9

To perform or not to perform the Ancestral Fire Dreaming from the Warlukurlangu ranges (Central Australia)

On 8 August 1983, a few months after my arrival at Yuendumu to conduct original research for my PhD thesis, senior women relaxing on the Women’s Museum lawn were talking about an Ancestral Fire Being – ignited by an Ancestral Blue Tongue Lizard that mercilessly chased two ancestral young brothers, his sons. Conversations went on for the next two days and, even with my then-rudimentary understanding of the Warlpiri language, there was no possible mistake – the manifestation of the ancestral beings of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming (Warlu jukurrpa) that travelled through the Warlukurlangu ranges (south-west of Yuendumu) would be performed soon in a women’s public ceremony (yawulyu). A few days later, I was summoned by Lindsay Jampijinpa Turner, who was then president of the Yuendumu Council; he asked me to facilitate a recreational trip to Adelaide for seniors. This was the first of its kind; among the 29 Elders who would come along, only a few had ever visited such a large city. While the dates for the trip were vague, I was tasked with collecting money from the seniors to pay for their return train fares from Alice Springs to Adelaide and their accommodation.

It would take me months before I could understand why the Ancestral Fire Dreaming had been chosen as the centrepiece performance in Adelaide at two local institutions: an Aboriginal college and a local university. This memorable trip would cement, for many years to come, my relationships with two formidable ritual specialists: Judy Nampijinpa Granites (1934–2015) and Dolly Nampijinpa (Daniels) Granites (1936–2004).

In this chapter, I highlight special moments of when, where and why Judy and Dolly orchestrated representations of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming stories over three decades. I show how the performances they led met the pragmatics of their changing world through realignment, diplomacy and advocacy. I explain why, in some instances, Judy and Dolly did not perform the Ancestral Fire Dreaming and chose more inclusive Ancestral Dreaming stories, nurturing their search for greater relatedness and sense of belonging. I conclude with a few reflections on how ceremonial knowledge and reenactments remain mechanisms for withstanding, accommodating and extending other possible ways of what it means to belong in an entangled world (see also Dussart and Poirier 2017; Curran 2020).

Two ritual specialists and the Ancestral Fire Dreaming

Before I begin to chart where and for whom the Ancestral Fire Dreaming that created the Warlukurlangu ranges would be staged over the next 30 years, let me first introduce the two exceptional individuals who, among many others, have celebrated the legacies of their ancestors through incredibly tumultuous decades since they sedentarised in 1946 at a government-run ration depot called Yuendumu. I would be remiss if I did not mention how difficult it has been to celebrate here only two women with ontological connections to the Ancestral Fire Dreaming; however, space is restricted. Both lived relatively long lives and devoted themselves to maintaining what mattered: their kinship relationships and their sense of belonging to their territories crisscrossed by the Dreaming. While they are no longer with us, both would have enjoyed reminiscing about the different performances of their Ancestral Fire Dreaming stories as well as adding to, emending and reflecting on their memories, making what follows so much richer. Thus, what I present here is a truncated version of events anchored in our conversations, observations, recordings, photographs and fieldnotes. Neither of them ever grew bored of telling me about their familial entanglements with one another, with the ancestral beings that crisscrossed the many Countries for which they held patrilineal or matrifilial rights or Countries and associated Dreamings about which they had learned during pan-Indigenous ceremonial meetings. Their patrilineal ties to the Ancestral Fire Dreaming were strong, and both enjoyed singing, telling and performing the stories of the Ancestral Fire Beings.

Judy held rights as an owner (kirda) through her father, who was born at Ngarna, a site on the Warlukurlangu ranges. Dolly’s father was Judy’s father’s brother, also born at Ngarna. Dolly and Judy shared the same father’s father, the remarkable ritual specialist and leader Wanyu Jampijinpa. Dolly’s conception site and place of birth were also located in the Warlukurlangu ranges area, as were those of her father’s father. Both Judy and Dolly were very much respected ritual specialists when I arrived at Yuendumu, along with a close brother Jack Jampijinpa Gallagher, a much younger brother Lindsay Jampijinpa Turner (the Yuendumu Council President), two close younger sisters Molly Nampijinpa Langdon and Diana Nampijinpa Marshall, and four close paternal aunts, Rosie Nangala Fleming, Tilo Nangala, Winnie Nangala and Judy-Peggy Nangala. In fact, most owners of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming had resided at Yuendumu since the beginning of the settlement and later at outstations located within a 50-kilometre radius of Yuendumu. The owners of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming from the Warlukurlangu ranges had not been split up between different settlements, as was the case for some other family groups separated in the late 1940s between Yuendumu and Lajamanu, another settlement some 580 kilometres north. Further, the managers of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming, who held their rights and responsibilities through their matriline, also remained at Yuendumu or lived on a nearby cattle station Yuelamu (then called Mount Allan). The reciprocal ties between owners and managers had not been severed – an important element in facilitating the celebration of their Country.

