura in Warumungu and was owned by the Uluuru moiety but controlled by Kingilli, the opposite moiety. The Kingilli moiety owned the Thaduwan ceremony, which in turn was controlled by the Uluuru moiety (Spencer and Gillen 1904, 376). As Peterson (1970) observed, the names of these two ceremonies – Nathagura and Thaduwan – are cognate, respectively, with the Warlpiri Ngajakula and Jardiwanpa. These ceremonies are owned by paternally related Warlpiri patrimoieties, which are equivalent to those of the Warumungu (i.e., Japangardi-Japanangka-Jungarrayi-Japaljarri for Ngajakula and Jupurrurla-Jakamarra-Jangala-Jampijinpa for Jardiwanpa).

According to Spencer and Gillen, the old men told them that the purpose of the ceremony was to resolve old quarrels (1904, 387). It was, reflected the ethnographers, “a method of settling accounts up to date and starting with a clean page – everything in the nature of a dispute which occurred before this is completely blotted out and forgotten. It may, perhaps, be best described as a form of purification by fire” (Spencer and Gillen 1904, 387). Notably, the central Dreaming celebrated in the Warumungu ceremony was recorded by Spencer and Gillen as Tjudia (Jutiya in standardised Warlpiri orthography), the Death Adder. As we will see later, Jutiya Dreaming is associated with Warlpiri Countries Ngunulurru and the neighbouring Kanturrpa, both of which lie east of the Lander River and west of Tennant Creek.6

In August 1967, several decades after Spencer and Gillen witnessed the Warumungu fire ceremony, Nicolas Peterson and Roger Sandall filmed a Warlpiri performance of the fire ceremony at Yuendumu. The following year, Peterson witnessed the final part of another such ceremony at the settlement (1970, 203). Then, in 1970, he published a trailblazing analysis of the 1967 ceremony referred to as Buluwandi (Purluwanti), said to be one of “three versions” of the fire ceremony, the other two being Djariwanba ( Jardiwanpa) and Ngadjagula (Ngajakula). The mythology of Jardiwanpa concerns “the travels of Yaripiri, a snake of the djuburula and djagamara subsections, who went from Winbago (Blanche Tower) to an unknown destination north of Hooker Creek” (Peterson 1970, 201; see also Mountford 1968). Over the years, this songline has received much ethnographic attention (Curran 2019; Dussart 2000; Gallagher et al. 2014; Langton 1993; Laughren et al. 2016; Michaels 1986; Morton 2011)7 and will not be discussed further here except in passing.

To return to Ngajakula, Peterson identified the mythological focus of the ritual as being concerned with “the travels of a rat kangaroo, mala, from Mowerung [Mawurrungu], south of Yuendumu, to Walaya near Hooker Creek” (1970, 201). At the time, he stated that the mythology of what he thought was a third ceremony, Buluwandi (Purluwanti),8 featured “a bird and a snake resident at Inabaga [Yinapaka] on the Lander River flood-out” (1970, 201).

A decade after filming the 1967 ceremony, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies released an edited film of the original footage (Sandall, Peterson and McKenzie 1977), in which Peterson refers to the Purluwanti ritual as Ngajakula.9 As we discuss later, although there are connections between the two Ngajakula ceremonies, which are centred (respectively) on the ancestral beings Mala and Purluwanti, Elders at Willowra regard the two songlines as different. From an eastern Warlpiri perspective, the former is said to have travelled from the Arabana region in northern South Australia via Uluru, thence to Mawurrungu and north, whereas the songline associated with Purluwanti originates north of Newcastle Waters and travels south.

In relation to the Purluwanti stories, Peterson noted that, as Purluwanti travelled “he observed ancestral men holding a fire ceremony and descended to participate in parts of it. At a number of stages he transformed himself into various other forms, a snake Banangula [Panungkarla], an owl, a cockatoo and a Gurrgurrba [Kurrakurraja] bird” (1970, 202). Then, at the end of the ceremony, Purluwanti returned to Yinapaka. Peterson observed that although Purluwanti belonged to the Japaljarri and Jungarrayi semi-moiety, if Japangardi and Japanangka men from the other semi-moiety “wished to emphasise their role they introduce song cycles, emblems and mythology that are directly associated with their subsection” (1970, 202).

Regarding the purpose behind the Ngajakula and Jardiwanpa ceremonies, Peterson stated that Warlpiri “offer the same explanation for holding the ceremonies today as the Warramunga gave to Spencer and Gillen in 1901” (1970, 200): that is, to resolve quarrels. However, he also noted that the ceremony is concerned with not just any quarrel but aggression arising from arguments about “rights to and over women” (1970, 211). During the ceremony, some of the workers (kurdungurlu) attack the owners (kirda) with burning branches, showering sparks upon them. Explaining the reason for the aggression of the workers towards the owners of the ceremony, Peterson suggested that it is because the owners have been bestowing their daughters without respecting the rights of matrikin: that is, the patrikin have failed to acknowledge the rights of the workers in arranging their nieces’ marriages (1970, 213). As Peterson demonstrated, this explanation rests on a model of sisters exchanging daughters, upon which anthropologist John Morton subsequently elaborated.

Building on Peterson’s account, Morton re-analysed the symbolism of Warlpiri fire ceremonies, explaining why “conflicts conditioned by bestowal arrangements should be mediated by fire” (2011, 17). Morton observed that, although fire Dreamings are not celebrated in Warlpiri fire ceremonies, fire is not only central to the ceremonies “but also central to Aboriginal relationships as a whole” (2011, 17). In a brilliant, if complex analysis, he shows how fire is implicated symbolically in “splitting the atom of kinship” to create relations of affinity: that is, in-law relations. Drawing on Lévi-Strauss, Morton concluded that the atom is split along a generational axis “by ‘integrating the opposition between self and others’ and making ‘individuals into partners’ across a gendered moiety divide” (2011, 29). Thus, “while the singular atom is split, plural atoms are joined, so that unity lost (chaos) is also unity regained (order)” (2011, 29). Of relevance to this current chapter is Morton’s insight that fire has both “masculine and feminine elements” (2011, 27). Although Morton does not explore its implications in relation to the roles of female participants in the fire ceremony, Françoise Dussart (2000) and Georgia Curran (2019) have deepened our understanding of this dimension of the ceremony.

