1

Aboriginal traditions of food

Investigating Holocene dietary changes in southern Australia

Introduction

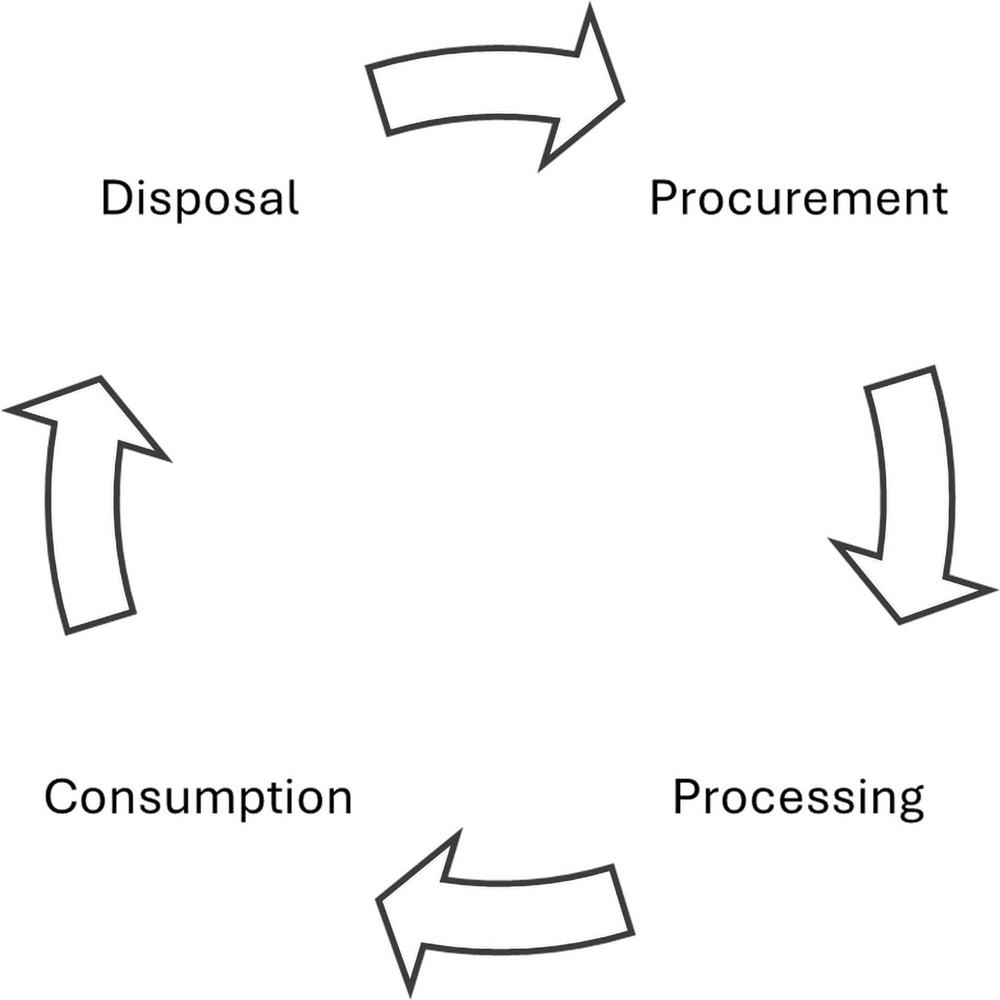

Australian Aboriginal culture is underpinned by long-term traditions connected with food – from procurement, to processing, consumption and eventual disposal. Food as an essential item could be seen as an output of the local environment, where any and all foodstuffs that can be sourced by an Aboriginal group comprise the basis of a “local” diet. Throughout this chapter, I consider that diet represents the long-term aggregate of food consumed over the course of decades, thereby accounting for the yearly cycle of food availability as the seasons changed, or shorter-term climatic effects (such as drought), which could have temporarily altered the availability of foodstuff. Diet should not be seen as static, but rather intrinsically connected and responsive to patterns that impact politics, culture and economy more broadly. Importantly, the complexities and subtleties surrounding any Aboriginal food system cannot be described by a simple framework listing the range of foods available within an ecosystem. Rather, continued cultural practices and social and oral knowledge, handed down through generations, combined with anthropological and archaeological investigations, allows insight into the complexities of the long-term food systems.

Australia as a continent has changed substantially over the course of human occupation. Global climatic change through the late and Terminal Pleistocene (40,000 years ago [ka] to around 9 ka) culminated in a major reduction in the land mass available for habitation (Williams et al. 2018). These changes continued to a lesser, but still significant degree through the Holocene (9 ka to present). From an ecological perspective, a changing climate affects three fundamentals which underpin the bioavailability of foods: rainfall, temperature and soil. Changes in the Holocene climatic patterns are generally described in three ways, with alterations in sea level (relative to our level today), temperature (which is described as warmer or colder than today) and rainfall (described as wetter or drier than today). These changes affected the environment and frequently caused geomorphological changes to soils and sediments resulting in changes to landforms. Continuous aeolian (wind), alluvial and fluvial (water) and colluvial (gravitational) processes moved, shifted, eroded and deposited soils, sands and sediments, altering soil landscapes and landforms, and thus the ecological communities that grew.

Concurrent with the environmental changes, throughout the Holocene Aboriginal demography, society and economies also changed (Lourandos 1997). Demography altered, with increasing population levels over the Holocene culminating in greater densities in the late Holocene (Williams 2013). Archaeological patterns (evident through materials such as lithics) suggest these changes had local and regional influences on human movements, use of Country, and trade mechanisms associated with goods and materials (White 2018). Through the late Holocene, Aboriginal societies exhibited increasing levels of complexity associated with aspects such as defined territorial boundaries (and the ability to move across these boundaries), locations used for habitation, spirituality, law, lore, belief, ritual, trade, descent and hereditary systems (Attenbrow 2006). Some of these changes can be identified through the study of material culture, such as stone artefacts (Hiscock and Attenbrow 2005; White 2017) or refuse from food consumption (e.g. middens comprising shell and animal bone) (Brockwell et al. 2017).

Some of these changes may be described within frameworks of “intensification”. Substantial debate into what intensification means for hunter-gathers often cites “increased productivity” or “increased economic output” becoming intertwined with any form of specialisation, diversification and innovation. Alternative models examine “labor investment [that] drives the engine of economic output, but that this comes at a cost of declining efficiency” (Morgan 2015, 198).

Within the southern Australian context, this chapter seeks to identify and examine some systems of late Holocene specialisation, diversification and innovation, and determine how alteration to food systems culminated in the diets consumed by Aboriginal men, women and children. Addressing these aspects should present further insight into the intensification debate, and notably the Australia hunter-gather/farmer debate (e.g. Morgan 2015; Sutton and Walsh 2021).

The range of foodstuff

Many aspects of Aboriginal peoples’ traditions, practices, society and economy are connected to their cultural landscapes, which in turn become imbued with meaning, law, lore, spirituality and practice. Food and foodways fall within this complex system, and therefore can be regulated in terms of access, processing, consumption and disposal.

Holocene period south-eastern Australia can be described as temperate, with a diverse array of waterways, flood plains, lagoons, swamps, plains, mountains and the ancient coastline formed during the Terminal Pleistocene. This landscape is rich with a diversity of ecologies, providing an extensive range of foodstuffs from both the land and water. It is generally thought that Aboriginal populations flourished throughout the Holocene, with a growth in population density underpinned by a dynamic system of understanding passed through intergenerational equity (e.g. Attenbrow 2010a; Morgan 2015). The ecosystem had sufficient long-term viability that allowed Aboriginal peoples to practice modes of subsistence where preferred foods could be consumed on a cyclical basis applying the minimum of labour expenditure. This is the opposite system from traditional agrarian systems practised elsewhere, where extensive labour had to be invested to obtain marginal increases in land productivity.

Generally, only limited information on food and foodways is included in literature on Aboriginal cultural heritage. Where information is included, details provided are frequently non-specific, without attention to regional variability, or consideration that diet could be influenced intra group by age, gender and/or individual group norms, customs, traditions or power dynamics. Discussion in texts can outline that Aboriginal groups consumed food staples such as “grain”, “yams” or “tubers”, but provide little detail on the mechanics or traditions connected with the social economies of the foodstuffs (e.g. Pascoe 2014, 19–50).