In general, Judy and Dolly were both extremely knowledgeable in all ceremonial matters. As Dolly once remarked, when I marvelled at her extensive knowledge of ritual performances, songlines, designs and experiences, well beyond those she held through her patriline or her matriline and beyond Warlpiri territories.1

Dolly, as a younger sister, should have deferred to her older sister Judy for all decisions related to ceremonial performances; however, they always treated each other more as ritual partners recognising each other’s strength in the realm of the ontological. Not once did I hear them argue about the correctness of a song or design or ritual choreography or representation of ancestral stories on a canvas for sale. Not once did I witness others challenging their knowledge of a songline, the orchestration of a dance or a ceremonial body design. Under the watchful eyes of their managers, such as the famous Lucy Napaljarri2 Kennedy and Emma Nungarrayi, their performances for the Ancestral Fire Dreaming enacted the following story.3

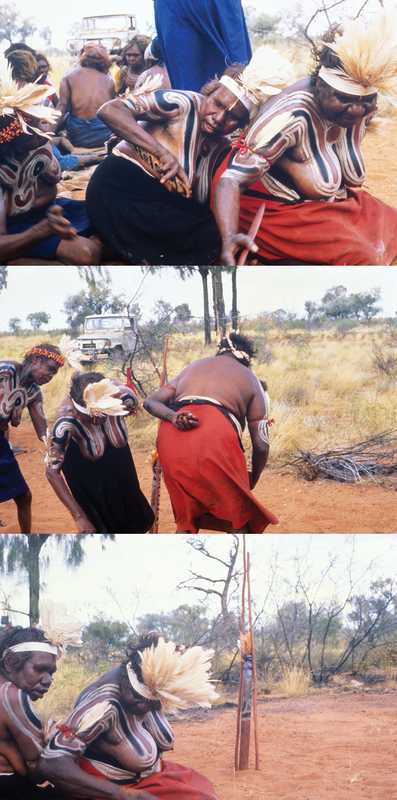

Figure 9.1 Judy (left) as the older brother, Dolly as the younger brother, both getting ready to perform. Lucy Napaljarri Kennedy as a manager getting ready to join the singers. Photo by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

The Ancestral Fire Dreaming begins at a place called Yampirripanturnu where two handsome Jangala brothers were born from a spearwood tree (winpiri, Pandora doratoxylon). They emerged from this tree, all decorated for ceremonies, with their bodies oiled and red-ochred. Their father, Jampijinpa, was a Lungkarda (Blue Tongue Lizard). All three lived in a place called Panirripanirri near the Warlukurlangu ranges. Since the father was blind, the two Jangala brothers hunted to feed all three (see Figure 9.2). The sons would get up at dawn, straighten their spears and leave.

Once they were gone, their father would take his spear and his spear thrower and would go hunting for himself – as he was only pretending to be blind. While his sons hunted in the area around Ngarna and in the Warlukurlangu ranges, he would cook his meat and erase all traces of his walking around, eating and cooking before they came home. After spearing many kangaroos, including a special joey, they partially cooked the meat, returned to their camp and offered food to their father, who they believed was hungry. At night, the father was accustomed to wakening and listening to a special joey calling out to his mother – “ts, ts, ts”. That night, he did not hear the joey and soon began to suspect that his sons had killed it and given it to him to eat. He was furious and, to punish his sons for having killed his joey, which to him was like a human being, he sang a magical Ancestral Fire Being verse (see Figure 9.3).

The next day, the two sons went hunting and saw a big black cloud of smoke coming from their father’s camp; they feared he might get burned, so they decided to return home. The fire starts to surround them, forcing them further south (see Figures 9.4 and 9.5).