Dussart observed that, beyond the explanation of the ceremonies being performed to resolve conflicts caused by the violation of marital relations and bestowals, “these cycles establish alliances between widows of both genders with future spouses” (2000, 78).10 Further, they encourage the maturation of the individual. Dussart highlighted the mentoring role of the maternal uncle in the ceremony and the importance of specific kinship relations in structuring lines of attack with fire and protection from assault by fire during the ceremony (2000, 80). Following Peterson’s lead, Dussart positioned Jardiwanpa, Kura-kurra, Ngajakula and Purluwanti as distinct ceremonial cycles, stating that “Ngajikula coordinate[s] the managers and owners of the Rat Kangaroo Dreaming (Marlu [Mala] jukurrpa)”, while “Kura-kurra coordinate the activities of the reciprocally allied kin associated with the Budgerigar Dreaming (Ngatijirri jukurrpa), Bush Onion Dreaming (Janmarda jukurrpa), and Brown Bird Dreaming (Jalalapinypinypa jukurrpa)”. Distinguishing Purluwanti from Ngajakula, Dussart relates that the former is concerned with “conflict resolution and marital realliance among the kirda and kurdungurlu of Dreamings for three Ancestral beings: the Bookbook Owl (Kurrkurrpa), Green Parrot (Jarrurlu-Jarrurlu), and a Snake (Warna)” (2000, 79).

The accounts discussed so far highlight different aspects of the songlines. While Dussart recorded different Dreamings associated with the four Fire song cycles, Spencer and Gillen (1904), Peterson (1970) and Wild (1975, 134) observed that the focus of fire ceremonies is a single Dreaming. Thus, Peterson reported that, although other ancestral figures are associated with Purluwanti, the Owl transformed himself into these other figures during his travels (1970, 202).

Nonetheless, in a recent paper on the history of fire ceremonies at Yuendumu, Curran presented a different interpretation. She affirmed that Jardiwanpa differs from other Warlpiri ceremonies “focused centrally on the journey of one particular ancestral being” (2019, 22). Unlike these ceremonies, the fire ceremonies “emphasise several different Dreaming itineraries, owned by different Warlpiri groups and therefore implicate more people” (2019, 21–22).11 Integrating these different interpretations, Laughren et al. (2016, 3) observed that, in relation to Jardiwanpa, different Dreaming ancestors followed the paths of Yarripiri (“Inland Taipan”), the central figure of the ceremony. Importantly, these Jardiwanpa ancestors did not celebrate all the Dreamings whose tracks they crossed – only those with whom they had in-law relations, thus “emphasising a key concern of the Jardiwanpa ceremony was marriage relations or jurdalja” (2016, 4).

Drawing on Dussart (2000), Curran surmised that the difference between Jardiwanpa and Warlpiri site-specific ceremonies may be attributable to the north-eastern origins of Jardiwanpa. The provenance of Warlpiri fire ceremonies is intriguing, and we will have more to say on the topic later in this chapter. Here, we note that Dussart recorded being told that the Jardiwanpa ceremony at Yuendumu dated from the first decades of the 20th century, when it was performed by Mudburra “in an exchange event between Warlpiri, Mudbura and Warrumungu” (2000, 32).

On the other hand, Peterson contrasted the then-recent introduction of Purluwanti to Yuendumu with the more longstanding traditions of Jardiwanpa associated with Yarripiri and the Ngajakula line associated with the site of Mawurrungu. Specifically, he remarked that, although Purluwanti was performed regularly at Lajamanu (Hooker Creek), “unlike Djariwanba and Ngadjagula it is only of recent standing in its present form at Yuendumu” (1970, 201). By this, he meant that “the current style of performance” was recent, but not the ceremony (1970, 214).

What is clear from our discussion so far is that while there are similarities and overlaps in the various ethnographic accounts of Warlpiri fire ceremonies, there are also differences. Variations in the stories undoubtedly reflect the Dreamings owned by kirda participating in the rituals, as Curran has shown regarding Jardiwanpa held at Yuendumu, but historical changes may also influence the ceremonies themselves and people’s interpretations of their meaning. Reflecting on the history of fire ceremonies, Curran (2019) suggested that the intensification of social life in settlements such as Lajamanu and Yuendumu led to an increase in large-scale ceremonies such as Jardiwanpa, Kurdiji and cult ceremonies that have a “clear social purpose”. In relation to the latter, she quoted the late Harry Jakamarra Nelson, who told her that “a primary reason for holding Jardiwanpa was to open up the restrictions on remarriage for widows of deceased men who were associated with the Jardiwanpa Dreaming ancestors” (2019, 22).12

Nonetheless, according to Curran, neither the finishing up of widowhood nor conflict resolution remains central to Yuendumu people’s understandings of fire ceremonies today. Moreover, as a result of people’s declining knowledge of Dreamings and associated sites and the influence of monetary payments received for the staging of Jardiwanpa to be filmed for an intercultural audience, the relevance of the ceremonies has changed (Curran 2019, 29). Hence, she argued that “this ritual has lost something of its emergent nature as a social conflict resolution ceremony” (2019, 33). At the same time, despite the changing meaning of Jardiwanpa in people’s lives, the fixed-filmic representations of past Jardiwanpa have come to signify Warlpiri tradition for the wider public.

In this section, we have tracked various ethnographic analyses of Ngajakula and Jardiwanpa. This survey of our interlocutors’ accounts of the rituals makes it clear that, with the exception of Peterson’s work, most have been Yuendumu-centred and are concerned with the Jardiwanpa songline associated with the travels of the Yarripiri ancestor through southern Warlpiri Country. In this next section, we present a view from the Lander and the north-east, one centred on Ngajakula and the travels of the ancestral beings Purluwanti and Kurrakurraja. Drawing on discussions of the song performance with Jupurrula Long, Jungarrayi Ryder and others in the course of the Willowra cultural mapping project and on Vaarzon-Morel’s earlier field research, we discuss the history of Ngajakula performances at Willowra and note the differences from their evolution at Yuendumu.

Histories of Ngajakula in the Lander Warlpiri region

The written record of Ngajakula and Jardiwanpa performances at Willowra dates to 1976, when two of the authors of this chapter (Wafer and Vaarzon-Morel), who were schoolteachers at the time, were invited to participate in the ceremonies. However, fire ceremonies had been performed on earlier occasions at Willowra and by Willowra residents at other places. Thus, Curran noted that in the 1970s, when Mary Laughren and Nicolas Peterson lived at Yuendumu, “Ngajakula was held more often than Jardiwanpa as the eastern Warlpiri from Willowra were then dominant in ceremonial activity” (2019, 22).

