5

For the An-barra: Text in English (Betty Meehan)

Note [from the Glasgow (1994) dictionary]

-guwarr (p. 343): “old customs and culture from before the white man; traditional; of long ago”.

gun-guwarr (p. 318): … See -guwarr. The prefix “gun” probably describes an old place from before the arrival of white people (Betty Meehan, pers. comm. 14 August 2024).

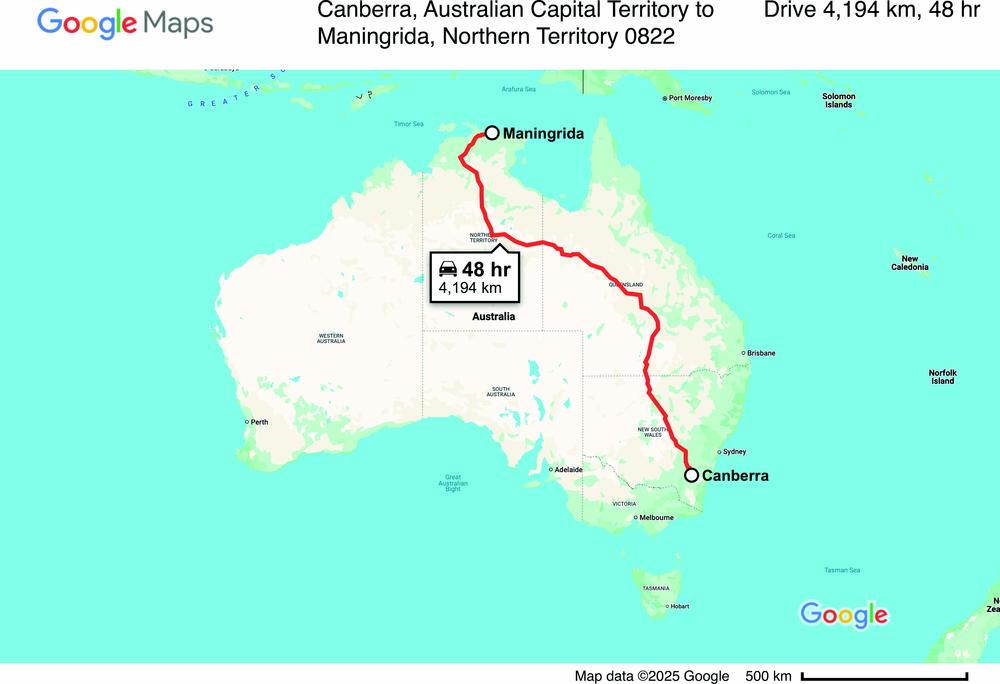

I am Betty Meehan, and this is a story about An-barra history. Les Hiatt and I came to Maningrida in 1958. We came from Canberra, a long way from An-barra country. We flew from Canberra to Darwin on an aeroplane (Map 5.1). After that we went from Darwin to Maningrida on a boat. The boat belonged to Curly Bell, and it was called The Kaprys. The sea was rough when we travelled.

Map 5.1 Maningrida, NT to Canberra, ACT (map data © 2025 Google, annotated by Adam Black).

When we arrived, we saw your old people living in Maningrida, on Kunibidji country. They were far from their country at An-gartcha Wana. They lived in a different way to balanda.

Les said to them, “I want to learn about how you live, about language, kinship and other things.” Les and I said, “We will build our tent here.” Some An-barra men helped us. We said, “The earth is dusty, let’s put shells on the ground inside the tent.” From our tent, we looked north towards where the northwest monsoon blows from, we faced the beautiful Maningrida beach to Boucaut Bay and, in the distance, the Arafura Sea.

When Barra came, we put up another tent. Then we had more shelter from Barra winds from the northwest. The Barra winds are strong. The new tent was big and we had more room to talk to An-barra people.

It was really good to sit and talk with everyone. Les soon made friends with several senior An-barra men (including Les A. and Frank G.) They visited him regularly. They began to tell him about An-barra language, kinship systems, marriage rules, religion and the right path to follow in life.

As they talked, I looked after everyone. I gave Les and the men food and drink. I also spent time with An-barra young mums with their kids and older women. We all went hunting together out bush, collecting shellfish, fish and long yams (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Betty collecting shellfish early in the wet season of 1973 (Rhys Jones).