When examining the range of foodstuff within any territory, the breadth and variety of foods available for consumption means that classification of specific food staples is difficult. For instance, plant foods alone need to be considered under broad categories of fruits, seeds, exudates (e.g. nectar and gum), “greens” and everything growing underground (yams, tubers, rhizomes, bulbs and roots). Historical texts understate the sheer breadth and variety of foodstuffs available as part of Aboriginal traditional diets, which could originate from the colonial or European misunderstanding of Australia and its ecological systems. Many early (non-Aboriginal) accounts include only highly simplistic descriptions of Aboriginal food systems. For example, Watkin Tench (1789) provides one of the earliest accounts of the food practices of Aboriginal peoples local to Sydney. On foods consumed, he focuses on fishing, describing the fishing materials and methods and even the gender roles. While fish undoubtedly played a key role in the diet of coastal Dharug people, his observations insinuate an over reliance that in turn masks the resilience and adaptability of the Cadigal people of Sydney:

When prevented by tempestuous weather or any other cause, from fishing, these people suffer severely. They have then no resource but to pick up shellfish, which may happen to cling to the rocks and be cast on the beach, to hunt particular reptiles and small animals, which are scarce, to dig fern root in the swamps or to gather a few berries, destitute of flavour and nutrition, which the woods afford (Tench 1789, 260).

Written only three years after invasion, the unseen effects wrought by British land use practices impacted the traditional food bank around Sydney Harbour, likely played out through Tench’s observations. Many similar and often quoted accounts abound, serving only to diminish knowledge on the range and breadth of foodstuffs consumed. However, detailed anthologies such as Val Attenbrow’s (2010) Sydney’s Aboriginal Past contain a breadth of traditional knowledge on food and plant use, and systems of procurement, connected to processing methods. Some detailed works and compilations delve deep into procurement, processing, consumption and disposal. For instance, Berndt and Berndt’s (1993) compendium, A World That Was, contains very detailed accounts of food and food systems for the Yalradi on the Murray River, at Murray Bridge (South Australia). Works such as Philip Clarke’s (2012) Australian Plants as Aboriginal Tools provide an understanding of Aboriginal food systems from a botanical basis, with consideration of ecological communities, species lists, and a connection to edible and/or medicinal plants. An investigation into Aboriginal Biocultural Knowledge in South-Eastern Australia by Cahir and colleagues (2018) describes the knowledge of Aboriginal peoples, languages and cultures within their environments, with sections on water, plant and animal food, and presents food systems within a full sphere of cultural tradition.

Some works compile extensive food lists, including fauna, flora, fish and shellfish – these can be used to commence further investigations into local Aboriginal diets. Lists of foods represent baselines from which any associated traditions and complexity inherent within the food systems can be investigated. Food lists are generally static, reflective of a single time period; although archaeological consideration may be able to assist in describing changes through time. For instance, stratigraphical investigations of shell midden species composition can demonstrate a change in species present, which may be indicative of changing ecological conditions (e.g. the shellfish habitat of sand flats changing to mangroves). This type of contextualisation is regularly undertaken for technical objects such as lithics like the Eastern Regional Sequence (Hiscock and Attenbrow 2005) but rarely considered for food systems. Consideration of changes and alterations through time are important because Aboriginal economies, demographies and societies were/are not static, rather everchanging, unfixed and fluid.

Terminology and debate

A perennial discussion on the terminology associated with Aboriginal food systems exists within archaeology, anthropology, history and biological disciplines. The debate focuses on notions of “hunting”, “gathering”, “farming”, “agriculture” and “agrarian development”, where the terms used and applied have been associated with systems of social and civil “advancement” or a type of social hierarchy, suggesting that categorisation under one group is somehow better than another (Australian Archaeology 2021; Pascoe 2014; Sutton and Walsh 2021).

Whilst not the intent of this chapter to delve into the etymology of these terms or their implied usage, two key matters are apparent. Firstly, the terms are constructs from northern hemisphere systems of food procurement and production. Within this debate there appear to be few terms applicable to Australian First Nations peoples because the food systems across the continent and over many millennia are not directly comparable. For example, south-eastern Australia late Holocene systems cannot be compared to pre–Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) Pleistocene systems in northern Australia. Given this diversity within Australia, it is even more problematic to compare food systems here with those of Asia and Europe. Rather than seeking inappropriate geographic, cultural and temporal comparisons with European models of land tenure and farming, more focus should be given to understanding the unique and varied nature of Aboriginal practices and economies, and significantly, how these changed over time.

Secondly, the terms and terminology have focused on Aboriginal traditions connected with food procurement, and some modes of processing. The debate thus far has directed little thought or discussion towards food consumption or food discard, with all its inherent and nuanced complexities. Without considering the whole food system (from procurement through to discard), terminological discussions on Aboriginal methods of procurement appear incomplete.

These terms should be considered an impediment to recognising the complexity of Aboriginal food systems. Academic debate has started to move beyond the restrictive terminology with the adoption of the term “Aboriginal Biocultural Knowledge”, which is being used to “encourage cross-cultural awareness and to solve communication problems between Indigenous people and the broad group of researchers and public servants who are involved in land management” (Cahir et al. 2018, xix).

Holocene food systems

Broad regional investigations into long-term Holocene food systems can be undertaken through various archaeological methods. One technique is the physical investigation of archaeological sites and resources within a place or site. For instance, earth mounds (“habitation” locations comprising raised platforms of soil and organic material, often located in flood prone areas) provide a means for investigating adaptation to environmental and demographic change, and the connected Aboriginal social and economic responses to that change (Brockwell et al. 2017; Ó Foghlú 2021). An investigation into the composition of mounds can include the detail about the methods of food processing and cooking (including analysis of hearths and their carbon, ground ovens and clay cooking balls) and food disposal (through identification of bones, shell, seeds, pollen and spores) (Littleton et al. 2013; Westell and Wood 2014).

These modes of archaeological investigation are an indirect assessment of past diet – an examination of what is left behind, or what remains once foods have been processed, cooked and consumed. The analysis provides an understanding of the types (species) of foods consumed but does not examine complete or long-term diet. The outcomes present a snapshot of consumption, at a single point in time or place in the temporal and cultural landscape, not specifics on the proportions of vegetables, meats and seafood consumed. The analysis misses insight on gender or age preferences, inference on rules and traditions, and whether diet has changed over time. Bioarchaeological analysis involving an assessment of stable isotopes held in the organic and inorganic portions of bone may provide the basis for such interpretation. Isotope studies can be powerful with multifunctional analysis of the organic and inorganic portions of bone and tooth dentine and enamel, providing insight into not just diet, but also human migration between regions and countries (e.g. Adams et al. 2022).

For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on the stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen, held within the organic portion of bone collagen. All foodstuffs consumed contain stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. The ratio of carbon (C12 against C13) or nitrogen (N14 against N15) stable isotopes within a plant, fish, animal or shellfish species are constrained for that species by its specific habitat. Plants hold isotope values related to their photosynthetic pathway (C3 or C4), and/or the aridity of an area. Animals, fish and shellfish have enriched carbon and/or nitrogen according to their position within the food chain (their tropic levels), so that carnivores are enriched (more positive isotope values) compared to herbivores. If we analyse the stable isotopes of both carbon and nitrogen from a single species and present this data as a bi-variate plot, we can observe species-specific inter-regional patterning; for instance, kangaroos’ nitrogen values become more positive in relation to increasing aridity (Anson 1997). A baseline dataset for an environmental provenance can thus be established by analysing a range of plant and/or animal species within the whole food web (herbivores, omnivores and carnivores).

The modern-day food web of South Australia’s southern bioregions has been isotopically characterised, and the geographic distributions of species have been related to climatic zones (Owen 2004; Owen and Pate 2014). An analysis of the pollen record from wetlands and stable isotopes from kangaroo bones excavated from stratified rock shelters (Roberts et al. 1999) has shown that over the last 5,000 years, South Australia’s long-term climate was relatively stable. With this understanding, the baseline dataset (the bioregion’s characterisation) can be used to interpret stable isotopes retained in human bone collagen. For humans, the stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios reflect the food protein groups consumed over approximately a 10-year period. For instance, a long-term vegetarian would present distinct isotope values contrasted against a person who primarily ate seafood. Investigations into long-term diet have been undertaken for both South Australian Aboriginal (Owen 2004; Owen and Pate 2014; Pate and Owen 2014) and non-Aboriginal diets (Pate and Anson 2012), and patterns of migration (Adams et al. 2022; Pate et al. 2002).