Still earlier, as Peterson indicated, Purluwanti was performed regularly at Lajamanu during the 1960s (1970, 210). Living there at the time were some older traditional owners of Yinapaka and Countries to the north and east who knew the jukurrpa landscape intimately. According to Elder Jerry Jangala Patrick, with the passing of these Elders, Lajamanu ritual life became oriented to Ngaliya Warlpiri and Western Desert traditions, and Purluwanti ceased to be performed at the settlement.13

Fire ceremonies are ideally performed after the beginning of August, when Napaljarri-warnu, the Pleiades constellation associated with the Ancestral Dancing Women,14 rises from the horizon in the night sky and ushers in warmer weather.15 Vaarzon-Morel has noted that fire performances were held around this time at Willowra during 1976, 1977, 1979, 1980, 1987 and 1988. Following the death of a Jungarrayi leader of Ngajakula, the ceremony was closed for a period and appears not to have been held again until the early 1990s.16

Ngajakula rituals typically began at dusk, with people gathering on the ritual ground across the Lander River, where, for a period of two weeks or more, verses from the Ngajakula repertory were sung. Clapping boomerangs, men sat separately from but within earshot of women, who sang yawulyu associated with Ngajakula and danced. Typically, the owners sat facing north, the direction of travel of the ancestral beings (see also Peterson 1970; Wild 1977, 17).

It was sometimes the case that the Ngajakula song cycle was sung without culminating in a full-scale fire ceremony, which required the involvement of male and female kirda and kurdungurlu living at Alekarenge,17 Tennant Creek and elsewhere. However, if the ceremony had progressed to the stage where a decorated pole was planted in the ceremony ground, widows’ mourning rituals might still be undertaken, with widows and helpers applying yellow ochre to their hair and bodies and other ritual actions. The mothers of widows would place blankets and damper at the foot of the ritual pole to be exchanged with the maternal uncle of the deceased. Thereafter, discussions may be held between the widow, her uncle and the younger brother of the widow’s deceased husband concerning custodianship of her children. However, the end of a widow’s period of seclusion, which enabled remarriage, was not regarded as complete until the owners of the ceremony (the patricouple of the widows) were symbolically burned with fire.18 What was clear is that the ceremony related to themes of death, conflict resolution and revitalisation.

The unfolding of fire ceremonies was generally a complex affair involving much intricate coordination, reflecting a continuing history of exchange among different language groups. Thus, in March 1987, Willowra people discussed introducing Ngajakula to Pintupi people at Kintore. At the time, Willowra people were attending an initiation ceremony at Kunayungku outstation near Tennant Creek, during which women were painted with yawulyu designs for Yinapaka, Ngunulurru, Ngarnalkurru and other Countries whose Dreamings are celebrated in Ngajakula. The event emphasised ritual ties among Lander and other eastern Warlpiri Countries, including Kanturrpa, Miyikampi, Ngurratiji, Pawurrinji and Wurrulju.

The plan was to meet up at Yuendumu for a ritual exchange between Warlpiri and Pintupi; in April, some Elders from Willowra travelled to Yuendumu to begin preparations. However, as Kintore people had still not arrived by May, they returned to Willowra. Then, in August, a Jardiwanpa ceremony was held at Willowra. Like the earlier ceremony at Kunayungku, it involved weeks of singing and the widows’ ritual but was not completed because the spectacular ritual involving the burning of owners did not happen. It was then planned to begin Ngajakula again after a few weeks’ break, when it was hoped that Kintore people would arrive to stage the Ngajakula fire ceremony, followed by the conclusion of Jardiwanpa. After waiting some weeks, in November, Willowra people brought the Ngajakula ceremony to Kintore for a ceremony involving people from Kiwirrkura, Kintore and Amunturrngu (Mount Liebig).

The men gave Vaarzon-Morel various reasons for undertaking the ritual exchange, including that “Kintore mob really wanted it”19 and that, unlike Yuendumu, where promised marriages were no longer undertaken and young people “married any way”, Kintore was a place of “strong law” like Willowra, where people knew their Dreamings. As one Napaljarri expressed it, “right way marriage comes from knowing Dreamings and learning about country”.20 While it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine the ceremonial exchange, we note that Engineer Jack Japaljarri and other Elders from Alekarenge accompanied Willowra men and women to Kintore where the full-scale fire ceremony was performed, for which Warlpiri kirda and kurdungurlu were paid with money and blankets. The leaders of the ceremony on this occasion were Japangardi and Japanangka affiliated with Ngarnalkurru Country. Reflecting on the event some years later in 1990, Jungarrayi commented: “they got that Purluwanti now at Kintore: we connect together, Willowra, Kintore and Mount Liebig”.

Establishing new ceremonies in a place enables Elders from that place to link the songlines to yet other places. Linking songlines across different cultural landscapes may also facilitate the exchange of new ceremonies.21 In fact, the two processes are intimately connected.

Early Ngajakula exchanges

Although the jukurrpa22 that feature in Ngajakula are said to have existed in place tarnngaku (“forever”), it is clear the ceremony itself has long moved across the landscape.23 In the 1990s, the late C. Jampijinpa Martin told Vaarzon-Morel that he first saw Ngajakula performed at Warrabri settlement shortly after people were moved there from Phillip Creek and Bullocky Soak24 and that Engineer Jack Japaljarri was the ceremonial leader. Teddy Jupurrula also recalled attending Ngajakula at Warrabri, stating that “we went for big training from Willowra” with the “old people” from Newcastle Waters, Muckaty and Banka Banka who brought the ceremony to the settlement. The Elders included Pharlap Dixon Japaljarri (Jalyirri) and Andy Japaljarri from Elliott region who, along with Engineer Jack, were considered ceremonial leaders.

Then, in the late 1960s, Pharlap visited Willowra on a government works program and helped stage a Ngajakula performance involving Jimmy Jungarrayi Kitson, Long Mick Jungarrayi, Long Paddy Japaljarri, Engineer Jack Japaljarri, Jimmy Newcastle Japaljarri and Chicken Jack Japaljarri.25 Jupurrurla recalled that “we used to sing all night, no sleep for three and a half weeks, all day and night, before next morning finish up”.26 He described old Wirtilki Japanangka from Ngarnalkurru as a senior Willowra leader, noting that Johnny Martin Jampijinpa was “the right kurdungurlu for Ngajakula” while Johnny Kitson was “Purluwanti himself”. Sadly, these people have all passed away.

Prior to this event, Jungarrayi and other Willowra people had worked on the cattle stations in the north, where they mixed with Jingili, Mudburra and Warlmanpa people. Jupurrurla recalled that while Willowra people figured out how they were related to others through the skin system, they were perplexed by ngurlu27 – that is, Mudburra matrilineal social totemism. In this system, a person cannot marry someone of the same ngurlu, regardless of whether they are members of subsections that would be otherwise marriageable. As Jupurrurla explained it, a man might think a woman was the right one for him, but she might say “sorry [ngurlu way] I’m your mother”.