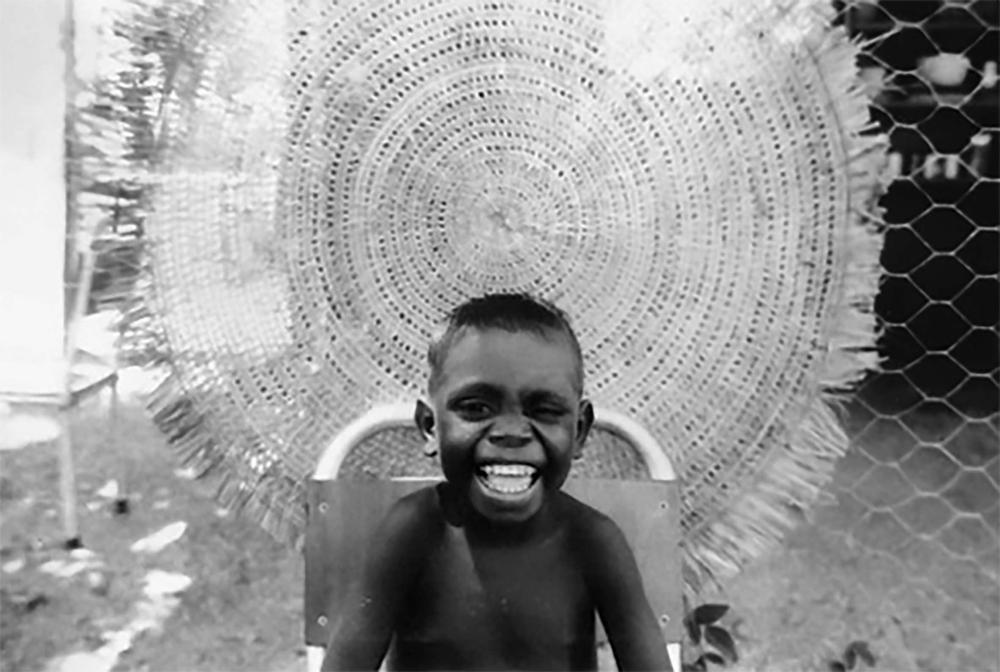

An important man, Dr Herbert Cole “Nugget” Coombs (Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia), visited Maningrida while Les and I were there, in 1958. He said to me, “Hey, why don’t you start a school?” I set up the first school at Maningrida (Figure 5.2). Several An-barra children (for example, Sam G.) were part of my first class of about 20 children – 10 girls and 10 boys. This small school has grown into a large and flourishing high school, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2018.

Figure 5.2 Students attending Maningrida School 1958 (Betty Meehan).

Les and I lived at Maningrida for one year. After that, Les and I returned to Canberra. Les thought about all the wonderful stories the An-barra men had explained to him. He wrote down all these stories. I worked as a teacher, teaching small children in Ainslie Public School.

In 1960, we came back to Maningrida. Les resumed his conversations with An-barra people. This time, we erected our tent away from the coast. We sheltered from the strong wind and rain during the wet season. I continued to spend time with An-barra women and children. The small school that I had established in 1958 had grown into a thriving establishment with highly dedicated teachers and lessons being carried out in some of the local Aboriginal languages.

I wanted to learn more about the food that An-barra people ate. I wanted to learn how they collected and prepared different foods, such as cycads, water chestnuts, Ipomoea yams, long yams, lily roots, Venus cockles, mangrove worms, mussels, and everything like that. I wanted to learn about dillybags, digging sticks, the firewood used to cook long-necked turtles, how to cook with termite mound, and so I learned all about this as I went along.

During the two years that Les and I lived at Maningrida (1958, 1960), we made some trips into the surrounding countryside, walking along the high ground and along the coastline. Les walked a few times to An-barra country guided by senior An-barra men so that they could show him important places. Together we made one trip to Balpilja Swamp with a small group of people (Balanda [white man] and Aboriginal). Dr Stuart Scougall and Dorothy Bennett (Figure 5.3) came with us. Stuart and Dorothy wanted to learn about the beautiful bark paintings that Aboriginal artists were painting at Maningrida. Another time, we walked along the beach with some An-barra owners. We walked from Maningrida to An-gartcha Wana. We camped for a few days at Gupanga. Then we came back.