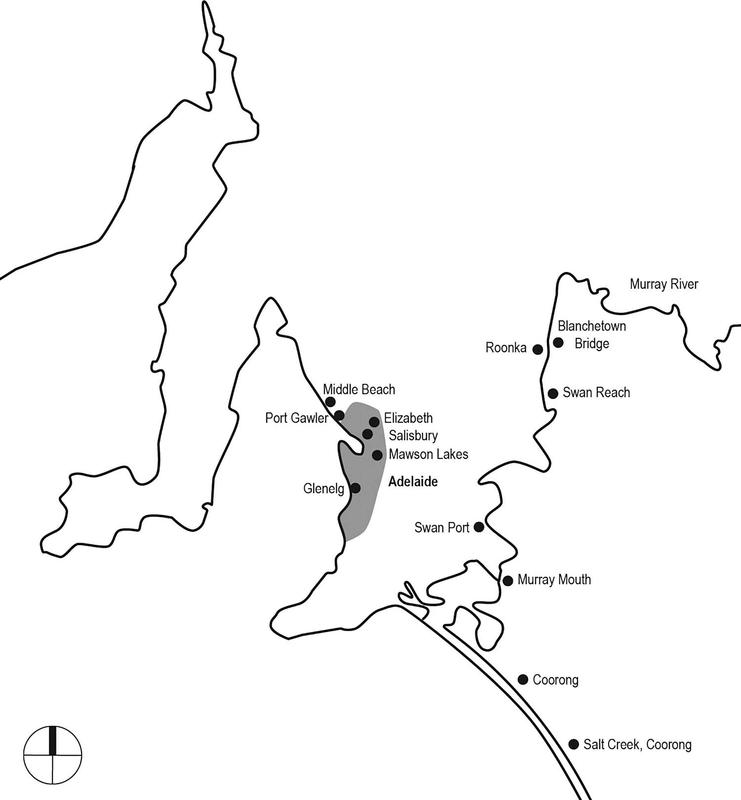

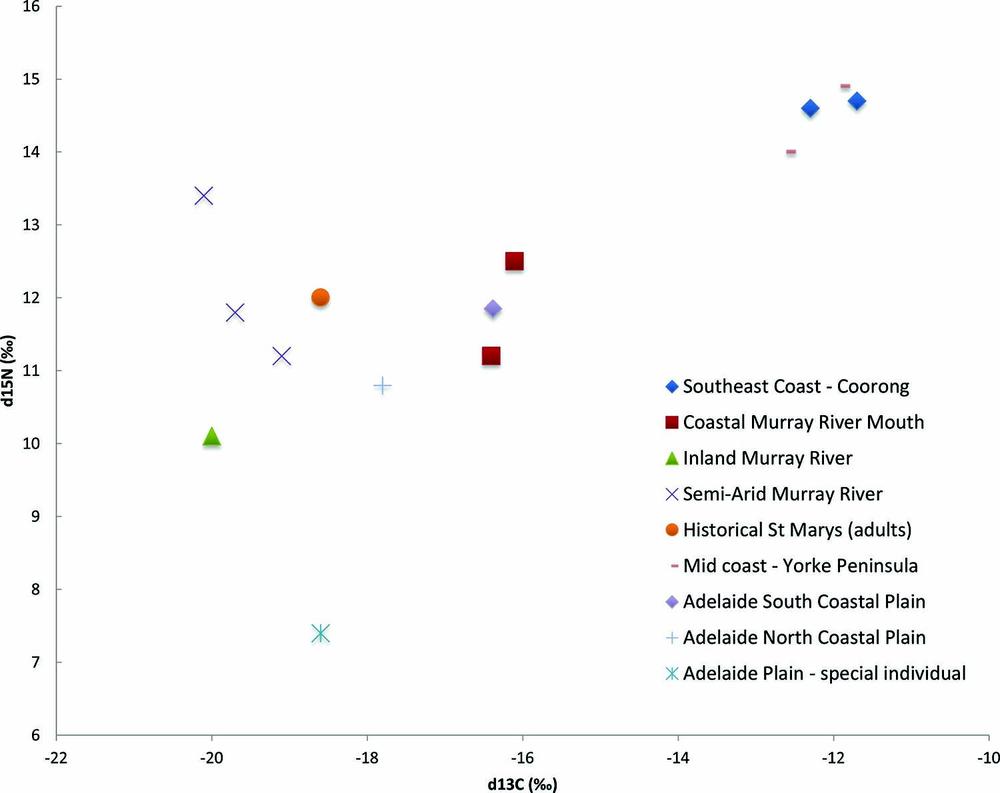

In South Australia, collaborative research between Aboriginal groups (broad regions for these groups is shown in Figure 1.1), including the Kaurna People (the Traditional Owners of the Adelaide Plains) and the Ngarrindjeri Nation (the Traditional Owners of the western end of the Murray, eastern Fleurieu Peninsula, and the Coorong), has provided insight into long-term connections between Country and each Aboriginal group’s ancient food system(s). The work was undertaken with the permission of the Aboriginal Traditional Owners, and involved analysis of ancestral remains that were either curated in a museum or were unintentionally disturbed through excavation works. Multiple individuals from each community group have been assessed for carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes (Table 1.1). The results are as distinct as each community – the diet consumed by each group reflected their Country and their bioregion (Owen and Pate 2014; Pate et al. 2002; Pate and Owen 2014). The distribution of groups as reflected by their diets is shown in Figure 1.2, and can be described thus:

- Coastal groups from the southern parts of South Australia ate large quantities of marine foods, to the extent that it formed the majority (>80 per cent) of their diet. These include peoples living on the Coorong.

- A very similar high percentage marine food diet was eaten by coastal peoples from the mid-north and Yorke Peninsula.

- Peoples living in a coastal setting at the Murray River’s mouth ate a diet with around 30 per cent seafood and 30 per cent meat, with the remaining 40 per cent terrestrial plant-based foods.

- Across the Adelaide region, there is a difference between diets north to south. The peoples in the south had a very similar diet to those at the Murray River’s mouth, which has a similar environment and resources. However, peoples living on the plains in north Adelaide moved inland away from the coast during winter, meaning they ate less seafood, replacing this food with terrestrial meat.

- Inland on the Murray, away from the coast, but not within the arid interior, the Aboriginal populations had a high dependence on foods from the riverine system. Around 50 per cent of their food originated from the river, or species that lived on the waters of the river, 20–35 per cent was terrestrial meat, and the total diet included 50 per cent plant-based foods (Owen 2004, Table 6-14, 266).

- Groups living inland in semi-arid areas, but near the Murray River, also had a greater dependency on foods from the riverine system, up to 70 per cent derived from the water catchment, with less terrestrial plant-based food being consumed.

- Finally, pre-colonial Aboriginal diets differed from the historical non-Aboriginal early (post 1836) population of Adelaide. The non-Aboriginal population consumed a diet of 60 per cent meat (e.g. beef or mutton), 32 per cent seafood and 8 per cent terrestrial vegetation (e.g. wheat and barley) (Adams et al. 2022, 4).

Figure 1.1 Approximate locations of South Australian Aboriginal groups investigated for

stable isotopes. Source: Owen and Pate 2014, Figure 1.

| Environment | Site/ Location | Rainfall (mm) | n | δ13C (‰) X ± SD |

Range | δ15N (‰) X ± SD |

Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Marine | Coorong | 500 | 27 | -11.7 ± 1.2 | -13.2, -9.6 | 14.7 ± 2.6 | 11.2, 22.2 |

| Salt Creek Coorong |

500 | 3 | -12.3 ± 0.8 | -13.2, -11.8 | 14.6 ± 2.0 | 13.3, 16.9 | |

| Coastal River Mouth | Murray Mouth Lake Alexandrina | 400 | 11 | -16.1 ± 1.3 | -17.9, -14.4 | 12.5 ± 0.9 | 11.0, 13.7 |

| Narrung | 469 | 1 | -16.4 | 11.2 | |||

| Inland Riverine | Swanport | 346 | 110 | -20.0 ± 0.8 | -21.6, -18.1 | 10.1 ± 1.1 | 6.6, 12.3 |

| Roonka Flat | 263 | 32 | -20.1 ± 1.2 | -22.9, -18.4 | 13.4 ± 1.2 | 10.9, 16.0 | |

| Blanchetown Bridge | 263 | 7 | -19.1 ± 0.7 | -20.4, -18.3 | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 10.9, 11.7 | |

| Swan Reach | 272 | 2 | -19.7 | -20.4, -19.0 | 11.8 | 11.2, 12.3 | |

| Coastal Plain | Salisbury | 475 | 1 | -18.6 | 7.4 | ||

| Historical European St Marys cemetery | 475 | 20 | -18.6 ± 0.8 | -20.1, -17.3 | 12 ± 1.1 | 9.8, 13.7 | |

| Hypothetical Adelaide Mound Diet | -18.9 | 10.9 |

Table 1.1 Summary of human bone collagen stable carbon and nitrogen isotope results from archaeological sites in the lower Murray River valley and Adelaide Plains (after Owen and Pate 2014, Table 1).

The studies have also identified individuals within an Aboriginal group who do not “fit” the broader diet of their group. Within one of the semi-arid Murray River groups there were 11 individuals (four female, seven male) who ate a diet comparable to the coastal Coorong region but had been buried inland (Owen 2004). The antiquity of these individuals (two were subject to radiocarbon dating) was the last 1,000 years. The reason for their burial away from the Coorong is not currently understood based on available evidence but could be connected with visiting the inland area for a social activity such as trade or ceremony.