It is apparent from discussions with Elders that the earlier days of intracultural gatherings were marked by an excess of tension sparked by arguments between local and visiting men over women.28 Ngajakula provided a way to create unity. Thus, Jungarrayi described one occasion when they were camped near Elliott and participated in a Ngajakula performance led by local Japaljarri and Jungarrayi and involving Japanangka and Japangardi from Country on Muckaty station.29 Jupurrurla recalled people saying to each other, “we thought, we are all warlalja [countrymen]30 and we need to finish up, say sorry, start fresh”. Jupurrurla recounted that large quantities of material items including money, blankets, flour, tea, sugar, and kangaroo and emu meat were exchanged during the ceremony.

It is clear from our discussion that Ngajakula is an incorporative songline. However, it differs from initiation and other ceremonies that have dramatically expanded in recent years (Peterson 2000). These stress inclusiveness and represent a move away from “site-based ceremonies” (Peterson 2000, 213) and “rituals based on specific knowledge of Dreamings” (Curran 2011, 48). While Ngajakula worked to create a sense of relatedness and community among people from disparate language and cultural groups, it did so through songlines that connect Dreamings and places associated with particular estates, aligning marriage relations among people from the estates that stand in a jurdalja (“in-law”) relationship to each other.31

Stories and songs associated with north-eastern Ngajakula songline

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to list all the Ngajakula sites recorded in the songs and to analyse the relevant stories in detail, so here we limit ourselves to an overview of Dreaming stories and songs central to the Lander Ngajakula.

From the perspective of Willowra people, their Ngajakula starts at Murranji and travels through Jardawalawala, Pulurnu, Kartiji-Kartiji, Ngunulurru, Kanturrpa, Ngurrutiji and Ngarnalkurru, among other places, and south to Wirliyajarrayi (Willowra) area. Ngajakula is said to “change colours” and “changeover” (switch, transform and exchange) as the songline travels through different Countries. As noted previously, Purluwanti, “Eastern Barn Owl” (Tyto javanica) is one of the two main ancestral beings associated with the north-eastern Ngajakula, the other being Kurrakurraja, the Channel-Billed Cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae), commonly referred to as “Storm Bird”.32

Ngajakula, unlike Jardiwanpa, is concerned with waterbirds, which Purluwanti “keeps singing” to bring rain. Kurrakurraja is a long-distance traveller who brings rain from the far north and creates swamps in the sandhill Country east of Yinapaka. Willowra Elders trace its path through Jingili, Mudburra and Warlmanpa territories, noting that a branch also travelled through the Warumungu region. A migratory bird, Kurrakurraja lays its eggs only in the nests of other birds and is the classic troublemaker. The Kurrakurraja Dreaming is primarily associated with Japangardi and Japanangka subsections, whereas Purluwanti is associated with Japaljarri and Jungarrayi.

Purluwanti and Kurrakurraja Dreamings are regarded as malirlangu, or jurdalja,33 travelling “side by side”.34 The two Dreamings unite the Countries that they visit. Thus, despite being associated with different subsections in the same moiety, they are considered to be jintangka, “in one”. Countries associated with this patrimoiety are referred to as ngurrayatujumparra. Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the Kurrakurraja stories further, we note that Kurrakurraja flies from Murranji to Yinapaka, then to a site in Ngarnalkurru Country, before returning to Ngunulurru and Murranji.

Purluwanti travels from Ngurruwaji to Murranji and Marlinja (near Newcastle Waters Homestead) before returning to Yinapaka, thence to sites such as Tawurra (in Ngarnalkurru area), Warrkiri near Willowra and back to Yinapaka. We noted earlier Peterson’s observation that as Purluwanti travelled, “he observed ancestral men holding a fire ceremony and descended to participate in parts of it” (1970, 202). Kurrakurraja is similar. In describing the mirroring of everyday life in jukurrpa cosmology, Jungarrayi remarked that the ancestral beings “get together and finish ’em up. Same like yapa, jukurrpa does the same way again. They all finish ’em together in ceremony. They all get satisfied. They get [suffer] pain and it’s finished. The troublemakers then went back to his country.” Yinapaka is both a main place for Purluwanti and something of a crossroad, a “main centre” for Countries in the ngurrayatujumparra relationship, where certain Dreamings change over from one patricouple to the other in the same moiety.

The 2018 performance of Ngajakula songs at Willowra

The north-eastern Ngajakula song sets we recorded in 2018 were performed over two days (27–28 June), each divided into morning and afternoon sessions. The final video, compiled and edited to remove extraneous material, includes two hours of singing, interspersed with an additional half-hour of commentary (mostly in Warlpiri, with some English).35 In geographical terms, the songs were concerned principally with two sets of sites located on longitudinally opposite sides of the sandhill Country of the northern Tanami Desert and with the relationship between them.

The southern sites, such as Kartiji-Kartiji and Ngunulurru, are situated between (and a little to the north of) the termini of two river systems: the Lander floodout at Lake Surprise (Yinapaka) and the Hanson floodout near Emu Bore (Yankirri-kurlangu). The northern sites are located in the region around Newcastle Waters and Murranji, with a focus on the site of Marlinja. Note, however, that the songs sung at Willowra in 2018 went only “halfway” to Marlinja. North of the site of Kulunganjalpa (“Buchanan Hills”),36 they are regarded as belonging to others.

The performance was divided into seven song sets, with breaks between them: four on 27 June 2018 and three on 28 June. In the overview given here, the song sets are numbered 1–7, with the relevant site names given first and the Dreamings following in brackets.

- Kartiji-kartiji to Kulunganjalpa (Purdujurru, Panungkarla, Milwayi)

- Kulumpujuju to Ngunulurru; Parnparri (Ngapangarna, Jurrurlujurru)

- Ngunulurru (Ngapangarna, Jurlarda)

- Ngunulurru (Jurlarda)

- Murranji to Yinapaka to Ngunulurru (Purluwanti)

- Kulunganjalpa, en route to Marlinja (Panungkarla, Milwayi)

- Ngunulurru (Jutiya, Jinjiya, Jurlarda)

Sets 1 and 6 pertain to the route between Kartiji-Kartiji and Kulunganjalpa, which is said to be “halfway” between Kartiji-Kartiji (near Lake Surprise) and Marlinja (near Newcastle Waters). Sets 2–5 and 7 all focus on the site (and “Country”) known as Ngunulurru, in the sandhills between Lake Surprise and the Hanson floodout.