Figure 5.3 Left to right: Three unidentified individuals, art collector Dorothy Bennett, Les Hiatt and Betty Meehan [formerly Hiatt] (Betty Meehan).

Just before we left Maningrida in 1960, Nancy Bandeiyama gave birth to a baby girl – Betty Ngurrpangurrpa (Figure 5.4). As she grew up, she became a dear friend and continues to educate me about An-barra life until the present day – sometimes by mobile phone!

Figure 5.4 Nancy Bandieyama with Betty Ngurrpangurrpa as a baby 1960 (Betty Meehan).

Some of you first met Rhys Jones in 1972. Rhys has passed away now. He came with me to live with you at Gupanga, Lalarr Gu-jirrapa and some other places on An-barra country. Rhys was an archaeologist. He wanted to learn about how home bases (rrawa) had been occupied by An-barra people for a long time in the past.

During the time we spent with the An-barra over the years (1972 to the present), we were shown many rrawa where living and deceased An-barra people had lived in the past. They also showed us and told stories about some places that are part of the Dreaming. Most of these sites contained some shellfish, animal bones, charcoal and, sometimes, some stone tools.

Scientists at ANU have used a radiocarbon dating machine to find out how old the animal remains are. To do this, they put small pieces of shell, bone or charcoal in the machine. Eventually, the machine produces answers that give some idea of how long ago Aboriginal people might have been living at the rrawa from which the samples came. Below, I will refer to this machine as the Dating Machine.

Rhys’ last trip to An-barra country was in 1999. He came with John Chappell. Rhys and John worked with some An-barra people, Betty Ngurrpangurrpa, Elva Jindjerakama and Stewart Rankin. They collected shells, bones, charcoal and stones from many places on An-barra land. They wanted to find out when An-barra people or their ancestors lived there.

Over centuries of time, as you may well know, the sea next to the Arnhem Land coast has moved in and out – sometimes huge distances – and, probably, sometimes destroying camp sites and other features of human occupation. You can find a complete list of all the dates in Chapter 3.

Rhys died from leukaemia in Canberra Hospital in 2001. This was a year after the work he and John carried out. Betty Ngurrpangurrpa went to see Rhys in hospital before he died. John Chappell died in New Zealand in 2018. Sally Brockwell has continued to work with me so that we could finish the work that Rhys and I started many years ago.

Next, we describe some of the rrawa that Rhys and I recorded and for which we have been able to obtain some dates telling us how long ago these rrawa might have been used by An-barra and/or other Aboriginal people. You can find more information about all these rrawa in Gun-guwarr.

Aningarra’s Camp

Aningarra’s Camp lies to the north of where we were all living at Gupanga in 1972–73. Michael Aningarra and his family were living on top of this site in 1972. The midden beneath contained the remains of shellfish from the sea and the mangroves – for example, an-dirrbula [Dosinia], jina-guronggura [Mactra] and an-jiwirriga [mussels], as well as charcoal from cooking fires. The Dating Machine at ANU told us that your old people were living here from about 300 years ago.

Gulukula mounds

As you know, these large mounds of shell are found on the western side of An-gartcha Wana. They are about one kilometre from the sea. Frank G. took me and Rhys to see them. He said they are Dreaming places belonging to Gulukula (dog). Gulukula piled up these mounds of shell with his paws.

Remains of shellfish from both the mangroves and the open sea were found in the site – mostly an-dirrbula but also some an-juwurrgiya and jina-guronggura. These shells were analysed by the Dating Machine, which showed that the old people visited this place about 900 years ago.

Guna-jengga rrawa

As you know, Guna-jengga is a coastal site where, most years, some of you installed a large an-gujechiya (fish trap) across the creek behind the first dune. Rhys and I have been there with you many times when you caught a big mob of fish and other sea food in the an-gujechiya. Once, when we were with you, you found a huge pile of turtle eggs buried on the beach!

Some an-dirrbula shells and charcoal from the rrawa were processed by the Dating Machine that told us that Guna-jengga has been used by people as far back as 500 years ago.

Gupanga wangarr an-dakal a-yurra (where the Dreaming white ochre representing diyama lies)

As you know, the diyama [Marcia] Dreaming place is located about 400 metres just north of Gupanga rrawa. Harry Mulumbuk and Barney Girrirrwanga sang a song about this site. Harry painted a bark painting depicting the diyama story. The Dating Machine has shown that this site is about 1,450 years old.