But the magical Ancestral Fire Being was soon behind them, at times propelling them into the air as in an explosion of kerosene. In vain, they tried to extinguish it; in vain did they try to return home to their father. The long and fluffy hair of the two Jangalas, as well as their skin, started to burn (see Figure 9.6).

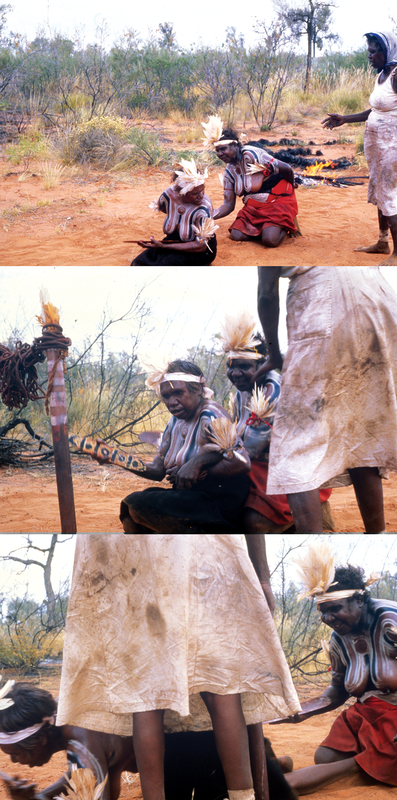

Their bodies were charred, and they could barely walk, continuously pursued by the Ancestral Fire Being. The older brother helped his injured younger brother to enter a men’s secret cave located in the Warlukurlangu ranges (see Figure 9.7).

Deploying public representations of the Ancestral Fire Beings’ stories as a means of cross-cultural advocacy

At this stage, readers might wonder why I privileged the Ancestral Fire Dreaming story and its reenactments. To my knowledge, a 1971 public performance of this story was the first deployed as a means of cross-cultural advocacy by Yuendumu owners and managers of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming. Following the ceremonial representations of this Dreaming itinerary provides a window into how Yuendumu residents have maintained their intimate relationships with their original territories and, in turn, how they have differently deployed ritual performances to renegotiate relations with one another and other Indigenous Australian groups, as well as illuminate our understanding of how realignments with ceremonial knowledge and performances are entangled with other Indigenous groups and the settler society at large.

Figure 9.2 (Top) Judy and Dolly going hunting while their father (represented here by Judy-Peggy Nangala) starts singing the magical fire. (Bottom) Judy and Dolly hunting for kangaroos. Photos by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

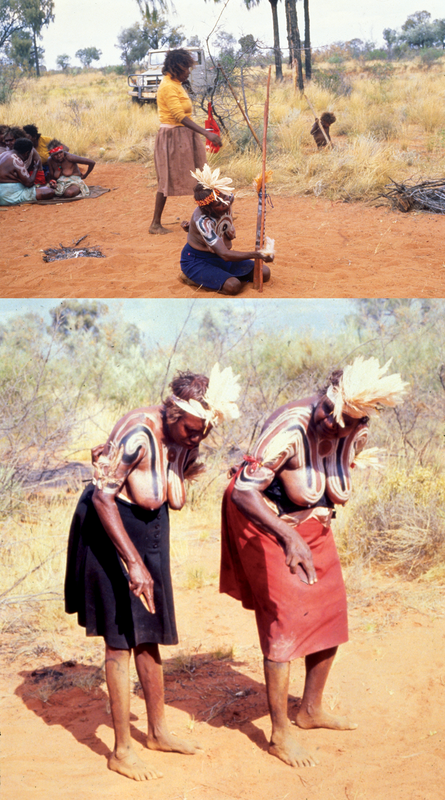

Figure 9.3 (Top) While they hunt, the father redoubles his effort to send the magical fire to destroy his sons. (Middle) The brothers are hunting and finding many kangaroos. (Bottom) The father sees his sons in the distance and can see that the fire is closing in on them. Photos by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

Figure 9.4 (Top) The father relentlessly sings the magical fire. (Bottom) The brothers see black smoke coming from the area where they live and worry about their father and try to run back to him. Photos by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