It is noteworthy that the “mobile” Dreamings from the two groups of songs travel in different directions, using different ambulatory modes. In sets 1 and 6, Panungkarla slithers overland from south to north; in sets 3 and 4, Jurlarda comes on tiny wings from further south, via Kanturrpa, to Ngunulurru.37 By contrast, in set 5, Purluwanti flies in the opposite direction, from north to south; in set 2, Ngapangarna takes to the air at Kulumpujuju, west of Willowra, and flies eastwards to Ngunulurru. (Most of the other Dreamings in both sets are localised.)

The songs in sets 1 and 6 clearly belong to a single narrative complex. Part of the evidence is that the only time a song was repeated between sets was when the first song in set 1 was sung again at the beginning of set 6. Repetitions were otherwise infrequent and occurred only within a set (twice in set 1, once in set 5, twice in set 6 and once in set 7).

The songs in the other four sets all pertain, as mentioned, to Ngunulurru. However, whereas the movements of Panungkarla give coherence to the narrative of sets 1 and 6, there is no single Dreaming that performs the same function for the Ngunulurru songs. Instead, there are three mobile Dreamings (Ngapangarna, Purluwanti and Jurlarda) associated with different, overlapping narrative lines. The following synopsis is thus divided into four narrative complexes, based on the travels of Panungkarla (Aspidites ramsayi “Ramsay’s Python”38), Ngapangarna “Water Bird”,39 Purluwanti “Eastern Barn Owl” (Tyto javanica) and Jurlarda “Sugarbag”.40

The travels of Panungkarla (song sets 1 and 6)

Kartiji-Kartiji is the home of Purdujurru “Brush-Tailed Bettong” (Bettongia penicillata), who occupies himself with digging for roots of the wayipi “Tar Vine” (Boerhavia diffusa). Panungkarla arrives on the scene hunting for Jungunypa “Spinifex Hopping-Mouse” (Notomys alexis), but the Mouse keeps getting away. Panungkarla gets sweaty from the chase and gives up in hunger and frustration. It is already dark when he gets back to his camp. During the night, he turns into an Emu.

The next morning, when he wakes up as a Snake again, he hurries on his way, still hungry, towards Marlinja. But, about halfway, at Kulunganjalpa, he meets Milwayi41 “Central Bandy-Bandy, Common Bandy-Bandy” (Vermicella vermiformis), and they have an argument. They draw their knives and get ready for a fight,42 jumping round and challenging each other. But they are too scared to stab each other, so they decide to continue on their way.

Commentary: Jungarrayi, the lead singer, said he knows the songs for the section of the songline that continues on to Marlinja, but he stops at Kulunganjalpa. North of there, the songs belong to some now-deceased Warlmanpa people.

The travels of Ngapangarna (song sets 2 and 3)

Ngapangarna flies from Kulumpujuju to Ngunulurru. An associated Dreaming is Jurrurlujurru “Mulga Parrot”, whose home is a site called Parnparri (near Emu Bore). At Ngunulurru, Ngapangarna’s path crosses that of Jurlarda.

The travels of Purluwanti (song set 5)

Purluwanti flies from Murranji Country to Yinapaka, then across the plain to Ngunulurru. It does not land but is just looking around, “like a satellite” (as Jupurrula put it). Then it flies back to Murranji.

The travels of Jurlarda (song sets 3, 4 and 7)

Jurlarda comes from the south in the form of Minikiyi “Honey Bees”. From their nest inside a tree at Ngunulurru, they try to get out of the entrance hole (called wilpiri), but the lump of honeycomb (“Sugarbag”) they have produced is too big, and the hole is blocked by sand. One Bee manages to get through, but the sun dries him out, and he falls to the ground. Later, a Bee comes back in through the “eye” (milpa – a synonym for wilpiri).

Associated Dreamings include a bloodwood-like tree called Jinjiya (also known as Warlamarti) and its flower, called Yurrkulju, as well a snake called Jutiya “Desert Death Adder” (Acanthophis pyrrhus). The Jutiya changes colour, from red to orange to yellow, then turns itself into a human being.

Linguistic and musical features of the songs

At this stage of the revitalisation process, we have transcribed 12 of the approximately 60 songs that were sung at Willowra in 2018.43 Transcription of the texts is complicated by the fact that many of the songs are in “song language” rather than standard Warlpiri. The phonology is consistent with Warlpiri, and some morphemes and phrases are readily recognisable. For example, the lines Jutiya warna-jarrayi / Jutiya yapa-jarrayi that occur in the second song of set 7 translate without difficulty as “Jutiya turned into a snake / Jutiya turned into a man”. However, many lexemes in the recorded songs are not found in Warlpiri – at least, as the language is recorded in the monumental Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary produced by Laughren et al. (2022).

Further research may reveal that some of the “song language” derives from one or more languages spoken to the north of Warlpiri. In light of the historical evidence suggesting that Ngajakula was brought to Warlpiri Country from the north, the most likely source languages are Warlmanpa, Mudburra, Jingulu, Gurindji and Warumungu. Alternatively, the songs may have originated even further away or even been received in “spirit language”.44

On the surface, the musical features of the songs have much in common with those sketched out in previous research on Warlpiri men’s singing practices (e.g., Wild 1975, 1977, 1979, 1984, 1987). However, there is a marked deficit of transcriptions of Warlpiri men’s songs – in contrast with a recent relative abundance of studies of Warlpiri women’s songs – which makes comparison difficult. Further work is needed, and we are hoping to produce a more detailed account of the texts and music of the north-eastern Ngajakula cycle in a future publication.

Learning about the Ngajakula songs in the present

Referring to the southern Ngajakula songline, Liam Campbell reported that [the late] “Jakamarra Nelson, who has sung the Mawurrungu songs as a ceremonial leader, said it was not until late in his life, when he finally went to Mawurrungu, that he understood them” (2006, 29). A person’s understanding of the deeper metaphorical meaning of songs and related rituals is clearly based on an embodied knowledge of places – but not only on that. It also depends on their seniority and the right to speak for the places and associated songs as either kirda or kurdungurlu.

Even in this scenario from earlier times, learning was an ongoing and patchy process45 influenced by context (political and historical), social relatedness and opportunities to visit Country. With the increasingly mobile and diasporic nature of the Willowra community and the passing of Elders, opportunities for learning about Ngajakula have declined. Discussions of past Ngajakula events can evoke memories of lost kin and relationships. As Jupurrurla commented regarding the recording we made in 2018, “when old women see this video they may get sad and very emotional, remembering the old people who used to sing the ceremony”. However, it is also by teaching young people about the Ngajakula songlines that connections between Countries can be revitalised.