A second example was the burial of a Kaurna “medicine man” or “sorcerer”. This individual consumed a distinct diet based on terrestrial foods, with an absence of marine protein (refer to Figure 1.2, “Adelaide Plain – special individual”). The location, mode and stratigraphic context of the burial, coupled with the stable isotope results, suggest this individual had a different diet to other Kaurna men, which was confirmed through knowledge held by Traditional Owners (Owen and Pate 2014).

Figure 1.2 Long-term dietary differences in South Australian Aboriginal groups (and a non-Aboriginal group), expressed through the stable isotopes of nitrogen and carbon.

The studies show that regional diets reflect bioregional food availability. This understanding is important because it describes a system from the mid to the late Holocene where both territories and diets were relatively fixed. Successive generations of each cultural group remained within the same bioregion, reinforcing and continuing their connection to a specific area. Individuals did not move sufficient distances for their long-term diets to become a blend of resources from multiple bioregions – they practised a form of semi-sedentism. Within their bioregion each successive generation continued to consume the same food resources as their ancestors.

However, we know that as the Holocene progressed, social complexity increased, as did demographic pressures. This means that in the late Holocene (the last 2,000 years) greater numbers of peoples were living within a smaller area but still needing and seeking the same food resources. For food systems, this means an increase in economic output and/or to seek alternative food sources. Alternative foods could have lower energy values and require greater search and processing time. We understand from the stable isotope studies that Aboriginal groups did not alter the proportions of food proteins consumed, meaning that people continued to eat the same foods. We also understand from the complexity of Aboriginal societies that procurement of foodstuffs was not the defining characteristic of Aboriginal societies; Aboriginal peoples did not undertake “agricultural” activities that required the majority of their time and energy (unlike agrarian systems).

This means that the economic output and management of food sources must have changed, evolved and become more complex in the late Holocene. New or changed technologies must have been implemented to obtain higher energy dense foods in greater quantities. Social systems must have evolved to define how food sources were treated and accessed. The remainder of this chapter examines these systems and changes through the four stages of the food cycle: procurement, processing, consumption and disposal.

The economy of food

Foodstuffs hold many levels of importance, from basic metabolic purpose, through to complex symbolic and ritual function. Recent academic debate has focused on the degree of agrarian capability that Aboriginal peoples may have held (refer to the terminology and debate section above and the forum in Australian Archaeology 2021; Pascoe 2014; Sutton and Walsh 2021). This debate focuses on Aboriginal societies around the point of colonial invasion (post 1788), and is generally absent of substance related to long-term changes through time (temporality), regionality (in that different groups had distinct diets, as described above), and does not delve into complexities associated with Aboriginal food economies (as will be consequentially described).

Outside of the terminological discourse, with reference to this topic, it can be stated that later Holocene changes within Aboriginal social and economic systems allowed the development of complex food extraction methods (e.g. Burrawang (Macrozamia) extraction), new technologies and methods for food procurement (e.g. Asmussen 2010; Attenbrow 2010, 76– and underpinned a form of intensification that provided the basis for new subsistence strategies such as habitation on mound sites in wetland and flood prone areas (Coutts et al. 1979; Westell and Wood 2014). However, the outcomes from the stable isotope studies show that over the last 4,000 years, the baseline composition of Aboriginal diets in southern South Australia did not vary – that is, Aboriginal peoples continued eating the same foodstuffs, in approximately the same baseline protein proportions. Through the mid to late Holocene, significant changes to the environment and Aboriginal societies did occur. Agents that influenced change included climate alterations (precipitation and temperature) and changes to landmasses, vegetation communities and shorelines.

The “farming” debate, along with several academic projects, have identified patterning within Holocene Aboriginal subsistence strategies. The stable isotope investigations identify that the changing strategies relied on a consistent and stable source of food – groups did not switch from consuming marine to land-based protein. The identification of changed subsistence strategies, which maintain the same food consumption pattern, is an important distinction. It means that Aboriginal peoples needed to alter aspects of their food procurement strategies. This could include the commencement of practices that led to improvements in wild food yields, management of land areas, and soils, so that foods would consistently be (seasonally) available (Cahir et al. 2018, 59). Methods for obtaining large quantities of a foodstuff were developed, along with techniques for food preservation, storage and accumulation of food surpluses (Berndt and Berndt 1974, 46, 1993, 74–96).

In itself, the retention of food surpluses allows for the development of social systems with large gatherings of people. Non-Aboriginal accounts (following invasion) record many lengthy gatherings with up to 2,000 Aboriginal peoples. Food can be seen to support the social and spiritual aspects of life, which often took precedence over the food system. For many Aboriginal peoples, it was often not the primary factor underpinning the system of economy, it was subservient to other facets of life. It can be viewed as both essential and non-essential; essential in that one must eat to survive, but non-essential in that sufficient food could be quickly obtained within most environments. Maintaining these systems therefore required complex (group-specific) frameworks that function on several levels. There needed to be systems and law which prevented over-exploitation, created understanding of yearly food cycles and availability, connected peoples to their Country, and facilitated the long-term intensification of food economies.

The economy surrounding Aboriginal food systems can be described in four parts: procurement, processing, consumption and disposal (Figure 1.3). Each of these parts may hold significant complexity, underpinned by a variety of local traditions and the regional environments. These systems changed and evolved over time; therefore, when describing any part of the food system, consideration to a temporal framework must be given. The remainder of this section will examine the four parts, outlining some of the complexities.

Figure 1.3 The Aboriginal food system with four interconnected aspects. Each aspect changes over time and by social group.

Procurement

The initial part in the food system is procurement, or the systems, mechanisms, methods, rules, laws and considerations which underpin obtaining food prior to its processing and consumption. Systems connected with procuring (obtaining) food were complex and varied from clan to clan. The rights to access food, strategies engaged to obtain food, methods and techniques of food collection (separate to processing, which is the next stage in the food system), and technologies associated with food procurement all evolved and changed through time.

Within hierarchical Aboriginal societies, access to food could vary by social position, and food restrictions were often linked with totems and/or periods of initiation. Totems could be associated with creation mythology, where animals, etc., came about as a consequence of land formation, events or division of other larger animals. At birth, many Aboriginal peoples are connected to or assigned a totem, which was frequently intertwined with social systems such as hereditary rights or future marriage systems. Totems are frequently land fauna (from kangaroos to lizards), birds (such as eagles) or sea creatures (from fish to turtles), attributed with special powers for the person given the totem. Most societies had restrictions on hunting or eating totems, resulting in a special and symbolic relationship (refer to comments in Berndt and Berndt 1993; Clarke 2012).

Outside the totemic system, there were also social, gender and age restrictions on certain foods, such as the descriptions of the Ngarrindjeri people (South Australia) by Berndt and Berndt (1993, 122–30). For instance, in some groups following initiation (novice) males had a list of taboo foods, which if consumed, would lead to punishment through a supernatural force, resulting in effects ranging between grey hair, ugliness, disease, hiccupping, stomach upset, sores and ulcers, to the growth of a large tusk-like appendage from the mouth! Pregnant women could also be subject to food taboos, notably food thought to affect the foetus. Restricted foods could include those high in fat, certain roots and vegetables and foods such as crabs and crustaceans thought to lacerate the foetus. There could also be restrictions on consuming food collected by novices during their initiation period. The extent of taboos and restrictions demonstrates the extensive range of foods readily available and indicates that many alternatives could be obtained. In the instance of the novice, the restriction likely had a practical purpose, making the novices expand their repertoire of skills – perhaps restricting them to “difficult” to obtain foods encouraged proficiency in collection.

In some places, the right to access food could be “owned” by an individual, a family or groups within a clan. This could include restrictions on access to land areas such as yam beds, wetlands, parts of rivers or coastal zones with high biotic quotas. These restrictions could be maintained through systems of privileged and hierarchical control with hereditary intergenerational transfer of ownership. It is likely that ownership restrictions changed over time, notably as the environment and landmasses changed through the Pleistocene and Holocene. Patterns in access and ownership can be examined archaeologically through stratified archaeological sequences and/or analysis of data from across many archaeological sites (e.g. Owen et al. 2022).

Strategies for obtaining food must be considered from a point of temporality. This is because through the Pleistocene and Holocene the environment changed greatly, as did the location of Australia’s coastline. Intra-region there were significant changes to procurement strategies through time, and at a single time point there could be large differences between adjacent clan groups. If one considers Australia’s coastal capital cities (Adelaide, Brisbane, Darwin, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney), the traditional subsistence base through the Holocene would be considered coastal or salt water, likely with a high percentage of seafoods. However, prior to late Pleistocene sea level changes, each of these locations would have been 20 km or more inland (e.g. Lewis et al. 2013), meaning these places were not on the coast, and coastal foods were not accessible. Temporal considerations must therefore determine the period and landmass location for any description of the subsistence base such as Pleistocene versus Holocene, and coastal, riverine or inland.