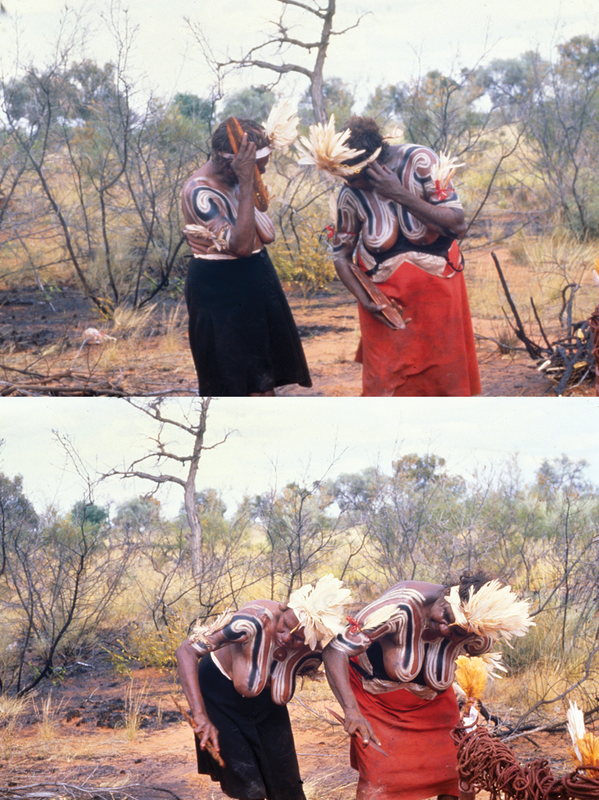

Figure 9.5 (Top) Soon, the fire is enveloping them and forces them to travel a long way south to Kaltukatjara. (Bottom) They try to push the fire away unsuccessfully and they worry for their father under the watchful eye of a manager Emma Nungarrayi, a sister of Dolly’s mother. Photos by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

Figure 9.6 (Top) The fire burns their hair, their ears, their skin off – it burns them inside out. Now they are very worried about their father. (Bottom) They managed to return towards their home camp while the Ancestral fire burns them. Photos by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

Figure 9.7 (Top) They can barely walk, continuously pursued by the magical Ancestral Fire Being. (Middle) The older brother is helping his younger brother. (Bottom) Exhausted and charred, they both enter a men’s secret cave. Photos by Françoise Dussart, 1983.

In 1971, Yuendumu was threatened with possible uranium mining in the Warlukurlangu ranges (Dussart 2000). In 1983, both George Japangardi Marshall, a manager for the Ancestral Fire Dreaming married to Diane Nampijinpa, and Jack Jampijinpa Gallagher remembered these trying times well. They both recalled how the traditional owners led by the famous Wanyu Jampijinpa decided to respond to the further desecration of their Country by deploying a ritual performance (see also Glowczewski and Gibson, Chapter 4, this volume). They decided to perform a purlapa (men’s public ceremony) for the non-Indigenous miners to declare their ownership of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming Country at the time unrecognised by the Commonwealth. That performative answer became quite a significant event. While the miners ceased further exploration as the first test results were disappointing, the traditional owners and managers could only praise their decision to play power diplomacy by singing and dancing the Ancestral Fire Dreaming. From their perspective, the miners had seen the light, so to speak, and understood the powers of the Ancestral Fire Beings whose Country should be kept intact. As related to me a decade later by Jack and George, all believed that their ownership declaration – a men’s public representation, or purlapa – had been a persuasive mode of land repossession.4 Their decision to perform a public ceremony usually reserved for Indigenous eyes only would soon be understood by the Yuendumu Warlpiri as one of the rituals that could be performed during land claim reclamations after the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act of 1976. Following the first land claim hearing, the Warlukurlangu ranges were included in the area recognised as Warlpiri land.

Something else happened after the successful land claim – a remarkable gender rebalancing act – senior female ritual specialists became the ritual spokespersons, so to speak, and took over the performances of all public rituals created for diplomatic and advocacy purposes. Judy and Dolly became experts at deploying their intimate knowledge of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming, among others, for inter- and intracultural audiences. Combined with their early success with the miners ending their search in the Warlukurlangu ranges and their experiences of land claims allowing their ritual knowledge to be used as a tool for legitimating Indigenous claims to vacant crown lands, the public performances of the land-based Ancestral Fire Dreaming became a mode of reference for Warlpiri ritual specialists who saw the importance of keeping the dynamism of Warlpiri people’s cultural legacy (see also Dussart 1997), as well as reaffirming their ownership of the land to non-Warlpiri and non-Indigenous audiences. While the public performances of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming thus far had been held at Yuendumu or onsite in the Warlukurlangu ranges, in 1983, a new opportunity presented itself that would force on-the-spot performers to reassess their authority (see also Peterson, Chapter 3, this volume) and to realign their power diplomacy strategies.