The process of learning about Ngajakula is complicated further by its changing pertinence. It is not so much that people no longer know the sites mentioned in fire ceremony songs, as Curran (2019) has suggested is the case with Jardiwanpa at Yuendumu, but rather that promised marriages no longer occur and jurdalja alliances between proximate Countries have substantially diminished. Although most marriages among the younger generation are still contracted “right way” in terms of subsection affiliations, they are no longer moored in Country in the same way as in the past.

By teaching the younger generations about the eastern Warlpiri Ngajakula songline, Jungarrayi and Jupurrurla hoped to promote greater understanding of the historically complex and interdependent nature of relationhips between Countries in the wider Willowra region. Specifically, the travels and activities of ancestral beings associated with the songlines articulate relations of both exchange and cooperation among Countries in the ngurrayatujumparra relationship, as well as their reciprocal relationships with kurdungurlu from the opposite moiety. Although not detailed in this chapter, they also reveal culturally significant connections among plants, animals and topography of the Countries with which the songline is concerned.

Conclusion

In his analysis of Jardiwanpa, Morton convincingly shows how fire mediates social relations by splitting the atom of kinship to create affinal relations. However, he does not directly address why the fire ceremonies take the form they do, involving long-distance songlines.

The late Marshall Sahlins, in his theory of kinship, argued that kinship is a “mutuality of being” (2013, 18) in which kinship is built on two kinds of mutuality. The first includes forms reckoned from birth, including consanguineal and affinal (thus symbolic, not biological) relations, while the second is made throughout life by “participation in one another’s existence” (Sahlins 2013, 18). Ngajakula, which involves the mutual recognition of shared Law through the infrastructure of travelling Dreamings, emphasises both. It promotes a sense of kinship with a wider community than arguably was the case prior to European settlement. As Jupurrurla reflected, “they stuck together with olden time law”. The genius of Ngajakula (as with Jardiwanpa) is in the way it elaborates metaphorical aspects of localised Dreamings to reinforce shared Law.

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Gordon Japangardi Presley, the late Peter Japanangka Williams, Lucy Nampijinpa and other senior Willowra people for encouraging us to record the Ngajakula ceremony and for providing exegesis for this publication. Thanks also to Lance Lewis and Dwayne Jupurrula Ross for their assistance with interpreting the song texts. We also thank Benjamin Lambert for notating the Ngajakula songs and Dr Graeme Skinner for his assistance with the musical score. We are especially grateful to members of the 2018 Willowra Granites Mines Affected Areas Aboriginal Corporation and Nick Raymond for their support, without which the transcription of the Ngajakula songs would not have happened. Our thanks are also due to Angela Zacharek and yapa staff of the Willowra Learning Centre, who provided space and a warm welcome for our Ngajakula workshops. We have benefited from the thoughtful comments of our anonymous reviewers and thank them for their efforts. Thanks also to Brenda Thornley for preparing the map and to the editors of this volume for inviting us to contribute to it.

References

Apted, Meiki E. 2010. “Songs from the Inyjalarrku: The Use of a Nontranslatable Spirit Language in a Song Set from North-West Arnhem Land, Australia”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30(1): 93–103.

Campbell, Liam. 2006. Darby: One Hundred Years of Life in a Changing Culture. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Warlpiri Media Association.

Curran, Georgia. 2011. “The ‘Expanding Domain’ of Warlpiri Initiation Rituals”. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Peterson, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber, 39–50. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2019. “‘Waiting for Jardiwanpa’: History and Mediation in Warlpiri Fire Ceremonies”. Oceania 89(1): 20–35.

Davidson, Alan A. and C. Winnecke. 1905. Mr Davidson’s Explorations in the Northern Territory of South Australia. Adelaide: Government Printer.

Dixon, R.M.W., W.S. Ramson and Mandy Thomas. 1990. Australian Aboriginal Words in English: Their Origin and Meaning. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Dussart, Françoise. 2000. The Politics of Ritual in an Aboriginal Settlement: Kinship, Gender, and the Currency of Knowledge. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Gallagher, Coral, Peggy Brown, Georgia Curran and Barbara Martin. 2014. Jardiwanpa Yawulyu: Warlpiri Women’s Songs from Yuendumu (including CD). Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Green, Rebecca, Jennifer Green, Amanda Hamilton-Holloway, Felicity Meakins and David Osgarby. 2019. Mudburra to English Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Handelman, Don. 1988. “Inside-Out, Outside-In: Concealment and Revelation in Newfoundland Christmas Mumming”. In Text, Play, and Story: The Construction and Reconstruction of Self and Society, edited by Edward M. Bruner, 247–77. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.

Langton, Marcia. 1993. “Well, I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …”: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and about Aboriginal People and Things. Woolloomooloo: Australian Film Commission.

Laughren, Mary, Kenneth Hale, Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan, Patrick Marlurrku, Paddy Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Laughren, Mary, Georgia Curran, Myfany Turpin and Nicolas Peterson. 2016. “Women’s Yawulyu Songs as Evidence of Connections to and Knowledge of Land: The Jardiwanpa”. In Language, Land and Song: Studies in Honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch and Jane Simpson, 419–449. London: EL Publishing.

Meakins, Felicity, Patrick McConvell, Erika Charola, Norm McNair, Helen McNair and Lauren Campbell. 2013. Gurindji to English Dictionary. Batchelor: Batchelor Institute Press.

Meggitt, Mervyn. 1962. Desert People: A Study of the Walbiri Aborigines of Central Australia. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Michaels, Eric. 1986. The Aboriginal Invention of Television in Central Australia 1982–1986. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Morton, John. 2011. “Splitting the Atom of Kinship: Towards an Understanding of the Symbolic Economy of the Warlpiri Fire Ceremony”. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Peterson, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber, 17–38. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Mountford, Charles P. 1968. Winbaraku and the Myth of Jarapiri. Adelaide: Rigby.

Nash, David. 1990. “Patrilects of the Warumungu and Warlmanpa and their Neighbours”. In Language and History: Essays in Honour of Luise A. Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch and Jane Simpson, 209–20. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics C-116.

Pensalfini, Rob. 2011. Jingulu Texts and Dictionary. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Peterson, Nicolas. 1970. “Buluwandi: A Central Australian Ceremony for the Resolution of Conflict”. In Australian Aboriginal Anthropology: Modern Studies in the Social Anthropology of the Australian Aborigines, edited by Ronald M. Berndt, 200–15. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Peterson, Nicolas. 2000. “An Expanding Aboriginal Domain: Mobility and the Initiation Journey”. Oceania 70(3): 205–18.