The examination of strategies through the Holocene requires large quantities of archaeological data, which can reveal changes in social and demographic patterns (e.g. Attenbrow 2006). Within these systems it becomes apparent that regional or clan specific strategies have start and end points. One widely known aspect of Aboriginal land management practices is “fire stick farming”, with low intensity bush-burning used to control vegetation understories for many different purposes. These purposes could include: the need for certain flora species seeds to be fire germinated – resulting in new vegetation growth, which created both new plant resources and also attracted fauna to graze on new shoots; management of land for habitation purposes – clearing a campground prior to occupation (Clarke 2012); and, hunting methods – where game animals could be driven by fire towards waiting hunters or traps. It is thought that the maintenance of small-scale habitat mosaics increased small-animal hunting productivity, and could be linked with more sedentary Aboriginal societies, which had focused subsistence economies (Bird et al. 2008).

Food subsistence strategies were frequently based on resource availability by season (seasonality). Specific details connected with seasonality are often held through local traditions and provide a basis for understanding and interpreting late Holocene modes of subsistence. Aboriginal calendars described between six and 12 seasons.

Traditions that described the seasons vary between groups, and are distinguished by many aspects, such as the movement of the stars and other celestial bodies, the growth of particular plants, the appearance of various creatures (e.g. fish species or the migration of whales) and alterations to weather patterns. The Kaurna people (South Australia) describe several seasons (after Hayes 1999), including a hot season (Woltatti) or hot north winds that blow in summer (Bokarra), time for building huts against fallen trees (Wadlworngatti) or when the Parna star appears in autumn (Parnatti), icy-cold winds from the south west (Kudlilla), and when the Wilto-willo star appears in spring (Wullutti). Kaurna people responded to these seasons with localised movement between coastal and inland places, described through oral evidence and distinguished through stable isotope studies (Owen and Pate 2014). Understanding the traditions and influence of seasonality on Aboriginal subsistence strategies across the Holocene and Pleistocene would require an understanding of localised changes to ecological communities, weather patterns (including rainfall) and landmass alterations.

The east–central Australia exchange and trade network concerns a diversity of items, raw materials, symbolic items (songs, dances, stories) and manufactured goods (McBryde 1997). Trade strategies involving processed foodstuff (bone and shell items), more local movement of processed foods and the extensive movement of the tobacco/narcotic pituri, demonstrates that “food” could be a valuable commodity and a part of regional networks. The growth, processing and consequent trade of pituri has been charted through the centre of Australia, covering thousands of kilometres. Trade of food resources also occurred over shorter distances and was linked to methods of food preservation. Food rationing could also be used as a method of conserving limited supplies of certain higher value foods, for instance honey would be collected from native beehives, but only part of the honeycomb would be removed, retaining enough for the bees’ consumption. Rationing was also linked with “propagation” of foods such as yams, which, when sufficient, were left for new growth to occur thereby ensuring a future crop.

The methods and techniques used to procure food altered by region, the dietary base, and temporality. Archaeological studies have identified many significant developments in methods and techniques through the Holocene. The methods evolved in complexity, allowing either for an intensification in collection of food, or gender specific modes of gathering. At the end of the Holocene, within the alluvial wetland areas of South Australia, NSW and Victoria, Aboriginal groups started living on raised mound sites (e.g. Westell and Wood 2014 review mound sites across the Adelaide region). These artificial mounds raised people above wetland areas, providing dry platforms for habitation activities in otherwise flood prone landscapes. Mounds likely served a range of economic and social functions, as locations for habitation, deliberate markers in the landscape, places where specific plants could be grown, locations used for human burials and by allowing the occupation of previously marginal landscapes during period of inundation. The mounds could be clustered in small groups, providing spatial separation between individuals, families and activity areas. Most landscapes with mound sites have a high biotic quota, and the mounds were frequently built up from cooked organic materials, including major food source plants such as Typha (e.g. Coutts et al. 1979). The occupation of the mounds may have been seasonal, responding to seasonality and the growth and presence of major food resources at certain points of the year. The production of mounds and their occupation appears to be restricted to the late Holocene (the last 2,000 years), demonstrating a significant shift at this time in terms of economic land use strategies, perhaps responding to other social factors such as population increases and territorial boundary closure.

Through the late Holocene, we know that some food collection techniques changed. For instance, in the coastal Sydney region, women manufactured small fishhooks, used to fish on a line from bark canoes on the harbours (Attenbrow 2010b). These activities only commenced in the last 1,000 years and demonstrate a significant localised shift in gendered subsistence patterns. Increasing complexity in the methods and techniques used to “hunt” animals often focused on passive techniques, or techniques that guaranteed food in a short period of time. Development of complex fish traps and fishing nets, eel traps, and bird and animal traps allowed land, riverine and sea animals to be caught, without the need for direct human involvement in the process. Some techniques became so sophisticated that an industry around the manufacture of large bird catching and fishing nets developed within groups such as the Ngarrindjeri (in South Australia, Berndt and Berndt 1993, 92–103). For instance, Ngarrindjeri hunts deployed nets over 10 m long to capture large flocks of small birds from wetland areas. These were consequentially processed and could be stored for future consumption.

This short review provides an overview of complexities connected to the procurement of food. It demonstrates how social lore, law and tradition governed how food could be collected. Food seasonal availability and an understanding of resource scarcity were equally important.

Processing

Once a food was obtained, the food systems connected with processing commenced. Many foods could be eaten raw, particularly plants and berries, and the only processing required was to remove adhering vegetation, or cracking kernels to access nuts. However, as for systems of procurement, there could be a complexity connected with processing, and these changed considerably through deep time. Continent-wide research into the process of Pleistocene colonisation has identified that a general set of plant processing techniques was holistically adopted. As Aboriginal peoples moved over the Australian landmass, the generalist practices were tailored to different regions and biotic resources. During the mid Holocene, multiple new behaviours were adopted in different places, allowing for specific regional adaptation and increased local complexity (Denham et al. 2009).

Levels of complexity could range from needing to properly cook a food, to specific processing and treatment of the food to render it edible, removing toxins before cooking. Further complexity could be introduced through gendered roles in processing, to permissions to process food governed by hierarchical systems. Temporality also needs to be considered, as modes of cooking evolved and advanced over the Holocene, with new techniques allowing complex starches in tubers to be broken down into edible carbohydrates. Descriptions of processing can be divided into preparation and cooking.

Preparation of plant resources was undertaken to break down plant material and/or render it safe for consumption. The methods of preparation included heating, placing plants in solutions (such as salt water, or running fresh water), fermentation, adsorption (by clay and charcoal), curing (changing pH by the addition of ashes or acids) and drying (Clarke 2012). Physical processing included grating, grinding, pounding and (in very cold climates) freezing (Rowland 2002). Discussion here focuses on some of the more commonly known methods that were used across large parts of Australia for long periods of time.

From the mid Holocene on, Aboriginal peoples across the drier and hotter parts of Australia practised seed collection, followed by a process of winnowing and grinding. Evidence for seed grinding is frequently identified within an archaeological context; handheld grinding stones, and grinding patches and hollows in bed rock, or portable sandstone grinding stones provide evidence for these practices. Many different plants (and animals) were ground to produce flour or pastes, which would be cooked before consumption.

Obtaining sufficient grain (seeds) to manufacture damper required an understanding of seasonality associated with grass ripening. In some parts of South Australia, New South Wales and Victoria, Aboriginal peoples practised both deliberate spreading of wild grass seeds (for future crops) and collection of surplus grain, with methods of dry storage used to save grain for periods of the year when it would not otherwise be available (including storage in modified tree hollows and woven baskets). During seasons of abundance the surplus provided a means of increased sociality, with evidence for human movement between territories facilitated because of the surplus (Macdonald 2017, 82). Evidence of movement of foodstuff can be detected archaeologically. For instance, the process of grinding seeds and plants on grinding platforms with stones leaves behind spores, pollen and starches. Careful sampling from the surface of the stone can recover these food remains, which may be identified through microscopic analysis. This provides the basis for understanding plant use (not just for food but also medicinal use) and the movement of plants through a landscape – where plants can be moved long distances before being processed (e.g. Owen et al. 2019).

Many nuts consumed in large quantities are toxic or noxious. Knowledge of nut preparation techniques to make these edible has built up regionally across Australia. Processing systems for toxic and noxious nuts including collection, removal of flesh, cooking (in an oven), cracking shells to remove kernels, leeching, drying and grinding or pulverising, followed by preparation into an edible item. The period required to produce an edible product could be days. However, experimental archaeology has shown that each stage was relatively quick and, most importantly, the outcome was a food resource high in energy (Tuechler and Cosgrove 2014).