Bringing the Ancestral Fire Dreaming to a “big city”!

Now back to our four-day recreational trip to Adelaide in late October 1983, some 2,000 kilometres south of Yuendumu. At the time, still very few Yuendumu residents had visited cities unless they were flown into a larger hospital. The Elders wanted to visit Adelaide, go to the zoo, buy clothes at second-hand shops and visit Woollies.5 To offset some of their expenses, they would be performing public ceremonies for institutions they believed would be keen – that is, willing to compensate them for showing their sacred patrimony – to witness Warlpiri ritual performances. So, as the seniors saved money for their Adelaide excursion, they were also busy negotiating what public representations could be performed. What transpired over several visits to important sacred sites associated with the Ancestral Fire Dreaming during a period of three months prior to the Adelaide visit was that the Ancestral Fire Dreaming would be featured, as well as other Dreamings that crossed the paths of the Ancestral Fire Beings from the Warlukurlangu ranges. A rehearsal of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming at the site of Ngarnka took place, augmented by reenactments of other intersecting Dreaming beings’ stories.

As we sat for many hours on a train between Alice Springs and Adelaide, the women checked several times that they had packed everything necessary to perform the Dreaming for their new city audiences. Once in Adelaide, most of the 29 women who travelled to the city led by Judy and Dolly gave two main yawulyu performances, first at a local Aboriginal college and then at a university. However, nothing went as originally planned. When we arrived at the local college, only about a third of the women prepared themselves to dance while others would sing. Judy and Dolly decided it would be best to first dance briefly for the Dreaming stories associated with the joint ritual cycle Jardiwanpa, which was about to be performed at Yuendumu, because it involved – in one performance – most of the group painted up. Then, Judy, Dolly, Rosie and Tilo would perform a truncated version of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming. Unlike the rehearsals at Yuendumu and at Ngarna, which featured elaborated performances of different Dreaming stories owned by different groups one after the other, it became clear early on that payment may not be offered to the performers by the local college, so the representations would be much shorter, revealing as little as possible of their stories. The women reluctantly began to dance and, as they rapidly finished the first reenactment of the Jardiwanpa under Dolly’s lead, Judy mumbled under her breath to her fellow performers that “we cannot show the jukurrpa and get nothing, they are being disrespectful”. The performance dramatically stopped, and Dolly called out to her brother Lindsay, asking him to declare loud and clear in English to their Indigenous audience that “we cannot show our women’s painted breasts for nothing!” (see Curran and Dussart, 2023). The audience seemed stunned, and all the school officials could offer were cheese and ham sandwiches after the performances – a very inadequate payment from the performers’ perspectives. Thus, they decided to perform an even more condensed version of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming for the second half of their presentation, which lasted barely more than four minutes. The performers were annoyed that the local Indigenous people did not seem to understand that no matter the audience and the circumstances, acceptable payments such as blankets, money and drums of flour should always be offered for performances celebrating Indigenous elemental forces – the Dreaming stories. That evening after dinner, Judy and Dolly were categorical: the women would not perform at the next venue for a university audience without “proper” payment. The selection of the performance sites had been mainly led by contacts that Warlpiri people had in Adelaide, but the question of payments had apparently never been discussed. So, that evening, the pressure was on, and I was tasked to make sure that since university was “my” world, I should demand payment for all the performers! Two days later, we were gathered in a large room with an audience of about 50 or so predominantly non-Indigenous people sitting on the floor, ready to witness the women’s yawulyu. As about 14 women got ready and painted up, a fellow anthropologist (to whom I had explained our conundrum prior to our arrival over the phone and who had made the event at all possible) scrambled to organise a last-minute payment. I was able to reassure the performers that they would be compensated with a small dollar amount, which seemed to them barely reasonable but reasonable enough to go on with their performances. While disappointed, the performers danced with pride for a very enthusiastic and honoured audience, and their performance of the Ancestral Fire Dreaming was more robust than at the Aboriginal college event. That evening, back at our accommodation, both men and women discussed how the strength of the women’s performances made the university audience “happy”6 and aware of the performers’ knowledge of their Dreamings and their responsibilities towards and ownership of the land. What was performed in Adelaide was a modified version of what they had rehearsed and planned to perform prior to their trip; it bore the mark of creative, historical and political processes of the moment. However, a land-based yawulyu for the Ancestral Fire Dreaming had been officially performed for cross-cultural consumption beyond the confines of Warlpiri territories. To some extent, what transpired in Adelaide was that performers expected non-Warlpiri audiences beyond the confines of the settlement to provide travel support and payments, as well as venues to promote Warlpiri performances as a whole. We could add another factor – governmental and non-governmental supports – onto Catherine Grant’s 2014 typology measuring musical vitality, as highlighted by the editors of this volume in Chapter 1.