Reece, Laurie. 1979. Dictionary of the Wailbiri (Warlpiri, Walpiri), Language (Oceania Linguistic Monographs 22). Sydney: University of Sydney Press.

Sahlins, Marshall. 2013. What Kinship Is – and Is Not. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sandall, Roger, dir, Nicolas Peterson, narr, and Kim McKenzie, ed. 1977. A Walbiri Fire Ceremony: Ngatjakula. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Spencer, Baldwin and F.J. Gillen. 1904. The Northern Tribes of Central Australia. London: Macmillan.

Vaarzon-Morel, Petronella and Luke Kelly. 2020. “Enlivening People and Country: The Lander Warlpiri Cultural Mapping Project”. In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, edited by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 111–138. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Wild, Stephen. 1975. Walbiri Music and Dance in Their Social and Cultural Nexus. PhD thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Wild, Stephen. 1977. “Men as Women: Female Dance Symbolism in Walbiri Men’s Rituals”. Dance Research Journal 10(1): 14–22.

Wild, Stephen. 1979. “A Public Song Series of Central Australia”. Unpublished paper presented to the Third National Conference of the Musicological Society of Australia, Monash University, 18–21 May.

Wild, Stephen. 1984. “Warlbiri Music and Culture: Meaning in a Central Australian Song Series”. In Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, edited by Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington, 186–203. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Wild, Stephen. 1987. “Recreating the Jukurrpa: Adaptation and Innovation of Songs and Ceremonies in Warlpiri Society”. In Songs of Aboriginal Australia, edited by Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Wild, 97–120. University of Sydney: Oceania Monographs.

Dolly Nampijinpa (Daniels) Granites (1936–2004)

Dolly Nampijinpa (Daniels) Granites was a Warlpiri leader, artist and land rights advocate. Born a decade before her people were forced to settle at the Central Australian ration depot of Yuendumu in 1946, Dolly showed an early and keen interest in promoting Warlpiri culture beyond the confines of the settlement.

Through marriage and family kin ties, Dolly ultimately acquired fluency in languages and rituals that extended beyond Yuendumu. She used this extensive knowledge – which included Pitjantjatjara, Pintupi, Anmatyerre and Gurunji Dreamings from as far away as Darwin and Uluru – to educate not only the Warlpiri but also numerous non-Aboriginal researchers. She helped found and subsequently chaired the Warlulurlangu Artist Association, which continues to thrive at Yuendumu. She was a key participant in the monumental land claims of 1976 and 1984, which ultimately returned large territories to the Ngalia-Warlpiri.

I am strong and can know about rituals because I hold this strength about knowing from my father’s father and my fathers’ sisters, my mothers, my mothers’ mothers, my mothers’ brothers, and my husbands. I hold them all in my heart and people know I can sing Dreaming stories all the way over many countries. (Dolly Nampijinpa Daniels, 2000)

Judy Nampijinpa Granites (1934–2015)

Judy Nampijinpa Granites was an extraordinary Warlpiri leader and land rights advocate. As a child, Judy moved around with her family enjoying their hunting and gathering way of life until her parents came to live near Mount Doreen (where non-Indigenous people mined for copper and tungsten). Along with others, she was relocated to a ration depot called Yuendumu in 1946. Even as an adolescent and young mother of five boys, she showed great interest in ritual and political affairs within and beyond the confines of the settlement of Yuendumu. She encouraged her sons to get educated and involve themselves to better the lives of their people. Judy – through marriages, kin ties and her involvement with missionaries, land rights activists and researchers – visited many Indigenous territories and communities. Judy was an extraordinary teacher and philosopher who promoted the cultural rights of her people with verve and aplomb. She remained curious about other cultures and the plight of other Indigenous peoples worldwide until her tragic death.

Lynette Nampijinpa Granites (c.1945–)

Nampijinpa was born in 1945 at Mount Doreen Station. She grew up and was educated in Yuendumu in the early Baptist Mission. Following on from her older sisters, who were key leaders for ceremonies in Yuendumu for many decades, Nampijinpa is an important senior yawulyu singer. She is kirda for Warlukurlangu “Belonging to the Fire”, Ngapa “Rain/Water” and Pamapardu “Flying Ant” jukurrpa. Nampijinpa is also an acclaimed international artist and has exhibited her paintings worldwide. She has also long held an important role on the board of the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority as well as with the Yuendumu Mediation committee. She worked closely with the Central Land Council alongside her late husband, Harry Nelson Jakamarra.

1 Sadly, Jungarrayi has since passed away, but his legacy lives on through his songs. Jungarrayi was also known in daily life as “Cowboy George”. Out of respect, we refer to him here as “Kumunjayi” and “Jungarrayi” throughout the remainder of this paper.

2 Personal comment to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel.

3 This word may be a variant of jarrurlujarrurlu, which the Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary glosses as “Princess Parrot”. The species is variously identified as Psephotus varius, Polytelis alexandrae and Leptolophus hollandicus.

4 Unlike other terms noted here, Jutiya does not appear in the Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Our identification is based on the description of the snake – its characteristic appearance and behaviour – as given by George Jungarrayi.

5 The name may be related to the Warlpiri word jinjirla, one meaning of which is the tip of the tail of the Rabbit-eared bandicoot. Jinjirla can also refer to any flower or blossom; at Willowra, it can designate flowers used in a ritual headdress.

6 The historical association of Ngajakula with Warlpiri is attested by Laurie Reece, who noted that the “ngatjukula” [Ngajakula] ceremony is “for general viewing and participation” (1979, 28). Although Reece’s dictionary was published in 1979, it is based on his research conducted at Yuendumu 30 years earlier.

7 See Curran (2019) for a detailed account of the history of documentation of fire ceremonies at Yuendumu.

8 Initially identified by Peterson as a stork or pelican (see later discussion).

9 In 1987, Vaarzon-Morel viewed this film with Elders at Willowra who were critical of the way the Ngajakula ceremony was performed, stating that it mixed up Jardiwanpa with Ngajakula. This may be due to the way the film was edited, truncating songlines, but also, as Peterson (1970) noted, because Willowra leaders were not present at the ceremony.

10 Several years ago, reflecting on the performances of fire ceremonies over time, Nicolas Peterson observed a shift in focus of the ceremonies from conflict resolution to memorial commemoration (personal communication to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 2019).