Importantly, the effort and time expended to obtain high energy source foods like nuts and seeds was relatively low compared against the effort required to collect and process these foods. This is the case for cycad seeds (Macrozamia), which is an example of an important food that required traditional processing knowledge. Macrozamia are one of 11 genera of Cycadales and are endemic to Australia. Macrozamia’s starchy kernels (mega-gametophyte) are eaten, but require the removal of toxins to render them safe. Aboriginal peoples have a long history of Macrozamia processing; archaeological sites containing the processed remains of the internal hard stony shell (sclerotesta) have been dated back to the Pleistocene, and archaeological research has demonstrated increased consumption of Macrozamia through the early to mid Holocene (Asmussen 2010).

A riverine to semi-arid inland food which required processing before consumption is nardoo (Marsilea drummondii). Nardoo is a perennial aquatic fern, with underground stems (rhizomes). The plant produces a hard fruit called a sporocarp, which can be collected but must be roasted before being ground. It produces a yellow flour that can be made into a dough. If the fruit is eaten raw, the thiaminases (an enzyme) present causes vitamin B1 deficiency (beri-beri) – untreated, beri-beri can result in death. This was the downfall of European “explorers” Burke and Wills, who in 1861 died in the South Australian outback after eating large amounts of unprocessed nardoo (National Museum of Australia 2023).

The preparation and cooking of foods was specific to the actual food. Species-specific techniques rendered the food more appetising if prepared and cooked in a particular way. It also allowed for personal and culturally defined taste preferences. Food preparation considered not just the food, but the secondary products which came from the animals, fish and birds. Animal skins needed specific treatment if they were to be used for consequent clothing production. Likewise, bone, tendons and sinew from animals needed to be prepared and removed in specific ways if intended to be used once the meal was consumed. For certain Aboriginal groups, particular species may have gender or “magical” restrictions that necessitated very careful preparation and disposal of particular parts of the creature.

Each species would have a unique way of being prepared and cooked. For instance, the Ngarrindjeri’s technique for preparing a Murray cod was elaborate and resulted in 10 separate portions which would be shared within a family; the person who caught the fish rarely took the best part for themselves (Berndt and Berndt 1993, 105).

The methods of cooking were varied and could be tailored to each species. Sydney’s Pleistocene Aboriginal populations used small flat pieces of sandstone as heating or cooking plates, presumably placed over the fire to heat the stone. The prevalence of these sandstone items within the archaeological record varies through the Pleistocene, with increased use either side of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), disappearing altogether in the Holocene (White 2018).

In the later Holocene (the last 1,500 years), Aboriginal peoples in south-east and southern Australia developed cooking methods using ground ovens. This specialisation allowed for slower and longer cooking periods, thereby providing a means to cook larger animals. A by-product of the cooking process itself was a large amount of organic plant material and cooked clay, which was used to form mound sites (Coutts et al. 1979; Westell and Wood 2014). To cook in a ground oven, fires were made within an excavated depression (the size and shape of the item to be cooked). Cooking stones or specifically manufactured clay cooking/heating balls were heaped onto the coals within these depressions. Further fires adjacent to the depression heated further clay/stone balls. Once the fires had died down, grasses (and edible plant material, such as Typha) were placed over the coals, food was placed on the grass, and further cooking stones/clay balls packed over the top. The oven was sealed with the excavated spoil of soil or sand. Over one or more hours the oven would cook the food at a temperature controlled by the quantity of cooking clays/stones. A steam method could be introduced, with a hole poked into the side of the oven and water poured into the centre. Once cooked and cooled the oven would be broken open and the food removed for consumption.

The manufacture of the clay cooking balls appears to reflect a specialised industry. To make these items suitable, clay needs to be obtained and then tempered with a grit/gravel/sand or plant chaff. The balls must be air dried before being cooked themselves at a defined temperature for several hours. Simple lumps of dry clay cannot be used in a ground oven because these explode or disintegrate, contaminating the food. Use of ground ovens represents an economic production system with three steps: firstly, the manufacture of cooking balls; secondly, the development of methods to obtain the animals, fish, birds and vegetables; and finally, development of specialised cooking techniques.

The food production economy in the late Holocene focused on processing methods and the creation of food surplus. This surplus was generated through the preservation of vegetables, smoke-drying of animals and fish, and the preparation of oils (Berndt and Berndt 1993, 109–16). Food surplus was important for three reasons. Firstly, during the colder and wetter winter months half the number of food items were available (to groups such as the Ngarrindjeri or Kaurna, across South Australia) compared to the summer months. Food surpluses could be used to even out the availability of wild foods over the year (Owen 2004, 89–91) and provide reliable long-term food sources. Secondly, food surplus allowed for increased population numbers and provided a context for social closure with firmer boundaries between groups (Lourandos 1997) – it provided one means to change subsistence and economic activities. Food surplus became a part of the trade network, and the necessity for traditional trading expeditions. Thirdly, the movement of people across Country and between groups throughout the southern parts of Australia is well known for purposes of trade, exchange and ceremony. Having food to take on these journeys would have been vital and could only be achieved through a food surplus.

Consumption

Once prepared, whether that be simple preparation of raw food, cooking, elaborate processing or preservation, food would be consumed. Consumption systems depended on both the type of food and whether the food was to be consumed by an individual or group of people.

Individuals consumed raw, simply processed or preserved food throughout the day, often collecting and eating fruits and berries, or foods carried from the camp, such as smoked fish. This type of simple consumption did not require much consideration or post-consumption disposal of waste.

Individuals could also consume larger meals, which necessitated consideration of consumption systems. For instance, it was recorded by colonists that the Cadigal women (the people on the southern side of Sydney Harbour) fished on the harbour from small canoes using a line (Tench 1789). The canoe would hold a small clay pad, on which a fire could be built. Women would catch, process, cook and then eat fish whilst fishing. However, the purpose of fishing was to collect food for more than one individual. During periods of the year when fish were less plentiful, or adverse weather conditions made fishing became a difficult task, women needed to balance the quantity of fish caught against their own consumption. During larger social gatherings, with over 1,000 people, perhaps from multiple clan groups, the systems of food gathering, cooking and sharing could become very complex.

This example introduces the main consideration underpinning consumption systems – how food was divided and shared. The intricacies of this system mean they were socially based and probably varied between clan groups across Australia. Consideration of food division depended on the type of food, for instance different rules existed for certain fish, kangaroo and birds. Some simple hierarchical principles existed, where elder males (and in some cases females) would hold rights to the highest protein or fat portions of a meal. Conversely, for some food items, the “best” portions were reserved for the youngest members of the clan.

Division of food commenced with preparation (as described above) and, once cooked, the person responsible for preparation and cooking would divide and distribute the food. For instance, bandicoots, possums or quolls would be dismembered after cooking. A cut on the back was made either side of the tail, which was given a sharp pull to remove it. This meat was regarded as the sweetest and given to the children. The spine was then cut along its length and bent until it broke. Three cuts either side of the spine divided the meat into seven portions, one being the head (Berndt and Berndt 1993, 100 and 102). Portion size was controlled so each person received an equal and fair amount. Portion allocation also considered disposal requirements, with certain parts of animals subject to strict taboos and superstition.

Finally, Aboriginal peoples occasionally consumed items with no nutritional value, but as items for medicine, digestion or superstition. Certain types of clay or carbon could be eaten to aid digestion or to settle an upset stomach. Consumption of small stones (gastroliths) could occur for purposes connected with magic or ceremony, with certain items thought to possess properties that imparted special powers or values. One commonly known non-food item that formed an important part of ritualistic life was the tobacco/narcotic pituri. Providing a hallucinogen effect, this plant is known to form an important part of higher men’s business for certain Aboriginal groups.

Disposal

The final part of the food system is disposal – the process of removing the food wastes once consumption is complete. There were multiple ways to dispose of food waste, some of which were linked to specific production economies. Archaeologically, some of these disposal systems can be identified and form deposits which are the focus of research. Discard was either intentional or unintentional. Unintentional discard may be described as random and unpremeditated. This could include discard whilst walking, or actions where discard would not hold implications for waste management, such as throwing scraps to camp dogs, thereby entirely disposing of any food wastes.

Intentional discard is a process where discard becomes a deliberate action, in some instances governed by rules and traditions. Intentional discard could include collection and replanting to generate new/additional food sources, collection and re-use of materials for future manufacture into secondary products, deliberate disposal such as burning in a fire to avoid issues connected with superstition or magic, and deliberate waste management strategies, such as accumulating waste in a specific location to form a waste dump, mound, heap or pile. The final consideration for disposal of “food” were processes connected to human waste management (notably faeces), generally in more permanent camping locations or during large gatherings.