From 1984 until 1989, Judy and Dolly performed the Ancestral Fire Beings from Warlukurlangu at museum openings, such as the opening of the first major Warlpiri exhibition at the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, titled Yuendumu Paintings: Out of the Desert in 1988 (Dussart 2014). The Ancestral Fire Dreaming was one of the six large songlines painted on canvas with acrylics featured in the exhibition. At the opening, Dolly, Judy, Rosie and Tilo performed brief yawulyu sequences reenacting the stories of the Ancestral Blue Tongue Lizard and his two sons. These sequences were chosen to highlight the personal connection to the stories and the performers. They began by showing the two brothers straightening and picking up their spears each morning to go hunting – a sequence for which Dolly dreamed songs and designs – while the father wiped away his footprints and made his fire look like an old one – a sequence dreamed by Judy’s father. As in Adelaide, public representations of specific Dreaming stories never worked out as originally planned but rather became defined by the politics of relatedness in situ.

To perform or not to perform the Ancestral Fire Dreaming stories

A year after the public yawulyu for the Ancestral Fire Dreaming in Adelaide, seven women from Yuendumu travelled 1,600 kilometres to Kaltukatjara (Docker River) to participate in a large initiation ceremonial cycle performed by both men and women separately called Kajirri (see Dussart 2000, 169–176; Glowczewski 2016, 246). Before their departure and following a set of conflicts I have discussed elsewhere (Dussart 2000, 166–168), Judy and Dolly were planning to connect the stories of their Ancestral Fire Dreaming that had travelled to Kaltukatjara with those of women from that region. A couple of days after our arrival for the ceremonies at Kaltukatjara, Dolly and Judy decided not to perform the Ancestral Fire Dreaming as it was not a Dreaming itinerary shared by most women in attendance. Instead, Dolly and Judy decided to dance recently revealed stories about Ancestral Emus who travelled and shaped many territories and sites shared by most (see Dussart 2000). This was not a moment of ritual knowledge exchange but rather a realignment of performative priorities, declaring how the specific stories of the travels of the Ancestral Emus were all connected without the traditional transfer of the performative rights of ritual production from the performers to the viewers. Such ceremonial decisions were aligned at the time with the production of encompassing relatedness among Indigenous people residing in Central and South Australia (see also Myers 1986; Peterson 2000). They are also moments when viewers are witnessing and reaffirming the legitimate right of the performers to perform (see Peterson, Chapter 3, this volume).

Performative choices highlighted at the museum opening in Adelaide or at Kaltukatjara constitute a paradigmatic example of what I have observed until 2004 when women performed public yawulyu ceremonies privileging inclusiveness and emphasising relatedness (see also Curran, Martin and Barwick Chapter 5, this volume). Such choices must be understood as the realignment of ownership and relatedness. These rearticulations dialogue with initiatives in other ritual performances that continue to ground Indigenous identity and relatedness, such as initiation cycles. As Nicolas Peterson has shown (2000, 213), initiation cycles seem to be widely known by many Indigenous groups throughout Central Australia rather than being under the control of a few ritual specialists – as was the case with specific Dreaming stories bounded by locality and exclusiveness. Selections of public representations of Dreamings are driven by desires for greater pan-Indigenous relatedness in Central Australia, influenced by political calculation and declaration of ritual competence coinciding with cosmological sanction. These realignments, combined with the death of many ritual specialists (e.g., Judy and Dolly), social change and the constant struggles of living, have affected how Warlpiri systems of knowledge, regimes of care and know-how are transmitted and retrieved, and are ever-changing.