Ji-bena rrawa

I remember the day that Frank G. took Rhys and me to see the huge earth mound, Ji-bena, near Balpilja Swamp. On that day, he and other An-barra men with him, shot some wallabies and cooked them on the edge of the Ji-bena mound using some ant bed collected from nearby to cook them!

He described how, in the past, he and other An-barra people had visited this area when it was a good time to get ducks, geese and several types of plant food growing in the nearby swamps. He also described how, in the past, large groups of people had camped on top of these mounds to avoid the dampness on the plains, building shelters up there.

Some of you may also remember that when Rhys and I were carrying out our small excavation at Ji-bena, some An-barra people (e.g. Betty Ngurrpangurrpa) helped.

When we were digging, we found the remains of 19 different kinds of shellfish – but an-dirrbula was the most common. Bone fragments were also found in the excavation – mostly in the top levels – these were from turtles, mammals, fish (catfish and barramundi), reptiles and birds. Also, mostly in the top levels, we found some flaked stone tools, one bipolar stone core, some ground ochre and some artefacts made from haematite and sandstone. The Dating Machine shows that Ji-bena was first visited by the old people about 1,300 years ago.

Jilangga a-jirra

As you know, Jilangga a-jirra is a wet season rrawa located on the eastern side of An-gartcha Wana about two kilometres from the coast. When the airport at Jimarda was built, it was close to this camp, and people said, “This is too close to the airport, let’s move down to the beach at Yilan.”

Dates from an-dirrbula shells show that the old people were living at this place as far back as 1,200 years ago.

Jinawunya

As you know, Jinawunya is a rrawa on the western side of An-gartcha Wana where people went to collect shellfish, fish, Pandanus nuts, fibre for weaving, fruit and wood. A sample of an-garlajawurrga shows that people have been using this site for 700 years.

Jurnaka

This is the Belanggil area, near Gupanga. There is a mound there. The proper name is Dar A-yurrapa (“where the bamboo vine lies”) The word Jurnaka means “corner”, it’s where the river turns and goes up toward Gochan Jiny-jirra. Jurnaka is in a mangrove area on the western side of the mouth of An-gartcha Wana.

When Rhys and I were living with you, people went to this place to catch fish, stingray and different kinds of shellfish, including oysters from the mangroves.

A sample of an-dirrbula processed in the Dating Machine shows that people were probably using this place from about 400 years ago.

Lorrkon a-jirrapa (“where the lorrkon stands”)

As you know, Lorrkon a-jirrapa shell middens are located on the western side of An-gartcha Wana. Some stone flakes (tools) have been found on the ground at some of these sites. The an-dirrbula shells used in the Dating Machine show that these middens could be as old as about 1,400 years.

Mu-garnbal rrawa

As you know, this rrawa, which belongs to the Martay group, is situated on the eastern bank of An-gartcha Wana about 12 kilometres from the sea.

Rhys and I visited this place several times during our stays at Gupanga. I remember one day when we sailed there in that large dugout canoe called Mu-garnbal – with David B., Mary, Laurie and Jimmy.

The people there were hunting for native mice and goannas on the plain country. The mice live in the grass, and the goannas live in burrows. The goannas would all run out when they burnt the grass, and so would the native mice.

During the wet season, some Martay people camped at Mu-garnbal on top of a small shell midden. Shells from that midden, ana-mula an-ika [Terebralia], show that the old people lived at this rrawa about 3,700 years ago! This is the oldest archaeological site we have dated so far.

Muyu a-jirrapa (“where the fly stands”)

This is a coastal site made up of a linear midden on the seaward side and a shell mound behind. By 1979, the midden was mostly destroyed by a very rough sea. A date from an-dirrbula shells shows that both the midden and the mound were used by the old people about 1,400 years ago.

Ngarli ji-bama

As you know, Ngarli ji-bama is a home base situated on an inland dune on the eastern side of An-gartcha Wana. People lived there during the dry season. Some shellfish that could be jina-guronggura suggest that people have been using this rrawa for about 300 years.

Yuluk a-jirrapa (“stingray stands there”)

These shell mounds are located about one kilometre inland near Ngarli ji-bama home base – and are said to have been formed by the large stingray Yuluk. Some an-dirrbula shells and charcoal tell us that this place is about 600 years old.