Replanting and redistribution of foods (uncooked but sometimes processed) was a noted method for deliberate propagation of plants, especially seeds and tubers. In parts of NSW where seeds were a food staple used to produce a flour for pastes and dampers, Aboriginal Elders describe the (continuing) practice of slowly dropping grass seeds from their hand as they walk through specific parts of Country. This aids the distribution and next season’s growth of the plant, and expands the area with food sources. Locations chosen for seed distribution could be specific, connected with shallow slopes above creek systems, where it was known that the seeds would grow, and can still be collected.

The food cycle associated with wetland and dryland plants was deliberately managed to generate ongoing growth. The production economy could be associated with digging soil beds, turning over nutrient-rich alluvial soil, splitting and replanting tubers. Stands of dense plants were thinned out, reducing the competition for light and nutrients among the remaining plants, thereby improving their growth (Gott 1982). In some places during the late Holocene, wetland plants formed a staple as a carbohydrate source. Important food species included cumbungi or bulrush (Typha domingensis and T. orientalis), marsh club-rush (Scirpus medianus), and water-ribbons (Triglochin procera), that grow abundantly in waterways. Wiradjuri (NSW) traditions describe how specific parts of each important waterway was cared for by an individual who would have responsibility for the resources and maintaining water flow through a certain portion of the creek (Macdonald 2017, 76). The responsibilities included management of reeds, grass, trees and other plants. These systems are frequently connected with “caring for Country”, the ecological management of land with a symbiotic relationship between the land and Aboriginal peoples. These practices are linked to disposal because they represent Aboriginal peoples returning plant material to regrow or generate new growth.

The process of caring for Country extended into waste management. Some strategies involved a deliberate process of collecting waste products in a predefined area. Collation of waste could be both functional (such as allowing food remains to decay and rot in specific locations, thereby containing vermin or flies) and also symbolic (creating landscape markers or preventing misuse of food remains).

The accumulation of waste in a dump or mound could result in the formation of a raised platform. For many Aboriginal groups, these platforms or mounds were both functional and held symbolic meanings. The functionality of a mound is associated with the raised nature of the platform and the flat upper surface of the mound. Across Kaurna Country (now called Adelaide), mounds were most frequently constructed in clusters within wetland or flood zones. The mound’s height above any flood waters allowed habitation and other cultural activities to occur in a dry setting. Clusters of mounds were grouped together, each mound holding a specific function, akin to the layout of a traditional camp on an open plain. The mounds were typically quite large, oval to circular, and could measure 50 metres in diameter. Some mounds on Kaurna Country were over one metre in height. Landscape patterning is evident within the distribution of Kaurna mounds, and the mounds functioned as visible markers in the cultural landscape. They were identifiable locations which designated boundaries, movement corridors and specific places. In some instances, they represented “hold points” which visitors from other clans could not pass until provided with permission or a taken by a guide.

Mounds are archaeologically rich, composed primarily from decayed organic materials – fibrous plant remains, and inorganic materials – clay cooking balls and carbon (Coutts et al. 1979; Westell and Wood 2014). Mounds frequently contain the remains of ground ovens, and some served as burial locations, occasionally containing multiple interments. Radiocarbon dating of materials from mounds suggests that most were constructed in the late Holocene (the last 1,500 years). Functionally, the mound site can be attributed to the need to extract more resources from a small territory, or an area that was perhaps previously marginal in terms of resource extraction. Notably found within wetland areas or on alluvial flood plains, the mounds are connected with locations that have a high biotic quota and year-round food resources. Mounds provided a dry space within the wetland zone and therefore increased the habitable portion of Country. They provided a location to collect and process food from wetland areas, reducing the time required for hunting and gathering activities.

Another archaeologically common type of waste disposal rubbish dump is the shell midden. Frequently found along the foreshores of Australia’s current coast and inland waters, a midden is an accumulation of consumed shellfish, coupled with animal bones, fish ear bones (otoliths), carbon from fires and hearths, and perhaps discarded stone artefacts. Middens are archaeologically important because, if stratigraphically excavated, the shellfish remains can provide all manner of information on consumption patterns over time. Midden composition allows us to understand the type of shellfish that Aboriginal peoples consumed and, when coupled with stable isotope analysis of the shell’s calcium carbonate, the period during the year of consumption. Middens can be deep deposits; sometimes metres of shell have accumulated. Analysis of species composition with depth and time control can identify changing local environmental conditions, such as a change from a sandy beach environment to an anerobic mangrove environment. Middens could also be markers in a landscape, defining where certain social and economic activities occurred, although their ubiquitous nature means interpretation of such function needs to be connected to local traditions.

Many Aboriginal societies also practised different forms of sorcery and magic and held numerous superstitions – including in the manner of food disposal. Each group could have its own traditions, often connected with hierarchy within the society, and notably, higher initiated people. Sorcery has been described as an ever-present phenomenon, and individuals practiced certain traditions connected with food disposal in an effort to avoid magic and the possible dangers from its effects. For instance, for the Ngarrindjeri peoples (South Australia) it was an established practice to dispose of certain food remains following consumption:

Every adult blackfellow is constantly on the look-out for bones of duck, swans, or other birds, or of the fish called ponde (Murray cod), the flesh of which has been eaten by anybody. Of these he constructs his charms. All the natives [sic] therefore, are careful to burn the bones of animals which they eat, so as to prevent their enemies from getting hold of them; but in spite of this precaution, such bones are commonly obtained by disease-makers who want them. When a man has obtained a bone – for instance, the leg bone of a duck – he supposes that he possesses the power of life and death over the man, woman, or child who ate its flesh (Taplin 1879, 24).

One type of Ngarrindjeri sorcery, called Ngadungi, involved obtaining leftover food from the intended victim. The aim was to inflict an ailment on the victim, and the nature of the ailment depended on the type of food remains obtained. Predominantly for the Ngarrindjeri, food remains used in sorcery were often from birds or fish, rather than land-based animals (which could reflect the basis of their diets inland on the Murray River or coastal on the Coorong). Collecting a splinter of bone from a duck’s head could be used to cause headaches; skin from the duck’s wing caused a diseased arm; or skin from its body could result in internal diseases. The process of magic was long and involved engaging a sorcerer, who would take the food remains and prepare a sorcery object. This object was then placed under the intended victim’s hut or in their belongings, eventually making them ill (Berndt and Berndt 1993, 258–9).

Beyond magic and sorcery, the products from plants and animals were vital commodities, essential within many Aboriginal production economies. Many parts of animals, from the skins, bones, fats, sinews and tendons were used as secondary products. Plant material not consumed was manufactured into twine, ropes and strings – and in turn manufactured into ropes, nets, baskets and ornaments. The skins and pelts for many land-based animals were carefully collected prior to cooking the animal, and those without blemishes or tears selected for further processing.

The Ngarrindjeri processed skins to make them soft and pliant. The process involved drying by pinning the skin fur side down and driving the moisture from the skin by covering with hot ashes. Once dry, the skin was scraped clean and then softened through scoring with a stone blade. The resultant skin could be folded for storage (or trade) and was eventually sewn into a cloak of other clothing or rug using sinews from kangaroo tails (Berndt and Berndt 1993, 113).

Longer animal bones, such as kangaroo tibia, were worked into bone points (tools), pointing bones (associated with magic) and other useful tools (Walshe 2008). In coastal locations, the shells from larger shellfish were broken and used as small cutting knives. In the Sydney region, shells were manufactured by grinding to form shellfish hooks – an entire gendered industry was connected with this practice (Attenbrow 2010b).

The final act of disposal is connected with human waste management, including faeces, urine and phlegm. Archaeologically, little consideration is given to human waste disposal, but it would have been a major consideration in camp establishment and management. For some groups, such as the Ngarrindjeri, these human bodily products could also be collected by unscrupulous individuals and consequently used in sorcery – “a little of the substance obtained was mixed with dead person’s fat: the result of urine sorcery was bladder trouble; with phlegm and saliva, a severe cold with chest pains that could lead to death” (Berndt and Berndt 1993, 258).

Discussion

This chapter has provided an overview of long-term diets relating to Aboriginal peoples in temperate Southern Australia. Current analysis of diet directly measurable from stable isotopes in human skeletal remains suggests that from the mid Holocene to the point of invasion, Aboriginal diets had regional specificity but remained unchanged. The long-term stability in Aboriginal diet is an important factor when considering known changes to the regional environments of southern Australia (such as changes in climate, the environment, precipitation, temperature and sea levels). When coupled with the perceived changes to Aboriginal societies, such as social closure limiting unrestricted movement of people, demographic changes or increasing population densities in the late Holocene, stability in long-term diet must have implications for concepts associated with intensification models (e.g. Morgan 2015).