Conclusion

A year prior to Judy’s death, I visited her in an aged care home in Alice Springs, some 300 kilometres from Yuendumu, where she had been sent. I had brought many recordings of yawulyu ceremonies from the 1980s. As she started to sing along for the Ancestral Fire Dreaming, she began to cry softly. I asked if she was crying because so many of her relatives had passed away and that the Ancestral Fire Dreaming was still under taboo and, thus, no longer celebrated. Judy gave me the look! The one she always gave me when I jumped to somewhat incorrect conclusions! She was simply nostalgic for the times when many would re-enact Dreamings with which they were connected personally and geo-specifically to care for their territories, their ancestral beings, their close kin. She was nostalgic for the times when the reenactment of Dreamings – such as the Ancestral Fire Beings they inherited through their patriline – were vital performances to the social production of persons. She was nostalgic for those exclusive reenactments that had to be led by ritual specialists and leaders geo-specifically tied to the Dreaming itinerary. Judy was also worried about how the younger generations would retrieve the knowledge of the Dreaming and engage with its manifestations. Judy was worried that ceremonial performances as a “poly-rhetorical” (Pualani 2007, 134) Indigenous strategy would no longer produce efficient spaces for governing and grounding Warlpiri identity, for inter- and intracultural negotiations and conflict resolutions (see many other examples in this volume, particularly Chapters 1, 3 and 4). Many ritual specialists have shared her concerns. In a 2018 interview, ritual leader and activist Harry Jakamarra Nelson eloquently urged young people to listen to recordings and watch videos of ritual ceremonies performed throughout the 20th century so they could be strong and carry on and not get to the stage when, “if the jukurrpa goes astray, you’re liable to go about aimlessly”7 (Curran and Barwick 2018). In short, both Judy and Harry hoped that the new generations could understand how to retrieve the different manifestations of the Dreaming and to shape effective spaces of relatedness, belonging and recognition, as well as revitalisation (see also Vaarzon-Morel et al., Chapter 8, this volume).

As Nicolas Peterson (2000) and Georgia Curran (2011) have shown, in the last two decades, Warlpiri people have reinvested their energy in the performances of inclusive rites of passage involving different Indigenous participants scattered over large distances rather than performing rituals professing ownership rights to specific sites and Ancestral Dreamings. Older generations today seem to fear that too much “inclusiveness” may limit the “biopolitical regime of recognition” (Simpson 2018, 171) deployed by newer generations facing further encroachments by the settler state on their lives.

In the last 15 years, women who are now in their late forties and older, such as Cecily Napanangka Granites – Dolly’s daughter – have come to care more deeply for the Dreamings for which they hold rights and responsibilities through their patriline and matriline. When I spoke at length to Cecily in 2017 at Yuendumu, she believed that initiatives led by her generation were the way forward, such as compiling knowledge about Dreaming stories recorded or photographed so everyone could continue to be yapa (Indigenous people). When I asked her what she meant by that, she replied:

I want to know where I come from, and I want others to know where they come from. I want Yapa to know so Kardiya (non-Indigenous people) know where we come from. I want to know it [Dreaming stories], that it is in my heart and in my soul.8

Cecily’s interests, shared by many of her contemporaries, revolved around intra- and intercultural forms of recognition. Her parents’ and grandparents’ understanding of belonging was imbricated in webs of kin relations, with the desire for greater relatedness aligned with ceremonial responsibilities. For Cecily’s generation, understanding of belonging has pivoted upon the complexities relating to Indigenous people placing themselves within their own shifting historical context and within a settler nation relentlessly modifying its policies about sovereignty and rights. Her understanding of Indigenous difference engages with the complex political exigencies of forms of relatedness of the past, the present and the future, and her endeavour may well lead to a new deployment of more exclusive forms of knowledge combined with inclusive pan-Indigenous and non-Indigenous forms of recognition.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Yuendumu Warlpiri people for sharing their knowledge and thoughts. I miss my friends Judy, Dolly, Molly, Rosie, Jack, Harry and George. I wish you were still among us and we could once again reminisce together and enjoy what is to come. My debt to them is beyond words. I am grateful to Georgia Curran, Linda Barwick and Nicolas Peterson for their invitation to contribute to this edited volume. Their comments were invaluable.

References

Curran, Georgia. 2011. “The ‘Expanding Domain’ of Warlpiri Initiation Rituals”. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Peterson, edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber, 39–50. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Curran, Georgia. 2020. Sustaining Indigenous Songs: Contemporary Warlpiri Ceremonial Life in Central Australia. New York: Berghahn Books.