11 See also Gallagher et al. (2014).

12 Although this explanation was also offered by Dussart, it was not explicitly mentioned by Spencer and Gillen or Peterson. The question then arises as to whether the emphasis of the ceremonies changed over time. Let us return to Spencer and Gillen’s account. Although the ethnographers do not discuss an association between the fire ceremony and mourning, the fact that the bodies of some performers were daubed in white pipeclay (Spencer and Gillen 1904, 389), which is used for Sorry Business, strongly suggests such an association. Further, the ceremony involved mockery, concealment and inversion (Spencer and Gillen 1904, 377–379, 386–388), which “often are associated with the periodicity of transition” (Handelman 1988, 247). It seems likely then that the fire ceremony, which followed upon a final mortuary ritual involving “bone breaking”, was concerned with the ending of a widow’s period of mourning as well as conflict resolution.

13 Jerry Jangala Patrick, personal communication to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 8 June 2016. The information in this section is based on Vaarzon-Morel’s fieldnotes from the period when she lived at Willowra and conducted research at the invitation of the Willowra community.

14 The prevailing winter wind comes from the south and is associated with the dust kicked up by the Dancing Women as they travelled.

15 The connection with this constellation is intriguing, and it may be the case that different astronomical phenomena are involved, as occurs in other Warlpiri ceremonies. See, for example, Chapter 3 of this volume where Peterson discusses a performance of the Warlpiri winter solstice ceremony involving the “Daylight Star”, also called the “Morning Star” (Venus).

16 They may also have been held at other times.

17 Previously known as “Warrabri”.

18 Following the culmination of the fire ceremonies at Willowra, it was a widow’s choice if she decided to stay in the jilimi (“single women’s camp”) or if she took a partner.

19 Japangardi Williams, personal communication to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 6 November 1987.

20 Napaljarri, personal communication to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel.

21 For example, Vaarzon-Morel noted this to occur in the 1980s, when a senior kirda for the mala (Rufous Hare-Wallaby) Dreaming at Ngarnalkurru visited Uluru and connected the Warlpiri songline to that of Yankuntjatjarra owners of Uluru. Not long after, people from Uluru visited Willowra and exchanged ceremonies.

22 And kin-based relationships among countries.

23 During discussions of Ngajakula as part of the mapping project in 2016, Jupurrurla cryptically remarked that “them Anmatyerr people used to have ceremony like Ngajakula, but they forgot about it”.

24 Martin Jampijinpa, personal communication to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 2008.

25 The last few men travelled from Warrabri.

26 T. Long Jupurrurla, personal communication to Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, 9 April 2021.

27 This word is distinguished from the Warlpiri term ngurlu (meaning “seed”) because it refers to a form of totemism inherited through the matriline (mother’s brother). It is not estate-based like Warlpiri Dreamings. Nonetheless, we gratefully note an anonymous reviewer’s observation that, while it’s possible the Warlpiri term for ngurlu totemism may be only accidentally homophonous with the Warlpiri term for “seed”, several “ngurlu” in the Elliott region are actually the names of seeds. M.J. Meggitt is the only ethnographer to have noted that “the Walbiri belief in matrispirits is historically connected with the ngulu beliefs of the neighbouring Mudbara, Djingili and Warramunga” (1962, 193). He likened the “Walbiri stress [on] the solidarity of the matriline at the betrothal or death of a member” (1962, 193) to the support that Murinbata ngulu clansmen give each other further north.

28 See also Meggitt (1962, 29, 35–36).

29 Jungarrayi named “One Fella Boot” Jangala as a main kurdungurlu.

30 Cf. Peterson (2000, 207).

31 It is beyond the scope of this paper to address the symbolism of the Dreamings except in passing.

32 Warlpiri sometimes also refer to Kurrakurraja as a “pelican” or kalwa “stork”, which likely accounts for Peterson’s (1970) initial identification of a “stork” or “pelican” as the main ancestral figure of Purluwanti.

33 This term refers to in-law pairs. People in jurdalja relationships “exchange their children as mother-in-laws (malirdi)” and also gifts such as boomerangs and shields. The jurdalja relationship is reciprocal (Laughren et al. 2022, 141).

34 Not necessarily in the same direction.

35 At the request of Jungarrayi Ryder and other Willowra Elders, copies of this material are deposited on a designated cultural heritage computer at Willowra Learning Centre; the material is also archived at Central Land Council for Willowra people’s future use. Work on further analysis of the material with Willowra community is not yet completed.

36 Named “Buchanan’s Hills” on 10 June 1900 by Allan A. Davidson, leader of the Central Australian Exploration Syndicate, to honour a member of the expedition called George Buchanan (Davidson and Winnecke 1905, 26). The low range is located 77 kilometres south-east of Lajamanu, near Duck Ponds outstation (Mirirrinyungu).

37 Jurlarda travels from Muntarri (Gilbert Well, south of Tennant Creek) through Kanturrpa to Yirrinirli (on the Lander) and Ngunulurru.

38 Also known as pirntina and malilyi in southern dialects of Warlpiri and as “woma” in English (a borrowing from Diyari, according to Dixon, Ramson and Thomas 1990, 106). The word panungkarla is no doubt related to baningkula, glossed by the Mudburra to English Dictionary (Green et al. 2019, 73) as “Water Python” (Liasis fuscus) and said to be a creator of “the central Dreaming track for Jingili people. All the other Dreaming tracks connect with or cross this one.”

39 Also known as kalwa in southern dialects of Warlpiri. This may suggest an association with the “White-Necked Heron”, called jarlwa in Gurindji (Meakins et al. 2013, 88; these authors identify the species as Egretta pacifica [Ardea pacifica?]) or, alternatively, with the “Blue Crane”, called darliwa in Jingulu (Pensalfini 2011, 136), probably Egretta novaehollandiae. Pensalfini (2011, 198) noted that darliwa is specifically associated with Murranji.

40 Honey (and honeycomb) produced by Minikiyi “Native Bees” (Trigona sp.).

41 This name may be related to Warumungu/Warlmanpa milywaru, tentatively glossed as “quiet snake species” by Nash (1990, 212).

42 The name of the site of these events, Kulunganjalpa, is no doubt based on the Warlpiri word kulu “a fight”.

43 Textual transcriptions by Jim Wafer, musical transcriptions by Benjamin Lambert.

44 Songs of the latter type are generally regarded as untranslatable (see Apted 2010).

45 As we have discussed earlier in the chapter, in relation to differing ethnographic accounts of the fire ceremonies, this is the case not only for Aboriginal people but also for their non-Indigenous interlocutors.