We know through archaeological studies of individual sites (e.g. Attenbrow 2006), or large-scale material and tool technologies (e.g. Hiscock and Attenbrow 2005) that significant changes to Aboriginal technologies and societies occurred through the Pleistocene into the Holocene. However, it is the bioarchaeological studies which can present data that informs debate around specialisation, diversification and innovation in the food systems.

The food systems described above are complex and intertwined with changing and evolving Aboriginal social traditions. It is clear that many regional specialisations exist, and that the systems themselves would change through time. Understanding a local food system is an important part of describing any Aboriginal clan or group but knowing that basic models of protein food group consumption remained stable for long periods of time is important when investigating aspects such as land use intensification, changing productivity or alterations in efficiency (in food collection and processing).

These complex and evolving social traditions around food can lead to many different regional specialisations, diversifications and innovations (after Morgan 2015, 199). Specialisation could include systems such as the Eastern Regional System for stone artefacts, or creation of local food production economies with the collection of large amounts of food through new innovative techniques (such as net manufacture) – coupled with means of preserving foods for long-term storage and later consumption or trade. Diversification in terms of food could mean accessing more food but from the same resources – but not necessarily an increase in dietary breadth outside the base protein group. For example, if freshwater fish was the main source of protein in a diet, then diversification saw new techniques that allowed more and different species of fish to be caught, not a change to hunting land-based animals. Such diversification can be linked to innovation that allowed access to previously restricted environments, for example the commencement of mound construction allowed long term access and habitation in wetland and flood prone landscapes. Innovation can be seen within many food procurement and processing systems, including the development of means to detoxify foods. It is also apparent in methods of cooking, with the advent of the common use of the ground oven, making food taste better, and also more hygienic (killing bacteria through cooking).

These food systems can variously describe both increases and decreases in efficiency, that is the time required at each stage of the food system. Food is an essential part of life, but also essential to the function of a society. Some of the innovations and adaptations, such as fishing from a canoe using a line and a bara (shell fishhook), may not have increased the economic productivity (in terms of quantity) of an Aboriginal society. However, the advent of this mode of fishing by women did hold social importance, potentially increasing the social richness and diversity of daily life for women within their communities.

Conversely, many of the changes described allowed for significant increases in economic and social complexity. Methods used to obtain large quantities of food allowed for mass gatherings of Aboriginal peoples, for long periods of time. Regular gatherings of large groups for trade, ceremony and other activities again suggests increased social complexity through the Holocene. Understanding the food systems is important because it provides context for agents of change, such as social closure or increased spirituality, which could have influenced Aboriginal peoples’ mobility, access to food, trade and territoriality.

References

Adams, C., T. Owen, D. Pate, D. Bruce, K. Nielson, R. Klaebe, M. Henneberg and I. Moffat (2022). “Do dead men tell no tales?” The geographic origin of a colonial period Anglican cemetery population in Adelaide, South Australia, determined by isotope analyses. Australian Archaeology 88(2): 144–58.

DOI: 10.1080/03122417.2022.2086200.

Anson, T. (1997). The effect of climate on stable nitrogen isotope enrichment in modern South Australian mammals. Master’s thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA.

Asmussen, B. (2010). In a nutshell: the identification and archaeological application of experimentally defined correlates of Macrozamia seed processing. Journal of Archaeological Science 37: 2117–25.

Australian Archaeology (2021). Forum 87(3): 300–25.

Attenbrow, V. (2010a). Sydney’s Aboriginal past: investigating the archaeological and historical records. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Attenbrow, V. (2010b). Aboriginal fishing on Port Jackson, and the introduction of shell fish-hooks to coastal New South Wales, Australia. In P. Hutching,

D. Lunney and D. Hochuli, eds. The natural history of Sydney, 16–34. Mosman: Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.

Attenbrow, V. (2006). What’s changing: population size or land-use patterns? The archaeology of Upper Mangrove Creek, Sydney Basin. Terra Australis 21. Canberra: ANU Press.

Berndt, C. and R. Berndt (1993). A world that was. The Yaraldi of the Murry River and the lakes, South Australia. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Berndt, C. and R. Berndt (1974). The First Australians, 3rd edn. Sydney: Ure Smith.

Bird, R., D. Bird, B. Codding, C. Parker and J. Jones (2008). The ‘‘fire stick farming’’ hypothesis: Australian Aboriginal foraging strategies, biodiversity, and anthropogenic fire mosaics. PNAS 105(39): 14796–801.

Brockwell, S., B. Ó Foghlú, J. Fenner, J. Stevenson, U. Proske and J. Shiner (2017). New dates for earth mounds at Weipa, North Queensland, Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 52: 127–34.

Cahir, F., I. Clark and P. Clarke (2018). Aboriginal biocultural knowledge in south-eastern Australia. Perspectives of the early colonists. Clayton South: CSIRO Publishing.

Clarke, P. (2012). Australian plants as Aboriginal tools. Dural: Rosenberg Publishing.

Coutts, P., P. Henderson and R. Fullagar (1979). A preliminary investigation of Aboriginal mounds in north western Victoria. Records of the Victorian Archaeological Survey 9: Ministry for Conservation.

Denham, T., R. Fullagar and L. Head (2009). Plant exploitation on Sahul: From colonisation to the emergence of regional specialisation during the Holocene. Quaternary International 202: 29–40.

Hayes, S. (1999). The Kaurna calendar: seasons of the Adelaide Plains. Honours thesis, the University of Adelaide, SA.

Hiscock, P. and V. Attenbrow (2005). Australia’s Eastern Regional Sequence revisited: technology and change at Capertee 3. BAR International Series 1397. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Gott, B. (1982). Ecology of root use by the Aborigines of southern Australia. Archaeology of Oceania 17: 59–67.

Lewis, S., C. Sloss, C. Murray-Wallace, C. Woodroffe and S. Smithers (2013). Post-glacial sea-level changes around the Australian margin: a review. Quaternary Science Reviews 74: 115–38.

Littleton J., K. Walshe and J. Hodges (2013). Burials and time at Gillman Mound, northern Adelaide, South Australia. Australian Archaeology 77: 38–51.

Lourandos, H. (1997). Continent of hunter-gatherers: new perspectives in Australian prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McBryde, I. (1997). The cultural landscapes of Aboriginal long distance exchange systems: can they be confined within our heritage registers? Historic environment 13: 6–14.

Macdonald, G. (2017). Focussing on creeks: Wiradjuri ecology, sociality and cosmology. Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia 41: 63–92.

Morgan, C. (2015). Is it intensification yet? Current archaeological perspectives on the evolution of hunter-gatherer economies. Journal of Archaeological Research 23: 163–213.

National Museum of Australia (NMA) (2023). Burke and Wills, NMA website, accessed 28 May 2023. https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/burke-and-wills.

Ó Foghlú, B. (2021). Mounds of the north: discerning the nature of earth mounds in north Australia. Doctoral thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT.

Owen, T. (2004). “Of more than usual interest”: a bioarchaeological analysis of ancient Aboriginal skeletal material from southeastern South Australia. Doctoral thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA.

Owen, T. and Pate D. (2014). A Kaurna burial, Salisbury, South Australia: further evidence for complex late Holocene Aboriginal social systems in the Adelaide region. Australian Archaeology 79: 45–53.

Owen, T., J. Field, S. Luu, Kokatha Aboriginal People, B. Stephenson and A. Coster (2019). Ancient starch analysis of grinding stones from Kokatha Country, South Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science 23: 178–88.

Owen, T.D., J. Jones-Webb, L. Watson and C. Norman (2022). Parramatta, NSW: A deep time Aboriginal cultural landscape. Journal of the Australian Association of Consulting Archaeologists 9: 10–29.

Pascoe, B. (2014). Dark emu: black seeds: agriculture or accident? Broome: Magabala Books.

Pate, F.D., R. Brodie and T. Owen (2002). Determination of geographic origin of unprovenanced Aboriginal skeletal remains in South Australia employing carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis. Australian Archaeology 55: 1–7.

Pate, F.D. and T. Anson (2012). Stable isotopes and dietary composition in the mid-late 19th century Anglican population, Adelaide, South Australia. Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia 35: 1–16.

Pate, F.D. and T. Owen (2014). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes as indicators of sedentism and territoriality in late Holocene South Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 49(1): 56–65.

Roberts, A., D. Pate and R. Hunter (1999). Late Holocene climatic changes recorded in macropod bone collagen stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes at Fromm’s Landing, South Australia. Australian Archaeology 49: 48–9.

Rowland, M. (2002). Geophagy: an assessment of implications for the development of Australian Indigenous plant processing technologies. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2002(1): 50–65.

Sutton P. and K. Walsh (2021). Farmers or hunter-gather? The Dark Emu debate. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Taplin, G. (1879). The Narrinyeri. In J. Woods, ed. The native tribes of South Australia. Adelaide: ES Wigg & Son.