Curran, Georgia and Linda Barwick. 2018. Filmed Interview of Harry Jakamarra Nelson and Otto Jungarrayi Sims, interviewed by Valerie Napaljarri Martin (PAW2018_-5_10_01). Yuendumu: Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications.

Curran, Georgia and Françoise Dussart. 2023. “‘We Don’t Show our Women’s Breasts for Nothing’: Shifting Purposes for Warlpiri Women’s Public Rituals—Yawulyu—Central Australia 1980s–2020s”. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. https://doi.org/10.1177/00084298231154430

Dussart, Françoise. 1997. “A Body Painting in Translation”. In Rethinking Visual Anthropology, edited by Howard Morphy and Marcus Banks, 186–202. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dussart, Françoise. 2000. The Politics of Ritual in an Aboriginal Settlement: Kinship, Gender and the Currency of Knowledge. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Dussart, Françoise. 2014. “‘Mise en Intrigue’: Quelques Réflexions sur les Expositions Muséales de Peintures à l’Acrylique des Aborigènes du Territoire du Nord (Australie)”. Anthropologie et Sociétés 38(3): 179–206.

Dussart, Françoise and Sylvie Poirier (eds). 2017. Entangled Territorialities: Negotiating Indigenous Lands in Australia and Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Glowczewski, Barbara. 2016. Desert Dreamers. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press/Univocal.

Morphy, Howard. 1991. Ancestral connections: art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Myers, Fred. 1986. Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self: Sentiment, Place, and Politics among Western Desert Aborigines. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Peterson, Nicolas. 2000. “An Expanding Aboriginal Domain: Mobility and the Initiation Journey”. Oceania 70: 205–18.

Pualani Louis, Renee. 2007. “Can You Hear Us Now? Voices from the Margin: Using Indigenous Methodologies in Geographic Research”. Geographical Research 45(2): 130–39.

Simpson, Audra. 2018. “Why White People Love Franz Boas; Or, the Grammar of Indigenous Dispossession”. In Indigenous Visions: Recovering the World of Franz Boas, edited by Ned Blackhawk and Isaiah Lorado Wilner, 166–80. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jerry Jangala Patrick

Jerry Jangala Patrick is one of the original settlers of Lajamanu in the 1950s. He came to Lajamanu (then Hooker Creek) from the Lander River area (Willowra) via Alice Springs and Yuendemu and spent his earlier adulthood working as a stockman on cattle stations in Northern Australia before settling permanently in Lajamanu. While still steeped in traditional Warlpiri culture, Jangala embraced elements of the dominant Australian culture and became the pastor of the Baptist Church in Lajamanu.

1 Judy and Dolly as ritual specialists extraordinaire once counted for me how many songlines traversing many Countries and owned by many different Indigenous groups and families they knew: over 30. On average, a senior woman would typically know about 3 or 4.

2 Lucy Napaljarri Kennedy was an incredibly active ritual leader who participated in many successful land claims. She was also involved in many initiatives that made the settled lives of people at Yuendumu more interesting and rewarding. She was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 1994 for services to the Yuendumu community. She remains one of the few Indigenous Australians to have received such an honour. Lucy was very proud of having been nominated and for receiving it.

3 See Dussart (2000) for a more detailed account.

4 Morphy noted also in his work with the Yolngu that, progressively, they came to make a connection between performance of Dreaming stories (bark-paintings for the Yolngu) and “political” advocacy in a Western sense (1991, 17).

5 Woolworths – colloquially “Woollies” – is an Australian chain of supermarkets.

6 Literally, making one’s stomach feel good due to seeing the powers of the marvellous ancestral beings.

7 “If the jukurrpa goes astray, you’re liable to go about aimlessly” is translated from the Warlpiri jukurrpa ngula kaji ka warntarla kari yani kaji kanpa wapakarra wapami. I want to thank David Nash for his pointed translation and discussing the issues relating to “loss” and “going astray”. While, as I understand it from my Warlpiri teachers, the idea of “cultural loss” has a bounded quality and seems to be primarily rooted in a western way of thought, the idea of the Dreaming going astray emphasises the movement qualities of the Dreaming – the force that contextualises spatial relationships and intentions through time. In other words, the Dreaming can never be lost and can always be retrieved.

8 Personal communication, 2017.